Submitted:

29 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preparation of CAR-T Cells

3. Generations of CAR-T Cells

4. Toxicities in CAR-T Cell Therapy

5. Management of Toxicities in CAR-T Cell Therapy

5.1. Management of Cytokine-Release Syndrome (CRS)

5.2. Management of CRS-Related Coagulopathy:

5.3. Management of T and B Lymphocytes Aplasia and Infections

5.4. Management of Cytopenias

5.5. Management of GVHD

6. CAR-T Cells and Targeted Antigens in Cancer Treatments: Importance, Future Insights, Strengths, and Weaknesses

6.1. Importance of Targeted Antigens

6.2. Future Insights

6.3. Strengths of CAR-T Therapy

6.4. Weaknesses of CAR-T Therapy

6.5. bb21217 CAR-T Cell Therapy

6.6. CART-PSMA Therapy

6.7. CAR-EGFRvIII Therapy

6.8. MUC1-CAR-T Cell Therapy

6.9. Mesothelin-CAR-T Cell Therapy

6.10. ALLO-501 Therapy

6.11. ALLO-501A Therapy

6.12. JCARH125 Therapy

6.13. CT053 Therapy

7. Other Cells That Belong to the Arsenal of CAR-T Cells

7.1. CD22 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.2. CD20 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.3. HER2 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.4. GD2 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.5. GPC3 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.6. ROR1 (Receptor Tyrosine Kinase-like Orphan Receptor 1) CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.7. NY-ESO-1 CAR-T Cell Therapy

