1. Introduction

Driving is an essential means of mobility for maintaining daily life and health among older adults. Beyond enabling transportation to destinations, driving also plays an important role in supporting autonomy and self-esteem in later life [

1]. Reasons for driving cessation among older adults can be broadly classified into health-related and non-health-related factors [

2,

3]. Regardless of the underlying reason, driving cessation has been consistently associated with an increased risk of health deterioration [

4,

5,

6].

In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the importance of driving transition support aimed at minimizing the adverse health effects associated with driving cessation. Such support focuses on preparing older adults for life after driving cessation and enabling them to maintain healthy and active lives. A recent systematic review on driving transition support highlighted several key components, including preparing for driving cessation in advance, developing concrete mobility plans, involving multiple professionals (including healthcare providers) in the decision-making process, and establishing systems that respect the individual’s preferences and autonomy [

7].

To date, only three studies have empirically examined the effectiveness of driving transition support interventions. Two studies evaluated educational programs for individuals with dementia and their families [

8,

9], while one study investigated the effects of a driving cessation transition intervention targeting older adults who had recently stopped driving or planned to cease driving within one year [

10]. That study demonstrated improvements in outing frequency, use of non-driving transportation modes, and self-efficacy regarding post-driving cessation mobility immediately after a six-week intervention; however, these effects were no longer evident at the three-month follow-up [

10]. These findings suggest that short-term, intensive interventions alone may be insufficient and underscore the need for sustained, ongoing support.

Another important issue highlighted by Liddle et al. (2014) [

10] is the difficulty of identifying, at the community level, older adults who have just ceased driving or who plan to stop driving within a year. Consequently, limiting support programs exclusively to individuals with imminent or confirmed driving cessation may not be feasible. Instead, it may be more appropriate to target all older drivers, providing education during the period when they are still driving to both prolong safe driving duration and facilitate preparation for life after driving cessation. This educational approach is consistent with evidence indicating that acceptance of driving cessation often requires time [

11] and with prior research emphasizing the importance of reducing psychological conflict during the transition process [

12]. From this perspective, such an approach can be considered a valid and appropriate form of driving transition support.

Against this background, we have been implementing a proactive class as part of a municipal initiative in the city of Chitose since July 2021. This class provides programs aimed at extending the period of safe driving as well as programs designed to support preparation for life after driving cessation. The present study examined the effects of this class from two perspectives. Specifically, this study aimed to establish a proactive framework for driving transition support delivered during the driving continuation phase and to explore its preliminary effects on awareness, behavior, and driving performance as a basis for future controlled trials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Class

The class was conducted in the city of Chitose, Hokkaido, Japan. The city of Chitose has a population of approximately 100,000 residents, with an aging rate of about 24%. The city experiences heavy snowfall from January to March. The primary modes of daily transportation within the city, other than private automobiles, are buses and taxis; however, service reductions and driver shortages have become significant local challenges.

The class is a proactive program designed to extend the period of safe driving among older drivers while simultaneously supporting preparation for life after driving cessation. The program is implemented through collaboration among multiple professionals (occupational therapists, public health nurses, mental health social workers, and social workers) and multiple organizations, including community comprehensive support centers, preventive care centers, medical institutions, municipal administrative offices, and driving schools.

The class is offered as a single annual package from April to December, with sessions held once per month. Each session lasts 90 minutes, for a total of nine sessions per year (excluding the snow season from January to March). Eligible participants are older drivers aged 65 years or older who reside in the city of Chitose. Participants are recruited through the municipal public relations magazine, social networking services, and posted notices at commercial facilities and administrative offices within the city. In principle, interested individuals register for participation in March of each year and are encouraged to attend sessions monthly; however, individuals wishing to join after April are also accepted. Participation is free of charge.

