1. Introduction

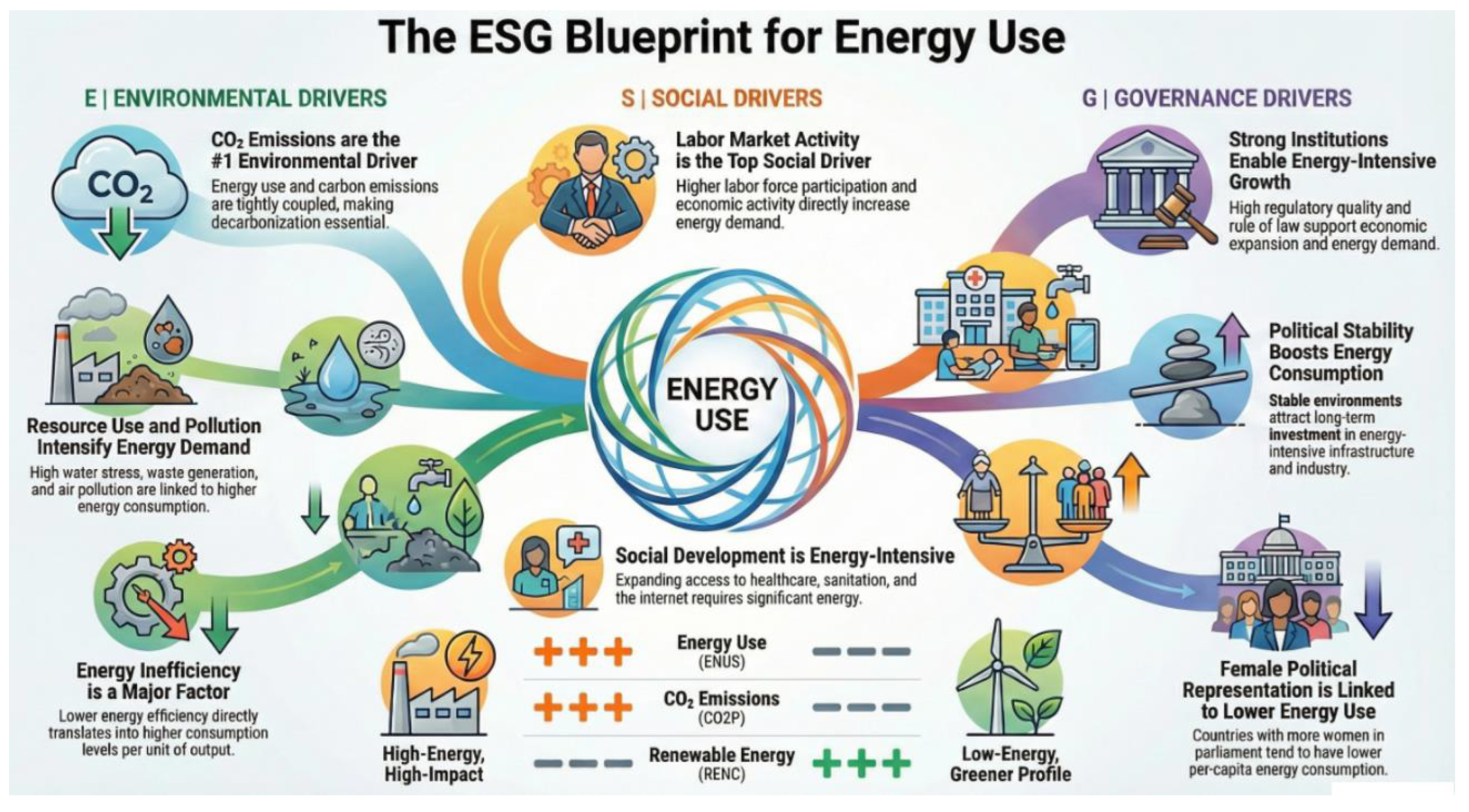

Energy use per capita (ENUS) is a key starting point for research into sustainable development, climate change, and economic transformation. In this respect, it captures both productive potential and technological change, as well as living standards and access to modern services, while also serving as a key mechanism through which human activity exerts pressure on the environment. Inasmuch as energy use drives greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, natural resource use, and climate change, ENUS is clearly at the fulcrum of the sustainability challenge. However, a lack of energy use is directly associated with poverty, limited access to health and education services, and missed economic opportunities. Recently, the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) paradigm has emerged as the most important metric for measuring sustainability performance across countries, companies, and financial instruments. ESG variables are extensively used now in policy formulation, risk assessment analyses, and in financial choices. It acts as a multivariable benchmark for measuring sustainable advancements (Drago et al., 2025; Saltık, 2024). However, presently, the empirical literature has yet to shed light on the proper positioning of the energy use per capita within the ESG system. Most empirical analyses to date view energy use through scattered observation points that predominantly focus either on the economic growth aspect of energy use or on the carbon-emission performance of energy use (Horbach, 2024; Şahin, 2025). There are other analyses that examine ESG variables as outcomes or predictors in financial or institutional settings, but do not explicitly incorporate energy use as the central variable affected by ESG processes (Tan et al., 2025). It has often resulted in energy use being predominantly the focus of observations, either in the context of the environment or as a control variable outside ESG regimes. It indicates a lack in the empirical literature. Firstly, very few studies exist on ENUS and ESG factors at a large scale (Afzal et al., 2025). Secondly, although environmental factors are considered in these studies, they apply linear econometric analysis (Davidescu et al., 2025) only when using large international datasets. However, it is important to analyze regions with diverse development paths, energy structures, environmental challenges, and so on, in the context of sustainable development. Furthermore, current research on energy, sustainability, and machine learning remains an independent process, focused on forecasting accuracy rather than interpretability and theoretical orientation (López-Flores et al., 2025; Xie et al., 2024). This paper fills this void in the literature by presenting an original and comprehensive empirical analysis of energy use per capita within the ESG framework, particularly the Environmental dimension. The originality of this study essentially resides in three main dimensions: the conceptual dimension, which presents an original interpretation of ENUS not only as a peripheral or technical indicator of ESG factors, but also as an essential outcome variable influenced by ESG environmental factors. The methodological dimension proposes an original approach that combines panel econometrics, clustering analysis, and machine learning methods within a comprehensive, unified framework. Conceptually speaking, the paper departs from the traditional divide between energy, on the one hand, as an driver for environmental degradation, and energy on the other, as an input into economic value added. Indeed, the paper considers the ENUS not merely as an intersection of energy and environmental degradation, but as part of the broader environmental system viewed through the lens of ESG factors. Thus, environmental management is conceptualized not only with regard to emissions but also through resource use, climate-related stresses, integrity of ecosystems, and energy system factors. Methodologically speaking, the article offers an integration of complementary methods that have been combined very rarely in the ESG and energy literature. First, panel data methods are used to establish structural connections between ENUS and environmental variables by exploiting cross-country differences and time-series variation (Davidescu et al., 2025). Fixed effects models, random effects models, and Weighted Least Squares methods are all applied to ensure robustness and to overcome typical heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation problems in cross-country panel analysis. Second, it presents an application of the clustering technique to identify underlying environmental regimes in which energy consumption is linked in its trajectory to various environmental variables: emissions, climate, resource depletion, and energy characteristics. This is an entirely novel approach because applying clustering analysis to ENUS issues has rarely been attempted in the ESG framework. Rather than imposing a single global relationship between environmental variables and energy consumption, the clustering analysis proposes several scenarios for different sustainability paths (Afzal et al., 2025). These CL’s point to the fact that different energy consumption patterns may be supported by very different patterns in environmental variables; that high or low values of ENUS have no meaning unless considered in the wider context of the environment. Third, it integrates analyses based on machine-learning algorithms to improve prediction accuracy by leveraging their stronger ability to handle complex relationships beyond the reach of standard econometric techniques. A set of algorithms is comparatively tested using an extensive set of normalized performance criteria, accounting for error measures and explanatory power. The outcome clearly shows that the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm distinguishes itself from others by its superior accuracy and robustness, as it better explains energy consumption by leveraging established environmental variables (Şahin, 2025; López-Flores et al., 2025). An important feature of this study is that it neither applies machine-learning algorithms in a “black box” way nor uses an uninterpretable explanatory variable set. The interpretation problem is overcome by applying dropout-based and additive-explanation techniques to estimate each individual variable’s contribution to energy consumption prediction. The empirical findings yield several new insights that directly address the gaps identified in the literature review. Firstly, panel regressions indicate that ENUS is significantly and deterministically driven by environmental pressure variables, emissions intensity, energy efficiency, and resource use variables, including carbon dioxide emissions, emissions of greenhouse gases above CO2, water withdrawals, waste production, and energy intensity (Davidescu et al., 2025). Not only do these results substantiate the fact that energy use incorporates deeply complex environmental dynamics and processes rather than operating strictly as a consequence of purely economic activities, but they spell out a clear message about the costs associated with the pursuit of environmentalism at the expense of energy progress for emerging nations which continue to dominate the world order at the dawn of the 21st century. Secondly, results based on clustering indicate a complex set of environmental regimes that fall into two broad categories – those that display high energy use associated with extreme environmental pressures and those that reflect high ENUS measures associated with comparatively moderate environmental pressures, reflecting their different sets of efficiencies and energy sources. On the other hand, low energy use regimes indicate countries with high natural capital or higher renewal rates, whereas others are associated with structural constraints and environmental pressures (Afzal et al., 2025; Horbach, 2024). Thirdly, results based on machine learning point out the primacy associated with non-linear local relationship dynamics that effectively determine ENUS measures. Not only do these results reinforce that energy use owes a great deal to similarities between countries' environmental variables and confirms the view of environmental scientists that countries continue along their specific environmental trajectories or routes rather than being forced into a globally convergent manner as argued among neoliberals and neoclassicals associated with globalization theory (Horbach, 2022; Iliško et al., 2020), but they indicate that emissions variables, overall environmental efficiencies and pollutions, as well as climate change variables owe a great deal compared to structural variables and land variables associated with their determinations as confirmed innovatively by interpretability analysis procedures and methods (Şahin, 2025; Xie et al., 2024). On the whole, this article is an original contribution inasmuch as it integrates ESG analysis, energy economics, and machine learning. This paper clearly illustrates that energy use per capita is far too complex to be addressed from either structural inference or regime detection alone. Rather, it is argued that knowledge about energy per capita is best acquired via an integrated approach that combines structural inference, regime detection, and predictive analysis. By locating countries’ ESG scores within ESG-defined multidimensional environmental regimes, it is easier to gain a sophisticated perspective on sustainability issues. Indeed, this paper’s analysis clearly indicates that energy and climate policies must be matched to differentiated regimes rather than treated in a generic way. Thus, this paper is an original contribution vis-à-vis both empirical and ESG-based analyses of sustainability challenges (Drago et al., 2025; Tan et al., 2025).

The article continues as follows: the second section reviews the literature on energy consumption and ESG, highlighting the main theoretical perspectives and empirical gaps. The third section presents the methodology, data, and theoretical framework, introducing the integrated use of panel data econometrics, machine learning regression, and clustering techniques. The fourth section analyzes the relationship between energy use per capita and the Environmental (E) pillar of ESG using multimethod empirical evidence. The fifth section examines the Social (S) determinants of energy consumption, focusing on social development, labor markets, and demographic dynamics. The sixth section investigates the role of Governance (G) indicators in shaping energy use through institutional quality and regulatory effectiveness. The seventh section interprets energy use per capita as a multidimensional ESG nexus by integrating results across all three pillars. The eighth section discusses policy implications within an integrated ESG framework. The final section concludes by summarizing the main findings and contributions of the study.

2. Literature Review

Recent research increasingly positions environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations as the guiding principle for understanding the transformation of modern energy systems. As a guiding principle, energy efficiency and transformation are perceived not only from a technological perspective but also through the lens of a complex process, whose contours are shaped by the quality of governance, financial structures, technological change, and human capital. Research on the subject is increasing, exploring how the integration of ESG considerations affects energy efficiency at the corporate, sector, and macroeconomic levels, while acknowledging the value-creating potential of a cohesive ESG approach, alongside the risks posed by poor governance and greenwashing. Recent research also highlights the growing integration of ESG considerations into the global energy sector and views ESG factors as a strategic means to improve energy sustainability and competitiveness. Adedokun (2026) highlights the legal and institutional integration of ESG factors for Nigeria's energy transition in its oil and gas industry and asserts that sound ESG governance structures can expedite the transition to energy sustainability. Nor et al. (2026) demonstrate the beneficial impact of digital advancements and smart technologies on the ESG performance of Malaysian buildings and validate technological innovation in energy efficiency and ESG performance. Li and Darko (2025) empirically demonstrate, in their evolutionary game model analysis of energy efficiency strategies, that governments’, corporations’, and markets’ cooperation strategies maximize energy efficiency and reflect stakeholder interactions in ESG strategy design. Green financing's specific beneficial impact on energy carbon neutrality has been found in research by Lou (2025) and reflects the critical influence of financial system integration on the ESG energy transition. Empirical evidence of the relationship between ESG performance factors and energy efficiency and profitability has been provided in studies by Madwe et al. (2025) and Burinskienė et al. (2025), reflecting the ESG performance strategy's overall "double dividend" of improved energy sustainability and profitability. A new energy-sharing strategy using Nash Negotiation has been proposed by Wang et al. (2025), suggesting ESG performance strategy value-creation collaboration. At the same time, Yücel (2025) assesses greenwashing and legitimacy risks in ESG performance and energy transition strategy data, and reflects on the integrity of ESG strategy data. Yu et al. (2025) also outlined approaches to validating and improving the accuracy of energy ESG performance strategy data, the impact of text mining on energy ESG performance strategy data, and the validation of strategy synergies with the United Nations' sustainable development goals. Final considerations emphasizing human subcapital, digital skilling in energy, and the validity of ESG strategy success and performance have been provided in Ragazou et al. (2025). Collectively, these findings point to a fundamental message: for a sustainable energy transformation, a systemic integration of governance, financing, technology, and human capabilities is required. In an ESG context, energy efficiency stands out not only as a technological tool but also as a strategic approach that promotes sustainability and resilience. In terms of fiscal incentives aimed at energy efficiency savings and emission cuts, for example, Wu & Min (2025) found that these measures not only contribute to energy savings but also further improve the effectiveness of green technology innovations, establishing a direct link between national energy policies and enhanced ESG progress in corporations. Similarly, in a study by Mao et al. (2025), energy transition policies in China’s demonstration cities were found to result in notable ESG improvements, establishing a link between reduced fossil fuel dependence and enhanced ESG performance. Liu et al. (2025) and, further, a separate study by Khan et al. (2025) confirm this link by showing that digital transformation policies further improve a firm’s effectiveness in energy resource management and ESG alignment. This association is further defined by Mengyuan et al. (2025) as an ESG risk assessment framework specific to the energy sector, with yardsticks provided for evaluating the sustainability of energy production and consumption. In addition, evidence at the macroeconomic level by Zhang et al. (2025) indicates that improved corporate ESG performance due to energy transitions leads to greater social welfare benefits, while Wang and Wang (2025) suggest that specific green bonds and carbon pricing instruments direct investments towards low-energy and low-carbon strategies. Adaptive ESG policies to manage energy transitions are a critical imperative for balancing the energy and climate challenges discussed by Narayan et al. (2025) for emerging countries. Supporting evidence on AI and cloud-based solutions by Niu et al. (2025), Zhou et al. (2025), and Aljohani (2025) suggests improved energy efficiency and greater environmental disclosure on ESG statements. Companies following best ESG energy management policies have also demonstrated reduced capital expenditure (Wilberg et al., 2025), thus explicitly confirming that economic benefits, along with ecological advantages, support energy sustainability. Mufungizi and Mpaka’s (2025) study demonstrates ESG integration in the Congo DR’s mining industry, turning resource extraction into sustainable energy consumption, proving that quality governance decreases the energy intensity of resource extraction. Kiran et al. (2025) examine ESG investments in G8 countries and conclude that ecological sustainability is enhanced through clean production and efficient energy resource allocation, demonstrating that quality governance moderates the effect of energy consumption on the environment. Jin’s (2025) ESG-conformal investment in SMEs boosts green economic revival and sustainable resource innovation, while Liu et al. (2025) detail an optimization approach for micro-grid-scale energy consumption, demonstrating that intelligent planning can achieve an optimal ESG approach through zero waste and maximum renewable energy consumption. ESG performance is further confirmed in global financial planning through improvements in market value and sustainability assessments in the energy and utility sector when efficient energy consumption is implemented, as demonstrated by Christine et al. (2025). At a governance level, Zournatzidou et al. (2025) discuss threshold effects of ESG performance and energy policy efficiency in Europe. It is inferred that better ESG performance is directly related to more efficient energy use. On the contrary, Singh and Arora (2025) argue that companies with strong ESG performance could potentially mislead on energy efficiency. Gao et al. (2025) discuss greenwashing practices in electric cars and found that inefficient ESG performance misleads about efficient energy output. Authors such as Kweh et al. (2025) and Wieteska-Rosiak (2025) demonstrated that ESG practices and sustainable design achieve greater energy efficiency and resilience in European cities, and reiterated that efficient energy use is a prerequisite for achieving good ESG performance. Sorrosal-Forradellas et al. (2025) demonstrated that, through financial and sustainability performance strategies in investment funds, energy-efficient investment is possible and aligns with the ESG energy strategy. Costanzo et al. (2025) discussed the use of cyclical resources for fertilizers derived from organic wastes, which reduces energy intensity and, conversely, promotes environmental and economic aspects of ESG performance. Sklavos et al. (2025) discussed green accounting in European financial institutions and demonstrated that efficient energy use and ESG performance are directly correlated with financial performance metrics. Magaletti et al. (2025) extend the lesson to the construction industry and observe a significant energy-savings potential from the use of decarbonization strategies informed by ESG factors. Veisi (2025) finds that the increased use of corporate sustainability reports in the Wisconsin region increasingly aligns energy transition strategies with climate governance. Riti et al. (2025) and Dong et al. (2025) indicate that the increased use of AI and innovation networks improves companies’ ESG performance by encouraging the use of energy-efficient strategies and green technologies. Jin et al. (2025) offer additional insights into the increased use of energy efficiency credit guidelines as a boost to low-carbon innovation and ESG performance. Alkhalifa (2025) expresses reservations about treating LEED as a proper proxy for energy-related ESG factors. Fu et al. (2025) observe an increased reliance on globalization in the diffusion of green technologies. Lastly, Gao et al. (2025) observe an increase in the use of effective ESG performance to augment total factor productivity in the energy company sector. See

Table 1.

3. Methodology, Data and Theoretical Background

The research aims to use the intersection of panel data econometrics, unsupervised clustering, and machine learning techniques to investigate the role of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors, particularly the Environment dimension, in influencing energy use normalized for population (ENUS) across countries. This will be done by adopting recent research recommendations that call for the complementary use of econometric techniques and data-driven approaches for modeling sustainability trends in the energy arena (Davidescu et al., 2025; Saltık, 2024). To make trends comparable across nations, the research will use the World Bank's World Development Indicators dataset. This will provide a consistent framework for modeling, enabling the estimation of nearly 1,965 observations from an unbalanced panel of up to 127 countries over approximately 17 years. This will provide sufficient flexibility to capture structural heterogeneity and time-series variability for the respective sets of factors related to the environment, institutions, energy, etc., in conformity with global ESG rating systems (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024; Laureti et al., 2023). In terms of methodologies, the empirical approach consists of three consecutive steps. In the first stage, econometric panel-data models with FE, RE, and Weighted Least Squares (WLS) estimators are used to estimate the structural link between ENUS and ESG factors. The FE model accounts for unobserved country-specific characteristics, such as geography and energy resource endowment, reflecting the importance of effective governance as a driver of ESG performance (Laureti et al. 2023). The WLS technique is used to treat heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence. Additionally, Hausman tests for FE reliability show that FE is more accurate and robust theoretically than other tests (Hausman), complementing current trends toward using econometric models in the ESG-energy literature (Davidescu et al. 2025). The second stage uses the K-Means algorithm in Unsupervised Machine Learning to discern environmental regimes in which energy use is correlated with Emissions, Climate Stressors, and Resource Use. The paradigm is consistent with current classification systems associated with sustainability and environmental conditions (Onomakpo 2025; Costantiello & Leogrande 2024). The algorithmic clustering is verified using Silhouette Scores, CH Scores, and Herfindahl Indices to form ten well-balanced subsets for exercising ten distinct ESG-energy regimes—ranging from energy-intensive to low energy and renewables-based. The third stage relies on Machine Learning to determine how different statistical models can forecast ENUS values. This paradigm is consistent with algorithmic studies toward establishing relevance to apply Machine Learning to further investigate nonlinear associations of ESG-ENUS (Davidescu et al. 2025) (Saltık 2024). The best-performing algorithm is established using Normalization across MSE, RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and explanatory strength (R-Squared) for K-Nearest-Neighbor (KNN). Additionally, Dropout loss helps determine the marginal contributions of select ESG variables to ENUS predictions. These include CO₂ Emissions, Energy Efficiency, Waste Generation, and Water Withdrawal. Theoretical rationales: Specifically, ESG sustainability factors place energy use within a nominated framework, where energy use is understood in terms of its relationship with economic and environmental stress. The Environment factor captures relationships among energy management, energy efficiency, and greenhouse gas emission intensity within the nominated ESG adoptability and applicability frameworks (Onomakpo, 2025; Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024). The nominated methodological approach employs econometric models, machine learning algorithms, and clustering methods in its design and implementation (

Figure 1).

