1. Introduction

The increasing digitalization of healthcare has led to an unprecedented accumulation of multimodal medical data, including imaging, clinical records, physiological signals, and genomics [

1,

2,

3,

4]. These data provide vast opportunities for artificial intelligence (AI) to improve diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment planning. However, the effectiveness of AI systems in healthcare remains constrained by the scarcity of annotated datasets and the high cost of expert labeling. Medical annotation often requires domain specialists and is subject to inter-observer variability, making the implementation of large-scale supervised learning difficult [

5,

6,

7]. This has stimulated the growing adoption of self-supervised learning (SSL) approaches, which exploit large volumes of unlabeled data to learn meaningful representations that can generalize across downstream tasks with minimal supervision.

Contrastive learning (CL) has become one of the most prominent paradigms within SSL. It operates by comparing data pairs to bring similar instances closer in representation space while pushing dissimilar ones apart [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Unlike traditional supervised methods, CL relies on instance discrimination and data augmentations to build robust representations without requiring human annotations. Early approaches such as SimCLR, MoCo, BYOL, and SwAV demonstrated the potential of CL in computer vision and natural language processing, showing that high-quality features can be learned directly from unlabeled data [

12,

13,

14]. Consequently, these methods have been extended to medical domains, where data scarcity and heterogeneity remain pressing challenges. The ability of CL to learn invariant and transferable features makes it particularly suitable for applications in medical imaging, electronic health records (EHRs), and multi-omics analysis.

Several recent reviews have examined self-supervised and contrastive learning, though their coverage of medical applications remains limited. Jaiswal et al. [

15] provided an early survey outlining theoretical principles and algorithmic variants but did not address domain-specific adaptations for medical data. Gui et al. [

16] extended this scope to include generative and clustering-based self-supervised methods, yet the discussion of healthcare contexts was minimal. More focused surveys such as Wang et al. [

17] and Shurrab et al. [

18] explored medical imaging tasks but lacked analysis across multimodal and clinical data sources.

While informative, these studies have common limitations: they often restrict attention to a single modality (typically imaging), overlook a structured taxonomy of contrastive frameworks, and provide limited discussion on evaluation, robustness, or cross-domain generalization. To address these gaps, this paper provides a comprehensive review of contrastive learning in medical AI, covering its theoretical foundations, methodological advances, and practical applications across diverse medical data modalities. The specific contributions of this study are as follows:

A domain-aware taxonomy of contrastive learning methods is proposed, detailing their key components, loss functions, and adaptation strategies for medical data.

A unified analysis of contrastive learning applications across medical imaging, electronic health records, genomics, and multimodal systems is presented, highlighting cross-domain similarities and differences.

The challenges of evaluation, robustness, and generalization in medical contrastive learning are critically examined, with insights into reproducibility and transferability.

Practical guidelines and future research directions are discussed, focusing on interpretability, fairness, and integration with federated and causal learning frameworks.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 3 reviews the foundations of contrastive learning;

Section 3 surveys applications across medical imaging, EHRs, genomics, and physiological signals;

Section 4 examines challenges and limitations;

Section 5 discusses future research directions;

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Methodology

This review adopts a structured search strategy to comprehensively capture the breadth of contrastive learning applications in medical AI. Eligible studies were required to (i) use contrastive learning or closely related self-supervised objectives and (ii) involve medical or biomedical data, including medical images, electronic health records, physiological signals, and -omics modalities.

2.1. Databases and Search Strategy

We conducted a literature search across the following electronic databases: PubMed, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Web of Science, Scopus, and arXiv. The search covered publications from January 2019 to October 2025, corresponding to the period during which contrastive learning matured into a widely adopted paradigm in machine learning and began to be systematically explored in medical domains.

Search queries combined terms related to contrastive and self-supervised learning with domain-specific medical keywords. Representative examples include:

("contrastive learning" OR "self-supervised") AND (medical OR healthcare OR clinical)

("contrastive learning" OR SimCLR OR MoCo OR BYOL) AND (radiology OR "chest x-ray" OR MRI OR CT)

("contrastive learning" OR "self-supervised") AND ("electronic health record" OR EHR OR "clinical notes")

("contrastive learning" OR "representation learning") AND (ECG OR EEG OR "physiological signals")

("contrastive learning" OR "self-supervised") AND (genomics OR proteomics OR "single-cell")

Search strings were adapted to the syntax and indexing conventions of each database. In addition, backward and forward citation chasing (snowballing) was performed on key papers to identify relevant studies not captured by the initial queries.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

Peer-reviewed journal articles or full-length conference papers, with a small number of influential preprints included when they introduced widely adopted methods or benchmarks.

Work that explicitly employs contrastive, self-supervised, or closely related representation-learning objectives (e.g., InfoNCE, supervised contrastive loss, MoCo, SimCLR, BYOL- or CLIP-style frameworks).

Applications involving medical, clinical, or biomedical data (e.g., medical imaging, EHRs, physiological time series, genomics, proteomics, or pathology).

Preprints were included selectively when they introduced methods or benchmarks that have been widely adopted or cited in subsequent peer-reviewed literature.

We excluded:

Studies that use contrastive objectives solely for non-medical domains (e.g., natural images, generic NLP) without any medical or biomedical application.

Short abstracts, workshop posters without sufficient methodological detail, editorials, commentaries, and theses.

Non–peer-reviewed technical reports and preprints that did not provide experimental validation or that were superseded by later peer-reviewed versions.

When multiple papers described incremental versions of the same method, we prioritized the most comprehensive or recent publication and referenced earlier versions as needed for historical context.

2.3. Screening and Synthesis

Data extraction was performed using a standardized template and cross-checked for consistency across studies. Titles and abstracts were screened to remove clearly irrelevant works, followed by full-text assessment against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. For each included study, we extracted information on:

Data modality (e.g., imaging, EHRs, physiological signals, genomics/pathology).

Contrastive learning formulation (e.g., unsupervised, supervised, multimodal, temporal or patient-level objectives).

Architectural choices (e.g., CNNs, Transformers, multimodal encoders).

Downstream tasks and evaluation metrics (e.g., classification, segmentation, retrieval, risk prediction).

These studies were then grouped into thematic domains, including medical imaging, EHRs, genomics and proteomics, multimodal and cross-domain learning, and time-series/physiological signals, which structure the survey, as presented in

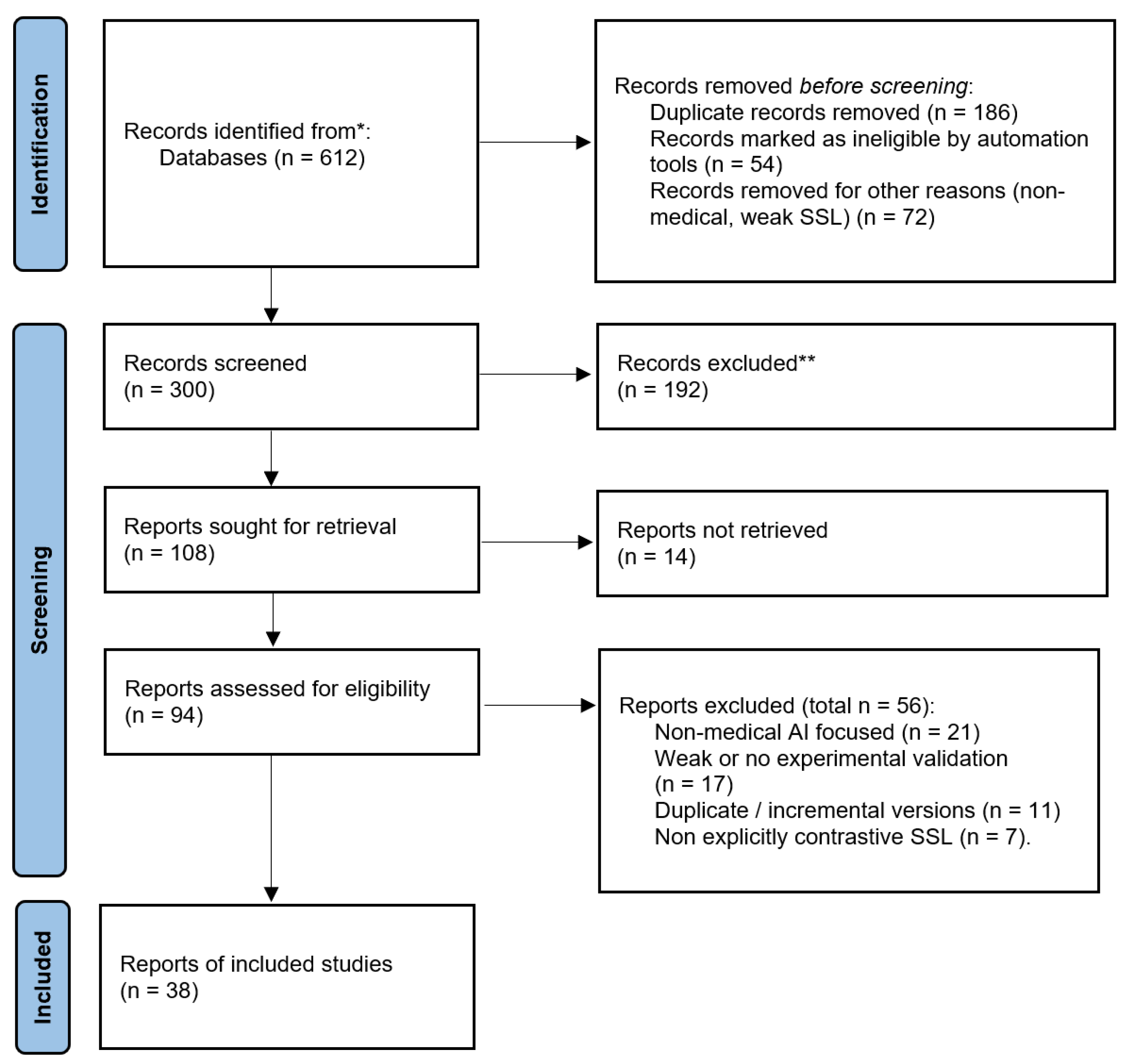

Section 4. Of 612 identified records, 300 were screened after duplicate and automation-based exclusions. Following the full-text assessment of 94 reports, 38 studies were included in the final review. A PRISMA-style flow summary of the selection process is shown in

Figure 1.

2.4. Protocol Registration

No protocol was preregistered for this review, consistent with common practice for exploratory evidence mapping and structured narrative reviews.

3. Overview of Contrastive Learning

Contrastive learning is a self-supervised learning technique designed to learn effective representations from unlabeled data by distinguishing between positive and negative pairs [

11,

19,

20]. Unlike traditional supervised learning, which heavily depends on labeled data to guide the learning process, contrastive learning utilizes the intrinsic structure of the data to derive semantically meaningful representations [

15,

16,

21]. This makes it especially effective in situations where labeled data is limited or difficult to obtain. The concept of contrastive learning originated from the broader field of self-supervised learning, a paradigm that has seen increasing interest due to its ability to leverage vast amounts of unlabeled data. The early developments of contrastive learning date back to the 1990s with the introduction of metric learning and Siamese networks, which were designed to learn similarity metrics between pairs of data points [

22]. These early forms laid the groundwork for the evolution of contrastive learning into a robust tool for modern machine learning applications.

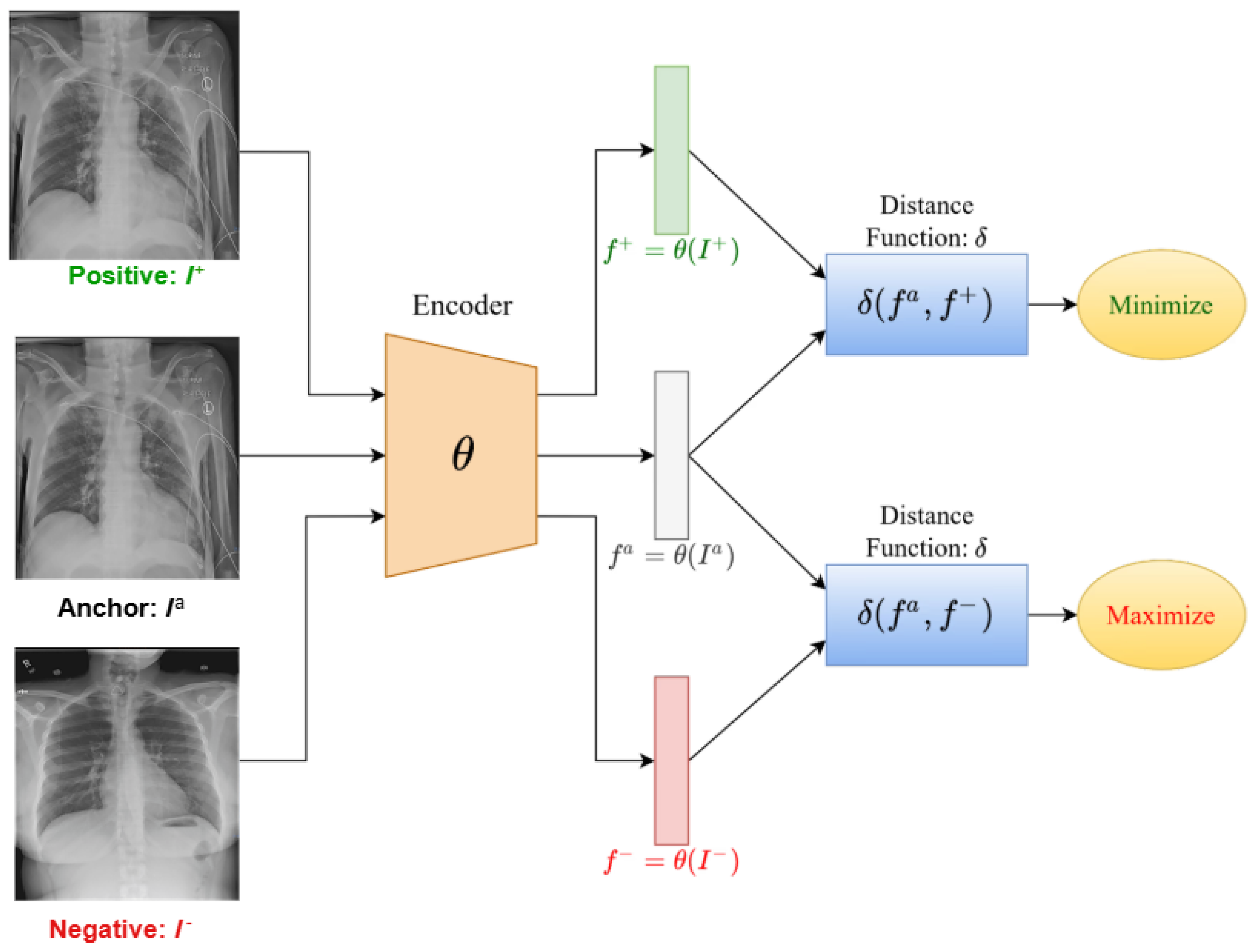

Figure 2 illustrates the general workflow of contrastive learning, in which an encoder parameterized by

maps an anchor, a positive, and a negative example into a shared embedding space. The goal is to maximize similarity between the anchor and positive pair while minimizing similarity to the negative.

Originally introduced for verification tasks using Siamese networks, contrastive objectives gained traction through contrastive predictive coding (CPC) and frameworks such as SimCLR and MoCo, which demonstrated that high-quality representations could be learned from unlabeled data at scale [

15,

24]. These advances catalyzed rapid adoption across fields including medical imaging, text analysis, and multimodal learning [

25,

26].

Furthermore, the theoretical foundations of contrastive learning are rooted in the idea of representation learning through similarity and dissimilarity. The main goal is to learn a function

that maps input data points to a representation space where semantically similar inputs are closer together, while semantically dissimilar inputs are further apart [

16]. This is operationalized through a contrastive loss function, commonly referred to as Noise Contrastive Estimation (InfoNCE) loss. The InfoNCE loss is defined as:

where

and

are the embeddings of the anchor and the positive sample,

denotes the similarity between two embeddings, typically calculated using cosine similarity:

,

is a temperature parameter that regulates the sharpness of the similarity distribution, and the denominator sums over all

K samples in the dataset, encompassing both positive and negative pairs.

This loss function seeks to maximize the similarity between the embeddings of positive pairs while minimizing the similarity between the anchor and negative samples [

27,

28]. The efficacy of contrastive learning is determined by several key factors. The selection of positive and negative pairs is critical, as it directly influences the quality of the learned representations. For instance, utilizing multiple views or augmentations of the same data point as positive pairs can help the model learn invariances to specific transformations [

29]. Additionally, the use of larger batch sizes or memory banks can provide the model with a richer set of negative samples, enhancing the learning process. The choice of data augmentation strategies is also vital, as it determines the types of invariances the model will learn.

3.1. Variants and Extensions of Contrastive Learning

To address various challenges and improve performance, several variants of contrastive learning have been developed:

3.1.1. Supervised Contrastive Learning

Supervised Contrastive Learning extends contrastive learning to a supervised framework by leveraging label information during training. In this setting, all samples within the same class are treated as positives, while samples from different classes are considered negatives. This approach enhances representation quality in downstream classification tasks by ensuring that intra-class representations are closely aligned, and inter-class representations are well-separated [

19,

30]. The supervised contrastive loss function can be formulated as follows:

where

and

are the embeddings of the anchor sample and a positive sample from the same class, respectively.

denotes the set of all positives for anchor

i, and

is the set of all samples excluding

i. The similarity between embeddings

and

is represented by

, which is typically computed using cosine similarity:

. Finally,

is a temperature scaling parameter that controls the sharpness of the similarity distribution [

31]. This loss function encourages all samples of the same class to be clustered together in the embedding space, enhancing the discriminative power of the learned representations.

3.1.2. Self-Distillation with No Labels

Self-Distillation with No Labels, abbreviated as DINO, employs a teacher-student framework without the need for labeled data. In this method, the student network is trained to match the output distribution of the teacher network. This setup generates an implicit contrastive signal by aligning the student’s output with the teacher’s prediction. To ensure stability and consistency in the learning process, the teacher network’s parameters are typically updated through an exponential moving average of the student network’s parameters [

32,

33]. The loss function for DINO can be formulated as a cross-entropy loss between the output distributions of the teacher and student networks:

where

and

are the probability distributions predicted by the teacher and student networks for input

x [

33]. This approach provides a self-supervised signal, guiding the student network to learn from the teacher without the need for explicit labels.

3.1.3. Momentum Contrast

Momentum Contrast (MoCo), introduces a dynamic memory bank to store a large set of negative samples, which enables the efficient computation of contrastive loss over extensive datasets. The key innovation in MoCo is the use of a momentum encoder that updates more slowly than the main encoder. This helps maintain a consistent set of negative samples over time, contributing to more stable and efficient training dynamics, particularly in scenarios involving large datasets [

34]. The MoCo loss function is defined similarly to the InfoNCE loss but incorporates a momentum encoder:

where

q is the query embedding from the current batch,

is the key embedding of the positive sample,

are the embeddings of negative samples stored in the memory bank, and

is the temperature parameter [

34]. By maintaining a queue of negative samples and using a slowly updated encoder, MoCo effectively improves the model’s ability to learn discriminative features.

3.1.4. Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations

The Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations (SimCLR) simplifies the contrastive learning approach by using large batch sizes and extensive data augmentations to create a diverse set of positive pairs. The main goal of SimCLR is to maximize the agreement between differently augmented views of the same image in the latent space, using a contrastive loss that is similar to the InfoNCE loss [

35]. The SimCLR loss function is expressed as:

where

and

are embeddings of two different augmentations of the same image,

N represents the batch size,

is an indicator function that equals 1 if

and 0 otherwise, and

is the temperature parameter [

35]. SimCLR’s effectiveness is derived from its straightforward design and the use of extensive data augmentations, which provide diverse and meaningful variations that facilitate the learning of robust representations.

4. Applications of Contrastive Learning in Medical AI

Contrastive learning has shown significant promise in the field of medical AI due to its ability to learn effective representations from limited or unlabeled data. This capability is particularly valuable in medical contexts, where labeled data can be scarce or expensive to obtain.

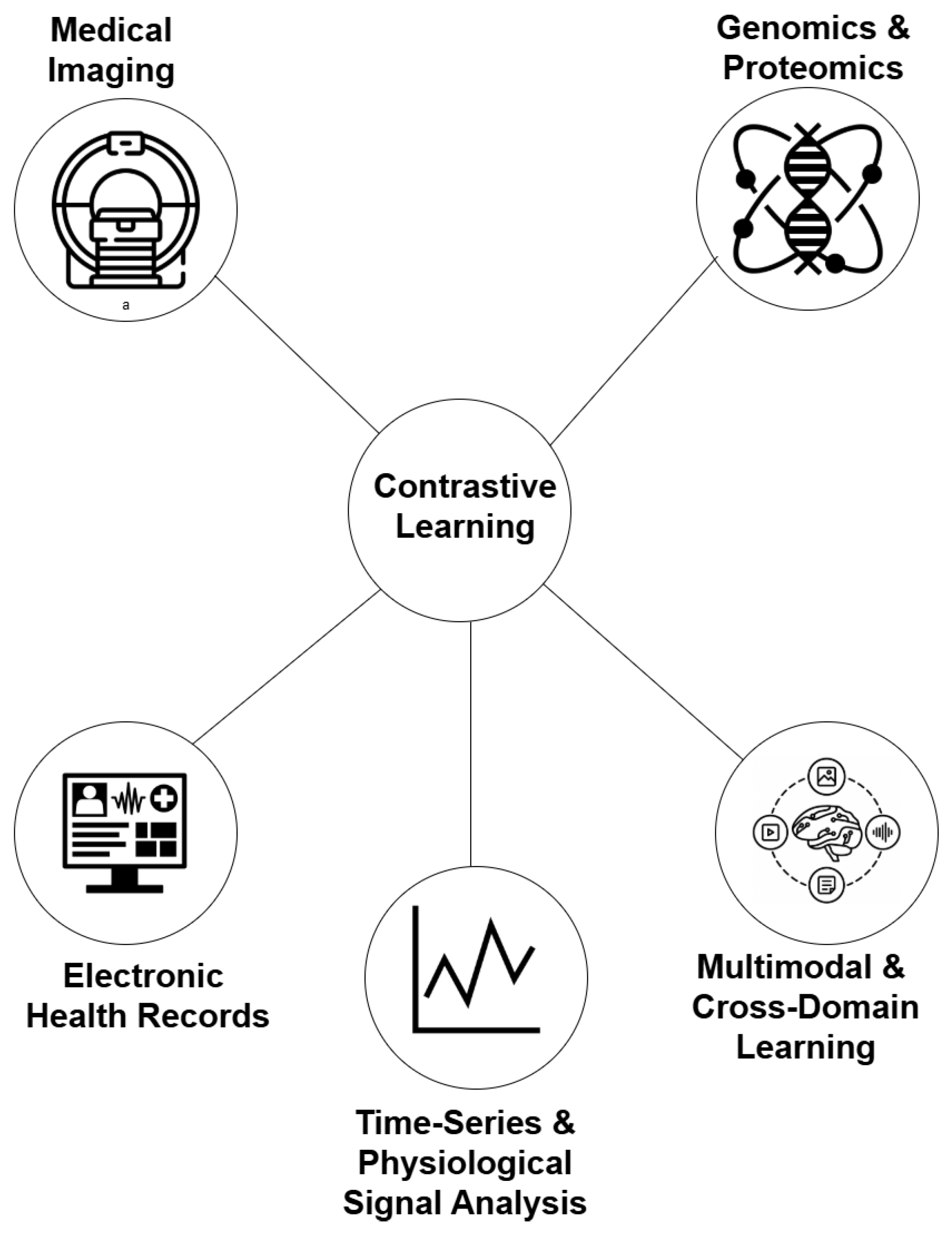

Figure 3 presents an overview of contrastive learning applications in healthcare and biomedicine. The following subsections explore the applications of contrastive learning across various domains within medical AI.

4.1. Medical Imaging

Medical imaging is one of the most prominent areas where contrastive learning has been applied successfully. In this domain, the challenge often lies in the need for large, annotated datasets to train robust machine learning models. Contrastive learning addresses this challenge by leveraging unlabeled data to learn rich feature representations that are invariant to certain transformations, such as rotation or scaling. For example, Azizi et al. [

36] applied contrastive learning to medical imaging tasks such as classification and segmentation by using a framework that learns representations from unlabeled medical images. They utilized SimCLR, a popular contrastive learning method, to pre-train a model on a large dataset of unlabeled chest X-rays, which was then fine-tuned on a smaller labeled dataset for specific tasks. Their study demonstrated significant improvements in performance compared to models trained from scratch, highlighting the utility of contrastive learning for medical imaging applications with limited labeled data.

In another study, Chaitanya et al. [

37] developed a contrastive learning approach for semi-supervised learning in medical imaging. Their method was designed to handle the lack of annotations in medical images by learning representations that are robust across different anatomical structures and imaging modalities. By training their model on augmented views of the same image as positive pairs and different images as negative pairs, they showed improved performance in both segmentation and classification tasks on MRI scans.

Contrastive learning has also been applied in histopathology to improve the detection of cancerous cells in biopsy samples. Ciga et al. [

38] explored self-supervised contrastive learning to analyze histopathological images, demonstrating that the learned representations could effectively differentiate between different tissue types and detect malignancies with higher accuracy than traditional supervised methods. By maximizing the agreement between different augmented views of the same image, their approach captured the intricate patterns in histopathological images that are critical for accurate diagnosis.

More recently, Guo et al. [

39] proposed a novel contrastive learning framework specifically designed for the task of cardiac MRI segmentation. Their approach leverages a multi-scale contrastive loss that enables the model to learn representations at different spatial resolutions, which is particularly beneficial for capturing both global anatomical structures and local pathological features. The study demonstrated that by incorporating contrastive learning into their segmentation model, they were able to significantly improve the segmentation accuracy of various cardiac structures, such as the myocardium and ventricles, compared to traditional supervised methods. This highlights the potential of contrastive learning in enhancing the robustness and generalizability of models across different imaging modalities and patient populations.

In addition to segmentation tasks, contrastive learning has also been applied to anomaly detection in medical imaging. Luo et al. [

40] developed a self-supervised contrastive learning model for detecting anomalies in brain MRI scans. Their model was trained to distinguish between normal and abnormal patches within the same scan by treating them as negative pairs, while different augmentations of the same patch were treated as positive pairs. This approach allowed the model to learn features that are particularly sensitive to anomalies, thereby improving its ability to detect subtle pathological changes that might be missed by conventional supervised models. The study found that their contrastive learning approach outperformed existing anomaly detection methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in identifying early signs of neurological disorders.

4.2. Electronic Health Records

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) represent another significant application area for contrastive learning in medical AI. EHR data is complex and heterogeneous, containing information from various sources such as clinical notes, laboratory results, and medication records. The challenge with EHR data lies in its high dimensionality and the presence of both structured and unstructured data, making it difficult to develop models that generalize well. Krishnan et al. [

41] applied contrastive learning to EHR data by developing a self-supervised learning framework. This method uses contrastive learning to generate augmented views of EHRs, treating each augmented view of the same patient’s records as positive pairs and different patients’ records as negative pairs. This approach helps capture temporal patterns and correlations within a patient’s data, which are crucial for predicting outcomes or recommending treatments. Their experiments showed that the proposed model outperformed traditional supervised methods on multiple predictive tasks, including mortality prediction and heart failure diagnosis.

Another study by Pick et al. [

42] introduced a contrastive learning approach for learning representations of patients from EHR data to predict hospital mortality and length-of-stay. The method uses contrastive learning to differentiate between similar and dissimilar patient records. By constructing patient representations through contrastive learning, the model improved the accuracy of risk prediction models for various diseases, demonstrating the effectiveness of contrastive learning in handling the complexities of EHR data.

Sun et al. [

43] developed a contrastive learning framework tailored for multi-modal EHR data integration. Their approach leverages contrastive learning to align and integrate structured data, such as lab results and vital signs, with unstructured clinical notes. The model creates positive pairs by associating structured and unstructured data from the same patient, while negative pairs are formed from data across different patients. This method significantly improved the model’s ability to generate comprehensive patient representations, leading to enhanced performance in tasks like predicting disease progression and identifying patients at risk of complications. The study demonstrated that contrastive learning could effectively bridge the gap between different data modalities within EHRs, facilitating more accurate and holistic patient care predictions.

Furthermore, a study by Cai et al. [

44] focused on scaling contrastive learning for large-scale EHR datasets. They developed a distributed contrastive learning framework that could handle the massive size and complexity of EHRs in real-world settings. The study highlights the scalability of contrastive learning methods and their applicability to big data scenarios in healthcare, offering a viable solution for integrating and analyzing large-scale EHR data across diverse patient populations.

4.3. Genomics and Proteomics

In the fields of genomics and proteomics, contrastive learning offers significant advantages in analyzing high-dimensional biological data. These domains deal with vast amounts of data generated from sequencing technologies, where the objective is to identify patterns associated with genetic variations, disease susceptibility, or protein functions. A recent study by Zhong et al. [

45] applied contrastive learning to genomic data to identify genetic markers associated with disease. Their approach, multi-scale contrastive learning (MSCL), was designed to capture genetic interactions at different scales, from individual genes to entire pathways. By treating sequences from the same genomic regions as positive pairs and sequences from different regions as negative pairs, MSCL could learn representations that effectively differentiate between healthy and diseased samples, enhancing the detection of genetic markers.

In proteomics, Bepler and Berger [

46] used contrastive learning to learn representations of protein sequences that reflect their functional similarities. Their method involved creating positive pairs from different conformations or states of the same protein and negative pairs from unrelated proteins. By training their model with this contrastive setup, the predictive accuracy of protein function and interaction models was improved, which has important implications for drug discovery and development.

A study by Liu et al. [

47] advanced the use of contrastive learning in genomics by developing a framework called MoHeG , which focuses on the integration of multi-omics data. By leveraging contrastive learning, GenCL aligns different types of omics data, such as genomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics, to create a unified representation of a patient’s molecular profile. The model was able to identify complex interactions between genes and regulatory elements, leading to better predictions of disease susceptibility and personalized treatment outcomes. This approach significantly enhances the interpretability and predictive power of genomic studies, particularly in understanding multifactorial diseases like cancer.

In another innovative application, Li et al. [

48] applied contrastive learning to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, a cutting-edge area in genomics that examines gene expression at the single-cell level. Their contrastive learning framework was designed to handle the sparsity and noise inherent in scRNA-seq data by creating contrastive pairs between cells that share similar expression patterns and those that do not. This method allowed for more accurate clustering of cell types and identification of rare cell populations, which are critical for understanding cellular heterogeneity in complex tissues and diseases such as cancer and neurodegenerative disorders.

In the field of proteomics, a study by Zhang et al. [

49] explored the application of contrastive learning to predict protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Their method, named Pepharmony, utilized contrastive learning to enhance the feature representations of proteins by considering both their sequence and structural information. Positive pairs were formed by different conformations of interacting protein pairs, while non-interacting protein sequences formed negative pairs. The model demonstrated improved accuracy in predicting PPIs, which is vital for understanding the molecular mechanisms of diseases and discovering new therapeutic targets.

4.4. Multimodal and Cross-Domain Learning

Integrating heterogeneous medical modalities such as images, clinical text, and structured patient data has become a major direction in medical AI. Contrastive learning provides a natural mechanism for aligning such diverse data sources by mapping them into a shared embedding space. Zhang et al. [

50] introduced ConVIRT, which learns visual representations by aligning chest X-rays with paired radiology reports using a bidirectional contrastive objective. Their experiments showed that the model required only 10% of the labeled data compared to an ImageNet-initialized baseline to achieve similar or better classification performance across four downstream tasks, demonstrating substantial label efficiency. Huang et al. [

51] proposed GLoRIA, which performs both global and local alignment between images and text phrases. On the MIMIC-CXR dataset, GLoRIA achieved a precision@5 of 69.24% for image-to-text retrieval compared to 66.98% for ConVIRT and attained CheXpert AUROC scores of 0.926, 0.943, and 0.950 when fine-tuned with 1%, 10%, and 100% labeled data, respectively. Boecking et al. [

52] presented BioViL, which enhances text semantics using domain-specific language pretraining. BioViL achieved zero-shot accuracy, F1, and AUROC of 0.732, 0.665, and 0.831, respectively, and linear-probe AUROC up to 0.891 on RSNA pneumonia classification, establishing a strong benchmark for biomedical vision–language processing.

Bannur et al. [

53] extended this approach with BioViL-T, incorporating temporal alignment across prior and current chest X-rays. The model demonstrated improved performance on progression classification, phrase grounding, and report generation tasks, emphasizing the value of temporal contrastive structure. Similarly, You et al. [

54] developed CXR-CLIP, which integrates radiologist-defined class prompts with image–label and image–text supervision to enhance chest X-ray recognition. These works show that incorporating temporal, semantic, and supervised priors into contrastive frameworks improves clinical interpretability and downstream task robustness.

Contrastive models have also enabled zero-shot transfer through large-scale vision–language alignment. Tiu et al. [

55] introduced CheXzero, a CLIP-based model trained on unannotated chest X-rays and reports. In a reader study, CheXzero achieved multi-label classification performance statistically indistinguishable from board-certified radiologists on the CheXpert benchmark, with no significant difference in Matthews correlation coefficient across five evaluated pathologies. Wang et al. [

56] proposed MedCLIP to address data scarcity and false negatives by decoupling image and text corpora and applying a knowledge-aware matching loss. Using only 20,000 pretraining pairs, MedCLIP achieved a zero-shot accuracy of 44.8%, surpassing GLoRIA (43.3% with 191,000 pairs) and ConVIRT (42.2% with 369,000 pairs) under identical evaluation settings.

Beyond radiology, multimodal contrastive learning has advanced computational pathology and cross-domain generalization. Huang et al. [

57] proposed PLIP, a vision–language foundation model for pathology trained on OpenPath image–caption pairs. PLIP achieved zero-shot F1 scores between 0.565 and 0.832 across four external datasets, outperforming prior vision–language models that scored between 0.030 and 0.481. Lu et al. [

58] introduced CONCH, trained on over 1.17 million histopathology image–caption pairs, achieving state-of-the-art results across classification, retrieval, captioning, and segmentation tasks, demonstrating that scaling contrastive pretraining enhances transferability in pathology.

Extending to large biomedical corpora, Zhang et al. [

59] developed BiomedCLIP, a foundation model pretrained on 15 million image–text pairs from PubMed Central. BiomedCLIP achieved 56% and 77% top-1 and top-5 retrieval accuracy on a 725,000-pair held-out set and demonstrated strong zero- and few-shot results across radiology and pathology benchmarks, often surpassing domain-specific models such as ConVIRT and GLoRIA. Similarly, Lin et al. [

60] proposed PMC-CLIP, pretrained on 1.6 million biomedical figure–caption pairs, which improved performance on medical visual question answering and retrieval tasks, highlighting the value of literature-derived multimodal alignment when clinical pairings are scarce.

Recent innovations have also focused on improving fine-grained alignment and extending contrastive methods to segmentation. Huang et al. [

61] introduced MaCo, which applies masked contrastive learning with correlation weighting to chest X-rays, improving zero-shot and supervised recognition of localized findings. Koleilat et al. [

62] combined contrastive vision–language models with the Segment Anything Model to enable text-driven segmentation across ultrasound, MRI, and CT datasets, achieving high accuracy without explicit segmentation labels. These developments illustrate the growing versatility of multimodal and cross-domain contrastive learning, enabling efficient, interpretable, and transferable medical AI models that bridge visual and textual information.

4.5. Time-Series and Physiological Signal Analysis

Medical time-series data, such as ECG, EEG, respiratory signals, and vital signs, present both opportunities and challenges for contrastive learning. These datasets offer abundant unlabeled recordings but are often characterized by temporal dependencies, noise, and inter-patient variability. A systematic review by Liu et al. [

63] covering 43 studies on self-supervised contrastive learning for medical time series reported that most approaches rely on standard augmentations (scaling, jittering, cropping) and encoder architectures such as 1D CNNs or Transformers. The review also highlighted the need for hierarchical and patient-aware contrastive frameworks to capture long-range dependencies and temporal consistency in physiological signals.

Diamant et al. [

64] introduced Patient Contrastive Learning of Representations (PCLR), which defines positive pairs as ECG recordings from the same patient and negatives from different patients. Using a dataset of more than 3.2 million 12-lead ECGs, their results showed that linear models built on PCLR representations achieved an average 51% improvement across multiple downstream tasks, including sex classification, age regression, left ventricular hypertrophy, and atrial fibrillation detection, compared to models trained from scratch. When compared to other pretraining approaches, PCLR achieved a 47% average gain on three of four tasks and a 9% benefit over the best baseline per task.

Yuan et al. [

65] proposed poly-window contrastive learning, which samples multiple overlapping temporal windows from each ECG as positive pairs instead of using only two augmented views. On the PTB-XL dataset, this approach achieved AUROC 0.891 compared to 0.888 for conventional two-view contrastive learning, and F1-score 0.680 versus 0.679, while reducing pretraining time by 14.8%. These findings indicate that modeling intra-record temporal relationships can enhance both efficiency and representational performance.

Wang et al. [

66] developed COMET, a hierarchical contrastive learning framework that organizes data at multiple levels—observation, sample, trial, and patient—and applies contrastive objectives across these granularities. COMET demonstrated improved performance over six baselines in ECG and EEG datasets addressing myocardial infarction, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease tasks, particularly in low-label (10% and 1%) settings. Chen et al. [

67] introduced CLOCS (Contrastive Learning of Cardiac Signals across Space, Time, and Patients), which aligns temporal segments and leads of the same ECG to improve robustness under lead variation and temporal drift. These hierarchical and spatial-temporal approaches extend contrastive learning beyond simple view augmentation to multi-level temporal consistency.

Raghu et al. [

68] explored multimodal extensions by pretraining contrastive models on physiological time series combined with structured clinical data such as laboratory values and vital signs. Their results indicated consistent performance gains in downstream classification tasks compared to baseline pretraining methods, demonstrating that multimodal temporal alignment improves clinical context understanding. Guo et al. [

69] proposed a Multi-Scale and Multi-Modal Contrastive Learning Network (MBSL) for biomedical signals, leveraging cross-modal contrastive objectives between modalities such as respiration, heart rate, and motion sensors. MBSL reduced mean absolute error by 33.9% for respiration rate prediction, 13.8% for exercise heart rate estimation, and improved activity recognition accuracy and F1-scores by 1.41% and 1.14%, respectively, compared to state-of-the-art baselines.

Sun et al. [

70] proposed a Patient Memory Queue (PMQ) mechanism to enhance contrastive ECG pretraining by maintaining a memory bank of intra-patient and inter-patient samples, thereby mitigating false negatives caused by random batch sampling. Across three public ECG datasets under varying label ratios, PMQ outperformed existing contrastive models in both classification accuracy and robustness to label scarcity. These patient-level memory and cross-temporal mechanisms represent a growing trend in time-series contrastive learning—moving toward architectures that explicitly encode patient identity and long-term physiological consistency.

Overall, contrastive learning for medical time-series has progressed from simple pairwise augmentation toward more sophisticated paradigms such as multi-window sampling, hierarchical contrastive structures, cross-modal alignment, and patient-aware memory designs. These innovations enable models to capture the complex temporal dynamics and inter-patient invariances inherent in physiological signals, leading to more robust and efficient representations in resource-constrained, data-limited clinical settings.

Table 1 summarizes key applications of contrastive learning across different medical domains.

5. Challenges and Limitations

Contrastive objectives rely on constructing positive and negative pairs, yet pair selection in clinical settings is nontrivial. Semantically similar cases from different patients can be mislabeled as negatives, which attenuates disease-relevant signal and may bias embeddings toward nonclinical features. Patient identity, acquisition protocol, and site effects can also leak into representations when sampling is not controlled, creating shortcuts that harm generalization.

Augmentation policies calibrated for natural images do not always transfer to medical data. Geometric or intensity transformations can erase subtle findings, while text-side heuristics (for report–image alignment) may promote surface-level matching rather than clinical semantics. Without domain-validated augmentations, models risk learning invariances that suppress small pathologies or amplify confounders.

Evaluation remains fragmented. Many studies report in-domain results on a single site, with heterogeneous metrics, label taxonomies, and train–test splits. Few works test cross-institution shifts, rare conditions, or low-label regimes in a standardized way. Reproducibility is further limited by restricted data access, incomplete reporting of pretraining corpora, and under-specified preprocessing.

Multimodal alignment introduces additional concerns. Free-text reports contain negations, hedging, and section-specific context that can misalign with image-level labels. Weak supervision mined from reports may propagate label noise if entity linking and uncertainty handling are not explicit. Privacy is also salient: paired data can inadvertently link protected health information across modalities if de-identification or differential privacy is not enforced.

From an optimization standpoint, contrastive learning can be sensitive to batch size, temperature, and queue design. Small-batch or class-imbalanced settings common in medicine can lead to representation collapse or overexposure to easy negatives. Lastly, compute requirements for large-scale pretraining restrict accessibility and hinder thorough ablations, especially for institutions without extensive infrastructure.

6. Discussion and Future Research Direction

Future work should prioritize domain-aware pairing. Patient-level positives (repeat studies, adjacent slices, longitudinal exams) and ontology-guided hard negatives (e.g., pathologies with overlapping phenotypes) can reduce false-negative pressure while sharpening clinical discrimination. For image–text models, structured extraction of entities, negation, and uncertainty, combined with section-aware weighting, can align supervision with clinical meaning rather than surface co-occurrence.

Augmentation strategies require clinical validation. Policy sets should be derived from acquisition physics and radiologist input, with sensitivity analyses that quantify the effect of each transform on small lesions and fine textures. For text, span masking and phrase-level perturbations tied to clinical entities may yield more faithful language invariances than generic token masking.

Robust evaluation protocols are needed. Benchmarks should include multi-center splits, temporal drift, device and protocol variation, and label-scarce regimes. Reporting standards ought to specify pretraining corpus composition, pairing heuristics, augmentation policies, and all hyperparameters relevant to contrastive objectives. External validation should be treated as first-class, with consistent metrics and predefined label maps across sites.

Methodological advances can target failure modes observed in practice. Debiased and supervised contrastive losses that incorporate patient groups, class priors, or calibrated hard-negative mining are promising directions. Causal contrastive variants that control for measured confounders could attenuate shortcut features. Hierarchical objectives that tie local region–phrase alignment to study-level predictions may improve fine-grained grounding and case-level consistency.

Privacy-preserving training should be integrated into pretraining pipelines. Federated contrastive learning with secure aggregation, client-specific queues, and cross-site prototype alignment can improve transfer without centralizing data. Differential privacy and selective disclosure for text encoders can reduce the risk of memorizing sensitive spans.

Finally, clinical utility depends on transparency and uncertainty. Post-hoc and concept-based explanations aligned to radiology lexicons, along with calibrated confidence and abstention options, can support safe deployment. Prospective studies and reader-in-the-loop designs are needed to test whether contrastive pretraining reduces annotation burden, improves turnaround time, or changes decision quality in real workflows.

7. Conclusion

Contrastive learning offers a practical route to exploit large volumes of unlabeled medical data, with demonstrated gains in label efficiency, zero-shot transfer, and cross-domain robustness. Progress has been most visible in vision–language alignment for radiology and pathology, extensions to physiological signals, and emerging multimodal systems that link images, text, and structured data. At the same time, reliable clinical adoption depends on careful pair construction, clinically valid augmentations, standardized and externalized evaluation, privacy-preserving training, and transparent uncertainty handling. Addressing these requirements can translate representation gains into trustworthy decision support, enabling models that generalize across institutions and remain reliable under real-world constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.O, I.D.M., K.A, E.E., and C.M.; methodology, I.D.M.; validation, I.D.M., K.A, and G.O.; investigation, I.D.M., and G.O.; resources, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, G.O, I.D.M., K.A, E.E., and C.M.; writing—review and editing, G.O, I.D.M., K.A, E.E., and C.M.; visualization, I.D.M; supervision, G.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AUROC |

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| BioViL |

Biomedical Vision–Language |

| BioViL-T |

Biomedical Vision–Language with Temporal alignment |

| BiomedCLIP |

Biomedical CLIP |

| BYOL |

Bootstrap Your Own Latent |

| CheXpert |

Chest X-ray benchmark dataset |

| CL |

Contrastive Learning |

| CLOCS |

Contrastive Learning of Cardiac Signals |

| COMET |

Hierarchical contrastive framework |

| CONCH |

Histopathology foundation model |

| ConVIRT |

Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations from Text |

| CPC |

Contrastive Predictive Coding |

| CXR-CLIP |

Chest X-Ray CLIP |

| DINO |

Self-Distillation with No Labels |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| EEG |

Electroencephalogram |

| EHR(s) |

Electronic Health Record(s) |

| F1 |

F1 score |

| GLoRIA |

Global–Local image–text alignment in radiology |

| InfoNCE |

Noise-Contrastive Estimation (loss) |

| MaCo |

Masked Contrastive Learning |

| MBSL |

Multi-Scale and Multi-Modal Contrastive Learning |

| MedCLIP |

Medical CLIP |

| MIMIC-CXR |

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care—Chest X-Ray |

| MoCo |

Momentum Contrast |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MSCL |

Multi-Scale Contrastive Learning |

| PCLR |

Patient Contrastive Learning of Representations |

| PLIP |

Pathology Language–Image Pretraining (model) |

| PMQ |

Patient Memory Queue |

| PPI(s) |

Protein–Protein Interaction(s) |

| PMC-CLIP |

PubMed Central CLIP |

| RSNA |

Radiological Society of North America |

| SAM |

Segment Anything Model |

| scRNA-seq |

single-cell RNA sequencing |

| SimCLR |

Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations |

| SwAV |

Swapping Assignments between Multiple Views |

| VQA |

Visual Question Answering |

| 1D CNN |

One-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Jung, J.H.; Mandal, T.K. Multimodal AI in Biomedicine: Pioneering the Future of Biomaterials, Diagnostics, and Personalized Healthcare. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Hussain, A.; Singh, M.; Assad, A. Deep learning in medicine: advancing healthcare with intelligent solutions and the future of holography imaging in early diagnosis. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2025, 84, 17677–17740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G.; Jordan, M.; Ilono, P. Deep convolutional neural networks in medical image analysis: A review. Information 2025, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Jere, N.; Obaido, G.; Ogunruku, O.O.; Esenogho, E.; Modisane, C. Large language models: an overview of foundational architectures, recent trends, and a new taxonomy. Discover Applied Sciences 2025, 7, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichyporuk, B.; Cardinell, J.; Szeto, J.; Mehta, R.; Falet, J.P.R.; Arnold, D.L.; Tsaftaris, S.A.; Arbel, T. Rethinking generalization: The impact of annotation style on medical image segmentation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.17398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshjou, R.; Yuksekgonul, M.; Cai, Z.R.; Novoa, R.; Zou, J.Y. Skincon: A skin disease dataset densely annotated by domain experts for fine-grained debugging and analysis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 18157–18167. [Google Scholar]

- Krenzer, A.; Makowski, K.; Hekalo, A.; Fitting, D.; Troya, J.; Zoller, W.G.; Hann, A.; Puppe, F. Fast machine learning annotation in the medical domain: a semi-automated video annotation tool for gastroenterologists. BioMedical Engineering OnLine 2022, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gouin-Vallerand, C.; Bouchard, K.; Gaboury, S.; Couture, M.; Bier, N.; Giroux, S. Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning for Sensor-Based Human Activity Recognition: A Review. IEEE Access 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, L.; Chen, D.; Song, Z. Contrastive learning for image complexity representation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.03230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wei, W.; Xia, L.; Huang, C. A comprehensive survey on self-supervised learning for recommendation. ACM Computing Surveys 2025, 58, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, J.S.; Alvarez, G.A.; Konkle, T. Contrastive learning explains the emergence and function of visual category-selective regions. Science Advances 2024, 10, eadl1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Asmatullah, L.; Malik, A.; Khan, S.; Asif, H. A Survey on Self-supervised Contrastive Learning for Multimodal Text-Image Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11101. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y. Contrastive learning with synthetic positives. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer, 2024; pp. 430–447. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Dai, Y.; Liu, F.; Wu, B.; Chen, W.; Shi, L. Swin MoCo: Improving parotid gland MRI segmentation using contrastive learning. Medical Physics 2024, 51, 5295–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.; Babu, A.R.; Zadeh, M.Z.; Banerjee, D.; Makedon, F. A survey on contrastive self-supervised learning. Technologies 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Q.; Sun, Z.; Luo, H.; Tao, D. A Survey on Self-supervised Learning: Algorithms, Applications, and Future Trends. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Ahn, E.; Feng, D.; Kim, J. A review of predictive and contrastive self-supervised learning for medical images. Machine Intelligence Research 2023, 20, 483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurrab, S.; Duwairi, R. Self-supervised learning methods and applications in medical imaging analysis: A survey. PeerJ Computer Science 2022, 8, e1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, P.; Teterwak, P.; Wang, C.; Sarna, A.; Tian, Y.; Isola, P.; Maschinot, A.; Liu, C.; Krishnan, D. Supervised contrastive learning. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 18661–18673. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Guan, Q. A comprehensive survey on contrastive learning. Neurocomputing 2024, 610, 128645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, X.; He, X. Understanding contrastive learning via distributionally robust optimization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Le-Khac, P.H.; Healy, G.; Smeaton, A.F. Contrastive representation learning: A framework and review. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 193907–193934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R. The Beginner’s Guide to Contrastive Learning. https://www.v7labs.com/blog/contrastivelearning-

guide, 2022. Accessed: 2025-10-10.

- Falcon, W.; Cho, K. A framework for contrastive self-supervised learning and designing a new approach. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.00104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, H. Voco: A simple-yet-effective volume contrastive learning framework for 3d medical image analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024; pp. 22873–22882. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, P.; Wu, X.; Ren, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y. Semi-supervised medical image segmentation via hard positives oriented contrastive learning. Pattern Recognition 2024, 146, 110020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Pham, T.X.; Niu, A.; Qiao, Z.; Yoo, C.D.; Kweon, I.S. Dual temperature helps contrastive learning without many negative samples: Towards understanding and simplifying moco. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022; pp. 14441–14450. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, D.T.; Behrmann, N.; Gall, J.; Brox, T.; Noroozi, M. Ranking info noise contrastive estimation: Boosting contrastive learning via ranked positives. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xie, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, F.L.; Wang, W.; Li, Q. Contrastive learning models for sentence representations. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2023, 14, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, F.; You, S.; Qian, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, C. Weakly supervised contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021; pp. 10042–10051. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.; Chuang, C.Y.; Sra, S.; Jegelka, S. Contrastive learning with hard negative samples. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04592. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.H.; Chang, H.J.; Auli, M.; Hsu, W.N.; Glass, J. Dinosr: Self-distillation and online clustering for self-supervised speech representation learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Girshick, R.; He, K. Improved baselines with momentum contrastive learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.04297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2020; pp. 1597–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, S.; Mustafa, B.; Ryan, F.; Beaver, Z.; Freyberg, J.; Deaton, J.; Loh, A.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Kornblith, S.; Chen, T.; et al. Big self-supervised models advance medical image classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 3478–3488. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitanya, K.; Erdil, E.; Karani, N.; Konukoglu, E. Contrastive learning of global and local features for medical image segmentation with limited annotations. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 12546–12558. [Google Scholar]

- Ciga, O.; Xu, T.; Martel, A.L. Self supervised contrastive learning for digital histopathology. Machine Learning with Applications 2022, 7, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Dong, S.; He, S.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; He, B.; Kong, Z.; et al. An improved contrastive learning network for semi-supervised multi-structure segmentation in echocardiography. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 2023, 10, 1266260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Xie, W.; Gao, R.; Zheng, T.; Chen, L.; Sun, H. Unsupervised anomaly detection in brain MRI: Learning abstract distribution from massive healthy brains. Computers in biology and medicine 2023, 154, 106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.; Rajpurkar, P.; Topol, E.J. Self-supervised learning in medicine and healthcare. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2022, 6, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pick, F.; Xie, X.; Wu, L.Y. Contrastive Multitask Transformer for Hospital Mortality and Length-of-Stay Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on AI in Healthcare; Springer, 2024; pp. 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Yang, X.; Niu, J.; Gu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W. A cross-modal clinical prediction system for intensive care unit patient outcome. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 283, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Huang, F.; Nakada, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D. Contrastive Learning on Multimodal Analysis of Electronic Health Records. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Batmanghelich, K.; Sun, L. Enhancing Biomedical Multi-modal Representation Learning with Multi-scale Pre-training and Perturbed Report Discrimination. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI); IEEE, 2024; pp. 480–485. [Google Scholar]

- Bepler, T.; Berger, B. Learning the protein language: Evolution, structure, and function. Cell systems 2021, 12, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Xie, G. Representation Learning for Multi-omics Data with Heterogeneous Gene Regulatory Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 2021; pp. 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, J.; Zhao, T.; Jia, Y.; Liu, B.; Luo, R.; Huang, Y. CellContrast: Reconstructing spatial relationships in single-cell RNA sequencing data via deep contrastive learning. Patterns 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wu, H.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, F.; et al. Pepharmony: A multi-view contrastive learning framework for integrated sequence and structure-based peptide encoding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.11360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Miura, Y.; Manning, C.D.; Langlotz, C.P. Contrastive learning of medical visual representations from paired images and text. In Proceedings of the Machine learning for healthcare conference. PMLR, 2022; pp. 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.C.; Shen, L.; Lungren, M.P.; Yeung, S. Gloria: A multimodal global-local representation learning framework for label-efficient medical image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 3942–3951. [Google Scholar]

- Boecking, B.; Usuyama, N.; Bannur, S.; Castro, D.C.; Schwaighofer, A.; Hyland, S.; Wetscherek, M.; Naumann, T.; Nori, A.; Alvarez-Valle, J.; et al. Making the most of text semantics to improve biomedical vision–language processing. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision; Springer, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bannur, S.; Hyland, S.; Liu, Q.; Perez-Garcia, F.; Ilse, M.; Castro, D.C.; Boecking, B.; Sharma, H.; Bouzid, K.; Thieme, A.; et al. Learning to exploit temporal structure for biomedical vision-language processing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 15016–15027. [Google Scholar]

- You, K.; Gu, J.; Ham, J.; Park, B.; Kim, J.; Hong, E.K.; Baek, W.; Roh, B. Cxr-clip: Toward large scale chest x-ray language-image pre-training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2023; pp. 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tiu, E.; Talius, E.; Patel, P.; Langlotz, C.P.; Ng, A.Y.; Rajpurkar, P. Expert-level detection of pathologies from unannotated chest X-ray images via self-supervised learning. Nature biomedical engineering 2022, 6, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Agarwal, D.; Sun, J. Medclip: Contrastive learning from unpaired medical images and text. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2022, Vol. 2022, p. 3876.

- Huang, Z.; Bianchi, F.; Yuksekgonul, M.; Montine, T.J.; Zou, J. A visual–language foundation model for pathology image analysis using medical twitter. Nature medicine 2023, 29, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Y.; Chen, B.; Williamson, D.F.; Chen, R.J.; Liang, I.; Ding, T.; Jaume, G.; Odintsov, I.; Le, L.P.; Gerber, G.; et al. A visual-language foundation model for computational pathology. Nature medicine 2024, 30, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, Y.; Usuyama, N.; Xu, H.; Bagga, J.; Tinn, R.; Preston, S.; Rao, R.; Wei, M.; Valluri, N.; et al. Biomedclip: a multimodal biomedical foundation model pretrained from fifteen million scientific image-text pairs. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.00915. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, W. Pmc-clip: Contrastive language-image pre-training using biomedical documents. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer, 2023; pp. 525–536. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Li, C.; Zhou, H.Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S. Enhancing representation in radiography-reports foundation model: A granular alignment algorithm using masked contrastive learning. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koleilat, T.; Asgariandehkordi, H.; Rivaz, H.; Xiao, Y. Medclip-sam: Bridging text and image towards universal medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention; Springer, 2024; pp. 643–653. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Alavi, A.; Li, M.; Zhang, X. Self-supervised contrastive learning for medical time series: A systematic review. Sensors 2023, 23, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamant, N.; Reinertsen, E.; Song, S.; Aguirre, A.D.; Stultz, C.M.; Batra, P. Patient contrastive learning: A performant, expressive, and practical approach to electrocardiogram modeling. PLoS computational biology 2022, 18, e1009862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Van Duyn, J.; Yan, R.; Huang, Z.; Vesal, S.; Plis, S.; Hu, X.; Kwak, G.H.; Xiao, R.; Fedorov, A. Learning ECG Representations via Poly-Window Contrastive Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.15225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Contrast everything: A hierarchical contrastive framework for medical time-series. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2023, 36, 55694–55717. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M. Temporal and spatial self supervised learning methods for electrocardiograms. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, A.; Chandak, P.; Alam, R.; Guttag, J.; Stultz, C. Contrastive pre-training for multimodal medical time series. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Learning from Time Series for Health, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Xu, X.; Wu, H.; Liu, B.; Xia, J.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, J.; et al. Multi-scale and multi-modal contrastive learning network for biomedical time series. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2025, 106, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Y.; Dong, X. Enhancing Contrastive Learning-based Electrocardiogram Pretrained Model with Patient Memory Queue. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06310. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).