The class covers content related to extending the safe driving period as well as preparation for life after driving cessation. Each session consists of three components. The first component focuses on providing information related to driving and mobility behaviors, with the aim of ensuring that participants have accurate knowledge regarding community mobility. This component lasts approximately 10 minutes and includes topics such as the driver’s license renewal system, traffic laws, safe driving practices and accident prevention strategies, local transportation services and mobility subsidies, and the relationships between driving and conditions such as dementia, ophthalmologic diseases, and lifestyle-related diseases. The second component aims to enhance participants’ awareness of abilities related to driving and lasts approximately 30 minutes. This component includes stretching exercises, cognitive training, vision training, and hazard perception training. Participants are also provided with guidance on how to continue these exercises at home. The third component consists of group-based activities designed to help participants reflect on their current driving status and develop an image of life after driving cessation. This component lasts approximately 50 minutes. Topics discussed include strategies for safe driving, identification of locations within participants’ daily travel routes where driving feels hazardous, precautions when driving during the snowy season, anticipated changes in daily life after driving cessation, use of alternative transportation options within the community, and perceived inconveniences and benefits associated with driving cessation. After group discussions, the content is shared among all participants. For each class session, one theme is addressed within each component.

In addition to the class sessions, participants are offered a free on-road driving evaluation conducted by certified driving instructors from a driving school on a separate day. This evaluation is intended to promote self-reflection on individual driving ability and lasts approximately 50 minutes.

From July 2021 through December 2025, a total of 41 class sessions were held. During this period, 86 individuals registered for the program, with a cumulative total of 718 participant attendances.

2.2.. Study 1. Effects on Awareness and Behavior

2.2.1. Participants

Participants were older drivers who attended the class at least five times in a single fiscal year between 2022 and 2025. A total of 71 participants met this criterion and were included in the analysis.

2.2.2. Procedures

At the end of the class session during which participants reached their fifth attendance within a given year, they were asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire. The questionnaire assessed perceived changes in awareness and behavior related to driving and mobility. Multiple responses were permitted. The questionnaire items consisted of 11 items identified through interviews with participants in the 2021 program year:

