1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to the CAM Model

Xenografting technology has revolutionized the translation of basic cell biology studies into higher organisms, with the evolution of patient-derived xenografting (PDX) complementing the large scale omic studies that have driven precision medicine approaches in cancer [

1]. Although rodents are most commonly used as tumour-bearing xenograft models, there are other models which offer advantages in cost, scalability and compliance with the 3R principles (replacement, reduction, refinement). The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) xenograft model was first used as a host for tumour cells in 1911 [

2]. Since then, it has become a widely used alternative model for the study of tumour formation [

3,

4], angiogenesis [

5,

6], invasion [

7], metastasis [

8], proliferation [

9] and therapeutic intervention [

10].

The CAM is an extra-embryonic structure that forms in avian eggs through the fusion of the chorion and the allantois membranes between embryonic development day (EDD) 3.75-EDD4 [

11]. The membrane is comprised of three distinct layers, the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm, each contributing to essential functions such as respiratory gas exchange, calcium resorption and metabolic waste removal, serving as a functional analogue to the mammalian placenta [

11,

12]. Its most remarkable feature is the rapid development of an extensive capillary network, rendering it a highly-vascularized tissue that supports the avian embryo housed within the egg [

13,

14]. This vascularity, combined with the relatively transient immunological naiveté of the embryo [

15], has positioned the CAM model as a powerful tool for studying tumour biology across a range of cancer subtypes.

Over the past several decades, the CAM protocol has gained significant traction in cancer research due in part to this early immunological naiveté that permits the growth of human tumour xenografts with relatively low risk of tumour rejection [

16]. A variety of biological materials, including conditioned medium [

17], immortalised cell lines [

3], primary blood samples [

18] or tissues [

14] and organoids [

19] have been successfully introduced into this model. When implanted onto the CAM surface, tumour cells readily form three-dimensional masses that recapitulate key features of solid tumour behaviour [

20]. The short embryonic developmental window (7–10 days) following tumour cell implantation enables rapid data collection, while the external accessibility of the CAM facilitates real-time imaging, repeated drug administration and histological sampling—all without the need for surgical intervention. These advantages make the CAM model particularly valuable as an intermediate system that bridges the gap between

in vitro experiments and more complex mammalian

in vivo models. Additionally, CAM experiments are performed at a fraction of the cost of traditional murine models, often 98% cheaper, depending on the type of mouse used [

21].

1.2. Studying the Hallmarks of Cancer in the CAM Model

One of the primary strengths of the CAM model lies in its ability to support multifaceted investigations into the hallmarks of cancer [

9]. Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature, is readily induced by tumour xenografts (or even tumour-derived soluble material) on the CAM, and can be quantified via gross visualisation or histological staining. Vessel density, branching patterns and convergence toward the tumour mass are frequently used as endpoints [

22]. Accordingly the model greatly supports the evaluation of anti-angiogenic agents, which can be administered topically or intravenously via the CAM vasculature, allowing for real-time assessment of drug efficacy [

14].

Tumour invasion into the CAM stroma is another key application of the model, with the ectodermal and mesodermal layers providing structural integrity that permits the evaluation of cellular motility and tissue infiltration. Immunohistochemistry using human-specific cytokeratin antibodies enables visualisation of invasive fronts, while serial sectioning permits quantification of invasion depth and area. Additionally, matrix metalloproteinase activity and degradation of the basement membrane can be assessed to elucidate mechanisms of invasion [

23].

The CAM model is also well-suited for studying metastatic dissemination, a process that cannot be recapitulated

in vitro. Tumour cells that enter the vasculature can be detected at secondary sites, including distal regions of the CAM and embryonic organs such as the liver, lungs, and brain. These metastatic events can be confirmed using molecular techniques such as PCR amplification of human-specific Alu sequences, or by imaging fluorescently-labelled cells

in situ [

6,

8,

24].

Proliferation, a fundamental aspect of tumour progression and therapeutic responsiveness, can be assessed in the CAM model using markers such as Ki-67, which identifies actively cycling cells [

25]. In addition, Western blotting and immunofluorescence can be employed to assess the activation of proliferation-related signalling pathways, such as MAPK/ERK, offering a molecular readout that complements morphological findings [

26].

Inflammation is rapidly triggered post-grafting, with heterophils (avian neutrophil equivalents) and monocytes/macrophages infiltrating within hours [

24]. These cells release cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), such as MMP-9 from heterophils and MMP-13 from macrophages, driving extracellular matrix remodelling. This inflammatory milieu promotes angiogenesis and compromises endothelial integrity. Tight junction proteins—including claudins and ZO family members—are particularly susceptible to MMP activity and cytokine signaling. The CAM model thus offers a dynamic system to study how inflammation-driven MMPs contribute to cancer-associated vascular remodelling via tight junction disruption and barrier dysfunction.

The chick CAM model presents a versatile, ethically advantageous, and cost-effective platform for the comprehensive study of tumours, both common and rare. Its ability to model angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis and proliferation in a dynamic, vascularised environment—combined with its utility in novel drug evaluation and barrier biology—makes it an indispensable tool in modern cancer research. This is particularly true when interrogating the emerging functional role of tight junction (TJ) adhesion complexes in tumour progression.

1.3. Adhesion, Tight Junctions (TJs) and the CAM Model

TJs are the apical-most component of epithelial and endothelial intercellular junctional complexes, establishing a selective, semi-permeable barrier that regulates the paracellular movement of ions, solutes and macromolecules. Increasingly, it is recognised that the physiological functions of TJs extend beyond their role in maintaining barrier integrity [

27,

28]. TJs are critical regulators of cell polarity, contribute to the maintenance of tissue architecture, and are involved in intracellular signaling pathways that influence cell proliferation [

29], differentiation, migration and play a role in stem cell maintenance [

30].

Importantly, the dysregulation of TJ components, including both transmembrane proteins such as claudins, occludin, and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), as well as cytoplasmic scaffolding partners like ZO-1, has been implicated in various aspects of cancer biology [

31]. Altered expression, mislocalisation, or functional disruption of TJ proteins can promote loss of cell polarity, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), increased invasiveness, neovascularization, evasion of cell death and metastatic dissemination [

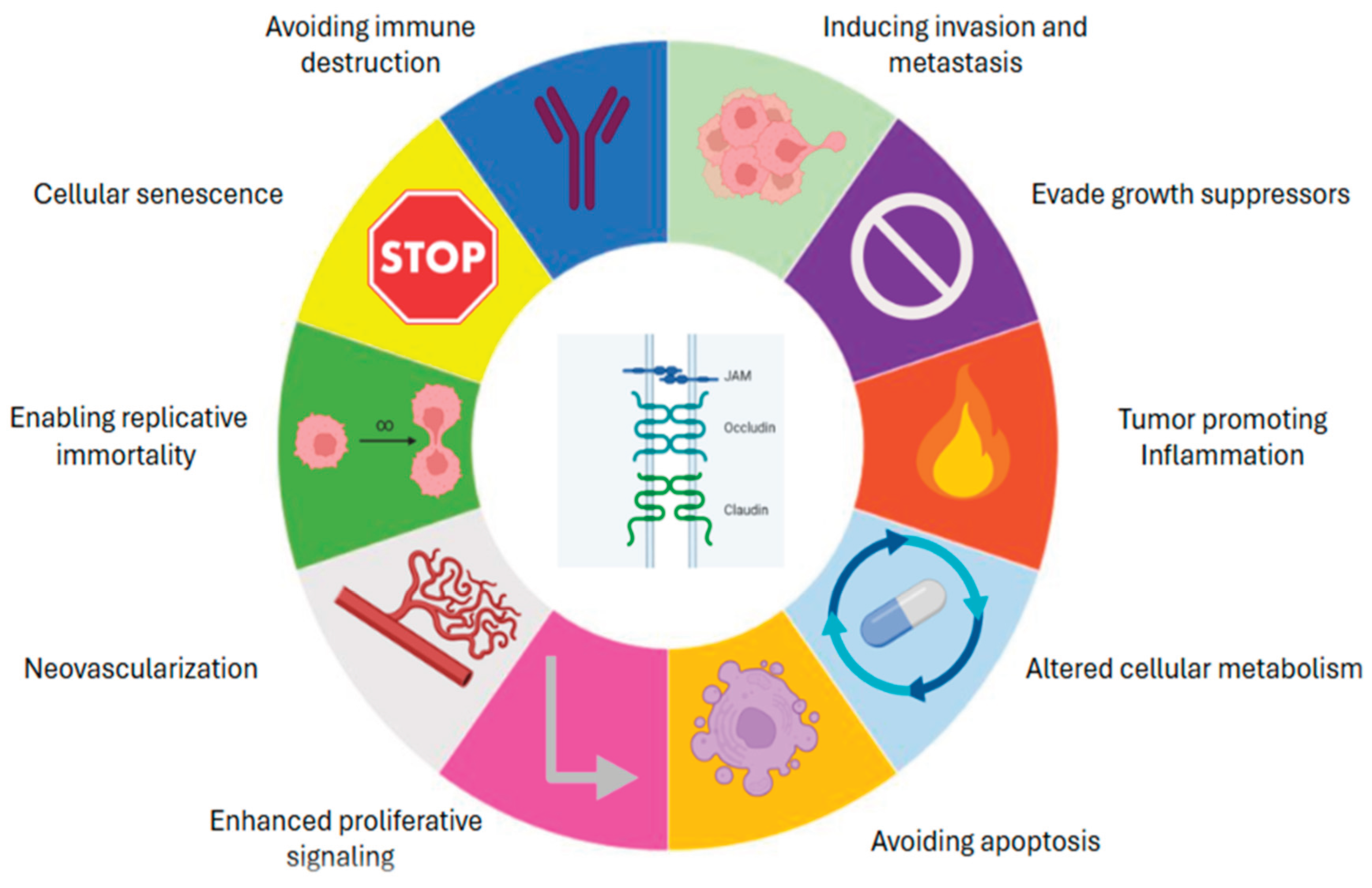

32]— recognisable events within the Hallmarks of Cancer (

Figure 1).

In the context of the CAM xenograft model, a well-established

in vivo platform for studying tumour progression and regression, angiogenesis [

33,

34], invasion and metastasis [

10,

35,

36]; the potential contribution of TJs to these events is of particular relevance. The highly-vascularised and physiologically- relevant environment of the CAM model enables observation of dynamic TJ remodelling in response to tumour cell grafting or pro-invasive stimuli. Understanding how TJ proteins contribute to, or are altered during, tumour–host interactions in the CAM model offers valuable insights into the roles of TJs in tumour progression and as targets of synthetic inhibitors or actors in the function of immunotherapy drugs.

This review will explore the multifaceted roles of TJ proteins in tumour pathophysiology, highlighting their contributions to oncogenic processes as elucidated through CAM-based studies, and discussing their potential utility as biomarkers or therapeutic targets in solid tumours.

2. Results

2.1. Integral Membrane TJ Proteins

Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): Junctional Adhesion Molecule (JAM) proteins are members of the Immunoglobulin superfamily of adhesion receptors. Among this superfamily, JAM-A is the most extensively studied in the context of cancer biology. Early work suggested that loss of JAM-A expression was associated with increased migratory potential in breast cancer cells [

37]. However, subsequent studies have increasingly indicated that JAM-A overexpression, rather than its loss, is more commonly associated with aggressive tumour phenotypes [

38,

39,

40,

41]. This reflects the complex nature of TJ proteins in either suppressing or promoting tumourigenesis depending on cellular context, and has opened up its investigation as a potential therapeutic target.

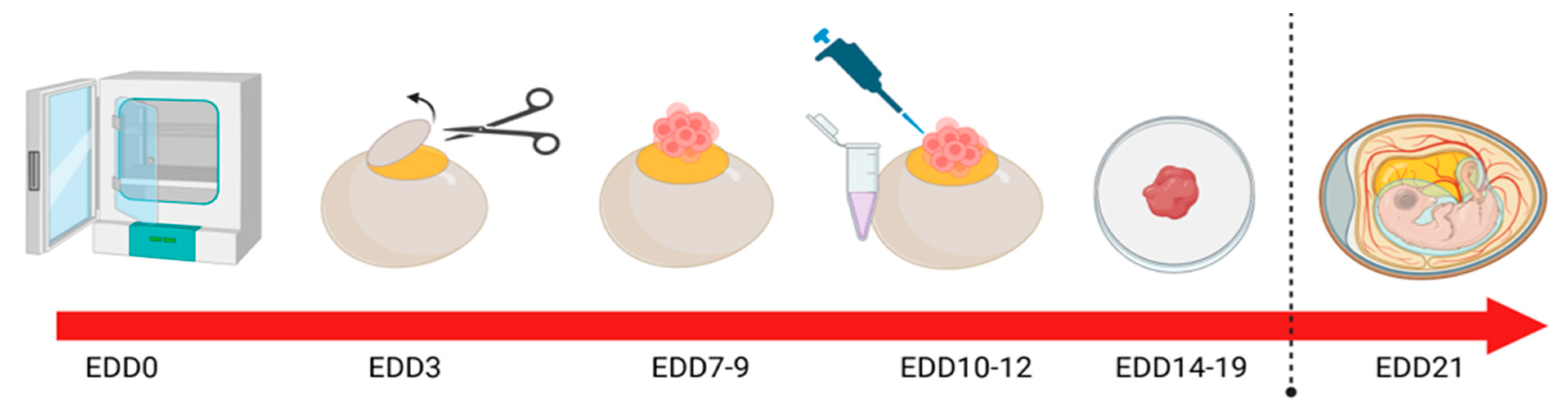

CAM modelling has been successfully used to interrogate the role of JAM-A in HER2-positive breast cancer

in vivo using the methodology outlined in (

Figure 2). Specifically, a recombinant fragment of the extracellular domain of JAM-A (rsJAM-A) was found to significantly increase the invasion of human SK-BR-3 cells implanted onto the CAM, as quantified by pan-cytokeratin staining deep into the intermediate mesodermal layer [

42]. Additionally, Ki67 positivity was also increased in rsJAM-A treated xenografts compared to controls. Moreover, the size of rs-JAM treated xenografts was grossly larger than the vehicle control-treated tumours [

42].

In related work, the natural antibiotic Tetrocarcin A was found to reduce JAM-A expression in human HER2-positive breast cells

in vitro, while sublethal doses reduced gross tumour size and proliferation index in HER2-positive model breast tumours grown on the CAM [

43]. The same compound also induced a pro-apoptotic response via the upregulation of cleaved caspase-3 expression in triple-negative breast tumours in the CAM model [

44]. While targeted protein reductions can also be achieved via gene silencing in tumour cells prior to/after implantation upon the CAM, it bears mentioning that transient silencing may be insufficient to influence global tumour phenotypes. Nonetheless, one study on JAM-A silencing in CAM-grown model breast tumours exhibited significantly altered staining of the proliferation marker Ki67 despite a very low siRNA transfection efficiency. Similarly, in a CAM model of gastro-oesophageal cancer using methodology outlined (

Figure 2), transient JAM-A silencing resulted in heterogeneous expression patterns that closely mirrored the intra-tumoral variability observed in patient-derived tumours [

45].

Moreover, a

cis-dimerization inhibitor of JAM-A termed JBS2 has been shown to reduce the number of macroscopically-visible HER2-positive model breast tumours on the CAM without causing overt embryonic toxicity, echoing parallel results from pre-clinical mouse models [

36]. Pairing JBS2 with the HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib evoked a more pronounced reduction in macroscopic tumour size

in ovo, but at the price of increased embryonic death [

36].

The role of JAM-A in angiogenesis is well established [

46,

47,

48], and its contribution to neovascularization in multiple myeloma has been recently studied in the CAM model. Specifically, Solimando and colleagues found an increase in angiogenesis when rJAM-A was added to MM endothelial cells

in ovo [

49], and, correspondingly, angiogenesis was impaired by an inhibitory JAM-A monoclonal antibody (J10.4). These findings were further validated in MM-bearing mouse models, suggesting that impairing

homo-dimerization of JAM-A restricts angiogenesis and represents a druggable target in MM [

50]. Notably, the increased overall survival of patients with MM has allowed for the emergence and detection of aggressive extramedullary disease (EMD), which may have previously gone unrecognised due to earlier mortality. EMD is often characterized by a distinct gene expression profile enriched for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and focal adhesion pathways, both features being closely tied to TJ dynamics and metastatic potential [

51]. Given the short developmental time-frame of the chick embryo (21 days gestation), the CAM xenograft model offers an excellent platform for investigating metastatic lesions or EMD in a timely manner.

To further underscore the significance of the JAM family in carcinogenesis, JAM-A has recently emerged as a potential immune-modulatory factor in human tumours [

52]. The chick embryo is uniquely equipped with a developing but functional immune system [

15,

53], and offers a novel platform to investigate immune cell infiltration and tumour responses to immunotherapy. This presents a distinct advantage over traditional rodent models [

15,

54,

55], which often require immunosuppression to permit tumour engraftment, thereby limiting their utility in assessing immune-related therapeutic responses. Building upon compelling

in silico and

in vitro evidence across multiple tumour types [

52], future studies may explore the potential of molecularly targeting JAM-A and co-treating with an immunotherapy for

in vivo validation within an immunocompetent model using similar methods to (

Figure 2). This approach holds promise for identifying novel therapeutic strategies and enhancing understanding of tumour-immune interactions in a physiologically-relevant setting. The immune system of pre- and post- treatment developing embryos can be evaluated in a number of ways as outlined in

Table 1.

Occludin and Claudins: Besides JAM-A, the role of other TJ proteins in cancer have also been studied in the CAM model. Occludin and claudins are integral membrane proteins that form the structural backbone of TJ architecture and are essential for maintaining barrier integrity. Beyond their architectural roles, they are also involved in regulating signalling in pathways that influence tumour progression [

56].

For example, Growth Differentiation Factor 11 (GDF11), a key regulator of cellular differentiation, has been shown to impair the invasive capacity of hepatocarcinoma cells

in vitro by modulating the expression of genes associated with TJ and EMT, including

occludin [

57]. Building on these findings, researchers employed the CAM model to investigate the effects of recombinant human GDF11 on tumour invasion. Liver xenograft tumours treated with GDF11 exhibited limited invasive behavior, with the majority of implanted tumour cells confined to the surface of the CAM [

57]. However, untreated xenografts displayed a notable presence of highly proliferative cells in the lower CAM layers, consistent with deeper tumour invasion in the absence of GDF11 treatment [

57].

Claudins too have been studied, in the context of angiogenesis in the CAM model. LPS-induced inflammation increased angiogenesis and upregulated tight junction genes including claudin-1, claudin-5, and claudin-12. Treatment with the antioxidant NAC reversed these effects, normalizing claudin expression and reducing vascular permeability, while also increasing VE-cadherin expression to potentially restore endothelial junction stability [

58].Tight junction permeability measurement outlined in

Table 1.

2.2. Other Adhesion Complexes and Signaling TJ Proteins

YAP and TAZ: The TJ-affiliated signalling proteins Yes-associated protein (YAP) and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), effectors of the Hippo signalling pathway, have emerged as critical regulators of tumour angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis. Their activity is closely modulated by mechanical cues and extracellular matrix stiffness—features that can be precisely manipulated and visualised in the CAM model ([

12,

59]. In this context, YAP/TAZ have been shown to influence tumour angiogenesis by regulating pro-angiogenic factors such as CTGF, CYR61, angiopoietin-2 and VEGF [

60,

61], while also modulating endothelial cell function and vascular remodelling [

62]. The clinical significance of YAP/TAZ dysregulation in human cancers is underscored by accumulating evidence linking aberrant TJ protein expression to poor prognosis, enhanced metastasis, and therapeutic resistance across multiple tumour types. Although the broader role of YAP/TAZ in cancer cell invasion and metastasis is well established, few studies have directly examined these mechanisms using the CAM model. Notably, Jiang et al. (2020) demonstrated enhanced invasion of triple-negative breast cancer cells via YAP signalling in a CAM xenograft model, highlighting its utility for mechanistic investigation [

63]. The suitability of this model for functional perturbation makes it valuable for testing YAP/TAZ-targeted strategies and understanding their mechanosensitive role in the tumour microenvironment. As such, the CAM model presents a physiologically relevant system for advancing our understanding of YAP/TAZ-driven cancer progression.

Cadherins: Cadherins, particularly E- and N-cadherin, are calcium-dependent adhesion molecules forming part of the adherens junctional complex. They play a crucial role in maintaining cell-cell adhesion and linking the cell membrane to the actin cytoskeleton. Their dysregulation is closely associated with EMT and metastatic dissemination.

In a non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) model using the CAM, the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha 5 (α5-nAChR) and lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E (Ly6E), were shown to influence tumour behaviour via the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway [

64]. While initial

in vitro experiments demonstrated their role in promoting cancer cell migration, their functional relevance was confirmed

in vivo on the CAM, where siRNA-mediated knockdown of α5-nAChR or Ly6E led to reduced expression of EMT markers such as ZEB1 and vimentin, as assessed by immunohistochemistry [

64]. Although E-cadherin expression was not directly measured in the CAM model, the downregulation of ZEB1—a known repressor of E-cadherin—raises the possibility that restoring E-cadherin could re-establish epithelial adhesion and counteract EMT in these tumours. Additional studies have also identified promising drug combinations (such as Phenethyl Isothiocyanate and Dasatinib) that limited E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression in hepatocellular carcinoma

in vitro and blunted angiogenesis

in vivo in a CAM model [

65]. Future investigations into the expressional changes of the cadherin proteins

in vivo could provide further mechanistic insight into their role in tumour progression and angiogenesis methods, as outlined in

Table 1.

Integrins: The integrins are a group of transmembrane receptors that mediate cell adhesion to the ECM and play pivotal roles in cell signalling and the hallmarks of cancer. Recent work has explored the therapeutic modulation of integrins in glioblastoma multiforme in the CAM model. For instance, co-treatment with natural compounds berbamine and arcyriaflavin A (ArcA) at concentrations that significantly reduced the levels of integrin α6 and key stem cell markers (Sox2, Nanog, Oct4)

in vitro was also shown to reduce tumour weight

in vivo, highlighting the potential of integrin targeting in glioblastoma [

66].Other integrin subunits, such as β

1, and β

3, have also been shown to cooperate with VEGFR receptors to induce angiogenesis. Integrins have been underexplored in the CAM model to date, but its vascularized and immunocompetent environment offers a promising platform to investigate tools such as a novel PEG-cRGD-conjugated drug BGC0222; already shown in a CAM setting to have antitumour activity via binding to

avβ3 and blunting neovascularization [

67].

3. Discussion

The chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model continues to emerge as a powerful, physiologically relevant

in vivo system for investigating tumour biology. This

in vivo model is highly convenient, accessible, reliable, and cost-effective alternative, aligning well with the 3R principles of minimizing animal experimentation – Replacement, Reduction and Refinement. Importantly, in many jurisdictions experimentation using the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) model does not require formal ethical approval, as the embryo is not considered sentient or innervated prior to hatching. However, regulatory requirements may vary internationally and should be confirmed on a case-by-case basis. Its unique advantages, including low cost, rapid tumour growth kinetics and immunotolerance early in development make it an attractive and ethically-favourable complement to mammalian models, and well-suited to studying the complex interplay between tumour cells and their microenvironment in an accelerate experimental timeline. Their alignment with the 3R principles also support more sustainable and human research practices. In the UK, a review of Home Office animal licences from 2017-2023 identified eight licence applications for angiogenesis research that collectively proposed to use 135,000 mice over 5 years [

75]. Given the highly-vascularized nature of the CAM and its established utility as a model for angiogenesis research and drug testing [

9], the case to use it as an intermediate model that reduces animal use is compelling.

Crucially, the CAM model’s accessibility, vascular richness and compatibility with live imaging afford a dynamic platform for studying not just angiogenesis but also tumour cell invasion and extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions in real time. This is further enhanced by its ability to support the growth of a wide range of tumour types, from established cell lines to, increasingly, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). The ease with which experimental manipulations and live imaging can be undertaken underscore its flexibility and translational potential, particularly when compared to traditional rodent models.

In the context of tight junction (TJ) proteins, such as JAM-A, occludin, and claudins, the CAM model is particularly well-positioned to dissect their multifaceted toles in tumour progression. These proteins do not merely function as structural barriers; they actively regulate signalling pathways implicated in proliferation, metastasis, and therapy resistance. The short gestation period of the chick embryo and its responsiveness to genetic or pharmacological manipulation allow for the rapid evaluation of TJ-mediated phenotypes in vivo. Moreover, the emerging connection between junctional integrity and mechanotransduction pathways, particularly through YAP/TAZ signalling, adds further value to the CAM model. As mechanical cues from the tumour microenvironment (TME) are increasingly recognised as central regulators of cancer behaviour, the CAM provides a biomechanically-responsive environment to interrogate these interactions at both the molecular and tissue level. Although studies investigating signalling proteins using the CAM model remain limited, this system should be considered a promising in vivo platform for future tumour biology research in this area.

Despite these strengths, the model has inherent limitations. The embryonic nature of the chick host means that aspects of the immune-tumour interaction cannot be fully recapitulated, and the absence of mature stromal components may influence tumour growth kinetics or drug response. Additionally, the short experimental window, typically 7-10 days post-engraftment, limits the assessment of long-term outcomes such as dormancy, late-stage metastasis, the development of clinical drug resistance or tumour recurrence post-resection. Reproducibility can also be challenged by inter-operator variability in grafting techniques that might alter overall tumour take rates or embryo viability.

Nonetheless, recent methodological innovations are addressing many of these limitations. Advances in live imaging, quantitative image analysis and molecular profiling (e.g. spatial transcriptomics or multiplex immunofluorescence) now enable high-resolution mapping of tumour-stroma interactions within the CAM either

in vivo or particularly in

ex ovo models [

76,

77]. The integration of CRISPR/Cas9 and RNAi technologies into CAM workflows further facilitates functional genomic screening, enabling dissection of gene-specific roles in tumour growth and invasion. Moreover, the growing use of PDXs within the CAM is accelerating the development of rapid

ex vivo platforms for precision oncology, allowing tumour-specific responses to be evaluated in a matter of days; bridging the gap between bench and bedside.

To further enhance the impact of CAM-based research, greater standardization of protocols, including tumour implantation techniques, vessel quantification methods and timing of interventions is essential. Establishing consensus guidelines and reporting standards would improve reproducibility and promote wider adoption across oncology research disciplines.

Table 2.

Strengths and Limitations of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Xenograft Model in Cancer Research.

Table 2.

Strengths and Limitations of the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Xenograft Model in Cancer Research.

| Strengths |

Limitations |

| Rapid tumour growth: Allows evaluation of tumour progression, angiogenesis, and invasion within 7–10 days. |

Short experimental window: Limited to ~7–10 days post-engraftment, restricting long-term studies. |

| High vascularity: Enables real-time assessment of neovascularization and vascular targeting therapies. |

Immature immune system: Lacks full adaptive immunity, limiting study of immunotherapy or tumour–immune interactions. |

| Cost-effective and low-maintenance: Inexpensive compared to murine models; requires minimal infrastructure. |

Species differences: Avian host may not fully recapitulate mammalian tumour–stroma or ECM interactions. |

| No need for immunosuppression: Natural immune deficiency in the embryo supports xenograft engraftment. |

Variable tumour take rates: Can suffer from inter-operator variability and inconsistent tumour establishment. |

| Ethically favourable: Not classified as an animal experiment in many jurisdictions (<ED14), aligning with the 3Rs. |

Limited stromal complexity: Absence of fully developed mammalian stromal compartments may affect tumour behaviour. |

| Supports diverse tumour types: Compatible with cell lines, organoids, and increasingly, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs). |

Lack of long-term metastatic model: While early invasion and dissemination can be studied, full metastatic colonisation is limited. |

| Accessible for imaging and manipulation: Translucent membrane allows for direct observation and microinjection. |

Limited availability of chick-specific reagents: Antibodies and molecular tools for host–tumour interaction studies are less developed. |

| Amenable to genetic and pharmacological modulation: Supports siRNA, CRISPR, and small molecule screening. |

Reproducibility challenges: Standardisation of protocols and quantification methods is still evolving. |

| Translational potential: Emerging role in personalised oncology through PDX and drug response studies. |

Not suitable for chronic or immune-mediated diseases: Inadequate for studying long-term tumour–host dynamics. |

4. Conclusions

As oncology research increasingly shifts toward pre-clinical models which are physiologically relevant but also ethically responsible and cost-effective, the CAM model is poised to play an increasingly prominent role. Its utility extends beyond traditional angiogenesis assays to encompass mechanistic exploration of tumour progression, with particular promise in studying cell junction dynamics, ECM interactions and mechanosensitive pathways such as YAP/TAZ. Standardisation of experimental protocols, coupled with advances in imaging and molecular analyses, will be key to enhancing the reproducibility and translational relevance of this model.

Importantly, the CAM does not aim to entirely replace murine xenograft models but to complement them. Its unique strengths—particularly in early-stage screening, angiogenesis studies and potential for mechanistic dissection of individual protein contributions in cancer —provide critical insights that can guide and refine more complex in vivo studies. In the context of TJ signalling and its intersection with related pathways, the CAM offers a tractable and insightful platform for unraveling how structural proteins orchestrate tumour progression. When used alongside traditional models, the CAM model enriches the preclinical research toolkit, helping to faster translate molecular insights into therapeutic innovation.

In conclusion, the CAM model represents a critical asset in the pre-clinical cancer research landscape. Its strategic use can enhance mechanistic discovery, reduce reliance on mammalian models and contribute to the acceleration of therapeutic development, particularly in fields focused on TME dynamics and cell junctional signalling.

Author Contributions

N.M. wrote the main manuscript text. I.C. and R.S. contributed to manuscript writing. N.M. and R.S. developed the figures, while N.M. and I.C. prepared the tables. C.M.D., A.L., A.M.H., S.T., and C.E.R. provided critical revisions and editorial input. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This manuscript is a literature review and does not involve research on human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. No datasets were generated or analysed for this review.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for recent relevant funding from the following sources: (Breakthrough Cancer Research/Health Research Board/Health Research Charities Ireland (grant HRCI-HRB-2022-020 to A.M.H. and Siobhan V. Glavey), Science Foundation Ireland (13/IA/1994 to AMH), Health Research Board of Ireland (HRA/POR/2014/545 to AMH). The figures throughout this manuscript have been created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAM |

Chorioallantoic Membrane |

| TJ |

Tight Junction |

| JAM-A |

Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A |

| PDX |

Patient-Derived Xenograft |

| ECM |

Extracellular Matrix |

| TME |

Tumour Microenvironment |

| YAP |

Yes-associated Protein |

| TAZ |

Transcriptional Co-Activator with PDZ-binding Motif |

| RNAi |

RNA Interference |

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

References

- Kim, S.-Y.; van de Wetering, M.; Clevers, H.; Sanders, K. The future of tumor organoids in precision therapy. Trends in Cancer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rous, P. A SARCOMA OF THE FOWL TRANSMISSIBLE BY AN AGENT SEPARABLE FROM THE TUMOR CELLS. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1911, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, P.; Schenker, A.; Sahr, H.; Lehner, B.; Fellenberg, J. Optimization of the chicken chorioallantoic membrane assay as reliable in vivo model for the analysis of osteosarcoma. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, S.; Sawosz, E.; Grodzik, M.; Kutwin, M.; Wierzbicki, M.; Włodyga, K.; Jasik, A.; Reichert, M.; Chwalibog, A. Comparison of tumour morphology and structure from U87 and U118 glioma cells cultured on chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane. Bulletin of the Veterinary Institute in Pulawy 2013, 57, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D.; Nico, B.; Vacca, A.; Roncali, L.; Burri, P.H.; Djonov, V. Chorioallantoic membrane capillary bed: a useful target for studying angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis in vivo. Anat Rec 2001, 264, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner1, Normann; Ribatti4, Domenico; Willenbacher2, Wolfgang; Jöhrer3, Karin; Kern1, Johann; Marinaccio4, Christian; Aracil6, Miguel; García-Fernández6, Luis F.; Guenther Gastl2, G.U.; Gunsilius, Eberhard. Marine compounds inhibit growth of multiple myeloma in vitroand in vivo. Oncotarget 2015, Vol. 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.A.; Muenzner, J.K.; Kunze, P.; Geppert, C.I.; Ruebner, M.; Huebner, H.; Fasching, P.A.; Beckmann, M.W.; Bauerle, T.; Hartmann, A.; et al. The Chorioallantoic Membrane Xenograft Assay as a Reliable Model for Investigating the Biology of Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries Zijlstra, R.M.; Panzarella, Giano; Aimes, Ronald T.; Hooper, John D.; Marchenko, Natalia D.; Quigley, J.P. A Quantitative Analysis of Rate-limiting Steps in the Metastatic Cascade Using Human-specific Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Cancer Res 2002, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D.; Fluegen, G.; Garcia, P.; Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy, N.; Gribaldo, L.; Huang, R.Y.; Rasche, V.; Ribatti, D.; Rousset, X.; Pinto, M.T.; et al. The CAM Model-Q&A with Experts. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.; Richards, C.E.; Fay, J.; Hudson, L.; Workman, J.; Lee, C.L.; Murphy, A.; O'Neill, B.; Toomey, S.; Hennessy, B.T. Synergistic Effects of the Combination of Alpelisib (PI3K Inhibitor) and Ribociclib (CDK4/6 Inhibitor) in Preclinical Colorectal Cancer Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, H.; Tanoue, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Chan, C.J.J.; Yamada, S.; Saitou, M.; Fukuda, T.; Sheng, G. Mesothelial fusion mediates chorioallantoic membrane formation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2022, 377, 20210263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak-Sliwinska, P.; Segura, T.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. The chicken chorioallantoic membrane model in biology, medicine and bioengineering. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribatti, D. The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay. Reprod Toxicol 2017, 70, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ongeval, C.V.; Ni, Y.; Li, Y. Utilisation of Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Model Platform for Imaging-Navigated Biomedical Research. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, P.; Wang, Y.; Viallet, J.; Macek Jilkova, Z. The Chicken Embryo Model: A Novel and Relevant Model for Immune-Based Studies. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 791081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). A multifaceted experimental model. Mech Dev 2016, 141, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, A.; Ribatti, D.; Presta, M.; Minischetti, M.; Iurlaro, M.; Ria, R.; Albini, A.; Bussolino, F.; Dammacco, F. Bone Marrow Neovascularization, Plasma Cell Angiogenic Potential, and Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Secretion Parallel Progression of Human Multiple Myeloma. Blood 1999, 93, 3064–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizon, M.; Schott, D.; Pachmann, U.; Schobert, R.; Pizon, M.; Wozniak, M.; Bobinski, R.; Pachmann, K. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) Assays as a Model of Patient-Derived Xenografts from Circulating Cancer Stem Cells (cCSCs) in Breast Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencurova, K.; Tran, L.; Friske, J.; Bevc, K.; Helbich, T.H.; Hacker, M.; Bergmann, M.; Zeitlinger, M.; Haug, A.; Mitterhauser, M.; et al. An in vivo tumour organoid model based on the chick embryonic chorioallantoic membrane mimics key characteristics of the patient tissue: a proof-of-concept study. EJNMMI Res 2024, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Cai, L. Establishment of a transplantation tumor model of human osteosarcoma in chick embryo. The Chinese-German Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009, 8, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ishihara, M.; Chin, A.I.; Wu, L. Establishment of xenografts of urological cancers on chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) to study metastasis. Precis Clin Med 2019, 2, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane Angiogenesis Model. In Methods in molecular biology; Clifton, N.J.), 2012; Volume 843, pp. 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Zijlstra, A.; Partridge, J.J.; Kupriyanova, T.A.; Madsen, M.A.; Papagiannakopoulos, T.; Quigley, J.P. Unexpected effect of matrix metalloproteinase down-regulation on vascular intravasation and metastasis of human fibrosarcoma cells selected in vivo for high rates of dissemination. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 10959–10969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deryugina, E.I.; Quigley, J.P. Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane model systems to study and visualize human tumor cell metastasis. Histochem Cell Biol 2008, 130, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowron, M.A.; Sathe, A.; Romano, A.; Hoffmann, M.J.; Schulz, W.A.; van Koeveringe, G.A.; Albers, P.; Nawroth, R.; Niegisch, G. Applying the chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane assay to study treatment approaches in urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2017, 35, 544 e511–544 e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekatkar, M.; Kheur, S.; Deshpande, S.; Sakhare, S.; Sanap, A.; Kheur, M.; Bhonde, R. Critical appraisal of the chorioallantoic membrane model for studying angiogenesis in preclinical research. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakogiannos, N.; Ferrari, L.; Giampietro, C.; Scalise, A.A.; Maderna, C.; Rava, M.; Taddei, A.; Lampugnani, M.G.; Pisati, F.; Malinverno, M.; et al. JAM-A Acts via C/EBP-alpha to Promote Claudin-5 Expression and Enhance Endothelial Barrier Function. Circ Res 2020, 127, 1056–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, I.; Santacroce, G.; Puga-Tejada, M.; Hayes, B.; Crotty, R.; O'Driscoll, E.; Majumder, S.; Kaczmarczyk, W.; Maeda, Y.; McCarthy, J.; et al. Epithelial neutrophil localization and tight junction Claudin-2 expression are innovative outcome predictors in inflammatory bowel disease. United European Gastroenterol J 2024, 12, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, A.O.; Cruz, R.G.; Hill, A.D.; Hopkins, A.M. Paradigms lost-an emerging role for over-expression of tight junction adhesion proteins in cancer pathogenesis. Ann Transl Med 2015, 3, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionísio, M.R.; Vieira, A.F.; Carvalho, R.; Conde, I.; Oliveira, M.; Gomes, M.; Pinto, M.T.; Pereira, P.; Pimentel, J.; Souza, C.; et al. BR-BCSC Signature: The Cancer Stem Cell Profile Enriched in Brain Metastases that Predicts a Worse Prognosis in Lymph Node-Positive Breast Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Van Itallie, C.M. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2009, 1, a002584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Hirche, C.; Fricke, F.; Dragu, A.; Will, P.A. Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane as an in vivo Model for the Study of Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. J Vasc Res 2025, 62, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribatti, D. The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane as an experimental model to study in vivo angiogenesis in glioblastoma multiforme. Brain Res Bull 2022, 182, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokman, N.A.; Elder, A.S.F.; Ricciardelli, C.; Oehler, M.K. Chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay as an in vivo model to study the effect of newly identified molecules on ovarian cancer invasion and metastasis. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 13, 9959–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Y.E.; Wang, G.; Flynn, C.L.; Madden, S.F.; MacEneaney, O.; Cruz, R.G.B.; Richards, C.E.; Jahns, H.; Brennan, M.; Cremona, M.; et al. Functional Antagonism of Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A (JAM-A), Overexpressed in Breast Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS), Reduces HER2-Positive Tumor Progression. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, M.U.; Naik, T.U.; Suckow, A.T.; Duncan, M.K.; Naik, U.P. Attenuation of junctional adhesion molecule-A is a contributing factor for breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res 2008, 68, 2194–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.; McSherry, E.A.; Hudson, L.; Kay, E.W.; Hill, A.D.K.; Young, L.S.; Hopkins, A.M. Junctional adhesion molecule-A is co-expressed with HER2 in breast tumors and acts as a novel regulator of HER2 protein degradation and signaling. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2799–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Takasawa, A.; Takasawa, K.; Akimoto, T.; Aoyama, T.; Magara, K.; Saito, Y.; Ota, M.; Kyuno, D.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. Aberrant expression of junctional adhesion molecule-A contributes to the malignancy of cervical adenocarcinoma by interaction with poliovirus receptor/CD155. Cancer Sci 2021, 112, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSherry, E.A.; Brennan, K.; Hudson, L.; Hill, A.D.K.; Hopkins, A.M. Breast cancer cell migration is regulated through junctional adhesion molecule-A-mediated activation of Rap1 GTPase. Breast Cancer Research 2011, 13, R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathia, Justin D.; Li, M.; Sinyuk, M.; Alvarado, Alvaro G.; Flavahan, William A.; Stoltz, K.; Rosager, Ann M.; Hale, J.; Hitomi, M.; Gallagher, J.; et al. High-Throughput Flow Cytometry Screening Reveals a Role for Junctional Adhesion Molecule A as a Cancer Stem Cell Maintenance Factor. Cell Reports 2014, 6, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, A.O.; Vellanki, S.H.; Rutherford, E.J.; Keogh, A.; Jahns, H.; Hudson, L.; O'Donovan, N.; Sabri, S.; Abdulkarim, B.; Sheehan, K.M.; et al. Cleavage of the extracellular domain of junctional adhesion molecule-A is associated with resistance to anti-HER2 therapies in breast cancer settings. Breast Cancer Res 2018, 20, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellanki, S.H.; Cruz, R.G.B.; Jahns, H.; Hudson, L.; Sette, G.; Eramo, A.; Hopkins, A.M. Natural compound Tetrocarcin-A downregulates Junctional Adhesion Molecule-A in conjunction with HER2 and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins and inhibits tumor cell growth. Cancer Letters 2019, 440-441, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VELLANKI, S.H.; CRUZ, R.G.B.; RICHARDS, C.E.; SMITH, Y.E.; HUDSON, L.; JAHNS, H.; HOPKINS, A.M. Antibiotic Tetrocarcin-A Down-regulates JAM-A, IAPs and Induces Apoptosis in Triple-negative Breast Cancer Models. Anticancer Research 2019, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, C.E.; Sheehan, K.M.; Kay, E.W.; Hedner, C.; Borg, D.; Fay, J.; O'Grady, A.; Hill, A.D.K.; Jirstrom, K.; Hopkins, A.M. Development of a Novel Weighted Ranking Method for Immunohistochemical Quantification of a Heterogeneously Expressed Protein in Gastro-Esophageal Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummer, D.; Ebnet, K. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): The JAM-Integrin Connection. Cells 2018, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnet, K. Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): Cell Adhesion Receptors With Pleiotropic Functions in Cell Physiology and Development. Physiol Rev 2017, 97, 1529–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Lu, J.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Lin, J.; Jiang, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, T.; Xiao, S.; Zheng, Y.; et al. JAM-A Overexpression in Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Accelerated the Angiogenesis of Diabetic Wound By Enhancing Both Paracrine Function and Survival of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2023, 19, 1554–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimando, A.G.; Da Via, M.C.; Leone, P.; Borrelli, P.; Croci, G.A.; Tabares, P.; Brandl, A.; Di Lernia, G.; Bianchi, F.P.; Tafuri, S.; et al. Halting the vicious cycle within the multiple myeloma ecosystem: blocking JAM-A on bone marrow endothelial cells restores angiogenic homeostasis and suppresses tumor progression. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1943–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimando, A.G.; Brandl, A.; Mattenheimer, K.; Graf, C.; Ritz, M.; Ruckdeschel, A.; Stühmer, T.; Mokhtari, Z.; Rudelius, M.; Dotterweich, J.; et al. JAM-A as a prognostic factor and new therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2018, 32, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimando, A.G.; Da Via', M.C.; Borrelli, P.; Leone, P.; Di Lernia, G.; Tabares Gaviria, P.; Brandl, A.; Pedone, G.L.; Rauert-Wunderlich, H.; Lapa, C.; et al. Central Function for JAM-a in Multiple Myeloma Patients with Extramedullary Disease. Blood 2018, 132, 4455–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhang, B.; Ren, H.; Gao, X.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Q.; Huang, H. Identification and Validation of JAM-A as a Novel Prognostic and Immune Factor in Human Tumors. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Berner, J.; Bekeschus, S. In ovo model in cancer research and tumor immunology. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1006064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipper, A.J.; Warren, E.A.K.; Liao, K.S.; Liu, H.-C.; Michikawa, C.; Porter, C.E.; Wells, G.A.; Villanueva, M.; Brasil da Costa, F.H.; Veeramachaneni, R.; et al. Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Platform for Assessing the In Vivo Efficacy of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy in Solid Tumors. ImmunoHorizons 2024, 8, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartle, S.; Sutton, K.; Vervelde, L.; Dalgaard, T.S. Delineation of chicken immune markers in the era of omics and multicolor flow cytometry. Front Vet Sci 2024, 11, 1385400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vellanki, s.h.; Richards, C.; Smith, Y.; Hopkins, A. The Contribution of Ig-Superfamily and MARVEL D Tight Junction Proteins to Cancer Pathobiology. Current Pathobiology Reports 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardo-Ramirez, M.; Lazzarini-Lechuga, R.; Hernandez-Rizo, S.; Jimenez-Salazar, J.E.; Simoni-Nieves, A.; Garcia-Ruiz, C.; Fernandez-Checa, J.C.; Marquardt, J.U.; Coulouarn, C.; Gutierrez-Ruiz, M.C.; et al. GDF11 exhibits tumor suppressive properties in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by restricting clonal expansion and invasion. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2019, 1865, 1540–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhong, S.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.Y.; Chu, C.; Zeng, S.; Yan, Y.; Cheng, X.; Bao, Y.; Hocher, B.; et al. N-Acetylcysteine Suppresses LPS-Induced Pathological Angiogenesis. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 49, 2483–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panciera, T.; Citron, A.; Di Biagio, D.; Battilana, G.; Gandin, A.; Giulitti, S.; Forcato, M.; Bicciato, S.; Panzetta, V.; Fusco, S.; et al. Reprogramming normal cells into tumour precursors requires ECM stiffness and oncogene-mediated changes of cell mechanical properties. Nat Mater 2020, 19, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glienke, J.; Schmitt, A.O.; Pilarsky, C.; Hinzmann, B.; Weiss, B.; Rosenthal, A.; Thierauch, K.H. Differential gene expression by endothelial cells in distinct angiogenic states. Eur J Biochem 2000, 267, 2820–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Freire Valls, A.; Schermann, G.; Shen, Y.; Moya, I.M.; Castro, L.; Urban, S.; Solecki, G.M.; Winkler, F.; Riedemann, L.; et al. YAP/TAZ Orchestrate VEGF Signaling during Developmental Angiogenesis. Dev Cell 2017, 42, 462–478 e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Morsut, L.; Aragona, M.; Enzo, E.; Giulitti, S.; Cordenonsi, M.; Zanconato, F.; Le Digabel, J.; Forcato, M.; Bicciato, S.; et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 2011, 474, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, P.; Xu, H.; Liang, D.; Fang, K.; Du, S.; Cheng, W.; Ye, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. SASH1 suppresses triple-negative breast cancer cell invasion through YAP-ARHGAP42-actin axis. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5015–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Pan, P.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, P.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Y.; Kang, G.; Zhang, L.; et al. α5-nAChR associated with Ly6E modulates cell migration via TGF-β1/Smad signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 2022, 43, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strusi, G.; Suelzu, C.M.; Weldon, S.; Giffin, J.; Munsterberg, A.E.; Bao, Y. Combination of Phenethyl Isothiocyanate and Dasatinib Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastatic Potential through FAK/STAT3/Cadherin Signalling and Reduction of VEGF Secretion. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.M.; Jung, H.J. Synergistic Anticancer Effect of a Combination of Berbamine and Arcyriaflavin A against Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Q.; Yuan, J.D.; Ding, H.F.; Song, Y.S.; Qian, G.; Wang, J.L.; Ji, M.; Zhang, Y. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of a novel PEG-cRGD-conjugated irinotecan derivative as potential antitumor agent. Eur J Med Chem 2018, 158, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C. Exploring New and Emerging Mechanisms to Target Difficult to Treat Cancers; Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Alizadeh, M.; Pratt, S.; Stamatikos, A.; Abdelaziz, K. Differential Expression of Key Immune Markers in the Intestinal Tract of Developing Chick Embryos. Vet Sci 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martowicz, A.; Kern, J.; Gunsilius, E.; Untergasser, G. Establishment of a Human Multiple Myeloma Xenograft Model in the Chicken to Study Tumor Growth, Invasion and Angiogenesis 2015, 1940-087X 99, e52665.

- Schulze, J.; Librizzi, D.; Bender, L.; Jedelska, J.; Yousefi, B.H.; Schaefer, J.; Preis, E.; Luster, M.; Mahnken, A.H.; Bakowsky, U. How to Xenograft Cancer Cells on the Chorioallantoic Membrane of a Fertilized Hen's Egg and Its Visualization by PET/CT and MRI. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2023, 6, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, A.; Taylor, A.; Murray, P.; Poptani, H.; See, V. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Characterization of a Chick Embryo Model of Cancer Cell Metastases. Mol Imaging 2018, 17, 1536012118809585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, S.; Mundim, A.V.; Silva, R.R.; Queiroz, J.S.; Rios, M.P.; Notário, F.O.; Medeiros Ronchi, A.A.; Beletti, M.E.; Franco, R.R.; Espindola, F.S.; et al. Physiological Changes in Chicken Embryos Inoculated with Drugs and Viruses Highlight the Need for More Standardization of this Animal Model. Animals 2022, 12, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.A.E.; Cordeiro, C.M.M.; Elebute, O.; Hincke, M.T. Proteomic Analysis of Chicken Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) during Embryonic Development Provides Functional Insight. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 7813921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, M.J.; Holmes, T.; Davey, M.G. A scientific case for revisiting the embryonic chicken model in biomedical research. Developmental Biology 2025, 522, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handl, V.; Waldherr, L.; Arbring Sjöström, T.; Abrahamsson, T.; Seitanidou, M.; Erschen, S.; Gorischek, A.; Bernacka-Wojcik, I.; Saarela, H.; Tomin, T.; et al. Continuous iontronic chemotherapy reduces brain tumor growth in embryonic avian in vivo models. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 369, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faihs, L.; Firouz, B.; Slezak, P.; Slezak, C.; Weissensteiner, M.; Ebner, T.; Ghaffari Tabrizi-Wizsy, N.; Schicho, K.; Dungel, P. A Novel Artificial Intelligence-Based Approach for Quantitative Assessment of Angiogenesis in the Ex Ovo CAM Model. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).