1. Overview of the Complement System

The human immune system is an impressively complex network consisting of the coordinated interactions of numerous different cells, cytokines, proteins and intracellular signaling pathways. Two closely cooperating components are the innate (native) and acquired (adaptive) immune systems, which complement each other [

1].

Native immunity responds immediately to stimuli affecting the body, providing general defense. This network includes phagocytes: macrophages and neutrophil granulocytes; cytokines that promote inflammation; and the complement system [

1]. Eosinophil granulocytes are also part of innate immunity, playing a role mainly in defense against parasites and allergic reactions [

2].

The adaptive immune system is the body's specific defense mechanism with memory, which responds more slowly, over several days. Its main cells are B lymphocytes, which produce antibodies, and T lymphocytes, of which CD4+ helper T cells play a role in coordinating the immune response, while CD8+ cytotoxic T cells play a role in the direct destruction of infected cells [

2,

3].

The complement system is an ancient component of innate immunity, consisting of proteins circulating in the blood in an inactive (zymogen) form, i.e. complement factors. Originally, these components were thought to be exclusively of hepatic origin. However, it has recently been demonstrated that they are not only produced by the liver, but are also induced extrahepatically, providing local protection against pathogens on the surface of mucous membranes, the barriers. It has also been found that lung epithelial cells contain several intracellular complement components. In addition to lung epithelial cells, there are other sources of C3 in the lungs: macrophages, fibroblasts and mesenchymal stem cells [

4].

This complex protein network contributes to the removal of pathogens through several mechanisms: it stimulates phagocytosis, promotes pathogen opsonisation, emits chemotactic signals via the C3a and C5a components, and causes direct cell damage through the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC) [

2,

5].

The complement system can be activated via three different but interlinked pathways. Together, the classical, lectin and alternative pathways create a complex defense cascade in the body to destroy pathogens [

2]. The classical pathway is activated by the binding of the C1 complex to IgG or IgM antibodies or apoptotic cells, cleaving C4 and C2, which results in the formation of C3 convertase (C4b2a). Activation of the lectin pathway is initiated by the recognition of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) or ficolin, also resulting in the formation of C3 convertase. Activation of the alternative pathway begins with spontaneous cleavage of C3 on the pathogen surface, followed by the formation of the C3b-B factor complex through the proteolytic activity of factor D, resulting in the formation of functional C3 convertase (C3bBb). All three pathways converge at the cleavage of C3 into C3a and C3b. C3a is an inflammatory mediator, while C3b acts as an opsonin, promoting phagocytosis and the formation of MAC, which directly damages pathogens. During the activation of the C5 component, C5a acts as a potent inflammatory mediator, while C5b initiates the formation of MAC, which causes lysis through pore formation [

5,

6].

CR1, CD55 (DAF), MCP and CD59, which are expressed on the surface of body cells, and certain plasma proteins, such as C4b binding protein and H factor, inhibit complement activation and MAC formation, thereby protecting healthy tissues from the damaging effects of the immune system [

5,

7].

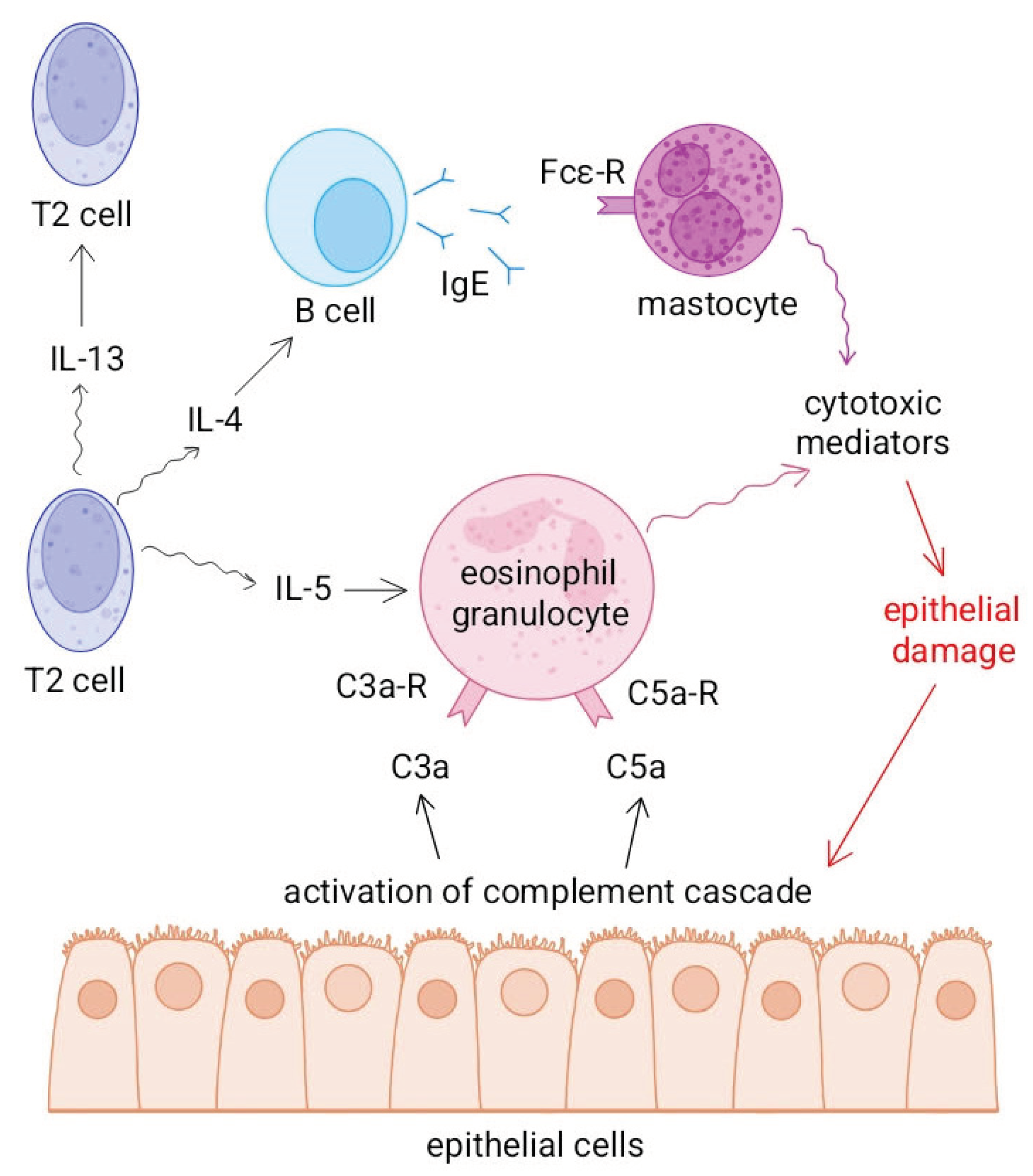

Recent research has shown that the complement system not only functions as part of innate immunity, but also actively influences adaptive immunity, including type 2 immune responses [

2,

8,

9]. C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins directly stimulate immune cells, which produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, leading to Th2 polarisation. This process is key to the development of allergic airway inflammation and the recruitment of eosinophil cells. Through C3aR and C5aR receptors expressed on the surface of eosinophils, they respond directly to complement activation products, which induce degranulation, release of cytotoxic proteins and persistent tissue inflammation. This interaction provides further evidence that the complement system acts as a bridge between the innate and adaptive components of the immune response, contributing to the development of chronic allergic inflammation, such as asthma or chronic rhinitis. Based on the currently popular concept of "barrier disease," epithelial-derived alarmins (IL-25, IL-33, TSLP) released during airway epithelial injury further enhance the complement-activated type 2 immune response. This means that the complement–T2–eosinophil axis may represent a key pathophysiological pathway in respiratory diseases that has been little studied and less explored to date, but which, based on recent data, may be of key importance [

2].

The activation of the complement cascade during respiratory infections is a key process that was originally considered an effective, reinforcing mechanism of immune defense against pathogens [

8]. Numerous research findings confirm that this complex system plays a key role not only in defense against infections, but also in number of non-infectious diseases, including various pathological conditions of the lungs, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sarcoidosis and lung cancer. Accordingly, an imbalance in the complement system, whether due to excessive activation or insufficient function, can contribute to the development and persistence of both acute and chronic respiratory diseases [

5].

2. The Role of the Complement System in Infectious Respiratory Diseases

The activation of the complement system is essentially one of the main complementary mechanisms of defense against pathogens [

5]. This is evidenced by the fact that certain viruses have developed different mechanisms to prevent or exploit the functioning of the complement system to their advantage. Poxviruses, for example, produce a protein that is similar in structure and function to complement-regulating proteins, thereby silencing the cascade. A similar trend can be observed in flaviviruses, which avoid activation of the system by diverting the host's complement-regulating proteins [

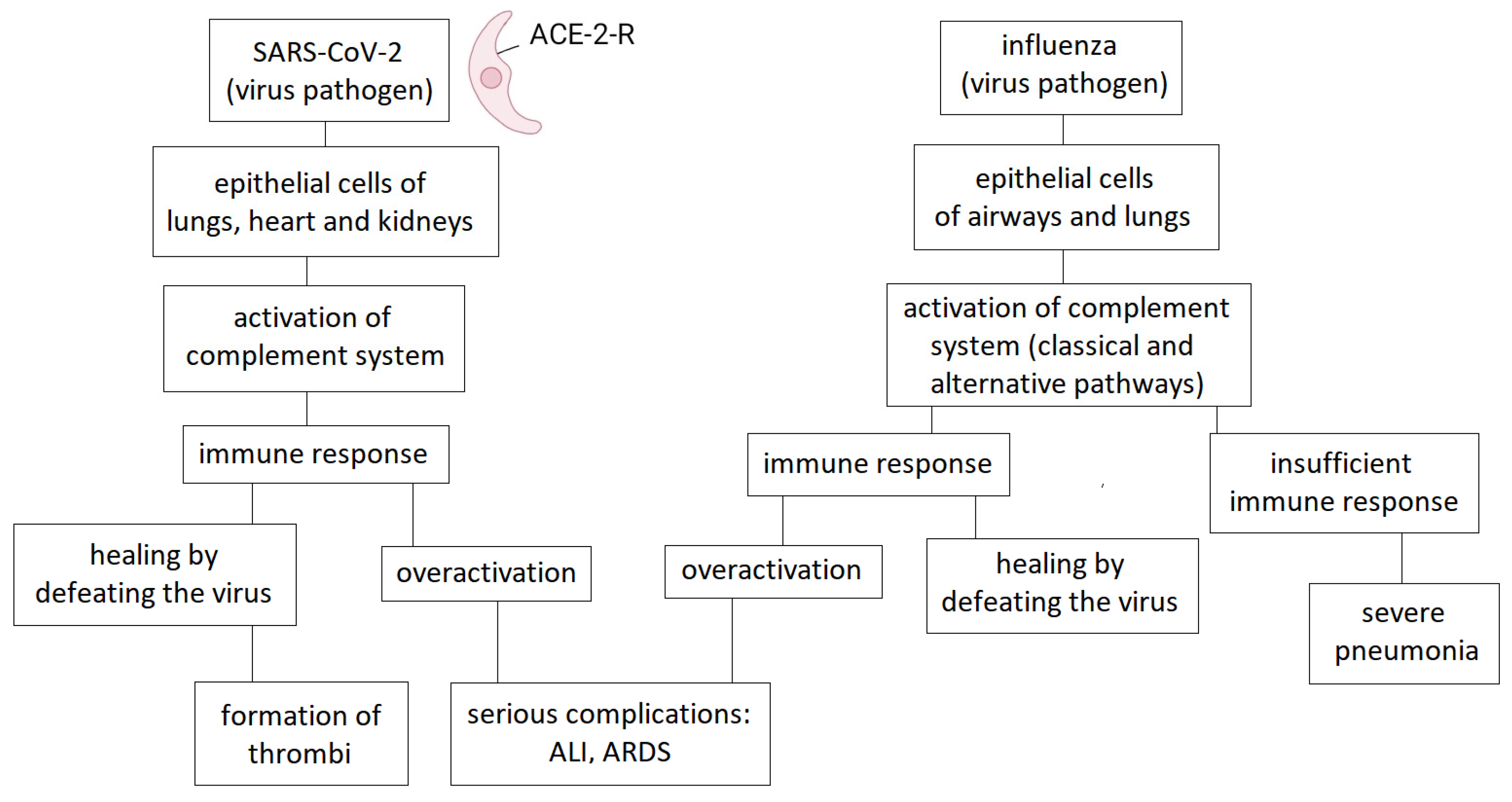

8]. Previous research on the role of complement in influenza laid the foundation for later complement-focused studies related to COVID-19 infection (

Figure 1).

2.1. Influenza

Influenza is one of the most common acute respiratory infections, recurring seasonally and placing a significant burden on public health due to its high mortality rate.

One of the main task of our immune system is to provide protection against pathogens, so in the case of influenza infection, its primary role is to eliminate the virus. However, excessive activation of the system no longer helps with protection, but on the contrary, becomes harmful to the body. A significant proportion of patients with severe influenza-induced pneumonia require intensive care due to immune-mediated acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [

10]. Based on research conducted in previous years, the complement system also plays a role in the development of these acute conditions through its overactivation [

11].

The complement system is activated in all three pathways during influenza infection. The opsonisation of viruses by complement components, the promotion of virolysis by MAC, the enhancement of phagocytosis, and the modulation of the immune response through the production of chemotactic factors and anaphylatoxins support the elimination of the virus [

11].

Excessive activation of the immune response, and thus ALI and ARDS, can be linked to increased complement system activity, particularly during H5N1 influenza infections. In one study, the products of complement activation and the expression of anaphylatoxin receptors were examined in the lungs of mice infected with the H5N1 virus. Their results showed that C3 deposition was increased and that complement activation occurred primarily via the lectin pathway. The use of a C3aR antagonist not only moderated the inflammatory response, reducing neutrophil infiltration and TNF-α levels, but also suppressed viral load. These results suggest that complement inhibition combined with antiviral therapy may be an effective strategy for treating ALI caused by H5N1 infection [

11].

The complement protein C3, CD35/CD21 receptors (CR1/CR2) and IgM not only play a role in the immune response to influenza virus but also have a key role in the secondary immune response to influenza virus, i.e. the development of long-term memory against the pathogen [

12]. Another study showed that human C1q, which is the recognition subunit of the classical pathway, significantly reduces the entry and further replication of the H1N1 subtype of the influenza virus into cells, while promoting the entry of the H3N2 subtype. C1q achieves this subtype-specific regulation without the involvement of other components of the complement system or antibodies. The main mechanism behind the complement-independent inhibition of H1N1 entry is likely to be the spatial barrier (steric inhibition) resulting from the large size of C1q. C1q interacts with haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins and is deposited on the surface of the influenza virus, thus masking the virus's receptor-binding sites and preventing it from attaching to cells. This may represent a potential new therapeutic target in the early stages of infection, particularly in the defense against H1N1 [

11,

13].

2.2. COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged at the end of 2019 and rapidly spread globally, posing unprecedented challenges to health systems and placing a significant burden on the daily functioning of societies [

14]. Severe forms of COVID-19 had variable pathogenesis, but there is growing evidence that immune system overactivation played a significant role in high mortality [

15].

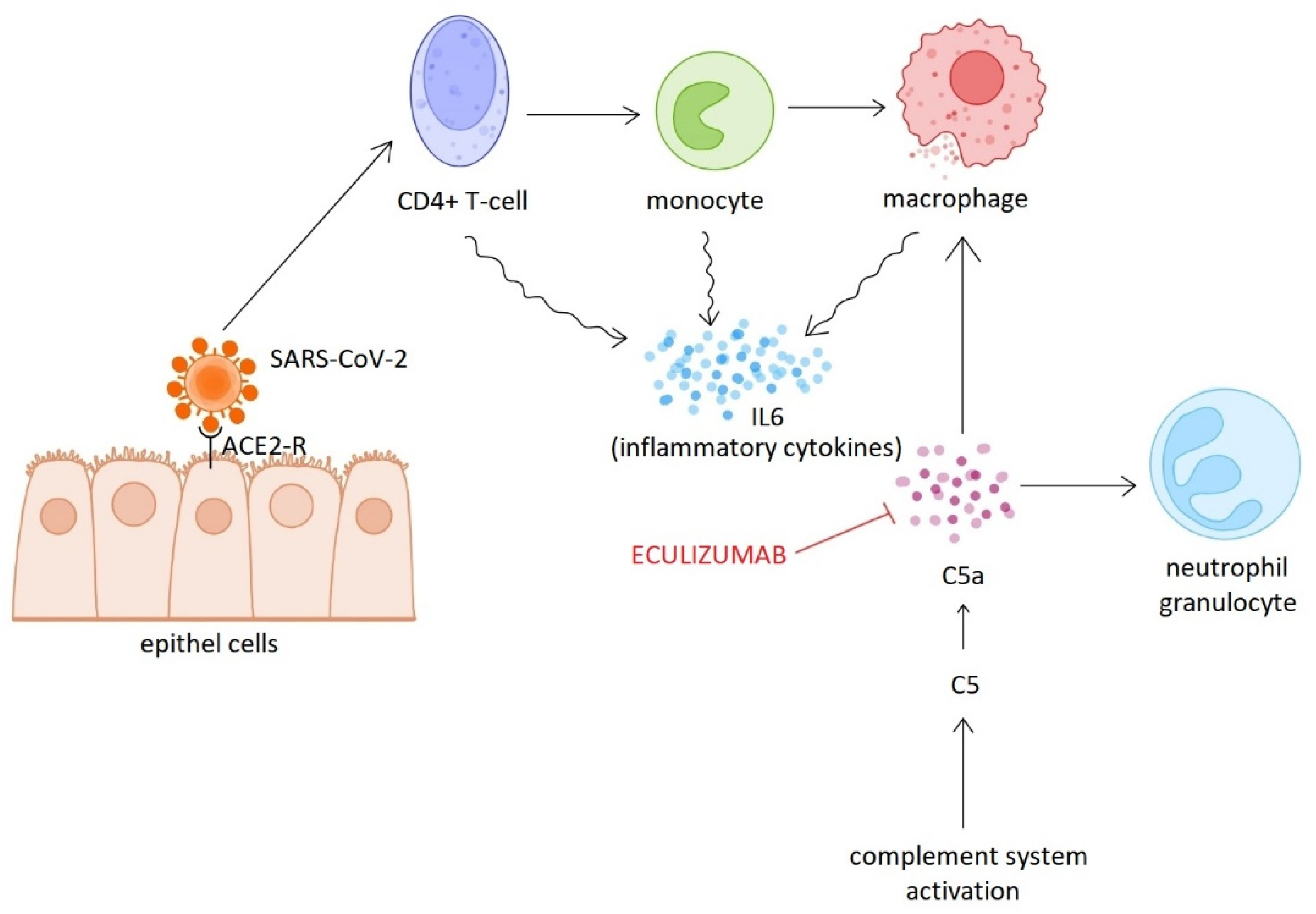

Following the rapid spread of the pandemic, numerous studies focused on elucidating the pathogenesis of the infection. The results of these studies have made it clear that complement system activation, dysregulation of neutrophil granulocyte responses, endothelial damage and hypercoagulability contribute to the severe clinical manifestations of COVID-19 [

14]. Inflammatory mediators released during complement activation (C3a, C5a) play a key role in neutrophil activation and inflammation maintenance, while MAC causes endothelial and tissue damage, which directly contributes to thrombosis formation [

14]. Proteomic analysis of plasma samples collected early in the pandemic showed that circulating sC5b-9 levels are significantly higher in COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalisation than in patients with influenza of similar severity or respiratory failure not associated with COVID-19. Furthermore, activation of the alternative pathway was observed to be particularly common in severe COVID-19 cases. Activation of this pathway was closely correlated with biomarkers of endothelial damage (angiopoietin-2) and hypercoagulability (thrombomodulin and von Willebrand factor). These results suggest that overactivation of the complement system may be one of the strongest indicators of COVID-19 infection [

16]. Beside the cytokine storm and ARDS playing a role in the development of respiratory failure and associated high mortality, endothelial dysfunction, platelet activation, and thrombosis of pulmonary capillaries are also contribute to the devastating outcome. The central importance of complement system activation has been confirmed in thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) associated with COVID-19, and complement-inhibiting therapeutic approaches have also been used, based on experience gained in the treatment of atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS) [

17]. The concentrations of soluble factors in blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were examined in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients of varying severity. The results showed a gradual increase in C5a levels as the disease progressed, and a significant increase in C5aR1 (CD88) receptor expression in peripheral blood. Histological studies also showed that the receptor was highly expressed in myeloid cells in the lungs, particularly in the vicinity of arteries and in thrombi. These observations suggest that the C5a–C5aR1 signaling pathway plays a key role in the development of ARDS [

18].

Diurno et al. presented four severe COVID-19 cases in which supportive therapy was supplemented with eculizumab (Soliris

®) treatment. Although the patients initially showed rapidly deteriorating respiratory function and bilateral milky infiltrates on chest CT scans, they all showed dramatic improvement within 48 hours of receiving the first dose of eculizumab. Particularly noteworthy is the case of an elderly woman with multiple comorbidities who, despite severe lung damage, made a full recovery without mechanical ventilation [

19]. Eculizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody that inhibits the C5 component. Inhibition of C5 blocks only the final, endothelium-damaging stage of the complement system. The early complement components, which play a key role in modulating the immune response and recognising pathogens, remain functional. This allows for gentler yet effective immunomodulation [

19]. Two European clinical trials are currently underway to investigate the use of eculizumab in COVID-19, and several studies are also underway to evaluate the efficacy of ravulizumab (Ultomiris

®). ravulizumab is also a recombinant C5 inhibitor antibody with a longer half-life than eculizumab [

14] (

Figure 2).

3. The Role of the Complement System in Non-Infectious Respiratory Diseases

3.1. Asthma

The incidence of allergic diseases is steadily increasing worldwide making asthma an increasingly significant public health challenge [

2]. Asthma is a chronic, non-infectious, heterogeneous respiratory disease with a highly complex pathogenesis and clinical presentation. It is characterised by different endotypes based on different immunological and cellular mechanisms. Different forms can be observed, which differ in their clinical course, severity and response to treatment [

20]. Although no actual pathogens can usually be detected in the lung tissue of asthmatic individuals, pathological immunological processes are activated, leading to chronic inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. In the long term, these mechanisms result in the remodeling of the airways and lungs [

20].

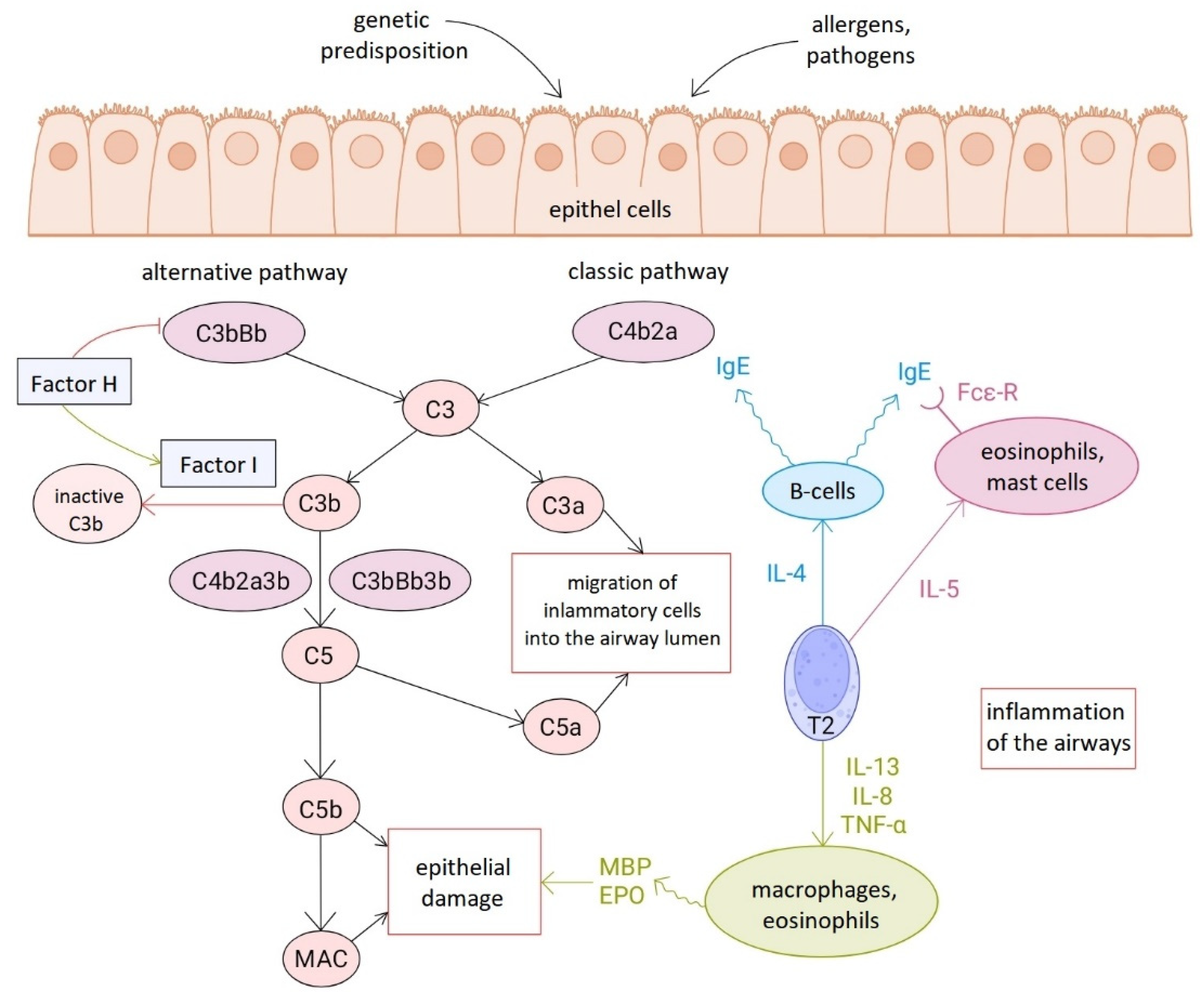

Although the adaptive immune system dominates in asthma through type 2 immune responses, and most research in this field focuses on acquired immunity, it is becoming increasingly clear that innate immune mechanisms also play a significant role in the pathomechanism [

2,

20]. Complement activation appears to be associated with type 2 immune response-mediated signaling pathways, as levels of various complement factors, including C3 and H factor, correlate with eosinophil counts [

21,

22]. However, complement is not exclusively linked to this immunological pathway, as it does not fit into any of the asthma groups defined based on the protein profiles or clinical subtypes [

20] (

Figure 3).

Several previous experimental studies have clearly confirmed the activation of the complement cascade in different models of asthma. It should be noted, however, that only a limited amount of data from human studies is available to date. Although the research methods vary, based on our own and others' research results, it can be concluded that in samples of asthmatic patients, the levels of complement-regulating proteins (factor I and its cofactor, factor H), especially factor H, are higher than in healthy control groups [

20,

21].

Furthermore, in a population-based study involving more than 100,000 participants,

Vedel-Krogh et al. demonstrated that higher C3 levels are associated with more severe forms of asthma and the frequency of hospital treatments [

22]. This finding was complemented by an analysis that confirmed elevated C9 and I factor expression in the blood of a large number of severe asthma patients through proteomic testing [

23].

Based on the above, complement factors may serve as biomarkers for distinguishing between subgroups of asthma patients, bringing us closer to personalised treatments [

20]. Furthermore, in addition to the biological therapies already available, treatments that influence the complement system may offer new possibilities [

24].

3.2. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

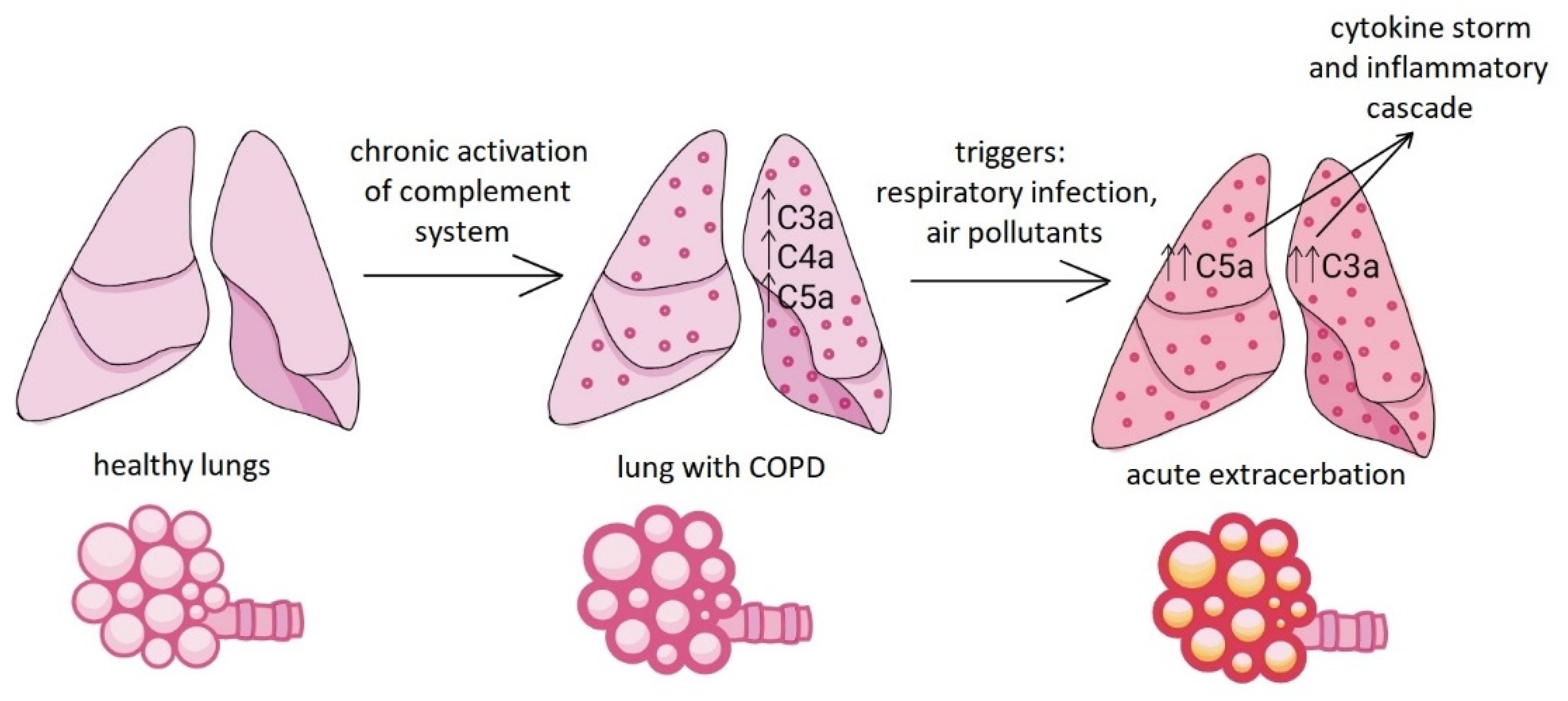

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is also characterised by persistent inflammation of varying intensity in the airways and a gradual deterioration in respiratory function. The inflammation flares up periodically, with these exacerbations usually triggered by respiratory tract infections [

5].

It is well known that smoking plays a clear role in the development of COPD. A study using a mouse model investigated whether the C3 complement component modulates cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in the bronchial epithelium and whether it is involved in the pathogenesis of COPD. Elevated intracellular C3 levels were measured in samples from patients with end-stage COPD. Knockout of C3 exacerbated oxidative stress and apoptosis in 16HBE (human bronchial epithelial cell line) cells exposed to tobacco smoke in vitro. This correlation may indicate a protective effect of C3 in COPD [

25].

Furthermore, it has been shown that serum and sputum levels of C3a, C4a and C5a are higher in stable (i.e. not exacerbated) COPD patients, suggesting that the complement system is chronically activated in these patients [

26].

Another study pointed out that during exacerbations, sputum C3a and C5a levels are higher than at rest, and their increase correlates with the severity of the exacerbation [

27], so the measurable levels of these complement components in sputum may be used as prognostic factors for exacerbation in the future (

Figure 4).

In addition,

Zhang et al. observed significantly lower C1q levels in serum samples from COPD patients than in non-COPD controls [

28]. The decrease in C1q levels was clearly associated with decreased lung function (decreased Tiffeneau index (FEV1/FVC)) and worsening COPD [

29].

In a recent case report,

Kaneko et al. presented the case of a 70-year-old COPD patient with a long history of smoking who developed eosinophilic pneumonia in addition to hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS). HUVS is a rare, autoimmune vasculitis in which the components of the classical complement pathway (particularly C1q and C3) are low, and the condition is often associated with obstructive lung disease. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP), on the other hand, is a rare disease of unknown etiology, often associated with asthma, and is therefore thought to be caused by allergic mechanisms; its development is not usually associated with smoking. The low C3 and C1q levels observed in the presented case, as well as the simultaneous appearance of skin and lung symptoms, suggest that complement system dysregulation may play a role not only in vasculitis associated with immune complex formation, but also in the development of eosinophilic alveolar inflammation. The results suggest a possible link between HUVS, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and long-term smoking [

29].

The data also raises the possibility of complement factors being potential biomarkers or therapeutic targets in COPD.

3.3. Sarcoidosis

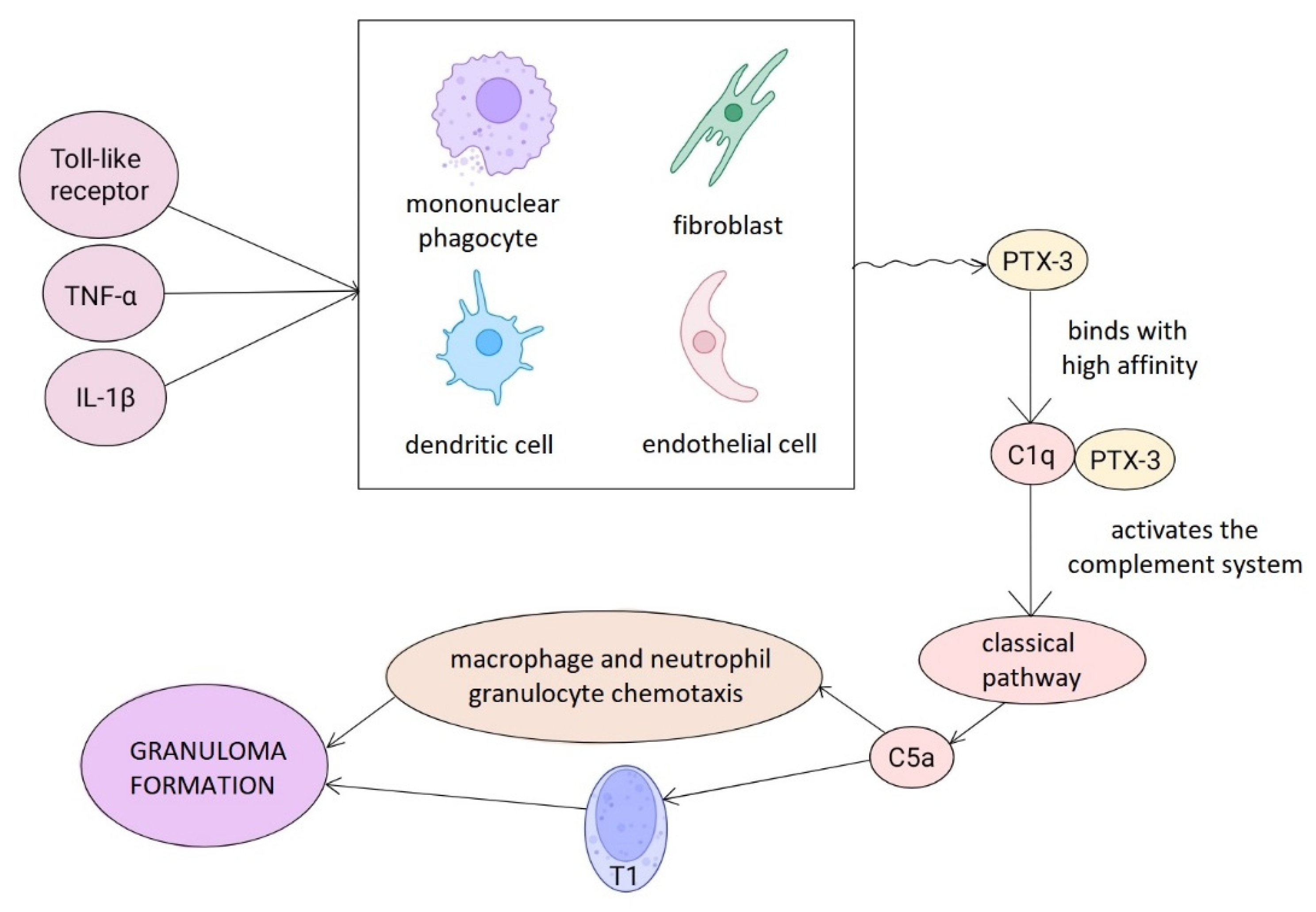

Sarcoidosis is a rare granulomatous inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that primarily affects the chest organs, particularly the lung parenchyma and regional lymph nodes. Although the pathogenesis of the disease is still not fully understood, recent research has increasingly focused on the possible role of the immune system, particularly the complement system, in the development and persistence of the disease process [

30,

31].

Proteomic analyses have shown that complement-activating proteins, mainly factor B, C1q and C3, are significantly enriched in exosomes isolated from BAL samples of sarcoidosis patients, while the expression of the complement regulator CD55 is reduced [

30]. Genetic studies have also linked polymorphisms in the complement receptor 1 (CR1) gene to susceptibility to the disease, although further population studies are needed to confirm these findings [

31]. Peripheral monocytes from patients with sarcoidosis show increased complement receptor expression and elevated phagocytic activity, which may contribute to persistent antigen stimulation and maintenance of granuloma formation [

32]. Furthermore, it has been shown that the concentration of activated C5a in the alveolar compartment of patients with sarcoidosis is significantly higher than in other interstitial lung diseases [

33]. Based on these observations, it appears that complement system activation products may serve as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in sarcoidosis.

Pentraxin 3 (PTX3), an important pattern recognition molecule of innate immunity, can activate the classical pathway of the complement system and is thought to play a key role in the immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis. A study published in 2022 identified PTX3 as a regulator that modulates complement-mediated macrophage activation, thereby limiting the development and progression of granulomatous inflammation [

34].

Human genetic data suggest that PTX3 gene polymorphisms influence granuloma size and inflammatory response intensity [

34]. These findings point to new therapeutic directions, particularly in the development of PTX3-based biological therapies and complement-inhibiting strategies, which may offer promising alternatives to currently limited treatment options (

Figure 5).

4. The Role of the Complement System in the Pathogenesis of Respiratory Malignancies

The development of malignant tumors is the result of a complex, multifactorial and mutation-driven process in which cell cycle regulation is disrupted, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation. In the case of lung cancer, neoplastic transformation is most often caused by carcinogenic compounds found in tobacco smoke, various environmental toxins, and genetic and epigenetic factors [

35]. Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

36].

Tumor cells undergo genetic and epigenetic changes compared to their initial state, and their altered antigen expression makes them recognisable by the immune system. The innate and adaptive branches of the immune system jointly influence the tumor microenvironment, affecting tumor growth, tumor cell selection and immune evasion mechanisms [

37].

Previously, the complement system was considered a complementary element in tumor immunology that increases the effectiveness of antibody-based immunotherapies. However, research over the past decade has revealed that unbalanced complement activation is associated with the development of inflammation around tumors and plays a key role in limiting the antitumour immune response [

37].

One study used publicly available databases to compare the concentration of complement components in plasma and lung cancer tissues. The results suggest that complement system imbalance is a pre-neoplastic condition and may provide an important clue for clinical diagnosis and treatment [

38].

Activation of the cascade can act as a positive or negative regulator in the anti-tumor immune response [

5].

Corrales et al. provided the first evidence of the tumor promoting effect of the system using animal models. In their study, they observed slower tumor growth in cancerous mice using a C5a antagonist. In addition, they found that although C5a did not affect cancer cell division in vitro, it promoted endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis and contributed to the creation of an immunosuppressive environment necessary for tumor growth [

39].

Several studies have suggested the use of complement proteins or activation fragments as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of NSCLC. Previously, C3 levels were identified as a valuable prognostic marker [

36]. Meanwhile, the results of another study suggest that the presence of a specific polymorphism (rs2564978) in CD55 (DAF) may contribute to an increased risk of NSCLC and, within this, significantly increase the risk of adenocarcinoma in the Chinese population [

40].

Not only the presence of complement proteins, but also the epitopes on their surface may have biomarker value. Proteins associated with lung cancer, such as C9, C4b-binding protein (C4BP), α2-HS glycoprotein and H factor, show epitopes associated with lung cancer [

41].

Tornyi et al. identified three different C9 epitopes (BSI0449, BSI0581, BSI0639) that showed negative, neutral and positive associations with non-small cell lung cancer. Based on these results, C9 proteoforms may also be valuable as biomarkers [

35].

Despite significant results, it remains an open question whether complement biomarkers have real clinical value and to what extent they can reliably distinguish between benign and malignant tumors and predict the course of the disease [

37].

Overexpression of the C5a receptor (C5aR) has been demonstrated in several tumor types and has been associated with aggressive tumor characteristics and poor prognosis. In addition, increased C5aR levels have been observed in NSCLC patients who experienced disease progression after initial anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (aPD1). It has been shown that the combined use of anti-PD1 and anti-C5aR antibodies has an enhanced anti-tumor and antimetastatic effect in mice with lung cancer. The combination effectively slowed tumor growth and significantly increased survival in lung cancer mouse models, which was associated with the activation of CD8+ T cells [

42].

Studies focus on the relationship between NSCLC and the complement system; currently, the role of the cascade in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is less well known and less researched.

5. The Role of the Complement System, T2-Type Immune Response, and Eosinophil Cell Interaction in Respiratory Inflammation

According to a study by

Thomas and Lajoie, the complement system, particularly the C3 and C5 components, plays a key role in the development of allergic, T2-type inflammation in the skin, intestines and airways, i.e. in diseases directly related to barrier surfaces in direct contact with the environment [

2].

C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins activate antigen-presenting cells, mainly targeting dendritic cells, and promote the T2 polarisation of naive T cells, thereby enhancing the production of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. These processes contribute to the maintenance of an inflammatory environment, mucosal hyperreactivity and eosinophil recruitment. In addition, C3a and C5a can inhibit the function of regulatory T cells, further increasing the likelihood of T2 dominance [

2].

The anti-inflammatory role of IgG4 antibodies in the type 2 immune response is a good example of how complement system activation can influence the outcome of inflammation. While IgE binds to allergens and triggers powerful effector cell activation and inflammatory processes, IgG4 is unable to effectively activate the complement system due to its specific structural properties. This is because IgG4 binds weakly to C1q and Fcγ receptors, thus failing to initiate the classical complement cascade. All this indirectly suggests that the complement system plays a decisive role in the regulation of the type 2 immune response [

9].

Ogulur et al. describe in detail how, during the T2 immune response, alarmins produced by epithelial cells (TSLP, IL-25, IL-33) activate T2 cells and ILC2 cells, which trigger eosinophilic inflammation by producing IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. IL-5 plays a key role in the maturation and tissue accumulation of eosinophils, while IL-4 and IL-13 contribute to B-cell IgE production and damage to epithelial barriers. In respiratory diseases (such as asthma or chronic rhinosinusitis) eosinophil infiltration, mucus hypersecretion and airway remodeling are the main consequences of T2-mediated inflammation [

9].

Complement system activation and T2-mediated inflammation reinforce each other. C3a and C5a promote IL-5 production and thus eosinophil recruitment to lung tissue, while mediators produced by eosinophils (e.g. cationic proteins, TGF-β) enhance tissue fibrosis and epithelial damage, which induces further complement activation. Anaphylatoxins and cytokines involved in T2 immunity together form a positive feedback loop that maintains chronic inflammation in the airways (

Figure 6).

6. Discussion and Areas of Further Research

In recent years, research into the complement system has brought new perspectives to the immunological understanding of respiratory diseases. The classical view that complement is solely a means of defense against pathogens is now outdated: it is now clear that fine-tuning of the system is essential for maintaining homeostasis, while its dysregulation leads to a wide range of pathological processes.

In infectious diseases, particularly influenza and COVID-19, excessive complement activation can cause overproduction of inflammatory mediators and anaphylatoxins, contributing to acute lung injury and microthrombotic complications. Complement-inhibiting therapies, such as eculizumab or ravulizumab, have shown promising results in mitigating these processes, but their clinical application is still in the experimental phase.

In non-infectious diseases such as asthma, COPD or sarcoidosis, different activation patterns of complement components contribute to the maintenance of chronic inflammation, tissue remodeling and eosinophil infiltration. The signaling pathways mediated by C3a and C5a are closely related to the Th2-type immune response, which supports the importance of the complement-T2-eosinophil axis in the pathomechanism of airway inflammation. Changes in serum levels of complement components and their epitope profiles offer new opportunities for the development of personalised diagnostics and targeted therapies. Furthermore, as local activation of the complement system on the airway surfaces, especially in the epithelial layer is a central feature in the activation of the complement cascade, determination of complement levels in samples obtained directly from the airways has special importance. Non-invasive methods, such as measurements in exhaled breath, have great importance as they are well standardized, easy to use, repeatable, and have no (or minimal) adverse effects [

43,

44].

Kokelj S et al. found signs of activation of the complement and coagulation systems in the airways of asthmatic patients compared to healthy subjects by detecting complement factors and other related molecules in exhaled breath collecting exhaled particles [

45]. This study provides evidence for the potential of exhaled breath biomarker measurement to assess complement activation in the respiratory tract lining fluid. Further studies are required to demonstrate the feasibility of such monitoring to prove that detecting complement activation locally from the airway surfaces could be added to other exhaled breath biomarkers that are already in use diagnosing and monitoring respiratory diseases [

46].

In lung cancer, the dual role of complement – its anti-tumor and tumor-supporting effects – is particularly noteworthy. C5a–C5aR signaling promotes the development of an immunosuppressive microenvironment and angiogenesis, while epitope-level analysis of complement components shows promising biomarker potential. Preclinical models investigating dual blockade of PD-1 and C5aR suggest a new direction for combined immunotherapies. Further studies are required to assess the value of epitope-based approaches both for diagnostic and therapeutical applications.

Overall, the complement system is one of the central but hitherto underappreciated regulatory elements of respiratory diseases. Future research should focus on precisely mapping the mechanisms, clinical validation and optimising the safe use of complement-inhibiting therapies. The diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic use of complement components may usher in a new era in the immunomodulatory approach to respiratory diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zs. Z. and I.H; writing—original draft preparation, Zs. Z.; writing—review and editing, I.T, A.S. and I.H.; visualization, Zs. Z.; supervision, I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

aHUS atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome

ALI acute lung injury

aPD1 anti-PD-(L)1

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

BAL bronchoalveolar lavage

C1 complement factor 1

C2 complement factor 2

C3 complement factor 3

C3a complement factor 3 fragment a

C3b complement factor 3 fragment b

C4 complement factor 4

C4BP C4b-binding protein

C5 complement factor 5

C5a complement factor 5 fragment a

C5aR C5a receptor

CD55 cluster of differentiation 55 (also known as decay-accelerating factor /DAF/)

CR1 complement receptor type 1 (CR1) also known as C3b/C4b receptor or CD35 (cluster of differentiation 35)

CEP chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CT computer tomography

DAF Decay-Accelerating Factor (also known as CD55)

HA haemagglutinin

IL-25 interleukin-25

IL-33 interleuking-33

MAC macrophage complex

MBL mannose-binding lectin

NA neuraminidase

PTX 3 Pentraxin 3

SARS-CoV-2 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

SCLC small cell lung cancer

T2 Type-2

TGF-β Transforming Growth Factor-beta

TMA thrombotic microangiopathy

TSLP Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin

References

- Wang, R.; Lan, C.; Benlagha, K.; et al. The interaction of innate immune and adaptive immune system. Med Comm (2020) 2024, 5, e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.A.; Lajoie, S. Complement's involvement in allergic Th2 immunity: a cross-barrier perspective. J Clin Invest 2025, 135, e188352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, F.A.; Oettgen, H.C. Adaptive immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010, 125, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.K.; Ozantürk, A.N.; Kulkarni, D.H.; et al. Lung epithelial cell-derived C3 protects against pneumonia-induced lung injury. Sci Immunol 2023, 8, eabp9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detsika, M.G.; Palamaris, K.; Dimopoulou, I.; et al. The complement cascade in lung injury and disease. Respir Res 2024, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Jia, B.B.; Li, M.F. Complement C3 and Activated Fragment C3a Are Involved in Complement Activation and Anti-Bacterial Immunity. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 813173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.Q.; Lambris, J.D.; Ricklin, D. Protection of host cells by complement regulators. Immunol Rev 2016, 274, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoermer, K.A.; Morrison, T.E. Complement and viral pathogenesis. Virology 2011, 411, 362–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogulur, I.; Mitamura, Y.; Yazici, D.; et al. Type 2 immunity in allergic diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2025, 22, 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhao, G.; Liu, C.; et al. Inhibition of complement activation alleviates acute lung injury induced by highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2013, 49, 221–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, P.M.; Mukherjee, S.; Al-Mohanna, F.A.; et al. Human Properdin Released By Infiltrating Neutrophils Can Modulate Influenza A Virus Infection. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 747654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez; Gonzalez, S.; Jayasekera, J.P.; Carroll, M.C. Complement and natural antibody are required in the long-term memory response to influenza virus. Vaccine 2008, 26, I86–I93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, P.M.; Kishore, U.; Rajkumari, R. Human C1q Regulates Influenza A Virus Infection and Inflammatory Response via Its Globular Domain. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Java, A.; Apicelli, A.J.; Liszewski, M.K.; et al. The complement system in COVID-19: friend and foe? JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.T.; Ellsworth, C.R.; Qin, X. Emerging role of complement in COVID-19 and other respiratory virus diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 2024, 81, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sahu, S.K.; Cano, M.; et al. Increased complement activation is a distinctive feature of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol 2021, 6, eabh2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabag; Yilmaz, E.; Cebi, M.N.; Karahan, I.; et al. COVID-19 associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Nephrology (Carlton) 2023, 28, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvelli, J.; Demaria, O.; Vély, F.; et al. Association of COVID-19 inflammation with activation of the C5a-C5aR1 axis. Nature 2020, 588, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diurno, F.; Numis, F.G.; Porta, G.; et al. Eculizumab treatment in patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from real life ASL Napoli 2 Nord experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020, 24, 4040–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornyi, I.; Horváth, I. Role of Complement Components in Asthma: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiszhár, Z.; Bikov, A.; Gálffy, G.; et al. Elevated complement factor H levels in asthmatic sputa. J Clin Immunol 2013, 33, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedel-Krogh, S.; Rasmussen, K.L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. Complement C3 and allergic asthma: a cohort study of the general population. Eur Respir J 2021, 57, 2000645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparreman; Mikus, M.; Kolmert, J.; Andersson, L.I.; et al. Plasma proteins elevated in severe asthma despite oral steroid use and unrelated to Type-2 inflammation. Eur Respir J 2022, 59, 2100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.M.E.; Nicklin, A.D.; Stover, C.M. The Value of Targeting Complement Components in Asthma. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020, 56, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qu, J.; et al. Complement component 3 protects human bronchial epithelial cells from cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and prevents incessant apoptosis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1035930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc, M.M.; Korosec, P.; Kosnik, M.; et al. Complement factors c3a, c4a, and c5a in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004, 31, 216–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, J.P.; Mackay, A.J.; Donaldson, G.; et al. The role of complement activation in COPD exacerbation recovery. ERJ Open Res 2016, 2, 00027–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Han, K.; Liu, H.; et al. Circulating Complement C1q as a Novel Biomarker is Associated with the Occurrence and Development of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2022, 17, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Igawa, K. A case of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome complicated by eosinophilic pneumonia: a case report and review of the literature. J Int Med Res 2023, 51, 3000605231189141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Bravo, M.J.; Wahlund, C.J.; Qazi, K.R.; et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis is associated with exosomal vitamin D-binding protein and inflammatory molecules. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017, 139, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzetto, M.; Bombieri, C.; Ferrarotti, I.; et al. Complement receptor 1 gene polymorphisms in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002, 27, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubaniewicz, A.; Typiak, M.; Wybieralska, M.; et al. Changed phagocytic activity and pattern of Fcγ and complement receptors on blood monocytes in sarcoidosis. Hum Immunol 2012, 73, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, S.; Trendelenburg, M.; Tamm, M.; et al. Local and systemic concentrations of pattern recognition receptors of the lectin pathway of complement in a cohort of patients with interstitial lung diseases. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 562564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçales, R.A.; Bastos, H.N.; Duarte-Oliveira, C.; et al. Pentraxin 3 Inhibits Complement-driven Macrophage Activation to Restrain Granuloma Formation in Sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 206, 1140–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornyi, I.; Lazar, J.; Pettko-Szandtner, A.; et al. Epitomics: Analysis of Plasma C9 Epitope Heterogeneity in the Plasma of Lung Cancer Patients and Control Subjects. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; He, S.; He, L.; et al. Complement component 3 is a prognostic factor of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Med Rep 2014, 10, 811–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, E.S.; Mastellos, D.C.; Ricklin, D.; et al. Complement in cancer: untangling an intricate relationship. Nat Rev Immunol 2018, 18, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wu, J.; Lu, F.; et al. The imbalance in the complement system and its possible physiological mechanisms in patients with lung cancer. BMC Cancer Erratum in: BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 269.. 2019, 19, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales, L.; Ajona, D.; Rafail, S.; et al. Anaphylatoxin C5a creates a favorable microenvironment for lung cancer progression. J Immunol 2012, 189, 4674–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, L.; et al. A common CD55 rs2564978 variant is associated with the susceptibility of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 6216–6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, J.; Antal-Szalmas, P.; Kurucz, I.; et al. Large-Scale Plasma Proteome Epitome Profiling is an Efficient Tool for the Discovery of Cancer Biomarkers. Mol Cell Proteomics 2023, 22, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajona, D.; Ortiz-Espinosa, S.; Moreno, H.; et al. A Combined PD-1/C5a Blockade Synergistically Protects against Lung Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horváth, I.; Hunt, J.; Barnes, P. J.; et al. ATS/ERS Task Force on Exhaled Breath Condensate. Exhaled breath condensate: methodological recommendations and unresolved questions. Eur Respir J 26 2005, 523–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I.; Barnes, P.J.; Loukides, S.; et al. A European Respiratory Society technical standard: exhaled biomarkers in lung disease. Eur Respir J 2017, 49, 1600965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokelj, S.; Östling, J.; Fromell, K.; et al. Activation of the Complement and Coagulation Systems in the Small Airways in Asthma. Respiration 2023, 102, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, H; Örlős, Z.; Gellért, Á.; et al. Exhaled Biomarkers for Point-of-Care Diagnosis: Recent Advances and New Challenges in Breathomics. Micromachines 2023, 14, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).