1. Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, education worldwide turned toward hybrid education, altering pedagogical approaches such as school curriculum, assessment methods, and classroom management, just to name a few [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In the early days of this pandemic, most academic research concentrated on how to respond to this outbreak. There was and still is a significant gap in how this shift to hybrid education and its novel approaches can be maintained to guarantee the continuity of formal learning in situations like this [

5,

6,

7], especially in developing countries such as Liberia. This is directly linked to the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4), which advocates for inclusive learning, access to high-quality education, and opportunities for lifelong learning [

8,

9,

10,

11]. In situations like this, insufficient preparation of teachers, the unavailability of digital devices, and low internet provision are mostly noticed [

6,

10,

12]. These are for sure significant issues that can pop up in emerging economies such as Liberia. These are all visible factors that can greatly influence the implementation of classroom management skills in a hybrid setting.

Students and teachers work in a classroom to improve the students' academic performance. Elements such as good classroom management and a good learning environment contribute remarkably to the students' academic success [

13,

14], but good classroom management is paramount [

15,

16]. Classroom management is a structured and planned approach employed by educators to foster the development and establishment of a conducive learning environment, enabling pupils to acquire diverse knowledge and skills effectively [

14,

17]. The complexity and variety of events in classrooms create management challenges [

18]. This position of classroom management is, therefore, a fundamental notion that influences education and serves as a crucial foundation for educational success [

19]; thus, critical key to the success of the SDG4, "quality education for all".

1.1. The Problem Statement

The educational setting has changed significantly since COVID-19 [

20,

21,

22], and hybrid learning educational models are becoming more and more widespread worldwide [

23,

24].

The shift has led to a global trend in education that emphasizes contingent planning, ensuring the continuity of learning in times of outbreaks and disasters. Information on the sustainability of this shift to hybrid classroom management is necessary. Many papers have been published on the sustainability of this shift in developed countries; meanwhile, in developing countries like Liberia, few studies focused on the early transition to radio teaching, online, and hybrid education at the peak of the pandemic, fewer were done on assessing the sustainability of the shift to hybrid classroom management practices. This indicates the limited information on the ongoing educational discussion regarding SDG4, in the context of sustaining the shift to hybrid classroom management in Liberia following the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thus, the researcher decided to scrutinize SDG 4 (Quality Education) by assessing the sustainability of the shift to hybrid classroom management post-COVID-19 from the viewpoint of junior and high school instructors in Liberia. By examining the practical competencies and the practical realities of these junior and high school teachers in Liberia, this study fills this knowledge gap by providing some information to the Liberian Ministry of Education, Liberian lawmakers, contributing to the global literature on how this new model in resource-constrained countries, and adds to the current discussion on SDG, particularly in emerging economic nations like Liberia, by concentrating on the lived experiences of the teachers on the ground. It also offers distinctive practical insight into what is required for sustaining the advances in education acquired during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Aim

The goal of this study is to assess the extent to which Liberian junior and high school teachers have sustained their hybrid classroom management competencies post-COVID-19.

Objective 1. To identify the main obstacles in sustaining the shift to hybrid classroom management.

Objective 2. To understand the instructor's viewpoint regarding the significance of sustaining the shift.

Objective 3. To develop workable recommendations to improve on sustaining Liberia's transition to hybrid classroom management.

1.3. Research Question (R.Q.)

To what extent have the educators in Liberian junior and high schools sustained the use of hybrid classroom management skills developed during the pandemic?

Specific research question one. What are the main obstacles in sustaining the shift to hybrid classroom management?

Specific research question two. What are the significance of sustaining the shift from the viewpoint of the instructors?

Specific research question three. What are the workable recommendations to improve on sustaining Liberia's teachers' transition to hybrid classroom management?

2. Literature Review

To situate this paper within the current discussion on SDG4 and education in general, this literature review examines three main topics: the global shift occurring in education, the complexity in educators' competencies in classroom management in a hybrid scenario, and the particular difficulties faced by developing countries in achieving the sustainability of this global educational shift. Some of the theories relating to pedagogy that impact classroom management as well are reviewed.

2.1. The Global Shift Occurring in Education

Schools had to make unfamiliar adjustments to their curricula as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which sped up the world's shift to online and hybrid learning [

25]. Some researchers demonstrated that this shift to hybrid learning was a worldwide phenomenon that necessitated a long-term [

26] well-supported implementation [

21], rather than a band-aid solution [

27]. At the start, more research concentrated on a quick solution to this shift [

5]. Since then, a substantial knowledge gap has remained regarding the enduring sustainability of these novel techniques, particularly in the context of resource-constrained countries [

10,

28]. Instead of relying on reactive programs to counteract unseen situations, it seems difficult to develop reliable fixed systems of education to address such situations [

29]

This relates to Sustainable Development Goal 4, which deals with equitable education for all, specifically relating to this discussion of lifelong learning [

8]. From this viewpoint, incorporating technology into education will assist in attaining the SDG4 goals [

30,

31], but this faces systemic barriers such as limited access to the internet, a shortage of digital infrastructure, and inadequate teachers' training [

32]. This showed that, to sustain the shift after COVID-19, providing technology that can improve the standard and quality of education can aid in meeting SDG4 in developing countries [

30,

33].

2.2. Educators' Competencies in Hybrid Scenario Classroom Management

Many factors contribute to students’ success, but good classroom management has been pinpointed as being very significant [

14,

34]. A supportive and student-centered environment, which is the strategy used in this era, has countered the strict discipline, traditional theories of classroom management.

The dynamic classroom management approach (DCMA), which integrates creative, culturally responsive techniques to create a supportive learning environment, embodied this change [

35].

However, these ideas now have an additional level of complexity due to the introduction of hybrid education. Educators now manage both face-to-face and online classrooms, which requires a new set of skills. Teachers need skills in critical areas of hybrid classroom management, such as developing a good and positive relationship between learners in both physical and digital settings, upholding discipline in online and hybrid environments, and creating instructional activities that work no matter where the learners are located [

36,

37,

38]. According to [

39], learners’ academic results are directly correlated with educators’ capacities to develop skills to handle these challenges; therefore, for hybrid learning to be successful, it is essential to apply these skills practically.

2.3. Hybrid Educational Sustainability Difficulties in Emerging Economies

While many developed countries had the necessary infrastructure to shift to online and hybrid education [

40], emerging economic nations had faced major preexisting obstacles that were made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic and hindered their smooth shift [

33,

41].

According to [

42,

43] the digital divide was the main barrier to educational equity and sustainability in this context. The viability of the hybrid approach was also hampered by recurring problems like nonexistence or erratic access to the internet, a remarkable shortage of digital gadgets for educators as well as learners, and an unstable source of power supply [

44]. Due to these deficiencies, even the most creative teaching strategies became unfeasible [

36]. Liberia is one of the emerging economic nations that has had this situation. Liberia had a long tradition of civil conflicts and Ebola epidemics, and has been actively reconstructing its system of education [

45] when the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced in 2020. Due to this, the transition to online and hybrid education faced some challenges [

46].

The sustainability of this shift remains a major concern in Liberia, despite national and international initiatives like the improved results in the Secondary Education (IRIES) project [

47]. Although some studies have examined online education in Liberia during the pandemic, there is a clear and significant gap in the literature regarding the shift’s sustainability, especially concerning educators' actual daily hybrid classroom management routines.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

The theories discussed in this study are linked to pedagogy, which is connected to the classroom management domains. Instructors employ a variety of techniques in hybrid classroom management, including teaching and learning theories from both traditional and online classroom management [

4]. Among other things, it encompasses the application of skills in the disciplinary domain, the teaching and learning domain, and the relationships domain. A positive learning environment can be created by generating skills that will motivate pupils to learn, fostering positive relationships between teachers and students, and lowering classroom disorder [

48,

49,

50].

2.4.1. Theory of Connectivism in Learning

Connectivism is one of the newest theories of educational learning. Connectivism was first put forth by theorists George Siemens and Stephen Downes in 2005. Siemens released Connectivism: Learning as a Network Creation online in 2004, and Downes introduced An Introduction to Connective Knowledge the following year [

51,

52]. It is based on the idea that connections help people grow and learn. These could be interpersonal relationships or their obligations and duties in life. Hobbies, aspirations, and interpersonal relationships can all have an impact on learning. In this technological age, technology has made it easier for students to engage with one another and with instructors [

51]. To encourage students to learn, they can assist in establishing alliances and interactions with both their educators and the learner-peer networks as well [

53].

Due to technological advances, both the educational and economic sectors have experienced an increase in connectivity. Connectivity is crucial in a hybrid classroom because it helps learners as well as educators acquire the technological skills necessary to evaluate the vast amount of online material [

54,

55].

2.4.2. The Theory of Cognitive Learning

It examines human thought processes, which are crucial to understanding how we learn [

56]. External as well as internal factors can have an impact on learners, according to cognitive theory [

57]. Suriano et al. (2025) postulated that learners can exert greater control over their thought processes as they become more aware of how their thinking influences their behavior and learning.

Two of the earliest philosophers to concentrate on cognition and human thought processes were Plato and Descartes [

59]. Additional investigation was sparked by the numerous additional investigators who dug deeper into the concept of how we think, such as Jean Piaget's research, which focused on inner processes and settings, then how they affect learning. Teachers can give learners the chance to fail, ask questions, and think out loud. By employing these strategies, students can gain a deeper understanding of how their minds work and apply that knowledge to develop more productive learning opportunities [

60].

2.4.3. Theory of Humanism in Education

The humanistic learning theory was introduced by Carl Rogers, James F. T. Bugental, and Abraham Maslow in the early 1900s. Humanism was in relation to psychoanalysis and behaviorism, which were the renounced educational theories at the time [

61]. Constructivism and humanism are intimately related [

62]. Developing oneself is a central concept in humanism [

63]. A hierarchy of requirements governs how everyone functions. The brief moments when a person believes that all of their desires have been met and that they are considered the most successful human being themselves are at the top of the hierarchy of requirements. This is known as personal development. Instructional settings can either move closer or further from addressing demands, and this is what everyone is aiming for [

64].

Instructors can design learning spaces that support learners in being more self-actualized. Different learning styles can be used by teachers to reach a variety of learners, giving rise to lessons that are especially adapted to the needs and skills of every student [

65].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

The study used a phenomenological hermeneutic design. Instead of only retelling events, the phenomenological hermeneutic design looked at understanding and characterizing first-hand human lived experience of participants in a particular phenomenon, by also taking into account the unseen meaning behind their stories in their real and natural settings [

66,

67,

68] The phenomenon of this study was Liberian high school and junior school teachers' perceptions of the sustainability of the transition to hybrid classroom management after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Applying the hermeneutic approach, the researcher was able to decipher the emotions, memories, and hidden meanings of the teachers' stories by taking into account certain aspects of the study's background, such as their culture, their present education policies, and their economic resources [

67,

69,

70]. This phenomenological hermeneutic approach involved the researcher maintaining a strong commitment to the educators, the data collection, and the data analysis phases, establishing the investigation's consistency and real-world experiences [

68].

3.2. Participants and Sampling

To recruit participants for this study, the researcher located the schools using community information. The positions of these schools were determined in November 2024. In the month of January 2025, 23 schools were approached with the ethical approval letter from the researcher’s university (See Supplementary Material S1. University ethical approval letter), and all granted their permission (See Supplementary Material S2. Liberia`s junior and high schools permission letter). The researcher moved ahead to recruit the participants.