4. Energy Use and the ESG Environmental Pillar: Evidence from Panel Data, Machine Learning, and Clustering

4.1. Environmental Pillar of ESG and Energy Use: Evidence from Cross-Country Panel Regressions

This section examines the empirical relationship between the Environmental pillar of the ESG framework and per capita energy use (ENUS) through a set of panel data regressions. By focusing on a comprehensive set of environmental indicators related to resource use, emissions, land dynamics, and energy structure, the analysis aims to capture the multidimensional nature of the E-Environment component and its influence on national energy consumption patterns. The estimated models provide insight into how environmental pressure, efficiency, and sustainability-related factors jointly shape energy demand across countries and over time. We have estimated the following equation:

The above empirical model may be conceptually broken down as a mega panel data study on the impact of the Environmental pillar of the ESG paradigm, henceforth referred to as ‘E-Environment,’ on energy consumption as measured by the dependent variable ‘ENUS.’ This empirical methodology is compatible with a paradigmatic shift in related research towards emphasizing the importance of environmental pillars of ESG values on economic, financial, and energy-related outcomes as cited by recent publications (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Manjengwa et al., 2025; Tutar et al., 2025). All the other variables have been taken from WorldBank datasets to add global validation and consistency, along with ‘gold standard’ level credibility to related data as followed by recent empirical paradigm study publications on related topics involving ESG variables (Farooq & Thavorn, 2025; Abbas et al., 2025). In this study, there are 127 cross-sections appearing likely to be countries, which have likely followed an unbalanced panel study period configuration having a maximum period of 17 years, hence giving rise to a total observation level of 1,965 observations. Conceptually, E-Environment in ESG research includes natural resource management practices, emissions, ecosystem integrity, and climate-related stresses. This conceptually inclusive perspective aligns with the existing ESG research context on the joint influence of environmental variables in measuring sustainability pressures and risks associated with transitioning factors (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Tutar et al., 2025). The variables selected in the regression analysis represent the inclusive perspective. Variables such as electricity access, fossil fuel energy use, renewable energy variables, greenhouse gas emissions, land use change, and water withdrawal rates together represent the nexus between the state of the environment and the demand for energy. Thus, ENUS is not simply conceptualized in the economic context but at the nexus of the structural relationships existing between environmental sustainability and the energy domain—referencing similar insights from research on ESG variables and energy transition variables and environmental pressure variables respectively (Sharipov et al., 2025; Onomakpo, 2025). The estimation of the model uses three different panel data approaches with a focus on a fixed-effect estimator, a generalized least squares method using the Nerlove transformation, and a weighted least squares approach assuming unit-specific error variance. This multi-method estimation approach not only increases the robustness of the research, allowing for a clear comparison of the stability of coefficients across estimation methods, a methodological approach typically used in ESG-oriented panel data studies (Aslan-Çetin et al., 2024; Manjengwa et al., 2025). Furthermore, with high levels of country-specific heterogeneity, a fixed-effect approach becomes very relevant, where the empirical estimate controls for all time-invariant country-specific characteristics, such as geography, institutional structures, energy endowment, and development path. Based on the fixed-effect estimator, the result depicts a high level of goodness of fit, where the LSDV R-square is well above 0.99, while the within R-square approaches a value of 0.69. This scenario depicts a situation where the time-series fluctuations of E-Environment variables contribute a considerable share of changes in energy use, across different economies. Joint significance of the regressors can be established using the F-statistic for joint restrictions of coefficients; where p-value approaches zero, confirming the influence of E-variables on ENUS, consistent with the established evidence on ESG’s role on real-world outcomes (Farooq & Thavorn, 2025; Abbas et al., 2025). Electricity access is revealed as an important factor influencing energy consumption for all models. With a positive and strongly significant result, increased access to electricity is associated with increased aggregate energy consumption. From the ESG perspective, this finding points to the importance of an underlying trade-off for the environmental factor: while increased access to modern energy services is required for proper social development and inclusion goals, the potential stress-related impacts for the environment, depending on the underlying energy mix, might be increased. These trade-offs have been indicated by various studies investigating the link between ESG performance and sustainable developments in new and developing countries (Manjengwa et al., 2025; Sharipov et al., 2025). The CAGR-Value-Added sector shows a persistently negative coefficient, indicating that economies with a more primary-oriented structure present lower energy availment levels once country-specific variations are accounted for. Under the ESG paradigm, this indicates that environmental performance is to be understood from its structural angle, where sectoral differences matter for energy availment trends (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Tutar et al., 2025). Annual Water Withdrawals present a positive and significant correlation with ENUS, thereby attesting to the well-known nexus between water withdrawal and energy availability. The stated finding is supportive of ESG-approach dwellings that continuously recognize natural resource extraction and energy systems’ well-known interconnectedness (Abbas et al., 2025; Onomakpo, 2025). The per-capita carbon dioxide emission shows one of the largest coefficients in the model. The strong positive relationship between carbon dioxide emission and energy usage indicates the continued entrapping relationship between the two, thereby indicating less global decoupling. According to the environmental pillar of ESG, the intensity of emission is a fundamental constituent of environmental sustainability (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Farooq & Thavorn, 2025). The energy imports are depicted with mixed indicators in terms of specifications, owing to the complexities entailed in energy security in the E-Environment category. With the concerns of heteroskedasticity and across-country variance taken into full consideration, the negative coefficient in the weighted least squares equation indicates that import dependence can influence efficiency increases through activities made possible by structural constraints on consumption, which aligns with contemporary research on energy risk and sustainability transitions (Sharipov et al., 2025). The energy intensity of primary energy is positively and significantly correlated with ENUS under all models, thereby validating that energy inefficiencies directly correspond to increased levels of consumption and implying that energy efficiency remains a key component of ESG-based sustainable energy funds (Abbas et al., 2025; Matsali et al., 2025). The consumption of fossil fuel energy has a negative coefficient, potentially implying substitution/saturation patterns net of emissions and aggregate energy consumption. This finding illustrates that it is essential to consider and fully understand a series of E-Environment variables simultaneously and not in aggregate or isolated fashion, particularly within integrated frameworks of comprehensive ESG analysis (Tutar et al., 2025; Farooq & Thavorn, 2025). Emissions of greenhouse gases from changes in land use, forestry, methane, nitrous oxide, and tree cover loss are positively associated with ENUS, thereby offering evidence that various forms of environmental degradation are sequential patterns concurrent with increments of energy consumption. Such a finding and pattern validate that previously assigned principles incorporating holistic and integrated measures of ESG-based sustainable investments continue to effectively explain that variables associated with environmental pressure measures directly relate and interact systematically and not in opposition or offsetting patterns (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Abbas et al., 2025). On balance, the above discussion highlights that the proposed model delivers robust support to the hypothesis that E-Environment factors of ESG variables demonstrate significant impacts on energy use. Using World Bank data, this proposed study confirms that no energy transition research could be accomplished effectively without taking into consideration the environment factors identified through ESG variables, which supports current research on ESG topics (Manjengwa et al., 2025; Tutar et al., 2025; Onomakpo, 2025). See

Table 2.

