Submitted:

26 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

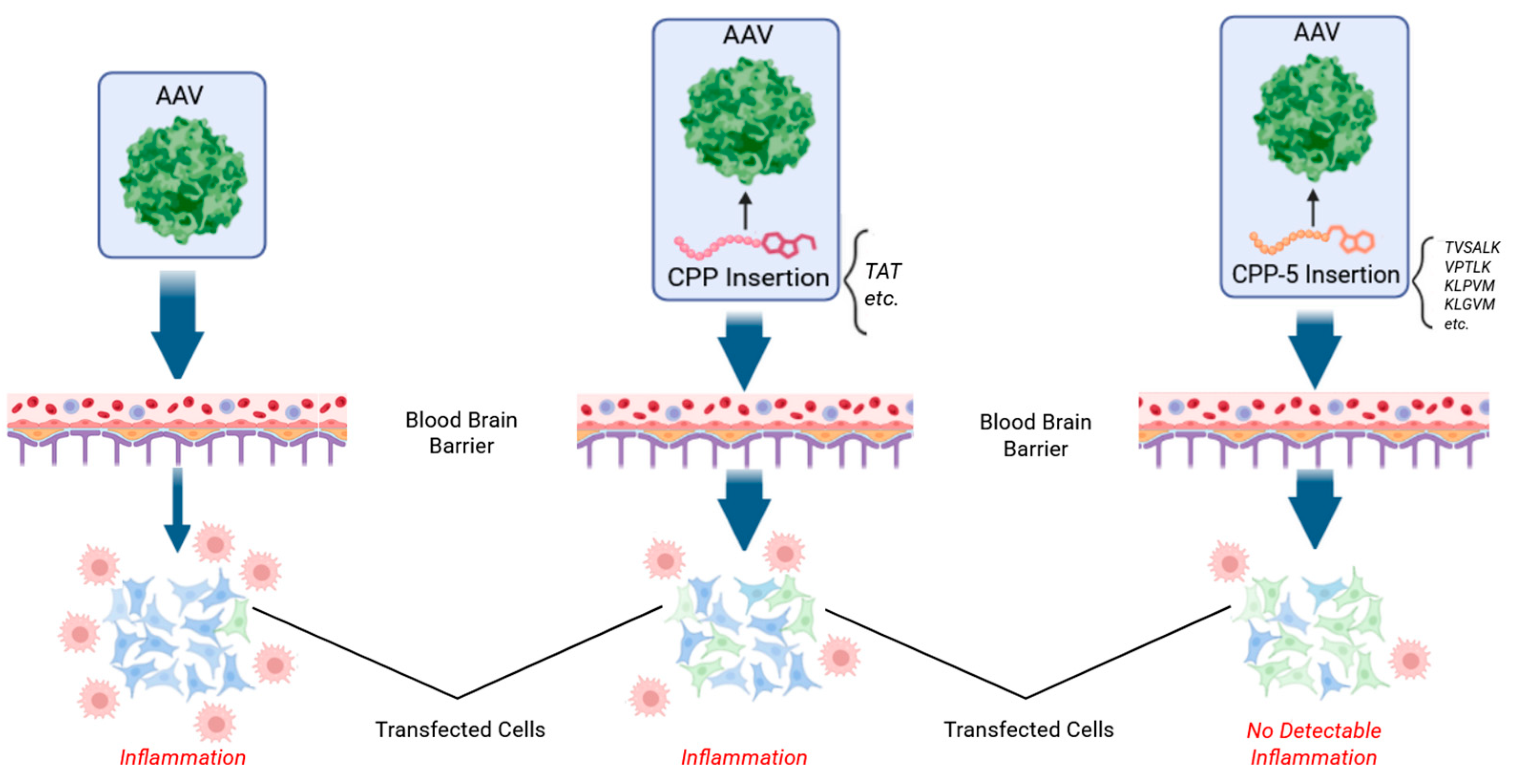

Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAVs) and nanoparticles have been used to deliver DNA or RNA to target cells for gene therapy technologies. These vectors are also useful for DNA- or RNA-based vaccines. Although AAVs and nanoparticles are promising technologies, two major technical problems remain. One problem is that the commonly used AAVs have a low efficiency to penetrate the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) and the blood-retina-barrier (BRB). Consequently, gene delivery to the nervous system has limitations. Another problem is that AAVs induce immune reactions that cause serious side effects. To avoid immune reactions, the AAV dose must be reduced to lower levels that may result in insufficient gene delivery. To overcome these problems, researchers searched for effective peptide sequences by modifying viral capsid proteins. As a result, Cell Penetrating Penta-Peptides (CPP5s) have been shown to be effective in improving the BBB/BRB penetration of AAV and the suppression immune reactions against AAV. CPP5s were originally developed from peptide sequences of Bax (a pro-apoptotic protein) binding domain of Ku70 (a DNA repair protein) and from negative control cell penetrating peptides without Bax-binding activity. This article will discuss the background science of CPP5 and the future direction of the use of CPP5 for AAV- and nanoparticle-mediated gene delivery to the nervous system as well as other organs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cell-Penetrating Penta-Peptides (CPP5s)