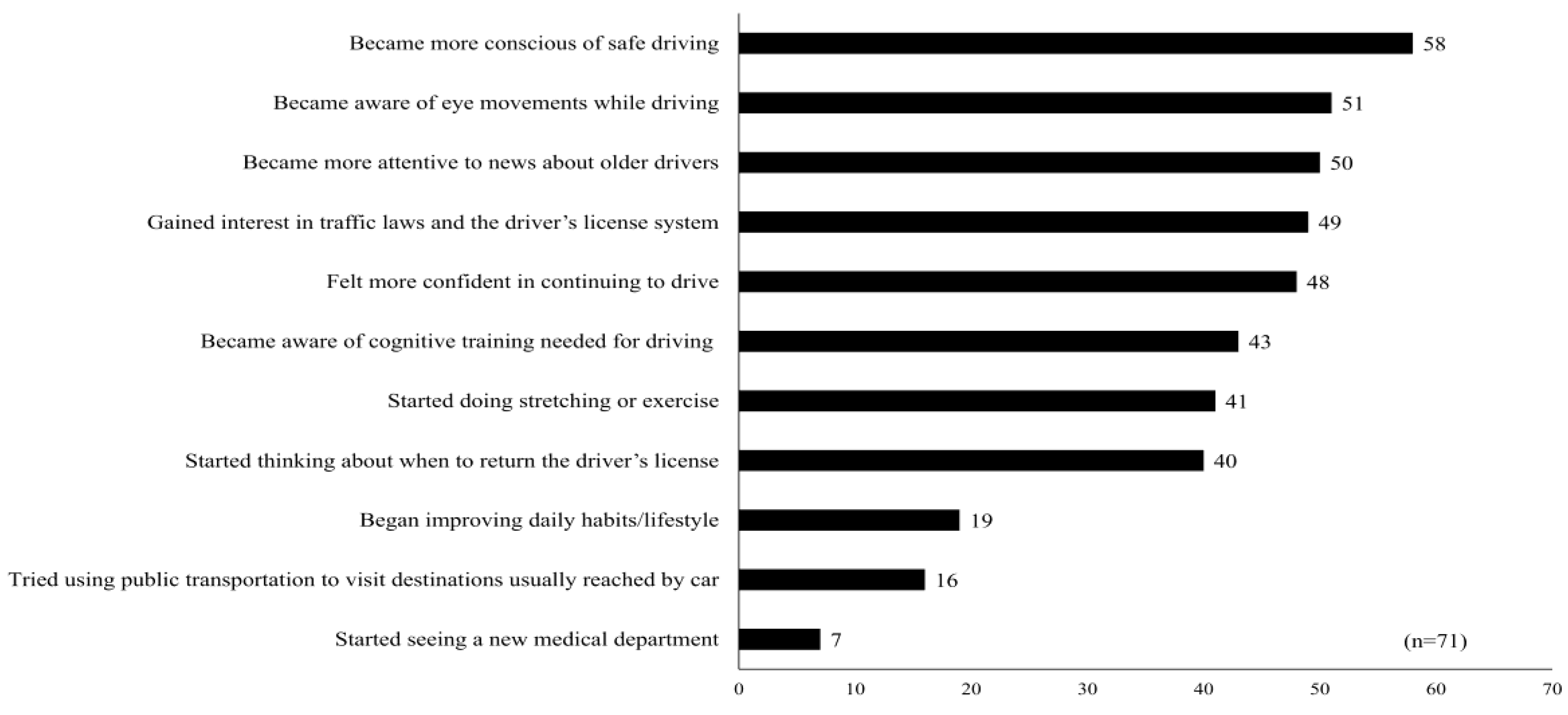

(1) became more conscious of safe driving;

(2) felt more confident in continuing to drive;

(3) became aware of eye movements while driving;

(4) became more attentive to news about older drivers;

(5) became aware of the need for cognitive training for driving;

(6) started doing stretching or exercise;

(7) developed greater interest in traffic laws and the driver’s license system;

(8) started thinking about when to return the driver’s license;

(9) began improving lifestyle habits (e.g., diet and daily routines);

(10) tried using public transportation to visit destinations usually reached by car; and

(11) started visiting a new medical department.

An additional open-ended option (“Other [free-text response]”) was provided; however, no participants selected this option, and it was therefore excluded from the analysis.

2.2.3. Measures and Analysis

For each questionnaire item, the number of participants who selected the item was counted. The total number of respondents for each item was used as the outcome measure.

2.3.. Study 2. Effects on Driving Behavior

2.3.1. Participants

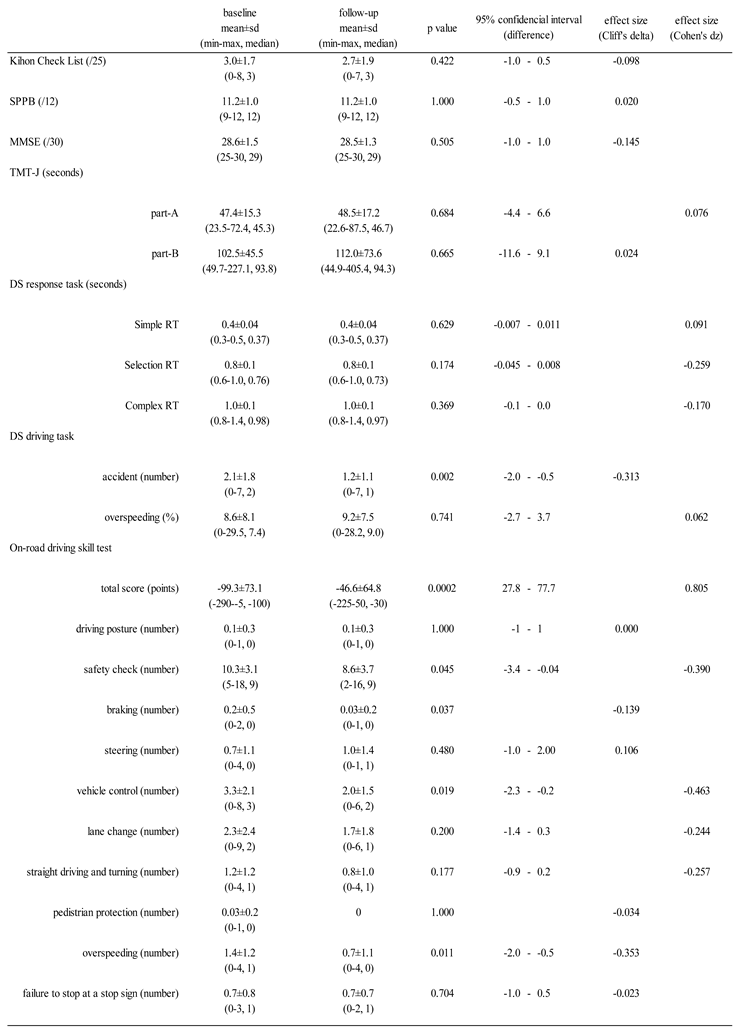

Among 75 individuals who underwent an on-road driving evaluation conducted by certified driving instructors between fiscal years 2021 and 2025, 29 participants who completed driving evaluations at both baseline and the 1-year follow-up were included in the analysis. The mean age of the participants was 74.1 ± 3.8 years (range: 67–82 years), including 15 men and 14 women. Baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1.

2.3.2. Procedures

Participants underwent a 50-minute on-road driving evaluation on a day separate from the class sessions. The evaluation consisted of a 25-minute drive within the city, followed by individualized feedback from a certified driving instructor regarding driving performance. Based on this feedback, participants then completed an additional 15-minute drive within the city. The driving route and the locations at which feedback was provided were standardized across all participants. Evaluations were conducted between 14:00 and 14:50, and the total driving distance was approximately 10 km. The follow-up driving evaluation conducted one year later followed the same protocol. Four certified driving instructors conducted the evaluations. Fifteen participants were evaluated by the same instructor at both baseline and follow-up. After completing the driving evaluation, participants underwent assessments of physical and cognitive function, daily functioning, and off-road driving ability on a separate day at the authors’ affiliated institution.

2.3.3. Measures and Analysis

Driving behavior was assessed using the total score and the number of identified errors for each evaluation item on the standardized on-road driving skill test score sheet designated by the Public Safety Commission. The total score was calculated using a deduction system starting from 100 points. Eleven major deduction categories were defined, each containing multiple subitems: driving posture, safety checks, braking, steering control, vehicle positioning, lane discipline, lane changes, straight driving and turning, pedestrian protection, maximum speed, and test termination. No participants in the present study received deductions for lane discipline; therefore, this category was excluded from the analysis. Among the test termination subitems, all applicable cases involved failure to stop at a stop sign; other subitems were therefore excluded from the analysis.

Three measures were used for physical and cognitive function. Physical function was assessed using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) [

13], which consists of balance, gait speed, and chair stand components and is scored on a 12-point scale, with higher scores indicating better physical function. Cognitive function was assessed using the Trail Making Test–Japanese version (TMT-J) [

14], which includes Part A (connecting numbers sequentially) and Part B (alternating between numbers and letters); completion times for each part were recorded. Global cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

15], which evaluates domains such as orientation, memory, calculation, praxis, and copying, with scores ranging from 0 to 30 (higher scores indicate better cognitive function). Daily functioning was assessed using the Kihon Checklist [

16]. Participants responded “yes” or “no” to 25 items across seven domains: activities of daily living, physical function, nutrition, oral function, social withdrawal, cognitive function, and depressive mood. Scores range from 0 to 25, with lower scores indicating better daily functioning. Off-road driving ability was assessed using a driving simulator (Safety Navi; Honda Motor Co., Ltd.). Outcome measures included reaction times on driving response tasks (simple reaction time, selection reaction time, and complex reaction time), the number of collisions during driving tasks, and the proportion of overspeeding (defined as the ratio of distance driven above the speed limit to the total driving distance). All measures were compared between baseline and the 1-year follow-up.

In the statistical analysis, when assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were met, paired

t-tests were applied to compare baseline and follow-up values. The 95% confidence interval of the difference and effect size (Cohen’s dz) were calculated. Cohen’s dz values were interpreted as follows: < 0.20, negligible; 0.20–0.49, small; 0.50–0.79, medium; and ≥ 0.80, large [

17]. When assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were not met, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. The 95% confidence interval of the difference was estimated using the Hodges–Lehmann estimator, and effect sizes were calculated using Cliff’s delta. Cliff’s delta values were interpreted as follows: < 0.147, negligible; 0.147–0.329, small; 0.330–0.473, medium; and ≥ 0.474, large [

18]. The significance level was set at 5%. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.3.

3. Results

3.1. Study 1. Effects on Awareness and Behavior

Among 71 participants included in the analysis, the most frequently reported change was becoming more conscious of safe driving (n = 58). This was followed by becoming aware of eye movements while driving (n = 51), becoming more attentive to news about older drivers (n = 50), and developing greater interest in traffic laws and the driver’s license system (n = 49). Feeling more confident in continuing to drive was reported by 48 participants, and increased awareness of the need for cognitive training for driving was reported by 43 participants. With respect to health-related behaviors, 41 participants reported starting stretching or exercise, and 19 reported improving lifestyle habits such as diet and daily routines. Forty participants reported beginning to think about when to return their driver’s license. In terms of mobility behavior, 16 participants reported trying to use public transportation to visit destinations they usually reached by car. Seven participants reported visiting a new medical department; all of these visits were to ophthalmology clinics (

Figure 1).

3.2. Study 2. Effects on Driving Behavior

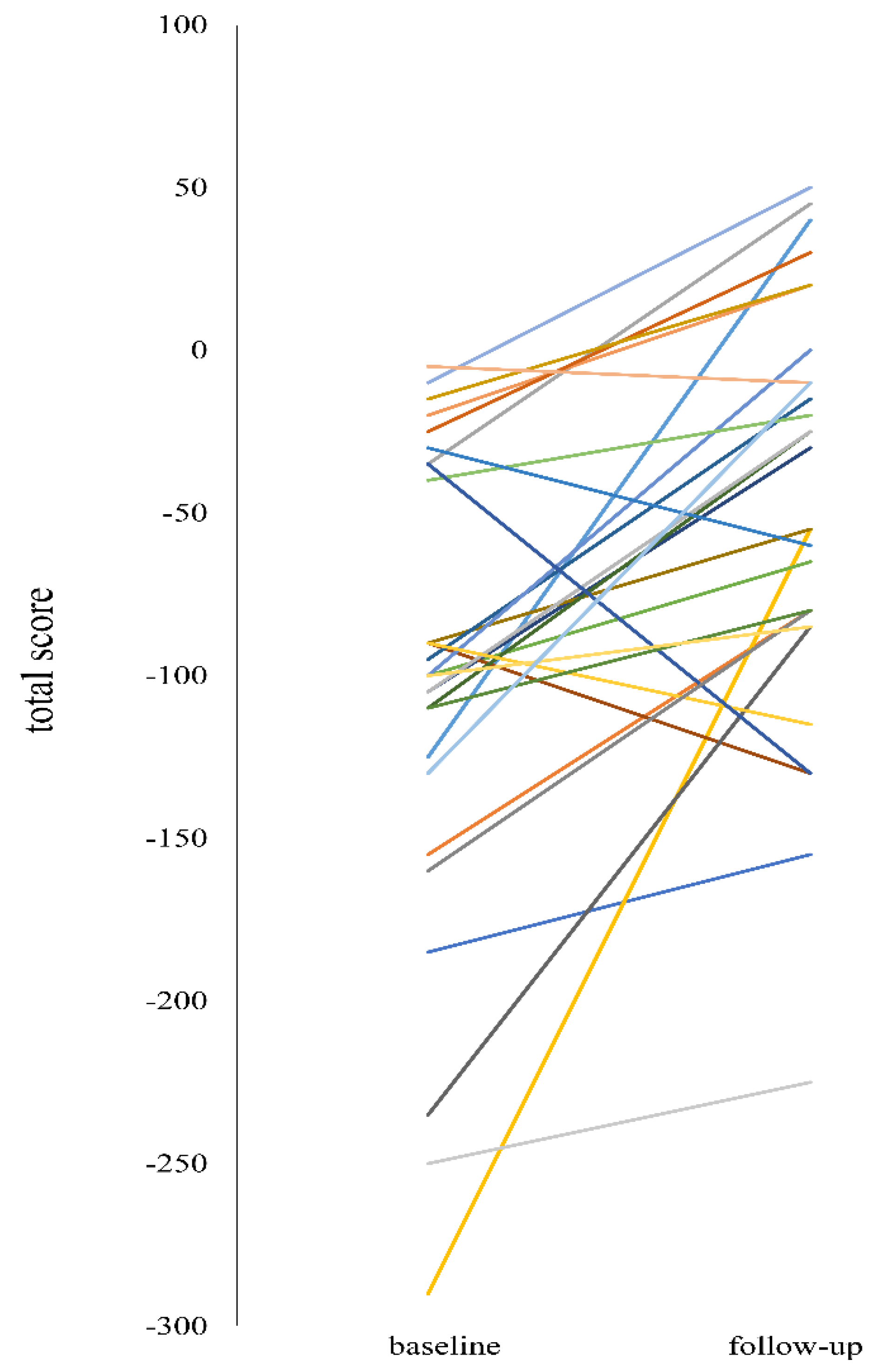

The total score on the on-road driving skill test improved significantly at follow-up compared with baseline (p < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.805) (

Figure 2).

Regarding individual evaluation items, the number of identified errors decreased significantly for braking (p = 0.037, Cliff’s delta = -0.139), vehicle control (p = 0.019, Cohen’s dz = -0.463), and overspeeding (p = 0.011, Cliff’s delta = -0.353). No significant change was observed in the number of errors related to failure to stop at a stop sign (p = 0.704, Cliff’s delta = -0.023). With respect to physical and cognitive function, daily functioning, and off-road driving ability, no significant differences were observed between baseline and follow-up, except for the number of accidents during the driving simulator task, which decreased significantly at follow-up (p = 0.002, Cliff’s delta = -0.313) (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of a proactive class for older drivers on awareness and behavior (Study 1) as well as on on-road driving behavior (Study 2). The findings indicate that participation in the class was associated with changes in self-awareness related to driving, risk perception, health-related behaviors, and trial use of alternative transportation modes, and that, longitudinally, participation was also associated with improvements in on-road driving skill test performance. These results suggest that the dual focus of the class—extending the period of safe driving while preparing for life after driving cessation—may facilitate multidimensional behavioral change.

In Study 1, many participants reported increased interest in driving-related information and enhanced self-efficacy regarding continued driving. Information provision during the class, activities aimed at increasing awareness of driving-related abilities, and feedback obtained through on-road evaluations likely contributed to improved self-understanding. Furthermore, increased sensitivity to social and institutional information—such as paying more attention to news about older drivers, developing interest in traffic laws and the driver’s license system, and beginning to consider the timing of driver’s license return—aligns with prior research emphasizing the importance of respecting individual preferences and autonomy in the driving transition process [

7].

Importantly, the effects of the class extended beyond driving behavior to health-related and healthcare-seeking behaviors. A proportion of participants reported initiating stretching or exercise and improving lifestyle habits, suggesting that the exercise and cognitive training component of the class may have contributed to behavioral change in daily life. In addition, the observed increase in ophthalmology visits indicates that information provided about the relationship between visual function and driving may have prompted appropriate healthcare utilization. This is particularly noteworthy given that early detection of glaucoma—often asymptomatic in its early stages—is essential for safe driving [

19]. Moreover, the reported trial use of public transportation is consistent with the class objective of encouraging experimentation with alternative mobility options during the driving continuation phase rather than immediately before driving cessation. Given the vulnerability of local transportation systems in the city of Chitose, early exposure to non-driving transportation modes may help mitigate perceived inconvenience after driving cessation. Through group-based activities and dialogue with peers, the class also appears to provide opportunities for participants to update their perspectives on driving and community mobility, consistent with prior findings on peer interaction and reflective learning [

20].

In Study 2, total scores on the on-road driving skill test improved significantly at the 1-year follow-up, and the number of identified errors related to braking, vehicle control, and overspeeding decreased. Previous research has shown that driving ability in older adults tends to decline over time due to changes in health status [

21]. Although the follow-up period in the present study was relatively short, improvements in driving performance were observed, suggesting that continued learning through the class and feedback from certified driving instructors may have positively influenced actual driving behavior. In addition, region-specific content, such as group discussions on winter driving and hazard perception training, may have been reflected in improved on-road performance.

In contrast, no change was observed in errors related to failure to stop at stop signs. In Japan, failure to comply with stop signs is the most common traffic violation [

22], and compliance with stop signs may be difficult to improve through conscious effort alone. More focused interventions—such as route designs incorporating stop-sign locations and feedback specifically targeting stop compliance—may therefore be necessary.

Although no significant changes were observed in physical function (SPPB), cognitive function (TMT-J, MMSE), daily functioning (Kihon Checklist), or off-road driving ability, a significant reduction was observed in the number of accidents during the driving simulator task. This finding suggests that the class may not have improved underlying functional capacity per se, but rather altered hazard perception and attentional behavior within existing functional limits. The class can thus be characterized as an intervention that supports safe driving through accurate self-understanding and adaptive behavior, rather than through direct remediation of functional decline. From this perspective, the class may influence metacognitive abilities related to driving [

23].

The fact that the class is provided as a year-long package is also noteworthy. Previous studies have reported that the effects of short-term, intensive interventions diminish within three months [

10]. In contrast, the present class combines nine sessions of continuous learning with optional on-road evaluations, which may have contributed to the maintenance and reinforcement of awareness and behavioral changes. Continued participation may also provide opportunities to initiate gradual driving regulation or self-regulation behaviors [

24], supporting a shift from interventions focused solely on the period immediately before or after driving cessation toward earlier, more comprehensive engagement.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, Study 1 employed a cross-sectional design without a control group and relied on self-reported changes in awareness and behavior; therefore, causal relationships between class participation and observed changes cannot be established. Selection bias is also possible, as older adults with greater interest in safe driving or health behaviors may have been more likely to continue participating. Additionally, because participants voluntarily enrolled in the class after reviewing its content, the influence of attention bias cannot be excluded. Second, Study 2 included only 29 participants who completed both baseline and follow-up on-road evaluations, and these individuals may differ from those who underwent only a single evaluation or discontinued follow-up. Although the driving route was standardized, repeated exposure to the same approximately 10-km course may have introduced familiarity or learning effects. Third, because four driving instructors conducted the evaluations and approximately half of the participants were assessed by different instructors at baseline and follow-up, inter-rater variability cannot be fully ruled out. Fourth, this study did not track actual driving cessation timing or long-term health outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, decline in daily functioning, or healthcare and long-term care utilization); therefore, the medium- to long-term effects of class participation on safe driving duration and health outcomes remain unclear.

From a broader perspective, the present study should be interpreted as a conceptual and feasibility-oriented investigation. The findings are not intended to provide definitive evidence of effectiveness but rather to inform the design, outcome selection, and implementation strategy of an upcoming randomized controlled trial evaluating proactive driving transition support delivered during the driving continuation phase.

Future research should employ prospective study designs with control groups to examine associations between class participation (including participation frequency), duration of driving continuation, post-cessation inconvenience, and health outcomes. Based on the present findings, development of modules targeting specific driving behaviors—such as stop-sign compliance and speed management—and the introduction of tailored feedback based on individual driving evaluation results should also be considered. Furthermore, the applicability and external validity of the class framework should be examined not only in municipalities with characteristics similar to the city of Chitose (e.g., heavy snowfall, reduced public transportation services), but also in urban areas with more accessible public transportation systems.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that a proactive driving transition support class for older drivers may be associated with changes in driving-related awareness, health-related and healthcare-seeking behaviors, trial use of alternative transportation modes, and improvements in on-road driving skills. These findings extend beyond conventional support targeting individuals with imminent or confirmed driving cessation and underscore the importance of establishing continuous support spanning the driving continuation phase through post-cessation life. Such an approach may contribute to community-based efforts to balance safe mobility and health maintenance among older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sasaki, T., Yamada, K., Yamakita, T., Sakuta, N., Yoshida, H, and Tominaga, T.; Methodology, Sasaki, T., Yamada, K., and Yamakita, T.; Formal Analysis, Sasaki, T., and Yamada, K.; Investigation, Sasaki, T., Yamada, K., Yamakita, T., Sakuta, N., Yoshida, H, and Tominaga, T.; Data Curation; Sasaki, T., and Yamada, K.; Original Draft Preparation, Sasaki, T.; Writing-Review and Editing, Yamada, K., and Yamakita, T.; Supervision, Sasaki, T., and Yamada, K.; Project Administration; Sasaki, T., Yamada, K., and Yamakita, T.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research design and the research instrument (the questionnaire) were approved by the city of Chitose and the Research Ethics Committee of Hokkaido Chitose College of Rehabilitation (Approval Number R02104) The intent to participate in this study was confirmed by the return of the questionnaire and the written consent form.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study will be available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Odenheimer, G.L. Dementia and the older driver. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 1993, 9(2), 349-364. [CrossRef]

- Antin, J. F.; Guo, F.; Fang, Y.; Dingus, T.A.: Hankey, J. M.; Perez, M. A. The influence of functional health on seniors’ driving risk. J. Transp. Health 2017, 6, 237-244. [CrossRef]

- Maliheh, A.; Nasibeh, Z.; Yadollah, A.M.; Hossein, K.M.; Ahmad, D. Non-cognitive factors associated with driving cessation among older adults: An integrative review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2023, 49, 50-56. [CrossRef]

- Choi M.; Lohman, M.C.; Mezuk, B. Trajectories of cognitive decline by driving mobility: evidence from the health and retirement study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29(5), 447-453. [CrossRef]

