I. Introduction

The scale of distributed systems has expanded exponentially in recent years[

1]. Their architecture has evolved from traditional monolithic designs to highly dynamic and tightly coupled multi-node clusters. In this process, resource scheduling, link interactions, and service orchestration inside the system have become more frequent. Performance bottlenecks and behavioral anomalies now appear in more subtle and diverse ways. As system workloads become more volatile, call chains deepen, and node heterogeneity increases, traditional anomaly detection methods that rely on static thresholds, single-node metrics, or local features can no longer manage the complexity of real environments. In large-scale systems, even slight latency fluctuations, queue buildup, or resource contention can propagate along service paths. This propagation may trigger cascading performance degradation, making bottleneck localization and anomaly identification highly challenging. Against this backdrop, there is a pressing need for a unified modeling framework that can understand cross-node dependencies and capture temporal dynamics in distributed observability[

2].

In modern large-scale intelligent platforms, the stability of distributed systems plays a foundational role in ensuring reliable and continuous service delivery. As computational workloads grow in scale and complexity, distributed architectures have become the backbone of computer vision [

3,

4,

5], financial analytics [

6,

7,

8,

9], and information retrieval systems [

10,

11,

12,

13]. System stability in this context not only refers to fault tolerance and availability, but also encompasses consistency, latency control, and predictable performance under dynamic and heterogeneous workloads. However, anomalies in distributed systems are not isolated events. Their manifestations are often linked to implicit structural relationships. Current system operation graphs contain high-dimensional structural information such as service call relations, load paths, and resource contention chains. This information governs how anomalies spread and how the system responds. A single-node perspective cannot capture these cross-path coupling effects. Global statistics alone also fail to represent fine-grained node-level disturbances. Moreover, as service topologies change frequently with version iterations, dependencies between nodes become dynamic. Static topology modeling cannot adapt to such complex scenarios. This may lead to structural drift, misclassification, or blind spots. For systems with time-varying structures, non-stationary sequences, and complex dependencies, accurate bottleneck detection requires a joint modeling mechanism. Such a mechanism must combine temporal sensitivity with structural representation to understand both dynamic behaviors and interaction logic across nodes[

14].

At the same time, metric data in distributed systems show clear multi-scale, multi-modal, and noise-perturbed characteristics. Node-level metrics such as CPU, memory, disk, and I/O exhibit different frequencies, unstable fluctuation patterns, and complex dependencies. Link-level indicators such as latency, throughput, and error rates often contain unpredictable transient jitters. Request-level behaviors reflect the burstiness of system workloads[

15]. When an anomaly is caused by local resource contention or link blocking, its root cause is usually hidden in a dynamic cross-node propagation chain. Traditional methods based on window features, simple statistics, or single-dimensional time series fail to capture this origin accurately. To extract meaningful information from such noisy and highly correlated data, it is necessary to build a joint modeling framework that integrates temporal patterns, structural relations, and cross-node behaviors. This foundation is essential for reliable bottleneck identification[

16].

From the perspective of system operation, bottleneck anomalies are structural and propagative. Their impact is not limited to the triggering node. They spread through service chains and eventually degrade overall service quality. Effective early detection and rapid localization require models that can move from local node behaviors to a global system view. These models must capture short-term micro events and long-term trends, as well as potential dependencies within structural relations[

17]. With the growing adoption of cloud native architectures, microservices, and multi-tenant platforms, coupling between services has increased. A bottleneck at a single point can be amplified through dependency structures into a system-level anomaly. This may affect the stability of critical services and the overall operational efficiency. Therefore, studying cross-node spatiotemporal modeling is of practical value for system stability. It also contributes to improving autonomy, robustness, and adaptive capability in distributed systems.

In this context, building a unified framework that integrates cross-node structural relations, captures temporal pattern evolution, and identifies system bottleneck anomalies has become an important research direction for intelligent operations in distributed environments. Such a framework can maintain awareness of dependency patterns even when system topologies change dynamically. It enables models to understand causal behaviors and propagation paths across nodes, avoiding judgments based only on local observations. By jointly modeling temporal dynamics and spatial dependencies, the framework links transient disturbances with structural propagation pathways. This allows anomaly detection to rely on holistic behavioral patterns rather than isolated fluctuations of single metrics. This approach improves bottleneck localization accuracy and provides data-driven support for root cause analysis, resource scheduling, and system design.

II. Proposed Framework

To capture the combined effect of cross-node dependency structures and temporal dynamics in distributed systems, a unified node state representation is first constructed, mapping multi-source monitoring indicator sequences to a shared latent space. Given the original indicator vector A of node i at time t, a nonlinear encoding function is used to generate the basic representation:

is responsible for extracting local trend changes, fluctuation patterns, and resource usage characteristics of nodes. To further capture the short-term and long-term dynamics of node states, the framework introduces a multi-scale temporal feature aggregation mechanism in the time dimension, integrating information from neighboring windows into a stable temporal representation.

Where

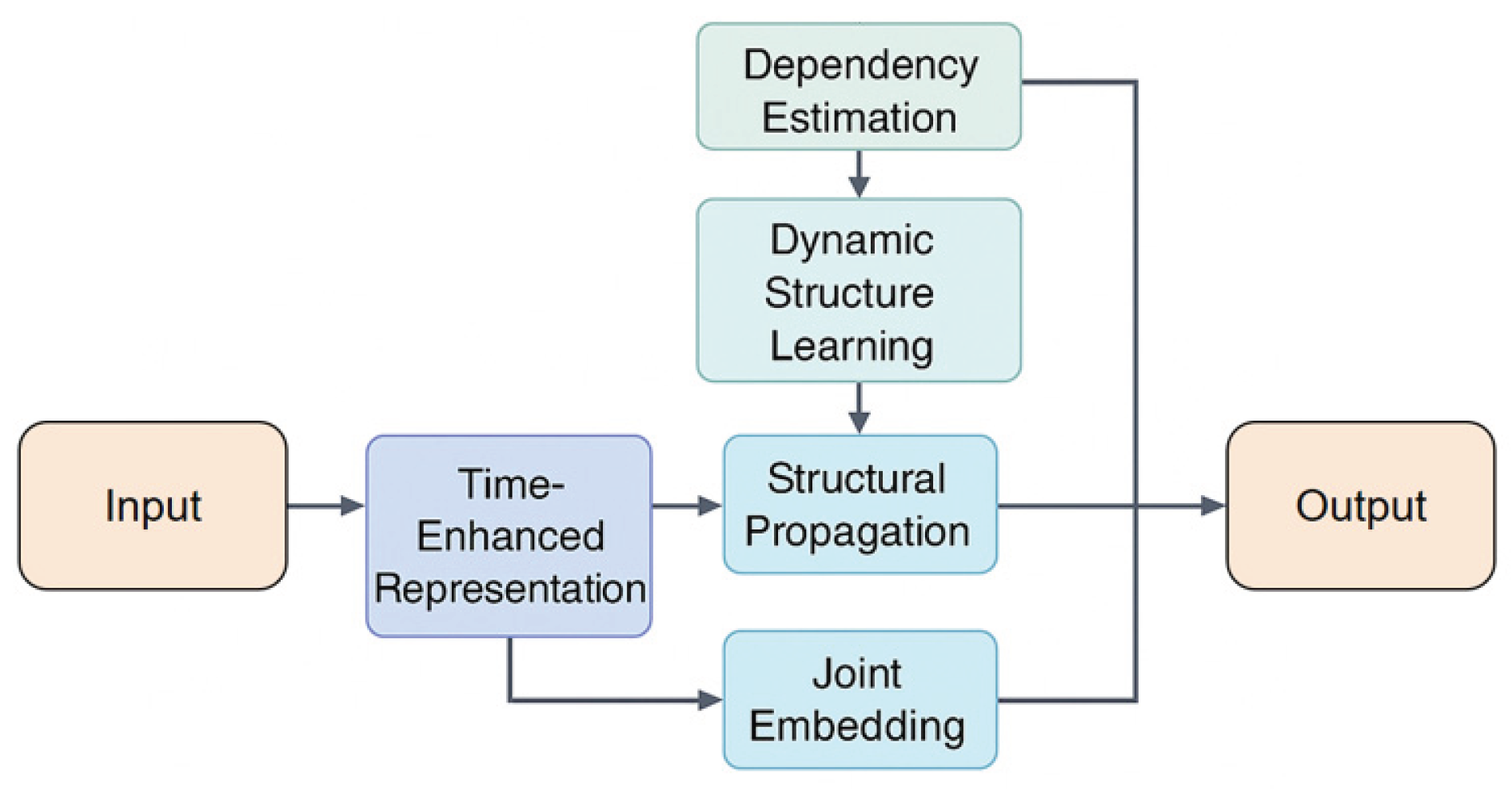

represents the learnable time weight, used to emphasize the importance of different time scales in system dynamics. Its overall model architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

After obtaining the time-augmented features, it is necessary to characterize the dependency structure between nodes to establish a holistic view of the system. The topology of a distributed system can be viewed as a graph that dynamically changes with version evolution, where nodes represent computational entities and edges represent service calls, resource contention, or link interactions. Let

be the dependency adjacency matrix at time t. The framework models the relationships between nodes based on a graph propagation mechanism:

Where is the structure mapping matrix, is the nonlinear activation function, and is the neighborhood of node i. This structure propagation strategy enables the model to understand the strength of dependencies across nodes, path propagation characteristics, and potential coupling relationships, thereby establishing a unified representation method at the overall system scale.