2.1. Background History of the Discovery and Invention of CPP5s

2.2. Mechanism of Cell Penetration of CPP5s

3. CPP5s Enhance AAV9 Delivery in the Brain of Mice and Non-Human Primates (Figure 1)

4. CPP5 Containing CPP.16 Enhances AAV Delivery in The Respiratory Tract

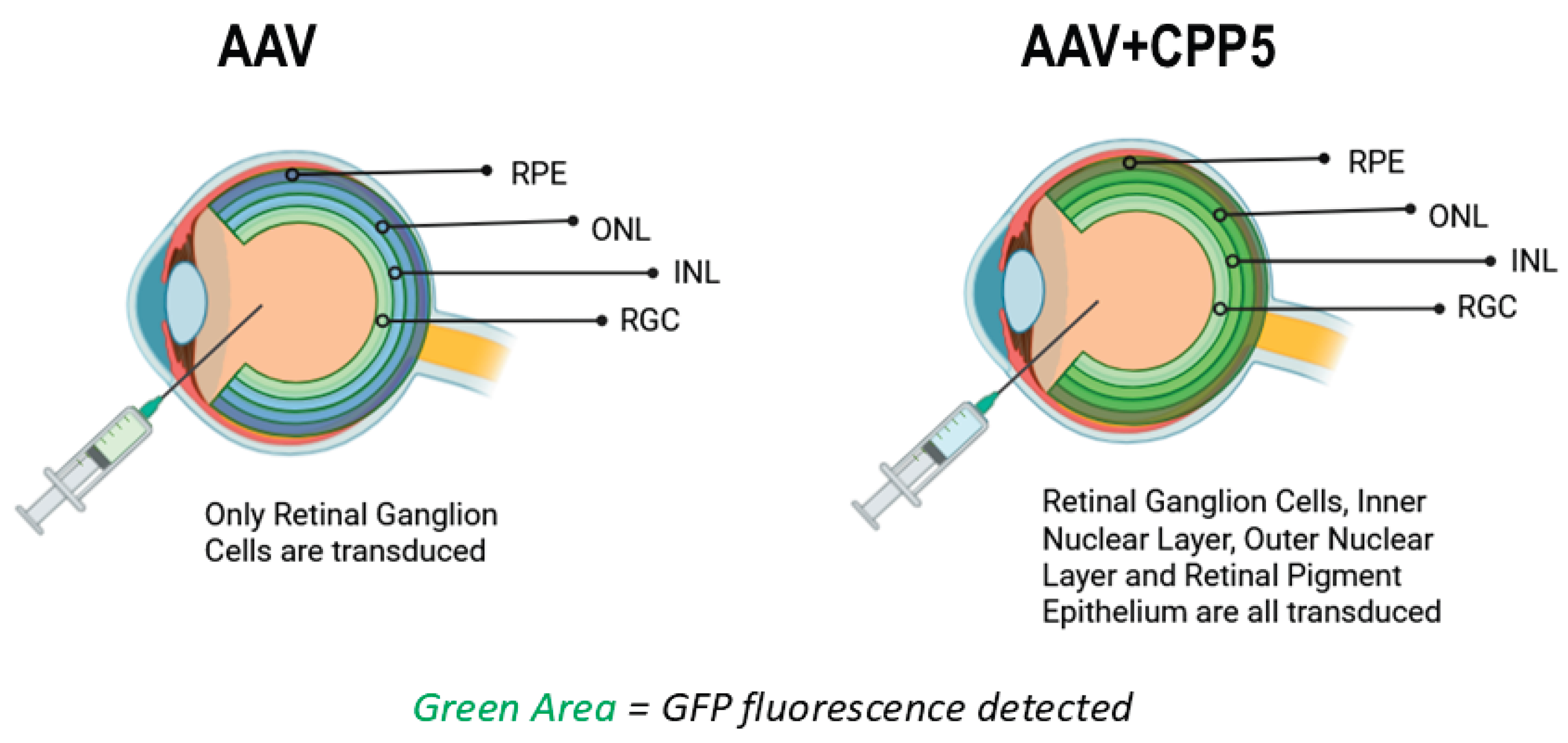

5. CPP5 Enhances AAV2 Delivery in the Retina (Figure 2)

6. Mechanisms of How CPP.16 and CPP.21 Helps AAV for Gene Delivery

7. KLGVM, a CPP5, Enhances AAV2 Delivery and Reduces Immunogenicity in the Retina (Figure 2)

8. Applications of CPP5s for Therapeutic Protein Delivery into Retinal Cells as Well as Other Cell Types

9. Summary and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPP5 | Cell penetrating penta-peptide |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| BBB | Blood brain barrier |

| BRB | Blood retina barrier |

| CPP | Cell-penetrating peptide |

| BIP | Bax inhibiting peptide |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

References

- Yoshida, T.; Tomioka, I.; Nagahara, T.; Holyst, T.; Sawada, M.; Hayes, P.; Gama, V.; Okuno, M.; Chen, Y.; Abe, Y.; et al. Bax-Inhibiting Peptide Derived from Mouse and Rat Ku70. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 321, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.A.; Gama, V.; Yoshida, T.; Sun, W.; Hayes, P.; Leskov, K.; Boothman, D.; Matsuyama, S. Bax-Inhibiting Peptides Derived from Ku70 and Cell-Penetrating Pentapeptides. Biochem Soc Trans 2007, 35, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.A.; Chen, J.; Ngo, J.; Hajkova, D.; Yeh, I.-J.; Gama, V.; Miyagi, M.; Matsuyama, S. Cell-Penetrating Penta-Peptides (CPP5s): Measurement of Cell Entry and Protein-Transduction Activity. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 3594–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, J.; Matsuyama, S. Cell-Penetrating Penta-Peptides and Bax-Inhibiting Peptides: Protocol for Their Application. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press, 2011; Vol. 683, pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Pupo, A.; Fernández, A.; Low, S.H.; François, A.; Suárez-Amarán, L.; Samulski, R.J. AAV Vectors: The Rubik’s Cube of Human Gene Therapy. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 3515–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell, J.R.; Al-Zaidy, S.A.; Rodino-Klapac, L.R.; Goodspeed, K.; Gray, S.J.; Kay, C.N.; Boye, S.L.; Boye, S.E.; George, L.A.; Salabarria, S.; et al. Current Clinical Applications of In Vivo Gene Therapy with AAVs. Molecular Therapy 2021, 29, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.J.; Flanigan, K.M.; Matesanz, S.E.; Finkel, R.S.; Waldrop, M.A.; D’Ambrosio, E.S.; Johnson, N.E.; Smith, B.K.; Bönnemann, C.; Carrig, S.; et al. Current Clinical Applications of AAV-Mediated Gene Therapy. Molecular Therapy 2025, 33, 2479–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Li, T.; Liu, L.; Che, X.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Wu, G. Adeno-Associated Virus Therapies: Pioneering Solutions for Human Genetic Diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2024, 80, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, H.; Khan, A.; Khan, K.; Toheed, S.; Abdullah, M.; Zeeshan, H.M.; Hameed, A.; Umar, M.; Shahid, M.; Malik, K.; et al. Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Gene Therapy. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2023, 33, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Xiao, S.; Liang, X.; Li, Y.; Mo, F.; Xin, X.; Yang, Y.; Gao, C. Adeno-Associated Virus Engineering and Load Strategy for Tropism Modification, Immune Evasion and Enhanced Transgene Expression. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, Volume 19, 7691–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merkel, S.F.; Andrews, A.M.; Lutton, E.M.; Mu, D.; Hudry, E.; Hyman, B.T.; Maguire, C.A.; Ramirez, S.H. Trafficking of Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors across a Model of the Blood-Brain Barrier; a Comparative Study of Transcytosis and Transduction Using Primary Human Brain Endothelial Cells. J Neurochem 2017, 140, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, M.S. AAV-Mediated Liver-Directed Gene Therapy. In; 2012; pp. 141–157.

- Rabinowitz, J.; Chan, Y.K.; Samulski, R.J. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Versus Immune Response. Viruses 2019, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.; Scheideler, O.; Schaffer, D. Engineering the AAV Capsid to Evade Immune Responses. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2019, 60, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton-Clark, H.; Yokota, T. Safety Concerns Surrounding AAV and CRISPR Therapies in Neuromuscular Treatment. Med 2023, 4, 855–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, L.O. An Overview of Nonclinical and Clinical Liver Toxicity Associated With AAV Gene Therapy. Toxicol Pathol 2023, 51, 400–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D. Lethal Immunotoxicity in High-Dose Systemic AAV Therapy. Molecular Therapy 2023, 31, 3123–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A. Rationale and Strategies for the Development of Safe and Effective Optimized AAV Vectors for Human Gene Therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; He, T.; Chai, Z.; Samulski, R.J.; Li, C. Blood-Brain Barrier Shuttle Peptides Enhance AAV Transduction in the Brain after Systemic Administration. Biomaterials 2018, 176, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer, T.C.; Hoffman, B.A.; Chen, W.; Shah, I.; Ren, X.-Q.; Knox, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Khalid, H.; et al. Highly Conserved Brain Vascular Receptor ALPL Mediates Transport of Engineered AAV Vectors across the Blood-Brain Barrier. Molecular Therapy 2025, 33, 3902–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shay, T.F.; Sullivan, E.E.; Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Ravindra Kumar, S.; Goertsen, D.; Brown, D.; Crosby, A.; Vielmetter, J.; Borsos, M.; et al. Primate-Conserved Carbonic Anhydrase IV and Murine-Restricted LY6C1 Enable Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing by Engineered Viral Vectors. Sci Adv 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Chen, A.T.; Chan, K.Y.; Sorensen, H.; Barry, A.J.; Azari, B.; Zheng, Q.; Beddow, T.; Zhao, B.; Tobey, I.G.; et al. Targeting AAV Vectors to the Central Nervous System by Engineering Capsid–Receptor Interactions That Enable Crossing of the Blood–Brain Barrier. PLoS Biol 2023, 21, e3002112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wan, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Variants of the Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 9 with Enhanced Penetration of the Blood–Brain Barrier in Rodents and Primates. Nat Biomed Eng 2022, 6, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váňová, J.; Hejtmánková, A.; Kalbáčová, M.H.; Španielová, H. The Utilization of Cell-Penetrating Peptides in the Intracellular Delivery of Viral Nanoparticles. Materials 2019, 12, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, R.C.; Kemker, I.; Krutzke, L.; Allmendinger, E.; Mandell, D.J.; Sewald, N.; Kochanek, S.; Müller, K.M. EGFR-Binding Peptides: From Computational Design towards Tumor-Targeting of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsids. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Váňová, J.; Hejtmánková, A.; Žáčková Suchanová, J.; Sauerová, P.; Forstová, J.; Hubálek Kalbáčová, M.; Španielová, H. Influence of Cell-Penetrating Peptides on the Activity and Stability of Virus-Based Nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 2020, 576, 119008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moço, P.D.; Dash, S.; Kamen, A.A. Enhancement of Adeno-associated Virus Serotype 6 Transduction into T Cells with Cell-penetrating Peptides. J Gene Med 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrato, C.P.; Langel, Ü. An Update on Cell-Penetrating Peptides with Intracellular Organelle Targeting. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2022, 19, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestin, M.; Dowaidar, M.; Langel, Ü. Uptake Mechanism of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. In; 2017; pp. 255–264.

- Okafor, M.; Schmitt, D.; Ory, S.; Gasman, S.; Hureau, C.; Faller, P.; Vitale, N. The Different Cellular Entry Routes for Drug Delivery Using Cell Penetrating Peptides. Biol Cell 2025, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Robbins, P. Cell-Type Specific Penetrating Peptides: Therapeutic Promises and Challenges. Molecules 2015, 20, 13055–13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowaidar, M. Uptake Pathways of Cell-Penetrating Peptides in the Context of Drug Delivery, Gene Therapy, and Vaccine Development. Cell Signal 2024, 117, 111116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.E.; Zahid, M. Cell Penetrating Peptides, Novel Vectors for Gene Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Vargas, L.M.; Prada-Gracia, D. Exploring the Chemical Features and Biomedical Relevance of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 26, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleal, K.; He, L.; D. Watson, P.; T. Jones, A. Endocytosis, Intracellular Traffic and Fate of Cell Penetrating Peptide Based Conjugates and Nanoparticles. Curr Pharm Des 2013, 19, 2878–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, R.M.; Mellman, I.S.; Muller, W.A.; Cohn, Z.A. Endocytosis and the Recycling of Plasma Membrane. J Cell Biol 1983, 96, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Futaki, S.; Nakase, I. Cell-Surface Interactions on Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides Allow for Multiplex Modes of Internalization. Acc Chem Res 2017, 50, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorén, P.E.G.; Persson, D.; Esbjörner, E.K.; Goksör, M.; Lincoln, P.; Nordén, B. Membrane Binding and Translocation of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 3471–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, G.E.; Asokan, A. Cellular Transduction Mechanisms of Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors. Curr Opin Virol 2016, 21, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, Q.; Qin, Y.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Gou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. An Adeno-Associated Virus Variant Enabling Efficient Ocular-Directed Gene Delivery across Species. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietersz, K.L.; Du Plessis, F.; Pouw, S.M.; Liefhebber, J.M.; van Deventer, S.J.; Martens, G.J.M.; Konstantinova, P.S.; Blits, B. PhP.B Enhanced Adeno-Associated Virus Mediated-Expression Following Systemic Delivery or Direct Brain Administration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, K.; Sugano, E.; Murakami, F.; Yamashita, T.; Ozaki, T.; Tomita, H. Improved Transduction Efficiencies of Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors by Synthetic Cell-Permeable Peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 478, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanamadala, Y.; Roy, R.; Williams, A.A.; Uppu, N.; Kim, A.Y.; DeCoster, M.A.; Kim, P.; Murray, T.A. Intranasal Delivery of Cell-Penetrating Therapeutic Peptide Enhances Brain Delivery, Reduces Inflammation, and Improves Neurologic Function in Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Österlund, N.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Gräslund, A. Cell-Penetrating Peptides with Unexpected Anti-Amyloid Properties. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yokota, T.; Gama, V.; Yoshida, T.; Gomez, J.A.; Ishikawa, K.; Sasaguri, H.; Cohen, H.Y.; Sinclair, D.A.; Mizusawa, H.; et al. Bax-Inhibiting Peptide Protects Cells from Polyglutamine Toxicity Caused by Ku70 Acetylation. Cell Death Differ 2007, 14, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Letai, A.; Sarosiek, K. Regulation of Apoptosis in Health and Disease: The Balancing Act of BCL-2 Family Proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, S.; Xu, Q.; Velours, J.; Reed, J.C. The Mitochondrial F0F1-ATPase Proton Pump Is Required for Function of the Proapoptotic Protein Bax in Yeast and Mammalian Cells. Mol Cell 1998, 1, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.A.; Jackson, S.P. A Means to a DNA End: The Many Roles of Ku. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004, 5, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, V.; Gomez, J.A.; Mayo, L.D.; Jackson, M.W.; Danielpour, D.; Song, K.; Haas, A.L.; Laughlin, M.J.; Matsuyama, S. Hdm2 Is a Ubiquitin Ligase of Ku70-Akt Promotes Cell Survival by Inhibiting Hdm2-Dependent Ku70 Destabilization. Cell Death Differ 2009, 16, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.Y.; Lavu, S.; Bitterman, K.J.; Hekking, B.; Imahiyerobo, T.A.; Miller, C.; Frye, R.; Ploegh, H.; Kessler, B.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Acetylation of the C Terminus of Ku70 by CBP and PCAF Controls Bax-Mediated Apoptosis. Mol Cell 2004, 13, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, R.; Gama, V.; Fagan, B.M.; Bower, J.J.; Swahari, V.; Pevny, L.H.; Deshmukh, M. Human Embryonic Stem Cells Have Constitutively Active Bax at the Golgi and Are Primed to Undergo Rapid Apoptosis. Mol Cell 2012, 46, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, V.; Xue, Z.; Gama, V.; Matsuyama, S.; Sadofsky, M.J. Ku70 Is Stabilized by Increased Cellular SUMO. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 366, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gama, V.; Yoshida, T.; Gomez, J.A.; Basile, D.P.; Mayo, L.D.; Haas, A.L.; Matsuyama, S. Involvement of the Ubiquitin Pathway in Decreasing Ku70 Levels in Response to Drug-Induced Apoptosis. Exp Cell Res 2006, 312, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, S.; Palmer, J.; Bates, A.; Poventud-Fuentes, I.; Wong, K.; Ngo, J.; Matsuyama, M. Bax-Induced Apoptosis Shortens the Life Span of DNA Repair Defect Ku70-Knockout Mice by Inducing Emphysema. Exp Biol Med 2016, 241, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.; Matsuyama, M.; Kim, C.; Poventud-Fuentes, I.; Bates, A.; Siedlak, S.L.; Lee, H.; Doughman, Y.Q.; Watanabe, M.; Liner, A.; et al. Bax Deficiency Extends the Survival of Ku70 Knockout Mice That Develop Lung and Heart Diseases. Cell Death Dis 2015, 6, e1706–e1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-McKean, J.J.; Matsuyama, M.; Guo, C.W.; Ni, L.; Sassouni, B.; Kurup, S.; Nickells, R.; Matsuyama, S. Cytoprotective Small Compound M109S Attenuated Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration Induced by Optic Nerve Crush in Mice. Cells 2024, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-H.; Cui, M.; Liu, H.; Guo, P.; McGowan, J.; Cheng, S.-Y.; Gessler, D.J.; Xie, J.; Punzo, C.; Tai, P.W.L.; et al. Cell-Penetrating Peptide-Grafted AAV2 Capsids for Improved Retinal Delivery via Intravitreal Injection. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2025, 33, 101426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; WuWong, D.J.; Wong, S.; Matsuyama, M.; Matsuyama, S. Pharmacological Inhibition of Bax-Induced Cell Death: Bax-Inhibiting Peptides and Small Compounds Inhibiting Bax. Exp Biol Med 2019, 244, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandgren, S.; Cheng, F.; Belting, M. Nuclear Targeting of Macromolecular Polyanions by an HIV-Tat Derived Peptide. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 38877–38883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joliot, A.; Prochiantz, A. Transduction Peptides: From Technology to Physiology. Nat Cell Biol 2004, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, P. Membrane Internalization Mechanisms and Design Strategies of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, M.; Davis, P. Mechanism of Uptake of C105Y, a Novel Cell-Penetrating Peptide. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, I.P.; Michalakis, S.; Wilhelm, B.; Reichel, F.F.; Ochakovski, G.A.; Zrenner, E.; Ueffing, M.; Biel, M.; Wissinger, B.; Bartz-Schmidt, K.U.; et al. Superior Retinal Gene Transfer and Biodistribution Profile of Subretinal Versus Intravitreal Delivery of AAV8 in Nonhuman Primates. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2017, 58, 5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Madigan, V.; Pu, S.; Fan, X.; Pu, J.; Bei, F. Cross-Species Tropism of AAV.CPP.16 in the Respiratory Tract and Its Gene Therapies against Pulmonary Fibrosis and Viral Infection. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6, 102144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ma, L.; Chai, P.; Shi, H.; Yao, Y.; Ge, S.; Jia, R.; Wen, X.; et al. A Penetrable AAV2 Capsid Variant for Efficient Intravitreal Gene Delivery to the Retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2025, 66, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.J.; Seveau, S.; Veiga, E.; Matsuyama, S.; Cossart, P. Ku70, a Component of DNA-Dependent Protein Kinase, Is a Mammalian Receptor for Rickettsia Conorii. Cell 2005, 123, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Su, Q.; Yip, M.; McGowan, J.; Punzo, C.; Gao, G.; Tai, P.W.L. The AAV2.7m8 Capsid Packages a Higher Degree of Heterogeneous Vector Genomes than AAV2. Gene Ther 2024, 31, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.D.; Flynn, N.H. Cell-Penetrating Peptides Transport Therapeutics into Cells. Pharmacol Ther 2015, 154, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolhassani, A.; Jafarzade, B.S.; Mardani, G. In Vitro and in Vivo Delivery of Therapeutic Proteins Using Cell Penetrating Peptides. Peptides (N.Y.) 2017, 87, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hołubowicz, R.; Du, S.W.; Felgner, J.; Smidak, R.; Choi, E.H.; Palczewska, G.; Menezes, C.R.; Dong, Z.; Gao, F.; Medani, O.; et al. Safer and Efficient Base Editing and Prime Editing via Ribonucleoproteins Delivered through Optimized Lipid-Nanoparticle Formulations. Nat Biomed Eng 2024, 9, 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Sun, Z.; Zou, Z.; Wang, M.; Li, Q.; Hu, X.; Li, N. Cell-Penetrating Peptide-Driven Cre Recombination in Porcine Primary Cells and Generation of Marker-Free Pigs. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0190690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, R.; Ning, J.; Bao, X.; Yan, Z.; Chen, H.; Ding, L.; Shu, C. Conjugation of Sulpiride with a Cell Penetrating Peptide to Augment the Antidepressant Efficacy and Reduce Serum Prolactin Levels. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 174, 116610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, M.; Santhoshkumar, P.; Sharma, K.K. Cell-Penetrating Chaperone Peptide Prevents Protein Aggregation and Protects against Cell Apoptosis. Adv Biosyst 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, J.; Guo, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, K.; Chai, Z.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, L.; et al. A Pentapeptide Enabled AL3810 Liposome-Based Glioma-Targeted Therapy with Immune Opsonic Effect Attenuated. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkadwala, S.; Dos Santos Rodrigues, B.; Sun, C.; Singh, J. Biodistribution of TAT or QLPVM Coupled to Receptor Targeted Liposomes for Delivery of Anticancer Therapeutics to Brain in Vitro and in Vivo. Nanomedicine 2020, 23, 102112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raguram, A.; Banskota, S.; Liu, D.R. Therapeutic in Vivo Delivery of Gene Editing Agents. Cell 2022, 185, 2806–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingozzi, F.; Anguela, X.M.; Pavani, G.; Chen, Y.; Davidson, R.J.; Hui, D.J.; Yazicioglu, M.; Elkouby, L.; Hinderer, C.J.; Faella, A.; et al. Overcoming Preexisting Humoral Immunity to AAV Using Capsid Decoys. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmowski-Wolfe, A.; Stingl, K.; Habibi, I.; Schorderet, D.; Tran, H. Novel PDE6B Mutation Presenting with Retinitis Pigmentosa – A Case Series of Three Patients. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2019, 236, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assaf, B.T. Systemic Toxicity of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Therapy Vectors. Toxicol Pathol 2024, 52, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforet, G.A. Thrombotic Microangiopathy Associated with Systemic Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Transfer: Review of Reported Cases. Hum Gene Ther 2025, 36, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sequence | Origin and background history |

|---|---|

| VPMLK | Bax binding domain of human, monkey and dog Ku70 |

| VPTLK | Bax binding domain of mouse Ku70 |

| VPALR | Putative Bax binding domain of rat Ku70 |

| VSALK | Putative Bax binding domain of chicken Ku70 |

| PMLKE | Bax binding domain of human, monkey and dog Ku70 |

| VPALK | Putative Bax binding domain of Ccattle and African clawed frog Ku70 |

| VSLKK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| VSGKK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| KLPVM | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| IPMIK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| KLGVM | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| KLPVT | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| VPMIK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| IPALK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| IPMLK | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| VPTLQ | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| QLPVM | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| ELPVM | Artificially designed CPP5 |

| VPTLE | Artificially designed CPP5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).