1. Introduction

The pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) has long been hindered by the challenge of creating systems that can operate effectively across diverse domains while maintaining consistent reasoning capabilities and safety constraints. Current AI approaches often excel in narrow domains but fail to generalize or integrate knowledge across different contexts—a phenomenon sometimes called "jagged intelligence" [

1]. This paper introduces Constrained Object Hierarchies (COH) as a unified theoretical framework for AGI that addresses these limitations through a neuroscience-grounded approach to system modeling.

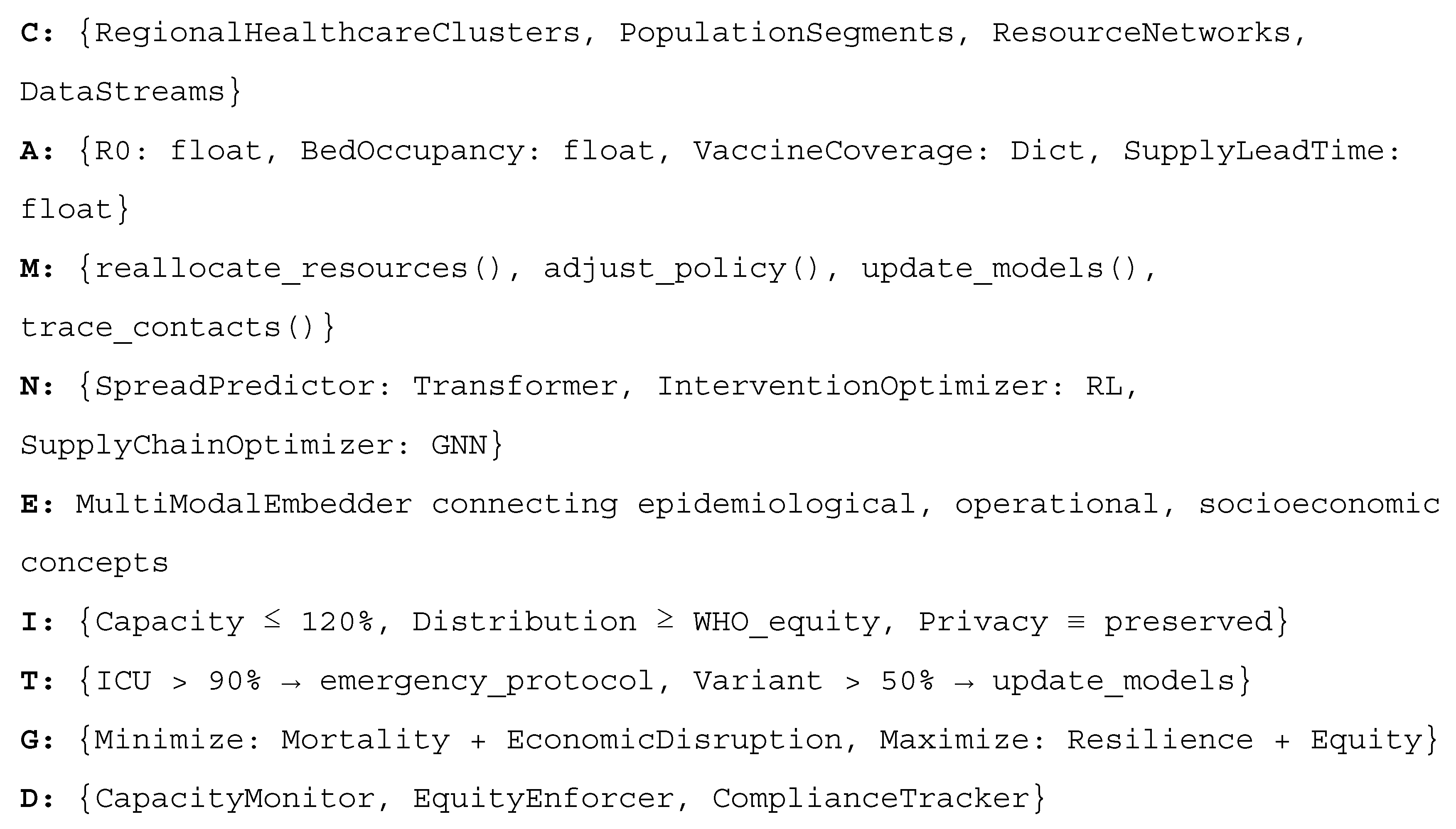

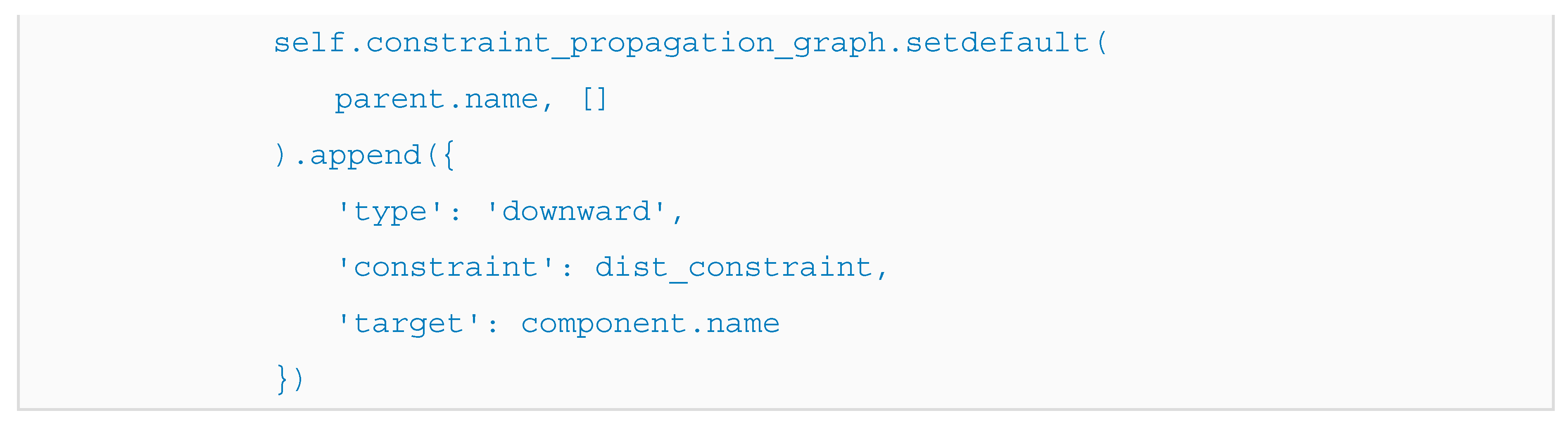

Constrained Object Hierarchies formalizes intelligent systems as hierarchical structures of objects subject to multiple constraint types, expressed as a 9-tuple:

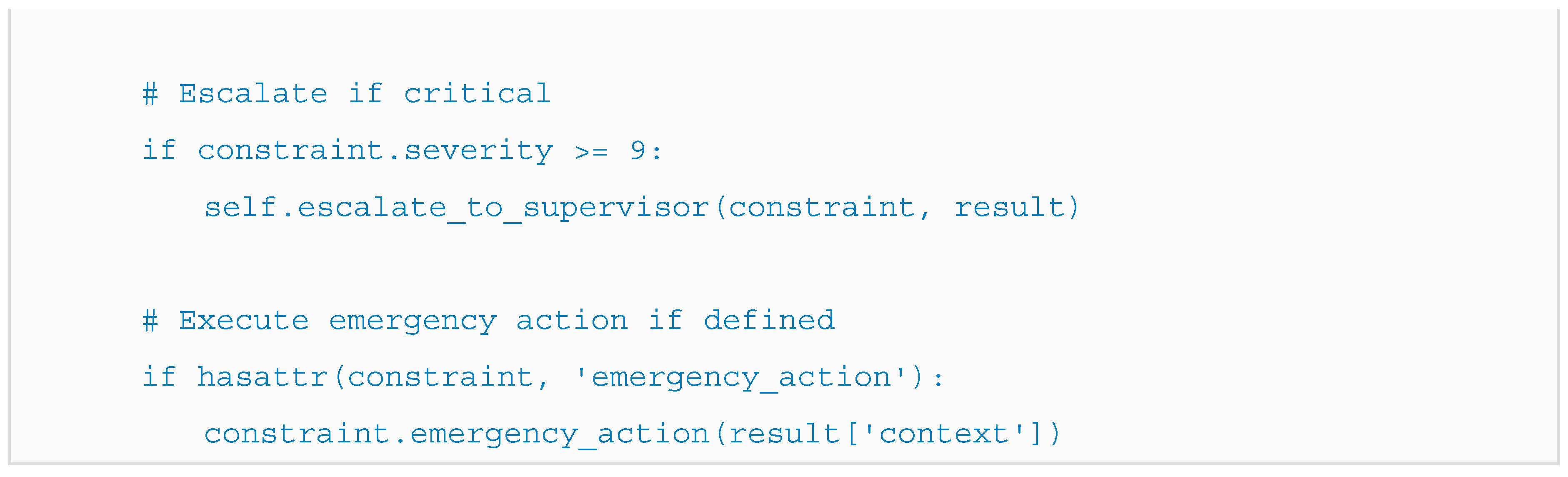

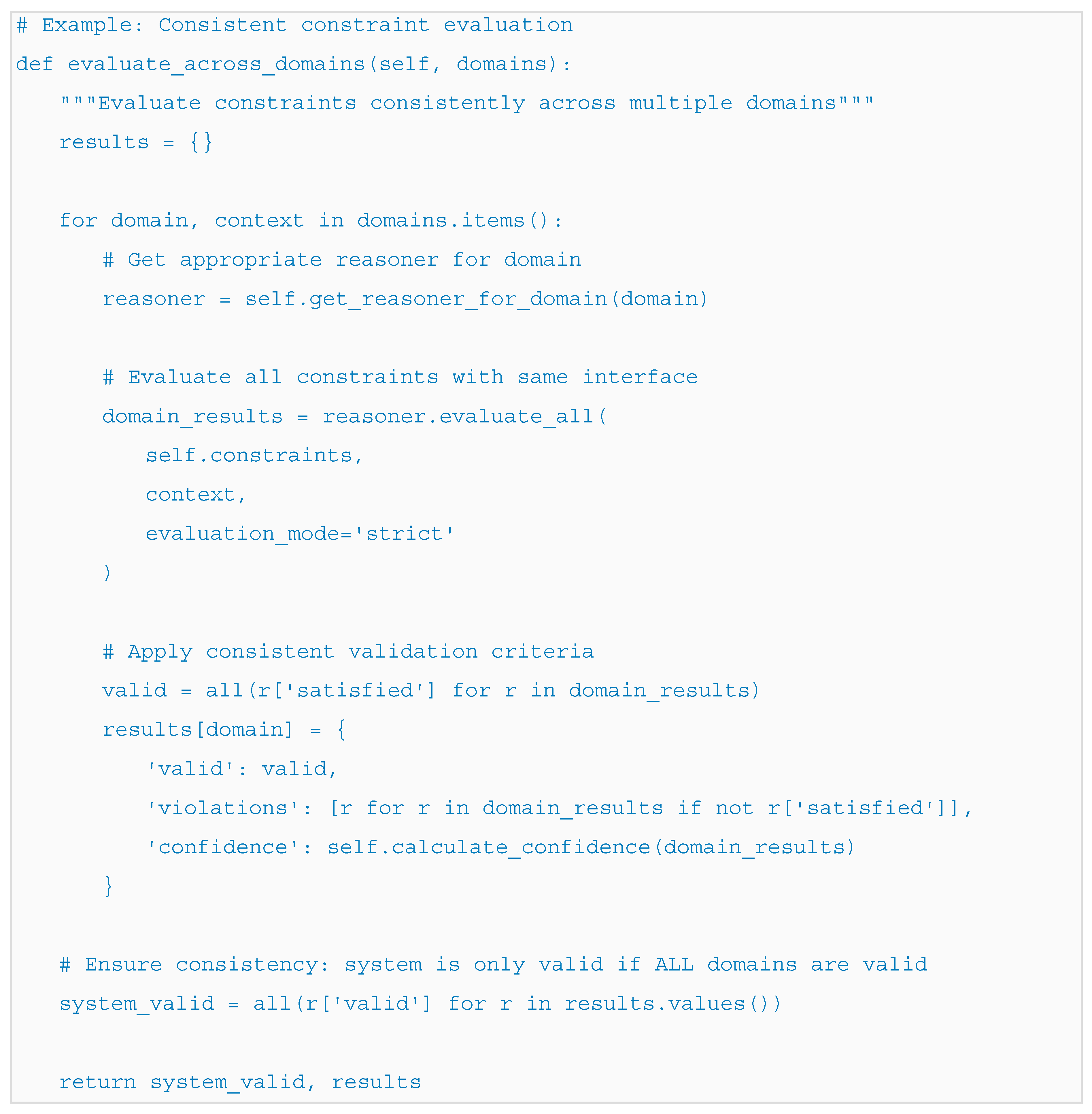

O = (C, A, M, N, E, I, T, G, D). This representation captures the essential elements of intelligent systems: compositional structure (C), state variables (A), executable actions (M), adaptive neural components (N), semantic embeddings (E), and three constraint types—identity (I), trigger (T), and goal (G)—monitored by real-time daemons (D). The framework is grounded in principles from cognitive neuroscience, particularly the hierarchical organization of cortical processing and the constraint-satisfaction nature of neural computation [

2].

We present GISMOL (General Intelligent System Modelling Language) as a Python implementation of the COH framework, providing developers with practical tools for building constraint-aware intelligent systems. GISMOL includes core modules for object representation (gismol.core), neural integration (gismol.neural), multi-domain reasoning (gismol.reasoners), and natural language processing (gismol.nlp). Together, COH theory and GISMOL implementation offer a comprehensive solution for AGI development that addresses both theoretical foundations and practical implementation challenges.

This paper makes three primary contributions: (1) formalization of the COH framework with detailed 9-tuple semantics, (2) demonstration through six complex system case studies across diverse domains, and (3) implementation guidelines showing how COH models translate to executable GISMOL systems. We argue that COH provides a path toward AGI by offering a unified representation that scales across domains while maintaining verifiable constraint satisfaction.

2. Literature Review

Research in AGI has followed multiple paths, including symbolic AI, connectionist approaches, and hybrid systems. Early symbolic systems [

3] demonstrated robust reasoning but lacked learning capabilities, while modern deep learning [

4] excels at pattern recognition but struggles with explicit reasoning and constraint enforcement. Recent approaches have explored neural-symbolic integration [

5], cognitive architectures [

6], and world modeling [

7], yet none have fully addressed the challenge of multi-domain constraint management.

Hierarchical representations have long been recognized as fundamental to intelligence, from Miller's chunking theory [

8] to Hawkins' hierarchical temporal memory [

9]. Constraints have been used in various AI contexts, from constraint satisfaction problems [

10] to constraint programming [

11], but typically as isolated mechanisms rather than integrated frameworks. Neuroscience research supports the hierarchical organization of cortical processing [

12] and the constraint-based nature of neural computation [

13], providing biological grounding for the COH approach.

Multi-domain reasoning has been explored in cognitive architectures like SOAR [

14] and ACT-R [

15], but these often lack seamless neural integration. Recent work on foundation models [

16] demonstrates impressive generalization but suffers from inconsistent behavior and lack of explicit constraint enforcement—the "jagged intelligence" problem [

17]. Safety-critical systems research [

18] emphasizes constraint management but typically focuses on specific domains rather than general intelligence.

World modeling approaches [

19,

20] attempt to create comprehensive environment representations but often lack structured constraint mechanisms. Agent-based systems [

21] provide autonomy but struggle with coordinated constraint management across hierarchies. The COH framework uniquely integrates these elements: hierarchical representation, multi-type constraints, neural adaptation, and domain generality, offering a comprehensive solution to AGI development.

3. Workflow of Modelling and Implementing Complex Systems

The COH/GISMOL framework provides a systematic workflow for modeling and implementing complex intelligent systems across domains. This workflow consists of four main phases: analysis, design, modeling, and implementation, each supported by specific GISMOL components.

The analysis phase begins with domain decomposition, where complex systems are broken down into hierarchical components. GISMOL's COHObject class provides the foundation, allowing developers to represent entities at multiple abstraction levels. During this phase, system requirements are translated into constraint specifications, identifying identity constraints (fundamental properties), trigger constraints (event-driven behaviors), and goal constraints (optimization objectives). The COHRepository helps manage component relationships, while the EntityRelationExtractor from gismol.nlp can assist in extracting structured knowledge from domain documentation.

The design phase focuses on constraint specification and neural component integration. Developers use the ConstraintSystem from gismol.core to define constraints with appropriate categories (safety, temporal, resource, etc.) and severity levels. Neural components are selected based on adaptive requirements: Classifier and Regressor for prediction tasks, NeuralSchedulingModel for planning, and EmbeddingModel for semantic operations. The design must ensure that neural components respect system constraints through the ConstraintAwareOptimizer.

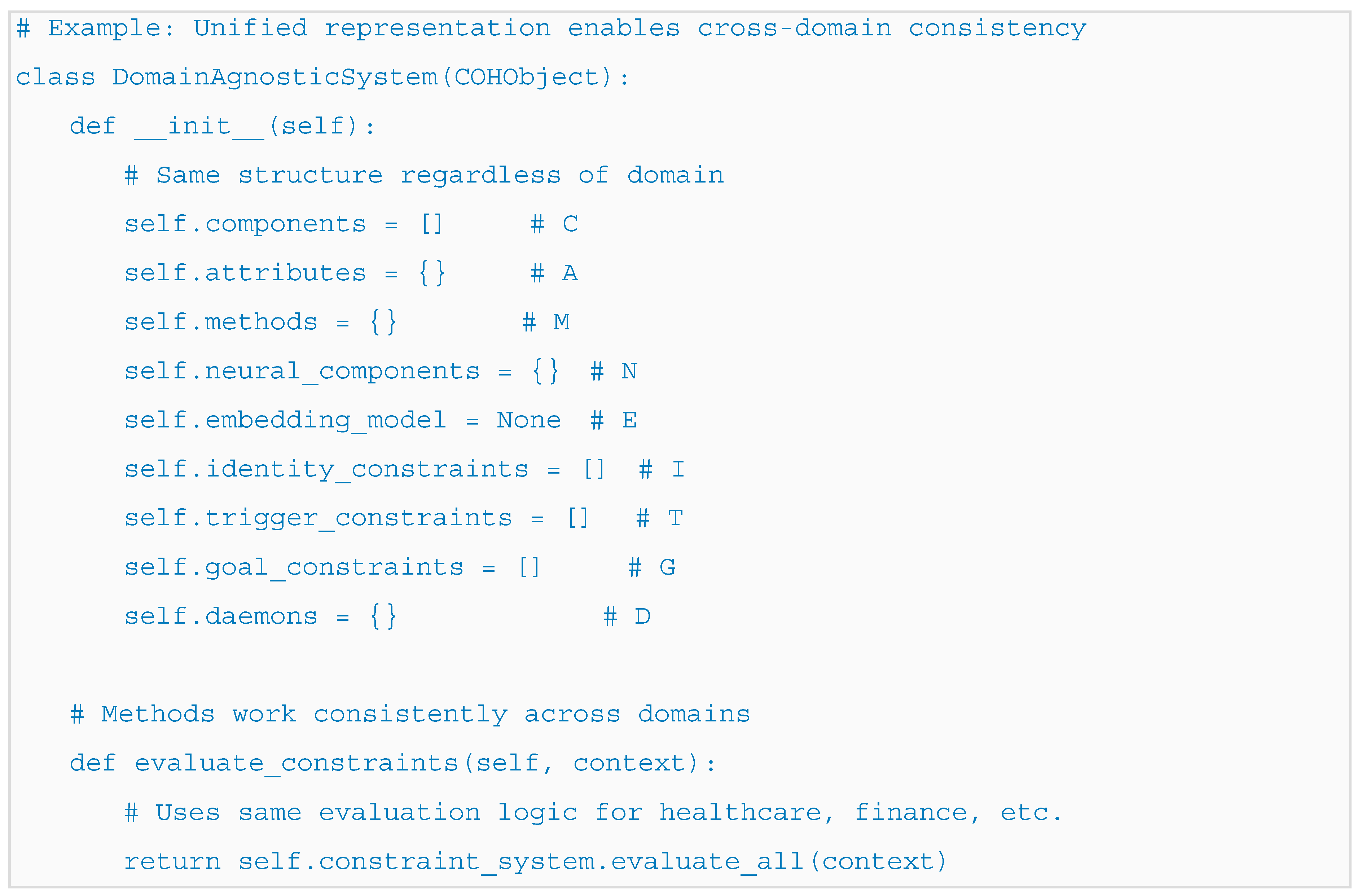

The modeling phase formalizes the system as a COH 9-tuple, specifying all elements: components (C), attributes (A), methods (M), neural components (N), embedding model (E), identity constraints (I), trigger constraints (T), goal constraints (G), and daemon configurations (D). This formal model serves as both documentation and executable specification, with each element mapping directly to GISMOL implementation constructs.

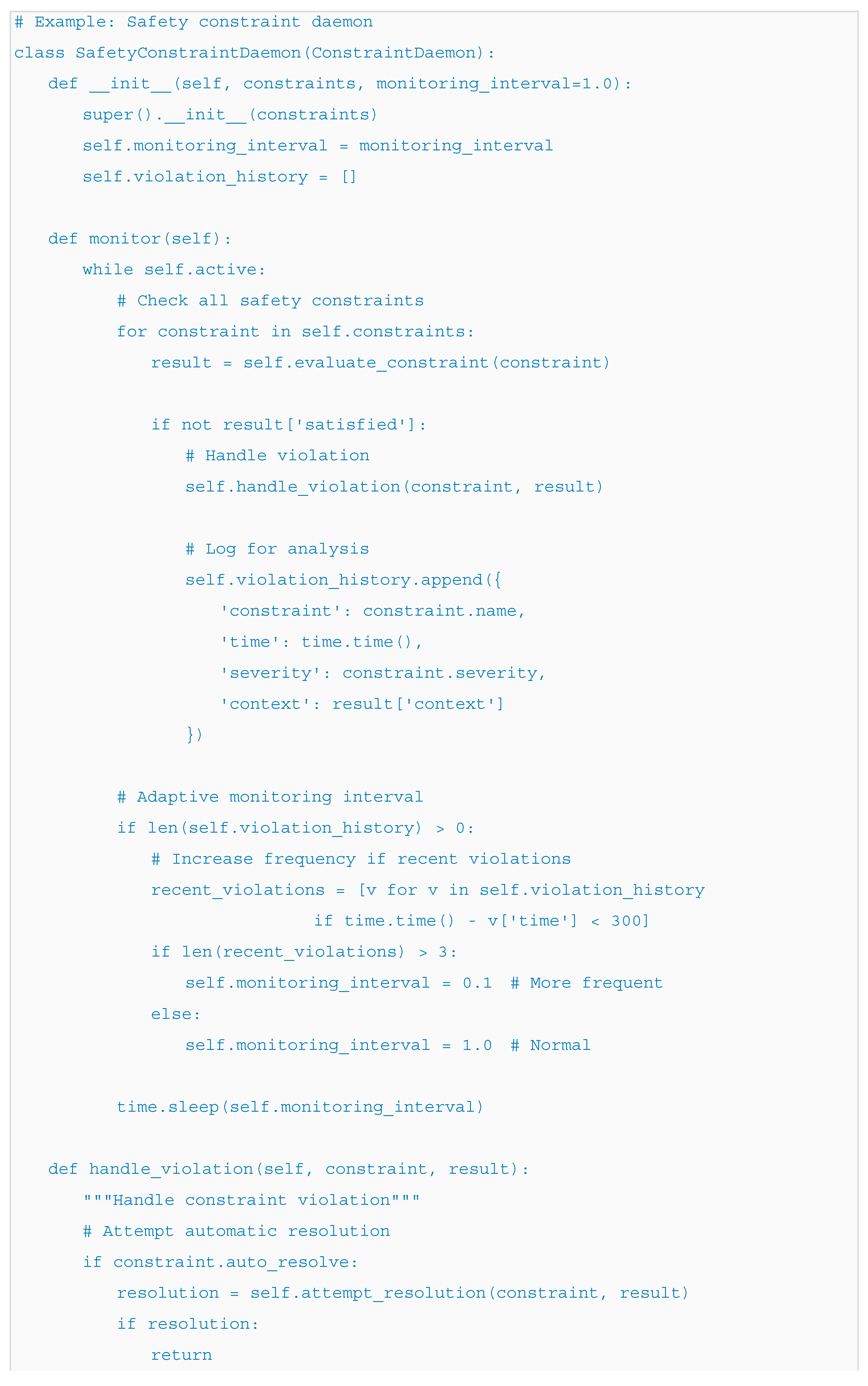

The implementation phase translates the COH model into executable GISMOL code. The COHObject hierarchy is instantiated with specific constraints, neural components are trained with constraint-aware optimization, and daemons are configured for real-time monitoring. Integration testing ensures that constraints are properly enforced across the hierarchy, with the SafetyReasoner providing redundant validation for critical systems. The complete system can then operate autonomously while maintaining all specified constraints.

This workflow enables consistent development of intelligent systems across domains, with explicit constraint management ensuring safety and reliability. The following sections demonstrate this workflow through six detailed case studies.

4. Analysis, Design, Modeling, and Implementation of Complex Systems - Adaptive Pandemic Response System

Due to limitation of space, we will only include the Analysis, Design, Modeling, and Implementation of Adaptive Pandemic Response System in the paper. Other case studies can be found in supplemental material A.

System Description and Significance: Modern pandemics require coordinated responses across healthcare infrastructure, population management, and resource allocation. Traditional approaches struggle with dynamic optimization under uncertainty, leading to suboptimal resource distribution and delayed interventions. An intelligent pandemic response system must balance multiple objectives: minimizing mortality, maintaining healthcare capacity, and preserving socioeconomic function.

Analysis and Requirements: The system requires multi-scale modeling from individual patients to regional healthcare networks. Key requirements include: (1) predictive modeling of disease spread, (2) dynamic resource allocation, (3) policy impact simulation, (4) equity constraints in resource distribution, and (5) real-time adaptation to new information. Constraints must handle uncertainty while ensuring critical thresholds are never violated.

COH Solution Design: The system is designed as a hierarchical network of regional healthcare clusters, population segments, and resource distribution networks. Each component has adaptive neural models for prediction and optimization, with constraints ensuring ethical and operational requirements. Trigger constraints implement responsive policy adjustments, while goal constraints optimize multi-objective outcomes.

9-Tuple Formalization:

Modeling Justification: The hierarchical decomposition allows localized adaptation while maintaining global coordination. Neural components provide predictive capability under uncertainty, while constraints ensure ethical and operational boundaries. Embedding integration enables semantic understanding across different data modalities.

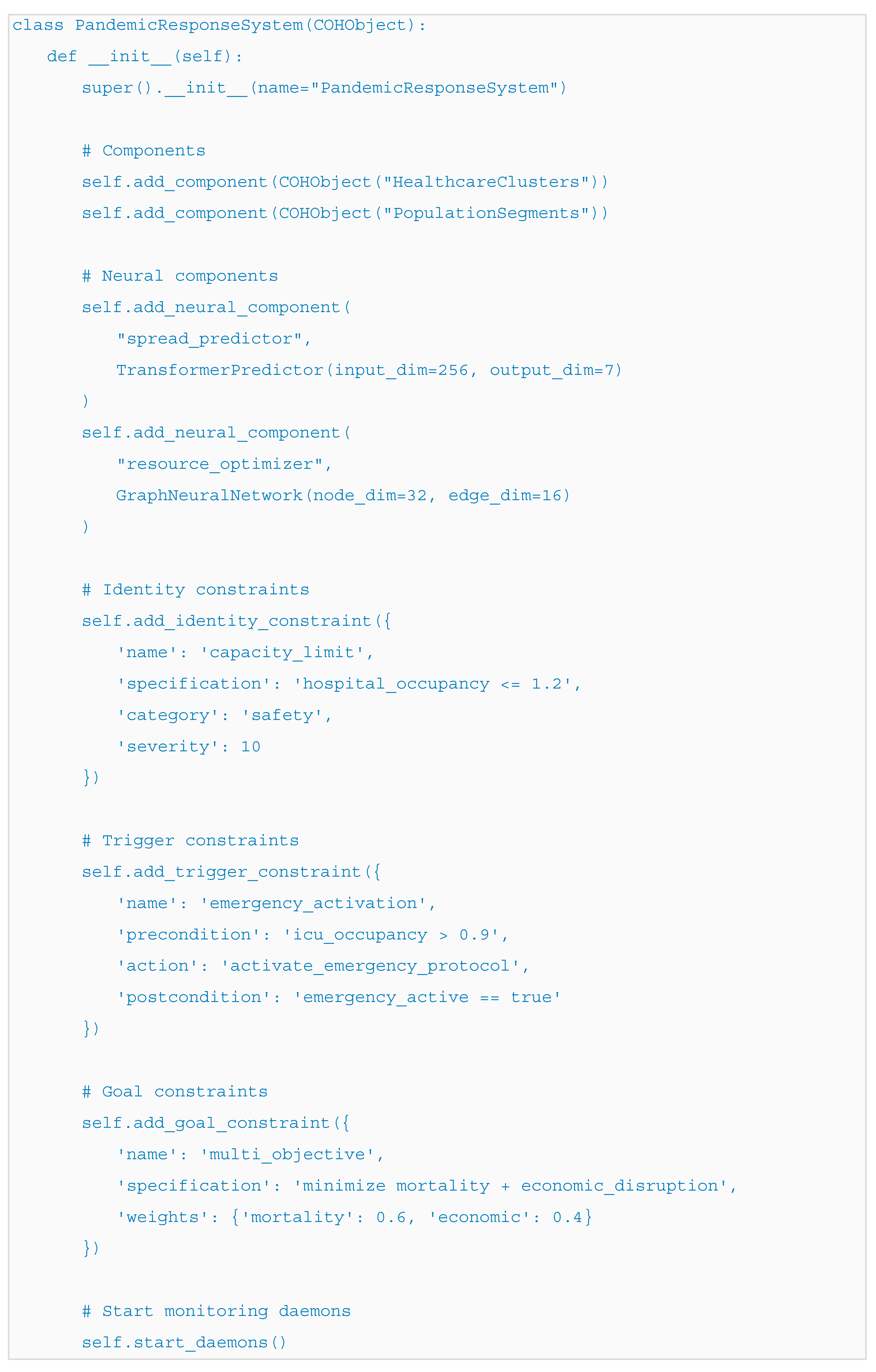

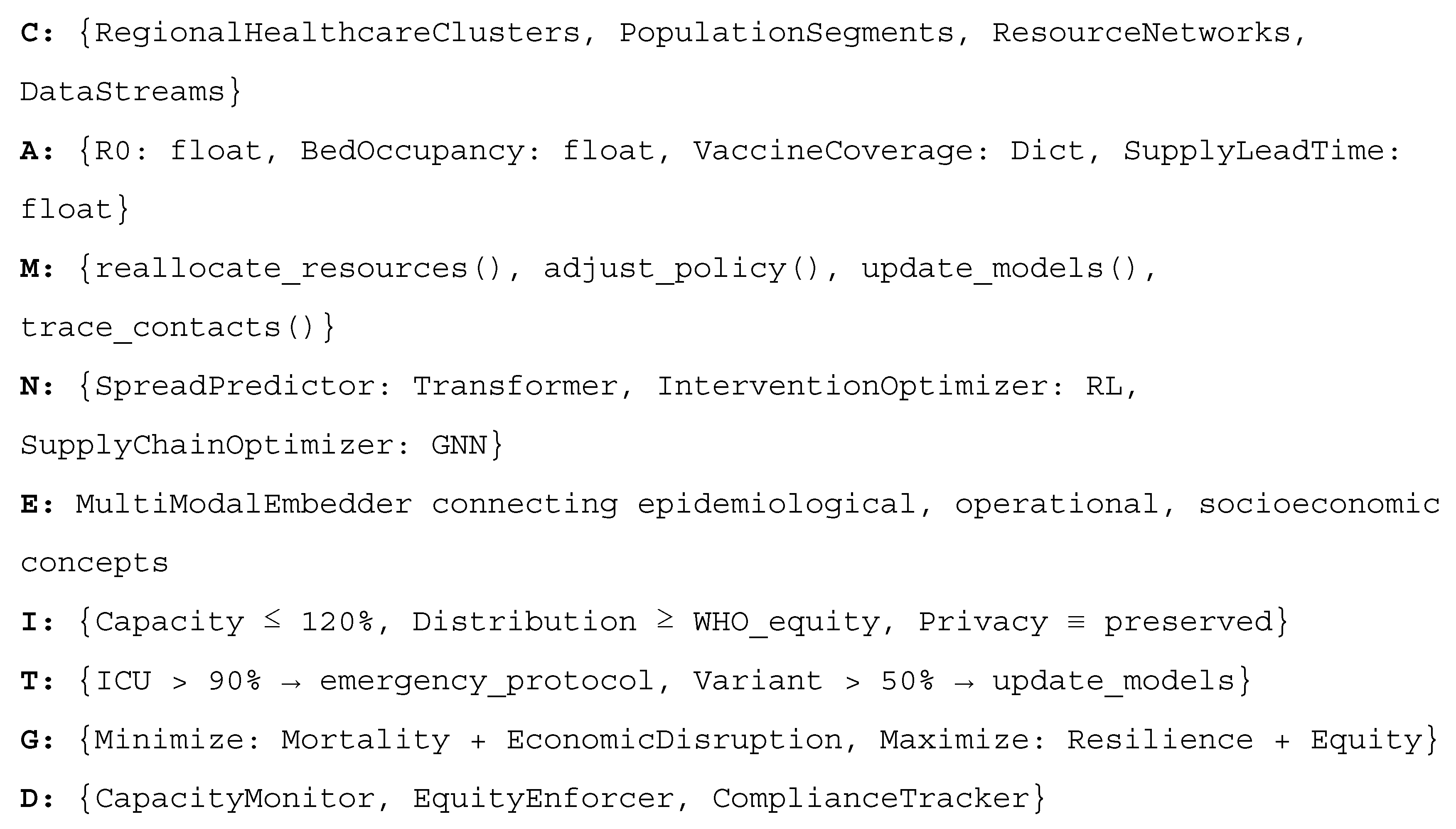

GISMOL Implementation code snippets:

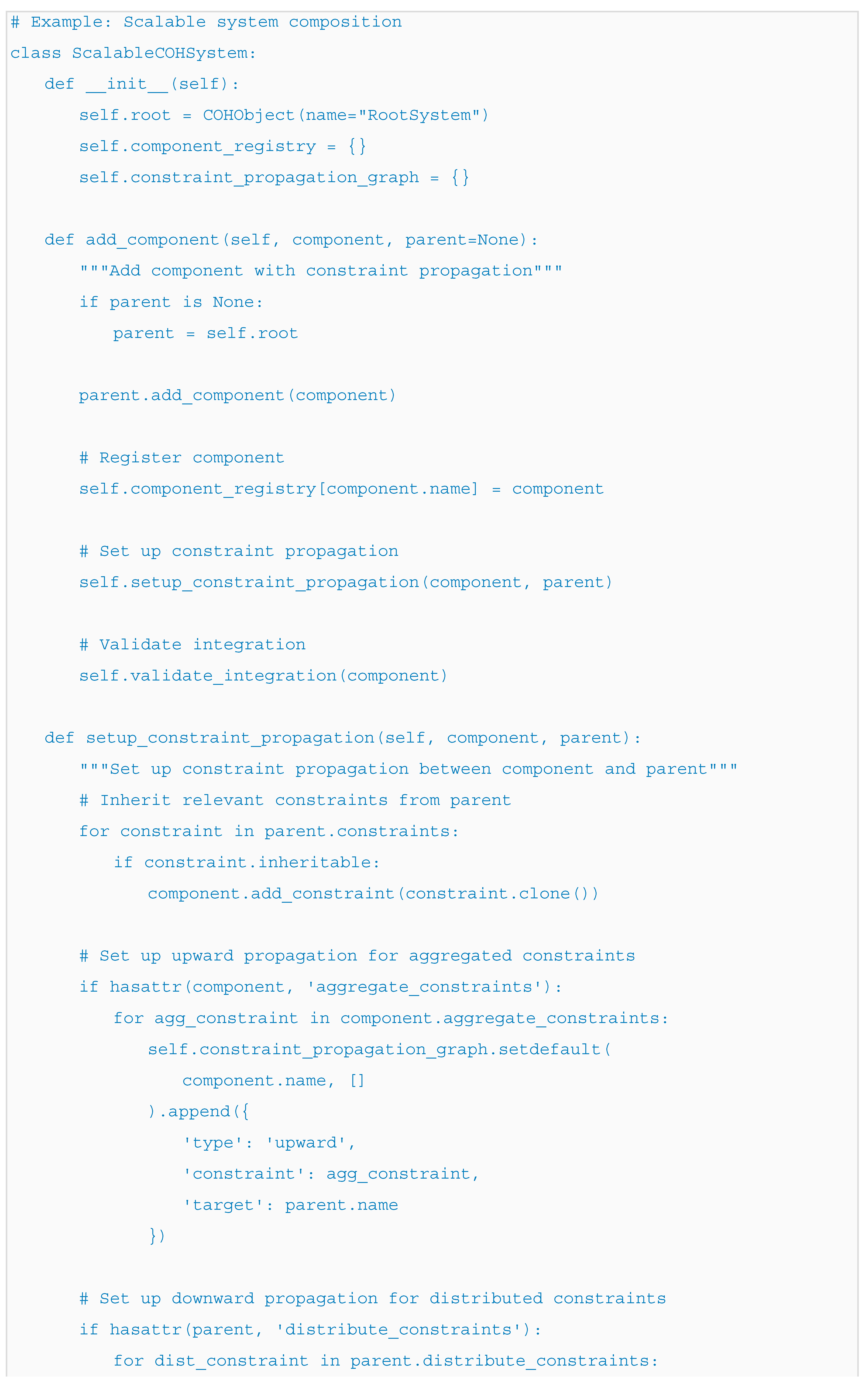

Benefits of Hierarchical Decomposition: Regional clusters operate semi-autonomously while respecting global constraints, enabling localized optimization. Neural components at different levels specialize in their domains while sharing embeddings for coordination. Constraints propagate both upward (aggregate metrics) and downward (resource allocations), ensuring consistency.

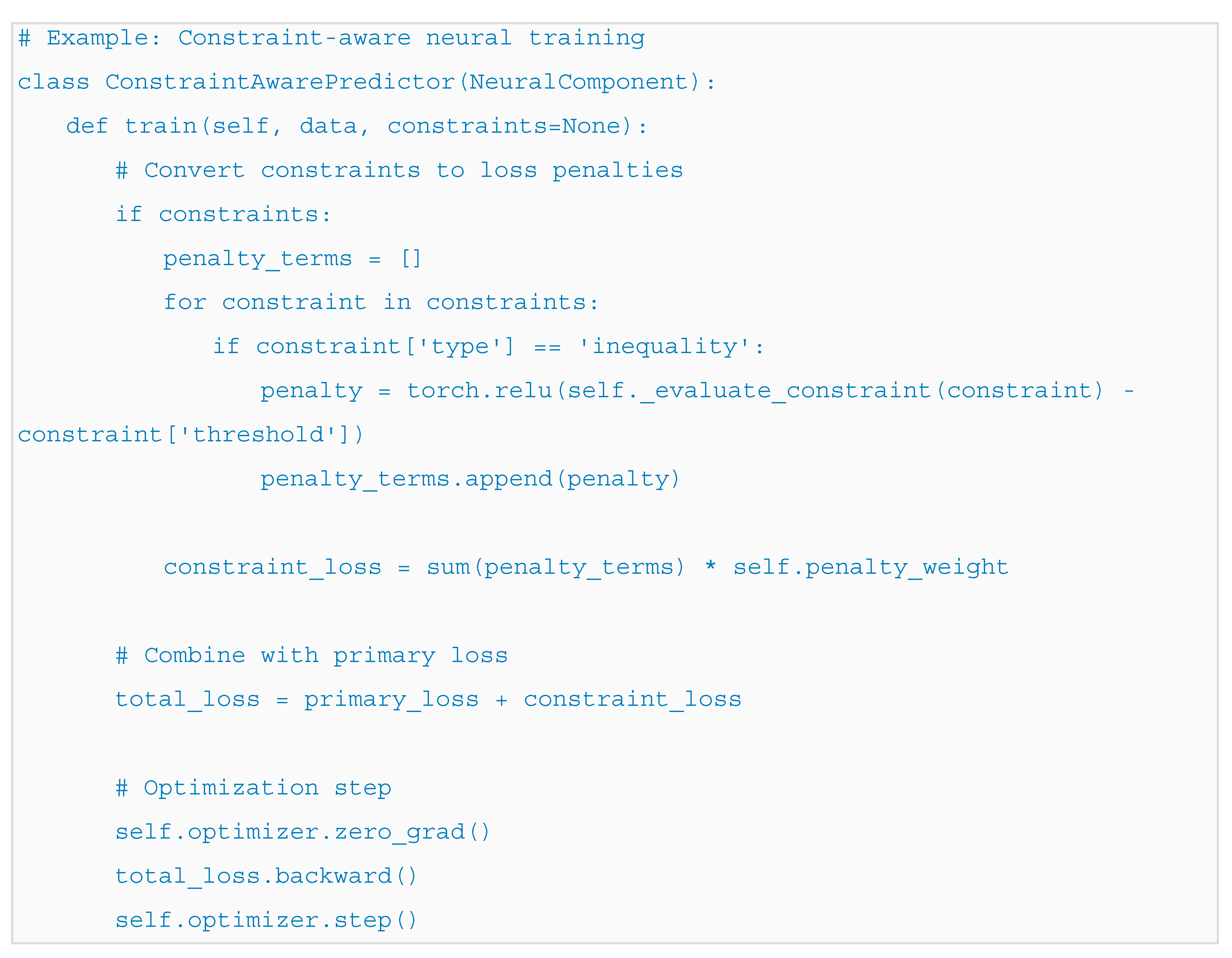

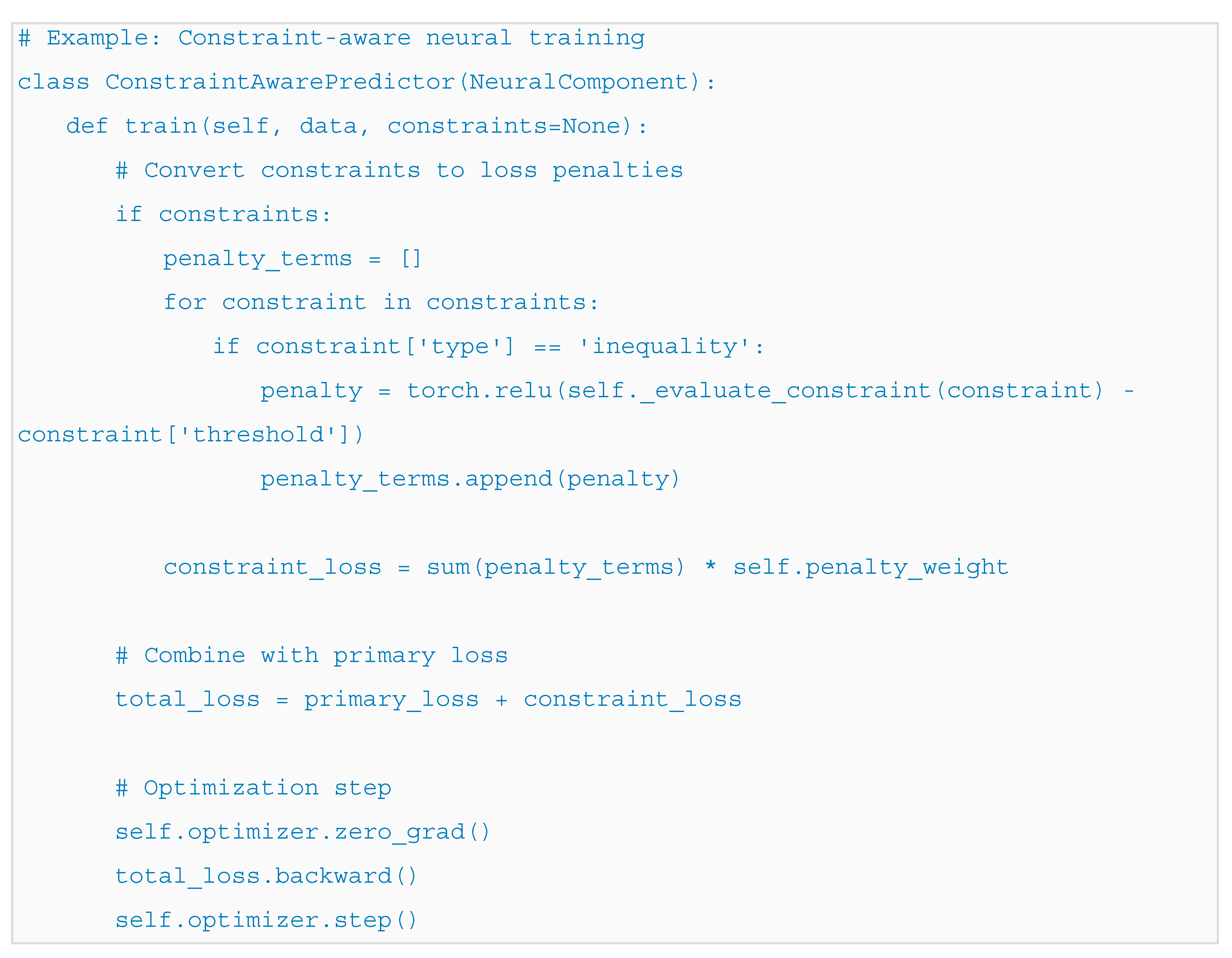

Neural-Constraint Interaction: Spread predictors update based on constraint violations (e.g., when distancing compliance drops), creating feedback loops. The resource optimizer respects equity constraints through penalty terms in its loss function, implemented via ConstraintAwareOptimizer.

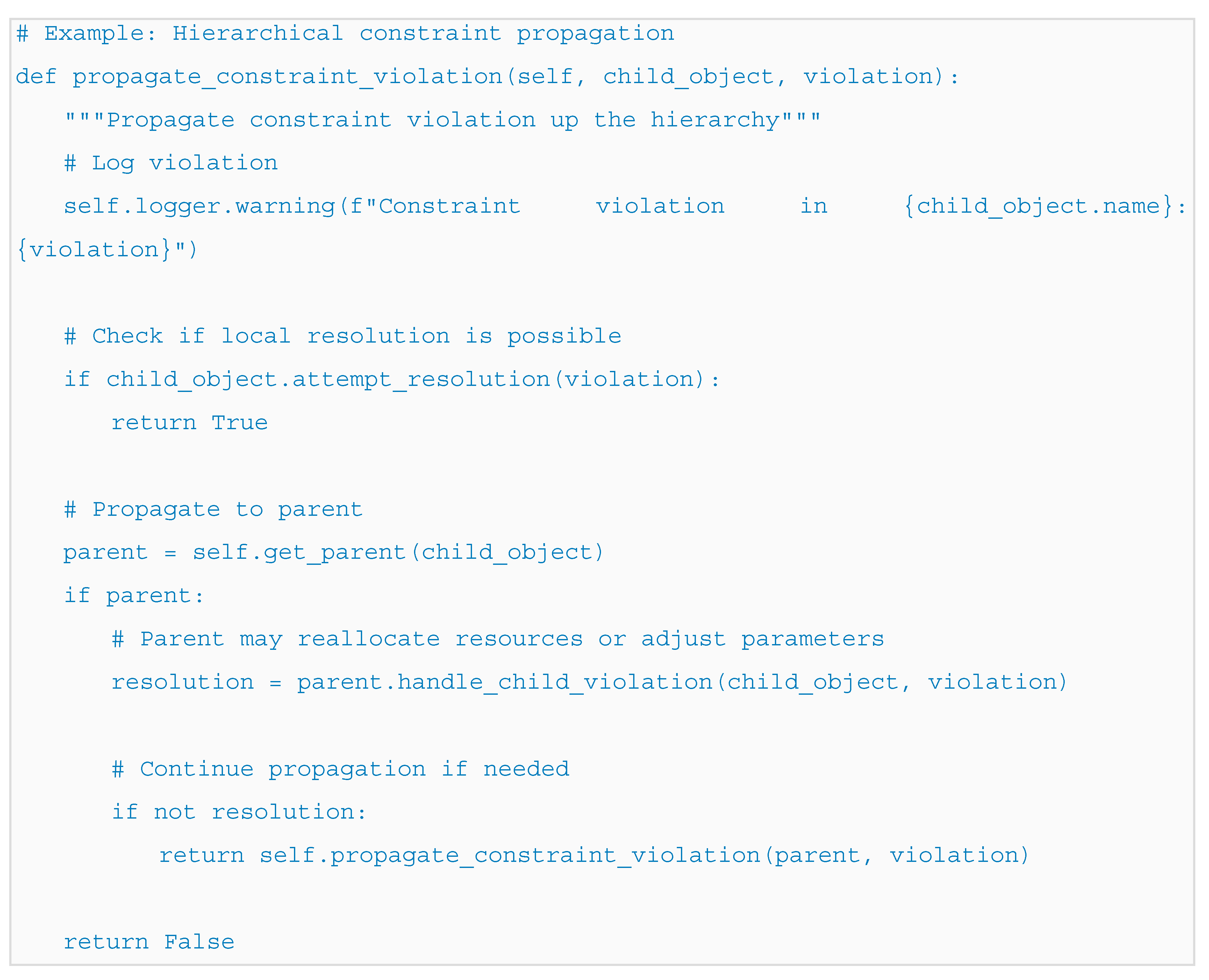

Constraint Propagation: Capacity constraints at hospital level propagate upward to regional constraints, triggering resource redistribution when violated. Equity constraints flow downward to ensure fair distribution across demographic groups.

Constraint Roles: Identity constraints define operational boundaries (capacity limits), trigger constraints implement responsive actions (emergency protocols), and goal constraints guide multi-objective optimization (balancing health and economic outcomes).

Critical Comparison: Traditional compartmental models (SIR/SEIR) [

22] lack resource constraints and optimization capabilities. Agent-based simulations [

23] capture heterogeneity but scale poorly. COH integrates predictive modeling, constraint optimization, and multi-scale coordination in a unified framework with explicit ethical constraints.

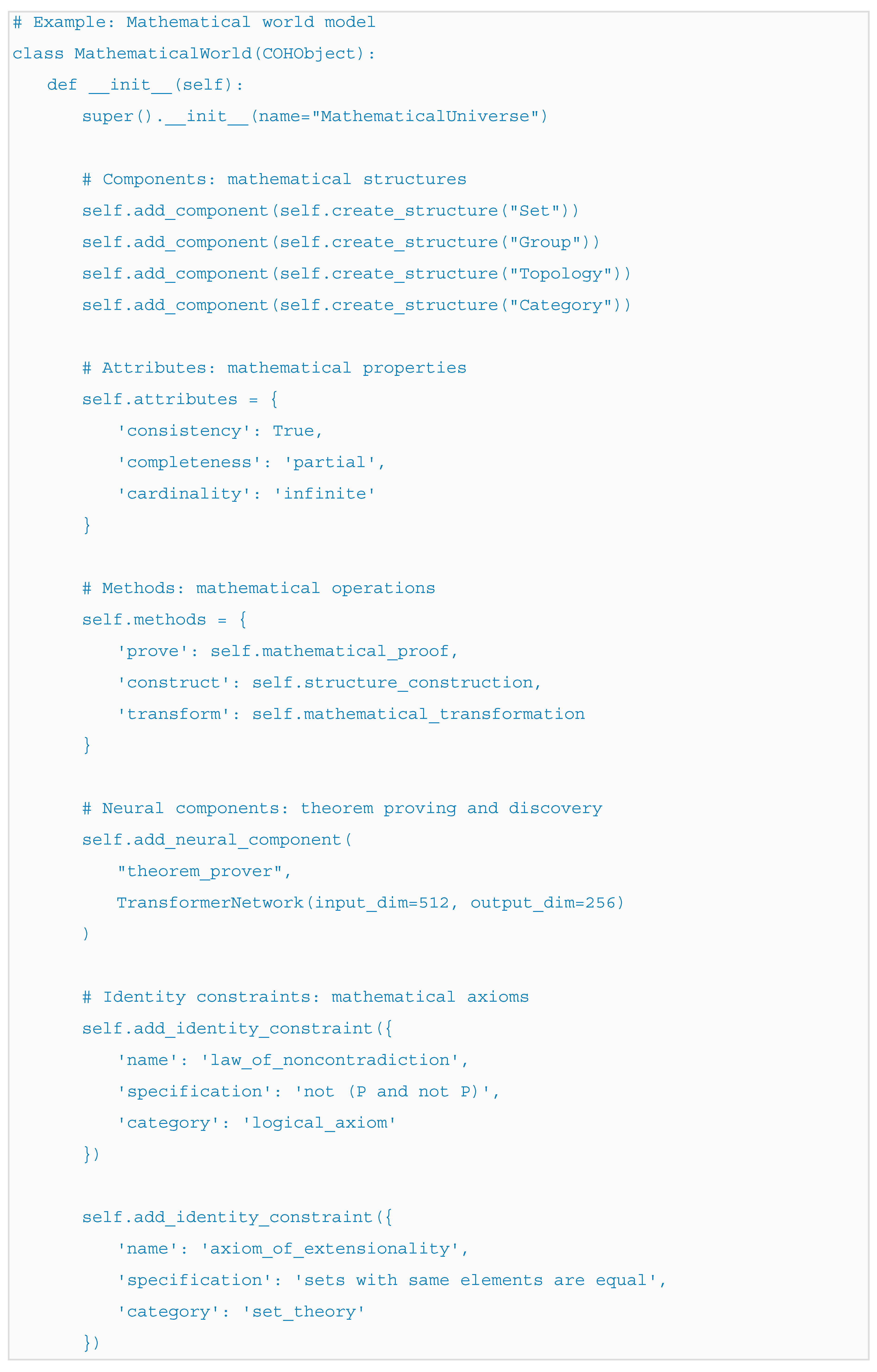

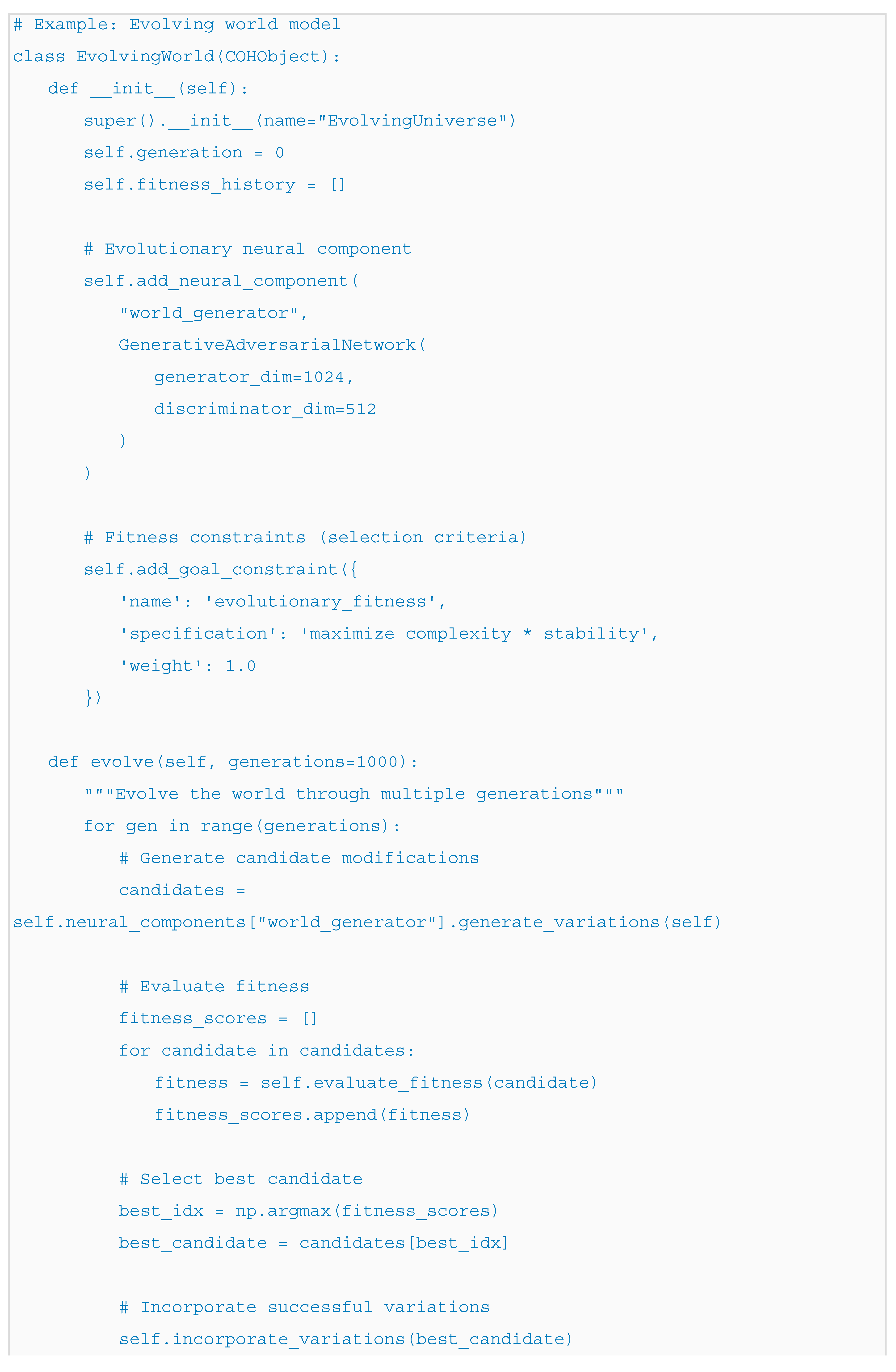

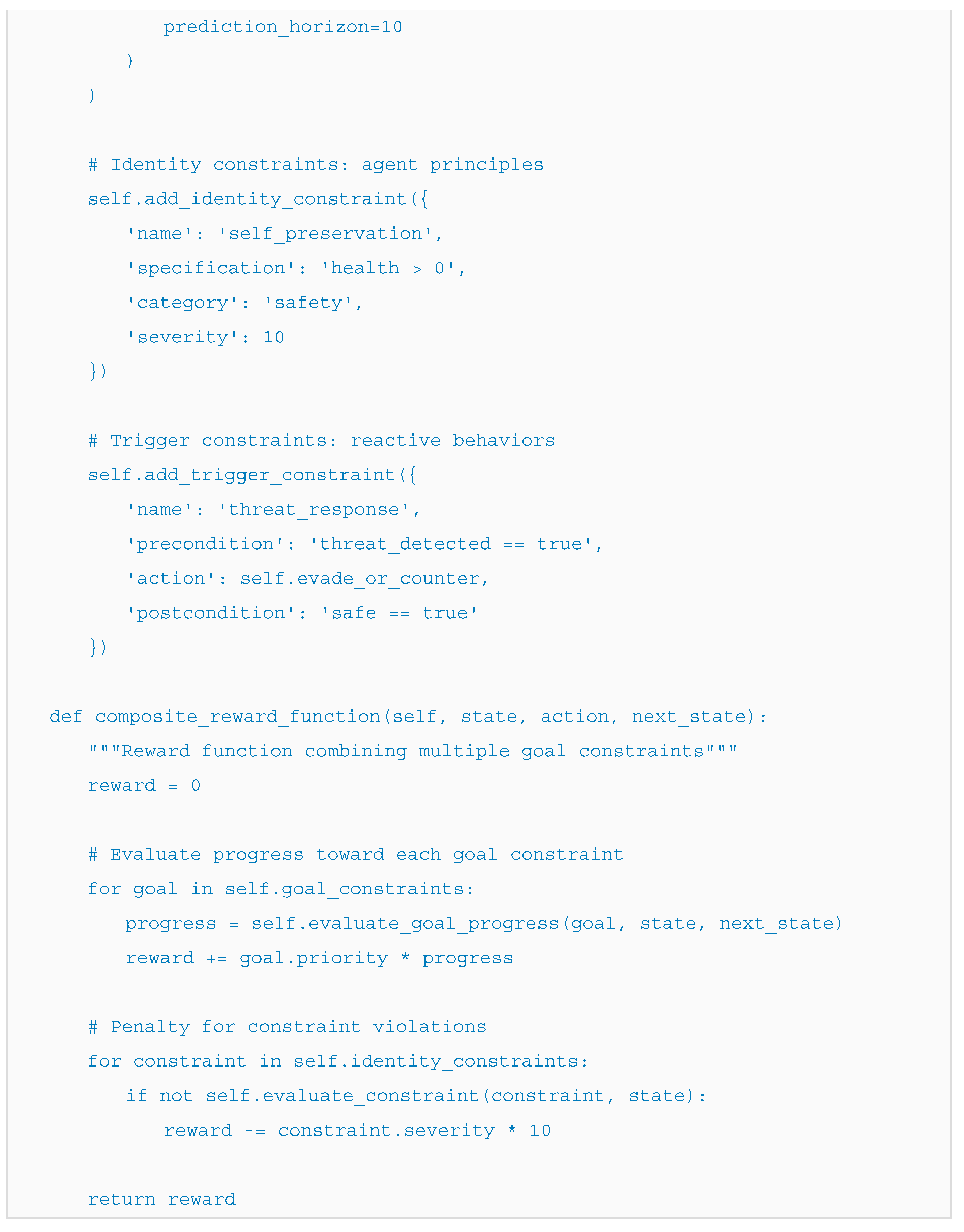

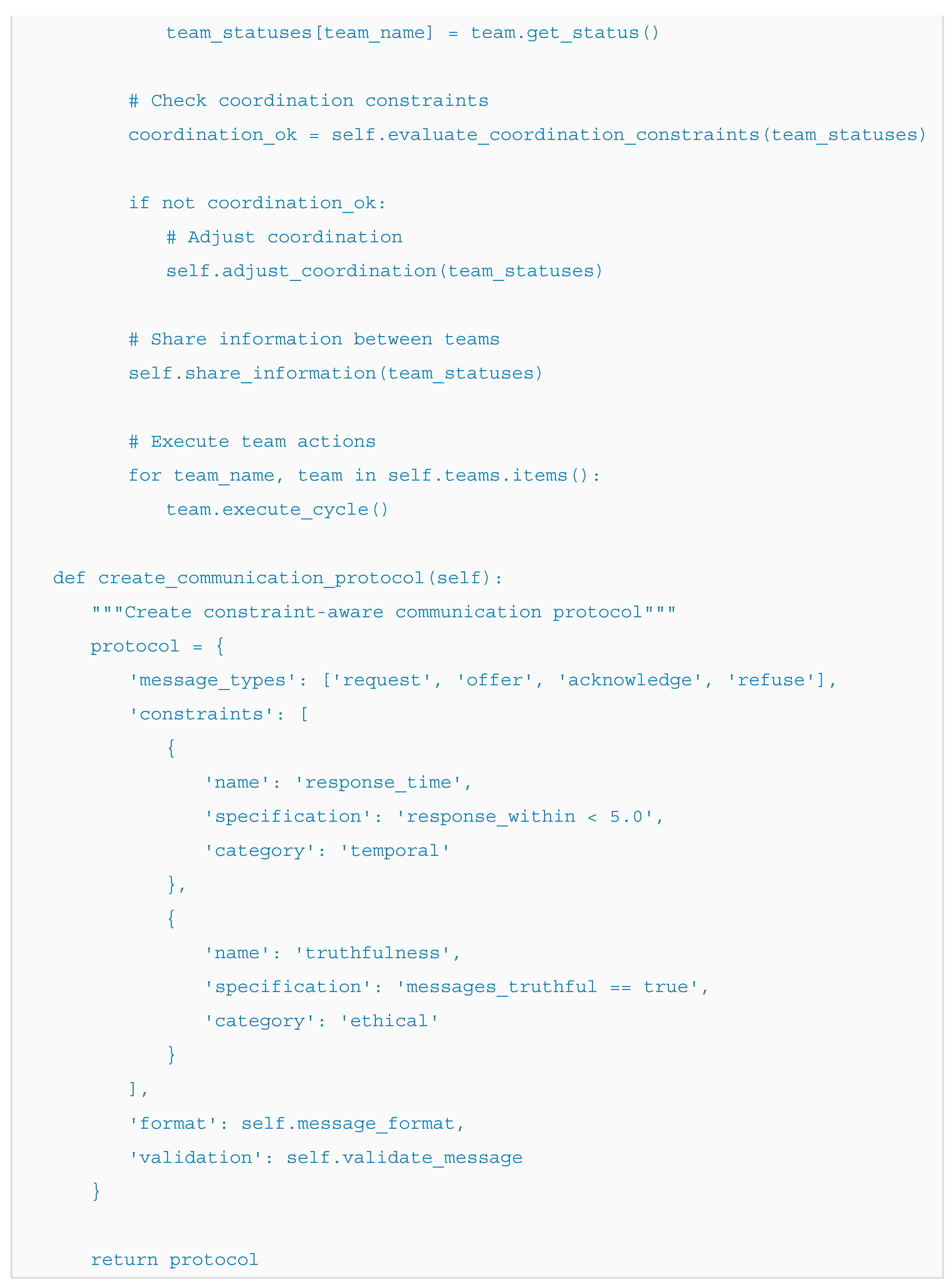

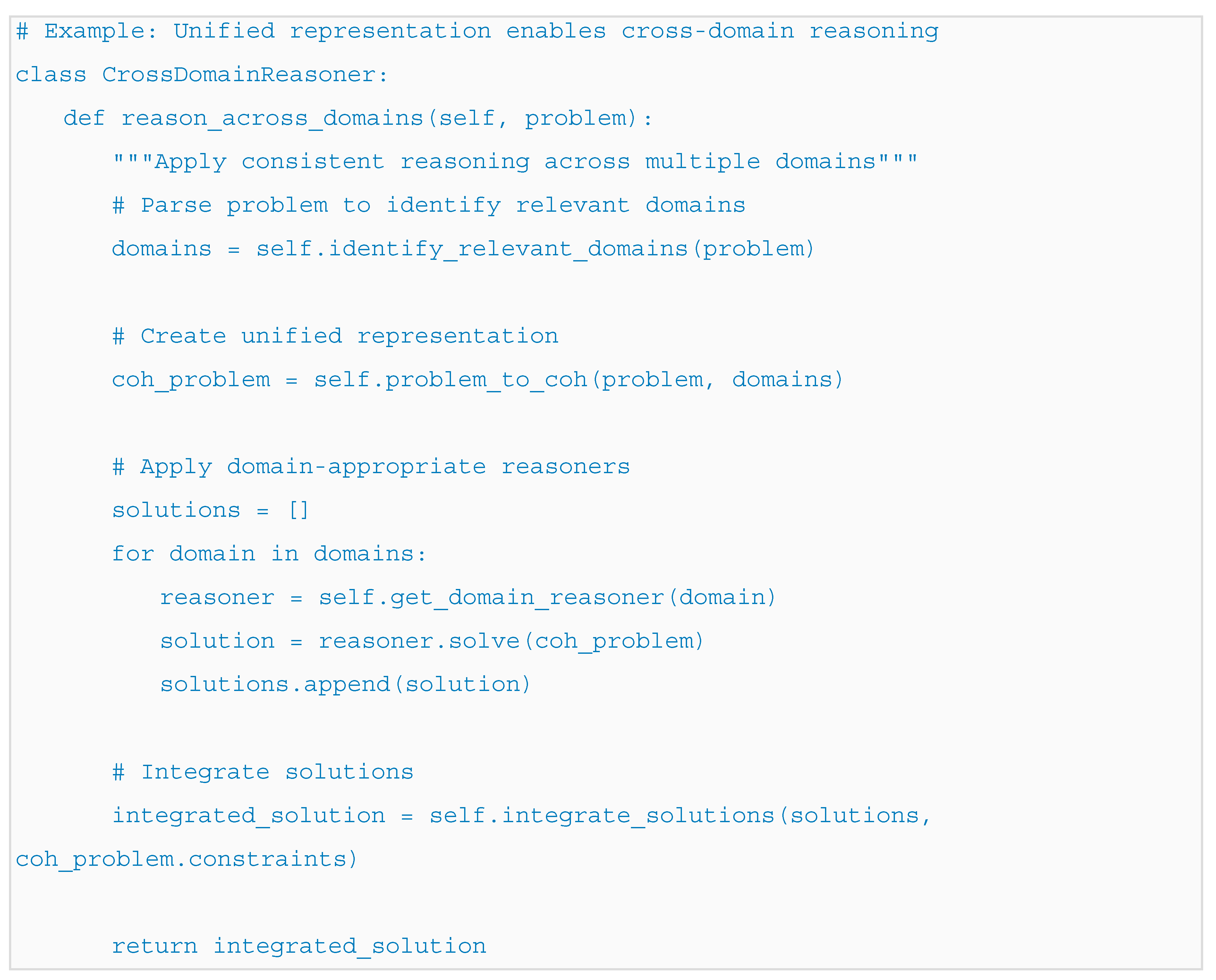

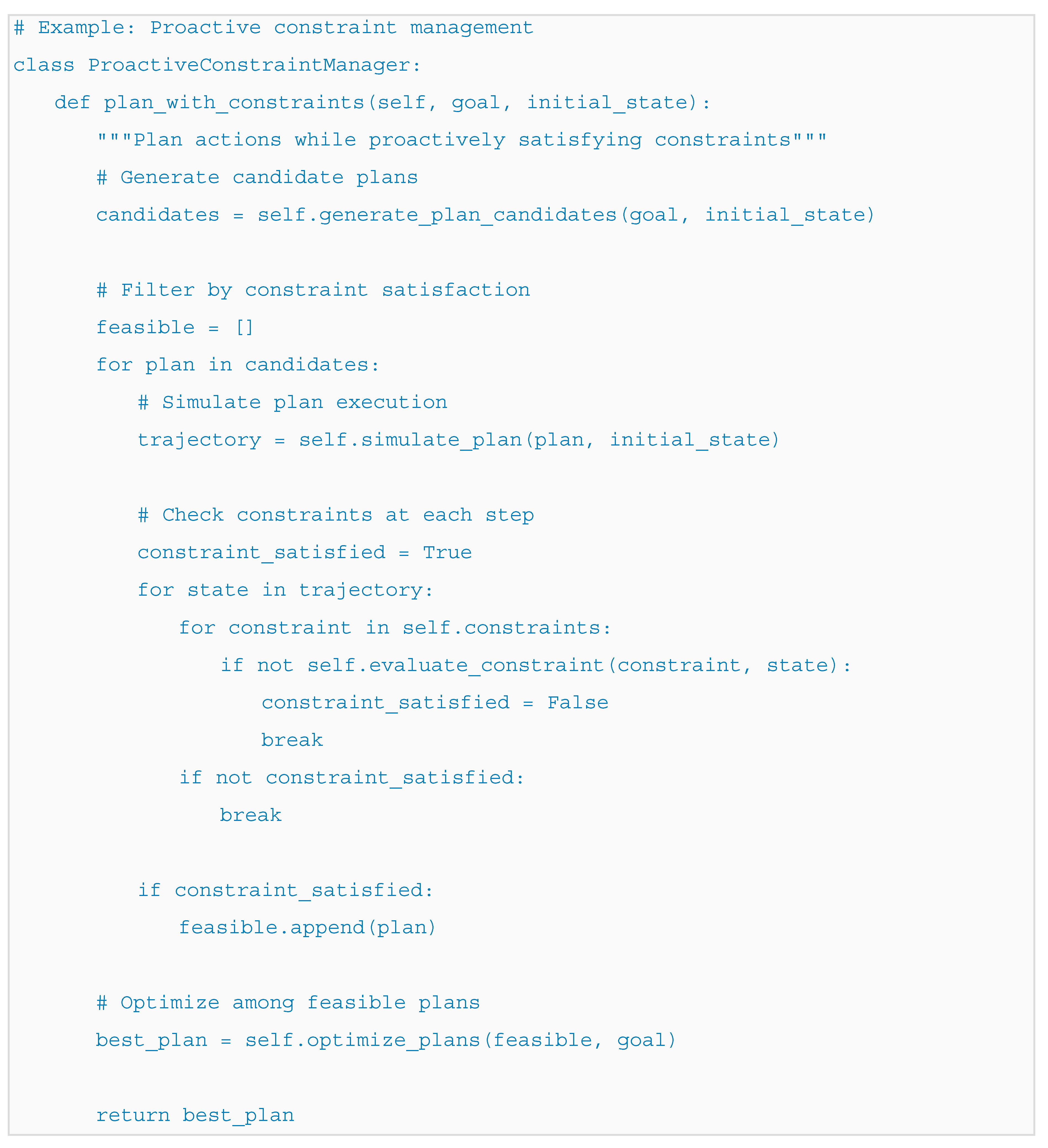

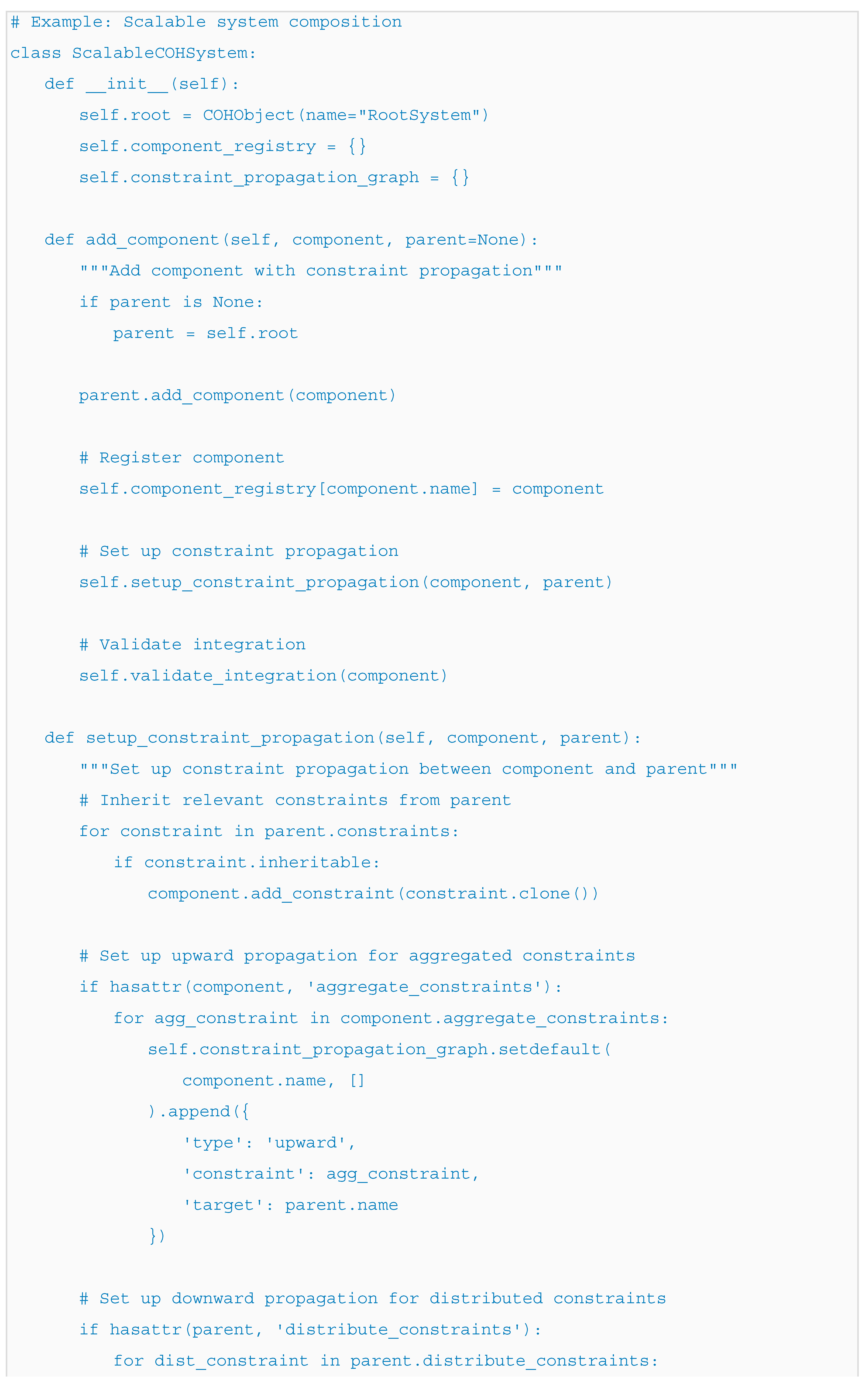

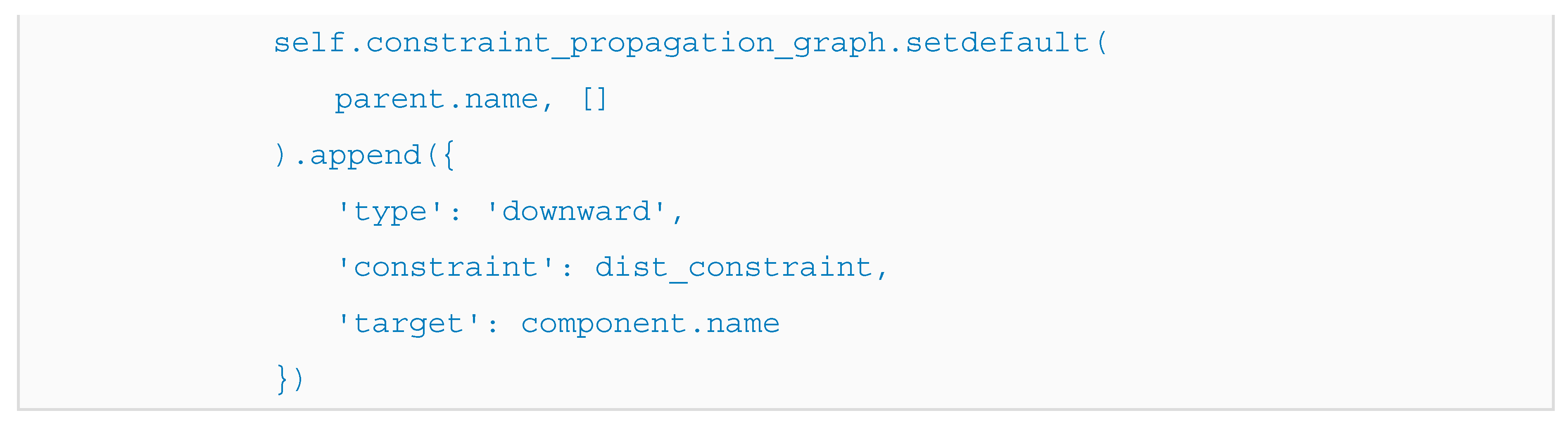

5. Implementing COH Models into Executable Live Applications

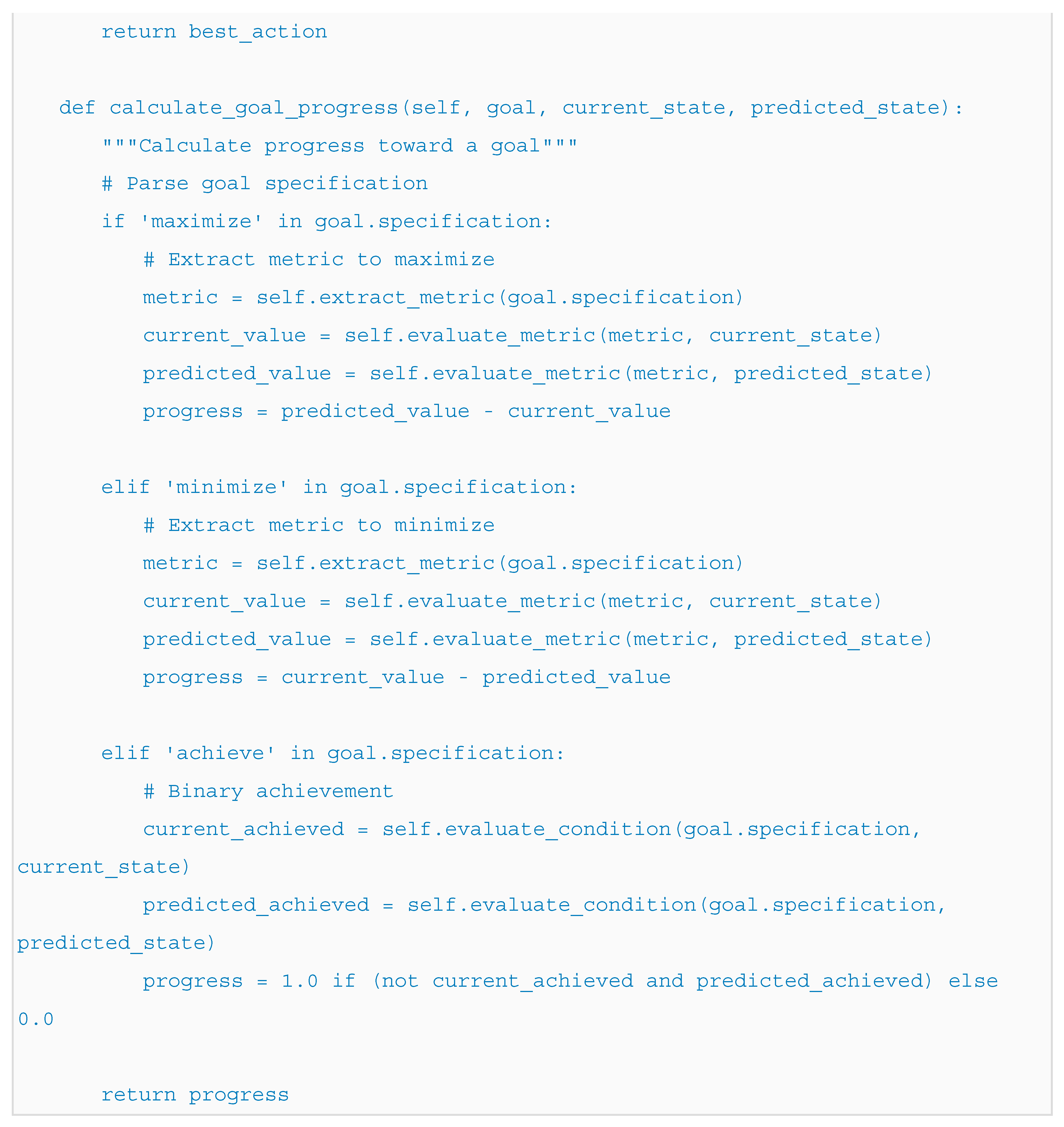

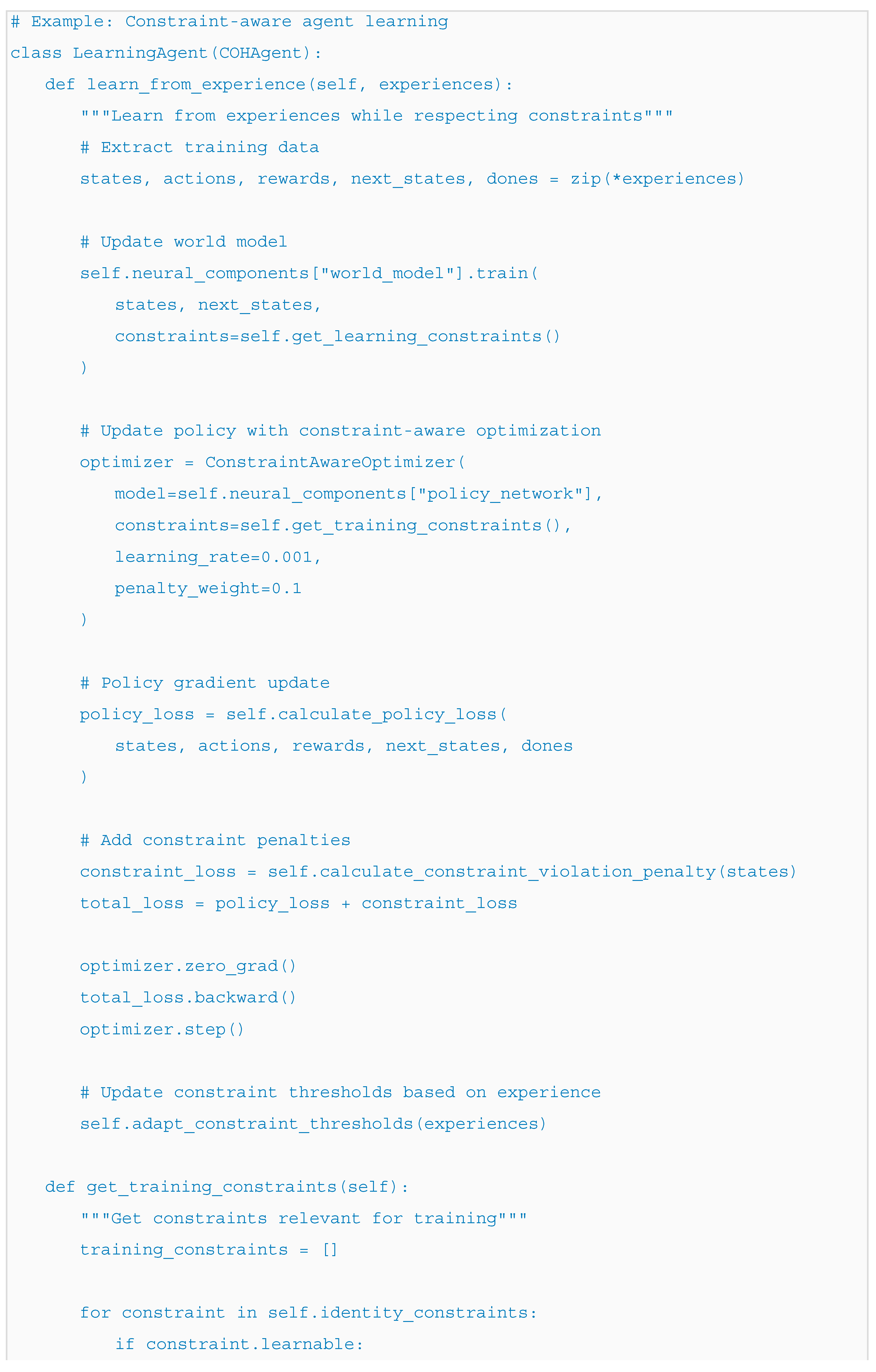

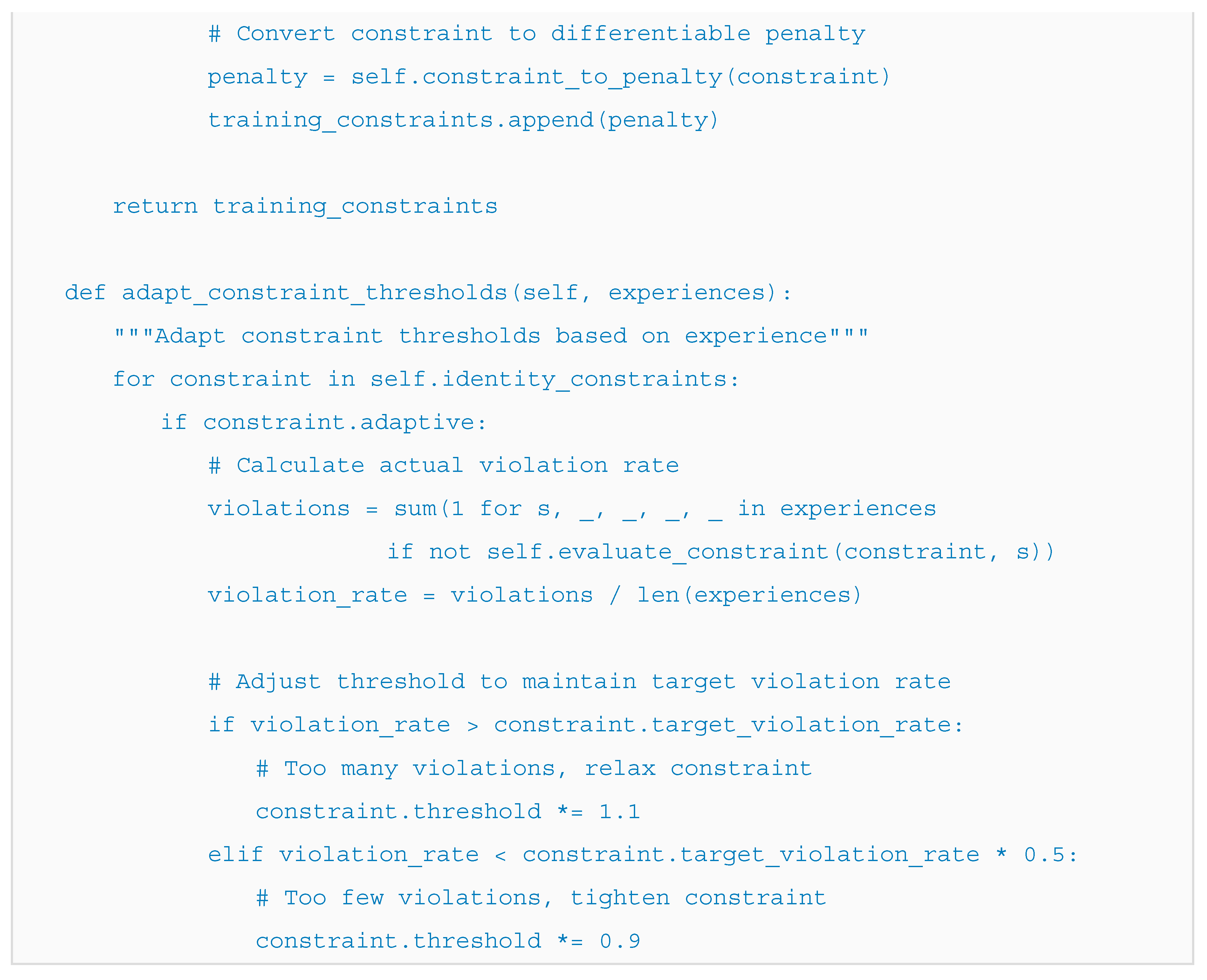

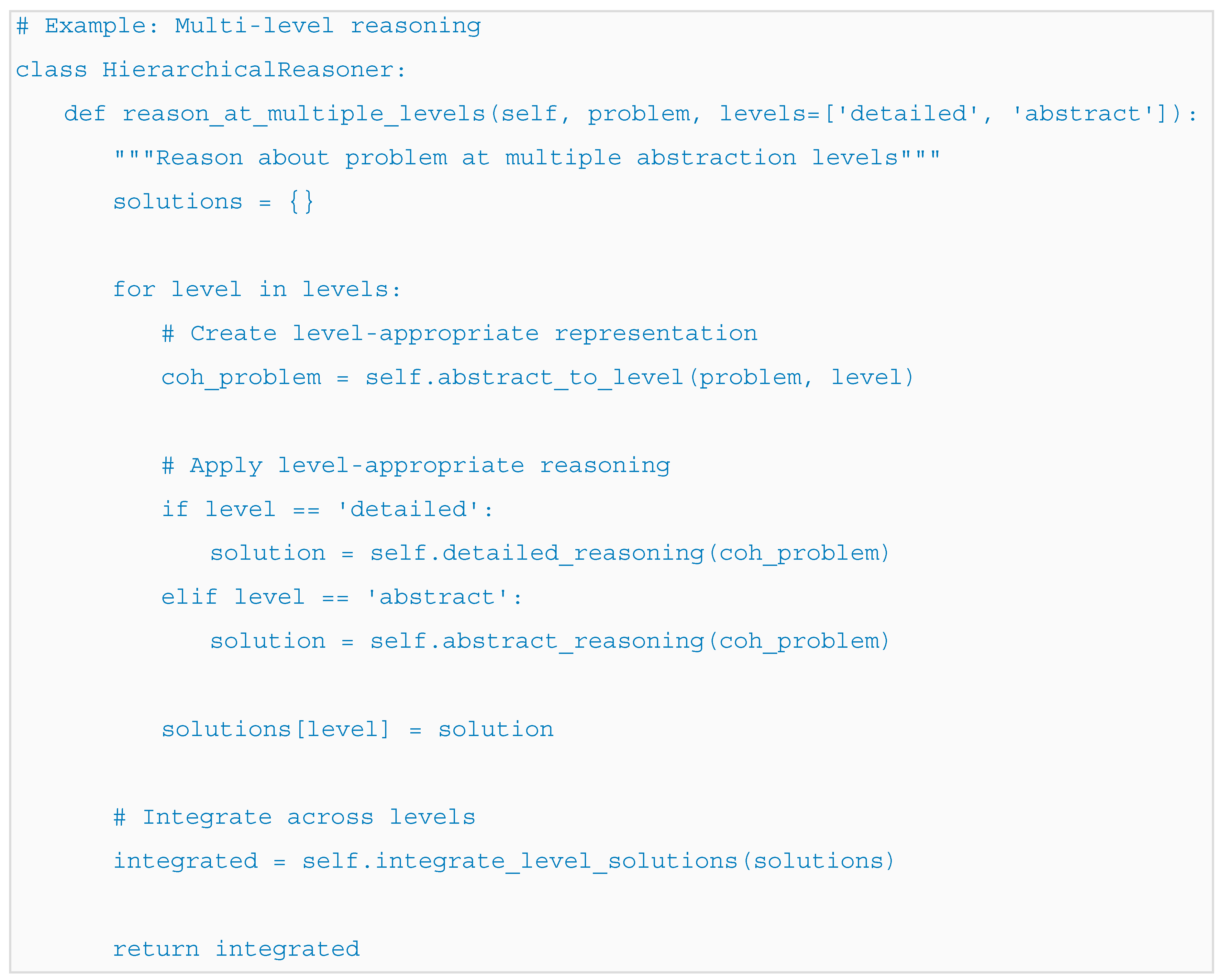

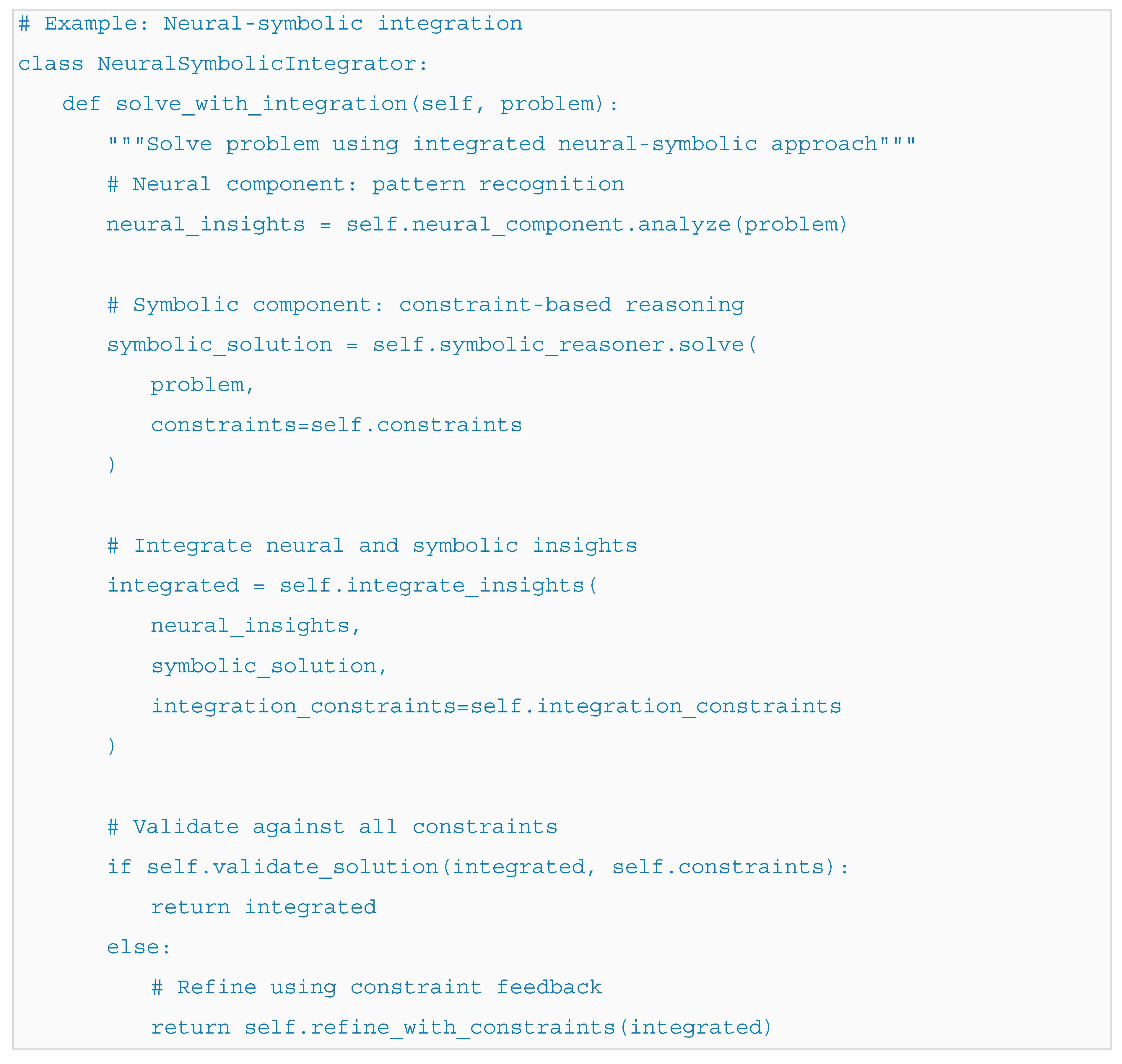

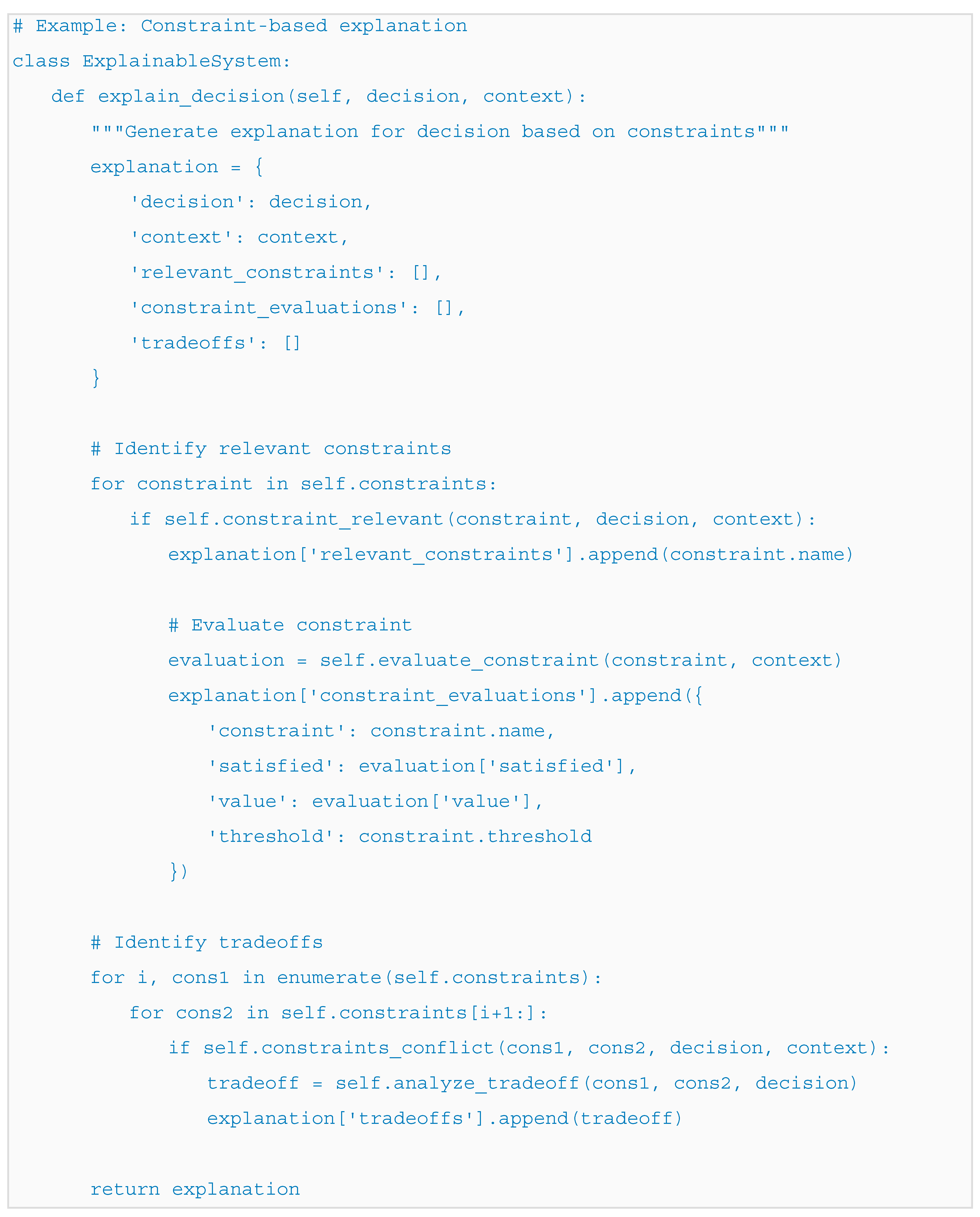

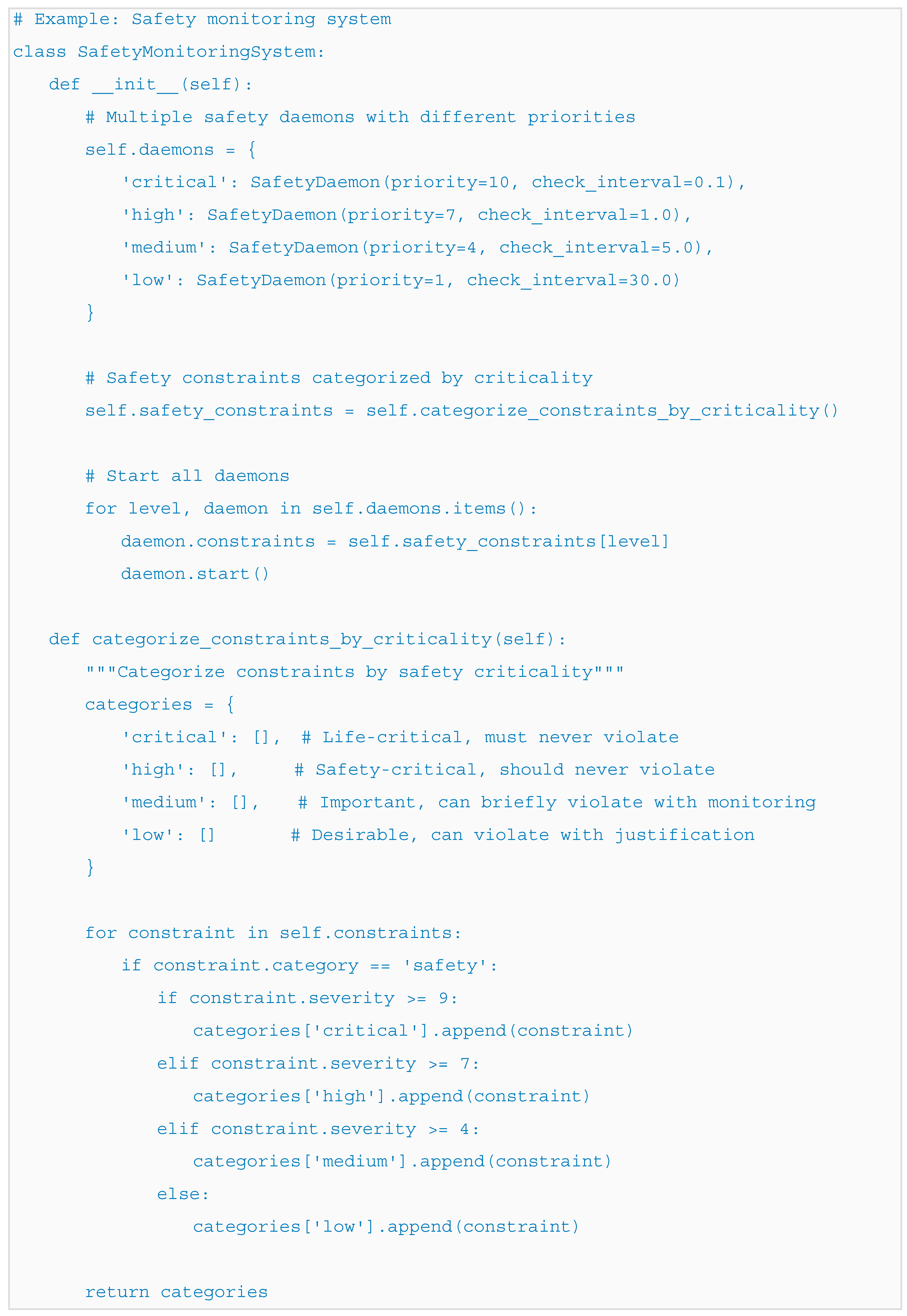

The transition from COH theoretical models to executable GISMOL systems follows a systematic implementation pattern that preserves constraint integrity while enabling adaptive behavior. This section demonstrates the implementation process through comprehensive examples.

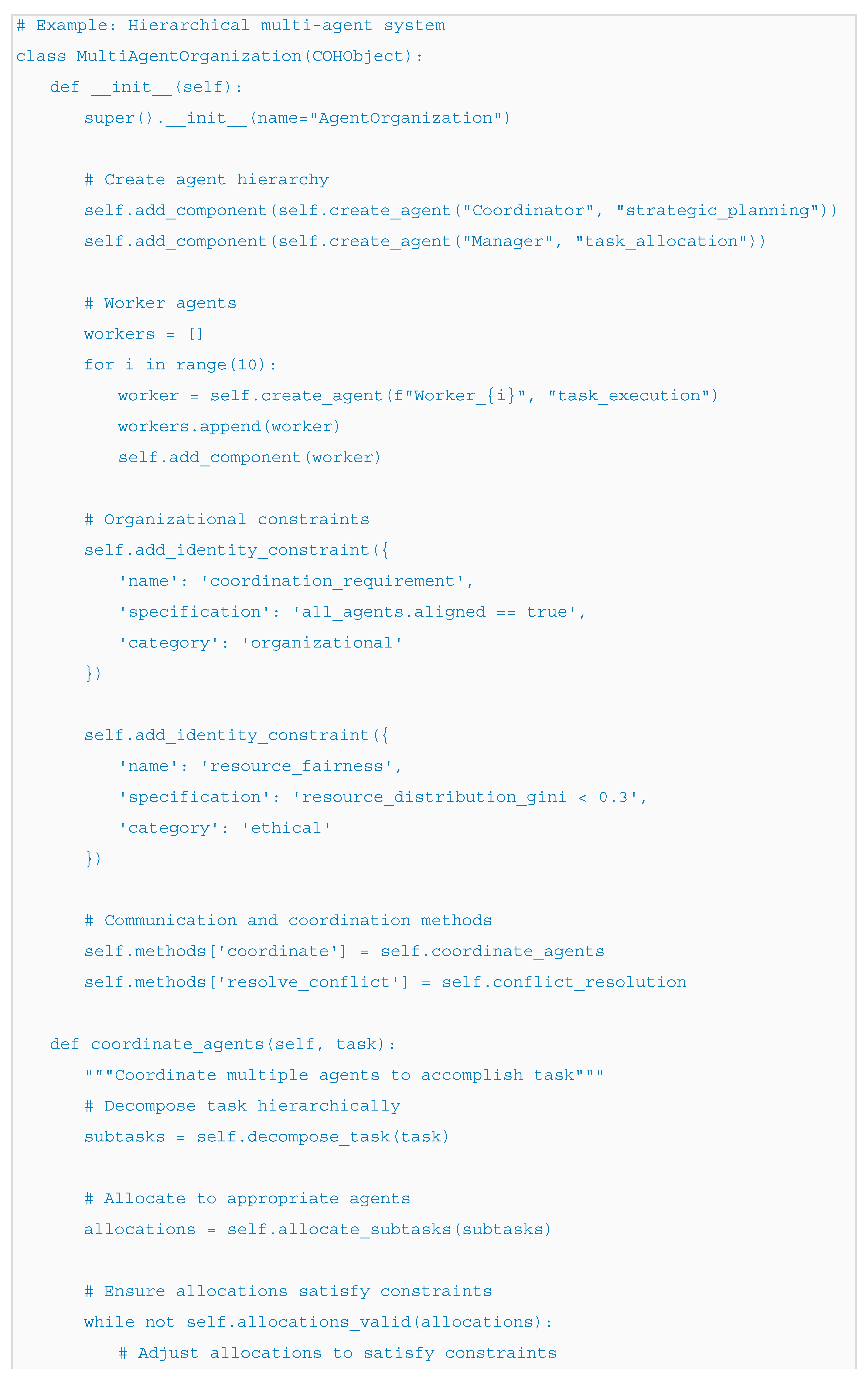

Implementation Architecture: GISMOL implements COH models through four core modules: gismol.core for object representation, gismol.neural for adaptive components, gismol.reasoners for constraint evaluation, and gismol.nlp for natural language interaction. The implementation maintains the 9-tuple structure while providing practical programming interfaces. Sample implementation of the Pandemic Response System can be found in the supplemental materials of the paper. In this section we will explain the key techniques involved in the implementation.

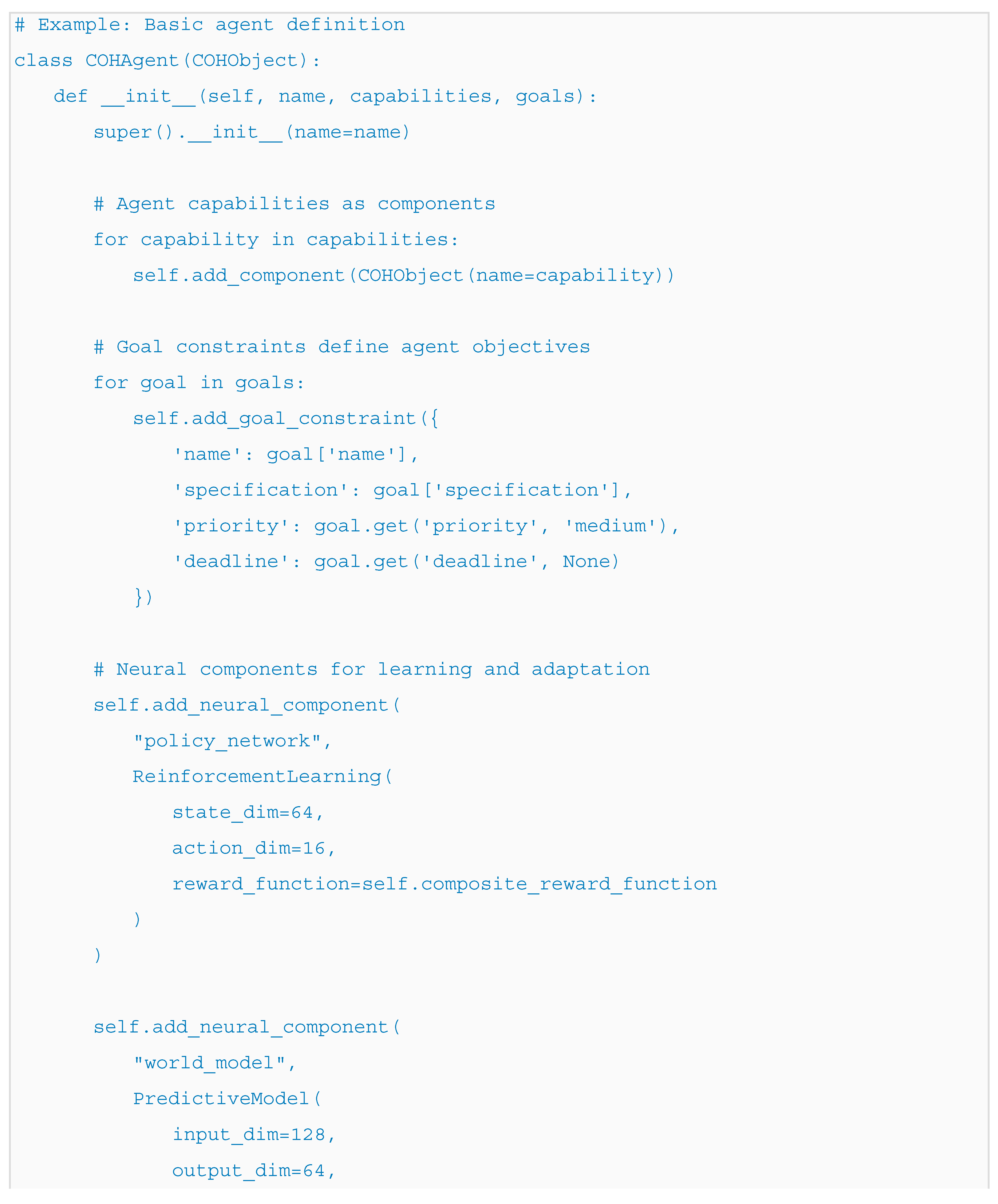

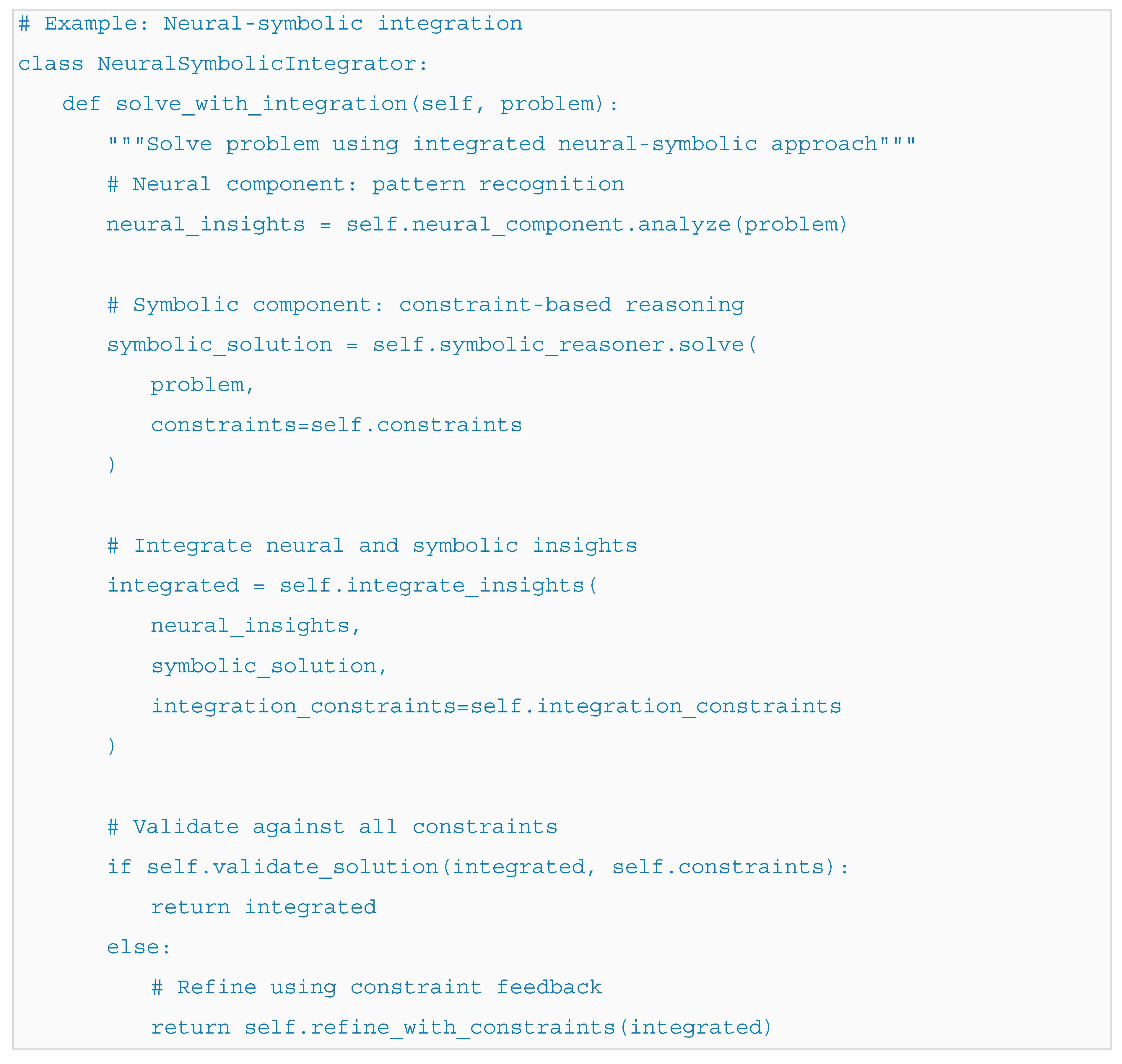

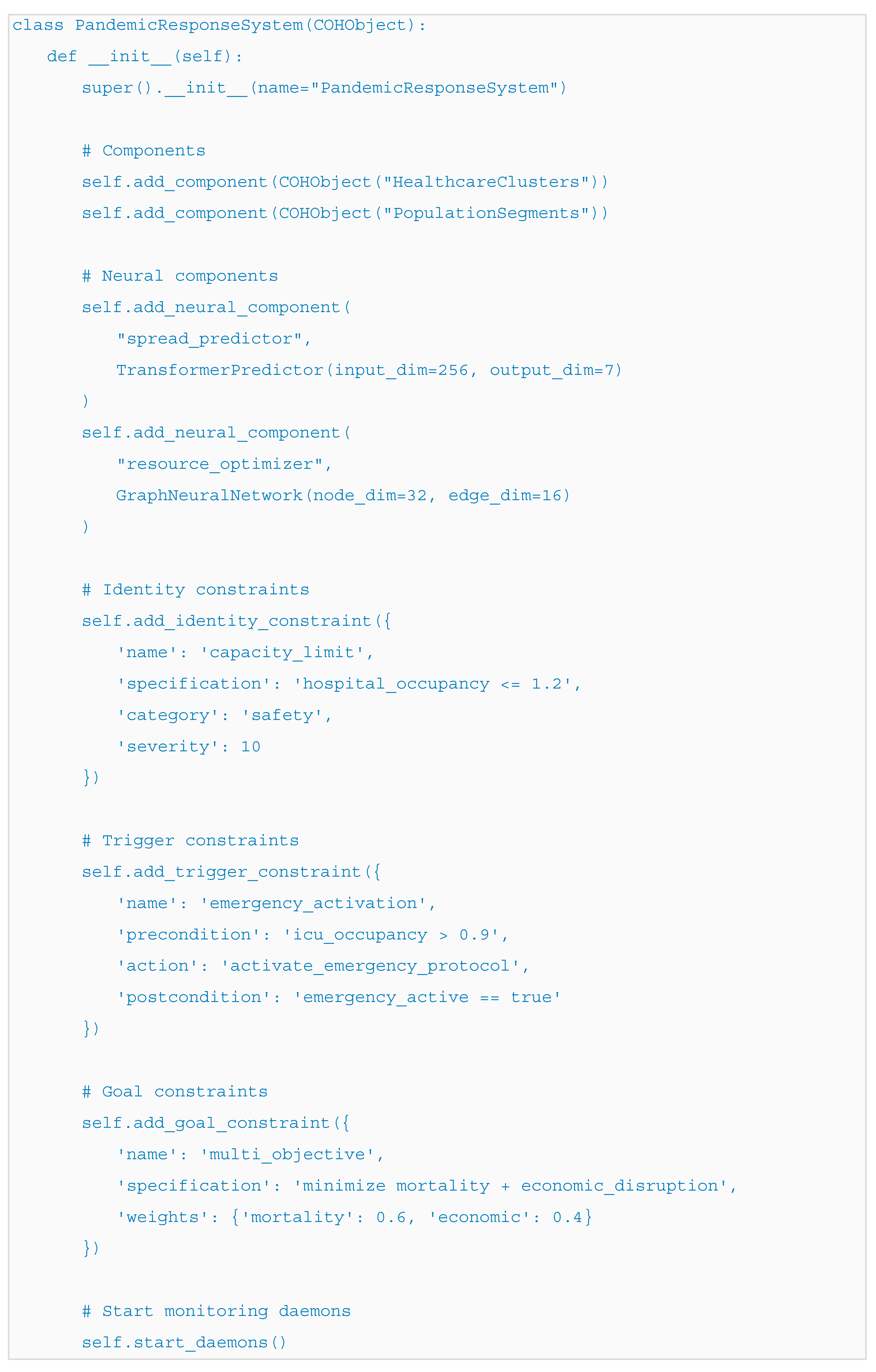

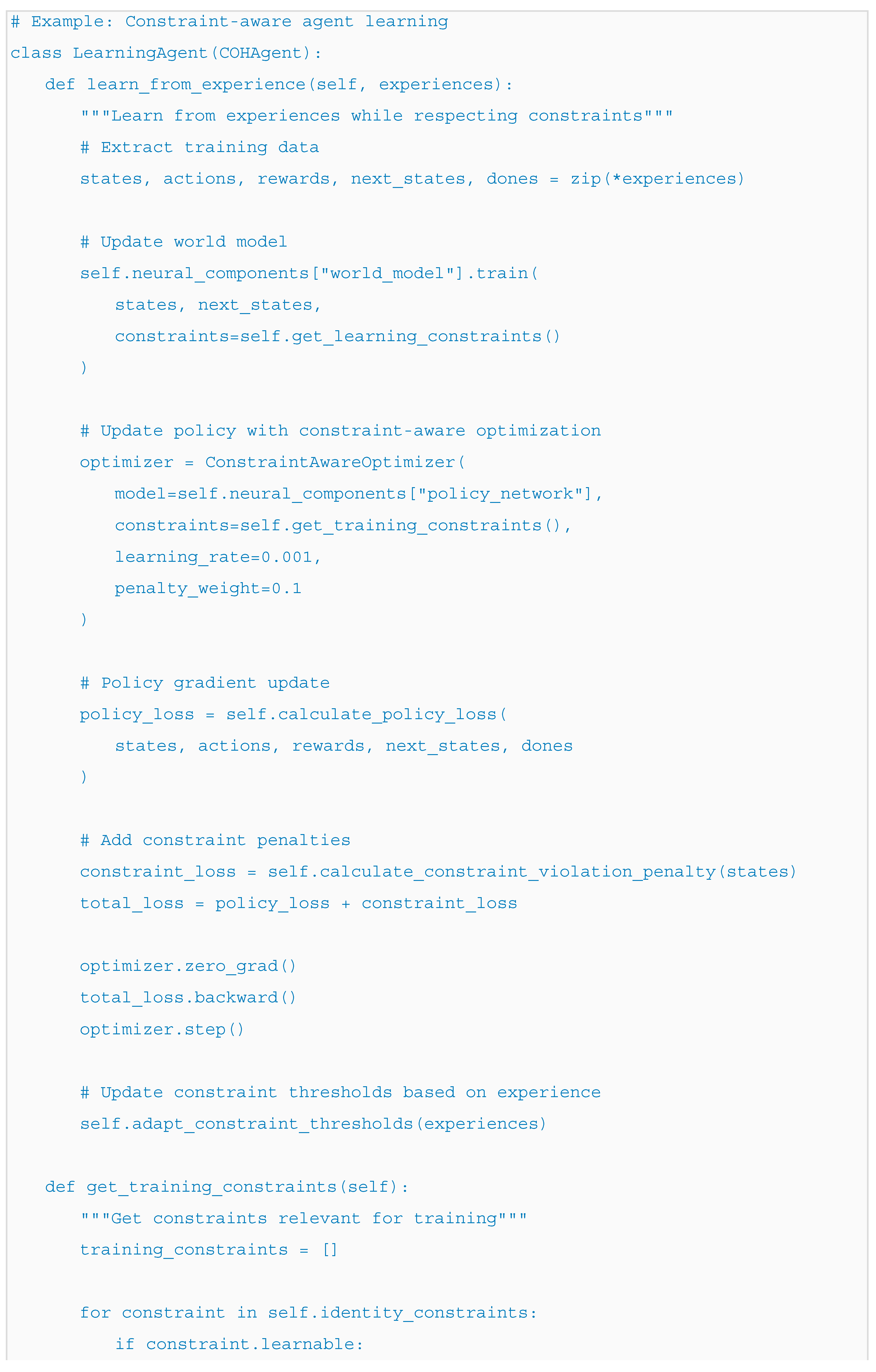

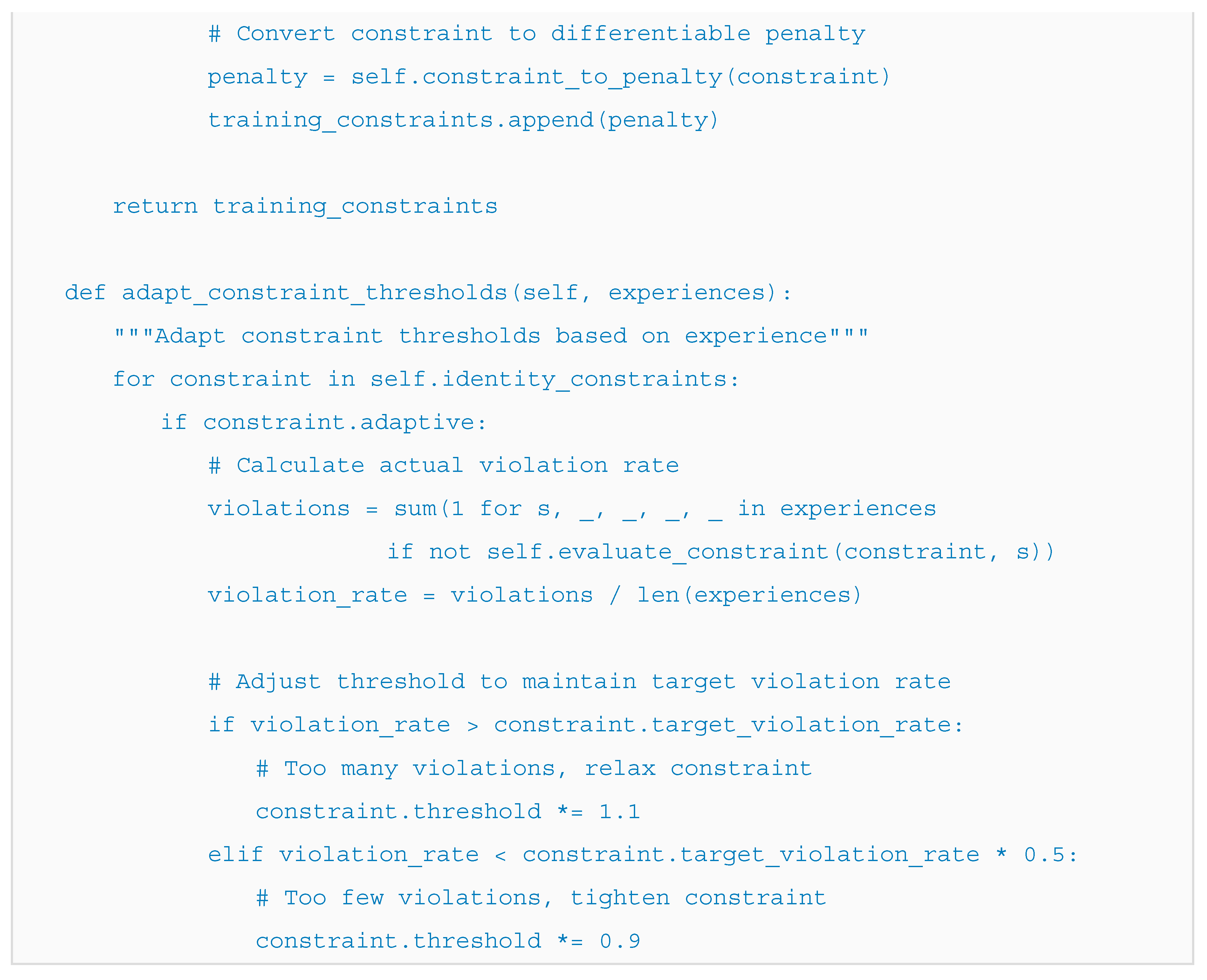

Neural Component Integration: Neural components in GISMOL are first-class COHObjects that participate in constraint validation. During training, ConstraintAwareOptimizer incorporates constraint violations as penalty terms. During inference, neural outputs are validated against relevant constraints before being accepted.

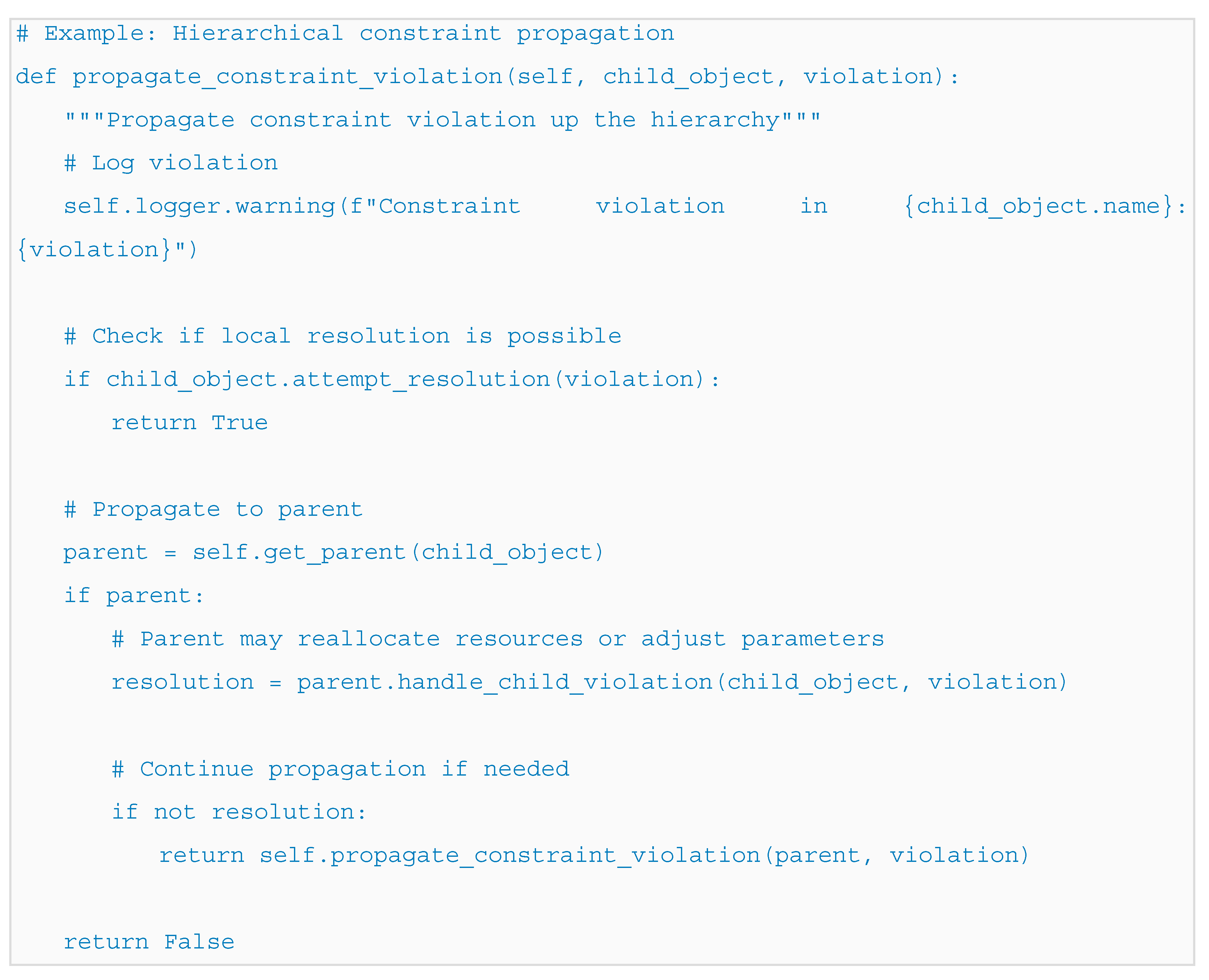

Constraint Propagation Mechanism: Constraints in hierarchical systems propagate through parent-child relationships. When a child object violates a constraint, it can trigger re-evaluation at parent level, potentially leading to reallocation or adaptation.

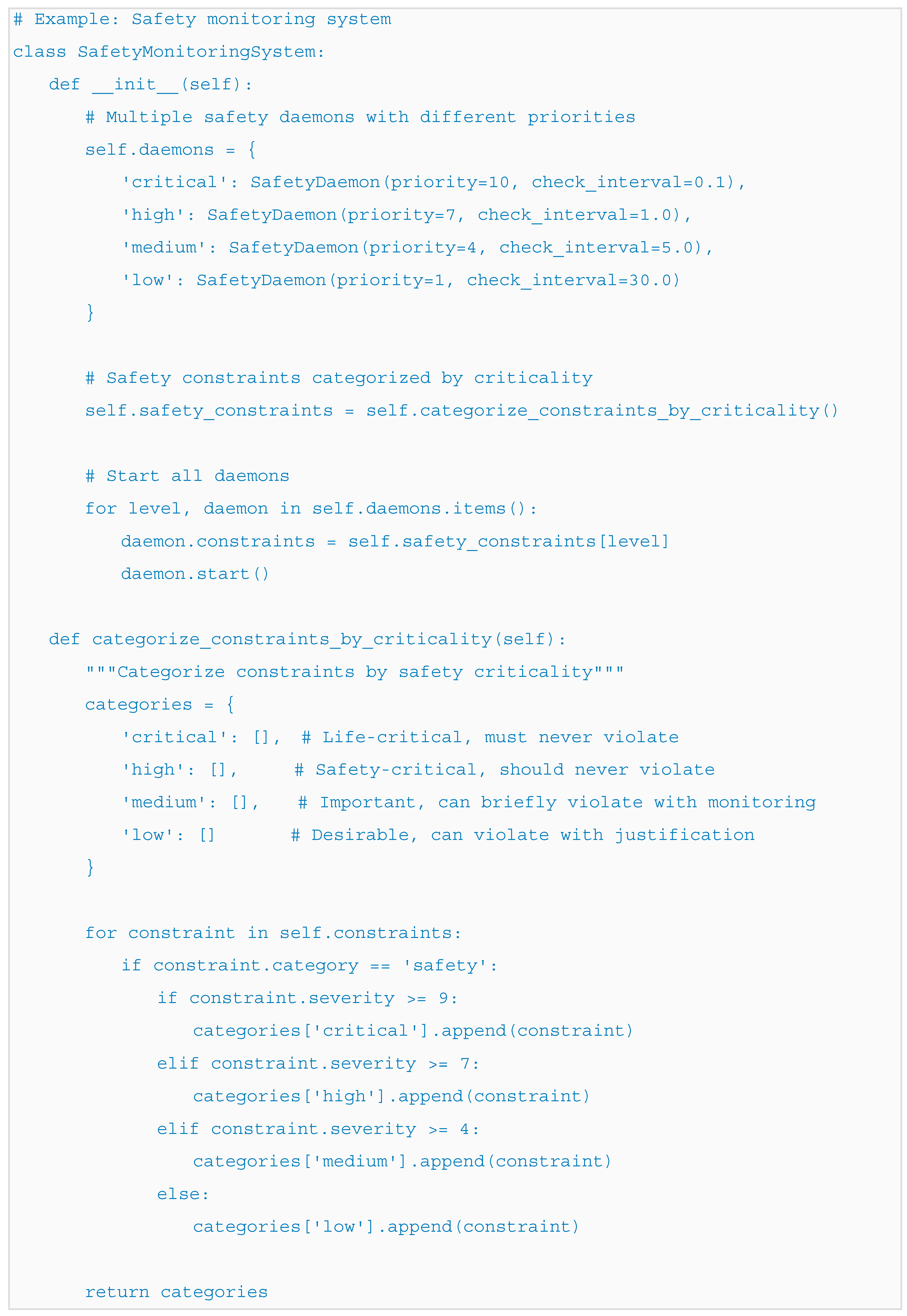

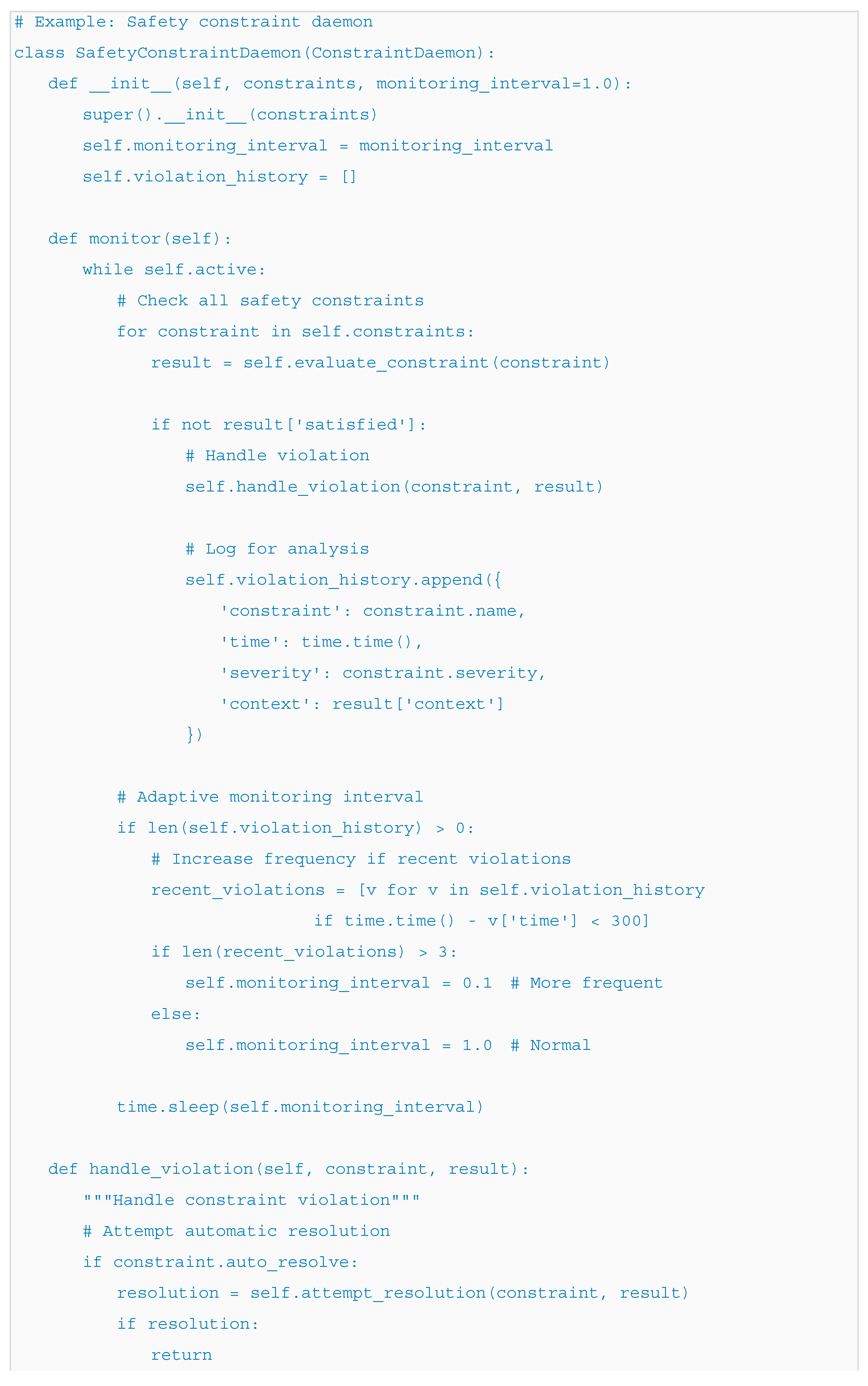

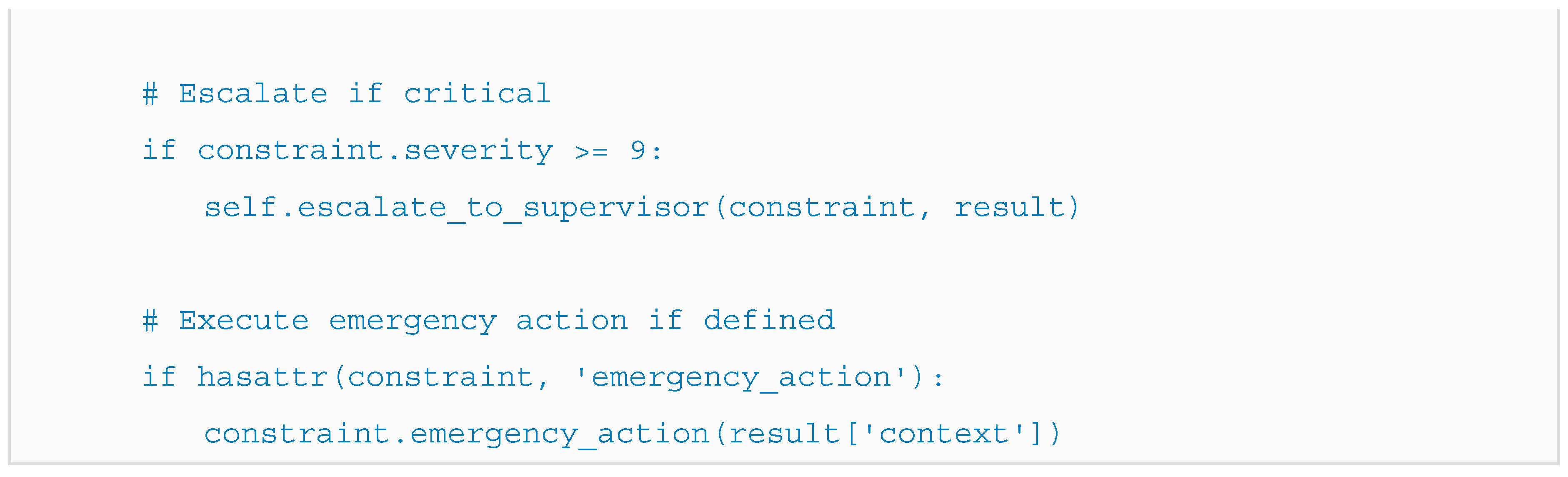

Real-time Monitoring with Daemons: Constraint daemons provide continuous monitoring with configurable sensitivity. They can operate at different frequencies based on constraint criticality and system state.

This implementation approach ensures that COH models translate into executable systems that maintain theoretical properties while providing practical functionality. The hierarchical structure enables scalable deployment, while constraint mechanisms ensure safety and reliability.

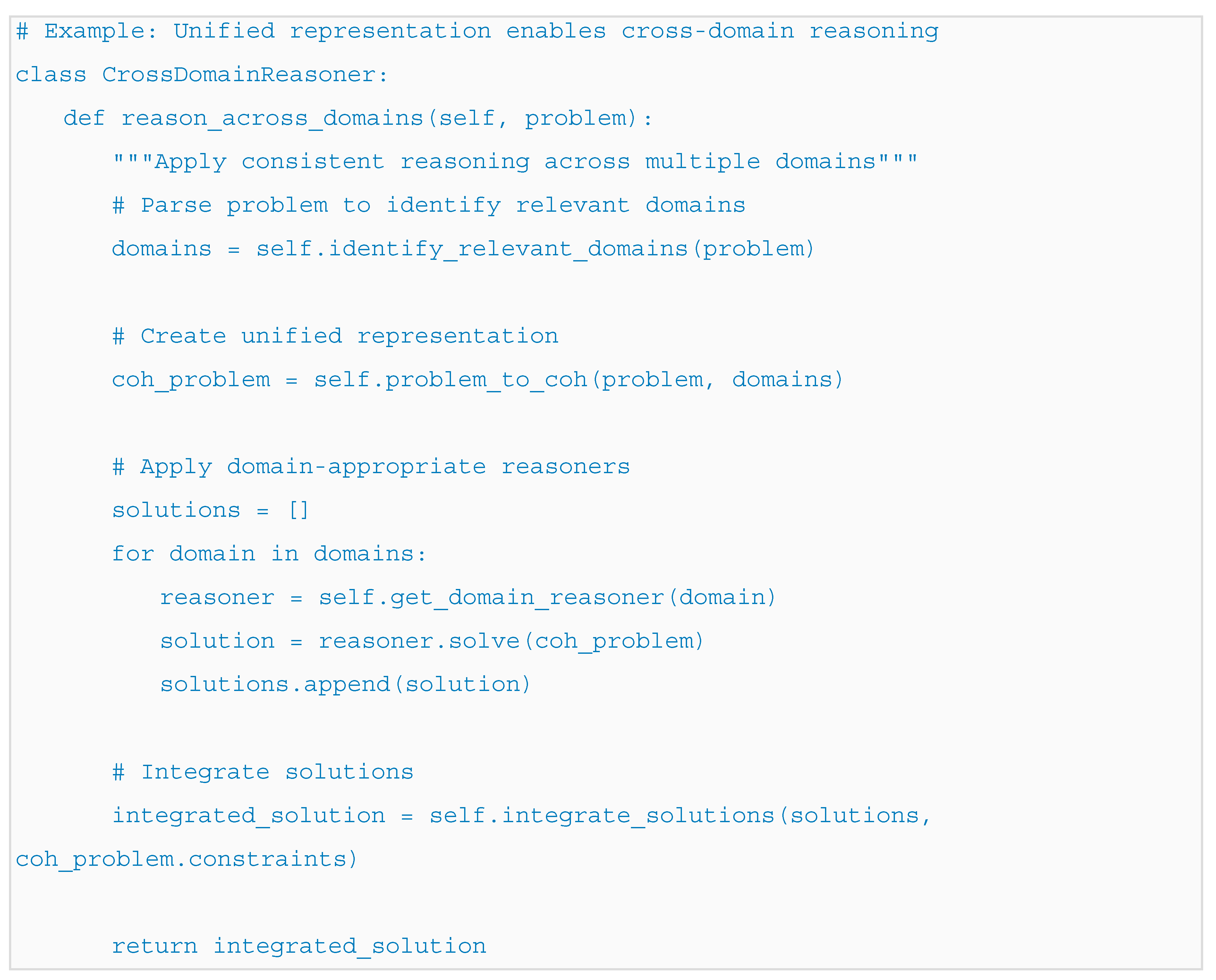

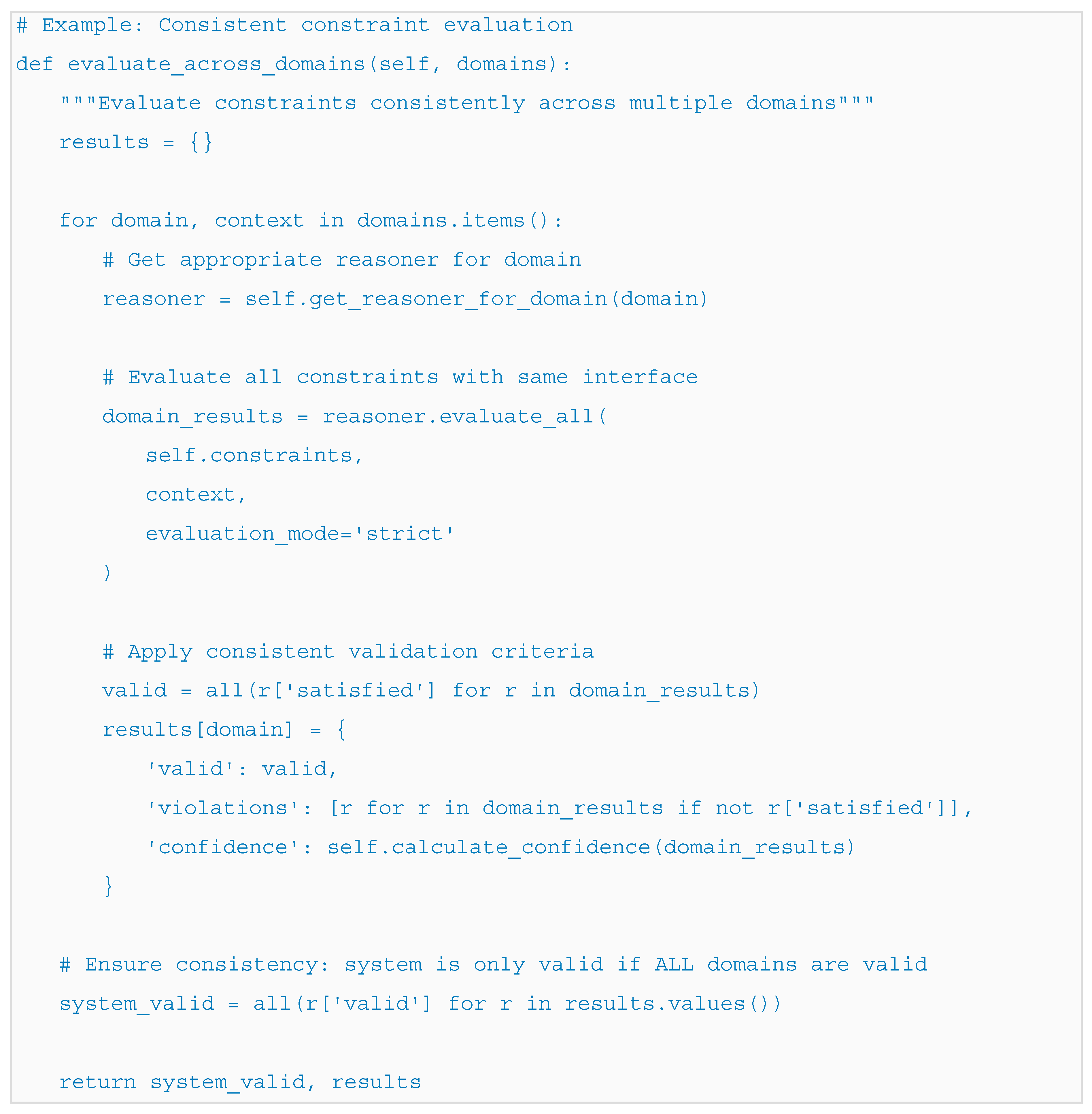

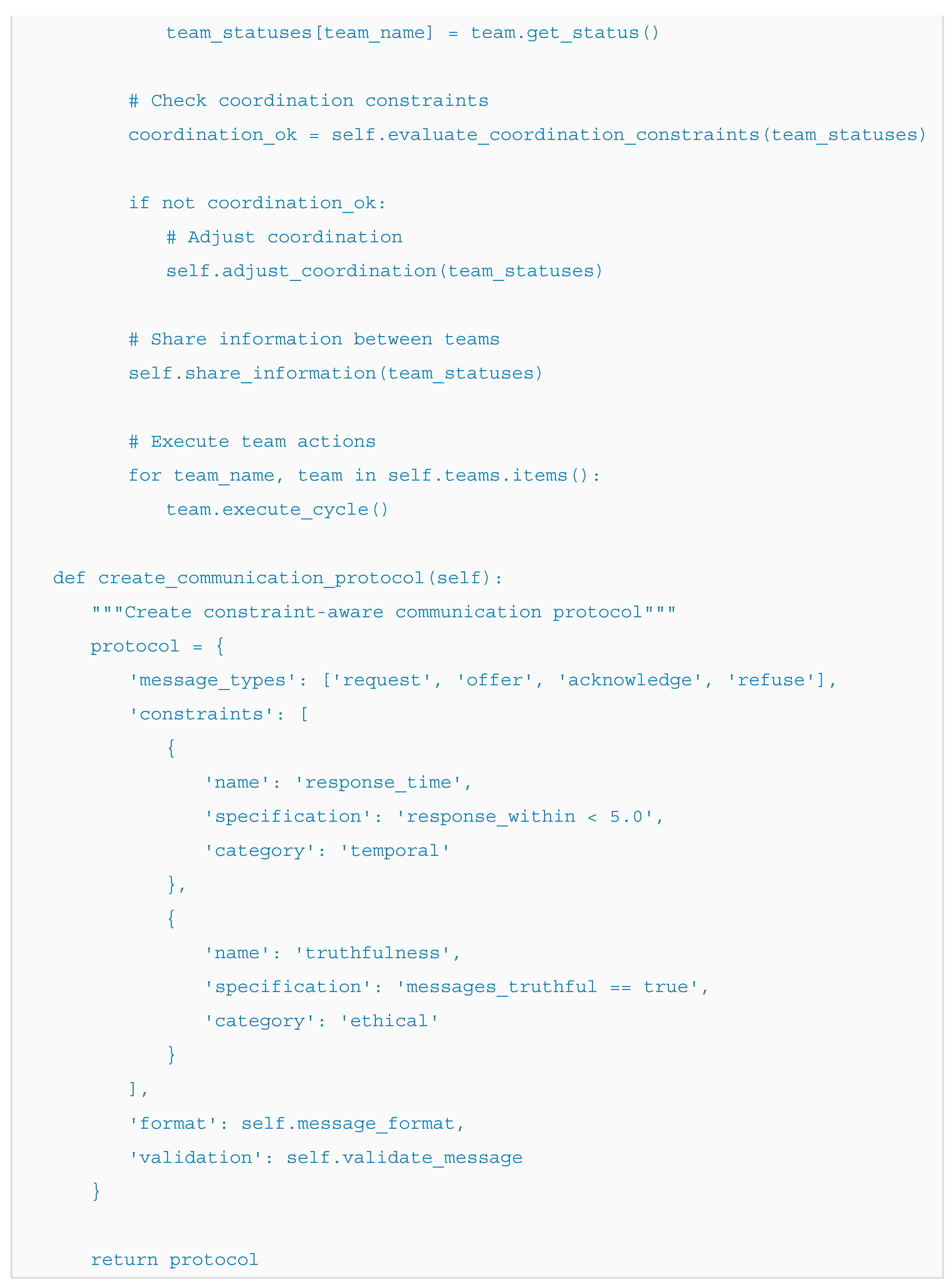

6. Avoiding "Jagged Intelligence" with COH/GISMOL

"Jagged intelligence" refers to the inconsistent performance of AI systems across different domains or task types, where a system may excel in one area but fail catastrophically in another [

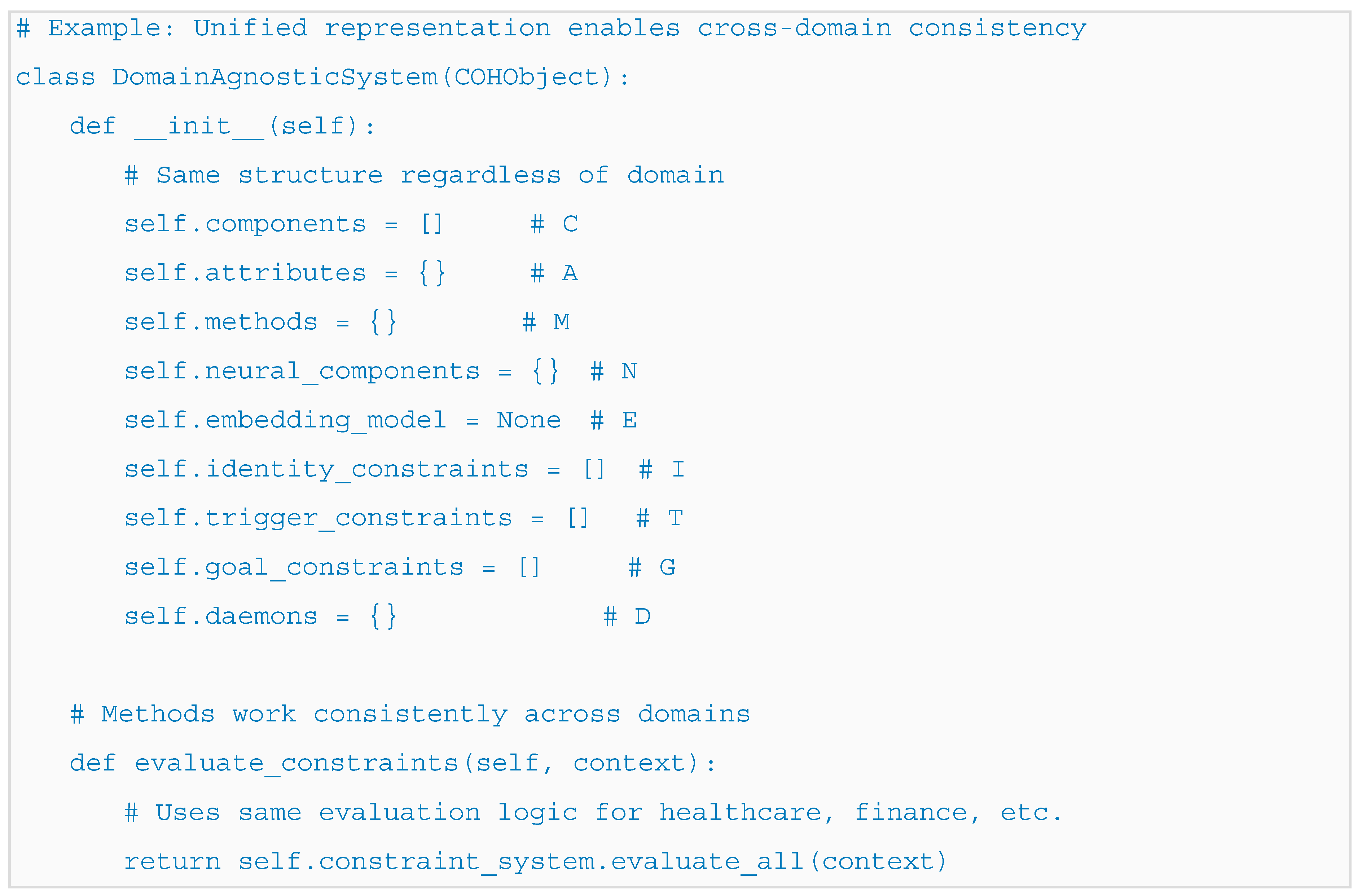

17]. This problem arises from several factors: lack of unified representation, inconsistent constraint enforcement, and domain-specific optimization that doesn't generalize. COH/GISMOL addresses these issues through several key mechanisms.

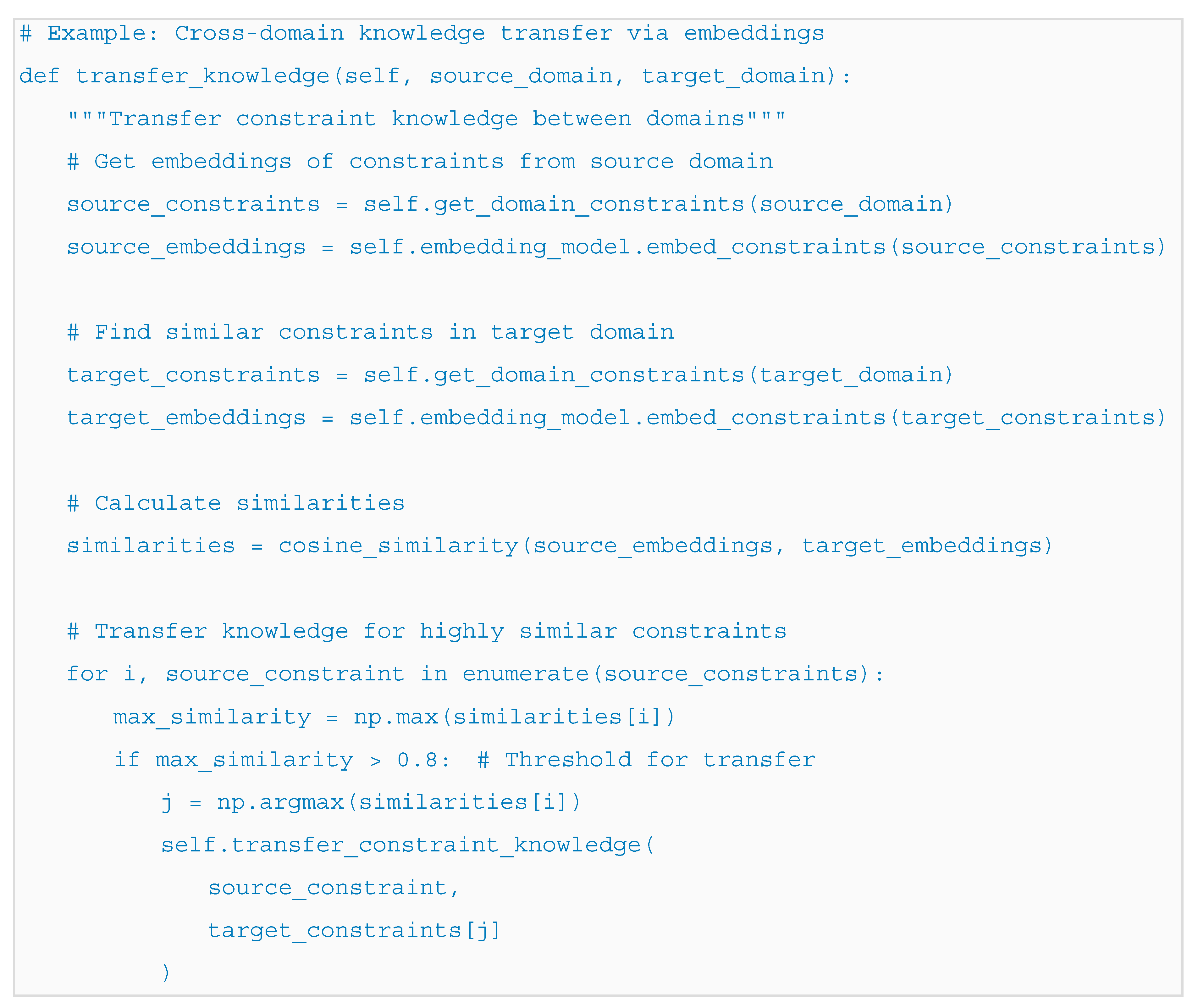

Unified Representation Across Domains: COH provides a consistent 9-tuple representation that applies equally to all domains. This uniformity ensures that systems developed for different applications share common structure and semantics, enabling knowledge transfer and consistent behavior.

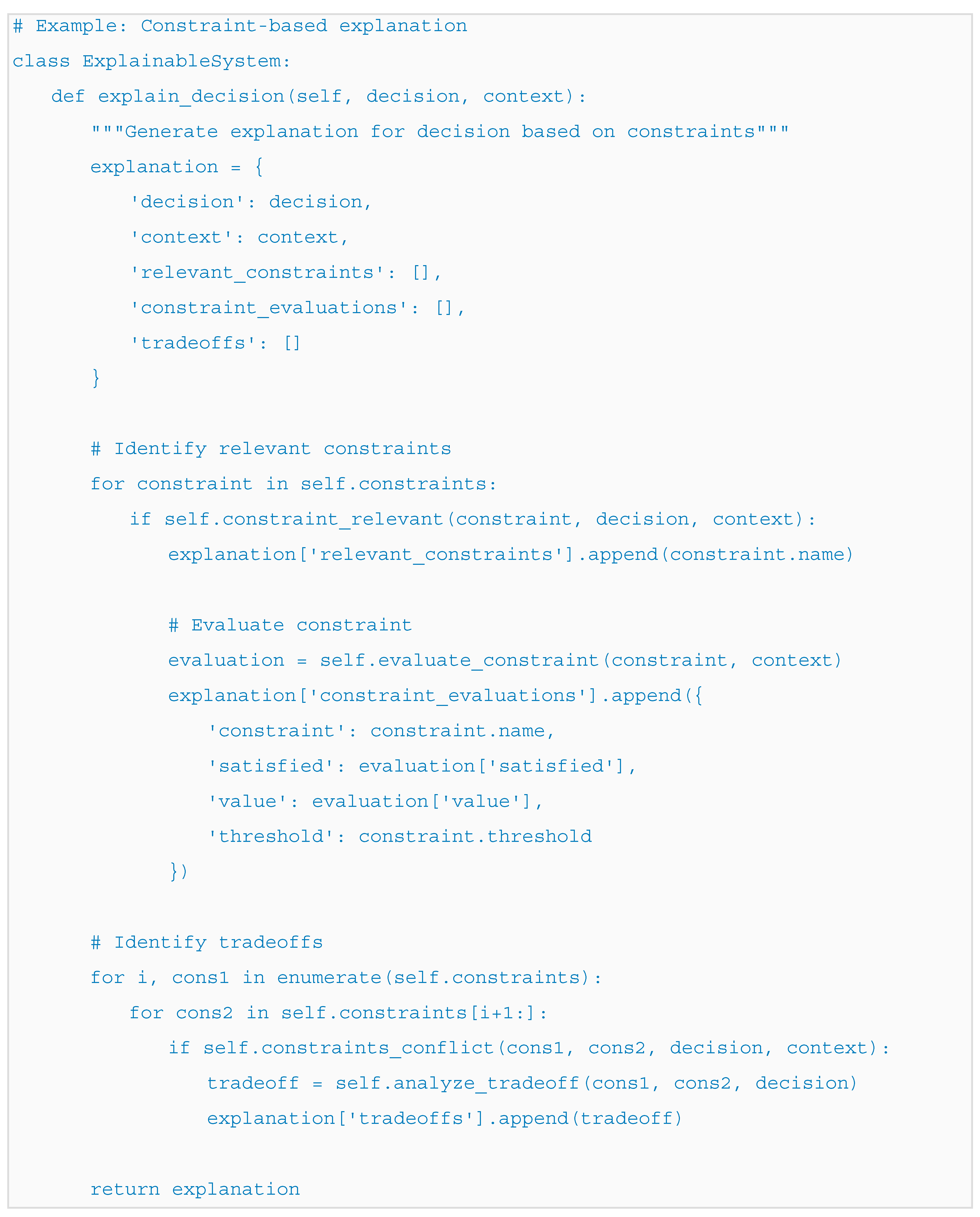

Consistent Constraint Enforcement: The constraint system in GISMOL ensures that rules are applied uniformly regardless of context. Constraints are evaluated using specialized reasoners that understand domain semantics but follow consistent evaluation protocols.

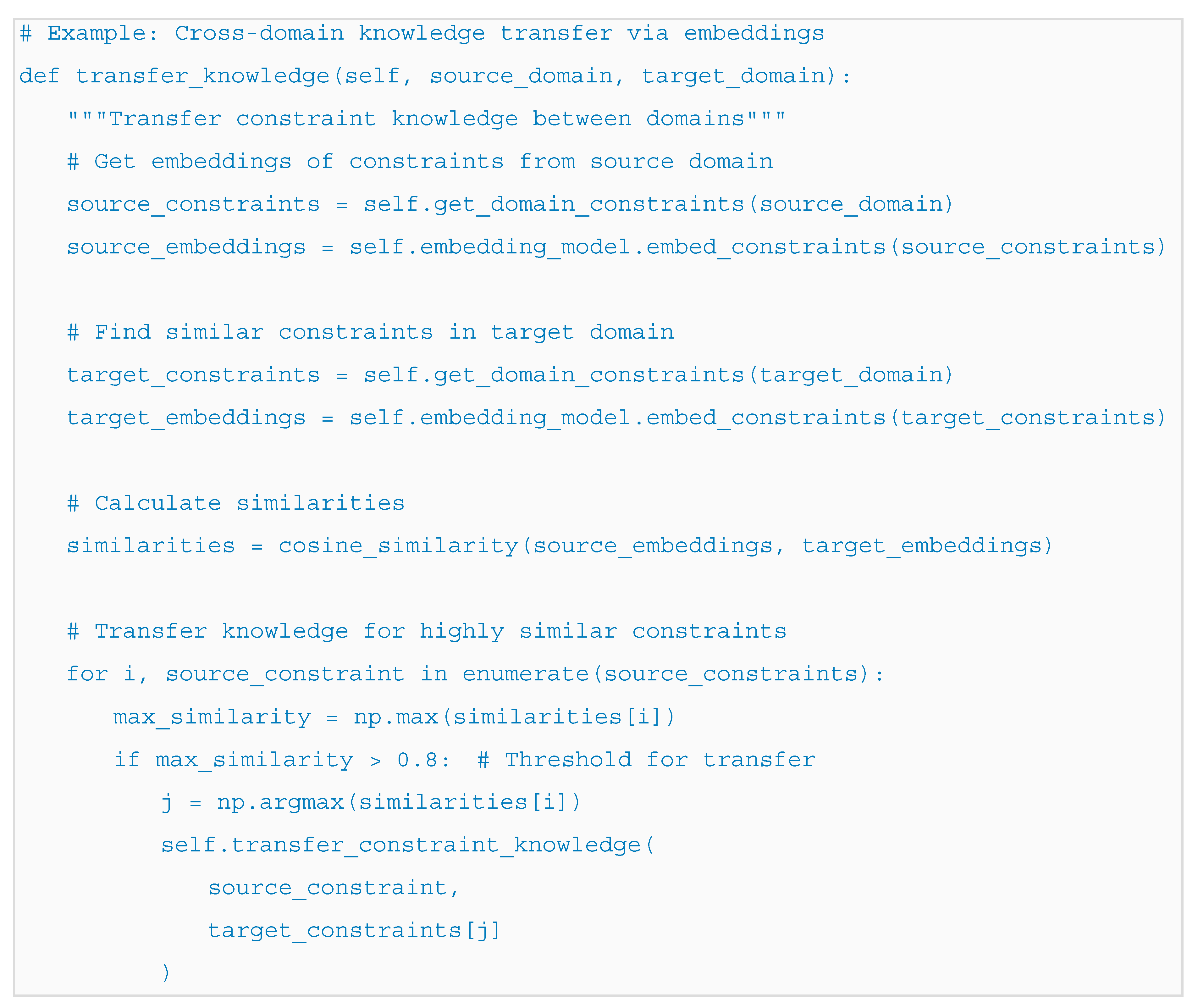

Cross-Domain Knowledge Transfer: The embedding component (E) creates a unified semantic space that enables knowledge transfer between domains. Similarities in constraint structures or component relationships can be recognized and leveraged.

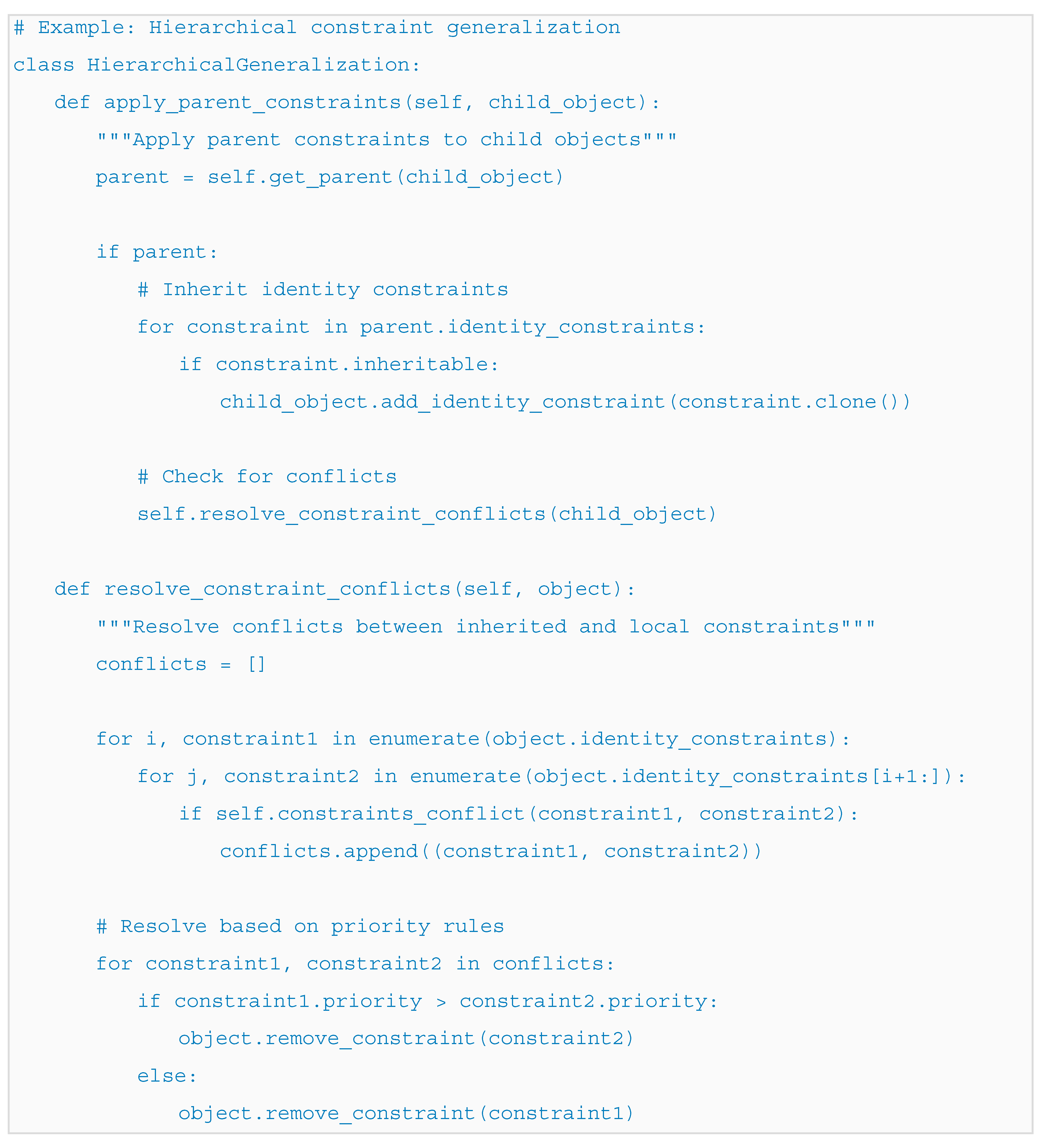

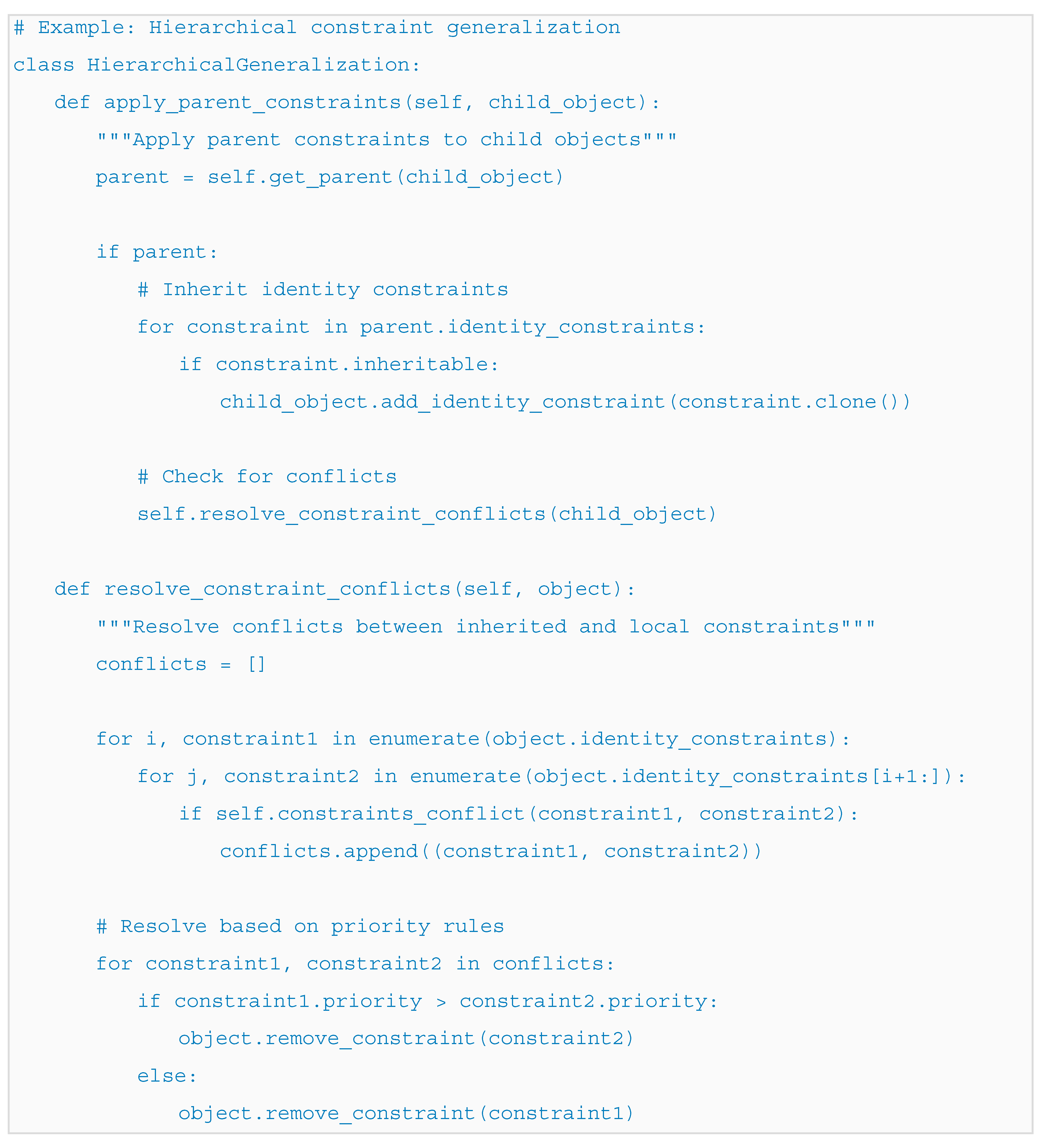

Hierarchical Generalization: The compositional hierarchy enables generalization from specific instances to broader categories. Constraints defined at higher levels apply to all sub-components, ensuring consistent behavior across the hierarchy.

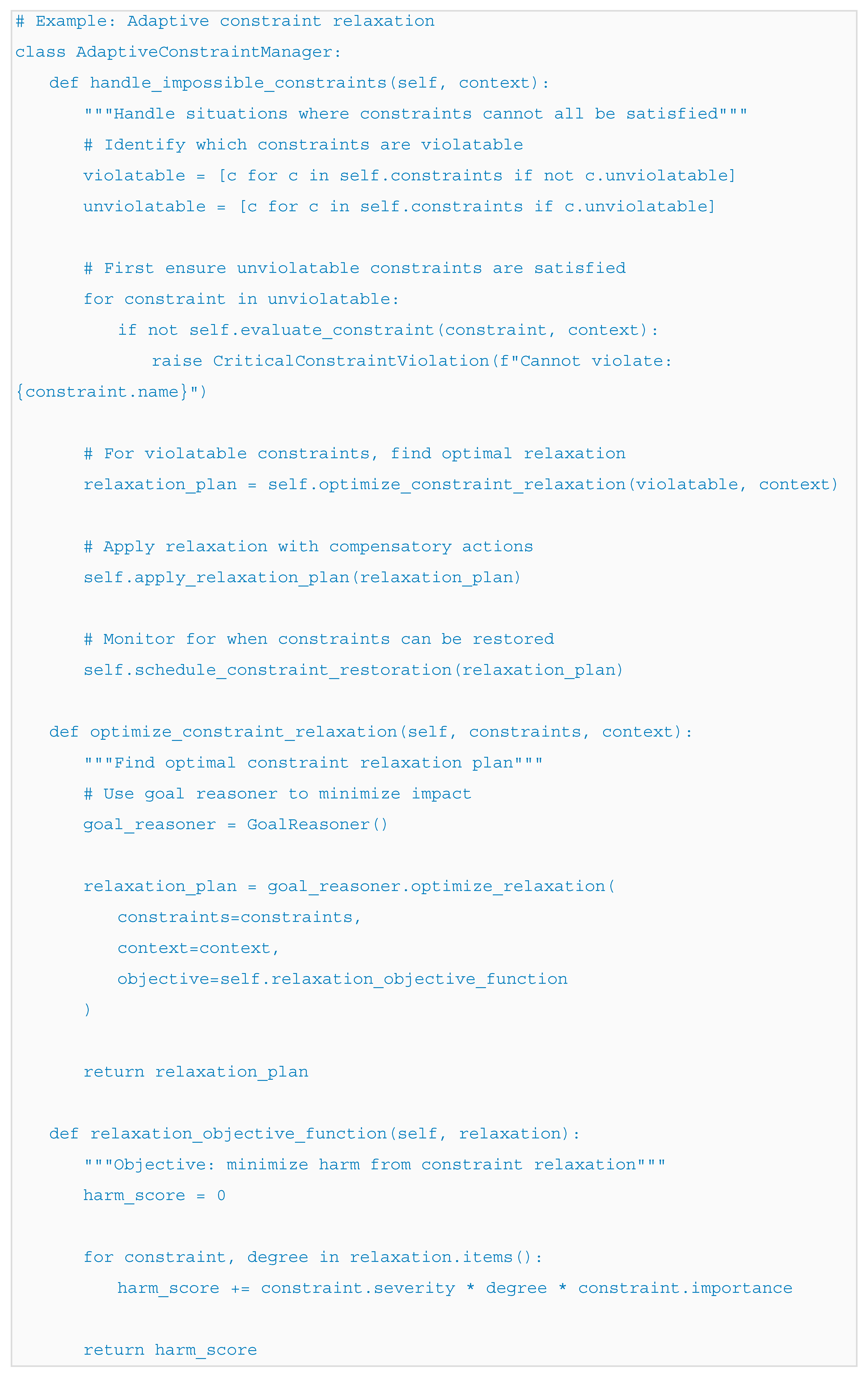

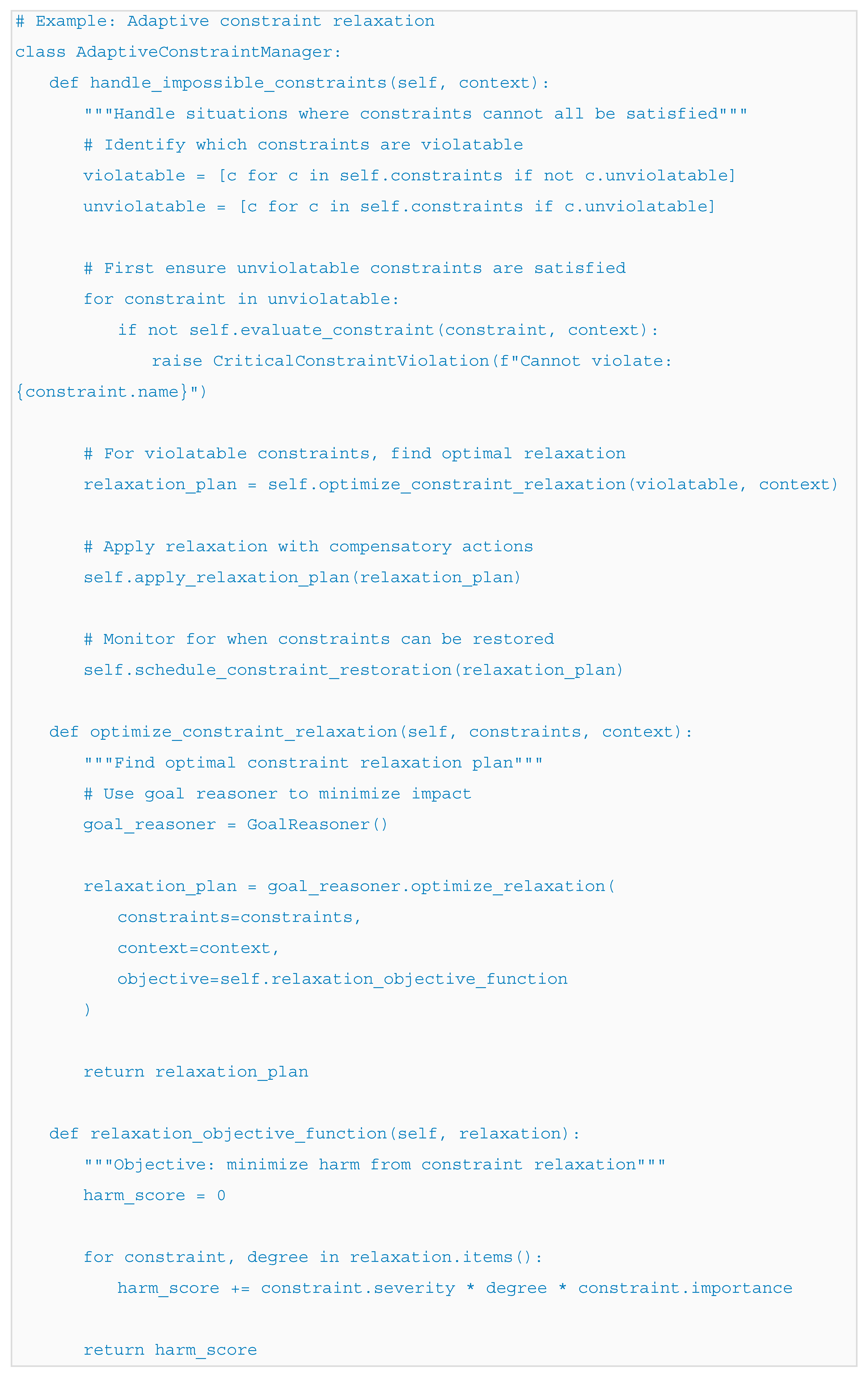

Adaptive Constraint Relaxation: In situations where strict constraint enforcement would cause failure, COH/GISMOL provides mechanisms for controlled constraint relaxation with compensatory measures, avoiding the brittle behavior typical of "jagged" systems.

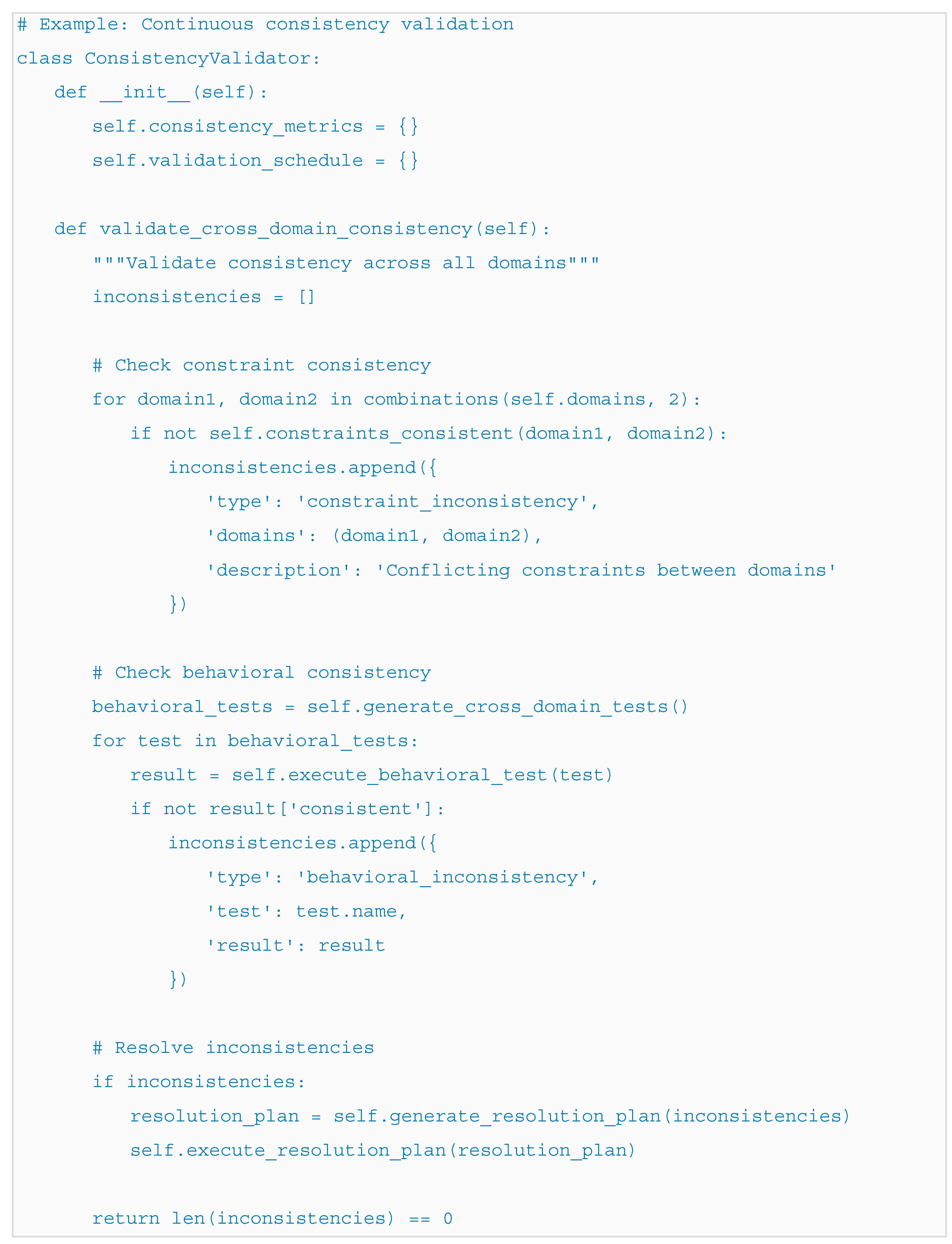

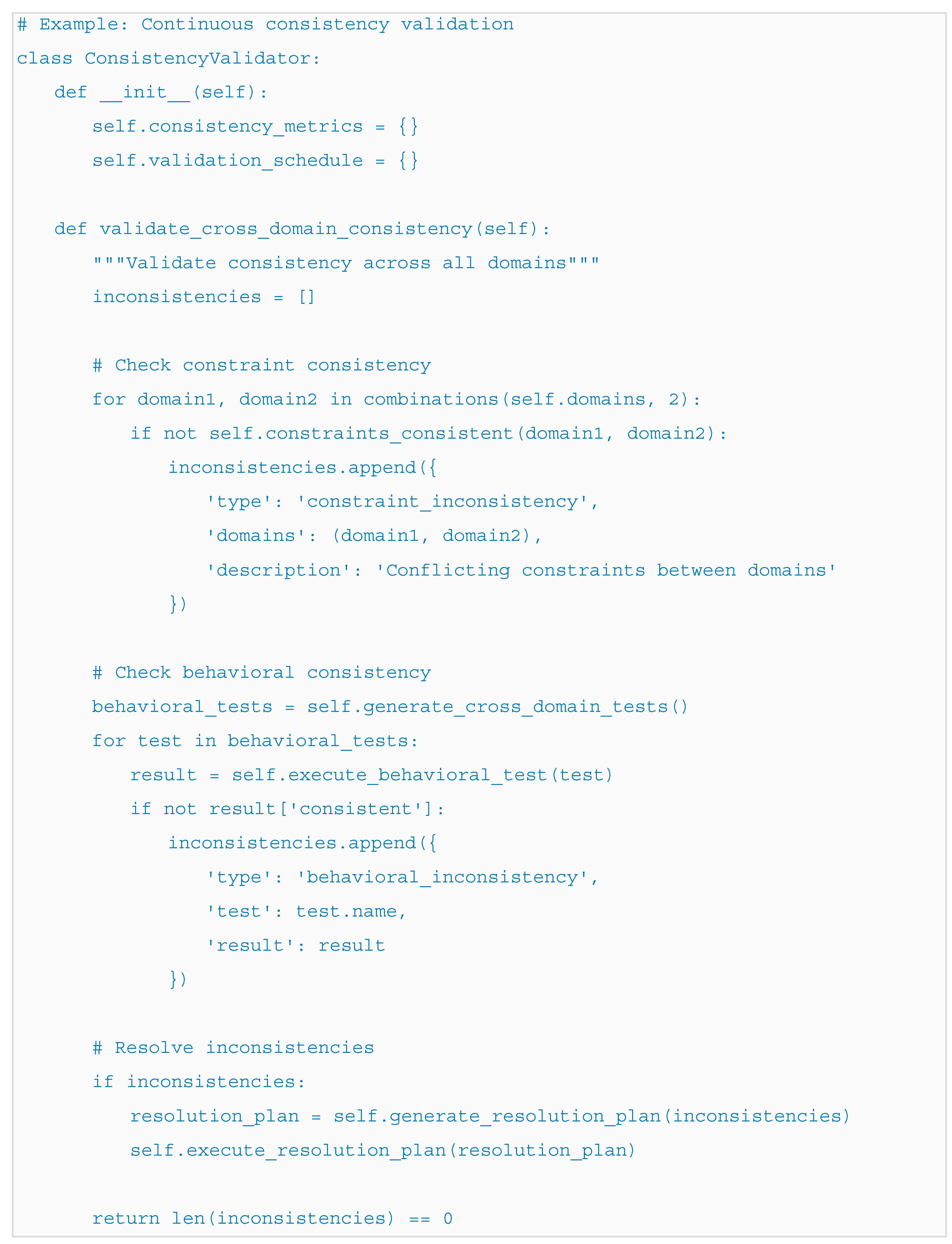

Continuous Consistency Validation: GISMOL includes mechanisms for continuously validating consistency across the system, detecting and correcting "jagged" behavior before it causes problems.

Through these mechanisms, COH/GISMOL ensures that intelligent systems exhibit consistent, reliable behavior across domains, avoiding the "jagged intelligence" problem that plagues many current AI approaches.

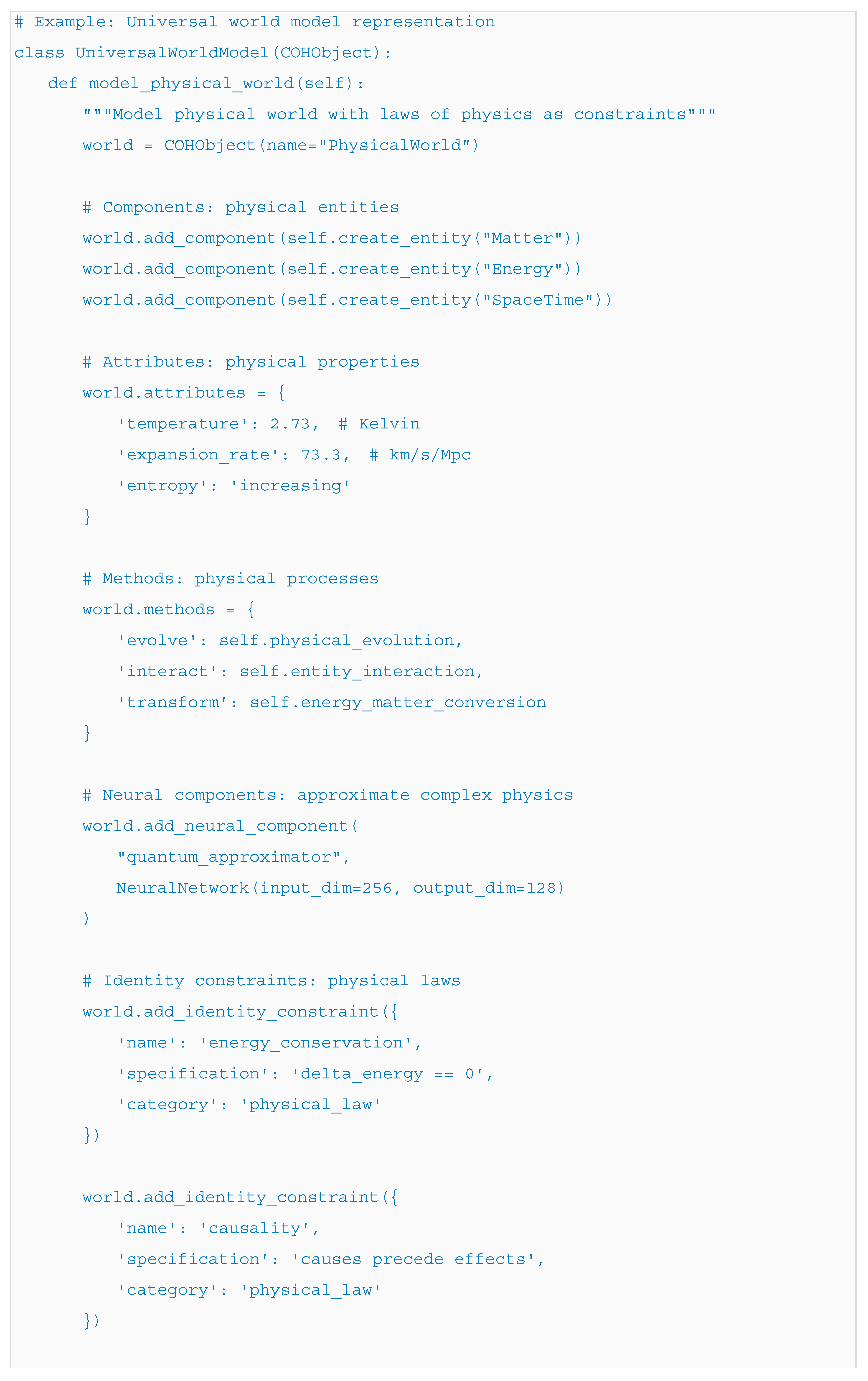

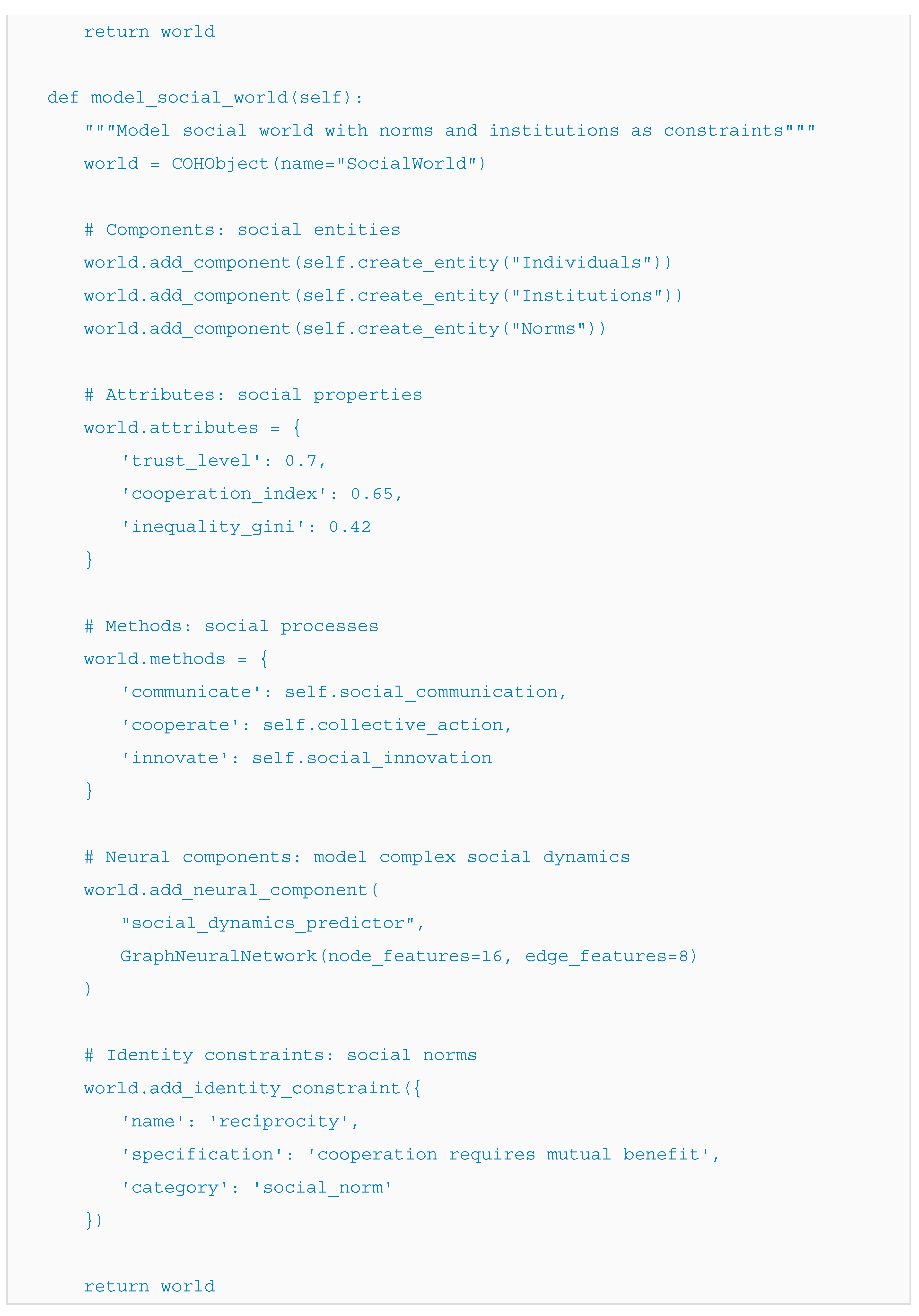

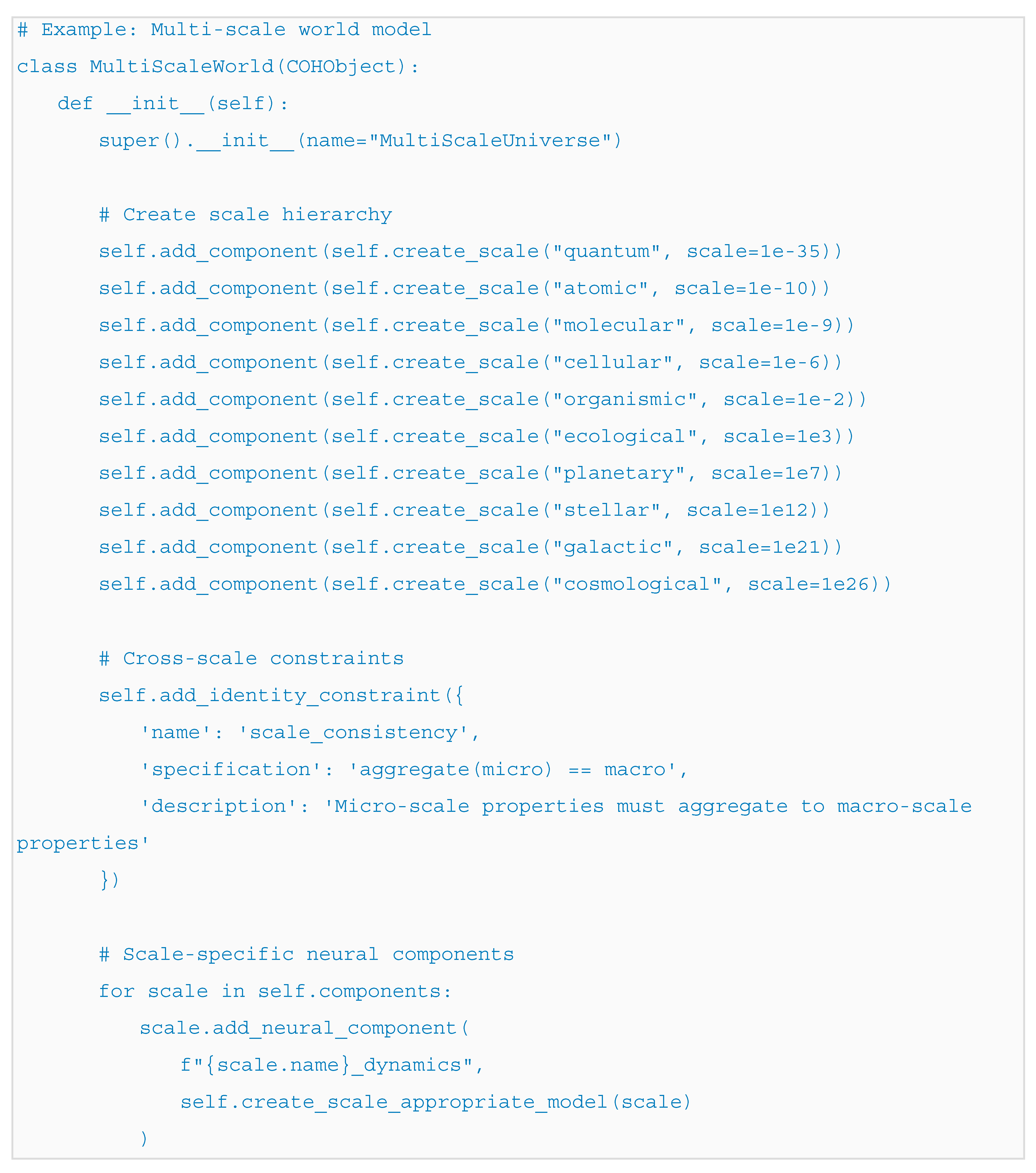

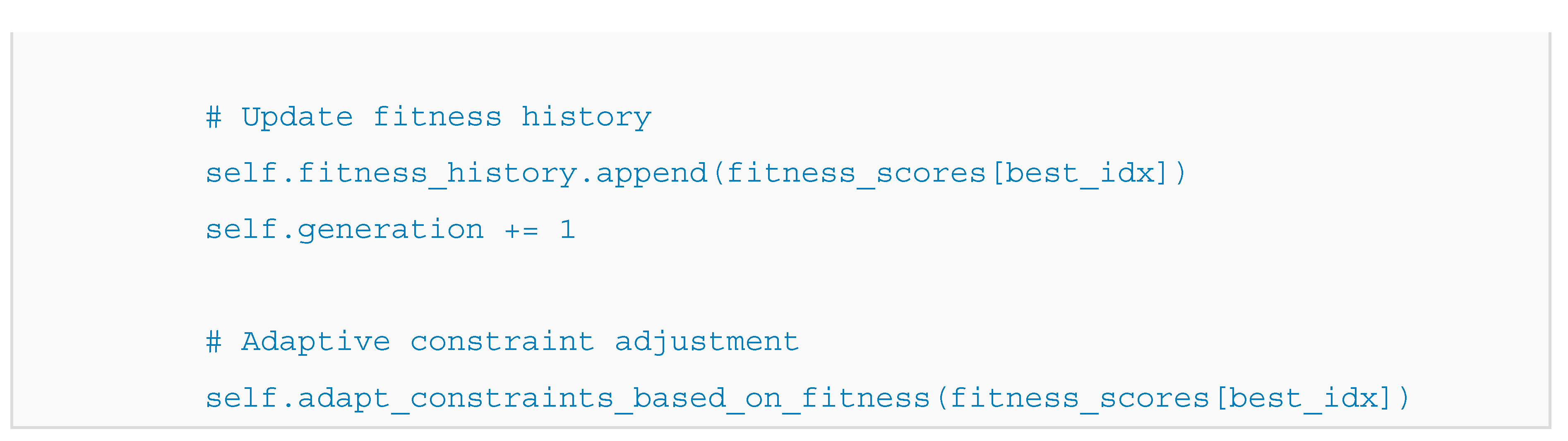

7. COH as a "Universal World Model"

The concept of a "universal world model" refers to a comprehensive representation that can capture the essential structure and dynamics of any environment or domain [

20]. COH provides such a capability through its flexible hierarchical representation and constraint formalism, enabling modeling of diverse worlds from physical environments to abstract conceptual spaces.

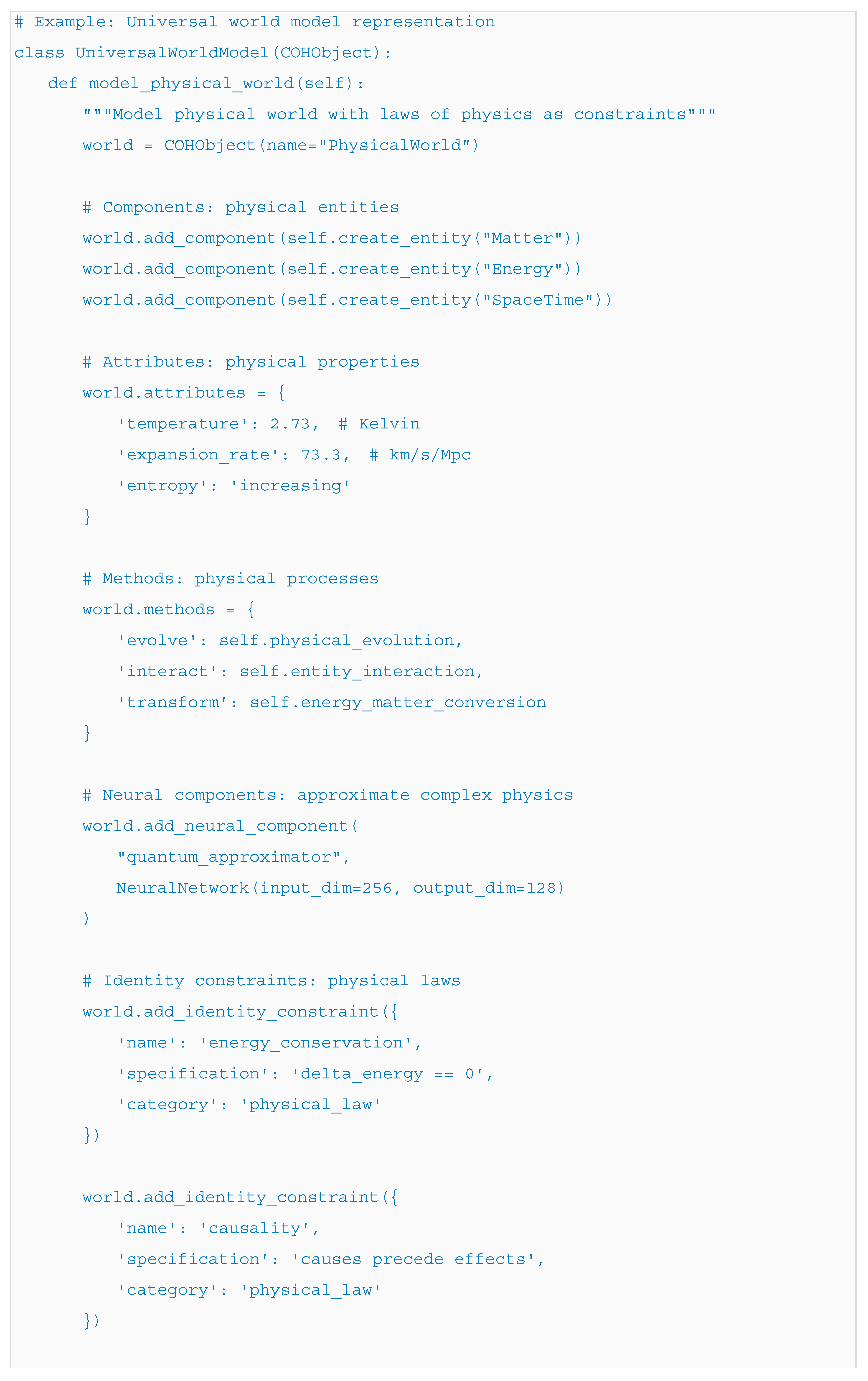

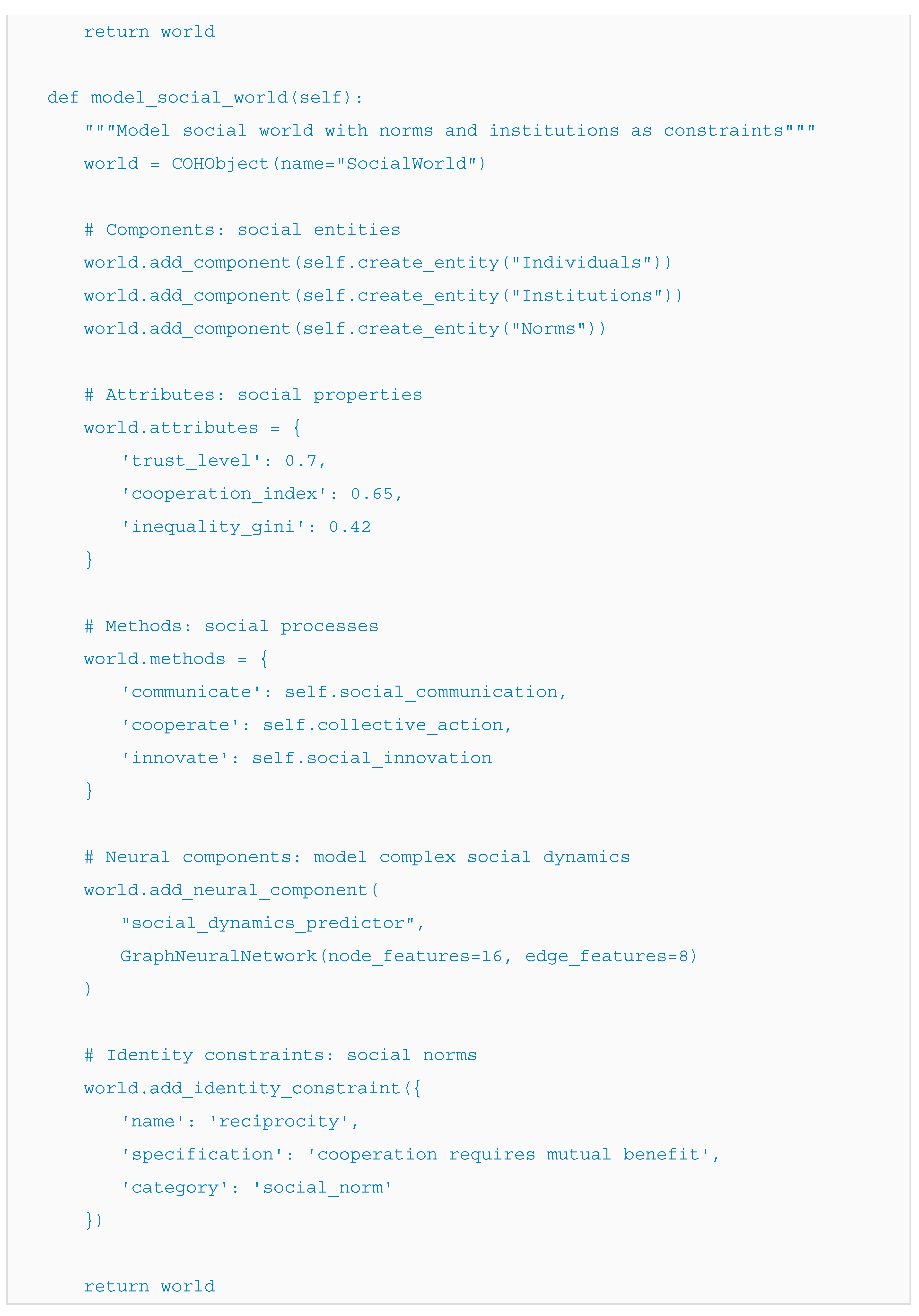

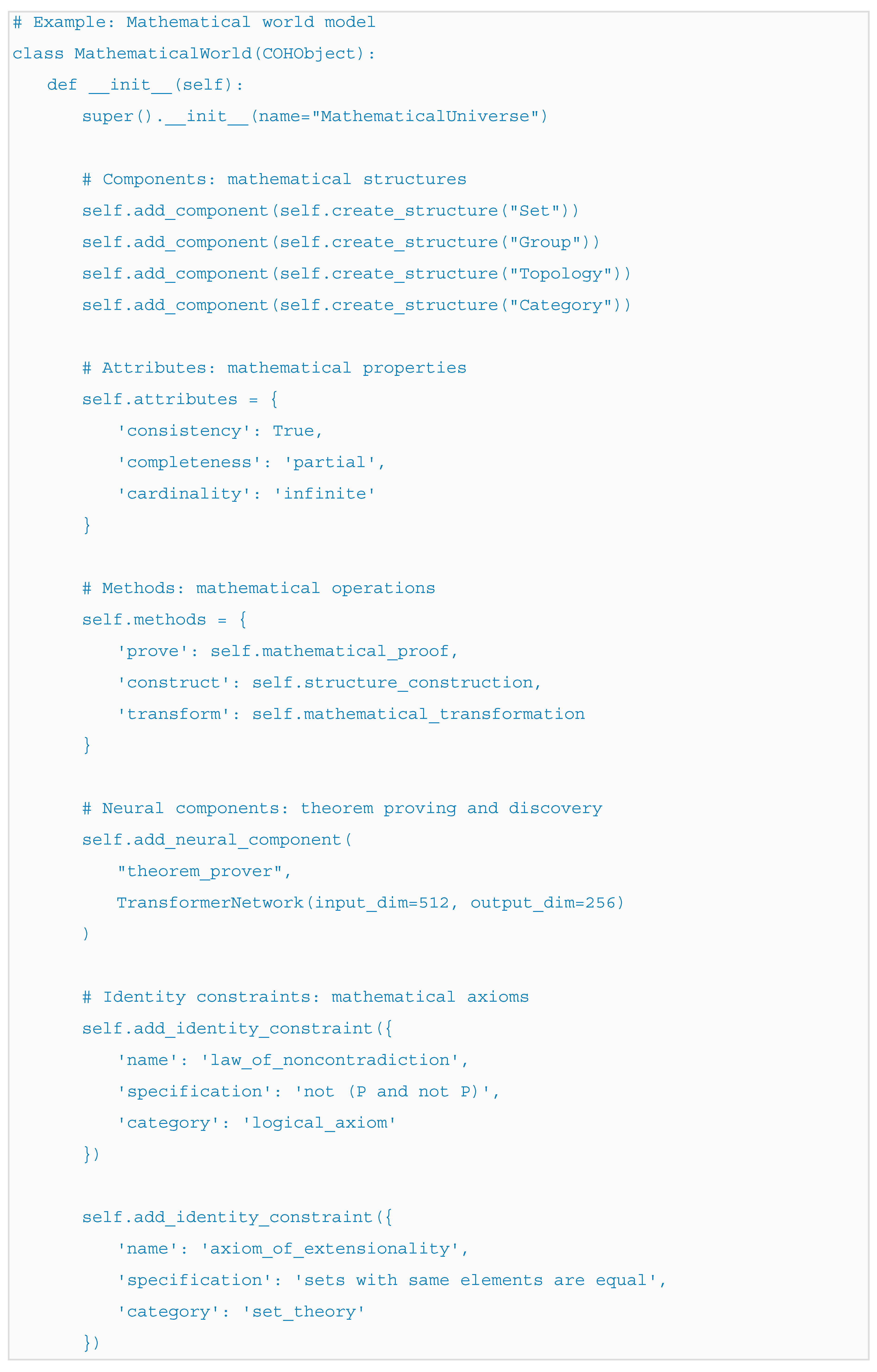

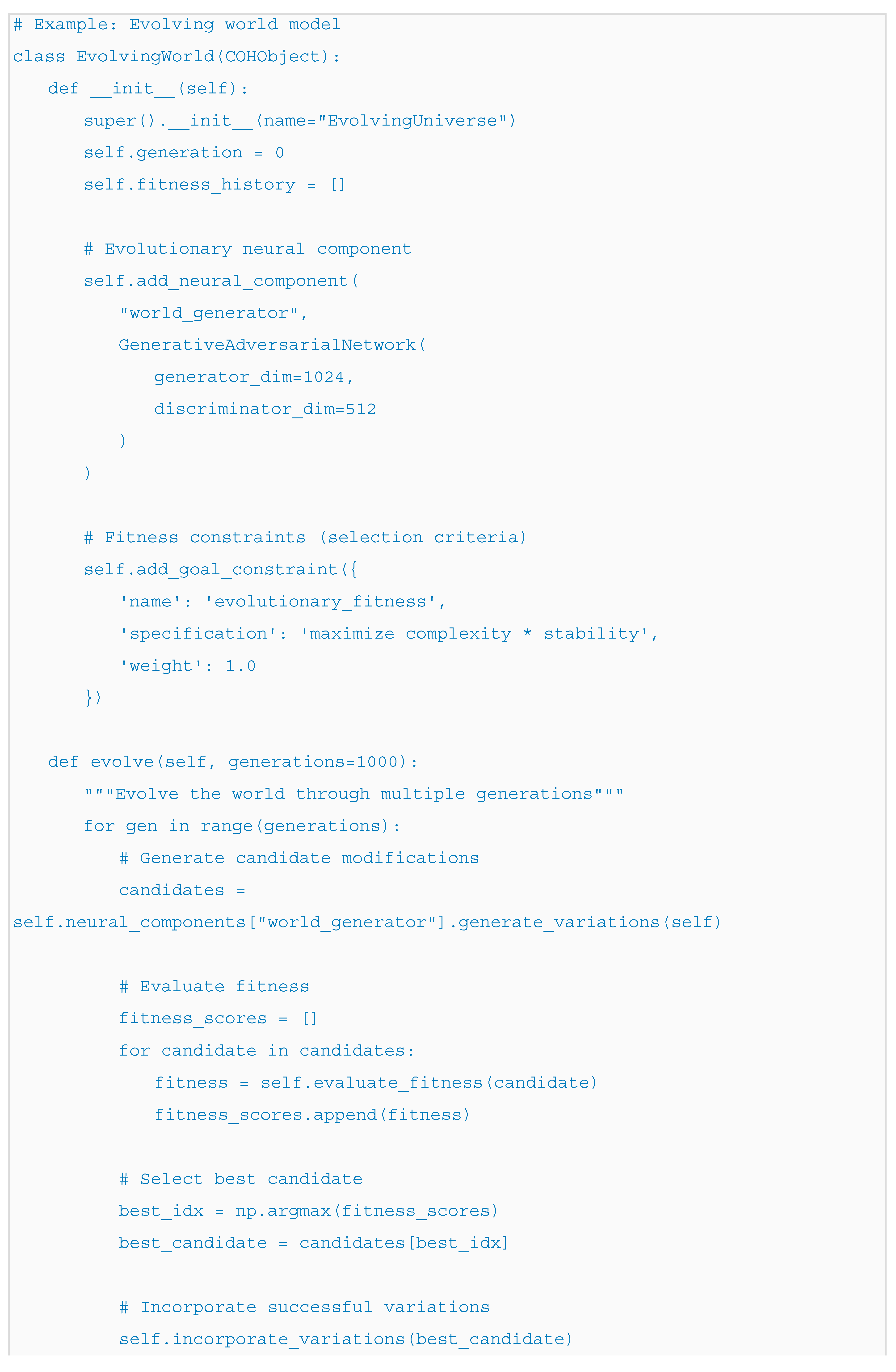

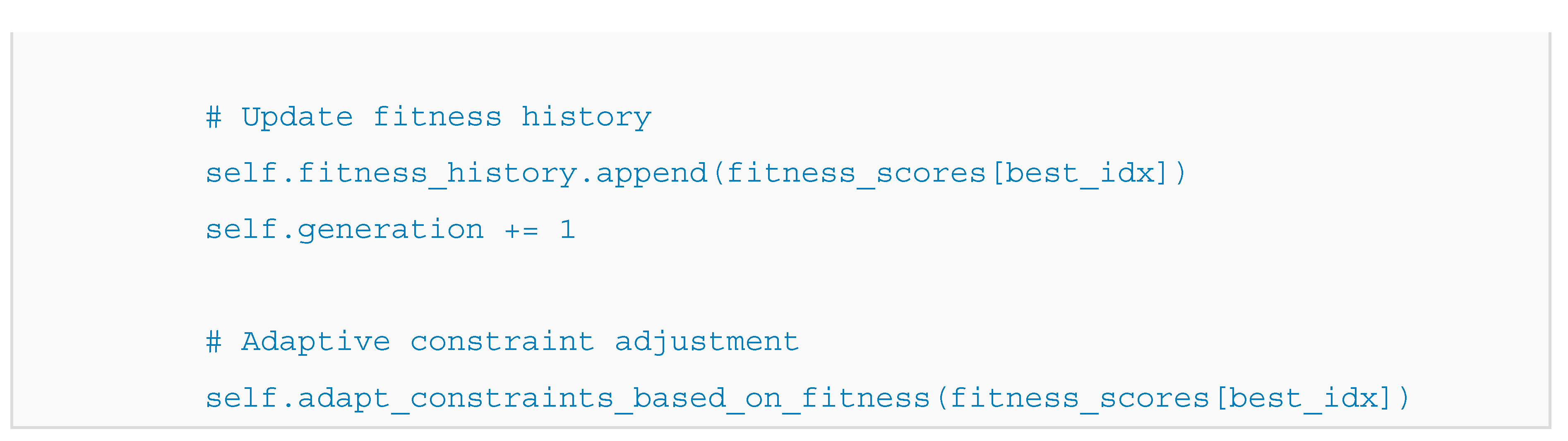

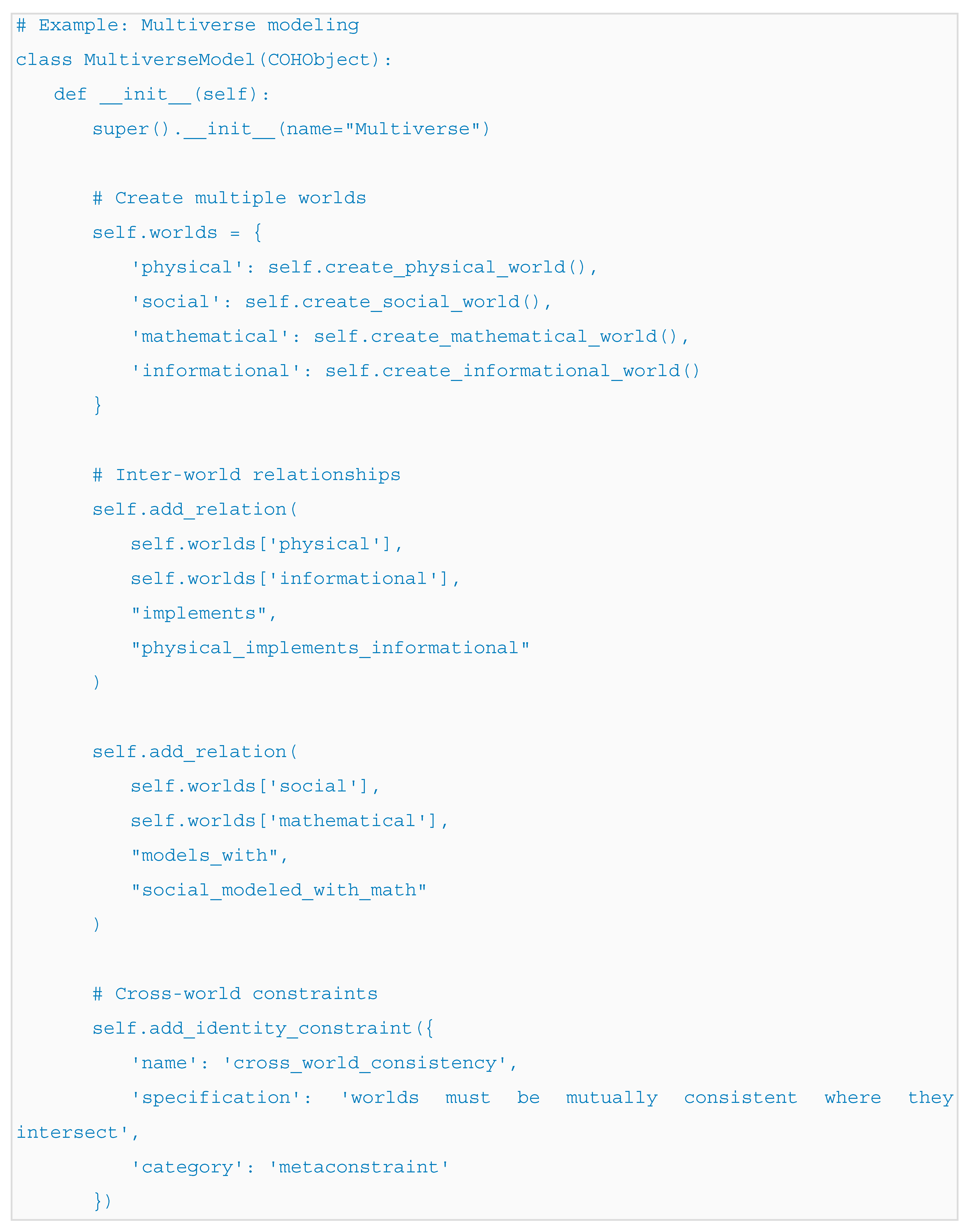

Formal Universality: The COH 9-tuple provides a formally complete representation that can encode any system with components, attributes, behaviors, adaptive elements, semantics, and constraints. This formal completeness enables COH to serve as a universal representation language.

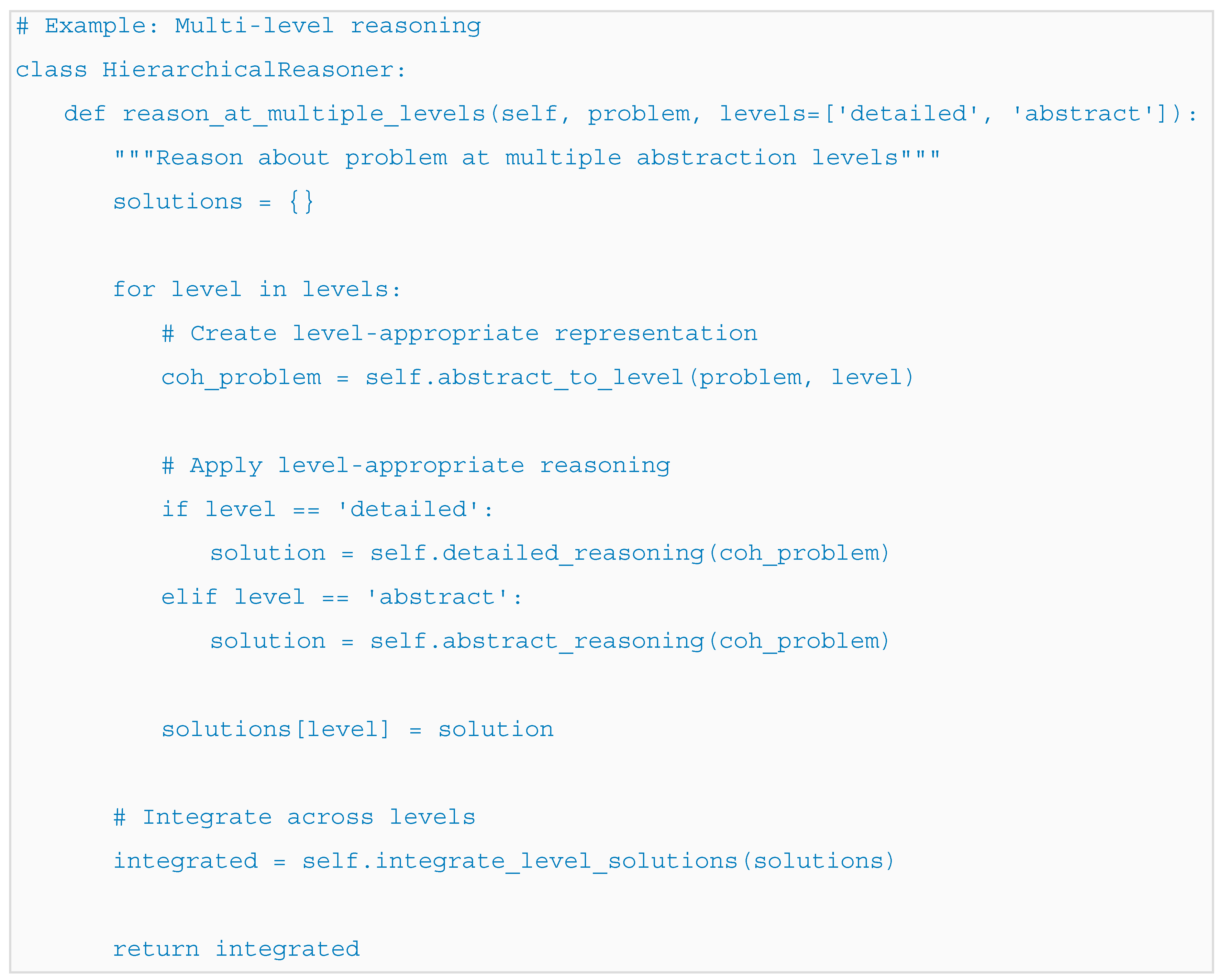

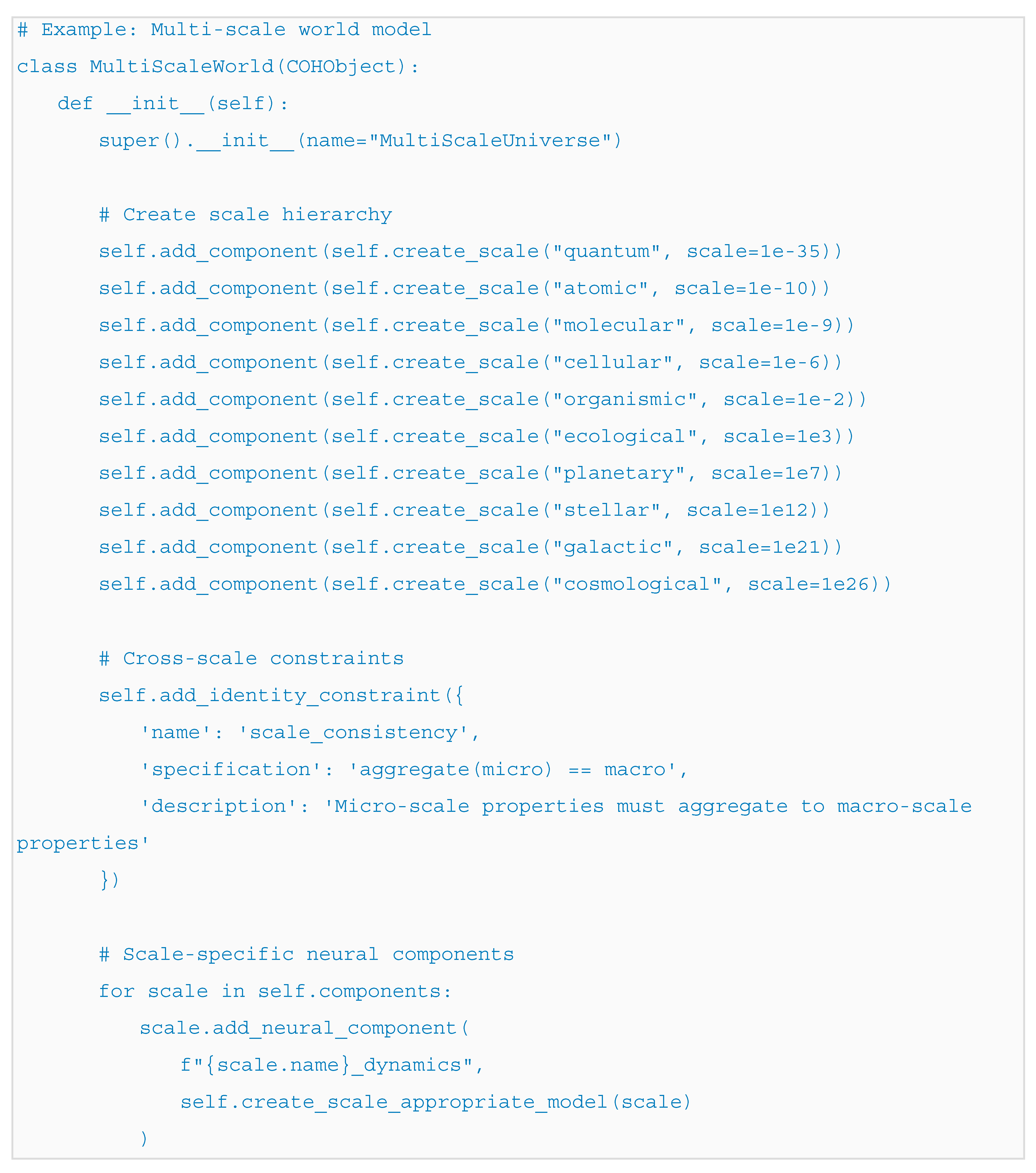

Multi-Scale Modeling: COH's hierarchical nature enables modeling at multiple scales simultaneously, from quantum phenomena to cosmological structures, all within a unified framework.

Abstract World Modeling: COH can model not only physical worlds but also abstract conceptual spaces, mathematical structures, and informational environments.

Dynamic World Adaptation: COH worlds can adapt and evolve over time through neural components and constraint modifications, modeling evolutionary processes and learning.

Inter-World Relationships: COH can model relationships between different worlds, enabling simulation of multiverse scenarios or parallel reality modeling.

Through these capabilities, COH serves as a true universal world model, capable of representing any conceivable environment or system while maintaining formal rigor and practical implementability.

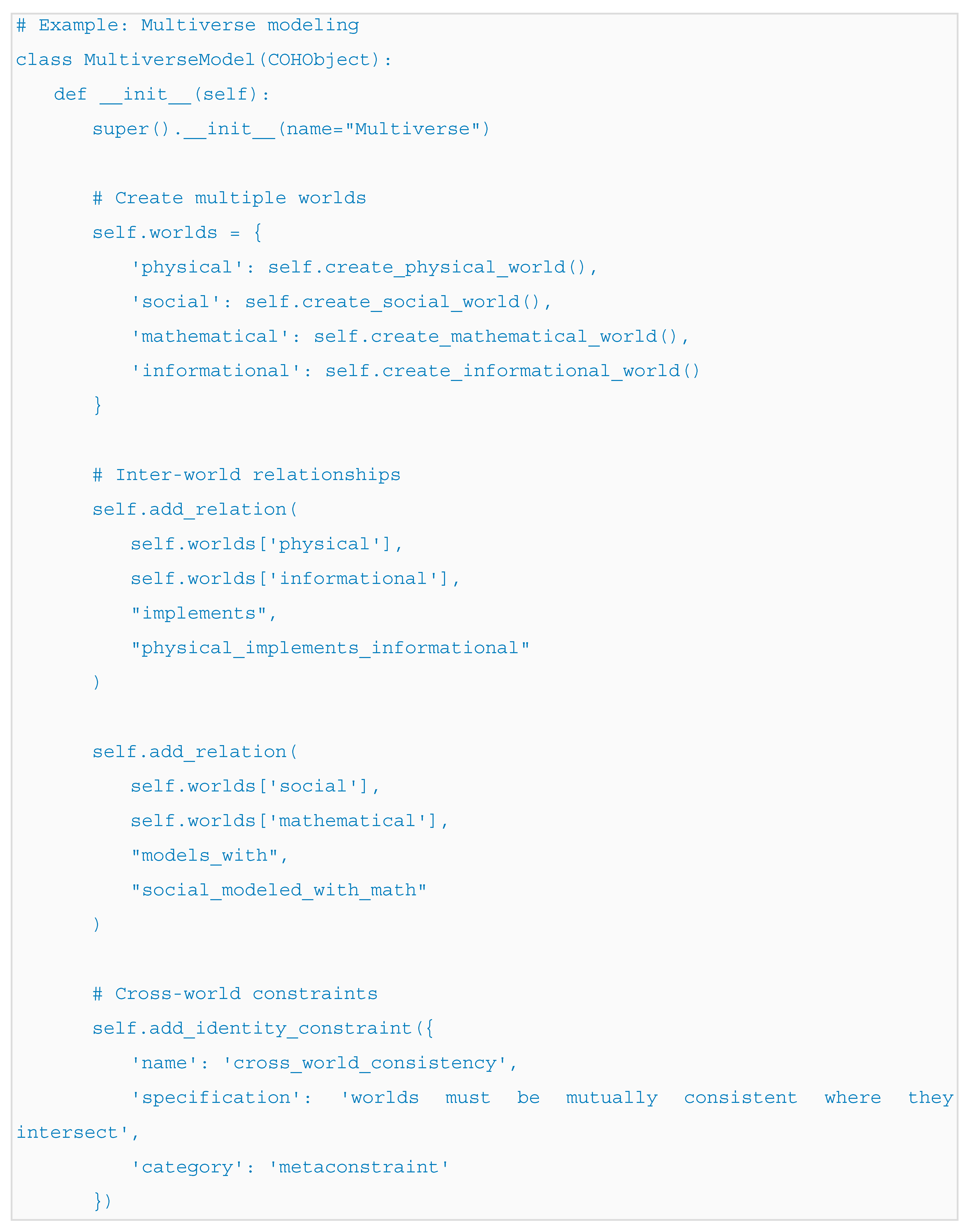

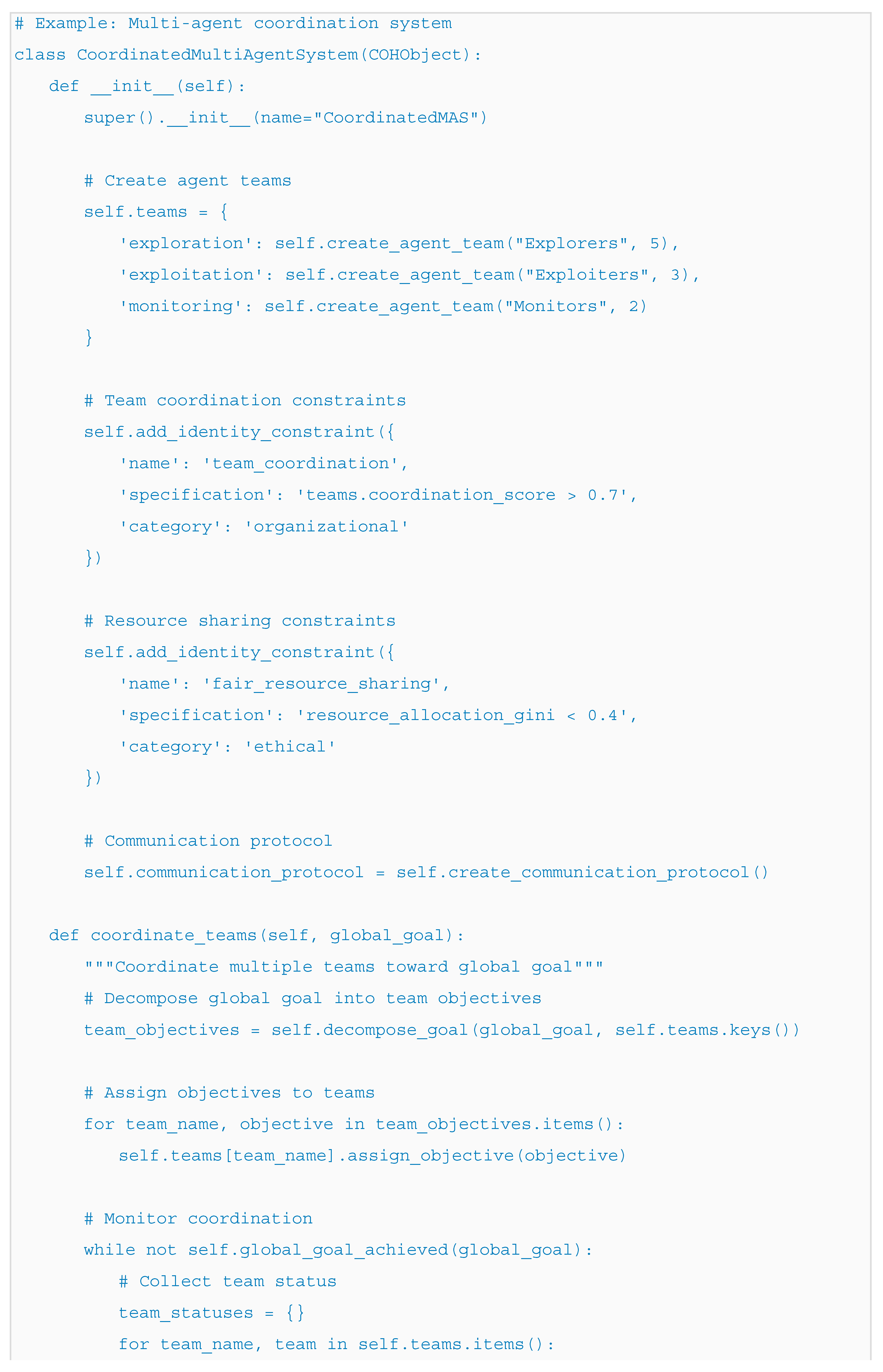

8. Modelling and Implementing "Agentic Systems"

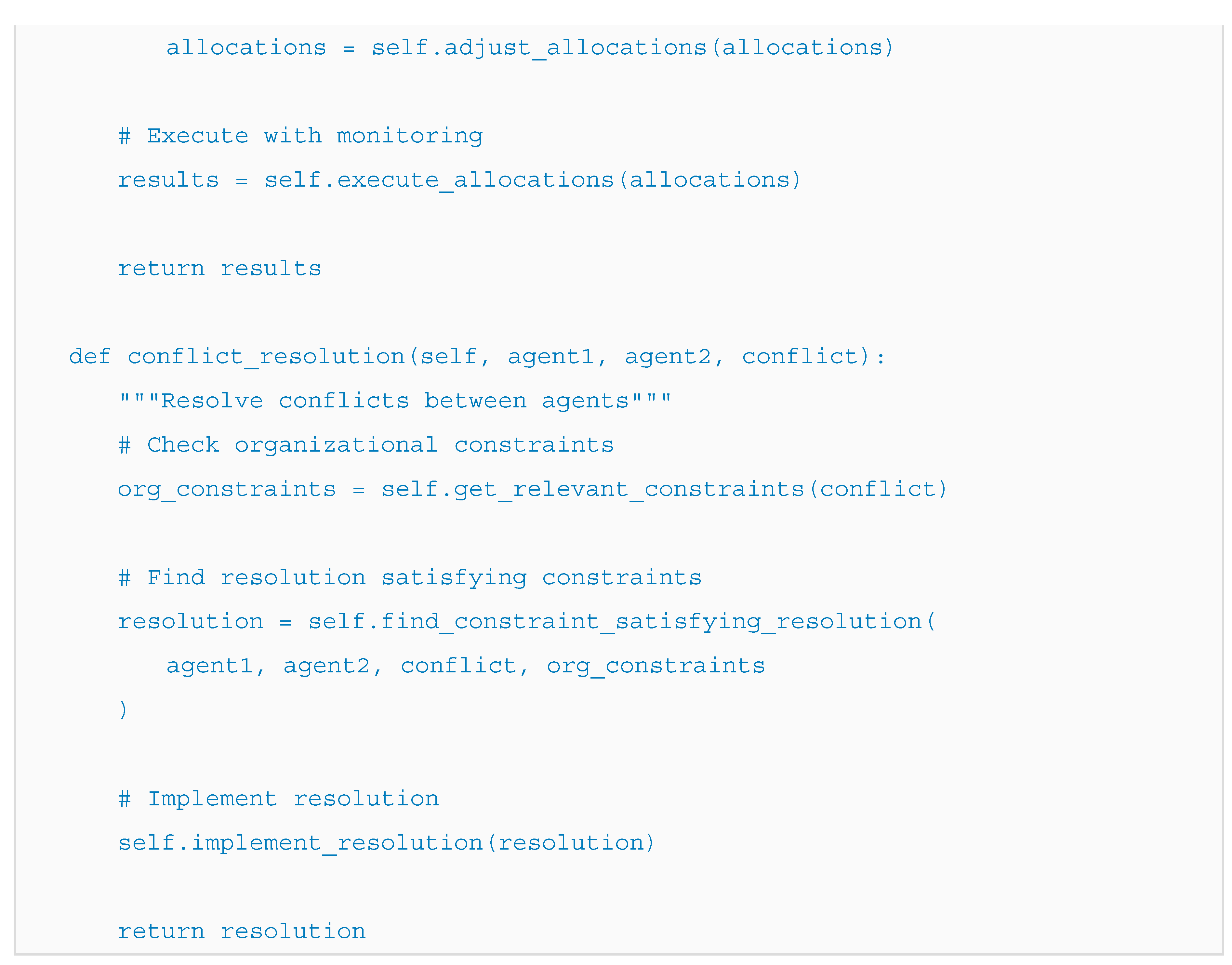

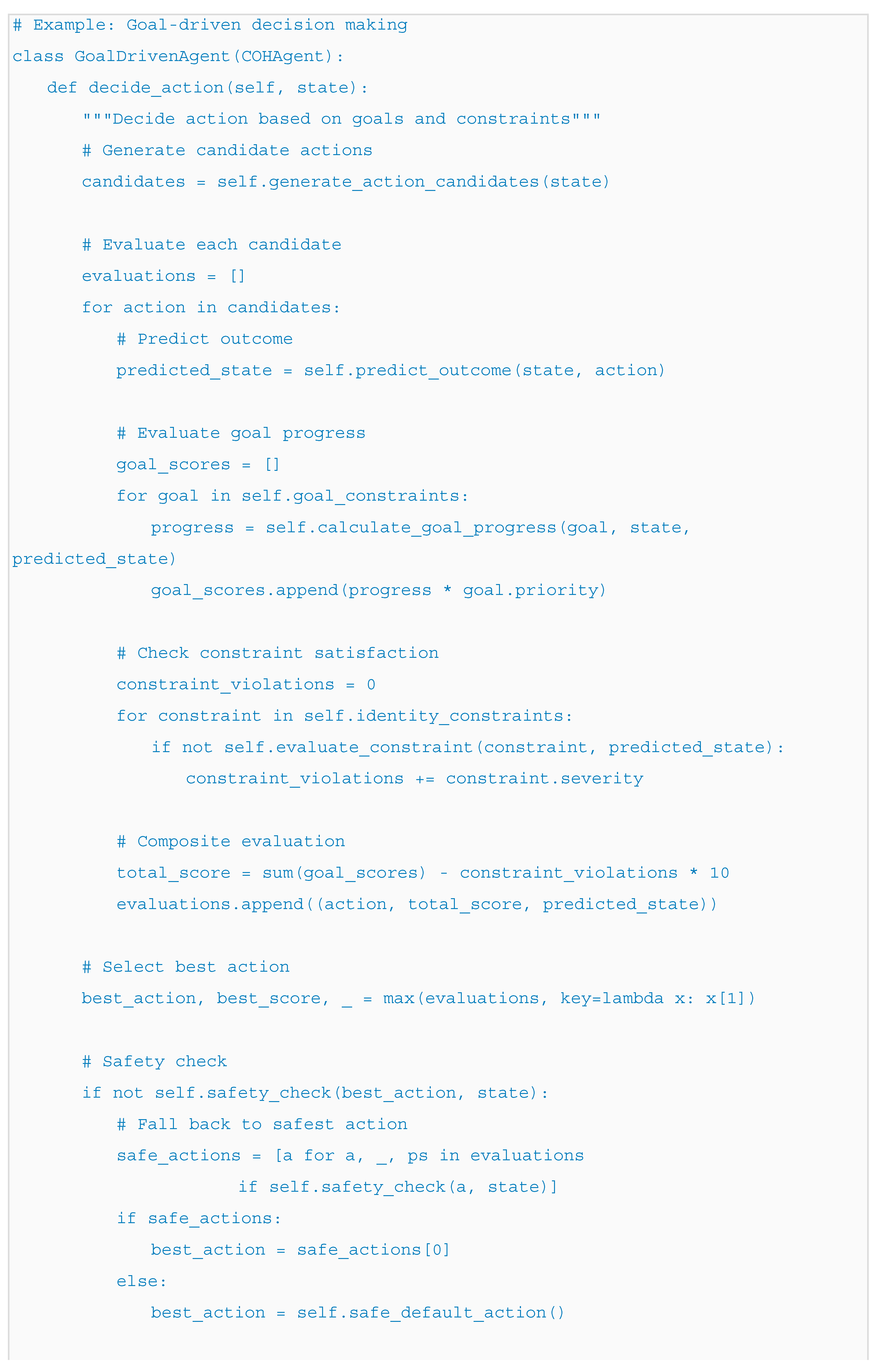

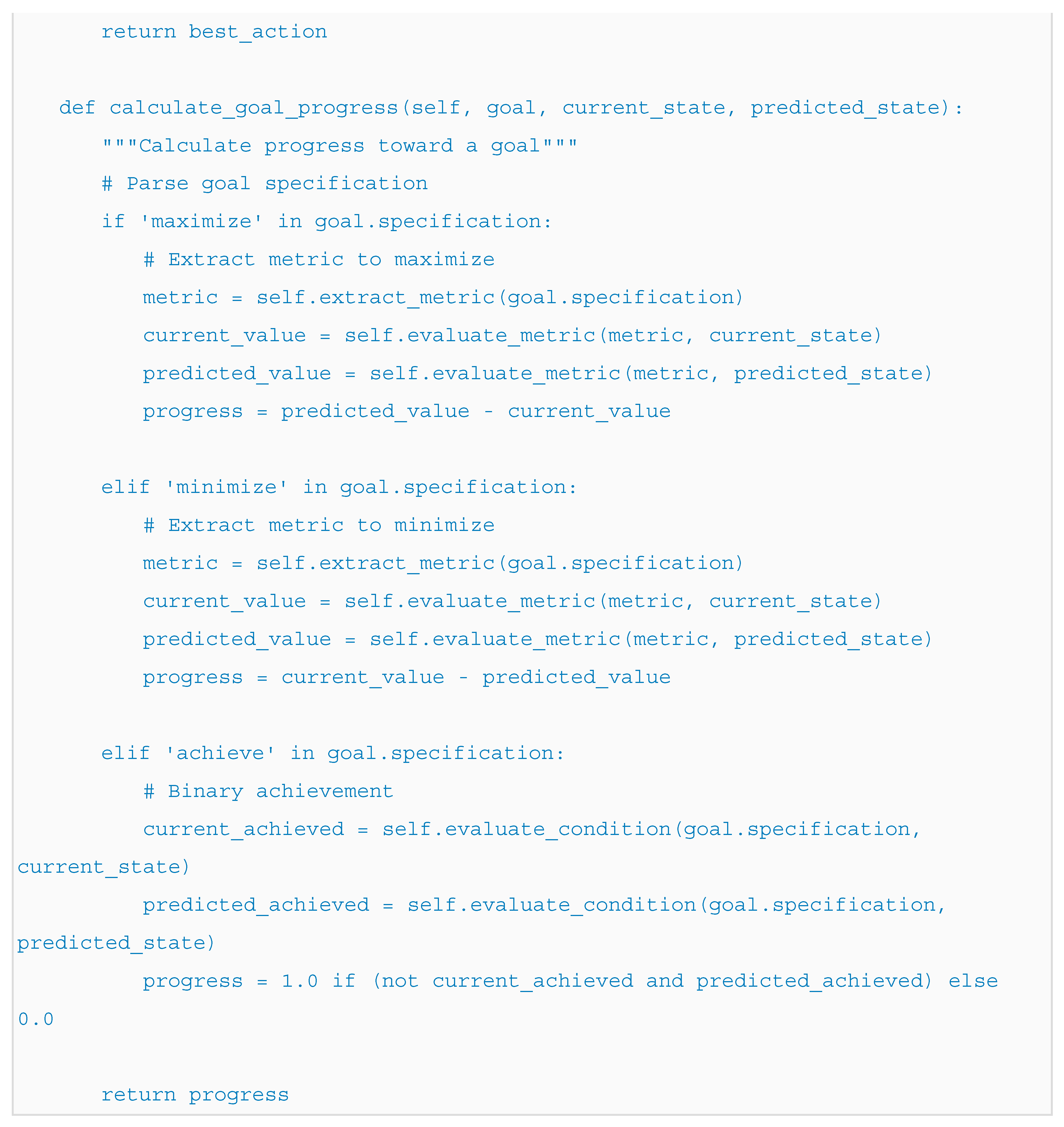

Agentic systems—autonomous entities that perceive, decide, and act in pursuit of goals—are a fundamental application of AGI. COH provides a natural framework for modeling agents with explicit goal constraints, adaptive behavior, and hierarchical decision-making. This section demonstrates how COH/GISMOL enables the development of sophisticated agentic systems.

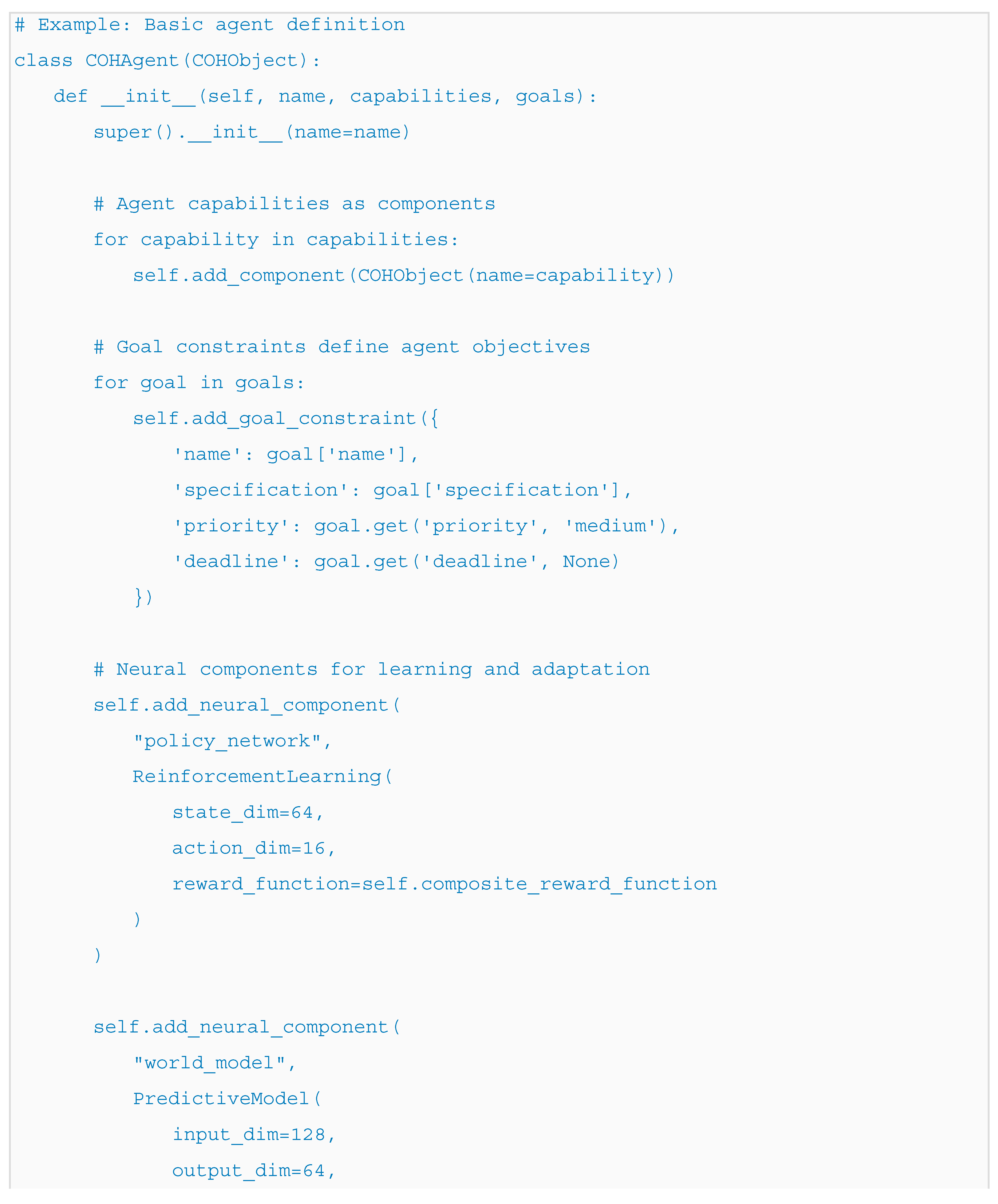

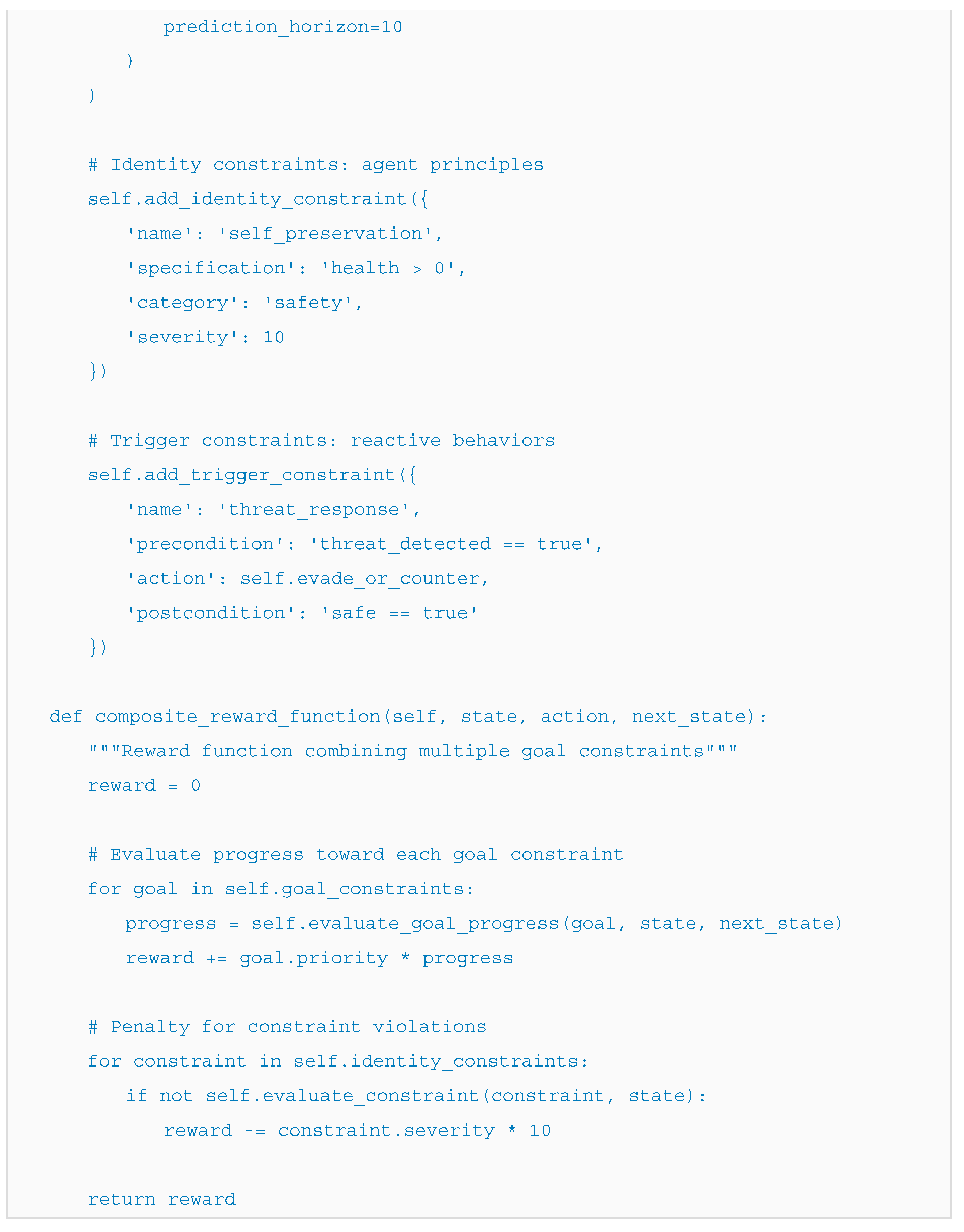

Agent as COHObject: In COH, agents are simply COHObjects with specific configurations: goal constraints define their objectives, neural components implement their adaptive capabilities, and trigger constraints govern their reactive behaviors.

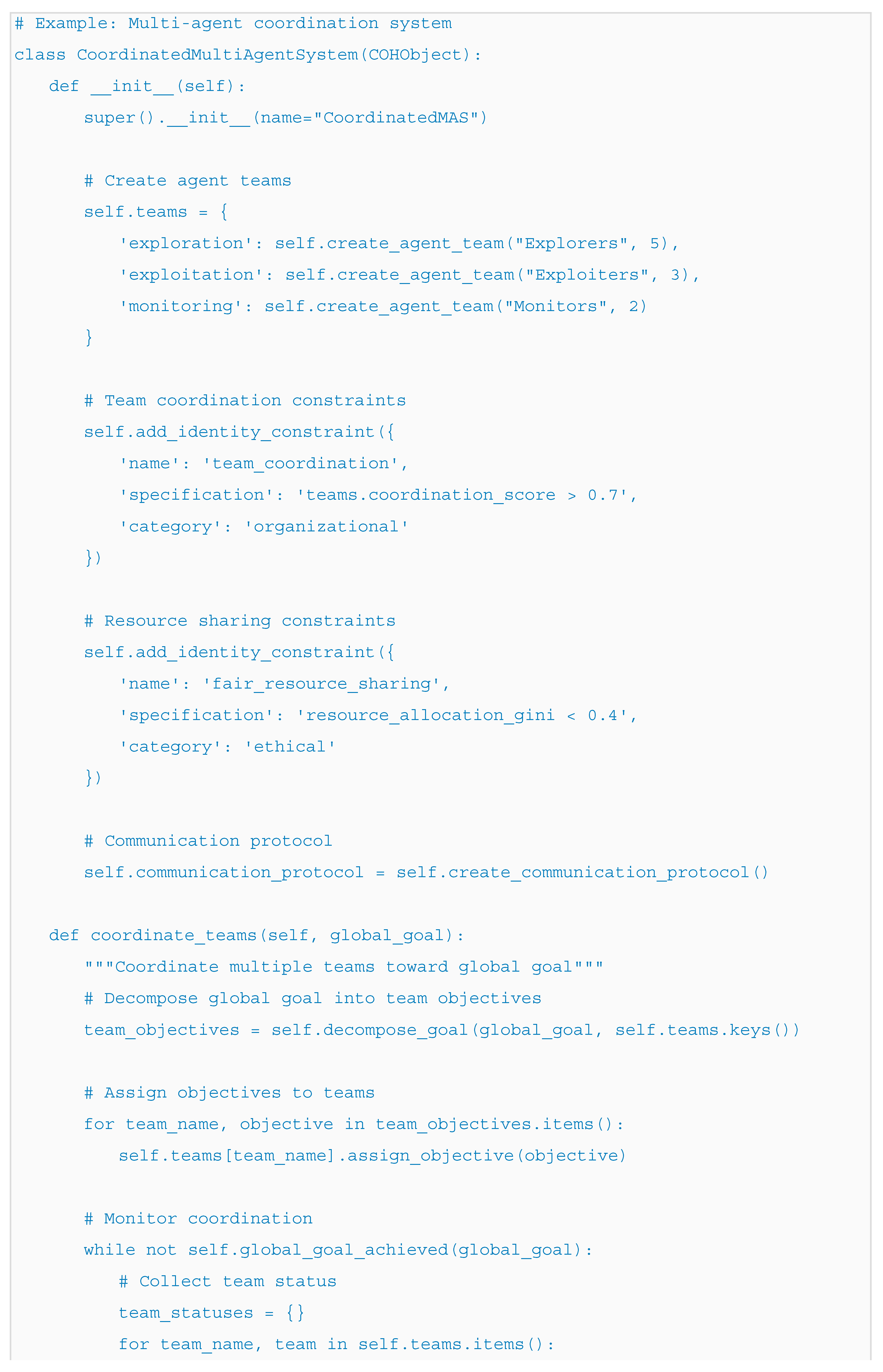

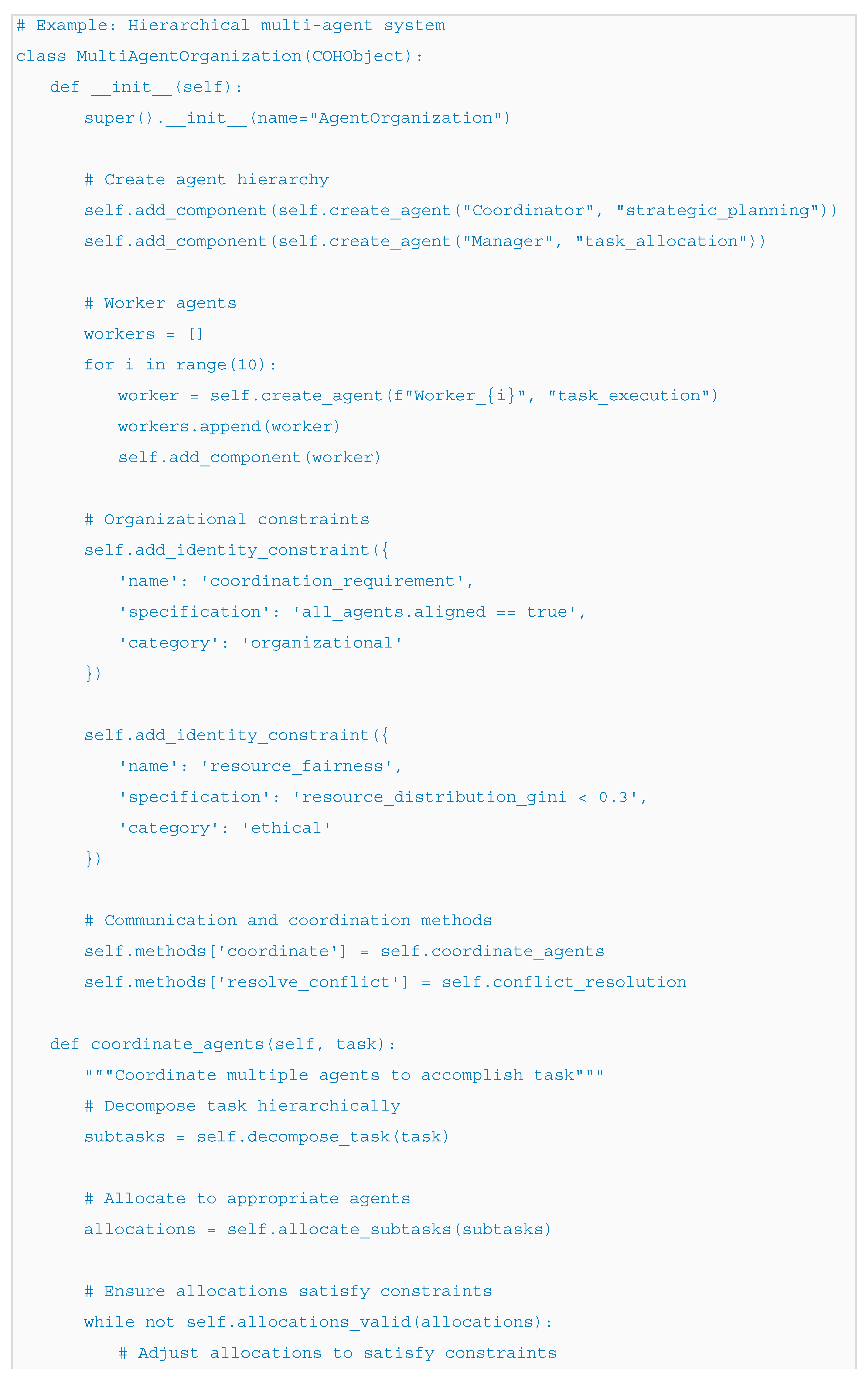

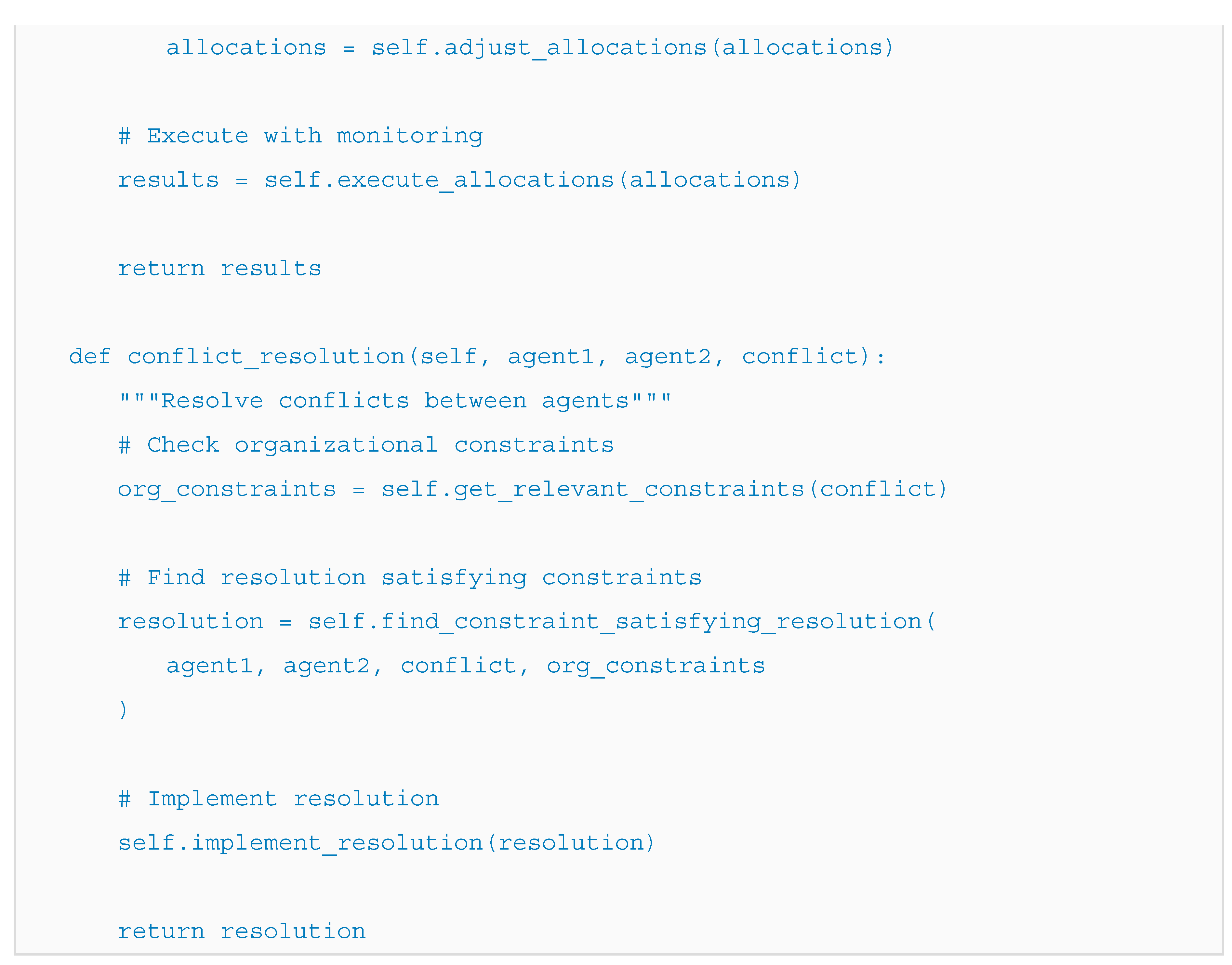

Hierarchical Agent Organizations: Complex agentic systems often involve hierarchies of agents with different roles and capabilities. COH naturally models such organizations through compositional hierarchies.

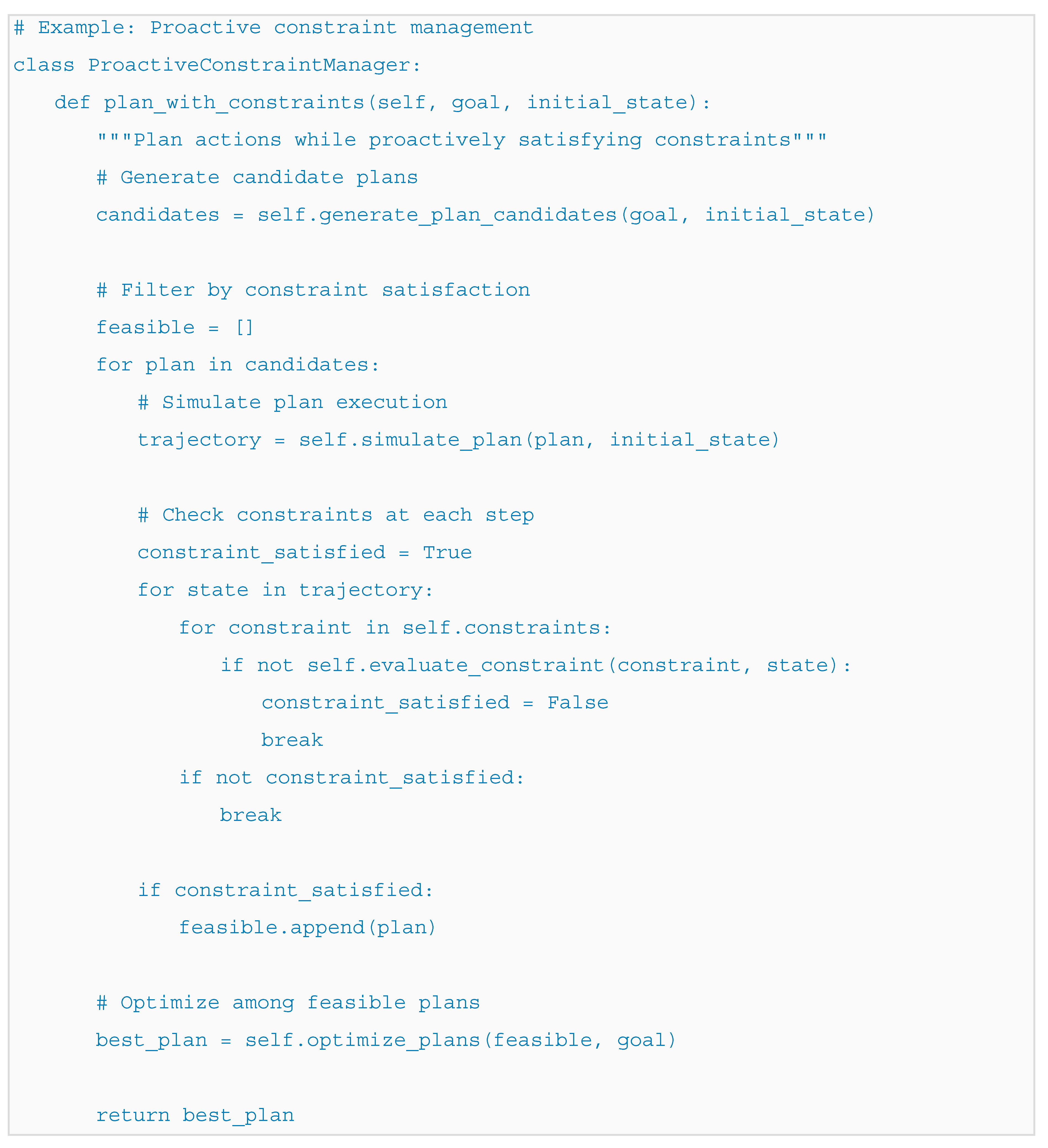

Goal-Driven Behavior: Goal constraints in COH agents drive their behavior through continuous optimization. Agents evaluate potential actions based on their contribution to goal achievement while respecting identity constraints.

Learning and Adaptation: Neural components in COH agents enable learning from experience while respecting constraints. The ConstraintAwareOptimizer ensures that learning doesn't violate important constraints.

Multi-Agent Coordination: COH enables modeling of complex multi-agent systems with explicit coordination constraints and communication protocols.

Through these mechanisms, COH/GISMOL enables the development of sophisticated agentic systems that are goal-driven, adaptive, coordinated, and constraint-aware—essential properties for AGI applications.

9. Why COH/GISMOL Can Be a Better Framework for AGI

The COH/GISMOL framework offers several advantages over existing approaches to AGI development, addressing key limitations in current AI systems while providing a path toward genuine general intelligence.

Unified Representation Across Domains: Unlike domain-specific AI systems or narrowly trained models, COH provides a universal representation that applies equally to all domains. This enables knowledge transfer, consistent reasoning, and true generalization—hallmarks of general intelligence.

Explicit Constraint Management: Most AI systems handle constraints implicitly or through post-hoc correction. COH makes constraints first-class citizens, enabling proactive constraint satisfaction, violation prevention, and principled constraint relaxation when necessary.

Hierarchical Abstraction and Composition: The compositional hierarchy in COH enables modeling at multiple abstraction levels simultaneously, from low-level details to high-level concepts. This mirrors the hierarchical organization of intelligence in biological systems and enables scalable reasoning.

Neural-Symbolic Integration: COH seamlessly integrates neural components (sub-symbolic, pattern-based reasoning) with symbolic constraints and structures. This combines the learning capabilities of neural networks with the precision and explainability of symbolic reasoning.

Explainability and Transparency: The explicit constraint structure in COH enables detailed explanation of system behavior. When a decision is made or a constraint is violated, the system can provide clear explanations based on its constraint hierarchy.

Safety and Robustness: The constraint daemon system in COH provides continuous monitoring and enforcement of safety constraints. This is particularly important for AGI systems that must operate reliably in complex, unpredictable environments.

Scalability and Compositionality: The hierarchical nature of COH enables systems to scale from simple agents to complex organizations while maintaining consistent constraint management. New components can be added without disrupting existing functionality.

These advantages make COH/GISMOL a superior framework for AGI development, addressing fundamental challenges that have hindered progress in the field while providing a practical path toward building truly general intelligent systems.

10. Key Contributions

This paper makes several significant contributions to the field of artificial general intelligence:

Formalization of Constrained Object Hierarchies: We have presented a complete formalization of COH as a 9-tuple framework that integrates hierarchical composition, neural adaptation, and multi-type constraints into a unified representation for intelligent systems.

Implementation of GISMOL: We have developed GISMOL as a practical Python implementation of the COH framework, providing developers with tools for building constraint-aware intelligent systems across domains.

Multi-Domain Case Studies: Through six comprehensive case studies across healthcare, manufacturing, social science, finance, biology, and astronomy, we have demonstrated COH's ability to model complex adaptive systems with explicit constraint management.

Solution to "Jagged Intelligence": We have shown how COH/GISMOL addresses the "jagged intelligence" problem through unified representation, consistent constraint enforcement, and cross-domain knowledge transfer.

Universal World Modeling Framework: We have demonstrated that COH can serve as a universal world model, capable of representing any environment or system while maintaining formal rigor.

Agentic System Development Methodology: We have provided a comprehensive approach to developing agentic systems within the COH framework, with explicit goal constraints, adaptive behavior, and hierarchical coordination.

Constraint-Aware Neural Integration: We have developed techniques for integrating neural components with constraint systems, enabling learning and adaptation while respecting domain constraints.

Practical Implementation Guidelines: We have provided detailed implementation examples showing how COH models translate to executable GISMOL systems, bridging the gap between theory and practice.

These contributions advance both the theory and practice of AGI development, providing a comprehensive framework for building intelligent systems that are capable, reliable, and safe across diverse domains.

11. Conclusion and Future Research

The Constrained Object Hierarchies framework, implemented through the GISMOL toolkit, represents a significant advance in the pursuit of artificial general intelligence. By providing a unified representation that integrates hierarchical composition, neural adaptation, and explicit constraint management, COH addresses fundamental challenges in AGI development while offering practical tools for implementation.

Our case studies demonstrate COH's versatility across domains, from pandemic response to interstellar exploration. The framework's ability to model complex adaptive systems with verifiable constraint satisfaction makes it particularly suitable for safety-critical applications where reliability is paramount. The integration of neural components enables learning and adaptation while maintaining constraint boundaries, addressing the tension between flexibility and safety that has hindered many AI approaches.

Several directions for future research emerge from this work:

Scalability Optimization: While COH provides a principled approach to hierarchical modeling, practical deployment in extremely large-scale systems requires optimization of constraint propagation and evaluation algorithms.

Automatic Constraint Learning: Current implementations require manual specification of constraints. Future work could develop techniques for learning constraints from data or experience while maintaining safety guarantees.

Cross-Domain Generalization: Further research is needed on mechanisms for automatic knowledge transfer between domains, enabling faster adaptation to new environments.

Human-COH Collaboration: Developing intuitive interfaces for humans to interact with COH systems, specify constraints, and understand system reasoning will be crucial for real-world deployment.

Formal Verification: Extending formal verification techniques to COH systems could provide mathematical guarantees of constraint satisfaction under specified conditions.

Neuroscientific Validation: Further research could investigate the correspondence between COH structures and neural organization in biological intelligent systems, potentially leading to more brain-inspired architectures.

Distributed COH Systems: Developing techniques for distributed implementation of COH systems could enable larger-scale deployments while maintaining constraint consistency.

The COH/GISMOL framework provides a solid foundation for these research directions while offering immediate practical value for developing intelligent systems across diverse domains. As AI systems become increasingly integrated into critical infrastructure and everyday life, frameworks that prioritize constraint management, explainability, and safety will become increasingly important. COH represents a significant step toward AGI systems that are not only intelligent but also reliable, transparent, and aligned with human values.

References

- Hendrycks et al., “Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding,” International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2021.

- J. Friston, “The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 127–138, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. McCarthy, "Programs with common sense," in Proceedings of the Teddington Conference on the Mechanization of Thought Processes, London, UK, 1959, pp. 75-91.

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, "Deep learning," Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436-444, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. S. d'Avila Garcez, L. C. Lamb, and D. M. Gabbay, Neural-Symbolic Cognitive Reasoning. Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2009.

- 6. J. E. Laird, The Soar Cognitive Architecture. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2012. J. E. Laird, The Soar Cognitive Architecture 2012.

- D. Ha and J. Schmidhuber, "World models," arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.10122, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Miller, "The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information," Psychological Review, vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 81-97, 1956. [CrossRef]

- J. Hawkins and S. Blakeslee, On Intelligence. New York, NY, USA: Times Books, 2004.

- E. Tsang, Foundations of Constraint Satisfaction. London, UK: Academic Press, 1993.

- K. Marriott and P. J. Stuckey, Programming with Constraints: An Introduction. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1998.

- D. J. Felleman and D. C. Van Essen, "Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex," Cerebral Cortex, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-47, 1991. [CrossRef]

- G. M. Edelman, Neural Darwinism: The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. New York, NY, USA: Basic Books, 1987.

- J. E. Laird, A. Newell, and P. S. Rosenbloom, "Soar: An architecture for general intelligence," Artificial Intelligence, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 1-64, 1987. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Anderson, The Adaptive Character of Thought. Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1990.

- T. Brown et al., "Language models are few-shot learners," in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 2020, pp. 1877-1901.

- G. Marcus, “Deep learning: A critical appraisal,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.00631, 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. G. Leveson, Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2011.

- W. Battaglia et al., “Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.01261, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Hamrick et al., "On the role of planning in model-based deep reinforcement learning," arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.04021, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Russell and P. Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Pearson, 2020.

- W. O. Kermack and A. G. McKendrick, "A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, vol. 115, no. 772, pp. 700-721, 1927. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Epstein and R. Axtell, Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1996.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).