1. Patent Analysis

An analysis of the selected composition of 23 patents [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

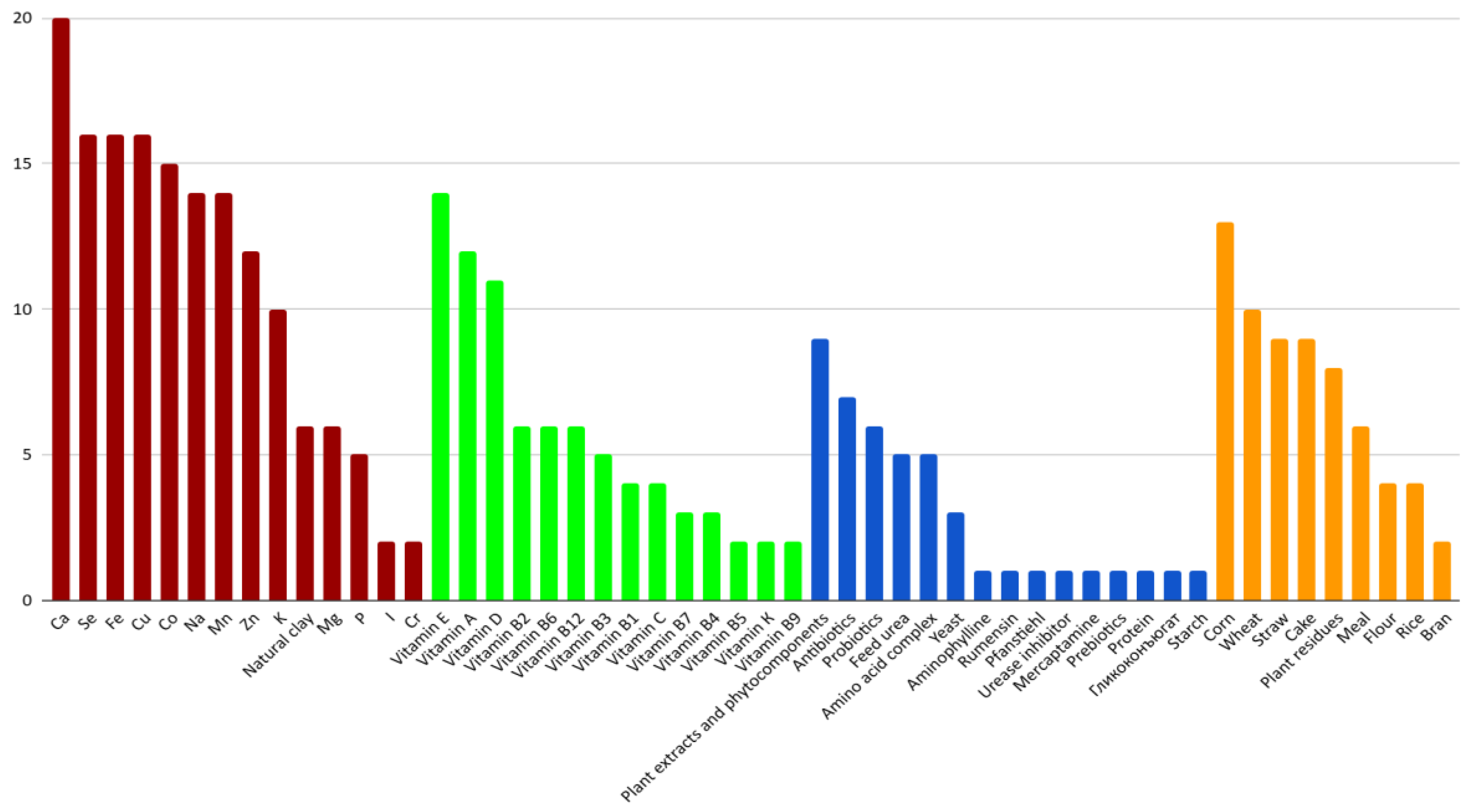

36] has shown the presence of groups consisting of minerals, vitamins, functional additives (medicines, plant extracts, bacterial strains), and forage plants. The frequency of use and composition of the ingredient groups of mineral and vitamin complexes (MVCs) for addition to the diet of pregnant ewes and lambs are shown in

Figure 1.

Comprehensive analysis on the demand of MVC components in patent research provides an information that most attention is given to mineral additives, among which calcium, selenium, iron, copper, cobalt, sodium, manganese, zinc, and so on are often found. Their high demand reflects the key role of these macro- and microelements in regulating metabolic processes, bone formation, and the functioning of the body's immune and antioxidant systems. Vitamin supplements occupy the second most important place, while vitamins E, A and D are the most widely studied, due to their effect on antioxidant protection, growth, development and reproductive functions. The third large group consists of grain plants (corn, wheat), various types of straw and remnants of agricultural plants. There is additional considerable interest in the use of enzymes and probiotics aimed at optimizing digestive processes and improving nutrient absorption. Although antibiotics are presented in 6 patents, there is an increasing trend of interest in phytobiotics and plant extracts as potential alternatives to synthetic medical drugs. In general, the distribution of research interest emphasizes the priority of ensuring the mineral and vitamin status of animals, improving metabolic processes, and feeding efficiency, as well as a gradual transition to more environmentally friendly and safe alternatives to traditional growth stimulants.

2. Minerals and Microelements

2.1. Calcium

The key mineral element of feed additives is calcium, as it is found in 20 [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

23] of 23 patents. At the same time, the variation of calcium sources is very wide: calcium phosphate (Ca

3(PO

4)

2) [

3,

4,

5,

10,

12,

13,

14,

17,

20,

21], calcium sulfate (CaSO

4)[

12,

15], bone meal (Ca

3(PO

4)

2 58-36%)[

3,

4,

5,

10,

12,

13,

14,

17,

20,

21], calcium carbonate (CaCO

3)[

3,

5,

10,

23], calcium hydrophosphate (CaHPO

4), limestone powder (CaCO

3), rock flour (CaCO

3). Calcium is the main structural element of the bone and dental tissue of the entire living organism, also participates in the transmission of nerve impulses, muscle contraction and blood clotting processes [

30]. Calcium not only provides mineral homeostasis and productivity, but also affects the development of young animals, immune responses and the intestinal microbiota[

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In sheep farming, calcium deficiency is especially common during pregnancy and lactation, leading to osteodystrophy, shortage of milk yields, and the birth of weak lambs [

25,

30].

The work of Shkembi & Huppertz (2022) illustrated that the effective use of calcium depends not only on its content in the diet, but primarily on the form in which it comes and on the structure of the feed. For absorption, calcium must enter an ionized state, and this process is determined by the acidity of the stomach, the rate of passage of food through the intestines, and the interaction of calcium with other components of the diet. Sources of calcium that dissolve easily or are quickly released in an acidic environment can enter the intestine simultaneously, as a result of which some of the calcium does not have time to be absorbed and precipitates. On the contrary, feeds with a denser structure or forms of calcium with gradual release ensure its uniform and prolonged intake into the intestine, which increases the overall degree of absorption. In plant-based diets, the presence of phytates and oxalates significantly reduces the bioavailability of calcium due to the formation of insoluble complexes. At the same time, calcium from mineral and animal sources is usually less strongly bound and absorbed better. In this regard, when feeding sheep, it is important to take into account not only the level of calcium in the diet, but also its chemical form, the matrix structure of the feed and the ratio to phosphorus, since these factors determine the actual effectiveness of calcium in maintaining mineral metabolism and bone formation [

24].

In the experiments of Brugger and Liesegang (2025) [

25], during the last three weeks of pregnancy and 56 days after lambing, dairy sheep and goats were given calcium carbonate in two doses: normal content in the diet (0.6% of dry matter) and increased (1.3%). The results showed that even with an excess of calcium, there were no clinical signs of hypocalcemia in the animals: the body coped due to increased excretion with feces. Blood calcium concentration and bone mineral density remained stable, but osteocalcin levels increased. At the same time, lambs and goats did not differ in birth weight from mothers with a high calcium content in the diet, but the average daily weight gain during suckling turned out to be lower. Thus, the study confirmed that excess calcium at the end of pregnancy does not cause acute metabolic disorders, but it can adversely affect the growth of young animals due to changes in lactation physiology.

In the research by Braithwaite (1983) [

26], study of calcium-phosphorus metabolism in sheep during pregnancy and lactation. Of the 26 queens of the Suffolk breed, she received a diet according to ARC standards (1980), and some received an excess content of calcium and phosphorus. The animals were kept in metabolic cells, which made it possible to collect urine and feces separately. In different periods — the end of pregnancy, early, middle and late lactation, as well as after it — balance experiments were conducted and radioisotopes of calcium-45 and phosphorus-32 were introduced. Then, for 7 days, blood, milk, urine and feces were taken to determine the level of calcium absorption, its loss with secretions and mobilization from bones. This approach made it possible to compare how sheep with different levels of calcium and phosphorus in the diet are able to cover the need for minerals during pregnancy and lactation. Studies show that at the end of pregnancy, sheep cannot fully cover the increased need for calcium due to intestinal absorption, so the body uses bone reserves. These reserves are restored only in the middle and end of lactation with sufficient intake of calcium and phosphorus. At limited rates (ARC, 1980), a negative calcium balance is maintained by the end of lactation, which indicates incomplete replenishment of bone depots. Therefore, the existing recommendations on calcium rationing for sheep require revision: in the prenatal period, doses should be moderate, and in the middle and end of lactation, they should be higher in order to effectively restore bone reserves.

A study by Ni et al. (2024) made it possible to specify the mechanisms of regulation of calcium metabolism in growing Yunnan semi-fine-fleeced sheep. The authors showed that when the calcium content in the diet is 0.73% of the dry matter, the maximum average daily increase is achieved, while the level of 0.89% provides the highest degree of calcium retention in the body. With a further increase in calcium concentration (up to 0.98%), a decrease in the utilization rate and a deterioration in feed conversion were observed, which indicates a decrease in the bioavailability of the mineral in excess. Thus, the work of Ni and colleagues has experimentally confirmed that optimal calcium levels in the diet of sheep are limited to a narrow range (0.73–0.89% CB), which provides a balance between growth and effective absorption of the macronutrient [

27].

The practical importance of calcium-magnesium supply during the transition period was shown by Ataollahi et al. (2020). Additional administration of calcium and magnesium to pregnant and lactating sheep improved the mineral status of mothers and promoted a better immune response and accelerated growth of lambs [

28]. Thus, a moderate excess of the basic macronutrient standards has a positive effect on the viability of the offspring.

Abdelrahman's results confirm this conclusion for Awassi sheep.: An increase in calcium to 1% of the dry matter increased its level in the blood and colostrum of ewes, and also improved the mineral status of lambs [

29]. At the same time, the addition of the vitamin complex AD₃E enhanced the calcium response, but it did not always lead to a greater increase in the weight of young animals, which emphasizes the importance of choosing doses and timing of administration.

Research by Khan et al. (2025) aimed to study how different levels of calcium in the sheep diet affect the composition and functional characteristics of the microbiota of the posterior intestine. The authors have shown that a change in the calcium content in the feed leads to a restructuring of the intestinal microbial community, including changes in species diversity and the ratio of the main bacterial groups [

30]. With a higher level of calcium in the diet, the proportion of bacteria involved in the formation of short-chain fatty acids, primarily butyrate, increased, and the predicted metabolic potential of the microbiota changed towards enhancing pathways associated with energy metabolism. The data obtained indicate that calcium in the diet affects not only the mineral metabolism and physiological state of animals, but also the intestinal microbiota, through which it can indirectly affect the efficiency of nutrient use and productivity of sheep.

2.2. Zinc

Zinc is found in the mineral and vitamin complexes of 12 patents [

3,

4,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

20,

21]. Zinc ions are represented in the forms of zinc sulfate (ZnSO₄) [

3,

4,

8,

10,

11,

16,

17,

20,

21], zinc oxide (ZnO) [

14] and zinc methionine[

13]. Zinc plays an important role not only in well-known metabolic and immune processes, but also in ensuring reproductive potential, improving the quality of oocytes and the development of embryos [

31]. According to a study by Xiwei Jin and co-authors insufficient intake of Ca and Zn in sheep disrupts mineral and protein metabolism, causes liver damage and weakens physiological functions. However, even supplements do not always lead to the restoration of normal values due to low bioavailability and antagonism between the elements. For example, zinc can reduce copper absorption [

32], which highlights the importance of balanced mineral support and early detection of hidden deficiencies.

In the work of G. Bellof et al. The effect of fattening intensity (up to a live weight of 18, 30, 45 and 55 kg) on the content of trace elements in various tissues was studied on 108 lambs of the German Merino breed [

33]. An increase in nutrition levels led to an increase in daily gain and a decrease in energy expenditure per 1 kg of gain. At the same time, there was a decrease in Zn and Cu concentrations in tissues during high-intensity fattening, especially in females, while the Mn level often remained below the detection limit. These data confirm that the bioavailability and distribution of trace elements may vary depending on gender, growth stage, and feeding level.

A study by K. Alijani and colleagues [

34] has demonstrated that the introduction of various forms of zinc (inorganic (ZnO), organic (zinc methionine) and nanoforms (nano-ZnO)) into the diet of sheep has a positive effect on the digestibility of nutrients and body weight gain. A particularly pronounced effect was observed when using organic and nanoscale forms: they provided a higher concentration of Zn in plasma and rumen contents, enhanced antioxidant activity (FRAP), reduced the level of ammonia and urea in the blood, and stimulated microbial protein synthesis [

34]. Confirmation of these data is also contained in the study by Rodríguez-Maya et al., where lambs receiving combined Zn-Met + ZnO supplements showed the greatest weight gain, improved feed conversion and meat quality (marbling, softness of Longissimus dorsi muscles). This is associated with different mechanisms of absorption and bioavailability of zinc forms, as well as with its effect on regulatory proteins: ZnT7, ZnT8 and ZIP7 involved in insulin signaling pathways, glycemic control and differentiation of muscle cells. The organic form of zinc increased the content of arachidonic acid, while ZnO reduced the amount of visceral fat and saturated myristic acid [

35]. The use of an organic form (zinc methionine) increases bioavailability and at the same time reduces the negative effects of high doses of inorganic salts, improves metabolism [Moh. Sofi’ul Anam , Andriyani Astuti , Budi Prasetyo Widyobroto , Ali Agus]. Similar conclusions have been confirmed in experiments on calves. Liu et al. It was found that the organic form of zinc (zinc proteinate, ZnPro) provides a more stable weight gain compared to ZnO, increases the immune response (IgG, IgM levels), reduces the frequency of diarrhea, and enhances the body's antioxidant defense [

36].

The mechanisms of zinc absorption in the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, including sheep, largely determine its bioavailability [

37]. According to D.L. Hampton, using radiolabeled zinc, it was found that upon oral administration, the element is absorbed along the entire length of the small intestine without pronounced localization in a certain section [

38], which indicates that the absorption efficiency depends on the duration of contact of the chyme with the mucosa. In case of deficiency, it has been found that the posterior intestine has an extremely limited ability to absorb zinc and does not play a compensatory role. Thus, the main contribution to zinc absorption in ruminants is made by the small intestine, and the level of absorption is determined by the physiological state of the body and the availability of the trace element. The use of organic and nanoforms of Zn can significantly increase its digestibility and physiological effectiveness, especially with rational dosage selection and consideration of animal specificity [

39].

According to the assessment of the European Food Safety Authority (2023) [

40], the zinc chloride hydroxide monohydrate (IntelliBond Z) feed additive is recognized as safe for all animal species at the current level of use and does not pose a threat to consumers. On average, the Zn content in the product is about 57%, the main crystalline phase is simoncolleite. For users, the risk is mainly related to eye irritation and the possibility of dust inhalation, while skin sensitisation has not been confirmed. From an ecological point of view, the additive is acceptable in land-based farms and aquaculture, although data remain limited for marine systems. Research in the field of materials science expands the understanding of the biological role of simoncolleite. So, Li et al. (2019) [

41] showed that simoncolleite, anchored to a poly (amino acid) matrix, is able to stimulate osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, increasing mineralization while inhibiting osteoclast formation. In addition, the material showed pronounced antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Thus, the prospects of simoncolleite-based compounds are determined not only by their role as a source of zinc, but also by their additional osteotropic and antimicrobial properties.

Thus, zinc is not just a structural trace element, but a multifunctional regulator that affects metabolism, growth, immunity, and product quality.

2.3. Selenium

Selenium is mentioned in 16 patents [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

19,

20,

21] in the forms of sodium selenite and nanoselene. The doses range from 0.013–1.123 mg. Selenium and vitamin E in the sheep body function as interrelated elements of a single antioxidant system[

42]. Vitamin E performs a primary protective role at the level of cell membranes, preventing the development of chain reactions of polyunsaturated fatty acid peroxidation and preserving the structural integrity of the membranes. Selenium, in turn, is a part of glutathione peroxidase and other selenoproteins, ensuring the restoration of already formed peroxides and maintaining intracellular redox balance, thereby complementing the membrane protection of vitamin E (Van Meter and Callan, 2001)[

42]. Experiments on sheep have shown that the combined administration of vitamin E and selenium significantly reduces the levels of cortisol, malondialdehyde and heat shock proteins and simultaneously increases the activity of antioxidant enzymes compared with the control Shakirullah and the authors (2017)[

43]. In case of heat stress in sheep, the use of vitamin E in combination with selenium improves the antioxidant status and reduces the negative effect of high temperatures on physiological parameters, which indicates their functional complementarity and interdependence Chauhan et al. (2014)[

44]. NRC regulatory data emphasize that a deficiency of one of these nutrients increases the need for the other and reduces the overall effectiveness of antioxidant protection, especially in conditions of stress, growth, and reproduction (NRC, 2007)[

45].

Research on the role of selenium (Se) and vitamin E in sheep highlights their importance as antioxidants and factors supporting reproductive function and adaptation to stress. In the experiments of Chauhan et al. (2015) Merino Poll Dorset sheep have shown that high doses of selenium and vitamin E mitigate the effects of heat stress [

44]. Animals receiving combined supplements were characterized by a lower respiratory rate and rectal temperature, improved acid-base balance of the blood, as well as increased glutathione peroxidase activity and antioxidant potential of plasma, which indicates the synergy of these nutrients in protecting against oxidative stress at high temperatures.

The practical importance of using vitamin E and selenium is also evident in improving reproductive performance. In the work of Musa et al. (2018), conducted on Yankasa sheep in Nigeria, noted that the administration of vitamin E alone or in combination with selenium increased the manifestation of hunting, the percentage of fertilization and the yield of lambs. In addition, the lambs had a higher average daily weight gain and a reduced risk of stillbirths and afterbirth retention [

46]. This confirms that antioxidant protection plays a key role not only in maintaining the health of the uterus, but also in the viability of the offspring.

In the work of Shakirullah and colleagues (2017) [

43], who studied sheep of the Damani and Balkhi breeds in the hot climate of Pakistan. The addition of 0.3 mg Se and 50 mg vitamin E per 1 kg of feed for four weeks resulted in a decrease in body temperature, respiratory rate and cortisol levels, as well as an increase in thyroid hormone concentrations and the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase). At the same time, there were breed differences: Damani sheep showed higher resistance to heat stress compared to Balkhi [

43]. Thus, antioxidant supplements can not only reduce the physiological stress from heat, but also increase the endocrine adaptivity of animals.

Thus, selenium and vitamin E in the sheep diet provide pronounced antioxidant protection, increase reproductive performance and resistance to heat stress. Their use is especially relevant in conditions of micronutrient deficiency in feed and hot climates, where the risk of oxidative and thermal stress is greatest.

2.4. Iron

Iron is found in 17 patents [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

19,

20,

21] in the form of ferrous sulfate and ferric methionine. Dosages of 1.5–8% are used. The use of organic chelate forms is associated with the prevention of anemia in lambs and the support of hematopoiesis [

47]. Asadi et al. (2022) showed [

47] that the addition of organic iron to newborn lambs with milk (25 or 50 mg/day) It helps to increase the average daily weight gain, increase body weight by 10, 20 and 30 days and improve erythrocyte parameters (erythrocytes, hemoglobin, hematocrit, average hemoglobin concentration in the erythrocyte), which is due to the high risk of iron deficiency in the early postnatal period. At the same time, a decrease in the concentration of copper in plasma was noted, which reflects the antagonism of Fe and Cu, emphasizing the need to control the mineral balance. The antioxidant status was characterized by a decrease in the total antioxidant capacity of plasma while increasing the activity of enzymatic antioxidants (GPx, SOD, CAT), without increasing the level of MDA, which may indicate an adaptive enhancement of enzyme protection. An increase in insulin and thyroid hormones was noted with a decrease in glucose, which the authors attribute to an improvement in metabolism. Based on the data obtained, the optimal dose is 25 mg/day, which provides a positive physiological effect without the risk of excessive iron intake and pronounced violations of the mineral status [

47]. The forms and doses of iron significantly affect the effectiveness of its use in farm animals. A study by Xing et al. (2023) conducted on pregnant sows is indicative in this regard [

61]. The inclusion of lactoferrin, heme iron, or the iron-glycine complex in the diet did not significantly affect the main reproductive parameters (nest size, birth weight of piglets), but significantly improved the iron supply and the state of the antioxidant system in queens and newborn piglets. All three forms of iron increased its content in the placenta, blood serum and milk of sows, while in piglets the distribution of the element depended on the form of the supplement and varied between organs and tissues. The antioxidant parameters in queens generally improved, while in piglets the response was more variable; lactoferrin provided the best and most stable effect, enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the expression of the corresponding genes. Thus, iron-containing supplements do not necessarily improve reproductive performance, but when used in the second half of pregnancy, they contribute to the formation of adequate iron reserves in offspring and improve antioxidant status [

48].

In general, organic forms of iron are characterized by higher bioavailability and are able to maintain the antioxidant status of animals provided they are adequately supplied with iron. However, the effectiveness of their use largely depends on the dose: in the absence of deficiency, additional administration of organic iron is not accompanied by pronounced posit ive effects. On the contrary, excessive intake of iron, even in chelated form, can increase oxidative stress and disrupt the mineral balance, negatively affecting metabolism and the functional state of organs [

49].

2.5. Copper

Copper is found in 16 patents [

1,

2,

3,

4,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

20,

21] in the form of copper sulfate or as a nano structure. Copper deficiency and excess have different effects on sheep physiology [

49]. In the experiment, Song et al. [

50] in Wumen sheep, it was shown that excessive copper intake in the nanoform is accompanied by inhibition of hematopoiesis, increased activity of liver enzymes (AST, ALT), creatine phosphokinase (CPK) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), decreased activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GSH-Px, CAT) and an increase in the concentration of malondialdehyde, which indicates to enhance the processes of lipid peroxidation. The data obtained emphasize the high sensitivity of sheep to copper and the need for careful use of nanoforms of trace elements.

Data from Dickson (South Australia) indicate that copper deficiency has economically significant consequences, including decreased fertility, the birth of weak lambs and an increase in their mortality, as well as a deterioration in wool quality [

51]. The use of various correction regimens (injections, boluses, mineral blocks, suspensions) generally increased liver copper reserves, however, the severity and duration of the effect varied significantly depending on the conditions. The key limiting factor remains the influence of antagonists (molybdenum, sulfur, iron), which sharply reduce the bioavailability of copper and can neutralize the effectiveness of standard mineralization programs. Studies by Senthilkumar et al. [

52] on Nellore sheep have shown that the addition of copper to the diet (7-14 milligrams per kilogram of dry matter, ppm) in the form of copper sulfate (Cu

2SO

4) or organic copper proteinate (copper proteinate is copper bound to protein) enhances both the humoral and cellular immune response. At the same time, titers of antibodies to Brucella abortus and erythrocyte antigen increase, lymphocyte proliferation and the severity of delayed-type skin hypersensitivity reactions increase [

52]. At the same time, the activity of copper-dependent enzymes, superoxide dismutase, in red blood cells and ceruloplasmin in blood serum increases, reflecting an increase in the antioxidant defense of the sheep body. The organic form of copper (proteinate) enhanced immunity better than copper sulfate. However, the enzyme of antioxidant protection in the liver (superoxide dismutase) reacted more strongly to sulfate. The maximum effect on the antibody response was observed at a dose of about 16 ppm of copper.

Thus, copper is a critically important trace element for sheep, and both its deficiency and excess lead to adverse effects on health and productivity. When developing mineral supply strategies, it is necessary to take into account the soil–plant–animal system, the influence of antagonists, as well as the form of administration (organic or inorganic) and the dose of copper, taking into account the initial status of the herd and production conditions. Copper nanoforms require a separate assessment of toxicological risks and expediency of use.

2.6. Manganese

Manganese is found in 14 patents [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

20] in the form of manganese sulfate (MnSO₄·H₂O) or methionine form (Mn-Met). Manganese (Mn) plays an important role in reproductive function and mineral metabolism in sheep, while the use of its organic forms is justified by its higher bioavailability. A study by Hidiroglou et al. (1978) showed that a low manganese content in the diet of queens (8 ppm) led to a decrease in the concentration of Mn in the blood and a deterioration in reproduction (sheep needed more milk for pregnancy) [

53]. Newborn lambs from this group had lower levels of calcium and iron in their tissues compared to the control group. The introduction of manganese in a dose of 60 ppm into the diet of the queens contributed to the normalization of the mineral status of the lambs. Thus, a sufficient supply of manganese is an important condition for normal reproduction in ewes and the health of offspring.

The study examined the effectiveness of adding organic manganese to the diet of Afshari sheep during the transition period, as well as its effect on productivity, nutrient absorption, milk production and milk composition, along with the health indicators of their lambs. Since up to 75% of fetal growth occurs in the last two months of pregnancy (the period of late pregnancy), enriching the uterus' diet at this stage can have a beneficial effect on the health of the mother and newborn offspring. Manganese plays an important role in the functioning of the immune system: it participates in antioxidant processes, phagocytic activity, and maintaining the structural integrity of epithelial barriers that prevent the penetration of infectious agents. At the same time, manganese can have cardio- and hepatotoxic effects when ingested excessively. It was shown that the enrichment of the diet with organic manganese contributed to an increase in feed intake and improved the digestibility of dry matter in lambs [

54].

The authors of the study [

55] compared the effects of organic and inorganic manganese sources added to the lambs' diet (up to a total content of 150 mg Mn/kg) on the distribution of Mn, Cu and Zn in the contents of the rumen and the mucous membrane of the small intestine, and also determined its effect on the digestibility of nutrients in lambs. An identical diet was used, supplemented with manganese in a total concentration of up to 150 mg Mn/kg from manganese sulfate (MnSO

4) or from manganese chelate with glycine hydrate (MnGly). The results showed no differences between the sources of manganese in the diet, neither in the distribution of minerals in the mucous membrane of the small intestine and the contents of the scar, nor in total digestibility in the digestive tract, when the intake of manganese did not exceed the total content of 150 mg Mn/kg. However, the addition of manganese glycinate chelate to the diet improves the absorption of fiber and the use of manganese by scar bacteria in lambs [

55]. Experiments on sows conducted by Edmunds and colleagues (2022) showed that organic Mn improved the weight of newborns, accelerated growth before weaning, and reduced the level of fat in milk [

56]. Despite the fact that these are studies on pigs, the data obtained are important for sheep breeding, as they confirm the key role of Mn in ensuring the normal development of offspring. Additional information was obtained in the experiments of Zarghi et al. (2023) on laying hens, where organic forms of Mn provided better shell quality and productivity compared to Mn oxide [

57].

In general, the data indicate that manganese plays a critical role in sheep breeding in reproductive function and the exchange of trace elements in queens and lambs.

2.7. Cobalt

Cobalt is represented in 15 patents [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

20,

21] in the form of cobalt and cobalt chloride (CoCl₂·6H₂O). The doses range from 0.025–1.225 mg. The use of cobalt in ruminants is closely related to the synthesis of vitamin B₁₂ and the activation of metabolic processes. The role of cobalt and vitamin B₁₂ in the metabolism and maintenance of sheep health has been actively studied for several decades. In the work of Rothery et al. Using radiocobalt, it was shown that this trace element is actively distributed in the tissues and stomach contents of ruminants, confirming its key importance for the synthesis of cobalamin in the rumen [

58]. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that cobalt deficiency is accompanied by a decrease in the activity of B₁₂-dependent enzymes. Kennedy and colleagues [

59] found that lambs with Co–B₁₂ deficiency have decreased activity of methionine synthase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which leads to accumulation of methylmalonic acid and formation of atypical fatty acids. At the same time, pronounced biochemical disorders are not always accompanied by clinical manifestations, which makes it difficult to diagnose based solely on the level of metabolites.

No less significant is the data confirming the immunomodulatory effect of cobalt. In a study by Vellema et al. Intrarumenal cobalt pellets, long-release boluses, were used to ensure a stable supply of Co to the scar. It has been shown that this method of replenishing cobalt enhances the cellular immune response after vaccination and reduces the parasitic load of nematodes, which emphasizes the important role of Co–vitamin B₁₂ status in the formation of immune resistance in sheep [

60].

Aliarabi, H. studied the effect of administration of a delayed-release bolus of zinc (Zn), selenium (Se) and cobalt (Co) at the end of pregnancy (6 weeks before lambing) on productivity and metabolic parameters in Mehraban sheep and their lambs before weaning. Seventy dry sheep 6 weeks before the expected lambing were randomly divided into two groups of 35 heads: (1) a control group and (2) a group receiving a prolonged-acting bolus. Sheep blood samples were taken 10 days before lambing, as well as on the 45th and 90th days after it; milk samples were taken on the 45th day of lactation. Lambs were bled on the 10th, 45th and 90th days of life. Body weight at birth and at the time of weaning, as well as average daily weight gain, were higher, while mortality and incidence of white muscle disease were lower in lambs from queens treated with bolus (P<0.05). Bolus administration increased the activity of alkaline phosphatase in serum and glutathione peroxidase in whole blood, as well as concentrations of Zn, Se, and vitamin B₁₂ in the blood plasma of sheep and their lambs (P<0.05). At the same time, the lambs from the experimental group had lower creatine phosphokinase activity (P<0.05). The concentration of T₃ in the blood serum of sheep and lambs treated with bolus was higher (P<0.05), while the level of T₄ was lower (P<0.05). Concentrations of Zn, Se, and vitamin B₁₂ in milk also increased significantly when using a bolus (P<0.05). Thus, the introduction of zinc, selenium and cobalt into the rumen in the form of a delayed-release bolus at the end of pregnancy improved the mineral status of sheep and their lambs before weaning and contributed to an increase in the lambs' body weight by the time of weaning [

61].

2.8. Magnesium

Magnesium was used in 2 patents in the form of magnesium sulfate and chloride in a dosage of 0.3–0.5%. H. Chester-Jones and co-authors studied the effect of high doses of magnesium in sheep, assessing digestibility, mineral metabolism, blood and tissue parameters. Six lambs received rations with MgO (0.2; 0.6; 1.2; 2.4% Mg), and complete excrement collection was performed. A diet with Mg up to 2.4% caused physiological disorders, changes in the digestibility and metabolism of Mg, Ca, and P, and increased accumulation of Mg in tissues, but without significant cellular damage. Prolonged consumption of Mg >1.2% may impair productivity; 0.6% reduces the use of certain nutrients; about 0.5% Mg is considered the safe limit. There were no typical signs of intoxication, but diarrhea was observed [

62].

The authors of the study found that sheep distinguish between Mg and P mineral supplements and change their preferences depending on their diet. Forty lambs were offered four sources of Mg and P (C-MgO, MgO, Mag33, and MGP), then divided into four groups with different levels of Mg and P in the diet, and the selection test was repeated 29 days later. Initially, sheep preferred Mag33 > C-MgO = MGP > MgO (P < 0.05); after deficiency, this trend generally continued, but with low supply, preference for compensating minerals increased. The concentrations of Mg and P in serum increased, and the choice of Mg supplements increased with a decrease in Mg in the blood. The preference also depended on the physical form — larger MgO particles were chosen more readily. The sheep's ability to differentiate additives allows for free access to them and to use their placement for a more even use of pastures [

63]. Samarin, A.A. and co-authors [

64] divided 18 Zandi lambs into three groups to evaluate the effectiveness of organic micronutrient supplements compared with inorganic ones. The control group received the basic ration, and the experimental groups received trace elements in organic or inorganic form (Zn, Mn, Cu, Co). Lambs in the experimental groups had higher dry matter intake, growth rates, and better feed conversion (P<0.05), while the basic biochemical parameters of blood did not differ significantly. Triglycerides were lower (P<0.01) and vitamin B12 levels were higher, especially when using organic supplements (P=0.04). In general, organic trace elements improved weight gain without affecting nutrient absorption and most blood parameters [

64].

2.9. Potassium, Sodium

Potassium and sodium are the main functional intracellular cations in mammals. The inclusion of these components is aimed at maintaining the acid-base balance and optimal functioning of the scar. Sodium is represented in 14 patents in the form of salts of sodium bicarbonate, sodium sulfate and sodium chloride. Potassium is found in 2 patents in the form of potassium sulfate and potassium iodide [

65].

Ruminants and other herbivores usually consume more potassium than required (usually up to 0.5% of the diet is sufficient), and are well adapted to its metabolism. Cations in the scar fluid significantly affect digestion; when sodium is deficient, potassium can partially replace it in saliva. Researchers C.J.C. Phillips and co-authors proposed a critical concentration of potassium in the diet for non-lactating Welsh mountain sheep [

66]. Potassium intake of more than 30 g/kg of dry matter causes hypomagnesemia and significantly reduces the absorption and retention of magnesium in sheep, and may also reduce the absorption of calcium. Lower potassium levels, on the contrary, reduce the calcium content in the intracellular fraction of the blood and increase the risk of hypocalcemia [

67]. C Lipecka and co-authors evaluated the productivity of sheep with high (HK) and low (LK) levels of potassium in the blood. Potassium was determined in 871 lambs and 312 sheep and distributed by phenotypes. The frequency of the KH gene was 0.427 in lambs and 0.540 in sheep. The five-month-old lambs had potassium levels of 30.5 mmol/L (HK) and 9.3 mmol/L (LK). Body weight in different age periods, as well as wool yield, did not differ significantly between the phenotypes. However, HK type sheep have significantly lower fertility and reproductive function. Thus, the critical level of potassium in the sheep diet is close to 30 g/kg of dry matter; deviations from this value increase the imbalance of Mg and Ca. High levels of potassium in the blood adversely affect reproductive performance [

68].

2.10. Other

In addition to the above-mentioned mineral elements, natural clays in the form of zeolite and bentonite are found in patent developments. Clays have a very developed surface and a negative charge, therefore they bind mycotoxins, heavy metals, ammonium compounds and other toxic metabolites [

69]. This reduces intoxication, improves liver health, immunity, and animal productivity.

Iodine is represented in two patent developments in the form of potassium iodide. Its use is due to the need to prevent iodine deficiency in pregnant queens and ensure the normal development and functional activity of the thyroid gland in lambs [

70,

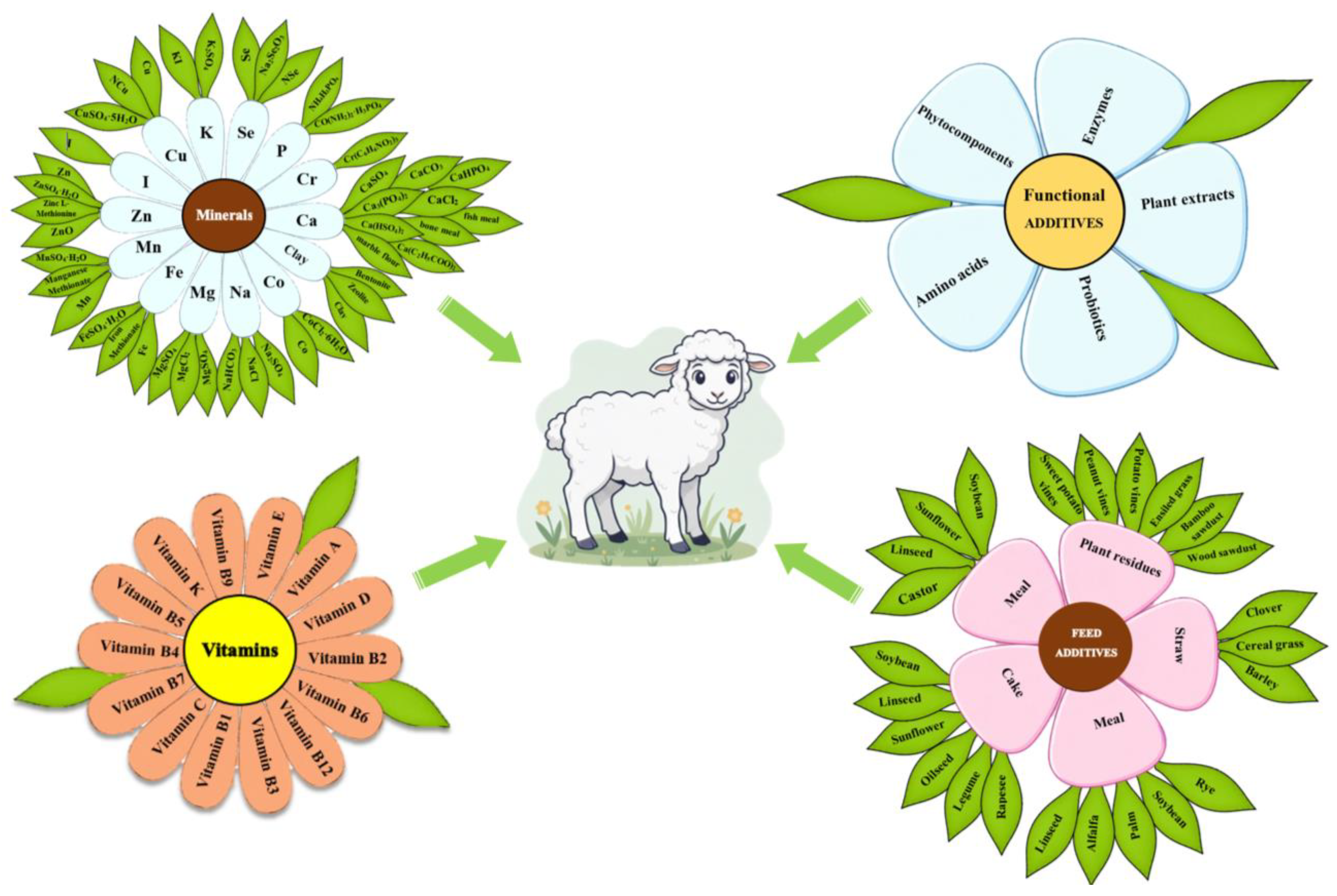

71]. The requirements for minerals and their functional effects are shown schematically in

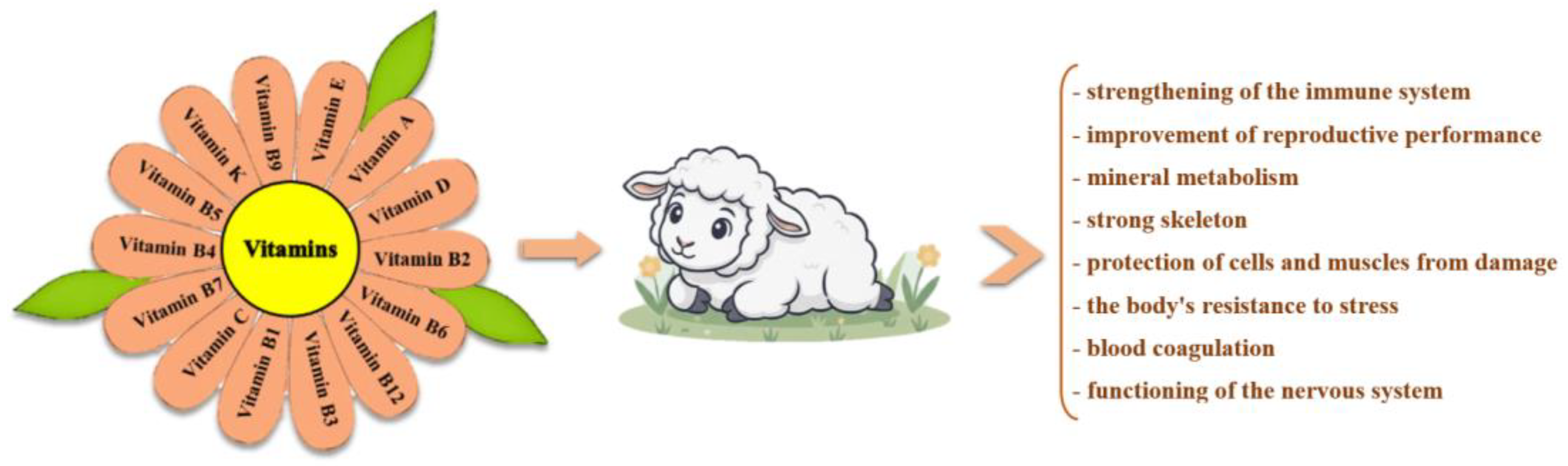

Figure 2.

Thus, in the patented mineral and vitamin complexes, macronutrients (calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, sodium), trace elements (selenium, iron, copper, zinc, manganese, cobalt, iodine and chromium) are most often found among minerals. Adding them to the mother's diet in late pregnancy improves the mineral status of sheep and their lambs before weaning and leads to an increase in the lambs' body weight at weaning.

3. Vitamins

3.1. Vitamins E, A, D

Vitamins E (14 times), A (12 times), and D (11 times) are most commonly used in the composition of the patented mineral and vitamin complexes analyzed. Hashem et al. (2016) showed that in Rahmani sheep, under conditions of summer heat stress, the administration of vitamins A or C improved hematological and reproductive parameters, increasing fertility and the level of steroid hormones [

84]. However, Raasch, Morrical, and Youngs (1998) found that parenteral administration of vitamins A and E in Suffolk and Hampshire sheep did not significantly increase fertility and embryo safety [

85]. This indicates that the effectiveness of vitamin supplements depends on the physiological status of animals, the conditions of their care and the timing of their use. Donnem et al. (2015) showed that supplementation with vitamin E reduces the frequency of stillbirths mainly in multiple ewes, whereas universal supplementation is not always effective [

86]. Similarly, Kott et al. (1998) found that vitamin E reduces the mortality of lambs during early lambing, but its effect is offset by late seasonal lambing [

87]. Awawdeh et al. (2019) showed that repeated injections of selenium and vitamin E in synchronized sheep increase the frequency of pregnancy and the effectiveness of the first mating [

88]. In more recent studies, Li et al. (2024) demonstrated that neonatal injections of vitamin A in sheep increase reproductive potential by stimulating spermatogenesis [

89]. Efe et al. (2023) showed that in deficient diets, the use of selenium and vitamins A, D, and E improves reproductive performance by performing a compensatory function, although the differences were not always statistically significant [

90].

Nemeth et al. (2017) showed that in lambs and goats, with a limited intake of vitamin D, UV-B radiation maintains an adequate level of 25(OH)D due to skin synthesis, partially compensating for its deficiency in the diet [

91]. There were no significant violations of mineral metabolism in the short term. Zhou et al. (2019) studied the relationship between the prenatal vitamin D status in ewes and reproductive performance in the Scottish Hills. Lleyn sheep have levels of 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D was higher than that of the Scottish Blackface, which the authors attribute to the breed features of skin pigmentation and the effectiveness of skin synthesis of vitamin D with limited ultraviolet radiation. Higher level 25(OH)D3 and total 25(OH)D before mating was positively associated with the weight of lambs at birth, but not with the number of lambs born or raised. The effect did not persist at subsequent stages of growth, which indicates the role of vitamin D mainly in the intrauterine development of the fetus, rather than in the regulation of fertility [

92]. Kohler et al. (2013) showed that an increase in the height of pastures and the intensity of UV-B radiation does not lead to a significant increase in vitamin D status in lactating sheep, which is associated with a low content of 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin and a predominant dependence on feed sources of vitamin D [

93]. Unlike sheep, goats use skin synthesis more effectively. Additionally, the mineral composition of Alpine feeds (high Ca and low P) influenced the parameters of mineral metabolism and limited the adaptation of bone tissue.

Taken together, the data indicate that the role of vitamin D in sheep is determined by a combination of factors: it affects the intrauterine development and weight of lambs at birth, but does not have a stable effect on fertility, and its status depends mainly on feeding and mineral balance, rather than on the level of ultraviolet radiation. This highlights the need for a comprehensive assessment of vitamin and mineral supply, taking into account the breed, housing conditions and the structure of the diet. In general, vitamins A and E are not an independent factor that automatically improves the reproductive performance of sheep, but they play an important role in maintaining a normal physiological state of the body. Their effectiveness depends on the initial availability of animals, the conditions of care and the timing of use: with a balanced diet, additional supplementation may be ineffective, whereas in conditions of deficiency it contributes to the preservation of pregnancy and reproductive stability. Thus, vitamins A and E should be considered as an element of an adapted and scientifically based feeding system, rather than a universal remedy.

3.2. B vitamins

Group B in mineral and vitamin complexes is represented in a wide range in the form of vitamins B1, B2, B3, B4, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12.

Asadi et al. (2024) proved that injection of the complex B vitamins (thiamine B₁, Riboflavin B₂, B₃ Niacin, Pantothenic acid B₅, B₆ pyridoxine, folate and cobalamin B₉ B₁₂) of goats before and after lambing increase their plasma concentration, improve feed intake, increase thyroid activity (increase T₃ and T₄) and humoral immunity (increase in IgG and IgM) with no signs of hepatotoxicity. At the same time, there was a higher glucose level and a decrease in insulin, which indicates a weakening of the negative energy balance during the transit period [

83].

Rickard and Elliot have indicated that the effectiveness of vitamin B₁₂ in sheep is determined not so much by the level of cobalt in the diet as by the biological activity of the synthesized forms of cobalamin. The introduction of the B₁₂ analogue (cobinamide) reduced the concentration of the active vitamin in the liver and disrupted propionate metabolism, despite the conditionally normal B₁₂ status. This indicates the presence of latent metabolic disorders and emphasizes that an increase in cobalt or the introduction of inactive B₁₂ analogues does not guarantee an improvement in energy metabolism [

84].

Two studies on lambs indicate limited efficacy of single injections of vitamin B₁₂ with normal cobalt supply. Mark et al. (1996) did not reveal the effect of subcutaneous cyancobalamin administration on weight gain and B₁₂-status indicators, which confirms the key role of cobalt and scar microbiota in endogenous vitamin synthesis [

85]. Gruner et al. (2009) showed low absorption of oral B₁₂ and rapid clearance after injection in pre-ruminant lambs, while the need for cobalamin remains low during the dairy period, but increases with the transition to coarse feed [

86]. Taken together, the data emphasize the expediency of prioritizing the diet with cobalt and avoiding single high-dose injections of B₁₂ in favor of a more uniform intake of B vitamins with control of methylmalonic acid as a functional marker of B₁₂ status [

83,

85,

86].

Modern data expand the understanding of the role of vitamin B₁₂ in productivity and reproduction. Moreover, Asadi et al. [

83] demonstrated that the administration of a complex of B vitamins, including B₁₂, to pregnant and lactating goats increased milk productivity, accelerated the growth of young animals and increased the level of immunoglobulins, emphasizing the importance of the mother's vitamin status for the health of offspring. Marca et al. stated that a single administration of cyancobalamin to newborn lambs did not affect weight gain and hematological parameters, which indicates that there was no effect in the absence of an initial deficiency [

85]. Similarly, Gruner et al. found that in young animals, vitamin B₁₂ is poorly retained in the body and is rapidly excreted even after injections, which emphasizes the need for regular and long-term replenishment in the presence of a real deficiency [

86].

3.3. Vitamin K

In the patented MVC, vitamin K is used only 2 times. Vitamin K plays a key role in bone mineralization, participating in the activation of calcium-binding proteins, primarily osteocalcin. When it is deficient, the mineralization of the bone matrix slows down, which leads to a decrease in bone strength and an increased risk of deformities [

87]. Experimental data from Roy & Lall (2007) depicts that vitamin K deficiency is accompanied by a decrease in mineral density and a violation of bone structure, which suggests a similar decrease in the efficiency of calcium and phosphorus use in sheep with a deficiency of this vitamin [

87].

A congenital defect of the blood coagulation system in Rambouillet lambs was described, accompanied by massive bleeding and high neonatal mortality [

88]. In the affected animals, there was a sharp decrease in the activity of vitamin-K-dependent coagulation factors (II, VII, IX, X) and proteins C and S with the remaining factors remaining active, indicating a violation of γ-carboxylation. The absence of vitamin K antagonists and only a short-term effect of its administration indicate a genetically determined defect in vitamin K metabolism or the activity of gamma-glutamyl carboxylase. Pedigree analysis confirmed an autosomal recessive type of inheritance, in which clinical manifestations occur only in homozygous lambs, while carriers remain clinically healthy, which creates a risk of latent spread of the defect in the herd. In general, the work emphasizes that vitamin-K-dependent disorders in sheep can be caused not only by the level of vitamin intake, but also by genetic failures of its activation, which is important to consider when analyzing the causes of neonatal mortality and evaluating the effectiveness of vitamin supplements in breeding farms.

In an embryotechnological study by Sefid et al. (2017) showed that the addition of vitamin K₂ to the in vitro sheep embryo culture medium after genome activation increased the compactification, yield of blastocysts and their quality at an optimal concentration of 0.1 mM [

89]. The improvements were accompanied by a decrease in oxidative stress, an increase in the number of cells, and increased expression of genes related to mitochondrial function. The most pronounced protective effect during vitrification was observed in the presence of vitamin K both before freezing and after thawing, which indicates the need for continuous embryo support.

The data obtained confirm the involvement of vitamin K in the regulation of mitochondrial activity and oxidative balance in the early stages of embryonic development, however, the in vitro results cannot be directly extrapolated to the conditions of sheep feeding and require further applied research. The functional properties of vitamins are presented in

Figure 3.

Therefore, an analysis of the literature shows that vitamins A, D, E, groups B and K play an important but ambiguous role in the reproductive function, growth and metabolic stability of sheep. Their effect is not universal and is largely determined by the initial availability of animals, breed characteristics, physiological condition, housing conditions and the structure of the diet. Vitamins A and E perform supportive and compensatory functions to the greatest extent: in case of deficient diets or stressful conditions (heat stress, early lamentation, multiple pregnancy) They contribute to maintaining pregnancy, reducing neonatal mortality, and maintaining hormonal balance, whereas with proper feeding, additional supplementation often does not lead to statistically significant improvements. Vitamin D in sheep is more associated with intrauterine development and the weight of lambs at birth than with fertility, and its status is determined mainly by feed sources and mineral balance, rather than the level of UV radiation. B vitamins, primarily B₁₂, are closely related to the availability of cobalt and the activity of the scar microbiota. Single injections of B₁₂ in the absence of deficiency are usually ineffective, whereas a comprehensive and uniform supply of B vitamins during the transit period improves energy metabolism, immune status and productivity. This highlights the need for a functional assessment of B₁₂ status and priority control of cobalt in the diet. Vitamin K is used in mineral and vitamin complexes to a limited extent, but evidence suggests its importance for bone mineralization, the blood coagulation system, and early embryonic development.

4. Functional Additives

An analysis of the composition of the patented mineral and vitamin complexes shows that some of them are focused on extended biological effects by including plant extracts and phytocomponents. Moreover, their greatest diversity (7-11 components) is typical for individual Chinese patents (CN106509404, CN110742181, CN104171716). At the same time, feed antibiotics (monenzine sodium and bacitracin zinc) are used in a number of MVCs, the use of which is regulated by national regulations and prohibited in EU countries [

90,

91]. This highlights the pronounced regional differences in approaches to the formation of feed additives and indicates the need to take into account regulatory constraints and potential risks when assessing the practical applicability and prospects for the introduction of such complexes.

Probiotics and prebiotics were included in seven MVCs to improve intestinal function. Experimental data confirm the possibility of using probiotics and functional feed additives in ruminant diets as an alternative to antibiotics [

92,

93]. The addition of Bacillus subtilis (strain C-3102) to lambs' diets enhances fiber fermentation, microbial protein synthesis, and optimizes the profile of volatile fatty acids, providing an increase in body weight without increasing feed intake [

92]. Probiotic compositions based on Bacillus licheniformis and Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrate efficacy comparable to moniensin, improving feed gains and conversion, as well as the hormonal and antioxidant status of animals [

93]. Additional studies have shown that probiotics have a positive effect on intestinal morphology, amino acid and vitamin metabolism, immune functions, and microbiocenosis, contributing to improved metabolic processes and productivity [

94,

95]. At the same time, the effectiveness of herbal and functional supplements depends on the dosage, strain composition and type of diet, and in some cases may be accompanied by a decrease in digestibility, which emphasizes the need for their scientifically based optimization in practical use [

96].

In the analyzed patents, amino acid additives are presented in CN106509404, CN101171955, CN110742181, CN104322884 and CN104171716. The results of a number of studies emphasize the key role of methionine and lysine as limiting amino acids in the diets of sheep and lambs [

97]. So, Angeles-Hernandez et al. (2025) showed that the addition of 6 g/day of scar-protected methionine to mixed sheep increases milk yield, as well as milk protein and lactose yield, while maintaining stable fat content and yield [

98]. Similar results were obtained by Grassi et al. (2024): the use of a combined lysine and methionine supplement in Komizan sheep was accompanied by an increase in milk yield and casein content, and lambs at suckling were characterized by higher growth rates, indicating an increase in the biological value of milk protein [

99].

At the same time, a number of studies have noted a decrease in the antioxidant potential of milk (according to FRAP and ABTS indicators), which indicates an ambiguous effect of amino acid supplementation on the oxidative properties of the product [

97,

100]. In the experiment, Araújo et al. (2019) the use of scar-protected amino acids in lambs increased the consumption of dry matter and nitrogen retention without changing digestibility, however, it was accompanied by an increase in nitrogen excretion in urine, indicating an additional energy load associated with its utilization [

97]. A new aspect is presented in the study by Zhang et al. (2025), where, against the background of a low-protein diet, the optimal ratio of lysine and methionine 1:1 enhanced the morphological development of the small intestine, improved the barrier and antioxidant properties of enterocytes, increased the activity of digestive enzymes and contributed to the restructuring of the microbiota towards beneficial taxa, accompanied by activation of energy metabolism along the pathways of coenzyme A and the tricarboxylic acid cycle [

100]. Taken together, the data indicate that accurate balancing of lysine and methionine, both in dose and ratio, can increase productivity, improve nitrogen utilization, and maintain intestinal and juvenile health. However, the issues of optimal levels of supplementation and possible effects on the antioxidant properties of milk remain open and require further research.

Yeast is found as functional additives in mineral and vitamin complexes (3 times), single patents include Rumensin, Pfanstiehl, Aminophylline, Mercaptamine, glycoconjugate, urease inhibitor and protein.

Functional additives such as probiotics, amino acids, enzymes, plant extracts and phytocomponents are widely used in feed additives for sheep and lambs. They not only improve the digestibility of feed and the bioavailability of minerals, but also stimulate the immune system, increase the resistance of animals to stress and diseases [

96,

101]. Functional supplements affect the microbiota by improving the absorption of vitamins and minerals.

5. Feed Additives

In the patented mineral and vitamin complexes, about a quarter of the composition is accounted for by feed additives. More than half of the patents use various fractions of corn and wheat, including flour, straw, cake and silage cake. A significant proportion of straw from various crops (clover, grasses, barley) is noted in nine patents. Oilcakes (soy, linseed, sunflower, oilseed, legume, rapeseed) are also included in the nine MVCs both as components of individual plants and in the form of combined sources. Plant residues (sweet potato tops, peanuts and potatoes, silage grass, bamboo sawdust and sawdust) are included in the composition of eight patented MVCs. In addition, meal products (flax, soy, sunflower, and detoxified castor meal) are widely used as feed components. Combinations of vegetable flours (flax, alfalfa, palm, as well as rye and soy flour) are presented in four patents. Similarly, rice husk powder and rice bran are used as part of four mineral and vitamin complexes.

6. Conclusions

23 patented mineral and vitamin complexes (MVCs) intended for inclusion in the diets of dry sheep and lambs were analyzed. All components are conventionally grouped into four categories: minerals, vitamins, functional and feed additives. The mineral part of the MVC includes both macro- and microelements and reflects an approach in which such complexes are considered not only as an additive to the diet, but also as a tool for managing productivity, reproduction and animal resistance (

Figure 4).

Calcium forms the basis of the mineral status, affecting not only bone homeostasis, but also the microbiota, immune responses, and development of young animals; its optimal levels are determined by the physiological state of the animals and their ratios to phosphorus and magnesium. Zinc acts as a multifunctional regulator of growth, antioxidant protection, epithelial barrier and reproductive processes.; Its effectiveness depends on the form of administration and antagonistic interactions, primarily with copper and phytates, while organic and nanostructured forms can increase bioavailability and reduce environmental stress. Other trace elements perform complementary but critically important functions: iron provides hematopoiesis and antioxidant resistance of young animals; copper participates in the work of enzyme systems and immunity, but requires strict dosage control; manganese is important for reproduction and mineralization; Cobalt, through vitamin B₁₂, supports the energy metabolism of propionate; iodine regulates thyroid status; selenium in combination with vitamin E reduces the effects of oxidative and thermal stress.

The form of mineral additives (organic or inorganic) of selenium, zinc, copper and manganese had no effect on their distribution and total concentrations in sheep excrement. At the same time, the level of supplementation changed the flow of selenium and improved phosphorus retention, and the revealed differences in the hard-to-decompose fractions of micronutrients indicate possible environmental effects that require further study.

The vitamin component of MVC is represented by a wide range of vitamins (A, D, E, groups B, K and C), which enhance the effect of mineral components, but their effectiveness is maximal when used appropriately, taking into account the availability of the herd, the season and the level of stress load.

The form of mineral additives (organic or inorganic) of selenium, zinc, copper and manganese in sheep had no effect on the distribution and total concentrations of micronutrients in excrement. At the same time, the level of supplementation changed the selenium flux and increased phosphorus retention, and the revealed differences in the difficult-to-decompose fractions of elements indicate potential environmental effects. The analysis of the patent documentation revealed a trend of transition from traditional mineral salts (CaHPO₄, ZnSO₄, etc.) to organic chelated forms (methionates) and nanostructured compounds (nanomedium, nanosilicon). In parallel, there is a shift from the use of antibiotics to functional feed additives, including probiotics, enzymes, amino acids, and phytocomponents. Such approaches are aimed at increasing the bioavailability of nutrients, reducing the need for high doses of inorganic salts and reducing the environmental burden.

Providing animals with nutrients during pregnancy affects not only the condition of the mother and reproductive function, but also the health of the offspring. In general, vitamins should be considered not as an independent factor in improving reproductive performance, but as an element of an adapted, scientifically based vitamin and mineral supply system, the effectiveness of which is determined by the actual deficiency, the physiological status of animals and the interaction with mineral metabolism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K. and S.B.; methodology, S.B. and T.K.; validation, A.O., S.B. and A.S.; formal analysis, T.K.; investigation, S.B.; resources, Zh.M. and S.B.; data curation, S.B. and I.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B. and A.S.; writing—review and editing, I.K.; visualization, A.O. ; supervision, I.K.; project administration, I.K.; funding acquisition, I.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.:

Funding

“This research was funded by the Abai Kazakh National Pedagogical University under project “Development of a recipe for a vitamin and mineral complex for pregnant ewes and lambs based on domestic raw materials” (contract #51 dated 05.04.2025)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data confirming the research data can be provided by the author for correspondence upon reasonable request. Public access to the data is restricted for correct use and interpretation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MVC |

Mineral and Vitamin Complex |

| WIPO |

World Intellectual Property Organization |

| FRAP |

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power |

| NRC |

National Research Council |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| ABTS |

2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

References

-

China Patent CN110754564A; Special feed for improving rapid development of black-bone sheep and preparation method thereof, published 7 February 2020.

-

China Patent CN110742182A; Special feed for increasing individual size of black-bone sheep and preparation method thereof, published 4 February 2020.

-

China Patent CN104719682A; Composite nutritional lick brick for Tibetan sheep and preparation method thereof, published 2015.

-

China Patent CN108065064A; Feed for meat sheep, published 2018.

-

China Patent CN108065063A; Special feed for mutton sheep, published 2018.

-

China Patent CN110663809A; Special feed for improving growth speed of black-bone sheep and preparation method thereof, published 2020.

-

China Patent CN110742175A; Special feed for improving health care value of black-bone sheep and preparation method thereof, published 2020.

-

China Patent CN108185175A; Safe and efficient feed additive for rearing and fattening meat sheep and application method thereof, published 2018.

-

China Patent CN106509404A; Feed for meat sheep fattening, published 2017.

-

China Patent CN117837688A; Special nutrition lick brick for cattle, horses, camels, sheep, donkeys and deer and production method thereof, published 2024.

-

China Patent CN112841425A; Feed additive for stimulating growth and rapid weight gain in sheep, published 2021.

-

China Patent CN102742737B; Selenium-enriched complete feed for sheep fattening and preparation method thereof, published 2013.

-

China Patent CN101171955A; Premix for meat sheep breeding, published 2006.

-

China Patent CN110742181A; Formula and preparation method of pelleted feed for breeding black-bone sheep, published 2019.

-

China Patent CN109418565A; Mixed feed for cattle and sheep, published 2019.

-

China Patent CN101077125A; Concentrated feed additive formula for beef cattle and meat sheep, published 2006.

-

China Patent CN107467381A; Method for producing feed and fattening high-quality fine- and dense-wool sheep, published 2017.

-

China Patent CN106509387A; Fattening feed for goats, published 2017.

-

China Patent CN104322884A; Concentrated feed for sheep fattening, published 2015.

-

China Patent CN116616378A; Feed for fattening cattle and sheep, published 2023.

-

China Patent CN104171716A; Feed additive for improving immunity and fattening meat sheep and preparation method thereof, published 2014.

-

China Patent CN101077134A; Concentrated feed for beef cattle and meat sheep, published 2006.

-

China Patent CN108419923A; Compound feed for sheep containing traditional Chinese medicine components, published 2018.

- Shkembi, B.; Huppertz, T. Calcium absorption from food products: Food matrix effects. Nutrients 2022, 14, Article 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugger, D.; Liesegang, A. Antepartum high dietary supply of calcium affects bone homeostasis and offspring growth in dairy sheep and dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 5786–5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, G.D. Calcium and phosphorus requirements of the ewe during pregnancy and lactation. Br. J. Nutr. 1983, 50, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; et al. Calcium requirement of Yunnan semi-fine wool rams (Ovis aries) based on growth performance, calcium utilization, and selected serum biochemical indexes. Animals 2024, 14(11), Article 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataollahi, F.; Friend, M.; McGrath, S.; Dutton, G.; Peters, A.; Bhanugopan, M. Maternal supplementation of twin-bearing ewes with calcium and magnesium alters immune status and weight gain of their lambs. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2020, 9, 100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.M. The effect of high calcium intake by pregnant Awassi ewes at late gestation on minerals status and performance of ewes and newborn lambs. Livest. Sci. 2008, 117, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; et al. Hindgut microbiota profiling and functional prediction of sheep (Ovis aries) fed with different dietary calcium levels. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, Article 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, S.J.; Anchordoquy, J.M.; de Matos, D.G.; Anchordoquy, J.P.; Seoane, A.; Mattioli, G.A.; Errecalde, A.L.; Furnus, C.C. Effect of increasing zinc sulphate concentration during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. Theriogenology 2010, 74, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Meng, L.; Zhang, R.; Tong, M.; Qi, Z.; Mi, L. Effects of essential mineral elements deficiency and supplementation on serum mineral elements concentration and biochemical parameters in grazing Mongolian sheep. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, Article 1214346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellof, G.; Most, E.; Pallauf, J. Concentration of copper, iron, manganese and zinc in muscle, fat and bone tissue of lambs of the breed German Merino Landsheep in the course of the growing period and different feeding intensities. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2007, 91, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijani, K.; Rezaei, J.; Rouzbehan, Y. Effect of nano-ZnO, compared to ZnO and Zn-methionine, on performance, nutrient status, rumen fermentation, blood enzymes, ferric reducing antioxidant power and immunoglobulin G in sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 267, 114532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Maya, M.A.; Domínguez-Vara, I.A.; Trujillo-Gutiérrez, D.; Morales-Almaráz, E.; Sánchez-Torres, J.E.; Bórquez-Gastelum, J.L.; Acosta-Dibarrat, J.; Grageola-Nuñez, F.; Rodríguez-Carpena, J.G. Growth performance and meat quality of lambs supplemented with zinc methionine or zinc oxide. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 99, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anam, M.S.; Astuti, A.; Widyobroto, B.P.; Agus, A. Effect of dietary supplementation with zinc-methionine on ruminal enzyme activities, fermentation characteristics, methane production, and nutrient digestibility: An in vitro study. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2023, 10, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, F.; Degen, A.; Sun, P. The effects of zinc supplementation on growth, diarrhea, antioxidant capacity, and immune function in Holstein dairy calves Animals 2023. CrossRef 13, Article 2493.

- Grešáková, L'.; Tokarčíková, K. Bioavailability of dietary zinc sources and their effect on mineral and antioxidant status in lambs. Agriculture 2021, 11, Article 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, D.L.; Miller, W.J.; Neathery, M.W.; Kincaid, R.L.; Blackmon, D.M.; Gentry, R.P. Absorption of zinc from small and large intestine of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 1976, 59, 1963–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Xiong, D.; Long, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles as next-generation feed additives: bridging antimicrobial efficacy, growth promotion, and sustainable strategies in animal nutrition. Animals Review Article 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampidis, V.; et al. Assessment of zinc chloride hydroxide monohydrate as feed additive. EFSA J. 2023, 21, Article 8458. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Yan, Y.; Tan, Z.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Simonkolleite coating on poly(amino acids) to improve osteogenesis. Polymers 2019, 11, Article 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.V.M.; Callan, R.J. Selenium and vitamin E. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2001, 17, 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Shakirullah; Qureshi, M.S.; Akhtar, S.; Khan, R.U. The effect of vitamin E and selenium on physiological, hormonal and antioxidant status of Damani and Balkhi sheep submitted to heat stress. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2017, 60, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Celi, P.; Leury, B.J.; Dunshea, F.R. High dietary selenium and vitamin E supplementation ameliorates the impacts of heat load on oxidative status and acid-base balance in sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 3342–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: sheep, goats, cervids, and New World camelids; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, S.I.; Bitto, I.I.; Ayoade, J.A.; Oyedipe, O.E. Effects of vitamin E and selenium on fertility and lamb performance of Yankasa sheep. Open J. Vet. Med. 2018, 8, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Toghdory, A.; Hatami, M.; Nejad, J.G. Milk supplemented with organic iron improves performance, blood hematology, iron metabolism parameters, biochemical and immunological parameters in suckling Dalagh lambs. Animals 2022, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Zhang, C.; Ji, P.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Pan, H.; An, Q. Effects of different iron supplements on reproductive performance and antioxidant capacity of pregnant sows as well as iron content and antioxidant gene expression in newborn piglets. Animals 2023, 13, Article 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttle, N.F. Mineral Nutrition of Livestock, 4th ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.J.; Gan, S.Q.; Shen, X.Y. Effects of nano-copper poisoning on immune and antioxidant function in the Wumeng semi-fine wool sheep. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 199, 2919–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, H. Copper deficiency: a review of the economic cost and current constraints to effective management of copper deficiency in southern Australian sheep flocks. Agric. Rev. 2021, 1, 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Senthilkumar, P.; Nagalakshmi, D.; Ramana Reddy, Y.; Sudhakar, K. Effect of different level and source of copper supplementation on immune response and copper dependent enzyme activity in lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2009, 41, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidiroglou, M.; Ho, S.K.; Standish, J.F. Effects of dietary manganese levels on reproductive performance of ewes and on tissue mineral composition of ewes and day-old lambs. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1978, 58, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, M.; Toghdori, A.; Ghoorchi, T.; Hatami, M. Influence of organic manganese supplementation on performance, digestibility, milk yield and composition of Afshari ewes in the transition period, and the health of their lambs. Anim. Prod. Res. 2023, 12, 1752. [Google Scholar]

- Gresakova, L.; Venglovska, K.; Cobanova, K. Nutrient digestibility in lambs supplemented with different dietary manganese sources. Livest. Sci. 2018, 214, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, C.E.; Cornelison, A.S.; Farmer, C.; Rapp, C.; Ryman, V.E.; Schweer, W.P.; Wilson, M.E.; Dove, C.R. The effect of increasing dietary manganese from an organic source on the reproductive performance of sows. Agriculture 2022, 12, Article 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghi, H.; Hassanabadi, A.; Barzegar, N. Effect of organic and inorganic manganese supplementation on performance and eggshell quality in aged laying hens. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eotheey, P.; Bell, J.M.; Spinks, J.W.T. Cobalt and vitamin B12 in sheep. I. Distribution of radiocobaltin in tissues and ingesta. J. Agric. Sci. 1952, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, D.G.; Kennedy, S.; Blanchflower, W.J.; Scott, J.M.; Weir, D.G.; Molloy, A.M.; Young, P.B. Cobalt–vitamin B12 deficiency causes accumulation of odd-numbered, branched-chain fatty acids in the tissues of sheep. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 71, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellema, P.; Rutten, V.P.M.G.; Hoek, A.; Moll, L.; Wentink, G.H. The effect of cobalt supplementation on the immune response in vitamin B12-deficient Texel lambs. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1996, 55, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliarabi, H.; Fadayifar, A.; Alimohamady, R.; Dezfoulian, A.H. The effect of maternal supplementation of zinc, selenium, and cobalt as slow-release ruminal bolus in late pregnancy on some blood metabolites and performance of ewes and their lambs. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2018, 186, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chester-Jones, J.H.; Fontenot, J.P.; Veit, H.P.; Webb, K.E. Physiological effects of feeding high levels of magnesium to sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 1989, 67, 1070–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedernera, M.; Mereu, A.; Villalba, J.J. Preference for inorganic sources of magnesium and phosphorus in sheep as a function of need. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, Article skab010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdian, A.; Norouzian, M.A.; Afzalzadeh, A. Effect of trace mineral source on biochemical and hematological parameters, digestibility, and performance in growing lambs. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022, 54, Article 42. [Google Scholar]

- Ellory, J.C.; Tucker, E.M. Stimulation of the potassium transport system in low potassium type sheep red cells by a specific antigen–antibody reaction. Nature 1969, 222, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, G.M. Potassium metabolism of domestic ruminants: a review. J. Dairy Sci. 1966, 49, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, C.J.C.; Mohamed, M.O.; Chiy, P.C. The critical dietary potassium concentration for induction of mineral disorders in non-lactating Welsh Mountain sheep. Small Rumin. Res. 2006, 63, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipecka, C.; Pięta, M.; Gruszecki, T. The potassium level in the blood of sheep and their productivity. Anim. Feed Sci. 1994, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kicheeva, A.G.; Tereshchenko, V.A. Prospects for the use of natural clay minerals in animal husbandry (review). Agrar. Sci. J. 2021, 12, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, V.; Opheim, M.; Sandvik, J.T.; Aasen, I.M. Iodine intake and excretion from sheep supplemented with macroalgae (Laminaria hyperborea) by-product. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1213890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizhova, L.N.; Sharko, G.N.; Mikhaylenko, A.K.; Chotchaeva, Ch.B. Metabolic and immunological profile of sheep in conditions of iodine deficiency. South Russ. Dev. 2019, 14, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, N.M.; Abd-Elrazek, D.; Abo-Elezz, Z.R.; Latif, M.G.A. Effect of vitamin A or C on physiological and reproductive response of Rahmani ewes during subtropical summer breeding season. Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 144, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raasch, G.A.; Morrical, D.G.; Youngs, C.R. Effect of supplemental vitamin E and A on reproductive performance and serological profiles of ewes managed in drylot. Sheep Res. J. 1997, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar]