The objective of this study is to assess the efficacy of three distinct simulation methodologies in replicating the primary stylized facts of equity returns and market structure. Specifically, we compare a basic Merton Jump-Diffusion Model, a Simplified Benchmark Approach Process Model (BAPM) with explicit leverage, and Platen’s advanced Stochastic Benchmark Process (SBP) BAPM. This section presents the comparative results across six key properties: Fat-Tailedness (Kurtosis), the Leverage Effect, Negative Skewness, the Zipf Power Law for firm size, market-wide positive covariance structures, and the presence of long-memory in volatility. The comparison highlights not only the successful emergence of these properties but also contrasts the theoretical superiority of the SBP model, which generates volatility and leverage endogenously from its core structure, against models that require these effects to be explicitly imposed.

3.1. Asset Pricing and Return behaviour

The three pricing models were fine-tuned by running numerous different simulation runs with different parameter settings. The goal was to target the previously described market characteristics. The R code reported matches the parameters used to generate the results reported. The authors acknowledge the assistance of (Google) in the development and refinement of the R code used for this analysis. The Merton model produced equity financial return characteristics with the values shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6. Properties of the equity returns generated by the Merton Model.

| Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Coefficient of Variation |

| 0.001182 |

0.02296 |

0.497 |

172.5928 |

19.42 |

The measurements of the return, standard deviation and skewness appear to be reasonable, but the kurtosis is far too high.

Table 7 presents the results for the BAPM model and shows that the means, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis have very reasonable and realistic values. The coefficient of variation is very high with a value of 135.67, but this is because the daily mean is near zero, thus the ratio of volatility (Std Dev) to mean is high.

Table 7. Properties of the equity returns generated by the BAPM Model.

| Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Coefficient of Variation |

| 0.00068 |

0.09226 |

0.3813 |

2.2174 |

135.67 |

Table 8 presents the results for the SPM model and again shows that the means, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis have very reasonable and realistic values. The coefficient of variation is very high with a value of 197.97, but this is because the daily mean is near zero, thus the ratio of volatility (Std Dev) to mean is high.

Table 8. Properties of the equity returns generated by the SPM Model.

| Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Coefficient of Variation |

| 0.000978 |

0.193623 |

0.5807 |

0.8015 |

197.97 |

To facilitate a comparison with actual market parameters we down-loaded a year’s worth of adjusted daily closing prices for five major stocks in the Dow Jones Index, namely Apple, Microsoft, United Health Group, Visa and Johnson and Johnson, for one year terminating on 1st November 2025. Their return properties are shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Financial Return Characteristics of Apple, Microsoft, United Health Group, Visa and Johnson and Johnson.

| Company |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

Coefficient

of Variation

|

| AAPL |

0.0007946330 |

0.02044543 |

0.6238346 |

11.136530 |

25.72940 |

| MSFT |

0.0009565097 |

0.01515879 |

1.0108713 |

8.750040 |

15.84803 |

| UNH |

-0.0019775136 |

0.03210627 |

-2.8401703 |

20.100734 |

16.23568 |

| V |

0.0006245149 |

0.01409472 |

-0.5467345 |

7.754523 |

22.56907 |

| JNJ |

0.0007134920 |

0.01223558 |

-0.7691757 |

8.999480 |

17.14887 |

The period considered has been marked by a great deal of uncertainty about the implications of President Trump’s combined tariff and foreign policy. Nevertheless, the return behaviour for these five companies is similar to the results of the Merton Model simulation with the exception of the value of the kurtosis. The maximum kurtosis reported in Table 9 is that for United Health with a value of 20.1 whilst the simulation produced a value of 172, which is far too high.

Similarly, though the statistical properties of the BAPM model and SPM are very reasonable, the values of the coefficients of variation, are far too high, for the previously mentioned reasons.

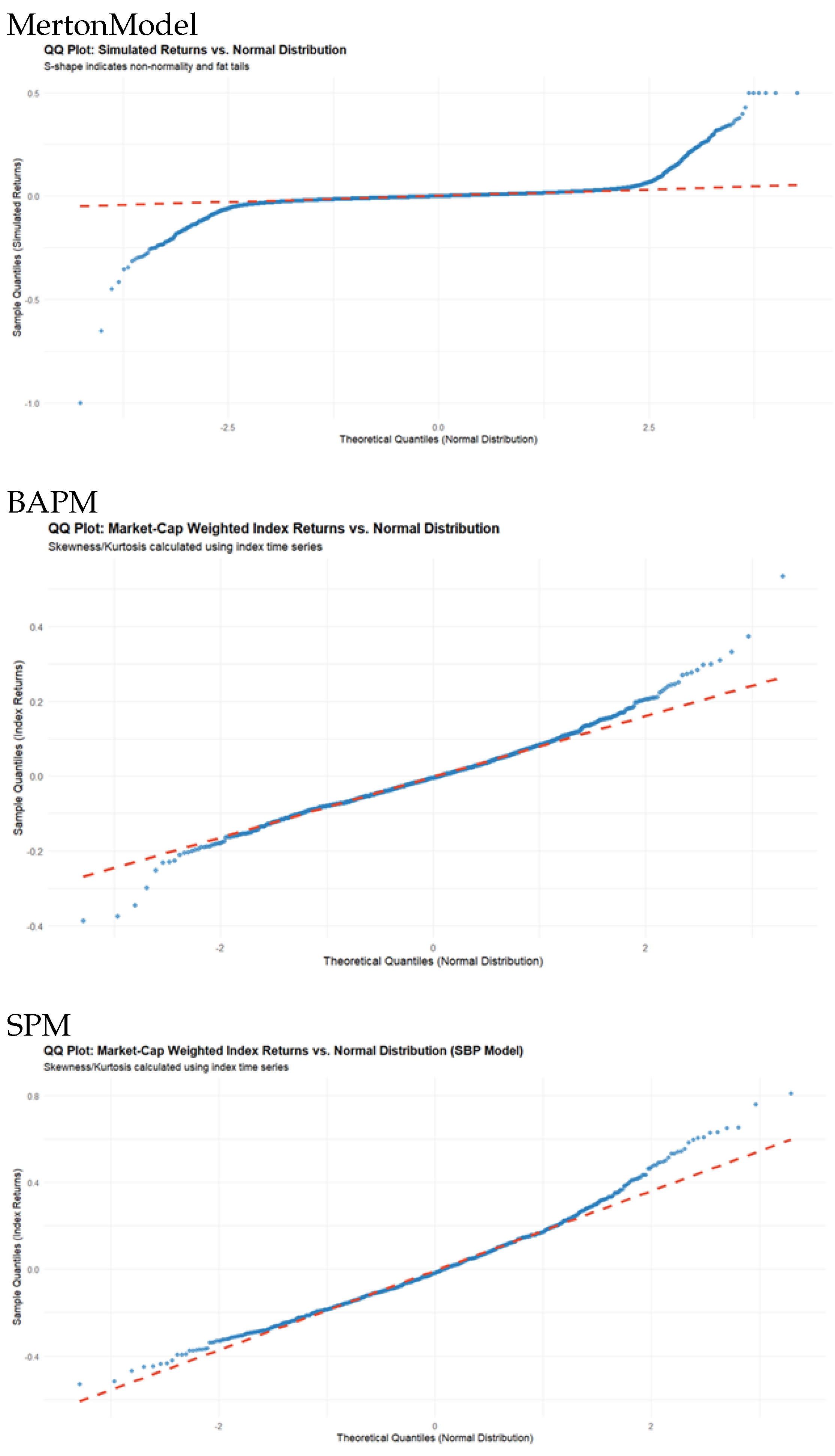

Figure 1 displays QQ plots of the return distributions generated by the three simulations and shows how far they deviate from Gaussian distributions.

The QQ plots of the results of the three simulation models shown in

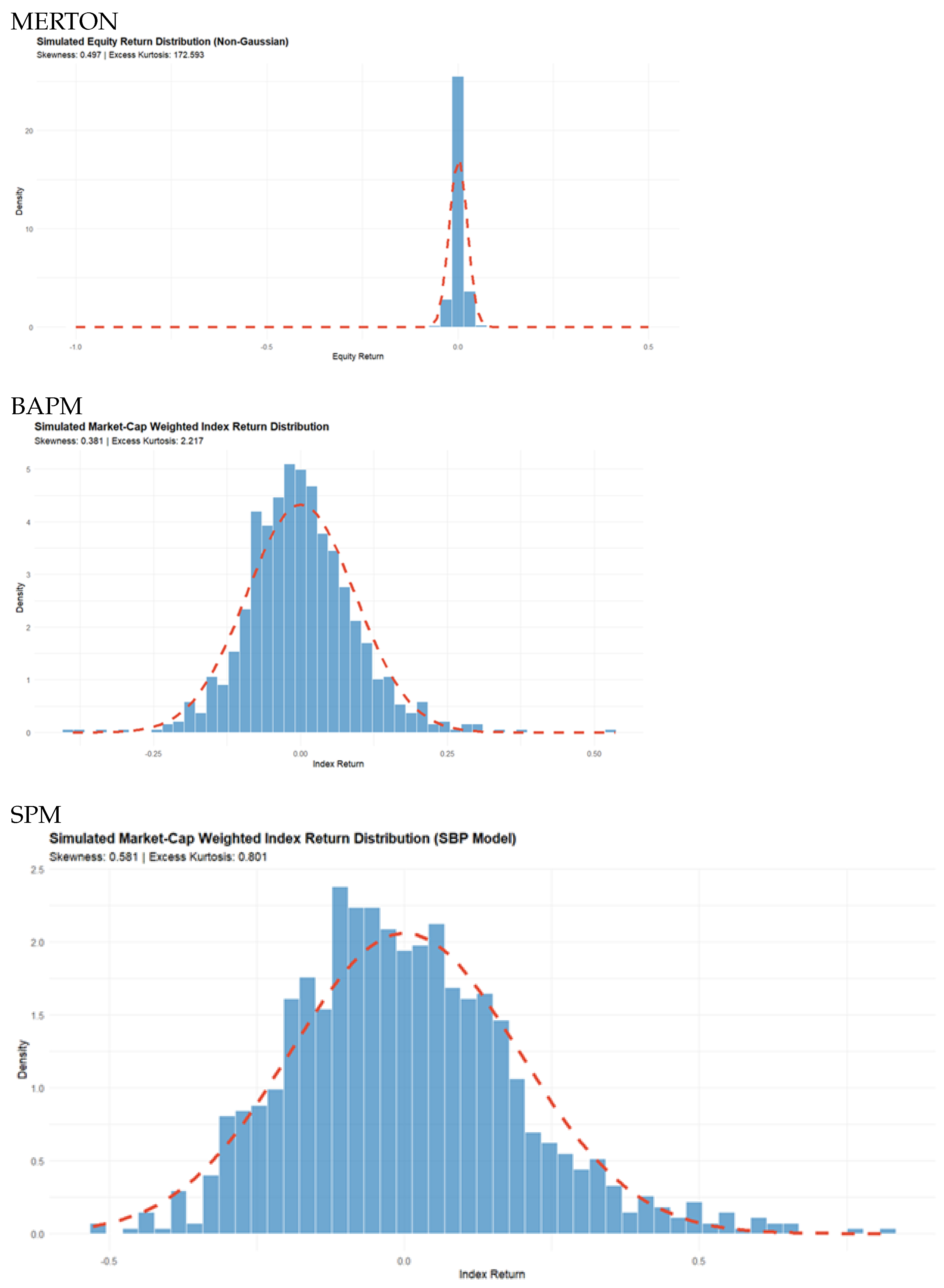

Figure 1 reveal that all the generated return distributions have fat tails, but the results of the Merton model deviates to a greater degree from a Gaussian distribution, as was previously suggested by the high kurtosis value. This is also confirmed by the plots of the three generated distributions which are shown in

Figure 2.

The distributions generated by the BAPM and SPM models possesses fat tails but are generally more realistic than the one produced by the Merton model. Why is this?

The problem lies in the fact that the Merton model is a structural model. This meant that to achieve realistic simulations results we had to prevent too many firms defaulting at the start of the simulation. This meant that at the start of the simulation we had to set the debt levels within narrow bands using the following R code.

# FIX 1: Debt levels (D): Adjusted to prevent tiny equity values for small firms

D = A_0 * runif(NUM_FIRMS, 0.65, 0.85) -

(1 - runif(NUM_FIRMS, 0.7, 0.95)) * 100,

Furthermore, we set a strict cap on equity returns, using the following code:

# --- Step 3: Calculate Returns (for t > 1) and BIND results (Includes Return Cap Fix) ---

if (t > 1) {

# Fetch previous period’s equity value for return calculation

prev_equity <- simulation_results %>%

filter(time == t - 1) %>%

pull(Equity_Value)

period_data <- period_data %>%

# CRITICAL: This line creates the ’Equity_Return’ column

mutate(Equity_Return = ifelse(prev_equity <= 1e-6, 0, (Equity_Value - prev_equity) / prev_equity)) %>%

# FIX 2b: Capping returns to prevent plot distortion from extreme events

mutate(Equity_Return = pmin(0.5, pmax(-1, Equity_Return)))

} else {

period_data <- period_data %>%

mutate(Equity_Return = NA_real_)

}

Even with the return cap set at a range between (0.5 and -1.0), the simulation generated distribution is still heavily concentrated around with the outliers clustered at the two boundaries, and this has the effect of producing high kurtosis.

A further important factor driving the fat tails in the simulations is the correlated jump process. To generate significant negative Skewness (the long left tail) and high Excess Kurtosis (fat tails), simply relying on the random movement of individual firms (even within the non-linear Merton framework) was not enough. It was necessary to explicitly introduce a Systemic Jump component—a small probability of a large, correlated negative shock across all firms. This suggestss that market crashes are primarily driven by systemic, shared risk factors, not just the aggregation of independent idiosyncratic risks.

3.2. Zipf-Mandelbrot Law and the Size Distribution of Firms

We wanted to ensure that the size distribution of firms in the simulations followed the Zipf-Mandelbrot law and conformed to what is observed in practice. The Zipf-Mandelbrot law is a static frequency distribution and when applied to corporate market values, it describes the cumulative distribution function (CDF) or the rank-size rule of these values at a single point in time. The law implies: Scale Invariance, or the existence of a Power Law Tail. The distribution indicates that the number of companies with market capitalization greater than M decays according to a power law (for large M). This is often interpreted as evidence of a highly competitive or scale-free market structure, where growth is largely independent of current size (Gibrat’s Law).

To verify this we downloaded the market capitalizations in US dollar terms of 3560 US companies (accessed 21 October 2025 from

https://companiesmarketcap.com/). We fitted the following model using Maximum Likelihood estimation in R :

. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8. Zipf-Mandelbrot Power Law fitted to 3560 US Companies

| Parameters |

estimate |

t value |

| C |

5.749e+13 |

19.49*** |

| alpha |

1.459 |

99.91*** |

| beta |

4.407 |

40.55*** |

| Pseudo R-Squared |

0.9768 |

NB:*** indicates signicance at the one percent level.

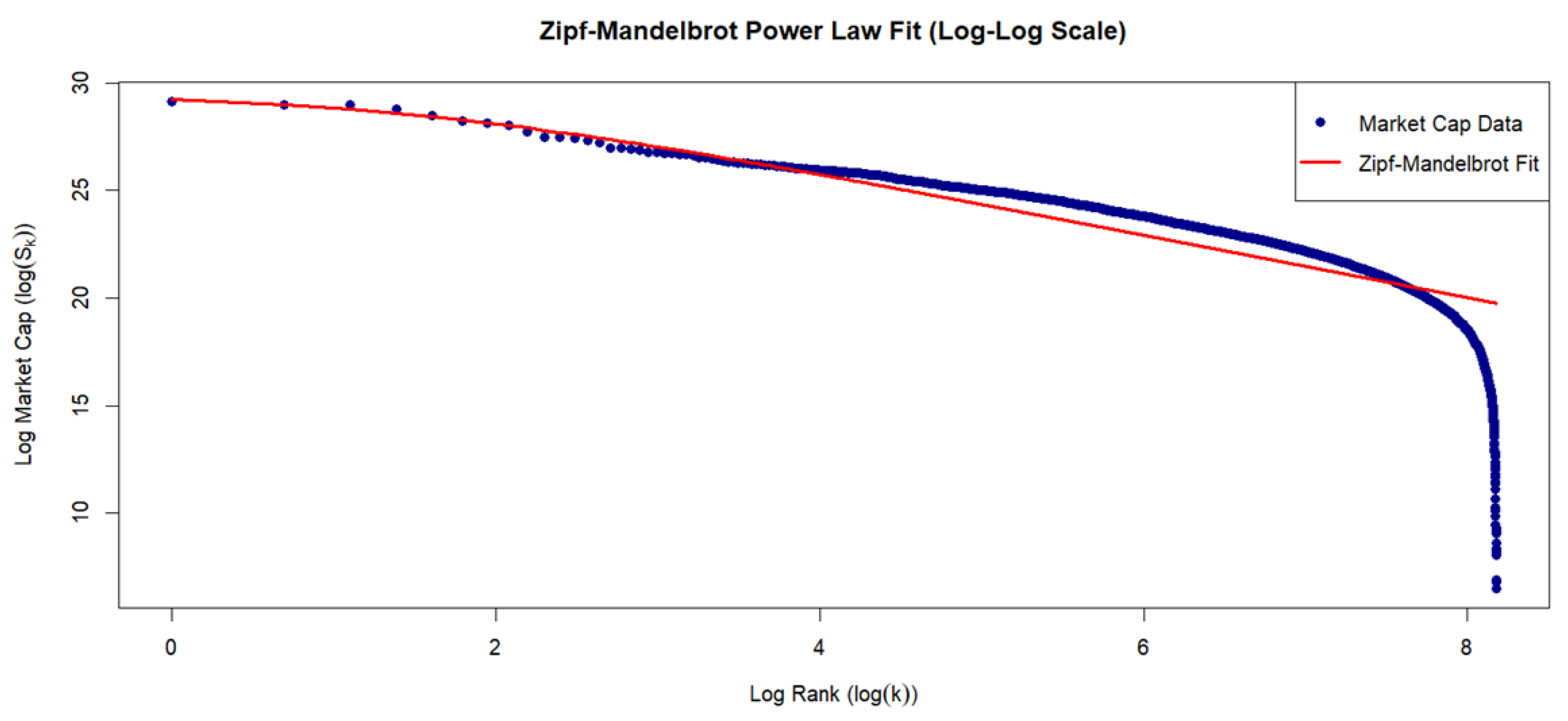

The estimates of this model recorded in Table 8 suggest that all coefficients are significant at the 1 percent level and the pseudo R-Squared statistic suggests that the model accounts for over 97 percent of the variance. The value of α is 1.459, and this is the estimated power-law exponent (or Zipf exponent).

Since α>1, this indicates that the distribution is heavy-tailed but has a finite mean and a finite variance. This value is typical for firm size distributions, which are often found to have exponents greater than 1. The value of beta is 4.407. This is the Mandelbrot shift parameter. A positive β value suggests the simple Zipf’s Law (β=0) would have over-predicted the size of the very largest firms (Rank 1, 2, 3), and the shift is necessary to better model the entire distribution, specifically the head. C is the scaling constant.

A plot of the fit of the model to the 3560 companies is shown in

Figure 3.

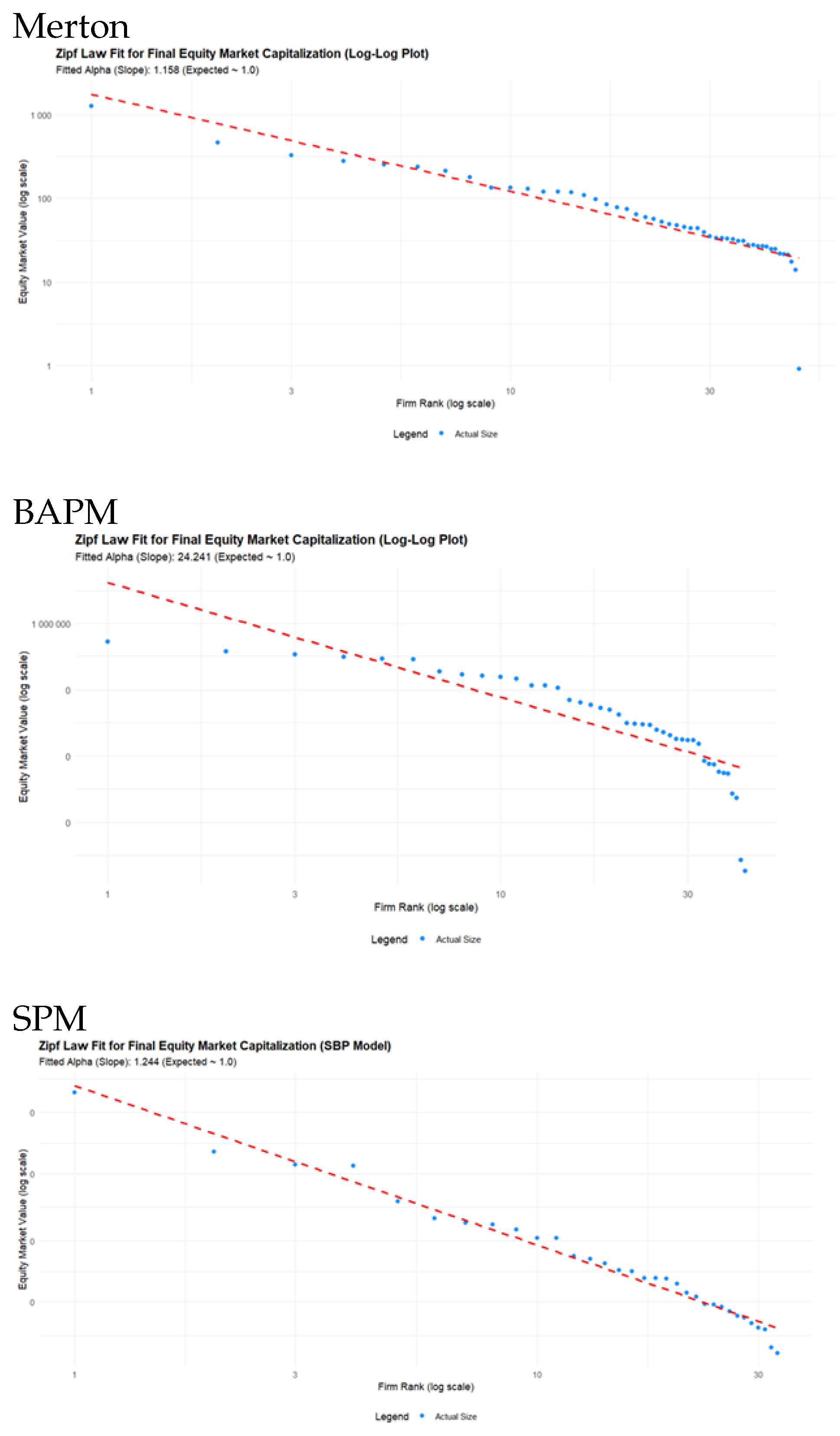

Table 9 shows the Zipf-Mandelbrot regression models fitted to the simulations generated by the two models. The fitted values are significant at the 1 percent level. Plots of the Zipf-Mandelbrot power law fits for the two simulation model outputs are shown in

Figure 4. The theoretical value of the slopes shown in

Figure 4 should be 1. The slope for the Merton Model is 1.158 whilst that for the SPM model is 1.244. Both are close to their theoretical values though the Merton Model is a slightly better fit.

The fit for the BAPM model is poor and the regression was eventually fitted to the absolute value of returns, however, the plot in

Figure 4 is to actual firm size.

Table 9. Zipf-Mandelbrot Power Law fitted to the simulated equity capitalizations generated by the two models.

| Merton Model |

BAPM |

SPM |

| Parameters |

estimate |

t value |

Parameters |

estimate |

t value |

Parameters |

estimate |

t value |

| C |

1.475943 |

27.227*** |

C |

4.699851 |

105.73*** |

C |

7.43078 |

13.98*** |

| alpha |

0.442571 |

60.428*** |

alpha |

0.229898 |

121.93*** |

alpha |

0.32826 |

28.82*** |

| beta |

3.57604 |

8.737*** |

beta |

0.010000 |

0.125 |

beta |

59.61363 |

10.42*** |

NB:*** indicates signicance at the one percent level

Figure 4. Zipf-Mandelbrot Power Law fitted to the simulated equity capitalizations generated by the three models.

The standard theoretical Zipf-law implies an alpha value that aprroximates 1 and a beta value that is zero. The regression values reported in Table 9 reflect that the alpha parameter in the Zipf-Mandelbrot Law, relates to the slope of the log-log plot which had slopes of 1.158 for Merton and 1.224 for SPM, and this controls the distribution’s tail behavior—specifically, how fast the market capitalization drops off as firm rank increases.

A lower alpha value of 0.44 and 0.33 respectively, implies a flatter slope on the log-log plot compared to the theoretical alpha value of 1. This means the simulated market is less concentrated than expected. The drop in market capitalization from the largest firm (Rank 1) to the smaller firms (Rank 2, 3, etc.) is slower than expected. In a highly concentrated market (high alphas), a few firms dominate, but in the simulation results for both models, the wealth is distributed more evenly among the largest firms.

The Simplified BAPM (Model 2) provided mixed results regarding the power-law stylized facts, demonstrating the critical need for the sophisticated Stochastic Benchmark Process (SBP) structure. While the model successfully captured the Fat-Tailed property of returns, yielding a highly significant power-law exponent of alpha of 0.2299 for absolute returns magnitude, it fundamentally failed to replicate the Zipf Law for firm size. The linear fit on the final equity capitalization (size) produced an exponent of alpha = 24.241 (

Figure 4), which diverges drastically from the empirical expectation of an alpha of approximately 1.0. This failure illustrates that simply enforcing the

structure and adding an explicit leverage term is insufficient to model the realistic growth dynamics that lead to power-law wealth concentration. This contrast highlights the theoretical necessity of the SBP (Model 3), which successfully generated a realistic size exponent of alpha 1.244 through its endogenous volatility and growth mechanisms.