- Chihuri, S.; Mielenz, T.J.; DiMaggio, C.J.; Betz, M.E.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Jones, V.C.; Li G. Driving cessation and health outcomes in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64(2), 332-341. [CrossRef]

- Hirai, H.; Ichikawa, M.; Kondo, N.; Kondo, K. The risk of functional limitations after driving cessation among older Japanese adults: The JAGES cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30(8), 332-337. [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, A.E.; Stapleton, T.; Bloss, J.; Geinas, I.; Harries, P.; Choi, M.; Margot-Cattin, I.; Mazer, B.; Patomella, A.H.; Swanepoel, L.; Niekerk, L.V.; Unsworth, C.A.; Vrkljan, B. A systematic review of effective interventions and strategies to support the transition of older adults from driving to driving retirement/cessation. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, igae054. [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.A.; D’Ambrosio, L.A.; Mohyde, M.; Carruth, A.; Tracton-Bishop, B.; Hunter, J.C.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Coughlin, J.F. At the crossroads: Development and evaluation of a dementia caregiver group intervention to assist in driving cessation. Gerontol. Geriatr. Edu. 2008, 29(4), 363-382. https://doi. org/10.1080/02701960802497936.

- Dobbs, B.M.; Harper, L.A.; Wood, A. Transitioning from driving to driving cessation: The role of specialized driving ces sation support groups for individuals with dementia. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2009, 25, 73-86. [CrossRef]

- Liddle, J.; Haynes, M.; Pachana, N.A.; Mitchell, G.; McKenna, K.; Gustafsson, L. Effect of a group intervention to promote older adults’ adjustment to driving cessation on community mobil ity: A randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist 2014, 54(3), 409-422. [CrossRef]

- Donorfio, L.K.; D’Ambrosio, L.A.; Coughlin, J.F. To drive or not to drive, that isn’t the question – the meaning of self-regulation among older drivers. J. Safety. Res. 2009, 40(3), 221-226. https://. [CrossRef]

- Betz, M.E.; Hill, L.L.; Fowler, N.R.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Han, S.D.; Johnson, R.L.; Meador, L.; Omeragic,F.; Peterson, R.A.; Matlock, D.D. Is it time to stop driving?: A randomized clinical trial of an online decision aid for older drivers. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70(7), 1987-1996. https://doi: 10.1111/jgs.17791.

- Welch, S.A.; Ward, R.E.; Beauchamp, M.K.; Leveille, S.G.; Travison, T.; Bean, J.F. The short physical performance battery (SPPB): A quick and useful tool for fall risk stratification among older primary care patients. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1646-1651. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Yamada, K.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Takimoto, M. Validation and clinical application of a developed pedal coordination assessment device for older drivers. Healthcare 2025, 13(5), 537. [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12(3), 189-198. https://doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

- Watanabe, D.; Yoshida, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Miyachi, M.; Kimura, M. Validation of the Kihon Checklist and the frailty screening index for frailty defined by the phenotype model in older Japanese adults. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 478. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, Second edition. p224-227, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

- Romano, J.; Kromrey, J.D.; Coraggio, J.; Skowronek, J. Appropriate statistics for ordinal level data: Should we really be using t-test and Cohen’s d for evaluating group differences on the NSSE and other surveys?. Annual Meeting of the Florida Association of Institutional Research 2006.

- Correa, P.C.; Medeiros, F.A.; Abe, R.Y.; Diniz-Filho, A.; Gracitelli, C.P.B. Assessing driving risk in patients with glaucoma. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2019, 82(3), 245-252. https://. [CrossRef]

- Betz, M. E.; Scott, K.; Jones, J.; DiGuiseppi, C. Are you still driving? Meta-synthesis of older adults’ preferences for communication with healthcare providers about driving. Traffic. Inj. Prev. 2016, 17(4), 367-373. https://doi:10.1080/15389588.2015.1101078.

- Falkenstein, M.; Karthaus, M.; Brune-Cohrs, U. Age-related diseases and driving safety. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 80. https://. [CrossRef]

- Traffic Statistics, National Policy Agency, Japan. 2024.

- Antonanzas, J.L.; Salavera, C. Validation of the metacognitive skills questionnaire for drivers of vehicles (CHMC). Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. 2023. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1054279.

- Friedland, J.; Rudman, D.L. From confrontation to collaboration: Making a place for dialogue on seniors’ driving. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2009, 25(1), 12-23. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |