1. Introduction

Influenza is a globally prevalent infectious disease caused by influenza viruses, affecting all age groups. Studies have shown that approximately 500,000 deaths worldwide are associated with influenza annually, with about 90% of influenza-related deaths occurring in individuals aged ≥65 years [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Influenza vaccination is the most effective method for preventing influenza [

5], significantly reducing the risk of illness in the population [

6]. In China, influenza vaccines are not included in the national immunization program, and vaccination coverage is relatively low, at 3.16% in the 2020/21 season and 2.47% in the 2021/22 season [

7], posing a substantial burden on global public health. VE is used to assess the real-world effectiveness of vaccines, particularly their practical effectiveness against continuously evolving and circulating influenza viruses[

8]. Currently, there is no data on the VE of influenza vaccination in Wuhan. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the VE of influenza vaccination in Wuhan during the 2024-2025 season using a test-negative case-control design.

The test-negative case-control design is a modification of the traditional case-control study[

9]. It has been widely used in recent years for evaluating vaccine VE. This design enables timely estimation of VE during the early, middle, and late stages of the influenza season and effectively reduces bias arising from healthcare-seeking behavior and disease misclassification[

10]. It has been applied for annual VE monitoring in several countries, including the United States[

11], Canada [

12], and Australia [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

Cases were sourced from outpatient and emergency departments of 41 hospitals (at or above the secondary level) in Wuhan that conducted influenza virus RT-PCR testing, see

Table A1. Based on the seasonality of influenza epidemics in Wuhan, the enrollment period was from October 1, 2024, to April 30, 2025. According to the National Influenza Surveillance Technical Guidelines (2017 Edition)[

14], patients meeting the definition of influenza-like illness (ILI) — fever (body temperature ≥38 °C) accompanied by cough or sore throat — who underwent influenza virus RT-PCR testing and were older than 6 months were included in the study. Basic demographic information of the patients, including sex and age, as well as the testing date and test results, were collected.

2.2. Vaccination Status

The virus strains recommended by the WHO for the 2024-2005 Northern Hemisphere influenza season were: A(H1N1)pdm09: A/Victoria/4897/2022 (H1N1)pdm09-like virus; A(H3N2): A/Thailand/8/2022 (H3N2)-like virus; B/Victoria: B/Austria/1359417/2021 (B/Victoria lineage)-like virus[

15]. In China, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV3), quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV4), and trivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV3) are used, with LAIV3 administered only to children aged 3-17 years[

16]. Patient vaccination information, including vaccine type (IIV3, IIV4, or LAIV3) and vaccination date, was obtained by querying the immunization planning information management system using the patient’s identity card (ID). According to Wuhan’s vaccination policy, vaccination in the current season was defined as receiving the influenza vaccine between July 1, 2024, and March 31, 2025. Vaccination in the previous season was defined as receiving the influenza vaccine between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024. To explore the impact of vaccination on VE, participants’ vaccination status was categorized into four types: unvaccinated, vaccinated in both seasons, vaccinated only in the previous season(2023-2024), and vaccinated only in the current season(2024-2025). Patients who had received an influenza vaccine at least 14 days before their visit were considered immunized. Influenza vaccines administered within 14 days before the visit were excluded from the analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The test-negative case-control design method was used. Characteristics of the influenza RT-PCR-positive case group and the RT-PCR-negative control group were compared, stratified by influenza virus type, vaccine type, and age group. The χ2 test was used to compare differences, with a significance level set at P < 0.05. Conditional logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for influenza vaccination within each subgroup of cases and controls, adjusting for sex and age, and to calculate the adjusted VE, with VE = (1 − OR) × 100%. Statistical significance was determined when the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for VE was greater than zero. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.5.1.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 122,726 ILI patients were included in the study, consisting of 23,302 RT-PCR-positive cases and 99,424 negative controls. Among the confirmed cases, 99.2% (23,1266/23,302) were from tertiary hospitals, while 0.8% (176/23,302) were from secondary hospitals. The proportion of males in the case group (50.6%, 11,789/23,302) was lower than that in the control group (52.1%, 51,846/99,424). Regarding age distribution, 32.2% of cases were aged 19–59 years, and 22.1% were aged ≥70 years. The overall influenza vaccination rate was 5.93% (7,273/122,726), with a vaccination rate of 3.7% (851/23,302) in the case group and 6.5% (6,422/99,424) in the control group. In terms of vaccine types, the IIV4 vaccination rate in the case group was 3.3% (764/23,302), and the LAIV3 vaccination rate was 0.4% (87/23,302). In the control group, the IIV3 vaccination rate was 0.001% (6/99,424), the IIV4 vaccination rate was 5.92% (5,881/99,424), and the LAIV3 vaccination rate was 0.5% (535/99,424). All differences were statistically significant, except for vaccine type. See

Table 1.

3.2. Weekly Distribution of Influenza Detection

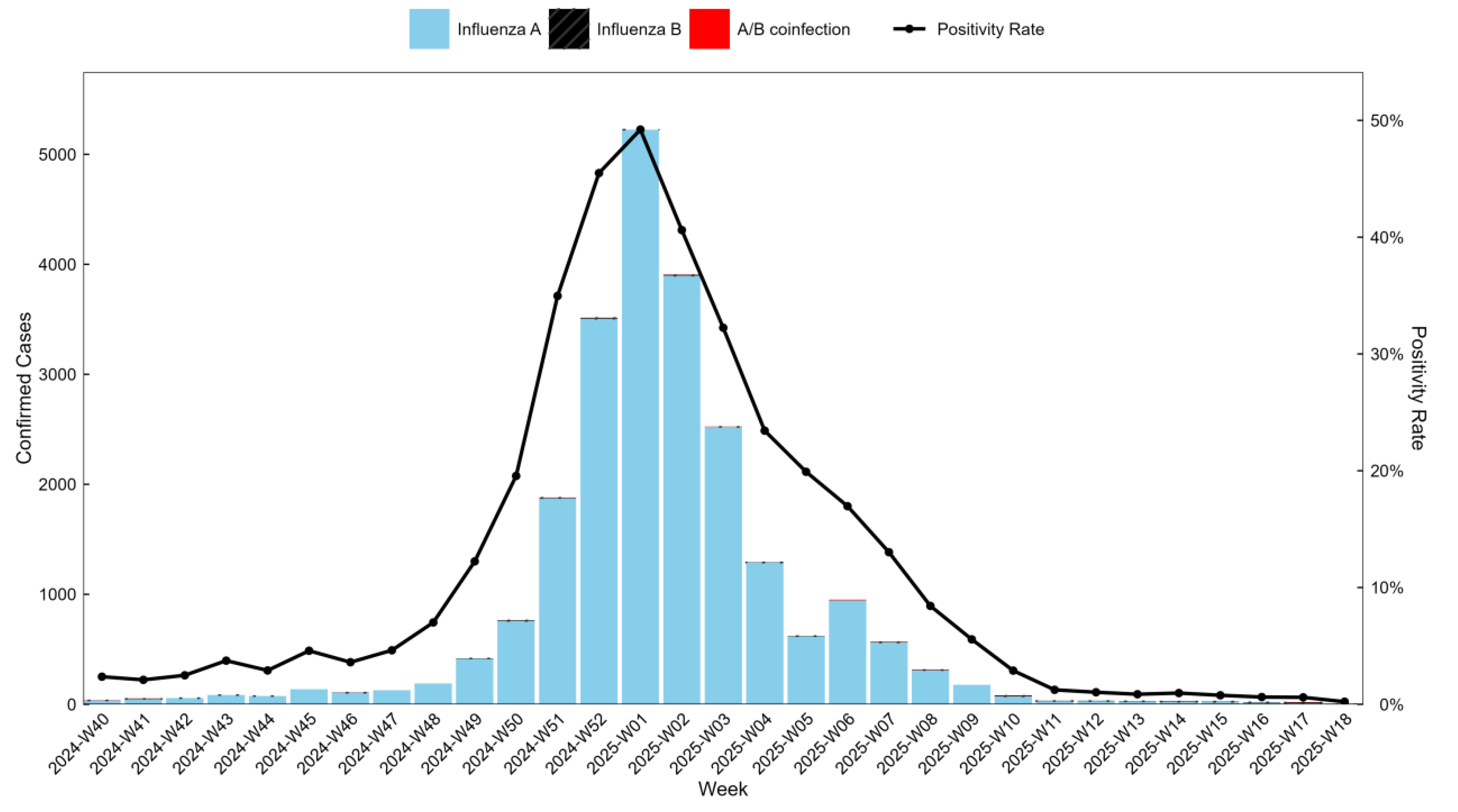

Among RT-PCR-positive cases, influenza A accounted for 99.51% (23,187/23,302), influenza B for 0.33% (76/23,302), and A/B co-infection for 0.17% (39/23,302). The number of influenza-positive cases and the positivity rate increased initially, peaking in week 1 of 2025 (49.21%, 5,225/10,617), and then decreased. By week 13 of 2025, the positivity rate dropped to 0.86% (28/3,244), indicating the influenza epidemic in Wuhan had effectively ended. See

Figure 1.

