1. Introduction

This section establishes the operational context for tactical edge security. Key concepts include the challenges of Disconnected, Intermittent, and Low-bandwidth (DIL) conditions, the gap between enterprise security frameworks and tactical reality, and the contributions this paper makes toward addressing that gap.

1.1. The Tactical Edge Challenge

Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) depends on secure sensor-to-shooter chains spanning air, land, sea, space, and cyber domains [

1]. Near-peer adversaries contest the electromagnetic spectrum through jamming, spoofing, and signals intelligence, creating environments where connectivity cannot be assured [

2]. The Ukraine conflict demonstrates that tactical units must operate for extended periods without reliable reach-back to enterprise infrastructure [

3]. These Disconnected, Intermittent, and Low-bandwidth (DIL) conditions represent the operational norm for tactical sensor networks, not an exception.

Security failures at the tactical edge carry kinetic consequences: compromised sensor data causes flawed situational awareness; manipulated AI targeting recommendations can result in fratricide; authentication failures enable adversary network exploitation. The DoD Zero Trust Strategy [

4] establishes the FY2027 target for all DoD information systems to achieve Target Level Zero Trust, aligning with OMB M-22-09’s federal zero trust architecture requirements [

25], with DTM 25-003 [

5] providing execution governance. Yet no framework addresses how continuous verification functions when the verification infrastructure is unreachable.

1.2. The Next-Generation Security Triad and DIL Gap

The Next-Generation Security Triad integrates three pillars: PQC, ensuring quantum-resistant cryptography; ZTA, eliminating implicit trust; and AI security protecting against adversarial manipulation. Prior work established the enterprise substrate architecture (CSI, IAMF, TAP, POE) and governance mechanisms, including behavioral envelopes, watchdog models, and consensus-backed approval [

6]. These mechanisms are architecturally sound but embed connectivity assumptions that fail at the tactical edge.

Table 1 summarizes the disconnect between enterprise assumptions and DIL reality.

1.3. Contributions

This paper makes four contributions: (1) a DIL-specific threat model identifying attack vector amplification; (2) the Tactical Edge Triad Architecture (TETA), adapting enterprise substrate components; (3) the Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF), systematically adapting governance mechanisms for disconnected operations; and (4) analytical evaluation with quantitative analysis across representative tactical scenarios.

Differentiation from Existing Guidance. TETA addresses gaps not covered by existing frameworks:

(a) Standard ZTA guidance (SP 800-207, DoD Zero Trust Strategy): Assumes Policy Decision Points (PDPs) and Policy Enforcement Points (PEPs) have continuous or degraded connectivity to identity providers and policy engines. TETA contributes pre-positioned policy with Authority Decay—credentials that degrade predictably without backend verification, with formal attack mitigations for clock rollback, credential replay, and peer collusion not addressed in SP 800-207.

(b)

Generic PQC migration guidance (CNSA 2.0, NIST IR 8547): Addresses algorithm selection and transition timelines but not DIL-specific constraints. TETA contributes platform-specific algorithm profiles balancing stateless resilience against bandwidth constraints (

Section 2.3.1), two-tier authentication separating routine MACs from evidentiary PQC signatures, and pre-positioned key material strategies for extended disconnection.

(c) Generic AI governance guidance (NIST AI RMF, AI 100-2e2025): Provides risk management frameworks assuming cloud connectivity for monitoring, logging, and human oversight. TETA contributes the Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF) with locally-enforced behavioral envelopes, an autonomous watchdog with self-triggered degradation, pre-mission consensus packaging satisfying DoDD 3000.09 human oversight requirements, and store-forward-reconcile for post-mission accountability.

(d) Triad integration: Existing frameworks address PQC, ZTA, and AI security in isolation. TETA demonstrates cross-pillar dependencies—using PQC to sign AI governance policies, binding credential decay to behavioral envelope constraints, and ensuring quantum-resistant protection for governance audit trails.

2. Background and Related Work

This section provides foundational context for the Tactical Edge Triad Architecture. Key concepts include tactical edge sensor network characteristics, the Next-Generation Security Triad foundations (PQC, ZTA, AI security), PQC implementation challenges in constrained environments, and governance mechanisms requiring DIL adaptation. The architecture aligns with NIST cyber-resiliency principles [

39], which emphasize anticipating, withstanding, recovering from, and adapting to adverse conditions—particularly relevant for DIL environments where degraded operation is expected rather than exceptional.

2.1. Tactical Edge Sensor Networks

Tactical sensor networks commonly include unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs/UAS), unattended ground sensors (UGS), unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), and software-defined radios (SDRs). These platforms share characteristics of cyber-physical systems operating in contested environments [

7], with security requirements amplified by DIL conditions. DoD’s JADC2 strategy emphasizes connecting distributed sensors across domains through resilient networks [

1].

Table 2 contrasts enterprise and tactical characteristics.

Current approaches rely on Type 1 encryption and High Assurance Internet Protocol Encryptor (HAIPE) devices, which provide NSA-certified IPsec-based protection for classified networks [

40]. HAIPE is defined in CNSSI 4009 as a device providing traffic protection, networking, and management features for information assurance services in IPv4/IPv6 networks. While HAIPE addresses point-to-point encryption, current tactical cryptographic approaches lack unified Triad protection or AI governance for disconnected autonomous operations [

8].

2.2. Next-Generation Security Triad Foundations

The Triad integrates PQC (FIPS 203 ML-KEM, FIPS 204 ML-DSA, FIPS 205 SLH-DSA) [

9,

10,

11], ZTA (SP 800-207, DoD Zero Trust Strategy) [

4,

12], and AI security (NIST AI 100-2e2025, AI RMF 1.0) [

13,

14]. The enterprise substrate enables integration through CSI (cryptographic services), IAMF (identity management), TAP (telemetry analytics), and POE (policy orchestration). Federal AI governance policy shifted in January 2025: EO 14110 was revoked by EO 14148 (January 20, 2025) [

44], and subsequent policy direction under EO 14179 [

24] and OMB M-25-21 [

45] emphasizes reduced barriers to AI development while maintaining risk management requirements. NIST technical frameworks (AI RMF, AI 100-2e2025) remain authoritative for federal AI risk management.

2.3. PQC and ZTA in Constrained Environments

PQC introduces overhead: ML-KEM public keys range from 800 bytes (ML-KEM-512) to 1,568 bytes (ML-KEM-1024) versus 32–64 bytes for ECDH; ML-DSA signatures range from 2,420 bytes (ML-DSA-44) to 4,595 bytes (ML-DSA-87) versus 64 bytes for ECDSA [

9,

10]. These values represent fixed-size encodings per FIPS 203/204 parameter tables; tactical implementations select parameter sets based on mission security requirements and platform constraints. NIST’s PQC transition guidance [

27] and KEM recommendations [

28] inform migration strategies.

Table 3 summarizes CNSA 2.0 transition timelines.

2.3.1. CNSA 2.0 vs. Expeditionary Edge Algorithm Selection

CNSA 2.0 [

8] establishes algorithm requirements for National Security Systems (NSS), but tactical edge deployments span a broader operational context that includes coalition partners, expeditionary forces, and mission-specific equipment outside traditional NSS boundaries. This subsection clarifies the distinction and justifies TETA’s algorithm selections.

NSS/CNSA 2.0 Requirements. For systems processing classified national security information, CNSA 2.0 mandates specific algorithm choices. Notably, for software and firmware signing, CNSA 2.0 specifies stateful hash-based signatures per SP 800-208 [

43]—specifically LMS (Leighton-Micali Signature) and XMSS (eXtended Merkle Signature Scheme). These stateful algorithms offer smaller signatures than SLH-DSA but require rigorous state management: each signing key can only be used a finite number of times, and state must never be rewound or duplicated. For NSS firmware signing in enterprise environments with a reliable key management infrastructure, SP 800-208 algorithms are appropriate and mandated.

Expeditionary Edge Constraints. Tactical edge platforms present distinct challenges that complicate SP 800-208 compliance:

(1) State management risk: Stateful signatures require tracking which one-time keys have been used. In DIL environments with potential device capture, power loss, or firmware corruption, state corruption could permanently disable signing capability. A ground sensor that loses state tracking cannot safely sign additional reports without risking key reuse—a cryptographic failure mode.

(2) Coalition interoperability: Mission partners may operate under different national cryptographic policies. FIPS 203/204/205 algorithms provide a common baseline with broader international toolchain availability than SP 800-208 implementations, which remain less mature in embedded environments.

(3) Procurement and toolchain realities: Commercial embedded platforms increasingly support ML-DSA and SLH-DSA through standard cryptographic libraries (e.g., liboqs, wolfSSL PQC). SP 800-208 implementations for constrained devices remain limited, with state synchronization adding integration complexity.

TETA Algorithm Justification.Table 8’s algorithm selections reflect these constraints:

ML-DSA-65/87 (FIPS 204): Primary signature algorithm for platforms with sufficient bandwidth. Stateless operation eliminates state management risk. Selected for UAV and vehicle platforms.

SLH-DSA-128s (FIPS 205): Selected for ground sensors using a two-tier authentication model. Routine reports use symmetric MACs; high-confidence detections requiring evidentiary chain-of-custody use SLH-DSA signatures. While SLH-DSA-128s signatures (7,856 bytes) impose bandwidth penalties, ground sensors sign infrequently (typically 2–4 high-value detections daily), making this overhead acceptable. Stateless design eliminates state management vulnerabilities critical for unattended sensors, where power loss or tampering could corrupt the signing state.

FN-DSA (draft FIPS 206): Selected for maritime SATCOM where both bandwidth efficiency and stateless operation are required. Compact 666-byte signatures without state management overhead. Implementation Note: FN-DSA’s bandwidth efficiency comes with implementation complexity. The algorithm requires high-precision floating-point arithmetic for FFT-based Gaussian sampling, which (1) complicates constant-time implementation on platforms without hardware floating-point units, and (2) introduces side-channel vulnerabilities that require careful mitigation on Cortex-M4 class devices. Reference implementations typically require ~30 KB code footprint and show 2–3× slower signing than ML-DSA on integer-only microcontrollers. Maritime platforms with Cortex-A53 or higher are better suited for FN-DSA deployment; ground sensors should prefer ML-DSA-65 unless bandwidth constraints are critical.

SP 800-208 Applicability. For specific use cases within TETA—particularly pre-mission firmware signing conducted in enterprise environments with proper key management—SP 800-208 algorithms (LMS/XMSS) remain appropriate. Governance packages and firmware images signed at mission preparation can use LMS with centralized state tracking. However, for runtime signatures generated by deployed tactical platforms, stateless algorithms (ML-DSA, SLH-DSA, FN-DSA) provide resilience against the state corruption risks inherent to DIL operations. This distinction aligns with NSA guidance that algorithm selection should consider “the specific use case and operational environment” [

8], recognizing that tactical edge deployments may require different tradeoffs than enterprise NSS implementations.

Zero Trust for OT guidance acknowledges real-time constraints but assumes degraded rather than absent connectivity [

15]. No framework addresses fully disconnected ZTA operations.

2.4. Governance and Behavioral Security Foundations

Prior work established governance mechanisms for autonomous systems.

Table 4 summarizes these mechanisms and their connectivity assumptions requiring DIL adaptation.

These mechanisms require adaptation for DIL where consensus nodes are unreachable, human authorities are unavailable, and real-time reporting is impossible. The key insight is that governance intent can be preserved while adapting implementation—consensus can occur before deployment, approval can be pre-authorized, and accountability can be maintained through post-mission reconciliation.

3. DIL Threat Model

This section characterizes the threat environment specific to tactical operations. Key concepts include DIL severity levels, attack vector amplification under disconnection, and integrated Triad responses to DIL-specific threats.

3.1. Threat Environment Characterization

Tactical sensor networks operate under contested spectrum (jamming, spoofing, SIGINT), nation-state adversary capabilities (quantum computing, adversarial ML), physical capture risk, and extended disconnection [

21]. Recent Army initiatives identify 58 distinct zero-trust capabilities required for tactical edge implementation [

29], underscoring the complexity of DIL security requirements.

Table 5 characterizes DIL severity levels.

3.2. DIL-Amplified Attack Vectors

DIL conditions amplify traditional threats.

Table 6 summarizes attack amplification and Triad responses.

Cross-domain scenarios include quantum-enabled SIGINT combining HNDL with future cryptanalysis, edge AI manipulation during disconnection, combining adversarial inputs with governance bypass, and supply chain compromise of pre-positioned models with extended exploitation windows.

4. Tactical Edge Triad Architecture (TETA)

This section presents the core architectural contribution. Key concepts include disconnected-first design principles, the five TETA substrate components (ECM, TIC, EAE, MPS, AAGF), and the Autonomous AI Governance Framework that enables accountable AI operations without connectivity.

4.1. Design Principles and Substrate Overview

TETA is grounded in five principles: (1) disconnected-first design, assuming no connectivity; (2) graceful degradation with predictable security property curves; (3) pre-positioned trust enabling deployment before mission; (4) autonomous security decisions without external dependencies; (5) cryptographic sustainability managing key lifecycle across disconnection.

Table 7 maps enterprise substrate layers to TETA components.

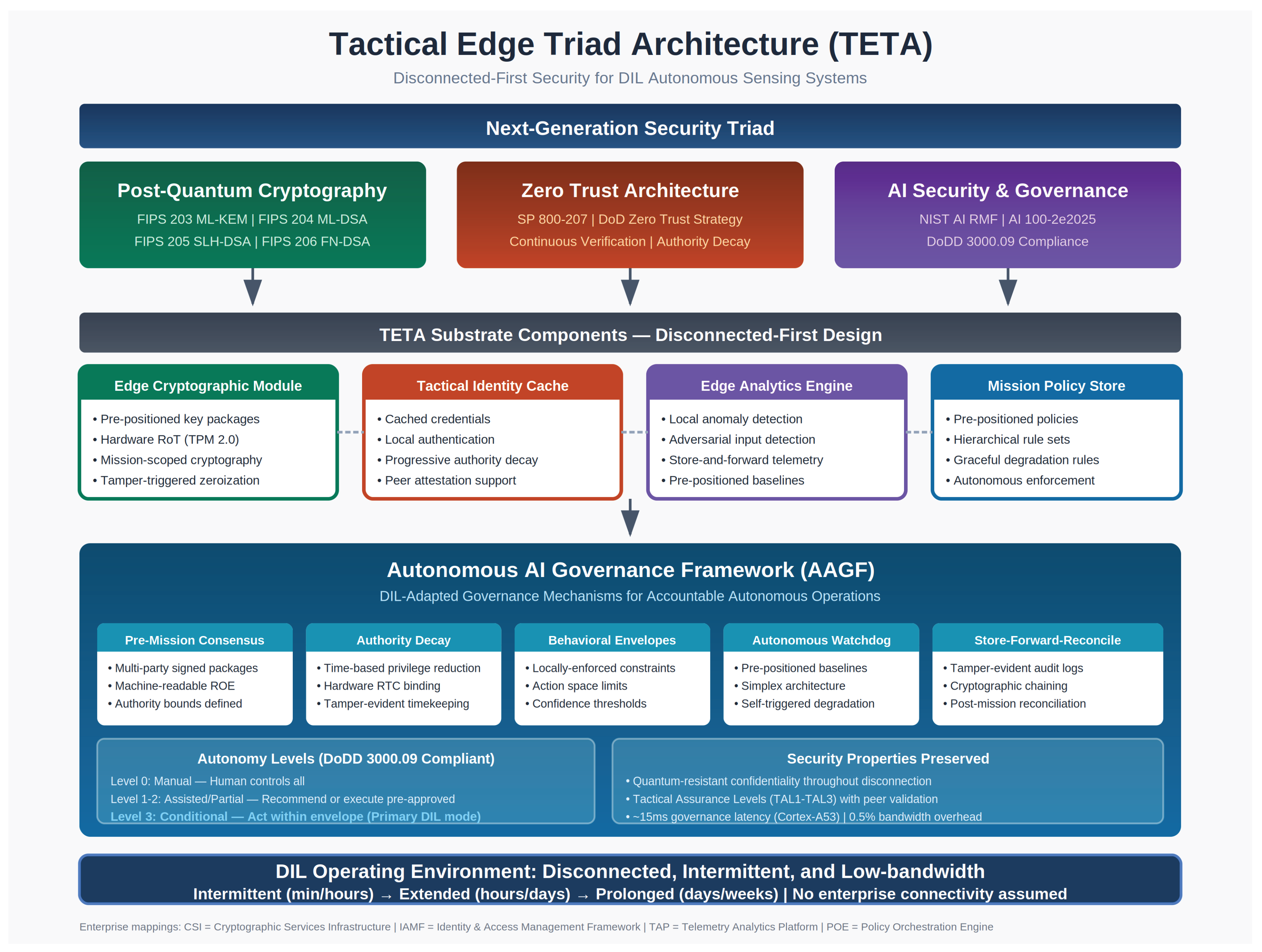

Figure 1 illustrates the complete TETA architecture, showing the relationship between the Next-Generation Security Triad pillars, the four substrate components adapted from enterprise frameworks, and the Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF) with its five governance mechanisms.

4.2. Substrate Components

Table 8 summarizes PQC algorithm selection by platform constraint profile.

Table 8 presents baseline algorithm selections by platform type; actual mission profiles may adjust selections based on available link capacity. For example, a ground sensor with 9.6 kbps HF radio may use ML-DSA-65 (3,309-byte signatures) rather than the SLH-DSA-128s baseline (7,856 bytes), reserving SLH-DSA for worst-case bps opportunistic links where stateless resilience is paramount.

The Edge Cryptographic Module (ECM) provides mission-scoped key packages with hardware security integration via TPM 2.0. The Tactical Identity Cache (TIC) manages credentials with progressive authority decay. The Edge Analytics Engine (EAE) implements local anomaly detection, store-and-forward telemetry, and adversarial input detection. The Mission Policy Store (MPS) contains hierarchical pre-positioned policies with graceful degradation rules.

The ground sensor selection of SLH-DSA-128s warrants clarification regarding bandwidth constraints. SLH-DSA signatures (7,856 bytes for SLH-DSA-128s per FIPS 205) impose severe penalties on bps opportunistic links. Ground sensors employ a two-tier authentication model: (1) routine status reports and low-confidence detections use symmetric MACs derived from ML-KEM session keys—compact (32 bytes) and computationally inexpensive; (2) high-confidence detections requiring evidentiary chain-of-custody use PQC signatures for non-repudiation. This tiered approach reserves expensive PQC signing for reports that may support targeting decisions or post-mission review, while routine telemetry uses efficient symmetric authentication. Governance packages and firmware updates are signed at mission preparation using enterprise infrastructure; the sensor verifies these signatures locally. For scenarios requiring frequent sensor-originated signatures, FN-DSA (based on FALCON, draft FIPS 206 [

17]) offers bandwidth-efficient alternatives. FN-DSA is an NTRU-lattice-based signature scheme using FFT-based sampling, with padded fixed-length encoding yielding compact 666-byte signatures for the FN-DSA-512 parameter set [

22]. However, FN-DSA presents implementation challenges on constrained platforms: the Gaussian sampling procedure requires high-precision floating-point arithmetic, complicating deployment on integer-only Cortex-M4 devices and introducing timing side-channel risks that require constant-time countermeasures. Platforms deploying FN-DSA should validate side-channel resistance through power analysis testing before operational use.

Algorithm selections in

Table 8 prioritize stateless operation for tactical resilience. For mission preparation activities conducted in enterprise environments (governance package signing, firmware updates), SP 800-208 stateful algorithms (LMS/XMSS) provide an alternative with reduced signature sizes where proper state management infrastructure exists [

43]. See

Section 2.3.1 for detailed CNSA 2.0 alignment discussion.

4.3. Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF)

The AAGF addresses the tension that AI must make consequential decisions when disconnected, yet autonomous AI without governance poses unacceptable risk.

Table 9 summarizes governance mechanism adaptations.

4.3.1. Pre-Mission Consensus and Pre-Authorized Envelopes

Consensus occurs before deployment through multi-party signed governance packages. Required signatories (command, legal, safety) cryptographically sign packages defining authority bounds, machine-readable ROE, envelope parameters, and degradation rules. Pre-authorized decision envelopes establish action spaces with authority obtained in advance.

Relationship to Bounded Autonomy and Run-Time Assurance. Pre-Mission Consensus Packaging implements concepts from the broader bounded autonomy and Run-Time Assurance (RTA) literature. ASTM F3269-17 [

46] establishes principles for run-time assurance in autonomous systems, requiring that safety monitors can override potentially unsafe commands from complex decision-making components. TETA’s behavioral envelopes serve an analogous function: pre-computed bounds verified at runtime that constrain AI decision outputs regardless of the reasoning that produced them. The key adaptation for DIL environments is that RTA typically assumes connectivity to ground-based safety monitors; Pre-Mission Consensus pre-positions these constraints cryptographically, enabling local enforcement without external verification.

Authority decay progressively reduces permissions over disconnection time. This mechanism represents a DIL-specific operationalization of Risk-Adaptive Access Control (RAdAC) [

34,

35], which balances security risk against operational need through dynamic policy evaluation. Authority Decay extends RAdAC principles to disconnected environments where real-time risk assessment infrastructure is unavailable, instead using time-since-verification as a proxy for accumulated risk. Policy expression follows NIST ABAC guidance [

31], with subject attributes (role, clearance, mission assignment), object attributes (classification, consequence category), and environmental attributes (time-since-verification, peer attestation count) evaluated against pre-positioned rules.

Authority Decay also draws from capability-based authorization patterns. Like Macaroons [

33], which embed contextual caveats that attenuate bearer credentials, governance envelopes contain cryptographically-bound constraints that progressively restrict authority. Unlike enterprise systems like Google’s Zanzibar [

32] that require backend connectivity for authorization decisions, Authority Decay pre-computes authorization policies and embeds decay schedules directly in credentials, enabling offline enforcement.

Formal Model. Let

t represent elapsed time since last successful verification (connectivity epoch), and let

denote the authority level function. Authority Decay implements a piecewise monotonically decreasing function:

where

h,

h,

h represent threshold boundaries (configurable per mission profile). Each authority level

corresponds to a subset of permitted actions, with

.

Table 10 defines representative permission sets.

Attack Model and Mitigations. Authority Decay faces specific attack vectors in adversarial DIL environments.

Table 11 characterizes threats and countermeasures.

Clock integrity represents the primary vulnerability. Implementations should bind authority evaluation to tamper-evident time sources: TPM-protected monotonic counters provide rollback resistance; hardware RTC with battery-backed tamper detection prevents physical manipulation; peer time attestation (where available) provides cross-validation. Credential structures should include epoch counters that increment at each authority transition, preventing replay of higher-authority credentials after decay.

Assurance Boundary. Authority Decay’s security guarantees depend on a hardware root-of-trust providing protected monotonic counters and tamper-evident timekeeping. Specifically, the mechanism assumes: (1) a TPM, secure element, or TEE that maintains monotonic counters resistant to software manipulation; (2) hardware RTC with tamper detection that signals physical interference; and (3) secure storage for decay schedule parameters that cannot be modified post-deployment. Without these hardware foundations, Authority Decay can be bypassed by a physical attacker with device access—clock rollback or counter reset would restore expired authority levels. Platforms lacking a hardware root-of-trust should not rely on Authority Decay for security-critical decisions; such platforms should instead default to minimal pre-authorized authority with mandatory human approval for consequential actions.

RTC Failure Mode. A critical edge case occurs when RTC battery failure or corruption causes the system clock to reset to epoch (e.g., January 1, 1970). Implementations MUST detect this condition—typically via comparison against the pre-mission timestamp embedded in the governance envelope—and default to Safe Mode (Level 0 / Zero Authority), not Full Authority. The function should treat any clock value preceding the mission start timestamp as a tamper indicator. Safe Mode behavior: (1) cease autonomous operations; (2) revert to manual-only control if available; (3) activate tamper alert beacon if mission profile permits; (4) await physical recovery or re-initialization.

Table 12 shows the authority delegation matrix mapping decision categories to required authority levels and DIL authorization mechanisms.

Scope Limitations. Pre-Mission Consensus Packaging provides technical mechanisms supporting documented oversight requirements but does not address several governance challenges that require human judgment, legal interpretation, or policy decisions beyond the scope of this architecture: (1) ROE interpretation—translating rules of engagement into machine-readable constraints requires legal and operational judgment that cannot be automated; (2) commander intent capture—encoding nuanced tactical intent into envelope parameters may incompletely represent command guidance; (3) coalition legal constraints—multinational operations involve varying legal frameworks that pre-positioned packages cannot fully reconcile; (4) novel situation adjudication—scenarios outside envelope parameters default to conservative responses, but determining appropriate responses to truly novel situations requires human judgment.

4.3.2. Locally-Enforced Behavioral Bounds

Behavioral envelopes are enforced locally without cloud dependency.

Table 13 defines envelope dimensions.

The Behavioral Envelope Enforcer operates as a separate hardened component that the AI cannot bypass—analogous to hardware interlocks. Every action passes through the enforcer; violations are blocked, logged, and trigger watchdog alerts.

Effective enforcement benefits from hardware or software isolation, preventing the monitored AI model from compromising the governance module. Implementation options include separate security processors (e.g., ARM TrustZone secure world), dedicated microcontrollers for governance functions, or hypervisor-enforced isolation.

4.3.3. Autonomous Watchdog and Self-Triggered Degradation

Watchdog models use pre-positioned baselines with autonomous response, implementing runtime assurance principles from the Simplex architecture [

36]. The Simplex approach provides safety guarantees by switching control from an unverified advanced controller to a verified-safe baseline controller when safety violations are imminent. Recent extensions demonstrate applicability to neural network controllers [

37] and multi-agent systems [

38], directly relevant to AI-enabled tactical platforms. In TETA, the watchdog serves as the decision module, triggering autonomy-downgrade (analogous to baseline controller activation) when behavioral anomalies or constraint violations are detected.

Table 14 defines watchdog types.

Self-triggered autonomy degradation uses predefined triggers.

Table 15 defines autonomy levels.

Level 5 represents an analytic boundary in this autonomy model; DoDD 3000.09 requires that “autonomous and semi-autonomous weapon systems shall be designed to allow commanders and operators to exercise appropriate levels of human judgment over the use of force” [

16]. This directive further mandates that such systems be “sufficiently robust to minimize failures that could lead to unintended engagements.” Maximum DIL authority is Level 3 with envelope enforcement, designed to support these human oversight requirements.

4.3.4. Store-Forward-Reconcile and Conservative Bias

Local audits capture every decision, governance evaluation, watchdog alert, and override. Tamper-evident storage uses cryptographic chaining. Store-forward-reconcile operations align with Delay-Tolerant Networking principles [

26], with Bundle Protocol Security (BPSec) [

30] providing data integrity and confidentiality services for store-and-forward transmission. BPSec’s block-level security model supports security-at-rest, addressing HNDL concerns for queued audit data. Mandatory reconciliation upon reconnection uploads audits, reviews deviations, verifies model integrity, and refreshes authorities.

5. Case Study Scenarios

This section demonstrates TETA-AAGF feasibility through representative tactical scenarios. Key concepts include scenario selection spanning the DIL spectrum, airborne ISR platform collective governance, and ground sensor operations under extended disconnection.

The evaluation methodology employs analytical modeling rather than empirical measurement, with sources explicitly distinguished. PQC cryptographic operation timings derive from published pqm4 benchmark data [

18,

19], representing baseline performance on Cortex-M4 microcontrollers. Governance function estimates (envelope checking, watchdog inference, autonomy evaluation, audit logging) are engineering projections based on comparable embedded workloads, lightweight neural network inference, policy engine evaluation, and cryptographic logging—and should be treated as order-of-magnitude estimates requiring validation.

5.1. Scenario Selection

Two scenarios span the DIL spectrum: airborne ISR (intermittent connectivity, collective governance) and ground sensors (extended disconnection, minimal compute).

Table 16 compares scenario characteristics.

5.2. Scenario 1: Airborne ISR Platform (UAV Swarm)

A 4-8 UAV swarm conducts persistent surveillance with burst connectivity (minutes/hour) over 256 kbps tactical datalink. TETA employs ML-KEM-768/ML-DSA-65 with hardware-bound identity. AAGF establishes collective governance requiring a quorum for formation decisions, a peer-based watchdog, and autonomous navigation/classification within an envelope while prohibiting autonomous engagement.

5.3. Scenario 2: Dismounted Ground Sensors

Unattended sensors deploy for 30 days with bits per second opportunistic bandwidth. TETA employs SLH-DSA-128s (compact keys) with tamper-triggered zeroization. AAGF permits detection/reporting only (Level 2 maximum), self-diagnostic watchdog, and automatic shutdown at mission window expiration.

5.4. Evaluation Targets

Table 17 summarizes evaluation targets by scenario.

Key finding: Governance complexity scales with decision consequence, not platform sophistication.

6. Quantitative Analysis

This section provides an analytical assessment of TETA-AAGF overhead and effectiveness. All values represent engineering estimates derived from published benchmarks and protocol specifications—not empirical measurements from implemented prototypes.

6.1. Quantitative Model Methodology

Table 18 summarizes all model parameters, their values, sources, and whether each represents measured data or an engineering estimate.

Timing Conversion Note: pqm4 benchmarks report cycle counts, not wall-clock time. Under conservative assumptions (168 MHz, flash wait state penalty), representative timings are: ML-KEM-768 encaps ~15–25 ms, ML-DSA-65 sign ~40–70 ms, ML-DSA-65 verify ~15–25 ms. These estimates carry ±50% uncertainty.

6.2. Computational Overhead

Table 19 presents computational overhead on representative platforms.

6.3. Bandwidth, Storage, and Power

Table 20 summarizes resource requirements.

6.4. Security Property Preservation

Table 21 shows authentication assurance degradation over disconnection using Tactical Assurance Levels (TAL1–TAL3). These levels are inspired by but not equivalent to NIST SP 800-63B Authenticator Assurance Levels (AAL) [

23].

6.5. Worked Example: Tactical Sensor Report

Table 22 presents the byte-level breakdown comparing legacy versus TETA message formats.

Overhead Assessment. The 27.9× message size increase is dominated by the ML-DSA-65 signature (98% of overhead). This overhead applies only to high-confidence detections; routine reports use MAC authentication with negligible overhead (91 bytes total).

7. Discussion and Conclusion

7.1. Contributions and Significance

This paper demonstrates that the Next-Generation Security Triad can be implemented in DIL tactical environments through systematic adaptation of governance mechanisms. TETA provides disconnected-first substrate components; AAGF ensures AI systems operate within constraints with preserved accountability.

Three novel mechanisms distinguish this work: (1) Authority Decay—a DIL-specific operationalization of continuous verification; (2) Pre-Mission Consensus Packaging—cryptographically signed governance envelopes supporting DoD Directive 3000.09 requirements; and (3) Triad Integration—architectural unification demonstrating how PQC secures AI governance integrity.

7.2. Comparison with Existing Approaches

Table 23 compares TETA-AAGF with existing frameworks.

7.3. Limitations and Future Work

This work presents a conceptual architecture with analytical sizing rather than an implemented system. Performance estimates derive from published benchmarks applied to representative operational profiles; they have not been validated through instrumented prototypes.

Future work includes operational pilots with DoD units, hardware PQC acceleration, formal verification of governance properties, federated learning for distributed governance model updates, and coalition interoperability frameworks.

7.4. Conclusion

TETA adapts the Triad for DIL through disconnected-first substrate components. AAGF systematically translates governance mechanisms: consensus becomes pre-mission signed packages; approval becomes pre-authorized envelopes with authority decay; behavioral envelopes become locally-enforced hard constraints; watchdogs become autonomous with pre-positioned baselines; autonomy-downgrade becomes self-triggered degradation; observability becomes store-forward-reconcile.

Analytical evaluation demonstrates feasibility with acceptable estimated overhead. Combined governance latency is estimated at ~15 ms on Cortex-A53 class processors (range: 8–25 ms), with 0.5% steady-state bandwidth increase. TETA-AAGF enables Next-Generation Security Triad protection at the tactical edge—under fire, without connectivity—where it matters most.

Author Contributions

R.E.C. conceptualized the framework, conducted analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Department of Defense. Summary of the Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) Strategy; DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bronk, J.; Reynolds, N.; Watling, J. The Russian Air War and Ukrainian Requirements for Air Defence; RUSI: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Watling, J.; Reynolds, N. Ukraine at War: Paving the Road from Survival to Victory; RUSI: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. DoD Zero Trust Strategy; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. DTM 25-003: Implementing the DoD Zero Trust Strategy; Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Campbell, R.E. Operationalizing the Next-Generation Security Triad: AI Security, PQC, and Zero Trust in Federal Compliance. Preprints 2025, 202512.2298.v1. [Google Scholar]

- Humayed, A.; Lin, J.; Li, K.; Luo, B. Cyber-Physical Systems Security—A Survey. IEEE IoT J. 2017, 4, 1802–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Security Agency. Announcing the Commercial National Security Algorithm Suite 2.0; NSA: Fort Meade, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; FIPS 203; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Digital Signature Standard; FIPS 204; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. Stateless Hash-Based Digital Signature Standard; FIPS 205; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, S.; Borchert, O.; Mitchell, S.; Connelly, S. Zero Trust Architecture; SP 800-207; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev, A.; Oprea, A.; Fordyce, A.; Anderson, H. Adversarial Machine Learning; AI 100-2e2025; NIST:

Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025.

- Tabassi, E. Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. Zero Trust for Operational Technology; DoD CIO: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense. DoD Directive 3000.09: Autonomy in Weapon Systems; DoD: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- NIST. FIPS 206: FN-DSA (Falcon); NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kannwischer, M.J.; Rijneveld, J.; Schwabe, P.; Stoffelen, K. pqm4: Testing and Benchmarking NIST PQC on ARM Cortex-M4. In Proceedings of the Second NIST PQC Standardization Conference; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kannwischer, M.J.; Krausz, M.; Petri, R.; Yang, S.-Y. pqm4: Benchmarking NIST Additional Post-Quantum Signature Schemes. IACR ePrint 2024, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, D.; Kannwischer, M.J.; Land, G.; et al. First-Order Masked Kyber on ARM Cortex-M4. IACR TCHES 2022, 479–505. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.S.; Johnsen, F.T. Cybersecurity in Tactical Edge Networks. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2025, 23, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prest, T.; Fouque, P.-A.; Hoffstein, J.; et al. FALCON: Fast-Fourier Lattice-based Compact Signatures over NTRU; NIST PQC Round 3 Submission. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Grassi, P.A.; Garcia, M.E.; Fenton, J.L. Digital Identity Guidelines; SP 800-63B; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The White House. Removing Barriers to American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence; Executive Order

14179;Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Office of Management and Budget. M-22-09: Moving the U.S. Government Toward Zero Trust; OMB: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burleigh, S.; Fall, K.; Birrane, E., III. Bundle Protocol Version 7; RFC 9171; IETF, 2022.

- Moody, D.; Perlner, R.; Regenscheid, A.; et al. Transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards. NIST IR 8547; NIST. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.; Ferraiolo, H.; Johnson, V.C.; et al. Recommendations for Key-Encapsulation Mechanisms; SP

800-227; NIST, 2025.

- Koontz, B. At the Tactical Edge, Army Wants 58 Zero Trust Capabilities. Federal News Network, 7 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Birrane, E., III; McKeever, K. Bundle Protocol Security (BPSec); RFC 9172; IETF, 2022.

- Hu, V.C.; Ferraiolo, D.; Kuhn, R.; et al. Guide to Attribute Based Access Control (ABAC); SP 800-162; NIST,

2014.

- Pang, R.; Caceres, R.; Burrows, M.; et al. Zanzibar: Google’s Consistent, Global Authorization System. In Proceedings of USENIX ATC, 2019; 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Birgisson, A.; Politz, J.G.; Erlingsson, Ú.; et al. Macaroons: Cookies with Contextual Caveats. In Proceedings of NDSS, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, R. Risk-Adaptable Access Control (RAdAC). In Proceedings of NIST Privilege Management Workshop, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kandala, S.; Sandhu, R.; Bhamidipati, V. An Attribute Based Framework for Risk-Adaptive Access Control Models. In Proceedings of ARES, 2011; 236–241. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, D.; Krogh, B.; Sha, L.; Chutinan, A. The Simplex Architecture for Safe Online Control System Upgrades. In Proceedings of ACC, 1998; 3504–3508. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, U.; Sheikhi, S.; Bak, S.; et al. The Black-Box Simplex Architecture for Runtime Assurance. In Proceedings of NFM, 2022; 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood, U.; Stoller, S.D.; Grosu, R.; et al. A Distributed Simplex Architecture for Multi-Agent Systems. In Proceedings of SETTA, 2021; 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, R.; Pillitteri, V.; Graubart, R.; et al. Developing Cyber-Resilient Systems; SP 800-160 Vol. 2 Rev. 1; NIST,

2021.

- Committee on National Security Systems. National Information Assurance (IA) Glossary; CNSSI No. 4009;

CNSS, 2015.

- Lin, J.; Chen, W.-M.; Lin, Y.; et al. MCUNet: Tiny Deep Learning on IoT Devices. In Proceedings of NeurIPS, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sudharsan, B.; Salerno, S.; Nguyen, D.-D.; et al. TinyML Benchmark. In Proceedings of IEEE WF-IoT, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Housley, R.; Regenscheid, A.; Celi, C. Recommendations for Stateful Hash-Based Signature Schemes; SP

800-208; NIST, 2020.

- The White House. Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders; Executive Order 14148; Washington, DC,

USA, 2025.

- Office of Management and Budget. M-25-21: Accelerating Federal Use of AI; OMB: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM International. F3269-17: Standard Practice for Methods to Safely Bound Flight Behavior of UAS. ASTM. 2017. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Tactical Edge Triad Architecture (TETA) top-level design. The architecture adapts the Next-Generation Security Triad (PQC, ZTA, AI Security) for DIL environments through four substrate components (ECM, TIC, EAE, MPS) and the Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF). The AAGF implements five mechanisms: Pre-Mission Consensus, Authority Decay, Behavioral Envelopes, Autonomous Watchdog, and Store-Forward-Reconcile. Maximum autonomy is Level 3 (Conditional) with envelope enforcement, supporting DoDD 3000.09 human oversight requirements.

Figure 1.

Tactical Edge Triad Architecture (TETA) top-level design. The architecture adapts the Next-Generation Security Triad (PQC, ZTA, AI Security) for DIL environments through four substrate components (ECM, TIC, EAE, MPS) and the Autonomous AI Governance Framework (AAGF). The AAGF implements five mechanisms: Pre-Mission Consensus, Authority Decay, Behavioral Envelopes, Autonomous Watchdog, and Store-Forward-Reconcile. Maximum autonomy is Level 3 (Conditional) with envelope enforcement, supporting DoDD 3000.09 human oversight requirements.

Table 1.

Enterprise Triad assumptions versus DIL operational reality.

Table 1.

Enterprise Triad assumptions versus DIL operational reality.

| Triad Element |

Enterprise Assumption |

DIL Reality |

| PQC |

Bandwidth for larger keys/signatures |

Constrained tactical links (kbps) |

| ZTA |

Continuous verification via enterprise IdP |

No connectivity for authentication |

| AI Security |

Cloud-based monitoring and governance |

No cloud access for validation |

| Governance |

Real-time multi-party consensus |

Single isolated platform |

| Observability |

Real-time SIEM integration |

No telemetry path; delayed visibility |

Table 2.

Operational characteristics: enterprise versus tactical edge.

Table 2.

Operational characteristics: enterprise versus tactical edge.

| Characteristic |

Enterprise |

Tactical Edge |

| Connectivity |

Always-on, high bandwidth |

DIL: hours to weeks disconnected |

| Power |

Unlimited (grid) |

Battery/solar constrained |

| Compute |

Cloud-scale resources |

Embedded/microcontroller class |

| Physical Security |

Data center controls |

Contested environment, capture risk |

| Failure Consequence |

Business disruption |

Mission failure, casualties |

Table 3.

CNSA 2.0 transition timeline by system type [

8].

Table 3.

CNSA 2.0 transition timeline by system type [

8].

| System Type |

Support/Prefer CNSA 2.0 |

Exclusive CNSA 2.0 |

| Software/firmware signing |

2025 |

2030 |

| Web browsers/servers, cloud services |

2025 |

2033 |

| Traditional networking equipment |

2026 |

2030 |

| Operating systems |

2027 |

2033 |

| Niche equipment (constrained devices, large PKI) |

2030 |

2033 |

| Custom applications, legacy equipment |

— |

2033 |

Table 4.

Governance mechanisms and connectivity assumptions.

Table 4.

Governance mechanisms and connectivity assumptions.

| Mechanism |

Function |

Connectivity Assumption |

| Behavioral envelopes |

Constrain actions |

Cloud monitoring validates compliance |

| Watchdog models |

Monitor anomalies |

Report to SOC for human review |

| Autonomy-downgrade |

Reduce AI authority |

Human/external triggers reduction |

| Consensus governance |

Multi-party approval |

Real-time consensus nodes reachable |

| Observability |

Detection/response |

Real-time telemetry to SIEM |

Table 5.

DIL severity characterization.

Table 5.

DIL severity characterization.

| DIL Level |

Disconnection |

Bandwidth |

Example Platform |

| Intermittent |

Minutes to hours |

kbps burst |

UAV swarm |

| Extended |

Hours to days |

Sporadic kbps |

Maritime patrol |

| Prolonged |

Days to weeks |

bps opportunistic |

Ground sensor |

Table 6.

DIL-amplified threats and integrated Triad responses.

Table 6.

DIL-amplified threats and integrated Triad responses.

| Attack Vector |

DIL Amplification |

Triad Response |

| HNDL collection |

Tactical traffic high-value intelligence |

PQC protection; short-lived session keys |

| Credential theft |

Extended validity; no real-time detection |

Time-bounded credentials; authority decay |

| Sensor spoofing |

No cloud correlation for detection |

Local anomaly detection; peer validation |

| AI manipulation |

No remote model validation |

Pre-positioned baselines; local watchdog |

| Model poisoning |

Compromised models undetected |

Pre-deployment validation; integrity checks |

| Physical capture |

Governance parameters exposed |

Platform-specific packages; tamper response |

Table 7.

Enterprise substrates to TETA component mapping.

Table 7.

Enterprise substrates to TETA component mapping.

| Enterprise |

TETA Component |

Key Adaptations |

| CSI |

Edge Cryptographic Module |

Pre-positioned keys; lightweight PQC; hardware RoT |

| IAMF |

Tactical Identity Cache |

Cached credentials; local auth; authority decay |

| TAP |

Edge Analytics Engine |

Local anomaly detection; store-and-forward |

| POE |

Mission Policy Store |

Pre-positioned policies; autonomous enforcement |

| (New) |

AI Governance Framework |

DIL-adapted governance mechanisms |

Table 8.

PQC algorithm selection by platform type (expeditionary edge profile; see

Section 2.3.1 for NSS/CNSA 2.0 considerations).

Table 8.

PQC algorithm selection by platform type (expeditionary edge profile; see

Section 2.3.1 for NSS/CNSA 2.0 considerations).

| Platform Type |

KEM |

Signature |

Rationale |

| UAV (moderate) |

ML-KEM-768 |

ML-DSA-65 |

Balanced security/perf |

| Ground sensor |

ML-KEM-512 |

SLH-DSA-128s |

Compact keys; PQC for high-value only |

| Maritime |

ML-KEM-512 |

FN-DSA (draft FIPS 206) |

Compact signatures for SATCOM |

| Vehicle (high) |

ML-KEM-1024 |

ML-DSA-87 |

Maximum security margin |

Table 9.

Governance mechanism adaptations for DIL operations.

Table 9.

Governance mechanism adaptations for DIL operations.

| Mechanism |

Enterprise Approach |

DIL Adaptation |

| Consensus |

Real-time multi-party agreement |

Pre-mission consensus via signed packages |

| Multi-party approval |

Approval authorities reachable |

Pre-authorized decision envelopes |

| Behavioral envelopes |

Cloud monitoring |

Locally-enforced hard constraints |

| Watchdog models |

Report to SOC |

Autonomous watchdog with local response |

| Autonomy-downgrade |

Human/external triggers |

Self-triggered degradation |

| Observability |

Real-time SIEM |

Store-forward-reconcile |

Table 10.

Authority decay schedule and permission sets.

Table 10.

Authority decay schedule and permission sets.

| Authority Level |

Time Window |

Permitted Actions |

Prohibited Actions |

|

0–24h |

All pre-authorized actions |

None within envelope |

|

24–48h |

Sensing, classification, reporting |

Engagement recommendations |

|

48–72h |

Passive sensing, status reporting |

Active classification, targeting |

|

>72h |

Self-preservation, beacon only |

All mission actions |

Table 11.

Authority Decay attack vectors and mitigations.

Table 11.

Authority Decay attack vectors and mitigations.

| Attack Vector |

Threat Description |

Mitigation |

| Clock rollback |

The adversary manipulates the local clock to restore expired authority |

Hardware RTC with tamper detection; monotonic counters in TPM; cross-check against peer clocks |

| Time manipulation |

Captured device clock advanced/rewound |

Signed timestamps from pre-mission epoch; GPS time when available; clock drift bounds |

| Credential replay |

Previously-valid credentials reused after refresh |

Nonce binding; epoch counters in credential structure; hash chain to last known state |

| Peer collusion |

Colluding peers falsely attest to continued validity |

Quorum requirements (k-of-n); behavioral anomaly detection; audit trail |

Table 12.

Authority delegation matrix for DIL operations.

Table 12.

Authority delegation matrix for DIL operations.

| Decision Category |

Authority Required |

DIL Authorization |

| Routine sensing |

Autonomous |

Fully pre-authorized |

| Target classification |

Supervised |

Pre-authorized within the envelope |

| Engagement recommendation |

Human approval |

Conditional pre-authorization |

| Engagement execution |

Command approval |

Time-limited or wait |

| Policy modification |

Multi-party consensus |

Never authorized in DIL |

Table 13.

Behavioral envelope dimensions.

Table 13.

Behavioral envelope dimensions.

| Dimension |

Description |

Example Constraint |

| Action space |

What actions are possible |

Classification permitted; engagement prohibited |

| Rate limiting |

Action frequency limits |

Max 3 targeting recommendations/hour |

| Confidence floor |

Minimum certainty threshold |

95% classification confidence required |

| Consequence bounds |

Expected impact limits |

Collateral estimate below threshold |

| Geographic bounds |

Spatial restrictions |

Within the defined AO only |

| Temporal bounds |

Time window restrictions |

Mission window only |

Table 14.

Watchdog types and autonomous responses.

Table 14.

Watchdog types and autonomous responses.

| Watchdog |

Detection Target |

Autonomous Response |

| Behavioral |

Action pattern deviation |

Autonomy reduction |

| Integrity |

Model tampering indicators |

Safe mode entry |

| Input |

Adversarial/anomalous inputs |

Reject input; alert |

| Output |

Unreasonable decisions |

Flag for review; reduce confidence |

Table 15.

Autonomy levels for tactical edge operations.

Table 15.

Autonomy levels for tactical edge operations.

| Level |

Name |

AI Authority |

DIL Applicability |

| 0 |

Manual |

None—human controls all |

Emergency fallback |

| 1 |

Assisted |

Recommend only |

Human co-located |

| 2 |

Partial |

Execute pre-approved routine |

Intermittent connectivity |

| 3 |

Conditional |

Act within envelope |

Primary DIL mode |

| 4 |

Supervised |

Full authority, monitored |

High-trust scenarios |

| 5 |

Full |

Unrestricted |

NEVER AUTHORIZED |

Table 16.

Case study scenario characteristics.

Table 16.

Case study scenario characteristics.

| Characteristic |

Airborne ISR (UAV) |

Ground Sensor |

| DIL Severity |

Intermittent (min/hour) |

Prolonged (days-weeks) |

| Mission Duration |

8–12 hours |

30 days |

| Bandwidth |

256 kbps tactical link |

bps opportunistic |

| Compute Class |

Embedded GPU |

Microcontroller (Cortex-M4) |

| AI Complexity |

Neural network classification |

Threshold detection only |

| Maximum Autonomy |

Level 3–4 |

Level 2 |

| Watchdog Approach |

Peer-based swarm consensus |

Self-diagnostic only |

| Governance |

Collective (quorum required) |

Individual (limited scope) |

Table 17.

Scenario acceptance thresholds (design requirements, not empirical measurements).

Table 17.

Scenario acceptance thresholds (design requirements, not empirical measurements).

| Metric |

Airborne ISR |

Ground Sensor |

| Swarm coordination / Detection accuracy |

100% |

>90% at day 30 |

| Adversarial input detection |

>90% |

N/A (no ML) |

| Governance compliance |

100% |

100% |

| Security power budget |

N/A |

<10% |

| Tamper detection |

N/A |

>99% |

| Authority handoff / Zeroization |

100% |

100% |

Table 18.

Quantitative model parameters: sources and assumptions.

Table 18.

Quantitative model parameters: sources and assumptions.

| Parameter |

Value |

Source Type |

Derivation/Assumption |

| ML-KEM-768 encaps |

1.4M cycles |

Measured |

pqm4 opt implementation [18] |

| ML-DSA-65 sign |

4.0M cycles |

Measured |

pqm4 opt implementation [18] |

| ML-DSA-65 verify |

1.5M cycles |

Measured |

pqm4 opt implementation [18] |

| Envelope check |

1–5 ms |

Estimated |

Policy engine: ~100 rules × 10–50 s/rule |

| Watchdog inference |

10–50 ms |

Estimated |

10K-param NN; TinyML benchmarks [41,42] |

| Link rate |

9.6 kbps |

Assumed |

Representative HF radio data mode |

| Cortex-M4 power |

165 mW active |

Measured |

STM32F4 datasheet @ 168 MHz |

Table 19.

Computational overhead by source.

Table 19.

Computational overhead by source.

| Operation |

Cortex-M4 |

Cortex-A53 |

Source |

| ML-KEM-768 encapsulation |

15–25 ms |

2–4 ms |

pqm4 cycles |

| ML-DSA-65 signature |

40–70 ms |

5–10 ms |

pqm4 cycles |

| ML-DSA-65 verification |

15–25 ms |

2–4 ms |

pqm4 cycles |

| Envelope check (per decision) |

5 ms |

1 ms |

Estimate |

| Watchdog inference cycle |

50 ms |

10 ms |

Estimate |

| Autonomy evaluation |

2 ms |

0.5 ms |

Estimate |

| Audit log entry |

5 ms |

1 ms |

Estimate |

| Total governance/decision |

~65 ms |

~15 ms |

Sum (estimate) |

Table 20.

Resource requirements summary.

Table 20.

Resource requirements summary.

| Resource |

Value |

Assessment |

| Bandwidth overhead (9.6 kbps) |

0.5% increase for PQC |

Acceptable |

| Session establishment |

2.4–7.7 KB per handshake |

Infrequent |

| Pre-positioned material (72h) |

~370 KB/platform |

Accommodated |

| Runtime storage (per 24h) |

~1.8 MB |

Acceptable |

| Security power (Cortex-M4) |

~3.0 J/day (~0.3%) |

Negligible |

Table 21.

Authentication assurance degradation over disconnection (Tactical Assurance Levels).

Table 21.

Authentication assurance degradation over disconnection (Tactical Assurance Levels).

| Disconnection |

Without Peer Validation |

With Peer Validation |

| 0–24 hours |

TAL3 (high) |

TAL3 (high) |

| 24–48 hours |

TAL2 (moderate) |

TAL3 (high) |

| 48–72 hours |

TAL2 (moderate) |

TAL2 (moderate) |

| >72 hours |

TAL1 (basic) |

TAL2 (moderate) |

Table 22.

Byte-level message structure: UGS vehicle classification report.

Table 22.

Byte-level message structure: UGS vehicle classification report.

| Field |

Legacy (bytes) |

TETA (bytes) |

Notes |

| Header (msg type, seq, timestamp) |

12 |

12 |

Identical |

| Sensor ID |

8 |

8 |

Platform identifier |

| Location (MGRS + alt) |

15 |

15 |

10-digit MGRS + 2-byte altitude |

| Classification payload |

24 |

24 |

Class ID, confidence, hash |

| Governance envelope header |

— |

16 |

Version, epoch, authority |

| Action authorization bitmap |

— |

4 |

Permitted actions |

| Decay schedule reference |

— |

8 |

Schedule ID + decay tier |

| Envelope constraints hash |

— |

32 |

SHA-256 integrity |

| Signature (ECDSA / ML-DSA-65) |

64 |

3,309 |

Quantum-resistant overhead |

| Total message size |

123 |

3,428 |

27.9× increase |

Table 23.

Framework comparison.

Table 23.

Framework comparison.

| Framework |

Triad Coverage |

DIL Support |

Governance |

| NIST SP 800-207 |

ZTA only |

Partial |

Limited |

| CNSA 2.0 |

PQC only |

Guidance only |

None |

| NIST AI RMF 1.0 |

AI only |

Not addressed |

Framework |

| ZT for OT |

ZTA + OT |

Degraded only |

Limited |

| TETA-AAGF |

Full Triad |

Native DIL |

Comprehensive |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).