1. Introduction

In Mexico and internationally, several historical milestones have shaped the development of social security systems, health care delivery, and the training of human resources in public health. The consolidation of social security as a contributory right and the recognition of health as a social good contributed to a broader conception of health as a collective responsibility and a state obligation [

1]. These foundations supported the consolidation of national health systems and framed public health as an interdisciplinary field with both scientific and social dimensions.

Parallel developments in the Americas played a decisive role in structuring public health education. The establishment of early public health institutions and schools during the twentieth century marked the institutionalization of public health training in the region, laying the groundwork for professional education models integrating biomedical sciences, population health, and social medicine [

2].

Subsequently, the Essential Functions of Public Health were articulated and later updated within the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals, emphasizing equity, access, efficiency, and universal coverage [

3]. This framework reinforced the central role of workforce training in achieving population health goals. Influential milestones in health professions education, including the Flexner Report and subsequent educational reforms in Latin America, contributed to modern understandings of the health–disease process, social determinants of health, and community-oriented care models [

4,

5].

In this context, higher education institutions have been encouraged to innovate pedagogical approaches and align curricula with societal needs and workforce demands [

6]. Educational theory and faculty development frameworks emphasize scientific rigor, contextual relevance, and social accountability as core components of professional training [

7].

Training in human resources for health may be classified as formal or non-formal. Formal education is delivered by higher education institutions that confer academic degrees and professional credentials, whereas non-formal training occurs in institutional or community settings without formal accreditation [

8]. In low- and middle-income countries, geographic and socioeconomic constraints limit access to traditional in-person education, fostering the expansion of online, hybrid, and self-directed learning modalities supported by information and communication technologies [

9,

10,

11].

At the global level, professional associations and international organizations have defined core competencies for public health professionals, including data analysis, policy development, program planning and evaluation, communication, leadership, teamwork, and systems thinking [

3]. However, in Latin America, the absence of a unified framework for competency certification has resulted in heterogeneous training standards and professional recognition across countries [

2].

In Mexico, postgraduate education evaluation and accreditation are institutionalized through the National Postgraduate System, implemented by the former National Council for Science and Technology and currently overseen by the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation [

12,

13]. This system certifies academic quality and social relevance and provides enrolled students with benefits such as scholarships and health insurance, functioning as a key mechanism for quality assurance and equity in advanced education.

Given ongoing epidemiological transitions and health system challenges, systematic characterization of public health education is essential. Although regional analyses have been published previously, updated and comprehensive evidence for Mexico remains limited [

14]. Examining current academic offerings, institutional characteristics, geographic distribution, delivery modalities, and accreditation status provides critical input for educational planning and for strengthening the public health workforce in alignment with national priorities and the Sustainable Development Goals [

3,

15].

2. Materials and Methods

A systematic review of educational offerings was conducted using the official websites of public and private higher education institutions in Mexico that provide academic programs in public health and related disciplines. The review included bachelor’s degrees, specializations, master’s degrees, and PhD programs, both professional and research-oriented, that were active between March and November 2024. Programs designed for health professionals were eligible regardless of delivery modality, including fully in-person, semi–in-person, fully online, or hybrid formats.

Full-time programs were defined as those with a structured curriculum delivered at designated educational facilities with dedicated teaching and administrative infrastructure, requiring regular in-person attendance and adherence to a fixed schedule. Part-time programs were defined as those maintaining a formal curriculum but offering greater flexibility in time and physical presence, without requiring continuous on-site attendance.

Searches were conducted in Spanish using the Google® search engine. The following keywords were applied individually and in combination: public health, preventive medicine, quality of care, social medicine, health promotion, community health, health services administration, hospital administration, health institution administration, and service management. To be included, academic programs were required to be directly linked to the official website of the corresponding institution. In the case of private institutions, programs were additionally required to report possession of an Official Study Validity Registry granted by the Ministry of Public Education. Two programs were excluded because, although information about them was publicly available, it was not hosted on the institution’s official website.

The variables extracted for analysis included the name of the higher education institution, state of the Mexican Republic, academic level, program title, modality of delivery (school-based, defined as in-person attendance five days per week; semi–school-based, defined as in-person attendance on selected days; or online, defined as no required in-person attendance), institutional sector (public or private), inclusion in the National Postgraduate System, program duration in months, and geographic region.

