Submitted:

22 December 2025

Posted:

25 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Objectives

2. Related Work

2.1. Cracks Segmentation in 2D

2.1.1. Classical Image Processing Methods

2.1.2. Machine Learning Methods

2.2. Cracks Segmentation in 3D

2.3. Shape Description and Registration

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Specimens Preparation

3.2. Data Acquisition

3.3. Methods

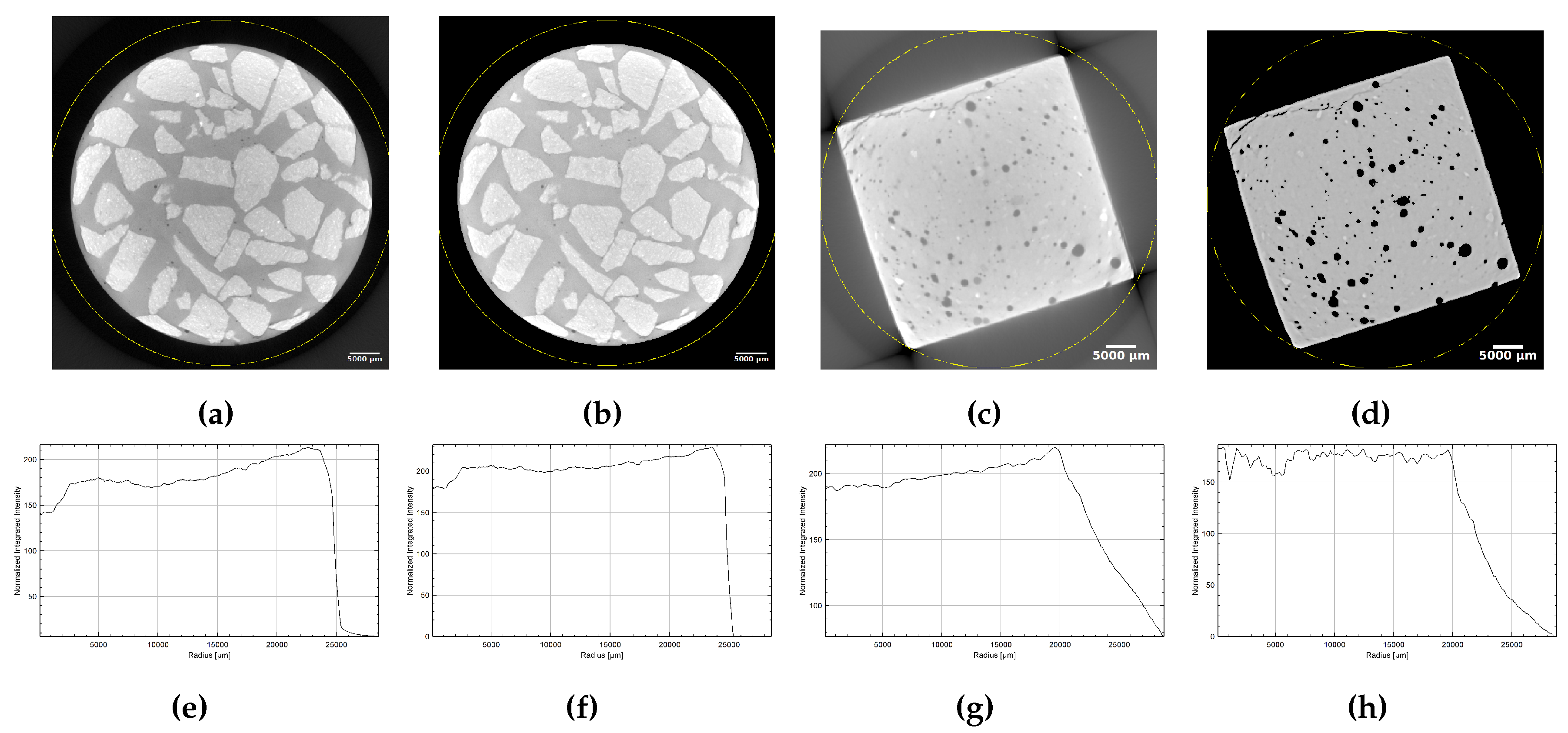

3.4. Beam Hardening Correction in CT Scans

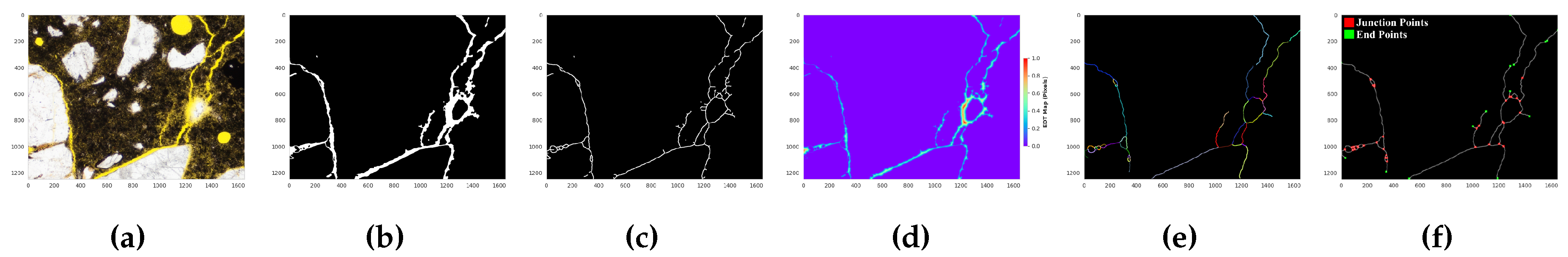

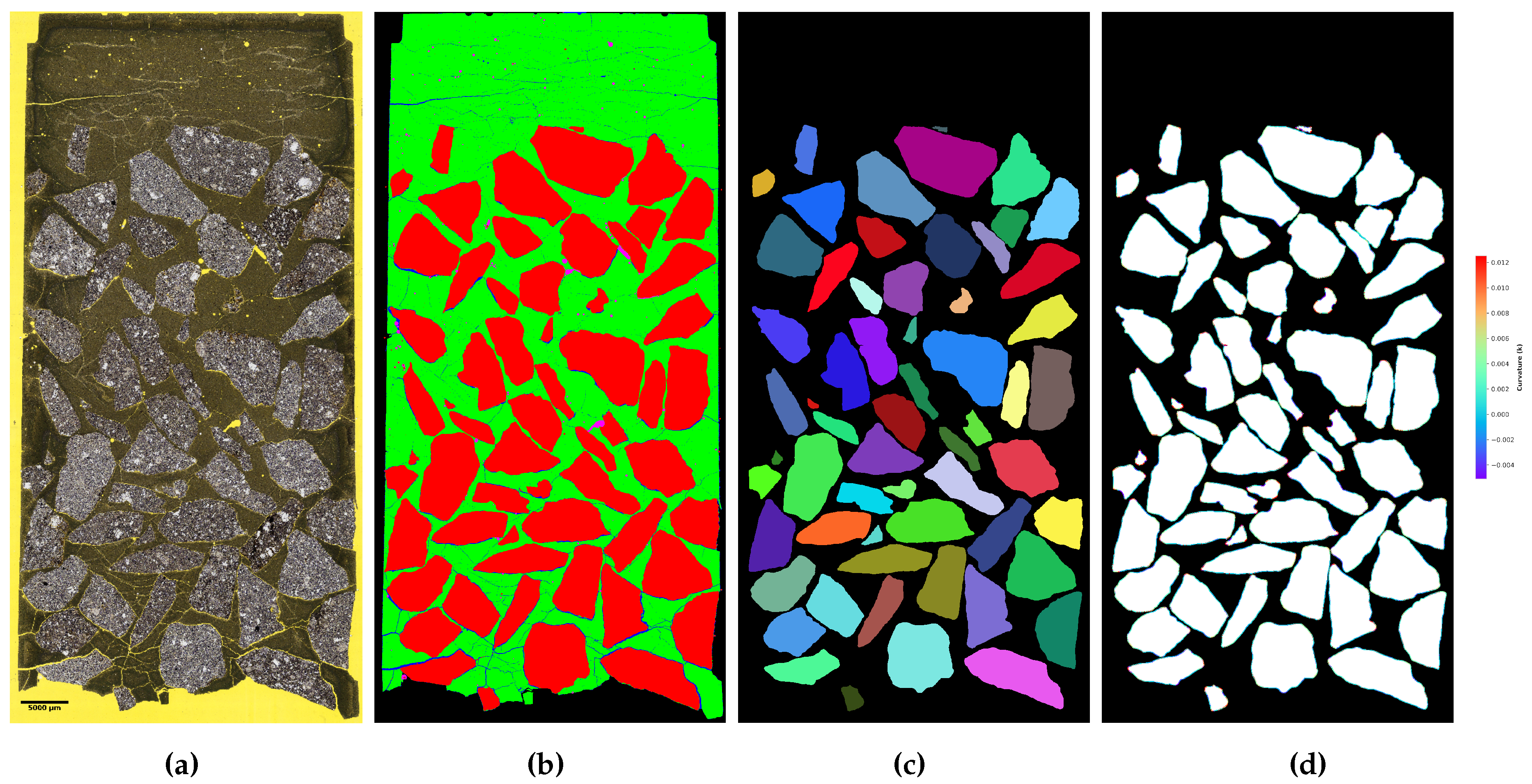

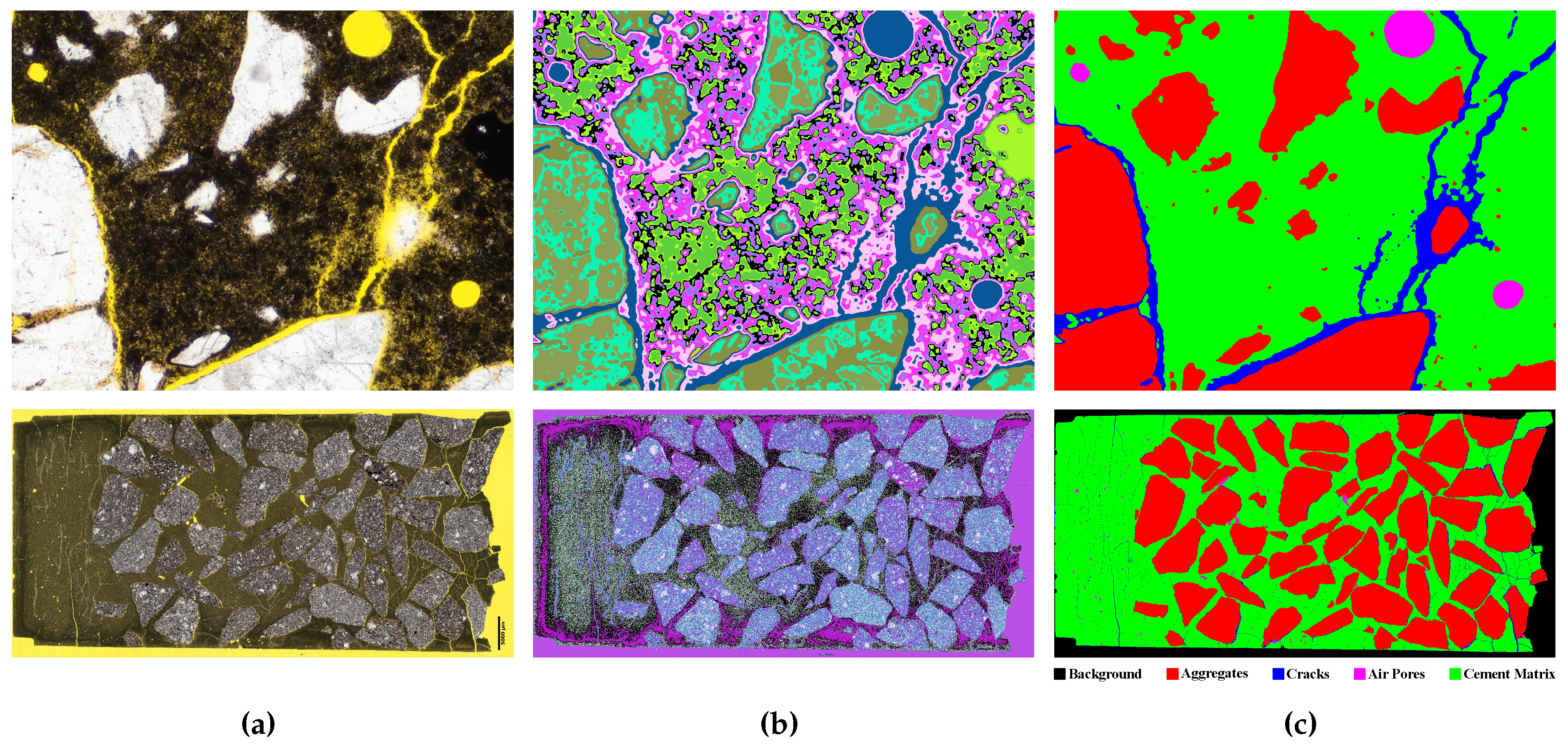

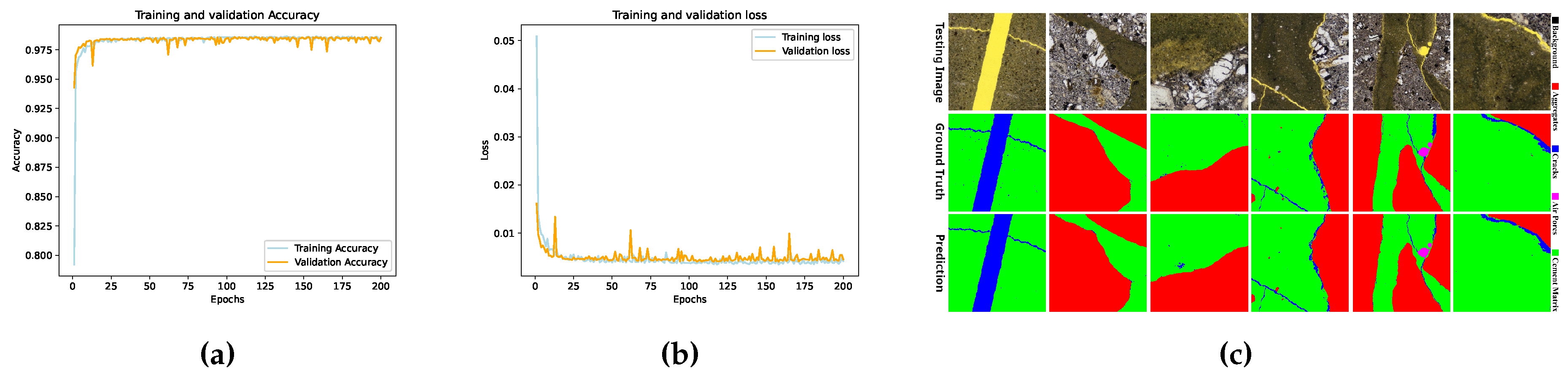

3.5. LM Semantic Segmentation

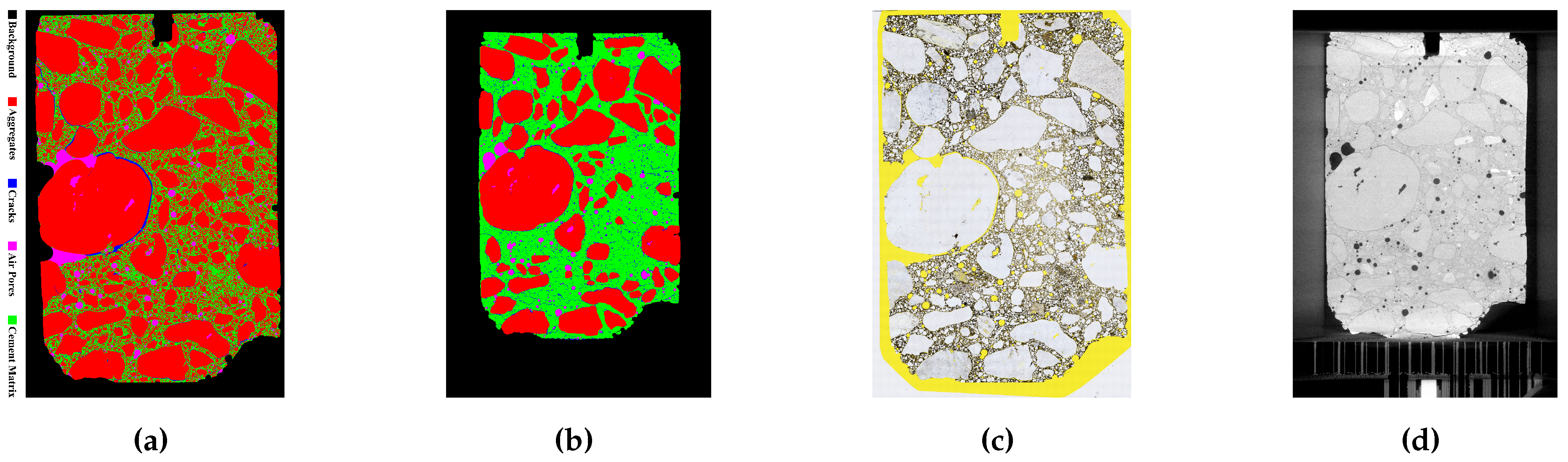

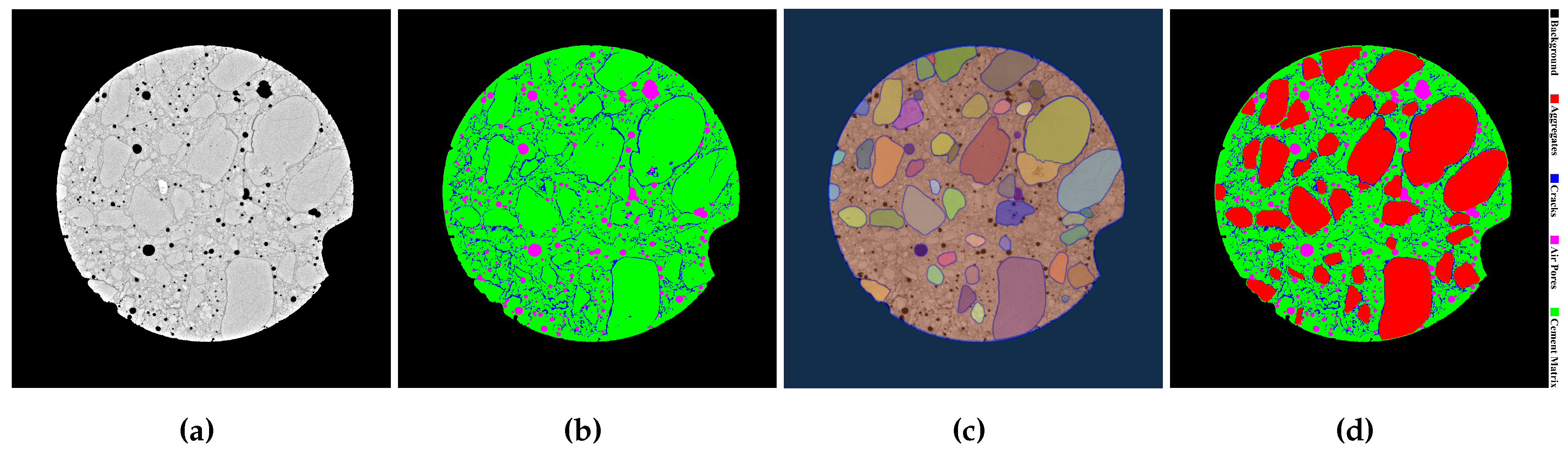

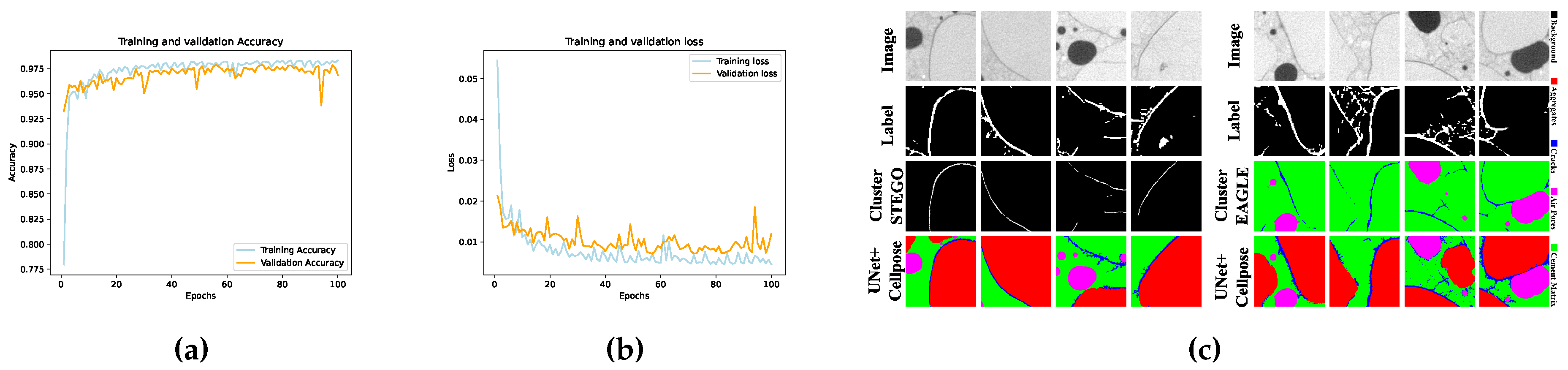

3.6. CT Semantic Segmentation

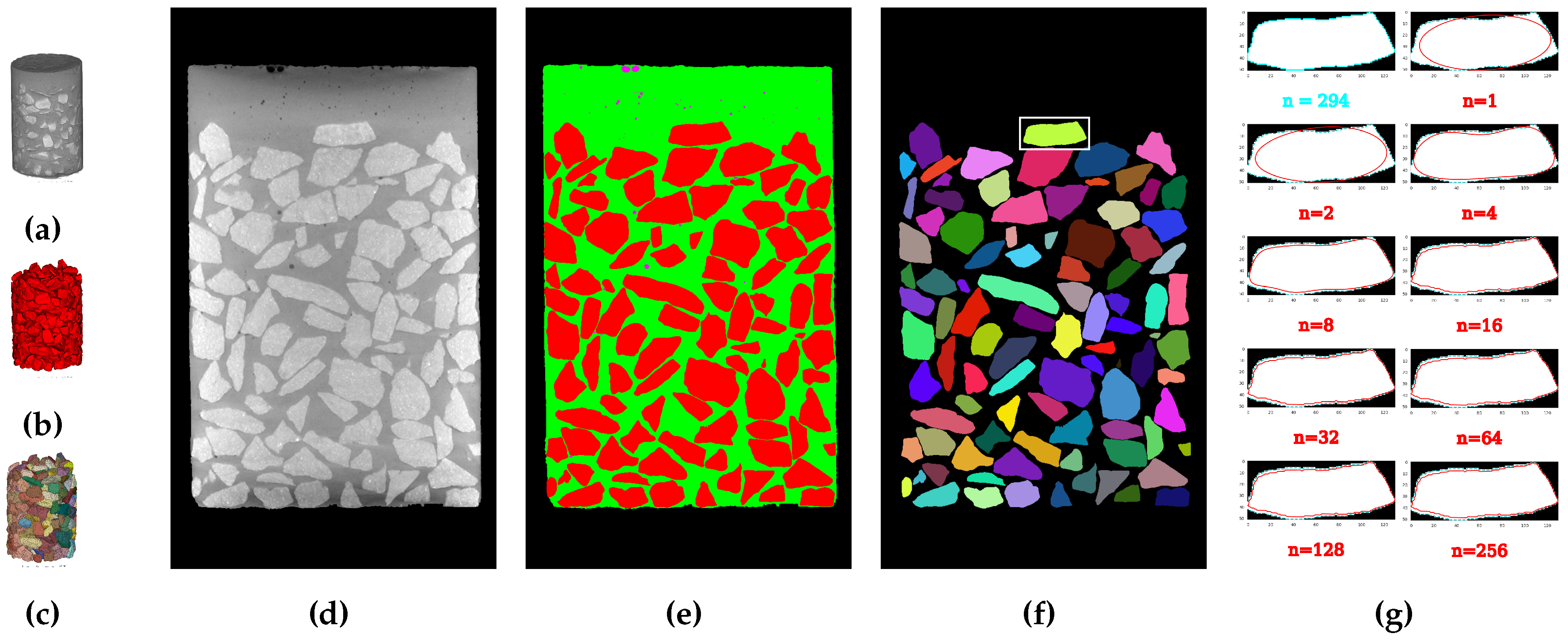

3.7. Post-Processing and Shape Descriptors Generation

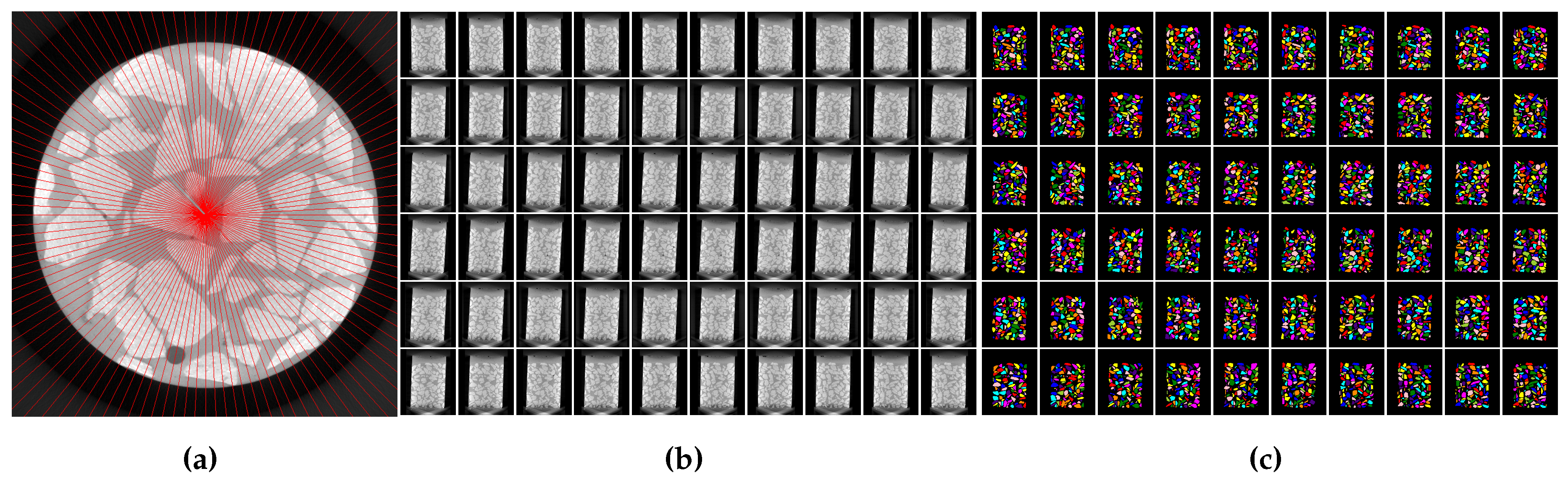

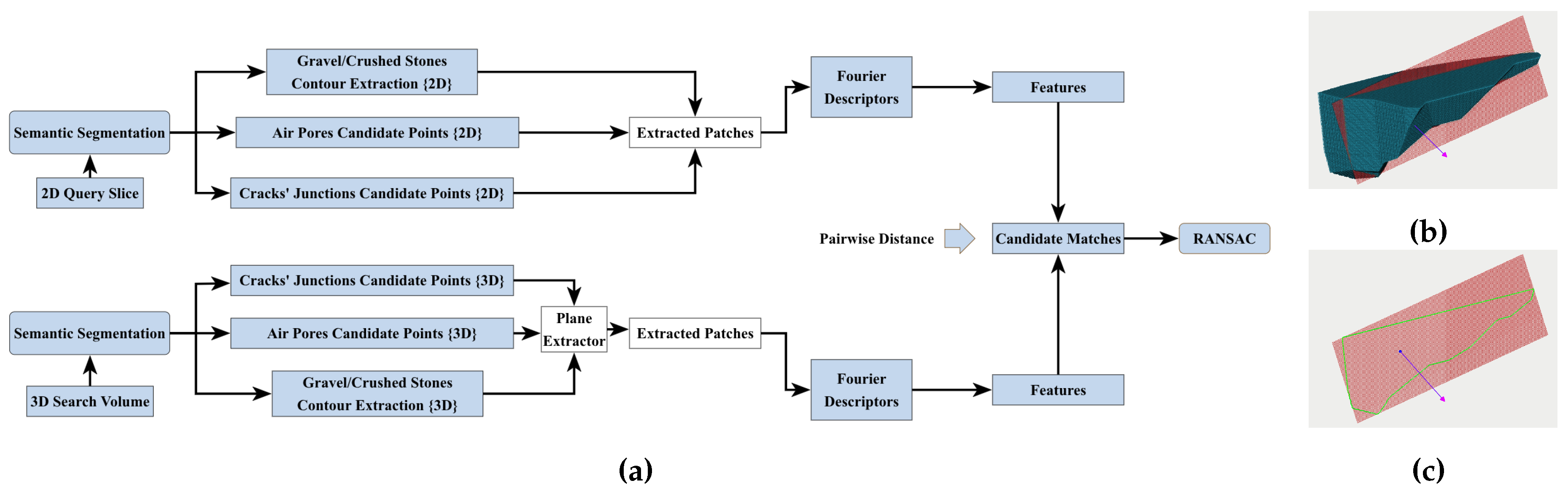

3.8. Feature Matching and Slice-to-Volume Registration

3.8.1. Feature Matching of Segmented LM and CT Cross Sections in 2D

3.8.2. 2D Feature Matching of Segmented LM and 2D Patches of 3D CT

3.8.3. Feature Matching of Segmented LM and CT in 3D

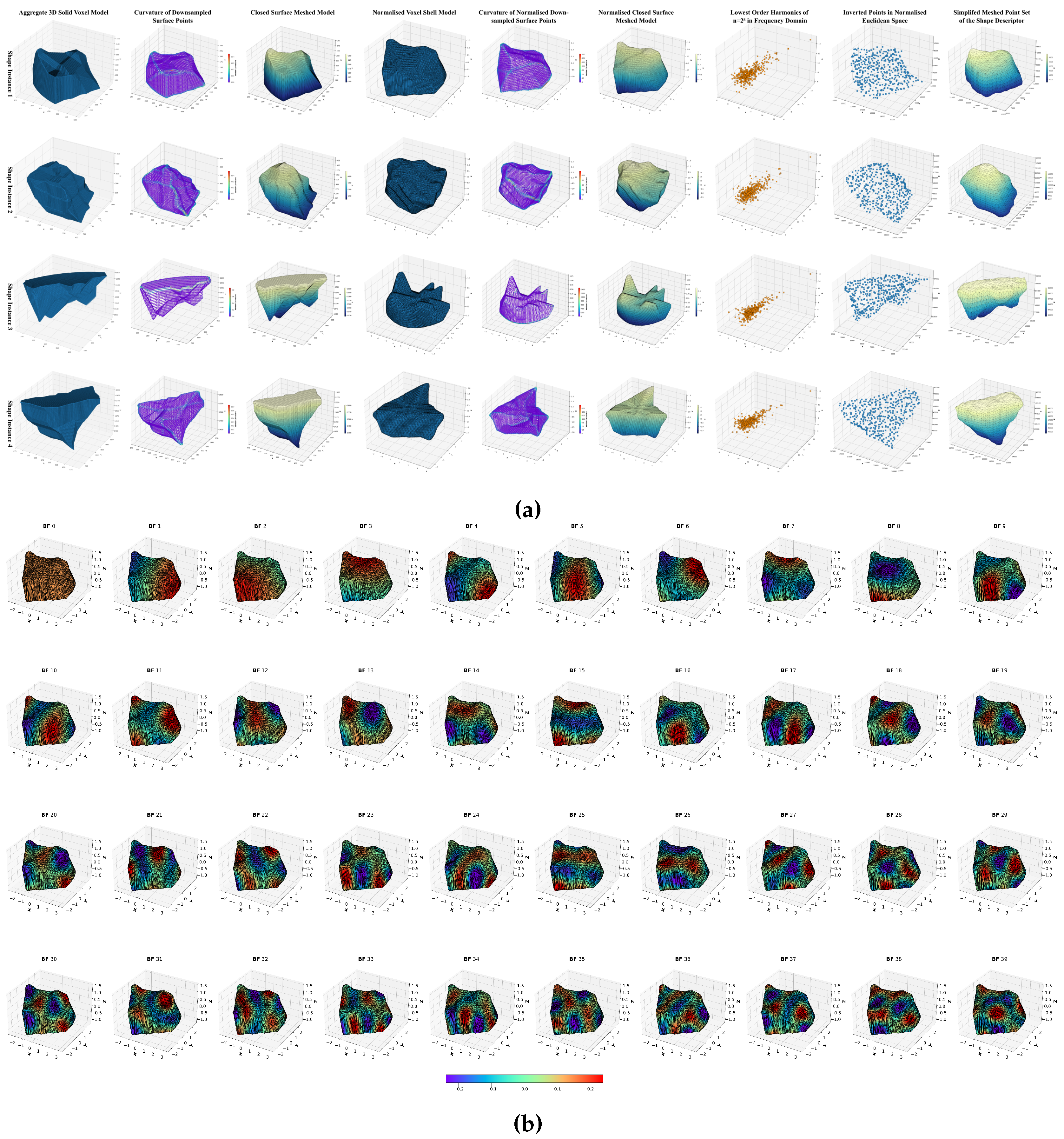

Canonical Normalisation of a 3D Shape

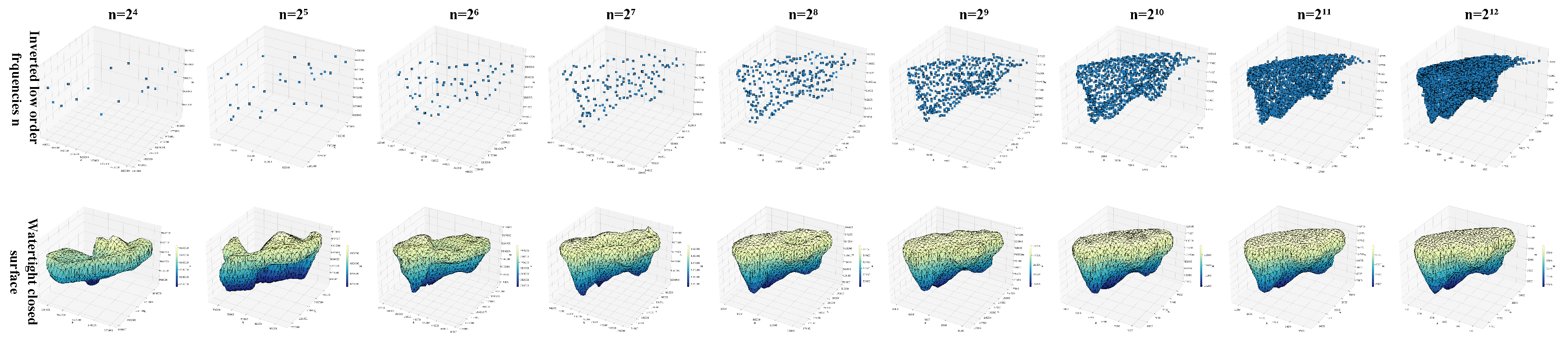

Spherical Projection and Spatial Harmonic Analysis

Feature Matching in 3D Euclidean Space

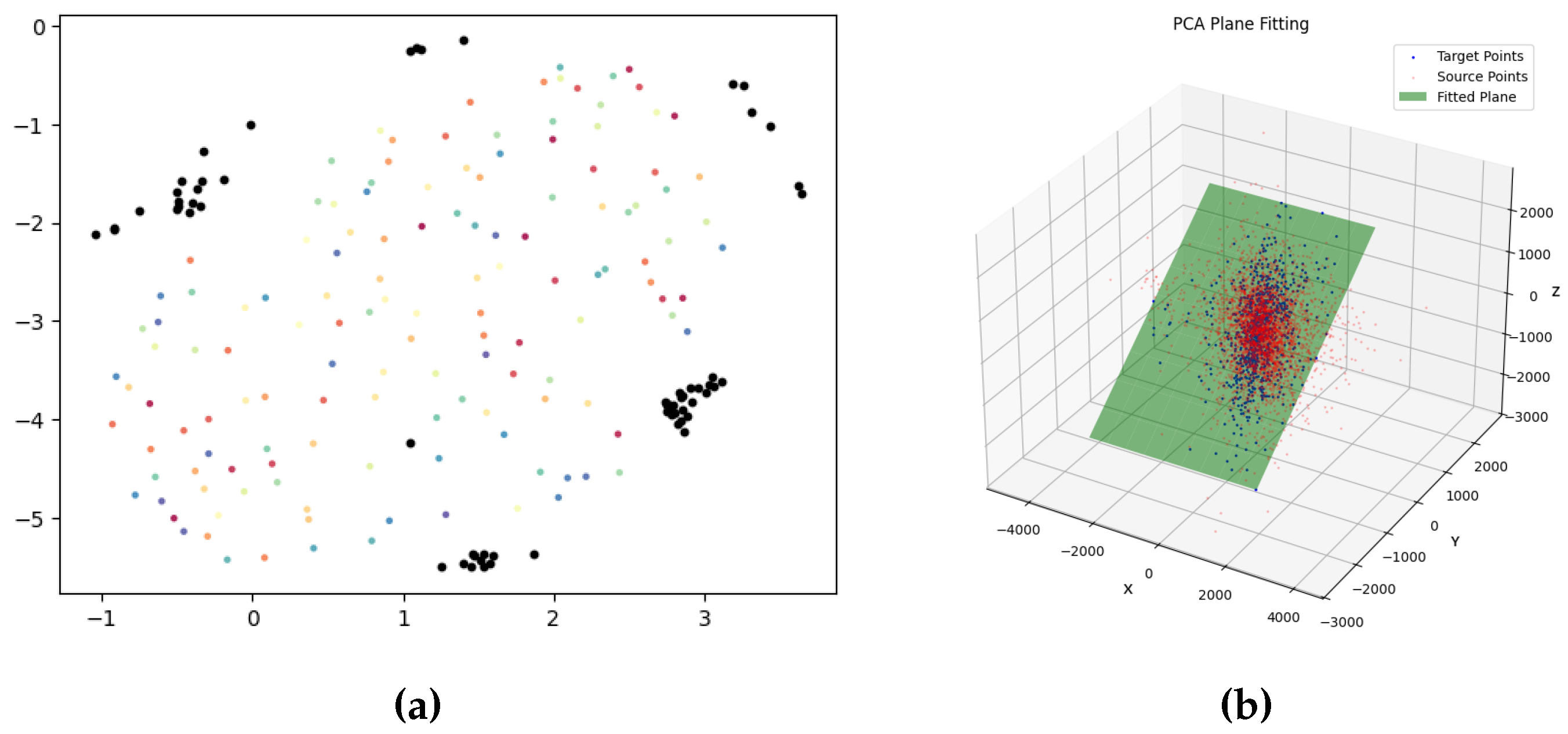

Plane Estimation Using PCA

Inverse Transformation of the Fitted Plane

4. Experimental Setup

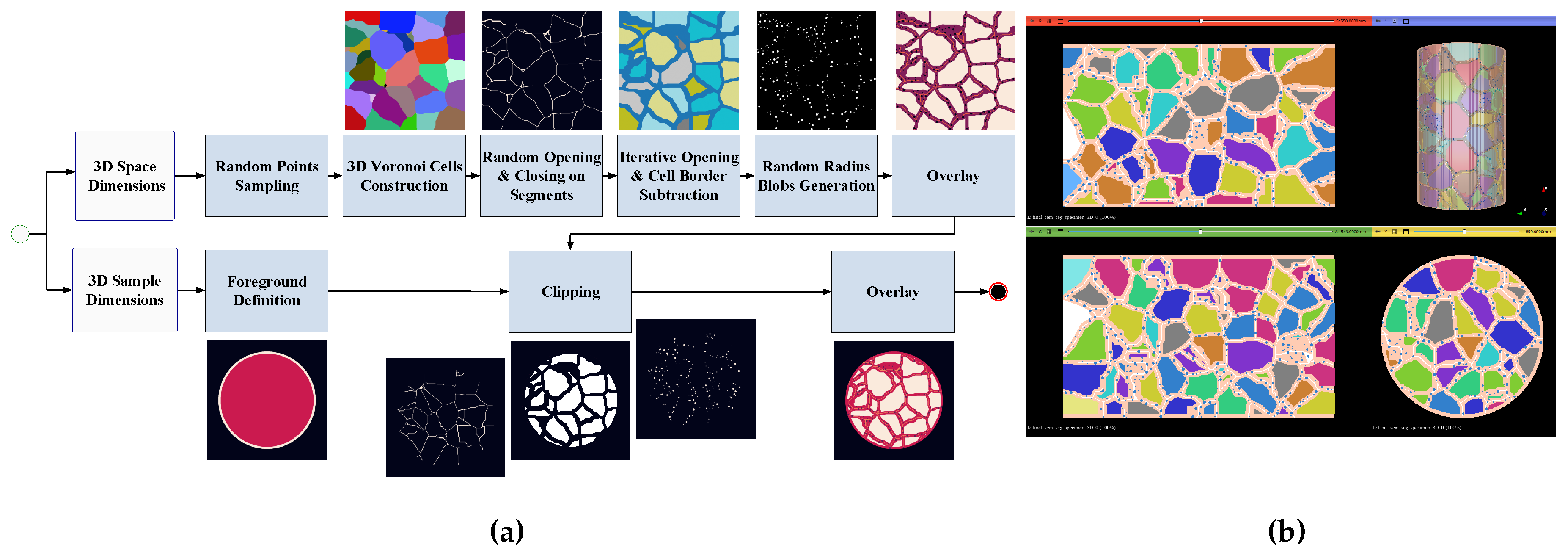

4.1. Synthetic Data Generation

4.2. Optimal Parameters’ Selection

4.2.1. Feature Analysis via Hierarchical Clustering

5. Results

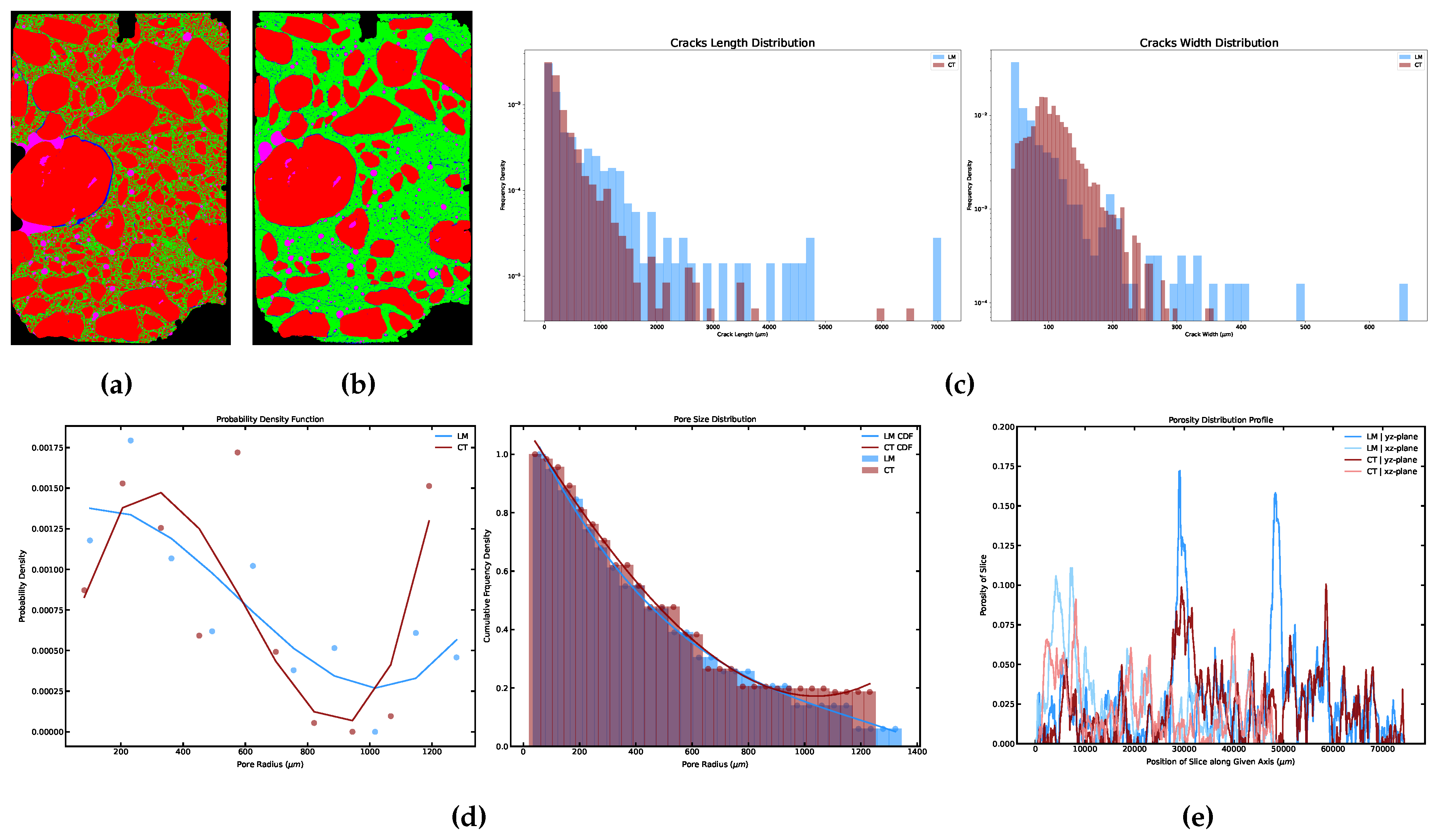

5.1. Cracks and Pores Analysis

6. Discussion and Conclusion

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Micro Computed Tomography |

| LM | Light Microscopy |

| FT | Freezing and Thawing |

| DRI | Damage Rating Index method |

| ASR | Alkali-Silica Reaction |

| ISR | Internal Swelling Reaction |

| CDF | Capillary De-icing Freeze-thaw Test |

| CIF | Capillary Suction, Internal Damage and Freeze-thaw |

| DIC | Digital Image Correlation |

| FDCT | Fast Discrete Curvelet Transform |

| GLCM | Grey Level Co-occurrence Matrix |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| FHT | Fast Haar Transform |

| LoG | Laplacian of Gaussian |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RBM | Restricted Boltzmann Machine |

| R-CNN | Region Convolutional Neural Network |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| TuFF | Tubularity Flow Field |

| DTM | Distance Transform Method |

| STEGO | Self-supervised Transformer with Energy-based Graph Optimization |

| EAGLE | Eigen Aggregation Learning |

| ReResNet | rotation equivariant ResNet |

| RANSAC | Random Consensus |

| InShaDe | Invariant Shape Descriptors |

| FFF | Fused Filament Fabrication |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| LMS | Least Mean Square |

| CLAHE | Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalisation |

| UMAP | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection |

| mIoU | mean Intersection over Union |

| SCUNet | Swin-Conv-UNet |

| CVAT | Computer Vision Annotation Tool |

| SAM | Segment Anything Model |

| TEASAR | tree-structure extraction algorithm delivering skeletons |

| that are accurate and robust | |

| EDT | Euclidean distance transform |

| CSR | Compressed Sparse Row |

| FD | Fourier Descriptor |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| LBO | Laplace-Beltrami Operator |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SVD | Singular value decomposition |

| BF | Basis Function |

| RRMSE | Relative root mean square error |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| RCA | Recycled Concrete Aggregate |

| DFN | Discrete Fracture Network |

References

- Li, H.; Wu, X.; Nie, Q.; Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Q. Lifetime prediction of damaged or cracked concrete structures: A review. Structures 2025, 71, 108095. [CrossRef]

- Arasteh-Khoshbin, O.; Seyedpour, S.M.; Brodbeck, M.; Lambers, L.; Ricken, T. On effects of freezing and thawing cycles of concrete containing nano-Formula: see text: experimental study of material properties and crack simulation. Scientific reports 2023, 13, 22278. [CrossRef]

- 5 - Concrete. In Building Materials in Civil Engineering; Haimei Zhang., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering, Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 81–423. [CrossRef]

- Abell, A.B.; Willis, K.L.; Lange, D.A. Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry and Image Analysis of Cement-Based Materials. Journal of colloid and interface science 1999, 211, 39–44. [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 224. 224R-01: Control of Cracking in Concrete Structures (Reapproved 2008). Technical Documents.

- Bisschop, J.; van Mier, J. How to study drying shrinkage microcracking in cement-based materials using optical and scanning electron microscopy? Cement and Concrete Research 2002, 32, 279–287. [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, M.; Erfurt, D.; Ludwig, H.M. Quantification of cracks in concrete thin sections considering current methods of image analysis. Journal of microscopy 2022, 286, 154–159. [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, M.; Erfurt, D.; Hadlich, C.; Vogt, F.; Ludwig, H.M.; Osburg, A. Verknüpfung & Automatisierung computergestützter Methoden zur quantitativen Rissanalyse von Beton. ce/papers 2023, 6, 1086–1090. [CrossRef]

- Grattan-Bellew, P.E.; Danay, A. Comparison of laboratory and field evaluation of alkali- silica reaction in large dams. 1992, International Conference on Concrete Alkali-aggregate Reactions in Hydroelectric Plants and Dams: 28 September 1992, Frederiction, New Brunswick, Canada, pp. 1–25.

- Dunbar, P.A.; Grattan-Bellew, P.E. Results of damage rating evaluation of condition of concrete from a number of structures affected by AAR. Natural Resources Canada, 1995, CANMET/ACI International Workshop on Alkali-Aggregate Reactions in Concrete, October 1 to 4, 1995, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, pp. 257–265.

- Zahedi, A.; Trottier, C.; Sanchez, L.F.; Noël, M. Microscopic assessment of ASR-affected concrete under confinement conditions. Cement and Concrete Research 2021, 145, 106456. [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, V.; Fournier, B.; Duchesne, J. Determination of the damage in concrete affected by ASR–the damage rating index (DRI). In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Alkali-Aggregate Reaction (ICAAR). Austin, Texas (USA), 2012.

- Sanchez, L.; Fournier, B.; Jolin, M.; Mitchell, D.; Bastien, J. Overall assessment of Alkali-Aggregate Reaction (AAR) in concretes presenting different strengths and incorporating a wide range of reactive aggregate types and natures. Cement and Concrete Research 2017, 93, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.P.; Sanchez, L.; Fournier, B.; Toutlemonde, F.c. Diagnosis of AAR and DEF: Comparison of residual expansion, stiffness damage test and damage rating index. In Proceedings of the ICAAR 2016 - 15th international conference on alkali aggregate reaction, Sao Paulo, France, 2016; p. 10p.

- Sanchez, L.; Drimalas, T.; Fournier, B. Assessing condition of concrete affected by internal swelling reactions (ISR) through the Damage Rating Index (DRI). Cement 2020, 1-2, 100001. [CrossRef]

- DIN-Fachbericht CEN/TR 15177:2006-06, Prüfung des Frost-Tauwiderstandes von Beton_- Innere Gefügestörung; Deutsche Fassung CEN/TR_15177:2006. [CrossRef]

- Setzer, M.J.; Fagerlund, G.; Janssen, D.J. CDF test — Test method for the freeze-thaw resistance of concrete-tests with sodium chloride solution (CDF). Materials and Structures 1996, 29, 523–528. [CrossRef]

- Setzer, M.J.; Heine, P.; Kasparek, S.; Palecki, S.; Auberg, R.; Feldrappe, V.; Siebel, E. Test methods of frost resistance of concrete: CIF-Test: Capillary suction, internal damage and freeze thaw test—Reference method and alternative methods A and B. Materials and Structures 2004, 37, 743–753. [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Zhi, D.; Jia, J.; Wang, Z.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ueda, T. Data-Based Statistical Analysis of Laboratory Experiments on Concrete Frost Damage and Its Implications on Service Life Prediction. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Rath, S.; Ji, X.; Takahashi, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Sakai, Y. Evaluating concrete quality under freeze–thaw damage using the drilling powder method. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials 2025, 14, 253–264. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hansen, W. Freeze–thaw durability of high strength concrete under deicer salt exposure. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 102, 478–485. [CrossRef]

- Auberg, R. Application of CIF-Test in practise for reliable evaluation of frost resistance of concrete. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Workshop on Frost Resistance of Concrete, 2002, pp. 255–267.

- Hanjari, K.Z.; Utgenannt, P.; Lundgren, K. Experimental study of the material and bond properties of frost-damaged concrete. Cement and Concrete Research 2011, 41, 244–254. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, K.; Daiezadeh, M.J.; Zakertabrizi, M.; Zahmatkesh, F.; Habibnejad Korayem, A. A review of the impact of micro- and nanoparticles on freeze-thaw durability of hardened concrete: Mechanism perspective. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 186, 1105–1113. [CrossRef]

- Spörel, F. Freeze-Thaw-Attack on concrete structures -laboratory tests, monitoring, practical experience. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Conference on Materials, Systems and Structures in Civil Engineering Conference segment on Frost Action in Concrete 22-23 August 2016, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark; Tange Hasholt, M.; Fridh, K.; Hooton, R.D., Eds., 2016, p. 151.

- Barisin, T.; Jung, C.; Nowacka, A.; Redenbach, C.; Schladitz, K. Cracks in Concrete; Vol. 227, pp. 263–280. [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, H.; Nejad, F.M.; Fahimifar, A. Image Based Techniques for Crack Detection, Classification and Quantification in Asphalt Pavement: A Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2017, 24, 935–977. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Poobal, S. Crack detection using image processing: A critical review and analysis. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2018, 57, 787–798. [CrossRef]

- Nazaryan, N.; Campana, C.; Moslehpour, S.; Shetty, D. Application of a He3Ne infrared laser source for detection of geometrical dimensions of cracks and scratches on finished surfaces of metals. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2013, 51, 1360–1367. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.A.; Abdullah, M.Z. Micro-crack detection of multicrystalline solar cells featuring an improved anisotropic diffusion filter and image segmentation technique. EURASIP Journal on Image and Video Processing 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Heideklang, R.; Shokouhi, P. Multi-sensor image fusion at signal level for improved near-surface crack detection. NDT & E International 2015, 71, 16–22. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Michaels, J.E.; Lee, S.J.; Michaels, T.E. Load-differential imaging for detection and localization of fatigue cracks using Lamb waves. NDT & E International 2012, 51, 142–149. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.Y.; Loukili, A.; Grondin, F.; Rozière, E. Use of the digital image correlation and acoustic emission technique to study the effect of structural size on cracking of reinforced concrete. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2015, 143, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, W.S.M.; Lamb, D.A.; Irvine, S.J.C. IR Reflectance Imaging for Crystalline Si Solar Cell Crack Detection. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2015, 5, 1271–1275. [CrossRef]

- Hamrat, M.; Boulekbache, B.; Chemrouk, M.; Amziane, S. Flexural cracking behavior of normal strength, high strength and high strength fiber concrete beams, using Digital Image Correlation technique. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 106, 678–692. [CrossRef]

- Iliopoulos, S.; Aggelis, D.G.; Pyl, L.; Vantomme, J.; van Marcke, P.; Coppens, E.; Areias, L. Detection and evaluation of cracks in the concrete buffer of the Belgian Nuclear Waste container using combined NDT techniques. Construction and Building Materials 2015, 78, 369–378. [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, C.; Stepper, A.; Müller, A.C.; Müller, C.H. Micro crack detection with Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm. Machine Vision and Applications 2012, 23, 589–601. [CrossRef]

- Glud, J.A.; Dulieu-Barton, J.M.; Thomsen, O.T.; Overgaard, L. Automated counting of off-axis tunnelling cracks using digital image processing. Composites Science and Technology 2016, 125, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, H.; Yin, G. Detection of surface crack defects on ferrite magnetic tile. NDT & E International 2014, 62, 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S. Imaging-based detection of AAR induced map-crack damage in concrete structure. NDT & E International 2010, 43, 461–469. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Qader, I.; Abudayyeh, O.; Kelly, M.E. Analysis of Edge-Detection Techniques for Crack Identification in Bridges. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering 2003, 17, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Ni, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z. Pixel-level crack delineation in images with convolutional feature fusion. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2019, 26, e2286. [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [CrossRef]

- Dorafshan, S.; Thomas, R.J.; Maguire, M. Comparison of deep convolutional neural networks and edge detectors for image-based crack detection in concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 186, 1031–1045. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sohn, K.; Villegas, R.; Pan, G.; Lee, H. Improving object detection with deep convolutional networks via Bayesian optimization and structured prediction; pp. 249–258. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, N.; Li, H. Identification framework for cracks on a steel structure surface by a restricted Boltzmann machines algorithm based on consumer-grade camera images. Structural Control and Health Monitoring 2018, 25, e2075. [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Bocus, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiao, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, F.; Cheng, S.; Liu, M. Road Crack Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Adaptive Thresholding; pp. 474–479. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Lu, X.; Xie, R.; Li, L. DeepCrack: A deep hierarchical feature learning architecture for crack segmentation. Neurocomputing 2019, 338, 139–153. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Qi, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S. DeepCrack: Learning Hierarchical Convolutional Features for Crack Detection. IEEE transactions on image processing : a publication of the IEEE Signal Processing Society 2018. [CrossRef]

- Benz, C.; Debus, P.; Ha, H.K.; Rodehorst, V. Crack Segmentation on UAS-based Imagery using Transfer Learning; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Iglovikov, V.; Shvets, A. TernausNet: U-Net with VGG11 Encoder Pre-Trained on ImageNet for Image Segmentation. ArXiv 2018, abs/1801.05746.

- Kang, D.; Benipal, S.S.; Gopal, D.L.; Cha, Y.J. Hybrid pixel-level concrete crack segmentation and quantification across complex backgrounds using deep learning. Automation in Construction 2020, 118, 103291. [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN; pp. 1440–1448. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Condron, B.; Acton, S.T. Tubularity flow field–a technique for automatic neuron segmentation. IEEE transactions on image processing : a publication of the IEEE Signal Processing Society 2015, 24, 374–389. [CrossRef]

- Barisin, T.; Jung, C.; Müsebeck, F.; Redenbach, C.; Schladitz, K. Methods for segmenting cracks in 3d images of concrete: A comparison based on semi-synthetic images. Pattern Recognition 2022, 129, 108747. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, Z.; Meng, F.; Chen, Z. Automatic Road Crack Detection Using Random Structured Forests. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2016, 17, 3434–3445. [CrossRef]

- Chun, P.j.; Izumi, S.; Yamane, T. Automatic detection method of cracks from concrete surface imagery using two–step light gradient boosting machine. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering 2021, 36, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Arganda-Carreras, I.; Kaynig, V.; Rueden, C.; Eliceiri, K.W.; Schindelin, J.; Cardona, A.; Sebastian Seung, H. Trainable Weka Segmentation: a machine learning tool for microscopy pixel classification. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2017, 33, 2424–2426. [CrossRef]

- Sadrnia, A.; Alabassy, M.S.H.; Osburg, A. Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation of Cracks in Concrete Specimens. In 36th Forum Bauinformatik 2025; Willmann, A.; Kobbelt, L., Eds.; RWTH Aachen University: Aachen, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hariharan, B.; Snavely, N.; Freeman, W.T. Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation by Distilling Feature Correspondences. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Han, W.; Ju, D.; Hwang, S.J. EAGLE: Eigen Aggregation Learning for Object-Centric Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation. [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, M.; Hampe, M. µCT-scans of a selection of concrete samples made of cement and coarse aggregates without sand fraction. [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolskij, D.; Persch, J.; Schladitz, K.; Steidl, G. STRUCTURE DETECTION WITH SECOND ORDER RIESZ TRANSFORMS. Image Analysis & Stereology 2019, 38, 107. [CrossRef]

- Çiçek, Ö.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. [CrossRef]

- Brandstätter, S.; Seeböck, P.; Fürböck, C.; Pochepnia, S.; Prosch, H.; Langs, G. Rigid Single-Slice-in-Volume Registration via Rotation-Equivariant 2D/3D Feature Matching. In Biomedical Image Registration; Modat, M.; Simpson, I.; Špiclin, Ž.; Bastiaansen, W.; Hering, A.; Mok, T.C.W., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; Vol. 15249, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 280–294. [CrossRef]

- Al-Thelaya, K.; Agus, M.; Gilal, N.U.; Yang, Y.; Pintore, G.; Gobbetti, E.; Calí, C.; Magistretti, P.J.; Mifsud, W.; Schneider, J. InShaDe: Invariant Shape Descriptors for visual 2D and 3D cellular and nuclear shape analysis and classification. Computers & Graphics 2021, 98, 105–125. [CrossRef]

- Onajite, E. Understanding Sample Data. In Seismic Data Analysis Techniques in Hydrocarbon Exploration; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 105–115. [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, K., Ed. Proceedings of ECMCS- 2001, the 3 rd EURASIP Conference on Digital Signal Processing for Multimedia Communications and Services, 11 - 13 September 2001, Budapest, Hungary, Budapest, 2001. Scientific Assoc. of Infocommunications.

- Zuiderveld, K. Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization. In Graphics gems IV; 1994; pp. 474–485.

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. [CrossRef]

- Attias, H. A variational Bayesian framework for graphical models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; NIPS’99, pp. 209–215.

- Blei, D.M.; Jordan, M.I. Variational inference for Dirichlet process mixtures. Bayesian Analysis 2006, 1. [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.C.; Torralba, A.; Murphy, K.P.; Freeman, W.T. LabelMe: A Database and Web-Based Tool for Image Annotation. International Journal of Computer Vision 2008, 77, 157–173. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.L.; Bian, G.B.; Zhou, X.H.; Hou, Z.G.; Xie, X.L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.J.; Li, R.Q.; Li, Z. RAUNet: Residual Attention U-Net for Semantic Segmentation of Cataract Surgical Instruments. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H.; Fan, D.P.; Timofte, R.; van Gool, L. Practical Blind Image Denoising via Swin-Conv-UNet and Data Synthesis. Machine Intelligence Research 2023, 20, 822–836. [CrossRef]

- CVAT.ai Corporation. Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT), 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything. [CrossRef]

- Stringer, C.; Pachitariu, M. Cellpose3: one-click image restoration for improved cellular segmentation. Nature methods 2025, 22, 592–599. [CrossRef]

- William Silversmith.; J. Alexander Bae.; Peter H. Li.; A.M. Wilson. Kimimaro: Skeletonize Densely Labeled Images, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Westin, C.; Bhalerao, A.; Nakajima, S.; Shiraga, N.; Tamura, S.; Kikinis, R. Tissue classification based on 3D local intensity structures for volume rendering. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2000, 6, 160–180. [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Blanch, A.J.; Looker, O.; Dixon, M.W.; Tilley, L. A new Python library to analyse skeleton images confirms malaria parasite remodelling of the red blood cell membrane skeleton. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4312. [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, M.K.; McCann, C.; Kopace, R.; Homan, T.; Fourkas, J.T.; Parent, C.; Losert, W. Cell shape dynamics: from waves to migration. PLoS computational biology 2012, 8, e1002392. [CrossRef]

- Vranic, D.; Saupe, D. 3D Shape Descriptor Based on 3D Fourier Transform; pp. 271–274.

- Heczko, M.; Keim, D.; Saupe, D.; Vranić, D.V. Verfahren zur Ähnlichkeitssuche auf 3D-Objekten; pp. 384–401. [CrossRef]

- Graichen, U.; Eichardt, R.; Fiedler, P.; Strohmeier, D.; Zanow, F.; Haueisen, J. SPHARA–a generalized spatial Fourier analysis for multi-sensor systems with non-uniformly arranged sensors: application to EEG. PloS one 2015, 10, e0121741. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nature communications 2024, 15, 9935. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, H.S.; Ajo-Franklin, J.; Birkholzer, J.T.; Carey, J.W.; Guglielmi, Y.; Hyman, J.D.; Karra, S.; Pyrak-Nolte, L.J.; Rajaram, H.; Srinivasan, G.; et al. From Fluid Flow to Coupled Processes in Fractured Rock: Recent Advances and New Frontiers. Reviews of Geophysics 2022, 60. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Smolarkiewicz, P.K.; Winter, C.L. Heterogeneities of flow in stochastically generated porous media. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics 2012, 86, 056701. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Winter, C.L. Hyperbolic regions in flows through three-dimensional pore structures. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics 2013, 88, 063014. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Winter, C.L. Hyperbolic regions in flows through three-dimensional pore structures. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics 2013, 88, 063014. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Gable, C.W.; Painter, S.L.; Makedonska, N. Conforming Delaunay Triangulation of Stochastically Generated Three Dimensional Discrete Fracture Networks: A Feature Rejection Algorithm for Meshing Strategy. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2014, 36, A1871–A1894. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Guadagnini, A.; Winter, C.L. Statistical scaling of geometric characteristics in stochastically generated pore microstructures. Computational Geosciences 2015, 19, 845–854. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Sweeney, M.R.; Frash, L.P.; Carey, J.W.; Viswanathan, H.S. Scale–Bridging in Three–Dimensional Fracture Networks: Characterizing the Effects of Variable Fracture Apertures on Network–Scale Flow Channelization. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48. [CrossRef]

- Hyman, J.D.; Karra, S.; Makedonska, N.; Gable, C.W.; Painter, S.L.; Viswanathan, H.S. dfnWorks: A discrete fracture network framework for modeling subsurface flow and transport. Computers & Geosciences 2015, 84, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Guiltinan, E.; Santos, J.E.; Purswani, P.; Hyman, J.D. pySimFrac: A Python library for synthetic fracture generation and analysis. Computers & Geosciences 2024, 191, 105665. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).