1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Medical Device-Related Pressure Injury (MDRPI) is an injury that occurs at the site of contact with a medical device applied for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes, characterized by localized tissue damage conforming to the shape of the device [

1]. The 2019 National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) international guidelines expanded the definition of MDRPI to include injuries caused by non-medical devices such as bed frames and household items, recommending that MDRPI be assessed and documented independently, distinct from general pressure injuries [

2]. This expanded definition underscores that MDRPI is no longer a secondary complication but a distinct and increasingly prevalent patient safety concern across healthcare settings.

Indeed, recent studies report clinically significant MDRPI incidence rates in diverse clinical environments. A prospective study of intensive care unit (ICU) patients in Turkey reported an MDRPI incidence rate of 27.2% [

3], while a large-scale meta-analysis including 117,624 patients worldwide reported an average MDRPI incidence rate of 19.3% [

4]. In Korea, MDRPI incidence rates ranging from 5.48% to 19.8% have been consistently reported across various settings, including ICUs, general wards, and integrated nursing care wards [

5,

6]. Furthermore, research indicating that the risk of MDRPI increases by 1.16 times for each additional device [

7] suggests that the problem is becoming increasingly significant in the modern healthcare environment, where device use is unavoidable. Thus, the high global incidence of MDRPI, including in Korea, makes it a major cause of multidimensional negative effects—not only causing patient pain and functional discomfort but also leading to delayed recovery, increased infection risk, rising healthcare costs, and prolonged hospital stays [

8,

9]—making it unquestionably a critical issue requiring serious attention. Consequently, international guidelines classify all patients using medical devices as high-risk for MDRPI and emphasize the importance of structured nursing interventions, such as regular assessment of device contact areas, early detection of damage, application of preventive dressings, and pressure redistribution [

2,

10].

However, despite the existence of evidence-based recommendations for preventing MDRPI, the actual implementation of MDRPI prevention practices in clinical settings falls short of expectations. Previous literature indicates that Korean nurses’ MDRPI prevention performance levels are below average [

5], and various organizational and environmental factors—such as excessive workload, priority conflicts, knowledge gaps, and staffing or resource constraints—impede consistent preventive practices [

7,

11]. Particularly in healthcare environments with nursing shortages, when additional nursing work time is provided, the actual risk of pressure injuries decreases by 80% [

12], and prior research demonstrating that appropriate staffing is essential for MDRPI prevention suggests that workload burden can be a primary factor directly affecting task performance [

13,

14,

15]. While positive links between workload and preventive nursing have been reported, previous research has largely been limited to direct associations, leaving the underlying mechanisms of MDRPI prevention performance unclear. Specifically, empirical studies examining the mediating role of personal factors are scarce, despite theoretical evidence suggesting that performance arises from the interplay between environmental factors and individual psychological capacities. Therefore, grounded in Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), this study examines whether nurses’ occupational coping self-efficacy mediates the relationship between workload and MDRPI prevention performance. By clarifying this mechanism, the study seeks to move beyond simplistic workload–performance models and to generate evidence that can inform more effective patient safety and quality improvement strategies in nursing practice.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical basis of this study, SCT, is a representative framework that explains the formation and change of human behavior through interactions among personal, environmental, and behavioral factors [

16]. The core concept of SCT, reciprocal determinism, emphasizes that individuals’ cognitive and emotional states (e.g., self-efficacy), their social and physical environment (e.g., workload), and their actual behaviors (e.g., performing MDRPI prevention) are not linked by unidirectional causality. Instead, they form a structure of mutual and cyclical influence [

16,

17]. This framework provides a robust theoretical basis for understanding preventive nursing behaviors within complex clinical environments.

In particular, self-efficacy, presented as the most central factor in SCT, refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform actions successfully in specific situations. It is described as a key psychological component determining action choices, persistence of effort, perseverance in challenging situations, and resilience under stress [

18]. In nursing, self-efficacy has been repeatedly confirmed as a crucial antecedent for setting priorities in complex clinical situations and consistently performing patient safety-related behaviors [

12,

19]. Preventive nursing practices such as MDRPI prevention require active implementation, including continuous observation, early assessment, and rapid judgment [

20]. Therefore, the level of self-efficacy can directly influence MDRPI prevention performance [

21]. Among the dimensions of self-efficacy, occupational coping self-efficacy (OCSE) is defined as an individual’s assessment of their ability to effectively manage clinical stressors, such as diverse demands, high workload, unpredictable patient conditions, and interpersonal burdens [

22]. It is regarded as a crucial personal capacity for nurses, enabling complex clinical decision-making and sustained task performance [

23]. Previous studies have also reported that nurses with high OCSE exhibit higher levels of preventive nursing practice and maintain task performance more efficiently while managing work stress [

24,

25]. Importantly, OCSE has been shown to buffer the negative impact of workload on work-related outcomes, suggesting a potential mediating role [

26].

Thus, although positive relationships between self-efficacy and preventive nursing practice have been consistently reported, previous research has often been limited to presenting only superficial associations, simply suggesting that workload reduces preventive practice. More sophisticated mechanisms—such as the process through which workload impedes MDRPI preventive practices and the role OCSE plays in this process—have not been sufficiently elucidated. In particular, empirical verification of whether the effects of workload on MDRPI prevention are purely direct or whether indirect pathways mediated by personal factors exist, as described by SCT, remains severely lacking.

Therefore, this study, grounded in SCT, aims to clarify how the environmental factor of workload influences MDRPI prevention performance and whether OCSE mediates this pathway. Through this, the study proposes that, beyond existing approaches focused solely on reducing workload to enhance MDRPI prevention performance, strategies for strengthening individual capabilities should also be considered. The findings of this study will provide foundational evidence for developing targeted, dual-focus interventions aimed at strengthening the nursing workforce’s capacity for preventive practice. Ultimately, this work is expected to contribute to the establishment of sustainable organizational and educational strategies that enhance patient safety and the delivery of high-quality care across diverse clinical settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a descriptive correlational design incorporating a mediation model to examine the indirect effect of OCSE on the relationship between workload and MDRPI prevention performance. Data were collected at a single time point, and the proposed mediation model was tested to explore potential mechanisms linking environmental and personal factors rather than to establish causal relationships. The model was conceptually grounded in SCT, which informed the selection of variables and hypothesized pathways among workload, OCSE, and MDRPI prevention performance.

2.2. Study Population

The participants were nurses working in the ICUs, general wards, and integrated nursing care wards of general hospital located in region P, South Korea, from May to July 2025. This study adopted a convenience sampling strategy based on institutional accessibility and feasibility, which is commonly used in exploratory mediation studies conducted in clinical settings. The inclusion criteria were as follows: [

1] registered nurses providing direct patient care and [

2] at least six months of clinical experience. Only those who voluntarily provided informed consent were enrolled. Nurses working exclusively in administrative or managerial roles without direct patient-care responsibilities were excluded.

Sample size estimation was conducted using G*Power 3.1 based on the multiple regression model underlying the mediation analysis. Following methodological recommendations that mediation models require adequate power for detecting the smallest path in the regression sequence, we used the total-effect regression (workload → MDRPI prevention performance) as the most conservative criterion. A medium effect size (f² = 0.15), α = .05, and power = .80 were assumed in accordance with Cohen’s guidelines and previous studies examining similar behavioral outcomes among nurses. A total of 12 covariates (workload, self-efficacy, gender, age, department, work type, marital status, household income, educational level, clinical experience, and average number of patients assigned per nurse), including demographic and work-related characteristics previously reported to be associated with preventive performance, were included to avoid model overestimation. Under these parameters, the minimum required sample size was 127. To account for incomplete or invalid responses, 195 nurses were initially recruited. After data screening, 14 responses were excluded due to predefined quality criteria, resulting in a final analytic sample of 181 participants, which exceeded the minimum required sample size and ensured sufficient statistical power for mediation analysis.

2.3. Data Collection

An online survey format was adopted to ensure accessibility for nurses working rotating shifts and to minimize disruption to clinical workflow. Because bedside nurses in general wards, ICUs, and integrated nursing care units frequently experience unpredictable workloads, an online platform allowed participation at a convenient time without interfering with patient care. The survey was administered through a secure, encrypted system approved by the hospital’s nursing administration, ensuring that all eligible nurses received equal opportunity to participate regardless of unit or work schedule. To ensure data quality, only one submission per device and IP address was allowed by the survey platform. All items were mandatory to minimize missing data; however, participants could withdraw before submitting their responses. Responses were screened for quality using predefined criteria. Cases were excluded if they demonstrated straight-lining patterns across multiple items, had an implausibly short completion time (< 3 minutes), or had missing values due to early termination. Based on these criteria, 14 invalid responses were removed, resulting in a final analytic sample of 181 participants.

No personally identifiable information was collected. All survey data were stored on an encrypted, password-protected server accessible only to the research team, in accordance with institutional data protection policies.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 29.0. The statistical significance level was set at p < .05 for two-tailed tests. Prior to conducting regression analyses, assumptions of normality, linearity, homoscedasticity, and independence of residuals were examined and met. Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF); all were below the commonly accepted threshold of 10, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables, were used to summarize participants’ characteristics and major study variables. Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated to assess the reliability of the measurement tools. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to examine bivariate associations between workload, OCSE, and MDRPI prevention performance.

To examine the mediating effect of OCSE, a two-step analytical approach was employed. First, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to explore the relationships among variables in accordance with the conceptual framework proposed by Baron and Kenny [

27]. This step was used to examine the direction and magnitude of associations among workload, OCSE, and MDRPI prevention performance rather than to formally confirm mediation. Categorical control variables (e.g., department, employment type) were dummy coded prior to analysis. In each regression model, control variables (gender, department, employment type, clinical experience, educational level, and average number of patients assigned per nurse) were entered in the first block, followed by the independent and mediator variables. Second, the statistical significance of the indirect effect was formally tested using the PROCESS macro (Model 4). Bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI) was applied, as this method does not rely on normality assumptions and is recommended for mediation analysis, particularly in cross-sectional designs. Mediation was considered statistically significant when the bootstrapped CI for the indirect effect did not include zero.

2.5. Measurement Tools

The instruments used in this study included measures for workload, performance in preventing MDRPIs, and OCSE. All instruments were selected based on prior evidence of validity and reliability in nursing populations and alignment with the theoretical framework of this study. Permission to use all instruments was obtained from the respective copyright holders or developers.

2.5.1. Workload

Workload was measured using the Korean version of the NASA-Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), which consists of six subdimensions: Mental Demand, Physical Demand, Temporal Demand, Performance, Effort, and Frustration. In the present study, the “Performance” subdimension was excluded from the workload score for both statistical and theoretical reasons.

First, confirmatory factor analysis showed that the Performance item had a factor loading below .50, indicating that it did not adequately represent the underlying construct of perceived workload. Second, prior research has noted that the Performance item differs conceptually from other NASA-TLX components because it reflects a self-evaluation of task outcome rather than the subjective burden experienced during task performance. Accordingly, several studies measuring perceived or subjective workload have excluded the Performance item to maintain construct purity [

26,

28,

29].

After removing the Performance item, the remaining five items demonstrated satisfactory construct validity (factor loadings ≥ .50, AVE ≥ .50, CR ≥ .70). The total workload score was calculated as the mean of these five items, with higher scores indicating greater perceived workload. In this study, the modified five-item scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .908).

2.5.2. Medical Device-Related Pressure Injury Prevention Performance

The prevention performance tool used in this study was originally developed by Kim as the Performance Scale of Preventive Activities for Medical Device-Related Pressure Injuries [

5]. This instrument consists of four domains: assessment (10 items), performance of preventive activities (3 items), records and reports (3 items), and education (1 item). Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 4 (very important). The total performance score was calculated as the sum of all items (range: 17–68), with higher scores indicating a higher level of nursing performance. In a previous study, Cronbach’s α was .93, and in this study, Cronbach’s α was .94.

2.5.3. Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy

The Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy Scale for Nurses (OCSE-N) was adapted to Korean and used in this study [

26]. This instrument consists of nine items divided into two subdomains: occupational burden and relational difficulty. Each item is measured on 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Total OCSE-N scores were computed by summing the nine items (range: 9–45), with higher scores indicating higher OCSE. In a previous study, the Cronbach’s α for all items was reported as .89, with .79 for the occupational burden subdomain and .89 for the relational difficulty subdomain [

26]. In this study, Cronbach’s α for all items was .89, and the reliability for the two subdomains was .79 for occupational burden and .89 for relational difficulty.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University WISE Campus (DGU IRB 20250008). The personal information of participants was kept strictly confidential, and participation was based on voluntary consent. Participants provided online informed consent after being informed of the purpose and procedures of the study, potential discomforts, the handling of personal information after study completion, and their right to withdraw at any time without disadvantage. The personal information of the research participants was kept strictly confidential and will be retained for three years after study completion before being destroyed.

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

A total of 181 nurses participated in this study (

Table 1). The majority were female (89.0%), and the largest age group was 26–30 years (39.2%), followed by those aged ≤25 years (27.1%). Participants were distributed across general wards (36.5%), ICUs (32.6%), and nurse-managed integrated care wards (30.9%). Most participants worked three-shift rotations (82.3%), and 71.8% were single.

Regarding socioeconomic characteristics, the most common monthly household income was 3–4 million KRW (58.6%), and 76.2% held a bachelor’s degree. Nearly half of the nurses (48.5%) had 6 months to less than 5 years of clinical experience, whereas 29.3% had 5 to less than 10 years. Concerning patient load, 38.7% cared for 6–10 patients per shift, followed by those caring for ≤5 patients (32.0%).

3.2. Differences in Study Variables According to Participants’ Characteristics

Table 2 presents differences in workload, occupational coping self-efficacy, and MDRPI prevention performance according to participants’ demographic and work-related characteristics. Workload did not significantly differ by gender, age group, work department, employment type, marital status, educational level, clinical experience, or the number of patients assigned per nurse (all

p > .05).

Occupational coping self-efficacy differed significantly by age (F = 5.198, p = .002), employment type (F = 3.541, p = .031), and marital status (t = −3.561, p < .001). Post hoc analysis indicated that nurses aged ≥36 years reported significantly higher occupational coping self-efficacy than those aged ≤25 years. In addition, nurses working fixed day shifts demonstrated higher occupational coping self-efficacy than those working rotating shifts. Married nurses also reported significantly higher levels of occupational coping self-efficacy compared to single nurses.

MDRPI prevention performance showed significant differences according to marital status (t = −2.756, p = .006), educational level (F = 3.682, p = .027), and the number of patients assigned per nurse (F = 3.225, p = .024). Specifically, married nurses and those with higher educational attainment demonstrated higher prevention performance. Furthermore, nurses caring for 11–15 patients per shift showed significantly higher MDRPI prevention performance compared to those caring for ≥16 patients.

3.3. Correlations Among Study Variables

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships among workload, OCSE, and MDRPI prevention performance (

Table 3). Workload showed a significant negative correlation with OCSE (r = –.380,

p < .01) and with MDRPI prevention performance (r = –.235,

p < .01). OCSE demonstrated a significant positive correlation with MDRPI prevention performance (r = .397,

p < .01). These findings indicate that higher workload is associated with lower self-efficacy and poorer preventive performance, whereas higher self-efficacy is associated with better MDRPI prevention performance.

3.4. Mediating Effect of Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Work load and MDRPI Prevention Performance

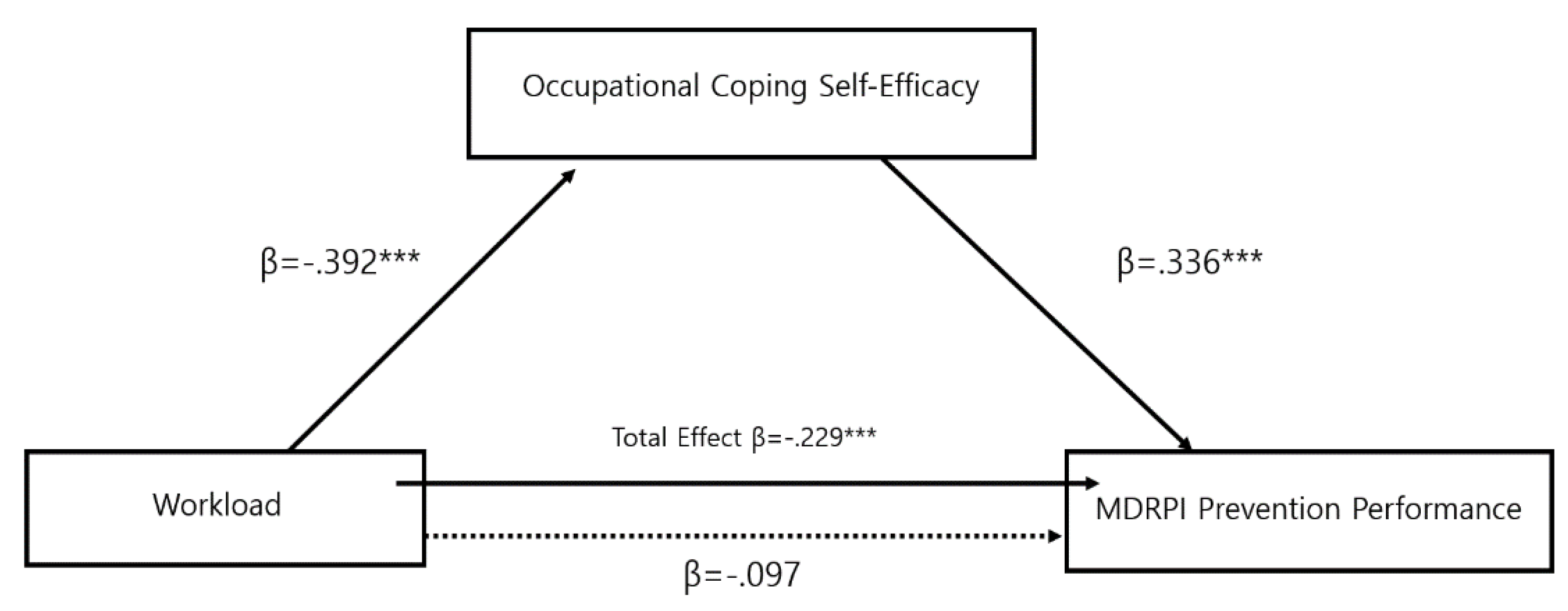

Hierarchical regression analysis and bootstrapped mediation testing were conducted to examine whether OCSE mediated the relationship between workload and MDRPI prevention performance. All analyses were performed after adjusting for relevant demographic and work-related covariates, including gender, age, work department, employment type, educational level, clinical experience, and the average number of patients assigned per nurse. The detailed results are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 1

In the initial regression model, workload showed a significant negative association with OCSE (β = −.392, p < .001). In the subsequent model, workload was also negatively associated with MDRPI prevention performance (β = −.229, p < .001), indicating that higher perceived workload was related to lower self-efficacy and poorer prevention performance prior to inclusion of the mediator.

When OCSE was entered into the model, the direct association between workload and MDRPI prevention performance was attenuated and no longer statistically significant (β = −.097, p = .201), whereas OCSE demonstrated a significant positive association with MDRPI prevention performance (β = .336, p < .001). This pattern indicates that the association between workload and prevention performance was largely accounted for by OCSE when both variables were considered simultaneously.

Bootstrapping analysis using 5,000 resamples further confirmed the significance of the indirect effect. The bias-corrected 95% confidence interval for the indirect path from workload to MDRPI prevention performance through OCSE (B = −.004, SE = .001) ranged from −.006 to −.002 and did not include zero. These findings indicate that OCSE functions as a significant mediating mechanism linking workload to MDRPI prevention performance.

4. Discussion

Based on SCT, this study examined the mediating role of OCSE in the relationship between nurses’ workload and MDRPI prevention performance. The results indicated that although workload did not have a significant direct effect on MDRPI prevention performance, it exerted a significant indirect effect through OCSE, confirming a full mediation model. These findings indicate that higher workload is not directly associated with poorer preventive performance, but rather affects it indirectly by lowering nurses’ OCSE. Therefore, to enhance MDRPI prevention, strategies should focus not only on managing workload but, more importantly, on interventions designed to boost OCSE. This contrasts with previous literature suggesting a direct negative link between workload and practice implementation. Specifically, rather than a simple linear path in which high workload directly reduces performance, a psychological mechanism operates: excessive workload undermines OCSE, which in turn leads to a decline in MDRPI prevention behavior.

According to Bandura’s SCT, environmental (workload), personal (self-efficacy), and behavioral factors (preventive practices) interact cyclically within a structure of reciprocal determinism [

16]. The findings of this study support this theory. Specifically, rather than environmental stressors such as workload directly affecting the behavioral factor of MDRPI prevention practices, a more plausible pathway emerged in which they indirectly affect these practices via the personal factor of OCSE. This demonstrates that even when nurses perform the same tasks in the same environment, the degree to which they perceive they can handle the work situation significantly affects their actual behavioral performance. Previous studies have also reported that higher self-efficacy positively influences coping ability, resilience, and sustained preventive practices in stressful situations [

30,

31], which is consistent with the findings of this study.

In the Korean clinical environment, the establishment of the Korean Association of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses (KAWOCN) in 2000 and the subsequent introduction of the WOCN system have led to the specialization of pressure injury management. Tasks previously handled by general nurses have increasingly shifted to WOCNs, who provide specialized care for chronic wounds—including assessment, dressing changes, education, and follow-up management for complications such as pressure ulcers, diabetic foot, and stomas [

32]. However, according to the National Wound Care Strategy update (2023), the responsibility for pressure injury prevention and routine management lies with all clinical nurses, not solely with WOCNs [

33]. The WOCN’s role is primarily to establish practice standards, provide education, and offer expert consultation [

33,

34,

35]. While ward nurses are responsible for the daily processes of MDRPI prevention—such as verifying device placement, performing skin assessments, and applying prophylactic dressings [

36]—a problematic perception persists. Some ward nurses misperceive MDRPI prevention as falling exclusively within the WOCN’s domain. Consequently, they tend to view it as having a lower priority than other nursing interventions, leading to missed preventive care and inconsistent implementation [

5,

37]. This observation is consistent with global trends indicating that role ambiguity often leads to the deprioritization of preventive care [

38]. Collectively, these contextual factors partially explain our finding that simply reducing workload does not directly translate into improved prevention practices. This suggests that the barrier to implementation is not merely the quantity of work (workload) but also involves qualitative factors such as the meaning attributed to the task, role perception, and self-efficacy.

Furthermore, insufficient knowledge or underestimation of the importance of MDRPI prevention has been shown to hinder preventive practice [

40]. Previous studies indicate that when nurses clearly understand the clinical significance of MDRPI and recognize their preventive role, their confidence in performing related tasks increases, which subsequently strengthens preventive behaviors [

21,

41,

42]. Given that OCSE emerged as the key mediator in this study, interventions must go beyond simple workload reduction and instead focus on systematically enhancing nurses’ knowledge and confidence. Because MDRPI can develop rapidly and early assessment is critical, organizational support is essential to establish preventive practice as a core nursing competency.

Based on these findings, we recommend three practice-level strategies. First, self-efficacy–enhancing educational programs—including simulation-based training, skill rehearsal, and mastery experiences—should be incorporated into MDRPI prevention initiatives. Such interventions have been shown to improve both perceived capability and actual preventive behavior. Second, clarification of preventive roles and standardization of MDRPI protocols are essential, particularly in settings where WOCNs and general nurses share responsibilities. Clear task delineation and reliable practice guidelines can reduce cognitive burden and promote consistent preventive actions. Third, organizational reinforcement, including managerial feedback, real-time safety reminders, and adequate staffing to reduce competing cognitive demands, can strengthen nurses’ confidence and sustain preventive performance even under high workload conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study was conducted to identify the mediating role of OCSE in the relationship between nurses’ workload and MDRPI prevention performance. The analysis revealed that workload did not have a direct effect on MDRPI prevention performance; however, a significant indirect effect was observed through OCSE, confirming a full mediating effect. This indicates that, even within the same work environment, nurses’ perceptions of their ability to cope with work situations are a key determinant of MDRPI prevention performance. Therefore, improving prevention performance cannot be achieved solely through organizational interventions that adjust workload; rather, a multidimensional approach that strengthens nurses’ individual capacities is required. In particular, OCSE was identified as a key psychological and cognitive mediator linking the environmental factor of workload with the behavioral outcome of prevention performance, serving as a crucial protective factor that enables nurses to sustain preventive activities even in situations of job stress. This finding provides empirical support for the concept of reciprocal determinism proposed by SCT and suggests that consideration of individual factors is essential when designing strategies to enhance nurses’ clinical performance. From a patient safety and quality improvement perspective, these findings underscore that sustainable MDRPI prevention requires integrated strategies that address both organizational conditions and nurses’ psychological resources across the nursing practice continuum. However, this study’s cross-sectional design limits causal interpretation, and caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings because of the inclusion of nurses from a single medical institution in one region. Future studies should adopt multi-center designs that include diverse hospital settings, longitudinal approaches, or causal and path analyses using structural equation modeling. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the patient safety literature by elucidating a theoretically grounded mechanism through which workload influences preventive nursing practice, offering practical implications for quality improvement initiatives aimed at strengthening frontline nursing performance. Nevertheless, this study is significant in that it elucidates the mechanisms linking workload, OCSE, and MDRPI prevention performance, thereby providing empirical evidence to support improvements in MDRPI prevention in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

J.A.K. participated in the design and direction of this study and performed the final revision of the manuscript. H.S.G. analyzed the data and interpreted the results. H.S.G. wrote the original manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by research fund from Dongguk University WISE Campus in 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University WISE Campus (Approval No: DGU IRB 20250008, approval date: 25/04/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dongguk University WISE Campus (Approval No. DGU IRB 20250008). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) announces a change in terminology from pressure ulcer to pressure injury and updates the stages of pressure injury. 2016. Available online: https://npiap.com/.

- National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel; European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers/injuries: clinical practice guideline. The International Guideline. 2019. Available online: https://gneaupp.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/cpg2019edition-digital-nov2023version.pdf.

- Celik, S; Taskin Yilmaz, F; Altas, G. Medical device-related pressure injuries in adult intensive care units. J Clin Nurs. 2023, 32(13–14), 3863–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N; Li, Y; Li, X; Li, F; Jin, Z; Li, T; et al. Incidence of medical device-related pressure injuries: a meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2024, 29(1), 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, JY; Lee, YJ; Korean Association of Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses. Medical device-related pressure ulcer in acute care hospitals and its perceived importance and prevention performance by clinical nurses. Int Wound J 2019, 16 Suppl 1, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M; Sim, Y; Kang, I. Risk Factors of Medical device-related pressure ulcer in Intensive Care Units. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2019, 49(1), 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, MH; Choi, H-R. The characteristics and risk factors of medical device related pressure injury in Intensive Care Unit Patients. J Korean Crit Care Nurs 2023, 16(2), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galetto, S; Nascimento, E; Hermida, PMV; Malfussi, LBH. Medical device-related pressure injuries: an integrative literature review. Rev Bras Enferm. 2019, 72(2), 505–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gefen, A; Alves, P; Ciprandi, G; Coyer, F; Milne, CT; Ousey, K; et al. Device-related pressure ulcers: SECURE prevention. J Wound Care 2020, 29 (Suppl 2a), S1–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H; Choi, S. Protocols and their effects for medical device-related pressure injury prevention among critically ill patients: a systematic review. BMC Nurs 2024, 23(1), 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, MS; Ryu, JM. Canonical correlation between knowledge barriers/facilitators for pressure ulcer prevention nursing variables and attitude performance variables. J Health Inform Stat. 2019, 44(3), 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, MS; Kang, M; Park, KH. Factors influencing professional competencies in triage nurses working in emergency departments. J Korean Biol Nurs Sci. 2022, 24(2), 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfa Mengist, S; Abebe Geletie, H; Zewudie, BT; Mewahegn, AA; Terefe, TF; Tsegaye Amlak, B; et al. Pressure ulcer prevention knowledge, practices, and their associated factors among nurses in Gurage Zone hospitals, South Ethiopia, 2021. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221105571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berihu, H; Wubayehu, T; Teklu, T; Zeru, T; Gerensea, H. Practice on pressure ulcer prevention among nurses in selected public hospitals, Tigray, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2020, 13(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S; Park, JD; Shin, JH. Improvement plan of nurse staffing standards in Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci) 2020, 14(2), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory. In Annals of child development; Vasta, R, Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, 1989; Vol. 6, pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, K; Berse, S. Nursing students’ self-efficacy and clinical decision-making in the context of medication administration to children: a descriptive-correlational study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023, 72, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, JJM; Cheng, MTM; Hassan, NB; He, H; Wang, W. Nurses’ perception and experiences towards medical device-related pressure injuries: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2020, 29(13–14), 2455–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E; Gurlek Kisacik, O. Medical device-related pressure injuries: the mediating role of attitude in the relationship between ICU nurses’ knowledge levels and self-efficacy. J Tissue Viability 2025, 34(1), 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisanti, R; Lombardo, C; Lucidi, F; Lazzari, D; Bertini, M. Development and validation of a brief occupational coping self-efficacy questionnaire for nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 62(2), 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K-S; Yeon, YS; Ram, LB; Ha, HJ; Gee, YS; Yeon, S-N. Concept analysis of clinical nurses’ self-efficacy. J Digit Policy 2023, 2(3), 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pisanti, R; van der Doef, M; Maes, S; Lombardo, C; Lazzari, D; Violani, C. Occupational coping self-efficacy explains distress and well-being in nurses beyond psychosocial job characteristics. Front Psychol. 2015, 6, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J; Li, Y; Lin, Q; Zhang, J; Liu, Z; Liu, X; et al. The effect of occupational coping self-efficacy on presenteeism among ICU nurses in Chinese public hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol 2024, 15, 1347249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y; Park, S; Kang, HR. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the Occupational Coping Self-Efficacy Scale for Nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs 2024, 54(4), 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, RM; Kenny, DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986, 51(6), 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, JH; Lee, EN. Influencing factors and consequences of near miss experience in nurses’ medication error. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2019, 49(5), 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, SG. NASA-Task Load Index (NASA-TLX); 20 years later. Proc Hum Factors Ergon Soc Annu Meet. 2006, 50(9), 904–908. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Aguilar, E; Zevallos-Francia, M; Morales-Garcia, M; Ramirez-Coronel, AA; Morales-Garcia, SB; Sairitupa-Sanchez, LZ; et al. Resilience and stress as predictors of work engagement: the mediating role of self-efficacy in nurses. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1202048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, M; Lee, H; Han, J. The development and evaluation of a protocol-based video education program on medical device-related pressure injury prevention for nurses in a comprehensive nursing care unit. Int Wound J 2025, 22(6), e70692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korean Association of Wound, Ostomy, Continence Nurse (KAWOCN). Introduction to the Korean Association of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses (KAWOCN). 2025. Available online: https://kawocn.or.kr/?pages=kawocn.

- National Wound Care Strategy Programme. National Wound Care Strategy update. 2023. Available online: https://wounds-uk.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/7fd85d3219737fbe053cd084e41894fd.pdf.

- NSW Health. Pressure injury prevention and management: policy directive PD2021_023; Clinical Excellence Commission, NSW Ministry of Health: Sydney (Australia), 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Pressure injury management: risk assessment, prevention and treatment, 4th ed.; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto (ON), 2024; Available online: https://rnao.ca/bpg/guidelines/pressure-injuries.

- Seong, YM; Lee, H; Seo, JM. Development and testing of an algorithm to prevent medical device-related pressure injuries. Inquiry 2021, 58, 469580211050219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A-J; Sook, Jeong Ihn. Performance of evidence-based pressure ulcer prevention practices among hospital nurses. Glob Health Nurs. 2018, 8(1), 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W; Zhang, Q; Chen, Y; Qin, W. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of clinical nurses towards medical device-related pressure injury prevention: a systematic review. J Tissue Viability 2025, 34(1), 100838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K; Bagaoisan, MAP. Research status of the knowledge-attitude-practice theory model in gastric cancer prevention. Cureus 2024, 16(7), e64960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiri, MY; Baker, OG; Alanazi, HI; Alenazy, BA; Alghareeb, SA; Alghamdi, HM; et al. Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices in pressure injury prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2025, 13(11), 11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, SD; Geisler, MZ; Steensgaard, RK; Sogaard, K; Nielsen, SS; Dalsgaard, LT; et al. Self-managed digital technologies for pressure injury prevention in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic scoping review. Spinal Cord. 2025, 63(9), 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayram, A; Sara, Y; Uzgor, F; Ozturk, H. Exploring the relationship between pressure ulcer knowledge and self-efficiency among nursing students: a multicenter study. J Tissue Viability 2024, 33(4), 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).