3.3. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness

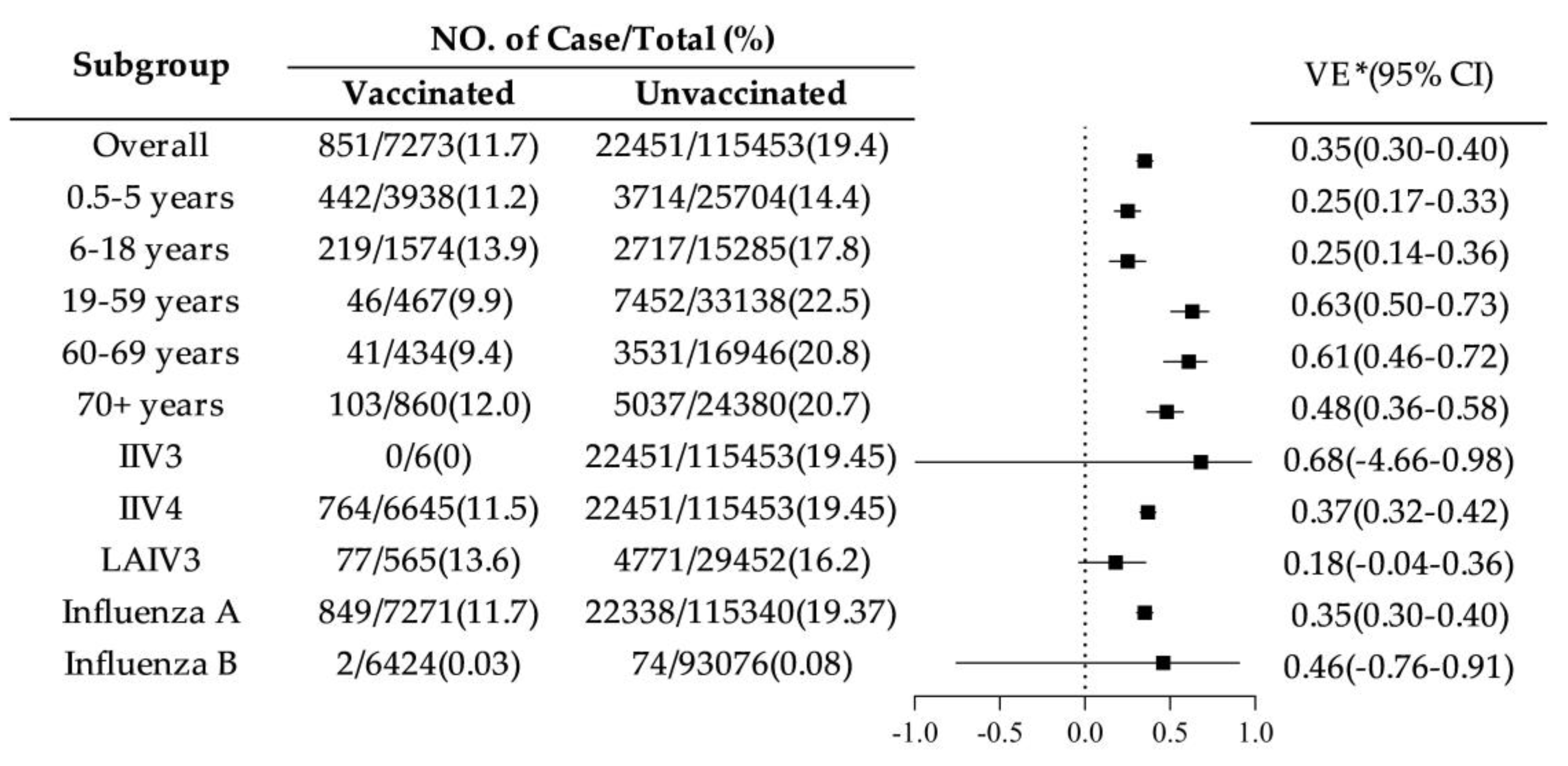

3.3.1. VE by Age Group, Vaccine Type, and Influenza Subtype

The adjusted overall VE for the 2024–2025 season was 35% (95% CI: 30.1%-39.8%). Among age groups, VE was lower in children aged 0.5–5 years (25%, 95% CI: 17%-33%) and 6–18 years (25%, 95% CI: 14%-36%). VE was highest in adults aged 19–59 years (63%, 95% CI: 50%-73%) and 60–69 years (61%, 95% CI: 46%-72%). Among vaccine types, VE for IIV4 was 37% (95% CI: 32%-42%), for IIV3 was 68% (95% CI: -466%-98%), and for LAIV3 (ages 3-17 only) was 18% (95% CI: -4%-36%). For influenza virus subtypes, VE