1. Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are rising globally, accounting for two-thirds of deaths. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) account for the largest share of these deaths. Among NCD-related deaths, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause (with 18 million annual deaths), followed by cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes, respectively. These NCDs share common risk factors- tobacco use, physical inactivity, alcohol abuse, and unhealthy diet. Concurrently, LMICs have the highest burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). As advancements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) have significantly extended the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PWH), a notable intersection between CVD and HIV has emerged, shedding light on the elevated risk of CVD events among PWH [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, extensive cohort studies have found that PWH have a 50% higher risk of incident myocardial infarction compared to the general population. They often fail to meet treatment goals for CVD risk factors [

4,

5].

Among modifiable risk factors, a healthy diet plays a pivotal role in promoting health and preventing diseases by bolstering the immune system and reducing the risk of CVDs [

6]. A recent study in Tanzania showed the importance of plant-based diets in improving various metabolic markers associated with increased risk of NCDs [

7]. Unhealthy diets increase risks of obesity, a multifactorial disease that presents a global public health challenge due to its direct contribution to CVDs and other NCDs [

8].

Fruit and vegetable intake is associated with lower risks of NCDs, such as CVD and certain types of cancer, and with lower overall mortality [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Studies have reported a significant association between F&V intake and the risk of CVDs. Additionally, certain F&V contain naturally occurring compounds, such as flavonoids, known for their antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties, which may reduce the risks associated with chronic diseases and help manage the symptoms of CVDs [

13,

14]. Although the benefits of F&V intake are well documented, there is a dearth of data for vulnerable populations, such as PWH, in LMICs. To add to the body of knowledge in these research areas, we aimed to assess whether there were differences in F&V intake between PWH at higher CVD risk by age and unaffected adults of similar older ages. We also evaluated the association of F&V intake with central obesity in Northwestern Tanzania. These data are crucial in the development and implementation of interventions to reduce CVD risk for PWH.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2018 and May 2019. PWH were recruited from Bugando Medical Center (BMC) HIV Care and Treatment Center (CTC). BMC is one of the four zonal referral hospitals in Tanzania with 950 inpatient beds. The hospital has a catchment area of 14 million people, and the CTC serves over 4000 PWH, typically with monthly clinic appointments and medication refills. Individuals without HIV were recruited from their neighborhoods of residence and sampled from five wards across two districts (Nyamagana and Ilemela) in the BMC’s patient catchment area.

2.2. Participants

Eligible participants in this study were PWH and those who were not with HIV. All participants were 50 years or older. The study received ethical approval from the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CREC/214/2017).

2.3. Procedure

PWH were identified through appointment registers on their respective appointment days at the BMC CTC. PWH were approached by the clinic nurse, informed of the study, and asked if they were interested in obtaining more information. PWH who met the eligibility criteria and who expressed interest were referred to a private research office for informed consent procedures and enrollment.

To conduct community data collection in the different wards, the study team met with the ward chairperson to describe the study’s goals. These meetings were scheduled at least three days before the start of data collection. The chairperson then relayed the information to the community and encouraged them to participate. The chairperson also provided dates and times for the study team’s ward visits. People living in each ward were gathered at one place, and counseling about HIV and NCDs was given to all members before enrollment. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Trained study personnel explained the study objectives in Swahili and obtained signed informed consent. After obtaining informed consent, an adapted version of the World Health Organization (WHO) STEPS Instrument for Non-communicable Disease Risk Factor Surveillance was verbally administered in Swahili by the study personnel. The survey has sections that collect demographic information, family history of NCDs, and behavioral measures, including diet, physical activity, tobacco, and alcohol use.

After completing the survey, study personnel screened all participants using standard procedures for hypertension, obesity via measured body mass index (BMI), and HIV status [

15]. Blood pressure (BP) was measured while the participant was in a sitting position, using an M4 Omron® automatic BP machine. The BP readings were taken from the left arm three times at 3-minute intervals. The average of the two last readings was used to determine hypertension status in the analysis. Hypertension was classified as systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg and or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg [

16].

Recommended daily intake of F&V is at least 400g (5-6 servings daily) [

8]. Daily F&V intake was calculated from the number of servings of F&V consumed per day in a typical week. Inadequate F&V consumption was defined as less than five servings a day, and recommended fruit consumption was two or more servings. The recommended vegetable consumption was three or more servings per day. Central obesity was defined as Waist Circumference (WC) > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women [

17].

2.4. Measurements

Weight measurements were taken using a SECA® weighing scale on a flat, hard surface. Participants were instructed to remove any heavy clothing (such as coats) and shoes, and to stand still on the weighing scale with their hands by their sides. The weighing scales were calibrated daily according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Height was measured with a SECA® stadiometer while the participant was facing directly ahead. Participants were instructed to remove their shoes, caps, or headscarves, keep their feet together, and stand with their arms by their sides. Measurements were taken with heels, buttocks, and upper back in contact with the stadiometer.

HIV diagnosis was performed using rapid tests in a private room. There were two sequential immunochromatographic rapid tests: Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere Medical CO., Ltd., Japan) for screening, followed by UniGold HIV-1/2 (Trinity Biotech, Bray, Ireland) for confirmation of a positive result. The survey and assessments took approximately 60 minutes to complete. Those who tested positive in the community were referred to the BMC CTC for further workup and ART initiation.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data underwent preprocessing and summarization using the R software. Numeric variables were characterized using their mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were summarized using frequency and proportion. Demographic characteristics, as well as vegetable and fruit intake, were compared based on HIV status using Pearson’s Chi-squared test. To assess continuous variables based on HIV status, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed.

Multinomial logistic regression was employed to determine factors influencing diverse fruit and vegetable intake levels. This resulted in two distinct binary logistic models. The first binary logistic model compares the intake of no to one day of fruits per week (fruits = (0-1)) to the intake of two to three days of fruits per week (fruits = (2-3)). The second binary logistic model compares not having one day of fruit intake per week (fruits = (0-1)) to the intake of four to seven days of fruits per week (fruits = (4 -7)). The equations for the submodels are provided below:

Similarly, a multinomial logistic regression model was utilized to analyze vegetable intake. This yielded two binary logistic submodels. The first sub model contrasts the intake of no to one day of vegetables per week (vegetable = (0-1)) with the intake of two to three days of vegetables per week (vegetable = (2-3)). The second sub model compares no to one day of vegetable intake per week (vegetable = (0-1)) to the intake of four to seven days of vegetables (vegetable = (4-7)). The equations for these submodels are as indicated:

3. Results

3.1. Subject Characteristics by HIV Status

Table 1 provided an overview of respondent background characteristics based on their HIV status. Among those with Negative HIV status, 57% identified as Female and 43% as Male. In contrast, among individuals with Positive HIV status, 65% were Female, were 35% are Male. The relationship between level of Education and HIV status were statistically significant (p-value = 0.012). Among Positive HIV cases, a majority (82%) had Primary or no formal education, while 13% had Secondary education. Notably, there was no significant association between Occupation and HIV status. For individuals with Negative HIV status, 64% were Employed, and 36% were Unemployed, while among Positive HIV cases, 69% were Employed, and 31% were Unemployed.

3.2. Fruit and Vegetable Intake by HIV Status

Table 2 revealed that the frequency of consuming fruits per week was notably associated with HIV status (p-value = 0.002). For individuals with Negative HIV status, 38% consumed fruits 0-1 days, 38% consumed them 2-3 days, and 25% consumed them 4-7 days, while for Positive HIV cases, 27%, 36%, and 38% respectively, exhibited these patterns. However, no association was found between the frequency of eating vegetables and HIV status (p-value = 0.2). Among those with Negative HIV status, 9.7% consumed vegetables 0-1 days, 22% consumed vegetables 2-3 days, and 68% consumed vegetables 4 -7 days. For Positive HIV cases, 6.2%, 19%, and 75% respectively, followed these patterns.

3.3. Measuring Body Mass Index (BMI), Blood Pressure (BP), Waist Circumference (WC), and Blood Glucose by HIV Status

Table 3.

Eating habits – Fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake by HIV Status BMI and BP.

Table 3.

Eating habits – Fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake by HIV Status BMI and BP.

| |

HIV status – Without HIV (0), with HIV(1) |

|

| Characteristic |

0, N = 2771

|

1, N = 2601

|

p-Value2

|

| Average systolic (mmHg) |

143 (26) |

138 (26) |

0.010 |

| Average diastolic (mmHg) |

85 (13) |

87 (14) |

0.11 |

| Random blood glucose (mmol/L) |

5.05 (1.42) |

5.68 (1.17) |

<0.001 |

| BMI |

|

|

0.095 |

| Normal |

138 (50%) |

139 (53%) |

|

| Overweight |

122 (44%) |

95 (37%) |

|

| Underweight |

17 (6.1%) |

26 (10%) |

|

| WC (Female) |

|

|

<0.001 |

| High risk |

94 (61%) |

62 (38%) |

|

| Low risk |

61 (39%) |

103 (62%) |

|

| WC (Male) |

|

|

0.6 |

| High risk |

15 (13%) |

9 (10%) |

|

| Low risk |

102 (87%) |

79 (90%) |

|

| Systolic BP |

|

|

0.012 |

| no |

134 (49%) |

155 (60%) |

|

| Yes |

141 (51%) |

105 (40%) |

|

|

1Mean (SD); n (%) |

|

2Wilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s Chi-squared test |

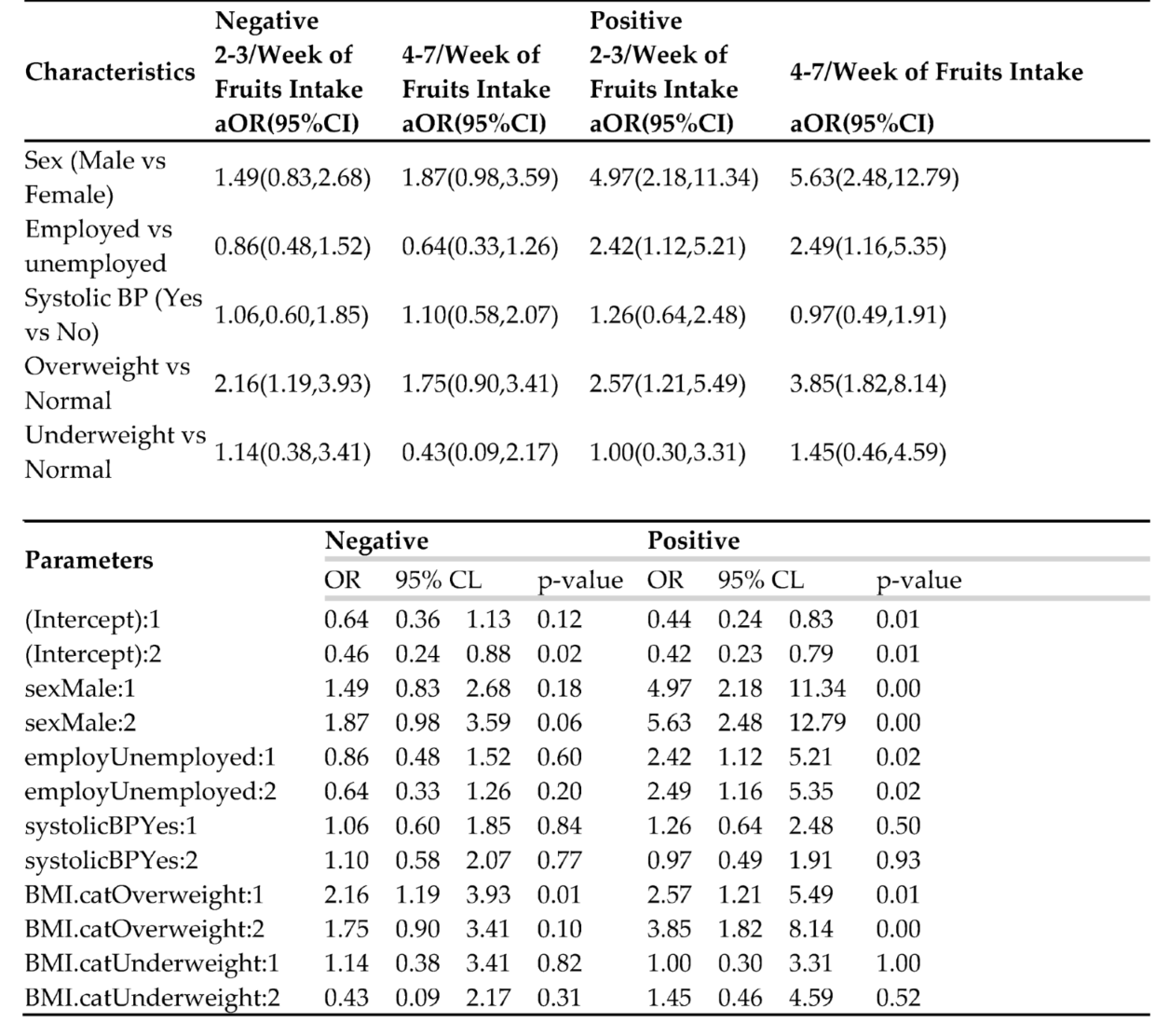

3.4. Fruits

Among individuals who tested positive, males had elevated odds of consuming fruits 2-3 times per week compared to 0-1 times per week (OR=4.97, 95%CI: 2.18,11.34), and similarly, they displayed significantly increased odds of consuming fruits 4-7 times per week compared to 0-1 times per week (OR = 5.63, 95% CI: 2.48, 12.79). Employed individuals demonstrated significantly higher odds of consuming fruits 2-3 times per week versus 0-1 times per week (OR = 2.42, 95% CI: 1.12, 5.21), and they also had substantial increases in odds of consuming fruits 4-7 times per week compared to 0-1 times per week (OR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.16, 5.35). Moreover, individuals classified as overweight displayed significantly elevated odds of consuming fruits 2-3 times per week compared to 0-1 times per week (OR = 2.57, 95% CI: 1.21, 5.49), and similarly, they exhibited significantly heightened odds of consuming fruits 4-7 times per week compared to 0-1 times per week (OR = 3.85, 95% CI: 1.82, 8.14).

Among PWH, being male (OR 5.63, 95% CI, 2.48-12.79), being employed (aOR = 2.49, 95% CI 1.16-5.35), and being overweight (OR = 3.85, 95% CI 1.82-8.14) were each independently associated with consuming fruits > 4 days per week compared with < 1 day. Among PWoH, overweight status (OR = 2.16, 95% CI 1.19-3.93) was also associated with greater fruit intake.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for fruit intake for people with and without HIV.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates for fruit intake for people with and without HIV.

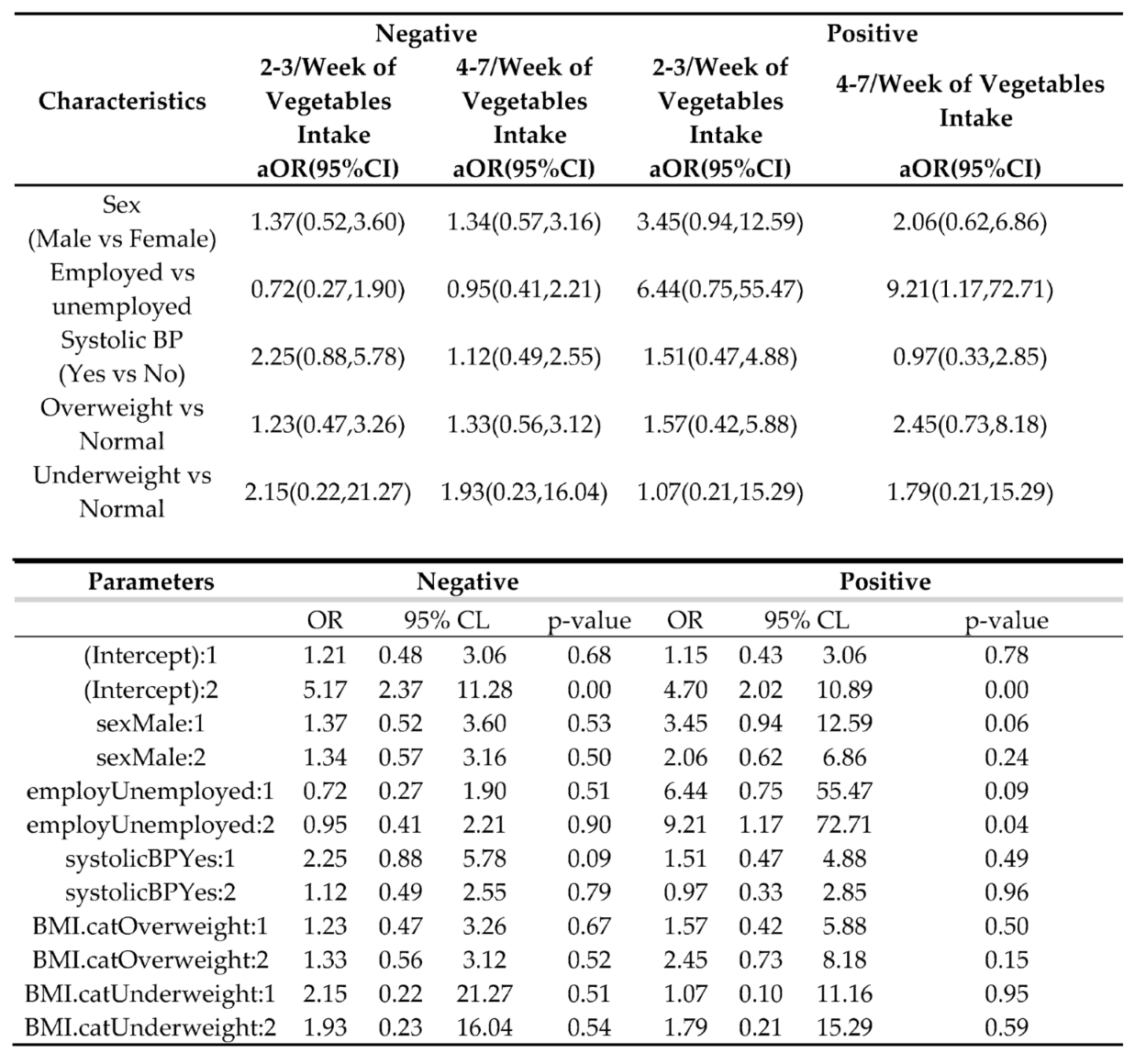

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for vegetable intake for people with and without HIV.

Table 5.

Parameter estimates for vegetable intake for people with and without HIV.

3.5. Vegetables

Among those who tested positive, employed individuals had significantly higher odds of consuming vegetables 4-7 per week vs 0.1 per week. Contrastingly, few variables appeared significant. Meanwhile, PWH employment was associated with higher odds of consuming vegetables > 4 days per week (OR=9.21, 95%CI: 1.17,72.71).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to review whether F&V consumption varied across HIV status for this population of older adults in this Tanzanian region. Studying the nutritional patterns of this region is essential due to chronic disease and cardiovascular risks among PWH. The hypothesis of this research was that PWH would consume less F&V than PWoH due to comorbidities of HIV and malnutrition, along with socioeconomic disadvantage, food insecurity, and inaccessibility. However, the actual results proved there were no statistically significant factors in F&V intake when viewing HIV status. Additionally, there was a similar nutritional intake between PWH and PWoH examined. In the cross-examination study, there was a 15% increase in fruit consumption for PWH 4-7 times weekly than the consumption of the PWoH individuals, disagreeing with our initial presumption. These results point to the possibility that HIV status may not be an important factor in F&V intake due to changes in HIV care and nutrient support in northwestern Tanzania or increased accessibility to F&V sources despite socioeconomic status in the community.

Multinomial regression analysis revealed key findings. Among the PWH group, there developed a positive association between higher BMI, male sex, and employment with increased fruit consumption (>4 weekly). While vegetable consumption did not differ strongly between PWH and PWoH groups, employment conveyed statistically significant associations with increased F&V intake in both groups. In the investigation of how fruit consumption was higher in PWH than PWoH for 4-7 times weekly, and the vegetable associations found, the findings emphasized how employment, and therefore financial security, can be a critical characteristic and hold more control compared to other socioeconomic factors, such as environment, access, and social inequality, when combating food insecurity in northwestern Tanzania.

Despite Tanzania’s nutritional improvement in the context of anemia and growth stunting, the increased urbanization of Tanzania in more rural locations, where HIV may have higher burdens, has increased nutritional diversity in one’s diet. In areas of the northwest, such as Shinyanga, other case trials since the 2000s confirm how food and financial aid interventions under the supervision of the World Food Programme have supported nutritional assessment and counseling (NAC) among adults susceptible to food insecurity. In the literature, there is promise in sustainable interventions that are incorporated into daily HIV care [

18]. Other underresourced environments indicate similar possibilities, endorsing the integration of nutritional diversity into HIV NAC in Tanzania [

19]. If sustained, these measures can offer closure and more evidence as to why HIV status lacked intense associations with F&V differences in this cohort. Data from additional regions across the continent reinforce these findings, with the average F&V intake in Uganda at 1.4 daily servings, based on the 2014 STEPS Survey [

20]. Likewise, in a cross-sectional study in Ethiopia – another country in East Africa – it was reported that nearly 75% of PWH adults consumed F&V less than once daily [

21]. In viewing these uniform patterns across various countries in Africa, it is uncommon for wider gaps between PWH and PWoH to occur, even with respect to socioeconomic status.

Other demographic and socioeconomic conditions still conveyed connections with F&V intake. As employment was positively related to fruit consumption, there is a consensus that financial stability and income increase one’s accessibility to nutrition [

22]. A systematic meta-analysis published this year discovered that lower income, unemployment, and shorter ART periods were correlated with lower nutritional diversity [

23]. Similarly, studies in multiple African settings have documented that diet quality among PWH is generally low, dominated by starchy staples and limited consumption of fruits and vegetables [

24]. Fruit intake was reportedly higher in those with increased BMI, which may be motivated by personal weight management goals and other potential health conditions. Further, women of the PWoH category have higher BMI and central obesity, a previous observation with studies of body composition in East African diets [

25]. Each of these findings explains how various factors of socioeconomic status beyond employment, such as gender and community, influence diet beyond solely HIV status.

In the larger scope of public health, these summaries infer an urgent demand to scale nutrition-based interventions and practices into both HIV and non-HIV chronic treatments. Because of the risk of non-communicable disease among the aging demographic within sub-Saharan Africa, F&V accessibility for adults is essential. NAC and education-related interventions on HIV care have potency in improving nutritional intake outcomes and regulating BMI [

19]. For instance, food-based vouchers and meal assistance plans can improve F&V intake for adults in both sectors of PWH and PWoH. A scoping review summarized how F&V consumption in Tanzania continues to fall short [

26]. Policy measures should consider implementing alternative approaches that not only fortify food systems but also ensure sustainable, equitable reach to food for both adults undergoing and those not undergoing ART.

This study consisted of several limitations. Data on F&V intake were self-reported and therefore subjected to social desirability bias upon recording, including overestimations or underestimations of food consumption due to memory within older populations or in attempts to align with perceived social norms. Moreover, limitations in the cross-sectional design imply causality between nutritional consumption and HIV status. Location-wise, the study was administered in one region local to Lake Victoria in Tanzania; therefore, results are only based in northwestern Tanzania and are not to be generalized to Tanzania entirely or any other African regions without considering discrepancies in economy, food systems, and agricultural context. Upon important review of these limitations, this work corroborates that HIV status is not the sole predictor for fruit or vegetable intake within older adults of northwestern Tanzania. Further studies are recommended for conducting multi-site designs or longitudinal investigations on nutritional consumption trends over longer durations for determining specific F&V produce most consumed per region, community-based interventions based on public policy – such as financial assistance programs – and prolonged food-based programs and their efficacy across aging citizens.

5. Conclusions

This study discovered that older PWH in Northwestern Tanzania indicated increased fruit consumption in comparison to older PWoH in Northwestern Tanzania. Central obesity was more common in women PWoH, delineating nutritional demands and programs for vulnerable populations with the PWH and PWoH cohorts of this study. These findings can prove practical to policymakers, health professionals, and research institutions to implement NAC and risk surveillance into HIV care and support programs, all while scaling obesity and weight management programs for PWoH.

Author Contributions

All authors on this paper meet the four criteria for authorship as identified by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; all authors have contributed to the drafting or been involved in revising the manuscript, reviewed the final version of this manuscript before submission, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The contributions of each author are as follows. Conceptualization, M.M., B.W., and C.M.; methodology, M.M., H.P., and C.M.; software, H.P.; validation, C.M., and V.A.; formal Analysis, H.P.; investigation, M.M., B.W., and C.M.; resources, V.A.; data curation, H.P., V.A., C.M.; writing – original draft preparation, M.M., H.P., V.A., and C.M.; writing – review & editing, M.M., V.A., B.W., M.P., and C.M.; visualization, H.P.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, B.W. and C.M.; funding acquisition, B.W. and C.M.

Funding

This analysis did not receive any external funding. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study received ethical approval from the Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences (CREC/214/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was received from all subjects and organizations about this study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its Supplementary Material. Raw data can be made available upon reasonable request from the Corresponding Author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants at the BMC CTC and those from the Nyamagana and Ilemela districts. We would also like to thank the chairperson of each ward, the medical officers’ representatives in Nyamagana and Ilemela districts, Dr. Wemaeli Mweteni, the CTC staff, and the research assistants who assisted with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

C.M. is a cofounder of YOJO LLC, a software platform company. YOJO LLC did not support any work reported in this article. The other authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| PWH |

People with HIV |

| PWoH |

People without HIV |

| F&V |

Fruit and vegetable intake |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| NCD |

Non-communicable disease |

| LMIC |

Low- and middle-income countries |

| AIDS |

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ART |

Antiretroviral therapy |

| BMC |

Bugando Medical Center |

| CTC |

Care and Treatment Center |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| BP |

Blood pressure |

| WC |

Waist circumference |

| NAC |

Nutritional assessment and counseling |

References

- Haregu, T.N.; Setswe, G.; Elliott, J.; Oldenburg, B. National responses to HIV/AIDS and non-communicable diseases in developing countries: Analysis of strategic parallels and differences. Journal of public health research 2014, 3, jphr. 2014.2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaglehole, R.; Bonita, R.; Horton, R.; Adams, C.; Alleyne, G.; Asaria, P.; Baugh, V.; Bekedam, H.; Billo, N.; Casswell, S. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. The lancet 2011, 377, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So-Armah, K.; Benjamin, L.A.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Feinstein, M.J.; Hsue, P.; Njuguna, B.; Freiberg, M.S. HIV and cardiovascular disease. The lancet HIV 2020, 7, e279–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manavalan, P.; Madut, D.B.; Wanda, L.; Msasu, A.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Thielman, N.M.; Watt, M.H. A community health worker delivered intervention to address hypertension among adults engaged in HIV care in northern Tanzania: Outcomes from a pilot feasibility study. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2022, 24, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, K. Global prevalence of hypertension among people living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension 2017, 11, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation; World Health Organization, 2003; Vol. 916. [Google Scholar]

- Temba, G.S. Immune and metabolic effects of African heritage diets versus Western diets in men: A randomized controlled trial. Nature 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Mente, A.; Dehghan, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Zhang, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Gupta, R.; Mohan, V.; Lear, S. Fruit, vegetable, and legume intake, and cardiovascular disease and deaths in 18 countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.S.C.; Chan, W.; Fielding, R. The associations of fruit and vegetable intakes with burden of diseases: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2019, 119, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, L.A.; Serdula, M.K.; Liu, S. Dietary intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of cardiovascular disease. Current atherosclerosis reports 2003, 5, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Chen, M.; Si, L. Temporal trends in inequalities of the burden of HIV/AIDS across 186 countries and territories. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alissa, E.M.; Ferns, G.A. Dietary fruits and vegetables and cardiovascular diseases risk. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2017, 57, 1950–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muiruri, C.; Wajanga, B.; Kim, C.; Knettel, B.A.; Mhina, C.J.; Bartlett, J.A.; Msangi, J.J.; Msabah, M.A.; Vilme, H.; Kalluvya, S. Correlates of blood pressure awareness, treatment, and control among adults 50 years or older by HIV status in Northwestern Tanzania. Current hypertension reports 2022, 24, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flack, M. Blood pressure and the new ACC/AHA hypertension guidelines. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ian, J. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfay, F. Characteristics and impacts of nutritional programmes to address undernutrition of adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of evidence. BMJ Open 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezenwosu, I. Effect of nutrition education on dietary diversity among HIV Patients in Southeast, Nigeria. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyimba, T. The cardiometabolic profile and related dietary intake of Ugandans living with HIV and AIDS. Frontiers 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneya, D. Fruits and vegetables dietary intake and its estimated consumption among adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in health facilities in Northcentral Ethiopia: A multi-facility cross-sectional study. frontiers in Nutrition 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mornah, L. Magnitude and Predictors of Dietary Diversity among HIV-Infected Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy: The Case of North-Western, Ghana. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewudie, B. Low dietary diversity and associated factors among adult people with HIV patients attending ART clinics of Ethiopia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Research and Therapy 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, K. Associated factors of diet quality among people living with HIV/AIDS in Ghana. BMC Nutrition 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malindisa, E. Dietary patterns and diabetes mellitus among people living with and without HIV: A cross-sectional study in Tanzania. frontiers in Nutrition 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amunga, D. Diets, Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Nutritional Status in Tanzania: Scoping Review. Wiley Online Library 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Respondent background characteristics by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status.

Table 1.

Respondent background characteristics by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status.

| |

HIV Status - Without HIV (0), with HIV (1) |

|

| Variable |

0, N = 2771

|

1, N = 2601

|

p-Value2

|

| Sex |

|

|

0.046 |

| Female |

158 (57%) |

167 (65%) |

|

| Male |

119 (43%) |

88 (35%) |

|

| Level of Education |

|

|

0.012 |

| College |

6 (2.2%) |

13 (5.0%) |

|

| Primary or None |

252 (91%) |

214 (82%) |

|

| Secondary |

19 (6.9%) |

33 (13%) |

|

| Occupation |

|

|

0.2 |

| Employed |

177 (64%) |

180 (69%) |

|

| Unemployed |

100 (36%) |

80 (31%) |

|

|

1n (%) 2Pearson’s Chi-squared test |

Table 2.

Eating habits – Fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake by HIV Status Eating habits - F&V intake.

Table 2.

Eating habits – Fruit and vegetable (F&V) intake by HIV Status Eating habits - F&V intake.

| |

HIV Status – Without HIV (0), with HIV (1) |

|

| Variable |

0, N = 2771

|

1, N = 2601

|

p-Value2

|

| Number of days of fruits consumption in a week |

|

|

0.002 |

| 0 - 1 |

104 (38%) |

69 (27%) |

|

| 2 - 3 |

105 (38%) |

92 (36%) |

|

| 4 - 7 |

68 (25%) |

98 (38%) |

|

| Number of days of vegetables consumption in a week |

|

|

0.2 |

| 0 - 1 |

27 (9.7%) |

16 (6.2%) |

|

| 2 - 3 |

61 (22%) |

50 (19%) |

|

| 4 - 7 |

189 (68%) |

194 (75%) |

|

|

1n (%) |

2Pearson’s Chi-squared test

WC:

Systolic BP was classified as measurements of Average systolic BP was significantly higher in individuals with Negative HIV status (143 mmHg) compared to Positive status (138 mmHg) (p-value = 0.010). Random blood glucose levels differed significantly, with Negative HIV status individuals having lower levels (5.05 mmol/L) compared to those with Positive status (5.68 mmol/L) (p-value < 0.001). While BMI distribution did not show a significant difference between the two HIV statuses, WC in females was associated with HIV status, indicating that 61% of those with a Negative HIV status were at high risk. Contrastingly, 38% of the Positive cases showed a high risk (p-value < 0.001). However, WC in males did not exhibit a significant association with HIV status. Lastly, systolic BP indicated a substantial difference between the two HIV statuses, with more individuals with a Negative HIV status having systolic BP (51%) compared to those with a Positive status (40%) (p-value = 0.012). These variables were included as covariates in the multinomial models assessing fruit and vegetable intake. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |