1. Introduction

The current stage of global economic development is characterized by increasing climate challenges and the urgent need to transition toward a low-carbon growth model. The mobilization of substantial financial resources for the implementation of environmentally oriented technologies in the alternative energy sector represents a powerful solution. Contemporary studies [

1,

2,

3] emphasize that the use of biofuels, hydrogen, biogas, and synthetic fuels constitutes a key direction of the energy transition, which will reduce dependence on fossil fuels, decrease greenhouse gas emissions, and facilitate the achievement of international climate goals [

4].

Despite its considerable potential, innovative projects in alternative energy remain highly capital-intensive, technologically uncertain, and characterized by long investment cycles and elevated risks, which diminish their attractiveness for traditional sources of investment. This situation necessitates the development of specialized financial mechanisms capable of both mobilizing large volumes of capital and effectively distributing risks among investors [

1].

Despite the growing demand for innovative financial instruments, green bonds have taken on a particularly important role. They combine the function of attracting investment resources with mechanisms for managing environmental risks, thereby creating favorable conditions for the development of the alternative fuel sector. Furthermore, green bond issuance promotes the diffusion of ESG principles among issuers, enhances the transparency of financial flows, and provides additional incentives for corporate environmental responsibility [

1]. At the international level, green bonds are actively used to finance projects in energy efficiency, renewable energy, sustainable water resource management, and environmental protection [

5]. However, their direct impact on the formation and development of the alternative fuel market remains underexplored, emphasizing the need for further scientific investigation.

On the one hand, the strengthening of regulatory pressure aimed at reducing the carbon footprint, and on the other hand, the necessity for financial markets to adapt to new environmental realities, further reinforce the relevance of this topic. Therefore, identifying the interconnections between the dynamics of the alternative fuel market and the use of green finance instruments plays a crucial role in shaping effective sustainable development policies, creating a favorable investment environment, and enhancing the global competitiveness of the energy sector.

The present study is based on the concepts of sustainable finance and institutional theory, which have demonstrated that the long-term market value of companies increasingly depends on their ability to integrate social and environmental priorities into strategic development models [

6,

7,

8,

9]. The issuance of green financial instruments, in this context, is considered both a financial mechanism and a driver and signal of the issuers’ readiness to undertake environmental transformation and contribute to achieving global climate commitments.

The purpose of this article is to analyze, systematize, and enhance the theoretical and methodological foundations for the development of green financial markets and to identify the interrelationship between green bond issuance and renewable energy development across time and space. To achieve this goal, the study aims to: investigate the theoretical and methodological aspects of financial market functioning under green transformation conditions; define the variables of the study; substantiate the mathematical tools applied; construct econometric models; analyze the interrelationships among the identified variables.

We propose following hypotheses of the study:

Hypothesis 1:

strong interrelation between issuance and green bonds is present in time series.

Hypothesis 2:

green bonds are causes of the changes in renewable energy’s dynamic.

Thus, based on the solutions to the proposed tasks, we will analyze the proposed hypotheses in the context of the study's overall purpose.

2. Literature Review

Currently, the global economy is characterized by large-scale transformational processes aimed at achieving climate neutrality, decarbonizing production, and enhancing the efficiency of resource utilization. The European Green Deal outlines the primary directions for economic growth among European Union (EU) member states, integrating environmental priorities, technological advancements, and enhancements to business competitiveness [

4]. The ongoing green transformation creates conditions for economic recovery through the development of innovative sectors, diversification of energy sources, reduction of dependence on fossil fuels, and stimulation of investments in renewable technologies [

2,

3].

A distinctive feature of business development based on sustainability principles is the ability of enterprises to integrate into green mechanisms and develop strategies aligned with the European Green Deal. Under these conditions, there is a need to revise business models to ensure the transition to innovative technologies, optimize energy consumption, and incorporate social responsibility principles. Studies by leading scholars [

10,

11] demonstrate that combining environmental priorities with competitive strategy can help mitigate risks, create new market niches, and enhance economic resilience.

Modern financial instruments for sustainable development are gradually shaping a new market architecture that supports long-term, environmentally and socially significant investments [

1,

5]. On the one hand, the development of the green financial market contributes to attracting capital for the financing of environmental innovations and enhances business transparency; on the other hand, it stimulates enterprises to adapt to ESG criteria [

12,

13]. Given the continuous increase in environmental and climate-related risks that affect financial stability and long-term business competitiveness, the evolution of the green financial market is becoming increasingly important [

14,

15].

2.1. Modern Financial Markets in the Context of the Sustainable Development Paradigm

Modern financial markets are undergoing significant transformations under the influence of the concept of sustainable development, which integrates economic, social, and environmental priorities into financial flows and has become the focus of numerous studies by leading scholars [

16,

17]. Traditional investment instruments are being gradually supplemented by mechanisms of ‘’green” and sustainable finance, among which green bonds, sustainable investment funds, and other responsible investment tools occupy a leading position [

12,

18]. This evolution of financial markets is driven by the need to mitigate the risks associated with transitioning to low-carbon economic models and ensure energy security [

2,

19].

The significant development of the green bond market demonstrates both growth in issuance volumes and structural changes in approaches to assessing investment risks and financing efficiency, as evidenced by the studies of Grishunin et al. [

1] and Demski et al. [

5]. Under these conditions, financial market institutions act as both intermediaries in capital redistribution and drivers of environmental transformations, shaping new standards of transparency, reporting, and corporate governance [

20,

21].

In recent years, the interconnection between green financial instruments and traditional market assets has intensified, as indicated by the works of Ferrer et al. [

22], Yadav et al. [

23], and Marín-Rodríguez et al. [

24]. Scholars have identified a dynamic interaction between green bonds, energy markets, and stock indices, indicating the integration of green instruments into the overall financial system and their dependence on macroeconomic fluctuations. It can therefore be concluded that modern financial markets reactively respond to the challenges of energy transformation and, in general, determine its pace and scale through investment mechanisms.

Regional and Institutional Features of Financial Market Development in the Context of Sustainable Development

In EU countries, the green bond market evolves in close connection with the implementation of climate policy and the European Green Deal [

4], ensuring consistency between financial flows and strategic decarbonization goals [

25]. However, in developing countries, the green financial sector faces challenges such as institutional instability, underdeveloped market infrastructure, and information asymmetry, while simultaneously creating opportunities to attract long-term investments in renewable energy [

26].

The paradigm of sustainable financial market development emphasizes a balance between innovation and regulatory requirements. On one hand, the introduction of green instruments stimulates the development of renewable energy and low-carbon technologies [

10,

14]; on the other hand, there is an increasing need to prevent “greenwashing” risks and to form unified approaches to verifying the results of environmental investments [

27].

Modern financial markets continually integrate sustainable practices into their operational mechanisms, ensuring both capital redistribution and the institutional foundation for economic and environmental transformation. It can be concluded that the current stage of financial market and instrument development illustrates the combination of innovation and regulatory constraints, as well as the growing role of financial mechanisms in supporting low-carbon economic transformation. Therefore, financial markets, as reactive elements of the economic system, determine the pace and scale of energy and environmental transformation.

2.2. Institutional Foundations of the Sustainable Finance Market Formation

The formation of the sustainable finance market cannot be effective without a strong institutional foundation that ensures trust, transparency, and accountability. When studying sustainable finance, it is appropriate to refer to institutional theory, which explains economic behavior as the result of the interaction between social norms, rules, and cultural expectations. In this regard, Eitrem et al. [

8] analyzed how institutional approaches are applied to environmental responsibility and the assessment of green finance dynamics.

Recently, the literature [

9,

21] has actively explored the synthesis of institutional theory and stakeholder theory, which emphasizes that both companies and financial institutions must consider the interests of investors, society, the environment, and government bodies. Hörisch et al. [

21] argue that such synthesis contributes to the formation of an integrated model in which institutions promote sustainable development through a system of incentives, sanctions, and norms.

Thus, institutional aspects establish the rules of the game in the “green” financial market, including the conditions for issuing green financial instruments and the mechanisms for monitoring the use of raised investments. Within the institutional framework, standards, rules, and procedures are established to define the “greenness” of projects and audit criteria [

28]. The results of Pyka’s М. [

29] study on the implementation of the EU Green Bond Standard project show that strict requirements for transparency, compliance, and independent verification increase market confidence.

Regulatory initiatives regarding the disclosure of companies’ ESG information create the prerequisites for the effective functioning of the sustainable finance market [

18]. Iris S [

30] examined how regulatory frameworks and decentralized approaches integrate sustainable financial practices into the general market context. Integrity, the rule of law, and low levels of corruption ensure the effective implementation of environmental projects. The study by Sun et al. [

31] found that countries with a high level of institutional support are more effective in introducing green financial instruments.

Furthermore, the research by Kellard et al. [

32] highlights the importance of the national institutional context, showing that property rights protection, the level of corporate law, and judicial protection mechanisms have a statistically significant impact on the ability of financial systems to support innovation in clean technologies.

In the context of sustainable finance market development, national and supranational institutions act as catalysts. In this regard, Spielberger L. [

33] emphasized the role of the European Investment Bank in shaping sustainable financial policy, concluding that it actively promotes green bonds within EU policy.

Moreover, state climate and emissions regulation policies can encourage issuers to commit to green bond frameworks. Demski et al. [

5] argue that countries with stricter climate policies demonstrate faster growth in green bond issuance driven by regulatory impulses.

It is also important to consider that institutional mechanisms must address the problem of information asymmetry, as investors cannot always assess how “green” a project truly is a concern highlighted by Eitrem et al. [

8] and Galleli et al. [

9]. Insufficient transparency or data disclosure leads to “greenwashing.” Shannon et al. [

27] extensively examined the risks of information leakage and data unreliability, underscoring the need for institutional control and transparency in sustainable finance markets.

2.3. Models of Financing Renewable Energy Projects

The development of the renewable energy market requires the mobilization of substantial financial resources, which cannot always be provided through traditional lending mechanisms or national budgets. Under such conditions, innovative financing models that combine market instruments with the principles of sustainable development and account for low-carbon transition risks become particularly important.

Currently, the issuance of green bonds is regarded as a powerful instrument for financing the renewable energy sector and has evolved into a strategic financial mechanism supporting energy transitions. Studies by Grishunin et al. [

1] and Demski et al. [

5] confirmed that the issuance of green instruments facilitates the mobilization of capital at the international level while enhancing corporate governance transparency. Green bonds not only ensure access to long-term investment resources but also reduce financing costs through diversification of sources and an improved issuer reputation [

13,

34].

Recent studies by Frolov A. [

28] and Sholudko et al. [

35] highlight the increasing popularity of project financing, in which a special-purpose project company is established to accumulate capital for future cash flows from renewable energy production. Compared to other models, this approach minimizes investor risk by distributing it among all project participants, enabling the use of flexible insurance mechanisms and government guarantees.

Alongside project-based approaches, public-private partnerships are gaining increasing importance in modern practice. These arrangements combine the investment potential of the private sector with the organizational and regulatory support of the state [

15]. Such a format is particularly effective for large-scale renewable energy infrastructure projects that require long payback periods and significant capital investment [

26].

The financial architecture of the “green” energy sector is based on flexible market instruments [

23,

36,

37], including green funds, climate directives, and carbon certificates. Research indicates that these flexible tools provide mechanisms for managing price volatility in energy markets and fluctuations in carbon certificate values.

Modern models of renewable energy project financing are thus built on a synergy between market mechanisms, public policy, and institutional frameworks. They encompass both classical forms of capital attraction and innovative instruments that combine financial benefits with environmental objectives. In the context of this study, the focus is placed on green bonds as a key instrument for financing the renewable energy market.

2.4. Green Bonds in the Context of the Sustainable Transition Concept

In contemporary literature [

11,

38,

39,

40,

41], green bonds are increasingly perceived as a driver of structural transformations in financial and economic systems. As noted by Zhou et al. [

11], the primary motivations for their issuance include the opportunity to attract new funding sources, companies' desire to improve environmental performance, and the aim to enhance competitiveness. These conclusions are consistent with the provisions of institutional theory, as discussed above, which posits that financial markets adapt their mechanisms in response to environmental challenges and regulatory constraints.

In this regard, Andersson et al. [

38] and de Jong et al. [

39] emphasized that the issuance of green financial instruments serves as a market signal of companies’ readiness to manage climate risks and integrate ESG principles into corporate governance systems.

Contractor et al. [

40] found that market reactions to global shocks vary: while green bonds display increased sensitivity to atypical events, investors in this segment tend to focus on long-term prospects linked to climate policy and sustainable development commitments. Based on these findings, green bonds can be viewed as an indicator of the pace and direction of energy transition financing.

Furthermore, Lu et al. [

41] demonstrated that the issuance of green bonds has a statistically significant positive effect on the environmental performance of funded projects. These conclusions are particularly relevant for EU member states, where the renewable energy market actively integrates sustainable finance instruments. Such results open promising avenues for further research on the relationship between the growth of green bond issuance and the intensification of investments in renewable energy sources.

When examining green bonds in the context of the sustainable transition, it is also important to highlight the contribution of Giglio et al. [

19], who substantiated the functional role of green finance. The authors concluded that financial flows directed toward mitigating climate risks foster sustainable transition and enhance the long-term resilience of financial systems.

Thus, it can be concluded that green bonds both reduce risks associated with the physical manifestations of climate change and mitigate transitional risks arising during economic decarbonization. This reasoning explains the integration of ESG factors into modern financial management practices and the growing interest of institutional investors in these instruments.

2.5. Issuance of Green Bonds as a Financial Instrument

Unlike conventional debt obligations, green financial instruments are specifically designed to mobilize capital for financing environmental projects and sustainability-oriented initiatives. Their emergence signifies the formation of a new model of interaction between financial and non-financial factors in the investment process. Theoretically, green bonds are grounded in the principles of institutional economics, which explain the rise of innovative financial tools as a response to sustainable development challenges, as well as in the ideas of stakeholder theory discussed in the previous section. In this context, green bonds are viewed not only as a debt instrument but also as an integral component of a corporate strategy for creating shared value.

According to Flammer С. [

34], the issuance of green bonds generates a dual effect: it provides companies with access to diversified financial resources, strengthens their reputation, and enhances their long-term market capitalization. Tang et al. [

42] identified that green bonds can reduce costs associated with information asymmetry; in other words, the higher transparency requirements regarding fund utilization help mitigate conflicts between management and investors.

Today, the green financial market is regarded as a strategic tool for building competitive business advantages amid global environmental transformation [

43]. Jin et al. [

36] argue that green bonds help hedge risks in carbon markets, thereby enabling better management of environmental and market challenges. It can thus be concluded that green instruments are becoming integrated into the global financial system, where ESG metrics are gaining equal importance alongside traditional indicators of profitability and risk.

The study by Lebelle et al. [

44] demonstrated that the development of the green bond market fosters greater transparency in financial flows and harmonization of disclosure standards, thereby laying the groundwork for a new architecture of global financial governance. As a result, the institutionalization of green finance is underway, acting as a powerful catalyst for structural shifts in capital allocation.

We argue that green bonds serve a dual function: on the one hand, as an investment tool, they provide access to resources for implementing environmental projects; on the other hand, as a strategic management instrument, they reinforce investor confidence and align the interests of shareholders, managers, and society. More broadly, green bonds should be viewed as a manifestation of the transition from a traditional profit-oriented financial model to the paradigm of sustainable finance, where socio-environmental criteria and long-term economic resilience become the defining priorities.

2.6. Conceptual Aspects of Green Bonds

In the current global shift toward clean energy sources, green bonds have gradually established themselves in the literature as a powerful financing instrument for alternative fuel projects [

2,

20]. Their uniqueness lies in combining the classical functions of debt instruments with the achievement of sustainability goals. This transforms green bonds into a practical embodiment of dual materiality ensuring financial returns while generating social and environmental benefits [

7]. Let us examine the conceptual foundations of green bonds from the standpoint of several theoretical perspectives.

From the perspective of institutional economics, the emergence of green bonds reflects changing rules of financial market operation under the influence of climate risks and environmental challenges [

8,

9]. The demand for “green” instruments arises from a combination of market and regulatory incentives shaped by EU climate agreements and the Sustainable Development Goals [

20,

29]. Semieniuk et al. [

3] concluded that the financial sector increasingly acts as a transmission channel for low-carbon transition risks to the macroeconomic dimension.

According to signaling theory [

45], the issuance of green bonds functions as a reputational marker demonstrating a company’s commitment to environmental responsibility principles. Additionally, by lowering the cost of capital, green bonds strengthen institutional trust and stimulate additional investor demand [

34,

45]. A characteristic feature of this market is the “greenium” phenomenon, whereby investors accept lower yields on green securities compared to conventional bonds, compensating for this trade-off with non-financial benefits such as environmental impact [

1,

5]. The “greenium” and its significance in this research will be analyzed in detail below.

From the perspective of agency theory [

27,

42,

46], green bonds reduce information asymmetry between management and investors because issuers are required to disclose information about the environmental impact of financed projects and adhere to non-financial reporting standards. Tang et al. [

42] found that reducing information asymmetry leads to lower agency costs and improved capital use efficiency.

“Greenium” in Modern Financial Markets

The “greenium” phenomenon has recently gained a prominent place in academic discussions on the functioning of the green bond market [

1,

5,

13,

17,

29,

45]. Researchers note that investors consciously accept lower returns on green financial instruments compared to equivalent conventional debt securities, motivated by non-financial benefits [

1,

5]. This compromise is explained by several factors:

The increasing significance of non-financial priorities in investment behavior, where market participants focus on long-term sustainability rather than short-term gain [

9];

The “greenium” acts as a signal of issuer responsibility and alignment with ESG principles [

45];

The presence of green premiums reflects the influence of regulatory and political factors that stimulate demand for environmentally oriented financial instruments [

3,

29].

However, the “greenium” is not constant across time and regions. Goel et al. [

17] and Chen et al. [

26], using econometric modeling, demonstrated that in advanced financial systems, the “greenium” is more pronounced due to strong demand and developed transparency infrastructure. Conversely, in developing economies, its magnitude depends on data availability, issuer credibility, and the overall institutional environment. Shannon et al. [

27] observed that, in some cases, the “greenium” effect may weaken or even disappear if markets are underdeveloped or investors doubt the environmental credibility of claimed projects.

After analyzing the theoretical foundations of green bonds, we conclude that they form a multidimensional concept of sustainable finance encompassing:

economic dimension: reduced cost of capital, emergence of the “greenium,” and development of responsible investment markets [

1,

5];

institutional dimension: institutionalization of market rules and strengthening of the regulatory framework for sustainable finance [

30,

33];

managerial dimension: increased transparency, accountability, and corporate governance efficiency [

21,

31];

socio-environmental dimension: directing financial flows toward climate projects and enhancing the long-term resilience of economic systems [

19,

25].

Therefore, green bonds should be regarded as a fundamental architectural element in transforming the global financial system, synchronizing market mechanisms with climate policy and the imperatives of sustainable development, while ensuring economic, managerial, institutional, and socio-environmental balance.

2.7. Green Bonds and the Development of the Alternative Energy Market

Modern research unequivocally indicates the continuous development of alternative energy markets worldwide [

2,

5,

14,

15,

24,

26,

41,

43,

47]. In this context, green bonds are considered a powerful instrument for mobilizing financial resources. Barua et al. [

43] found that the volume of green financing is directly dependent on the institutional capacity of the state. Using econometric modeling, the authors proved that the quality of the regulatory environment, the level of transparency in financial mechanisms, and the stability of legal norms justify the scale of investment in alternative energy. A similar conclusion was reached by Lu et al. [

41], who, using the matching method, found that the issuance of green bonds significantly expands access to capital for energy projects. At the same time, the presence of government commitments to decarbonization strengthens the effectiveness of “green” instruments, demonstrating a close link between political goals and the efficiency of financial decisions.

The undeniable effectiveness of green bonds is confirmed in the study by Shah et al. [

14], who identified a sustainable, positive, and statistically significant relationship between the volume of their issuance and the dynamics of investment in renewable energy. Therefore, green bonds can be seen as a catalyst for the development of low-carbon technologies. Similar results are presented in the work of Chen et al. [

26], which revealed a causal relationship between the expansion of the green bond market and the growth of renewable energy production in developing countries. Chen et al. [

26] substantiated a multiplier effect that generates additional opportunities for economic growth and advancement of decarbonization goals.

In a large-scale study by Alharbi et al. [

15], which included more than 100 countries, it was found that increasing the volume of green bond issuance is closely correlated with the growth of investments in solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy projects. Alharbi et al. [

15] also noted that the effectiveness of “green” instruments is statistically significantly dependent on a stable political environment and the presence of incentive regulatory practices. Zhao et al. [

10] analyzed the impact of green bond issuance at the micro level and found that companies implementing projects financed by green bonds demonstrated higher profitability and lower capital costs compared to those using traditional mechanisms.

Marín-Rodríguez et al. [

24] demonstrated that the expansion of green bond issuance has a stabilizing effect, mitigating the consequences of oil price fluctuations while promoting capital inflow into the green energy sector. Using portfolio analysis, Ferrer et al. [

22] determined that the green bond market is highly integrated into the system of traditional financial assets but shows weaker correlation with oil market dynamics, providing a foundation for its autonomous development.

In the study by Bajo et al. [

27], the concept of “green parity” was proposed, which aims to balance the yield and risk profiles of green and conventional corporate bonds. This justified approach aligns with the climate priorities of EU policy and demonstrates the institutional consolidation of green instruments within financial portfolios. Therefore, it can be concluded that green bonds already play a dual role as both an alternative source of financing and an integral element of a broader financial ecosystem within the European green transformation strategy.

2.8. Regulations and Limitations of Green Bonds

As noted earlier, the development of the green bond market directly depends on the political and regulatory frameworks that define its functioning and build investor trust. At the international level, scholars such as Shannon et al. [

27] emphasize the significant role of standards that unify approaches to assessing project “greenness,” financial transparency, and issuer accountability. The regulatory document “EU Green Bond Standard” has recently become a leading foundation for harmonizing the rules of green bond issuance across EU member states, as it sets clear requirements for fund allocation, environmental monitoring, and reporting [

13,

27].

National legislative initiatives create a favorable environment for capital mobilization through tax incentives, state guarantees, and support mechanisms for corporate and municipal issuers [

35,

48]. However, the absence of a unified methodology for evaluating environmental projects and the insufficient integration of ESG criteria into financial practice remain key obstacles [

25]. Establishing clear rules for selecting “green” projects will minimize the risks of misuse of investment funds and enhance the investment attractiveness of the renewable energy sector [

28].

Despite the positive dynamics of green financial instrument development, the literature [

18,

46,

47] describes a number of constraints that hinder their effectiveness. Joshipura et al. [

46] highlight the phenomenon of “greenwashing,” where issuers attract green bonds to finance projects that lack genuine environmental impact. Bajo et al. [

47] concluded that there is no parity between green and traditional financial instruments, as the former tend to have lower liquidity. Singhania et al. [

18] identified the lack of empirical research on the impact of green bonds on the transformation of the energy sector as a significant limitation.

Semieniuk et al. [

3] highlighted the importance of “transitional risks,” where the reallocation of capital into alternative fuel production reduces asset values and creates financial bubbles. Qiuwen et al. [

2] highlighted legal uncertainties in the implementation of new technologies, particularly in relation to ammonia toxicity and methane leakage risks.

Flottmann et al. [

12] identified another limitation of the green bond market its focus on broad “green” projects without clearly defining the share of funds directed toward alternative fuels. The lack of sectoral detail complicates the assessment of the effectiveness of financial support for specific innovations and limits the ability to forecast their impact on economic development. Shannon et al. [

27] further supplement these limitations by highlighting possible information distortions that alter market expectations and affect the distribution of investment flows.

3. Methodology

The review of the literature on financial markets, green financial instruments, and their interrelations with renewable energy markets has revealed a diversity of approaches used by scholars to justify the dynamics of contemporary financial and environmental integration.

Researchers Chen et al. [

26], applying the Generalized Method of Moments to a sample of developing countries, proved the existence of a direct relationship between the development of the green bond market and the growth of electricity generation from renewable sources. Similarly, Zhao et al. [

10] found that the attraction of green financing increases the investment efficiency of clean energy projects.

Hammoudeh et al. [

49] used Granger causality to identify how fluctuations in the green bond market affect indicators of environmental and financial stability. Marín-Rodríguez et al. [

24] applied VAR models to examine the relationship between green bond issuance volumes, oil prices, and CO₂ emissions, demonstrating the stabilizing effect of these instruments during periods of energy market volatility.

Ferrer et al. [

22] used portfolio analysis to assess the interdependence between green financial assets and traditional instruments, identifying the relative autonomy of the green bond market. Yadav et al. [

23] combined the Granger Causality method with portfolio analysis to investigate the synchronization of movements between green bonds, energy commodities, and stock indices.

Le et al. [

16], using a model of dynamic spillover effects analysis, determined that fluctuations in investor sentiment can amplify intermarket linkages. Demski et al. [

5] investigated the long-term impact of green bond market expansion on reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Lu et al. [

41] applied Propensity Score Matching to quantitatively assess the impact of green bonds on the probability of implementing renewable energy projects. Zhao et al. [

10] substantiated that the use of “green” instruments can optimize the risk–return profile compared to traditional financing mechanisms.

The modern methodological foundation of such studies is based on the integration of a set of econometric and mathematical models. Their comprehensive use enables the identification of statistically significant relationships between green bonds and renewable energy development, as well as the drawing of conclusions about the stabilizing and multiplier effects of “green” financial instruments in the context of the global energy transition.

4. Materials and Methods

Our study will be based on the three tasks in the previous chapter.

Task 1. Determination of the variables of the study.

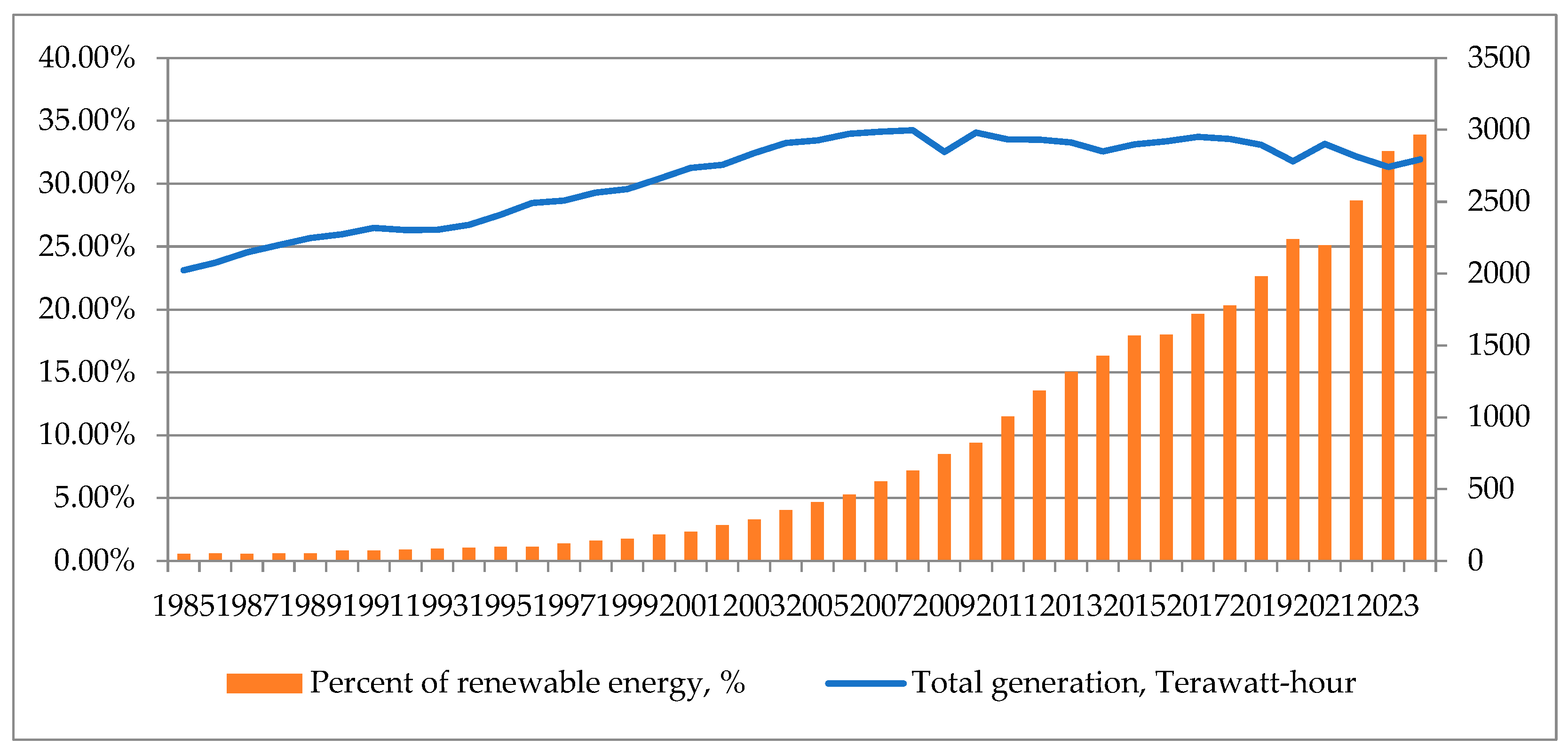

Renewable energy has big potential in development. The dynamics of renewable energy development are illustrated in

Figure 1.

The data on the

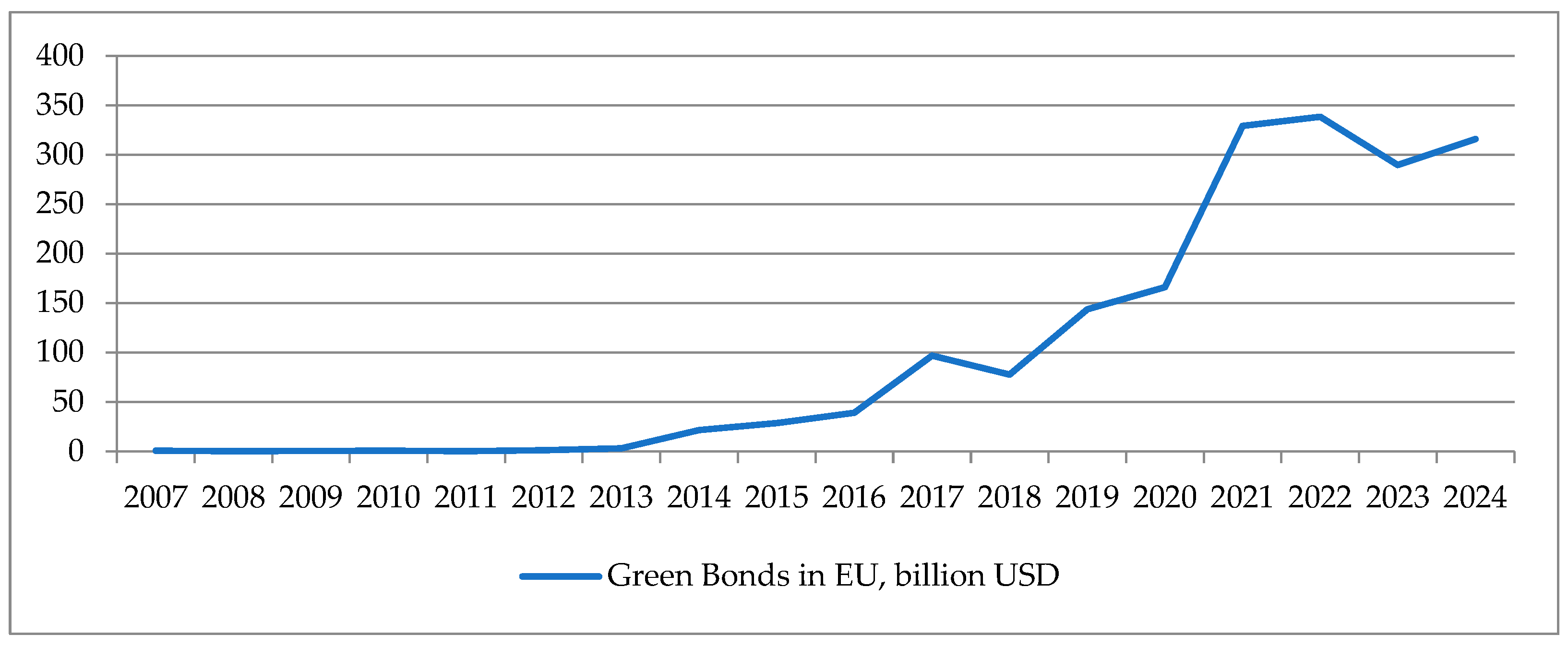

Figure 1 shows us about big increasing of the percent of the renewable energy in total energy production. The world economy has two main factors of this increasing. First one is the technology development in the world and decrease the value of the production of the renewable energy. Second one is the financial support of the renewable energy. Subsiding, dotation, decrease taxes, different financial tools help in development of the renewable energy. One of the financial supporting of the development of the renewable is green bonds. Green bonds were created in 2007 year by European Investment Bank. The dynamic of the Green Bonds in EU is present in the

Figure 2.

What is the reason we choose the green bonds in EU, because the EU has 54.7% of green bond’s market in the world and 13/8% of the renewable energy production in the world? If we look the structure of the renewable energy production in EU we can see that solar energy has 18.8% of total renewable energy production in EU and 14.8% production in the world; wind energy has 29.1% of total renewable energy production in EU and 19.5% in the world.

Thus, we choose following variables in our study:

S – the production of the solar energy in the EU;

W – the production of the wind energy in the EU;

T – the production of the total energy in the EU;

Y – the issuance of green bonds in the EU.

The period of the study is 2007 - 2024 years.

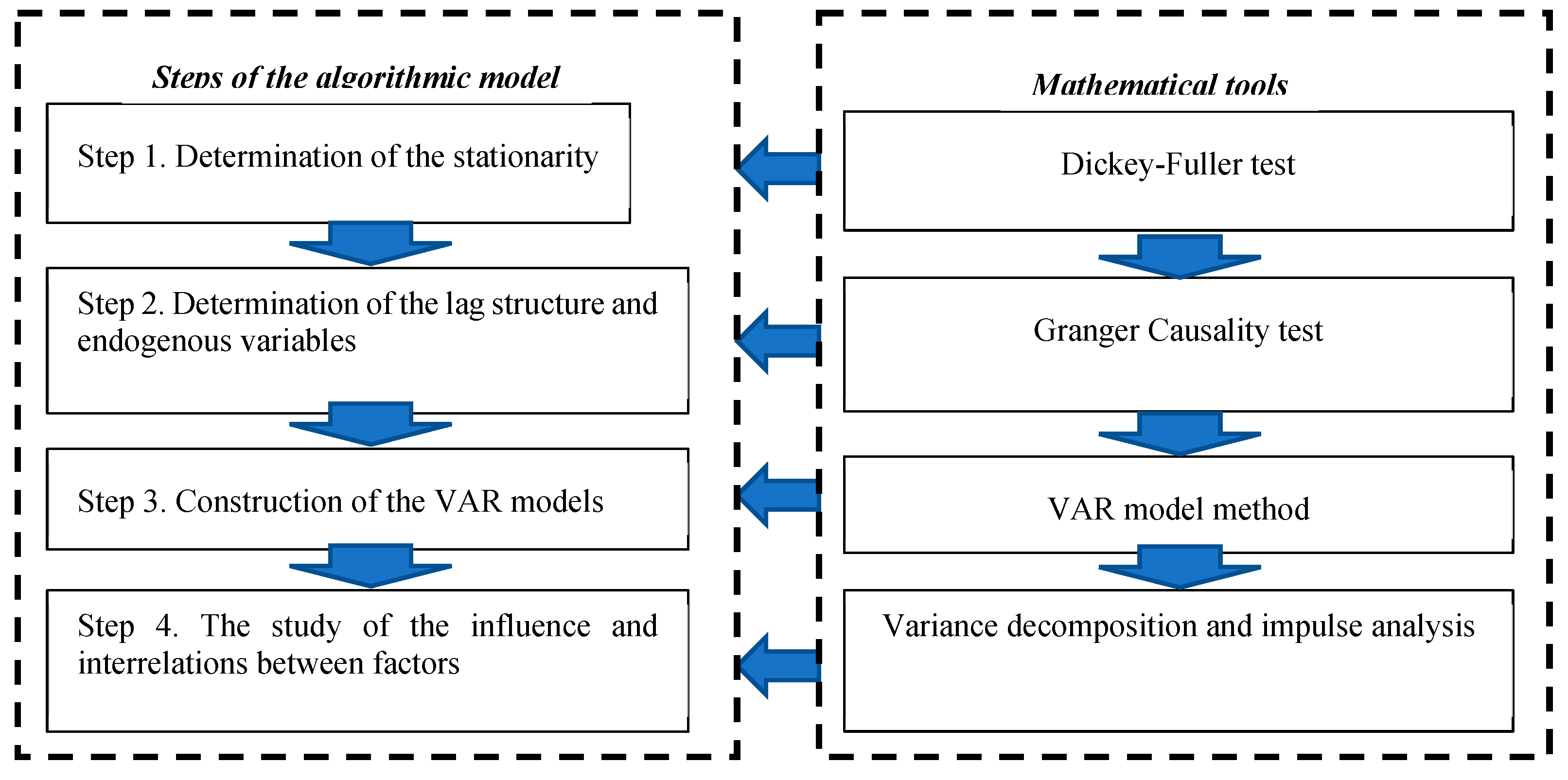

Task 2. Choosing the mathematical tools for the investigation.

A lot of mathematical methods used for the study of the interrelation between two or more factors. Purpose of the paper is find not only interrelation between factors but also the determination of the cause and effect in factors and the finding level of influence one factor on the others. Therefore, we propose to use the following algorithmic model for the purpose of our study (

Figure 3).

Let's consider the steps of this algorithm in more detail.

Step 1. Determination of the stationarity of time series.

A stationary process has the property that the mean, variance and autocorrelation structure do not change over time (Nist/Sematech, 2012). Stationarity can be defined in precise mathematical terms. In our paper stationarity is a flat looking series, without trend, constant variance over time, a constant autocorrelation structure over time and no periodic fluctuations. We use the Augmented Dickey Fuller test for the checking of the stationarity. ADF tests the null hypothesis that a unit root is present in a time series sample. The alternative hypothesis depends on which version of the test is used, but is usually stationarity or trend-stationarity. It is an augmented version of the Dickey–Fuller test for a larger and more complicated set of time series models [

51].

Step 2. Determination of the lag structure and endogenous variables.

Granger Causality test is mathematical tool of this step. Green bonds are financial instrument of the supporting renewable energy, in this case usually finance give impact with lag. For this we will use Granger Causality test to check lag structure and causality between studied factors.

Step 3. Construction of the VAR models.

VAR models are traditionally widely used in finance and econometrics because they offer a framework for accomplishing important modeling goals, including [Stock and Watson 2001]: data description, forecasting, structural inference, and analysis. The general VAR model with

n variables is

where n – the number of variables; p – optimal lag of the VAR model.

Step 4. The study of the influence and interrelations between factors.

Impulse analysis and variance decomposition are most powerfully tools for the study of interrelations between factors in the VAR models. Impulse response analysis is a crucial step in econometric analyses that employ VAR models. Their main purpose is to describe the evolution of a model’s variables in reaction to a shock in one or more variables. This feature allows to trace the transmission of a single shock within an otherwise noisy system of equations and, thus, makes them very useful tools in the assessment of economic policies. This technique, common in econometrics and signal processing, helps understand how systems react to changes by measuring the propagation and diminishing impact of a shock on variables in models like VARs, ARs, or state-space models.

Variance decomposition in VAR models describes how much of the forecast error variance for each variable is explained by shocks to that variable itself versus shocks to other variables in the system over time. It helps identify the relative importance of different shocks to the variables within the VAR, revealing which external factors have the greatest impact on each variable's variability

5. Results

Based on the algorithmic model will check the results of the construction models (task 3 and task 4).

Task 3. Construction of the mathematical models

The first step of the study is checking stationarity by ADF test. The results of the checkin are present in

Table 1.

The results of

Table 1 show that all initial time series are non-stationarity, therefore we made transformation of the time series by first differences. The results are present in

Table 1. First differences of the time series are stationarity. Thus we can use these time series for detailed study.

Second step is determination of the lag structure of VAR models. The results of the calculation of Granger Causality test for the study of lag structure are present in

Table 2.

The data of

Table 2 show us about statistically significant lag with 2 years. We will calculate VAR models with this lag.

The choice of two lags (lag = 2) in the Granger model is justified by the results of the information criteria (AIC, SC, HQ) and the likelihood test (LR), which demonstrate minimum values precisely at this level. This means that the dynamic relationships between the variables (green bond issuance (Y) and energy production from various sources (S, W, T) manifest themselves with a time lag of two periods.

From an economic sense, this logically reflects the time inertia between financial and energy processes: funds raised through green bonds require a certain amount of time to implement investment projects in the field of renewable energy. Typically, this is 1-2 years, which is needed to design, build or commission new capacities. Thus, a two-period lag reflects the real time gap between financing and the actual increase in energy production.

Granger Causality test study examines the causal relationship between:

Y → S - whether green bond issuance affects solar energy production;

Y → W - whether green bonds stimulate wind energy development;

Y → T - whether the growth of green financial instruments contributes to an increase in overall renewable energy production;

S/W/T → Y - whether the pace of RES development affects the further growth of green bond issuance.

Possible Granger Causality test result scenarios:

1. Unilateral causality (Y → S, W or T): indicates that the green bond financial market is a driving force for the development of renewable energy. This highlights the effectiveness of market mechanisms in financing environmental projects.

2. Reverse causality (S, W or T → Y): indicates that the growth of green energy production generates demand for further issuance of green bonds, as investors see successful examples of project implementation and growth of the industry.

3. Bidirectional causality: implies interdependence between the development of the green financial instruments market and the renewable energy sector. This scenario reflects a feedback effect, where financial flows stimulate energy investments, and the success of energy projects, in turn, increases the attractiveness of the green bond market.

The third step of the algorithmic model is construction of the VAR models and finding of the parameters. The results of the calculation of the parameters of VAR models are present in the

Table 3.

As we look, R-squared is high, it’s mean that VAR models are statistically adequate and we can use it to the analysis of the interrelation between factors.

Analysis of the parameters of the models got following results:

- i)

All lag structure of the energy factors besides wind factor show positive influence on the development of issuance of green bond (parameters with lag 1 and lag 2 are positive);

- ii)

Production of the total energy have most influence on the green bond in one piece in quantity equivalent

The results of the analysis by types of the energy:

i) Solar Energy (S). Strong autocorrelation is observed within the solar energy sector (S(-1) = 1.556), indicating that current production depends significantly on previous levels. The negative second lag (-0.444) suggests short-term stabilization after growth periods.

ii) Wind Energy (W). Coefficients W(-1) = -0.601 and W(-2) = -0.268 reveal a cyclical development pattern due to capital intensity and seasonality. Positive effects from solar energy (S(-1) and S(-2)) highlight synergy between renewable sources.

iii) Total Energy (T). Moderate negative autocorrelation (T(-1) = -0.65; T(-2) = -0.38) indicates potential regulatory or structural changes in the energy market. Negative coefficients show stabilization following growth surges. The influence of solar and wind energy on total output confirms intersectoral integration.

iv). Green Bond Issuance (Y). The highest determination level (R² = 0.876) indicates strong explanatory power. Positive Y(-1) and Y(-2) show market inertia - prior issuances encourage subsequent ones. The influence of wind and solar variables (e.g., W(-2) = 837.37; S(-1) = 59.54) demonstrates a financial-energy link.

In conclusion of the analysis of the VAR model see that the VAR model confirms a mutually dependent system where renewable energy production and green bond issuance influence each other. The most significant relationship is between green bonds and wind energy, reflecting investment capital needs. Lagged effects confirm the presence of time delays between financing and project realization

Task 4. Analysis of the interrelation between variables.

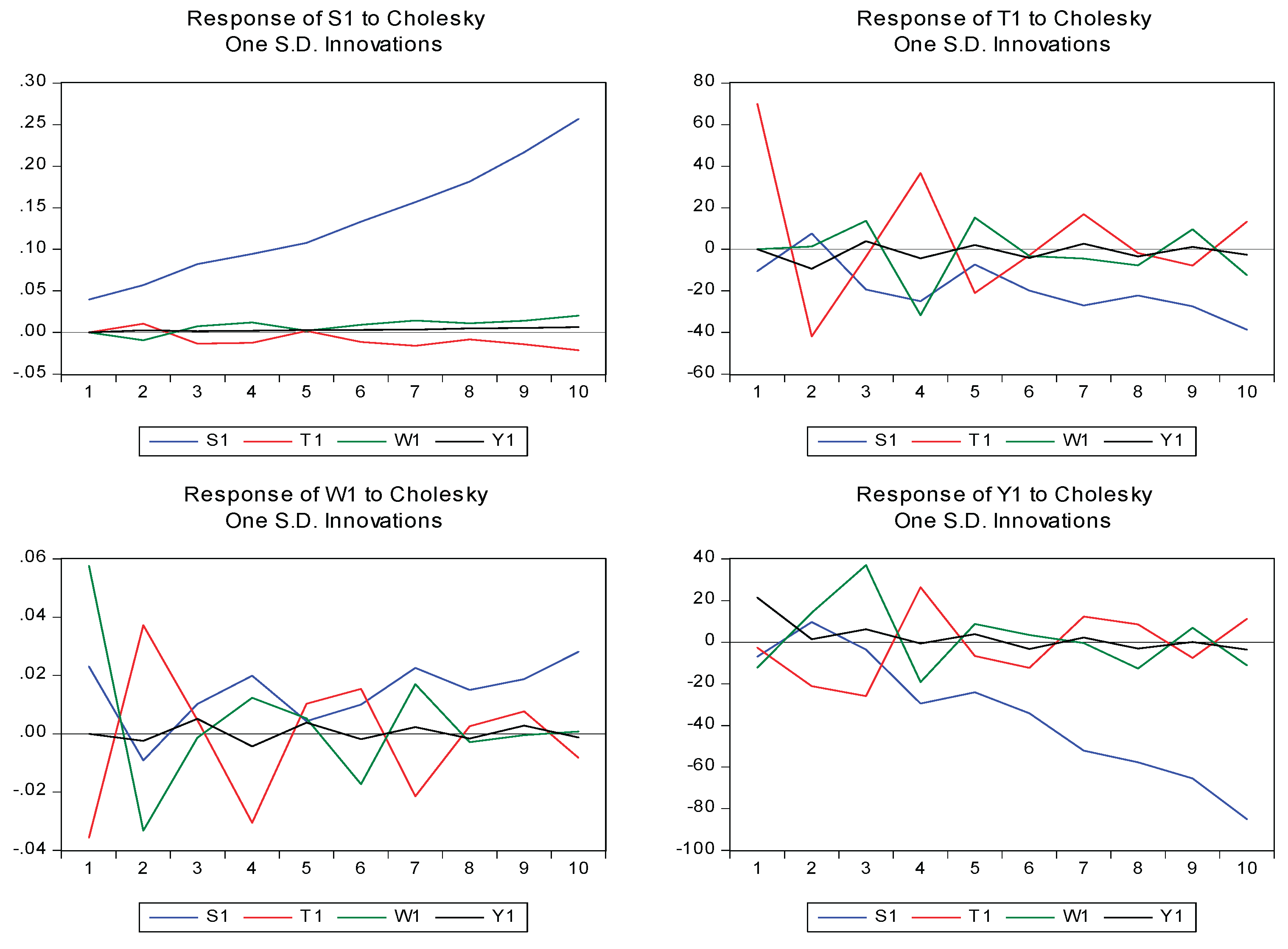

We calculated impulse analysis, and the results are presented in

Figure 4.

We made following conclusion:

- i)

The impulse response analysis illustrates how one standard deviation shocks in a particular variable affect other variables over time within the VAR system. The results for solar energy (S), total energy (T), wind energy (W), and green bond issuance (Y) reveal the short- and long-term interdependencies between the renewable energy sectors and the financial market

- ii)

The production of the solar energy has shocks only from solar energy dynamics. Total energy production depends from the shocks by itself (big shock) and other factors. Bot shocks have cyclic influence;

- iii)

Green bonds depend from all energy shocks, also solar energy shocks hve negative influence on the green bonds.

- iv)

Response of S1 (Solar Energy). A positive and persistent dynamic is observed: the response of solar energy increases steadily over ten periods, indicating that shocks in solar energy production have a long-term cumulative effect. Other variables (T, W, Y) show minor and oscillating reactions. In economic sense, the solar energy sector demonstrates a high degree of autonomy and self-reinforcement after positive shocks, reflecting the long-term effects of technological innovation and capital investments.

- v)

Response of T1 (Total Energy). Initially, the response shows strong fluctuations during the first 4-5 periods, followed by stabilization. Significant reactions to shocks in solar and wind energy confirm the impact of renewable sources on total energy production. The effect of green bond issuance (Y) is short-term and less pronounced. Total energy output reacts quickly to renewable energy dynamics but tends to stabilize, indicating that the overall energy system adapts to structural shifts caused by renewables.

- vi)

Response of W1 (Wind Energy). Wind energy exhibits high volatility in the short run, with strong oscillations following its own shocks. After the fifth period, the response stabilizes, and cross-effects from other variables weaken. Solar energy (S) exerts a mild positive influence in the medium term. Wind energy production is sensitive to short-term fluctuations, reflecting the influence of seasonality, capital intensity, and policy uncertainty, yet stabilizes over time as investments and capacity mature.

- vii)

Response of Y1 (Green Bonds). The issuance of green bonds initially declines due to a shock in solar energy but gradually increases afterward. Positive responses to its own shocks suggest market inertia, meaning previous issuances encourage future activity. Over time, solar and wind energy development contribute to the growth of the green bond market, confirming a feedback effect between energy transition and sustainable finance. The financial market reacts with a delay to renewable energy shocks but ultimately shows a stable, positive trajectory as investment opportunities in renewables expand.

Overall, the system demonstrates bidirectional causality: renewable energy growth stimulates financial market activity, while financial instruments such as green bonds, in turn, support further renewable energy investment

The impulse response analysis confirms the mutual dependence between renewable energy production and green bond issuance: solar energy acts as a long-term growth driver; wind energy is more volatile but stabilizes over time; total energy production absorbs shocks and stabilizes the system; green bonds display delayed but positive financial responses to renewable energy expansion.

For more investigated of the interrelation between energy and financial market we calculated variance decomposition. The data are in the

Table 4.

The analyses of the date from

Table 4 give following results:

- i)

Each energy production has long memory effect and depend from by itself in lag period (from 1 to 5 years)

- ii)

Second influenced factor for wind energy production is total energy production (has from 24.7% to 39%)

- iii)

Financial market has interesting fact. In first and second years green bond depend from by itself, but this influence has decrease tendency, from 39% in first year and 8.36% in fifth year). Wind energy production is second influenced factor wit peak influence in third period (49%). Also, total energy production has strong influence on the issuance of green bond. As, only 1.12% in the first year and 30%-32% in the next four years. Solar energy has increase tendency of influence during five years till 26.06% in fifth period.

- iv)

Main result is, from one hand, all energy production have big influence on the issuance of green bonds but green bond haven’t influence on the variance of the solar energy production.

Thus, we confirm hypothesis 1 and reject hypothesis 2 about influence green bonds on the development of renewable energy production. But we propose hypothesis 3 about strong influence renewable energy market on the issuance of green bond. And we confirm this hypothesis with helps of the data from

Table 4.

6. Discussion

The results obtained in the current study have facilitated a renewed understanding of the relationship between the green bond market and the dynamics of the renewable energy sector. Confirmation of Hypothesis 1 regarding the existence of a long-term dependence in time series indicates that the issuance of green bonds and the production of renewable energy have a “long memory.” Therefore, the trajectory of market development is largely determined by its own inertia, while past changes continue to exert a lasting influence on subsequent dynamics. These findings are consistent with those of Chen et al. [

26] and Hammoudeh et al. [

49], who identified long-term dependencies between financial and energy indicators as a key factor in forecasting their trends [

53].

The rejection of Hypothesis 2, concerning the causal influence of green bond issuance on renewable energy development, aligns with the conclusions of Demski et al. [

5], who found that green financial instruments primarily serve an indicative rather than a stimulating function. Our study showed that the impact of the green bond market on renewable energy production is limited, reflecting existing trends rather than generating new growth points.

Hypothesis 3, which is the inverse of Hypothesis 2, was confirmed during the study, indicating a strong influence of the renewable energy market on green bond issuance. It was found that wind energy had the greatest impact on the dynamics of green bonds in the third period (49%), while the role of solar energy gradually increased. These results are consistent with the conclusions of Marín-Rodríguez et al. [

24], who found that shifts in energy markets are a major driver of green financing activity.

The current study also shows that the share of total energy production influencing green bond issuance increases significantly over time, from 1,12% in the first year to over 30% in subsequent periods. This leads to the conclusion that green financial instruments are gradually being integrated into energy policy and market conditions [

54].

However, several issues remain open to discussion:

firstly, green bonds appear to act more as a derivative indicator of transformations in renewable energy rather than a direct driver of its development;

secondly, there is evidence of an asymmetric relationship - renewable energy significantly affects the green bond market, but not vice versa;

thirdly, the gradual strengthening of the role of solar and wind energy in determining financing dynamics points to a structural transformation of financial markets, where the “green” segment is increasingly integrated into macro-level markets.

7. Conclusions

Modern financial markets are gradually integrating green financing mechanisms, with green bonds, sustainable funds, and other responsible investment instruments gaining increasing popularity. These financial tools facilitate the accumulation of long-term investment resources for both conventional and environmental projects. The study concludes that modern “green” instruments are shaping a new institutional architecture of the market, based on the principles of transparency, trust, and accountability.

The analysis of the institutional dimension of sustainable finance market development has shown that it defines the rules of market access, certification procedures, and mechanisms for controlling the use of raised funds. The effectiveness of green instruments depends on a combination of market incentives and regulatory requirements, which set frameworks to prevent “greenwashing” risks and enhance the quality of corporate governance.

Modern models of “green” project financing are multidirectional, encompassing project financing, public–private partnerships, and innovative market-based instruments. These models allow for diversification of investment sources and the development of flexible financial mechanisms that account for the risks of the energy transition. Green bonds, as a modern financial instrument, perform a dual function: on the one hand, they attract capital to environmental projects; on the other, they serve as a strategic indicator of environmental and social responsibility. The issuance of green bonds expands the financial capabilities of business entities and strengthens their reputational positions in international markets.

The results of the econometric modeling revealed stable relationships between the dynamics of green bond issuance and the development of renewable energy. The study established that all types of alternative energy production exhibit a memory effect and depend on their own lagged values. The degree of influence of total and solar energy production on green bond issuance was found to increase over time.

In this study, Hypothesis H1 regarding the relationship between the dynamics of green bond issuance and the renewable energy market was statistically confirmed. Hypothesis H2 concerning the causal impact of green bonds on renewable energy development was not supported by the results. Meanwhile, Hypothesis H3 proposing a significant influence of the renewable energy market on green bond issuance volumes received statistical confirmation based on VAR modeling results.

Thus, the present study and the works of leading scholars once again confirm that modern financial markets are increasingly shaping energy and environmental transformation. The strategic role of “green” financial markets lies in providing the institutional and resource foundations for the transition toward low-carbon economic models. Future research should focus on assessing the effectiveness of green financial instruments in different national contexts and deepening the analysis of the impact of green investments on the dynamics of renewable energy development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B. methodology, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; analysis and selection of sources and the literature, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; consultations on material and technical issues, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; literature review, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; writing—original draft K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; writing—review and editing, K.P., O.P., T.W., K.C., Y.V., T.V., O.M. and P.B.; supervision, K.P., O.P. and T.W.; funding acquisition, T.W., K.C., P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

his work was supported by a subsidy from the Ministry of Education and Science for the WSEI (Project No. 8/121/226upf).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grishunin, S.; Bukreeva, A.; Suloeva, S.; Burova, E. Analysis of Yields and Their Determinants in the European Corporate Green Bond Market. Risks 2023, 11(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiuwen, W.; Hu, Z.; Jiabei, H.; Pengfei, Z. The Use of Alternative Fuels for Maritime Decarbonization: Special Marine Environmental Risks and Solutions from an International Law Perspective. Frontiers in Marine Science 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semieniuk, G.; Campiglio, E.; Mercure, J.F.; Volz, U.; Edwards, N.R. Low-Carbon Transition Risks for Finance. WIREs Climate Change 2021, 12(1), e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Delivering the European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en.

- Demski, J.; Dong, Y.; McGuire, P.; Mojon, B. Growth of the Green Bond Market and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. BIS Quarterly Review 2025, 19. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2503d.pdf.

- Domanski, D.; Howaldt, J.; Kaletka, C. A Comprehensive Concept of Social Innovation and Its Implications for the Local Context: On the Growing Importance of Social Innovation Ecosystems and Infrastructures. European Planning Studies 2019, 28(3), 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, U.S.; Tariq, A.; Farrukh, M.; Raza, A.; Iqbal, M.K. Green Bonds for Sustainable Development: Review of Literature on Development and Impact of Green Bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 175, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitrem, A.; Meidell, A.; Modell, S. The Use of Institutional Theory in Social and Environmental Accounting Research: A Critical Review. Accounting and Business Research 2024, 54(7), 775–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleli, B.; Amaral, L. Bridging Institutional Theory and Social and Environmental Efforts in Management: A Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Management 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Qin, C.; Ding, L.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Vătavu, S. Can Green Bonds Improve the Investment Efficiency of Renewable Energy? Energy Economics 2023, 127(B), 107084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Kythreotis, A. Why Issue Green Bonds? Examining Their Dual Impact on Environmental Protection and Economic Benefits. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flottmann, C.; Köchling, G.; Neukirchen, D.; et al. Green Debt: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Management Review 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortellini, G.; Panetta, I.C. Green Bond: A Systematic Literature Review for Future Research Agendas. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2021, 14, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Murodova, G.; Khan, A. Achieving Zero Emission Targets: The Influence of Green Bonds on Clean Energy Investment and Environmental Quality. Journal of Environmental Management 2024, 364, 121485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, S.S.; Mamun, M.A.; Boubaker, S.; Rizvi, S.K.A. Green Finance and Renewable Energy: Worldwide Evidence. Energy Economics 2023, 118, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Hoque, A.; Le, T. Dynamic Spillovers Among Green Bond Markets: The Impact of Investor Sentiment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2025, 18(8), 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Gautam, D.; Natalucci, F.M. Sustainable Finance in Emerging Markets: Evolution, Challenges, and Policy Priorities. IMF Working Papers 2022, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Chadha, G.; Prasad, R. Sustainable Finance Research: Review and Agenda. International Journal of Finance & Economics 2024, 29(4), 4010–4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giglio, S.; Kelly, B.; Stroebel, J. Climate Finance. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2021, 13, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, S.; Simen, C.W.; Vivian, A. Sustainable Finance and Governance: An Overview. The European Journal of Finance 2023, 30(7), 669–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Schaltegger, S.; Freeman, R.E. Integrating Stakeholder Theory and Sustainability Accounting: A Conceptual Synthesis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 275, 124097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, R.; Benítez, R.; Bolós, V.J. Interdependence Between Green Financial Instruments and Major Conventional Assets: A Wavelet-Based Network Analysis. Mathematics 2021, 9(8), 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.P.; Ashok, S.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Dhingra, D.; Mishra, N.; Malhotra, N. Uncovering Time and Frequency Co-Movement Among Green Bonds, Energy Commodities and Stock Market. Studies in Economics and Finance 2024, 41(3), 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Rodríguez, N.J.; González-Ruiz, J.D.; Botero, S. Dynamic Relationships Among Green Bonds, CO₂ Emissions, and Oil Prices. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chygryn, O.Yu.; Pimonenko, T.V.; Liulov, O.V.; Honcharova, A.V. Green Bonds Like the Incentive Instrument for Cleaner Production at the Government and Corporate Levels: Experience from EU to Ukraine. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism 2019, 9(7), 1443–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Umair, M.; Hu, J. Green Finance and Renewable Energy Growth in Developing Nations: A GMM Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10(13), e33879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, D.; Gong, J.; Sheehan, B. Information Leakages in the Green Bond Market. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, A. Project Evaluation and Selection System for the Green Bonds Market. Finance of Ukraine 2024, 11, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, M. The EU Green Bond Standard: A Plausible Response to the Deficiencies of the EU Green Bond Market? European Business Organization Law Review 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iris, H.Y.C. Regulating Sustainable Finance in Capital Markets: A Perspective from Socially Embedded Decentered Regulation. Law and Contemporary Problems 2021, 75(1), 75–93. Available online: https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4986&context=lcp.

- Sun, X.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. The Role of Institutional Quality in the Nexus Between Green Financing and Sustainable Development. Research in International Business and Finance 2025, 73(A), 102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellard, N.M.; Kontonikas, A.; Lamla, M.J.; Maiani, S.; Wood, G. Institutional Settings and Financing Green Innovation. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 2023, 89, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, L. EIB Policy Entrepreneurship and the EU’s Regulation of Green Bonds. Journal of Economic Policy Reform 2024, 28(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Green Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 2021, 142(2), 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholudko, O.; Hrytsyna, O.; Rubai, O. Theoretical Foundations of Green Finance Instruments Application. Agrarian Economy 2024, 17, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Han, L.; Wu, L.; Zeng, H. The Hedging Effect of Green Bonds on Carbon Market Risk. International Review of Financial Analysis 2020, 71, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y. Examining the Interplay of Green Bonds and Fossil Fuel Markets: The Influence of Investor Sentiments. Resources Policy 2023, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Bolton, P.; Samama, F. Hedging Climate Risk. Financial Analysts Journal 2016, 72(3), 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Nguyen, A. Weathered for Climate Risk: A Bond Investment Proposition. Financial Analysts Journal 2016, 72(3), 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, D.; Balli, F.; Hoxha, I. Market Reaction to Macroeconomic Announcements: Green vs. Conventional Bonds. Applied Economics 2022, 55(15), 1637–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Lyu, M.; Ying, Y. How to Explore the Potential of Green Bonds? Based on the Propensity Score Matching Method. Open Journal of Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.Y.; Zhang, Y. Do Shareholders Benefit from Green Bonds? Journal of Corporate Finance 2020, 61, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, S.; Chiesa, M. Sustainable Financing Practices Through Green Bonds: What Affects the Funding Size? Business Strategy and the Environment 2019, 28(6), 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebelle, M.; Lajili Jarjir, S.; Sassi, S. Corporate Green Bond Issuances: An International Evidence. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2020, 13(2), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Bergstresser, D.; Serafeim, G.; Wurgler, J. The Pricing and Ownership of US Green Bonds. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2022, 14, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshipura, M.; Mathur, S.; Joshipura, N.; Castelino, R. Decoding Green Bonds for Sustainable Development: A Hybrid Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Economic Studies 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajo, M.; Rodríguez, E. Green Parity and the Decarbonization of Corporate Bond Portfolios. Financial Analysts Journal 2023, 79(4), 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimonenko, T. A Conceptual Framework for Development of Ukraine’s Green Stock Market. Herald of Economics 2019, 4(90), 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, S.; Ajmi, A.N.; Mokni, K. Relationship Between Green Bonds and Financial and Environmental Variables: A Novel Time-Varying Causality. Energy Economics 2020, 92, 104941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com.

- Elliott, G.; Rothenberg, T.J.; Stock, J.H. Efficient Tests for an Autoregressive Unit Root. Econometrica 1996, 64(4), 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, J.H.; Watson, M.W. Vector Autoregressions. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2001, 15(4), 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, D.; Bashynska, I.; Pavlova, O.; Pavlov, K.; Chorna, N.; Chornyi, R. Investment and Innovation Activity of Renewable Energy Sources in the Electric Power Industry in the South-Eastern Region of Ukraine. Energies 2023, 16(5), 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, D.; Pavlov, K.; Pavlova, O.; Dychkovskyi, R.; Ruskykh, V.; Pysanko, S. Determining the Level of Efficiency of Gas Distribution Enterprises in the Western Region of Ukraine. Inżynieria Mineralna 2023, 2(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).