1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common and potentially serious sleep-related breathing disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction during sleep, resulting in intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation [

1]. In the general population, approximately 23.4% (95% CI 20.9-26.0) of women and 49.7% (46.6-52.8) of men are affected from moderate-to-severe OSA (≥15 events per h) [

2]. However, its prevalence rises significantly among individuals with mental disorders, particularly those with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia [

3,

4].

Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy remains the gold standard treatment for moderate to severe OSA, improving not only respiratory outcomes but also cardiovascular and neurocognitive functioning [

5,

6]. Nevertheless, adherence to PAP therapy is frequently suboptimal and may be particularly challenging for patients with comorbid mental illness due to factors such as reduced insight, executive dysfunction, or the effects of psychiatric medication [

7].

Patients with serious mental disorders often experience excessive daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or insomnia—symptoms that overlap with those of OSA. As a result, OSA may be underdiagnosed in this population due to symptom misattribution and limited access to sleep evaluations [

8,

9]. Emerging evidence highlights the importance of identifying and treating OSA in individuals with psychiatric disorders. Studies have shown that patients with major depression or schizophrenia have a higher prevalence of moderate to severe OSA than the general population, with reported rates ranging from 14% to over 40%, depending on diagnostic criteria and psychiatric subgroup [

4]. Importantly, untreated OSA in these populations has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk, cognitive impairment, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms. In contrast, PAP therapy has demonstrated benefits extending beyond improved sleep quality, including improvements in mood and cognitive function [

10].

Despite these findings, data on long-term adherence to and the effectiveness of PAP therapy in patients with comorbid mental disorders remain sparse. Understanding whether psychiatric comorbidity compromises PAP adherence or diminishes treatment efficacy is essential for optimizing clinical management. Addressing these questions requires well-designed prospective studies that evaluate both objective and subjective sleep parameters, along with anthropometric and clinical outcomes, over extended follow-up periods.

The objective of this study was to evaluate PAP therapy adherence and effectiveness in patients with moderate to severe OSA, comparing those with comorbid mental disorders to those without. The primary objectives were to assess PAP usage patterns and therapeutic outcomes, including changes in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, heart rate and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores, across multiple follow-up visits, and to determine whether mental comorbidity independently influences these parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

The data presented were collected as part of a prospective cohort investigation conducted across two major University Hospitals in Greece, each hosting specialized sleep clinics, between January 2015 and May 2025. Adults (≥18 years) presenting with suspected OSA and no prior diagnosis or treatment for OSA were considered for inclusion. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of all participating hospitals, and all procedures involving human participants complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study Population

A total of 1,672 adults with newly diagnosed moderate to severe OSA were enrolled. OSA diagnosis was established using overnight polysomnography (PSG) or home polygraphy (PG) according to standard criteria (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] ≥15 events/hour). Patients were categorized into two groups: a) Group A (Mental Disorder Group): patients with a documented diagnosis of a stable mental disorder under appropriate treatment (n = 221) and b) Group B (Control Group): patients without any history of mental illness (n = 1,451).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria comprised adults aged ≥ 18 years with newly diagnosed moderate to severe OSA (AHI ≥ 15 events/hour of sleep), who consented to initiate PAP therapy. Only individuals with stable psychiatric or other comorbid conditions, adequately managed through pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment, were included. Exclusion criteria included unstable medical or psychiatric comorbidities, severe cognitive impairment or dementia that could interfere with treatment compliance, refusal to initiate PAP therapy, and incomplete follow-up data.

Procedures and Follow-Up

At baseline (Visit 1), all participants underwent a comprehensive clinical evaluation. Anthropometric measurements included height, weight, BMI, and waist, hip, and neck circumferences. Vital signs, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate, were also recorded. Spirometry was performed to assess pulmonary function and forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) were expressed as percentages of predicted values. Sleep parameters were derived from PSG or PG recordings including total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep architecture , AHI, oxygen desaturation index (ODI), and both mean and minimum oxygen saturation (SaO2) levels. Subjective daytime sleepiness was evaluated using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS).

Following the diagnosis of OSA, all patients initiated PAP therapy, either with CPAP or auto-adjusting PAP (APAP). Adherence was objectively monitored via device-generated data, recording average nightly usage in hours.