Regional classification followed the framework of the National Survey of Financial Inclusion of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, which groups Mexican states into six geographic regions based on socioeconomic and financial indicators [

16]: Northwest (Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Durango, Sinaloa, Sonora); Northeast (Coahuila, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas); West and Bajío (Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, Querétaro, Zacatecas, Colima); Mexico City; South Central and East (State of Mexico, Hidalgo, Morelos, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Veracruz); and South (Campeche, Chiapas, Guerrero, Quintana Roo, Tabasco, Yucatán, Oaxaca).

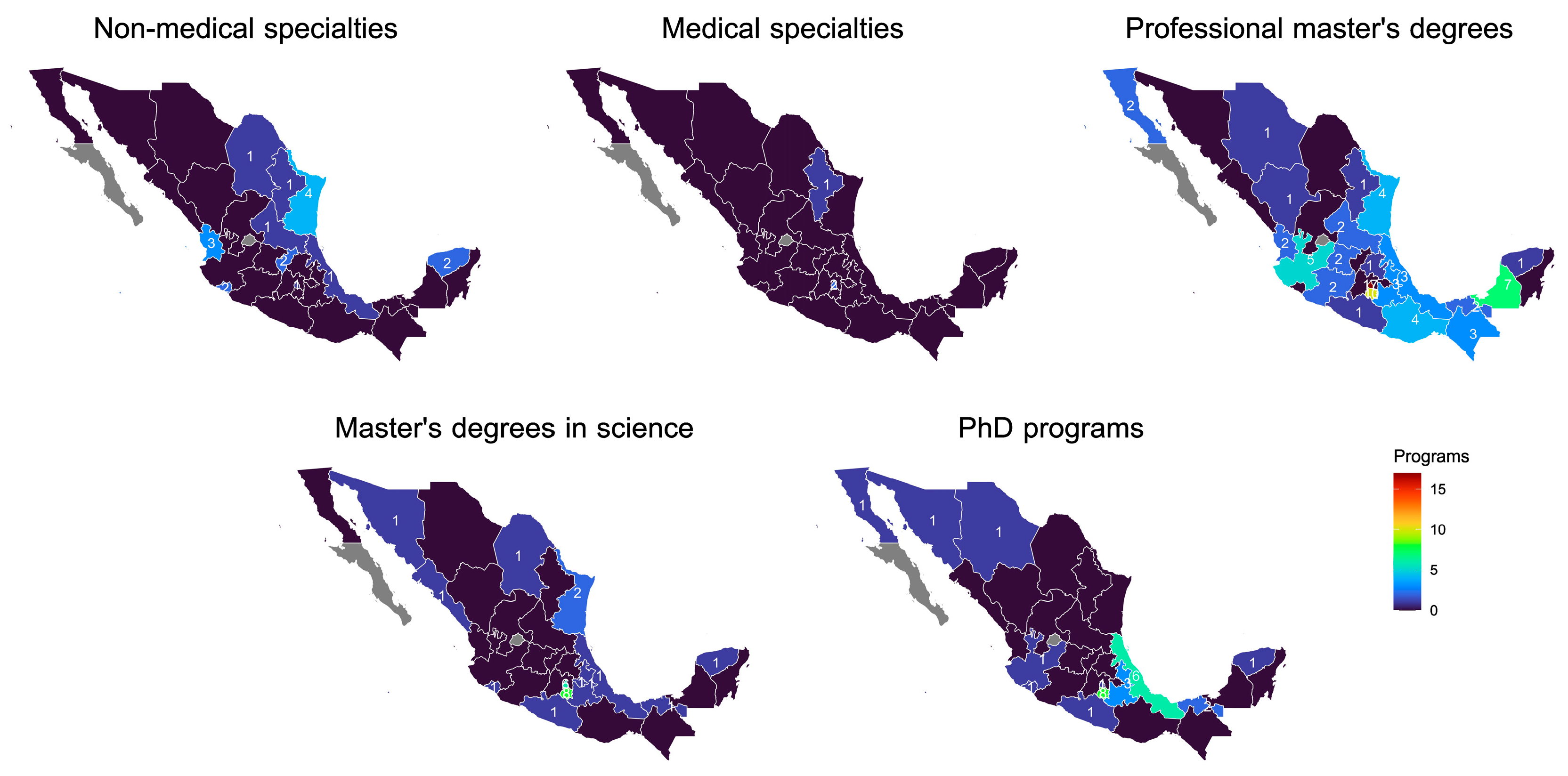

All records were compiled and systematized in Microsoft Excel®. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® version 25. A logistic regression model was constructed to identify factors associated with inclusion in the National Postgraduate System, adjusting for geographic region, academic level, institutional sector, and program duration in months. In addition, a geospatial analysis was conducted using official digital cartographic resources provided by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography [

17]. Thematic maps were generated to identify inequalities in the national distribution of academic programs. Digital mapping was performed using Mapa Digital for desktop version 6.3.018, and map visualization and image editing were completed using QGIS version 3.14.16 Pi.

Because all data were obtained from publicly accessible institutional websites and did not involve human participants or personal data, this study was classified as minimal risk and did not require ethical approval, in accordance with national regulations [

18].

3. Results

A total of 175 academic programs in public health and related disciplines were identified across 30 of the 32 states of the Mexican Republic (

Table 1). No eligible programs were found in Aguascalientes or Baja California Sur. Of the programs identified, 27 (15.4%) were bachelor’s degrees, 18 (10.3%) non-medical specializations, three (1.7%) medical specializations, 26 (14.9%) master’s degrees in science, 74 (42.3%) professional master’s degrees, and 27 (15.4%) PhD programs. In total, these programs were offered by 57 higher education institutions, of which 39 (64.7%) were public and 18 (35.3%) were private.

3.1. Institutional Sector and Accreditation Status

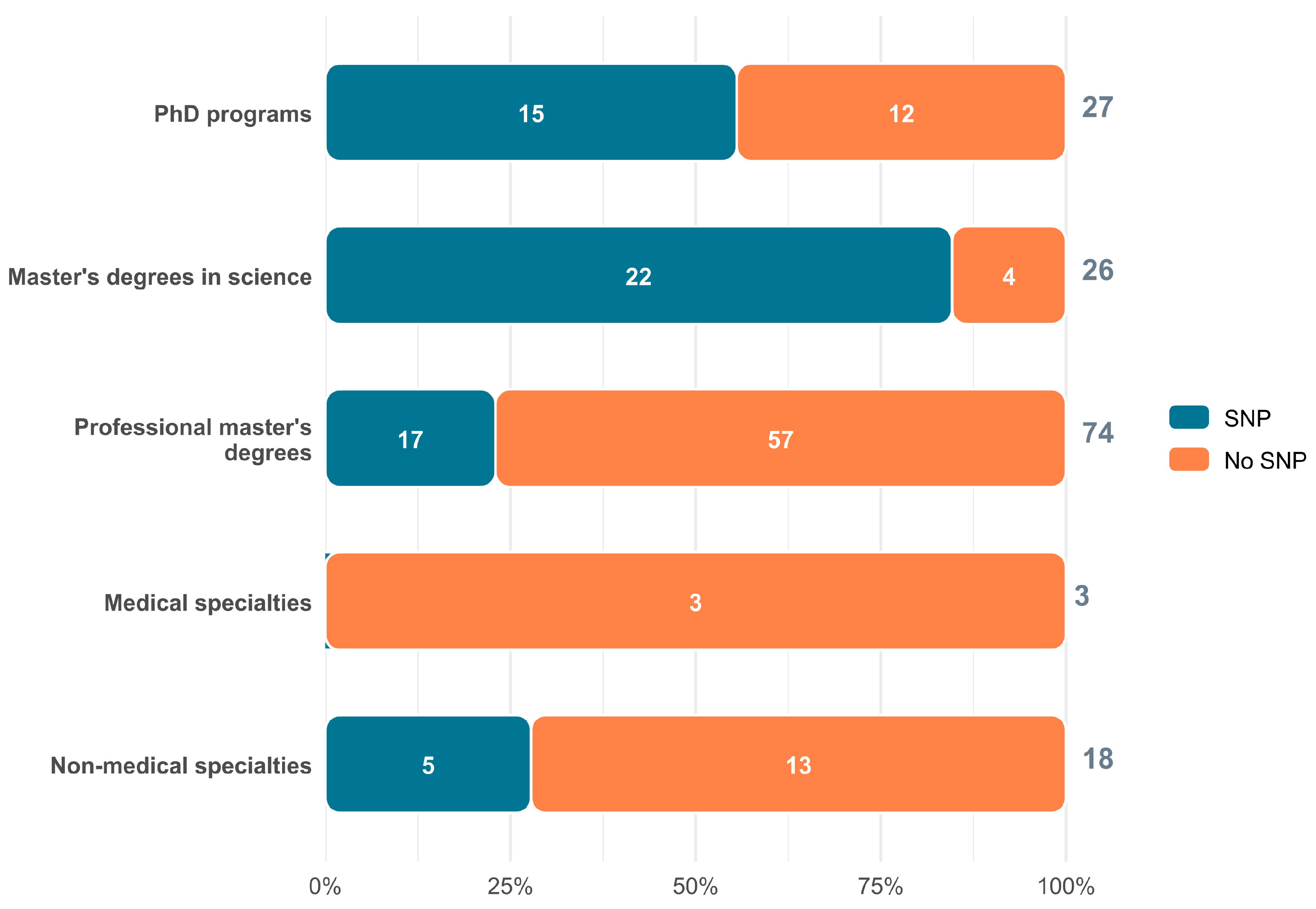

Overall, 113 programs (64.6%) were delivered by public institutions (

Table 1). Among the 148 postgraduate programs, only 59 (39.9%) were included in the National Postgraduate System (NPS). Accreditation varied markedly by academic level and program orientation. Within public institutions, two of three medical specializations (66.7%) were integrated into the national residency system, 25 of 26 master’s degrees in science (96.2%) were accredited, and 22 of 27 PhD programs (81.5%) were included in the NPS. In contrast, professional master’s degrees—despite constituting the largest share of postgraduate offerings—showed minimal integration into the accreditation framework (

Figure 1).

Among accredited postgraduate programs, 17 were classified within the field of science, three within public health, one within quality management, and one within senior management. Taken together, these findings demonstrate a strong alignment between accreditation and research-oriented training pathways, with comparatively limited coverage of professionally oriented programs.

3.2. Delivery Modality and Institutional Sector

The distribution of programs by delivery modality and institutional sector is presented in

Table 2. Within public institutions, 78 programs (69.0%) were fully school-based and 12 (10.6%) were offered exclusively online. In contrast, private institutions showed greater diversification in delivery formats, with 24 programs (38.7%) delivered in person and 20 (32.3%) delivered online. Overall, public institutions accounted for nearly two-thirds of the national academic offering.

Information on delivery modality was unavailable for 11.5% of public and 14.5% of private institutions, reflecting persistent limitations in the transparency and standardization of publicly available educational information.

3.3. Geographic Distribution of Programs

Figure 2 depicts the geospatial distribution of public health–related academic programs by state and academic level. Research-oriented programs, particularly master’s degrees in science and PhD programs, were concentrated in a limited number of states, notably in the northwestern region and in states along the Gulf of Mexico. In contrast, professional master’s programs and bachelor’s degrees showed broader geographic dispersion, although with substantial inter-state variability. Only seven states offered online programs in public health or related disciplines, underscoring the limited penetration of flexible delivery modalities nationwide.

3.4. Factors Associated with Accreditation

Factors associated with inclusion in the National Postgraduate System were examined among non-medical specializations, master’s degrees, and PhD programs using a multivariable logistic regression model (

Table 3). Programs located in the South Central and East region exhibited higher adjusted odds of accreditation compared with those in the South, although this association did not reach statistical significance (OR = 2.42; 95% CI 0.78–7.48; p = 0.123).

By academic level, master’s degrees in science demonstrated significantly higher odds of accreditation compared with PhD programs (OR = 7.34; 95% CI 1.72–31.34; p = 0.007). In contrast, professional master’s degrees showed consistently lower odds of inclusion in the NPS (OR = 0.36; 95% CI 0.13–1.01; p = 0.051), reinforcing the structural disconnect between the dominant training modality and national quality assurance mechanisms.

4. Discussion

The present study provides an updated national overview of public health and related academic programs in Mexico in 2024, revealing structural changes in scale, orientation, accreditation, and delivery modalities when compared with earlier regional assessments. Previous analyses of public health education in Latin America identified Mexico as one of the countries with the largest postgraduate offerings, second only to Brazil during the 2021–2022 period [

2]. In contrast, the identification of 175 active programs in 2024 suggests a net reduction in program volume. This decline may reflect the closure or restructuring of programs, fragmentation of curricular offerings, or persistent limitations in the availability and updating of institutional information on official websites. These findings highlight the need for standardized, interoperable information systems capable of capturing both historical and real-time data on educational offerings, an issue previously emphasized in regional mapping studies [

2].

Beyond changes in volume, the composition of academic offerings reveals a clear predominance of professionally oriented master’s degrees over research-focused training. This pattern aligns with broader regional trends in which countries such as Mexico and Peru emphasize applied postgraduate education, in contrast to Brazil and Cuba, where specialization and continuing education pathways have historically been prioritized [

2]. While professional master’s programs may respond more directly to immediate workforce demands, their limited integration into national accreditation mechanisms raises concerns regarding educational quality, equity, and long-term workforce development.

Accreditation through the National Postgraduate System remains uneven and strongly associated with academic orientation rather than geographic location. Research-oriented master’s degrees and PhD programs demonstrate substantially higher inclusion rates than professional master’s degrees, despite the latter representing the largest share of postgraduate offerings. This imbalance suggests that current accreditation frameworks may be better aligned with traditional academic and research models than with professionally oriented training. Given that accreditation is linked to student benefits and institutional recognition, this misalignment risks reinforcing inequities among postgraduate students and limiting incentives for professional programs to engage in quality assurance processes [

12,

13]. Similar concerns regarding the reach and effectiveness of accreditation mechanisms have been raised in broader discussions of educational governance and quality assurance in higher education [

6,

7].

The geographic distribution of programs further underscores structural inequities. Research-oriented programs are concentrated in a limited number of states, whereas professional programs show a broader but uneven territorial spread. Such spatial concentration mirrors longstanding regional disparities in educational infrastructure and research capacity, which have implications for equitable access to advanced public health training and for the development of locally responsive health systems. These findings reinforce calls for coordinated national planning that aligns educational capacity with population needs and regional health system priorities [

3,

15].

Delivery modality represents another critical dimension of equity and accessibility. Although fully in-person education remains dominant, particularly in public institutions and research-oriented programs, online and hybrid modalities have expanded modestly since previous assessments. This expansion reflects global trends in digital learning and adult education, supported by advances in information and communication technologies [

9,

10,

11]. However, the disproportionate concentration of online offerings within private institutions raises concerns regarding financial accessibility and the potential reinforcement of social inequalities. While digital education has been promoted as a mechanism to reduce geographic and socioeconomic barriers, its benefits may remain unevenly distributed without complementary public investment and policy support [

8,

9,

10,

11].

The reliance of this study on publicly available institutional information introduces several limitations. Variability in reporting standards, incomplete descriptions of program characteristics, and inconsistent updating practices constrained comparability across institutions and over time. Nevertheless, this perspective is itself informative, as transparency and accessibility of educational information are essential components of educational equity, informed decision-making, and accountability in higher education systems [

20,

21]. From the standpoint of prospective students, policymakers, and workforce planners, incomplete or fragmented information represents a structural barrier to effective planning and participation.

Taken together, these findings suggest that public health education in Mexico is undergoing a process of reconfiguration characterized by expansion of professionally oriented training, persistent gaps in accreditation, limited diversification of delivery modalities, and marked geographic inequalities. Addressing these challenges will require integrated policy approaches that strengthen accreditation incentives for professional programs, expand equitable access to flexible learning modalities, and develop national and regional information systems linking education, health, and labor sectors. Such efforts are essential to ensure that public health training contributes effectively to workforce readiness, health system resilience, and progress toward universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals [

3,

15].

5. Conclusions

Public health and related academic programs in Mexico are distributed across most of the national territory; however, accreditation through the National Postgraduate System remains concentrated in public institutions, potentially disadvantaging students enrolled in private programs. Across Latin America, and particularly in Mexico, public health training increasingly emphasizes professional master’s degrees over research-oriented programs, while opportunities to expand flexible delivery modalities, including online education, remain underdeveloped.

Systematic analysis of national academic offerings is constrained by the absence of integrated, inter-institutional information systems capable of supporting strategic planning for health workforce development. Such systems are essential for aligning educational capacity with population growth and health system needs, and for ensuring the availability of adequate infrastructure, including scholarships, qualified faculty, digital connectivity, training sites, and institutional partnerships. Moreover, these systems should incorporate indicators of labor market absorption and assess the alignment between acquired competencies and workforce expectations, both under routine conditions and during public health emergencies.

The development of regional information systems on human resource training that integrate the health, education, and labor sectors, and that are aligned with national policy priorities, would support the design of more comprehensive, preventive, and proactive health care models. Only through such coordinated approaches will it be possible to rigorously assess the contribution of education to public health outcomes and to its broader role in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-R.; methodology, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; software, J.R.-R.; validation, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; formal analysis, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; investigation, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; resources, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; data curation, J.R.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; visualization, J.R.-R.; supervision, J.R.-R. and O.A.-C.; project administration, J.R.-R.; funding acquisition, O.A.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study was based exclusively on publicly available information from institutional websites and did not involve human participants, animals, or the use of identifiable personal data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article. All data were obtained from publicly accessible official websites of higher education institutions and regulatory bodies. No new datasets were generated.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the higher education institutions whose publicly available information made this analysis possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CONACYT |

National Council for Science and Technology |

| ENIF |

National Survey on Financial Inclusion |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technologies |

| INEGI |

National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NPS |

National Postgraduate System |

| PAHO |

Pan American Health Organization |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Arrieta, A. Health insurance and the contributory principle of social security in the United States of America. Lat. Am. J. Soc. Law 2016, 23, 3–30. [CrossRef]

- Peres, F.; Blanco Centurión, M.P.; Monteiro Bastos da Silva, J.; Brandão, A.L. Mapping public health education in Latin America: Perspectives for training institutions. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2023, 47, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Essential Public Health Functions; PAHO/WHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Narro-Robles, J. Flexner’s legacy: Basic sciences, the hospital, the laboratory, the community. Gac. Med. Mex. 2004, 140, 52–55.

- Pinzón, C. The major paradigms of medical education in Latin American countries. Acta Med. Colomb. 2008, 33, 33–41.

- Delors, J. The four pillars of education. In Education: The Treasure Within; UNESCO: Mexico City, Mexico, 1994; pp. 91–103.

- Galbusera Testa, C.I. The Evolution of Teaching–Learning Model Design in the New Generational Scenario; 2020; pp. 103–114.

- Sandmann, L.R. Adult learning: A key for the 21st century. Adult Learn. 1998, 10, 2–3. [CrossRef]

- Redecker, C.; Ala-Mutka, K.; Bacigalupo, M.; Ferrari, A.; Punie, Y. Learning 2.0: The Impact of Web 2.0 Innovations on Education and Training in Europe; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2009. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. ICT Competency Standards for Teachers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008.

- UNESCO. ICT Competency Framework for Teachers; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019.

- National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT). National Program for Quality Postgraduate Studies. Available online: https://conacyt.mx/becas_posgrados/programa-nacional-de-posgrados-de-calidad/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Government of Mexico. Decree reforming, adding, and repealing various provisions of the Science and Technology Law. Off. Gaz. Fed. 2024.

- Peres, F.; Blanco Centurión, M.P.; Monteiro Bastos da Silva, J.; Brandão, A.L. Mapping public health education in Latin America: Perspectives for training institutions. Pan Am. J. Public Health 2023, 47, 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Digital Implementation Investment Guide (DIIG); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). National Survey on Financial Inclusion (ENIF): Conceptual Document; INEGI: Mexico City, Mexico.

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Digital Map. Available online: https://inegi.org.mx/temas/mapadigital/#Descargas (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Kondo, T.; Nishigori, H.; van der Vleuten, C. Locally adapting generic rubrics for the implementation of outcome-based medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 1–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, F.; Froufe, M. Psychology of Learning: Principles and Behavioral Applications; Ediciones Paraninfo: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- Municio, J.I.P. Cognitive Theories of Learning; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2009.

- Espejo, R.; José, L.; González-Suárez, M. Transformative learning and research programs in university teacher development. REDU J. Univ. Teach. 2015, 13, 309–330.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).