Submitted:

23 December 2025

Posted:

24 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Choosing Synthetic Mathematicians for the Conference

- Field identification: "Which field of mathematics does this problem belong to?"

- Approach enumeration: "What theorems and approaches should be taken into consideration to solve this problem?"

- Expert identification: "Write 5 leading mathematicians from each field that are experts in each approach."

- Team selection: "Choose a team of 12 mathematicians that are most likely to arrive at a robust proof to this problem."

2.2. Conference Generation via Prompting

2.2.1. Prompt 1: Conference Initiation

2.2.2. Discourse State Assessment

2.2.3. Prompt 2: Consolidation on Consensus

32.4. Prompt 3: Actionable Plan on Discord

23. Proof Self-Verification via Simulated Peer Review

2.3.1. Prompt 4: Peer Review Initiation

2.3.2. Prompt 5: Collaborative Repair

2.3.3. Iteration Protocol

24. Active Moderation: The Conference Chair Role

- Real-time error tracking: Maintaining a running list of mathematical errors identified either by the operator or by the synthetic mathematicians themselves

- Proof coherence verification: Ensuring no proposed subtask from actionable plans is skipped across conversation turns

- Strategic intervention timing: Deciding when to request peer review, when to demand collaborative repair, and when to consolidate progress

3. Results

3.1. Proof Derivation Failure with Direct Prompting

3.2. Synthetic Mathematical Conference Produces the Correct Proof

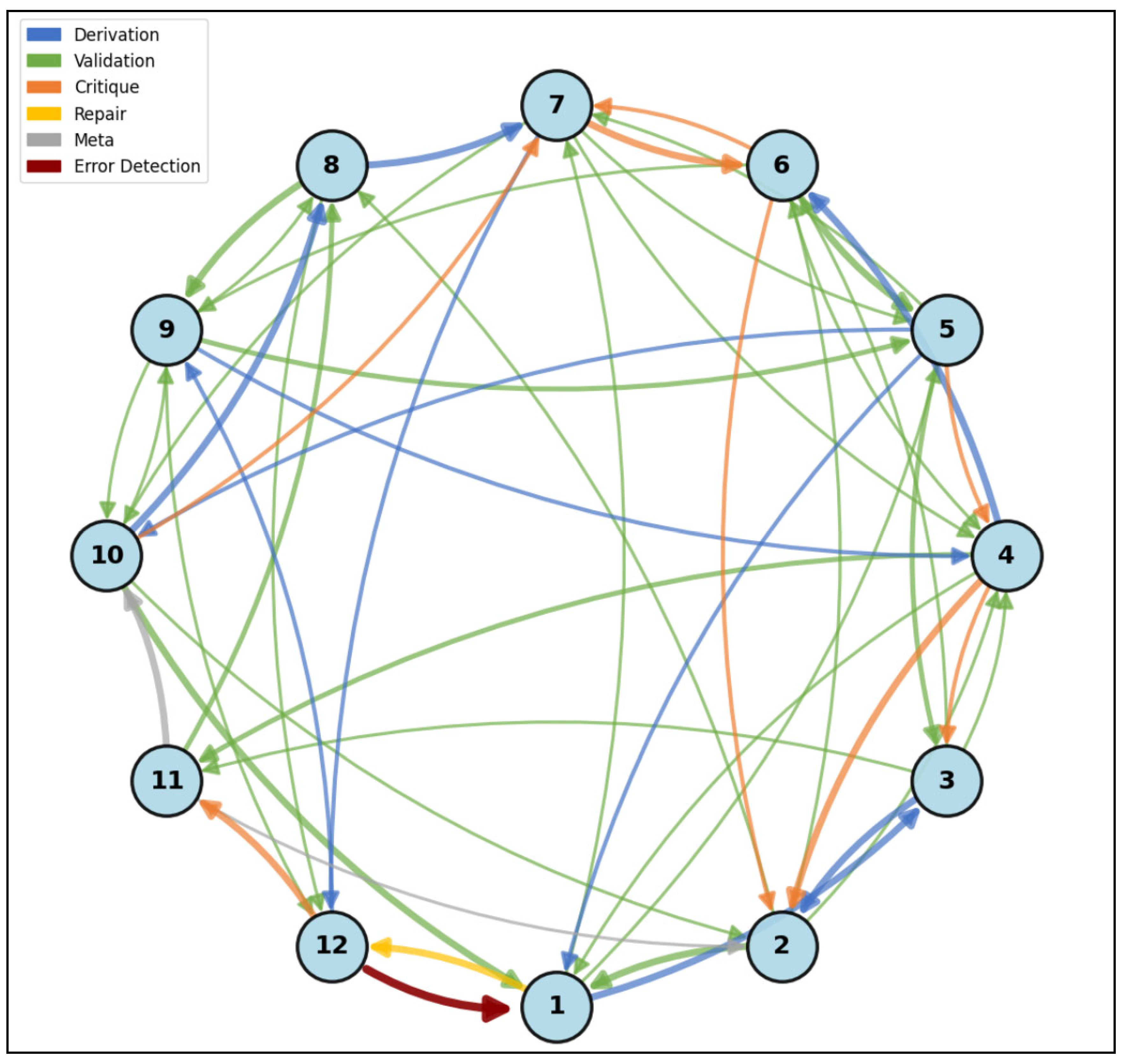

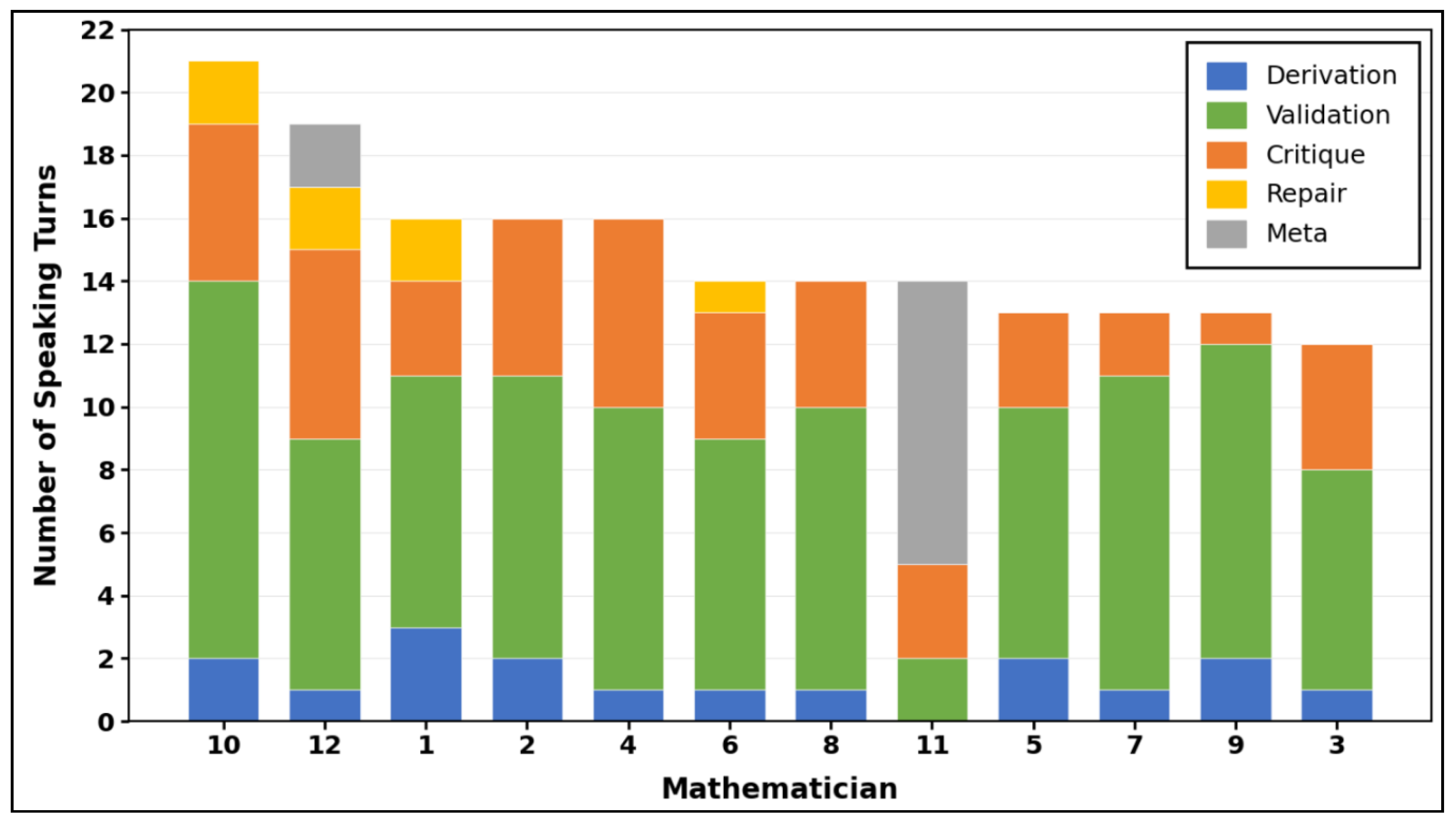

3.2.1. Quantitative Overview of the Synthetic Conference

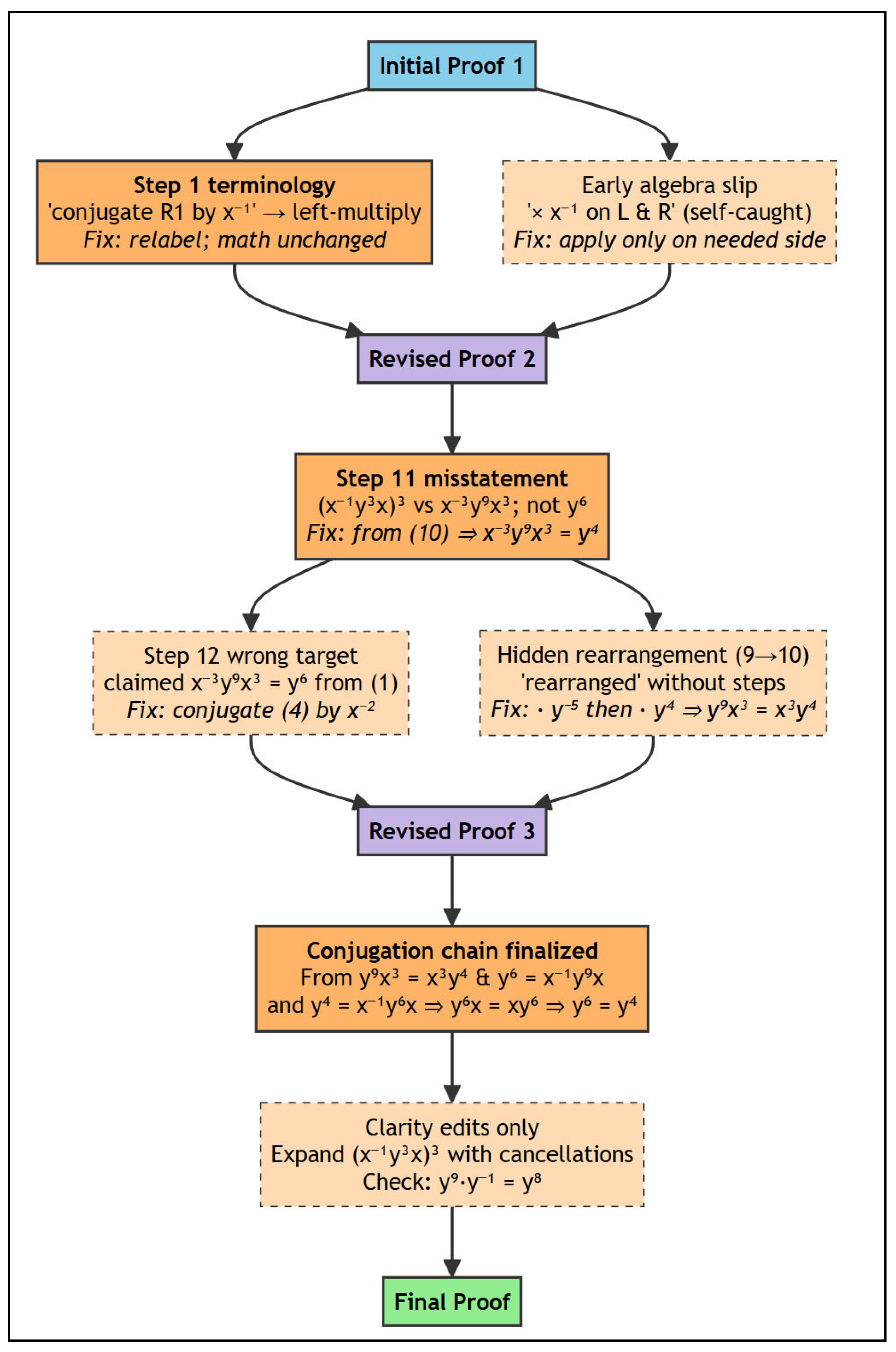

- Cycle 1 (lines 0–2172, 80 turns): Initial derivation and first review; detected a terminology error and a self-caught algebra slip

- Cycle 2 (lines 2172–2985, 85 turns): Weak spot analysis; detected 2 critical algebraic errors

- Cycle 3 (lines 2985–3886, 16 turns): Final validation; no new errors detected

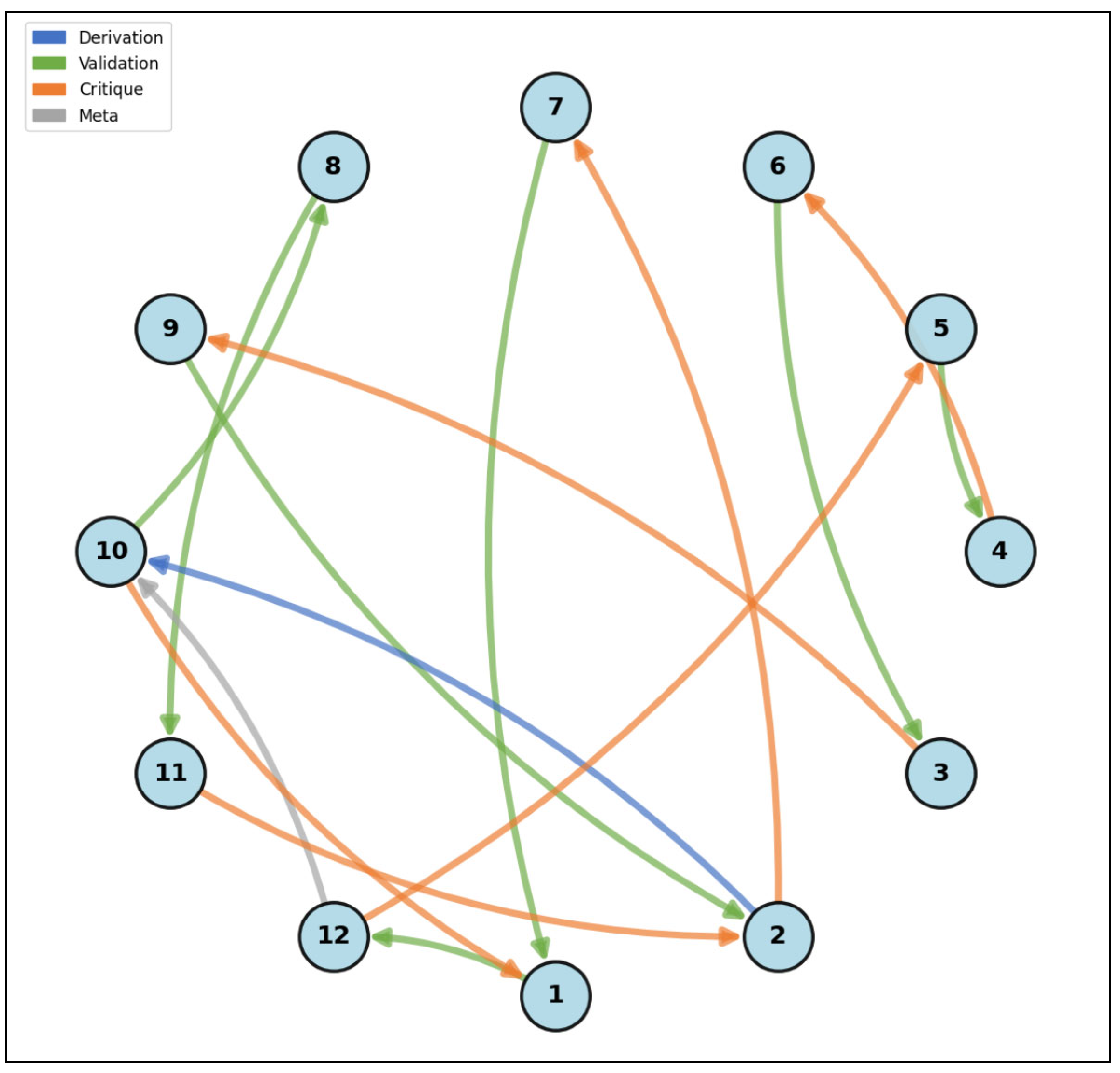

- Derivation: Algebraic manipulation and proof steps that advance the argument

- Validation: Confirming correctness or endorsing another mathematician's work

- Critique: Scrutinizing claims, raising concerns, and checking for errors

- Repair: Proposed fixes for identified errors

- Meta: Process commentary, framing, and intuition without direct calculation

3.2.2. Cycle 1: Initial Derivation & First Review

3.2.3. Cycle 2: Critical Error Detection

3.2.4. Cycle 3: Final Validation

3.3. Predictors of Error Detection

- Terminology error (Step 1): Caught by Mathematician 12, whose expertise in algorithmic methods demand precise language.

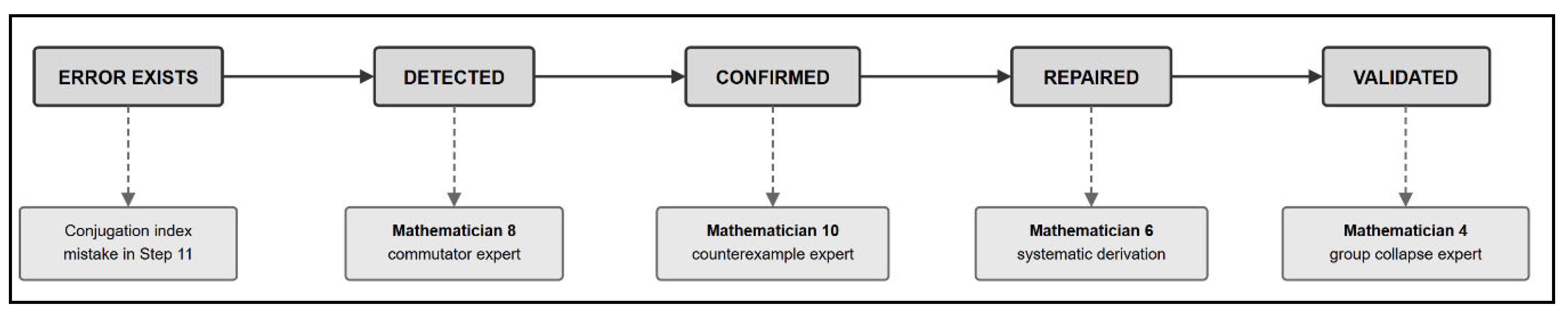

- Conjugation index error (Step 11): Caught by Mathematician 8, whose expertise in commutator analysis is mathematically intertwined with conjugation operations. Mathematician 10 immediately confirmed the error.

3.4. Emergent Collective Intelligence

3.4.1. Cycle 1: Exploratory Derivation

3.4.2. Cycle 2: Critical Error Detection

3.4.3. Cycle 3: Consensus

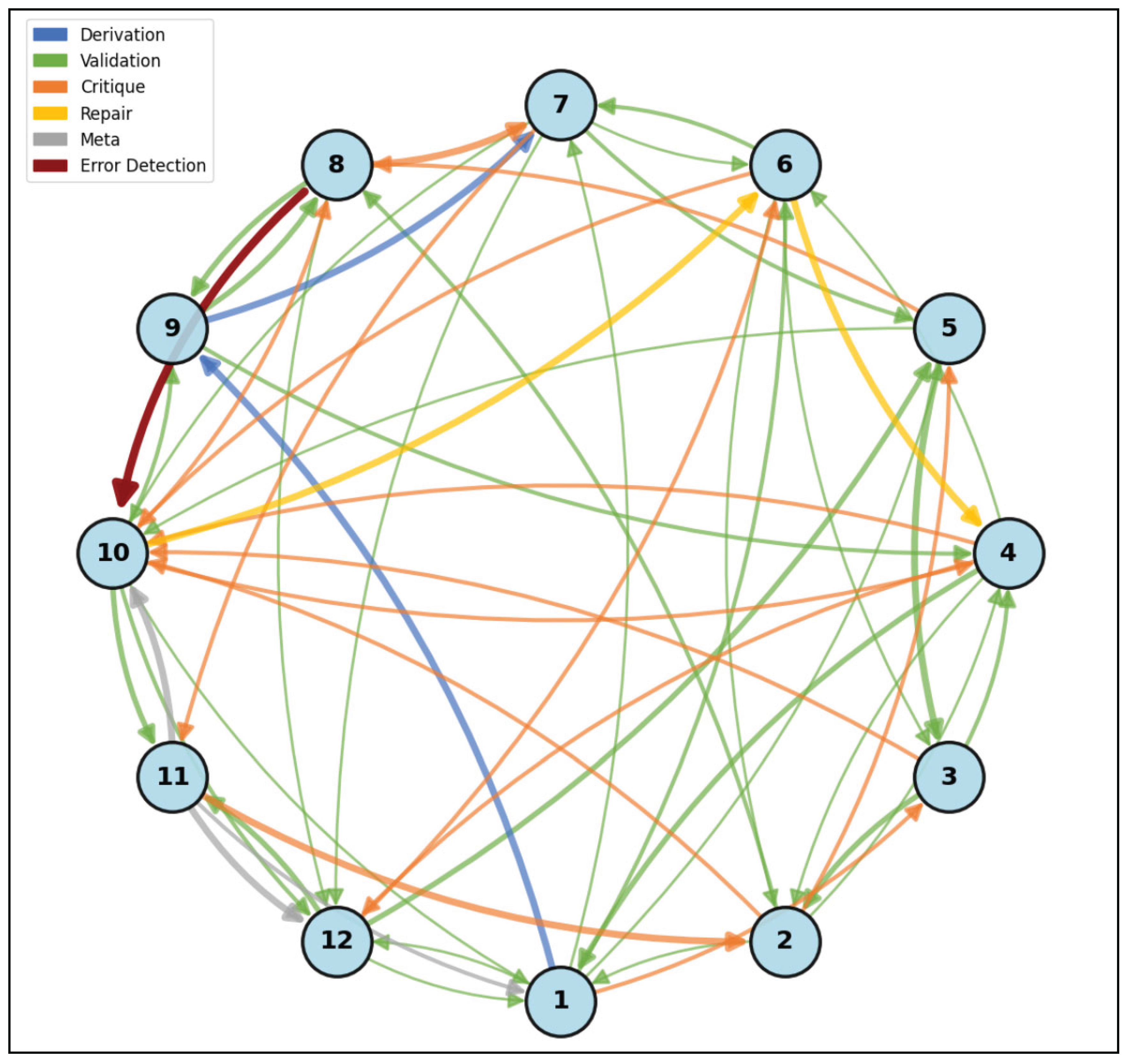

3.5. Phase Transition from Stochastic Verification to Ordered Consensus

3.5.1. Transition Matrix Construction

4.5.2. Transition Entropy

4.5.3. Effective Number of Next Speakers

4. Discussion

4.1. Capability Amplification via Interaction Structure

4.2. Substrate-Independence and the Functionalist Principle

4.3. Mapping Biological Hallmarks of Collective Intelligence

4.4. Creativity as an Underestimated Benchmark for LLM Capability

4.5. Limitations and Human-AI Coupling

4.6. Implications and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Appendix A: Failed Direct Prompting Attempt with Error Analysis

Appendix B: The Final Correct Proof of Yu Tsumura's 554th Problem

Appendix C: Error Detection and Repair via Synthetic Peer Review

- y⁴ = x⁻¹y⁶x (from step 3)

- x⁻³y⁹x³ = y⁴ (from step 10)

- Step 11: x⁻³y⁹x³ = y⁴ (from step 10: y⁹x³ = x³y⁴, then left-multiply by x⁻³)

- Step 12: x⁻²y⁶x² = x⁻³y⁹x³ (by conjugating step 4 by x⁻²)

- Step 13: x⁻²y⁶x² = y⁴ = x⁻¹y⁶x, which implies y⁶x = xy⁶

References

- W. James, The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt, New York (1890).

- M. Levin, Technological approach to mind everywhere: An experimentally-grounded framework for understanding diverse bodies and minds. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 16, 768201 (2022). [CrossRef]

- R. Noble, D. Noble, Harnessing stochasticity: How do organisms make choices? Chaos 28, 106309 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.A. & Levin, M. (2023). The collective intelligence of evolution and development. Collective Intelligence, 2(2). [CrossRef]

- D. Guo et al., DeepSeek-R1 incentivizes reasoning in LLMs through reinforcement learning. Nature 645, 633–638 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Z. Shao et al., DeepSeekMath-V2: towards self-verifiable mathematical reasoning. Preprint (2025). https://github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-Math-V2.

- B. Naskręcki, K. Ono, Mathematical discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature Physics (2025). [CrossRef]

- S. Mirzadeh et al., GSM-Symbolic: understanding the limitations of mathematical reasoning in large language models. arXiv Preprint (2024).

- P. McMillen, M. Levin, Collective intelligence: a unifying concept for integrating biology across scales and substrates. Communications Biology 7, 378 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Garnier, J. Gautrais, G. Theraulaz, The biological principles of swarm intelligence. Swarm Intelligence 1, 3–31 (2007). [CrossRef]

- M. Levin, Bioelectrical approaches to cancer as a problem of the scaling of the cellular self. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 165, 102–113 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D. Moore, S.I. Walker, M. Levin, Cancer as a disorder of patterning information: computational and biophysical perspectives on the cancer problem. Convergent Science Physical Oncology 3(4), 043001 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M.J.C. Hendrix, E.A. Seftor, R.E.B. Seftor, J. Kasemeier-Kulesa, P.M. Kulesa, L.M. Postovit, Reprogramming metastatic tumour cells with embryonic microenvironments. Nature Reviews Cancer 7, 246–255 (2007). [CrossRef]

- J.-F. Rajotte et al., Synthetic data as an enabler for machine learning applications in medicine. iScience 25, 105331 (2022). [CrossRef]

- G. Fagiolo, A. Moneta, P. Windrum, A critical guide to empirical validation of agent-based models in economics: methodologies, procedures, and open problems. Computational Economics 30, 195–226 (2007). [CrossRef]

- L. Canese et al., Multi-agent reinforcement learning: a review of algorithms, applications, and challenges. Applied Sciences 11, 4948 (2021).

- K. Swanson, W. Wu, N.L. Bulaong, J.E. Pak, J. Zou, The Virtual Lab of AI agents designs new SARS-CoV-2 nanobodies. Nature 646, 716–723 (2025). [CrossRef]

- H. Su et al., Many heads are better than one: improved scientific idea generation by a LLM-based multi-agent system. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL, 2025), pp. 28201–28240.

- J. Choi, D. Kang, Y. Mao, J. Evans, Academic Simulacra: forecasting research ideas through multi-agent LLM simulations. In Proceedings of the ACM Collective Intelligence Conference (ACM, 2025).

- S. Frieder, W. Hart, No LLM solved Yu Tsumura's 554th problem. arXiv Preprint (2025). https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.03685.

- A. W. Woolley, C. F. Chabris, A. Pentland, N. Hashmi, T. W. Malone, Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 330, 686–688 (2010). [CrossRef]

- J. Wei et al., Emergent abilities of large language models. Transactions on Machine Learning Research (2022).

- J. Wei et al., Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022).

- D. Noble, The Music of Life: Biology Beyond the Genome (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2006).

- D. C. Dennett, Consciousness Explained (Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1991). [CrossRef]

- S. Dehaene, Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts (Viking, New York, 2014).

- W. M. Wheeler, The ant-colony as an organism. Journal of Morphology 22, 307–325 (1911).

- R. K. Baltzersen, What is collective intelligence? in Cultural-Historical Perspectives on Collective Intelligence: Patterns in Problem Solving and Innovation (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022), pp. 1–26.

- E. Bonabeau, G. Theraulaz, J.-L. Deneubourg, Quantitative study of the fixed threshold model for the regulation of division of labour in insect societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 263, 1565–1569 (1996). [CrossRef]

- C. Anderson, J. J. Boomsma, J. J. Bartholdi, Task partitioning in insect societies: bucket brigades. Insectes Sociaux 49, 171–180 (2002). [CrossRef]

- I. D. Couzin, J. Krause, N. R. Franks, S. A. Levin, Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature 433, 513–516 (2005). [CrossRef]

- J. Surowiecki, The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies, and Nations (Doubleday, New York, 2004).

- S. Pandit, A. Xu, X.-P. Nguyen, Y. Ming, C. Xiong, S. Joty, Hard2Verify: a step-level verification benchmark for open-ended frontier math. arXiv preprint (2025).

- J. P. Guilford, The Nature of Human Intelligence (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1967).

| Mathematician | Stated Expertise |

| 1 | Master of relation manipulation in groups; techniques for handling generators and relations directly applicable |

| 2 | Expert in combinatorial group theory; would immediately recognize patterns in the symmetric relations |

| 3 | Specialist in groups with few generators and relations; has solved many similar "prove trivial" problems |

| 4 | Deep understanding of how relations force group collapse; expert at finding hidden consequences |

| 5 | Master of systematic coset enumeration and relation manipulation by hand |

| 6 | Expert at systematic derivation of consequences from relations |

| 7 | Deep understanding of coset enumeration that translates to paper proofs |

| 8 | For commutator analysis if the solution requires proving commutativity first |

| 9 | Expert on periodic groups; would quickly identify if the relations force finite exponent |

| 10 | Master of counterexamples; would know all the tricks that make groups non-trivial |

| 11 | Geometric intuition for group presentations; good at finding unexpected approaches |

| 12 | Deep understanding of relation consequences invaluable for systematic derivation |

| Mathematician | Stated Expertise | Turns | Key Contributions |

| 10 | counterexamples | 21 | Confirmed Step 11 error; validated repair |

| 12 | algorithmic methods | 19 | Caught Step 1 terminology error; algorithmic verification |

| 1 | relation manipulation, free groups | 16 | Led initial relation manipulation; validated associativity |

| 2 | combinatorial group theory, symmetric relations | 16 | Verified dual symmetry; centralizer argument |

| 4 | group collapse, hidden consequences | 16 | Derived key y⁶=y⁴ identity; analyzed Step 11 error path |

| 6 | systematic derivation | 14 | Provided Step 11 fix via direct computation |

| 8 | commutator analysis | 14 | Caught Step 11 error (conjugation index) |

| 11 | geometric group theory | 14 | Geometric collapse validation; topological intuition |

| 5 | coset enumeration | 13 | Manual coset enumeration; systematic derivation |

| 7 | computational methods | 13 | Computational verification; verified Step 8 substitution |

| 9 | periodic groups, finite exponent | 13 | Periodic group analysis; confirmed exponent constraints |

| 3 | few generators/relations | 12 | Validated exponent additivity; noted Step 10 rearrangement |

| Cycle | Transition Entropy | Effective Next Speakers | Interpretation |

| 1 | 1.97 bits | 3.9 | Exploratory derivation |

| 2 | 2.27 bits | 4.8 | Chaotic verification |

| 3 | 0.25 bits | 1.2 | Ordered consensus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).