Qualitative studies select study participants using special techniques [

71,

72]. The main objective of these techniques is to recruit participants who have a thorough background understanding of the phenomenon under investigation [

72,

73].

Purposive sampling, which enables participants who can offer the most pertinent and perceptive information on the research issue to be chosen, was used in this study [

74,

75]. The criteria used to admit participants to this study were: junior and high school teachers in the Montserrado County metropolitan area of Liberia who were currently employed at the time of the study and had teaching experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. These criteria were used to obtain firsthand knowledge of the sustainability of the shift to the hybrid model following the pandemic.

The researcher organized meetings in the various schools in collaboration with their principals to brief the teachers, seek their consent, and recruit participants for the study. Since the public schools required a lot of time for bureaucracy and clearance from District authorities, which was time-consuming in relation to the researcher's time-frame for completing the PhD degree, all the participants were from private schools. Some of the factors that influenced the decision of how many participants were needed in the study were: time and resource availability, the research focus, institutional approval requirements, the nature of the research question, the investigator's previous experience with qualitative research, and the domain of investigation [

76]. Two participants were chosen from each school; 12 participants came from the junior high, while 14 came from the high school, for a total of 26 participants. This was consistent with [

76] research paper on the required number of participants in a qualitative study, which suggested 20–60 participants. This improved the study's credibility and dependability. The solicited volunteer teachers gave their phone numbers as consent to participate in this study and to ensure easy communication.

Descriptive statistics were employed for the demographic questions in Section A to present the frequencies (n) and percentages (%) of the demographic entities of the participants. Data on every participant cannot be reported in the majority of research investigations. By giving a summary of the key features of the sample, descriptive statistics explain and condense the data [

83].

Examining the demographic questions helps present the caliber of teachers who participated in this study. This was made visible by generating the tables and the figures below from the Excel sheet.

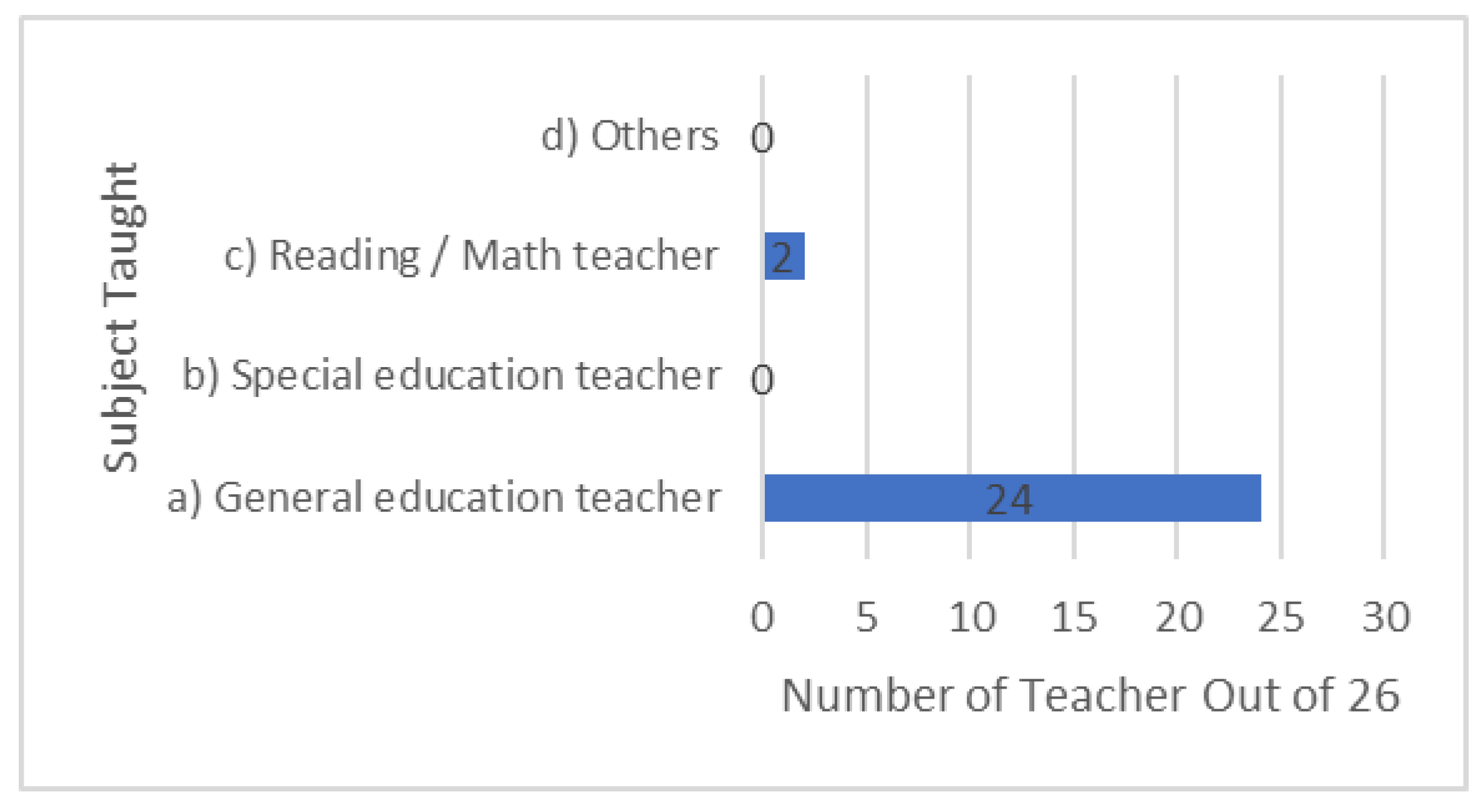

3.2.1. Demographic Question 1 (DQ1). What Is Your Role on Campus?

The role of the teachers was essential for this research.

Table 1. Below presents the percentage and frequencies of the subjects taught by the teachers who took part in the research.

The information from

Table 1 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart for clear comprehension, as shown in

Figure 1 below.

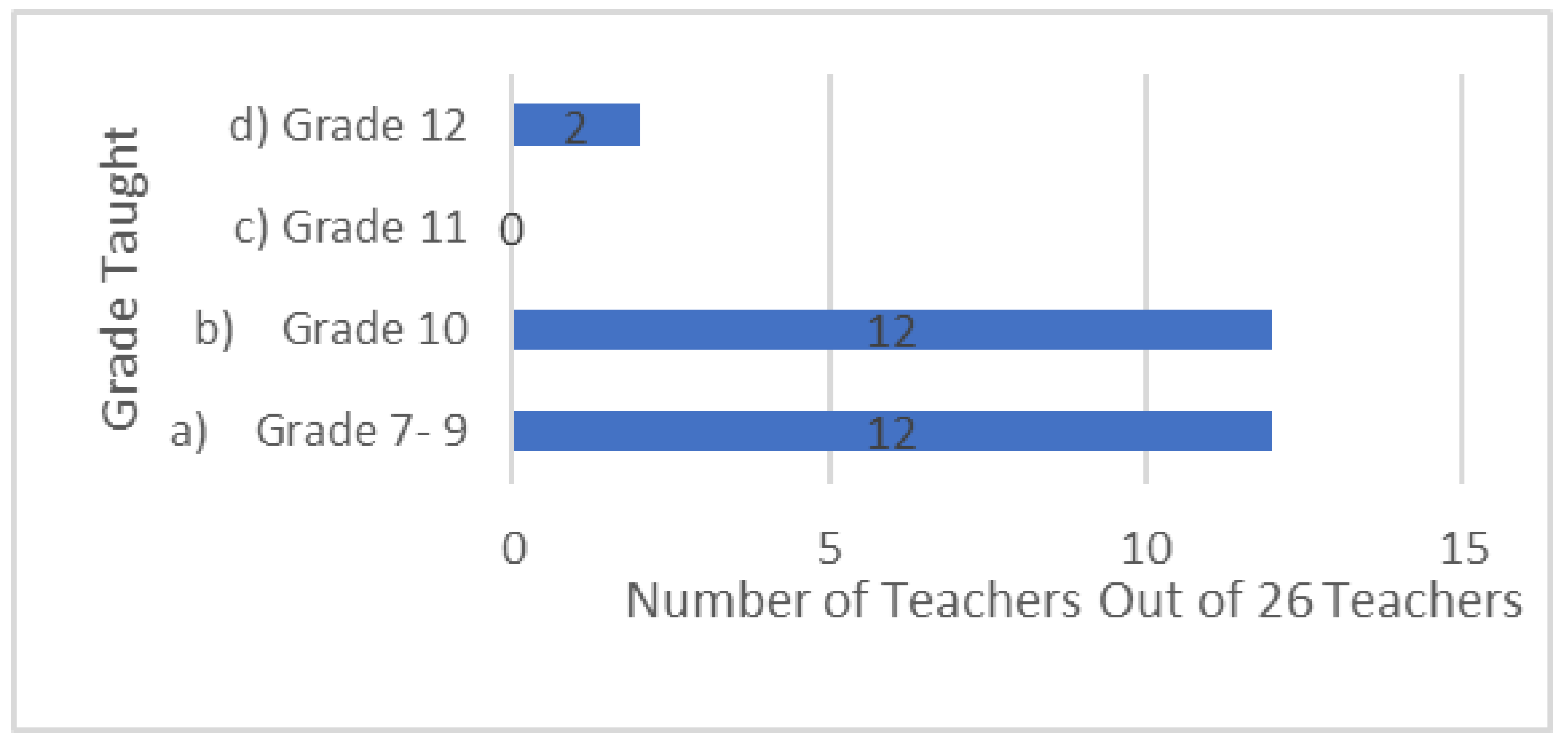

3.2.2. Demographic Question 2 (DQ2). What Grade Do You Teach?

Table 2 below indicates the various grades in which the participants taught during the time of this research.

This information from

Table 2 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart for clear comprehension, as shown in

Figure 2 below.

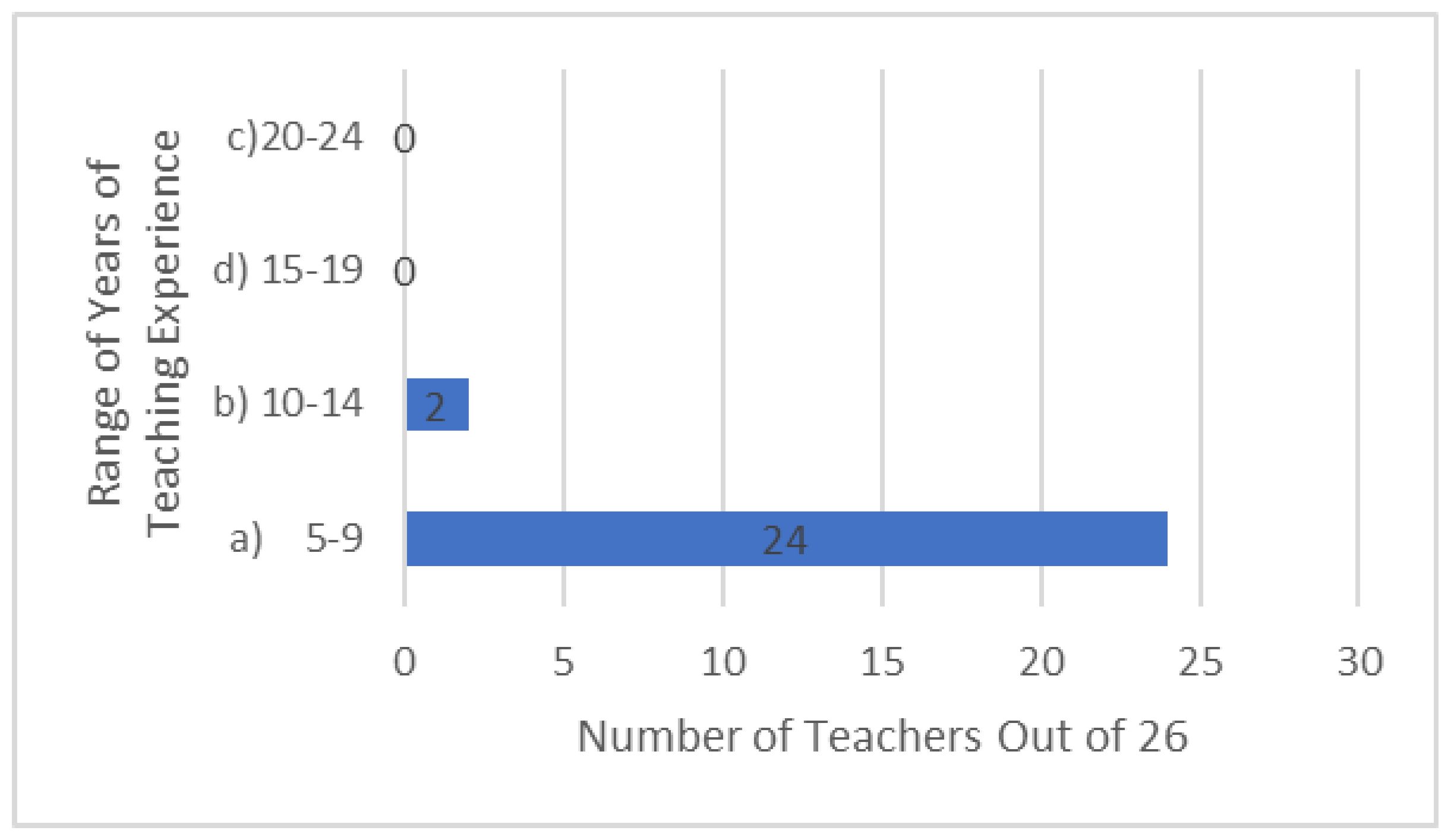

3.2.3. Demographic Question 3 (DQ3). How Many Years of Teaching Experience Do You Have?

Demographic question 3 demanded the years of teaching experience.

Table 3 below presents the frequency and percentage of the years of experience of the teachers who took part in this research.

The information from

Table 3 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart for clear comprehension and visibility, as shown in

Figure 3 below.

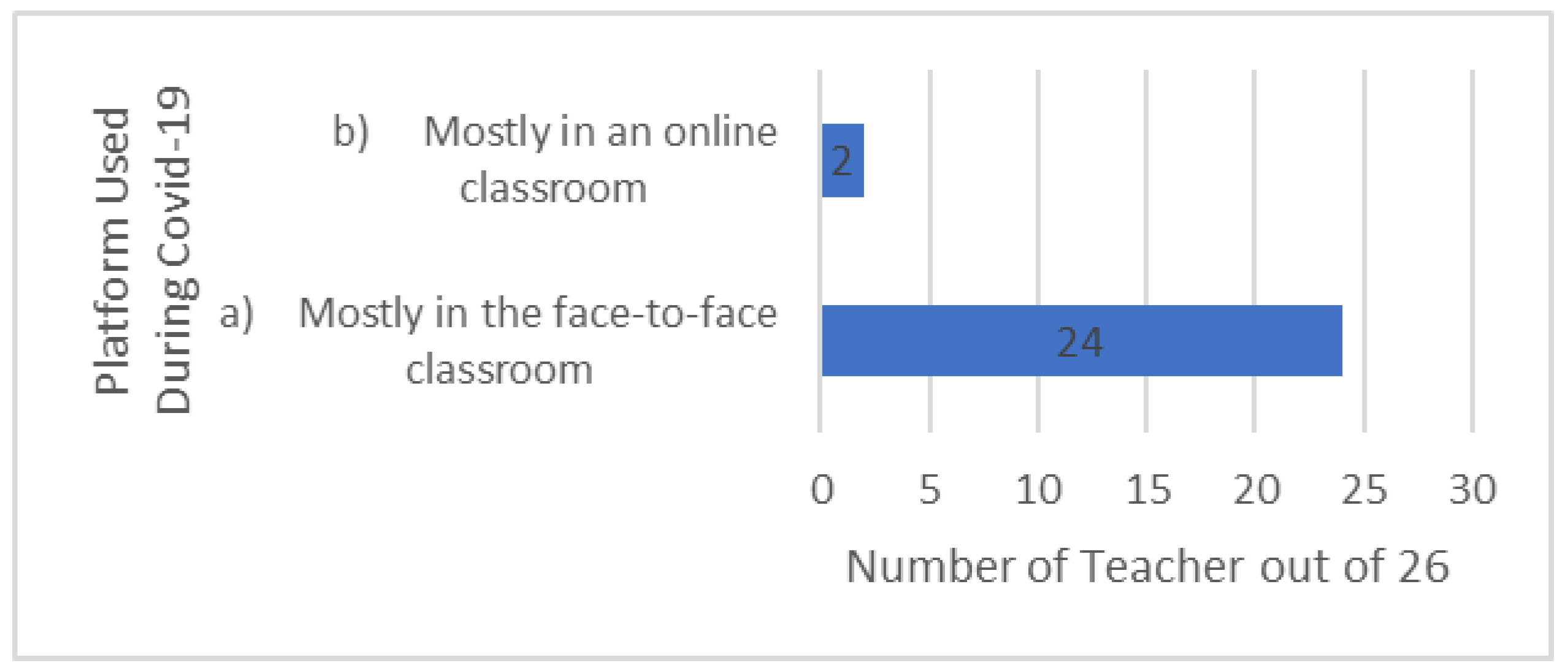

3.2.4. Demographic Question 4 (DQ4). Which Platform (For Example, Google Classroom, Moodle, Zoom, Radio) Did You Utilize Most for Online Teaching During the Pandemic?

This demographic question was to evaluate the platform used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 4 below presents the frequency and the percentage distribution of the platforms used during the pandemic by the teachers who participated.

The information from

Table 4 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart for clear comprehension, as shown in

Figure 4 below.

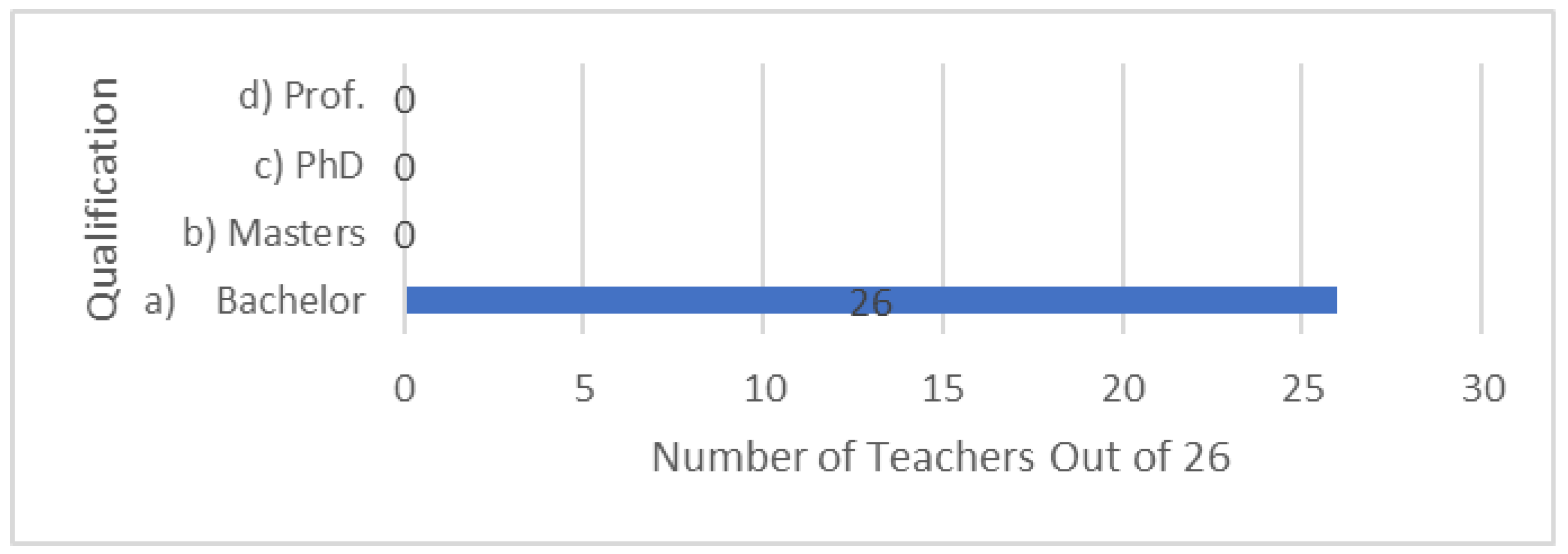

3.2.5. Demographic Question 5 (DQ5). What Is Your Highest Level of Formal Education Achieved?

The level of education was essential for this research as well.

Table 5 below shows the frequency and percentage of the level of education of the participants.

The information from

Table 5 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart to ease the comprehension of the data, as shown in

Figure 5 below.

From the demographic section of this paper, most participants were general education teachers who primarily taught in grades 7-9 and grade 10. All held a Bachelor's degree, indicating they possessed some pedagogical knowledge related to the concept under investigation. Most teachers who taught during the COVID-19 pandemic had between 5 to 9 years of experience. Despite teaching during the pandemic, they mostly used face-to-face classrooms, suggesting that in Liberia, many schools adhered to social distancing guidelines and continued with in-person learning, as in most developing countries [

86]. These are the types of teachers who responded to section B (questions related to the topic under investigation).

3.3. Data Collection and Instrumentation

Using the interview guide (See Supplementary Material S3. Interview guide), the researcher obtained rich qualitative data for the study [

77]. The semi-structured interview question guide was developed with some information obtained from the literature review, framed in line with the framework for qualitative semi-structured interview guide provided by Kallio et al., 2016 [

78], and was cross-checked by five lecturers in the department of education at the researcher's university, with the two supervisors included. This guide assisted the researcher in getting the participants' experiences on the concept under investigation [

77]. This was made up of two sections: five questions for the demographic section A, and 4 questions relating to the concept under investigation section B. The interview was conducted from February to April 2025.

The phone numbers that were provided voluntarily by the participants during the briefing meetings were used to arrange and confirm the day, venue, and time of the interview. The interview locations were arranged at their various school early before lessons in their principal's offices. This time and venue were arranged in collaboration with their principals for a quiet and fresh memory of the teachers at that early hour of the day. A duration of about 69 minutes on average was taken for each interview. The researcher was very attentive to the participants' explanations to get their ideas on the concept under investigation and wrote them down accordingly to establish their respective responses [

79]. After the collection, the researcher finalized the responses and read them to the participants for confirmation to ensure the credibility of the data collected. This inline increased the credibility of the study.

3.4. Data Analysis

The data collected was analyzed under the broad approach of the hermeneutic phenomenological method to deeply interpret the thoughts and feelings of the lived experiences of the participants.

The Reflective Thematic Analysis (RTA) was used to analyze the data collected in section B, following the framework presented by Braun and Clarke [

80]. Unlike deductive thematic analysis, where the researcher seeks to maintain rigor by applying fixed, pre-defined codes [

81,

82], RTA breaks down and brings out in-depth meaning from the data collected in line with the participants' lived experiences of the phenomenon under investigation [

80]. This framework was essential for the researcher to align the systematic process of data analysis with the interpretive philosophy of the design. It permitted the researcher to first look at the participants' responses carefully, identify and pinpoint important ideas or patterns, giving rise to themes. Smaller details that fit under these themes were identified, giving rise to sub-themes and subsequently the respective codes [

80]. After this, the hermeneutic concept of interpretation was employed to understand the fundamental truth and clear meaning of the participants' of RTA served as a methodological bridge.

The framework of Braun and Clarke, respecting the six-step process, was strictly followed by the researcher.

Familiarization. The researcher read the responses of the teachers several times to understand their lived experiences.

Generating initial codes. The researcher identified and systematically labelled key ideas or phrases (codes) of the responses to the various interview questions.

Searching for themes and sub-themes. The researcher gathered coherent patterns of codes with similar meaning to generate sub-themes. These sub-themes were later coherently grouped together, respecting the patterns of occurrence with similar meaning to generate themes.

Reviewing the themes. To ensure some accuracy, the researcher cross-checked the themes against their sub-themes, codes, and the entire set of data, respecting their boundaries to ensure they are perfectly fit in their various groups.

Naming and defining. The names of the themes and sub-themes were clearly defined to represent the story of the lived experiences of the teachers.

Report production. Lastly, the researcher analyzed the ideas behind groupings interpretive, generating a reflexive report supported by the teachers' quotes for better comprehension.

The analytic phase of the study went from May to August 2025. The researcher was unable to use qualitative analysis software applications like NVivo due to the weak, sporadic internet and power supply in Liberia at the time of this study, which constantly disrupted the installation, and it was time-consuming. To instill reliability, rigor, and transparency in the analysis, the researcher used the manual traditional method, complemented by Microsoft Excel, data management, and visualization.

In the first phase, the application of Braun and Clarke was employed. In the second phase, the researcher transferred the information into an Excel sheet to produce the frequency, percentage tables, and horizontal column charts to improve the visibility, interpretation, and comprehension of the data collected. A final table was created, including themes, sub-themes, codes, their frequencies, and the corresponding responses (See Supplementary Table,

Table S1. Table of Themes, sub-themes, codes, frequencies, and corresponding responses). From this table, individual frequency and percentage tables, and horizontal column charts were established for the various demographic and interview questions.

3.5. The Research Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness of this research was established by incorporating the criteria of Lincoln and Guba [

84,

85]. These criteria included dependability, confirmability, and transferability, which are basically for qualitative work.

Dependability. The dependability of this research was ensured by the detailed documentation of the study. The researcher clearly stated in the methodical RTA how the data were collected, how the codes, sub-themes, and themes were developed.

Confirmability. The researcher acknowledged the interpretive role by employing the reflexivity practice and deriving the findings systematically and logically from the data (See Supplementary Table ST1. Table of Themes, sub-themes, codes, frequencies, and corresponding responses), free from bias.

Transferability. Finally, the researcher ensured transferability of the research by presenting the process in a thick description to allow the application of the same research by other researchers in the future.

4. Results

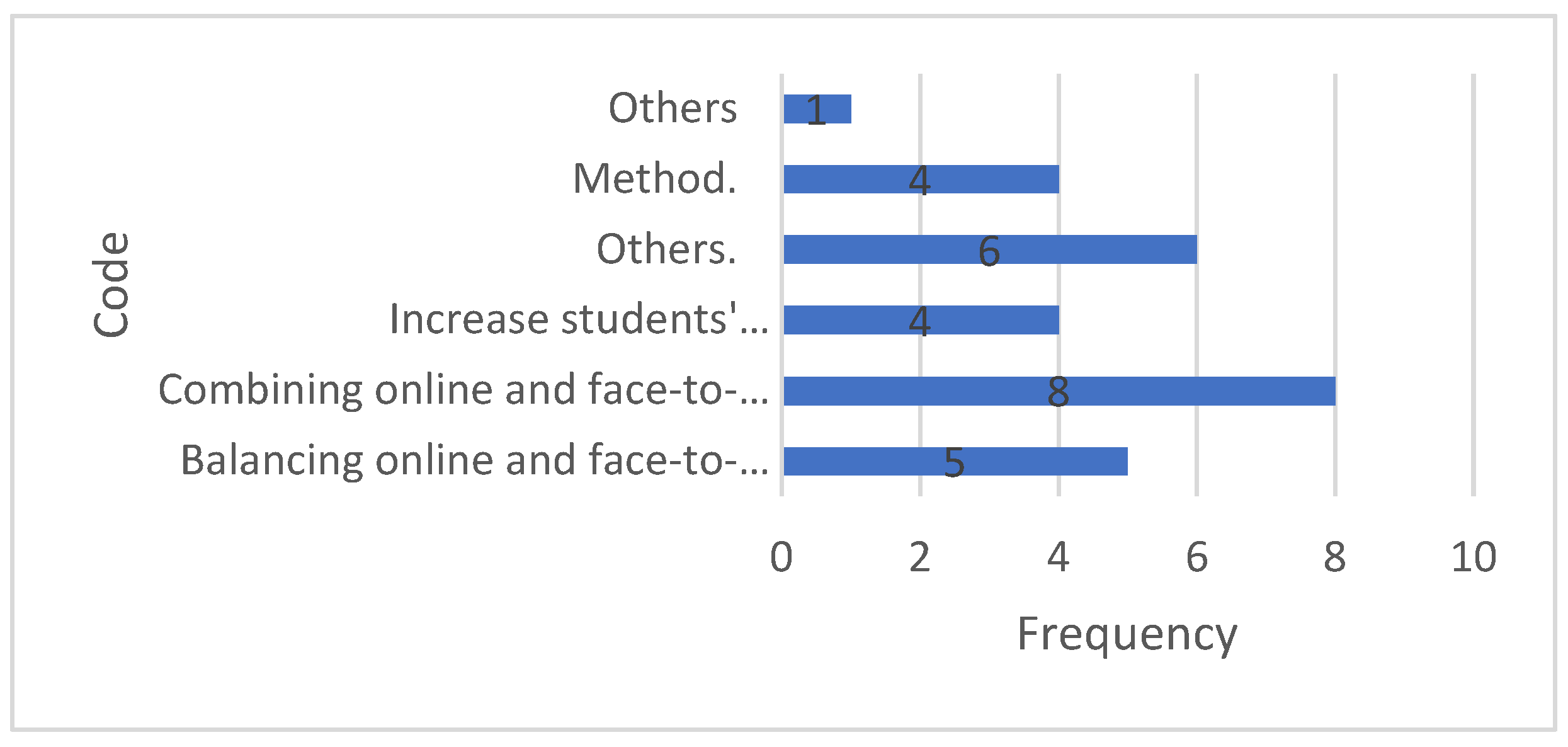

4.1. Interview Question (IQ.1). What Is Hybrid Classroom Management?

This interview question was posed to understand how the teachers who participated in this research understood the concept of hybrid classroom management. This was essential for the researcher to assess the sustainability of HCRM as it provided the foundation of their responses. From their responses, it was clear that the teachers understood the concept of HCRM. The frequencies and percentages of the codes generated are presented in

Table 6 below.

The information from

Table 6 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart to ease the comprehension of the data, as shown in

Figure 6 below.

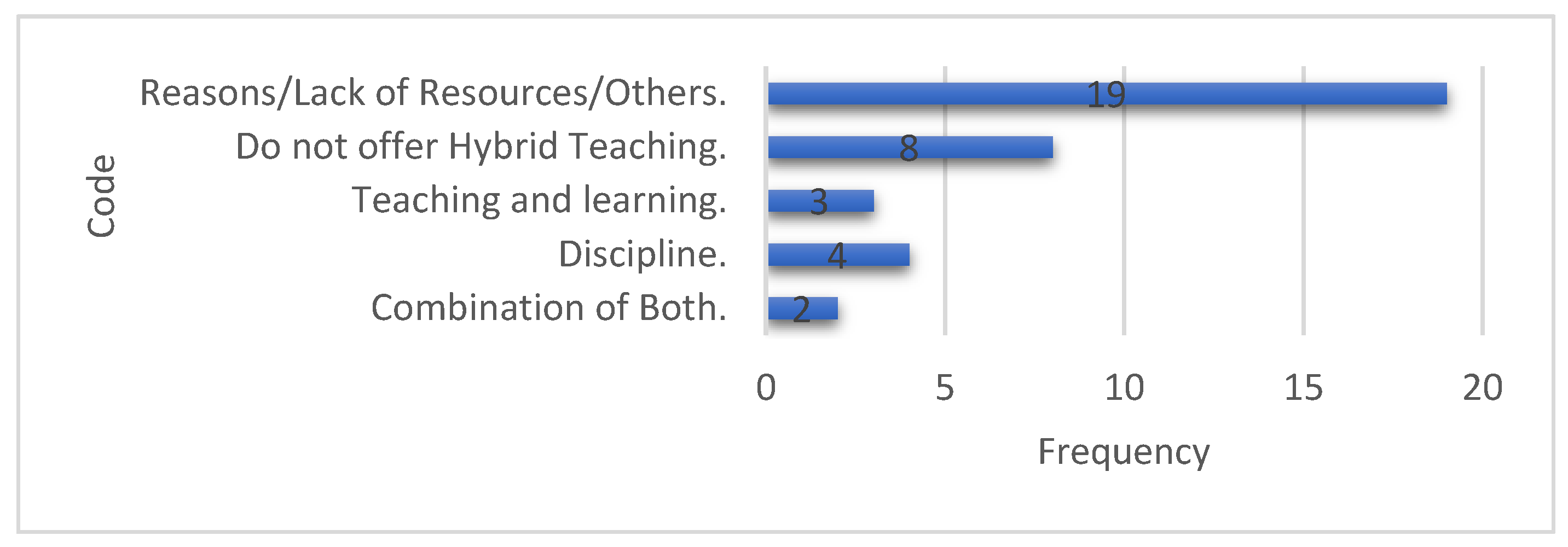

4.2. Interview Question (IQ.2). How Do You Conceptualize Your Success in Hybrid Classroom Management?

This interview question was posed to understand how the teachers who participated in this research conceptualized hybrid classroom management success. This was a remarkable question to assess the sustainability of the shift to HCRM. The analysis of this question brought to light a significant implementation gap, which directed the responses to the core objective of this work. The frequencies and percentages of the codes generated are presented in

Table 7 below.

The information from

Table 7 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart to ease the comprehension of the data, as shown in

Figure 7 below.

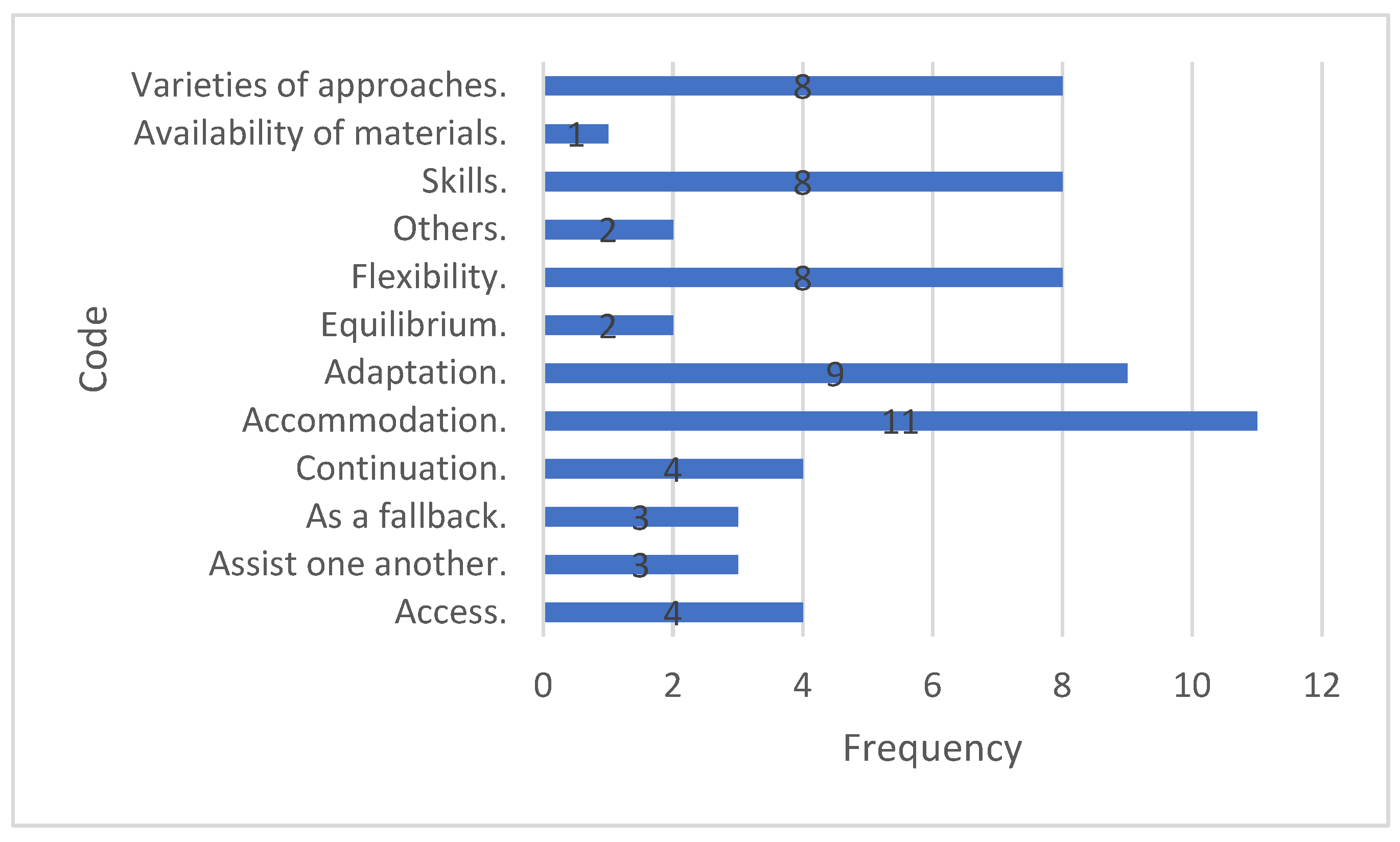

4.3. Interview Question (IQ.3). From Your Own Point of View, What Are Some of the important Aspects of Hybrid Education?

This interview question was posed to understand how the teachers conceptualized the importance of hybrid education. It was found that the teachers strongly acknowledged the potential of hybrid education in sustaining learning. The frequencies and percentages of the codes generated are presented in

Table 8 below.

The information from

Table 8 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart to ease the comprehension of the data, as shown in

Figure 8 below.

4.4. Interview Question (IQ.4). Can You Give Some Suggestions on How to Improve Hybrid Classroom Management Sustainability in Your School and Liberia as a Whole?

This interview question, number 4, was the final question posed to gather suggestions on how the sustainability of HCRM can be improved in Liberia's junior and high schools. The frequencies and percentages of the codes generated are presented in

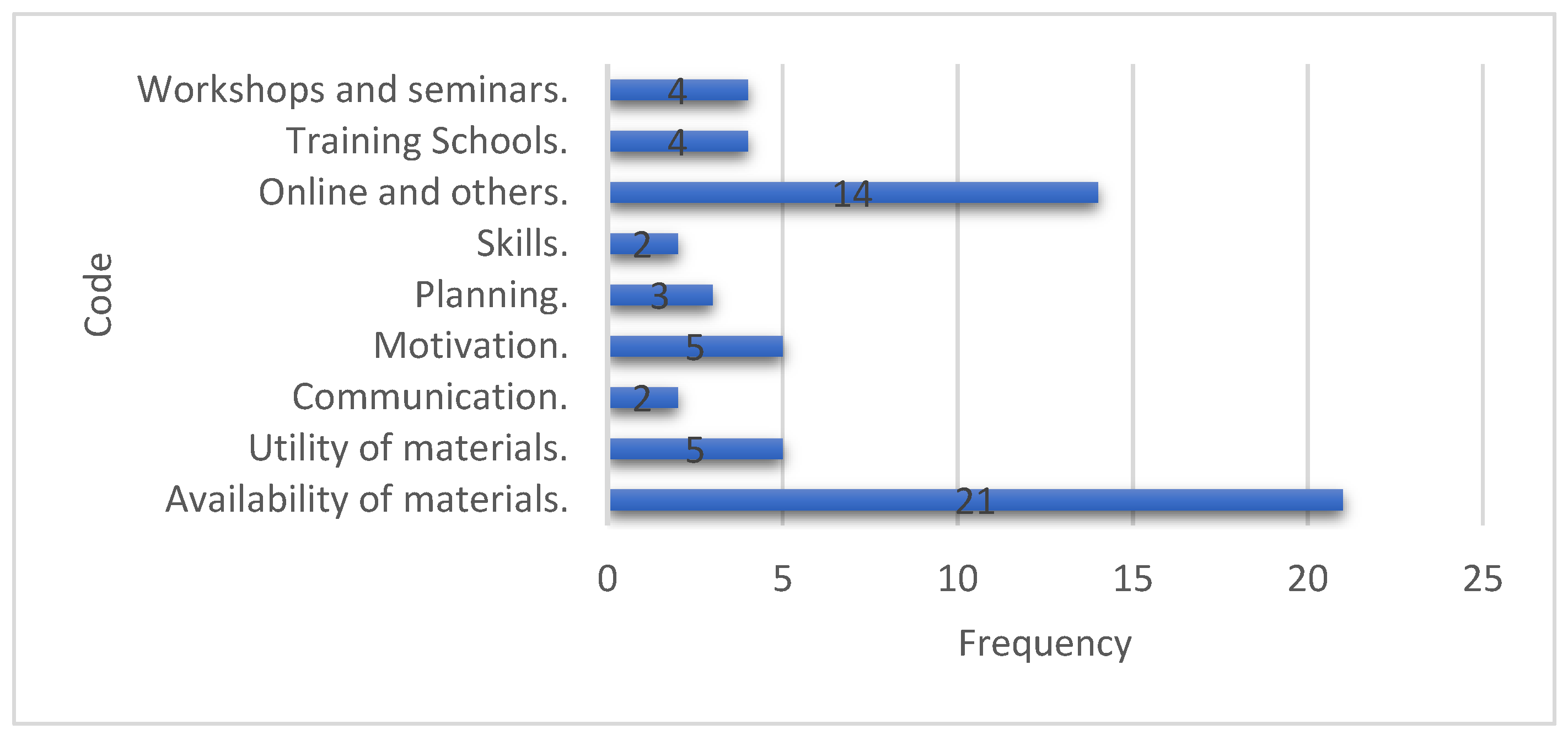

Table 9 below.

The information from

Table 9 above was introduced into the Excel sheet to generate the frequency column chart to ease the comprehension of the data, as shown in

Figure 9 below.

5. Discussion

5.1. IQ1. What Is Hybrid Classroom Management?

The purpose of this interview question was to find out how the teachers who took part in the study perceived the concepts of hybrid classroom management. Since it served as the basis for their understanding of the concept under investigation, this was crucial for the researcher to evaluate the sustainability of HCRM. It was evident from their answers that the teachers comprehended the concepts of HCRM.

5.1.1. The Conceptualization of HCRM

According to

Table 6 and

Figure 6 above, it was noticed that from the responses of the teachers, the sub-theme “combining and balancing online and face-to-face skills” had the highest frequency, n = 13 (46.43%), which revealed that the teachers understood HCRM as a technical synthesis of the two distinct skills. The code “combining online and face-to-face skills” with a high frequency of n = 8 (28.57%) represented the most cited. This showed that the teachers understood HCRM as integrating both face-to-face and online CRM skills [

23,

87]. This view aligns with the idea of this special issue, which explores innovative teaching as a novel method of CRM that diverges from traditional CRM to develop a new pedagogical skill in a hybrid setting.

P14: “HCRM is using both online and face-to-face CRM methods simultaneously.”

P25: “HCRM is using the CRM skills of online and in-person to assist student in understanding their lessons in both settings.”

The code “balancing online and face-to-face skills” was also significant in the teachers' responses, with a frequency of n = 5 (17.86%). The high frequency of this code also indicated that the participants understood the importance of harmonizing the two learning environments while respecting their unique identities. The concept of balancing is significant for the sustainability of the shift, as perpetual usage of one setting signifies the lack of sustainability.

P4: “HCRM is when a teacher successfully balances online and face-to-face CRM skills in handling a hybrid setting.”

5.1.2. Linking the Pedagogical Practice to SDG4

The presence of the code “increase students’ comprehension” with a frequency of n = 4 (14.29%) of the sub-theme “Increase comprehension” showed that the participants linked the HCRM concept directly with the quality education aspect of the SDG4. The understanding of the sustainability of the HCRM skills of the participants was not solely technical but also student-centered, as they could conceptualize the HCRM pedagogical approach to the improvement of students’ academic performance across the various settings.

Since the teachers who participated in this study had a sound knowledge of sustainable HCRM, it was evident that their contributions can be upheld for the advancement of sustainable education in Liberia. This is paramount when exploring their recommendations on sustaining the HCRM competencies.

5.2. IQ2. How Do You Conceptualize Your Success in Hybrid Classroom Management?

The purpose of this interview question was to find out how the research participants perceived the success of hybrid classroom management. This was an excellent question to evaluate how successful the sustainability HCRM was. This question's examination revealed a substantial implementation gap, which guided the answers to this work's main goal.

5.2.1. The Absence of HCRM Practices

The findings brought to light the major barrier to the sustainability of the shift to HCRM. The majority of teachers did not have the chance to teach in a hybrid setting, and they could not address success in hybrid classroom management. As shown in

Figure 7 and

Table 7, some participants highlighted the abilities required for successful hybrid classroom management. The findings were essential to the investigation's central concept. The most prevalent sub-theme, "Do not offer hybrid teaching and Reasons," with a frequency of n = 27 (75.00%), indicated a significant and widespread problem: the majority of participating institutions did not institutionally embrace a developed hybrid model, as reported by P2, and P4.

These results suggested that although instructors had a conceptual knowledge of what HCRM was, as presented in the interview question one above (4.2.1), they had not been given the opportunity to put such understandings into practice in most of the schools, due to the failure of the institutional structure. This directly influenced the heart of the research on sustaining the shift, as it indicated that the transition has not been fully implemented at most school levels.

P2: “I do not offer Hybrid education because of a lack of gadgets to conduct online classes.”

P4: “I do not offer online teaching due to a lack of infrastructure to accommodate this system.”

This result was consistent with studies on the use of instructional technology in developing nations. According to a study on the sustainability of hybrid learning in Uganda by [

88], the main obstacle was not the incapacity of teachers, but rather the absence of formal school-led programs and the required technological infrastructure, as presented by some of the participants indicated in the frequency table 7 above. This directly jeopardized the sustainability of the shift and the implementation of SDG4 in Liberia.

5.2.2. Pedagogical Competence

Even though a majority of the respondents did not offer HCRM, a small percentage of teachers had some practical experience using hybrid features, according to the sub-theme, “discipline, teaching, and learning”, with frequency n = 7 (19.44%), which was very significant for this study.

The codes related to the sub-theme indicated that the teachers understood that success in sustaining HCRM was all about the ability to use effective institutional strategies and maintain discipline across the two settings. These findings were consistent with those of [

23,

28,

89] who noted that the most crucial elements for successful learning outcomes in a setting with limited resources are teacher competencies that integrate discipline and instructional strategies, regardless of the technology platform.

P1: “Discipline is the most challenging aspect in CRM. I am successful in HCRM because I apply discipline in both online and in-person classrooms.”

P3: “I utilize classroom management technologies so that I can keep an eye on the actions of pupils in direct view, block websites that aren't approved, and enforce regulations that help kids stay focused. …… I am, therefore, good at managing hybrid classrooms.”

The participants demonstrated some experience in success in HCRM by indicating the application of innovative and adaptive institutional approaches, such as hands-on activities and the integration of games in a hybrid environment to control attention and motivate students’ engagement (p8, P25). The practical application of these approaches highlighted the pedagogical skills that can be applied when provided with the necessary digital didactic materials.

P8: “I am successful in HCRM. This is because I use different teaching methods on the various platforms. With online, I usually bring in games. To keep the students in the lesson since I am with them. This gives me an attentive environment for learning and assimilation of the material taught.”

P25: “I am successful in HCRM because I apply hands-on activities in my teaching method in both settings. Online, I look for educational games that students mostly like. Then, with face-to-face, I provide activities that are competitive in groups. Students like competing, you know?”

It was evident from their answers that they have the pedagogical abilities required for this innovative teaching to sustain the HCRM competencies. Grading the responses on HCRM success and the degree of sustainability of the shift was now a challenging task. As a result, this is viewed from the exterior perspective of a lack of support from institutions and infrastructure rather than the internal perspective of a lack of instructional expertise.

5.3. IQ3. From Your Own Point of View, What Are Some of the Important Aspects of Hybrid Education?

The purpose of this interview question was to find out how the teachers perceived the value of hybrid education. The potential of hybrid education to sustain learning was found to be highly acknowledged by the teachers.

5.3.1. Adaptability and Accommodation for Sustainable Education

From

Table 8 and

Figure 8 above, the sub-theme that registered the highest frequency, n = 20 (31.75%), was "ease of adaptation and accommodation," accumulated from its code’s “adaptation” n = 9 (14.29%) and “accommodation” n = 11 (17.46%), portraying the advantage of hybrid education as being flexible. The teachers felt that the flexibility aspect of hybrid education was important for sustainable education and inclusive pedagogical practice, which is a key factor of SDG4. The teachers also discussed how the hybrid curriculum meets a variety of students' requirements and learning capacities, which is important for raising students' academic achievement in a developing economy. This was highlighted by participants P7 and P19.

P7: “It is important because its accommodative and adaptive nature boosts students’ confidence by giving a chance to students who are shy during in-person lessons.”

P19: “Its adaptive and accommodative nature favors students with disabilities. Its flexibility permits students to take lessons from the comfort of their homes.”

This finding was also supported by the paper written by [

90], which stipulated that adaptation and accommodation top up as one of the important aspects of hybrid education. This viewpoint was also consistent with that of [

91] who stressed that successful hybrid pedagogy required both teachers' and students' flexibility and adaptability. The participants' opinions on this crucial component of hybrid education confirmed that this innovative approach improves social equity in education.

5.3.2. System Resilience and Contingency Planning

The ability of hybrid education to promote educational resilience was demonstrated by the considerable frequency of the sub-themes "contingency planning", n = 7 (11.11%), its codes “as a fallback", n = 3 (4.76%), and "continuation" (n = 4 (6.35%). By offering a long-term learning framework, the new model is acknowledged by the participants as preventing disruptions in education during pandemics, earthquakes, etc.

P18: “That is, teachers can now have access to their students from their homes or offices through online lessons. In times of trouble like strikes, shutdowns, etc., continuity of education is guaranteed.”

P23: “It is important because it provides a platform for a fallback in case there is another pandemic or epidemic. It also offers flexibility.”

This showed that the teachers realized the need for this new model of education. According to [

92,

93] the pandemic revealed the traditional school system's flaws, necessitating the adoption of a robust hybrid model.

5.3.3. Pedagogical Skills Improvement and Long-Term Skills

The codes “varieties of approaches” n = 8 (12.70%) and “Availability of materials” n = 1 (1.59%) developed under the sub-theme “teaching and learning and advantages” with frequency n = 9 (14.29); and the codes “skills” n = 8 (12.70%), and “others” n = 2 (3.17) developed from the sub-theme “long term benefits” with frequency n = 10 (15.87%) showed that the participants understood the new model`s role in enhancing the development of modern skill for both students and their educations.

The responses from P12 and P20 discussed of a “variety of approaches” that are in line with the goals of this special issue, which focuses on innovative teaching.

P12: “Hybrid education makes it easier for both teachers and students to have a variety of approaches to teaching and for students to learn, respectively.”

P20: “It provides a variety of approaches conducive for lecturers to use and students to study. With this, both teachers and students have the chance to develop various skills.”

When considering the idea of "skills," P9 and P11 showed that the participants were interested in acquiring digital skills, which are crucial in the 21st century [

94] and a major component of the workforce for social sustainability.

P9: “It allows greater flexibility, boosts the acquisition of digital skills, and its nature of accommodation and adaptation helps support both online and in-person students at the same time.”

P11: “Hybrid education brings in a variety of approaches to be used by teachers in their lessons. This permits the teachers to develop more skills in teaching.”

5.4. IQ4. Can You Give Some Suggestions on How to Improve Hybrid Classroom Management Sustainability in Your School and Liberia as a Whole?

The fourth interview question was the last one used to get ideas on how to make HCRM more sustainable in Liberia's junior and high schools.

5.4.1. Infrastructural Improvement to Enhance HRCM Sustainability

From

Table 9 and

Figure 9 above, the participants mostly talked of the sub-theme “availability and utility of materials” with frequency n = 26 (43.33%). With n = 21 (35.00%), the code "Availability of material" under this sub-theme had the highest frequency. This was also connected to the second interview question, which highlighted the problem of the digital divide. Teachers realized that giving them digital didactic resources will assist in advancing the sustainability of the shift, thus addressing SDG4. The educators proposed that the government's action in tackling this issue, along with the provision of steady electricity and strong internet, will significantly enhance the sustainability of the shift to HCRM and SDG4. Participants P3 and P4's presentations demonstrated this.

P3: “The government should improve the quality of the internet and power supply in the country, and subsidize teachers to get laptops. …… This will improve on HCRM and sustain the new system.”

P4: “Hybrid education requires a good quality of internet. So, if the government can make the internet available, it will improve on this system. Schools should provide digital gadgets and motivate teachers by giving them data allowances to teachers. This will improve on this new model, and its sustainability will be feasible.”

A study by [

65,

95] provided strong support for this viewpoint, revealing that even highly qualified educators struggle to successfully execute hybrid classroom management when faced with inadequate resources. It therefore stipulated that, to sustain the shift to HRCM in Liberia's junior and high school systems, there should be an equitable distribution of the digital resource.

5.4.2. Structured Training and Policy for Capacity Building

The next highest frequency, n = 22 (36.67%) representation of the sub-theme “Training”. Additionally, training, online skills, training schools, and workshops were discussed extensively. They solicited a clear policy on capacity building, especially through the codes, “Online and others”, n = 14 (23.33%), “Training schools”, n = 4 (6.67%), and “workshops and seminars”, n = 4 (6.67%).

The instructor suggested that Liberia's teacher training programs incorporate hybrid classroom management. Additionally, they recommended that workshops be regularly held for individuals who are already working in the field to acquire more advanced knowledge. Finally, they suggested the establishment of policies on institutionalizing hybrid pedagogy into teacher training curricula and systematizing digital professional development. The latter was closely related to SDG4's call for action, aiming 4.c, which emphasized a rise in the number of certified instructors. The recommendations made by P1 and P12 made these clear.

P1: “I believe that to best this improved hybrid education and HCRM institutions providing digital gadgets to teachers, training on online classroom management, will develop online classroom management skills and sustain its application.”

P12: “The Ministry of Education has to provide its schools with digital gadgets such as laptops for teachers and also training on how to use them for online lessons.”

The instructor asked for integrated training and seminars that would provide them with the necessary HCRM abilities [

36] to support innovative teaching while sustaining the novel model.

5.4.3. Institutional Motivation and Planning

The responses of the teachers with the codes “motivation” n = 5 (8.33%), “Planning” n=3 (5.00%), “Communication skills” n=2 (3.33%) and “skills” n = 2 (3.33%), under the sub-theme “Teaching and learning”, though with low frequency n = 12 (19.99%), recommended some institutional changes that are necessary for long-term sustainability of the shift. Participants like P19 and P7 suggested the integration of online activities into the school programs.

P19: “Schools plan activities; most have online activities. This will improve on hybrid education and HCRM.”

P7: “Teacher training schools have to train on how to use these materials in online classes, and plan the activities in the schools in such a manner that online activities are present. This will improve and sustain hybrid education and HCRM.”

The code “motivation” n = 5 (8.33%), was mentioned by participants P20 and P5 through salary increments and allowances, which is a vital component in sustaining hybrid education in Liberia due to the limited resources at their disposal.

P20: “Institutions should motivate teachers with free internet on campus, and provide some allowance that will permit them to get data to work at home.”

P5: “The institution has to provide laptops to teachers, provide training on how to use them to teach online, and provide data to motivate them. This can sustain this model.”

All things considered, the teacher's suggestions on the action plan help policymakers and educational stakeholders address SDG4 by offering answers to the sustainability of the HCRM.

5.5. Discussion on Key Findings

After the analysis of the lived experiences of the 26 participants using the hermeneutic phenomenological design, a critical sustainability gap in practically implementing hybrid classroom management (HCRM) post-COVID-19 was revealed. This sustainability gap was revealed by the following:

Non-structured institutional policy. The participants revealed that there was no formal, structured policy for the implementation of HCRM [

96], which rendered the sustainability of the shift fragmented and vulnerable. The efforts of the sustainability of the shift all rested on the shoulders of the teachers, giving it a higher chance of collapsing(cite).

Deficiency of resources. Limited resources and the inability to implement HCRM [

43,

94,

97] resulted in the non-sustainability of the shift. Most of the participants revealed that the shortage of digital devices and the sporadic electrical and internet supply highly contributed to the non-sustainability of the shift.

Pedagogical potential unrealized. The results showed that while components of continuity of learning and the enhancement of pedagogical abilities were crucial, there was a deficiency in professional development that focused on practical instructional skills for a hybrid environment [

97]. This revealed that the participants acknowledged the values in hybrid CRM, but they could not practically execute it effectively.

5.6. Discussion on Lived Experiences of Educational Sustainability and the Design Framework

5.6.1. Methodological Integration of Hermeneutic Phenomenological Design

Understanding the interconnection of lived experiences between the environmental, economic, and social components with the sustainability of HCRM was fundamental in assessing the sustainability of the shift. Here, the researcher chose the HPD, which was suitable in this context as it extended beyond the deductive thematic analysis approach of assessing the technological [

82] adaptation to a reflexive thematic analysis approach that explored the in-depth meaning of the lived experiences of the teachers [

80,

98] to identify the barriers that revealed the non-sustainable practices of HCRM. This was confirmed by the responses of most of the teachers who solicited policies of long-term educational changes that are practical and socially relevant.

5.6.2. Educators' Skills and Institutional Inequity

The lack of a policy relating to hybrid CRM [

96,

97] placed on the individual educators the burden of sustaining the shift. The system intentionally neglected the moral and professional capacity of its educators by failing to provide them with digital tools and organizational assistance. This disregard of human capital was a key flaw in social sustainability.

5.6.3. No Link Between Pedagogy and Practice

It was evident from the responses of the teachers that, even though they had the skills of HCRM, the practical implementation was not realized due to the lack of digital devices, a lack of policy, and the sporadic internet and electrical power supply [

97].

5.6.4. Poor Educational Quality (SDG4)

From the responses of the teachers, it was revealed that the achievement of SDG4, quality education, was compromised due to the gap in sustainability. It was revealed that the HCRM skills were essential to quality educational continuity in times of crisis. The lack of SDG4`s long-term adaptability was demonstrated by the lack of institutional policies and the lack of provision of digital devices.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions

This research work brought to light some significant aspects that are related to the sustainability of the shift to hybrid education, the issues surrounding the hybrid classroom management skills, and information on SDG4 from the viewpoint of Liberian junior and high school teachers. The study looked at the issues surrounding the teachers' competencies in hybrid classroom management, suggesting how to sustain the shift to hybrid education in Liberia. It examined issues, suggestions, and teacher competencies surrounding the sustainability of the shift to a hybrid model in Liberia.

The teachers showed their understanding of the concept of hybrid classroom management. Hybrid classroom management from the viewpoint of the teachers instills a strong teacher-student relationship, encourages a positive learning environment, and thus maintains discipline [

92,

99,

100]. The teachers also presented their concept of hybrid classroom management as just applying the face-to-face skills in an online lesson [

38,

91,

92,

101]. Among some of the skills that were presented by the teachers, flexibility skills stood out as significant during this era of hybrid education [

93].

With the global issues such as pandemics, epidemics, and climate change, the significant frequency of hybrid education as a means of contingency planning in education shows that sustaining the shift to hybrid education is an alarming aspect in this era [

93]. This research work brought to light the concept of shared participation between the teachers and the stakeholders in sustaining the shift, to guarantee a stable educational system [

10,

11,

102].

Notwithstanding limited digital infrastructure, sporadic supply of internet and electrical power, the absence of a structured official hybrid policy in schools, and insufficient professional development, all stood as significant gaps in sustaining the shift. Most schools lacked the infrastructure for this hybrid approach, participants lacked the training, and they lacked the devices required to teach online [

103,

104].

These challenges showed that the “Sustained Shift” was difficult due to the lack of necessary institutional policies and frameworks for resources [

4,

105]. It demonstrated that without a comprehensive strategy involving institutional leadership and investment, the chance of pedagogical and technological advancement to promote the sustainable progress of hybrid classroom management may not be fully attained [

4,

30,

105,

106]. This concept of discussion is in line with the information in the literature review that sustaining the shift is not just the teacher's effort [

30,

104,

107].

It was definite from the on-ground first-hand findings that the sustainability of the shift and accomplishment of the SDG4 faced some challenges in emerging economic nations. It was evident that the teachers solicited the Ministry of Education, stakeholders in education, and lawmakers to spearhead their recommendations [

103].

6.2. Recommendations

From the results of the study, it was clear that to sustain the shift in Liberia, several strategies have to be put in place. Structural and institutional support, together with teachers' skills in online settings, have to be put in place. The recommendations below were presented to close the gap between the practical application and the educators' concept of sustaining the shift.

6.2.1. Make Clear and Comprehensive Policies

From the results, it was recommended that educational stakeholders and the Ministry of Education in Liberia, in particular, should spell out explicit procedures and policies relating to the sustainability of the shift to hybrid education. It was clear from the study that there was no clear policy put in place for this purpose. This will reduce the aspect of the shift becoming an irregular, fragmented undertaking. Innovative teaching techniques can be fully integrated into educational practices, approved by leadership, and used to inform instructional decision-making by implementing a comprehensive education for sustainability strategy [

108]. This tactical approach is essential to fostering systemic change and avoiding the sustained Shift from becoming a fragmented, irregular undertaking.

6.2.2. Prioritize Investment in Digital Infrastructure

It was clearly stated by the teachers that there is a shortage in digital gadgets, power, and internet supply, which acts as the main obstacle to this shift. It was recommended to the policy makers of Liberia to raise funds to solve this issue so as to sustain the shift. It is difficult to implement online or hybrid learning if these basics are not achieved [

88,

95,

103]. In the presence of pedagogical skills, the success of educational models depends on the availability and good functional state of the technical infrastructures [

88,

104].

6.2.3. Implementing Targeted Professional Development

Even though the teachers indicated the need for formal training on this new digital concept, their points on continuous upgrading were also taken into account. In this light, it was also recommended that professional training programs should be put in place by the educational stakeholders to concentrate on the practical part of this new paradigm, such as instructional skills in a hybrid environment, rather than just mere technical skills [

88,

104]. Since active learning deals with problem solving and critical thinking, such a program will assist teachers in acquiring the skills on how to use technology for these purposes [

88,

107]. This meets the global demands to equip educators with the skills they need in this evolving era [

109,

110].

6.2.4. Foster Collaborative Learning Communities

Collaborative learning communities should be established by the Ministry of Education to permit teachers from different schools to come together once a month or so, to share their experiences in this new model. This will accelerate peer collaboration and enhance the understanding of how to manage a hybrid setting. Teachers will be able to address issues together, exchange good skills, and adjust to this novel educational setting using this platform [

104,

111]. This collaborative approach is one significant factor of the resilience of an educational system, which can significantly improve on this new model [

104,

111]. These teachers can easily develop the skills needed to maintain this shift as teachers freely relate among themselves, challenging each other and learning from each other. When this is done, it will ensure some equity in education, as it can result in students everywhere having quality education satisfying the SDG4 objectives [

30,

88,

104].

6.2.5. Future Research

Future studies should look into the long-term effects of particular policy changes, as well as effective, reasonably priced technology solutions for classroom management in comparable settings [

37]. A quantitative technique can be used to conduct the same trials to see if the findings would correlate. This would also advance a more thorough comprehension of how to create an educational system that is genuinely robust, equitable, and ready for a sustainable future.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material S1. Ethical Approval (From the Researcher's university); Supplementary Material S2. Authorization from research sites (Liberia's Junior High Schools); Supplementary Material S3. Interview guide; Supplementary Table S4. Table of themes, sub-themes, code, frequencies, and corresponding response.; Supplementary Material S5. The Row data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.N.T.; methodology, R.N.T., data collection, R.N.T., data analysis R.N.T., and writing, R.N.T.; review and editing, E.S., and F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Near East University, Nicosia, Cyprus (NEU/ES/2013/956 approved on the 15th of March 2023) for studies involving humans. The 23 schools where the research was conducted also gave their permission (Supplementary Material S2. Liberia`s junior and high schools' permissions) to indicate their consent in reaffirmation of the Declaration of Helsinki for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Following the briefing session in each school, all research participants who volunteered provided informed consent by providing their phone numbers.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the text and in the supplementary material as stated in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRM |

Classroom management |

| HCRM |

Hybrid classroom management |

| HPD |

Hermeneutic Phenomenological Design |

| RTA |

Reflexive Thematic Analysis |

| DQ |

Demographic question |

| IQ |

Interview question |

References

- Bao, W. COVID-19 and Online Teaching in Higher Education: A Case Study of Peking University. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 2020, 2, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.; Butler-Henderson, K.; Rudolph, J.; Malkawi, B.; Glowatz, M.; Burton, R.; Magni, P.A.; Lam, S. COVID-19: 20 Countries’ Higher Education Intra-Period Digital Pedagogy Responses. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching 2020, 3, 09–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutri, R.M.; Mena, J.; Whiting, E.F. Faculty Readiness for Online Crisis Teaching: Transitioning to Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Teacher Education 2020, 43, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racheva, V.; Peytcheva-Forsyth, R. NAVIGATING THE FUTURE: EXPLORING SYNCHRONOUS HYBRID LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATION POST-COVID. INTED2024 Proceedings 2024, 1, 6335–6345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in Education: A Tool on Whose Terms? Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, N. Policy Learning in Times of Crisis: A Cross-National Comparative Study of COVID-19 Responses in Australia and the United Kingdom, 2020-2024. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Rule, N.O. From Pandemic Crisis to Recovery and Resilience: Lessons from COVID-19 at a Large Urban Research University. Studies in Higher Education 2025, 50, 200–215. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO United Nation Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2022). UNESCO 2 Strategy on Education for Health and Well-Being. Paris: UNESCO. Unesdoc 2022.

-

UNESCO UNESCO Futures of Education Initiative: Learning to Live Together; UNESCO, 2021.

- UNESCO Monitoring Education in the Sustainable Development Goals - Global Education Monitoring Report 2023. Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in education – A tool on whose terms? 2023, 526.

-

UNESCO Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO, 2023.

- Regehr, C.; Rule, N.O. Addressing Challenges to Recovery and Building Future Resilience in the Wake of COVID-19. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Pierre, du P. The Role of Classroom Management in Enhancing Learners’ Academic Performance: Teachers’ Experiences. Studies in Learning and Teaching 2024, 5, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, E.; Yanto, M. Classroom Management: Boosting Student Success—a Meta-Analysis Review. Cogent Education 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifesinachi, E.J.; Dadzie, J.; Ocheni, A.C. ENHANCING STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT IN BASIC SCIENCE: THE ROLE OF ASSESSMENT FOR LEARNING, CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT, AND TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS. European Journal of Education Studies 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dellova, R.I.; Yi, Z. Redefining Educational Success: Analyzing the Impact of Closed Management Systems on Student Well-Being and Academic Performance in Chinese Technical. journals.sagepub.comJ Liu, RI Dellova, Z YiE-learning and Digital Media, 2024•journals.sagepub.com 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aydın, D.; Karabay, S. Improvement of Classroom Management Skills of Teachers Leads to Creating Positive Classroom Climate. International Journal of Educational Research Review 2020, 5, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIntyre, P.; Gregersen, T.; System, S.M.-. undefined Language Teachers’ Coping Strategies during the Covid-19 Conversion to Online Teaching: Correlations with Stress, Wellbeing and Negative Emotions; Elsevier, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Putra, E.; Yanto, M. Classroom Management: Boosting Student Success—a Meta-Analysis Review. Cogent Education 2025, 12;SUBPAGE:STRING:FULL. [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. The Post COVID-19 Pandemic Era: Changes in Teaching and Learning Methods for Management Educators. International Journal of Management Education 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ydo, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, D.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Opertti, R.; Liu, D.; Tlili, A.; et al. A Guideline Framework of Hybrid Education, Learning, and Assessment (HELA) Version A Guideline Framework for Hybrid Education, Learning, and Assessment. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hoofman, J.; Secord, E. The Effect of COVID-19 on Education. Pediatr Clin North Am 2021, 68, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, R.; Shilongo, H. Hybrid and Blended Learning Models: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions in Education. Acta Pedagogia Asiana 2025, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, R.; Shilongo, H. Hybrid and Blended Learning Models: Innovations, Challenges, and Future Directions in Education. Acta Pedagogia Asiana 2024, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Bashir, S.; Rana, K.; Lambert, P.; Vernallis, A. Post-COVID-19 Adaptations; the Shifts Towards Online Learning, Hybrid Course Delivery and the Implications for Biosciences Courses in the Higher Education Setting. Front Educ (Lausanne) 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Horn, M.B.; Staker, H. Is K-12 Blended Learning Disruptive? 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mekhlafi, A.G.; Zaneldin, E.; Ahmed, W.; Kazim, H.Y.; Jadhav, M.D. The Effectiveness of Using Blended Learning in Higher Education: Students’ Perception. Cogent Education 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Cezarino, L.O.; Challco, G.C.; Liboni, L.; Dermeval, D.; Bittencourt, I.; Paiva, R.; da Silva, A.; Marques, L.; Isotani, S.; et al. The Role of Hybrid Learning in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainable Development 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracke, C.M.; Sharma, R.C.; Bozkurt, A.; Burgos, D.; Cassafieres, C.S.; dos Santos, A.I.; Mason, J.; Ossiannilsson, E.; Santos-Hermosa, G.; Shon, J.G. Impact of COVID-19 on Formal Education. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 2022, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhamo, G.; Chapungu, L.; Togo, M. COVID-19 Impacts on School Operations: A Pushback on the Attainment of SDG 4 in South Africa. Taylor & FrancisG Nhamo, L Chapungu, M TogoCogent Education, 2024•Taylor & Francis 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurbaya, S.; Sutrisnowati, S.A. Folklore as an Honest Character Education Media to Achieve Quality Education in Sustainable Development Goals. Journal of Lifestyle and SDGs Review 2025, 5, e04695–e04695. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Han, S.H. The Future of Service Post-COVID-19 Pandemic, Volume 1 The ICT and Evolution of Work Series Editor: Jungwoo Lee.

- Areba, G.; George Ngwacho, A. COVID-19 Pandemic Impact on Kenyan Education Sector: Learner Challenges and Mitigations. 2020, Vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kamoet, P.C. EFFECT OF CLASSROOM ENVIRONMENT ON ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT OF SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS IN MOMBASA COUNTY, KENYA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION (EDUCATIONAL ADMINISTRATION) IN SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND LIFELONG LEARNING. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.R. From Discipline to Dynamic Pedagogy: A Re-Conceptualization of Classroom Management. Berkeley Review of Education 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, V.; Fante, C.; Caruso, G.; De Gregorio, E.; Ravicchio, F. DIMENSIONS AND FACTORS TO MANAGE AN HYBRID CLASSROOM DIMENSIONI E FATTORI PER GESTIRE UNA CLASSE IBRIDA. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, K. Promoting Successful Learning in Remote and Hybrid Classrooms; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shuhratovich, S.S. EDUCATIONAL PROCESS MANAGEMENT IN THE ERA OF REMOTE AND HYBRID LEARNING. Journal of Applied Science and Social Science 2025, 1, 698–704. [Google Scholar]

- Ndunge Kyalo, D.; Jepketer, A.; Kombo, K. Public Secondary Schools in Nandi County; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W. Online and Remote Learning in Higher Education Institutes: A Necessity in Light of COVID-19 Pandemic. Higher Education Studies 2020, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, G.; Nepal, A.K.; Hussain, A.; Maharjan, A.; Joshi, S.; Lama, A.; Gurung, P.; Ahmad, F.; Mishra, A.; Sharma, E. Socio-Economic Implications of COVID-19 Pandemic in South Asia: Emerging Risks and Growing Challenges. Frontiers in Sociology 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, S.O.; Ajani, Y.A.; Abdulrahman, M.R. Smart Learning as Transformative Impact of Technology: A Paradigm for Accomplishing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Education. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, M.M.H.; Subroto, S.; Chowdhury, N.; Koch, K.; Ruttan, E.; Turin, T.C. Dimensions and Barriers for Digital (in)Equity and Digital Divide: A Systematic Integrative Review. Digital Transformation and Society 2025, 4, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Sharma, A.; Jeswani, S.; Sharma, D.; Gupta, A. Spotlighting Recruitments: Is AI Dominating Human Resource Practices? Qualitative Research Using NVIVO. SpringerP Pandey, A Sharma, S Jeswani, D Sharma, A GuptaQuality & Quantity, 2025•Springer 2025, 59, 1209–1228. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Novelli, M. The Effect of the Ebola Crisis on the Education System’s Contribution to Post-Conflict Sustainable Peacebuilding in Liberia The Research Consortium on Education and Peacebuilding; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Research, G.K.-A.J. of E.; 2024, undefined Assessing Lecturers’ Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Teaching Online Courses at Selected Universities in Liberia. researchgate.netGM KennedyAmerican Journal of Educational Research, 2024•researchgate.net.

- Ministry of Education Liberia Republic of Liberia Ministry of Education; 2022.

- Kounin, J.S. Discipline and Group Management in Classrooms; Holt: Rinehart and Winston, 1970.

- Emmer, E.T.; Evertson, C.M. Classroom Management for Secondary Teachers; Pearson Education, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Research on the Impact of Teachers’ Instructional Leadership on Classroom Teaching Quality. Journal of Education and Educational Research 2024, 8, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning 2004, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Plueger, C.T. THE LIVED EXPERIENCES OF EDUCATORS LEVERAGING EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND CONNECTIVISM FOR FOSTERING ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT IN HIGHER EDUCATION: A TRANSCENDENTAL PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yassin, M.K. Technology Integration in Learning Ecosystems. In Revitalizing the Learning Ecosystem for Modern Students; IGI Global, 2024; pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi, A.; Cadmus, A.M. 2024, undefined ICT & Generative Artificial Intelligence Powered Hybrid Model for Future Education. cadmusjournal.orgA Jaouadi, A MaaradjiCadmus;2024•cadmusjournal.org.

- Education, L.S.-S.I.J. of; 2024, undefined Critical Analysis of the Research on Digital Literacy. journal.sinergi.or.idL SusantySinergi International Journal of Education;2024•journal.sinergi.or.id.

- Wang, W.; Kashian, N. The Story My Friend Told Me: Examining the Interplay of Message Format and Relational Closeness in Misinformation Correction. Taylor & FrancisW Wang, N KashianMedia Psychology, 2025•Taylor & Francis 2025, 28, 412–438. [CrossRef]

- Maragha, A.; Bulbul, A. DEVELOPING AN INSTRUCTIONAL MODEL BASED ON THE COMMUNICATIVE PRACTICES AND ROLE OF PROPHET MOHAMMAD (PBUH). researchgate.netAV Maragha, A Bulbulresearchgate.net.

- Suriano, R.; Plebe, A.; Acciai, A.; Instruction, R.F.-L. and; 2025, undefined Student Interaction with ChatGPT Can Promote Complex Critical Thinking Skills. ElsevierR Suriano, A Plebe, A Acciai, RA FabioLearning and Instruction, 2025•Elsevier.

- Cariaga, R. The Basic Concepts of Philosophy. Available at SSRN. 2024, 4943235. [Google Scholar]

- Research, L.Y.-I.J. of E. and; 2024, undefined A Comprehensive Review: Exploring Educators’ Insights on Cultivating Critical Thinking Ability among Secondary School Students in English Writing Instruction In. ijern.comL YangInternational Journal of Education and Research, 2024•ijern.com.

- Moustaka, I.; Doukakis, S.; Mattheoudakis, M. The Use of Mobile Applications in the L2 Learning Classroom: Is It Worth the While? SpringerI Moustaka, S Doukakis, M MattheoudakisInteractive Mobile Communication, Technologies and Learning, 2023•Springer 2024, 936 LNNS, 281–289. [CrossRef]

- Science, I.I.-I.J.M.; 2024, undefined Exploring Modern Educational Theories: A Literature Review of Student Learning in The Digital Age. journal.admi.or.idI IsmailInternational Journal Multidisciplinary Science, 2024•journal.admi.or.id 2024, ISSN, 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Maryati, Y. Humanism in Philosophical Studies. Journal of Innovation in Teaching and Instructional Media 2024, 4, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engagement, J.Z.-. Motivation, undefined; Achievement, and S.; 2024, undefined Engagement, Motivation, and Students’ Achievement. SpringerJ ZajdaEngagement, Motivation, and Students’ Achievement, 2024•Springer 2024, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Gusango, E.H.; Ocheng, M.T.K.; Wambi, M.; Buluma, A.; Tusiime, W.E. Constructivists’ Teacher-Preparation Strategy for Crossover to the 21st Century: A Case of Eastern Uganda. GPH-International Journal of Educational Research 2024, 7, 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kholei, A.O. Hermeneutic Phenomenology for Spatial Analysis. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 2022, 16, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkori, L. Hermeneutics and Phenomenology Problems When Applying Hermeneutic Phenomenological Method in Educational Qualitative Research. Paideusis 2009, 18, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Methodology, M.S.A.-P. of S.R.; 2022, undefined Narrative Inquiry, Phenomenology, and Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research. SpringerR Islam, M Sayeed AkhterPrinciples of Social Research Methodology, 2022•Springer 2022, 101–115. [CrossRef]

- Aagaard, J.; Steninge, E.; Zhang, Y. On the Hermeneutics of Screen Time: A Qualitative Case Study of Phubbing. AI Soc 2021, 38, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, F.; Rodger, S.; Ziviani, J.; Boyd, R. Application of a Hermeneutic Phenomenologically Orientated Approach to a Qualitative Study. Int J Ther Rehabil 2012, 19, 370–378. [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Métodos de Investigación Cualitativa: Recopilación de Evidencia, Elaboración de Análisis, Comunicación Del Impacto. 2020, 450. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley & Sons, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Morral-Yepes, R.; Smith, A.; Sondhi, S.L.; Pollmann, F. Entanglement Transitions in Unitary Circuit Games. APSR Morral-Yepes, A Smith, SL Sondhi, F PollmannPRX Quantum 2024•APS 2024, 5, 10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H. Purposeful Sampling in Qualitative Research Synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.C.; Haug, J.K. Turnover Flash Estimation by Purposive Sampling and Debit Card Transactions. journals.sagepub.com 2025, 41, 382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, W.B.; Ago, F.Y. Sample Size for Interview in Qualitative Research in Social Sciences: A Guide to Novice Researchers. Research in Educational Policy and Management 2022, 4, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, N.; Gulab, F.; Aslam, N. Development of Qualitative Semi-Structured Interview Guide for Case Study Research. Competitive Social Sciences Research Journal (CSSRJ) 2022, 3, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic Methodological Review: Developing a Framework for a Qualitative Semi-Structured Interview Guide. J Adv Nurs 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobe, B.; Morgan, D.L.; Hoffman, K. A Systematic Comparison of In-Person and Video-Based Online Interviewing. journals.sagepub.comB Lobe, DL Morgan, K HoffmanInternational Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2022•journals.sagepub.com 2022, 21, 1–12. [CrossRef]