1. Introduction

VR has garnered attention from medical educators in nursing education, aiming to reduce educational costs and risks while maintaining high standards of excellence [

1,

2,

3]. As information technology rapidly advances, technologies like VR offer new pedagogical methods for nursing education[

4]. VR provides nursing students an immersive and interactive environment by recreating real clinical scenarios, offering a powerful hands-on experience without direct patient contact. This approach not only saves valuable time for clinical nursing professionals but also alleviates challenges associated with traditional patient interactions in pedagogy[

5], addressing the shortage of clinical education resources. Since the early 2000s, frequent outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases (IDs) have required nurses to effectively manage these patients to ensure patient safety. However, clinical practicum focuses on observation rather than direct nursing care due to concerns about patient rights, which limits nursing students’ ability to meet the learning objectives of clinical practicum education[

6]. To address these issues, nursing education has introduced simulation-based learning. VR simulation is more immersive than multimedia learning, resulting in better learning outcomes[

7].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses reported difficulties in caring for ventilated patients in isolated intensive care units (ICUs) and expressed the need for education to acquire knowledge and practical skills related to ventilators[

8]. Education on ID knowledge, along with practice-oriented simulation training, alleviated the fear of caring for infected patients and improved nursing competencies to prevent the transmission of IDs[

9].

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided, it could arise at any time. Therefore, it is crucial for nursing students to acquire knowledge and skills by caring for respiratory patients in preparation for future outbreaks of respiratory IDs. As millennials, the nursing students is growing up in the digital age and required engaging, innovative teaching methods to foster their interest and enthusiasm for learning[

10]. Current immersive VR programs mainly focus on simple skills such as blood transfusion, catheterization[

11,

12], and donning protective equipment, but there is a growing demand for programs addressing more complex scenarios[

13]. Thus, it is essential to develop practical nursing education for comprehensive care of patients with respiratory infections in complex situations.

Building on the experiences of new nurses who dealt with COVID-198 and a survey on nursing students’ educational needs regarding emerging respiratory IDs[

14], we aimed to develop immersive Virtual reality (VR) educational program for nursing students and explore the process of developing it.

2. Materials and Methods

This research was to develop immersive Virtual reality (VR) program for nursing students and explore the process of developing it. We developed the VR program following the five steps of the analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (ADDIE) model.

2.1. Analysis

To assess learner’s need, we developed the questionnaire via the expert, literature review to identify educational needs for a program focused on emerging infectious diseases.

2.2. Design

The learning objectives were established based on the needs assessment (

Table 1). We developed the scenarios following the guidelines of the International Nursing Association for Clinical Simulation and Learning (INACSL)[

15]. To meet the learning objectives, we developed three domains: (a) infection/contamination, (b) patient safety, and (c) patient care competency. The scenarios were designed to achieve the learning objectives as outlined in the scenario flowchart. We consulted two educational experts and two clinical experts caring for COVID-19 patients to verify the content’s accuracy.

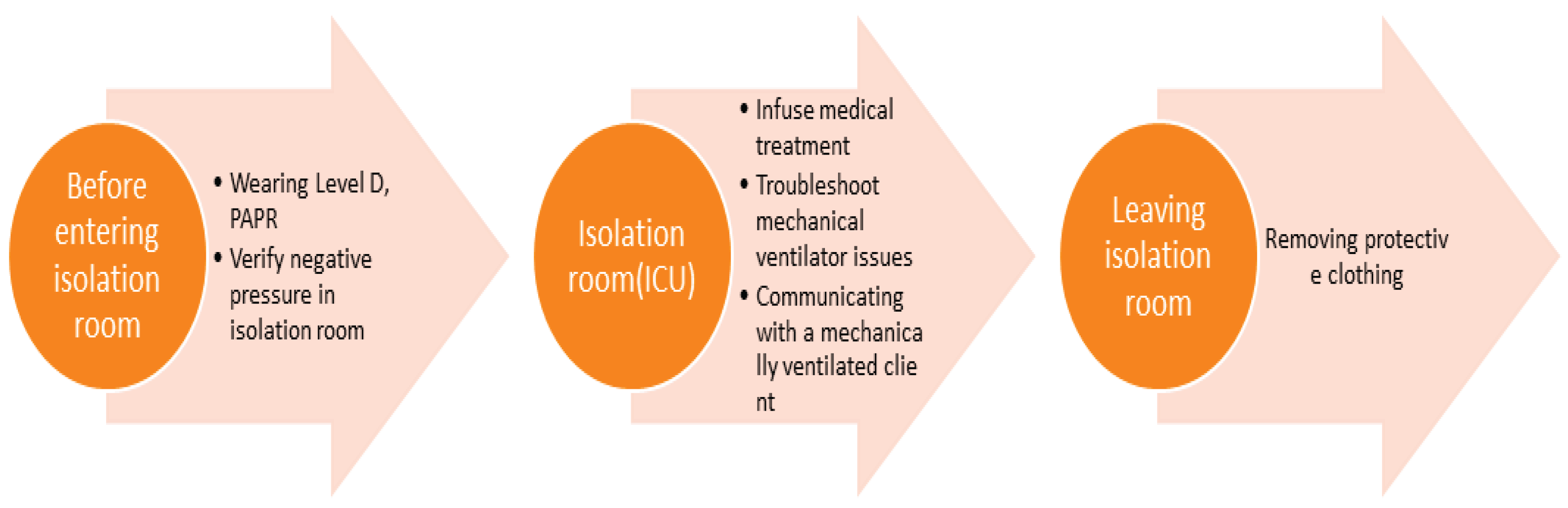

We divided the VR environments in the storyboard into the protective equipment fitting room, the isolation ICU, and the protective equipment changing room, following the sequence of the scenario (

Figure 1). The storyboard was organized so that the nurse begins in the protective equipment fitting room, moves to the isolation ICU, and provides assessment and care.

2.3. Development

We developed the VR content using a 3D VR headset with two handheld controllers (Oculus Quest 2), dividing the program into final practice and evaluation phases. The content involved using the Oculus Quest 2 headset and controllers to enhance immersion. The device features the spec details, including high resolution, refresh rate, display viewing angle, and lightweight design,16 reducing discomfort such as cybersickness. The content was developed using the Unity 3D platform, based on Oculus Quest 2, with a first-time learning duration of 15–20 min.

2.4. Implementation and Evaluation

The developed VR program was implemented and evaluated by the leaner (nursing student) and the expert.

2.5. Expert Evaluation

For the expert evaluation, we used the heuristic evaluation tool for VR applications (VRA) developed by Sutcliffe and Gault. It is recommended that the number of heuristic evaluators be between 3 and 5. The VRA tool consists of 12 questions, each evaluated on a scale from 0 (no usability problem) to 4 (usability problem that must be fixed). If two or more experts assess a heuristic problem and rate its severity as 4 or higher, it is selected as an issue to be addressed in the improvements. The total score is then converted into a grade. We used the total score to identify which items had usability issues that needed fixing. The tool is scored on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1 denotes poor quality and 7 indicates excellent quality [

17].

2.6. Learner Evaluation

To evaluate the usability of the developed content, we assessed immersion, presence, and satisfaction. After using the VR educational content, learners completed a post-survey.

To assess learner convenience, this study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 23-01-0205) and collected data on June 10, 2023. Participants were recruited through online social networking sites (SNS) by explaining the study’s purpose and methods. They were 25 fourth-year nursing students who voluntarily consented to the training and survey on the day of the training.

To ensure participants’ ethical protection, a research assistant explained the study’s purpose, procedures, anonymity, and right to withdraw participation before conducting the survey. Participants were informed that the collected data would be coded and anonymized to maintain confidentiality, and then stored for three years before being destroyed.

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 21.0 to calculate frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations.

2.6.1. Immersion

To assess immersion, we used the Flow Short Scale developed by Engeser and Rheinberg[

18], which was translated into Korean and validated by Yoo and Kim[

19]. The tool uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree). The tool includes 10 questions, 6 related to performance proficiency and 4 related to immersion in a given activity, with higher scores indicating deeper immersion. The Cronbach’s α was .84 in Yoo and Kim[

19] and .83 in this study.

2.6.2. Presence

We assessed presence using a tool developed by Chung and Yang for 3D video evaluation[

20]. The subdomains of this tool are perceived characteristics, impression, and presence. In this study, we used 19 items from the presence domain, with modifications to suit the study. These 19 items included 7 for spatial involvement, 4 for temporal involvement, 5 for immersive dynamism, and 3 for immersive presence, using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), where higher scores indicate a greater sense of presence. At the time of development, the tool had a Cronbach’s α ranging from .81 to .92, and in this study, it was .85.

2.6.3. Education Satisfaction

We assessed education satisfaction using an instrument developed by Cho[

21] and adapted by Yu[

22] for nursing students. The instrument consists of 3 questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree), where higher scores indicate greater education satisfaction. The reliability of the instrument at the time of development was Cronbach’s α of .81, and in this study, it was .66.

3. Results

In the scenario, the patient is infected with COVID-19 and is in an isolated ICU. The nurse, wearing protective equipment, administers antiviral medications, troubleshoots ventilator issues, and safely removes the protective equipment (

Table 1).

3.1. Developed VR Program

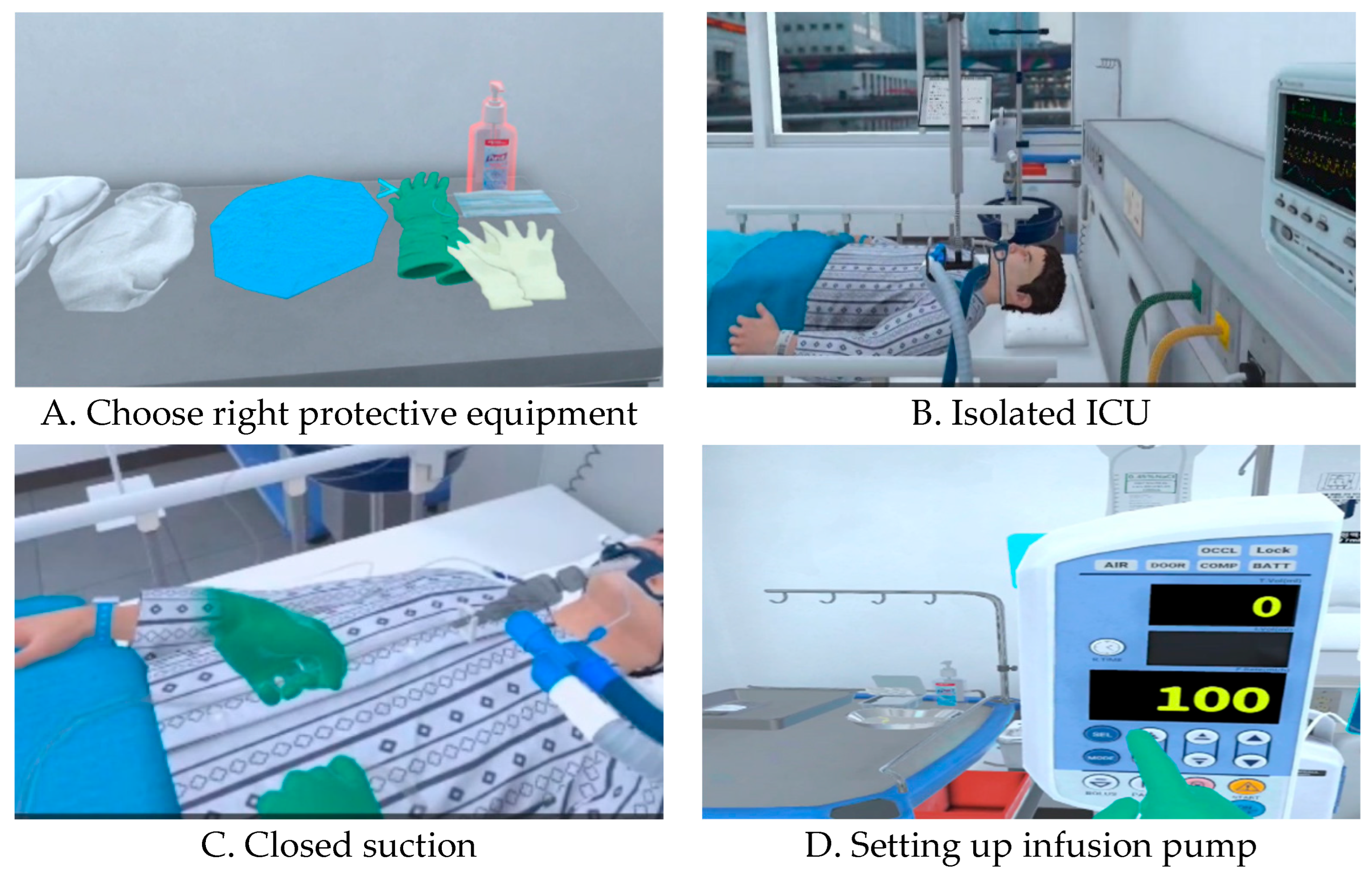

The VR program enhanced immersion by providing users with various interactive opportunities through the use of a 3D VR headset with two handheld controllers (Oculus Quest 2). Visual feedback was provided using arrows and orange inversions (

Figure 2A), while auditory feedback included real world sounds, such as voice prompts for the next screen, sounds from real devices, and the sound of an automatic door opening, to create a realistic intensive care unit environment (

Figure 2B). To enable tactile perception, the VR controller was used as a haptic device, allowing users to interact with displayed objects by touching them, such as closed suction (

Figure 2C). When pressing the IV pump button, users could feel tactile stimuli, simulating the sensation of pressing a real button (

Figure 2D), thereby maximizing tactile feedback. To extend the learner’s knowledge, they could calculate a dose or choose an answer to a patient’s question.

Learners could choose between a practice mode and an assessment mode. After sufficient practice, they could progress to the assessment mode to check their learning. At the end of the VR program, users could review their errors (e.g., the order of putting on and taking off protective equipment, incorrect quiz answers) on the final screen, maximizing the learning effect.

3.2. Implementation and Evaluation

After running the VR content, 25 fourth-year nursing students completed a survey and debriefing after a 20-minute break. Before running VR program, we provided orientation on the scenario content and training on the mechanical use of the device. The scenario content orientation included explaining the goals of the VR content, scenario flow. Training on device use covered how to operate the Oculus Quest 2, stay within safety boundaries, signal to stop if they felt dizzy, and work in pairs to monitor each other and call for help if necessary. Participants worked on the content for an average of 15–20 minutes.

3.2.1. Learner Evaluation

After running VR program, participants evaluated it. As shown in

Table 2, participants scored 42.28 ± 2.37 out of 50 for immersion, 81.36 ± 7.32 for presence, and 13.48 ± 1.26 out of 15 for satisfaction.

3.2.2. Expert Evaluation

The program was evaluated by two virtual reality program development experts and two nursing education experts with experience in the use of virtual reality programs.

The average score was 6.5, with each question ranging from 6 to 7 points. All four experts rated the content as usable, with suggestions to clearly highlight arrows pointing to objects and to slow down the speed of the user’s spatial movement, as fast movement could cause dizziness. The item “Close coordination of action and representation” received the highest ratings, while “Consistent departures” and “Clear turn taking” received the lowest ratings; however, the extent of required revision was deemed insufficient(

Table 3).

To improve nursing students’ ability to respond to patients with respiratory infections, we developed an immersive VR-based nursing program focused on patients with respiratory infections. It replicated the real environment of an isolation intensive care unit to enhance fidelity and was configured based on the needs survey to ensure the complexity level was appropriate for fourth-year students. Additionally, appropriate cues were inserted during the program, which allowed learners to review related materials and integrate knowledge and experience through debriefing. The program was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, a time when the need for prepared healthcare workers was urgent, driven by learners’ expectations and the demand for diverse educational experiences in a rapidly changing educational environment. We built a 3D model of an environment similar to an isolation room for patients with respiratory IDs, where learners could perform nursing care in each of the four areas using an Oculus Quest 2 Head-mounted display and controller while taking quizzes to review relevant sections. While most existing immersive VR programs have been designed for procedural skill practice [

11,

12,

13,

23,

24], this program differs by incorporating not only procedural learning but also preparing learners for entering the isolation ICU and providing care for critically ill, isolated patients. This expands the content beyond the traditional infection control education for isolated patients [

25].

The immersion level of the participants in this study was 42.28 out of 50 points. Immersion refers to the state of experiencing optimal effects by becoming deeply engaged in an activity. Learners experience immersion when the difficulty level of a task aligns with their sense of challenge[

26]. It is believed that immersion was high in this study because the program was developed based on the learners’ educational needs[

14], and their preparation for the challenge of caring for COVID-19 patients with respiratory infections in the ICU was enhanced through lectures, videos, and question-and-answer sessions during the pre-briefing period. This preparation helped balance task difficulty with challenge, facilitating participation in the program. Additionally, the headset and haptics stimulated the visual and tactile senses, enhancing immersion and providing feedback based on the learner’s interaction with objects[

27]. This likely contributed to the greater immersion experienced by participants. Research supports this, suggesting that headset VR programs are more immersive because they use the body’s movements to create a more realistic experience[

28].

However, learners participating in simulations may lose their sense of immersion when they feel they are being observed[

29] or when they perceive the situation as unreal[

30]. Furthermore, the high immersion rate in VR simulations may be due to learners’ autonomy. They can participate without being watched, freely use the program at any time, and are motivated to learn through the engaging nature of the medium[

12]. A previous study[

24] also reported that realistic settings, where learners are completely disconnected from the real environment, enhance immersion. Furthermore, the ability to receive feedback on their performance likely motivated learning and increased immersion.

Novac[

31] explained that presence is related to selective perception and attentional factors during the recognition phase and is associated with exploratory attention, which influences learning performance. In this study, the score for presence was 81 out of 95. Rhu[

32] reported a mean score of 4.39 in a program involving care for neonatal ICU (NICU) patients, which is similar to the present study’s score of 4.26. This score is higher than the mean score of 130 out of 190 for the simple skill of transfusion in a prior study,12 which evaluated presence using a different tool. Both the past study[

12] and the present one show that presence is enhanced when spatial and temporal involvement—a sense of dynamism that encourages users to move their bodies—are combined with visual, auditory, and tactile elements that mimic the real world. To increase the realism of the program, we also used a 3D model of a real hospital setting, photographed medical devices and supplies, and augmented the presence of VR by allowing learners to move around the space and observe the objects. Tactile presence was provided by using vibration when the learner operated an IV pump. Additionally, we employed realistic images and sounds associated with real items, such as mixing real TPN solutions, injecting an IV bolus through a real 3-way, and alarms from monitors or devices.

Education satisfaction with this program was 13 out of 15. As education satisfaction in VR programs is influenced by instructional design and immersion, it is essential to design instruction that promotes learners’ focus and engagement, as well as to select a medium that facilitates immersion[

33]. A previous study also showed that learners who trained using VR were more satisfied with the training[

34], supporting our findings. However, immersive VR education has side effects, such as difficulty operating the device and cybersickness[

12,

24,

32] and some participants in our study reported issues with device operation and motion sickness. To minimize these challenges, it is essential to allow sufficient practice with the HMD and controllers before engaging with the VR program to prevent difficulties arising from inexperience.

The VR program in our study meets the needs of digital-native students and offers advantages such as reduced space requirements and ease of use compared to conventional simulation education. However, side effects may hinder its broader use in educational settings. Therefore, the program should be improved through a convergent approach between technology and education.

4. Discussion

This study developed an immersive VR training program based on the nursing of patients with respiratory infections and evaluated its educational utility. This program goes beyond conventional, skill-focused VR training to include a recreation of the isolation intensive care unit environment and clinical decision-making elements, allowing participants to experience complex clinical situations. Results showed that learners’ engagement (42.28/50), sense of presence (81.36/95), and educational satisfaction (13.48/15) all achieved mid- to high-level scores, confirming the program’s potential educational effectiveness. These results suggest that VR-based training can substantially contribute to developing future nursing professionals equipped to respond to infectious diseases.

First, the high level of engagement is closely related to the program’s design based on learner needs assessment. Learners experienced a balance of challenge and task difficulty as they pre-trained on complex tasks required for COVID-19 intensive care, such as donning and doffing personal protective equipment, responding to ventilator alarms, and administering antiviral medications. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating that the “challenge-skill balance” proposed by Flow theory maximizes engagement. Furthermore, the provision of multisensory feedback (visual, auditory, and tactile) enhanced the sense of realism and expanded the learner’s interactive experience, supporting previous research demonstrating the high immersive effects of headset-based VR.

Second, the high level of presence appears to be the result of a complex interplay of elements that enhance fidelity, including a 3D space that precisely models the actual clinical environment, auditory stimulation based on actual medical device sounds and alarms, and tactile stimulation utilizing vibration feedback. These multisensory interactive elements induce a sense of “presence” in the learner’s environment, consistent with reports that spatial and temporal engagement are particularly associated with improved learning outcomes. This relatively higher level of presence than that reported in existing simple technical VR programs underscores the importance of VR training based on complex clinical scenarios.

Third, the high level of training satisfaction is likely due to the program structure (practice mode–assessment mode) that enabled learner participation, immediate feedback on errors, and the practical clinical context of isolation ward nursing, which enhanced learning motivation. Previous studies have reported that VR training can increase learner interest and satisfaction and contribute to improved clinical performance, supporting the results of this study.

However, this study also identified side effects and operational limitations of immersive VR training. Some learners reported difficulty operating the Oculus Quest 2 or experiencing dizziness (cybersickness) due to inexperience with the device, a problem repeatedly raised in previous studies. In particular, movement speed, visual distance, and user adaptation are known to be factors inducing motion sickness, necessitating adjustments to the program’s movement speed and enhanced user guidance. Furthermore, because this program focused on a specific disease (COVID-19) based on a physical pandemic, its potential for expansion to various respiratory infection situations should be considered.

This study also has several limitations in terms of experimental design. First, the single-group posttest design makes it difficult to clearly verify the effectiveness of the VR program. Second, the limited number of learners (25) and the study conducted at a single university limit the generalizability of the results. Third, because immersion, presence, and satisfaction were based on subjective assessment tools, we were unable to directly verify whether they actually improved clinical performance competency.

Nevertheless, this study is significant in that it demonstrates the feasibility of developing a high-fidelity VR nursing education program that embodies high-quality clinical situations and integrates multisensory interaction based on a pre-assessment of learner needs in the high-risk and high-difficulty area of respiratory infection patient care. This demonstrates the potential for developing programs that transcend the limitations of existing skill-focused VR training and encompass complex competencies such as clinical thinking, communication, and patient safety management.

Future research should utilize a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design to verify the actual effectiveness of VR training in improving knowledge, skills, and clinical judgment compared to traditional lecture- or practice-based training. Furthermore, systematic analysis should be conducted to examine the impact of VR learning experiences on long-term knowledge retention, whether the benefits accumulate with repeated learning, and how to strengthen the debriefing structure. Finally, expanding the scenarios to include various infectious disease situations (e.g., RSV, SARS-like viruses, etc.) and incorporating AI-based adaptive feedback could create a more personalized learning environment.

5. Conclusions

This study was to develop immersive VR program for nursing students and explore the process of developing and evaluate its usefulness in clinical practicum education. Participants scored 42.28 ± 2.37 out of 50 for immersion, 81.36 ± 7.32 for presence, and 13.48 ± 1.26 out of 15 for satisfaction. This score is higher than the mean score of 130 out of 190 for the simple skill of transfusion in a prior study.12 With prior research, the integration of real- world mimicking multisensory cues (visual, auditory, tactile) with movement-inducing dynamics significantly enhanced participants’ sense of presence.

The VR program was revealing a moderate-to-high level of immersion, presence, and satisfaction, thus confirming the program’s usefulness. Since the VR program aimed to enhance the accumulation of skills and knowledge necessary for nursing patients with respiratory IDs, further research is needed. Specifically, a study with a pre/post-experimental group design and a control group is required to verify the VR program’s effectiveness. Given that the level of knowledge retention may differ over time compared to conventional lecture-based classes, future research should include a comparative study to assess the retention of knowledge over time facilitated by VR experiences, and repeated learning attempts.

Author Contributions

EJJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original draft preparation; LSS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-Original draft preparation; EKL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No.2020R1F1A1071733).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study design was approved by the Catholic Kwandong University Institution Review Board (CKU-23-01-0205, date 9 June 2023) in Korea. All of the respondents agreed to participate voluntarily before completing the questionnaire. All responses were kept strictly confidential for research purposes only, and the results did not personally identify respondents.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before answering the questions.

Data Availability Statement

Availability data and material. The dataset used and /or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding upson reansonable request. .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Atli K, Selman WR, Ray A. Virtual reality in neurosurgical education: modernizing the medical classroom. Neurosurgery. 2020;67 Suppl 1:51..

- Kyaw BM, Saxena N, Posadzki P, Vseteckova J, Nikolaou CK, George PP, et al. Virtual reality for health professions education: systematic review and meta-analysis by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e12959.

- Yu MH, Yang WY. The application effect of virtual reality technology in the teaching of nursing students in rehabilitation department. China High Med Educ;2020:103-4.

- Zhao J, Lu Y, Zhou F, Mao R, Fei F. Systematic bibliometric analysis of research hotspots and Trends on the application of virtual reality in nursing. Front Public Health. 2022;10:906715. [CrossRef]

- eeyae C, Elise CT. Faculty driven virtual reality (VR) scenarios and students perception of immersive VR in nursing education: A pilot study. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings. AMIA Symp. 2022;2022.

- So HY, Chen PP, Wong GKC, Chan TTN. Simulation in medical education. J R Coll Phys Edinb. 2019;49:52-7. [CrossRef]

- So YH. The impact of academic achievement by presence and flow-mediated variables in a simulation program based on immersive virtual reality. J Commun Des. 2016;57:55-68.

- Ji EJ, Lee YH. New nurses’ experience of caring for COVID-19 patients in South Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:9471. [CrossRef]

- Jung HJ. Development and application of self-directed simulation education program based on planned behavior theory: MERS scenario experience and nursing intention. J Humanit Soc Sci. 2018;9:1035-48.

- Huai P, Li Y, Wang X, Zhang L, Liu N, Yang H. The effectiveness of virtual reality technology in student nurse education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2024;138:106189. doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106189.

- Park S, Yoon HG. Effect of virtual-reality simulation of indwelling catheterization on nursing students’ skills, confidence, and satisfaction. Clin Simul Nurs. 2023;80:46-54. [CrossRef]

- Hyun SJ, Lee YJ. Clinical competence, confidence, presence, and learning immersion: analyzing nursing students’ learning experiences in virtual reality simulation transfusion education. J Health Simul. 2020;4:42-51. [CrossRef]

- Jeong Y, Lee H, Han JW. Development and evaluation of virtual realitysimulation education based on coronavirus disease 2019 scenario for nursing students: a pilot study. Nurs Open. 2022;9:1066-76. [CrossRef]

- Ji EJ, Lee EK. Factors influencing the educational needs and nursing intention regarding COVID-19 patient care among undergraduate nursing students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:15671. [CrossRef]

- International Nursing Association for Clinical and Simulation Learning (INACSL). Healthcare simulation standards of best practice™. https://; 2021. www.inacsl.org/healthcare-simulation-standards-ql. Accessed 13 June 2023.

- Hur HK, Jung JS. Nursing students and clinical nurses’ awareness of virtual reality (VR) simulation and educational needs of VR-based team communication and teamwork skills for patient safety: a mixed method study. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2022;22:629-45. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe A, Gault B. Heuristic evaluation of virtual reality applications. Interact Comput. 2004;16:831-49. [CrossRef]

- Engeser S, Rheinberg F. Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motiv Emot. 2008;32:158-72.

- Yoo JH, Kim YJ. Factors influencing nursing students’ flow experience during simulation-based learning. Clin Simul Nurs. 2018;24:1-8. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ecns.2018.09.001.

- Chung DH, Yang HC. Reliability and validity assessment in 3D video measurement. J Broadcast Eng. 2012;17:49-59.

- Cho S. Effects of the Root Cause Analysis Education Program in Improving Patient Safety Competencies of Nursing Students [unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Kyungpook National University; 2018. p. 1-110.

- Yu M, Yang M, Ku B, Mann JS. Effects of virtual reality simulation program regarding high-risk neonatal infection control on nursing students. Asian Nurs Res. 2021;15:189-96.

- Kim KJ. Development and evaluation of infection control education contents using virtual reality. J Digit Contents Soc. 2023;24:2711-7. [CrossRef]

- Lau ST, Siah RCJ, Dzakirin Bin Rusli KDB, Loh WL, Yap JYG, Ang E, et al. Design and evaluation of using head-mounted virtual reality for learning clinical procedures: mixed methods study. JMIR Serious Games. 2023;11:e46398. [CrossRef]

- Han JW, Joung JW, Kang JS, Lee H. A study of the educational needs of clinical nurses based on the experiences in training programs for nursing COVID-19 patients. Asian Nurs Res. 2022;16:63-72. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow-the psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row; 1990.

- Kim HY. Developing virtual reality and haptic-based surgical nursing training content. Korean Society of Nursing Science Fall Meeting Proceeding, 39; 2022.

- Radianti J, Majchrzak TA, Fromm J, Wohlgenannt I. A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Comput Educ. 2020;147:103778. [CrossRef]

- Shearer JN. Anxiety, nursing students, and simulation: state of the science. J Nurs Educ. 2016;55:551-4. [CrossRef]

- Yeo HN, Park M, Je NJ. Evidence-based simulation training education experience of nursing students. J Korean Soc Simul Nurs. 2020;8:39-50. [CrossRef]

- Novak TP, Hoffman DL, Yung YF. Measuring the customer experience in online environments: a structural modeling approach. Mark Sci. 2000;19:22-42.

- Rhu JM. Effects of VR Simulation-Based Infection Control Education Program for Nurses in Neonatal Intensive Care Units: Focusing on High-Risk Medication and Treatment [Master’s thesis]. Kyoung Sang University; 2023.

- Park SY, Kim JH. Instructional design and educational satisfaction for virtual environment simulation in undergraduate nursing education: the mediating effect of learning immersion. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:673. [CrossRef]

- Chae M. Comparison of the effectiveness of virtual reality, simulation, and lecture-style education methods in practice education. J Humanit Soc Sci. 2021;12:1283-94. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).