Subsequent follow-up assessments were conducted at regular intervals: at three months after PAP initiation (Visit 2), and annually thereafter for up to three years (Visits 3-5). At each visit, adherence data were downloaded from PAP devices and anthropometric and vital parameters (BMI, blood pressure, heart rate, and neck, waist, and hip circumferences) were reassessed. The ESS was re-administered at each visit to evaluate changes in subjective sleepiness over time.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes of the present study included adherence to PAP therapy and treatment effectiveness. Adherence was quantified as the average daily usage in hours. Effectiveness was evaluated by changes from baseline in key clinical parameters, including the ESS score, BMI, blood pressure, heart rate, and temporal trends in PAP usage.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as frequencies (percentages). Between-group comparisons were performed using the independent samples t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Linear mixed models were used to analyze repeated measures data for both daily device use (hours/day) and daytime sleepiness (ESS) across study visits. Each outcome was modeled separately using Visit as a fixed effect and patient ID as a random factor to account for within-subject correlations. A diagonal covariance structure was specified, and parameter estimation was performed using restricted maximum likelihood (REML). Degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Satterthwaite approximation. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 1,672 individuals, divided into two groups: patients with a diagnosed mental disorder (Group A, n=221) and those without a mental disorder (Group B, n=1,451).

At baseline, patients in Group A were slightly younger than those in Group B (55.08 vs. 57.59 years; p = 0.006) and more likely to be female (52% vs. 36.7%; p <0.001). BMI and blood pressure were similar between groups; however, resting heart rate was significantly higher in Group A (81.13 vs. 75.1 bpm; p = 0.013), possibly reflecting autonomic dysregulation or medication-related effects. ESS scores and pulmonary function measures did not differ significantly between groups.

Regarding sleep characteristics, patients in Group A had longer total sleep time (277.35 vs. 247.71 min; p <0.001) but exhibited altered sleep architecture, characterized by less Stage 1 (p = 0.017) and Stage 3 (p = 0.04), and more Stage 2 (p = 0.001) sleep. Oxygen saturation was slightly higher in Group A (lowest SaO2 81.82% vs. 80.04%; p = 0.007), while time spent below 90% SaO2, AHI and ODI were comparable between groups.

Baseline anthropometric characteristics and sleep parameters are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 respectively.

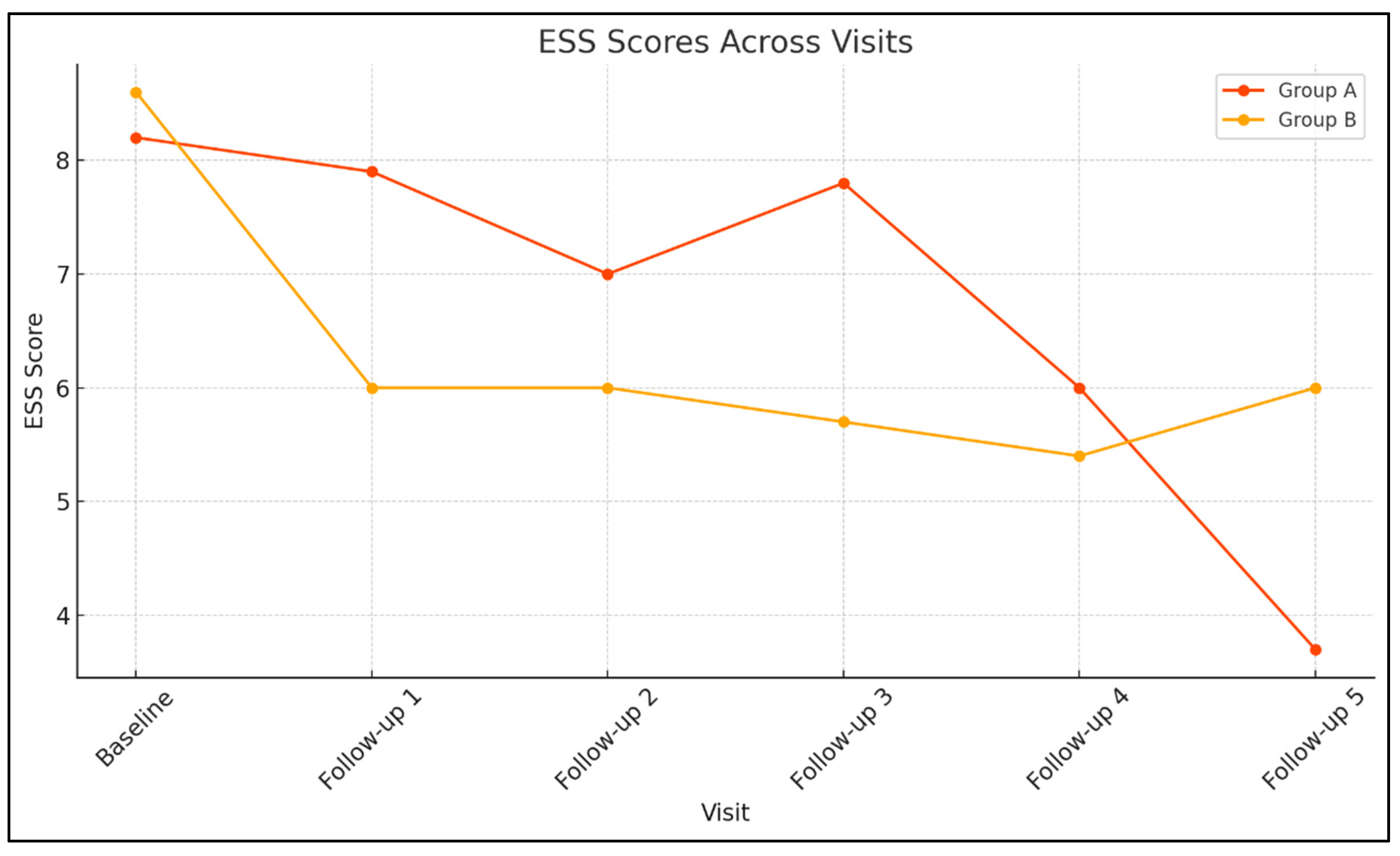

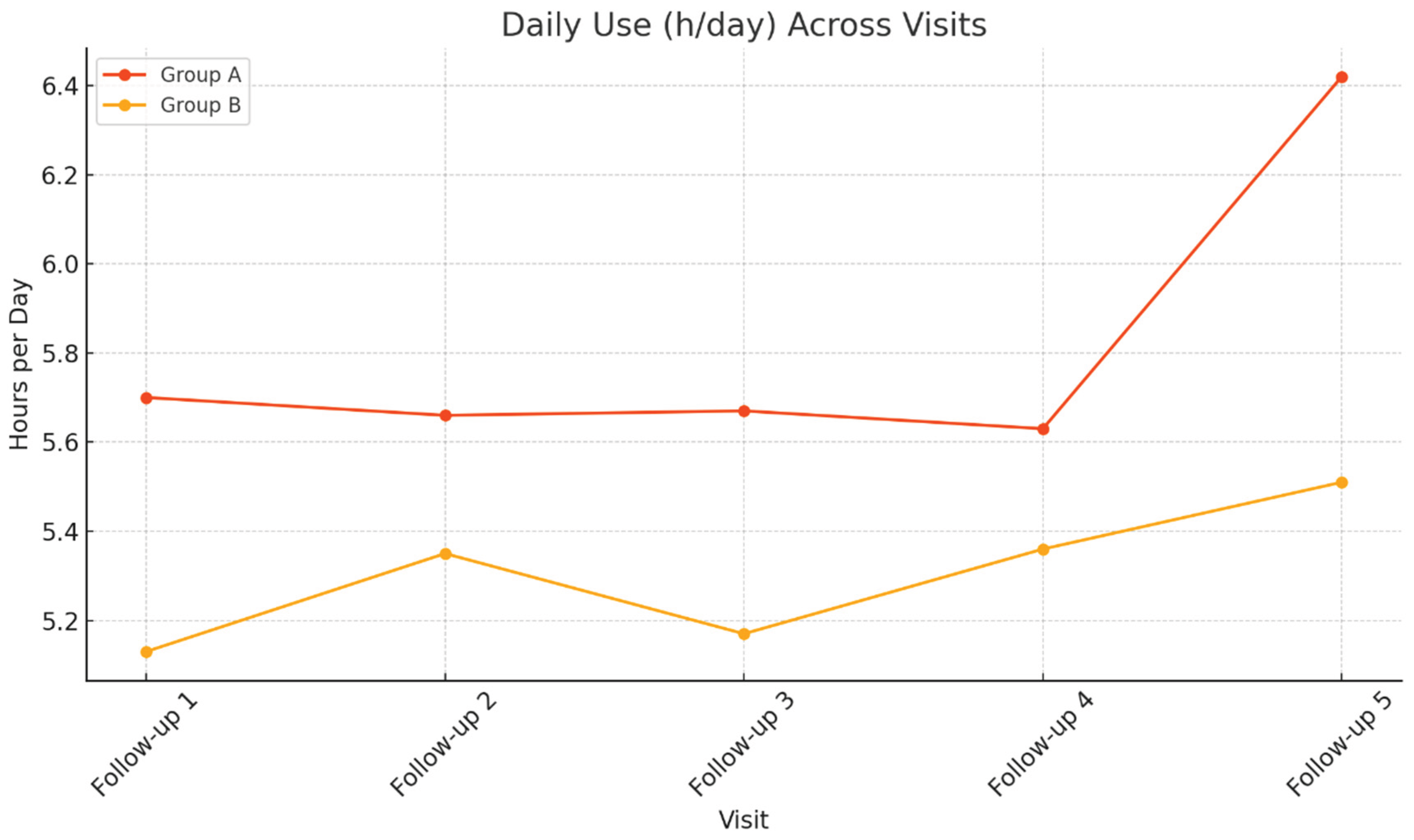

At the first follow-up visit (Visit 1) the sample consisted of 657 participants (66 in Group A and 591 in Group B). BMI and blood pressure remained similar between groups, indicating no significant metabolic differences. However, daytime sleepiness was more pronounced among patients with mental disorders (ESS 7.88 vs. 6.03; p = 0.027). PAP adherence showed a non-significant trend toward greater usage in Group A (5.71 vs. 5.14 h/day; p = 0.054).

At the second follow up visit (Visit 2), 385 participants were reassessed (36 in Group A and 349 in Group B). BMI and blood pressure remained similar, with no significant differences between groups. Patients in Group A continued to report higher ESS scores (7vs. 6.01), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.497). PAP adherence remained stable, with slightly higher usage in Group A (5.66 vs. 5.35 h/day; p = 0.394), supporting the trend of comparable or slightly better adherence despite psychiatric comorbidity.

At the third follow-up visit (Visit 3), the sample comprised 244 participants (27 in Group A and 217 in Group B). BMI and blood pressure remained comparable between groups. Group A showed slightly higher daytime sleepiness (ESS 7.85 vs. 5.59; p = 0.058), a difference that approached but did not reach significance. PAP adherence again favored Group A (5.67 vs. 5.17 h/day; p = 0.237), indicating sustained engagement with therapy.

At the fourth follow-up visit (Visit 4), 134 participants (15 in Group A and 119 in Group B) were evaluated. No statistically significant differences were observed between groups in BMI, blood pressure, or heart rate, suggesting similar cardiometabolic profiles. Daytime sleepiness remained slightly higher in Group A (ESS 6 vs. 5.36; p = 0.688. PAP adherence remained comparable, with slightly higher usage in Group A (5.62 vs. 5.37 h/day; p = 0.66), reinforcing the trend of sustained, long-term treatment adherence.

At the final follow-up (Visit 5) the sample consisted of 69 participants (9 in Group A and 60 in Group B). Anthropometric and hemodynamic measures remained similar between groups. Interestingly, patients in Group A reported lower daytime sleepiness (ESS 3.67 vs. 6.; p = 0.335) and higher mean PAP usage (6.42 vs. 5.49 h/day; p = 0.206), though these differences were not statistically significant.

Linear mixed models were conducted to assess longitudinal changes in daily PAP usage (hours/day) and daytime sleepiness (ESS scores) across follow-up visits. In Group A, the effect of Visit on device daily use was not statistically significant, F (4, 12.79) = 0.184, p = 0.942, indicating stable PAP usage over time. In contrast, ESS scores in Group A showed a significant main effect of Visit, F (5, 14.29) = 4.619, p = 0.01, suggesting that daytime sleepiness varied significantly across visits. Similarly, in Group B, ESS scores demonstrated a robust effect of Visit, F (5, 60.39) = 29.52, p <0 .001, indicating significant temporal variation in daytime sleepiness. The effect of Visit on daily device use was not statistically significant, F (4, 150.11) = 1.102, p =0.358, consistent with stable adherence across time points.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate the longitudinal trends of ESS scores and daily PAP usage, respectively, across multiple follow-up visits for Groups A and B.

4. Discussion

Across a cohort of 1,672 patients with sleep apnea followed for up to three years, we observed that both groups, those with and without mental disorders, benefited from PAP therapy. However, individuals with psychiatric comorbidities exhibited distinct patterns in adherence and symptom resolution. This prospective cohort study demonstrated that patients with moderate to severe OSA and comorbid mental disorders maintained consistent and comparable adherence to PAP therapy throughout the three-year follow-up period, with adherence levels occasionally surpassing those of patients without psychiatric diagnoses. Despite initially greater daytime sleepiness, individuals with mental disorders showed progressive symptom improvement, ultimately achieving lower ESS scores at the final follow-up. These findings challenge long-held assumptions about poor treatment compliance among individuals with mental health illness and highlight the potential for effective long-term OSA management in patients with stable psychiatric conditions.

Previous studies have emphasized the high prevalence of undiagnosed OSA among individuals with psychiatric disorders, particularly depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A substantial proportion of these patients meet diagnostic criteria for OSA, yet often undiagnosed or untreated, despite the presence of classic symptoms such as fatigue and excessive daytime sleepiness [

11,

12,

13]. Similar findings were reported by Alam et al. [

14] and Gupta and Simpson [

15], who found elevated OSA risk (ranging from 39% to 69%), but strikingly low rates of prior diagnosis or PAP use. In contrast, the present study focused exclusively on patients with confirmed moderate to severe OSA, including a sizeable subset with comorbid mental disorders who were initiated on PAP therapy and followed longitudinally. This design allowed us to move beyond risk estimation and examine real-world patterns of treatment adherence and clinical response in this high-risk population.

In terms of treatment effectiveness, prior research has suggested that PAP therapy may confer psychiatric benefits, particularly in mood, cognition, and functional status [

13]. However, these studies often lacked long-term objective outcome measures. In our cohort, patients with mental disorders initially exhibited higher and more variable ESS scores, but showed sustained reductions over time, reaching a mean score of 3.67 at the fifth follow-up, lower than that of the non-psychiatric group (ESS = 6.00). This delayed yet significant improvement supports the hypothesis proposed by Vanek et al. [

16] that PAP therapy may yield meaningful neuropsychiatric improvements, a finding previously unconfirmed due to the absence of longitudinal data.

Overall, our findings highlight the feasibility and long-term efficacy of PAP therapy in patients with comorbid mental illness, particularly when psychiatric symptoms are stable and well-managed. Clinicians should not assume reduced compliance in this population; instead, they should emphasize early and continuous patient education, regular follow-up, and integration of psychiatric care into sleep management. Delayed symptom resolution should not be interpreted as therapeutic failure, but may instead reflect gradual neurobehavioral adaptation to improved sleep architecture.

Furthermore, the slightly higher PAP adherence observed among psychiatric patients suggests that structured follow-up and coordinated care can mitigate potential barriers to adherence. Intergrating mental health support into PAP adherence programs may further enhance treatment outcomes.

This study has several limitations. First, psychiatric diagnoses were not stratified by type or severity, potentially obscuring differential effects among subgroups (e.g., major depressive disorder vs. schizophrenia). Second, the exclusion of patients with unstable psychiatric or medical conditions limits the generalizability of findings to more complex populations. Third, although PAP usage was objectively monitored, symptom burden was primarily assessed using the ESS, a widely used but subjective measure influenced by mood and perception. Finally, although the follow-up period extended to five years, not all participants completed every visit, introducing potential attrition bias.

Future research should employ more granular psychiatric categorization and include additional metrics of cognitive and functional recovery beyond sleepiness. Incorporating qualitative assessments could also help elucidate motivational and perceptual barriers to adherence. Additionally, investigating the effects of psychiatric medication type and dosage on PAP efficacy and symptom resolution would be highly informative. Studies exploring integrated care models—where sleep specialists and psychiatrists collaborate in the management of patients—may yield strategies to further enhance long-term outcomes in this dual-diagnosis population.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that patients with comorbid mental disorders and moderate to severe OSA can achieve comparable, and in some cases superior, adherence to PAP therapy during long-term follow-up, challenging the common assumption that psychiatric illness inherently compromises treatment compliance. Although these patients initially exhibited higher daytime sleepiness, they experienced progressive symptomatic improvement, ultimately attaining outcomes equal or better than those without psychiatric comorbidity. These findings underscore the importance of identifying and actively managing OSA in individuals with mental disorders, particularly when their psychiatric conditions are stable and well controlled. Long-term PAP therapy appears both feasible and effective in this population, supporting the need for integrated care approaches that combine sleep medicine and mental health services to optimize patient outcomes. Further research is warranted to clarify the specific effects of different psychiatric diagnoses and pharmacological treatments on OSA management and to develop targeted interventions that enhance PAP adherence and quality of life in this high-risk group of patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.E.G. and G.T.; methodology, V.E.G. and P.S.; validation, V.E.G., A.K., P.S. and G.T.; formal analysis, V.E.G.; investigation, V.E.G. and A.K.; resources, A.K. and P.S.; data curation, V.E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.E.G.; writing—review and editing, A.K., P.S. and G.T.; visualization, V.E.G.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Alexandra Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions related to sensitive patient information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AHI |

Apnea–Hypopnea Index |

| APAP |

Auto-Adjusting Positive Airway Pressure |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| BP |

Blood Pressure |

| CPAP |

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure |

| ESS |

Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| FEV1

|

Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second |

| FVC |

Forced Vital Capacity |

| ODI |

Oxygen Desaturation Index |

| OSA |

Obstructive Sleep Apnea |

| PAP |

Positive Airway Pressure |

| PG |

Polygraphy |

| PSG |

Polysomnography |

| REM |

Rapid Eye Movement |

| REML |

Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| SaO2

|

Arterial Oxygen Saturation |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

References

- Slowik, J.M.; Sankari, A.; Collen, J.F. Obstructive sleep apnea. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459252/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Athar, W.; Card, M.E.; Charokopos, A.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and pain intensity in young adults. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knechtle, B.; Economou, N.T.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; et al. Clinical characteristics of obstructive sleep apnea in psychiatric disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Veronese, N.; et al. The prevalence and predictors of obstructive sleep apnea in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 197, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.S.; Liu, K.T.; Panjapornpon, K.; Andrews, N.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N. Functional outcomes in patients with REM-related obstructive sleep apnea treated with positive airway pressure therapy. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.P.; Ayappa, I.A.; Caples, S.M.; Kimoff, R.J.; Patel, S.R.; Harrod, C.G. Treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea with positive airway pressure: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 301–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVettori, G.; Troxel, W.M.; Duff, K.; Baron, K.G. Positive airway pressure adherence among patients with obstructive sleep apnea and cognitive impairment: A narrative review. Sleep Med. 2023, 111, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabryelska, A.; Turkiewicz, S.; Białasiewicz, P.; et al. Evaluation of daytime sleepiness and insomnia symptoms in OSA patients with characterization of symptom-defined phenotypes and their involvement in depression comorbidity: A cross-sectional clinical study. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1303778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trakada, G.; Velentza, L.; Konsta, A.; Pataka, A.; Zarogoulidis, P.; Dikeos, D. Complications of anesthesia during electroconvulsive therapy due to undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea: A case study. Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 20, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanek, J.; Prasko, J.; Genzor, S.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, depression and cognitive impairment. Sleep Med. 2020, 72, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakow, B.; Lowry, C.; Germain, A.; et al. A retrospective study on improvements in nightmares and post-traumatic stress disorder following treatment for co-morbid sleep-disordered breathing. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 49, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benca, R.M.; Krystal, A.; Chepke, C.; Doghramji, K. Recognition and management of obstructive sleep apnea in psychiatric practice. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2023, 84, 22r14521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, T.; Zolezzi, M. Obstructive sleep apnea: Management considerations in psychiatric patients. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 2691–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, A.; Chengappa, K.N.; Ghinassi, F. Screening for obstructive sleep apnea among individuals with severe mental illness at a primary care clinic. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2012, 34, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.A.; Simpson, F.C. Obstructive sleep apnea and psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 11, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanek, J.; Prasko, J.; Genzor, S.; et al. Cognitive functions, depressive and anxiety symptoms after one year of CPAP treatment in obstructive sleep apnea. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).