1. Introduction

The rapid identification, classification, and surveillance of viral pathogens remain central challenges in epidemiology, public health, and molecular virology (Shen et al., 2025). Despite unprecedented advances in sequencing technologies, the analytical workflows required to compare and interpret viral genomic data continue to be limited by methodological bottlenecks inherent to multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and model-based phylogenetics. These constraints become particularly pronounced during outbreaks, where the need for rapid, scalable, and objective relationship estimation competes with the complexity, diversity, and volume of viral genomic data (Saada et al., 2024). Traditional approaches depend on explicit residue-based homology assumptions that often fail in the presence of high mutation rates, frequent recombination, genome segmentation, and rapid intra-host diversification. The need to address this gap for many clinically relevant and public health-risk viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, dengue, alphainfluenza, and measles viruses, remain critical.

Although alignment-free and machine learning-based phylogenetics have emerged as promising alternatives, most existing frameworks remain restricted to compositional or frequency-based k-mer methods that overlook translation-level constraints that shape viral genome evolution (Zhang et al., 2017). As demonstrated previously, translation awareness represents an essential biological dimension that connects genotype to phenotype and enables more faithful discrimination of sequence changes that meaningfully affect viral function, transmissibility, and evolutionary trajectory (De los Santos, 2025a). The absence of this dimension can hinder the accurate clustering and classification of viral genomes, especially in pathogens with evolutionary fitness shaped strongly by codon usage patterns, synonymous-to-nonsynonymous substitution imbalance, and frameshift-inducing indels.

Covary, a translation-aware, alignment-free phylogenetic framework derived from TIPs-VF (De los Santos, 2025b), was previously shown to organize mutation-, gene-, and genome-level biological data into biologically interpretable clusters with high discriminatory power while requiring only modest computational resources (De los Santos, 2025a). In earlier analyses, Covary successfully processed nearly a thousand whole SARS-CoV-2 genomes within minutes, demonstrating near-linear scalability and immediate applicability for large-scale viral phylogenomics. These foundational results point to an emerging paradigm in which translation-aware vector embeddings may provide a more general, flexible, and scalable approach to viral relationship estimation, taxonomic placement, and functional characterization, particularly in outbreak scenarios where timeliness and accuracy are indispensable.

This report extends the application of Covary to thousands-scale comparative analysis of outbreak-causing viral genomes, encompassing four highly divergent and epidemiologically significant pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2, dengue, alphainfluenza, and measles viruses. Specifically, the aims of this paper are to: (1) evaluate the capacity of Covary to discriminate and classify viral genomes; (2) demonstrate the scalability of Covary for thousands-scale whole-genome viral analyses using modest computational resources; (3) determine whether translation-aware embeddings retain sufficient biological signal to support outbreak-relevant tasks such as pathogen identification, lineage grouping, and taxonomic placement; and (4) demonstrate the utility of Covary as a ready-to-deploy, efficient, and broadly applicable tool for viral detection, surveillance, and genomic epidemiology.

2. Materials and Methods

The complete genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 (taxid: 2697049; n=1000), dengue virus (taxid: 12637; n=1000), alphainfluenza virus (taxid: 197911; n=1000), and measles virus (taxid: 11234; n=1000) were retrieved from The NCBI Viral Genomes Resource (Brister et al., 2015). A combined total of 4,000 genomes from outbreak-causing viruses were used as data input. The accession numbers, additional identifiers, and genome sequences were available at online (

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30927302).

All genomes were acquired using the filter parameters: 1) Virus/Taxonomy = taxid; 2) Nucleotide Completeness= complete; 3) Ambiguous Characters= 0. Nucleotide sequences were downloaded using the “Download a randomized subset of 1,000 records”. Accession numbers were pulled from the record including the Pango lineage for SARS-CoV-2, the subtype for dengue virus, the genotype for alphainfluenza virus, and country of origin for measles virus. The sequences did not undergo pre-processing and were fed directly to Covary v2.1, executed on Google Colab (free tier).

The Covary encoder version 2025-Q4 was used in all experiments (

https://github.com/mahvin92/Covary-encoder). Phylogenomic analysis was performed using default parameters, following the protocol described earlier (De los Santos, 2025a). By default, Covary excluded sequence entries with ‘N’ that resulted in 3,831 total sequences considered valid for comparative whole genome assessment.

PCA was used to visualize the vector embeddings of the genomes. The PCA distance matrix was used to analyze pairwise relationship of the sequences, and the complete hierarchal linkage was used to reconstruct the dendrogram.