against influenza A was 35% (95% CI: 30%-40%), and against influenza B was 46% (95% CI: -76%-91%). See

Figure 2.

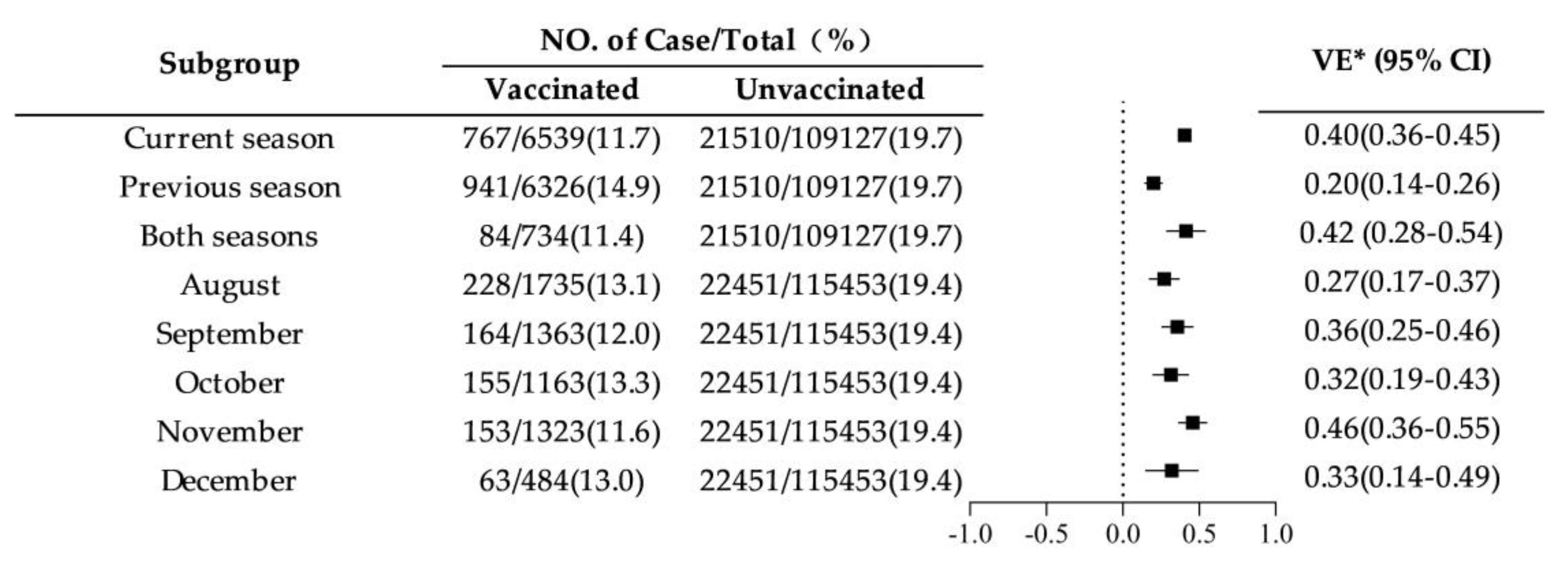

3.3.2. VE by Influenza Season and Vaccination Month

Across different influenza seasons, VE was highest for vaccination in both consecutive seasons (42%, 95% CI: 28%-54%) and for vaccination in the current season only (40%, 95% CI: 36%-45%), while it was lowest for vaccination in the previous season only (20%, 95% CI: 14%-26%). Among different vaccination months, VE was highest for vaccination in November at 46% (95% CI: 36%-55%), and lowest for vaccination in August at 27% (95% CI: 17%-37%). See

