1. Introduction

1.1. Evolution of HIV Prevention

Over three decades of antiretroviral research has fundamentally transformed HIV prevention, evolving from early monotherapy approaches to combination regimens, and now to long-acting injectable formulations. This evolution reflects a core principle: HIV prevention effectiveness depends not only on pharmacological efficacy but on how well prevention modalities fit into people’s lives. Daily oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir/emtricitabine demonstrates 44–92% efficacy depending on adherence levels and populations studied [

1,

2]. However, oral PrEP’s effectiveness in real-world settings is limited by the daily decision-making required for adherence. Long-acting injectable PrEP addresses this by shifting adherence from individual daily behavioral choices to structured healthcare systems.

1.2. Clinical Efficacy: Robust Evidence Across Diverse Populations

Clinical trials have consistently demonstrated remarkable efficacy for LAI-PrEP across diverse populations. HPTN 083 enrolled 4,566 cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women, demonstrating 66% superior efficacy of cabotegravir compared to oral TDF/FTC [

3]. HPTN 084 enrolled 3,224 cisgender women in sub-Saharan Africa and demonstrated 89% superior efficacy, with early trial termination for efficacy [

4].

The PURPOSE program represents the most comprehensive HIV prevention trial program conducted to date. PURPOSE-1 enrolled 5,338 cisgender women in South Africa and Uganda, with zero HIV infections in the lenacapavir arm—representing >96% efficacy versus background incidence [

5]. PURPOSE-2 enrolled 3,265 participants across gender identities (cisgender men, transgender women, transgender men, and gender-diverse persons), demonstrating consistent 96% efficacy across all groups [

6]. PURPOSE-3, PURPOSE-4, and PURPOSE-5 are ongoing trials evaluating historically underrepresented populations including U.S. women of color, people who inject drugs, and diverse global key populations [

7].

Phase 1 studies of once-yearly lenacapavir demonstrated plasma concentrations above efficacy thresholds for ≥56 weeks, with Phase 3 trials planned for 2025 [

8]. These data establish clinical efficacy across diverse populations.

Supplementary File S1 provides detailed clinical trial evidence and safety considerations.

1.3. Safety Considerations: Lessons from Islatravir

The development and discontinuation of islatravir for PrEP demonstrates that long-acting formulations require heightened safety monitoring given their pharmacokinetic irreversibility [

9,

10]. Conservative initiation protocols for cabotegravir and lenacapavir reflect this principle: the bridge period between prescription and injection is part of a safety framework for medications that cannot be rapidly removed from the body.

Supplementary File S1 details safety considerations relevant to bridge period management.

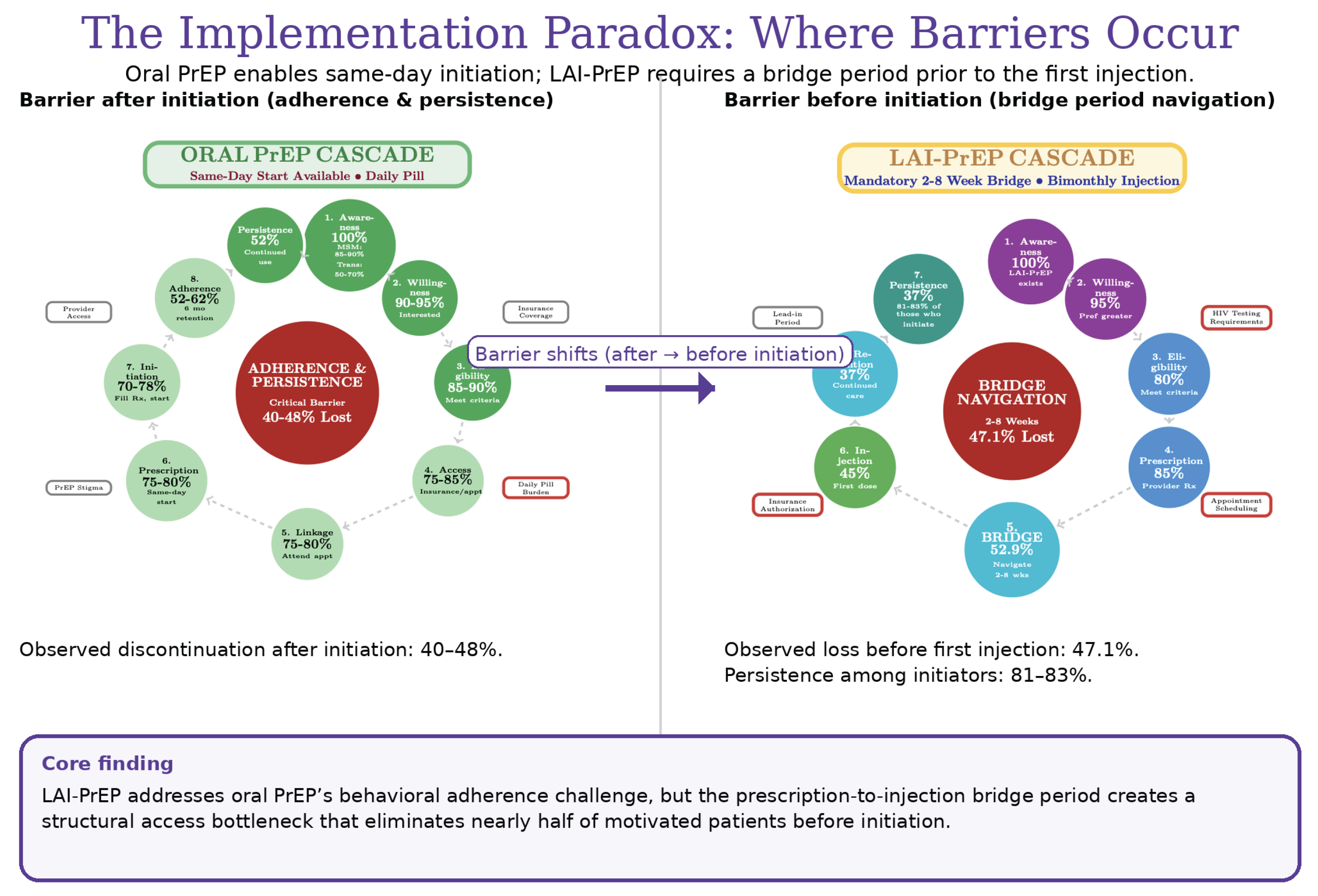

1.4. Implementation Reality: The Critical Gap

Despite extraordinary clinical efficacy, real-world LAI-PrEP implementation faces a significant paradox. In the CAN Community Health Network study—one of the largest real-world LAI-PrEP implementation cohorts—only 52.9% of individuals prescribed LAI-PrEP received their first injection [

11]. This 47% attrition occurs before the first dose is administered, among individuals who have already navigated awareness, eligibility assessment, and clinical decision-making.

In contrast, persistence data from Trio Health demonstrate that 81–83% of individuals receiving at least one cabotegravir injection remain engaged with continuing care [

12]. This striking contrast reveals a fundamental structural mismatch: LAI-PrEP addresses oral PrEP’s adherence challenge but creates a new structural barrier during bridge period navigation.

1.5. Scope and Objectives

This review proposes that bridge period navigation represents the critical implementation barrier for LAI-PrEP, distinct from well-characterized barriers to oral PrEP persistence. We synthesize clinical trial evidence with implementation data to: (1) characterize the bridge period as a distinct implementation stage, (2) quantify population-specific barriers, (3) synthesize evidence on strategies to improve bridge period completion, and (4) identify research priorities for translating LAI-PrEP’s clinical efficacy into public health impact.

1.6. Convergent Evidence on Primary Barriers

Across diverse implementation settings, a consistent pattern has emerged: LAI-PrEP’s primary implementation barrier occurs before first injection, during bridge period navigation. This fundamentally differs from oral PrEP, where the primary barrier occurs after initiation during persistence. This convergent evidence across multiple implementation contexts supports reconceptualizing the PrEP cascade to explicitly recognize bridge period navigation as a distinct implementation step.

2. The Reconceptualized PrEP Cascade: Making the Bridge Period Visible

2.1. Traditional vs. LAI-PrEP Care Cascades

The traditional HIV PrEP cascade, developed for oral formulations, consists of sequential steps: awareness, willingness, prescription, initiation, and persistence [

13]. In this model, prescription and initiation occur simultaneously or within days; individuals receive a prescription and begin daily oral PrEP immediately, with protective drug levels achieved within 7 days for receptive anal exposure or 21 days for receptive vaginal exposure [

14].

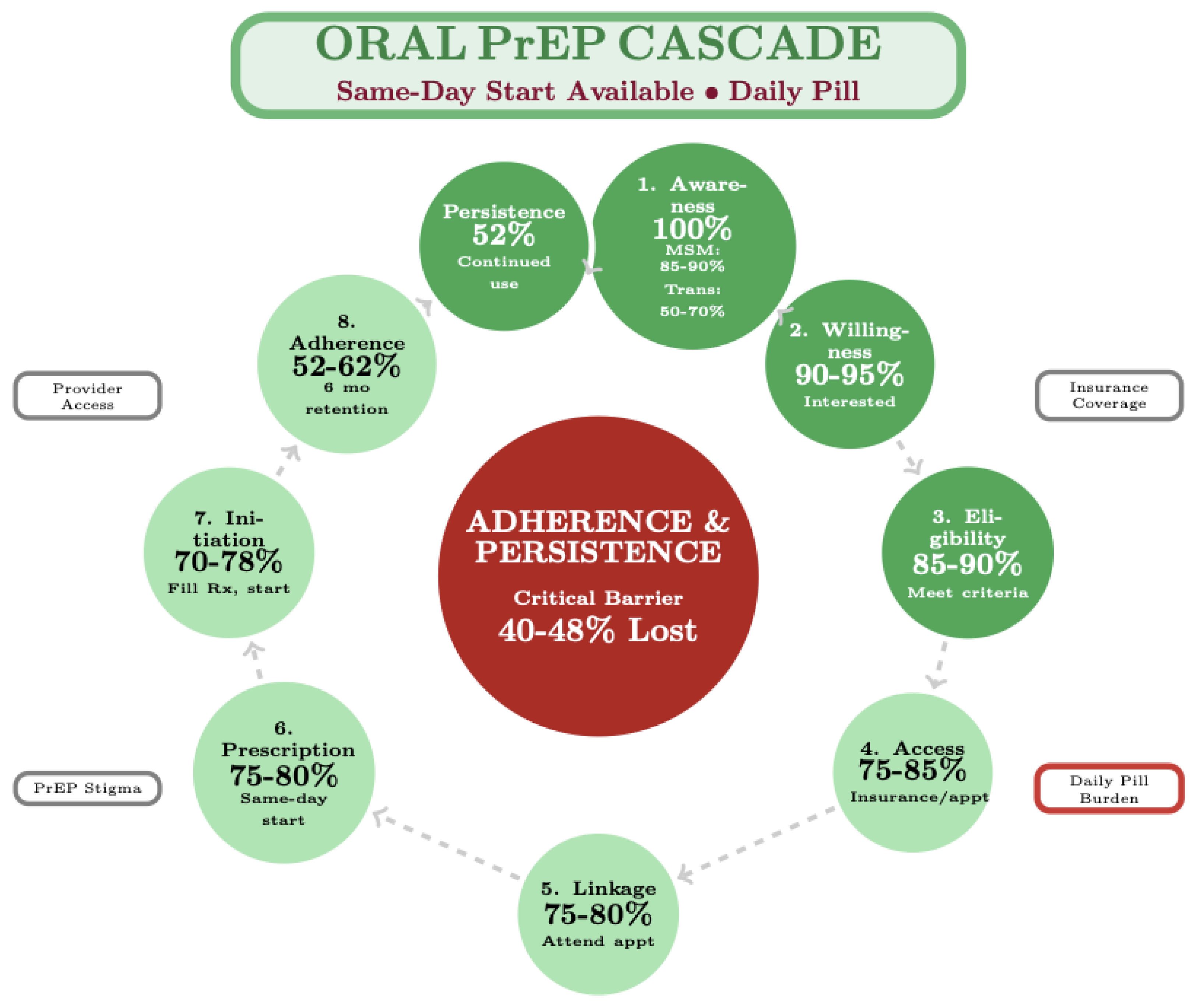

Figure 1.

Oral PrEP Cascade: Post-Initiation Adherence Barrier. The oral PrEP cascade enables same-day initiation with sequential progression through nine steps. The primary implementation barrier occurs post-initiation with 40–48% discontinuation due to daily pill burden and adherence challenges. Population-specific discontinuation varies: transgender individuals show highest rates (70%), followed by young MSM (44–69%) and cisgender women (48–56%). The primary implementation challenge is behavioral rather than structural. Data sources: HPTN 083 (n=4,566), HPTN 084 (n=3,224), and PrEP cascade framework.

Figure 1.

Oral PrEP Cascade: Post-Initiation Adherence Barrier. The oral PrEP cascade enables same-day initiation with sequential progression through nine steps. The primary implementation barrier occurs post-initiation with 40–48% discontinuation due to daily pill burden and adherence challenges. Population-specific discontinuation varies: transgender individuals show highest rates (70%), followed by young MSM (44–69%) and cisgender women (48–56%). The primary implementation challenge is behavioral rather than structural. Data sources: HPTN 083 (n=4,566), HPTN 084 (n=3,224), and PrEP cascade framework.

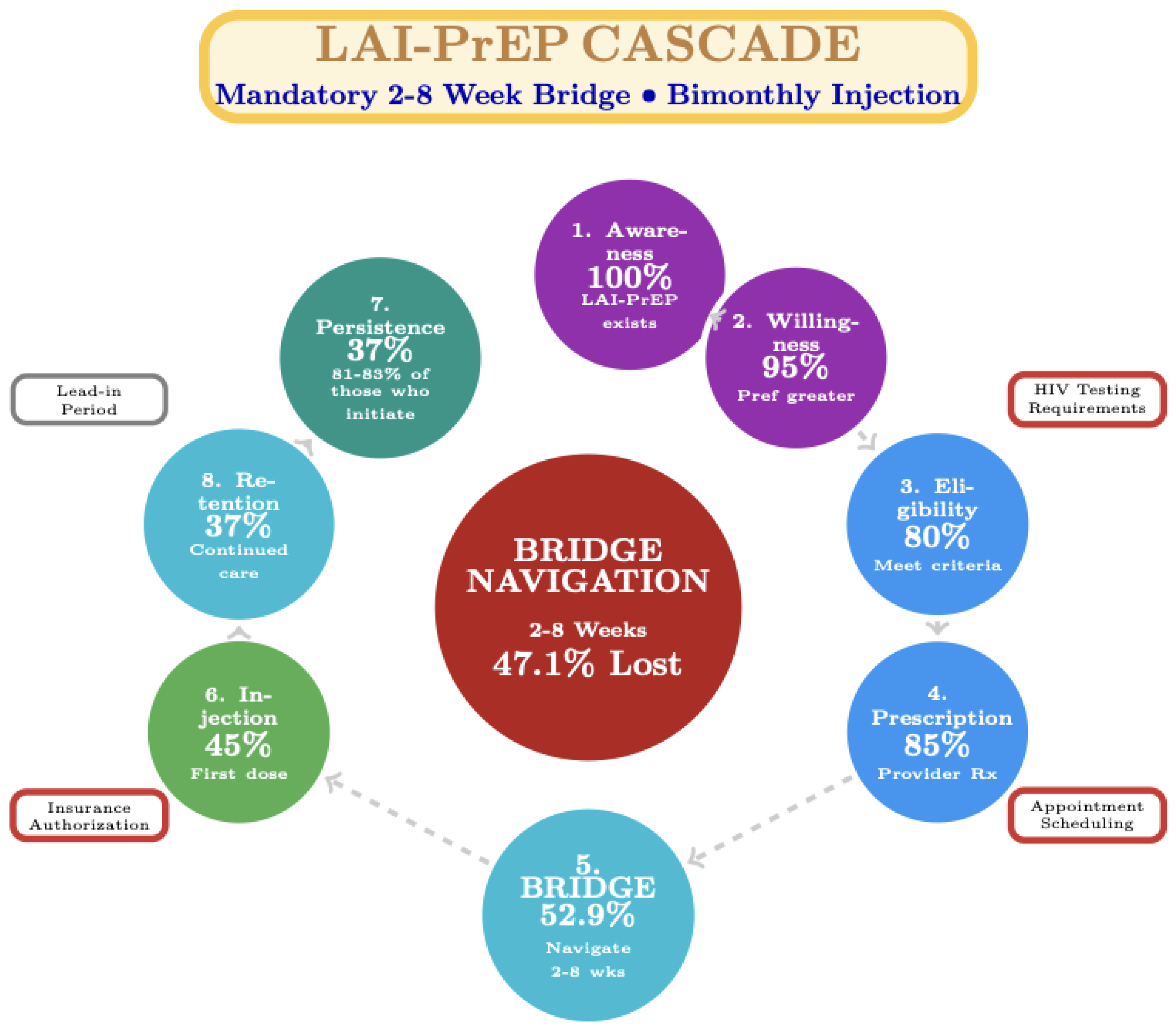

Figure 2.

LAI-PrEP Cascade: Pre-Initiation Bridge Period Barrier. LAI-PrEP introduces a bridge period between prescription and first injection, creating a distinct implementation step. Bridge period navigation represents the critical implementation barrier, with 47.1% of prescribed individuals not receiving the first injection due to HIV testing delays, insurance authorization barriers, and appointment coordination challenges. This represents a fundamental shift from oral PrEP’s post-initiation adherence barrier to a pre-initiation structural barrier. Those successfully navigating the bridge show superior persistence (81–83%) compared to oral PrEP (52%). Data sources: CAN Community Health Network (47.1% bridge period attrition), Trio Health (81–83% persistence), HPTN 083/084 and PURPOSE-1/2 (efficacy data).

Figure 2.

LAI-PrEP Cascade: Pre-Initiation Bridge Period Barrier. LAI-PrEP introduces a bridge period between prescription and first injection, creating a distinct implementation step. Bridge period navigation represents the critical implementation barrier, with 47.1% of prescribed individuals not receiving the first injection due to HIV testing delays, insurance authorization barriers, and appointment coordination challenges. This represents a fundamental shift from oral PrEP’s post-initiation adherence barrier to a pre-initiation structural barrier. Those successfully navigating the bridge show superior persistence (81–83%) compared to oral PrEP (52%). Data sources: CAN Community Health Network (47.1% bridge period attrition), Trio Health (81–83% persistence), HPTN 083/084 and PURPOSE-1/2 (efficacy data).

LAI-PrEP introduces a fundamentally different implementation structure. A substantial temporal and procedural gap exists between prescription and first injection. Unlike oral PrEP’s same-day start capability, LAI-PrEP requires confirmation of HIV-negative status through testing with appropriate window period considerations, creating a “bridge period” between clinical prescription decision and treatment initiation.

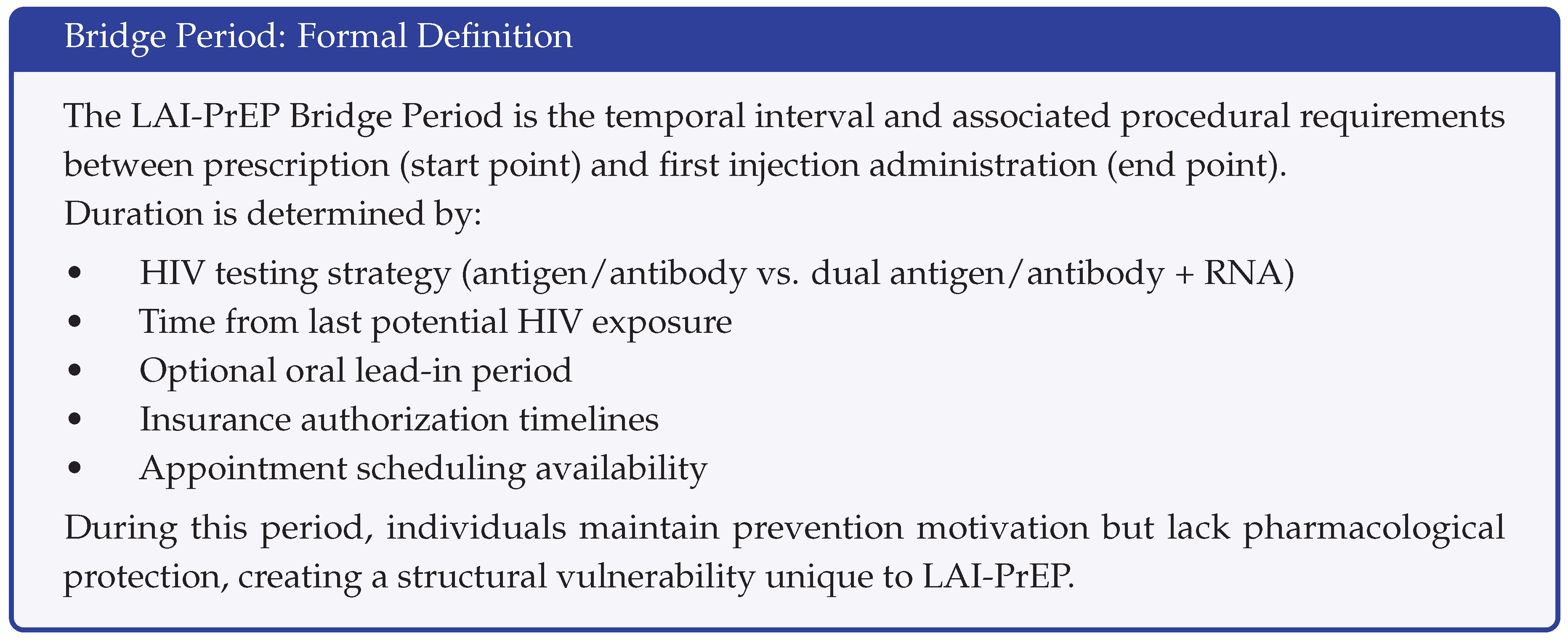

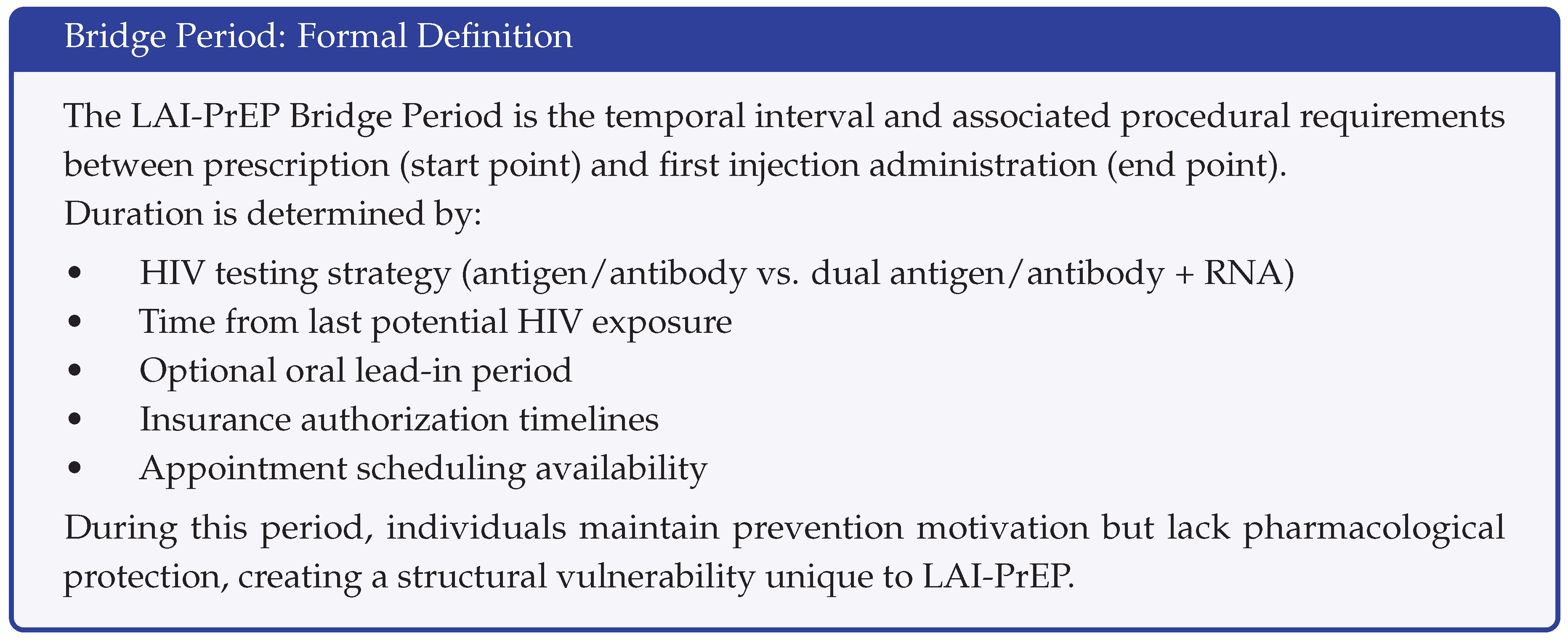

2.2. The Bridge Period: Definition and Components

The bridge period encompasses all activities and time intervals between the clinical decision to prescribe LAI-PrEP and first injection administration. Bridge period activities include:

Core requirements:

Baseline HIV testing (antigen/antibody test within 7 days of planned injection)

Additional HIV-1 RNA testing if recent exposure or transitioning from oral PrEP

Injection appointment coordination and attendance

Insurance authorization (when required)

Extended bridge period factors:

Repeat HIV testing if initial testing predates injection appointment by >7 days

Optional oral lead-in period (for cabotegravir tolerability assessment)

Insurance authorization appeals or delays

Individual scheduling barriers

Transportation or logistical obstacles

The bridge period creates a unique structural vulnerability: individuals remain motivated for prevention (having navigated awareness, willingness, and clinical eligibility) but lack protection while navigating procedural requirements. HIV acquisition during bridge period represents a system failure specific to LAI-PrEP that does not occur with oral formulations.

The structural contrast between oral and LAI-PrEP cascades is fundamental: oral PrEP’s primary barrier occurs post-initiation (adherence), while LAI-PrEP’s primary barrier occurs pre-initiation (bridge period). This distinction has direct implications for intervention design and resource allocation.

2.3. Proposed Reconceptualized Cascade

We propose an LAI-PrEP cascade explicitly recognizing bridge period navigation as a distinct implementation step:

Awareness: Knowledge that LAI-PrEP exists as a prevention option

Willingness: Interest in injectable formulations as viable approach

Eligibility: Clinical criteria and baseline testing requirements met

Prescription: Clinical decision to initiate LAI-PrEP

-

Bridge Period Navigation: Successful completion of requirements between prescription and injection

HIV testing completion and negative result within appropriate window

Injection appointment scheduling and attendance

Financial/insurance barrier resolution

Optional oral lead-in period completion

Injection Initiation: Receipt of first LAI-PrEP injection

Persistence: Continued receipt of subsequent injections per protocol

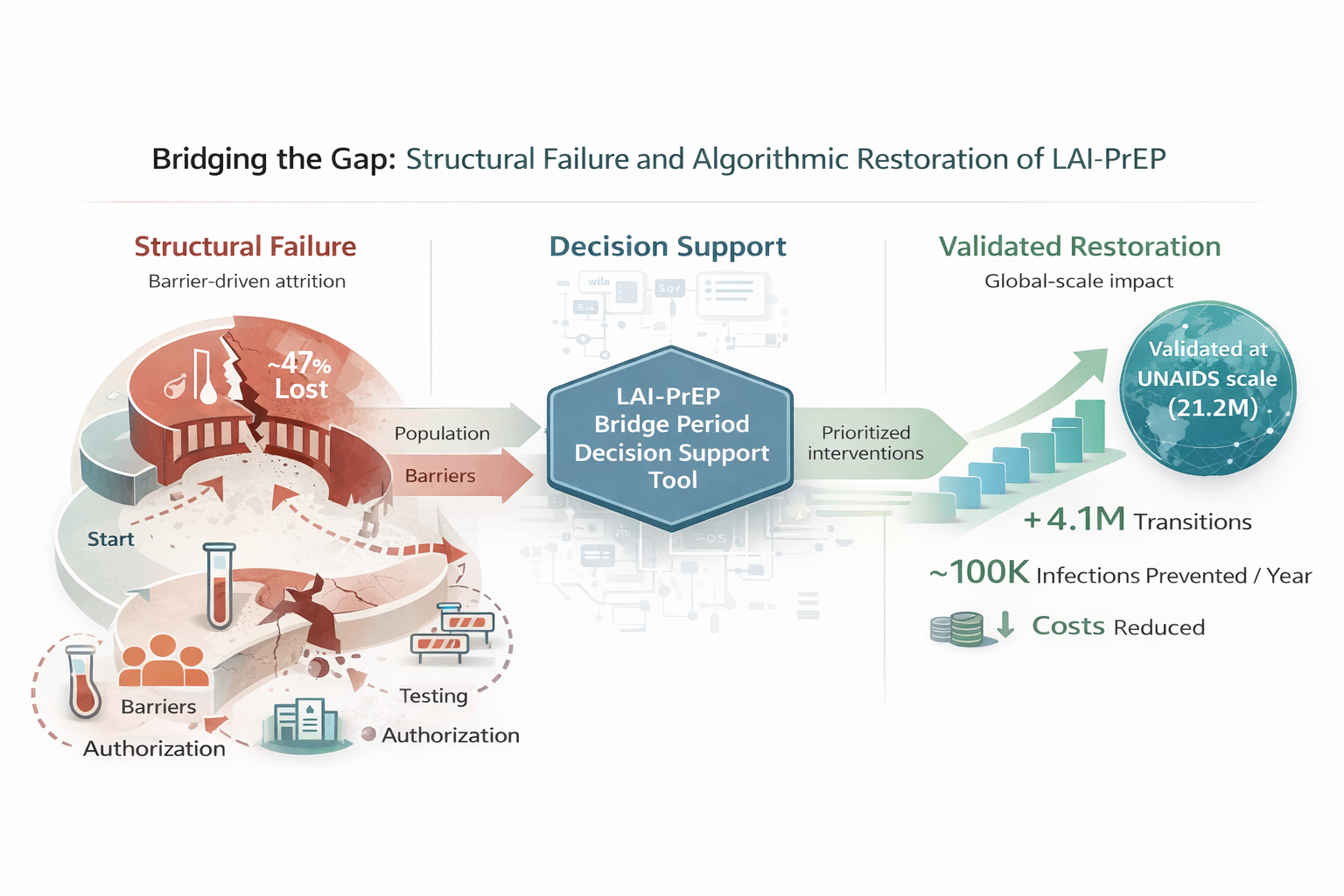

Figure 3.

Implementation Paradox: Where Barriers Occur. Left: Oral PrEP cascade shows wide entry (same-day initiation), with 40–48% discontinuation post-initiation. Right: LAI-PrEP cascade shows narrow entry (2–8 week bridge period) eliminating 47% pre-initiation, but 81–83% persistence among those initiating. LAI-PrEP solves oral PrEP’s behavioral adherence problem but introduces a structural access barrier. This fundamental difference requires distinct implementation strategies focused on system-level rather than individual-level interventions. Data sources: HPTN 083/084, CAN Community Health Network, Trio Health.

Figure 3.

Implementation Paradox: Where Barriers Occur. Left: Oral PrEP cascade shows wide entry (same-day initiation), with 40–48% discontinuation post-initiation. Right: LAI-PrEP cascade shows narrow entry (2–8 week bridge period) eliminating 47% pre-initiation, but 81–83% persistence among those initiating. LAI-PrEP solves oral PrEP’s behavioral adherence problem but introduces a structural access barrier. This fundamental difference requires distinct implementation strategies focused on system-level rather than individual-level interventions. Data sources: HPTN 083/084, CAN Community Health Network, Trio Health.

This reconceptualized cascade makes visible where 47% of LAI-PrEP candidates currently experience attrition. Naming bridge period navigation as a distinct cascade step creates accountability for measurement and intervention at this clinical juncture.

2.4. Measurement Implications

The reconceptualized cascade requires new measurement approaches:

Bridge period success rate: Percentage of prescribed individuals receiving first injection (current baseline: 53%; potential target: ≥75%)

Bridge period duration: Median time from prescription to injection (current variable; potential target: <14 days)

Attrition causes: Categorization of why individuals do not complete bridge period (testing delays, insurance barriers, appointment no-shows, individual decision, loss to follow-up)

Population-stratified metrics: Bridge period completion rates for key populations (MSM, women, people who inject drugs, adolescents, transgender individuals)

2.5. Implementation Monitoring Framework

Programs operationalizing the reconceptualized cascade may track core metrics:

Bridge period success rate: Prescribed to injection ratio (baseline: 53%; target: ≥75%)

Time to injection: Median days from prescription to first injection (target: <14 days for ≥75% of individuals)

Attrition characterization: Categorized causes of bridge period incompletion

Population-stratified completion: Success rates by key populations

Oral-to-injectable transition rate: Proportion initiated via direct transition from oral PrEP

Enhanced testing utilization: Percentage receiving HIV-1 RNA testing at baseline

Navigation program reach: Proportion of prescriptions referred to support services

These metrics enable programs to identify bottlenecks, compare performance across sites, evaluate intervention effectiveness, and monitor whether LAI-PrEP implementation reduces or exacerbates HIV prevention disparities.

3. Population-Specific Bridge Period Barriers

3.1. Adolescents (Ages 16–24)

Adolescents face unique developmental and structural barriers to bridge period completion despite demonstrating comparable pharmacokinetics and efficacy to adults. Developmental factors including temporal discounting create challenges for navigating multi-week delays between prescription and injection. Privacy concerns are substantial: surveys of Black female adolescents documented that concerns about parental discovery through insurance explanation of benefits created reluctance to initiate despite high HIV risk [

15]. The bridge period amplifies these concerns through multiple visits and appointments. Based on general population attrition (47%) and adolescent-specific barriers, bridge period completion in adolescents is projected at 30–40%.

Detailed adolescent-specific considerations are presented in Supplementary File S2.

3.2. Women

Women, particularly Black and Latina women, navigate intersecting structural barriers including transportation challenges, childcare responsibilities, and competing caregiving demands that complicate bridge period completion [

15]. Medical mistrust rooted in historical and ongoing experiences of medical racism manifests as concerns about side effects (identified by 39% as primary barrier) and skepticism toward prevention recommendations. Clinical trials demonstrated 89% efficacy among cisgender women (HPTN 084) and zero infections among 5,338 women (PURPOSE-1), but these results occurred in research settings with intensive support. PURPOSE-3 will provide real-world implementation data for U.S. women of color.

Detailed considerations are in Supplementary File S2.

3.3. People Who Inject Drugs (PWID)

PWID encounter perhaps the most severe structural barriers to bridge period navigation. Criminalization of drug use creates fear of legal consequences and healthcare discrimination, with 17% of PWID avoiding care entirely [

16]. Housing instability affects substantial proportions, creating cascading barriers including lack of stable contact information for appointment reminders and transportation challenges. PrEP awareness among PWID remains low (40% in Los Angeles/San Francisco surveys), with only 2% currently using it despite indicated need [

17]. Syringe service programs represent the most promising delivery setting but face resource constraints limiting bridge period support [

18]. Multiple intersecting barriers project bridge period completion in PWID at 20–30%. PURPOSE-4 will provide critical implementation evidence.

Detailed PWID implementation considerations are in Supplementary File S2.

3.4. Other Key Populations

Transgender women demonstrated excellent efficacy results (HPTN 083, PURPOSE-2) but face healthcare discrimination and economic marginalization complicating bridge period navigation. MSM show highest current LAI-PrEP uptake yet experience 47% bridge period attrition, indicating substantial improvement opportunity. PURPOSE-1 included pregnant and lactating individuals from study inception, introducing bridge period considerations including pregnancy testing requirements and competing prenatal care priorities. Detailed population-specific information is in Supplementary File S2.

3.5. Equity Implications

Bridge period barriers create health equity risks. As structural barriers affect all populations but resources to address them are unequally distributed, LAI-PrEP implementation risks widening rather than narrowing HIV prevention disparities. Populations experiencing highest HIV incidence and lowest healthcare access encounter greatest bridge period barriers. Yet these same populations benefit most from LAI-PrEP’s independence from daily adherence. Prioritizing bridge period support for populations experiencing HIV-related disparities is essential to ensure LAI-PrEP implementation reduces inequities rather than exacerbating them.

3.6. Global Implementation Context

Global LAI-PrEP implementation introduces additional complexities beyond U.S. settings, including medication cold chain requirements, healthcare workforce capacity, and regional policy considerations. Sub-Saharan Africa represents 62% of global PrEP need but faces amplified structural barriers. Detailed global implementation considerations are in Supplementary File S3.

4. Evidence-Based Strategies to Improve Bridge Period Completion

4.1. Eliminating the Bridge Period: Oral-to-Injectable Transitions

The most effective bridge period management strategy is complete elimination through seamless transitions from oral PrEP to LAI-PrEP. Individuals engaged in oral PrEP demonstrate prior prevention motivation, established provider relationships, recent negative HIV testing, and proven ability to navigate healthcare systems. Transitioning directly from oral to injectable PrEP eliminates multiple bridge period barriers including extended HIV testing requirements and need for new provider engagement.

Real-world data from HIV treatment populations demonstrate substantially higher injection initiation rates (approximately 50%) compared to PrEP-naive individuals (53%), suggesting oral-to-injectable transitions could achieve 80–90% initiation rates. Implementation strategies include same-day transition protocols for individuals with current HIV testing, proactive switching discussions normalizing injectable options, streamlined insurance authorization for switches, and provider education on simplified transition protocols.

Approximately 50% of oral PrEP users discontinue within 6–12 months, creating a secondary target population potentially highly motivated to switch modalities addressing adherence challenges. Re-engagement of former oral PrEP users with LAI-PrEP represents important implementation opportunity.

4.2. Compressing the Bridge Period: Accelerated Diagnostic Pathways

When oral-to-injectable transitions are not possible, accelerated HIV testing strategies can shorten bridge period duration. Current CDC guidelines recommend antigen/antibody testing alone for current oral PrEP users, enabling same-visit transition. For PrEP-naive individuals, dual testing (antigen/antibody + RNA) detects acute infections earlier, reducing window period from 45 days to 10–14 days and enabling bridge completion within 2–3 weeks.

Point-of-care RNA platforms providing results within 90 minutes enable single-visit dual testing where available. Laboratory-expedited processing of baseline tests can reduce result turnaround to 24–48 hours. Risk-stratified testing approaches reserve comprehensive RNA testing for highest-risk scenarios while maintaining timely initiation for lower-risk individuals.

WHO July 2025 guidance recommends simplified HIV testing for LAI-PrEP initiation, reflecting a public health approach that prioritizes access over maximal risk reduction when resource constraints exist. This approach reflects different risk-benefit calculations in resource-limited versus well-resourced settings.

4.3. Navigating the Bridge Period: Patient Navigation Programs

When complete elimination or compression are not feasible, intensive navigation support improves bridge period completion. Patient navigation uses trained personnel to identify and mitigate financial, cultural, logistic, and educational barriers to healthcare access. San Francisco navigation programs demonstrated 1.5-fold increase in PrEP initiation rates, while cancer care navigation meta-analyses show 10–40% improvement in treatment initiation, with greatest benefits for disadvantaged populations [

19,

20,

21].

Bridge period navigation approaches include dedicated navigators supporting prescription-to-injection transition, text message-based appointment reminders and support, peer navigation leveraging lived experience, and population-tailored approaches addressing specific barriers for adolescents, women, PWID, and transgender individuals.

Financial barriers during bridge period extend beyond medication costs to transportation, childcare, and opportunity costs. System-level interventions including telemedicine integration for counseling, pharmacist-led LAI-PrEP delivery in community settings, harm reduction service integration for PWID, and mobile clinic models can reduce bridge period completion barriers. Detailed navigation and system-level strategies are in Supplementary File S4.

5. Research Priorities

Translating LAI-PrEP’s clinical efficacy into public health impact requires systematic research across multiple domains. Priority areas include: (1) real-world bridge period measurement in diverse settings including resource-limited contexts, (2) population-specific implementation studies emerging from PURPOSE-3/4/5 and HPTN 102/103, (3) comparative effectiveness of testing acceleration and navigation strategies, (4) economic evaluation of bridge period interventions across healthcare system types, and (5) explicit equity monitoring systems ensuring LAI-PrEP implementation reduces rather than exacerbates HIV prevention disparities. A comprehensive research agenda is in Supplementary File S5.

6. Conclusions

Long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis represents a transformative advance in HIV prevention, demonstrating >96% efficacy across diverse populations, superior persistence compared to oral PrEP (81–83% vs. ∼52%), and strong user preference (67% favor injections over daily pills). However, this clinical success cannot translate into meaningful public health impact if nearly half of prescribed individuals never receive their first injection.

This review fundamentally reframes the LAI-PrEP implementation challenge. LAI-PrEP’s structural advantage shifts the implementation question from individual adherence capacity to healthcare system delivery capability. This shift from post-initiation behavioral barriers to pre-initiation structural barriers necessitates corresponding innovations in cascade conceptualization, measurement frameworks, and intervention design.

Equity implications are profound. Populations facing greatest structural barriers—PWID (projected 70–80% bridge period attrition), adolescents (60–70%), and women (50–60%)—experience highest bridge period losses, threatening to widen HIV prevention disparities despite LAI-PrEP’s superior efficacy. Paradoxically, these populations demonstrate greatest potential benefit from targeted bridge period interventions. Computational modeling demonstrates that evidence-based bridge period management could improve global initiation success from approximately 24% to 44%, with PWID showing 265% relative improvement and adolescents showing 147% improvement. Addressing bridge period barriers is thus simultaneously an equity imperative and an implementation efficiency opportunity.

Evidence-based strategies operate through complementary mechanisms: eliminating bridge periods through oral-to-injectable transitions, compressing bridge periods through accelerated testing, navigating bridge periods through structured support, and removing structural barriers through integrated service delivery. Conservative initiation protocols serve important safety functions given LAI-PrEP’s pharmacokinetic irreversibility. The implementation challenge is not abandoning safety but streamlining processes sufficiently to retain motivated individuals during necessary waiting periods.

Realizing LAI-PrEP’s potential requires systematic attention to prescription-to-protection gaps. The traditional cascade must be reconceptualized to explicitly recognize bridge period navigation as a distinct, measurable implementation step. Ongoing implementation trials (HPTN 102, HPTN 103) will generate population-tailored intervention evidence. Companion computational validation demonstrates how clinical decision support tools can operationalize bridge period management strategies across diverse clinical contexts and populations, providing a scalable pathway for systematic implementation. By addressing this structural gap through infrastructure investment, protocol innovation, and equity-focused approaches, LAI-PrEP can be transformed from a clinically proven but underutilized intervention into a cornerstone of HIV prevention realizing its promise for all populations who need it.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

A.C.D. conducted all aspects of this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the patients, clinicians, and researchers whose work in LAI-PrEP clinical trials and real-world implementation has informed this review. The author thanks the implementation scientists and community partners working to translate prevention research into equitable, effective HIV prevention services.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

This manuscript was developed with assistance from artificial intelligence tools, including Anthropic Claude, for literature synthesis, manuscript structure, and technical writing. The author maintains full responsibility for all scientific content, interpretation of evidence, and conclusions.

Conflicts of Interest

A.C.D. was formerly employed by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (2020–2024); all stock holdings were divested by December 2024. This independent research received no industry funding. The decision support tool accompanying this review is provided open-source without commercial interests.

References

- Grant, R.M.; Lama, J.R.; Anderson, P.L.; McMahan, V.; Liu, A.Y.; Vargas, L.; Goicochea, P.; Casapiá, M.; Guanira-Carranza, J.V.; Ramirez-Cardich, M.E.; et al. Preexposure Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men Who Have Sex with Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2587–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landovitz, R.J.; Scott, H.; Deeks, S.G. Prevention of HIV-1 Infection with Antiretroviral Drugs. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landovitz, R.J.; Donnell, D.; Clement, M.E.; Hanscom, B.; Cottle, L.; Coelho, L.; Cabello, R.; Chariyalertsak, S.; Dunne, E.F.; Frank, I.; et al. Cabotegravir for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Men and Transgender Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Hughes, J.P.; Bock, P.; Ouma, S.G.; Hunidzarira, P.; Kalonji, D.; Kayange, N.; Makhema, J.; Mandima, P.; Mathebula, M.; et al. Cabotegravir for the Prevention of HIV-1 in Women: Results from HPTN 084. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2043–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L.G.; Marzinke, M.A.; Mathews, R.P.; Hendrix, C.W.; Maskew, M.; Lalloo, U.; Grinsztejn, B.; Chege, W.; Dezzutti, C.S.; Richardson, P.; et al. Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir or Daily F/TAF for HIV Prevention in Cisgender Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbuagu, O.; Matthews, R.P.; Bares, S.H.; Asundi, A.; Chege, W.; DiNenno, E.; Dimova, R.B.; Felizarta, F.; Huhn, G.; Lama, J.R.; et al. Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir for HIV Prevention in Men and Gender-Diverse Persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. PURPOSE Trial Protocol and Safety Monitoring. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, L.G.; Marzinke, M.A.; Hendrix, C.W.; Gombe Mbalawa, C.; Mohammed, H.; Xiao, J.; Dorey, D.; Martin, A.; McCallister, S.; Deng, Y.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Once-Yearly Lenacapavir: A Phase 1, Open-Label Study. Lancet 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.P.; Barrett, S.E.; Covino, R.J.; Hamm, T.E.; Gupta, S.K.; Marzinke, M.A.; Hendrix, C.W.; Anton, P.A.; Mathias, A.; Hanes, J.; et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Islatravir Subdermal Implant for HIV-1 Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 1 Trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1712–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merck Sharp & Dohme. Islatravir Phase 2a Oral PrEP Data. 2021.

- Patel, R.R.; et al. Cabotegravir Prescriptions and the Gap between Prescription and Initiation. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trio Health Research Group. Persistence Rates in Cabotegravir Recipients. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Traditional PrEP cascade framework.

- Oral PrEP efficacy and persistence data.

- Crooks, L.; et al. Barriers to PrEP Access among Black Adolescent and Young Adult Women. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Colledge, G.; Hess, K.L.; Crepaz, N. Healthcare Discrimination and Avoidance among PWID. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw, S.; et al. PrEP Awareness and Use among PWID in LA and SF. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Feelemyer, J.; LaKosky, P.; Szymanowski, K.; Arasteh, K. Expansion of Syringe Service Programs in the United States, 2015–2018. American Journal of Public Health 2020, 110, 517–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale-Pereira, A.; Enard, K.R.; Nevarez, L.; Jones, L.A. The Role of Patient Navigators in Eliminating Health Disparities. Cancer 2011, 117, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.A.; Patel, R.R.; Mena, L.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Rose, J.; Levine, P.; Nunn, A.A. A Panel Management and Patient Navigation Intervention Is Associated with Earlier PrEP Initiation in a Safety-Net Primary Care Health System. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2018, 79, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, V.; Hoehn, R.S. Patient Navigation in Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review. J. Oncol. Pract. 2024, 20, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).