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Scale Embedding Reveals Clear Inter-Viral Separation

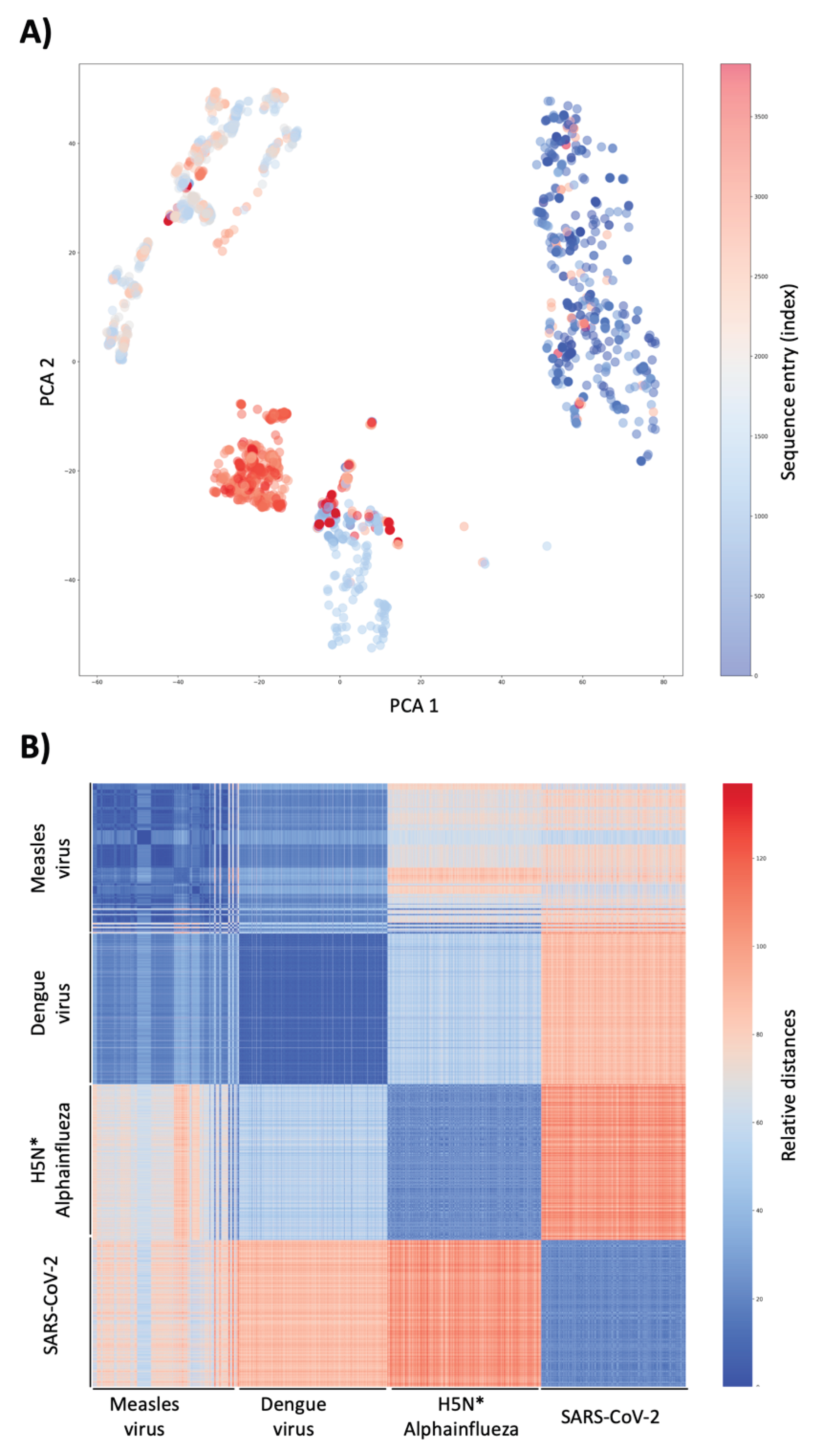

Following translation-aware encoding and dimensionality reduction, principal component analysis (PCA) of the Covary embeddings revealed distinct and well-separated clusters corresponding to the four viral groups included in the analysis: SARS-CoV-2, dengue virus, alphainfluenza virus, and measles virus (

Figure 1A). Despite the use of whole-genome sequences without alignment or preprocessing, genomes from each virus occupied coherent and largely non-overlapping regions of the reduced embedding space. This separation indicates that Covary captures genome-wide compositional and translational features sufficient to discriminate between highly divergent viral taxa.

The emergence of distinct clusters at the PCA level demonstrates that large-scale viral differentiation arises directly from intrinsic sequence representations rather than from curated markers or prior taxonomic labels. Importantly, this structure was observed across nearly four thousand genomes processed simultaneously, highlighting the ability of Covary to preserve inter-viral relationships at thousands-scale while maintaining computational efficiency on a free tier cloud-based infrastructure. This result also offers the utility of Covary for deployment as a cloud-based service.

3.2. Heatmap Visualization Confirms Structured Clustering of Viral Embeddings

To further examine genome-level relationships, a heatmap was generated using the PCA distance matrix of all valid sequences. The resulting heatmap displayed four clearly delineated block-like structures, each corresponding to one of the viral groups included in the dataset. Within each block, embedding similarity was high, whereas similarity between blocks was markedly lower, reinforcing the inter-viral separation observed in the PCA analysis (

Figure 1B).

This pattern indicates that genomes belonging to the same viral species share consistent embedding signatures, while genomes from different viruses exhibit distinct representational profiles. The ability of Covary to generate such structured similarity patterns across thousands of entries suggests that the learned embeddings encode biologically coherent signals that extend beyond low-dimensional projections and remain stable across the complete representation space. This efficiency is expected since Covary was built using TIPs-VF that has been shown to produce embeddings that capture sequence, length, and positional features in addition to codon-boundaries (De los Santos, 2025b).

3.3. Hierarchical Clustering Resolves Viral Classification and Ingroup Structure

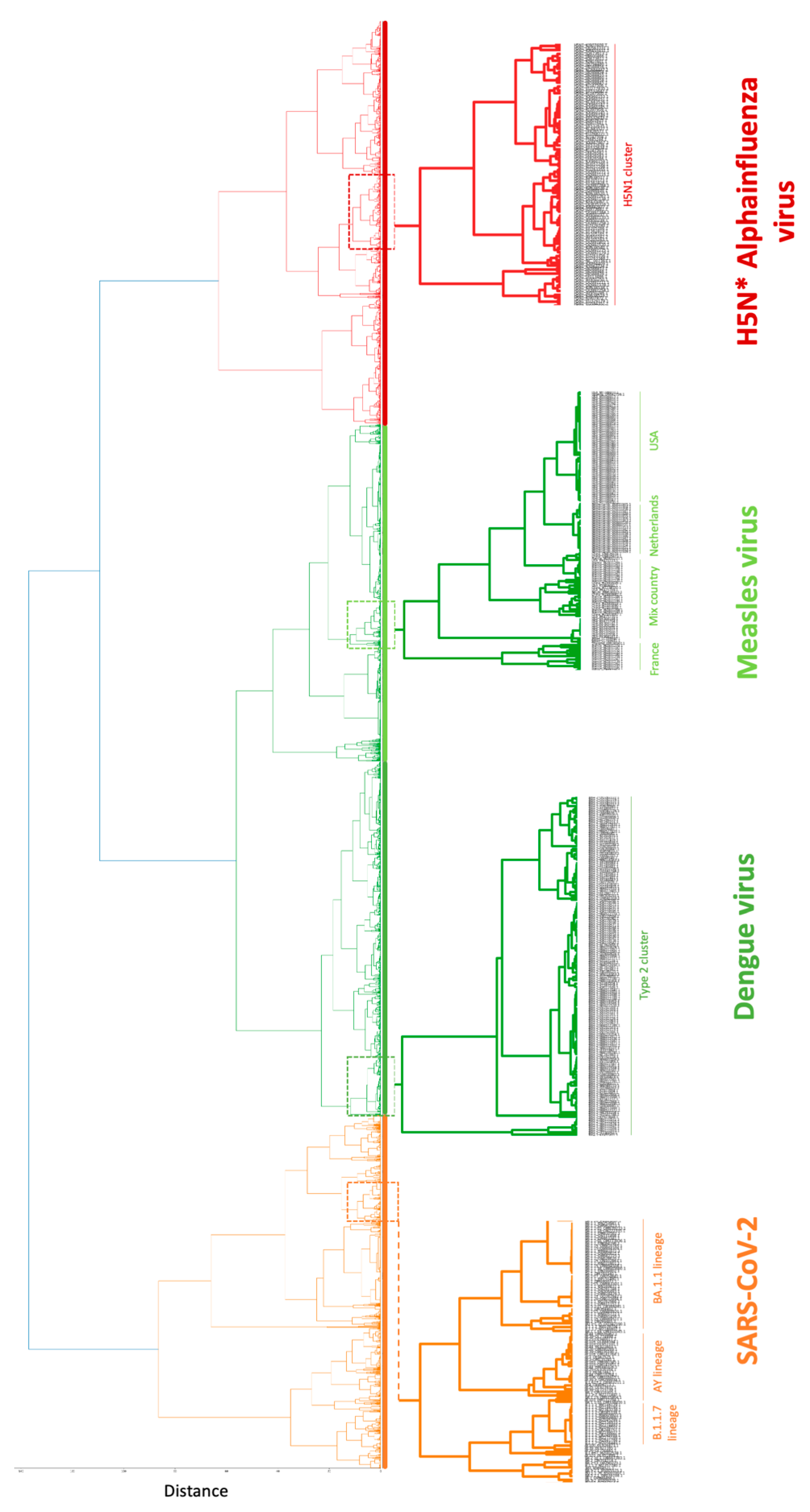

Hierarchical clustering using complete-linkage dendrogram analysis further supported the separation of viral genomes according to their known classifications (

Figure 2). At higher hierarchical levels, the dendrogram resolved four major branches corresponding to SARS-CoV-2, dengue virus, alphainfluenza virus, and measles virus, consistent with both PCA and heatmap analyses. This hierarchical organization demonstrates that Covary embeddings retain sufficient relational structure to support genome-scale clustering across broad evolutionary distances.

At lower hierarchical levels, additional branching patterns emerged within each viral group, indicating the presence of biologically meaningful ingroup diversification. These patterns were consistently and uniformly captured across all viruses examined, suggesting that Covary captures both coarse-grained taxonomic separation and finer-scale genomic variation within viral populations. However, this result needs to be further validated and compared with appropriate evolutionary model and context.

3.4. Ingroup Diversification Reflects Known Epidemiological and Lineage Structure

Detailed inspection of ingroup clustering revealed patterns consistent with established classifications and epidemiological annotations, confirming that the alignment-free result from Covary corroborate with taxonomic placing used in conventional model-based MSA-driven classification. For example, within the alphainfluenza virus group, genomes belonging to the H5N1 subtype formed a distinct and coherent branch nested within the broader H5N* clade structure. This organization reflects known subtype-level differentiation (Yu et al., 2017) and indicates that Covary embeddings are sensitive to subtype-defining genomic features across complete influenza genomes. For measles virus, ingroup clustering based on country of sequence origin showed that genomes from the United States, the Netherlands, and France formed distinct branches, while a separate branch contained genomes originating from mixed geographic sources. This pattern suggests that Covary captures population-level genomic signatures shaped by regional transmission dynamics, while also reflecting diversification or evolution among sequences sampled across different locations (Luo et al., 2025).

Next, in dengue virus, genomes annotated as Type 2 clustered together within a well-defined branch, consistent with established serotype classification (Tariq et al., 2025). This clustering demonstrates that Covary preserves subtype-level organization in viruses where classification is traditionally based on specific genomic regions, despite operating on full alignment-free. Lastly, within the SARS-CoV-2 dataset, genomes corresponding to Pango lineages BA.1.1, AY, and B.1.1.7 formed distinct branches within the overall SARS-CoV-2 cluster. These results indicate that Covary embeddings capture genome-wide variation associated with major lineage diversification events observed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ma et al., 2024).

4. Discussion

The increasing frequency of zoonotic spillover events, the recurrent emergence of novel variants, and the growing need for genome-informed surveillance systems further underscore the importance of developing analytical frameworks capable of providing rapid, unbiased assessment of viral relatedness at whole-genome resolution (Gardy and Loman, 2017; Plowright et al., 2017). Current outbreak response workflows rely heavily on pipelines that require extensive preprocessing, substantial computational infrastructure, or prior model specification, which are features that limit real-time deployment in clinical, field, or resource-limited settings. There remains, therefore, a critical unmet need for a method that is fast, alignment-free, biologically informed, and deployable across widely accessible computing environments.

In this report, Covary satisfied these requirements by processing thousands of complete viral genomes in a single comparative framework while preserving biologically meaningful structure across multiple levels of viral organization. Using a combined dataset of four thousand genomes, Covary rapidly generated translation-aware embeddings that grouped sequences according to their expected taxonomic and epidemiological labels without the use of multiple sequence alignment, explicit evolutionary models, or prior annotation-based constraints. Importantly, this organization emerged directly from intrinsic sequence features encoded at the genome scale, highlighting the capacity of Covary to capture biologically relevant signals across highly divergent viral taxa. Alignment-free methods have proven effective for large-scale viral genome comparison, demonstrating their capacity to handle datasets with diverse genome architectures while maintaining computational efficiency (Zhang et al., 2017).

Across all viruses examined, Covary correctly separated genomes by their respective taxonomic identities, demonstrating robust inter-viral discrimination. Within each viral group, finer-scale structure consistent with known ingroup diversification was also observed. For SARS-CoV-2, Covary resolved clustering patterns that corresponded to Pango lineage assignments, indicating sensitivity to genome-wide variation accumulated during ongoing viral evolution. In dengue virus, where classification is traditionally anchored on serotypes and genotypes, Covary organized whole genomes according to their established subtype groupings, despite the absence of alignment or gene-level segmentation. For measles virus, clustering patterns reflected geographic origin, suggesting that Covary embeddings capture population-level structure shaped by regional transmission dynamics. Similarly, alphainfluenza virus genomes were organized according to known genotype divisions, reinforcing the capacity of Covary to resolve evolutionary structure in large DNA viruses with comparatively lower mutation rates.

Although, there is congruency in the grouping by Covary and conventional viral taxonomy, it is important to note that some subclades in the Covary dendrogram produced a different or unexpected ‘topological dilution’ or mix species within the each respective branch. This highlights again that conventional methods that relied on ‘fragment’ or homology-based classification is being challenged by genome-informed evolution. The inherent differences between marker-based homology and whole-genome alignment-free methods requires greater attention today. The technology to compare and interpret whole genome differences across different viral species and within species group is now accessible. Covary represent a responsible shift towards formalizing the integration of whole genome data in taxonomically and pylogenomically classifying divergence, evolution, and speciation.

The results collectively indicate that translation-aware, alignment-free representations retain sufficient biological signal to support tasks central to viral genomics, including detection, classification, lineage grouping, and taxonomic placement. Unlike conventional workflows that rely on curated marker regions or carefully tuned substitution models, Covary operates directly on complete genomes, enabling uniform treatment of viruses with diverse genome architectures, sizes, and replication strategies. This generality is particularly valuable in outbreak settings, where incomplete knowledge of pathogen biology or rapid emergence of novel variants can compromise alignment-based or marker-dependent approaches. Recent advances in deep learning have shown promise in phylodynamic inference, demonstrating that machine learning frameworks can effectively complement traditional phylogenetic methods while offering substantial computational advantages (Voznica et al., 2022).

A key contribution of this work lies not in proposing a new taxonomic framework, but in demonstrating that Covary can faithfully reproduce expected biological structure at scale. The ability to process thousands of genomes within minutes on modest computational infrastructure underscores the practicality of Covary as a ready-to-deploy analytical system. By eliminating alignment and minimizing pre-processing requirements, Covary reduces both computational overhead and methodological fragility. Thus, making it suitable for integration into rapid surveillance pipelines, preliminary outbreak investigations, and exploratory comparative analyses. The importance of such scalable genomic surveillance systems has been reinforced by recent pandemic experiences, where real-time tracking of viral evolution proved critical for public health decision-making (Gangavarapu et al., 2023).

It is important to emphasize that the clustering patterns produced by Covary reflect genome-wide relational signatures rather than explicit evolutionary timelines or substitution-rate estimates. As such, branch lengths and distances should be interpreted as measures of vector-space dissimilarity rather than evolutionary time. This distinction is consistent with other alignment-free and machine learning-based phylogenomic frameworks and does not diminish the utility of Covary for classification and comparative inference. Instead, it highlights a complementary analytical paradigm that prioritizes scalability, robustness, and biological relevance over strict model-based reconstruction.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although Covary tolerates substantial sequence variability, entries containing ambiguous nucleotides were excluded by default, reducing the effective dataset size. While this ensures consistency in encoding, future iterations may incorporate ambiguity-aware representations to accommodate lower-quality surveillance data. Second, the present analysis focuses on expected grouping behavior rather than exhaustive benchmarking against alignment-based phylogenetic methods. Such comparisons, while valuable, were intentionally deferred to maintain focus on demonstrating scalability and practical deployment. Third, manual inspection remains part of the current workflow for selecting representative clustering outputs, although automation of best-fit tree selection is already under development. Fourth, the results of Covary has not been further examined by pathologic, epidemiologic, and evolutionary modeling. Future works need to provide benchmark correlation with known phylogenetic standards/model.

Despite these limitations, the findings presented here support the broader vision of Covary as a large-scale biological framework for genome-scale viral analysis. By demonstrating rapid, thousands-scale processing across multiple outbreak-causing viruses, this report reinforces the role of translation-aware, alignment-free approaches as viable and effective tools for modern viral genomics. As genomic surveillance continues to expand in volume and urgency, methods that balance biological fidelity with computational efficiency will become increasingly indispensable.

5. Conclusions

Covary enables rapid phylogenomic analysis across thousands of viral genomes while preserving meaningful taxonomic structure. Its ability to operate without alignment, process complete genomes directly, and run on widely accessible computing platforms positions it as a practical tool for outbreak monitoring, public health response, and large-scale comparative virology. This work provides a clear demonstration that translation-aware machine learning frameworks can meet the demands of contemporary viral genomics, offering a scalable and biologically informed alternative to conventional phylogenetic workflows.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

All data not available from the GitHub repository of Covary can be obtained from

the author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brister, J. R.; Ako-adjei, D.; Bao, Y.; Blinkova, O. NCBI Viral Genomes Resource. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 43, D571–D577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De los Santos, M. Covary: A translation-aware framework for alignment-free phylogenetics using machine learning; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory., 2025a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Santos, M. I. TIPs-VF: An augmented vector-based representation for variable-length DNA fragments with sequence, length, and positional awareness; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory., 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangavarapu, K.; Latif, A. A.; Mullen, J. L.; Alkuzweny, M.; Hufbauer, E.; Tsueng, G.; Haag, E.; Zeller, M.; Aceves, C. M.; Zaiets, K.; Cano, M.; Zhou, X.; Qian, Z.; Sattler, R.; Matteson, N. L.; Levy, J. I.; Lee, R. T. C.; Freitas, L.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Hughes, L. D. Outbreak.info genomic reports: scalable and dynamic surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 variants and mutations. Nature Methods 2023, 20, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardy, J. L.; Loman, N. J. Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nature Reviews Genetics 2017, 19, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Shen, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Spatial–temporal pattern and drivers associated with measles resurgence from 2018 to 2023: a global perspective from 192 countries. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e001912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, K. C.; Castro, J.; Lambrou, A. S.; Rose, E. B.; Cook, P. W.; Batra, D.; Cubenas, C.; Hughes, L. J.; MacCannell, D. R.; Mandal, P.; Mittal, N.; Sheth, M.; Smith, C.; Winn, A.; Hall, A. J.; Wentworth, D. E.; Silk, B. J.; Thornburg, N. J.; Paden, C. R. Genomic Surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Circulation of Omicron XBB and JN.1 Lineages — United States, May 2023–September 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2024, 73, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowright, R. K.; Parrish, C. R.; McCallum, H.; Hudson, P. J.; Ko, A. I.; Graham, A. L.; Lloyd-Smith, J. O. Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2017, 15, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saada, B.; Zhang, T.; Siga, E.; Zhang, J.; Magalhães Muniz, M. M. Whole-Genome Alignment: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Krafft, T.; Wang, Q. Progress and challenges in infectious disease surveillance and early warning. Medicine Plus 2025, 2, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, F.; Irfan, M.; Farooq, S.; Iqbal, H.; Atia-tul-Wahab; Khan, I. A.; Iftner, T.; Choudhary, M. I. Dynamics and genetic variation of dengue virus serotypes circulating during the 2022 outbreak in Karachi. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voznica, J.; Zhukova, A.; Boskova, V.; Saulnier, E.; Lemoine, F.; Moslonka-Lefebvre, M.; Gascuel, O. Deep learning from phylogenies to uncover the epidemiological dynamics of outbreaks. Nature Communications 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Ren, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Hu, P.; Qi, W.; Liao, M. Biological Characterizations of H5Nx Avian Influenza Viruses Embodying Different Neuraminidases. Frontiers in Microbiology 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Jun, S.-R.; Leuze, M.; Ussery, D.; Nookaew, I. Viral Phylogenomics Using an Alignment-Free Method: A Three-Step Approach to Determine Optimal Length of k-mer. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).