1. Introduction

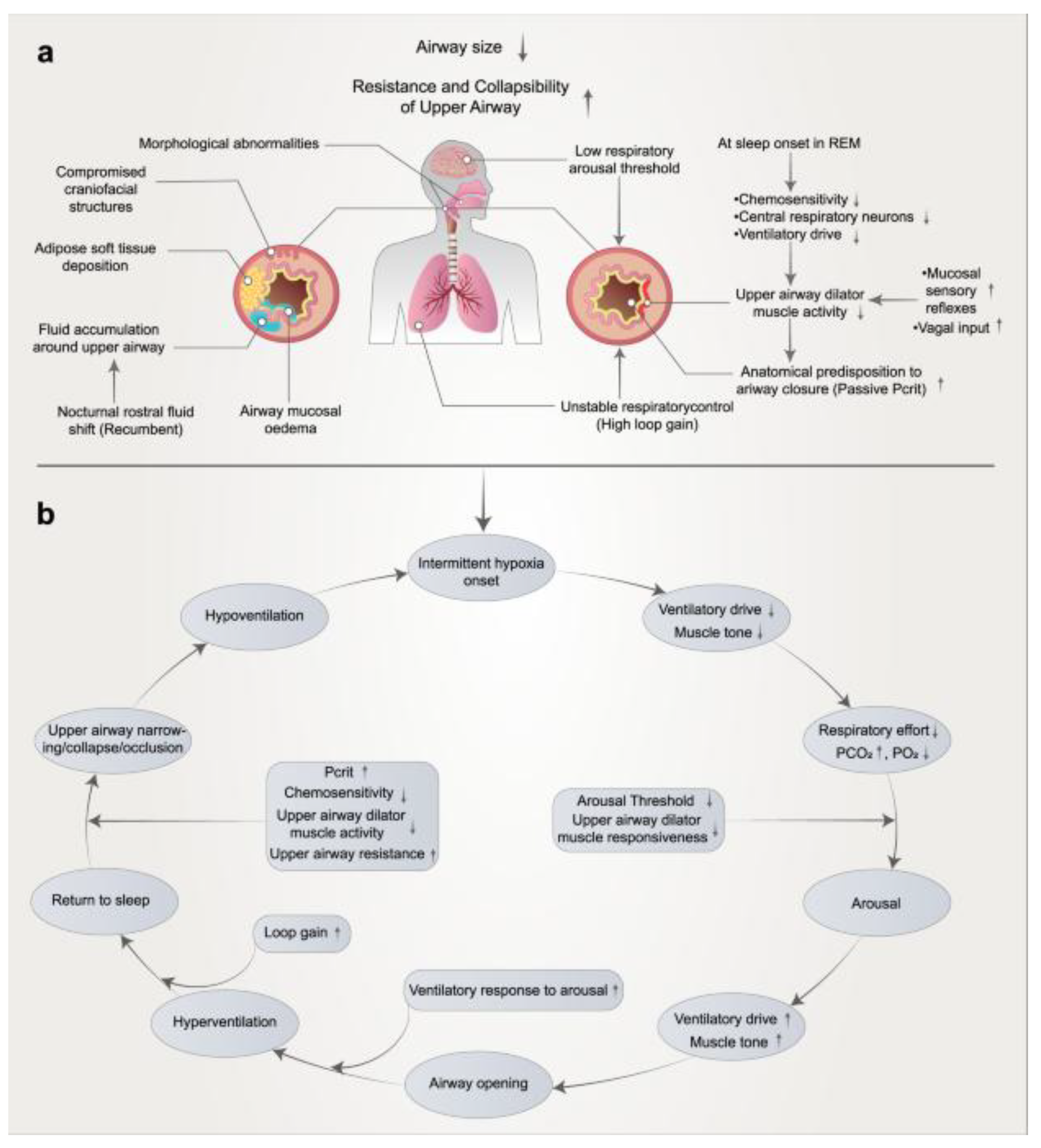

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common form of sleep-disordered breathing, affecting 10–30% of middle-aged adults, with even higher prevalence among older individuals and those with obesity. The pathophysiology of OSA involves recurrent pharyngeal airway collapse due to anatomical narrowing, impaired neuromuscular tone, and altered arousal thresholds. These events lead to intermittent apnea or hypopnea, resulting in oxygen desaturation and sleep fragmentation. [

1]

OSA is independently associated with increased risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, mood disorders, and cognitive impairment. It significantly contributes to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. The disorder also imposes a substantial economic burden due to elevated healthcare utilization and lost productivity. [

2]

While CPAP still remains the most prominent, some patients with mild-to-moderate OSA, nasal obstructions, claustrophobia, and those with higher BMIs often have long-term adherence rates below 50%. Discomfort with masks, dislike of the pressure, and the lifestyle burdens of the CPAP machine often led patients to discontinue CPAP therapy within the first 1-2 years. Due to these reasons, patients are recommended alternative treatment options in the case of CPAP intolerances: these include upper airway surgery, and, for patients with higher BMIs, bariatric surgery. [

3]

OSA management in Saudi Arabia faces challenges due to a lack of awareness, insufficient diagnoses, and uneven availability of services. Although the condition is highly prevalent, surgical interventions are not frequently employed because of a deficiency in multidisciplinary teams and the absence of standardized treatment protocols. Hence CPAP is first line therapy, but fails in a large proportion of patients. [

4]

Canada’s public healthcare system is associated with significant diagnostic delays, sometimes extending up to 16 months, and instances of underdiagnosis of OSA. [

5] For adult patients who cannot tolerate CPAP or do not want CPAP, surgical interventions such as UPPP, barbed pharyngoplasty, septoplasty, rhinoplasty, Tonge base reduction, and palatoplasty, and maxillomandibular advancement (MMA) are available. MMA is particularly effective, achieving a reduction in AHI of over 80% and allowing for independence from CPAP therapy, but carries higher patient burden and lower update. [

6,

7]

Conversely, the historically predominant model of surgical treatment of OSA has been Stanford (Powell-Riley) staged phase I/II protocol. Phase I is an approach that is site-directed, multilevel and usually involves retropalatal surgery (traditionally UPPP with or without tonsillectomy) plus treatment of retrolingual obstruction (genioglossus advancement with or without hyoid myotomy/suspension) and correction of clinically significant nasal obstruction when present; postoperative PSG is then performed to re-evaluate the results after healing. Phase II surgery, involving maxillomandibular advancement (MMA), is then offered to patients with enduring clinically significant OSA following phase I and this procedure is aimed at enlarging and stabilizing the entire pharyngeal airway with previously reported high success rates in the right patients.

2. Diagnostic Evaluation

2.1. Polysomnography (PSG)

PSG remains the gold standard for diagnosing OSA. It provides comprehensive evaluation of sleep architecture, respiratory disturbances, oxygen disturbances, oxygen desaturation and monitor brain waves, muscle activity, heart rate, and breathing during sleep. [

8].

There are two types of sleep studies which are overnight sleep study this one Conducted in a sleep lab or at home the second type is home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) which is considered a level III study is often better accepted by patients due to the improved reliability and validity of testing conducted in their own bed and pillow. Which is portable device measures breathing patterns. The sleep study monitor Sleep patterns, breathing, and other physiological activities. It helps in diagnose sleep disorders and guide treatment.

The sole use of ABI may falsely categorize the significant clinical improvement, that is why this protocol uses the SLEEP- GOAL framework proposed by Pang and Rotenberg as the main outcome measure, which focuses on multidimensional, patient-centered outcomes, not only on ABI. In a multicenter randomized trial of 302 adults undergoing nose, palate, and/or tongue surgeries, overall success by conventional Sher AHI methods was 66.2, compared to SLEEP-GOAL which found another group of responders who experienced considerable benefits in blood pressure, body mass index/weight, and hypoxemia load (reduced oxygen saturation below 90%), although not by AHI standards- more sensitive to clinical change in areas where patients care. Practically, SLEEPGOAL idealizes success by necessitating change in key areas (blood pressure, BMI/weight, nocturnal hypoxemia, AHI) that are complemented by complementary symptom measures, and is a more global measure of surgical success than AHI minimization. [

9]

2.2. Drug-Induced Sleep Endoscopy (DISE)

DISE enables dynamic assessment of upper airway obstruction under sedation, better simulating natural sleep conditions than awake examinations. It is especially useful in identifying obstruction patterns undetectable on physical exam or imaging. The VOTE classification system (Velum, Oropharynx, Tongue base, Epiglottis) is used to categorize collapse as anteroposterior, lateral, or concentric. [

10]

DISE aids preoperative planning by identifying obstruction levels and gauging response to maneuvers like mandibular advancement. The mandibular pull-up (MPU) test can evaluate improvement in airway patency during DISE. [

11]

Contraindications of DISE include High ASA class, allergy to sedatives (e.g., propofol, midazolam) or AHI >70, severe obesity.

Reviewing the data on the failure rates of DISE-directed upper airway surgeries demonstrates that the failure rates are quite low (insert reference), and that collapsing patterns that are associated with failures (such as a complete circumferential collapse of the velum) can be predicted by DISE, thus confirming its value in customizing both single and multi-level surgical interventions. (REF)

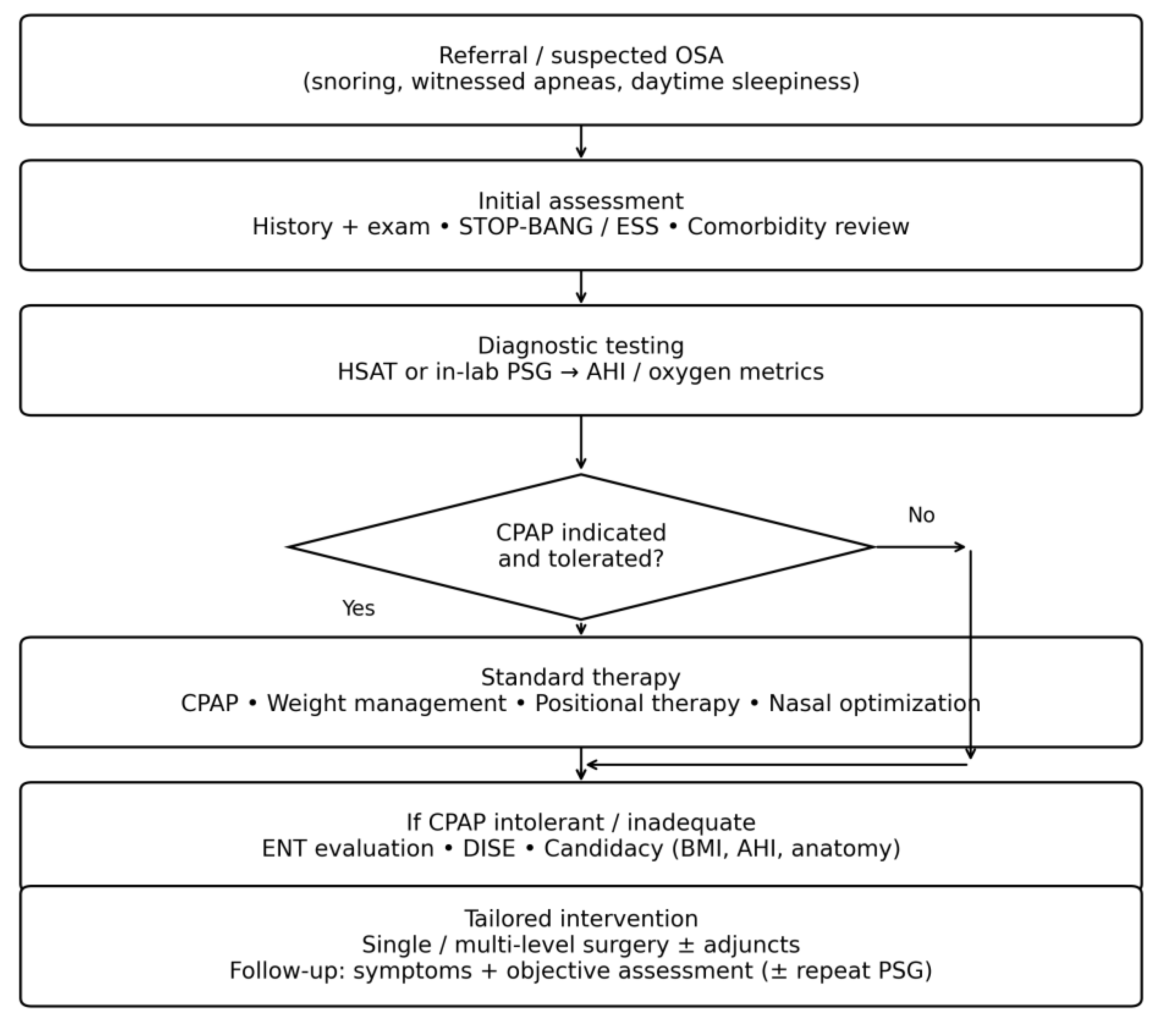

Figure 2.

Patient pathway for evaluation and management of obstructive sleep apnea in this protocol.

Figure 2.

Patient pathway for evaluation and management of obstructive sleep apnea in this protocol.

3. Surgical Protocol Overview

3.1. Indications for Surgery

Surgical intervention is considered in patients with CPAP intolerance or ineffectiveness, patients who do not want to be on CPAP, Moderate-to-severe OSA confirmed on PSG, Identifiable anatomical obstruction and those with Significant symptoms but a negative sleep study and elevated STOP-BANG or Epworth scores

3.2. Multi-Level Surgical Approach

Given the multi-level nature of OSA, tailored surgery based on DISE findings is essential. Common procedures include: Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) continues to be the predominant surgical intervention for sleep apnea globally. Many surgeons who specialize in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have ceased utilizing earlier, more ablative techniques of UPPP, which include the removal of the uvula. This shift is particularly evident in procedures like laser-assisted UPPP, which, according to a meta-analysis, exacerbates the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) in 44% of patients. When considering isolated soft palate surgeries, these demonstrate the highest success rates for patients classified as Friedman stage I. In practice, various UPPP techniques are frequently incorporated into multi-level surgical approaches to enhance overall surgical outcomes. An isolated UPPP is indicated as a component of a staged strategy for UAS. The observation of CCC in the soft palate (velum) during DISE serves as a disqualifying factor for UAS; however, Palat pharyngoplasty can rectify this collapse pattern, thereby enhancing eligibility for UAS [

8]. Septoplasty and turbinate reduction lead to Improve nasal airflow and CPAP tolerance, midline glossectomy or tongue base reduction which is help in address tongue base hypertrophy, lingual tonsillectomy performed especially in pediatric or syndromic OSA. Untreated obstruction in the retrolingual region is widely acknowledged as a primary factor contributing to unsuccessful surgical outcomes. [

8] The excision of the lingual tonsils and adipose tissue at the base of the tongue may be performed using techniques such as coblation, laser, or robotic assistance, depending on the surgeon’s preference. Additionally, tissue removal in this region can be enhanced by securing the epiglottis to the base of the tongue to prevent epiglottic collapse. And palatoplasty: Indicated in epiglottic collapse on DISE, Maxillomandibular advancement was first developed by Riley and Powell at Stanford Hospital during the late 1980s, targeting the entire upper airway that may contribute to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). It continues to be one of the most effective surgical options for patients suffering from OSA and has shown favorable comparisons to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in various studies, including a prospective, randomized controlled trial [

8]. The procedure entails performing osteotomies on both the maxilla and mandible, which are then advanced, often accompanied by a counterclockwise rotation. This results in an increased volume for the intraoral soft tissue structures and enhances the stability of the upper airway dilator muscles. The general criteria for considering MMA include: 1. moderate to severe OSA, with or without a prior phase 1 surgery, 2. OSA of any severity when accompanied by coexisting dentofacial deformities, and 3. the presence of concentric and lateral pharyngeal wall collapse observed during drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE). [

8]

Single-stage surgery may suffice for selected patients, while staged interventions may be preferable for severe or comorbid cases. [

12]

3.3. Perioperative Management

3.3.1. Preoperative Evaluation

BMI and OSA, most individuals diagnosed with sleep apnea are overweight. There is a robust and consistent link between the severity of the condition and obesity. (

Figure 1) Based on our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and the influence of fat accumulation around the upper airway, this relationship is causal in nature. Weight loss not only alleviates sleep apnea but can also lead to its complete resolution. Therefore, for many patients, sleep apnea serves as an indicator of obesity, suggesting that addressing the root cause is preferable to merely treating the symptom. This perspective is especially relevant from a public health standpoint, as the connection between obesity and cardiovascular disease is strong and well-documented. By managing obesity, we can not only mitigate sleep apnea but also decrease the likelihood of heart disease and strokes. This strategy has the potential to enhance the overall health of both individuals and the community. [

6] BMI ≤35 is often used for candidacy, though outcomes can be optimized with weight reduction (e.g., Tripeptide or GLP-1 agonists such as semaglutide). Preoperative labs, imaging, and comprehensive PSG review are mandatory. Before the surgery patient should receive antibiotics such as cefazoline 2-gram on call to OR and 2 more dose post op also Corticosteroids is recommended to be given pre op and 2 more dose post op

3.3.2. Intraoperative Protocol

The surgical procedure involves a reverse OR table setup to enhance airway exposure, followed by a sequential approach consisting of tonsillectomy, UPPP, and tongue base reduction. Collation ensures precision during the procedure. Laryngoscope access is facilitated using a Lindholm or FK retractor. Hemostasis and analgesia are achieved with local bupivacaine and epinephrine, specifically 0.5% Marcaine with 1:100,000 or 1:200,000 epinephrine

3.3.3. Postoperative Care

Patient should be discharged on pain killer medication like Celecoxib 200 mg oral capsule (liquid) 200mg 1 cap BID along with Tylenol 650 mg Q8H for 7 days. Also, we recommend to prescribed Magic mouth wash which contains (aluminum- magnesium Hydroxide Suspension, Diphenhydramine 2.5 mg\ml LIQ, Lidocaine Viscous 2%). Monitor for airway compromise and hemorrhage is mandatory especially in high-risk patients. if the patient is diagnosed with severe OSA PSG at 6 months post op is recommended, may we consider adjunctive therapies post-op (e.g., positional therapy, oral appliances).

4. Discussion

The treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has greatly progressed due to enhanced diagnostic methods and a deeper comprehension of the disease’s variability. Surgical options, which were previously viewed as a last resort, now play a key role in the tailored management of patients who do not consistently use CPAP or have structural issues that lead to airway obstruction. [

12]

Drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) has emerged as a key component in preoperative assessments, facilitating a dynamic evaluation of upper airway blockages in a sleep-like condition. This technique allows for the detection of collapse patterns at multiple levels and the customization of treatments based on individual anatomical features, leading to enhanced surgical results and greater patient satisfaction. [

12]

A protocol-driven surgical framework that integrates endoscopic evaluation, anatomical phenotyping, and validated clinical instruments has been established as a best practice model. This methodology is associated with enhanced reductions in Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), improved quality of life, and the potential for decreased the risk of chronic diseases However, challenges remain, including the need for optimal patient selection, the management of perioperative risks in obese patients, and the assessment of long-term efficacy, and the lake of Hypoglossal nerve stimulation all of which require systematic investigation. [

14]

5. Conclusion

Obstructive sleep apnea is a multifaceted and varied condition that necessitates a tailored, multidisciplinary strategy. For patients who do not comply with CPAP treatment or have anatomical issues that can be fixed, surgery presents an appealing treatment option.

A strategy predicated on established protocols, informed by DISE results, clinical assessment scores, and individualized anatomical factors of patients has exhibited enhanced results in meticulously chosen instances.

Insights from Saudi Arabia and Canada highlight the significance of tailoring approaches to specific regions, implementing standardized training, and providing multidisciplinary care to improve surgical outcomes. With advancements in technology and a deeper understanding of OSA phenotypes, new innovations like robotic-assisted surgery, hypoglossal nerve stimulation, and medication for weight management are enhancing patient results. Ongoing research, especially through multicenter trials and cost-effectiveness analyses, is crucial for confirming these developing protocols and expanding global access to care. By utilizing personalized surgical planning and comprehensive perioperative care, healthcare providers can more effectively address the needs of patients with OSA and improve their long-term quality of life.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: No ethical statement or consent to participate needed in this protocol report.

Funding

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2024R467), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Rishi, M; Mandavia, N; Mehta, N. Guidelines on the surgical management of sleep disorders: A systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017, 156(3 Suppl), S1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, KT; Yeh, TH; Ko, JY; Lee, CH; Hsu, WC. Effect of sleep surgery on blood pressure in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020, 51, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotecha, B; De Vito, A. The role of drug-induced sleep endoscopy in the diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: our personal experience. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2018, 38(5), 390–6. [Google Scholar]

- BaHammam, A. S. Sleep medicine in Saudi Arabia: Current problems and future challenges. Annals of Thoracic Medicine 2011, 6(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenberg, B. W.; George, C. F.; Sullivan, K. M.; Wong, E. Wait times for sleep apnea care in Ontario: A multidisciplinary assessment. Canadian Respiratory Journal 2010, 17(4), 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayas, NT; Hirsch Allen, AJ; Skomro, RP; et al. The impact of sleep apnea on public health in Canada. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med. 2017, 1(1), 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pendharkar, SR; Sivakumaran, S; Ayas, NT. Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in Canada: current trends and barriers to care. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019, 48(1), 42. [Google Scholar]

- Li, HY; Wang, PC; Hsu, CY; Chen, NH. Surgical algorithm for obstructive sleep apnea: An update. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 13(3), 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Certal, V; Camacho, M; Capasso, R; Kushida, CA. Diagnostic value of drug-induced sleep endoscopy in the prediction of outcomes of surgery for obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep 2016, 39(5), 1069–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kezirian, EJ; White, DP; Malhotra, A; Ma, W; McCulloch, CE. Interrater reliability of drug-induced sleep endoscopy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136(4), 393–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strollo, PJ; Soose, RJ; Maurer, JT; de Vries, N; Cornelius, J; Froymovich, O; et al. Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370(2), 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, AA; Murphey, AW; Nguyen, SA; Weaver, EM; Mims, JB; Gillespie, MB. Efficacy of hypoglossal nerve stimulation on OSA outcomes: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016, 154(2), 270–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, KP; Woodson, BT. Expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty: a new technique for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007, 137(3), 110–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, AR; Patil, SP; Laffan, AM; Polotsky, V; Schneider, H; Smith, PL. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea: pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008, 5(2), 185–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, R; Liu, X; Zhang, Y; et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms and therapeutic approaches in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |