Submitted:

28 December 2025

Posted:

29 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The environment (E) (for example, carbon emissions, use of natural resources, waste to landfill data),

- Society (S) (for example, standards for human rights, gender pay gaps, diversity representation and employee turnover).

- Taking responsibility for the efficient and effective management of opportunities and risks, or its governance (G) (for example, composition of the board, executive pay and bonuses, regulatory compliance).

The Emergence and Growing Importance of ESG

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.2. Thematic Focus

3. Results

3.1. The Growing Significance of ESG

3.1.1. The Core Components of ESG

3.1.2. The Interconnectedness of ESG Components and Its Indispensability for ESG Management

3.2. ESG and Business Practice - Integration of ESG into Business Practice: The Key Principles

3.3. The Importance of ESG for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

3.3.1. Supply Chain Integration and Competitive Advantage

3.3.2. Resilience and Risk Mitigation

3.3.3. Access to Finance and Investment

3.3.4. Regulatory Compliance and Futureproofing

3.3.5. Social Responsibility and Community Impact

3.4. From Theory to Practice the Current State of Play for SMEs and ESG Integration

|

Introduction

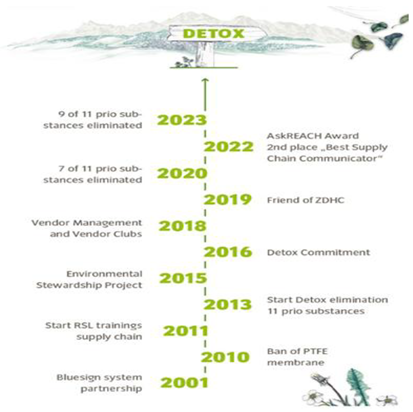

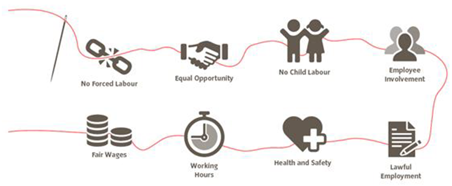

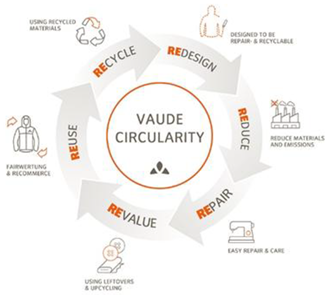

VAUDE, a German outdoor clothing company owned by a family, is a prime example of how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can successfully incorporate ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) principles into their operations. Since its founding in 1974, VAUDE has become internationally recognised not just for its high-quality, technologically advanced products, but also for its strong dedication to sustainability and social responsibility. The company’s approach to ESG provides a useful case study, showing how SMEs can use ESG practices creatively to boost their competitiveness, lower risks, and make a positive impact on both society and the environment. What constitutes Vaude’s approach to ESG adoption and implementation. Environmental Stewardship (‘E’ in ESG) VAUDE places environmental sustainability at the core of its business strategy. The company has made significant efforts to minimize its environmental impact throughout its operations. In 2023 and 2024, VAUDE increased its commitment to achieving climate neutrality by advancing science-based targets. It actively worked to lower its carbon emissions by improving energy efficiency and increasing the use of renewable energy at its production sites, such as installing more solar panels and adopting advanced energy management systems. These initiatives played a major role in helping VAUDE reach climate neutrality, as confirmed by the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) in line with the 1.5 °C target [60]. Innovation and Circular Economy Recently, VAUDE has prioritised the circular economy, aiming for 90% of its products to be made from recycled or renewable materials by 2024. This goal is supported by advances in product design, such as using 3D printing to manufacture robust and recyclable outdoor gear, which helps minimize waste and encourages the reuse of materials. In 2023, VAUDE was honored with the International Design Award “Focus Meta” for the innovative and forward-thinking design of its “Novum 3D” backpack [61]. The company also adopted the Green Button certification, which verifies that its products meet strict environmental criteria, further demonstrating its dedication to sustainable product lifecycle management [62]. Transparency and Robust Management Beyond improving energy efficiency, VAUDE has established a comprehensive environmental management system that oversees every stage of its products’ lifecycle. The company emphasizes responsible sourcing, Utilising materials like organic cotton, recycled polyester, and other environmentally friendly textiles. VAUDE also extends its high environmental standards to its supply chain, working closely with suppliers to ensure they follow similar sustainability practices. This integrated approach has earned VAUDE several certifications, including the European Union’s Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) and the bluesign® system, which is Recognised as the world’s strictest textile standard for environmental and consumer protection [63] .  Figure 1 : VAUDE Roadmap to Detox; VAUDE has been working with bluesign® since 2001. (Source: csr-report.vaude.com) The ‘S’ in Vaude’s ESG: Social Responsibility VAUDE complements its ‘E’ strategy with an equally comprehensive sense of dedication to social responsibility initiatives, including ethical business practices and community engagement. The company’s social policies are built around the principles of fair labour, diversity, and inclusion. VAUDE ensures that all its employees work in safe and healthy conditions, with fair wages and access to benefits such as health insurance and pension plans. Additionally, the firm is committed to gender equality within its workforce, with women holding a significant proportion at 47% of management positions [64].  Figure 2 : VAUDE’s Social Principles (Source: csr-report.vaude.com) The Socially Responsible Community VAUDE goes beyond its own operations to promote social responsibility by actively involving its suppliers and the wider community. The company works with the Fair Wear Foundation, an independent group focused on improving labor conditions in the textile sector. Through this collaboration, VAUDE ensures its suppliers adhere to strict standards, such as banning child labor, forced labor, and discrimination, and maintaining safe working environments [65]. In 2024, VAUDE strengthened its fair wage policies and expanded employee benefits, furthering diversity and inclusion within its workforce. The company also created the VAUDE Academy, which provides sustainability training for employees and stakeholders, encouraging ongoing learning and engagement [66]. VAUDE supports local communities by initiating and backing projects that improve education and healthcare in disadvantaged areas. For example, in 2023, the company launched the “Rethink! Circular Product Design” initiative, which not only advances sustainable product innovation but also helps drive community-based sustainability efforts. These activities reinforce VAUDE’s reputation as a socially responsible business and help build trust and loyalty among its stakeholders [67].  Figure 3 : VAUDE’s Circular business model (Source: csr-report.vaude.com) Governance and Ethical Leadership: The ‘G’ in Vaude’s ESG Governance forms the foundation of VAUDE’s ESG approach, ensuring that environmental and social initiatives are seamlessly integrated into the company’s overall operations. The governance system at VAUDE is marked by openness, accountability, and principled leadership. The board of directors includes independent members who oversee operations and make sure decisions benefit all stakeholders - employees, customers, suppliers, and the community. Additionally, VAUDE has implemented a code of ethics that shapes its business conduct, focusing on honesty, fairness, and responsibility. This is further supported by anti-corruption measures and clear procedures for reporting and addressing unethical actions. The governance framework has been strengthened by adding more independent board members and updating the code of ethics to include stricter anti-corruption rules and improved reporting mechanisms for misconduct [68]. Being transparent VAUDE’s dedication to ethical governance is also evident in its transparent reporting. The company’s sustainability reports are now more detailed and open, offering comprehensive information about ESG achievements and progress. By adopting standardised reporting systems like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Higg Index, VAUDE ensures its ESG disclosures are consistent and trustworthy. This level of transparency not only strengthens stakeholder trust but also supports better decision-making and strategic planning within the organisation [69]. Reaping Acclaim and Rewards The company’s strong commitment to ESG has improved its efficiency and competitiveness, earning it significant recognition. VAUDE has received several awards for its sustainability work, including the German Sustainability Award, which honors companies making outstanding contributions to sustainable development. In 2024, VAUDE was Recognised as Germany’s most sustainable textile company in two categories, highlighting its excellent governance and sustainable business strategies. This proactive ESG approach has attracted environmentally and socially conscious customers and investors, helping the company grow its presence in Europe and North America [61]. Moreover, VAUDE’s advocacy for environmental protection, such as promoting restrictions on PFAS chemicals, demonstrates its leadership in advancing broader regulatory and environmental standards. Participation in initiatives like the German Partnership for Sustainable Textiles and the Science Based Targets Initiative further boosts the company’s credibility and independence, establishing it as a trusted name in sustainability [69]. By focusing on sustainability, ethical leadership, and social responsibility, VAUDE serves as a model for other SMEs aiming to strengthen their long-term success and contribute to global sustainability objectives. General Observations Through its commitment to environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and strong governance, VAUDE has improved its own business operations while generating a positive impact on its stakeholders and the wider environment. They can also be looked at as conscious attempts to re-design the organisation through innovative practices leading a transformation of its organisational capacity to accommodate ESG while embracing and implementing the key concept of ‘value circularity’. This case study highlights the potential for SMEs to lead in ESG practices, demonstrating that sustainability and ethical business practices can be powerful drivers of resilience, innovation, and long-term success. Following Vaude’s example SMEs can start by identifying material ESG issues, engage stakeholders, optimise resource allocation, ensure transparency, get involved in supply chains, leverage existing and new technologies for ESG-led innovation, and act as gatekeepers of regulations and standards. The case study also highlights how ESG can be a spur for innovation subject to the business adopting a clear strategy to map ESG across all its activities. It is also the case that ESG’s adoption and successful implementation is strongly dependent on two key resources, more than others – technological and human. An adequate (defined according to specific micro contexts and type of business) technology platform which accommodates regular iteration and revamping coupled with skills and capabilities (managerial, technical, networking) could pave the way for competitive positioning of firms. Details are discussed later in the paper. By systematically addressing these factors, SMEs can embed ESG into their core strategy, enhance their competitiveness, and contribute positively to society and the environment. |

3.5. Global and Regional Forms of ESG Adoption

3.5.1. Regulatory Frameworks and Reporting Requirements

3.5.2. Financial Incentives and Access to Capital

3.5.3. Capacity Building and Education

3.5.4. Public-Private Partnerships and Collaboration

4. Discussion

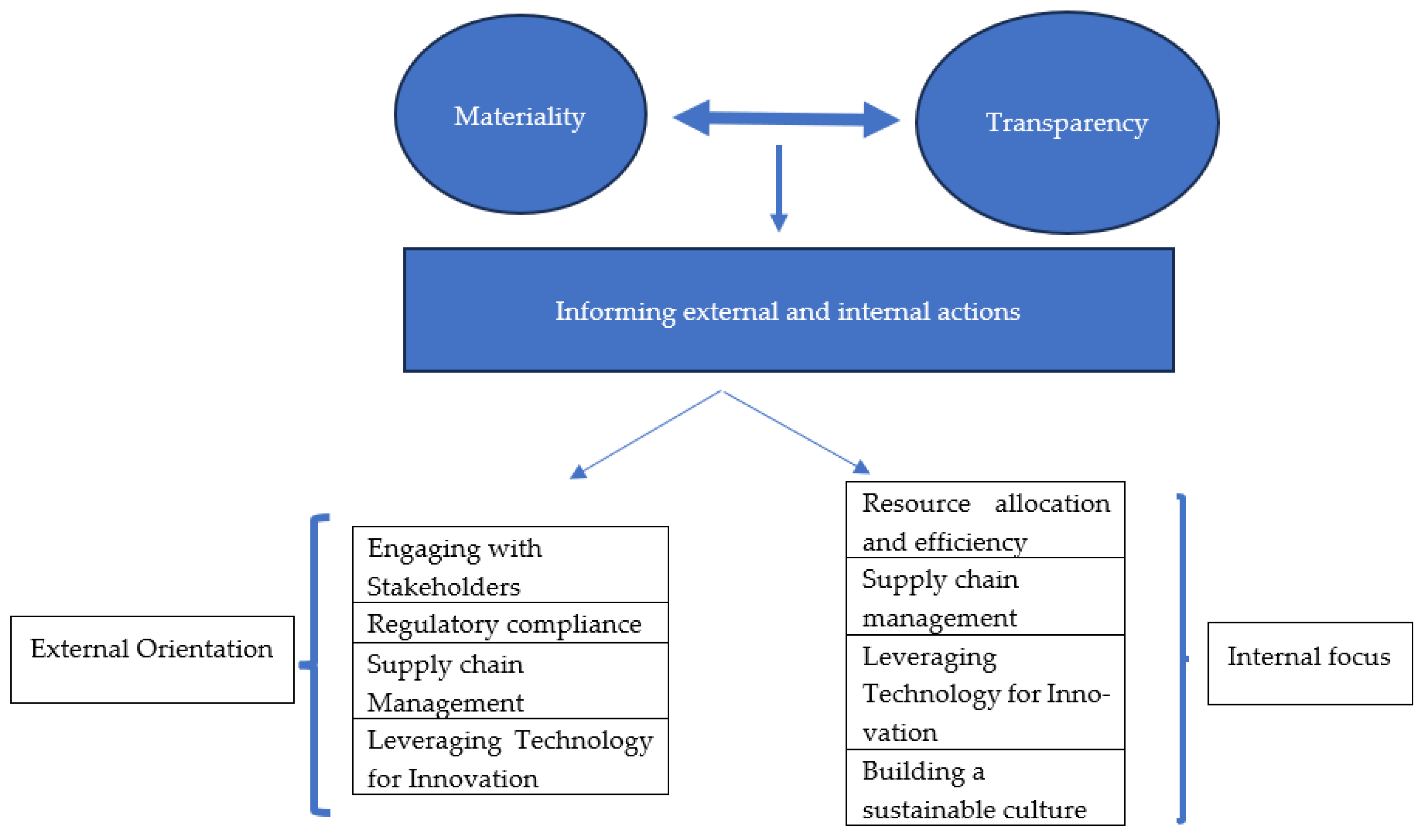

4.1. Towards the Development of a Framework for Adopting ESG

4.2. Key Metrics for SMEs in Recording and Reporting ESG Issues

4.2.1. Environmental Metrics

- (a)

- Carbon Footprint (CO2 Emissions): This measures the total greenhouse gases (GHGs) the company emits, both directly and indirectly, typically reported in metric tons of CO2 equivalent. SMEs should account for scope 1 (direct), scope 2 (indirect from purchased energy), and, where possible, scope 3 (indirect across the value chain) emissions [87].

- (b)

- Energy Consumption: This tracks the company’s total energy use, usually in megawatt-hours (MWh) or gigajoules (GJ). Reporting the share of energy from renewable sources as a percentage of total consumption is also recommended [88].

- (c)

- Water Usage: This records the total water consumed, generally in cubic meters. For water-intensive sectors like agriculture or manufacturing, water intensity (usage per unit of output) is also a useful measure [82].

- (d)

- Waste Management: This tracks the total waste produced, the proportion recycled, and hazardous waste generated. Reporting waste diversion rates (percentage of waste kept out of landfills via recycling or composting) is also valuable [89].

- (e)

- Resource Efficiency: These metrics assess how efficiently the company uses resources such as raw materials, energy, and water. For example, resource intensity might be measured as the amount of raw material used per unit of product [90].

4.2.2. Social Metrics

- (a)

- Employee Health and Safety: This includes indicators like the number of workplace accidents, lost-time injury frequency rate (LTIFR), and hours of health and safety training per employee [91].

- (b)

- Diversity and Inclusion: Metrics here may include the percentage of women in the workforce and management, as well as workforce diversity by ethnicity, age, and other factors. They can also track diversity program implementation and employee satisfaction with inclusion efforts [86].

- (c)

- Employee Turnover Rate: This measures the percentage of employees leaving the company over a set period. High turnover may signal issues with job satisfaction, working conditions, or company culture [92].

- (d)

- Training and Development: This tracks the average training hours per employee, including professional and skills development, reflecting the company’s investment in staff growth [41].

- (e)

- Community Engagement: These metrics capture the company’s involvement in local communities, such as employee volunteer hours, charitable donations, and community investment as a share of revenue [82].

4.2.3. Governance Metrics

- (a)

- Board (including company and advisory) Composition: This tracks the diversity and independence of the board, including the percentage of independent directors, gender diversity, and the presence of ESG-focused board committees [93].

- (b)

- Executive Compensation: This reports on executive pay structures, such as the CEO-to-median employee pay ratio and the extent to which executive compensation is tied to ESG outcomes [94].

- (c)

- Ethical Conduct and Compliance: Metrics here include the number of reported ethical breaches, resolved complaints, and the existence of codes of ethics and anti-corruption policies. The effectiveness of whistleblower protections and compliance training are also key indicators [95].

- (d)

- Transparency and Reporting: This assesses the company’s openness in ESG communications, including the frequency and thoroughness of reporting and stakeholder engagement in governance (e.g., shareholder voting and feedback mechanisms) [82].

- (e)

- Data Security and Privacy: With digital operations becoming more important, metrics on data protection are essential. These include the number of data breaches, the percentage of employees trained in data protection, and compliance with privacy regulations like GDPR [96].

4.3. Barriers to the Application of ESG in SMEs and Strategies for Overcoming Them

4.3.1. Limited Financial Resources

- (a)

- Seek green financing through government grants, low-interest loans, and tax incentives, which are increasingly available to support sustainable business practices. For instance, the EU’s Green Deal Investment Plan offers funding for SMEs pursuing green technologies [75]. Impact investors and green finance programs also target SMEs with strong ESG commitments, helping them access capital for ESG projects. Building relationships with such investors can ease the financial burden of ESG adoption [76].

- (b)

- Collaborate with other businesses or join public-private partnerships to share ESG project costs and benefit from pooled resources and expertise [30].

- (c)

- Implement ESG in phases, starting with affordable, high-impact actions like energy efficiency or waste reduction, and expanding as resources grow [97].

4.3.2. Lack of Knowledge and Expertise

- Participating in training programs and workshops tailored to SME needs, offered by governments, industry groups, or NGOs [41].

- Engaging advisory services, such as consultants or academic partners, for customized guidance. Public-private partnerships can also help build SME capacity by sharing best practices and providing access to ESG tools [98].

- Utilising online resources and toolkits from organisations like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the United Nations Global Compact for practical ESG guidance [99].

4.3.3. Regulatory Uncertainty

4.3.4. Perceived Lack of Relevance

4.3.5. Short-Term Focus and Pressure

4.3.6. Supply Chain Challenges

4.3.7. Measurement and Reporting Challenges

4.3.8. Forms of Resistance - Cultural, Organisational and Social

5. What next for ESG and SMEs?

5.1. Heightened Regulatory Scrutiny and Standardisation

5.2. The Increasing Integration of Core Business Strategy with ESG

5.3. The Growth ESG-Linked Forms of Finance

5.4. Technological Developments and ESG Data Analytics

5.5. Consumer and Investor Activism

5.6. Challenges and Risks

5.7. Opportunities for SMEs

5.8. Ecosystems of ESG Opportunity

Acknowledgments

References

- McKeever, E.; Anderson, A.; Jack, S. Entrepreneurship and mutuality: social capital in processes and practices. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2014, 26, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, J.; Bui, H.T. ESG and SMEs: The State of Play. International Network for SMEs (INSME) Briefing Paper. 2024. Available online: https://www.insme.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/ESG-and-SMEs-The-State-of-Play.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Johnstone-Louis, M. 20 Debates, Metrics, and the Competitive Advantage of ESG24). ESG: The Insights You Need. Harvard Business Review (HBR Insights Series) 13-8-2024.

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. Available online. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, J.; Sokolowicz, M.; Weisenfeld, U.; Kurczewska, A.; Tegtmeier, S. Citizen Entrepreneurship: A Conceptual Picture of the Inclusion, Integration and Engagement of Citizens in the Entrepreneurial Process. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 6, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, A. Climate Capitalism: Winning the Global Race to Zero Emissions.; John Murray Press: London, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara, N.; Fitrisari, D.; Irie, N. Debatable Nature of Environmental, Social and Governance Information: Focusing on Mandatory Disclosures. Kindai Management Review 2024, Vol. 12., pgs. 90–10. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. Sustainable development: Our Common Future revisited. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Global Compact. Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World . 2004. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/events/2004/stocks/who_cares_wins_global_compact_2004.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) Principles for Responsible Investment. 2006. Available online: https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=10948 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- United Nations. Paris Agreement . 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Lawton, G. A timeline and history of ESG investing, rules and practices. Tech Accelerator ESG strategy and management: A guide for businesses. 2024, 12. Available online: https://www.techtarget.com/sustainability/feature/A-timeline-and-history-of-ESG-investing-rules-and-practices (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Skadden. ESG in 2025: A Midyear Review. 2025. Available online: https://www.skadden.com/-/media/files/publications/2025/06/esg_in_2025_a_midyear_review.pdf?rev=084d748c30ef41b19364c7182fa950c6 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Bulbulia, J.; Wildman, W.J.; Schjoedt, U.; Sosis, R. In praise of descriptive research. Religion, Brain & Behavior 2019, 9(3), 219–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lans, W.; Van der Voordt, D.J.M. Descriptive research. In Ways to study and research urban, architectural and technical design; DUP Science, 2002; pp. 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D.; Adams, A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 2006, 5, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani-Khaled, S.; Azevedo, G.; Oliveira, J. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors and firm value: A systematic literature review of theories and empirical evidence. AMS Rev. 2025, 15, 228–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Solina, V.; Verteramo, S. The Impact of ESG Practices in Industry with a Focus on Carbon Emissions: Insights and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. The use of ESG scores in academic literature: a systematic literature review. J. Enterprising Communities: People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, Efuntade; Efuntade, Alani; Solanke, Festus; Olugbamiye, Dominic Olorunleke. Theoretical And Conceptual Review: An Essential Part of Social and Management Sciences Research Process. International Journal of Social Science and Religion (IJSSR) Available online. 2024, 10(5), 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Li, Y.; Agarwal, R.; Barney, J.B.; Dushnitsky, G.; Graebner, M.E.; Klein, P.G.; Sarasvathy, S. Developing theoretical insights in entrepreneurship research. Strat. Entrep. J. 2023, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. R.; Starnawska, M. Research practices in entrepreneurship: Problems of definition, description and meaning. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 2008, 9(4), 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, P. ESG and Responsible Institutional Investing Around the World: A Critical Review. CFA Institute Research Foundation. 2020. Available online: https://www.cfainstitute.org/sites/default/files/-/media/documents/book/rf-lit-review/2020/rflr-esg-and-responsible-institutional-investing.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- WHO. Together for a Healthier World: Programme Budget 2024-25. Mid-Term Results Report. Geneva. World Health Organisation. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/accountability/results/who-results-report-2024-2025.

- Nielsen. Unpacking the Sustainability Landscape . 2018. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/en-au/document/university-of-queensland/consumer-behaviour/nielsen-2-unpacking-the-sustainability-landscape-nielsen/28344493 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Andre, P.; Boneva, T.; Chopra, F.; Falk, A. Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2024, 14, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoon, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. Available online. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Jackson, G. The Cross-National Diversity of Corporate Governance: Dimensions and Determinants. Acad. Manag. Rev. Available online. 2003, 28, 447–465. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) . 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/non-financial-reporting_en (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- KPMG. Sustainable supply chain . 2023. Available online: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/what-we-do/ESG/sustainable-supply-chain.html#01 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- CFA Institute. Guidance for Integrating ESG Information into Equity Analysis and Research Reports . 2023. Available online: https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/en/research/reports/2023/guidance-for-integrating-esg-information-into-equity-analysis-and-research-reports (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures . 2017. Available online: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/publications/final-implementing-tcfd-recommendations/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. Available online. 2015, 5, 210–233. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance. University of Oxford and Arabesque Partners. 2015. Available online: https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2021). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020. Available online: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/trends-report-2020/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Deloitte. The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2020 . 2020. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/deloitte-2020-millennial-survey.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Strategic Innovation Management; John Wiley & Sons: Bognor Regis, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. 2024 Environmental Sustainability Report . 2024. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/corporate-responsibility/sustainability/report (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Unilever. Unilever Sustainable Living Plan 2010 to 2020 . 2020. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/files/92ui5egz/production/16cb778e4d31b81509dc5937001559f1f5c863ab.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- OECD. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021 . 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/97a5bbfe-en.pdf?expires=1727542989&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=FA1E82E7BA9882B7857E0589B99B4BF4 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- World Bank. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance . 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- OECD. “No net zero without SMEs: Exploring the key issues for greening SMEs and green entrepreneurship”. In OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers No. 30; accessed on; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Publishing: Paris, 2021; (accessed on 4 July 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, J. Nexus between green finance, energy efficiency, and carbon emission: covid-19 implications from Brics countries. Frontiers in Energy Research accessed on. 2021, 9, 786659. (accessed on 4 July 2025). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Hu, H.; Chang, C. Green finance, environment regulation, and industrial green transformation for corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. Available online. 2023, 30, pp. 2166–2181. (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Financing the sustainable development goals through mission-oriented development banks. In UN DESA Policy Brief Special Issue; UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York; UN High-Level Advisory Board on Economic and Social Affairs; University College London Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Udeagha, M.C.; Muchapondwa, E. Striving for the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs) in BRICS economies: The role of green finance, fintech, and natural resource rent. Sustain. Dev. Available at. 2023, 31, 3657–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeagha, M.C.; Muchapondwa, E. Green finance, fintech, and environmental sustainability: fresh policy insights from the BRICS nations. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 30, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.I.; Chiloane-Tsoka, E.G.; Mugambe, P. Unlocking the potential: the influence of sustainable finance solutions on the long-term sustainability of small and medium-sized enterprises. Cogent Bus. Manag. Available online. 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Unilever. Unilever Sustainable Living Plan 2010 to 2020 . 2020. Available online: https://www.unilever.com/files/92ui5egz/production/16cb778e4d31b81509dc5937001559f1f5c863ab.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Walmart. Environmental Social and Governance Summary Report FY2022 . 2022. Available online: https://corporate.walmart.com/content/dam/corporate/documents/purpose/environmental-social-and-governance-report-archive/walmart-fy2022-esg-summary.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- McKinsey; Company. The ESG Premium: New Perspectives on Value and Performance . 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/the-esg-premium-new-perspectives-on-value-and-performance (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) 2023 GIINsight Series. 2023. Available online: https://thegiin.org/research/publication/2023-giinsight-series/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- ING. Sustainability-Linked Loan . n.d. Available online: https://www.ingwb.com/en/sustainable-finance/sustainability-linked-loans (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- European Commission. Corporate Sustainability Reporting . 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Spence, L.J. Small Business Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. Available online. 2016, 55, 23–55. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Sustainable Finance for SMEs in Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs; OECD: Paris, 2024; Volume Ch. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Corporation, B. Divine Chocolate Ltd . n.d. Available online: https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/find-a-b-corp/company/divine-chocolate-ltd/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- TNG Investment and Trading JSC. Annual Report 2021 . 2021. Available online: https://tng.vn/userfiles/files/Quan%20H%E1%BA%B9%20c%E1%BB%95%20%C4%91%C3%B4ng/BAO%20Cao%20Thuong%20Nien%202021/20220429_TNG_AR2021_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- VAUDE. 2023) Science-Based Targets: VAUDE’s Commitment to Climate Action, VAUDE Blog. Available online: https://www.vaude.com/de/en/blog/post/science-based-targets.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Awards (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/vaude/our-awards.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Green Button (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/csr-standards/green-button.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Systematically better: bluesign® system (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/product/bluesign-certified-materials.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Diversity in the workplace (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/social/diversity-and-nondiscrimination.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Fair Wear Foundation (2024) Labour Standards. Available online: https://www.fairwear.org/about-us/labour-standards (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – The VAUDE Academy for sustainable management (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/vaude/vaude-academy.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Our path towards the circular economy (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/vaude/circular-economy.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – Codes of Conduct (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/vaude/codes-of-conduct.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- VAUDE 2023 Sustainability Report – CSR Standards (2024). Available online: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/archiv/2023/gri-en/csr-standards/Standards-and-certificates.html?navid=821464821464 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Nordic Council of Ministers. State of the Nordic Region 2020 . 2020. Available online: https://pub.norden.org/nord2020-001/nord2020-001.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). SEC Announces Enforcement Task Force Focused on Climate and ESG Issues . 2021. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2021-42 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Japan Exchange Group (JPX). Publication of Revised Japan’s Corporate Governance Code . 2021. Available online: https://www.jpx.co.jp/english/news/1020/20210611-01.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Climate Bonds Initiative. China Green Finance Policy Analysis Report 2021 . 2021. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/policy_analysis_report_2021_en_final.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Government of Vietnam. National Green Growth Strategy for 2021-2030 Vision Towards 2050 . 2021. Available online: https://en.baochinhphu.vn/national-green-growth-strategy-for-2021-2030-vision-towards-2050-11142515.htm (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS). European Green Deal Investment Plan . 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/649371/EPRS_BRI(2020)649371_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Monetary Authority of Singapore. Sustainable Loan Grant Scheme . 2021. Available online: https://www.mas.gov.sg/schemes-and-initiatives/sustainable-loan-grant-scheme (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- UK Government. Clean Growth Equity Fund . 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/clean-growth-equity-fund (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. SME Policy - The German Mittelstand as a model for success. 2021. Available online: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Dossier/sme-policy.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Life, Canada. Canadian Chamber of Commerce and Government of Canada team up to launch Canadian Business Resilience Network to help businesses get through COVID-19 . 2020. Available online: https://www.canadalife.com/about-us/news-highlights/community/canadian-business-resilience-network.html (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Dutch Sustainable Growth Coalition (DSGC). About the DSGC . n.d. Available online: https://www.dsgc.nl/en (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- United Nations China. UN Agencies Collaborate with Chinese Enterprises to Enhance Capacity in Sustainable Procurement . 2023. Available online: https://china.un.org/en/254444-un-agencies-collaborate-chinese-enterprises-enhance-capacity-sustainable-procurement (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). GRI Universal Standards 2021 . 2022. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/media/zauil2g3/public-faqs-universal-standards.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Managing for Stakeholders: Survival, Reputation, and Success; Yale University Press: New Haven, 2007; Available online: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10013954 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- von Berlepsch, D.; Lemke, F.; Gorton, M. The Importance of Corporate Reputation for Sustainable Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review, Bibliometric Mapping, and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethic- Available online. 2024, 189, 9–34. (accessed on 3 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership., 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. Unlocking Technology for the Global Goals . 2020. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/Unlocking_Technology_for_the_Global_Goals.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- CDP. Guidance for Companies . 2021. Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en/guidance/guidance-for-companies (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency 2021 . 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2021 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. It’s time for a circular economy . n.d. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- European Environment Agency. Economy and resources . 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- International Labour Organization. Safety and health at work . n.d. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/topics/safety-and-health-work (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). 2022-2023 State of the Workplace Report . 2023. Available online: https://www.shrm.org/content/dam/en/shrm/research/2022-2023-State-of-the-Workplace-Report.pdf.

- Corporate Governance Institute. The board’s role in ESG . n.d. Available online: https://www.thecorporategovernanceinstitute.com/insights/lexicon/boards-role-in-esg/?srsltid=AfmBOoq-H2GS5A1XofEC2T74diL7YHB4WndnbG6n_38C8TCFxByyLBE3 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Linking executive compensation to ESG performance . 2022. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/11/27/linking-executive-compensation-to-esg-performance/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Transparency International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2023 . 2023. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- International Association of Privacy Professionals. Measuring privacy programs: The role of metrics . 2022. Available online: https://iapp.org/news/a/measuring-privacy-programs-the-role-of-metrics/ (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- International Finance Corporation. How investing in SMEs creates jobs . 2021. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/content/dam/ifc/doc/mgrt/ifc-sme-report-2021-fa-digital.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- ESCAP Sustainable Business Network. Socially Responsible Business: A Model for a Sustainable Future. Studies in Trade, Investment and Innovation 88. Bangkok. United Nations Trade, Investment and Innovation Division ESCAP. 2017. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/publications/Final_Socially%2520Responsible%2520Business_STII88.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- UN Global Compact (2017) United Nations Global Compact Global Strategy: Taking the UN Global Compact to the Next Level. New York: United Nations. March. Available online: https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/about_the_gc%2FUNGC-2020-Global-Strategy.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 14000 family . n.d. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standards/popular/iso-14000-family (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- World Economic Forum. SMEs should link growth with environmental sustainability. 2024. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/net-zero-environmental-sustainability-smes-benefits/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- ESCAP Sustainable Business Network. ESCAP Sustainable Business Network – Monthly Update August 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/newsletter/ESBN%2520Monthly%2520Update-Aug%25202020_final.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Villena, V.; Gioia, D. A More Sustainable Supply Chain. Harvard Business Review. 2020. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/03/a-more-sustainable-supply-chain (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- UNDP. UNDP Annual Report 2020. United Nations Development Programme. 23 May 2021. Available online: https://www.undp.org/tag/annual-report-0?type=publications (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Spierings, M. Linking Executive Compensation to ESG Performance, The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. 2022. Available online: https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2022/11/27/linking-executive-compensation-to-esg-performance/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

| Year | Development and Adoption | Year | Development and Adoption |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Two United Methodist ministers in the USA opposed to the Vietnam War, set up the Pax World Fund. This was a public mutual fund available in the U.S.A. Their promotion of environmental and social criteria was integrated with investment decisions for the first time in the country. At around the same time, pension funds began focusing on investments in areas geared to improved healthcare and affordable housing, by encouraging worker-investors. | 2006 | The launch of the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) marked a significant moment for ESG. The objective was to enable investors to factor-in ESG issues in their investment assessments [10]. |

| 1990 | Three partners, Amy Domini, Peter Kinder and Steve Lydenberg, the managers of KLD Research and Analytics, established the Domini 400 Social Index, which concentrated on firms prioritizing social and environmental responsibility. The Domini Social Impact Equity Fund was launched in 1991 to experiment with these environmental and social issues, with the fund attracting $1.3 billion by 2001. | 2015 | Both the Paris Agreement and SDGs pushed the significance of ESG as a global priority, allowing companies and investors to regard their use-value on major challenges such as climate change, poverty, inclusiveness and inequality [11]. |

| 1992 | The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change was created when a group of 154 countries signed a treaty to mitigate “dangerous human interference with the climate system” at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. The treaty promoted research and identified the importance of ongoing meetings, laying the foundations for policy agreements over time. This act also witnessed the start of an annual meeting of delegates referred to as the Conference of the Parties (COP). | 2017 | The Compact for Responsive and Responsible Leadership was signed by more than 140 CEOs at the World Economic Forum (WEF) meeting in Davos, Switzer-land. |

| 1995 | The Social Investment Forum Foundation (known as the U.S. SIF Foundation) based in Washington DC, organised the first inventory of the both the quantum and value of sustainable investments. This stick-taking revealed a total of $639 billion in assets managed in the U.S. In another 15 years, by 2020, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance had estimated investments of $35.3 trillion in sustainable assets worldwide. | 2019 | The Davos Manifesto 2020 was published by the WEF as a set of ethical principles to support firms through the technological disruptions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The manifesto outlined the need to serve employees, customers, suppliers and other stakeholders, as well as local communities and society as a whole |

| 1997 | The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997 and eventually came into force in 2005. A total of 192 countries ratified an agreement to set specific reduction targets for greenhouse gases. The 36 countries which signed the first commitment period, all met their obligations, although 9 of them relied on funding climate reduction initiatives in other countries to set-off their excesses. Absent from the meeting were the two largest emitters, China and the U.S. The year also witnessed the launch of The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) with a view to addressing disclosures by firms related specifically to environmental concerns. The group’s mandate was later stretched to cover reporting on social and governance issues. | 2020 | The WEF and Big Four accounting firms published their white paper standardising a set of metrics for businesses reporting on their progress with ESG. |

| 2000 | The end of the 20th century saw the establishment of the U.N.’s Global Compact which established a set of 10 principles for organisations to adopt across diverse areas, including human rights, labour practices, the environment and anti-corruption efforts. In the same year, the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) was formed to organize and empower larger investors to ask companies to report on their performance on climate change and risk mitigation issues. | 2021 | The European Union’s (EU’s) Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) set clear requirements for how funds with sustainable investment objectives could be used as against those that were regarded as non-sustainable (both requirements being accounted for in the regulation. |

| 2004 | This year saw the popularisation of ESG by a report titled “Who Cares Wins,” an initiative of the UN Global Compact (UNGC). The report, stated clearly that incorporating ESG factors into capital markets makes good business sense because it helps to establish more sustainable markets and better outcomes for societies [9]. | 2024 | The EU Directive 2024/1760 on corporate sustainability due diligence (CS3D) became effective. EU member states have until July 26, 2026, to transpose the directive into national law, with the directive applying to companies in progressive stages from 2027 to 2029. In May 2024, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published updated guidelines for funds with ESG- or sustainability-related terms in their names. And in October 2024, the U.K. government published its response to the consultation on introducing a U.K. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and confirmed that, from January 1, 2027, the U.K. CBAM will place a carbon price on some of the most emissions-intensive industrial goods imported into the U.K. On November 7, 2024, the Loan Market Association (LMA) published its “Draft Provisions for Green Loans” (the LMA Green Loan Provisions). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).