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first evaluation of influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) in Wuhan, using the widely adopted test-negative case-control design. The influenza vaccination rate in Wuhan during the 2024/25 season was 5.9%, which is relatively low compared to other regions. For context, the vaccination rate in China was 3.16% in the 2020/21 season and 2.47% in the 2021/22 season, far lower than the 49.3% vaccination rate for individuals aged ≥6 months in the United States during the 2022/23 epidemic season[

17]. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in vaccine promotion and public perceptions, as seasonal influenza vaccination is often seen as less critical in China.

The overall adjusted VE for influenza vaccination in Wuhan during the 2024–2025 season was 35%, which is lower than the VE observed in Chongqing during the 2018–2022 epidemic season (44.4%)[

18]and in Hangzhou during the 2023–2024 season (48%) [

19]. This VE is comparable to interim VE estimates from 16 European countries for the 2022/23 season (28%–46%) [

20]. The higher VE in the 19–59 age group (63%, 95% CI: 50%–73%) likely reflects better immune resistance and health status in this population compared to other age groups[

21]. In contrast, VE was lower in children aged 0.5–5 years (25%, 95% CI: 17%–33%) and in adolescents aged 6–18 years (25%, 95% CI: 14%–36%). These findings are consistent with studies in other regions of China, where lower VE in children may be attributed to the relatively underdeveloped immune systems in younger populations [

22,

23]. The VE in older adults aged 60–69 years (60.7%, 95% CI: 46%–72%) was second only to that in the 19–59 age group, highlighting the importance of promoting influenza vaccination in high-risk groups, such as the elderly[

24]. This is consistent with recommendations from Liao

et al.[

25], who suggested prioritizing vaccination for individuals aged >60 years and children aged 6–59 months.

This study also found that vaccination in both consecutive seasons or in the current season only provided better protection compared to no vaccination. This is in line with the recommendations of the Technical Guidelines for Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in China, which advocate for annual vaccination[

26]. The higher VE values for those vaccinated in both the current and previous seasons may reflect the cumulative effect of repeated vaccinations. However, some studies have shown that annual consecutive influenza vaccination may not provide an additive immune effect and could potentially weaken immune responses over time due to changes in immune memory and the body’s adaptive responses to repeated vaccinations[

27]. Additionally, the study found that the protective effectiveness was highest for those vaccinated in November (46%, 95% CI: 36%–55%) and lowest for those vaccinated in August (27%, 95% CI: 17%–37%). This highlights the need for further optimization of vaccination timing, which may enhance overall vaccine effectiveness. Additional research is required to better understand the influence of vaccination timing and frequency on VE.

In summary, influenza vaccination provided significant protection for the population in Wuhan during the 2024–2025 epidemic season, particularly among adults. To further enhance overall vaccine effectiveness, it is recommended to continue strengthening influenza vaccination campaigns, with a focus on increasing coverage among children and adolescents. In addition, optimizing vaccination timing and encouraging timely annual vaccination should be prioritized.

Limitations: This study did not include genetic subtyping of circulating influenza A strains (e.g., A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2)), which could have provided additional insights into strain-specific VE. Furthermore, the lack of detailed patient information, including residential address, chronic disease status, date of symptom onset, and antiviral drug use, may have impacted the accuracy of VE calculations.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that influenza vaccination provided protection during the 2024–2025 epidemic season in Wuhan. The VE was highest among adults, with vaccination in both consecutive seasons or in the current season offering optimal protection. Additionally, vaccination in November proved to be the most effective, highlighting the importance of timely vaccination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Pei Zhang, Xiaokun Yang and Banghua Chen; methodology, Pei Zhang and Xiaokun Yang; data curation, Pei Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Pei Zhang and Banghua Chen; writing—review and editing, Pei Zhang and Banghua Chen.; project administration, Pei Zhang and Banghua Chen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2024YFC2311500).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it was a retrospective analysis of routinely collected, anonymized data obtained from the hospital information system (HIS), with no direct participant involvement or identifiable personal information. The study was conducted in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions on data sharing, as the data were derived from the hospital information system (HIS). Access to the data may be granted by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to approval by the data-owning institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. odds ratio.:

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VE |

Vaccine Effectiveness |

| ILI |

Influenza-like illness |

| OR |

Odds ratio |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Source Hospitals and Number of Cases.

Table A1.

Source Hospitals and Number of Cases.

| Hospital Level |

Hospital Name |

Number Tested by RT-PCR |

| Secondary |

|

1703 |

| |

Wuhan NO.9 Hospital |

969 |

| |

Hubei RongJun Hospital |

655 |

| |

Wuhan East Lake Hospital |

55 |

| |

Wuhan Red Cross Hospital |

24 |

| Tertiary |

|

121023 |

| |

Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital |

382 |

| |

Hubei Government Hospital |

239 |

| |

The First People’s Hospital Of Jiangxia District, Wuhan City |

160 |

| |

People’s Liberation Army Airborne Corps Hospital |

17 |

| |

Hospital of Wuhan University of Science and Technology |

17 |

| |

Wuhan Children’s Hospital |

14223 |

| |

The Central Hospital Of Wuhan |

13135 |

| |

Wuhan NO.1 Hospital |

12812 |

| |

Maternal and Child Health Hospital Of Hubei Province |

10753 |

| |

Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology |

8699 |

| |

Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology |

6496 |

| |

Wuhan Puren Hospital |

6195 |

| |

The Fifth Hospital Of Wuhan |

5543 |

| |

The Forth Hospital Of Wuhan |

4350 |

| |

China Resources & Wuhan Iron and Steel General Hospital |

3775 |

| |

Zhongnan Hospital Of Wuhan University |

3476 |

| |

The Third People’s Hospital Of Hubei Province |

2635 |

| |

Tianyou Hospital Affiliated To Wuhan University Of Science & Technology |

2003 |

| |

Wuhan Third Hospital |

1821 |

| |

Hubei Provincial Hospital of TCM |

1418 |

| |

Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital |

852 |

| |

General Hospital of Central Theater Command |

696 |

| |

Wuhan Hospital Of Traditional Chinese Medicine |

504 |

| |

Hubei General Hospital |

118 |

| |

Hubei Cancer Hospital |

2 |

| |

Wuhan Caidian District People’s Hospital |

3325 |

| |

Wuhan Asia General Hospital |

2778 |

| |

Taikang Tongji (Wuhan) Hospital |

2176 |

| |

The Eight Hospital Of Wuhan |

1445 |

| |

Wuhan Hankou Hospital |

1120 |

| |

Wuhan Taikang Hospital |

59 |

| |

Geriatric Hospital Affiliated to Wuhan University of Science and Technology |

8 |

| |

Wuhan Huangpi District People’s Hospital |

6075 |

| |

Wuhan Dongxihu District People’s Hospital |

2681 |

| |

The Sixth Hospital Of Wuhan |

606 |

| |

THE SECOND HOSPITAL OF WISCO |

384 |

| |

Wuhan Hanyang Hospital |

45 |

| Total |

|

122726 |

References

- Huo, X.; Zhu, F. Influenza Surveillance in China: A Big Jump, but Further to Go. The Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e436–e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuliano, A.D.; Roguski, K.M.; Chang, H.H.; Muscatello, D.J.; Palekar, R.; Tempia, S.; Cohen, C.; Gran, J.M.; Schanzer, D.; Cowling, B.J.; et al. Estimates of Global Seasonal Influenza-Associated Respiratory Mortality: A Modelling Study. The Lancet 2018, 391, 1285–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Up to 650 000 People Die of Respiratory Diseases Linked to Seasonal Flu Each Year . Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/13-12-2017-up-to-650-000-people-die-of-respiratory-diseases-linked-to-seasonal-flu-each-year (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Reber, A.J.; Chirkova, T.; Kim, J.H.; Cao, W.; Biber, R.; Shay, D.K.; Sambhara, S. Immunosenescence and Challenges of Vaccination against Influenza in the Aging Population. Aging Dis 2012, 3, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paules, C.; Subbarao, K. Influenza. The Lancet 2017, 390, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuwarda, R.F.; Alharbi, A.A.; Kayser, V. An Overview of Influenza Viruses and Vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.T.; Peng, Z.B.; Ni, Z.L.; Yang, X.K.; Guo, Q.Y.; Zheng, J.D.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y.P. Investigation on Influenza Vaccination Policy and Vaccination Situation during the Influenza Seasons of 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 56, 1560–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.G.; Feng, S.; Cowling, B.J. Potential of the Test-Negative Design for Measuring Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: A Systematic Review. Expert Review of Vaccines 2014, 13, 1571–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, H.Q.; Belongia, E.A. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: New Insights and Challenges. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2021, 11, a038315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, W.; Hirota, Y. Basic Principles of Test-Negative Design in Evaluating Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness. Vaccine 2017, 35, 4796–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frutos, A.M.; Price, A.M.; Harker, E.; Reeves, E.L.; Ahmad, H.M.; Murugan, V.; Martin, E.T.; House, S.; Saade, E.A.; Zimmerman, R.K.; et al. Interim Estimates of 2023–24 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness — United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronski, D.M.; Zhan, Y.; Kaweski, S.E.; Sabaiduc, S.; Khalid, A.; Olsha, R.; Carazo, S.; Dickinson, J.A.; Mather, R.G.; Charest, H.; et al. 2023/24 Mid-Season Influenza and Omicron XBB.1.5 Vaccine Effectiveness Estimates from the Canadian Sentinel Practitioner Surveillance Network (SPSN). Eurosurveillance 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blyth, C.C.; Macartney, K.K.; McRae, J.; Clark, J.E.; Marshall, H.S.; Buttery, J.; Francis, J.R.; Kotsimbos, T.; Kelly, P.M.; Cheng, A.C.; et al. Influenza Epidemiology, Vaccine Coverage and Vaccine Effectiveness in Children Admitted to Sentinel Australian Hospitals in 2017: Results from the PAEDS-FluCAN Collaboration. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019, 68, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Influenza Center. National Influenza Surveillance Technical Guidelines (2017 Edition); National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://ivdc.chinacdc.cn/cnic/fascc/201802/P020180202290930853917.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. Recommended Composition of Influenza Virus Vaccines for Use in the 2024-2025 Northern Hemisphere Influenza Season . Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/who-influenza-recommendations/vcm-northern-hemisphere-recommendation-2024-2025/recommended-composition-of-influenza-virus-vaccines-for-use-in-the-2024-2025-northern-hemisphere-influenza-season.pdf?sfvrsn=2e9d2194_7&download=true (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG). Influenza Vaccination TWG Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023-2024). Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 44, 1507–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2022–2023 Influenza Season . Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/coverage-by-season/2022-2023.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Yang, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, T.; Long, J.; Xiong, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Tang, W.; et al. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccine among the Population in Chongqing, China, 2018–2022: A Test Negative Design-Based Evaluation. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2024, 20, 2376821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, H.; Niu, B.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Che, X.; Du, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness against Medically-Attended Influenza Infection in 2023/24 Season in Hangzhou, China. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2025, 21, 2435156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissling, E.; Maurel, M.; Emborg, H.-D.; Whitaker, H.; McMenamin, J.; Howard, J.; Trebbien, R.; Watson, C.; Findlay, B.; Pozo, F.; et al. Interim 2022/23 Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: Six European Studies, October 2022 to January 2023. Eurosurveillance 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Godoy, P.; Torner, N. The Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination in Different Groups. Expert Review of Vaccines 2016, 15, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-ping, Y.; Wan-qing, ZHANG. CHEN Li-ling Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness among Children, 2011 – 2021: A Testnegative Design-Based Evaluation. Chinese Journal of Public Health 2022, 38, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.Y.; Zhu, J.L.; Lyu, M.Z.; Hu, Y.Q.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, G.M.; Chen, G.S.; Wu, X.H. Evaluation of the influenza vaccine effectiveness among children aged 6 to 72 months based on the test-negative case control study design. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2019, 53, 576–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnich, A.; Arata, L.; Amicizia, D.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Gasparini, R.; Panatto, D. Effectiveness of MF59-Adjuvanted Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccine 2017, 35, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Xue, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, T.; Du, W.; Chen, T.; Miao, H.; Qin, Y.; et al. Characterization of Influenza Seasonality in China, 2010–2018: Implications for Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Timing. Influenza Resp Viruses 2022, 16, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) Technical Working Group (TWG). Influenza Vaccination TWG Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023-2024). Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 2023, 44, 1507–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belongia, E.A.; Skowronski, D.M.; McLean, H.Q.; Chambers, C.; Sundaram, M.E.; De Serres, G. Repeated Annual Influenza Vaccination and Vaccine Effectiveness: Review of Evidence. Expert Review of Vaccines 2017, 16, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |