1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are long-term conditions arising from a combination of genetic, physiological, environmental, and behavioral factors and account for the majority of global mortality, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [

1]. Chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, and other long-standing conditions not only affect patients but also impose profound and persistent demands on their families and informal caregivers [

2]. As populations age and the burden of NCDs rises, health systems increasingly depend on family members to provide ongoing care, often with limited formal support [

3].

Family caregivers play a central role in assisting with daily activities, treatment adherence, symptom monitoring, and emotional support, but this role is frequently accompanied by substantial emotional, physical, social, and financial strain. Numerous studies report high levels of caregiver burden, including stress, depression, sleep disturbance, fatigue, and neglect of caregivers’ own health, alongside disruptions in employment, income, and social relationships [

3,

4]. Recent evidence from Saudi Arabia and other settings shows that caregivers of patients with chronic diseases experience compromised quality of life (QOL), with burden influenced by disease severity, caregiving intensity, socioeconomic status, and availability of support services [

5]. Systematic reviews and recent empirical studies further highlight that high caregiver burden is associated with poorer mental health, reduced life satisfaction, and increased risk of physical health problems among caregivers themselves [

6].

In Saudi Arabia, strong family values and expectations of family-based care mean that relatives frequently assume primary caregiving responsibilities for individuals with chronic illnesses, often without adequate training, respite, or financial and psychosocial support [

7]. While several local studies have examined caregiver burden and QOL in specific conditions, such as cancer, neurological disorders, or disability, there remains limited evidence addressing the broader impact of caring for family members with diverse chronic illnesses across multiple specialties [

8]. Understanding how chronic disease affects the emotional, physical, social, and financial well-being of family members is crucial for informing culturally appropriate interventions, guiding resource allocation, and shaping policies that protect and enhance caregiver QOL [

9].

The present study aims to explore the impact of chronic illness on family members living with affected patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and to assess the main emotional, physical, social, and financial challenges they face. By focusing on caregivers across a range of chronic conditions, this work seeks to provide evidence that can support the development of targeted support systems and health policies that recognize and respond to the needs of families caring for individuals with chronic disease.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design and Setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, to assess the quality of life and the emotional, physical, social, and financial burden experienced by family members of individuals with chronic illnesses.

2.2. Study Population

The study included adult residents of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, recruited regardless of caregiving status. Participants comprised individuals with and without family members diagnosed with chronic illnesses. Subgroup analyses were conducted among participants who reported having a chronically ill family member and those providing direct caregiving. Individuals younger than 18 years of age and those not residing in Riyadh were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

In the absence of prior local studies estimating the burden among family members of patients with chronic illnesses, the prevalence was assumed to be 50%. Based on this assumption, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 377 participants. This number was adjusted for a design effect of 1.5 and a non-response rate of 10%, resulting in a final sample size of 565 participants. A community-based convenience sampling approach was used. Participants were recruited from major shopping malls across different geographical regions of Riyadh (north, south, east, west, and central) to enhance the diversity of the study population.

2.4. Data Collection Tool and Measurement

Data were collected using a pre-tested, self-administered questionnaire developed based on an extensive review of the literature on caregiver burden and quality of life among family members of patients with chronic illnesses. The questionnaire assessed sociodemographic characteristics, caregiving roles, knowledge and awareness of chronic illness, and the emotional, physical, social, and financial impact of caregiving. Questionnaire items were adapted from previously published studies that examined caregiver burden, psychosocial impact, and quality of life in both regional and international settings [

3,

5,

6].

Knowledge and awareness regarding chronic illness were assessed using a set of structured questions. Correct responses were summed to generate a total knowledge score, which was converted into a percentage. A cut-off point of 60% was used to categorize participants as having adequate (≥60%) or inadequate (<60%) knowledge. This cut-off was selected in accordance with methods used in similar population-based and caregiver studies. Attitudes toward chronic illness and caregiving were assessed using Likert-scale items reflecting participants’ perceptions, emotional responses, caregiving experiences, and the perceived impact of chronic illness on daily life and family dynamics. Quality of life was categorized as good, moderate, or poor based on responses across emotional, physical, social, and financial domains according to the same described above cut-off threshold.

2.5. Operational Definition

Chronic illness was defined according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a condition lasting one year or more that requires ongoing medical care and/or limits activities of daily living.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges, were used to summarize participant characteristics and study variables. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality of all collected data was strictly maintained. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of AlMaarefa University (IRB No. IRB24-096).

3. Results

A total of 565 participants were included in the study. The median age of participants was 27 years (interquartile range: 21–43 years). The majority were female (73.5%), Saudi nationals (85.2%), and had attained a university-level education (58.7%). Nearly half of the participants reported a monthly income of 5,000 Saudi Riyals or less (46.9%). (

Table 1).

3.1. Prevalence of Chronic Illness and Caregiving Status

Among all participants, 70.9% reported having at least one family member diagnosed with a chronic illness. The most reported number of affected family members was one (44.3%), followed by two (26.1%) and three or more (25.5%). Regarding caregiving roles, 37.3% of participants identified themselves as caregivers for a chronically ill family member, while 62.7% reported no direct caregiving role (

Table 2).

3.2. Psychological and Emotional Impact of Caregiving

Caregivers reported a high prevalence of psychological and emotional challenges. Anxiety related to a family member’s chronic illness was reported by 82.2% of caregivers. Depressive symptoms were reported by 27.3%, feelings of isolation by 23.0%, and hopelessness by 9.8%. Additionally, 70.9% of caregivers reported that they had learned medical or caregiving-related skills to support their affected family members (

Table 3).

3.3. Physical Health Impact on Caregivers

Physical health effects associated with caregiving were commonly reported. Sleep disturbances were reported by 57.1% of caregivers, while 35.4% reported experiencing fatigue. Neglect of personal health due to caregiving responsibilities was reported by 33.1% of caregivers. Overall, 33.5% indicated that caregiving had a negative impact on their physical health (

Table 4).

3.4. Financial Impact of Chronic Illness Care

Financial burden was a prominent concern among caregivers. Treatment-related costs were reported as a financial burden by 40.5% of respondents. More than half of caregivers (59.1%) reported that caregiving had a direct effect on their personal finances. Additionally, 19.6% reported an impact on overall family income, while 17.8% reported increased family needs related to chronic illness (

Table 5).

3.5. Challenges Associated with Caregiving

The most reported caregiving challenges included financial strain (52.9%), meeting the ongoing needs of the patient (38.1%), and coping with stress (41.3%). A small proportion of participants (2.6%) reported other challenges related to caregiving (

Table 6).

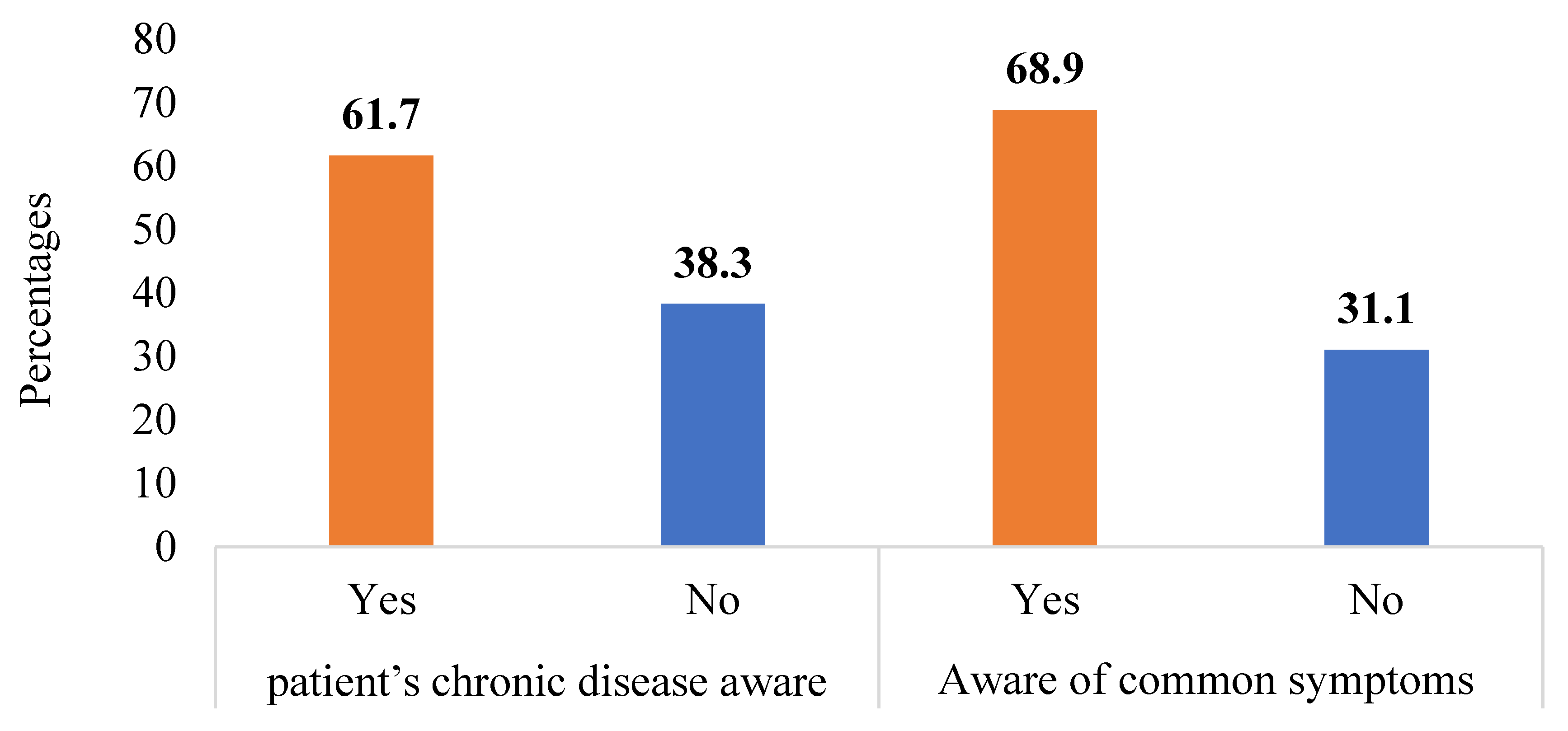

Figure 1 examines caregivers’ knowledge about chronic illnesses. A majority (61.7%) are aware of the patient’s chronic disease and management, and 68.9% know common symptoms associated with conditions like diabetes, asthma, PCOS, and cancer.

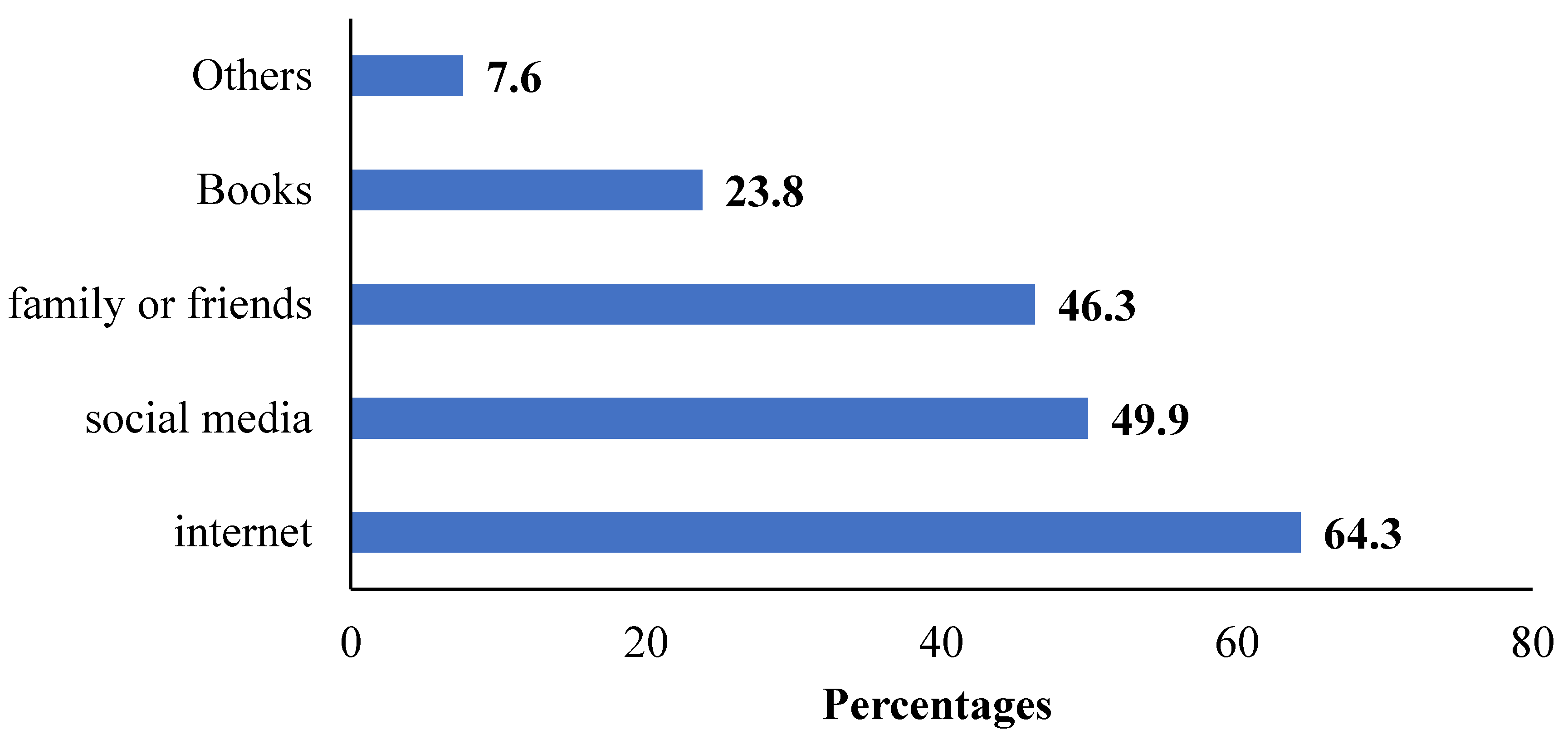

The internet is a key information source for 64.3% of respondents, followed by social media (49.9%) and family or friends (46.3%). Books and other sources were less commonly used, with only 23.8% and 7.6% relying on them, respectively (

Figure 2).

3.6. Supplementary Findings

Additional findings related to disease-specific characteristics, caregiver knowledge and attitudes, social impact, and support systems are presented in the supplementary material.

4. Discussion

The study examines the effects of chronic illness on family members who serve as primary caregivers, highlighting emotional, physical, and financial challenges. Conducted in Riyadh with 565 participants, it found that 70.9% had relatives with chronic conditions, primarily diabetes and asthma. Caregivers reported high levels of anxiety and perceived the illnesses as permanent. Although financial strain was significant, loss of income was less common. The study concludes that caregivers face emotional and financial burdens, often without sufficient support, and recommends enhanced mental health resources and financial assistance to improve their well-being.

A recent study found by Huayan Lin (2024) 30 detailed examination of demographic characteristics in research, highlighting the significance of age, gender, cultural background, education, and marital status in shaping study outcomes. It notes the predominance of younger female participants and discusses how cultural diversity can influence responses and generalizability [

10,

11]. The authors assert that higher educational attainment correlates with better health knowledge and behaviors, while marital status affects social support networks, thereby influencing individual well-being [

9].

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants

A study done by Ahmed H. et al. (2020) elucidates significant deficiencies in public awareness regarding chronic illnesses, particularly cardiovascular diseases, while emphasizing the necessity for targeted educational interventions [

12]. This observation is corroborated by our findings, which indicate that 61.7% of caregivers possess awareness of their loved ones’ chronic conditions and management strategies. Another evident correlation between caregiver awareness and the effectiveness of caregiving suggests that informed caregivers are better positioned to provide adequate support and advocate for their patients, thereby enhancing health outcomes [

13]. Both studies highlight the critical role of educational initiatives aimed at improving caregiver knowledge and fostering greater public understanding of chronic disease management. Collectively, these insights underscore the imperative for comprehensive educational programs that empower caregivers, ultimately benefiting both caregivers and patients in navigating the complexities of chronic illness care [

12].

4.2. Psychological and Emotional Experiences of Caregivers for Patients with Chronic Illnesses

Our research highlights the significant psychological and emotional challenges faced by caregivers of patients with chronic illnesses, revealing that 82.2% experience anxiety, 27.3% suffer from depression, and 23.0% feel isolated. These findings align with Golics et al. (2013), who reported that 92% of family members also experience considerable emotional distress due to caregiving [

3]. Notably, while 70.9% of caregivers acquired medical skills to assist their loved ones, this practical knowledge did not alleviate their emotional burdens, indicating that caregiving extends beyond physical care to encompass complex emotional dimensions. Both studies emphasize the necessity for comprehensive support systems that address these emotional needs, advocating for an integrated approach that enhances caregiver well-being and improves the overall quality of life for families managing chronic illnesses [

3].

4.3. Physical and Health Impacts on Caregivers of Family Members with Chronic Illnesses

A comparative analysis of our findings reveals substantial physical health consequences experienced by caregivers of individuals with chronic illnesses, with 57.1% reporting sleep disturbances, 35.4% experiencing fatigue, and 33.1% neglecting their own health [

14]. These statistics are corroborated by recent global trends; for instance, a 2025 systematic review indicates that up to 76% of family caregivers now report poor sleep quality, often characterized by frequent nocturnal awakenings and shortened sleep duration [

15]. The study indicates that the lack of adequate support contributes to increased caregiver burden, resulting in heightened physical and emotional distress. This interplay between physical health challenges and emotional well-being underscores the multifaceted nature of the caregiver experience, where the physical ailments associated with caregiving further exacerbate emotional stress, ultimately diminishing caregivers’ capacity to provide effective care. Both our research and the findings of Jika et al. emphasize the urgent need for healthcare policies and practices that comprehensively address the diverse needs of family caregivers [

14].

The World Health Organization (2025) recently advocated for a “Framework on Integrated People-Centered Health Services,” which specifically calls for the formal recognition of caregivers as “co-clients” within the healthcare system [

16]. Implementing targeted support mechanisms—such as the “unaccompanied care” models explored in 2024–2025 or the data-driven CarerQol assessment tools, is essential to alleviate burden [

17]. This discussion advocates for integrated approaches that ensure caregivers receive the necessary physiological and psychological support to maintain their own health while fulfilling their roles, ultimately enhancing the quality of care provided to those with chronic illnesses.

Financial strain emerged as a central and frequently reported hardship. While a direct loss of family income was less common (19.6%), the costs of treatment constituted a burden for 40.5% of respondents, and 59.1% reported that their personal finances were directly affected. This financial pressure manifested in tangible lifestyle changes (33.2%) and was identified as the single hardest aspect of caregiving by 52.9% of participants. In a context where family-based care is the norm, the economic impact on households can be severe, potentially limiting access to optimal care and exacerbating stress within the family unit [

18,

19].

Socially, caregiving led to significant role transformations. Participants reported changes in household roles and responsibilities (38.3%) and increased emotional stress within the family (51.1%). Interestingly, the experience was not uniformly negative regarding family cohesion; a substantial minority (33.9%) reported strengthened family bonds and increased empathy. This duality reflects the complex social impact of chronic illness, capable of both straining and uniting families [

20]. Furthermore, while most caregivers recognized the need for specialized care (79.8%), a sense of social isolation was notable (35.2%), indicating a gap between the private burden of care and public or community engagement.

A notable strength of this study is its community-based sampling of a large and diverse cohort (n=565), which enhances the generalizability of findings within the Riyadh context. The use of a multidimensional questionnaire allowed for a holistic capture of the caregiver experience across key domains of well-being. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design precludes the establishment of causal relationships between caregiving and the reported burdens. The reliance on self-reported data is susceptible to recall and social desirability biases. Furthermore, the recruitment was confined to Riyadh, which may limit the applicability of results to other regions with different socioeconomic or cultural dynamics within Saudi Arabia. The study also focused on a broad range of chronic conditions; disease-specific burdens and coping mechanisms may vary and warrant further investigation.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study illuminates the significant and multidimensional burdens shouldered by family caregivers of individuals with chronic illnesses in Riyadh. The convergence of high emotional distress, physical health compromises, and pronounced financial strain highlights an urgent public health need. There is a critical imperative to move beyond relying solely on familial goodwill and to develop structured, culturally sensitive support systems. Targeted interventions should include accessible mental health services, financial aid programs, caregiver education, and respite care options. Enhancing the support ecosystem for caregivers is not merely an act of social justice but a strategic investment that can improve the quality of life for both caregivers and patients, ultimately leading to more sustainable and effective chronic disease management within the community. Future longitudinal and interventional research is needed to develop and evaluate the efficacy of such support programs in the Saudi context.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AB,LA, HQ; Data curation: LA,HQ,SZ,NQ,HA; Formal analysis:AB; Methodology:HQ,NQ,HA; Supervision: AB; Writing—original draft: HQ,LA,NQ,SZ,HA; Writing—review and editing:SZ,LA,HQ. All: authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of AlMaarefa University (IRB No. IRB24-096, on 16 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Noncommunicable diseases. World Health Organization, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- CDC. About Chronic Diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html.

- Golics, CJ; Basra, MKA; Finlay, AY; Salek, S. The impact of disease on family members: a critical aspect of medical care. J R Soc Med. 2013, 106, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streisand, R; Mackey, ER; Herge, W. Associations of parent coping, stress, and well-being in mothers of children with diabetes: examination of data from a national sample. Matern Child Health J. 2010, 14, 612–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljuaid, M; Ilyas, N; Altuwaijri, E; Albedawi, H; Alanazi, O; Shahid, D; et al. Quality of Life among Caregivers of Patients Diagnosed with Major Chronic Disease during COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. In Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland); 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziaka, E; Tsiakiri, A; Vlotinou, P; Christidi, F; Tsiptsios, D; Aggelousis, N; et al. A Holistic Approach to Expressing the Burden of Caregivers for Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review. In Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland); 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Namla, M; Mahboob, A; Radwan, E; Sinan, Z; Al-Namla, A; Verjee, MA; et al. A narrative review of challenges faced by informal caregivers of people with dementia in the Middle East and North Africa. Front Med. 2025, 12, 1610957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, P; Yang, M; Hu, H; Cheng, C; Chen, X; Shi, J; et al. The impact of caregiver burden on quality of life in family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: a moderated mediation analysis of the role of psychological distress and family resilience. BMC public health 2024, 24, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salifu, Y; Ekpor, E; Bayuo, J; Akyirem, S; Nkhoma, K. Patients’ and caregivers’ experiences of familial and social support in resource-poor settings: A systematically constructed review and meta-synthesis. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2025, 19, 26323524251349840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, MSE; Razak, DA; Muna, N; Permatasari, R; Praptawati, DJ. Investigating the Impact of Age and Cultural Diversity in Perceptions of Life Milestones: A Case Study on Online Global Cultural Exchange (OGCE) International Project. Int J Adv Res Educ Soc. 2024, 6, 675–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H; Lin, R; Yan, M; Lin, L; Sun, X; Wu, M; et al. Associations between preparedness, perceived stress, depression, and quality of life in family caregivers of patients with a temporary enterostomy. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2024, 70, 102557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujamammi, AH; Alluhaymid, YM; Alshibani, MG; Alotaibi, FY; Alzahrani, KM; Alotaibi, AB; et al. Awareness of cardiovascular disease associated risk factors among Saudis in Riyadh City. J Family Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 3100–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, S; Chu, F; Tan, M; Chi, N-C; Ward, T; Yuwen, W. Digital health interventions to support family caregivers: An updated systematic review. Digit Health 2023, 9, 20552076231171967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jika, BM; Khan, HT; Lawal, M. Exploring experiences of family caregivers for older adults with chronic illness: a scoping review. Geriatr Nurs. 2021, 42, 1525–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, JL; Cornman, JC; Freedman, VA. The Number Of Family Caregivers Helping Older US Adults Increased From 18 Million To 24 Million, 2011–22: Article examines growth in the number of family caregivets providing help to older adults in the US. Health Aff (Millwood) 2025, 44, 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Framework to implement a life course approach in practice. In Framework to implement a life course approach in practice; World Health Organization, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cejalvo, E; Martí-Vilar, M; Gisbert-Pérez, J; Badenes-Ribera, L. The CarerQol instrument: A systematic review, validity analysis, and generalization reliability study. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, N; Engelberg, RA; Hough, CL; Cox, CE; Curtis, JR. The patient and family member experience of financial stress related to critical illness. J Palliat Med. 2020, 23, 972–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, MSN; Chan, DNS; Cheng, Q; Miaskowski, C; So, WKWJ. Association between financial hardship and symptom burden in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 9541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, E; Niyomyart, A; Hickman, RL, Jr. Family caregivers’ experiences and changes in caregiving tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Nurs Res. 2021, 30, 1088–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).