7.8. NKG2D CAR-T Cell Therapy

8. Methods for Studying the Binding of CAR-T Cells to Antigens and Their Importance

8.1. Methods for Studying the Binding of CAR-T Cells to Antigens and Their Importance

8.2. Importance of Studying CAR-T Cell Binding

8.3. Future Directions: The Need for New Methods

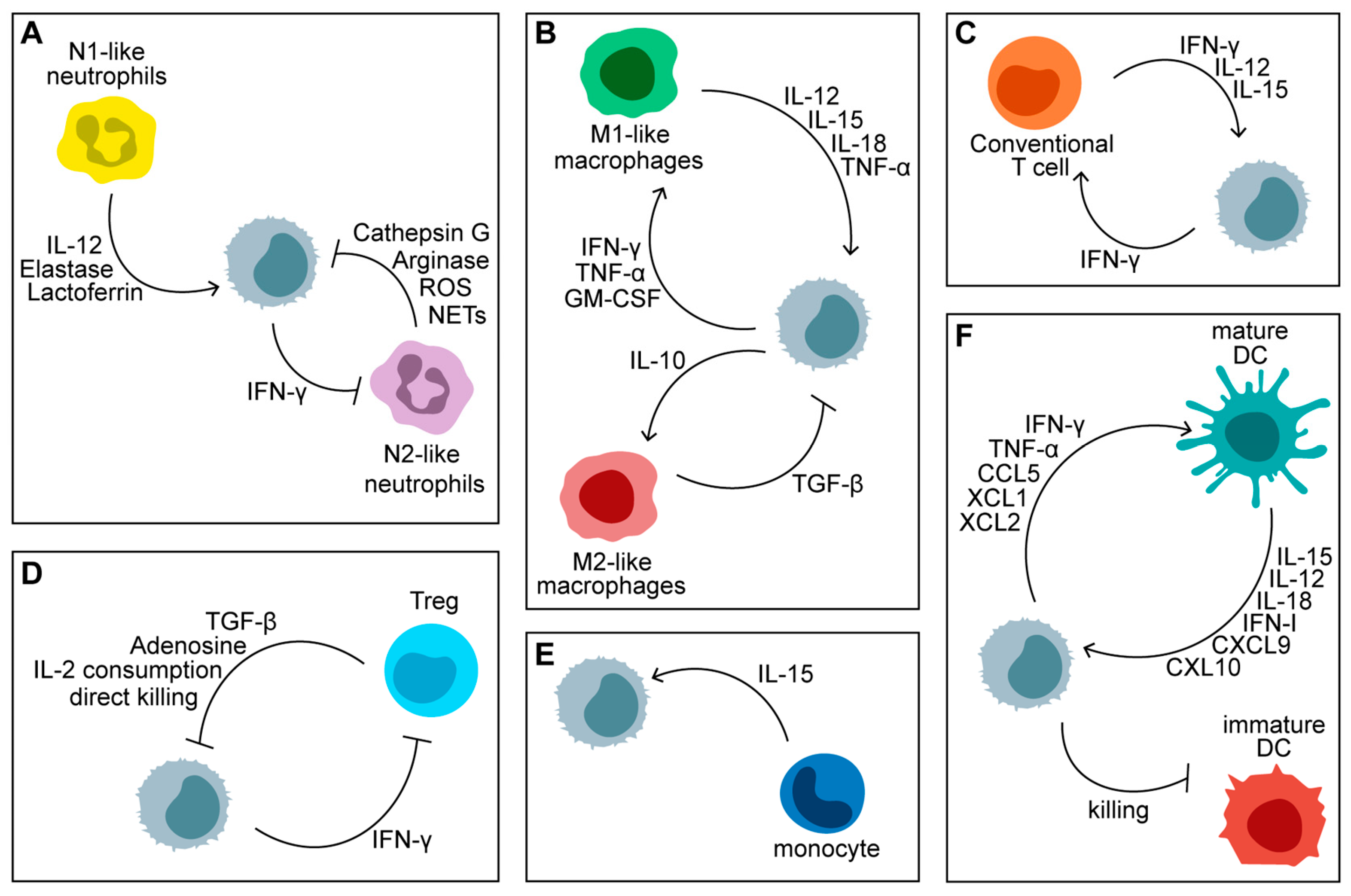

10. Advancements in NK CAR Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy

10.1. Introduction to NK Cells and CAR Technology

10.2. Development of NK CAR Cells

10.3. Challenges in the Development of NK CAR Cells

10.4. Clinical Applications of NK CAR Cells

10.5. Future Directions

11. The Potential of γδ T Cells in Mitigating GVHD

12. Exploration of Other Important Cell Types That Also Hold Promise as Sources for Universal CAR-T Therapies

12.1. TCR Knockout T Cells

12.2. Natural Killer T (NKT) Cells

12.3. Invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) Cells

12.4. Double-Negative (CD4- CD8-) T Cells

12.5. CAR Macrophages Cells

12.6. CAR Neutrophils Cells

12.7. CD5 Knockout on CAR T Cells

12.8. Mucosal-Associated Invariant T (MAIT) Cells

12.9. CAR MAIT Cells

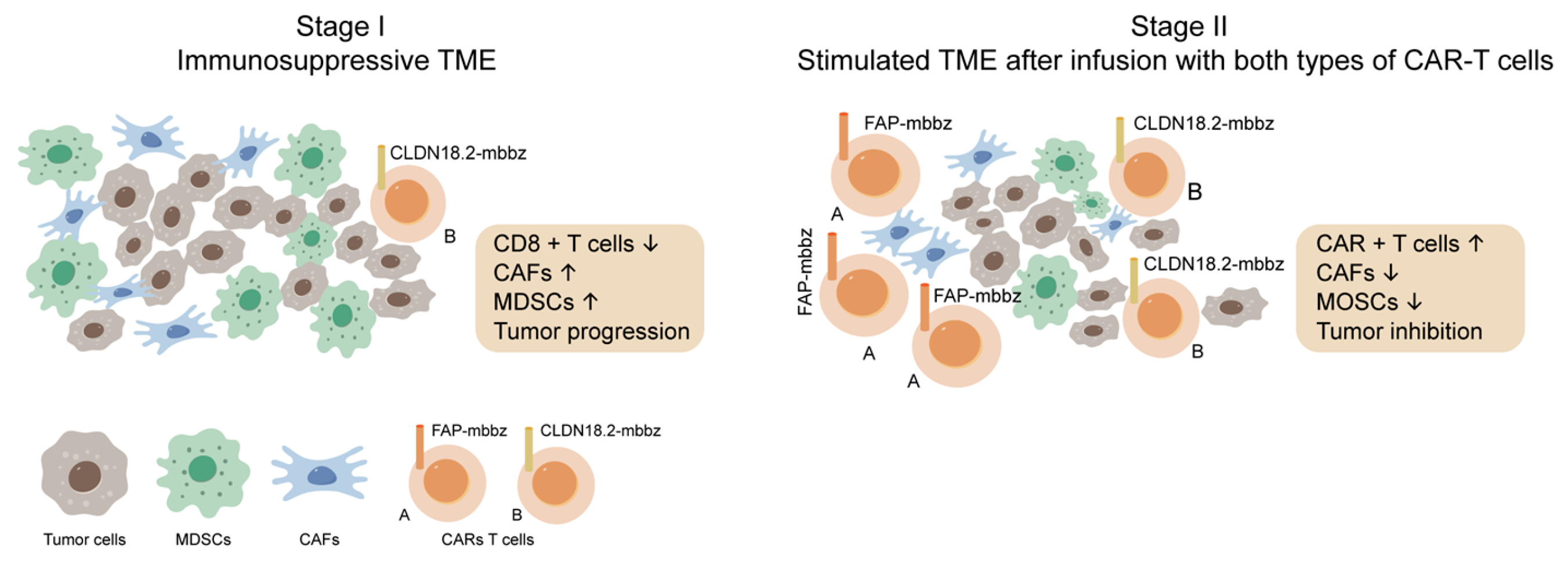

12.10. Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP) CAR-T Cells

12.10. Is There Any Probability of the Creations of CAR TAM Cells

- CAR-TAMs: It is possible to engineer macrophages to express CARs targeting specific tumor antigens [210,211,212]. This approach could help reprogram TAMs to act against the tumor rather than supporting it. For example, CAR-TAMs could be designed to recognize tumor antigens, enabling them to phagocytose tumor cells or modulate the tumor microenvironment to inhibit tumor growth and promote anti-tumor immunity. However, engineering macrophages is more complex than T cells due to their different biology and the challenges in efficiently transducing macrophages with viral vectors used in CAR therapy [210,231].

- Cell Plasticity: TAMs are highly plastic and can change their phenotype based on environmental signals [233], which might complicate CAR design and functionality.

- Immunosuppresive nature: The mechanisms of immunosuppresion employed by TAMs are targeted towards inhibiting the activity of the adaptive immune system, including NK cells and T cells [233].

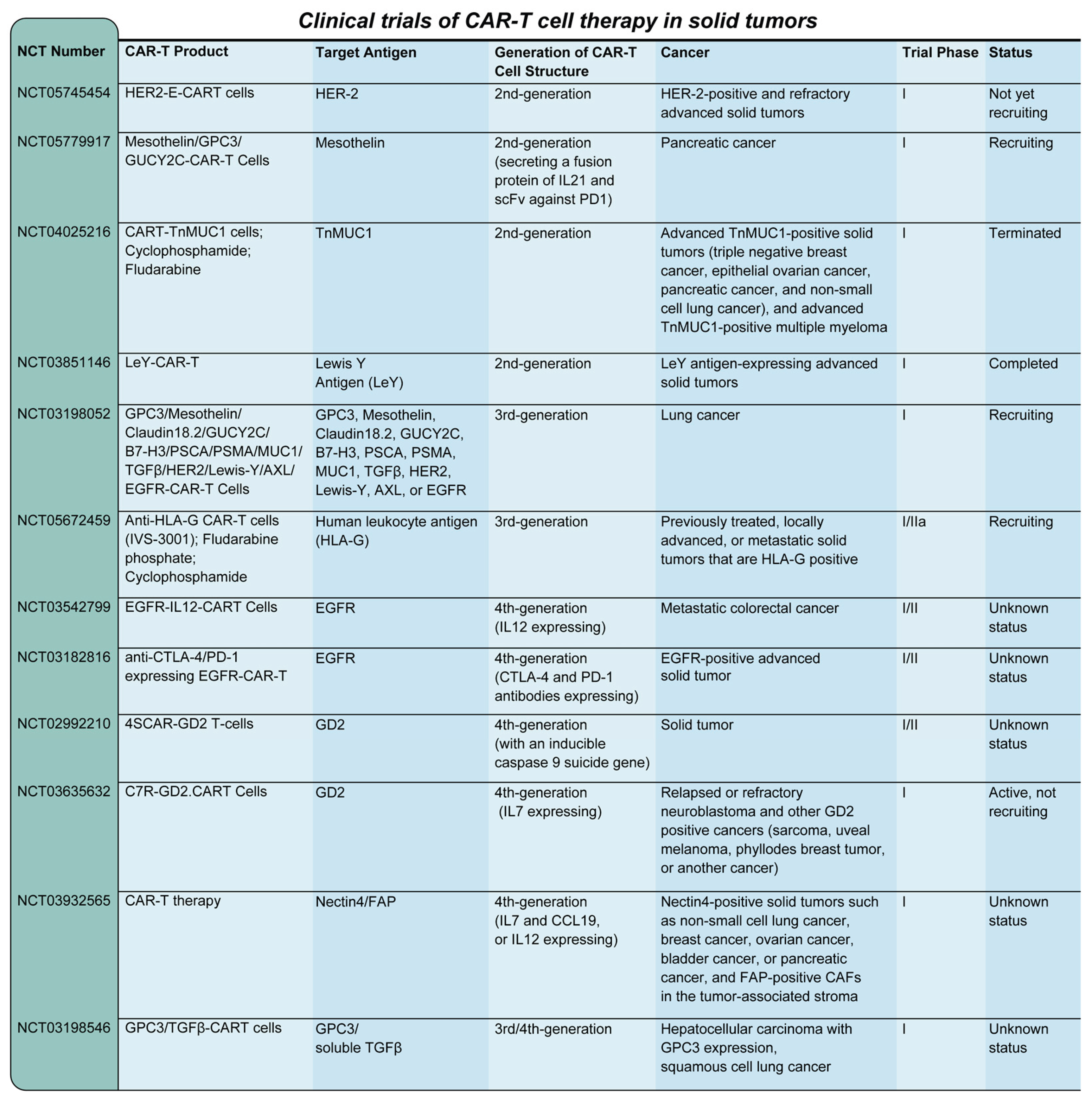

13. Clinical Trials of CAR-T Cell Therapy of Solid Tumors

13.1. Clinical Trials

13. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X; Zhu, L; Zhang, H; Chen, S; Xiao, Y. CAR-T cell therapy in hematological malignancies: current opportunities and challenges. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 927153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, SJ; Bishop, MR; Tam, CS; Waller, EK; Borchmann, P; McGuirk, JP; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, W; Shi, M; Yang, J; Cao, J; Xu, L; Yan, D; et al. Phase II trial of co-administration of CD19- and CD20-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 5827–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelapu, SS; Locke, FL; Bartlett, NL; Lekakis, LJ; Miklos, DB; Jacobson, CA; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 2531–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, CA; Chavez, JC; Sehgal, AR; William, BM; Munoz, J; Salles, G; et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel in relapsed or refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (ZUMA-5): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, FL; Ghobadi, A; Jacobson, CA; Miklos, DB; Lekakis, LJ; Oluwole, OO; et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N; Mo, F; McKenna, MK. Impact of manufacturing procedures on CAR T cell functionality. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 876339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbé, RP; Vessillier, S; Rafiq, QA. Lentiviral vectors for T cell engineering: clinical applications, bioprocessing and future perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, M; Solomon, SR; Arnason, J; Johnston, PB; Glass, B; Bachanova, V; et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel versus standard of care with salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as second-line treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma (TRANSFORM): results from an interim analysis of an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 2294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A; Hoda, D; Riedell, PA; Ghosh, N; Hamadani, M; Hildebrandt, GC; et al. Lisocabtagene maraleucel as second-line therapy in adults with relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma who were not intended for haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (PILOT): an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1066–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharfan-Dabaja, MA; Yassine, F; Moustafa, MA; Iqbal, M; Murthy, H. Lisocabtagene maraleucel in relapsed or refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma: what is the evidence? Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2022, 15, 168–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, NC; Anderson, LD, Jr.; Shah, N; Madduri, D; Berdeja, J; Lonial, S; et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 705–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, DK; Sidana, S; Peres, LC; Leitzinger, CC; Shune, L; Shrewsbury, A; et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: real-world experience from the myeloma CAR T consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 2087–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, S; Lin, Y; Goldschmidt, H; Reece, D; Nooka, A; Senin, A; et al. KarMMa-RW: comparison of idecabtagene vicleucel with real-world outcomes in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdeja, JG; Madduri, D; Usmani, SZ; Jakubowiak, A; Agha, M; Cohen, AD; et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 2021, 398, 314–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, JQ; Zhao, W; Jing, H; Fu, W; Hu, J; Chen, L; et al. Phase II, open-label study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor-T-cell therapy, in Chinese patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (CARTIFAN-1). J Clin Oncol. 2023, 41, 1275–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindo, L; Wilkinson, LH; Hay, KA. Befriending the hostile tumor microenvironment in CAR T-cell therapy. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 618387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, M; Gottschalk, S. Engineered cytokine signaling to improve CAR T cell effector function. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 684642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cantillo, G; Urueña, C; Camacho, BA; Ramírez-Segura, C. CAR-T cell performance: how to improve their persistence? Front Immunol 2022, 13, 878209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, C; Venetis, K; Sajjadi, E; Zattoni, L; Curigliano, G; Fusco, N. CAR-T cell therapy for triple-negative breast cancer and other solid tumors: preclinical and clinical progress. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2022, 31, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G; Reed, MR; Bielamowicz, K; Koss, B; Rodriguez, A. CAR-T therapies in solid tumors: opportunities and challenges. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023, 25, 479–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roex, G; Campillo-Davo, D; Flumens, D; Shaw, PAG; Krekelbergh, L; De Reu, H; et al. Two for one: targeting BCMA and CD19 in B-cell malignancies with off-the-shelf dual-CAR NK-92 cells. J Transl Med. 2022, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viardot, A; Locatelli, F; Stieglmaier, J; Zaman, F; Jabbour, E. Concepts in immuno-oncology: tackling B cell malignancies with CD19-directed bispecific T cell engager therapies. Ann Hematol. 2020, 99, 2215–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, KA; Turtle, CJ. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells: lessons learned from targeting of CD19 in B-cell malignancies. Drugs 2017, 77, 237–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strati, P; Neelapu, SS. CAR-T failure: beyond antigen loss and T cells. Blood 2021, 137, 2567–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulgaonkar, A; Udayakumar, D; Yang, Y; Harris, S; Öz, OK; Ramakrishnan Geethakumari, P; et al. Current and potential roles of immuno-PET/-SPECT in CAR T-cell therapy. Front Med. 2023, 10, 1199146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duell, J; Leipold, AM; Appenzeller, S; Fuhr, V; Rauert-Wunderlich, H; Da Via, M; et al. Sequential antigen loss and branching evolution in lymphoma after CD19- and CD20-targeted T-cell-redirecting therapy. Blood 2024, 143, 685–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haideri, M; Tondok, SB; Safa, SH; Maleki, AH; Rostami, S; Jalil, AT; et al. CAR-T cell combination therapy: the next revolution in cancer treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z; Lei, W; Wang, H; Liu, X; Fu, R. Challenges and strategies associated with CAR-T cell therapy in blood malignancies. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, JH; Frank, MJ; Craig, J; Patel, S; Spiegel, JY; Sahaf, B; et al. CD22-directed CAR T-cell therapy induces complete remissions in CD19-directed CAR-refractory large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2021, 137, 2321–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, SL; Laetsch, TW; Buechner, J; Rives, S; Boyer, M; Bittencourt, H; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 439–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, MV; June, CH. Making better chimeric antigen receptors for adoptive T-cell therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1875–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M; Brentjens, R; Rivière, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- June, CH; Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, DW; Kochenderfer, JN; Stetler-Stevenson, M; Cui, YK; Delbrook, C; Feldman, SA; et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 517–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maude, SL; Frey, N; Shaw, PA; Aplenc, R; Barrett, DM; Bunin, NJ; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014, 371, 1507–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, BL; Miskin, J; Wonnacott, K; Keir, C. Global manufacturing of CAR T cell therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2017, 4, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtle, CJ; Hanafi, LA; Berger, C; Hudecek, M; Pender, B; Robinson, E; et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2016, 8, 355ra116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuser, C; Hombach, A; Lösch, C; Manista, K; Abken, H. T-cell activation by recombinant immunoreceptors: impact of the intracellular signalling domain on the stability of receptor expression and antigen-specific activation of grafted T cells. Gene Ther. 2003, 10, 1408–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedan, S; Posey, AD, Jr.; Shaw, C; Wing, A; Da, T; Patel, PR; et al. Enhancing CAR T cell persistence through ICOS and 4-1BB costimulation. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e96976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, HM; Akbar, AN; Lawson, ADG. Activation of resting human primary T cells with chimeric receptors: costimulation from CD28, inducible costimulator, CD134, and CD137 in series with signals from the TCR zeta chain. J Immunol. 2004, 172, 104–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, DG; Ye, Q; Poussin, M; Harms, GM; Figini, M; Powell, DJ, Jr. CD27 costimulation augments the survival and antitumor activity of redirected human T cells in vivo. Blood 2012, 119, 696–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercio, M; Orlando, D; Di Cecca, S; Sinibaldi, M; Boffa, I; Caruso, S; et al. CD28.OX40 co-stimulatory combination is associated with long in vivo persistence and high activity of CAR.CD30 T-cells. Haematologica 2021, 106, 987–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C; Xia, K; Xie, Y; Ye, S; Ding, Y; Liu, Z; et al. Combination of 4-1BB and DAP10 promotes proliferation and persistence of NKG2D(bbz) CAR-T cells. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 893124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y; Chen, Z; Sun, M; Li, B; Pan, F; Ma, A; et al. IL-12 nanochaperone-engineered CAR T cell for robust tumor-immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 281, 121341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avanzi, MP; Yeku, O; Li, X; Wijewarnasuriya, DP; van Leeuwen, DG; Cheung, K; et al. Engineered tumor-targeted T cells mediate enhanced anti-tumor efficacy both directly and through activation of the endogenous immune system. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 2130–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, M; Abken, H. CAR T cells releasing IL-18 convert to T-Bethigh FoxO1low effectors that exhibit augmented activity against advanced solid tumors. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obstfeld, AE; Frey, NV; Mansfield, K; Lacey, SF; June, CH; Porter, DL; et al. Cytokine release syndrome associated with chimeric-antigen receptor T-cell therapy: clinicopathological insights. Blood 2017, 130, 2569–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R; Jiang, S; Chen, Y; Ma, Y; Sun, L; Xing, C; et al. Prognostic significance of cytokine release syndrome in B cell hematological malignancies patients after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2021, 41, 469–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norelli, M; Camisa, B; Barbiera, G; Falcone, L; Purevdorj, A; Genua, M; et al. Monocyte-derived IL-1 and IL-6 are differentially required for cytokine-release syndrome and neurotoxicity due to CAR T cells. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 739–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C; Tian, S; Wang, J; Ma, H; Qian, K; Zhang, X. Co-expression of CD40/CD40L on XG1 multiple myeloma cells promotes IL-6 autocrine function. Cancer Invest. 2015, 33, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavridis, T; van der Stegen, SJC; Eyquem, J; Hamieh, M; Piersigilli, A; Sadelain, M. CAR T cell-induced cytokine release syndrome is mediated by macrophages and abated by IL-1 blockade. Nat Med. 2018, 24, 731–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P; Cron, RQ; Hartwell, J; Manson, JJ; Tattersall, RS. Silencing the cytokine storm: the use of intravenous anakinra in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or macrophage activation syndrome. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020, 2, e358–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P; Zhou, L; Ye, S; Zhang, W; Wang, J; Tang, X; et al. Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection receiving anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy without antiviral prophylaxis. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 638678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J; Zhao, J; Han, M; Meng, F; Zhou, J. SARS-CoV-2 infection in immunocompromised patients: humoral versus cell-mediated immunity. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Haas, PA; Young, RD. Attention styles of hyperactive and normal girls. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1984, 12, 531–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, FA; Bernstein, IL; Khan, DA; Ballas, ZK; Chinen, J; Frank, MM; et al. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005, 94, S1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapel, H; Cunningham-Rundles, C. Update in understanding common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVIDs) and the management of patients with these conditions. Br J Haematol. 2009, 145, 709–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, JH; Romero, FA; Taur, Y; Sadelain, M; Brentjens, RJ; Hohl, TM; et al. Cytokine release syndrome grade as a predictive marker for infections in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Clin Infect Dis. 2018, 67, 533–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, JWY; Law, AWH; Law, KWT; Ho, R; Cheung, CKM; Law, MF. Prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with hematological malignancies in the targeted therapy era. World J Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 4942–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J; Zhu, X; Mao, X; Huang, L; Meng, F; Zhou, J. Severe early hepatitis B reactivation in a patient receiving anti-CD19 and anti-CD22 CAR T cells for the treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Immunother Cancer 2019, 7, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H; Iqbal, M; Chavez, JC; Kharfan-Dabaja, MA. Cytokine release syndrome: current perspectives. Immunotargets Ther. 2019, 8, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsrud, A; Craig, J; Baird, J; Spiegel, J; Muffly, L; Zehnder, J; et al. Incidence and risk factors associated with bleeding and thrombosis following chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 4465–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y; Qi, K; Cheng, H; Cao, J; Shi, M; Qiao, J; et al. Coagulation disorders after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy: analysis of 100 patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020, 26, 865–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M; Yu, Q; Teng, X; Guo, X; Wei, G; Xu, H; et al. CRS-related coagulopathy in BCMA targeted CAR-T therapy: a retrospective analysis in a phase I/II clinical trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 1642–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroudi, I; Papadaki, V; Pyrovolaki, K; Katonis, P; Eliopoulos, AG; Papadaki, HA. The CD40/CD40 ligand interactions exert pleiotropic effects on bone marrow granulopoiesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2011, 89, 771–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L; Wang, Y; Liu, H; Gao, S; Shao, Q; Yue, L; et al. Case report: sirolimus alleviates persistent cytopenia after CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 798352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, R; Graham, C; Yallop, D; Jozwik, AC; Mirci-Danicar, OC; Lucchini, G; et al. Genome-edited, donor-derived allogeneic anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells in paediatric and adult B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results of two phase 1 studies. Lancet 2020, 396, 1885–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J; Tang, K; Luo, Y; Seery, S; Tan, Y; Deng, B; et al. Sequential CD19 and CD22 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for childhood refractory or relapsed B-cell acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 1229–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, NN; Fry, TJ. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019, 16, 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X; Sun, Q; Liang, X; Chen, Z; Zhang, X; Zhou, X; et al. Mechanisms of relapse after CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its prevention and treatment strategies. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, L. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for pediatric B-ALL: narrowing the gap between early and long-term outcomes. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, AB; Newman, H; Li, Y; Liu, H; Myers, R; DiNofia, A; et al. CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for CNS relapsed or refractory acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a post-hoc analysis of pooled data from five clinical trials. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e711–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, PJ; Roddie, C; Bader, P; Basak, GW; Bonig, H; Bonini, C; et al. Management of adults and children receiving CAR T-cell therapy: 2021 best practice recommendations of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and the Joint Accreditation Committee of ISCT and EBMT (JACIE) and the European Haematology Association (EHA). Ann Oncol. 2022, 33, 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, T; Radhakrishnan, R; Sakshi, S; Martin, S. CAR γδ T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Is the field more yellow than green? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023, 72, 277–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, HR; Mirzaei, H; Lee, SY; Hadjati, J; Till, BG. Prospects for chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) γδ T cells: a potential game changer for adoptive T cell cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2016, 380, 413–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S; Deng, B; Yin, Z; Lin, Y; An, L; Liu, D; et al. Combination of CD19 and CD22 CAR-T cell therapy in relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia after allogeneic transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2021, 96, 671–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H; Wu, Z; Jia, H; Tong, C; Guo, Y; Ti, D; et al. Bispecific CAR-T cells targeting both CD19 and CD22 for therapy of adults with relapsed or refractory B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2020, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W; Ding, L; Shi, W; Wan, X; Yang, X; Yang, J; et al. Safety and efficacy of co-administration of CD19 and CD22 CAR-T cells in children with B-ALL relapse after CD19 CAR-T therapy. J Transl Med. 2023, 21, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gust, J; Hay, KA; Hanafi, LA; Li, D; Myerson, D; Gonzalez-Cuyar, LF; et al. Endothelial activation and blood-brain barrier disruption in neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T cells. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1404–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, DW; Santomasso, BD; Locke, FL; Ghobadi, A; Turtle, CJ; Brudno, JN; et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 625–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelapu, SS; Tummala, S; Kebriaei, P; Wierda, W; Gutierrez, C; Locke, FL; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018, 15, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santomasso, BD; Park, JH; Salloum, D; Riviere, I; Flynn, J; Mead, E; et al. Clinical and biological correlates of neurotoxicity associated with CAR T-cell therapy in patients with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 958–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, DB; Danish, HH; Ali, AB; Li, K; LaRose, S; Monk, AD; et al. Neurological toxicities associated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Brain 2019, 142, 1334–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudno, JN; Kochenderfer, JN. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: recognition and management. Blood 2016, 127, 3321–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupp, SA; Kalos, M; Barrett, D; Aplenc, R; Porter, DL; Rheingold, SR; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013, 368, 1509–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, KA; Hanafi, LA; Li, D; Gust, J; Liles, WC; Wurfel, MM; et al. Kinetics and biomarkers of severe cytokine release syndrome after CD19 chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy. Blood 2017, 130, 2295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, DW; Gardner, R; Porter, DL; Louis, CU; Ahmed, N; Jensen, M; et al. Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 2014, 124, 188–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachey, DT; Lacey, SF; Shaw, PA; Melenhorst, JJ; Maude, SL; Frey, N; et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 664–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karschnia, P; Jordan, JT; Forst, DA; Arrillaga-Romany, IC; Batchelor, TT; Baehring, JM; et al. Clinical presentation, management, and biomarkers of neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CAR T cells. Blood 2019, 133, 2212–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, NV; Shaw, PA; Hexner, EO; Pequignot, E; Gill, S; Luger, SM; et al. Optimizing chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2020, 38, 415–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S. Overview of immunosuppressive therapy in solid organ transplantation. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019, 94, 1975–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruetzmann, S; Rosado, MM; Weber, H; Germing, U; Tournilhac, O; Peter, HH; et al. Human immunoglobulin M memory B cells controlling Streptococcus pneumoniae infections are generated in the spleen. J Exp Med. 2003, 197, 939–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S; Patel, P. Approach to immunodeficiency diseases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020, 95, 544–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Author Index. Vox Sang. 2011, 101, 135–42. [CrossRef]

- Panitsas, FP; Theodoropoulou, M; Kouraklis, A; Karakantza, M; Theodorou, GL; Zoumbos, NC; et al. Adult chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is the manifestation of a type-1 polarized immune response. Blood 2004, 103, 2645–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, TJ; Bohlke, K; Lyman, GH; Carson, KR; Crawford, J; Cross, SJ; et al. Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2015, 33, 3199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtle, CJ; Hanafi, LA; Berger, C; Gooley, TA; Cherian, S; Hudecek, M; et al. CD19 CAR-T cells of defined CD4+:CD8+ composition in adult B cell ALL patients. J Clin Invest. 2016, 126, 2123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penack, O; Holler, E; van den Brink, MRM. Graft-versus-host disease: regulation by microbe-associated molecules and innate immune receptors. Blood 2010, 115, 1865–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malard, F; Mohty, M. Updates in chronic graft-versus-host disease management. Am J Hematol. 2023, 98, 1637–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maude, SL; Laetsch, TW; Buechner, J; Rives, S; Boyer, M; Bittencourt, H; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 439–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, AD; Garfall, AL; Stadtmauer, EA; Lacey, SF; Lancaster, E; Vogl, DT; et al. B cell maturation antigen-specific CAR T cells are clinically active in multiple myeloma. J Clin Invest. 2019, 129, 2210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, JN; Maric, I; Hartman, SD; Rose, JJ; Wang, M; Lam, N; et al. T cells genetically modified to express an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor cause remissions of poor-prognosis relapsed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2018, 36, 2267–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, SJ; Bishop, MR; Tam, CS; Waller, EK; Borchmann, P; McGuirk, JP; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, NC; Anderson, LD, Jr.; Shah, N; Madduri, D; Berdeja, J; Lonial, S; et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021, 384, 705–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N; Berdeja, J; Lin, Y; Siegel, D; Jagannath, S; Madduri, D; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb21217 in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: updated results of a multicenter phase I CRB-402 study. Blood 2019, 134, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKean, M; Carabasi, MH; Stein, MN; Schweizer, MT; Luke, JJ; Narayan, V; et al. Safety and early efficacy results from a phase 1, multicenter trial of PSMA-targeted armored CAR T cells in patients with advanced mCRPC. J Clin Oncol. 2022, 40, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A; Siegler, EL; Kenderian, SS. CART Cell Toxicities: New Insight into Mechanisms and Management. Clin Hematol Int. 2020, 2(4), 149–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V; Barber-Rotenberg, JS; Jung, IY; Lacey, SF; Rech, AJ; Davis, MM; et al. PSMA-targeting TGFβ-insensitive armored CAR T cells in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2022, 28(4), 724–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serganova, I; Moroz, E; Cohen, I; Moroz, M; Mane, M; Zurita, J; et al. Enhancement of PSMA-Directed CAR Adoptive Immunotherapy by PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2016, 4, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauri, C; Chiurchioni, L; Russo, VM; Zannini, L; Signore, A. PSMA Expression in Solid Tumors beyond the Prostate Gland: Ready for Theranostic Applications? J Clin Med. 2022, 11(21), 6590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, JH; Choi, BD; Sanchez-Perez, L; Suryadevara, CM; Snyder, DJ; Flores, CT; et al. EGFRvIII mCAR-modified T-cell therapy cures mice with established intracerebral glioma and generates host immunity against tumor-antigen loss. Clin Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 972–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, DM; Nasrallah, MP; Desai, A; Melenhorst, JJ; Mansfield, K; Morrissette, JJD; et al. A single dose of peripherally infused EGFRvIII-directed CAR T cells mediates antigen loss and induces adaptive resistance in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Sci Transl Med. 2017, 9, eaaa0984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, AD, Jr.; Schwab, RD; Boesteanu, AC; Steentoft, C; Mandel, U; Engels, B; et al. Engineered CAR T cells targeting the cancer-associated Tn-glycoform of the membrane mucin MUC1 control adenocarcinoma. Immunity 2016, 44, 1444–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R; Yazdanifar, M; Roy, LD; Whilding, LM; Gavrill, A; Maher, J; et al. CAR T cells targeting the tumor MUC1 glycoprotein reduce triple-negative breast cancer growth. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, GL; O’Hara, MH; Lacey, SF; Torigian, DA; Nazimuddin, F; Chen, F; et al. Activity of mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells against pancreatic carcinoma metastases in a phase 1 trial. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adusumilli, PS; Cherkassky, L; Villena-Vargas, J; Colovos, C; Servais, E; Plotkin, J; et al. Regional delivery of mesothelin-targeted CAR T cell therapy generates potent and long-lasting CD4-dependent tumor immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2014, 6, 261ra151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddie, C; O’Reilly, M; Dias Alves Pinto, J; Vispute, K; Lowdell, M. Manufacturing chimeric antigen receptor T cells: issues and challenges. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 327–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelapu, SS; Nath, R; Munoz, J; Tees, M; Miklos, DB; Frank, MJ; et al. ALPHA study: ALLO-501 produced deep and durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma comparable to autologous CAR T. Blood 2021, 138, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, NN; Fry, TJ. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019, 16, 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, FL; Malik, S; Tees, MT; Neelapu, SS; Popplewell, L; Abramson, JS; et al. First-in-human data of ALLO-501A, an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy and ALLO-647 in relapsed/refractory large B-cell lymphoma (R/R LBCL): ALPHA2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2021, 39, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raje, N; Berdeja, J; Lin, Y; Siegel, D; Jagannath, S; Madduri, D; et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019, 380, 1726–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailankody, S; Htut, M; Lee, KP; Bensinger, W; Devries, T; Piasecki, J; et al. JCARH125, anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: initial proof of concept results from a phase 1/2 multicenter study (EVOLVE). Blood 2018, 132, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, HN. B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) as a target for new drug development in relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S; Jin, J; Jiang, S; Li, Z; Zhang, W; Yang, M; et al. Two-year follow-up of investigator-initiated phase 1 trials of the safety and efficacy of fully human anti-BCMA CAR T cells (CT053) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2020, 136, 27–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, MJ; Baird, JH; Kramer, AM; Srinagesh, HK; Patel, S; Brown, AK; et al. CD22-directed CAR T-cell therapy for large B-cell lymphomas progressing after CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy: a dose-finding phase 1 study. Lancet 2024, 404, 353–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinagesh, HK; Jackson, C; Shiraz, P; Jeyakumar, N; Hamilton, MP; Egeler, E; et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of NKTR-255 with CD19-22 CAR-T cell therapy for refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X; Cao, Z; Chen, Z; Wang, Y; He, H; Xiao, P; et al. Infectious complications in pediatric patients undergoing CD19+CD22+ chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for relapsed/refractory B-lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Exp Med. 2024, 24, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X; Sun, X; Deng, W; Xu, R; Zhao, Q. Combination therapy of targeting CD20 antibody and immune checkpoint inhibitor may be a breakthrough in the treatment of B-cell lymphoma. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F; Zheng, P; Yang, F; Liu, R; Feng, S; Guo, Y; et al. Salvage CD20-SD-CART therapy in aggressive B-cell lymphoma after CD19 CART treatment failure. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1376490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, HS; Ahmad, FN; Achmad, H; Ansari, MJ; Mikhailova, MV; Suksatan, W; et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) for tumor immunotherapy; recent progress. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022, 13(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabaneh, TB; Stevens, AR; Stull, SM; Shimp, KR; Seaton, BW; Gad, EA; et al. Systemically administered low-affinity HER2 CAR T cells mediate antitumor efficacy without toxicity. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12(2), e008566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G; Fu, S; Zhang, Y; Li, S; Guo, Z; Ouyang, D; et al. Antibody recognition of human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) juxtamembrane domain enhances anti-tumor response of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells. Antibodies 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, F; Quintarelli, C. GD2 target antigen and CAR T cells: does it take more than two to tango? Clin Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3361–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargett, T; Truong, NT; Gardam, B; Yu, W; Ebert, LM; Johnson, A; et al. Safety and biological outcomes following a phase 1 trial of GD2-specific CAR-T cells in patients with GD2-positive metastatic melanoma and other solid cancers. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12, e008659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S; Ishii, M; Ando, J; Kimura, T; Yamaguchi, T; Harada, S; et al. Rejuvenated iPSC-derived GD2-directed CART cells harbor robust cytotoxicity against small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res Commun. 2024, 4, 723–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L; Li, Y; Zheng, D; Zheng, Y; Cui, Y; Qin, L; et al. Bispecific CAR-T cells targeting FAP and GPC3 have the potential to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2024, 32, 200817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X; Liu, X; Lei, Y; Wang, G; Liu, M. Glypican-3: a novel and promising target for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 824208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G; Zhang, G; Liu, M; Liu, J; Wang, Q; Zhu, L; et al. GPC3-targeted CAR-T cells secreting B7H3-targeted BiTE exhibit potent cytotoxicity activity against hepatocellular carcinoma cell in the in vitro assay. Biochem Biophys Res. 2022, 31, 101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, MV; Roberts, SS; Glade Bender, J; Shukla, N; Wexler, LH. Immunotherapeutic targeting of GPC3 in pediatric solid embryonal tumors. Front Oncol. 2019, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L; Chen, GL; Xiang, Z; Liu, YL; Li, XY; Bi, JW; et al. Current progress in chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023, 162, 114648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S; Li, M; Qin, L; Lv, J; Wu, D; Zheng, D; et al. The onco-embryonic antigen ROR1 is a target of chimeric antigen T cells for colorectal cancer. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023, 121, 110402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, TM; Chand Thakuri, BK; Nurmukhambetova, S; Lee, JJ; Hu, P; Tran, NQ; et al. Armored TGFβRIIDN ROR1-CAR T cells reject solid tumors and resist suppression by constitutively-expressed and treatment-induced TGFβ1. J Immunother Cancer 2024, 12, e008261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Xu, Y; Xiong, W; Yin, B; Huang, Y; Chu, J; et al. Development of a TCR-like antibody and chimeric antigen receptor against NY-ESO-1/HLA-A2 for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2022, 10, e004035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochigneux, P; Chanez, B; De Rauglaudre, B; Mitry, E; Chabannon, C; Gilabert, M. Adoptive cell therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: biological rationale and first results in early phase clinical trials. Cancers 2021, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Q; He, B; Deng, S; Zeng, Q; Xu, Y; Wang, C; et al. Efficacy of NKG2D CAR-T cells with IL-15/IL-15Rα signaling for treating Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2024, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D; Dou, L; Sui, L; Xue, Y; Xu, S. Natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. MedComm 2024, 5, e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, MB; Domaica, CI; Zwirner, NW. Leveraging NKG2D ligands in immuno-oncology. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 713158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Zhang, C; He, M; Xing, W; Hou, R; Zhang, H. Co-expression of IL-21-enhanced NKG2D CAR-NK cell therapy for lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Navarro, M; Fernández, A; Escudero, A; Esteso, G; Campos-Silva, C; Navarro-Aguadero, MÁ; et al. NKG2D-CAR memory T cells target pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in vitro and in vivo but fail to eliminate leukemia initiating cells. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1187665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallis, RJ; Brazin, KN; Duke-Cohan, JS; Hwang, W; Wang, JH; Wagner, G; et al. NMR: an essential structural tool for integrative studies of T cell development, pMHC ligand recognition and TCR mechanobiology. J Biomol NMR 2019, 73, 319–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A; Bennychen, B; Ahmed, Z; Weeratna, RD; McComb, S. A flow cytometry-based method for assessing CAR cell binding kinetics using stable CAR Jurkat cells. Bio-protocol 2024, 14, e5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, B; McBlane, F; Spindeldreher, S; Sickert, D. A cell-based immunogenicity assay to detect antibodies against chimeric antigen receptor expressed by tisagenlecleucel. J Immunol Methods 2020, 476, 112692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z; Wang, J; Zhao, Y; Jin, J; Si, W; Chen, L; et al. 3D live imaging and phenotyping of CAR-T cell mediated-cytotoxicity using high-throughput Bessel oblique plane microscopy. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorai, SK; Pearson, AN. Current strategies to improve chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell persistence. Cureus 2024, 16, e65291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappell, KM; Kochenderfer, JN. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023, 20, 359–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S; Riddell, SR. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy: challenges to bench-to-bedside efficacy. J Immunol. 2018, 200, 459–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S; Wang, X; Wang, Y; Wang, Y; Fang, C; Wang, Y; et al. Deciphering and advancing CAR T-cell therapy with single-cell sequencing technologies. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, X; Xiao, L; Brown, CE; Wang, D. Preclinical evaluation of CAR T cell function: in vitro and in vivo models. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort, S; Herbst, L; Bäckel, N; Erkens, F; Niessing, B; Frye, M; et al. Toward rapid, widely available autologous CAR-T cell therapy—artificial intelligence and automation enabling the smart manufacturing hospital. Front Med. 2022, 9, 913287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portale, F; Di Mitri, D. NK Cells in Cancer: Mechanisms of Dysfunction and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(11), 9521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. The Function of NK Cells in Tumor Metastasis and NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Cancers 2023, 15(8), 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y; Cheng, L; Liu, L; Li, X. NK cells are never alone: crosstalk and communication in tumour microenvironments. Mol Cancer 2023, 22(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W; Liu, Y; He, Z; Li, L; Liu, S; Jiang, M; et al. Breakthrough of solid tumor treatment: CAR-NK immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uscanga-Palomeque, AC; Chávez-Escamilla, AK; Alvizo-Báez, CA; Saavedra-Alonso, S; Terrazas-Armendáriz, LD; Tamez-Guerra, RS; et al. CAR-T Cell Therapy: From the Shop to Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(21), 15688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T; Niu, M; Zhang, W; Qin, S; Zhou, J; Yi, M. CAR-NK cells for cancer immunotherapy: recent advances and future directions. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1361194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiri Dezfouli, A; Yazdi, M; Pockley, AG; Khosravi, M; Kobold, S; Wagner, E; et al. NK Cells Armed with Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CAR): Roadblocks to Successful Development. Cells 2021, 10(12), 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, M; Melo Garcia, L; Li, Y; Rezvani, K. CAR-NK cells: the next wave of cellular therapy for cancer. Clin Transl Immunol. 2021, 10(4), e1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H; Song, W; Li, Z; Zhang, M. Preclinical and clinical studies of CAR-NK-cell therapies for malignancies. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 992232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, JC; Sa’ad, MA; Vijayan, HM; Ravichandran, M; Balakrishnan, V; Tham, SK; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer cell therapy: current advancements and strategies to overcome challenges. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1384039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S; Caligiuri, MA; Yu, J. Harnessing IL-15 signaling to potentiate NK cell-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43(10), 833–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D; Ebrahimabadi, S; Gomes, KRS; de Moura Aguiar, G; Cariati Tirapelle, M; Nacasaki Silvestre, R; et al. Engineering CAR-NK cells: how to tune innate killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. Immunother Adv. 2022, 2(1), ltac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matosevic, S. Viral and Nonviral Engineering of Natural Killer Cells as Emerging Adoptive Cancer Immunotherapies. J Immunol Res. 2018, 2018, 4054815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R; Pupovac, A; Evtimov, V; Boyd, N; Shu, R; Boyd, R; et al. Enhancing a Natural Killer: Modification of NK Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2021, 10(5), 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarannum, M; Romee, R; Shapiro, RM. Innovative Strategies to Improve the Clinical Application of NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 859177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C; Liu, Y; Ali, NM; Zhang, B; Cui, X. The role of innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment and research progress in anti-tumor therapy. Front Immunol. 2023, 13, 1039260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y; Liu, J. Emerging roles of CAR-NK cell therapies in tumor immunotherapy: current status and future directions. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10(1), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H; Zhao, X; Li, Z; Hu, Y; Wang, H. From CAR-T Cells to CAR-NK Cells: A Developing Immunotherapy Method for Hematological Malignancies. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 720501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W; Wang, X; Zhang, X; Aziz, AuR; Wang, D. CAR-NK Cell Therapy: A Transformative Approach to Overcoming Oncological Challenges. Biomolecules 2024, 14(8), 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, A; Salehi, A; Khosravi, S; Shariati, Y; Nasrabadi, N; Kahrizi, MS; et al. Recent findings on chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered immune cell therapy in solid tumors and hematological malignancies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022, 13(1), 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F; Fredericks, N; Snowden, A; Allegrezza, MJ; Moreno-Nieves, UY. Next Generation Natural Killer Cells for Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 886429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares, J; Davis, ZB; Rechberger, JS; Toll, SA; Schwartz, JD; Daniels, DJ; et al. Advances in NK cell therapy for brain tumors. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2023, 7(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y; Liu, J. Emerging roles of CAR-NK cell therapies in tumor immunotherapy: current status and future directions. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10(1), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, A; García-Ortiz, A; Castellano, E; Córdoba, L; Maroto-Martín, E; Encinas, J; et al. Overcoming tumor resistance mechanisms in CAR-NK cell therapy. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 953849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W; Liu, Y; He, Z; Li, L; Liu, S; Jiang, M; et al. Breakthrough of solid tumor treatment: CAR-NK immunotherapy. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J; Hu, H; Lian, K; Zhang, D; Hu, P; He, Z; et al. CAR-NK cells in combination therapy against cancer: A potential paradigm. Heliyon 2024, 10(5), e27196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, KS; Alsahli, MA; Almatroudi, A; Alrumaihi, F; Al Abdulmonem, W; Moawad, AA; et al. Innovative Strategies of Reprogramming Immune System Cells by Targeting CRISPR/Cas9-Based Genome-Editing Tools: A New Era of Cancer Management. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 5531–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z; Luo, F; Chu, Y. Strategies for overcoming bottlenecks in allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1199145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C; Zhang, Y. Potential alternatives to αβ-T cells to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) in allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-based cancer immunotherapy: A comprehensive review. Pathol Res Pract. 2024, 262, 155518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanifar, M; Barbarito, G; Bertaina, A; Airoldi, I. γδ T Cells: The Ideal Tool for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2020, 9(5), 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonez, C; Breman, E. Allogeneic CAR-T Therapy Technologies: Has the Promise Been Met? Cells 2024, 13(2), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, KJ; Gottschalk, S; Talleur, AC. Allogeneic CAR Cell Therapy-More Than a Pipe Dream. Front Immunol. 2021, 11, 618427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P; Zhang, Q; Xu, Z; Shi, Y; Jing, R; Luo, D. CRISPR/Cas-based CAR-T cells: production and application. Biomark Res. 2024, 12(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, AN; Tian, G; Metelitsa, LS. Natural killer T cells and other innate-like T lymphocytes as emerging platforms for allogeneic cancer cell therapy. Blood 2023, 141(8), 869–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillhouse, EE; Delisle, JS; Lesage, S. Immunoregulatory CD4(-)CD8(-) T cells as a potential therapeutic tool for transplantation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Front Immunol. 2013, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z; Zheng, Y; Sheng, J; Han, Y; Yang, Y; Pan, H; et al. CD3+CD4-CD8- (Double-Negative) T Cells in Inflammation, Immune Disorders and Cancer. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 816005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, XC; Sun, KN; Zhu, HR; Dai, YL; Liu, XF. Diagnostic and prognostic value of double-negative T cells in colorectal cancer. Heliyon 2024, 10(14), e34645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W; Chen, ZN; Wang, K. CRISPR/Cas9: A Powerful Strategy to Improve CAR-T Cell Persistence. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(15), 12317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezalotfi, A; Fritz, L; Förster, R; Bošnjak, B. Challenges of CRISPR-Based Gene Editing in Primary T Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(3), 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P; Zhang, G; Wan, X. Challenges and new technologies in adoptive cell therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2023, 16(1), 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiloo, K; Tahmasebi, S; Esmaeilzadeh, A. CAR-NKT cell therapy: a new promising paradigm of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23(1), 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shissler, SC; Bollino, DR; Tiper, IV; Bates, JP; Derakhshandeh, R; Webb, TJ. Immunotherapeutic strategies targeting natural killer T cell responses in cancer. Immunogenetics 2016, 68(8), 623–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y; Wang, G; Chai, D; Dang, Y; Zheng, J; Li, H. iNKT: A new avenue for CAR-based cancer immunotherapy. Transl Oncol. 2022, 17, 101342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, SI; Shimizu, K. Exploiting Antitumor Immunotherapeutic Novel Strategies by Deciphering the Cross Talk between Invariant NKT Cells and Dendritic Cells. Front Immunol. 2017, 8, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z; Zheng, Y; Sheng, J; Han, Y; Yang, Y; Pan, H; et al. CD3+CD4-CD8- (Double-Negative) T Cells in Inflammation, Immune Disorders and Cancer. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 816005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K; Voelkl, S; Heymann, J; Przybylski, GK; Mondal, K; Laumer, M; et al. Isolation and characterization of human antigen-specific TCR alpha beta+ CD4(-)CD8- double-negative regulatory T cells. Blood 2005, 105(7), 2828–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, D; Hedrich, CM. TCRαβ+CD3+CD4-CD8- (double negative) T cells in autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2018, 17(4), 422–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H; Chang, Y; Zhao, X; Huang, X. Characterization of CD3+CD4-CD8- (double negative) T cells reconstitution in patients following hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2011, 25(4), 180–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, D; Lee, JB; Leung, Y; Khatri, I; Na, Y; Abate-Daga, D; et al. Allogeneic double-negative CAR-T cells inhibit tumor growth without off-tumor toxicities. Sci Immunol. 2022, 7(70), eabl3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadiloo, K; Taremi, S; Heidari, M; Esmaeilzadeh, A. The CAR macrophage cells, a novel generation of chimeric antigen-based approach against solid tumors. Biomark Res. 2023, 11(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basak, U; Sarkar, T; Mukherjee, S; Chakraborty, S; Dutta, A; Dutta, S; et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: an effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1295257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N; Geng, S; Dong, ZZ; Jin, Y; Ying, H; Li, HW; et al. A new era of cancer immunotherapy: combining revolutionary technologies for enhanced CAR-M therapy. Mol Cancer 2024, 23(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, M; Heidari, S; Faridzadeh, A; Roozbehani, M; Toosi, S; Mahmoudian, RA; et al. Potential applications of macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K; Farrukh, H; Chittepu, VCSR; Xu, H; Pan, CX; Zhu, Z. CAR race to cancer immunotherapy: from CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022, 41(1), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T; Lu, Y; Fang, J; Jiang, X; Lu, Y; Zheng, J; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-based immunotherapy in breast cancer: Recent progress in China. Cancer 2024, 130(S8), 1378–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X; Fan, J; Xie, W; Wu, X; Wei, J; He, Z; et al. Efficacy evaluation of chimeric antigen receptor-modified human peritoneal macrophages in the treatment of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer 2023, 129(3), 551–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K; Liu, ML; Wang, JC; Fang, S. CAR-macrophage versus CAR-T for solid tumors: The race between a rising star and a superstar. Biomol Biomed. 2024, 24(3), 465–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y; Cai, X; Syahirah, R; Yao, Y; Xu, Y; Jin, G; et al. CAR-neutrophil mediated delivery of tumor-microenvironment responsive nanodrugs for glioblastoma chemo-immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2023, 14(1), 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, JD; Chang, Y; Syahirah, R; Lian, XL; Deng, Q; Bao, X. Engineered anti-prostate cancer CAR-neutrophils from human pluripotent stem cells. J Immunol Regen Med. 2023, 20, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y; Syahirah, R; Wang, X; Jin, G; Torregrosa-Allen, S; Elzey, BD; et al. Engineering chimeric antigen receptor neutrophils from human pluripotent stem cells for targeted cancer immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2022, 40(3), 111128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, RP; Ghilardi, G; Zhang, Y; Chiang, YH; Xie, W; Guruprasad, P; et al. CD5 deletion enhances the antitumor activity of adoptive T cell therapies. Sci Immunol. 2024, 9(97), eadn6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z; Mu, W; Zhao, Y; Jia, X; Liu, J; Wei, Q; et al. The rational development of CD5-targeting biepitopic CARs with fully human heavy-chain-only antigen recognition domains. Mol Ther. 2021, 29(9), 2707–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z; Wang, H; D’Souza, C; Sun, S; Kostenko, L; Eckle, SB; et al. Mucosal-associated invariant T-cell activation and accumulation after in vivo infection depends on microbial riboflavin synthesis and co-stimulatory signals. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10(1), 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, YR; Wilson, M; Yang, L. Target tumor microenvironment by innate T cells. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 999549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengalroyen, MD. Current Perspectives and Challenges of MAIT Cell-Directed Therapy for Tuberculosis Infection. Pathogens 2023, 12(11), 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legoux, F; Salou, M; Lantz, O. MAIT Cell Development and Functions: the Microbial Connection. Immunity 2020, 53(4), 710–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, M; Karhan, E; Kozhaya, L; Placek, L; Chen, X; Yigit, M; et al. Engineering Human MAIT Cells with Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Cancer Immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2022, 209(8), 1523–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruixin, S.; Yifan, L.; Yansha, S.; Min, Z.; Yiwei, D.; Xiaoli, H.; Bizhi, S.; Hua, J.; Zonghai, L. Dual targeting chimeric antigen receptor cells enhance antitumour activity by overcoming T cell exhaustion in pancreatic cancer. In British journal of pharmacology; Advance online publication, 2024; Volume 10.1111/bph. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, M.; Shi, B.; Jiang, H.; Sun, R.; Li, Z. FAP-targeted CAR-T suppresses MDSCs recruitment to improve the antitumor efficacy of claudin18.2-targeted CAR-T against pancreatic cancer. Journal of translational medicine 2023, 21(1), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughda, R.; Dimou, P.; D’Souza, R.R.; Klampatsa, A. Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP)-Targeted CAR-T Cells: Launching an Attack on Tumor Stroma. ImmunoTargets and therapy 2021, 10, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F; Liu, H; Wang, Y; Li, Y; Han, S. Engineering macrophages and their derivatives: A new hope for antitumor therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloas, C; Gill, S; Klichinsky, M. Engineered CAR-Macrophages as Adoptive Immunotherapies for Solid Tumors. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 783305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, V; Jensen, G; Mai, S; Chen, SH; Pan, PY. Corrigendum: Analyzing One Cell at a TIME: Analysis of Myeloid Cell Contributions in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2021, 11, 645213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugel, S; De Sanctis, F; Mandruzzato, S; Bronte, V. Tumor-induced myeloid deviation: when myeloid-derived suppressor cells meet tumor-associated macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2015, 125(9), 3365–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, GJ; Vizler, C; Nagy, LI; Kitajka, K; Puskas, LG. Pro-Tumoral Inflammatory Myeloid Cells as Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2016, 17(11), 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarla, S; Gottschalk, S. CAR T Cells for Solid Tumors. Cancer J. 2014, 20, 151–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koneru, M; Purdon, TJ; Spriggs, D; Koneru, S; Brentjens, RJ. IL-12 secreting tumor-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells eradicate ovarian tumors in vivo. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4(3), e994446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X; Sandrine, IK; Yang, M; Tu, J; Yuan, X. MUC1 and MUC16: critical for immune modulation in cancer therapeutics. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1356913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smole, A; Benton, A; Poussin, MA; Eiva, MA; Mezzanotte, C; Camisa, B; et al. Expression of inducible factors reprograms CAR-T cells for enhanced function and safety. Cancer Cell. 2022, 40(12), 1470–87.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, A; Tahmasebi, S; Athari, SS. Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell therapy: Applications and challenges in treatment of allergy and asthma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koneru, M; O’Cearbhaill, R; Pendharkar, S; Spriggs, DR; Brentjens, RJ. A phase I clinical trial of adoptive T cell therapy using IL-12 secreting MUC-16 ecto directed chimeric antigen receptors for recurrent ovarian cancer. J Transl Med. 2015, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, AV; Glukhova, XA; Popova, OP; Beletsky, IP; Ivanov, AA. Contemporary Approaches to Immunotherapy of Solid Tumors. Cancers 2024, 16, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

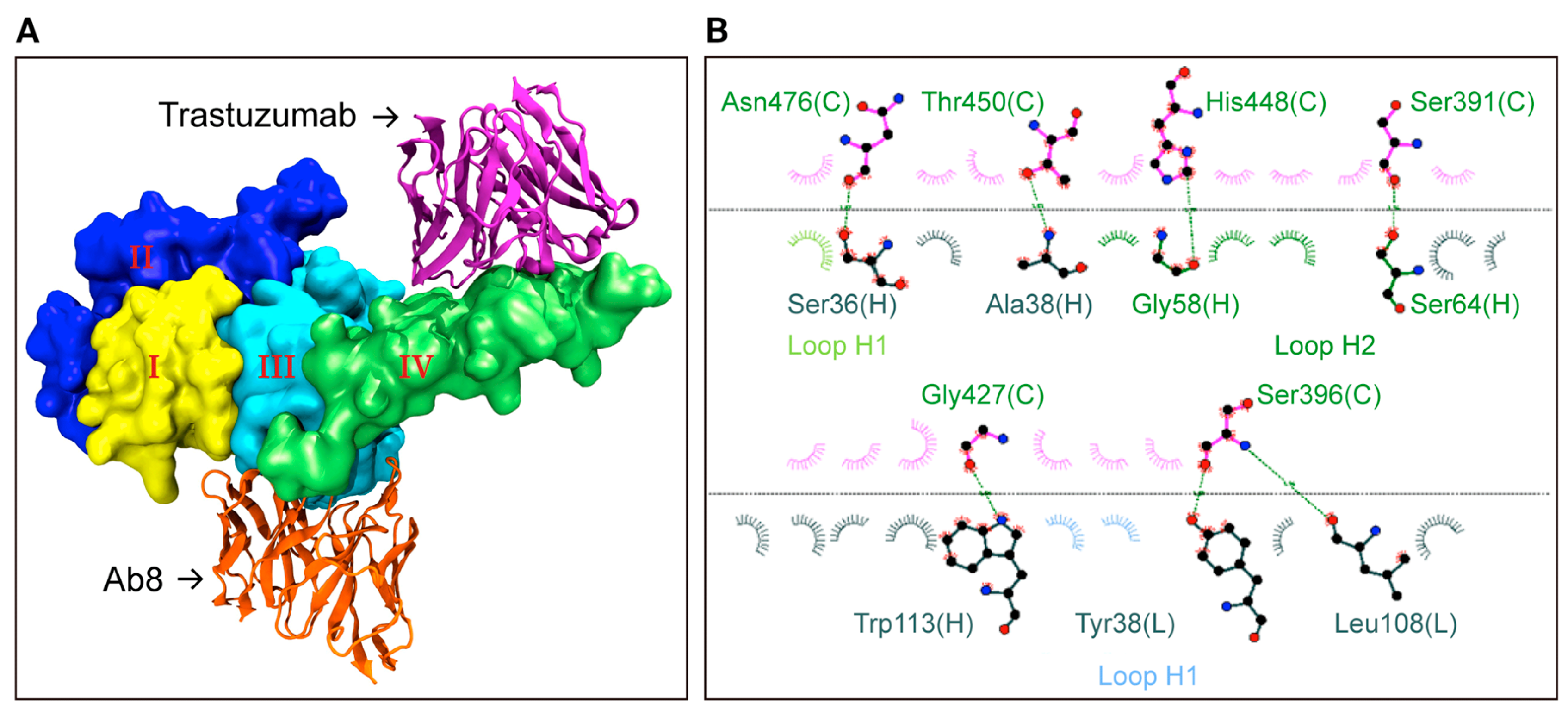

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Pandit, B.R.; Unakal, C.; Vuma, S.; Akpaka, P.E. A Comprehensive Review About the Use of Monoclonal Antibodies in Cancer Therapy. Antibodies 2025, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justiz-Vaillant, A.; Gopaul, D.; Soodeen, S.; Unakal, C.; Thompson, R.; Pooransingh, S.; Arozarena-Fundora, R.; Asin-Milan, O.; Akpaka, P.E. Advancements in Immunology and Microbiology Research: A Comprehensive Exploration of Key Areas. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CAR-T cell Therapy | Targeted antigen |

Cancer Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| bb21217 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Enhanced persistence CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

| CTL019 | CD19 | B-cell malignancies | Early version of Kymriah; basis for FDA-approved therapy |

| CART-PSMA | PSMA | Prostate cancer | Investigational CAR-T therapy; in early-phase trials |

| CAR-EGFRvIII | EGFRvIII | Glioblastoma | Investigational CAR-T therapy targeting specific EGFR mutation |

| Mesothelin-CAR-T | Mesothelin | Mesothelioma, ovarian cancer |

Experimental CAR-T therapy targeting mesothelin |

| MUC1-CAR-T | MUC1 | Various solid tumours |

Investigational CAR-T therapy for multiple epithelial cancers |

| ALLO-501 (Allogeneic) | CD19 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Allogeneic CAR-T therapy under investigation; uses donor-derived cells |

| JCARH125 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Experimental CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

| CT053 | BCMA | Multiple myeloma | Investigational CAR-T therapy; in clinical trials |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).