1. Introduction

Eukaryotic microalgae are a large and diverse group of unicellular organisms capable of doing photosynthesis, with high growth rates, resulting in a nutritional biomass with the potential to become a sustainable food source that can be cultivated locally [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Although microalgae biomass is not completely new as a food source, they are niche products, mostly sold in health shops as freeze-dried powder or pills for dietary supplements [

5,

6]. Several factors are limiting consumer acceptance of microalgae in food, including: 1) high cost of production and harvest, 2) often limited digestibility without post-harvest processing and 3) limited organoleptic quality including a “fishy” taste and are considered too green in sensory studies, even when applied in carrier products in small amounts [

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, consumer studies indicate that European consumers know very little about microalgae; what they are, how they are produced, or how they can be applied in food. Such information is crucial for consumers to accept and integrate novel food items in their diet [

10].

Chlorella vulgaris is one of the most popular microalgae species approved for food applications [

11].

C. vulgaris is a green alga with a size in the range of 3-15 µm belonging to the Chlorophyta phylum, from where higher plants have evolved [

12]. The algae can grow under phototrophic, mixotrophic and heterotrophic conditions utilizing organic carbon sources such as glucose and acetate [

13,

14].

The vivid green color of microalgae, often disfavored by consumers, is caused by the presence of chlorophylls; pigments that are key factors in the light harvesting systems of the photosynthetic apparatus and thus essential for carrying out photosynthesis [

15,

16]. Chlorophylls are non-essential when grown under heterotrophic condition, thus the metabolic flexibility of microalgae like

C. vulgaris facilitates a unique possibility for breeding and cultivating pigment deficient strains [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Aside from providing the opportunity to cultivate a pale, chlorophyll-less biomass, the heterotrophic cultivation process entails several other advantages [

13]. The constant struggle to obtain optimal light utilization in phototrophic cultivation is irrelevant in heterotrophic cultivation and as a result the biomass productivity for

Chlorella sp. can be more than 25 times higher than for phototropic cultivation [

13,

21]. Heterotrophic cultivation in addition offers the opportunity to utilize highly turbid side streams as nutrient media otherwise limiting phototrophic cultivation [

17]. Still, heterotrophic algae cultivation also has its drawbacks including an increased risk of bacterial contamination and limited possibility to scale up due to a high oxygen demand which is difficult to obtain in highly dense cultures [

22].

Heterotrophic cultivation of microalgae is gaining increasing interest in the microalgal industry and is a unique opportunity to produce microalgal biomass with reduced color intensity, neutral taste and smell compared to the green wild type [

18,

20]. This can in turn increase consumer acceptance by improving the nutritional quality of the carrier food products like pasta and bread, without negatively impacting the color, taste or smell of the final product [

8,

23]. In this way, heterotrophically cultivated pale algae strains offer consumers a unique opportunity to become more familiar with microalgae as a food source. This familiarity could eventually also pave the way for phototrophic cultivated green algae to be perceived as a more approachable and less alienated food product [

24,

25].

C. vulgaris wild type cultivated in darkness under heterotrophic conditions, have sustained chlorophyll accumulation despite the absence of light [

26]. Unlike higher plants,

C. vulgaris possess a metabolic pathway for light-independent chlorophyll-a synthesis [

27]. Hence, to establish pigment deficient

C. vulgaris for heterotrophic cultivation it is necessary to breed chlorophyll deficient strains. This can be achieved by random mutagenesis which in contrast to genetic engineering approaches provides non-GMO strains that have a higher consumer acceptance than GMO counterparts [

28,

29]. Breeding of pigment

deficient strains of C. vulgaris using random mutagenesis has been achieved using different approaches including ethyl methane sulphonate (EMS) treatment, UVC-radiation and plasma mutagenesis [

18,

19,

20,

30]. In this way mutants with up to 90% decrease of pigments and total absence of chlorophyll has been obtained.

Compared to traditional food crops that over millennia’s and continue to be improved by breeding, microalgae is a novel food source and therefore holds an inexhaustible potential for strain improvement [

31,

32].

This study demonstrates how a simple, fast, and cost-effective workflow can serve as an efficient tool - not only for research but also for breeding novel strains more acceptable to consumers. Using the food-approved green microalgae C. vulgaris as the model organism, chlorophyll-deficient mutants were generated through random mutagenesis by UVC radiation. Two chlorophyll deficient mutants were selected and characterized with respect to: pigment content, biomass productivity, amino acid and lipid content. To study morphological changes in the mutant cells a method based on Cryo Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy (Cryo FIB-SEM) was developed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture Conditions, Mutagenesis and Mutant Selection

A wild type (WT) strain of

Chlorella vulgaris (211/11B) (isolated in the Netherlands by M.W. Beijerinck in 1889) from the Culture Collection of Algae & Protozoa (CCAP) was treated with UVC radiation to generate random mutations. Prior to UVC-radiation the WT strain was decontaminated as described by Raus et al. [

33]. Subsequently the WT was cultivated heterotrophically in 50 ml cell culture flasks containing 30 ml P4-TES media modified from Lippi et al. [

34]. (See Appendix 1 for culture media used). After 5 days of cultivation in darkness on an orbital shaker at 120 rpm at room temperature the culture was applied for UVC-radiation.

2.2. UV Radiation

The heterotrophically cultivated WT C. vulgaris culture was diluted to an optical density of 1.0 (OD750). 3.0 ml of the suspension was added in a thin layer to empty petri-dishes – just enough to cover the surface - and irradiated at 254nm in time intervals between 0- 60 seconds at an energy intensity of 70.000µJ/cm2, 13 cm distance from the UV-source, using a UVC 500 Ultraviolet Crosslinker (Hoefer, Holliston, Massachusetts, USA). To prevent photo-repair by photolyase and to keep the algae in heterotrophic growth mode the plates containing the irradiated algae were placed in darkness for 24h at 23°C. After dark incubation, 100µl each of the UVC-treated cultures including an untreated control were spread on agar plates (modified P4-TES media with glucose as mentioned above incl. 1.2 % agar) and placed dark at 23˚C until colony-growth appeared after 3-4 weeks. From the solid plates, yellow colonies were isolated by transferring them to new solid plates using sterile toothpicks. Strains were re-streaked on plates to ensure each of them was monoculture.

2.3. Screening and Strain Selection

After 3-4 weeks of dark incubation on plates, colonies with a lighter color than the WT were visually selected and re-streaked on new plates (also containing 0.1M glucose) in doublets for incubation with and without light (mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation conditions).

2.4. Cultivation

Growth of mutants was compared to the WT strain in both photo-, mixo- and heterotrophic growth modes. For mixotrophic and heterotrophic modes, growth was carried out in sterile culture flasks with ventilated caps (Avantor, Radnor, PA, USA) containing 25 ml liquid P4-TES media with 0.1M glucose pH 7.5. No glucose was added to the media used for photoautotrophic cultivation. All culture flasks were placed at an orbital shaker at 120 rpm – the ones for photo- and mixotrophic cultivation with constant illumination at 100 µmol m-2 s-1. The flasks for heterotrophic cultivation were covered in aluminum foil. All cultivations were initiated at an optical density of 0.2 OD750 using precultures in heterotrophic growth for all three stains. Cultivation lasted 7 days and to avoid contamination, OD750 was not measured until the last day.

2.5. Dry matter Determination

2 ml of each culture was filtered through pre-weighted Macherey-Nagel MN GF-5 glass fiber filters with 0.4 μm pore size and washed with 25 ml demineralized H2O. Filters were placed in an oven at 100˚C overnight and weighed again.

The volumetric biomass productivity (dry matter [g]/volume [L]) was determined for the three different stains and cultivations.

2.6. Light Microscopy

C. vulgaris WT and the chlorophyll deficient mutants cultivated photo-, mixo- and heterotrophically cells from each culture were visually inspected using a light microscope (Olympus BH2) at 1000 x magnification. “ImageJ” imaging processing software was used to determine the size of living untreated cells (n: 4-8 cells) and the mean size of the two mutants were compared to the wildtype for each mode of cultivation [

35].

2.7. Amino Acid Profile

Protein content was measured as the sum of amino acids. The amino acid profile was analyzed in biological triplicates as described by Gundersen et al (2025) [

36] using 15-30 mg dry biomass. Phototrophic cultivations did not produce sufficient amounts of biomass to determine amino acid profile.

2.8. Total Lipid

A modified version of the Bligh and Dyer method was applied for total lipid extraction [

37,

38]. For each sample, 400 mg dried and homogenized biomass was weighed into an extraction glass. Extraction was performed for approximately 4 min by subsequent addition of methanol, chloroform, and water while mixing. To separate the methanol/water, and chloroform/oil phases, samples were centrifuged at 1400 × g for 10 min. The total lipid content was determined by weighing 15 g of the extract in beakers that were placed in a fume hood for evaporation overnight. Afterwards the lipid content was weighed.

2.9. Pigment Analysis

Pigment extraction: A volume of each culture – normalized to 10 OD units at OD750 - were harvested by centrifugation at 7.000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatant was removed, and pigments were extracted from the pellet using 100% acetone. After extraction, acetone was allowed to evaporate, and the pigments were resuspended in 90:10 Metanol:H2O containing 5 ppm 8-apocarotenal as internal standard. Pigment extracts were filtered employing a 0.2-μm pore size polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Agilent, 203980-100) into a 96-well filter plate prior to analysis.

UHPLC-ESI-qTOF-MS analysis: Pigment extracts were analyzed using an Ultimate 3000 UHPLC+ Focused system (Dionex Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) coupled to a Bruker Compact ESI-QTOF-MS (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) system. The analysis method was based on Bijttebier et al. [

39]. Samples were separated on a ACQUITY UPLC HSS C18 SB Column, 100Å, 1.8 µm, 2.1 mm X 100 mm; Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) with a constant temperature of 40°C and a flow rate of 0.5 ml min-1. Samples were injected with a volume of 5 μL. Mobile phase consisted of A: 50:22.5:22.5:5 water + 5 mM ammonium acetate:methanol:acetonitrile:ethyl acetate and B: 50:50 acetonitrile:ethyl acetate. LC gradient: 0–0.1 min, 10% B; 0.1– 0.8 min, linear increase from 10 to 30% B; 0.8–20 min, increase 30% to 91% B; 20-20.1 min, increase from 91% - 100% B; 20.1-20.4 min isocratic; 20.4 - 20.5 min linear decrease from 100% - 10 % B; 20.5 - 23 min isocratic. Pigments were detected by diode array detector (DAD) 350-700 nm. Mass detection was done in positive mode, with a scan range of m/z 100–900 and 2Hz sample rate. The set-tings for MS and electrospray ionization (ESI) were: Capillary voltage, 4000 V; end plate offset, 500 V; dry gas temperature, 220°C; dry gas flow, 8 L min 1; nebulizer pressure, 2 bar; in source CID energy, 0 eV; hexapole RF, 50 Vpp; quadrupole ion energy, 4 eV; collision cell energy, 7 eV.

Raw chromatogram data was calibrated using an internal sodium formate standard. Data analysis was done with DataAnalysis 4.3 (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) and Sig-maplot 14 (Systat Software Inc, CA, USA). Pigments were quantified by peak area of each pigment measured at UVC absorption at 445 nm. Quantification was done by normalizing to the peak area of 8-apo-carotenal. Relative quantification was normalized to pigment level in the control strain. Identity of all carotenoids mentioned was confirmed by au-thentic standards.

2.10. Cryo Focus Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy for Cryo Volume Electron Microscopy (cvEM)

The WT

C. vulgaris and the two mutants M6 and M11 in linear, heterotrophic growth were vitrified by pipetting (3µL) onto TEM grids (Au, 300 R1.2/1.3, Quantifoil, Germany), blotted (30s at 98% RH) to remove excess media and plunged into liquid ethane (EM GP, Leica Microsystems) at -180˚C causing the cells to vitrify into a glass-like solid meta stable state without formation of ice-crystal [

40] All data was acquired using a JEOL JIB-4700F Z FIB-SEM (JEOL, Japan), equipped with a Leica microsystems EM VCT500 cryo stage and cryo transfer system (Leica Microsystems, Austria). Images were collected as a sequence by sectioning in 50 nm slices by Gallium FIB followed by imaging of the newly exposed face of each cell with SEM. Volumes were initially generated following alignment of image stacks (Stacker-Neo and Visualizer-evo, TEMography.com Japan).

2.11. Quantification of Lipid Volume to Cell Volume

Multiple images were sequentially acquired for each slice. To correct motion artifacts in these time series, a single average projection was obtained, resulting in a single image for each z-slice. This step was performed in ImageJ/Fiji (NIH, USA) with the Z-project command [

41] The 3D volume was then registered using a previously described algorithm [

42]. Briefly, images are first pre-registered using the Linear Stack Alignment with SIFT Fiji plugin [

43] with default settings. Subsequently, the Alignment to Median Smoothed Template (AMST) algorithm is applied to refine registration. Afterwards, the Pixel Classification workflow in Ilastik (

https://www.ilastik.org/) was used to segment individual lipid droplets within the microalgal cells [

44] ImageJ/Fiji was used to manually segment individual cells to provide context for the analysis of lipid droplets. Three cells for each algae strain were analyzed to quantify the total lipid content per cell volume.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted in triplicates except for the lipid content measurements that were only made in duplicates due to insufficient sample amounts. Graphs and statistical analysis were made in “GraphPad prism 10” applying one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if differences between strains and cultivations were significant.

For the pigment analysis: Statistical comparisons between two groups (mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation) were performed using the Student´s t-test. (each pigment from the two mutants was compared pairwise to the reference strain (WT) at each cultivation condition). The data is represented by means +/- standard deviation and the different statistical significances are shown as following: n.s. (not significant), p > 0,05, * p < 0,05, ** p < 0,01 and ***p < 0,001.

3. Results

3.1. UV-Mutagenesis

A wild type strain of

C. vulgaris was treated with UVC-radiation to induce single nucleotide mutations randomly throughout the genome. After 3-4 weeks of incubation, the plates with cells treated with 12-15 sec UVC radiation were the best suited for mutant isolation since colonies were scattered individually including pigment mutants (

Figure 1). UVC exposure for 30 seconds killed all the cells.

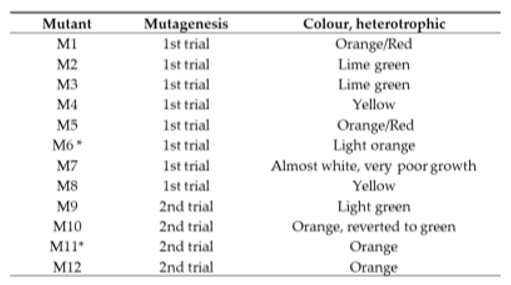

3.2. Selection of Pigment Deficient Mutants

To ensure robustness of the procedure the UVC radiation experiment was performed twice with a reproducible outcome, i.e. 12-15 seconds of UVC radiation resulted in survival of green colonies and a few yellow colonies. From the two UVC experiments, 11 yellow or lime green colonies were selected and re-streaked on fresh plates (

Figure 2) and one mutant, M7, had an albino phenotype and showed poor growth. The 12 mutants are described in

Table 1. To obtain axenic mutant strains and to test mutation stability of the 11 mutants, they were re-streaked on glucose containing agar plates and incubated in the dark. This was repeated 6 times. After obtaining clean cultures the phenotypic stability of the mutants was evaluated under both mixotrophic and heterotrophic conditions. Two of the mutants, M6 and M11, did not revert to green during mixotrophic cultivation conditions. These were selected for further characterization.

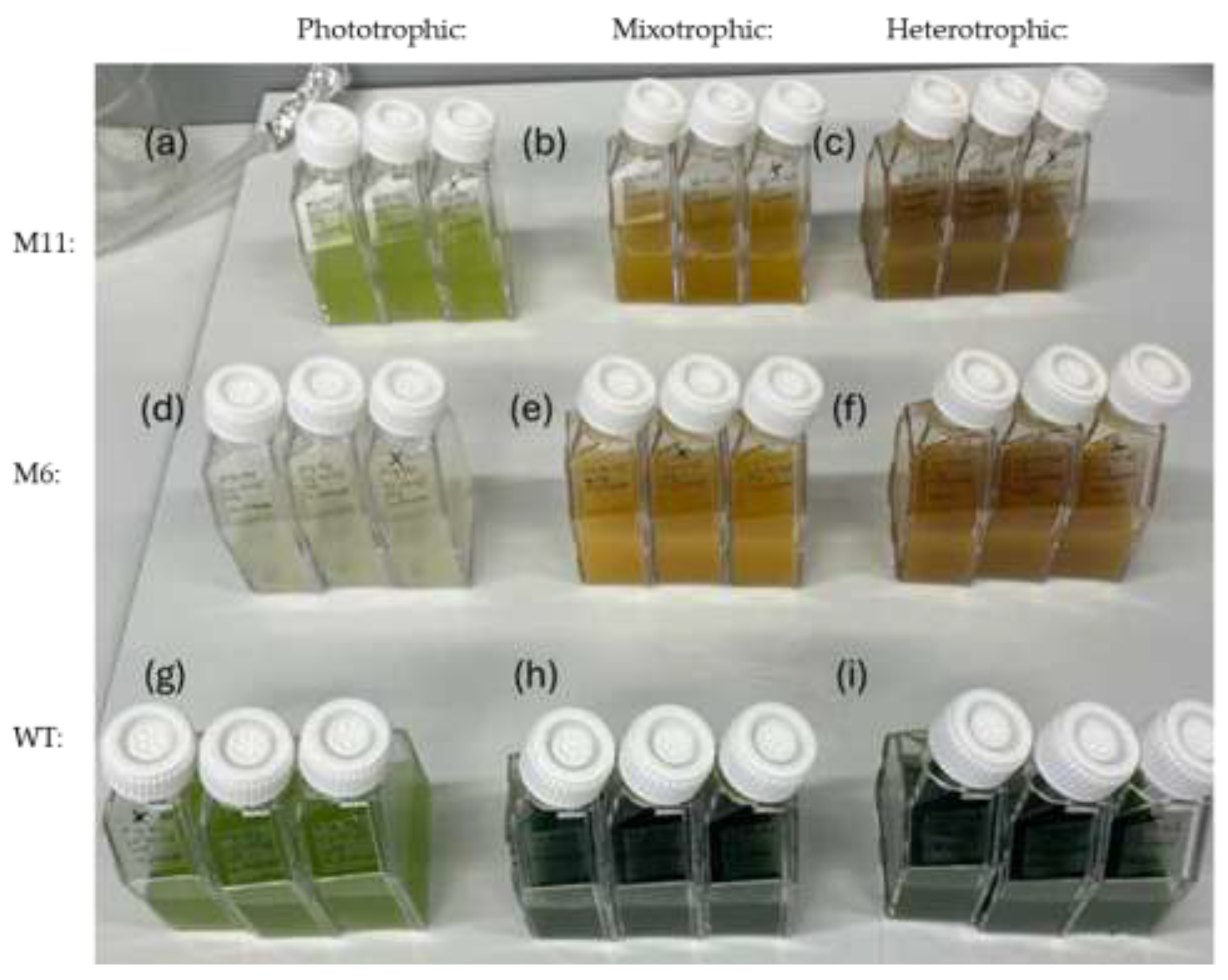

3.3. Cultivations and Biomass Productivity

To gather further information about the phenotypic stability of M6 and M11, the two mutants and the WT were cultivated in liquid media at both photo-, mixo- and hetero-trophic conditions. After seven days of cultivation, the biomass density (OD

750) and dry matter content was measured for all cultivations. As seen in

Figure 3 the color of the cultures varied considerably depending on the type of cultivation.

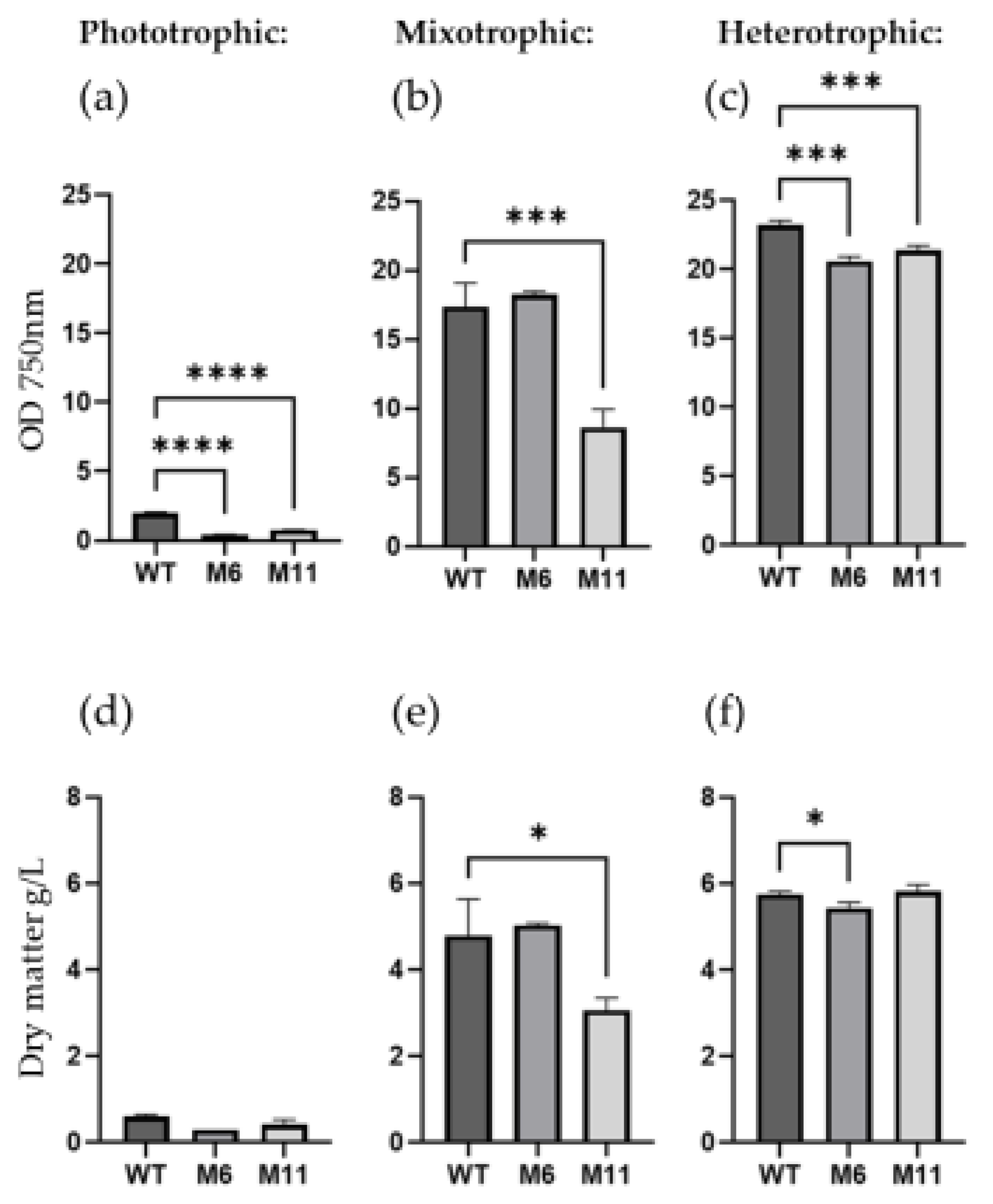

As expected, the WT strain would grow at all trophic modes with maximum growth observed at heterotrophic conditions and the lowest growth at phototrophic cultivation (

Figure 4a). The color of the WT culture was bright green during phototropic cultivation (

Figure 3g) and darker green at both mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation (

Figure 3h and i).

Based on cell density measured by OD

750, the WT grew better than both mutants in heterotrophic conditions (

Figure 4c). However, in heterotrophic conditions the dry matter content of M11 was similar to WT, with both strains accumulating about 6 g dry matter/L in 7 days, while M6 produced slightly less biomass (

Figure 4f). In agreement with the chlorophyll deficient phenotype, no significant increase in biomass or OD

750 was observed for M6 in phototrophic cultivation conditions when compared to WT (

Figure 4d). The culture density (OD

750) of M11 increased from 0.2 to 0.7 during the seven days of phototrophic cultivation (

Figure 4d) in agreement with the M11 culture turning from yellow to light green under phototrophic cultivation (

Figure 3a). Under heterotrophic conditions, M11 doubled the biomass relative to mixotrophic conditions (

Figure 4f and

Figure 4e, respectively).

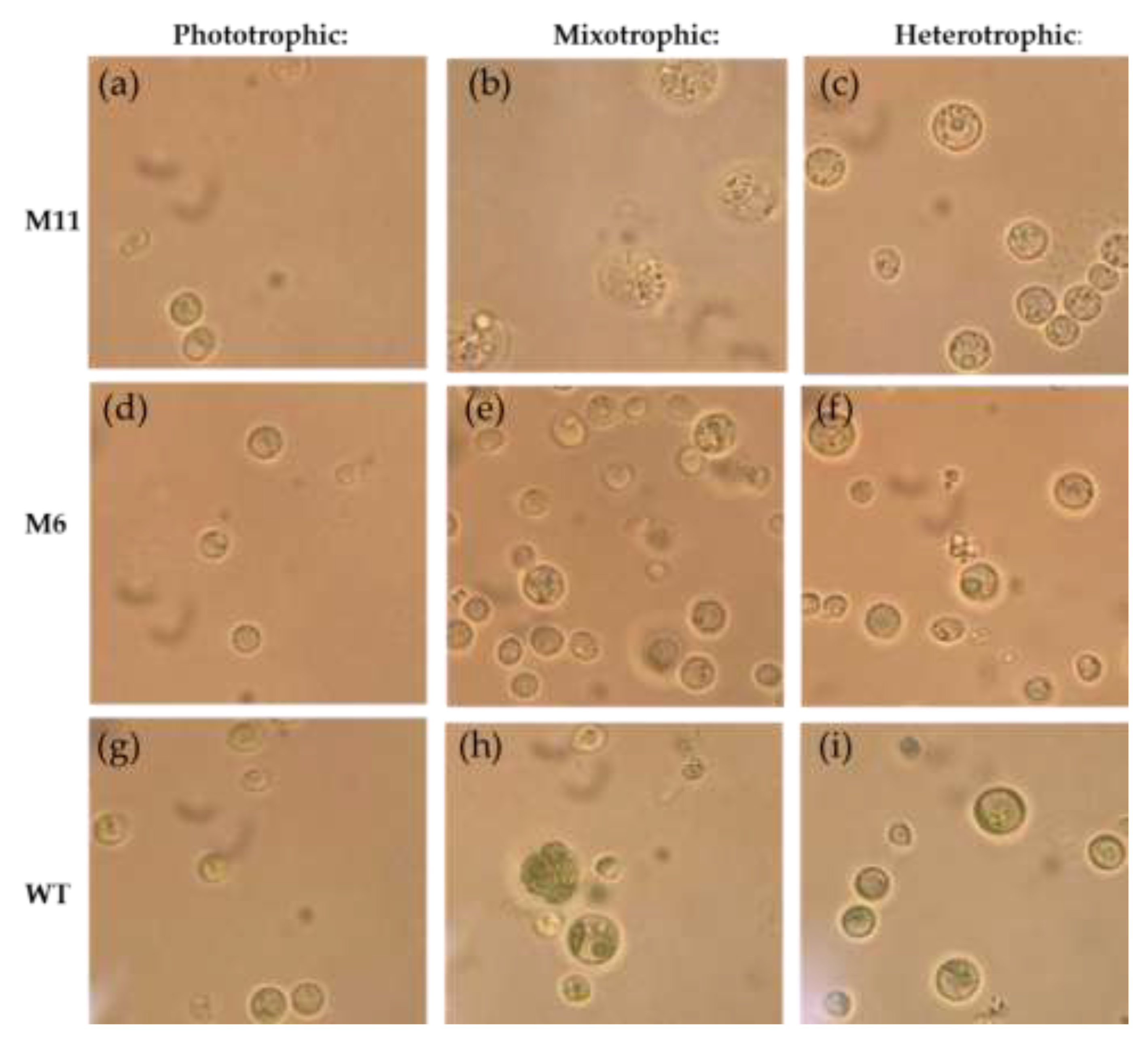

3.4. Visual Inspection Using Light Microscopy and Cell Size Measurement

Light microscopy of cells from the

C. vulgaris WT, mutant M6 and M11 revealed that the morphology of all three cultures varied depending on the mode of cultivation (

Figure 5). Wild type strain had visible chloroplasts in all trophic modes (

Figure 5 g-i), while morphological changes of the chloroplast in M6 and M11 were clearly observed during mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation. In phototrophic cultivation of M11 a structure resembling a chloroplast was identified (

Figure 5a). Furthermore, in mixotrophic cultivation enlarged cells of M11 appeared “grainier” compared to the phototrophic and heterotrophically cultivated cells. A ring-shaped object resembling the pyrenoid could be identified in WT M6, and M11 cells from all cultivation modes.

The measured cell diameters varied between 2.5 – 5.9 µm. The only significant difference was observed between the WT and mutant M11 cells during mixotrophic cultivation where the M11 cells were significantly larger (ca. 5.9 µm) than the WT cells (ca. 3.1 µm) (

Figure S2, supplemental).

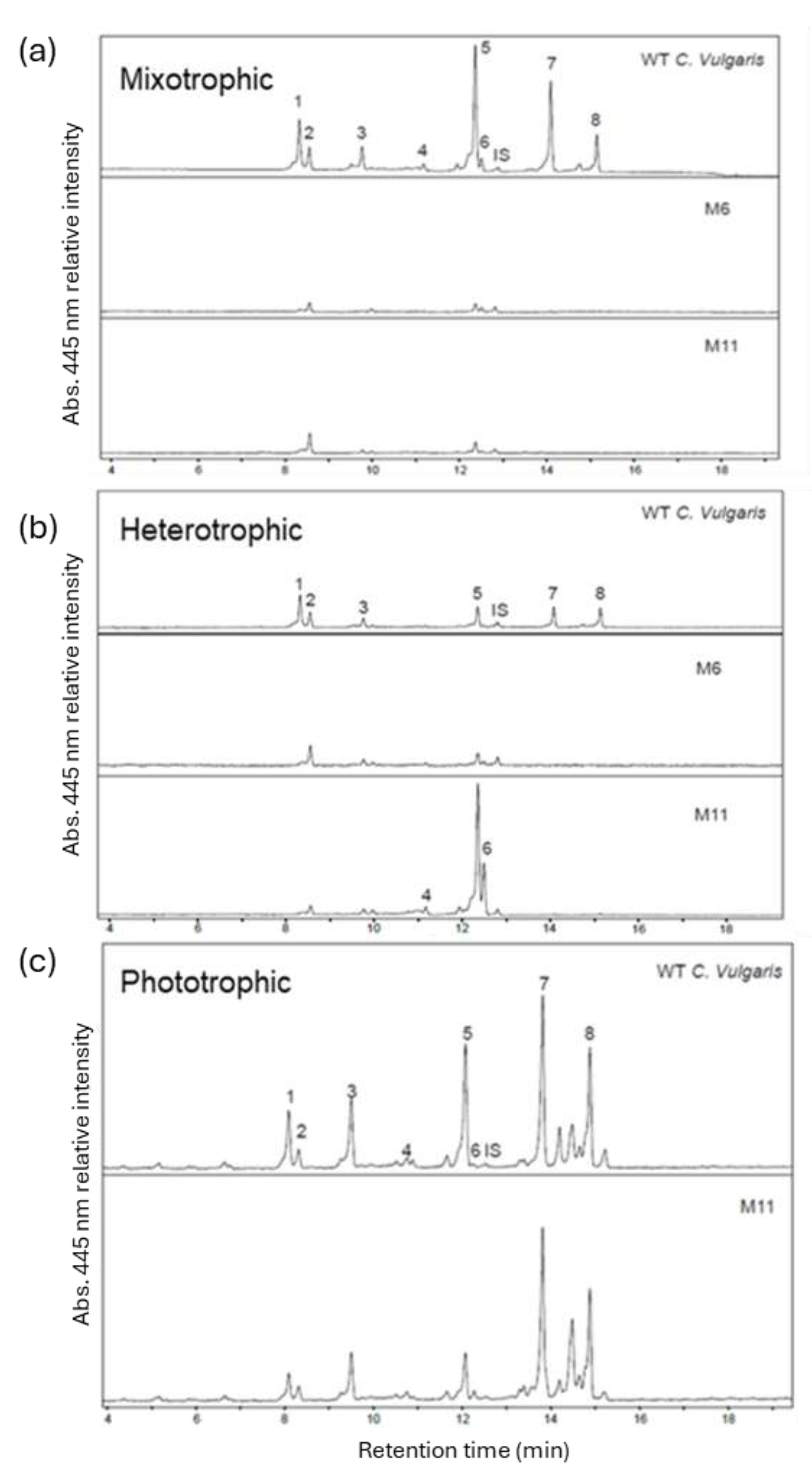

3.5. Analysis of Pigment Composition

To investigate how the yellow mutants M6 and M11 were affected in their overall pigment composition, pigments from the two mutants and the WT from both photo- mixo- and heterotrophic cultivations were extracted and analyzed using HPLC. The chromatograms revealed that mutant M6 had a severely reduced pigment content relative to the WT at both mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivations without any detectable chlorophyll a or b (

Figure 6). M6 did not grow during phototrophic conditions and therefore the pigments were not analyzed.

In pigment extracts of M11 cultivated in phototrophic conditions both Chl a and b could be detected, and the level of lutein was significantly lower than for the WT (

Figure 6 and

Figure S3, supplemental). Zeaxanthin levels were significantly higher in M11 when compared to WT (

Figure S3, supplemental). After seven days of heterotrophic cultivation M11 had significantly higher content of the three carotenoids: zeaxanthin, lutein and antheraxanthin: 20, 5 and 2-fold higher compared to levels in WT pigment extracts (

Figure S3, supplemental).

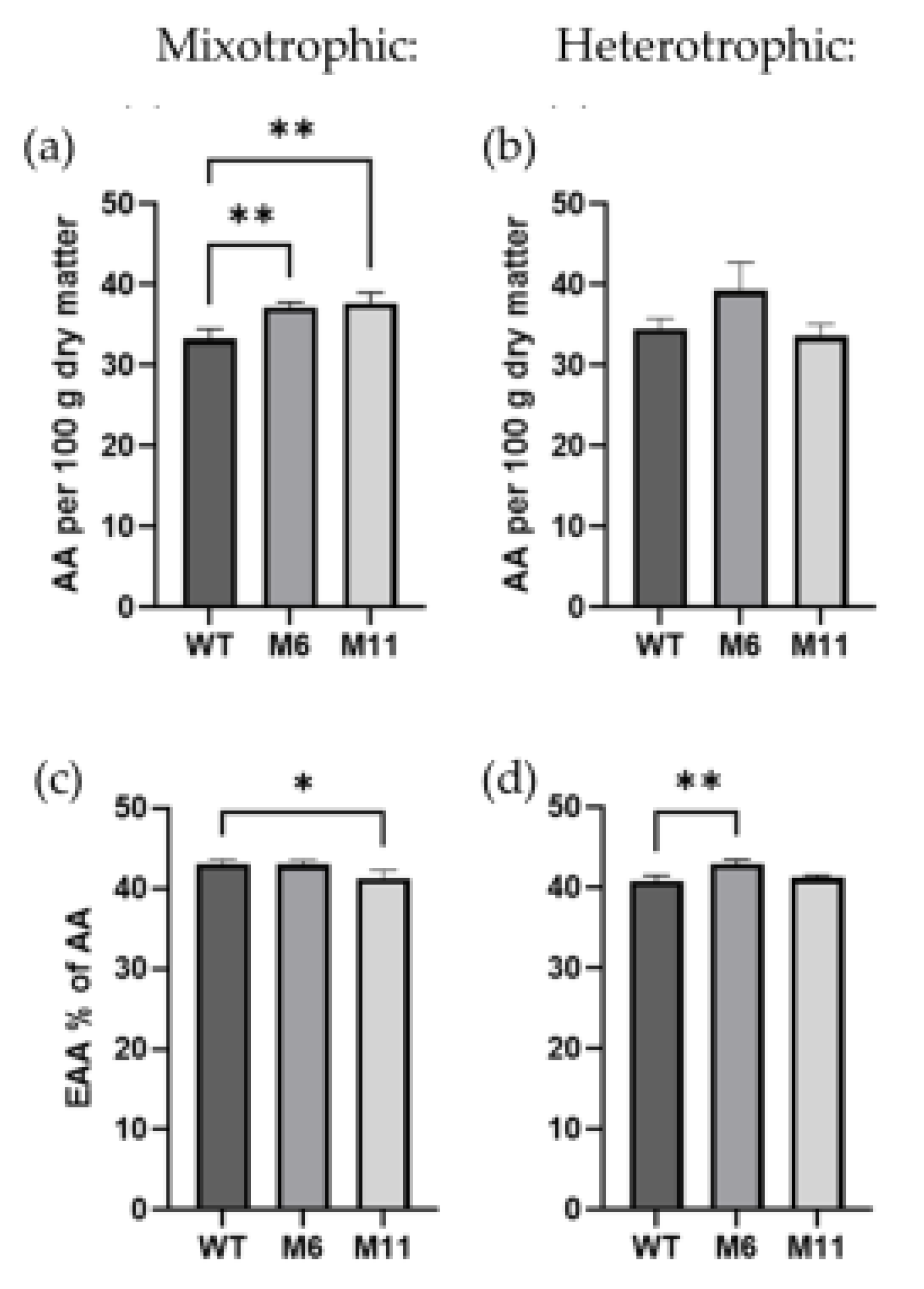

3.6. Amino acid Content and Composition

To investigate potential changes in amino acid content and composition, the amino acid profile was analyzed in WT

C. vulgaris as well as the M6 and M11 mutants grown mixotrophically and heterotrophically. The total amino acid content (

Figure 7a) was significantly higher in both mutants during mixotrophic cultivation, with the WT containing 33.3 % AAs (dry weight basis) compared to 37.2 % in M6 and 37.7 % in M11. There was no significant difference between amino acid content in the three strains when cultivated heterotrophically (

Figure 7b). When comparing the fraction of essential amino acids (EAA) of the total amino acid content, mutant M11 contained slightly less EAA (41.3 %) than the wildtype (43.1 %) at mixotrophic cultivation conditions (

Figure 7c). During heterotrophic cultivation, mutant M6 contained significantly more EAA than the WT (5.2 % more) (

Figure 7d). An overview of the content of each essential amino acid (mg/g dry matter) for the three

C. vulgaris strains at mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation conditions can be found in the supplementary material (

Table S1).

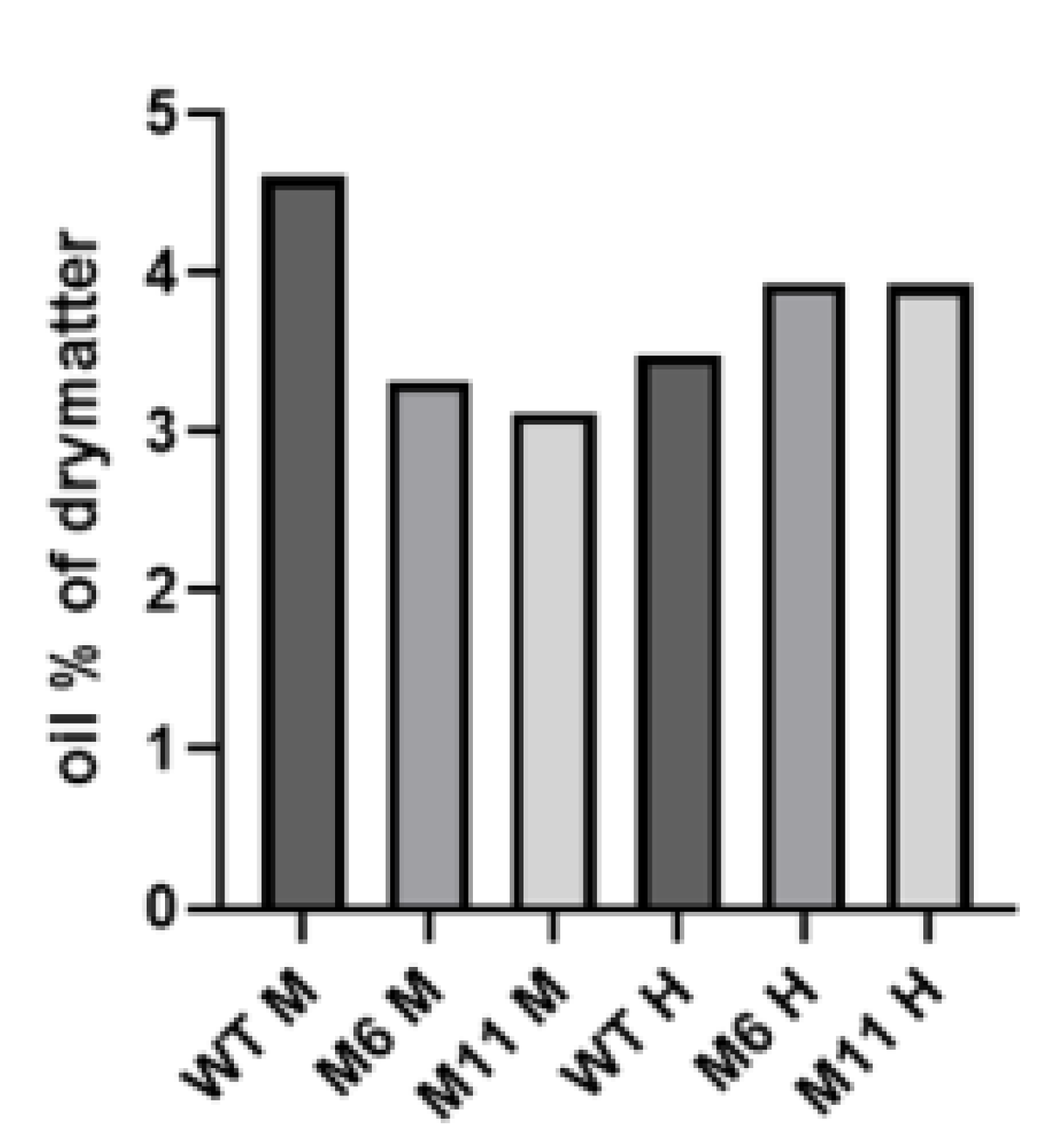

3.7. Total Lipid Content

In addition to amino acids, it was of interest to investigate whether there were any differences in lipid content in the mutants compared to the WT strain. The lipid content was measured in the dry biomass produced from mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivations. Due to an insufficient amount of sample material, only a single measurement was carried out for each strain. Still, the lipid content for all three strains at the two different cultivation modes were all very similar, varying between 3.1% and 4.5% of dry matter (

Figure 8). During mixotrophic cultivation the WT strain seemed to have a higher lipid content than the two mutants.

3.8. Analysis of Cellular Structures Using Cryo Focused Ion Beam Scanning Microscopy (Cryo FIB-SEM)

Cryo FIB-SEM micrographs were obtained for the three algae strains cultivated under heterotorphic conditions. Ion-beam sequential serial sectioning milling provided visualization of the ultrastructure throughout the entire cell volume generating 3D volume z-stacks of multiple cells of each algal strain. The morphological diversity within each strain is shown in micrographs from three individual cells of both the WT, M6, and M11 (

Figure 10).

C. vulgaris WT cells all have fully developed chloroplasts with thylakoid membranes and a starch-rich pyrenoid (

Figure 9a-c). M6 has a rudimentary chloroplast/plastid encased by an outer membrane but only containing fragments of what appears to be poorly developed thylakoid membranes (

Figure 9d, f). Ultrastructures resembling pyrenoids could not be observed, while structures resembling starch grains could be seen.

The ultrastructure of M11 where similar to M6 with a few structures resembling rudimentary thylakoid membranes and no distinctive pyrenoid present (

Figure 9g-i). Clusters of what is likely to be starch and rubisco-rich matrix could be observed.

Figure 9.

Cryo FIB-SEM micrograps of

C. vulgaris strains. Three individual cells for each strain, all from heterotrophic cultivations. (a-c):

C. vulgaris WT. (d-f): Mutant M6: chloroplast without thylakoid membranes. Chloroplast membrane (arrow) with fragments of rudimentary thylakoid membranes. No real pyrenoid only starch and rubisco-rich matrix. (g-i): Mutant M11: No chloroplast only rudimentary membranes indicated by “t?. No distinctive pyrenoid, multiple vesicles. Presumptive organelles: Chl: chloroplast, t: thylakoid membrane, M: mitochondrion, n: nucleus, p: pyrenoid, l: lipid droplet, s: starch, r: rubisco-rich matrix, v: vesicle, cw: cell wall. Scale bars represent 1 µm. Original micrographs:

Figure S5a-i, supplemental.

Figure 9.

Cryo FIB-SEM micrograps of

C. vulgaris strains. Three individual cells for each strain, all from heterotrophic cultivations. (a-c):

C. vulgaris WT. (d-f): Mutant M6: chloroplast without thylakoid membranes. Chloroplast membrane (arrow) with fragments of rudimentary thylakoid membranes. No real pyrenoid only starch and rubisco-rich matrix. (g-i): Mutant M11: No chloroplast only rudimentary membranes indicated by “t?. No distinctive pyrenoid, multiple vesicles. Presumptive organelles: Chl: chloroplast, t: thylakoid membrane, M: mitochondrion, n: nucleus, p: pyrenoid, l: lipid droplet, s: starch, r: rubisco-rich matrix, v: vesicle, cw: cell wall. Scale bars represent 1 µm. Original micrographs:

Figure S5a-i, supplemental.

Figure 10.

Cryo-Volume Electron Microscopy (cvEM) with 3D visualization of lipids droplets contained in individual cells (a) WT cvEM volume 1, (b) M6 cvEM volume 1 (c) M11 cvEM volume 1 (d) WT cvEM volume 2, (e) M6 cvEM volume 2 (f) M11 cvEM volume 2. Scale bars represent 1 µm.

Figure 10.

Cryo-Volume Electron Microscopy (cvEM) with 3D visualization of lipids droplets contained in individual cells (a) WT cvEM volume 1, (b) M6 cvEM volume 1 (c) M11 cvEM volume 1 (d) WT cvEM volume 2, (e) M6 cvEM volume 2 (f) M11 cvEM volume 2. Scale bars represent 1 µm.

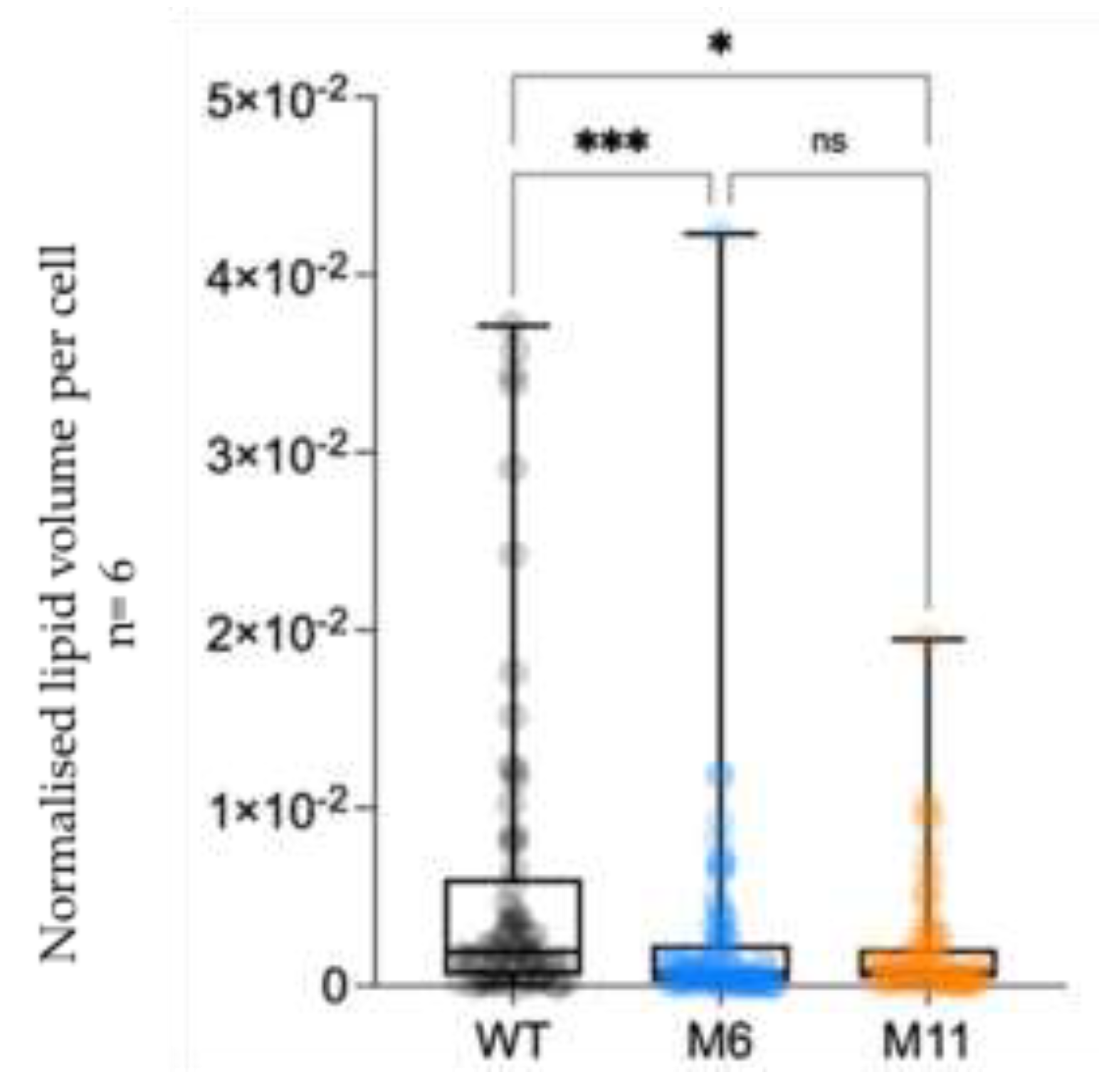

The 3D volume analysis of the cryo FIB-SEM micrographs illustrate the WT lipid droplets inside 3 cells of the WT and mutants (

Figure 10) and quantification of the lipid droplet to cell volume (

Figure 11). See (

Figure S4, supplemental) for an overview of the complete volume with multiple cells and lipid droplets, illustrating the approach used for lipid identification and quantification across whole volumes.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Chlorella vulgaris is a highly nutritious green algae and one of the bestselling food approved microalgae on the market [

11]. However, its use as a main food ingredient is impeded by a high chlorophyll content causing unfavorable organoleptic traits including a bitter taste and an intense green color disliked by the consumers [

23,

45].

In this work 12 chlorophyll deficient mutants of the green algae

C. vulgaris were generated using UVC-radiation with subsequent visual screening. Based on two independent UVC-radiation trials, the optimal UVC radiation time for successful selection of colonies was 12-15 seconds with the crosslinker and energy setting applied in this study. Other studies applying a different UV-treatment system for breeding of

C. vulgaris have required up to 25-30 min UVC radiation [

20,

46]. These differences in UVC-exposure time are impacted by various factors such as radiation intensity, distance to the light source and culture density and depth of the treated algae suspension.

Based on their chlorophyll deficiency, fast growth and mutation stability, the two mutants M6 and M11 were selected for further characterization and comparison to the WT with respect to biomass yield, pigment-, amino acid- and lipid content when cultivated at different trophic modes. Also, the ultrastructure of the two mutants was compared to the wildtype at their native state during heterotrophic growth.

4.1. Ultrastructure

In addition to the biochemical characterization of the three algae strains, the ultrastructure of the two mutants was compared to the WT: all cultivated at heterotrophic conditions. Observed morphological differences between the strains can elucidate the physiological impact of the mutations and eventually serve as a guide in the search for the mutated genes.

The cryo FIB-SEM data suggests that the rubisco-rich matrix, which is the innermost part of the pyrenoid is present in M6 and M11 even though the thylakoid membranes are poorly developed (

Figure 9d-i) [

47]. This would potentially explain the unchanged total amino acid content which is a proxy for the protein content. The few thylakoid-like structures formed in the plastids of the two mutants were often seen directed at the rudimentary pyrenoid, suggesting that the connection between thylakoids and the pyrenoid is an initial part of the chloroplast development in

C. vulgaris. This seems plausible since it creates the interconnection of the light dependent and light independent reactions – a prerequisite for a functional photosynthetic apparatus in an alga like

C. vulgaris [47.48].

Variation in cell size was observed between trophic growth modes, where the M11 cells were significantly larger than WT and M6 in mixotrophic cultivation (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), (S1, supplemental). The 3D analysis of the volume of oil droplets within individual cells revealed a difference in the distribution of droplet sizes between the WT and the two mutants. Furthermore, the total volume of lipid bodies in WT cells was higher than M6 and M11, which is consistent with the lipid analysis data. Our Cryo-Volume Electron Microscopy (cvEM) approach provided greater volumes for analysis of ultrastructural changes at whole cell level, by using the cryo FIB-SEM to sequentially section and image entire cells, offering greater insight into the changes induced by mutation within organelle and throughout the cell. The combination of vitrification and cvEM avoided artefacts affecting cell content, their distribution, organization and volume induced by more traditional EM sample preparation approaches. Thus, allowing direct quantitative comparisons between WT and mutant strains.

4.2. Pigment Content

Pigment extraction and HPLC analysis revealed that the two mutants remained chlorophyll-less in both mixotrophic and heterotrophic conditions. During heterotrophic cultivation M11 accumulated considerably higher amounts of the carotenoids zeaxanthin, lutein and antheraxanthin than M6 and the WT with up to 25-fold more zeaxanthin. This result is interesting as an increased accumulation of these carotenoids is usually triggered by highlight intensities [

49].

Both zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin are products of the xanthophyll cycle which is driven by the two enzymes, violaxanthin de-epoxidase (VDE) and zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZE) [

50]. In WT chloroplasts, VDE is located in the thylakoid lumen but when pH drops – usually because of increased light intensities and proton accumulation – the enzyme binds to the thylakoid membrane and is activated to catalyze the conversion of violaxanthin to zeaxanthin via antheraxanthin [

51]. Even though the synthesis of both lutein and zeaxanthin is a response to highlight intensities, their accumulation in darkness have previously been observed in other studies [

52,

53]. Oxygen limitation has been reported as a stress factor that can lead to zeaxanthin production in darkness in different photosynthetic eucaryotes [

52]. Other factors that can induce carotenoid accumulation in microalgae are increased salinity or nutrient deprivation. However, in the current study these stress factors are unlikely since the applied media does not contain NaCl and is very nutrient rich made for high density microalgae cultivation yielding up to 30 g algal biomass (dry matter) per liter culture [

34] which is approx. 5 times more than the highest biomass densities observed in the current study.

Furthermore, the pigment analysis revealed that mutant M6 had lost the ability to accumulate chlorophylls and was unable to grow in phototrophic cultivation conditions. The pigment profiles for M11 varied greatly between mixotrophic and phototrophic cultivation with an overall low pigment content at phototrophic cultivation and with no chlorophylls detected in either mixotrophic or heterotrophic cultivation. It appears that M11 has a mutation affecting the chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway. Besides a specific mutation in one of the genes encoding chlorophyll biosynthetic genes, various other factors could give rise to such an outcome. One example is catabolite repression where the presence of glucose (which is also the product of photosynthesis) suppresses the synthesis of enzymes involved in e.g. chlorophyll synthesis. Glucose has been shown to be a repressor of chlorophyll in the red algae

Galdieria partita where addition of 1% glucose to the media inhibited the oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX which is one of the steps of heme and chlorophyll synthesis [

54,

55]. The reason for the mixotrophic dependent chlorophyl deficiency phenotype of M11 is not clear and needs further investigations.

The high carotenoid level observed for M11 during heterotrophic cultivation potentially makes this strain a promising candidate for industrial production. Carotenoids are valuable bioproducts, but their synthesis is hard to improve during photoautotrophic cultivations, since a high carotenoid content will reduce photosynthetic efficiency due to their photoprotective nature [

53]. This paradox can be solved by heterotrophic cultivation of mutants such as M11 accumulating carotenoids in the dark.

4.3. Biomass Productivity

Although the phototrophic growth of the WT strain was low compared to the mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivations it is comparable to the productivity obtained in other studies cultivating

C. vulgaris phototrophically at a similar light intensity [

56]. Both mutants and WT had the highest biomass productivity at heterotrophic cultivation conditions, and as expected for a chlorophyll-less mutant, M6 was unable to grow phototrophically. However, M11 could synthesize pigments including chlorophyll during phototrophic cultivation, but significantly less than the WT.

At mixotrophic cultivation, M11 produced almost 50% less biomass than at heterotrophic conditions (3.1 vs 5.8 g dm/L) which could be caused by production of ROS damaging the cells [

57] which could originate from chlorophylls or its intermediates accumulating in the mutant during mixotrophic cultivation.

The biomass productivities obtained for both wildtype and pigment mutants during heterotrophic cultivation are comparable to the results obtained in other studies breeding pigment deficient mutants of

C. vulgaris [

18,

19,

30]. In the current study the highest biomass yields were obtained during heterotrophic cultivation for both the two chlorophyll deficient mutants and WT - this same trend was also observed by Schüler et al [

18]. Usually, a

C. vulgaris WT can be expected to grow best at mixotrophic conditions due to the combined benefit of having both an organic carbon source and light energy source [

15]. However, it cannot be ruled out that the use of a heterotrophically cultivated inoculum for both photo-, mixo- and heterotrophic cultivations, as in the current study may have contributed to this result by applying a preculture adapted to heterotrophic growth. Furthermore, it is important to stress that even though the cultivation parameters required for mixotrophic growth are applied, it is not the same as the algae utilizing the organic carbon source and light energy simultaneously [

13].

4.4. Biomass Composition

The protein content estimated from the total amino acid content of the biomass (dry matter) was significantly higher in the two mutants than the WT during mixotrophic cultivation with 33.7% for the WT, 37.2% for M6 and 37.7% in M11. At heterotrophic cultivation, the amino acid content did not vary significantly between the three strains. In general, the protein content observed in this study is similar to the content observed for other pigment deficient

Chlorella strains described in the literature [

30]. However, the protein content was higher in the pale

C. vulgaris mutants bred by (Schüler et al. (2020) [

18] at both mixotrophic at heterotrophic cultivation conditions (39.5 - 48.7%). The high measured protein content in that study is likely due to the calculation method as the protein content was obtained by multiplying the total nitrogen content with the nitrogen to protein conversion factor 6.25 which overestimates the true protein content in green microalgae, where the nitrogen to protein conversion factor is closer to 5.5 [

58,

59].

In the current study, the protein quality of the three algae strains was also analyzed with respect to the sum of essential amino acids relative to the total amino acid content (

Figure 7). At mixotrophic cultivation M11 had a slightly lower EAA% of the total protein content than the WT (41.3% vs. 43.1%) whereas M6 had the highest content during heterotrophic growth (42%). This content of EAA is comparable to the values reported for other chlorophyll deficient

Chlorella mutants and other green algae [

19,

57]. An EEA content in this range is comparable to eggs and meat, and an indication of a good protein quality and for human dietary requirements [

60].

The lipid content of the three algae strains varied between 3.1% and 4.1% (per dry matter). A lipid content in this range is low for microalgae including

C. vulgaris where the lipid content often is somewhere between 15-25% of the dry matter for cultures grown in heterotrophic conditions [

18,

61]. High lipid content in microalgae can be induced via stress including nutrient depletion and/or high light intensities [

62]. A likely explanation for the low lipid content observed in the WT strain in this study could be a result of using a highly nutrient-rich medium which is an effect previously observed when cultivating

C. vulgaris in nutrient-rich media [

63].

While the lipid analysis was based on single measurements for each strain in the tested conditions, the obtained data aligns well with the lipid quantification based on lipid droplet volume relative to cell volume obtained from the cryo FIB-SEM data (

Figure 11 and Figure 12). It appears that M6 and M11 without fully developed chloroplasts contain many small lipid droplets, whereas the WT, with an intact chloroplast, has fewer but larger lipid droplets. Chloroplasts are involved in various metabolic pathways, including fatty acid synthesis. It could therefore be speculated that the compromised thylakoids observed in M6 and M11 cells is associated disruption of the cellular machinery involved in lipid for-mation compromised which can be expected to cause a reduction of the total lipid content and the dispersion of lipids into smaller droplets.

The total carbohydrate content of the agal biomasses were estimated as the residual biomass not being protein or lipids. Thus, an amino acid content at about 40% and a lipid content around 3.5% suggest that all three strains likely have a high starch content, which was also indicated by the cryo FIB-SEM micrographs.

In conclusion, strains with improved traits for increased consumer acceptance have been obtained in this study without compromising the nutritional quality of the biomass. This has been achieved using random mutagenesis and a simple visual screening process. These are simple but powerful tools that should not be underestimated. While the field of site-directed genome editing is both fascinating and groundbreaking, this study highlights the inherent complexity of biological systems, which often surpasses our predictive capabilities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, See separate file containing supplemental materials including original micrographs.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, M.L.O, P.E.J.; methodology, M.L.O., P.E.J., D.P.H., M.K., R.A.F., S.M., D.M., validation, M.L.O., D.P.H., J.A.R., M.K., S.M., and P.E.J., formal analysis, M.L.O., D.P.H., M.K., E.G., and D.O.Y., investigation, M.L.O., D.P.H., J.F.B.T., and M.K., resources, P.E.J, C.J., J.A.R., and R.A.F., writing—original draft preparation, M.L.O.; writing—review and editing, P.E.J., D.H.P., M.K., S.M., E.G., and R.A.F. visualization, M.L.O., M.K., D.P.H., and S.M.; supervision, P.E.J.; project administration, M.L.O., and P.E.J.; funding acquisition, P.E.J., C.J., and R.A.F.; correspondence, P.E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work presented herein was part of the MASSPROVIT project, funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark, grant number 1127-00261B. cvEM development was funded by Royal Society, UK grant number INF\R2\202061 and BBSRC, UK grant number BB/Z514962/1 with funding for M.K. from NanoMEGAS SRL and JEOL UK Ltd. Pigment analysis by D.P.H funded by Novo Nordisk Foundation grant NNF21OC0070602.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AA Amino Acids

AMST Alignment to Median Smoothed Template

ANOVA Analysis of Variance

CCAP Culture Collection of Algae & Protozoa

cvEM Cryo Volume Electron Microscopy

Cryo FIB-SEM Cryo Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy

EAA Essential Amino Acids

EMS Ethyl Methane Sulphonate

ESI Electrospray Ionization

HPLC High Performance Liquid Chromatography

LC-MS Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry

OD750 Optical Density at 750 nm

PVDF Polyvinylidene Fluoride

ROS Reactive Oxygen Species

UHPLC Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography

UVC Ultraviolet C

CVDE Violaxanthin De-epoxidase

WT Wild Type

ZE Zeaxanthin Epoxidase

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Recipe for the Modified P4-TES Medium Applied in This Study: A.1

Base medium: Prepare 1 liter of P4-TES medium according to the original formulation described by Lippi et al. (2018) [

34].

Glucose addition: Add 18 g glucose (0.1 M) before autoclaving for mixotrophic or heterotrophic cultivation.

Vitamin supplementation: After cooling, add vitamins by sterile filtration:

Vitamin B1 (thiamine): Prepare a stock of 0.12 g thiamine hydrochloride in 100 mL distilled water. Add 1ml stock to achieve a final concentration of 3.6 µM.

Vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin): Prepare a stock of g cyanocobalamin in 100 mL distilled water. Add 1 ml stock to achieve a final concentration of 0.738 µM.

References

- Canelli, G.; Tarnutzer, C.; Carpine, R.; Neutsch, L.; Bolten, C.J.; Dionisi, F.; Mathys, A. Biochemical and Nutritional Evaluation of Chlorella and Auxenochlorella Biomasses Relevant for Food Application. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 565996. [CrossRef]

- Draaisma, R.B.; Wijffels, R.H.; (Ellen) Slegers, P.; Brentner, L.B.; Roy, A.; Barbosa, M.J. Food Commodities from Microalgae. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2013, 24, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Microalgae for Human and Animal Nutrition. In Handbook of Microalgal Culture; Richmond, A., Hu, Q., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 461–503 ISBN 978-1-118-56716-6.

- Barbosa, M.J.; Janssen, M.; Südfeld, C.; D’Adamo, S.; Wijffels, R.H. Hypes, Hopes, and the Way Forward for Microalgal Bio-technology. Trends in Biotechnology 2023, 41, 452–471. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.D.; Vasconcelos, V. Legal Aspects of Microalgae in the European Food Sector. Foods 2023, 13, 124. [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ghosh, S.; Dubinsky, Z.; Verdelho, V.; Iluz, D. Unconventional High-Value Products from Microalgae: A Review. Bio-resource Technology 2021, 329, 124895. [CrossRef]

- Weinrich, R.; Elshiewy, O. A Cross-Country Analysis of How Food-Related Lifestyles Impact Consumers’ Attitudes towards Microalgae Consumption. Algal Research 2023, 70, 102999. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.L.; Olsen, K.; Jensen, P.E. Consumer Acceptance of Microalgae as a Novel Food - Where Are We Now? And How to Get Further. Physiologia Plantarum 2024, 176, e14337. [CrossRef]

- Falcão, R.L.; Pinheiro, V.; Ribeiro, C.; Sousa, I.; Raymundo, A.; Nunes, M.C. Nutritional Improvement of Fresh Cheese with Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris: Impact on Composition, Structure and Sensory Acceptance. Food Technol. Biotechnol. (Online) 2023, 61, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T. Effect of Microalgal Biomass Incorporation into Foods: Nutritional and Sensorial Attributes of the End Products. Algal Research 2019, 41, 101566. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.G.A.; Reis, A.; Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.; Verdelho, V.; Llamas, B. The Role of Microalgae in the Bioeconomy. New Biotechnology 2021, 61, 99–107. [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.-S.; Lee, B.; Jeong, B.; Chang, Y.K.; Kwon, J.-H. Truncated Light-Harvesting Chlorophyll Antenna Size in Chlorella Vulgaris Improves Biomass Productivity. J Appl Phycol 2016, 28, 3193–3202. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, A.P.; Morais, R.C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Nunes, J. A Comparison between Microalgal Autotrophic Growth and Metabolite Accumulation with Heterotrophic, Mixotrophic and Photoheterotrophic Cultivation Modes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 159, 112247. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Wijffels, R.H.; Dominguez, M.; Barbosa, M.J. Heterotrophic vs Autotrophic Production of Microalgae: Bringing Some Light into the Everlasting Cost Controversy. Algal Research 2022, 64, 102698. [CrossRef]

- Milrad, Y.; Mosebach, L.; Buchert, F. Regulation of Microalgal Photosynthetic Electron Transfer. Plants 2024, 13, 2103. [CrossRef]

- Willows, R.D. Biosynthesis of Chlorophyll and Bilins in Algae. In Photosynthesis in Algae: Biochemical and Physiological Mechanisms; Larkum, A.W.D., Grossman, A.R., Raven, J.A., Eds.; Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration; Springer In-ternational Publishing: Cham, 2020; Vol. 45, pp. 83–103 ISBN 978-3-030-33396-6.

- Trovão, M.; Schüler, L.M.; Machado, A.; Bombo, G.; Navalho, S.; Barros, A.; Pereira, H.; Silva, J.; Freitas, F.; Varela, J. Random Mutagenesis as a Promising Tool for Microalgal Strain Improvement towards Industrial Production. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 440. [CrossRef]

- Schüler, L.; Greque de Morais, E.; Trovão, M.; Machado, A.; Carvalho, B.; Carneiro, M.; Maia, I.; Soares, M.; Duarte, P.; Barros, A.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Chlorella Vulgaris Mutants With Low Chlorophyll and Improved Protein Contents for Food Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 469. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Gao, Y.; Mou, H.; Zhu, C.; Sun, H. Development of Fast-Growing Chloro-phyll-Deficient Chlorella Pyrenoidosa Mutant Using Atmospheric and Room Temperature Plasma Mutagenesis. Bioresource Technology 2025, 132245. [CrossRef]

- Jian, J.; Torres-Montero, P.; Bai, M.; Lu, Y.; Simonsen, H.T. Genome Analysis of Chlorella Vulgaris (CCAP 211/12) Mutants Provided Insight into the Molecular Basis of Chlorophyll Deficiency. Algal Research 2024, 78, 103426. [CrossRef]

- Han, K.H.; Li, Z.; Park, B.S.; Jung, M.S.; Kim, M.; Kwon, K.K.; Youn, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, D.B.; Kim, J.-H.; et al. Exploration of a Cultivation Strategy to Improve Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Production and Growth of a Korean Strain of Nannochloropsis Oceanica Cultivated under Different Light Sources. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2025, 18, 55. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; Olivieri, G.; de Vree, J.; Bosma, R.; Willems, P.; Reith, J.H.; Eppink, M.H.M.; Kleinegris, D.M.M.; Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.J. Towards Industrial Products from Microalgae. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 3036–3043. [CrossRef]

- Grahl, S.; Strack, M.; Mensching, A.; Mörlein, D. Alternative Protein Sources in Western Diets: Food Product Development and Consumer Acceptance of Spirulina-Filled Pasta. Food Quality and Preference 2020, 84, 103933. [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer Acceptance of Novel Food Technologies. Nat Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Vollmecke, T.A. Food Likes and Dislikes. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1986, 6, 433–456. [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovska, M.; Orgnero, S.; Hüner, N.P.A.; Smith, D.R. The Enigmatic Loss of Light-independent Chlorophyll Biosynthesis from an Antarctic Green Alga in a Light-limited Environment. New Phytologist 2019, 222, 651–656. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liao, W.; Dawuda, M.M.; Hu, L.; Yu, J. 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA) Biosynthetic and Metabolic Pathways and Its Role in Higher Plants: A Review. Plant Growth Regul 2019, 87, 357–374. [CrossRef]

- Bearth, A.; Siegrist, M. “As Long as It Is Not Irradiated” – Influencing Factors of US Consumers’ Acceptance of Food Irradiation. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 71, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Marette, S.; Disdier, A.-C.; Beghin, J.C. A Comparison of EU and US Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Gene-Edited Food: Evidence from Apples. Appetite 2021, 159, 105064. [CrossRef]

- Trovão, M.; Barros, A.; Machado, A.; Reis, A.; Pedroso, H.; Espírito Santo, G.; Correia, N.; Costa, M.; Ferreira, S.; Cardoso, H.; et al. Heterotrophic Cultivation of Chlorella Vulgaris Yellow Mutant on Sidestreams: Medium Formulation and Process Scale-Up. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 115361. [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, N.E. Contributions of Conventional Plant Breeding to Food Production. Science 1983, 219, 689–693. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, J.E. Plant Breeding: Past, Present and Future. Euphytica 2017, 213, 60. [CrossRef]

- Raus, M. DECONTAMINATION OF Chlorella Sp. CULTURE USING ANTIBIOTICS AND ANTIFUNGAL COCKTAIL TREATMENT. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2016, 11.

- Lippi, L.; Bähr, L.; Wüstenberg, A.; Wilde, A.; Steuer, R. Exploring the Potential of High-Density Cultivation of Cyanobacteria for the Production of Cyanophycin. Algal Research 2018, 31, 363–366. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 Years of Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, E.; Jacobsen, C. Cultivation of Nannochloropsis Oceanica Using Food Grade Industrial Side Streams: Effect on Growth and Relative Abundance of Selected Amino Acids and Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Journal of Biotechnology 2025, 405, 249–253. [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A RAPID METHOD OF TOTAL LIPID EXTRACTION AND PURIFICATION. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [CrossRef]

- Ljubic, A.; Holdt, S.L.; Jakobsen, J.; Bysted, A.; Jacobsen, C. Fatty Acids, Carotenoids, and Tocopherols from Microalgae: Targeting the Accumulation by Manipulating the Light during Growth. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33, 2783–2793. [CrossRef]

- Bijttebier, S.; D’Hondt, E.; Noten, B.; Hermans, N.; Apers, S.; Voorspoels, S. Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography versus High Performance Liquid Chromatography: Stationary Phase Selectivity for Generic Carotenoid Screening. Journal of Chromatography A 2014, 1332, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Kapishnikov, S.; Kobylynska, M.; Fleck, R.A.; Olsen, M.F.L.; Jensen, P.E.; Fahy, K.; Sheridan, P.; Fyans, W.; O’Reilly, F.; McEnroe, T. Sample Preparation for Correlative Light, Soft X-Ray Tomography, and Cryo FIB-SEM Imaging of Biological Cells. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 129, 19010. [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [CrossRef]

- Hennies, J.; Lleti, J.M.S.; Schieber, N.L.; Templin, R.M.; Steyer, A.M.; Schwab, Y. AMST: Alignment to Median Smoothed Template for Focused Ion Beam Scanning Electron Microscopy Image Stacks. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. International Journal of Computer Vision 2004, 60, 91–110. [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; et al. Ilastik: Interactive Machine Learning for (Bio)Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2019, 16, 1226–1232. [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T.; Acién-Fernández, F.G.; Castellari, M.; Villaró, S.; Bobo, G.; Aguiló-Aguayo, I. Effect of Microalgae Incorporation on the Physicochemical, Nutritional, and Sensorial Properties of an Innovative Broccoli Soup. LWT 2019, 111, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Ao, X.; Ma, L.; Wu, M.; Ma, F. Improving Cell Growth and Lipid Accumulation in Green Microalgae Chlorella Sp. via UV Irradiation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2015, 175, 3507–3518. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.T.; Whittaker, C.; Griffiths, H. The Algal Pyrenoid: Key Unanswered Questions. Journal of Experimental Botany 2017, 68, 3739–3749. [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Crans, V.L.; Jonikas, M.C. The Pyrenoid: The Eukaryotic CO2-Concentrating Organelle. The Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3236–3259. [CrossRef]

- Dall’Osto, L.; Bressan, M.; Bassi, R. Biogenesis of Light Harvesting Proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioener-getics 2015, 1847, 861–871. [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Bellan, A.; Michelberger, T.; Lyska, D.; Wakao, S.; Niyogi, K.K.; Morosinotto, T. Modulation of Xanthophyll Cycle Impacts Biomass Productivity in the Marine Microalga Nannochloropsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2214119120. [CrossRef]

- Latowski, D.; Grzyb, J.; Strzałka, K. The Xanthophyll Cycle - Molecular Mechanism and Physiological Significance. Acta Physiol Plant 2004, 26, 197–212. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Marín, B.; Roach, T.; Verhoeven, A.; García-Plazaola, J.I. Shedding Light on the Dark Side of Xanthophyll Cycles. New Phytologist 2021, 230, 1336–1344. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Nagarajan, D.; Zhang, Q.; Chang, J.-S.; Lee, D.-J. Heterotrophic Cultivation of Microalgae for Pigment Production: A Review. Biotechnology Advances 2018, 36, 54–67. [CrossRef]

- Stadnichuk, I.N.; Rakhimberdieva, M.G.; Bolychevtseva, Y.V.; Yurina, N.P.; Karapetyan, N.V.; Selyakh, I.O. Inhibition by Glucose of Chlorophyll a and Phycocyanobilin Biosynthesis in the Unicellular Red Alga Galdieria Partita at the Stage of Coproporphyrinogen III Formation. Plant Science 1998, 136, 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Beale, S.I. Enzymes of Chlorophyll Biosynthesis. Photosynthesis Research 1999, 60, 43–73. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Bayat, B.; Tayebati, H.; Hashemi, A.; Pajoum Shariati, F. Nitrate and Phosphate Removal from Treated Wastewater by Chlorella vulgaris under Various Light Regimes within Membrane Flat Plate Photobioreactor. Env Prog and Sustain Energy 2021, 40, e13519. [CrossRef]

- Møller, I.M., Jensen, P.E., Hansson, A. Oxidative Modifications to Cellular Components in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007, 58, 459–481. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.F.L.; Pedersen, J.S.; Thomsen, S.T.; Martens, H.J.; Petersen, A.; Jensen, P.E. Outdoor Cultivation of a Novel Isolate of the Microalgae Scenedesmus Sp . and the Evaluation of Its Potential as a Novel Protein Crop. Physiologia Plantarum 2021, 173, 483–494. [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, S.O.; Barbarino, E.; Lavín, P.L.; Lanfer Marquez, U.M.; Aidar, E. Distribution of Intracellular Nitrogen in Marine Microalgae: Calculation of New Nitrogen-to-Protein Conversion Factors. European Journal of Phycology 2004, 39, 17–32. [CrossRef]

- Young, V.R.; El-Khoury, A.E. Human Amino Acid Requirements: A Re-Evaluation. Food Nutr Bull 1996, 17, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Micro-Algae as a Source of Protein. Biotechnology Advances 2007, 25, 207–210. [CrossRef]

- Cecchin, M.; Marcolungo, L.; Rossato, M.; Girolomoni, L.; Cosentino, E.; Cuine, S.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Delledonne, M.; Ballottari, M. Chlorella Vulgaris Genome Assembly and Annotation Reveals the Molecular Basis for Metabolic Acclimation to High Light Conditions. The Plant Journal 2019, 100, 1289–1305. [CrossRef]

- Mujtaba, G.; Choi, W.; Lee, C.-G.; Lee, K. Lipid Production by Chlorella Vulgaris after a Shift from Nutrient-Rich to Nitrogen Starvation Conditions. Bioresource Technology 2012, 123, 279–283. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Visualization of agar plates after UV-mutagenesis. (a) UVC-radiation dose response illustrated by plating treated and untreated C. vulgaris on P4-TES plates with 0.1M glucose incubated in darkness for 4 weeks. From left plates with 1: the negative control with the un-radiated C. vulgaris WT and plate 2: 15 seconds of radiation and 3. after 30 seconds UVC-radiation where all cells died. (b): From a second independent experiment 12 seconds of UVC-radiation was an appropriate UVC dose for obtaining plates with separate colonies including pigment mutants (indicated by yellow arrow). (c) after 25 seconds of radiation only few cells had survived.

Figure 1.

Visualization of agar plates after UV-mutagenesis. (a) UVC-radiation dose response illustrated by plating treated and untreated C. vulgaris on P4-TES plates with 0.1M glucose incubated in darkness for 4 weeks. From left plates with 1: the negative control with the un-radiated C. vulgaris WT and plate 2: 15 seconds of radiation and 3. after 30 seconds UVC-radiation where all cells died. (b): From a second independent experiment 12 seconds of UVC-radiation was an appropriate UVC dose for obtaining plates with separate colonies including pigment mutants (indicated by yellow arrow). (c) after 25 seconds of radiation only few cells had survived.

Figure 2.

Glucose containing agar plates with the 11 isolated mutants. (a) WT and 7 mutants from first radiation trial and (b) mutants from the 2nd radiation trial. The two strains selected for further characterization: M6 and M11 are indicated by an asterisk.

Figure 2.

Glucose containing agar plates with the 11 isolated mutants. (a) WT and 7 mutants from first radiation trial and (b) mutants from the 2nd radiation trial. The two strains selected for further characterization: M6 and M11 are indicated by an asterisk.

Figure 3.

Cell culture flasks after 7 days of cultivation at: phototrophic, mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation setups (biological triplicates). (a-c) Mutant M11: (a) phototropic, (b) mixotrophic and (c) heterotrophic cultivation (d-f) Mutant M6: (d) phototropic, (e) mixotrophic and (f) heterotrophic cultivation (g-i), C. vulgaris WT: (g) phototropic, (h) mixotrophic and (i) heterotrophic cultivation.

Figure 3.

Cell culture flasks after 7 days of cultivation at: phototrophic, mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation setups (biological triplicates). (a-c) Mutant M11: (a) phototropic, (b) mixotrophic and (c) heterotrophic cultivation (d-f) Mutant M6: (d) phototropic, (e) mixotrophic and (f) heterotrophic cultivation (g-i), C. vulgaris WT: (g) phototropic, (h) mixotrophic and (i) heterotrophic cultivation.

Figure 4.

Growth of mutants under photo-, mixo and heterotrophic conditions as measured by OD750 and dry matter content. (a-c): optical density measured at OD750, and (d-f) dry matter content g/L for C. vulgaris (WT) and the two chlorophyll deficient mutants M6 and M11 cultivated both phototrophically (a and d), mixotrophically (b and e), and heterotrophically (c and f). All measurements are made in biological replicates (n=3) after seven days of cultivation. Significant differences are indicated as: * (p>0.05), ** (p>0.01), *** (p>0.005) and ****(p>0.0001).

Figure 4.

Growth of mutants under photo-, mixo and heterotrophic conditions as measured by OD750 and dry matter content. (a-c): optical density measured at OD750, and (d-f) dry matter content g/L for C. vulgaris (WT) and the two chlorophyll deficient mutants M6 and M11 cultivated both phototrophically (a and d), mixotrophically (b and e), and heterotrophically (c and f). All measurements are made in biological replicates (n=3) after seven days of cultivation. Significant differences are indicated as: * (p>0.05), ** (p>0.01), *** (p>0.005) and ****(p>0.0001).

Figure 5.

Light microscopy micrographs of mutant M11, M6 and WT strain after 7 days of cultivation at three trophic modes. (a-c) Mutant M11 cultivated photo- (a), mixo- (b) and heterotrophically (c). (d-f) Mutant M6 cultivated photo- (d), mixo- (e) and heterotrophically (f). (g-i) WT strain cultivated at photo- (g), mixo- (h) and heterotrophic conditions (i). All micrographs are at 1000x magnification, scale bar: 10 µm. Color corrected to reduce yellow background. Original micrographs (

Figure S4, supplemental).

Figure 5.

Light microscopy micrographs of mutant M11, M6 and WT strain after 7 days of cultivation at three trophic modes. (a-c) Mutant M11 cultivated photo- (a), mixo- (b) and heterotrophically (c). (d-f) Mutant M6 cultivated photo- (d), mixo- (e) and heterotrophically (f). (g-i) WT strain cultivated at photo- (g), mixo- (h) and heterotrophic conditions (i). All micrographs are at 1000x magnification, scale bar: 10 µm. Color corrected to reduce yellow background. Original micrographs (

Figure S4, supplemental).

Figure 6.

HPLC chromatograms of pigment extracts of C. vulgaris WT, mutants M6 and M11 cultivated both mixotrophically (a) and heterotrophically (b). M6 did not grow at phototrophic conditions and only data was obtained from WT and M11 (c). All samples are normalized to an OD750 of 10 hence the relative pigment content can be compared for all strains and cultivations. 1: cis-neoaxanthin, 2: all trans-neoaxanthin, 3: violaxanthin, 4: antheraxanthin, 5: lutein, 6: zeaxanthin, 7: chlorophyll b, 8: chlorophyll a, IS: internal standard (8-apocarotenal).

Figure 6.

HPLC chromatograms of pigment extracts of C. vulgaris WT, mutants M6 and M11 cultivated both mixotrophically (a) and heterotrophically (b). M6 did not grow at phototrophic conditions and only data was obtained from WT and M11 (c). All samples are normalized to an OD750 of 10 hence the relative pigment content can be compared for all strains and cultivations. 1: cis-neoaxanthin, 2: all trans-neoaxanthin, 3: violaxanthin, 4: antheraxanthin, 5: lutein, 6: zeaxanthin, 7: chlorophyll b, 8: chlorophyll a, IS: internal standard (8-apocarotenal).

Figure 7.

The total content of amino acids and sum of essential of amino acids (excluding tryptophane and cysteine) measured for C. vulgaris WT, and two chlorophyll deficient mutants M6 and M11. (a) Total content of amino acids (AA), and (c) sum of essential amino acids (EAA) in % of AA at mixotrophic cultivation. The same parameters measured at heterotrophic cultivation: (b) sum of AA and (d) content of EAA. All measurements are conducted for biological replicates (n=3). Significant differences are indicated by *: (p>0.05) and **: (p>0.01).

Figure 7.

The total content of amino acids and sum of essential of amino acids (excluding tryptophane and cysteine) measured for C. vulgaris WT, and two chlorophyll deficient mutants M6 and M11. (a) Total content of amino acids (AA), and (c) sum of essential amino acids (EAA) in % of AA at mixotrophic cultivation. The same parameters measured at heterotrophic cultivation: (b) sum of AA and (d) content of EAA. All measurements are conducted for biological replicates (n=3). Significant differences are indicated by *: (p>0.05) and **: (p>0.01).

Figure 8.

Lipid content in the C. vulgaris WT and two mutants M6 and M11 biomass. Due to an insufficient amount of biomass only a single lipid measurement was obtained for each sample, hence the results should only be regarded as indicative. M: mixotrophic, H: heterotrophic cultivation.

Figure 8.

Lipid content in the C. vulgaris WT and two mutants M6 and M11 biomass. Due to an insufficient amount of biomass only a single lipid measurement was obtained for each sample, hence the results should only be regarded as indicative. M: mixotrophic, H: heterotrophic cultivation.

Figure 11.

Quantification of total volume of lipid droplets as volume normalized per cell determined by cryo FIB-SEM. n=65-86 lipid bodies.

Figure 11.

Quantification of total volume of lipid droplets as volume normalized per cell determined by cryo FIB-SEM. n=65-86 lipid bodies.

Table 1.

Overview of the visual phenotypes of the 12 mutants selected from the two UVC-radiation trials.

Table 1.

Overview of the visual phenotypes of the 12 mutants selected from the two UVC-radiation trials.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).