4.2. E-Environment Typologies and Energy Demand: Evidence from K-Means Clustering

This simple empirical model set up in this study could be considered an extensive panel analysis concerning the large-scale impacts of the ESG Environmental pillar, from now on referred to as E-Environment, on energy consumption, represented here through the dependent variable ENUS. This type of analysis is in accordance with a contemporary and increasing stream of ESG models and theories that attribute a pivotal role to environmental aspects in ESG regarding economic, financial, and energy performance (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Manjengwa et al., 2025; Tutar et al., 2025). All of the model's independent variables are taken from World Bank sources in this study, which is a strategy aiming at universality and consistency in methods and accuracy in derived facts and figures in this ESG empirical analysis, a strategy increasingly used in contemporary ESG empirical models and papers (Farooq et al., 2025; Abbas et al., 2025). The analysis includes 127 cross-sectional entities possibly representing countries, in an unbalanced panel, of maximum 17-year length, totaling 1,965 observation sub-units in general. On a conceptual level, E-Environment covers natural resource management, emissions, ecosystem integrity, and climate-related stressors in the ESG dimension. This multi-faceted view is in line with ESG research, which points to environmental factors collectively indicating pressures towards sustainability (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Tutar et al., 2025). The regressors considered take this multifaceted approach. These regressors, access to electricity, the use of fossil fuel energy, renewable energy variable indicators, greenhouse gas emissions, land use change, and water withdrawal, provide information on how environmental states or performance intersect with energy demand. On this basis, the value of ENUS can be considered neither economic performance alone nor the predicate variable but rather influenced by structural relationships between environmental sustainability pressures and energy patterns, reflecting findings in ESG, energy transition, or environmental-pressure indicators (Sharipov et al., 2025; Onomakpo, 2025). Model is estimated using three different panel models of fixed effects, random effects using Nerlove transformation for Generalized Least Squares, and Weighted Least Squares with unit-specific variance of errors. The procedure provides stronger robustness of results and also allows comparison of coefficients' stability across different models. Such methodological design aligns better with common practices of applying panel models in relation to an ESG focus (ASLAN-ÇETİN et al. 2024; Manjengwa et al. 2025). The fixed-effect method appears particularly appropriate due to significant N heterogeneity and encompasses all time-invariant country characteristics that encompass geography, institutions, and energy resources that influence economic development. The fixed-effect results confirm outstanding explanatory models with an LSDV-R-squared of over 0.99 and Within-R-squared of approximately 0.69. This confirms that temporal changes of E-Environment variables strongly influence changes in energy use. The joint insignificance of variables was also supported by an F-test with an effective p-value of 0 and strongly confirms that environmental variables strongly influence ENUS, which aligns well with other research that confirms strong interrelations between ESG environmental variables and various economic and energy variables (Farooq & Thavorn 2025; Abbas et al. 2025). Electricity access is observed to play a major role as a driver for energy consumption for all models and specifications. This is indicated by the strongly positive and significant result that demonstrates that increased access to electricity is accompanied by increased total energy consumption. From an ESG analysis standpoint, the contribution of this result underscores the importance of the persisting trade-off that requires increased access within the sector for sustainable social development and inclusive growth, thereby simultaneously enhancing potential environmental pressures based on the prevailing energy sources and mixes (Manjengwa et al., 2025; Sharipov et al., 2025). The value added by agriculture, forestry, and fishing reveals a persistently negative coefficient, implying that more economy-specific emphasis on the primary sector is associated with lower energy use per capita once country-specific factors are adjusted for. Within the context of the ESG approach, this result points to the existence of the structural aspect of environmental behavior, wherein the sectoral composition of the economy underlies energy demand patterns (Lapinskienė et al., 2023 & Tutar et al., 2025). Annual freshwater withdrawals are positively and significantly related to ENUS, thereby establishing the strong relationship that exists between water withdrawal and energy use. This study's result is consistent with the water-energy nexus and affirms the study approach underpinned by the principles of ESG strategies, which emphasize water and energy system dependencies and interlinkages related to natural resource extraction and energy use practices (Abbas et al., 2025 & Onomakpo, 2025). The CO2 emissions per capita has one of the highest coefficients in the equation. This clearly points towards a close link between energy consumption and emissions, indicating a less-developed phenomenon of global decoupling. This result is completely consistent with the ESG framework’s environment dimension, in which the intensity of emissions serves as a key determinant for the measurement of sustainable risks (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Farooq & Thavorn, 2025). The energy import variables have mixed results in terms of sign. However, taken on its own and incorporating all aspects of heteroskedasticity and cross-sectional variability of variables, energy imports' negative coefficient on weighted least squares appears to impose efficiency-enhancing practices and/or structural constraints on energy use in line with latest research on energy policy risks and sustainable transitions (Sharipov et al., 2025). Energy intensity of primary energy has a positive and significant relationship with the ENUS, thus confirming that the effects of a less efficient energy sector translate to increased levels of consumption, and the need for efficiency measures remains at the forefront of sustainable energy policies based on ESG ideologies (Abbas et al., 2025; Matsali et al., 2025). Consumption of fossil fuel energy has a negative coefficient, possibly due to the effects of substitution or saturation after controlling for the variables of emission and total consumption levels. This further supports the need for a combined understanding of E-Environment variables, as is the practice in ESG analysis (Tutar et al., 2025; Farooq & Thavorn, 2025). Finally, emissions of LUC, forestry, methane, nitrous oxide, and tree cover loss share positive correlations with ENUS, implying that processes of environmental degradation correlate with energy use. These findings confirm ESG-related views that environmental pressures share a systematic relationship in ESG analysis, which are not offset by one another (Lapinskienė et al., 2023; Abbas et al., 2025). To sum up in the form of a conclusion, the model developed affirms the strong influence of the E-Environment constituents of the ESG framework on energy use. This is owing to the group of variables consisting of environmental pressure indicators, emissions variables, resource exploitation variables, and efficiency variables. Based on the world bank data and the use of a panel approach in the research, the conclusion affirms the growing idea in the field of ESG research studies today (Manjengwa et al., 2025; Tutar et al., 2025; Onomakpo, 2025). See

Table 3.

Under the ESG framework, and specifically within the E–Environment pillar, the K-Means clustering results can be interpreted as a set of distinct environmental “regimes” that describe how energy use per capita (ENUS) co-moves with key environmental, climate, and energy-system variables. This interpretation is consistent with recent applications of clustering techniques to environmental and energy data, where unsupervised methods are used to uncover latent sustainability patterns and development pathways (Krstić, 2023; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025; Noviandy et al., 2024). Because the reported cluster centers are standardized, positive values indicate above-average levels relative to the full sample and negative values indicate below-average levels. Read in this way, the clusters do not merely segment countries (or observations) statistically; they outline different combinations of energy consumption, emissions profiles, climate conditions, and environmental pressures that can be understood as ESG-relevant typologies, as suggested in multidimensional ESG and sustainability analyses (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024; Saltık, 2024). A first important result concerns the balance and usability of the partition. Cluster sizes range from 54 to 451 observations, with no single cluster absorbing the majority of the sample. This is important for environmental interpretation because it suggests that the solution is not driven by one dominant “global average” group; instead, it captures multiple meaningful environmental patterns associated with ENUS. Similar balanced clustering structures have been highlighted as desirable in comparative environmental and development studies using K-Means (Noviandy et al., 2024; Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025). The within-cluster heterogeneity shares are relatively similar across the main clusters (especially clusters 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7), indicating that K-Means distributes explanatory structure across several clusters rather than concentrating it in a single group. The silhouette scores reinforce this interpretation: several clusters show reasonably good separation (notably clusters 2, 5, 8, and 10), suggesting that some environmental regimes are clearly distinct in the underlying feature space, in line with best practices in clustering-based environmental diagnostics (Krstić, 2023; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025). Focusing on ENUS and its relationship with environmental indicators, the centroids immediately identify clusters with high-energy, high-pressure profiles. Cluster 8 is the most extreme case, with ENUS strongly above average and similarly very high values for CO₂ emissions per capita (CO2P) and other environmental stress indicators, including large positive values for PM2.5 and waste-related measures (WSTR). This combination is consistent with an “energy- and emissions-intensive” regime, where high energy consumption is closely linked with elevated pollution burdens and greenhouse gas emissions. Comparable high-impact clusters have been identified in studies examining emissions-intensive development paths and carbon-intensive regimes using clustering approaches (Lee et al., 2025; Krstić, 2023). From an ESG perspective, this cluster can be read as a high environmental risk profile in which energy use translates into multiple forms of environmental pressure rather than being mitigated by cleaner technologies or systemic efficiency, a concern emphasized in ESG-based energy sector analyses (Saltık, 2024). Cluster 10 also exhibits an above-average ENUS centroid, together with a high CO2P centroid and positive values on several climate-related variables. Compared with cluster 8, the pattern appears less extreme but still reflects a development trajectory characterized by high per-capita energy demand and associated emissions. Together, these clusters highlight a core message of the E pillar: high energy use is rarely environmentally neutral, and clustering results suggest that it often coincides with higher carbon intensity and broader environmental burdens for specific groups of observations. This finding is consistent with cross-country clustering evidence on emissions drivers and energy use (Lee et al., 2025; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025). At the opposite end of the spectrum, clusters with below-average ENUS—such as clusters 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7—represent lower-energy regimes, but they are not environmentally homogeneous. Cluster 2 combines low ENUS with strongly negative values in several energy-system variables, indicating a low-consumption profile that may reflect limited industrial energy demand, lower electrification, or structural conditions associated with less energy-intensive development. Similar low-energy clusters have been documented in environmental and development-focused classification studies (Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025). Cluster 5 shows below-average ENUS while featuring very high values in variables related to natural capital (such as FRST), suggesting a regime where energy use is relatively low and ecological endowments are strong, a pattern consistent with natural-capital-oriented environmental typologies (Noviandy et al., 2024). Cluster 7 also displays low ENUS but stands out for strong positive values in renewable-related indicators (RENC) and other environmental variables, implying a low-energy profile potentially aligned with cleaner energy structures or stronger environmental performance, as observed in studies linking renewable intensity and environmental outcomes (Lee et al., 2025; Saltık, 2024). A particularly informative result is that the clustering distinguishes between cases where low ENUS is associated with environmental advantage and cases where low ENUS coexists with other forms of environmental stress. For example, some lower-ENUS clusters still show positive values in pollution-related indicators such as PM2.5 or in greenhouse gases other than CO₂, suggesting that low energy use does not automatically imply superior environmental outcomes. Conversely, clusters with higher ENUS differ markedly in their environmental signatures, indicating that the relationship between energy use and environmental impact is mediated by factors such as energy mix, technology, and environmental regulation. This heterogeneity echoes recent ESG research emphasizing that environmental performance depends not only on consumption levels but also on structural and regulatory conditions (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025). Finally, the silhouette results help identify which environmental regimes are most clearly separated and thus most reliable for interpretation. Clusters with higher silhouette values, such as clusters 2, 5, 8, and 10, represent more coherent and internally consistent environmental typologies, whereas clusters with lower silhouette values, such as cluster 1, may capture transitional or mixed regimes. This distinction is particularly relevant for ESG reporting and benchmarking, where clarity and stability of classification are essential for policy and investment applications (Saltık, 2024). Overall, the K-Means solution provides a balanced and interpretable typology of environmental profiles linking energy use per capita to emissions, pollution, climate conditions, and energy-system characteristics. The clusters demonstrate that ENUS is embedded within broader environmental regimes: some are clearly high-energy and high-impact, others combine low energy use with strong natural capital or renewable signals, and several occupy intermediate positions where energy use and environmental pressures interact in more nuanced ways. This multidimensional segmentation is therefore especially useful for ESG-oriented comparative analysis, as it moves beyond single indicators and captures complex environmental patterns associated with energy use (Krstić, 2023; Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025; Saltık, 2024). See

Table 5.

Within the ESG paradigm, specifically within the E-Environment domain, K-Means Cluster Analysis outcomes could be understood to identify a set of ‘regimes’ through which energy use per capita (ENUS) variables are jointly mapped. This resonates with contemporary practices of applying Machine Learning models, such as K-Means, to climate metrics, in which unsupervised algorithms are used to identify hidden trends in sustainable development (Krstić, 2023; Jiménez-Preciado, 2025; Noviandy et al., 2024). As K-Means clusters are standardized, positive value indices indicate values above the mean of a variable sampled from a broader set of observations, whereas negative indices indicate values below the mean. Thus, understood in their broader perspective, these are more than statistical patterns based on country-identifiers of observations. Set within an alternative paradigm, rather, these could be understood to be coordinated patterns of energy use and emissions levels, climatic factors, along with ‘pressures’ upon this environment—that could be classified within an alternative set of ESG paradigm ideas, specifically upon zones of multidimensional climate-sustainability patterns (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024; Saltık, 2024). A major finding concerns the balance and interpretability of the partition. The cluster sizes range from 54 to 451 cases, and no cluster contains the majority of the data. Being of environmental significance, this means that instead of focusing on a single major “global average” type of group, this solution identifies several significant environmental patterns related to ENUS. Such balanced clustering patterns have previously been identified as important for comparable environmental and developmental research using K-Means (Noviandy et al., 2024; Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025). The shares of within-cluster dispersion are quite balanced among the major clusters (especially clusters 1, 3, 4, 6, and 7), suggesting that K-Means is allocating model-explaining structure to several clusters concurrently instead of allocating to a single group. The Silhouette measures further underscore this finding and point to several clusters (especially clusters 2, 5, 8, and 10) being able to discriminate relatively well in a suitable manner (among environmental regimes specifically) in accordance with proper clustering for environmental analysis (Krstić, 2023; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025). Regarding ENUS and its correlations with environmental variables, the centroids easily distinguish high-energy, high-pressure patterns. Cluster 8 stands out as a clear example, where not only is ENUS well above the mean, but CO₂ emissions per capita (CO2P) and various other measures of environmental stress, including very positive values for PM2.5 and waste measures (WSTR), are correspondingly extremely high. Together, these factors can be categorized as a specifically "energy- and emissions-intensive" regime, in which energy use is strongly correlated with high levels of both polluting loads and greenhouse gas emissions. Clusters of this kind have appeared in research on emissions-intensive development patterns and carbon regimes employing clustering analysis techniques (Lee et al. 2025; Krstic, 2023). For ESG, this cluster can be considered a high-risk cluster for the environment, where energy use feeds into various forms of negative, non-mitigated factors, a pattern highlighted in energy sector ESG research (Saltik, 2024). Cluster 10, by contrast, features a high positive centroid on ENUS, a high positive centroid on CO2P, and positive measures on a variety of climate variables. Compared to Cluster 8, a more similar, though still high, pattern emerges, suggesting a development pathway associated with high energy demand and corresponding levels of emissions. These clusters, together, reinforce one of the pivotal points of the E pillar of the research framework, namely, energy demand will often be difficult to act on from an environmentally neutral perspective, being instead strongly associated with various levels of carbon intensification, as well as corresponding levels of environmental repositories in a set of pattern-specific observations. These observations concur with cross-country research assessments, specifically regarding patterns of energy demand and emissions (Lee et al. 2025; Jiménez-Preciado et al. 2025). On the other hand, with ENUS scores below average, clusters such as 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7 represent low-energy regions. However, environmental homogeneity is not present in these groups. In particular, Cluster 2 shows low ENUS values and highly negative values for energy system variables. Hence, there is evidence of a low energy-consuming pattern. Likewise, similar low-energy-consuming clusters have been previously established for environmental development classification (Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025). Another case is Cluster 5 with low ENUS values and very high values for natural capital-related variables (e.g., FRST). Consequently, there is evidence of a low-energy-consuming pattern, yet natural capital is very high. This supports natural capital environmental typologies (Noviandy et al. 2024). Cluster 7 is characterized as low ENUS with very high values for renewable energy-related variables (RENC) and other environmental variables. Thus, there is evidence for a low-energy-consuming pattern. This is potentially similar to cleaner energy structure regions or regions with improvements regarding environmental performance (Lee et al. 2025; Saltık 2024). One of the most enlightening outcomes is the clustering analysis's ability to differentiate between regions with low ENUS values accompanied by an advantage in the environment and those with lower ENUS values accompanied by different sources of environmental stress. Take, for instance, the reduced ENUS clusters with values that continue to register positively for indicators such as PM2.5 and greenhouse gases other than CO₂, indicating that while the region may have low energy use, this is not necessarily a hallmark of enhanced environmental performance. On the other hand, new clusters with greater ENUS show greater variation in the environmental variables, indicating that the interaction between energy and the environment is mediated by the underlying energy composition and environmental policies and structures (Costantiello & Leogrande, 2024; Jiménez-Preciado et al., 2025). Finally, the silhouette analysis outcome also enables the determination of which groups are more distinguishable in the environment and can be considered for more reliable interpretation. Groups with high silhouette coefficients, such as 2, 5, 8, and 10, can be considered more homogeneous with respect to the environment classification. On the other hand, groups with a low coefficient value, such as group 1, may represent a transitional state or a mixture of environments. This takes on a more specific form in the context of ESG reports and benchmarks, where a clear interpretation is needed. In summary, the K-Means solution provides a balanced and meaningful typology of environmental profiles connecting ENUS to emissions, pollution, climate factors, and energy system types. These clusters show that ENUS is situated within larger environmental systems, some of which are obviously high energy and high impact, some of which match low energy use to strong natural capital or renewable factors, and others of which are situated in mid-range positions in which energy use and environmental pressure interact in more complex ways. This multidimensional segmentation approach is highly relevant to comparative analysis for its ESG focus, as it looks beyond simple indicators to more complex environmental patterns related to energy use (Krstić, 2023; Mendoza-Mendoza et al., 2025; Saltık, 2024). See

Table 6.

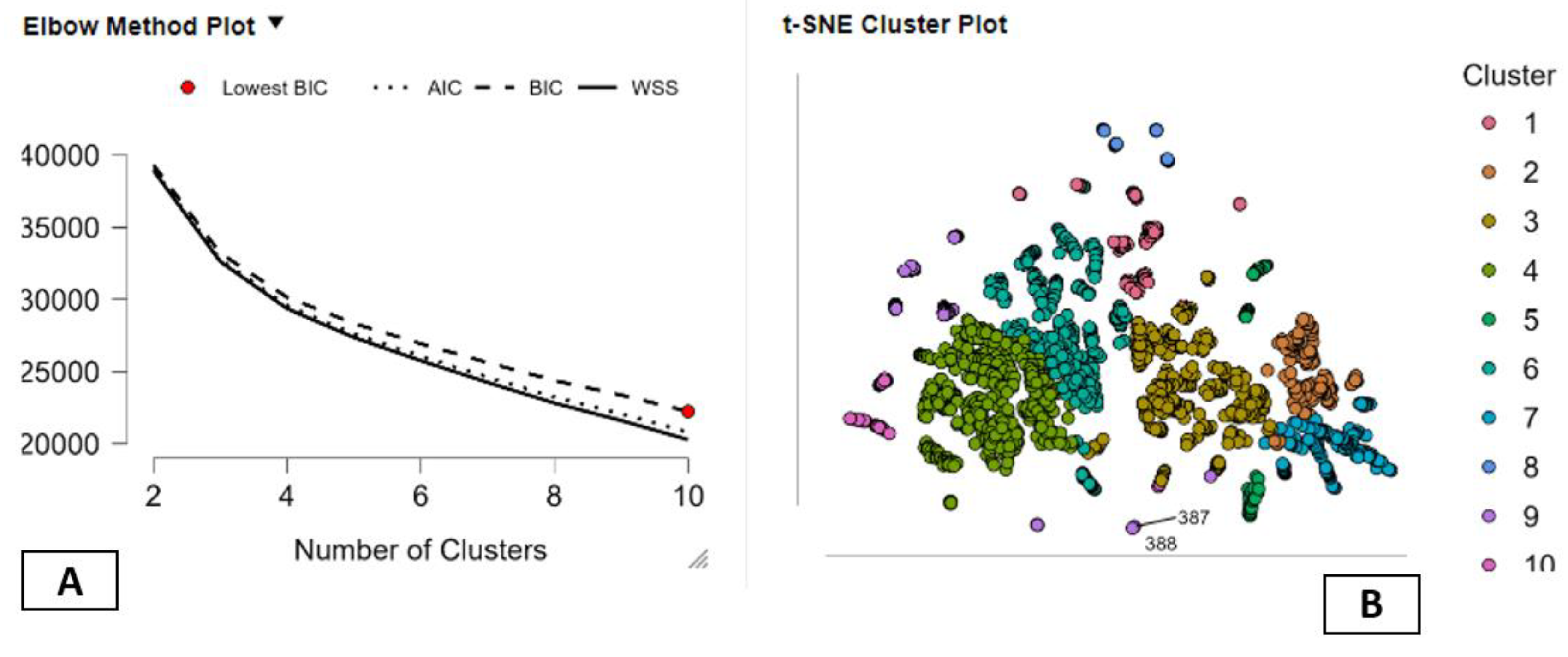

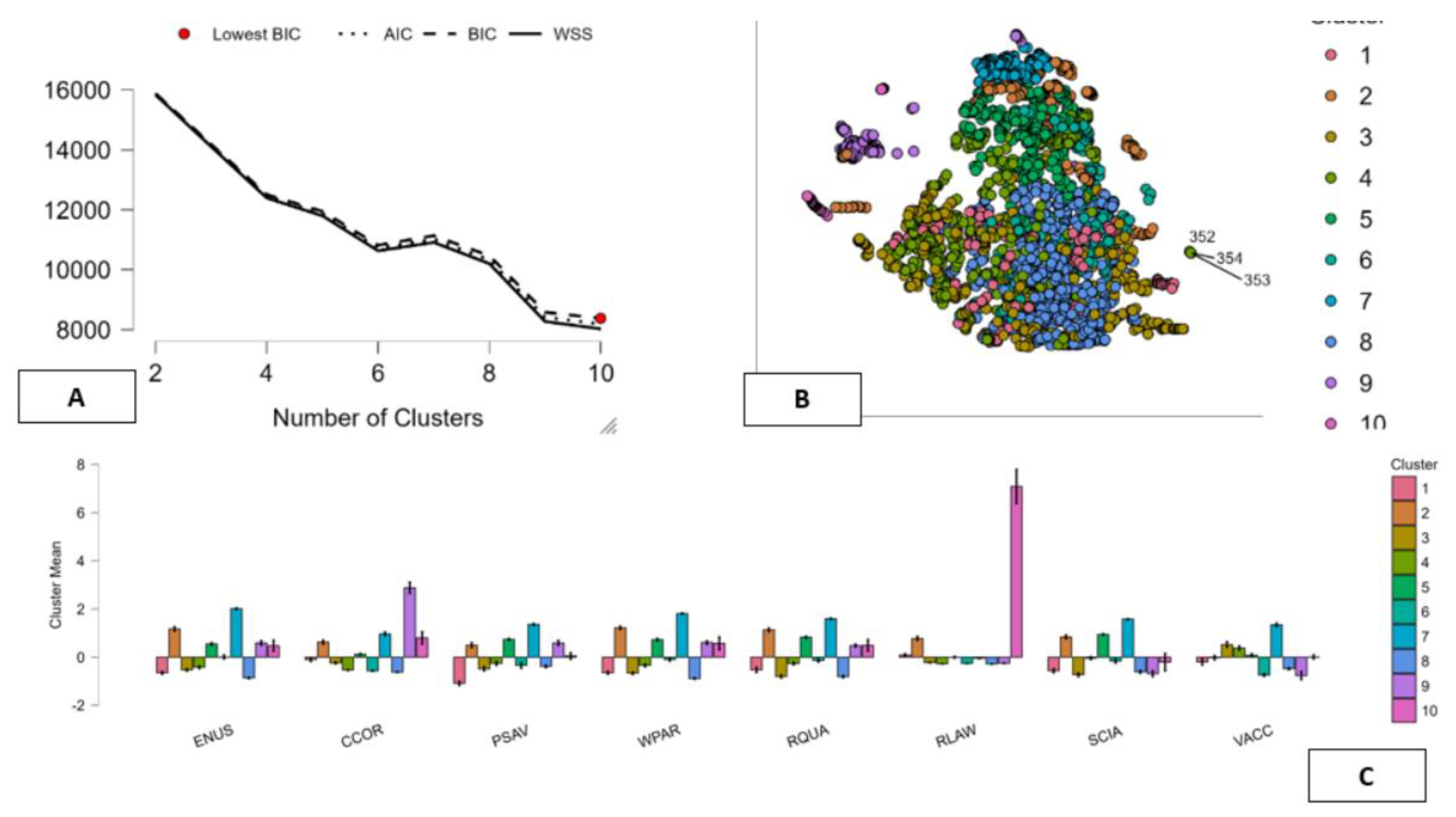

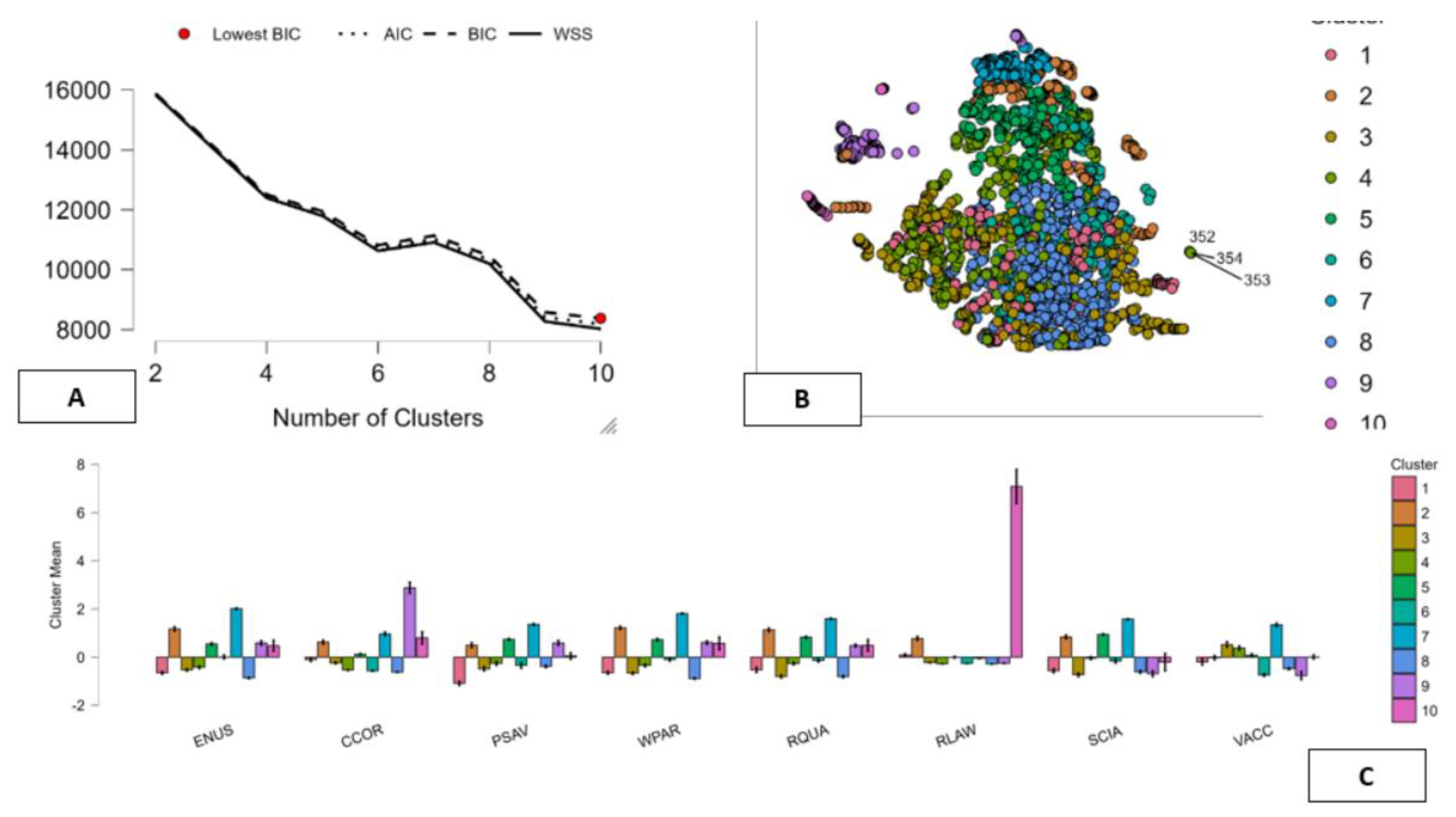

This figure brings together two different perspectives which complement each other to form a basis for determining and validating the optimal number of clusters in K-Means analysis through the use of statistical measures in determining model goodness of fit and the analysis of cluster morphology through visualization. Panel A of this figure offers an explanation of the process of determining optimal cluster numbers through an Elbow Method plot where cluster number is depicted on one axis versus various measures of goodness of fit, including Within-Cluster Sum of Squares (WSS), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) on the other axis. These curves all reduce in intensity with an increase in cluster number, which is an indication of an increase in precision of fit through grouping of points into smaller clusters, though at a rate where increasing benefits of further clustering start to be diminished. The point of inflexion at which BIC is at its least (at around ten clusters) is the most significant point and is an indication that this is a statistically optimal clustering solution where further clustering is unnecessary since additional clusters tend to increase overall model complexity rather than enhance goodness of fit. Since BIC is a criterion where complexity is strictly penalized compared to WSS, its trough is an optimal solution that seeks to ensure a balance in explanatory power rather than mere parsimony. Panel B of this figure presents a two-dimensional t-SNE plot of clustered data for further visualization and interpretation of clusters. Each point in this graph is represented in a cluster, and this is used to determine an insight into cluster separation and distinctness. It is realized from this graph that each cluster tends to be distinct and separate in this two-dimensional graph, though some appear to be more dispersed than others. However, all clusters seem to be distinct and separate and do not, in large numbers, appear to be overlapping or identical, which is an indication of an optimal solution in clustering that does not suffer from redundancy and overlapping. See

Figure 2.

4.3. Machine Learning Performance in Predicting Energy Use per Capita within the ESG Environment Pillar

Within this section, the predictive capacity of different machine learning models used to estimate energy usage per capita (ENUS) is assessed, as included in the Environment part of the ESG model (Seow, 2025). To make all models eligible for comparison, this evaluation uses normalized, directionally consistent values to assess model accuracy and degree of adaptability, including both error reduction and model explainability rates. As part of this benchmarking exercise, this section proceeds to use the concept of dropout loss to evaluate and outline which variables of the environmental category impact overall prediction rates to the greatest extent, providing insight into those factors who lead to prediction differences within the estimate of ENUS in this multivariable and potentially complex setting of MRA study and application (Selmeya et al., 2025). This table displays predictive model rates for several prediction models assessed for overall normalized and directionally consistent set of comparative indicators for prediction models’ efficacy, mutually adjusted to represent better or improved values for all models and methods applied in prediction estimation and theory of knowledge and application of MRA principles for final predictions and results toward informed decision-making and estimate of better or improved models and methods to choose from for applications of efficient energy usage practices and models for better or improved estimations and estimates of theoretical and MRA approaches and principles related to optimal energy usage practices for global and/or predictive needs and applications of knowledge and principles of MRA theories and approaches and principles for better or improved estimations and predictions of energy needs and requirements for better or improved applications of MRA principles and approaches related to energy practices and usage (Seow, 2025). One of the first things to note is the spread of performance metrics for all models. It’s obvious that SVM underperforms, consistently scoring zero across all performance metrics, indicating the largest prediction errors and, correspondingly, the weakest explanations. This means that the SVM does not need to be considered further. Of all the models to be analyzed, it’s clear there are significant differences. Although Linear Regression and Regularized Linear models do not perform badly, their error metrics are relatively low, indicating that their R² values are obviously poor compared to those of non-linear models. This means that a linear model does not capture the underlying data process very well, resulting in relatively poor explanatory ability and a large prediction error (Almeida et al., 2024). Boosting and Decision Tree models show a considerable improvement over linear methods. Both methods show well-balanced but not outstanding results across all metrics, while, upon inspection, Decision Tree methods perform particularly well on MSE but less so on scaled errors and R² values. These models provide intermediate solutions—they improve forecasting accuracy relative to linear models but fail to outshine on all tasks specified within the entire list of evaluation criteria (Pence et al., 2024). Finally, it is apparent that Random Forest outperforms all other competitors. This model scores highest on normalized MSE and shows outstanding performance across all other metrics, indicating a model that effectively combines high predictive quality with low forecasting errors. Indeed, it is typical for higher-quality models to be more accurate and less prone to error across all the task sets mentioned earlier, especially for methods like Random Forest, known for their efficacy and resistance to noise and outliers (Ekinci & Ozturk, 2025). Therefore, it is proposed that Random Forest is a highly credible and balanced algorithm capable of making accurate predictions across all specified parameters. However, when all the parameters are considered together, it is apparent that the best-performing model is the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). This is because KNN supports the maximum values for all error-related parameters, such as scaled MSE, RMSE, MAE/MAD, and MAPE. This further reveals lower prediction error values than those of other models used. At the same time, it supports the maximum R² measure values. As such, it points to maximum explanation of the total variance of the dependent (Y) variable (Yasin et al., 2025). The simultaneous support for maximum/minimum variations on all parameters is quite appreciable. This is because it clearly distinguishes itself from other models. In this case, it does not compromise one objective to fulfill another. As such, it is reasonable to state that when both aspects of all parameters are appropriately addressed, KNN is clearly the best-performing procedure for predictions. The other model that actually supports moderate values is Random Forest. The rest support varying values on inferiority (Selmeya et al., 2025; Seow, 2025; Ekinci & Ozturk, 2025). See

Table 7.

The table mentioned earlier illustrates the average dropout loss for a set of environmental variables in the E-Environment domain of the ESG criteria, based on predicted energy use per capita (ENUS) values. The average dropout loss estimates the loss in predictive performance resulting from removing a variable from the prediction model. It indicates a direct contribution of the variable to ENUS prediction when a high value is obtained and a secondary contribution when a low value is obtained. The relevance of using estimates is more pronounced in the context of complex models. The estimate accounts for both direct effects and interaction terms simultaneously (Lee et al., 2025). The analysis reveals that the relative importance of various environmental drivers in energy consumption is unequal. CO₂ emissions per capita (CO2P) are identified as the most vital driver with a significant difference in importance. The very high dropout rate in CO2P indicates a strong relationship between energy consumption and carbon emissions. This result is consistent with the ESG literature, which shows that higher energy consumption linearly influences carbon emissions (Han et al., 2021). The dominance of CO2P in importance strongly supports that ENUS is not solely an economic and technological measure. Rather, it strongly emphasizes its importance in E (Drago et al., 2025). The following sets of variables with substantial influence include waste generation (WSTR), water withdrawal (AFWW), and energy efficiency (GEFF). The substantial influence of WSTR suggests that energy-intensive processes are linked to material intensity and waste generation. The finding suggests inefficient production and consumption patterns (Ferro et al. 2025). AFWW emphasizes the link between energy and water resources. Given that energy is used for production and consumption, its relationship to water resources is particularly emphasized. The substantial level of GEFF suggests focusing on energy efficiency as an intermediate factor influencing energy intensity. Variations in energy intensity separately affect energy intensity and its correlation with environmental pressures, thereby supporting energy intensity decoupling from environmental pressures (Dey et al. 2023). Environmental/climate pollutants also have a great presence. Contiddleware climate-related indicators (TCL, LST, HI35) and air pollutant indicators (PM25) exhibit high dropout values, indicating high sensitivity to climate indicators. A rise in temperature increases cooling demand, thereby increasing energy consumption, while environmental indicators serve both as causes and effects of energy consumption (Kotsompolis et al., 2025). The above-discussed points again emphasize the reinforcing cycle of environmental stressors with ENUS. Other greenhouse gases, such as methane (CH4P) and nitrous oxide (N2OP), which are also of high importance, indicate the embeddedness of energy use within other systems of emissions, such as agriculture, waste, and industry (Drago et al., 2025). It shows that ENUS emissions are not confined solely to electricity use and fossil fuel combustion but are embedded across multiple environmental settings. Variables related to the structure of energy system parameters—energy imports (ENIM), energy intensity (ENIN), and fossil fuel dependence (FOSS)—have a non-negligible but secondary effect. That their dropout terms are important shows that these parameters’ structural influences are significant, even if their main effects are through emissions, efficiency, and the environment rather than through direct primary impacts. Variables associated with renewable energy (RELE, RENC) also have a secondary effect, which suggests their impacts on ENUS are indirect, perhaps through system structure and/or efficiency (Kotsompolis et al., 2025). Land-use/natural capital variables—including agricultural land (AGRL), forest cover (FRST), and deforestation-related variables (ASFD)—also help explain ENUS, with relatively small losses due to dropouts. This indicates that energy use links, particularly through bioenergy or agricultural uses, are less straightforward than those associated with greenhouse gases, energy efficiency, and climate change. However, their presence shows that energy use is linked with natural systems (Ferro et al., 2025). Climate variability variables, such as HDD and CDD, and drought variables (SPEI) also exhibit relatively small yet non-zero loss values. Such variables are associated with energy demand, including heating and cooling degree days and drought. Their relatively small values, therefore, indicate that structural variables play a larger role than climate change variability variables in ENUS values (Lee et al., 2025). In conclusion, the analysis of the dropout loss provides a unified view that the major drivers of energy consumption per capita are variables characterizing environmental pressure, emissions, efficiency, and resource use. Within the ESG Environment pillar framework, the ENUS plays a crucial mediating role, connecting climate change, pollution, resource depletion, and efficiency. It is indicated that those aiming at emission reduction and management strategies for waste and emissions, resource efficiency, and climate change adaptation have great potential to influence the ENUS and are critical for assessing environmental sustainability challenges (Kotsompolis et al., 2025; Ferro et al., 2025). See

Table 8.

This table presents counterfactual or attribution results that assess the impact of the ‘E–Environment’ element of the ESG framework on energy use per capita (ENUS). Every scenario shows a change in ENUS against a common baseline, along with the individual contributions of environment variables. These can be considered marginal effects: a negative value indicates a contribution that decreases ENUS relative to the baseline, while a positive value indicates a contribution that increases it. Thus, in this context, this table provides a breakdown of all elements of ENUS, including environmental pressures, climate, emissions, resource use, and energy system parameters. Notably, in each of the nine instances, the projected ENUS is significantly lower than the baseline, highlighting intense downward pressure on energy use arising from the joint setting of the E-Environment variables. An ESG analysis shows that environmental constraints, efficiency effects, and climate conditions strongly shape or limit energy use, rather than merely reacting to it, as further supported by Raza et al. (2025) on the shape of the energy-emission relationship within BRICS systems. Emissions-related variables appear strongly influential across cases. CO₂ emissions per capita (CO2P) show strong negative contributions, with values often exceeding −200,000 across cases, indicating a strongly intertwined relationship between energy consumption and carbon intensity: scenarios with lower or limited emissions imply lower energy use (Bagadeem, 2025). Methane (CH4P) and nitrous oxide (N2OP) show similar negative contributions across all cases, supporting the interpretation that the ENUS system is part of a larger greenhouse gas system rather than a CO₂-only system. The importance of emissions management is apparent throughout the E pillar and strongly indicates that the impact of low-carbon strategies would be directly and significantly realized in terms of lowering the levels of energy consumption, supporting the findings of Zohra (2025) that technological and policy advancements have been influential in lowering CO₂ emissions scenarios for developing areas. Indicators of resource use and pollution provide additional evidence of such an understanding. Waste generation (WSTR) and air pollution (PM25) tend to be negatively associated with predicted ENUS values, suggesting that environmental stress from material fluxes and local pollution is associated with reduced energy use. Water withdrawal (AFWW) is also negatively associated, thereby underlining an equally close energy-water nexus; that is, less-than-adequate or inefficient water use may be an important consideration affecting energy production and consumption. The essential role of efficiency progress and technological advances in mitigating such stress and decoupling energy use from environmental stress is underlined by Lu et al. (2025). The climate variables show more complex patterns. For example, cooling degree days (CDD), heating degree days (HDD), land surface temperature (LST), and heat intensity (HI35) have different signs and values for other cases. For instance, high cooling demand can be a positive driver of ENUS in some scenarios, indicating its influence on energy demand in a warming climate. In other scenarios, high heat and unfavorable climatic conditions, or both, can negatively affect energy demand, potentially due to the inability of infrastructure to support energy-hungry equipment like air conditioners during high heat, a phenomenon observed by Bekele et al. (2024) in Sub-Saharan Africa. Variables such as energy system characteristics and energy efficiency are also significant. The energy efficiency (GEFF) consistently makes a significant negative contribution to ENUS. Thus, an improvement here is among the best ways to reduce energy consumption from an environmental perspective in ESG. The energy intensity (ENIN) and energy imports (ENIM) are also pushing ENUS from below. Thus, systems with lower intensity or limited external sources are associated with lower energy consumption (Mukhiyayeva et al. 2025). The fossil fuel dependence (FOSS) is mainly negative. Thus, once again, this proves that systems with fossil fuel components have high ENUS, and any move away from them significantly affects ENUS values (Raza et al. 2025). Natural capital factors, such as forest area (FRST), agricultural land (AGRL), and renewable energy (RELE, RENC), have yielded mixed but informative results. Some of these factors indicate reduced energy use alongside increases in forest area and renewable energy use, which could be attributed to a move towards less energy-intensive, more sustainable development patterns. Nonetheless, their impact has been more indicative of structural change factors than a decisive driver of ENUS, as supported by Dincã et al. (2025), who argue that they can effectively reduce energy intensity and carbon emissions by increasing renewable energy within the EU. The indicators for climate stress and variability, SPEI, affect estimates of energy consumption differently in each case, sometimes raising and sometimes lowering them. This can be attributed to the contradictory nature of climate stress, in which, on the one hand, droughts can increase energy demand due to adaptation and mitigation activities. At the same time, they can limit energy demand due to reduced economic activity. In general, the decomposition of ENUS indicates that, in the E-Environment dimension of ESG, the factors that most significantly impact ENUS are emissions intensity, efficiency, pollution, and resource constraints, rather than purely climatic conditions or land use patterns (Lu et al., 2025). The findings are consistent with the idea that energy consumption is an essential nexus in, rather than an independent driver of, the integrated environmental system. It can thus be envisioned that decarbonization, efficient use, waste reduction, and pollution mitigation policies will have the most significant leverage in ENUS, thereby further confirming that ENUS serves as an essential nexus through which environmental sustainability goals are achieved in the ESG framework (Mukhiyayeva et al., 2025). See

Table 9.

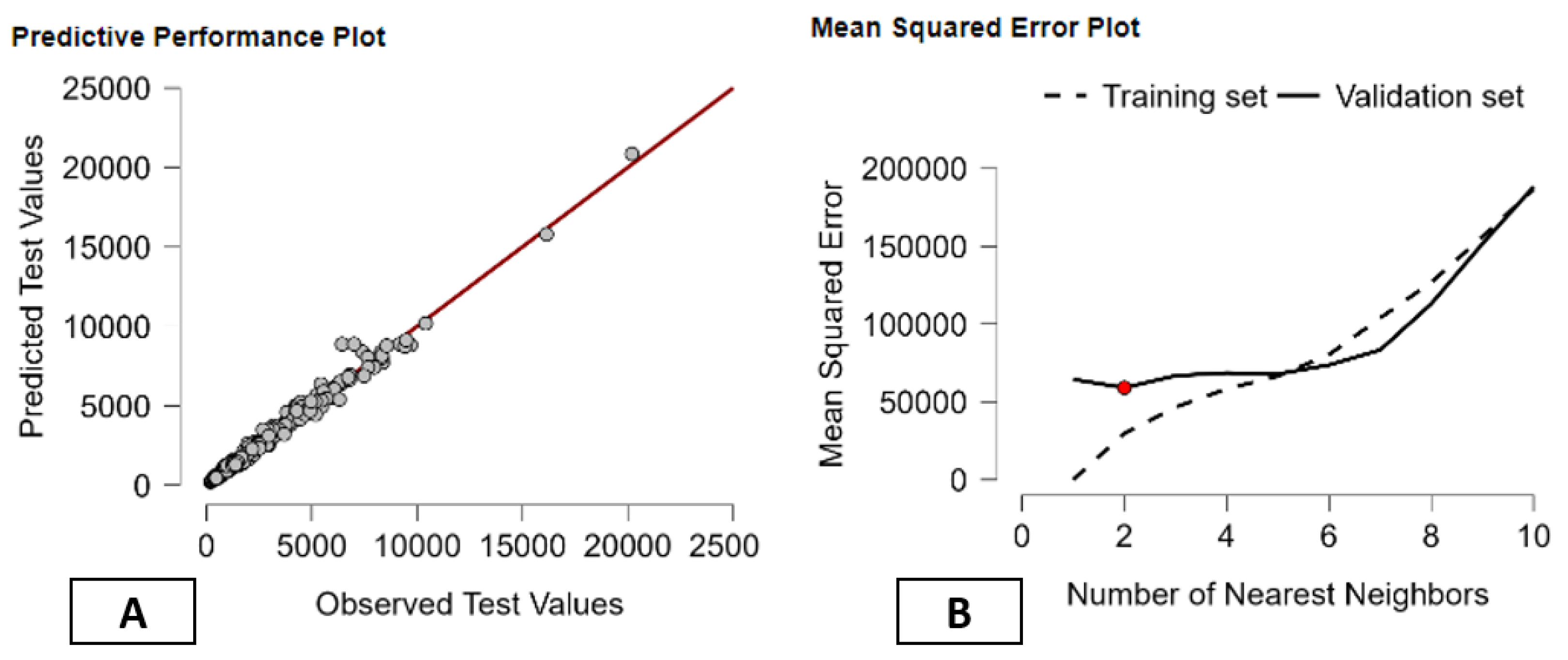

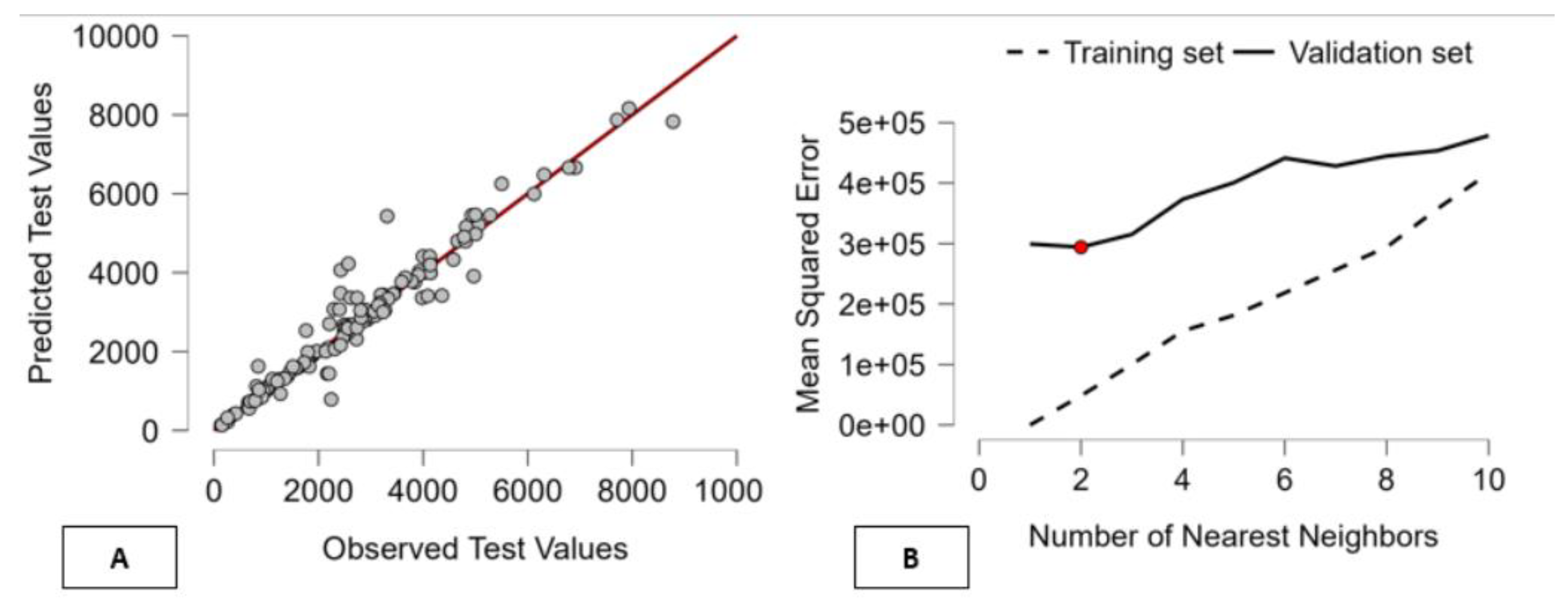

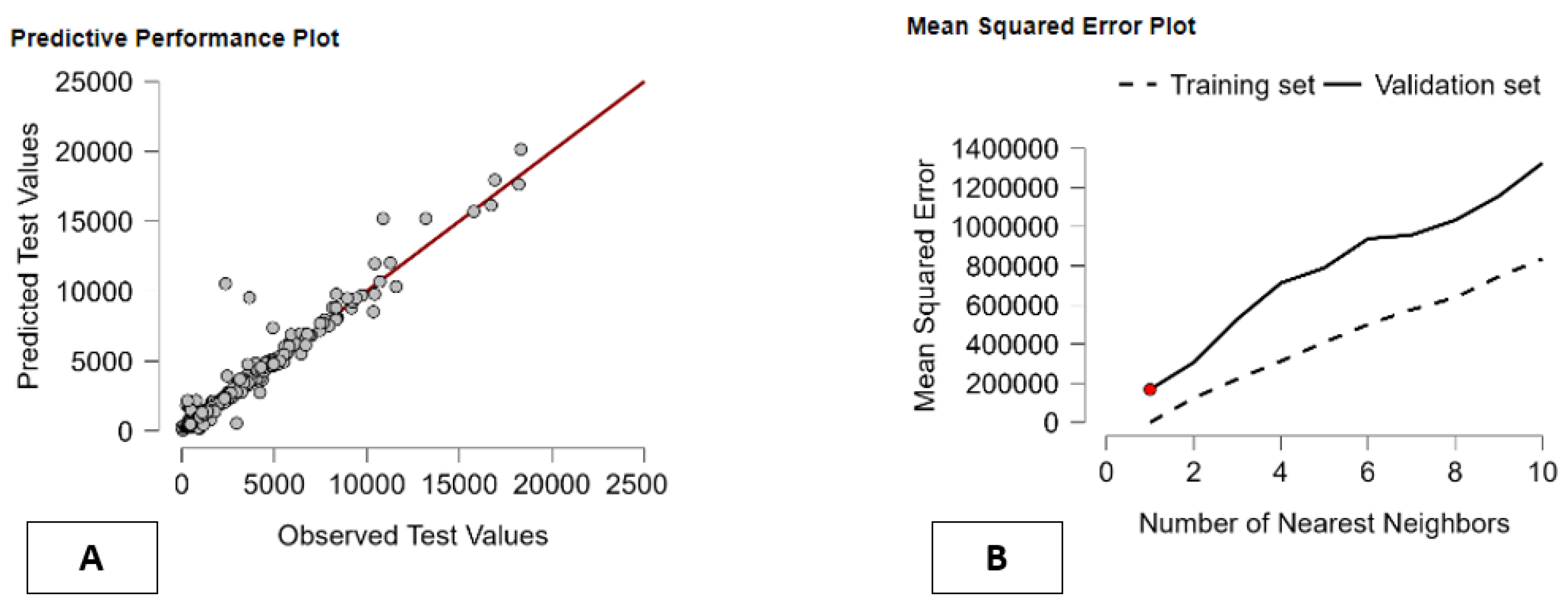

Also, the predictive accuracy of the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm is presented in the diagram using two complementary graphics that assess the accuracy and calibration of the predictive models. KNN has been widely applied in predictive modeling and environmental studies due to its ability to describe non-linear relationships between observed and predicted variables, resulting in high predictive accuracy and model calibration (Mokhtara et al., 2025). The graph shows the predictive performance, with the expected test data plotted against the observed test data. Nearly all the observed data points are closely clustered around the diagonal, indicating strong consistency between the predicted and observed data. However, the observed deviation from the diagonal is slight throughout, indicating minimal systematic error and an optimal fit provided by the data's mode (Nie et al., 2025). From this information, it can be concluded that the KNN algorithm accurately replicates the non-linear structure of the data. In the other graph, the mean-squared error is plotted against the number of neighbors, with calculations performed on the training and validation data. As anticipated, the mean-squared error on the training data decreases continuously as k is lowered, reflecting the models' increased flexibility. Still, the mean-squared error on the validation data exhibits a “U” shape. Additionally, the minimum mean-squared error on the validation data is small for small k, indicating the optimal combination provided by the KNN models. A small value of k tends to increase the probability of overfitting (

Figure 3).

5. Social Determinants of Energy Consumption: An ESG–S Analysis Using Econometric and ML Approaches

5.1. Social Sustainability and Energy Consumption: Structural Evidence from Panel Regressions

This article investigates the relationship between the Social (S) dimension of the ESG framework and energy use per capita (ENUS), conceptualizing energy consumption as a socio-economic outcome rather than a purely environmental variable. By focusing on indicators related to health, demographics, food security, and social well-being, the analysis explores how social development patterns shape national energy demand. Using a large cross-country panel dataset and a fixed-effects econometric framework, the study aims to uncover the structural social drivers of energy use and to highlight the trade-offs and complementarities between social progress and sustainable energy consumption.

The following equation has been estimated: