1. Introduction

1.1. Plateaued Therapies and the Need for Mechanistic Innovation in Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Ischemia

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality and continues to impose a substantial clinical and economic burden despite advances in medical and interventional therapy [

7,

17,

23]. According to the World Health Organization, cardiovascular diseases accounted for approximately 19.8 million deaths worldwide in 2022, representing 32% of all global deaths, with 85% attributable to ischemic heart disease and stroke [

24]. While established treatments such as β-blockers, renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, statins, and contemporary revascularization strategies have improved survival, substantial residual risk persists, and long-term functional recovery remains incomplete for many patients [

7,

8,

17]. The WHO reports that cardiovascular disease accounts for at least 38% of premature deaths (<70 years) due to noncommunicable diseases [

24]. This persistent global burden has driven increasing interest in regenerative and biologically targeted strategies aimed at augmenting endogenous repair mechanisms rather than focusing solely on acute ischemic injury prevention. Strategies focused primarily on acute ischemic injury, such as revascularization, thrombolysis, and early infarct limitation, do not adequately address downstream processes including mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, maladaptive remodeling, impaired angiogenesis, dysregulated autophagy, and loss of cardiomyocyte functional reserve [

7,

16,

21].

Contemporary cardiovascular research continues to deepen its focus on intracellular survival and repair pathways that govern cardiomyocyte fate following ischemic injury such as the ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling networks [

11,

17,

22]. In parallel, non-pharmacologic and regenerative approaches such as structured physical activity and mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) based therapies have demonstrated promising avenues to address the therapeutic plateau observed with conventional interventions [

7,

16,

21]. The field has shifted beyond descriptive assessments of exercise and cell therapy and instead emphasizes exploiting the mechanistic convergence of paracrine and exosome-mediated signaling in integrative cardioprotection [

16,

17]. In this framework, MSC–derived exosomes are recognized as principal mediators of therapeutic effect, delivering defined molecular cargo that activates pro-survival and reparative signaling pathways and whose efficacy can be enhanced through targeted engineering and delivery strategies [

19].

Isoproterenol (ISO) induced myocardial ischemia is a widely used experimental model that reproduces key features of ischemic cardiac injury, including β-adrenergic overstimulation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cardiomyocyte necrosis [

11,

17]. Within this context, endogenous survival pathways are activated in response to injury but are often insufficient to prevent adverse remodeling and functional decline, making the model well suited for interrogating targeted cardioprotective strategies [

11,

18].

1.2. Molecular Pathophysiology of ISO-Induced Myocardial Injury and Survival Pathways

ISO is a synthetic β-adrenergic agonist that induces myocardial injury through sustained catecholaminergic stimulation, resulting in calcium overload, excessive reactive oxygen species production, mitochondrial impairment, and cardiomyocyte death [

11,

17]. These mechanisms recapitulate key neurohumoral and oxidative components of human ischemic heart disease, and support the translational relevance of the ISO model for mechanistic studies [

17,

18].

In ISO-induced injury, cardiomyocytes experience increased metabolic demand, impaired ATP generation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of stress-responsive signaling cascades [

11,

22]. In response, intracellular survival pathways—including ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR—are engaged in an attempt to restore cellular homeostasis and limit injury progression [

11,

17,

22]. Autophagy represents a central component of this adaptive response, as regulated removal of damaged proteins and organelles is essential for maintaining cardiomyocyte viability under ischemic stress [

17,

22]. However, dysregulation of autophagy can exacerbate injury, highlighting the importance of precise temporal and quantitative control of these pathways [

22].

1.3. Exercise-Induced Intracellular Signaling in Cardioprotection Against ISO Injury

Exercise promotes physiological cardiac remodeling and enhances resistance to ischemic stress through coordinated metabolic and signaling adaptations [

7,

16,

21]. Exercise-induced cardioprotection involves modulation of intracellular survival pathways that overlap with those activated during ischemic injury, including adaptations in mitochondrial metabolism, redox homeostasis, and intracellular signaling pathways, including ERK, PI3K/Akt, AMPK, and regulated autophagy [

17,

22].

These adaptations improve mitochondrial efficiency, redox balance, and cellular stress tolerance to prime cardiomyocytes to better withstand subsequent ischemic insults such as those induced by ISO [

17,

21]. Importantly, exercise-associated signaling favors regulated autophagic flux and cytoprotective remodeling through modulation of energy- and stress-sensitive pathways, including AMPK activation, balanced mTOR signaling, and ERK- and Akt-dependent survival signaling. These adaptations preserve mitochondrial quality and limit excess reactive oxygen species(ROS) generation. They also attenuate secondary inflammatory and profibrotic stimuli, such as sustained oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, platelet–leukocyte crosstalk, thrombin- and fibrin-mediated activation, cytokine release, and chemokine-driven leukocyte recruitment, thereby biasing post-ischemic remodeling toward adaptive hypertrophy rather than fibrosis [

16,

21].

1.4. Cardioprotective Mechanisms of Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes in Ischemic Myocardium

MSC-based therapies represent an established area of investigation in regenerative cardiovascular research, with multiple clinical and preclinical studies demonstrating functional improvement and attenuation of adverse remodeling following ischemic injury [

1,

2,

7,

17]. Mechanistic analyses attribute these effects to paracrine signaling, with particular emphasis on MSC-derived exosomes as cell-free mediators capable of delivering bioactive proteins, lipids, and regulatory RNAs to injured myocardium [

16,

19,

20].

In ischemic settings, MSC-derived exosomes have been shown to enhance angiogenesis, support mitochondrial function, activate pro-survival signaling pathways, and reduce apoptosis and fibrosis [

17,

19,

20]. These effects are mediated in part through modulation of ERK and Akt/mTOR signaling, pathways that are also implicated in exercise-induced cardioprotection [

17,

22]. Advanced delivery strategies, including ultrasound-triggered and biomimetic nanoparticle-based systems, further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of exosome-mediated repair [

19,

20].

The combination of exercise-induced and MSC exosome-mediated signaling provides a mechanistic rationale for integrative cardioprotective strategies. Exercise enhances endogenous stress resilience and metabolic adaptation, while MSC-derived exosomes reinforce pro-survival and reparative signaling within the ischemic myocardium [

16,

17,

21]. Coordinated modulation of these pathways may amplify beneficial autophagy, limit maladaptive remodeling, and promote more effective structural and functional recovery following myocardial ischemia.

2. Methods

This study was designed as a focused narrative review, given the heterogeneity of experimental models, variability in exercise paradigms, and evolving understanding of paracrine and exosome-mediated mechanisms underlying cardioprotection in ischemic heart disease. The review aimed to synthesize mechanistic and translational evidence examining the convergence of exercise-induced signaling and mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)–derived exosome pathways in the context of isoproterenol-induced myocardial ischemia, with particular emphasis on ERK and Akt/mTOR signaling networks.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify relevant experimental, preclinical, and clinical studies. Electronic searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science were performed for articles published between January 2000 and September 2025. Additional relevant publications were identified through manual review of reference lists from selected review articles, randomized clinical trials, and foundational mechanistic studies.

Search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “ischemic heart disease,” “myocardial ischemia,” “isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury,” “β-adrenergic overstimulation,” “exercise cardioprotection,” “exercise preconditioning,” “mesenchymal stem cells,” “MSC-derived exosomes,” “extracellular vesicles,” “paracrine signaling,” “ERK signaling,” “PI3K/Akt signaling,” “mTOR signaling,” “AMPK,” “autophagy,” “mitochondrial dysfunction,” “oxidative stress,” “cardiac remodeling”, “Intravenous”, “intracoronary”, “intrapericardial”, “Intramyocardial”, “myocardium”, “heart”, “bubble”, “nanoparticle”, “multipotent”, pluripotent”, and “senescence” Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR”) were applied to refine search results.

Peer-reviewed original research articles, randomized and non-randomized clinical studies, animal models, experimental mechanistic studies, and narrative or translational reviews were eligible for inclusion if they addressed at least one of the following domains: exercise-induced cardioprotective signaling, MSC- or exosome-mediated paracrine effects, isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury, or ERK/Akt/mTOR pathway modulation in ischemic contexts. Studies focusing exclusively on non-cardiac systems, unrelated disease models, or lacking mechanistic relevance were excluded.

Article screening and selection were performed by the authors based on relevance to the study objective. When questions regarding eligibility arose, inclusion was determined by consensus discussion. Given the narrative and mechanistic nature of the review, no formal risk-of-bias assessment or quantitative meta-analysis was undertaken.

The included literature was synthesized thematically to contextualize current understanding of cardioprotection according to metabolic adaptation, paracrine and exosome-mediated signaling, intracellular survival pathways, and structural remodeling outcomes following ischemic stress.

3. Stem Cell Source Considerations for Exosome-Based Therapy in Cardiac Ischemia

3.1. Pluripotent vs. Multipotent Stem Cells

Pluripotent stem cells (PSC) are cells that are capable of generating tissue from the three germ layers. These cells may become nearly any somatic cell type in the body. Pluripotent stem cells can be directed into lineage-restricted progenitors and differentiated cell types, including multipotent stem cell populations. Multipotent stem cells are restricted to a narrower range of related cell types within a lineage, and their differentiation potential is limited compared with pluripotent stem cells [

16]. Unlike pluripotent stem cells, their differentiation potential is limited to a restricted lineage range [

16]. Mesenchymal stem cells are commonly studied stem cells in cardiac and connective tissue research. These cells include bone marrow-derived stem cells and adipose-derived stem cells [

17].

3.2. Advantages and Limitations of Adipose versus Bone Marrow-Derived MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are adult stem cells that can differentiate into mesodermal lineages, such as bone, cartilage, muscle and adipose. They are not thought to primarily become cardiomyocytes, but instead act largely through paracrine signaling, releasing exosomes and other soluble factors that support cardiomyocyte survival, promote angiogenesis, recruit endogenous stem/progenitor cells, and reduce apoptosis in injured myocardium. Use of MSCs requires isolation of the cells, then the successful delivery of the cells to their target location. Bone marrow stem cells were historically the initial site of isolation for mesenchymal stem cells, but harvesting the stem cells required an invasive procedure [

16]. The isolated yield is relatively low, so adipose-derived stem cells (AD-MSCs) are increasingly preferred because they offer higher yield and less invasive isolation [

9].

AD-MSCs have a higher yield with the added benefit of a less invasive procedure and multiple sites of extraction. Stem cells have differences in their morphology, surface marker expression, and differentiation potentials, but AD-MSCs are structurally and characteristically similar to bone marrow-derived cells with the added benefit of a higher proliferative capacity [

9]. Despite the greater proliferative capacity, senescence is still a limiting factor in treatment with AD-MSCs. The issue may be pronounced in ischemic myocardium, where excessive branched-chain amino acid accumulation can impair MSC therapeutic efficacy [

22]. The loss of H3K9me3, a histone modification mark that maintains heterochromatin, also accelerates senescence [

22].

4. Methods of Delivery

Successful therapeutic signaling from MSC-based approaches, including cell-derived exosomes and other soluble factors, depends both on the type of cell product used and the method of delivery to the tissue [

8]. Poor engraftment has served as a barrier to therapeutic usability due to untargeted delivery and low cell retention at injury sites. Many methods of delivery have been created to bring the administered cells to their targeted tissue. These methods of delivery come with their benefits and limitations [

13].

4.1. Intramycocardial Injection Approaches

Intramyocardial injection involves directly injecting stem cells into the damaged myocardium [

12]. This modality is currently being tested on human subjects. The benefits of this method are the direct targeted infusions of a large amount of cells. Issues with this method can involve mechanical damage to the tissue, difficulty identifying infarcted tissue during the procedure, and challenges with electromechanical integration with the host myocardium post-injection. Higher incidences of arrhythmias have been reported in some intramyocardial injection studies depending on the cell product used. Two main routes are currently used, the transendocardial and the epicardial injection [

10,

21].

The transendocardial route uses catheter-based, image-guided injections directly into the endocardial surface enabling precise access to the borderzone myocardium without requiring open chest surgery. It is performed percutaneously through peripheral vessels such as the femoral artery or vein. The catheter is guided to the infarct zone using a fluoroscopic 2D or 3D system. The 3D system may provide a more even distribution of cells around the zone of injury. It should be noted that while the research is still in a preliminary stage and consistent results have not yet been found, some of the benefits already seen from this are improved perfusion, increased ejection fraction, improved diastolic function and left ventricular function, improved 6 minute walk scores, and improved Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire scores [

21].

The epicardial route provides direct visual access to the infarcted myocardium during surgery. It involves using a 27 gauge-bent needle to inject the infarcted myocardium. This method is more invasive, and is typically done during a left thoracotomy or sternotomy as an adjunct treatment during an open heart surgery. Risks for this treatment include leakage, difficulty controlling precise dosages, and the inadequate retention of donor cells. This approach avoids direct intracoronary infusion related embolization risk. Studies are predominantly preclinical [

21].

4.2. Intrapericardial Catheter-Based Delivery

The intrapericardial route aims to provide therapeutic delivery to myocardium that is minimally invasive but allows high retention of viable stem cells while minimizing potential damage to the myocardium [

10]. Using a hydrogel compound with mesenchymal stem cells, an intrapericardial injection was done in mice that recently suffered a myocardial infarction. An intramyocardial injection group was done as a control. The procedure showed that the intrapericardial group retained about 10 times as many viable stem cells. IPC-delivered MSCs showed increased exosome secretion and reduced myocardial apoptosis when compared with intramyocardial injection. A porcine feasibility and safety assessment of IPC-mesenchymal stem cells was conducted. No abnormal cardiac events were found in the pigs during short-term monitoring, however the follow-up period was only 4 days, so long-term effects could not be assessed [

14].

4.3. Intracoronary

The intracoronary route delivers stem cells into the infarct-related coronary artery during catheterization, typically as a divided infusion through a coronary catheter to promote downstream distribution within the infarct territory [

1]. The BMJ issued an Expression of Concern and opened a content-integrity investigation citing data-integrity and disclosure or authorship concerns, and cautioned that the results may not be reliable [

15]. In a randomized post-AMI trial using intracoronary Wharton’s jelly MSC infusion, improvements in LVEF at 6 months were reported compared with conventional care, with a larger improvement observed when a booster infusion was given, and no procedure-related arrhythmias or coronary flow compromise were reported. These functional gains are commonly interpreted as being mediated primarily by paracrine signaling rather than durable cardiomyocyte engraftment [

1,

7]. In the TAHA8 trial, procedural blinding was limited and participants older than 65 years were excluded, which may increase risk of bias and limit generalizability [

2]. Animal studies have also shown a possibility of microvascular obstruction and myocardial injury. Despite these limitations, intracoronary delivery remains clinically relevant because it can be performed during standard catheterization workflows and provides targeted delivery to the infarct-related coronary circulation compared with systemic infusion [

1,

2].

4.4. Intravenous

The intravenous route may promote systemic signaling that contributes to cardiac recovery and can be administered as a minimally invasive delivery route. The injection can be administered via peripheral IV access. This route has shown improved left ventricular function and reduced fibrosis in rats. This route can be administered as repeated intravenous infusions in preclinical models, with functional measures improving after dosing, suggesting a potential cumulative benefit over time. This route has minimal cardiac homing, often only seeing a few cells in the target location [

18].

5. Advancements

5.1. Stem-Cell Senescence

Though AD-MSCs are still widely used for stem cell research, current preclinical research is exploring induced mesenchymal stem cells. Induced mesenchymal stem cells (iMSCs) are generated by reprogramming somatic cells into iPSCs, then differentiating them into mesenchymal stem cell–like cells. iMSC derivation from iPSCs can enable greater expansion capacity and mitigate donor-limited proliferation and senescence seen in primary MSC preparations. Five methods of acquiring these cells are embryoid body formation, specific differentiation, blood-based method, MSC switch method, and pathway inhibitor method. Each method has advantages and drawbacks [

4].

Embryoid body formation uses 3D aggregates of pluripotent stem cells (including iPSCs) that undergo spontaneous differentiation [

3]. This method is simple and cost-effective, but there may be difficulty obtaining homogeneity in body size and shape, scaling up embryoid body production and obtaining total control over the microenvironment of embryoid bodies [

4,

5].

The specific differentiation approach involves pre-differentiation of iPSCs into a particular lineage, then growing stem cells using growth factors to differentiate them into iMSCs [

6]. Cells generated via this method are more time- and resource-intensive to produce, and some reports suggest lineage-directed differentiation may yield iMSCs with enhanced regenerative properties [

4,

5,

6].

The blood-based method uses a culture containing blood-based supplements, such as human platelet lysate, to make iMSCs. This is another low-cost method that has high proliferative potential, but may trigger immune reactions due to possible failures in removing cell fragments such as platelets [

4].

The MSC switch method uses changing the iPSC culture medium with MSC growth media to cause differentiation into iMSCs. One such medium is DMEM/MEM/IMDM supplemented with FBS, bFGF, TGF- β1, insulin, transferrin, penicillin, phenol red, and serum. Producing the iMSC using this method is described as easy, and with the use of FACS, one is able to select a particular subpopulation to yield consistent results. Challenges when using this method are the variability in signaling potency, regulatory status, and their paracrine composition [

4,

6].

The pathway inhibitor technique uses chemical inhibitors of certain pathways to facilitate differentiation of iPSCs into iMSCs. Use of this approach is laborious and may present issues of obtaining large quantities of usable cells, but this method provides a mechanism to reduce heterogeneity among the cells [

4,

5,

6].

5.2. Bubble Technology

Ultrasound-targeted bubble destruction has been investigated as a noninvasive delivery modality in preclinical models [

11,

19]. These genes were used to enhance MSC homing to cardiac tissue [

11]. Using the bubbles, cargo such as shFOXO4 and SDF1 may be delivered to the myocardium via intravenous injection [

11]. In these two preclinical studies, bubble carriers were implemented as microbubbles, which carry gene cargo, and nanobubbles which carry exosome cargo [

11,

19].

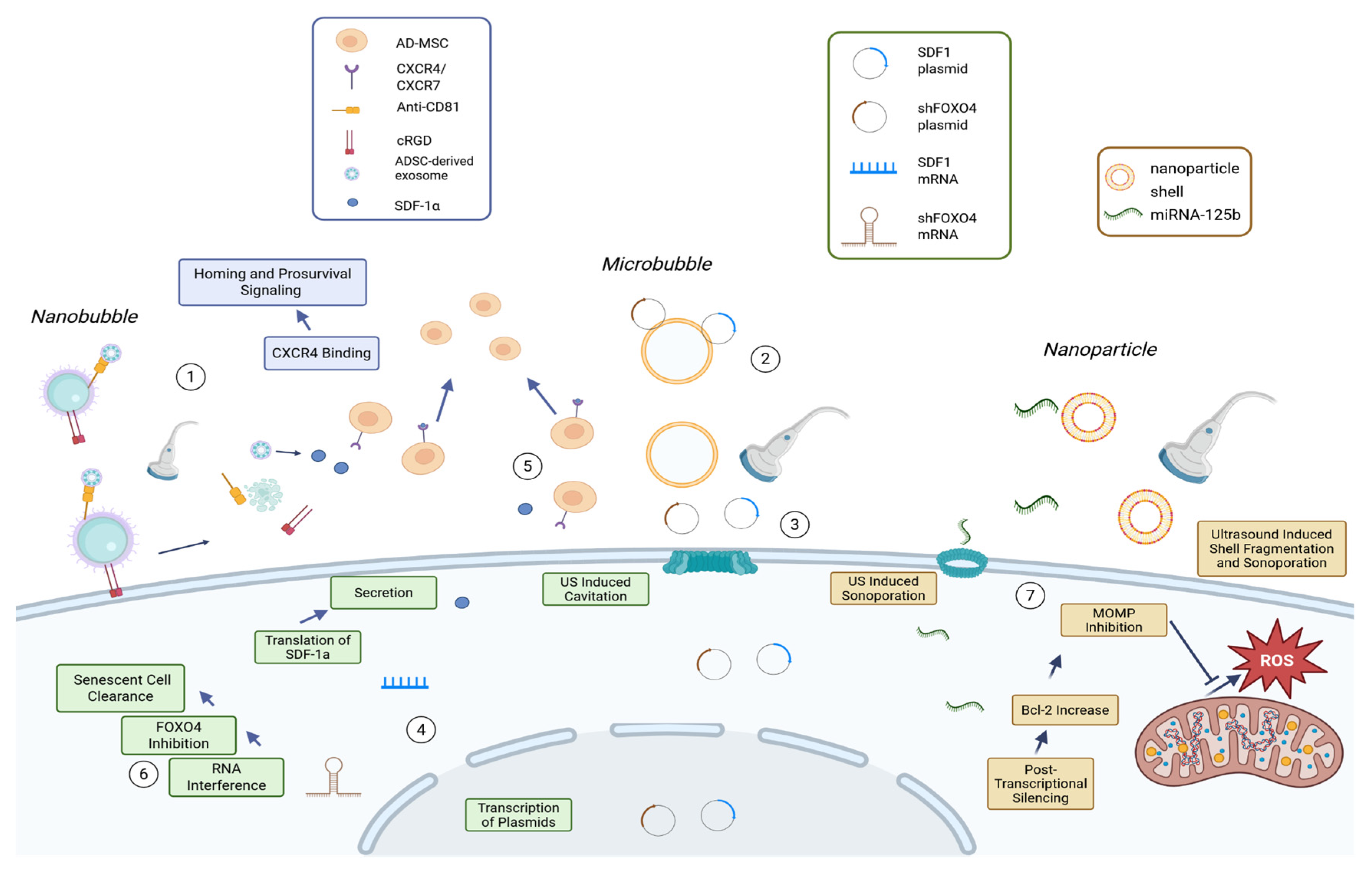

Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the three ultrasound-enabled delivery platforms discussed below, linking each carrier (microbubble, nanobubble, phase-change nanoparticle) to its therapeutic payload and the proposed downstream biologic effect.

Microbubbles are lipid-membrane, gas-core cationic bubbles that can be used to carry plasmid genes. The microbubbles can be destroyed via cavitation triggered by an ultrasound. shFOXO4 knockdown plus SDF1 overexpression was used as a rejuvenation pretreatment to reduce senescence and enhance SDF1-mediated chemotactic recruitment of MSCs to the aging heart. This dual-gene strategy was associated with improved cardiac repair outcomes relative to single-gene treatment. Benefits of gene preconditioning may improve MSC homing efficiency, reduce senescence, lower inflammation, enhance angiogenesis, and reduce infarct relative to the aged heart. While not observed in studied specimens, researchers theorize a systemic toxicity from microbubbles and embolism may develop as a part of therapy. Because gene expression is transient after delivery, durability is limited, and treatment may require optimized dosing schedules for efficient therapy [

11].

Nanobubbles are lipid-shelled, gas-core bubbles that are smaller than microbubbles. Nanobubbles can carry MSC-derived exosomes to the myocardium intravenously through a nanobubble-antibody-exosome complex. The nanobubble is first made using a biotinylated lipid shell. Streptavidin is then incubated with the nanobubble to allow for additional binding. An anti-CD81 antibody will bind to streptavidin forming the targeted nanobubbles. MSC exosomes were incubated to bind the bubbles and the bubbles were delivered intravenously. A low-intensity pulsed ultrasound is then used to disrupt nanobubbles and enhance local exosome release and uptake. This method was designed to improve myocardial retention and uptake of exosomes versus the controls. It addresses a specific issue with the intravenous delivery of exosomes, where exosomes may accumulate in non-cardiac organs. No toxicity was observed on organ histology with supportive routine blood and biochemical testing; however, the absence of detected adverse effects should be interpreted within the scope of the assays performed and the study’s preclinical assessment window. Because administration is intravenous, off-target biodistribution remains a plausible residual limitation for exosome-based therapeutics, even when the delivery platform is designed to increase myocardial retention and uptake [

19].

5.3. NanoParticles

Phase-change nanoparticles can be engineered as MSC-membrane–coated carriers that deliver therapeutic cargo such as miRNA-125b to injured myocardium and thereby augment downstream repair pathways relevant to stem cell–based cardiac regeneration. These particles consist of a perfluorocarbon phase-change core and MSC and macrophage dual membrane coating. miRNA-125b is attached to the nanoparticle surface via charge adsorption, this is the cargo that provides the therapeutic effect to the area of the heart. miRNA-125b is shown to be secreted by MSCs. It has many potential benefits on the myocardium, including the downregulation of apoptosis related proteins and inhibiting fibroblast proliferation. The nanoparticles are injected intravenously. The miR-125b has a short active duration, meaning repeated doses will be required [

20].

Table 1.

Summary of Interventions.

Table 1.

Summary of Interventions.

| Intervention |

Mechanism/ Procedure |

Benefit |

Drawback |

Citation |

| Intramyocardial injection |

Direct injection of stem cells into damaged myocardium |

Direct targeted infusion of a large number of cells |

Mechanical tissue damage; difficult infarct localization; higher arrhythmia incidence; suboptimal electromechanical coupling post-injection |

Yuce, 2024 |

| Transendocardial intramyocardial injection |

Percutaneous catheter-based, image-guided injections into endocardial surface targeting borderzone myocardium |

Precise border zone access without open chest surgery; reported improvements in perfusion, EF, diastolic/LV function, and 6-minute walk metrics in preliminary work |

Preliminary stage with inconsistent results |

Yuce, 2024 |

| Epicardial intramyocardial injection |

Surgical direct-visual injection into infarcted myocardium, typically adjunct during open-heart surgery |

Direct visual access; described as not having coronary embolism risk |

More invasive; leakage; dosing control challenges; inadequate donor-cell retention; studies limited to animals |

Yuce, 2024 |

| Intrapericardial injection |

Intrapericardial delivery of hydrogel compound containing MSCs; compared vs intramyocardial control; porcine feasibility/safety reported |

~10× higher viable cell retention vs intramyocardial in mice;increased exosome secretion and reduced myocardial apoptosis; no major adverse effects in mice; no abnormal cardiac events in pigs over 4 days |

Follow-up in pigs only 4 days, so long-term effects not assessed |

Li et al., 2022 |

| Intracoronary infusion |

Catheter-based delivery into infarct-related artery by inflating the catheter and infusing cells during inflation; used during catheterization |

Human trials described with EF increases, reduced scarred myocardium, and lack of arrhythmia post-procedure |

Long-term effects not established; procedural blinding was limited; >65 excluded; concern raised about potential bias in reporting/editorial handling; animal data suggest possible microvascular obstruction and myocardial injury |

Heldman et al., 2008; Attar et al., 2023; Attar et al., 2025; Maxwell, 2025 |

| Embryoid body formation |

Generate iPSC aggregates to drive spontaneous lineage commitment, then isolate MSC-like cells |

Simple; cost-effective |

Heterogeneity; scale-up challenges; limited microenvironment control |

Barzegari et al., 2020; Dupuis and Oltra, 2021 |

| Specific differentiation |

Predifferentiate iPSCs toward a lineage, then apply factors/conditions to yield iMSCs |

Greater regenerative potential |

More time-consuming; higher cost |

Dias et al., 2023; Dupuis and Oltra, 2021 |

| Blood-based method |

Culture iPSCs under blood-derived supplement conditions to promote iMSC phenotype |

Low-cost; high proliferative potential |

Potential immune reactivity if residual blood components/cell fragments persist |

Dupuis and Oltra, 2021 |

| MSC switch method |

Switch iPSC medium to MSC growth media; optional FACS to select subpopulations |

Operationally straightforward; selection can improve consistency |

Variability in signaling potency and paracrine profile; regulatory |

Dupuis and Oltra, 2021; Dias et al., 2023 |

| Pathway inhibitor method |

Use chemical pathway inhibitors to drive iPSC to iMSC differentiation |

Can reduce heterogeneity via controlled signaling |

Labor-intensive; scale-up/yield limitations |

Dupuis and Oltra, 2021; Dias et al., 2023 |

| UTMD microbubble gene delivery |

IV gene-loaded cationic microbubbles; ultrasound cavitation destroys bubbles to deliver genes |

Enhances MSC homing; improved repair outcomes vs single-gene |

Theoretical toxicity/embolism; transient gene expression |

Jiang et al., 2025 |

| Targeted nanobubble–exosome delivery |

IV nanobubble–antibody–exosome complex; LIPUS disrupts nanobubbles to drive exosome release/penetration |

Improves myocardial retention/uptake vs controls; reduces non-cardiac sequestration |

Preclinical window and assays limit safety claims; off-target biodistribution remains plausible |

Wang et al., 2025[19] |

| Dual-membrane phase-change nanoparticles |

IV phase-change nanoparticles with MSC + macrophage membranes; miRNA-125b surface-adsorbed |

Anti-apoptotic and anti-fibrotic effect |

Short miRNA activity; repeat dosing |

Wang et al., 2025[20] |

6. Discussion

6.1. Integrative Model for Combining Exercise and MSC-Exosome Therapy in Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Ischemia

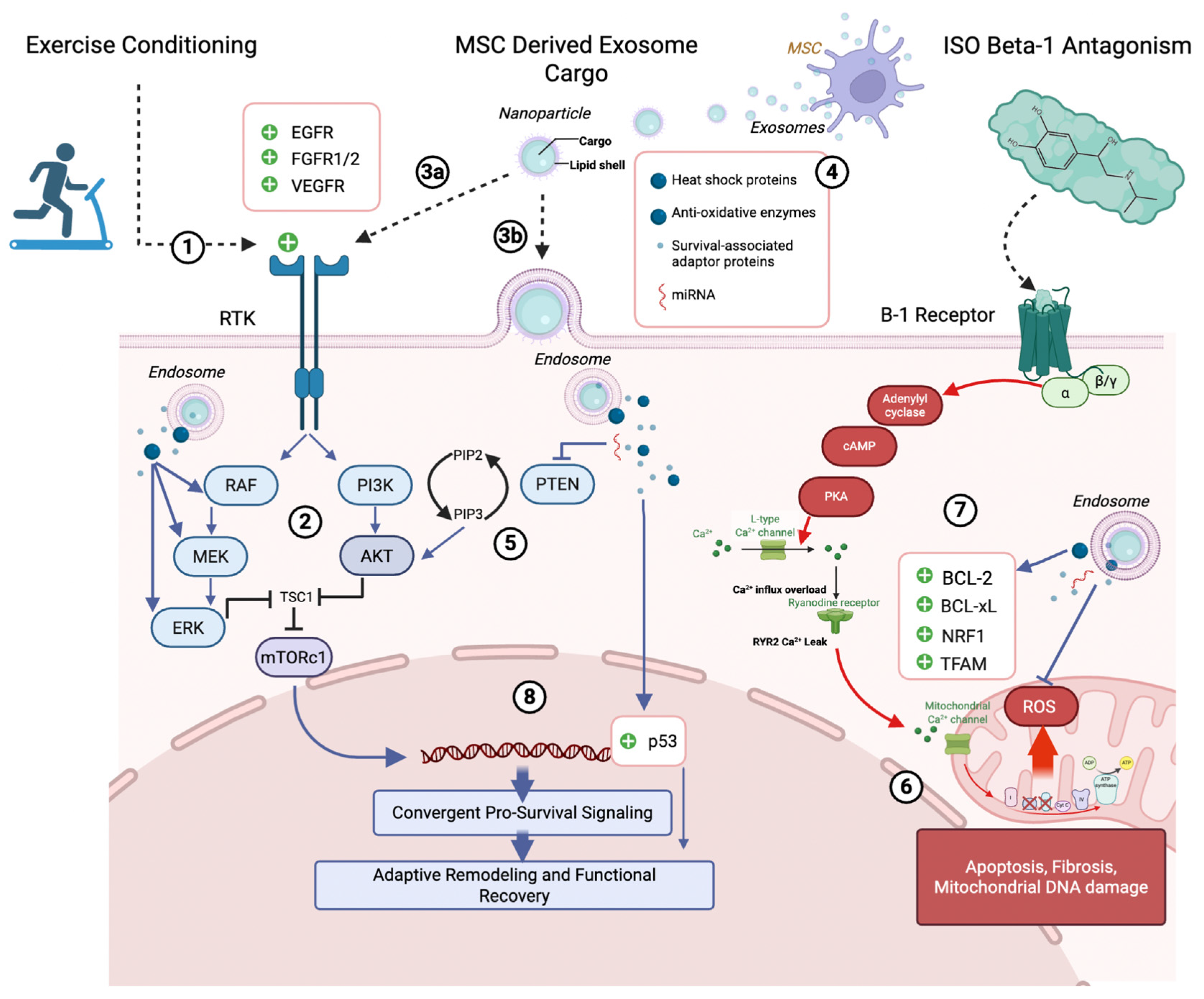

The model proposed in this study conceptualizes cardioprotection as a coordinated biological process in which exercise and MSC–derived exosome signaling act in concert to reinforce cardiomyocyte survival and bias post-injury remodeling toward adaptive outcomes in ISO–induced myocardial ischemia (

Figure 2). Exercise and regenerative therapies are not independent interventions, but biologically synergistic processes that share intracellular kinase networks and mitochondrial regulatory nodes [

3,

7,

11,

17].

Exercise enhances baseline responsiveness of the RAF–MEK–ERK and PI3K–Akt–mTOR pathways, which collectively regulate cytoprotection, metabolic flexibility, and autophagic homeostasis [

3,

7,

17]. Although these adaptations do not prevent myocardial injury under conditions of sustained β-adrenergic overstimulation, they shift cardiomyocytes toward a state of increased stress tolerance and signaling plasticity. When these pathways are engaged, they promote cardiomyocyte survival, preserve mitochondrial integrity through regulated quality control mechanisms, and limit excessive extracellular matrix deposition. These effects support maintenance of ventricular structure and contractile function following ISO-induced myocardial injury [

7,

11,

17].

6.2. Current Clinical, Translational, and Preclinical Evidence for MSC-Based Cardiac Regeneration

The current literature spans randomized controlled trials, translational human investigations, preclinical animal studies, experimental delivery platforms, and narrative syntheses [

16,

17,

21]. Two randomized controlled trials have evaluated intracoronary MSC therapy in the setting of acute myocardial infarction [

1,

2]. These trials demonstrate procedural feasibility and acceptable safety profiles, with modest signals of improvement in functional outcomes and attenuation of adverse ventricular remodeling in selected patient populations [

1,

2]. However, the magnitude and consistency of observed benefit remain variable, which highlights persistent challenges related to patient selection, dosing, delivery route, and endpoint sensitivity [

1,

2,

12,

15]. These trials do not provide definitive evidence of durable structural myocardial regeneration, which reinforces the need for mechanistic refinement [

15,

28].

Beyond randomized trials, the literature contains multiple non-randomized human translational and clinical analyses that focus on delivery feasibility, retention efficiency, and comparative administration routes [

8,

10,

12,

13]. They find that therapeutic efficacy is constrained less by cellular viability and more by biological engagement within the injured myocardial environment [

12,

13,

17]. The research emphasizes limited cell retention, heterogeneous tissue integration, and variable paracrine signaling as major determinants of outcome [

12,

13]. As such, these investigations provide context for understanding why clinical efficacy has remained inconsistent despite encouraging safety profiles [

12,

17].

In contrast, preclinical animal studies constitute a substantial and mechanistically informative segment of the literature [

11,

17,

18]. Multiple ischemic and ischemia–reperfusion models state that experimental interventions consistently demonstrate improvements in ventricular function, attenuation of adverse remodeling, enhanced angiogenesis, and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis [

11,

17,

18]. These effects are reproducibly associated with activation of intracellular survival pathways, modulation of metabolic stress responses, and improved mitochondrial integrity [

11,

17]. Importantly, several animal studies explicitly demonstrate that therapeutic benefit is mediated predominantly through paracrine mechanisms rather than durable engraftment, providing biological plausibility for cell-free strategies [

16,

17,

21].

In parallel, experimental and bioengineering studies have focused on optimizing therapeutic delivery and signal potency [

14,

19,

20]. Engineered exosome platforms, ultrasound-triggered targeting systems, biomimetic nanoparticles, and hydrogel-based retention strategies consistently enhance tissue targeting, prolong biological activity, and amplify downstream signaling effects in preclinical models [

14,

19,

20]. Historically, intracellular delivery of therapeutic vesicles and nanoparticles has relied predominantly on endocytosis, whereby extracellular cargo is internalized into early endosomes and subsequently trafficked through late endosomal and lysosomal compartments before potential cytosolic release [

19]. While this pathway enables cellular uptake, it introduces inherent biological limitations, including delayed intracellular availability, enzymatic degradation, and signal attenuation due to vesicular sequestration, which can substantially reduce effective payload bioactivity despite successful internalization [

19]. As a result, a significant proportion of delivered proteins, RNAs, and signaling molecules may become degraded or mislocalized before engaging their intended intracellular targets [

19]. Preclinical myocardial infarction models demonstrate that ultrasound-triggered exosome and nanoparticle delivery enhances myocardial accumulation, accelerates intracellular signaling activation, and improves functional recovery compared with delivery strategies that rely primarily on endocytosis [

19,

20]. These studies directly address limitations identified in clinical trials and provide mechanistic justification for transitioning from bulk cell delivery toward precision-guided, paracrine-focused interventions [

12,

17].

The narrative and mechanistic review literature, which represents the largest component of the current body of work finds that MSC-based therapies exert their effects primarily through secreted factors, including extracellular vesicles and exosomes, which modulate cardiomyocyte survival, angiogenesis, inflammatory signaling, and remodeling dynamics [

16,

17,

21]. These also include editorial and commentary perspectives that critically assess the reproducibility and clinical significance of intracoronary cell therapy trials [

15,

28]. Rather than undermining the field, these critiques reinforce the necessity of mechanistic clarity, rigorous delivery optimization, and biologically informed trial design [

15,

28].

The current body of literature supports several key conclusions [

16,

17,

21]. First, regenerative therapies in ischemic heart disease are safe and biologically active but exhibit heterogeneous clinical efficacy [

1,

2,

12,

15]. Second, preclinical and experimental evidence strongly implicates paracrine and exosome-mediated signaling as the main drivers of observed benefit [

11,

16,

17,

19].

Third, delivery efficiency and biological engagement remain dominant barriers to translation [

12,

13,

17]. Finally, the convergence of mechanistic insights from exercise biology, MSC signaling, and engineered paracrine platforms provides a rational framework for integrative cardioprotective strategies that might go beyond acute ischemic injury mitigation [

7,

17,

19,

20].

6.3. Safety and Limitations

MSC–based and paracrine-focused regenerative strategies demonstrate a favorable short-term safety profile in both clinical and preclinical settings [

1,

2,

12,

17]. Randomized clinical trials evaluating intracoronary MSC administration after acute myocardial infarction consistently report acceptable procedural safety, with low rates of serious adverse events attributable to the intervention itself [

1,

2]. Similarly, translational human studies and delivery-focused investigations do not identify excess arrhythmic risk, microvascular obstruction, or clinically significant immune reactions when contemporary dosing and delivery protocols are employed [

8,

10,

12].

There also several important limitations that constrain therapeutic efficacy and reproducibility, foremost among these is variable biological engagement following cell delivery. Multiple reviews and delivery-route analyses emphasize limited myocardial retention, rapid washout, and inconsistent paracrine signaling as major barriers to durable benefit [

12,

13,

17]. These factors likely contribute to the modest and heterogeneous functional improvements observed in clinical trials, despite robust preclinical efficacy [

12,

15,

17].

A second limitation concerns context-dependent responsiveness of the ischemic myocardium [

11,

22]. Experimental and animal studies demonstrate that metabolic state, inflammatory milieu, and substrate availability influence therapeutic response, with evidence that factors such as altered amino acid metabolism or advanced myocardial aging can restrict regenerative efficacy [

11,

22]. These findings could suggest that regenerative interventions do not operate in isolation but interact with complex host biology that is incompletely captured in early-phase clinical trial designs [

17,

22].

Additionally, although paracrine and exosome-mediated mechanisms are emphasized, standardization of exosome composition, dosing, and bioactivity remains lacking [

19,

20,

21]. Experimental studies demonstrate potent biological effects of engineered or targeted exosome platforms, but variability in production methods, cargo content, and delivery strategies complicates cross-study comparison and clinical translation [

19,

20,

21]. Long-term safety data for repeated or high-dose paracrine delivery also remain limited [

21].

Finally, critical commentary within the literature highlights concerns regarding trial design, endpoint selection, and interpretive overreach, particularly when modest surrogate improvements are extrapolated to broad clinical benefit [

15,

28]. These critiques reinforce the need for mechanistic alignment between intervention, biological target, and outcome measures, rather than reliance on infarct size or short-term functional metrics alone [

15,

28].

Author Contributions

JS designed the concept and outline; JS and SC performed the literature review; JS and SC drafted the manuscript; all authors critically revised and approved the final version.

Funding

University of Florida College of Medicine.

References

- Attar A, Farjoud Kouhanjani M, Hessami K, et al. Effect of once versus twice intracoronary injection of allogeneic-derived mesenchymal stromal cells after acute myocardial infarction: BOOSTER-TAHA7 randomized clinical trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):264. Published 2023 Sep 23. [CrossRef]

- Attar A, Mirhosseini SA, Mathur A, et al. Prevention of acute myocardial infarction induced heart failure by intracoronary infusion of mesenchymal stem cells: phase 3 randomised clinical trial (PREVENT-TAHA8). BMJ. 2025;391:e083382. Published 2025 Oct 29. [CrossRef]

- Barzegari A, Gueguen V, Omidi Y, Ostadrahimi A, Nouri M, Pavon-Djavid G. The role of Hippo signaling pathway and mechanotransduction in tuning embryoid body formation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(6):5072-5083. [CrossRef]

- Choudhery MS, Arif T, Mahmood R, et al. Induced Mesenchymal Stem Cells: An Emerging Source for Regenerative Medicine Applications. J Clin Med. 2025;14(6):2053. Published 2025 Mar 18. [CrossRef]

- Dias IX, Cordeiro A, Guimarães JAM, Silva KR. Potential and Limitations of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Musculoskeletal Disorders Treatment. Biomolecules. 2023;13(9):1342. Published 2023 Sep 4. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis V, Oltra E. Methods to produce induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Mesenchymal stem cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. World J Stem Cells. 2021;13(8):1094-1111. [CrossRef]

- Goto T, Nakamura Y, Ito Y, Miyagawa S. Regenerative medicine in cardiovascular disease. Regen Ther. 2024;26:859-866. Published 2024 Oct 5. [CrossRef]

- Heldman AW, Hare JM. Cell therapy for myocardial infarction: Special delivery. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(3):473-476. [CrossRef]

- Ito, F., Kitani, T. Current Advances and Challenges in Stem Cell-Based Regenerative Therapy for Chronic Limb-Threatening Ischemia. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med 27, 4 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Izumi A, Yau TM, Fedak PWM, Fatehi Hassanabad A. Pericardial Delivery of Stem Cells: An Emerging Frontier in Myocardial Regeneration for Ischemic Heart Disease. Can J Cardiol. Published online October 14, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jiang X, Chao L, Liu K, et al. Cationic microbubbles loading shFOXO4/SDF1 rejuvenate the aged heart and alleviate myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in the elderly. Free Radic Biol Med. 2025;237:210-227. [CrossRef]

- Khalili MR, Ahmadloo S, Mousavi SA, et al. Navigating mesenchymal stem cells doses and delivery routes in heart disease trials: A comprehensive overview. Regen Ther. 2025;29:117-127. Published 2025 Mar 13. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hu S, Zhu D, et al. All Roads Lead to Rome (the Heart): Cell Retention and Outcomes From Various Delivery Routes of Cell Therapy Products to the Heart. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(8):e020402. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Lv Y, Zhu D, et al. Intrapericardial hydrogel injection generates high cell retention and augments therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction. Chem Eng J. 2022;427:131581. [CrossRef]

- EXPRESSION OF CONCERN: Prevention of acute myocardial infarction induced heart failure by intracoronary infusion of mesenchymal stem cells: phase 3 randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2025;391:r2388. Published 2025 Nov 12. [CrossRef]

- Poliwoda S, Noor N, Downs E, et al. Stem cells: a comprehensive review of origins and emerging clinical roles in medical practice. Orthop Rev (Pavia). 2022;14(3):37498. Published 2022 Aug 25. [CrossRef]

- Stougiannou TM, Christodoulou KC, Dimarakis I, Mikroulis D, Karangelis D. To Repair a Broken Heart: Stem Cells in Ischemic Heart Disease. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(3):2181-2208. Published 2024 Mar 8. [CrossRef]

- Tang XL, Wysoczynski M, Li Y, et al. Comparative Effects of Repeated Intravenous Infusions of Progenitor Cells in a Rat Model of Chronic Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Stem Cell Rev Rep. Published online October 9, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Jiang R, Zhong F, et al. Ultrasound-triggered targeted delivery of engineered ADSCs-derived exosomes with high SDF-1α levels to promote cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. Int J Pharm. 2025;681:125786. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen J, Wang J, et al. MSCs biomimetic ultrasonic phase change nanoparticles promote cardiac functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2025;313:122775. [CrossRef]

- Yuce K. The Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Different Cardiovascular Disorders: Ways of Administration, and the Effectors. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2024;20(7):1671-1691. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Hu G, Chen X, et al. Excessive branched-chain amino acid accumulation restricts mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy efficacy in myocardial infarction. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):171. Published 2022 Jun 3. [CrossRef]

- Rittiphairoj T, Bulstra C, Ruampatana C, et al. The economic burden of ischaemic heart diseases on health systems: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2025;10(2):e015043. Published 2025 Feb 12. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) fact sheet (includes current global mortality estimates). Updated 2025.

- Hare JM, et al. Randomized Comparison of Allogeneic Versus Autologous Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy: POSEIDON-DCM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Feb 7;69(5):526-537. Epub 2016 Nov 14. PMID: 27856208; PMCID: PMC5291766. [CrossRef]

- Heldman AW, et al. Transendocardial mesenchymal stem cells and mononuclear bone marrow cells for ischemic cardiomyopathy: the TAC-HFT randomized trial. JAMA. 2014 Jan 1;311(1):62-73. PMID: 24247587; PMCID: PMC4111133. [CrossRef]

- Bartunek J, et al; CHART Program. Cardiopoietic stem cell therapy in ischaemic heart failure: long-term clinical outcomes. ESC Heart Fail. 2020 Dec;7(6):3345-3354. Epub 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 33094909; PMCID: PMC7754898. [CrossRef]

- Raynaud CM, Yacoub MH. Clinical trials of bone marrow derived cells for ischemic heart failure. Time to move on? TIME, SWISS-AMI, CELLWAVE, POSEIDON and C-CURE. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2013 Nov 1;2013(3):207-11. PMID: 24689022; PMCID: PMC3963753. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).