Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

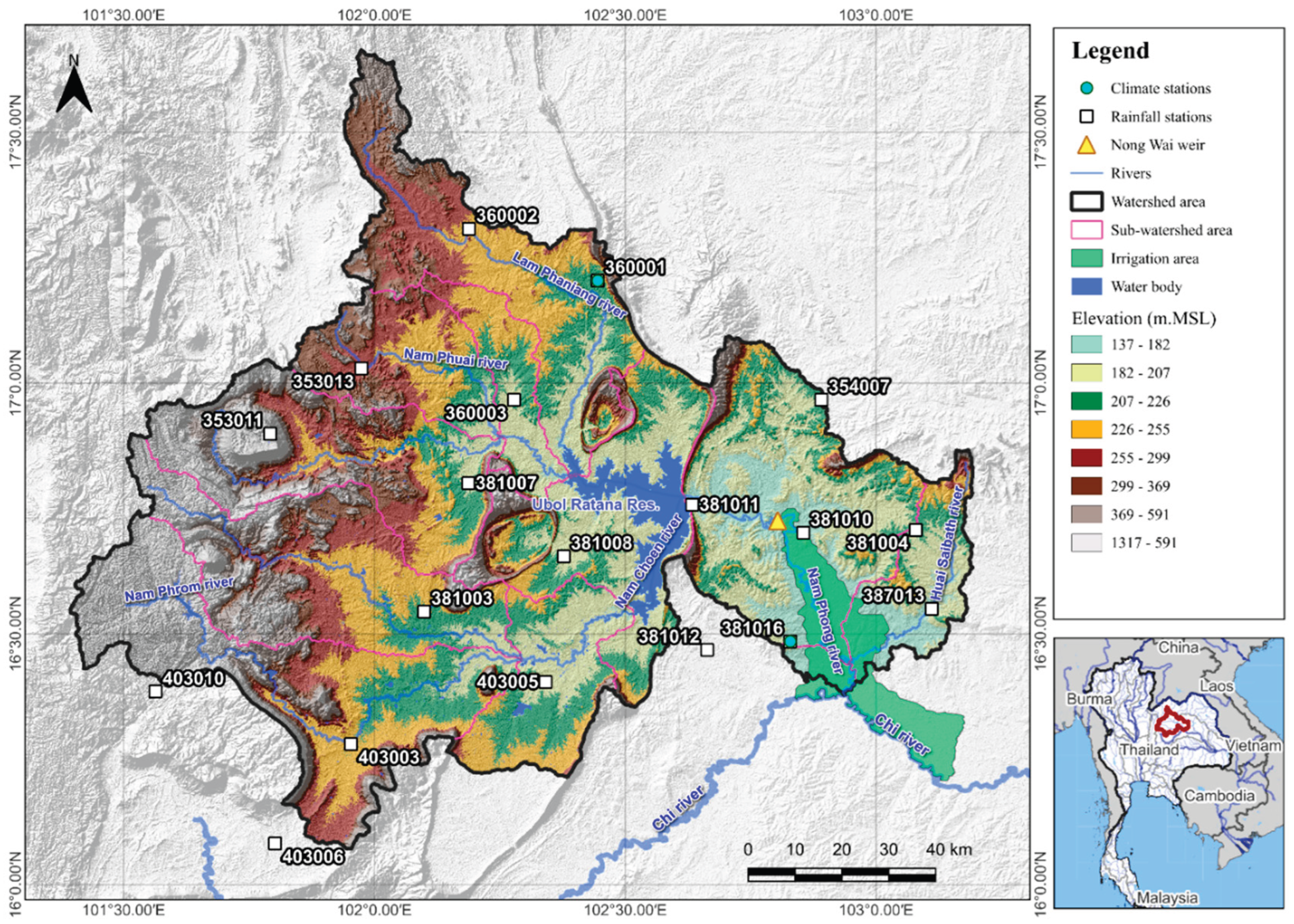

2.1. Study Area

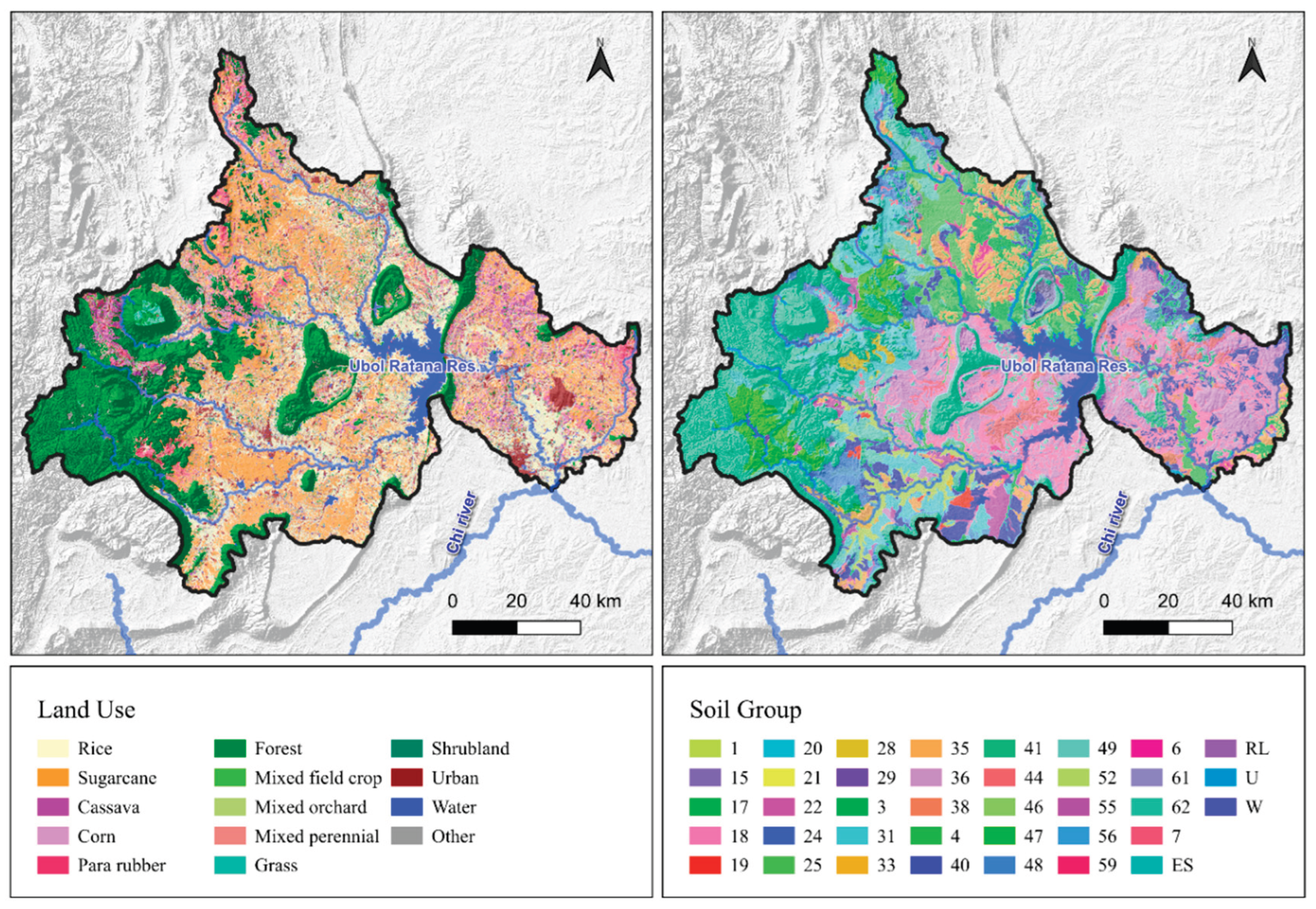

2.2. Spatial Data Collection

2.3. General Circulation Models and Bias Correction

| No. | Model | Resolution (km) | Institute |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ACCESS-CM2 | 250 × 250 | Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Australia [60] |

| 2 | MIROC6 | 250 × 250 | Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate, Japan [61] |

| 3 | MPI-ESM1-2-LR | 250 × 250 | Max Planck Institute for Meteorology, Germany [62] |

2.4. Reservoir Inflow Analysis Using WEAP

2.4.1. Principle of WEAP

- Surface runoff is calculated from total runoff using Equation (2):

- Interflow can be calculated by using Equation (3):

- Baseflow is calculated using Equation (4):

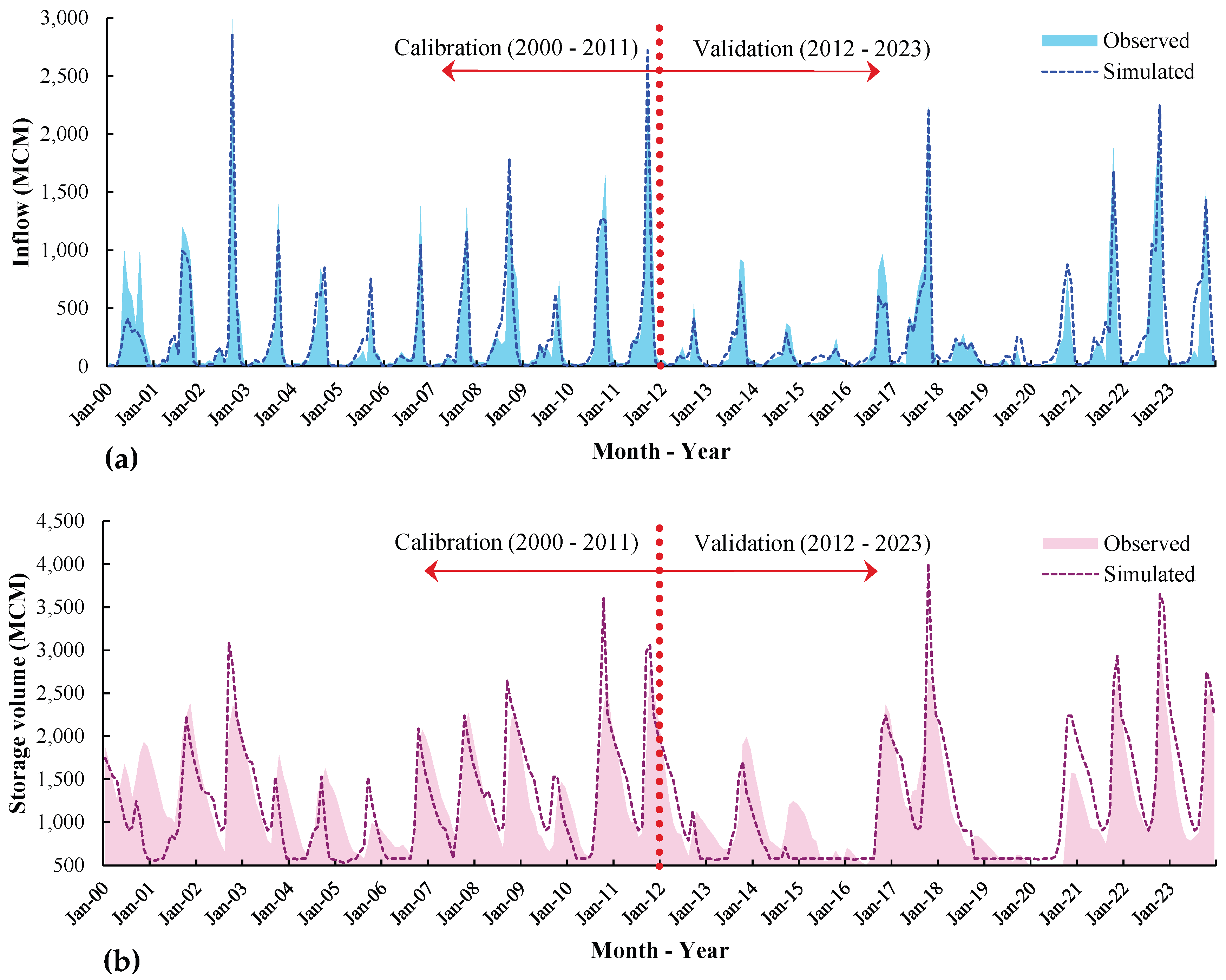

2.4.2. Model Calibration and Validation

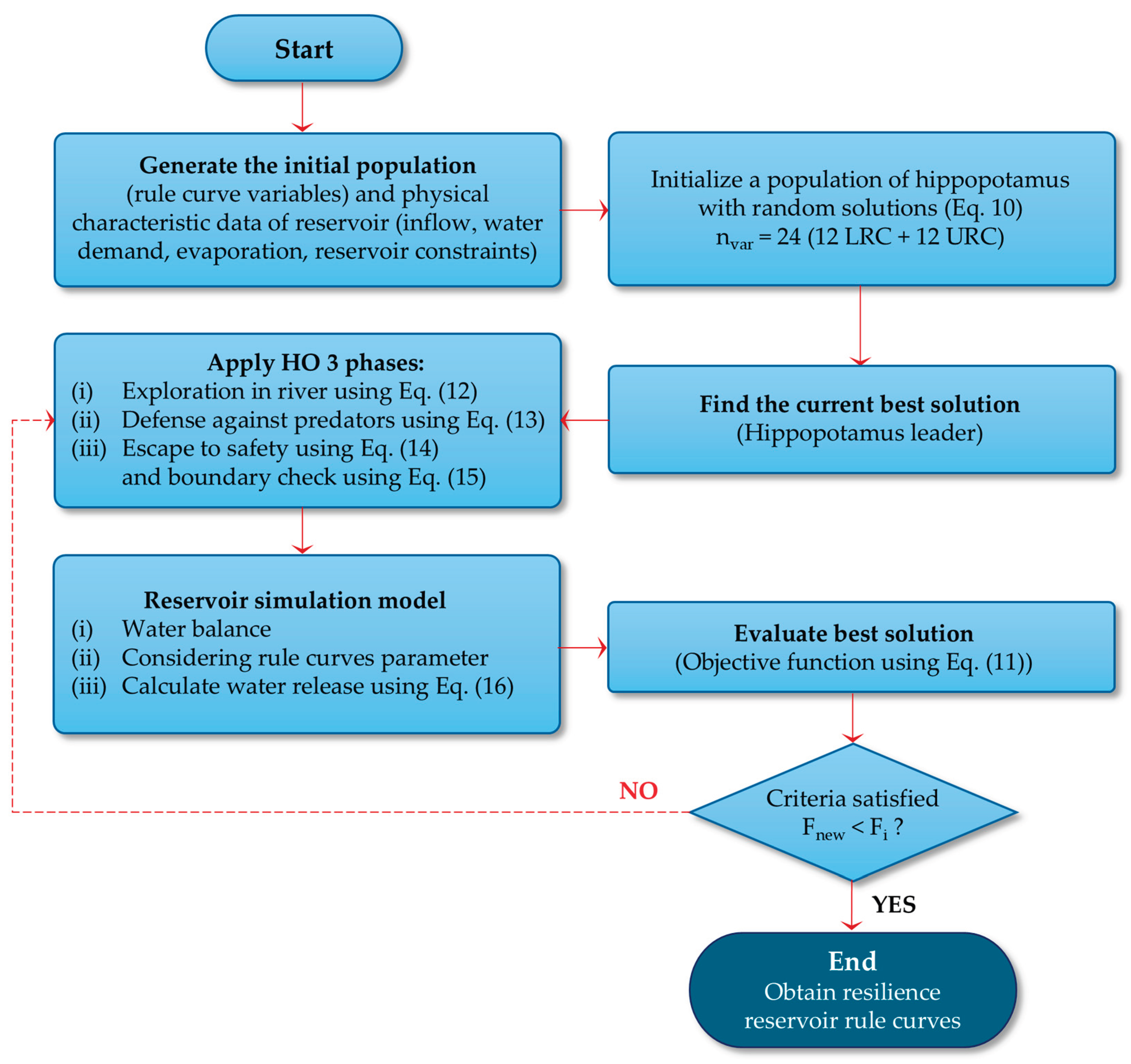

2.5. Hippopotamus Optimization Connected with Reservoir Simulation Model for Optimal Resilience Rule Curves

3. Results and Discussions

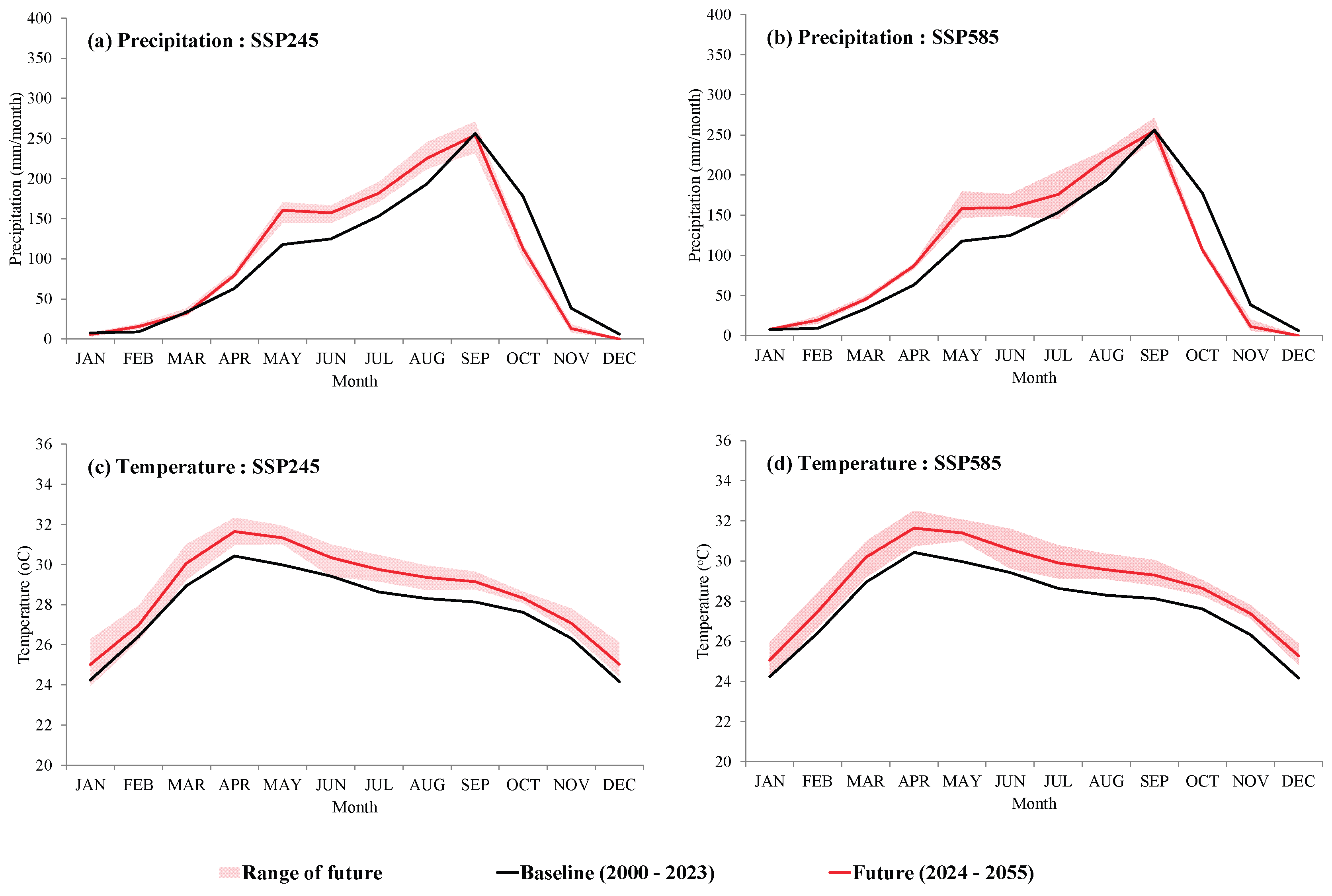

3.1. Climate Change Analysis

3.1.1. Future Precipitation

3.1.2. Future Temperatures

3.2. Simulation of Future Inflow into Reservoir by WEAP

3.2.1. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters

3.2.2. Efficiency and Precision of WEAP

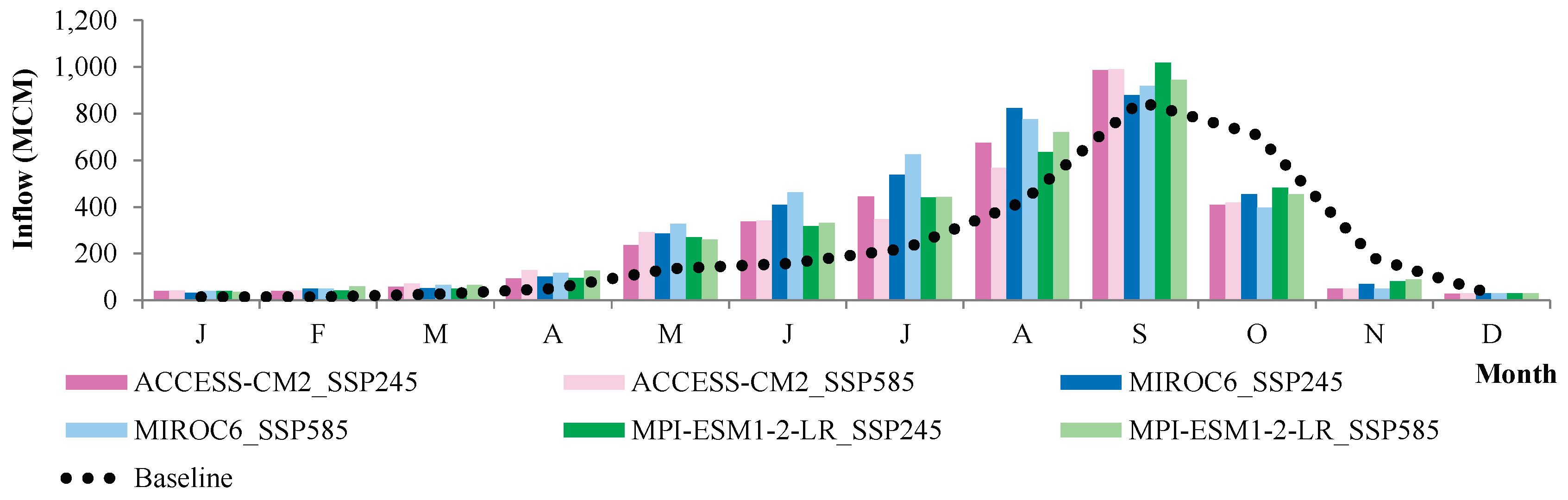

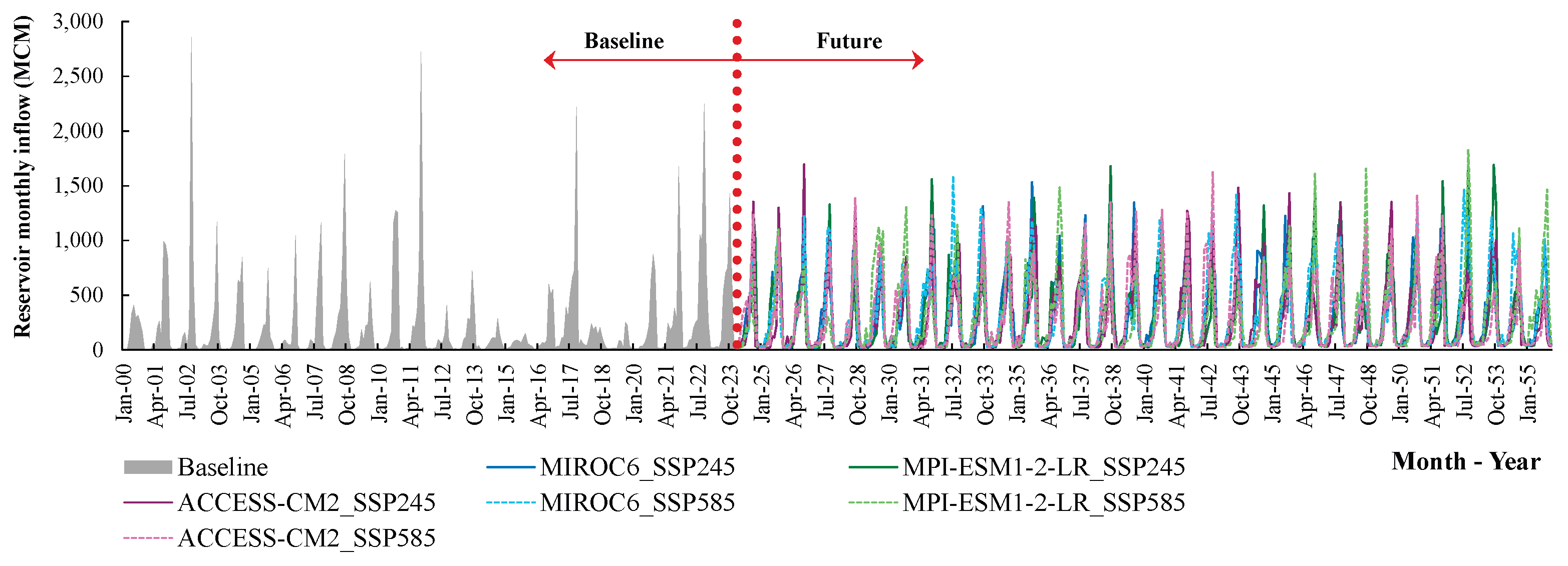

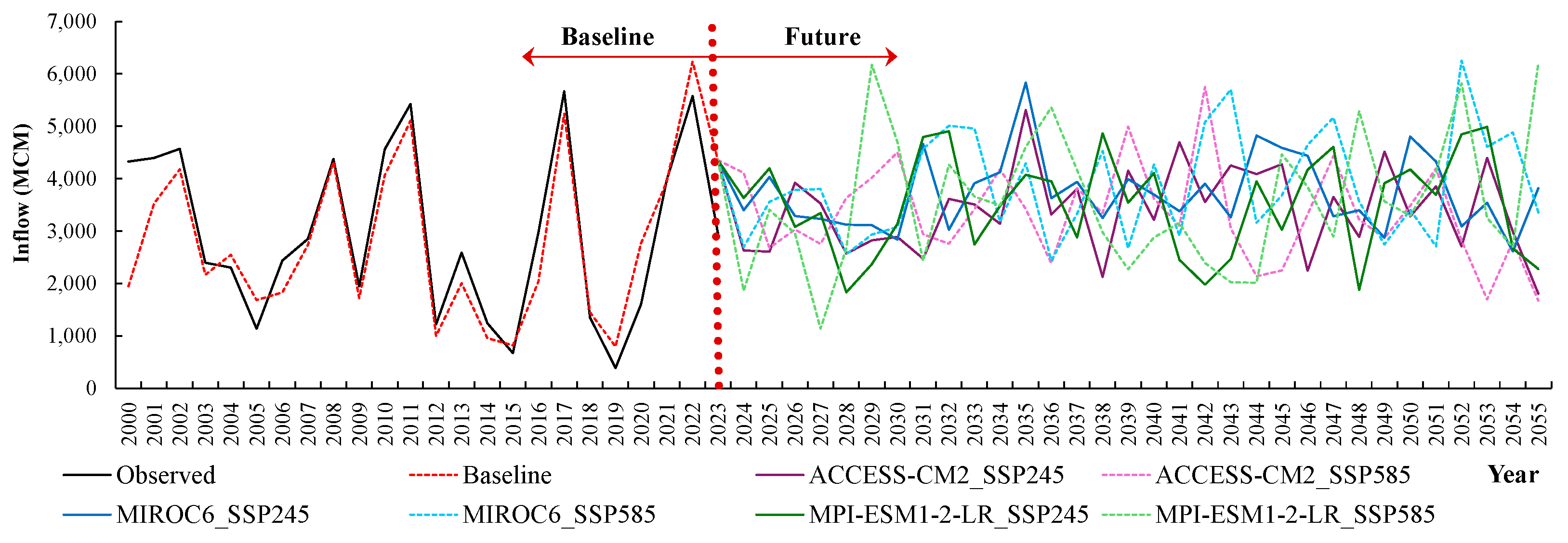

3.2.3. Future Inflow of Ubolrat Reservoir

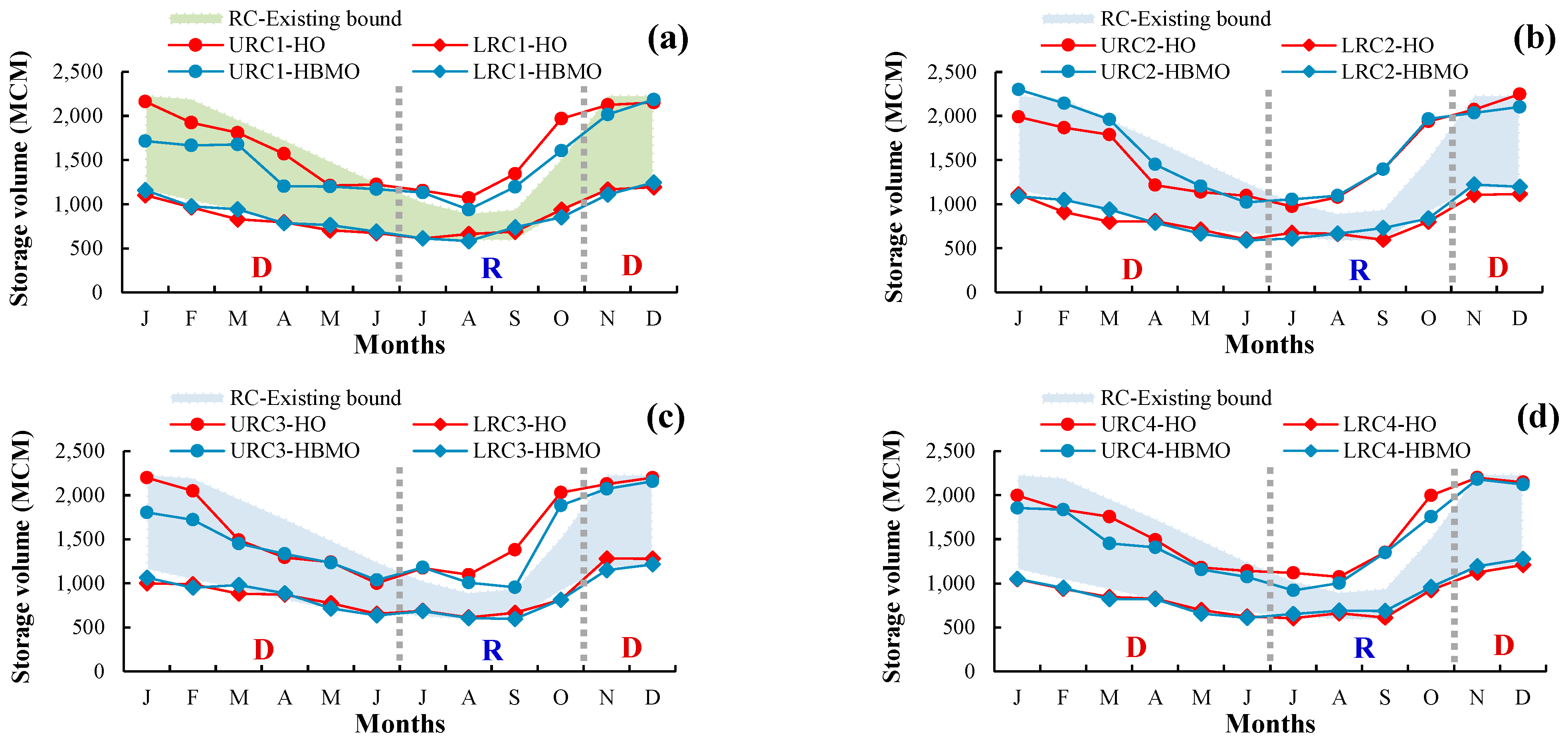

3.3. Development of Resilience Reservoir Operation Rule Curves

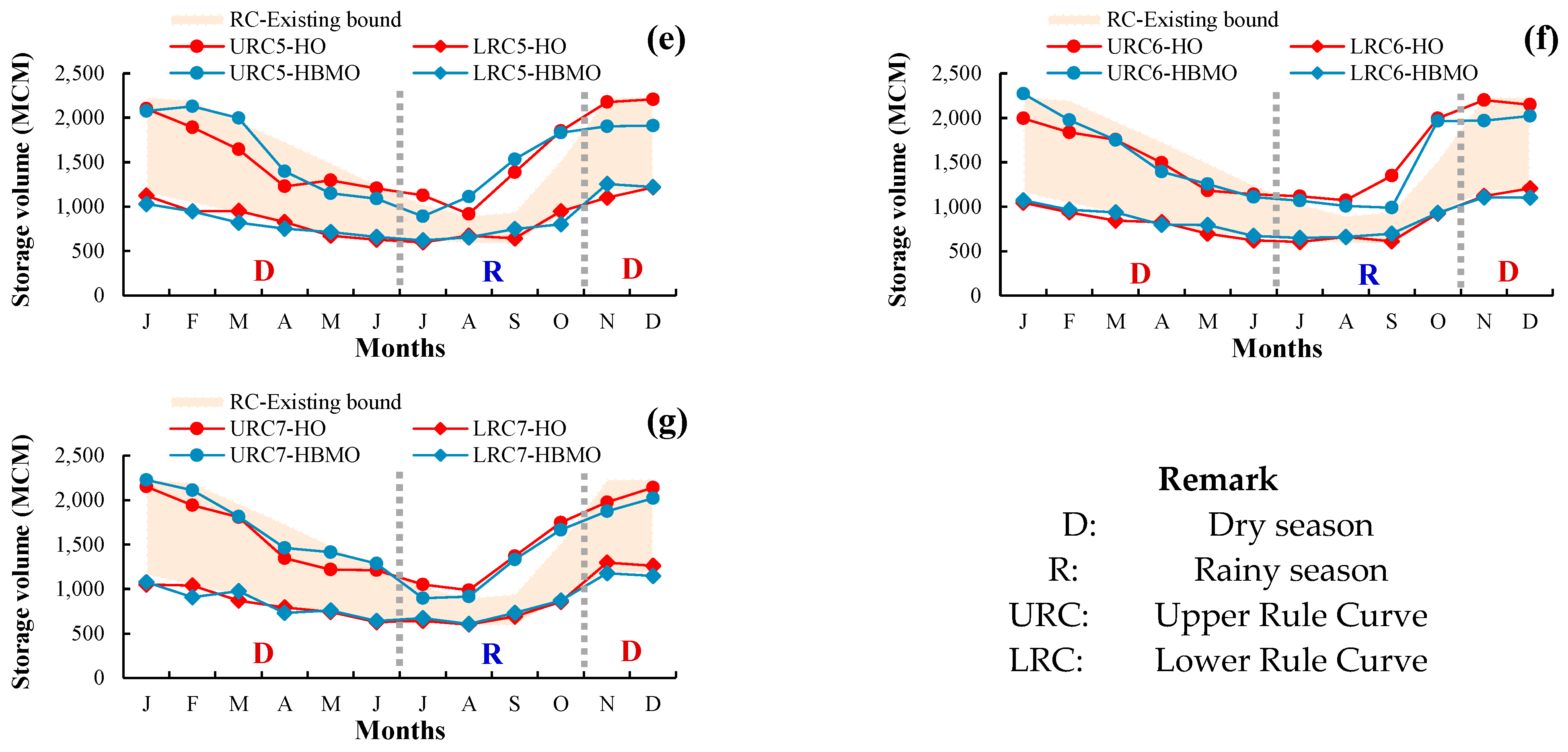

3.3.1. Upper Rule Curve for Rainy Season

3.3.2. Lower Rule Curve for Dry Season

3.3.3. Comparison between Developed Rule Curves

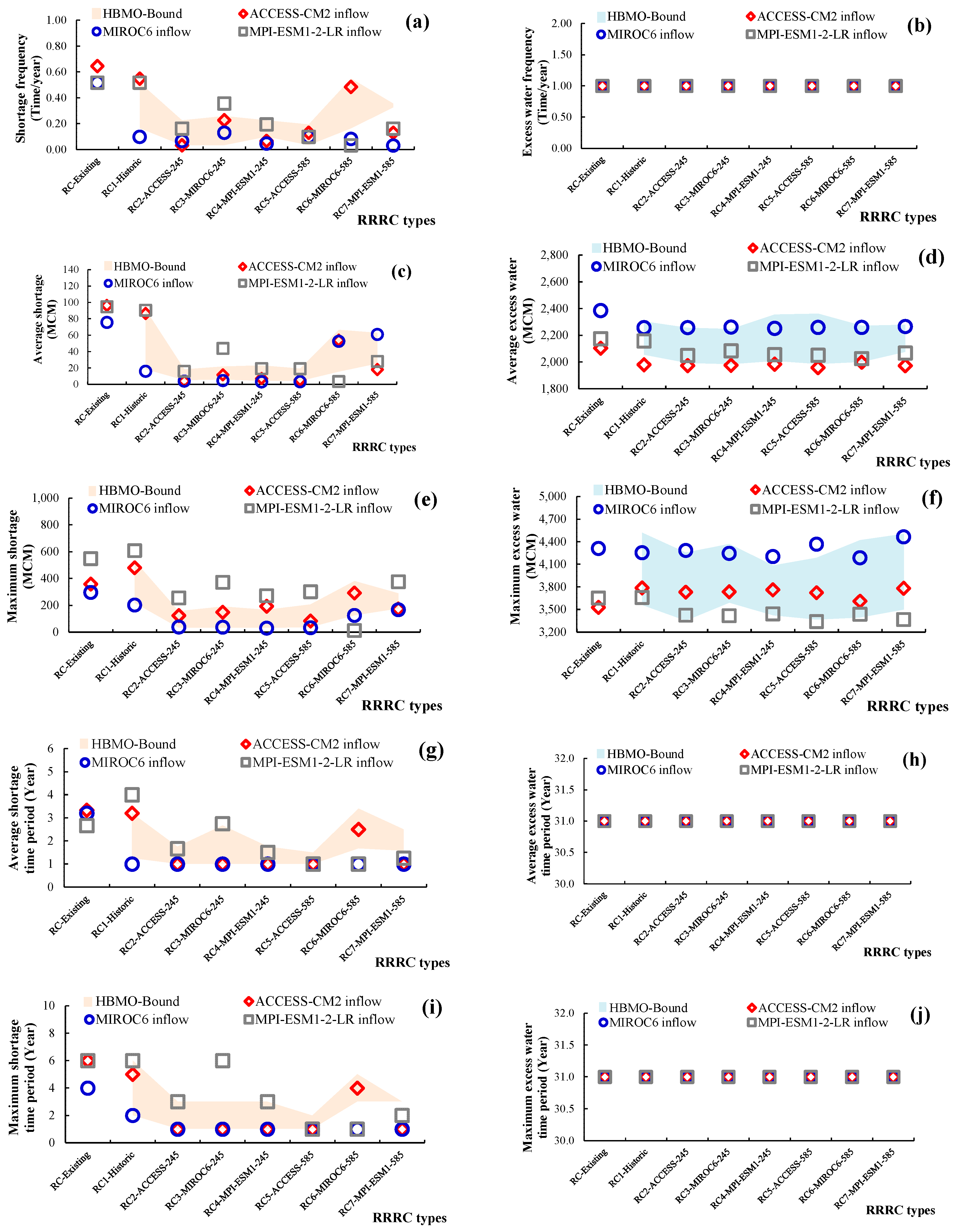

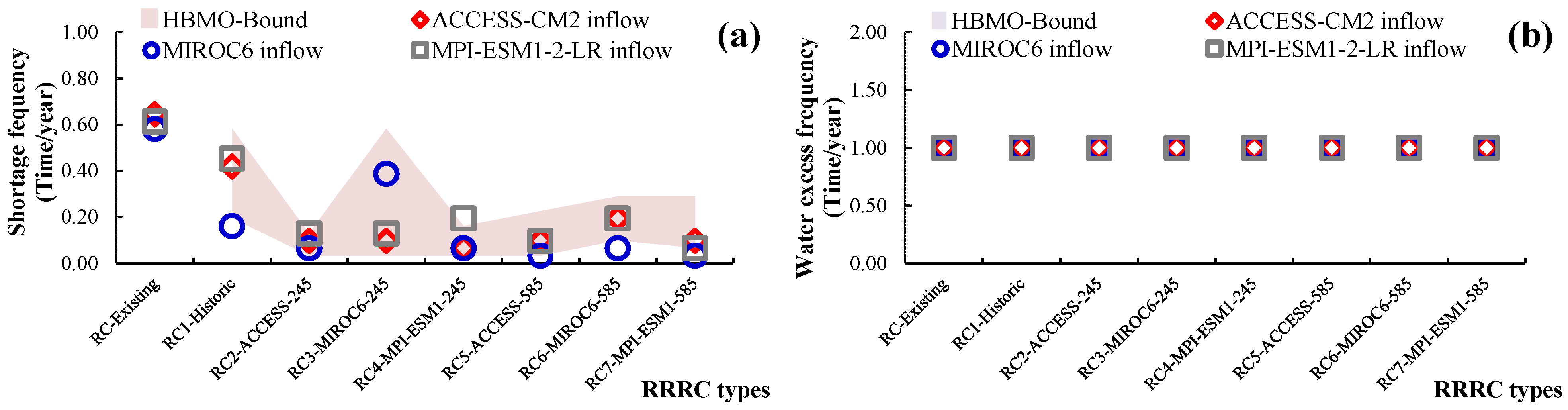

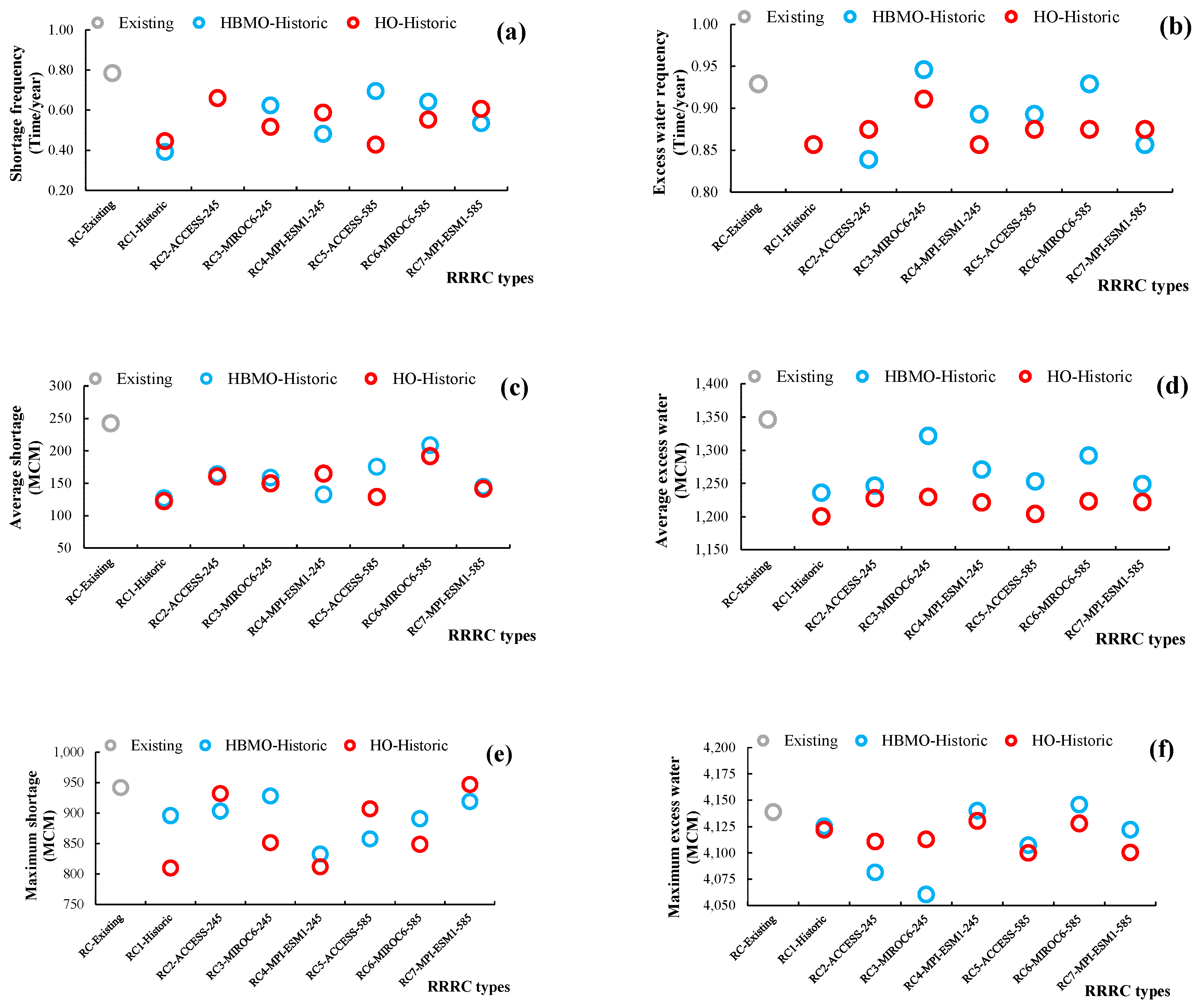

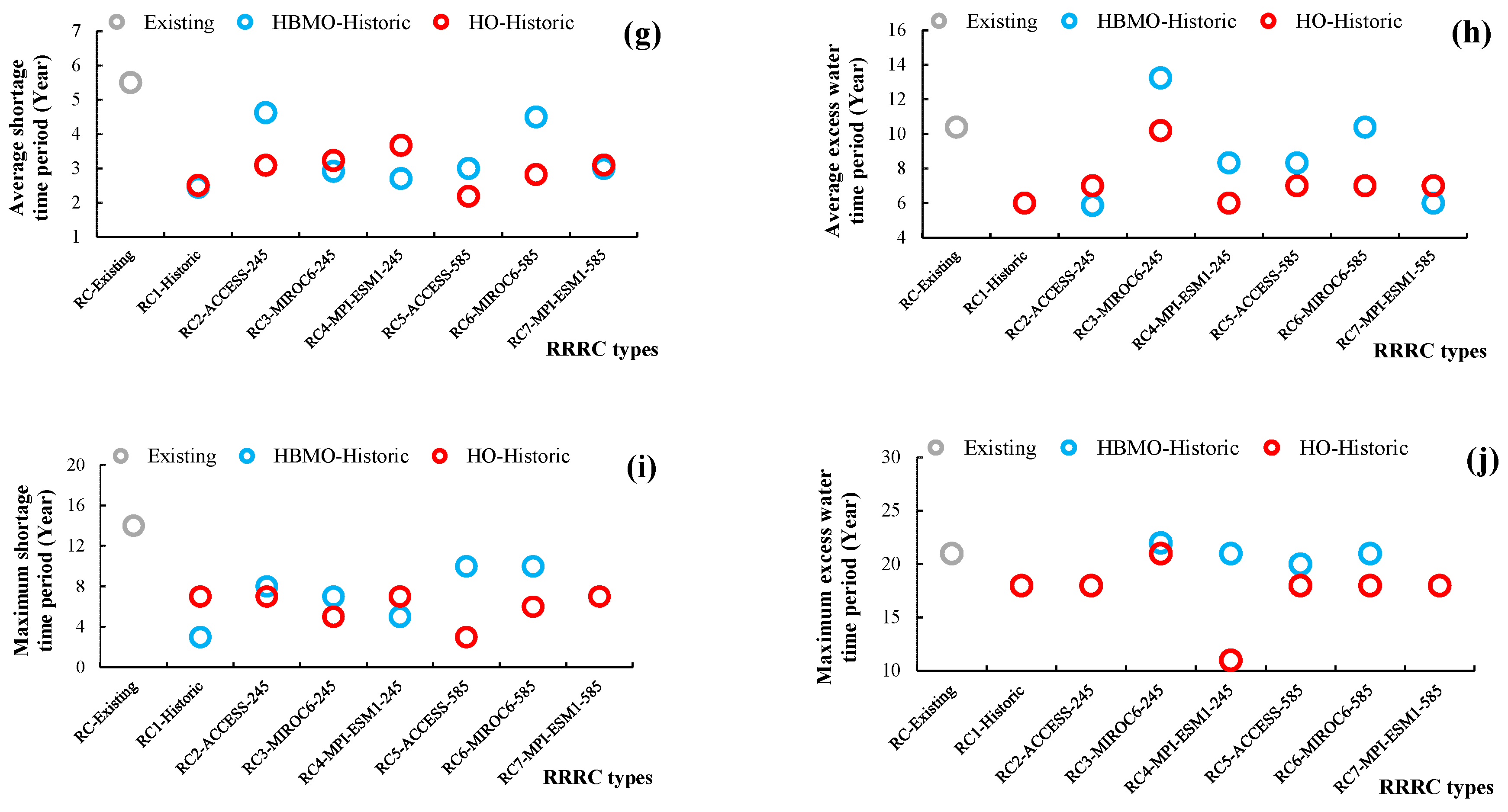

3.4. Efficiency Assessment of Resilience Reservoir Rule Curves under Variable Hydrological Situations

3.4.1. Efficiency of Rule Curves Developed by HO under Historic Inflow

3.4.2. Efficiency of Rule Curves Developed by HO under Inflow of SSP245

3.4.4. Efficiency of Rule Curves Developed by HO under Inflow of SSP585

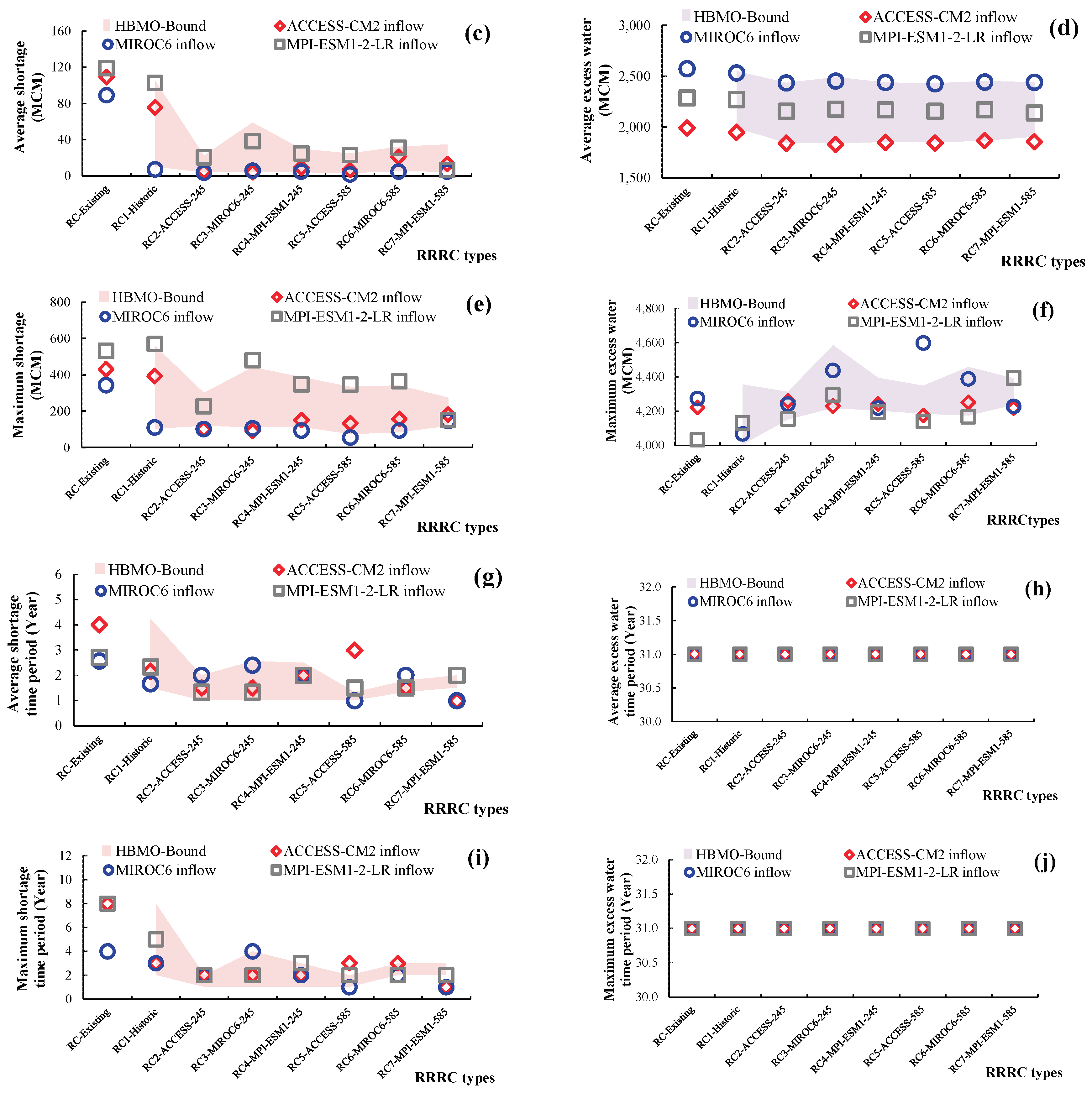

3.4.5. Efficiency Comparison of Resilience Reservoir Rule Curves under Climate Change

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| WEAP | Water Evaluation and Planning |

| GCMs | General Circulation Models |

| SSP | Shared Socioeconomic Pathways |

| CMIP6 | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 |

| NEX-GDDP | NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections |

| ACCESS-CM2 | Australian Community Climate and Earth System Simulator, Coupled Model version 2 |

| MIROC6 | Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate, version 6 |

| MPI-ESM1-2-LR | Max Planck Institute Earth System Model (Version 1.2) - Low Resolution |

| HO | Hippopotamus Optimization |

| HBMO | Honey Bee Mating Optimization |

| RRRC | Resilience Reservoir Rule Curve |

| RC | Rule Curves |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| EGAT | Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand |

| RID | Royal Irrigation Department |

| LDD | Land Development Department |

| TMD | Thai Meteorology Department |

| MCM | Million Cubic Meters |

| sq.km | Square Kilometers |

References

- Water for Development and Development for Water: Realizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Vision. Aquat. Procedia 2016, 6, 106–110. [CrossRef]

- Evaristo, J.; Jameel, Y.; Tortajada, C.; Wang, R.Y.; Horne, J.; Neukrug, H.; David, C.P.; Fasnacht, A.M.; Ziegler, A.D.; Biswas, A. Water Woes: the Institutional Challenges in Achieving SDG 6. Sustain. Earth. Rev. 2023, 6(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songsaengrit, S.; Kangrang, A. Dynamic Rule Curves and Streamflow under Climate Change for Multipurpose Reservoir Operation using Honey-bee Mating Optimization. Sustainability 2022, 14(14), 8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangrang, A.; Prasanchum, H.; Sriworamas, K.; Ashrafi, S.M.; Hormwichian, R.; Techarungruengsakul, R.; Ngamsert, R. Application of Optimization Techniques for Searching Optimal Reservoir Rule Curves: A Review. Water 2023, 15(9), 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beça, P.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Nunes, J.P.; Diogo, P; Mujtaba, B. Optimizing Reservoir Water Management in a Changing Climate. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37(9), 3423–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.B.; Mangoua, O.M.J.; Georges, E.S.; Kane, A.; Goula, B.T.A. Using “Water Evaluation and Planning” (WEAP) Model to Simulate Water Demand in Lobo Watershed (Central-Western Cote d'Ivoire). J. Water Resour. Prot. 2021, 13, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera Abdi, D.; Ayenew, T. Evaluation of the WEAP Model in Simulating Subbasin Hydrology in the Central Rift Valley Basin, Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougahi, J.H.; Karim, S.; Mahmood, S.A. Application of the SWAT Model to Assess Climate and Land Use/cover Change Impacts on Water Balance Components of the Kabul River Basin, Afghanistan. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2022, 13, 3977–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, S.; Mazzoni, A.; Elomri, A.; Aouissi, J.; Boufekane, A.; Zghibi, A. A Review of Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) Studies of Mediterranean Catchments: Applications, Feasibility, and Future Directions. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 326, 116799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareta, K. Hydrological Modelling of Largest Braided River of India Using MIKE Hydro River Software with Rainfall Runoff, Hydrodynamic and Snowmelt Modules. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2023, 14(4), 1314–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; Lai, Y. Hydrological Simulation of the Jialing River Basin using the MIKE SHE Model in changing climate. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, 2495–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhe, F.T.; Melesse, A.M.; Hailu, D.; Sileshi, Y. MODSIM-based Water Allocation Modeling of Awash River Basin, Ethiopia. CATENA 2013, 109, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supharatid, S.; Nafung, J. Projected Drought Conditions by CMIP6 Multimodel Ensemble over Southeast Asia. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2021, 12(7), 3330–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Dai, A. CMIP6 Model-projected Hydroclimatic and Drought Changes and Their Causes in the Twenty-First Century. J. Clim. 2022, 35, 897–921. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, V.; Huang, Y.F.; Koo, C.H.; Ahmed, A.N.; El-Shafie, A. A Review of Reservoir Operation Optimisations: from Traditional Models to Metaheuristic Algorithms. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29(5), 3435–3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasanchum, H.; Kangrang, A. Optimal Reservoir Rule Curves under Climatic and Land Use Changes for Lampao Dam Using Genetic Algorithm. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22(1), 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadianfar, I.; Zamani, R. Assessment of the Hedging Policy on Reservoir Operation for Future Drought Conditions under Climate Change. Clim. Chang. 2020, 159(2), 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashofteh, P.S.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Loáiciga, H.A. Logical Genetic Programming (LGP) Application to Water Resources Management. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 192(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, A.; Massoumi, F.; Afshar, A.; Mariño, M.A. State of the Art Review of Ant Colony Optimization Applications in Water Resource Management. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 3891–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garousi-Nejad, I.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Loáiciga, H.A.; Mariño, M.A. Application of the Firefly Algorithm to Optimal Operation of Reservoirs with the Purpose of Irrigation Supply and Hydropower Production. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2016, 142(10), 04016041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehteram, M.; Mousavi, S.F.; Karami, H.; Farzin, S.; Celeste, A.B.; Shafie, A.E. Bat Algorithm for Dam–Reservoir Operation. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77(13), 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donyaii, A; Sarraf, A.; Ahmadi, H. Water Reservoir Multiobjective Optimal Operation Using Grey Wolf Optimizer. Shock Vib. 2020, 8870464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandideh-Tehrani, M.; Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Loáiciga, H.A. Application of Particle Swarm Optimization to Water Management: an Introduction and Overview. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192(5), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Chang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Multi-Objective Hydropower Station Operation Using an Improved Cuckoo Search Algorithm. Energy 2019, 168, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri-Atrabi, H.; Qaderi, K.; Rheinheimer, D.E.; Sharifi, E. Application of Harmony Search Algorithm to Reservoir Operation Optimization. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29(15), 5729–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, M.; Nazif, S.; Mousavi, S.F.; Karami, H.; Daccache, A. A Hybrid Constrained Coral Reefs Optimization Algorithm with Machine Learning for Optimizing Multi-Reservoir Systems Operation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadieh, B.; Afshar, A. Optimization of Water-Supply and Hydropower Reservoir Operation Using the Charged System Search Algorithm. Hydrology 2019, 6(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, M.; Lamontagne, J.R.; Reed, P.M.; Castelletti, A. A State-of-the-Art Review of Optimal Reservoir Control for Managing Conflicting Demands in a Changing World. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57(12), e2021WR029927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormwichian, R.; Kaewplang, S.; Kangrang, A.; Supakosol, J.; Boonrawd, K.; Sriworamat, K.; Muangthong, S.; Songsaengrit, S.; Prasanchum, H. Understanding the Interactions of Climate and Land Use Changes with Runoff Components in Spatial-Temporal Dimensions in the Upper Chi Basin, Thailand. Water 2023, 15(19), 3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, C.; Gironas, J.; Barría, P.; Vicuña, S.; Meza, F. Assessing Reservoir Performance under Climate Change. When Is It Going to Be Too Late If Current Water Management Is Not Changed? Water 2020, 13(1), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touseef, M.; Chen, L.; Yang, W. Assessment of Surface Water Availability under Climate Change Using Coupled SWAT-WEAP in Hongshui River Basin, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10(5), 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadri, A.; Saidi, M.E.M.; El Khalki, E.M.; Aachrine, B.; Saouabe, T.; Elmaki, A.A. Integrated Water Management under Climate Change through the Application of the WEAP Model in a Mediterranean Arid Region. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2022, 13(6), 2414–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamkhani, A.; Shourian, M.; Moridi, A. Optimal Design and Operation of a Hydropower Reservoir Plant Using a WEAP-Based Simulation–Optimization Approach. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35(5), 1637–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allani, M.; Mezzi, R.; Zouabi, A.; Béji, R.; Joumade-Mansouri, F.; Hamza, M.E.; Sahli, A. Impact of Future Climate Change on Water Supply and Irrigation Demand in a Small Mediterranean Catchment. Case Study: Nebhana Dam System, Tunisia. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2020, 11(4), 1724–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraei, I.; Safavi, H.R.; Dandy, G.C.; Golmohammadi, M.H. Integrated Simulation-Optimization Framework for Water Allocation Based on Sustainability of Surface Water and Groundwater Resources. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2021, 147(3), 05021001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Lü, H.; Ahmed, S.; Nabi, G.; Wajid, M.A.; Shakoor, A.; Farid, H.U. Irrigation Supply and Demand, Land Use/Cover Change and Future Projections of Climate, in Indus Basin Irrigation System, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13(16), 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opere, A.O.; Waswa, R.; Mutua, F.M. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change on Surface Water Resources Using WEAP Model in Narok County, Kenya. Front. Water 2022, 3, 789340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Patil, J.P.; Goyal, V.C.; Singh, A. Assessment of Water Supply–Demand Using Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) Model for Ur River Watershed, Madhya Pradesh, India. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A 2019, 100(1), 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abungba, J.A.; Adjei, K.A.; Gyamfi, C.; Odai, S.N.; Pingale, S.M.; Khare, D. Implications of Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Climate Change on Black Volta Basin Future Water Resources in Ghana. Sustainability 2022, 14(19), 12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyebi, M.; Sharafati, A.; Nazif, S.; Raziei, T. Assessment of Adaptation Scenarios for Agriculture Water Allocation under Climate Change Impact. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37(9), 3527–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesgari, E.; Hosseini, S.A.; Hemmesy, M.S.; Houshyar, M.; Partoo, L.G. Assessment of CMIP6 Models' Performances and Projection of Precipitation Based on SSP Scenarios over the MENAP Region. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2022, 13(10), 3607–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Chen, J.; Xiong, L. A Comparison of CMIP5 and CMIP6 Climate Model Projections for Hydrological Impacts in China. Hydrol. Res. 2023, 54(3), 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.H.; Ashofteh, P.S.; Loáiciga, H.A. Optimal Water Allocation of Surface and Ground Water Resources under Climate Change with WEAP and IWOA Modeling. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 36(9), 3181–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Xuan, Y.; Bailey, R.T. Assessing Climate Change Impact on Water Resources in Water Demand Scenarios Using SWAT-MODFLOW-WEAP. Hydrology 2022, 9(10), 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Try, S.; Tanaka, S.; Tanaka, K.; Sayama, T.; Khujanazarov, T.; Oeurng, C. Comparison of CMIP5 and CMIP6 GCM Performance for Flood Projections in the Mekong River Basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 40, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, S.; Sayama, T.; Try, S. Integrated Impact Assessment of Climate Change and Hydropower Operation on Streamflow and Inundation in the Lower Mekong Basin. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2023, 10(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikha-BagemGhaleh, S.; Babazadeh, H.; Rezaie, H.; Sarai-Tabrizi, M. The Effect of Climate Change on Surface and Groundwater Resources Using WEAP-MODFLOW Models. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13(6), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Dhaqane, A.; Murshed, M.F.; Mourad, K.A.; Abd Manan, T.S.B. Assessment of the Streamflow and Evapotranspiration at Wabiga Juba Basin Using a Water Evaluation and Planning (WEAP) Model. Water 2023, 15(14), 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RaziSadath, P.V.; RinishaKartheeshwari, M.; Elango, L. WEAP Model Based Evaluation of Future Scenarios and Strategies for Sustainable Water Management in the Chennai Basin, India. AQUA—Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 2023, 72(11), 2062–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, M.H.; Mehrabi Hashjin, N.; Montazeri, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Khodadadi, N. Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm: A Novel Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.; Wang, H.; Li, T.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Y. MHO: A Modified Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm for Global Optimization and Engineering Design Problems. Biomimetics 2025, 10(2), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aribowo, W.; Mzili, T.; Sabo, A. Enhanced Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm for Power System Stabilizers. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2025, 38(1), 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P.; Tiwari, P.; Pratap, A. Application of the Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm for Distribution Network Reconfiguration with Distributed Generation Considering Different Load Models for Enhancement of Power System Performance. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107(4), 3909–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.M. A State-of-the-Art Review of Heuristic and Metaheuristic Optimization Techniques for the Management of Water Resources. Water Supply 2022, 22(4), 3702–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, G.P.; Loucks, D.P. Adaptive Water Resources Management Under Climate Change: An Introduction. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 37(6), 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguy, M.; Eastman, M.; Magee, E.; Barker, L.J.; Chitson, T.; Ekkawatpanit, C.; Goodwin, D.; Hannaford, J.; Holman, I.; Pardthaisong, L.; Parry, S.; Rey Vicario, D.; Visessri, S. Indicator-to-Impact Links to Help Improve Agricultural Drought Preparedness in Thailand. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 2419–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, B.; Wang, W.; Michaelis, A.; Melton, F.; Lee, T.; Nemani, R. NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 2022, 9(1), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, B.C.; Tebaldi, C.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Eyring, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hurtt, G.; Knutti, R.; Kriegler, E.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Lowe, J.; Meehl, G.A.; Moss, R.; Riahi, K.; Sanderson, B.M. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 3461–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Jiao, D.; Yang, X.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 in Simulation Performance and Drought Capture Utility over China – Based on DISO. Hydrol. Res. 2023, 54(5), 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, M.; Bi, D.; Dobrohotoff, P.; Fiedler, R.; Harman, I.; Law, R.; Mackallah, C.; Marsland, S.; O'Farrell, S.; Rashid, H.; Srbinovsky, J. CSIRO-ARCCSS ACCESS-CM2 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shiogama, H.; Abe, M.; Tatebe, H. MIROC MIROC6 model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP ssp245. 2019, (No Title).

- Wieners, K.H.; Giorgetta, M.; Jungclaus, J.; Reick, C.; Esch, M.; Bittner, M.; Gayler, V.; Haak, H.; de Vrese, P.; Raddatz, T.; Mauritsen, T. MPI-m MPIESM1. 2-LR model output prepared for CMIP6 ScenarioMIP. 2019, (No Title).

- Shaabani, M.K.; Abedi-Koupai, J.; Eslamian, S.S.; Gohari, S.A.R. Simulation of the Effects of Climate Change, Crop Pattern Change, and Developing Irrigation Systems on the Groundwater Resources by SWAT, WEAP and MODFLOW Models: A Case Study of Fars Province, Iran. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26(4), 10485–10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, T.M.; Mwaanga, P.; Nguvulu, A. Hydrological Modelling and Water Resources Assessment of Chongwe River Catchment using WEAP model. Water 2019, 11(4), 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormwichian, R.; Tongsiri, J.; Kangrang, A. Multipurpose Rule Curves for Multipurpose Reservoir by Conditional Genetic algorithm. Int. Rev. Civ. Eng. 2018, 9(3), 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriworamas, K.; Prasanchum, H.; Ashrafi, S.M.; Hormwichian, R.; Techarungruengsakul, R.; Ngamsert, R.; Chaiyason, T.; Kangrang, A. Concern Condition for Applying Optimization Techniques with Reservoir Simulation Model for Searching Optimal Rule Curves. Water 2023, 15(13), 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryani, I.G.A.P. Sensitivity Analysis in Parameter Calibration of the WEAP Model for Integrated Water Resources Management in Unda Watershed. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriasi, D.N.; Gitau, M.W.; Pai, N.; Daggupati, P. Hydrologic and Water Quality Models: Performance Measures and Evaluation Criteria. Trans. ASABE 2015, 58(6), 1763–1785. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Alberti, S.; Abarca-del-Río, R.; Bornhardt, C.; Ávila, A. Development and Validation of a Model to Evaluate the Water Resources of a Natural Protected Area as a Provider of Ecosystem Services in a Mountain Basin in Southern Chile. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 8, 539905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Verma, M.K.; Kumre, S.K. A Hybrid Technique to Enhance the Rainfall-Runoff Prediction of Physical and Data-Driven Model: A Case Study of Upper Narmada River Sub-basin, India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26368. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, S.S.; Sahoo, B.; Raghuwanshi, N.S. An Integrated Reservoir Operation Framework for Enhanced Water Resources Planning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Data Type | Resolution | Year | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | 30 × 30 m | 2017 | SRTM (Earth Resource Observation and Science (EROS) Center) |

| 2 | Land use | 30 x 30 m | 2019 | Land Development Department (LDD) |

| 3 | Soil group | 30 x 30 m | 2018 | Land Development Department (LDD) |

| 4 | Precipitation | Daily | 2000 – 2023 | Thai Meteorological Department (TMD) |

| 5 | Inflow in reservoir and storage capacity | Monthly | 2000 – 2023 | Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) |

| 6 | Evaporation | Monthly average | 2000 – 2023 | Royal Irrigation Department (RID) |

| 7 | Allocated water from downstream | Monthly average | 2000 – 2023 | Royal Irrigation Department (RID) |

| Scenarios | Periods/Years | Average | Range of 3 GCMs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm) | BL diff. (%) | Min. (mm) |

Max. (mm) |

||

| Baseline (BL) | 2000 - 2023 | 1,188.4 | - | - | - |

| SSP245 | 2024 - 2055 | 1,336.8 | 12.5 | 1,189.3 | 1,482.2 |

| SSP585 | 2024 - 2055 | 1,347.6 | 13.4 | 1,144.5 | 1,567.5 |

| Scenarios | Periods/Years | Average | Range of 3 GCMs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | BL diff. (°C) | Min. (°C) |

Max. (°C) |

||

| Baseline (BL) | 2000 - 2023 | 27.7 | - | - | - |

| SSP245 | 2024 - 2055 | 28.7 | 1.0 | 28.0 | 29.4 |

| SSP585 | 2024 - 2055 | 28.9 | 1.1 | 28.1 | 29.1 |

| Performance Rating | R2 | NSE | RSR | PBIAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | 0.75<R2≤1.00 | 0.75<NSE≤1.00 | 0.00<RSR≤0.50 | PBIAS<±10 |

| Good | 0.65< R2≤0.75 | 0.65<NSE≤0.75 | 0.50<RSR≤0.60 | ±10≤ PBIAS<±15 |

| Satisfactory | 0.50< R2≤0.65 | 0.50<NSE≤0.65 | 0.60<RSR≤0.70 | ±15≤ PBIAS<±25 |

| Unsatisfactory | R2≤0.50 | NSE≤0.50 | RSR>0.70 | PBIAS≥±25 |

| No. | Parameters | Land use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Forest | Urban | Shrubland | Wetland | Water | ||

| 1 | Crop coefficient (Kc) | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| 2 | Soil water capacity (SWC, mm) | 500.0 | 1000.0 | 50.0 | 300.0 | 700.0 | 600.0 |

| 3 | Deep water capacity (DWC, mm) | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 | 1,000.0 |

| 4 | Runoff resistance factor (RRF) | 2.0 | 0.2 | 4.0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| 5 | Root zone conductivity (RZC, mm/month) | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| 6 | Deep conductivity (DC, mm/month) | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| 7 | Preferred flow direction (PFD) | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Items | Modeling stage | Evaluation statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | NSE | RSR | PBIAS | ||

| Inflow | Calibration (2000-2011) | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.40 | -13.68 |

| Validation (2012-2023) | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.46 | 4.41 | |

| Overall (2000-2023) | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.43 | -5.20 | |

| Storage volume | Calibration (2000-2011) | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.69 | -6.77 |

| Validation (2012-2023) | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.49 | 5.74 | |

| Overall (2000-2023) | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.58 | -0.66 | |

| Month | Baseline (2000-2023) |

Future (2024-2055) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCESS-CM2 | MIROC6 | MPI-ESM1-2-LR | Average of 3 model | ||||||

| SSP245 | SSP585 | SSP245 | SSP585 | SSP245 | SSP585 | SSP245 | SSP585 | ||

| Jan | 14.7 | 38.6 | 41.7 | 32.7 | 40.1 | 39.7 | 36.8 | 37.0 | 39.5 |

| Feb | 14.2 | 39.9 | 42.6 | 49.3 | 49.0 | 43.2 | 58.9 | 44.1 | 50.2 |

| Mar | 27.2 | 58.3 | 71.9 | 52.7 | 65.6 | 49.1 | 66.9 | 53.3 | 68.1 |

| Apr | 50.3 | 93.2 | 129.9 | 102.6 | 118.6 | 94.4 | 126.7 | 96.7 | 125.0 |

| May | 135.5 | 236.3 | 292.2 | 286.1 | 327.7 | 269.8 | 260.7 | 264.1 | 293.6 |

| Jun | 157.3 | 338.1 | 342.3 | 408.7 | 462.4 | 317.7 | 332.5 | 354.8 | 379.0 |

| Jul | 221.9 | 444.4 | 346.9 | 538.0 | 625.9 | 440.4 | 444.0 | 474.3 | 472.2 |

| Aug | 421.1 | 676.5 | 567.6 | 822.7 | 775.9 | 636.0 | 720.6 | 711.7 | 688.1 |

| Sep | 851.5 | 987.2 | 990.9 | 879.1 | 919.4 | 1018.9 | 944.8 | 961.7 | 951.7 |

| Oct | 709.0 | 410.7 | 420.2 | 454.9 | 396.8 | 482.5 | 454.2 | 449.4 | 423.7 |

| Nov | 179.6 | 49.8 | 50.7 | 70.4 | 49.1 | 80.7 | 90.1 | 67.0 | 63.3 |

| Dec | 28.6 | 28.6 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 29.4 | 29.0 | 28.9 | 29.0 | 29.2 |

| Annual | 2,811.0 | 3,401.5 | 3,326.3 | 3,726.7 | 3,860.0 | 3,501.2 | 3,565.1 | 3,543.1 | 3,583.8 |

| Baseline difference | +21.0% | +18.3% | +32.6% | +37.3% | 24.5% | 26.8% | 26.9% | 27.5% | |

| Testing scenarios | Historic inflow |

SSP245 inflow |

SSP585 inflow |

Best RRRC | HO vs. HBMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water shortage | |||||

| Frequency (times per year) | 0.786 ⟶ 0.429 (45%) | 0.645 ⟶ 0.032 (95%) | 0.645 ⟶ 0.065 (90%) | RC2, RC5, RC7 | HO ≤ HBMO Lower |

| Average shortage (MCM) | 242.55 ⟶ 122.29 (50%) | 96.39 ⟶ 4.00 (96%) | 89.26 ⟶ 1.74 (98%) | RC1, RC2, RC5 | HO ≤ HBMO Lower |

| Maximum shortage (MCM) | 942 ⟶ 810 (14%) | 549 ⟶ 13 (98%) |

343 ⟶ 54 (84%) |

RC5, RC6 | HO ≈ HBMO Range |

| Average duration (year) | 5.5 ⟶ 2.2 (60%) |

3.3 ⟶ 1.0 (70%) |

4.0 ⟶ 1.0 (75%) |

RC5, RC7 | HO ≤ HBMO Lower |

| Maximum duration (year) | 14 ⟶ 3 (79%) |

6 ⟶ 1 (83%) |

8 ⟶ 1 (88%) |

RC5, RC7 | HO ≤ HBMO Lower |

| Excess water | |||||

| Frequency (times per year) | 0.929 ⟶ 0.857 (8%) | 1.0 ⟶ 1.0 (0%) |

1.0 ⟶ 1.0 (0%) |

RC1, RC4 | HO ≈ HBMO |

| Average shortage (MCM) | 1,346 ⟶ 1,200 (11%) | 2,103 ⟶ 1,958 (7%) | 1,992 ⟶ 1,829 (8%) | RC1, RC3, RC5 | HO ≤ HBMO Lower |

| Maximum shortage (MCM) | 4,139 ⟶ 4,100 (1%) | 3,652 ⟶ 3,340 (9%) | 4,222 ⟶ 3,872 (8%) | RC1, RC5 | HO ≈ HBMO Range |

| Average duration (year) | 10.4 ⟶ 6.0 (42%) | 31 ⟶ 31 (0%) |

31 ⟶ 31 (0%) |

RC1, RC4 | HO ≈ HBMO |

| Maximum duration (year) | 21 ⟶ 11 (48%) |

31 ⟶ 31 (0%) |

31 ⟶ 31 (0%) |

RC4 | HO ≈ HBMO |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).