To address the structural drift issue caused by time-varying system topology, the framework further introduces a dynamic dependency estimation module[

18,

19,

20]. By jointly considering temporal features and node interaction behavior, this module enables the dependency structure to be adaptive during the modeling process. This module constructs dynamic structural weights using a similarity function.

Where is a learnable node association metric function. In this way, the system can maintain continuous awareness of structural dependencies even when the topology changes rapidly, load patterns change abruptly, or link relationships are unstable, thus making the modeling results more robust and generalizable.

After integrating temporal features, structural dependencies, and dynamic topology, the framework ultimately needs to map the system state into a stable, anomaly-sensitive representation [

21]. To this end, a joint discriminant function is constructed, fusing the joint embeddings of the temporal and spatial dimensions into the final representation:

And use a unified potential anomaly metric:

Where represents the overall reference state of the system at time t. This joint representation reflects both the local temporal changes of nodes and their relative positions and interactions within the dependency structure, enabling the model to identify potential bottleneck anomalies from the overall behavioral patterns.

III. Experimental Analysis

A. Dataset

This study uses the Alibaba Cluster Trace 2018 dataset as the data source. The dataset is collected from a large-scale Internet production environment. It reflects real distributed systems operating under high concurrency and highly dynamic workloads. It contains detailed monitoring metrics of compute nodes, storage nodes, and the scheduling system over long time windows. These metrics include CPU utilization, memory usage, disk I/O, network latency, container startup behavior, and multi-level events during task execution. The dataset provides a reliable foundation for studying cross-node dependencies and bottleneck patterns in distributed systems.

The structured monitoring logs and task-level event records in this dataset align well with the requirements of anomaly detection in distributed systems. Its characteristics of cross-node operations, multi-task execution, and multi-tenant workloads produce significant structural coupling and complex anomaly propagation paths. The dataset covers real anomalies such as resource contention, link blockage, scheduling imbalance, and container failures. By reconstructing call chains and task dependency graphs across nodes, the spatial structure of system operations can be modeled. By processing time series monitoring metrics, the dynamic behavior of the system under varying workloads can be described. These properties offer complete input data for subsequent spatiotemporal joint modeling.

Alibaba Cluster Trace 2018 also provides high-resolution data over a long time span. This allows models to learn short-term disturbances, periodic patterns, and structural drift across multiple temporal scales. Its open availability ensures reproducibility. The rich node-level and system-level metrics create a suitable environment for deep modeling of cross-node dependencies and bottleneck anomalies. These combined characteristics make the dataset an ideal choice for research on bottleneck anomaly detection in distributed systems.

B. Experimental Results

This paper first conducts a comparative experiment, and the experimental results are shown in

Table 1.

The experimental results show clear structural differences in the performance of different baseline methods on distributed system anomaly detection. MLP and XGBoost achieve similar overall metrics. However, both models cannot model cross-node dependencies and system topology. They are therefore more sensitive to local noise and single-node fluctuations, which leads to noticeably lower Recall. This indicates that feature mapping methods and statistical learning methods can only capture local node-level patterns. They cannot understand how anomalies propagate inside the system. As a result, some bottleneck anomalies are not detected in time.

Model performance improves as the architecture progresses from one-dimensional convolution to Transformer. 1DCNN can learn local temporal patterns, which gives it better sensitivity to short-term fluctuations than traditional methods. Transformer captures long-range temporal dependencies. This enables it to model global temporal dynamics in system behavior. Transformer therefore achieves clear gains in Recall and F1-Score. These results show that global temporal correlations play an important role in anomaly detection under highly dynamic backend environments. However, these models still lack explicit modeling of structural dependencies across nodes. Their ability to capture link blockage or cross-node performance propagation remains limited.

Compared with all baselines, the proposed spatiotemporal framework with cross-node dependency modeling achieves the highest scores across all four metrics. The model integrates local temporal information, cross-node structural dependencies, and dynamic topology changes at the same time. This design effectively addresses the challenges of complex anomaly propagation and frequent structural drift in distributed systems. The higher Recall and F1-Score show that the framework not only improves detection accuracy but also provides stronger robustness and generalization when identifying bottleneck anomalies. It can judge anomalies from overall behavioral patterns rather than isolated metric deviations. This aligns with the core requirements of spatiotemporal joint modeling for anomaly detection in distributed systems.

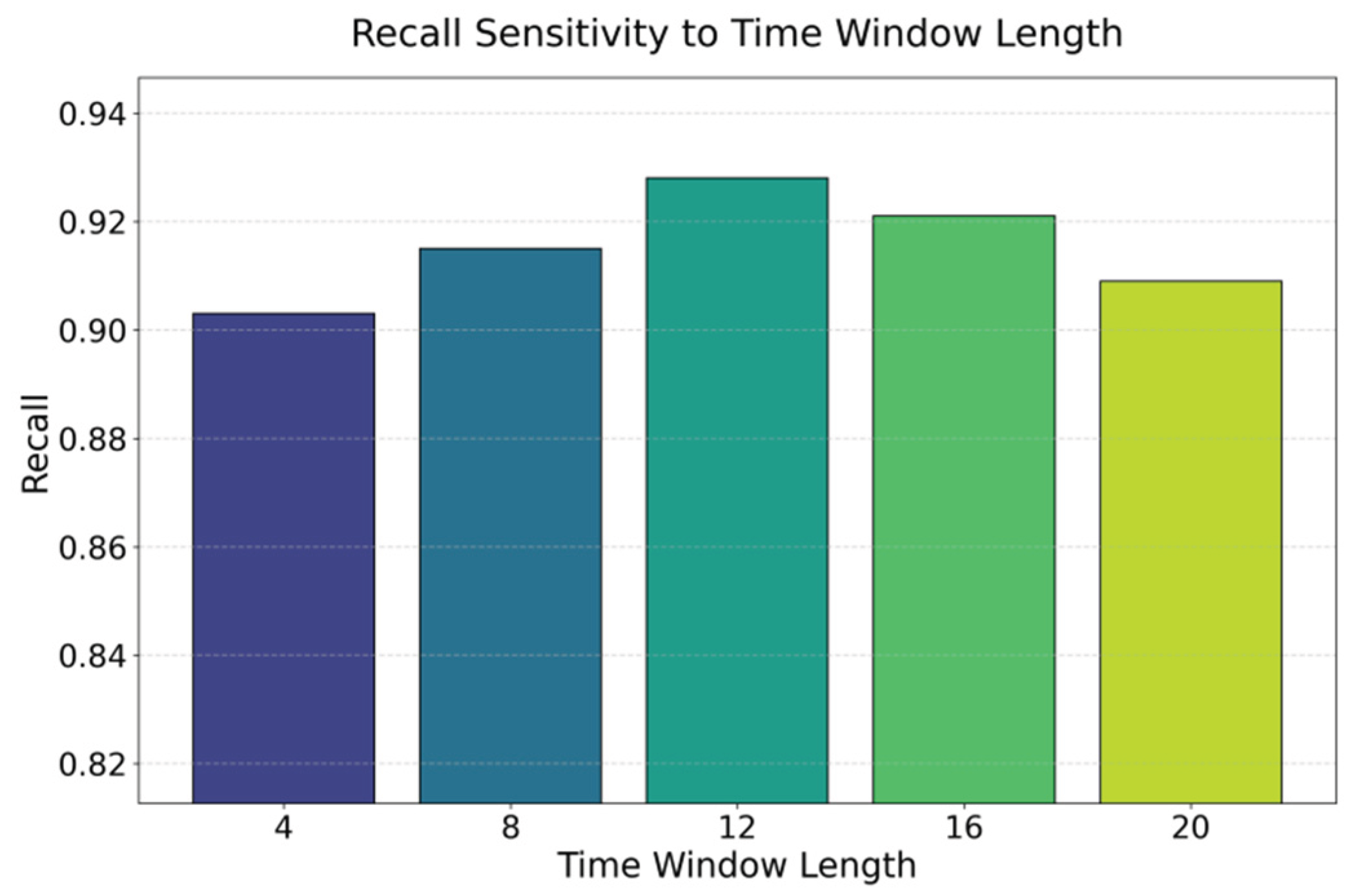

This paper presents an experiment on the hyperparameter sensitivity of the time series window length to the Recall metric, and the experimental results are shown in

Figure 2.

The experimental results show the direct impact of temporal window length on model recall. This demonstrates the importance of temporal modeling in distributed system anomaly detection. When the window length increases from 4 to 12, recall shows a stable upward trend. This indicates that the model can better capture cross-node anomaly propagation patterns when it has access to a longer time range. Short windows fail to cover the key context before and after an anomaly. The model is forced to make decisions based only on local disturbances, which leads to missed bottleneck anomalies.

When the window length reaches 16, recall decreases slightly. This suggests that an overly long time span introduces additional noise. Such noise may come from cross-phase workload fluctuations, unrelated node behaviors, or structural drift. These factors make it harder for the model to focus on essential anomaly signals. In distributed systems, node workloads and call chain behaviors are asynchronous by nature. Excessively long windows can bring irrelevant information into the input sequence, which reduces the model's sensitivity to anomaly propagation paths.

When the window length increases further to 20, the decline in recall becomes more evident. This trend shows that temporal modeling has an appropriate scale range. A small window results in insufficient context. A large window dilutes anomaly features and hides key dependency patterns. Overall, the results confirm that the proposed method must balance temporal scale and noise interference when modeling dynamic relations and cross-node dependencies in distributed systems. The model must capture local disturbances while also identifying anomaly propagation structures effectively.

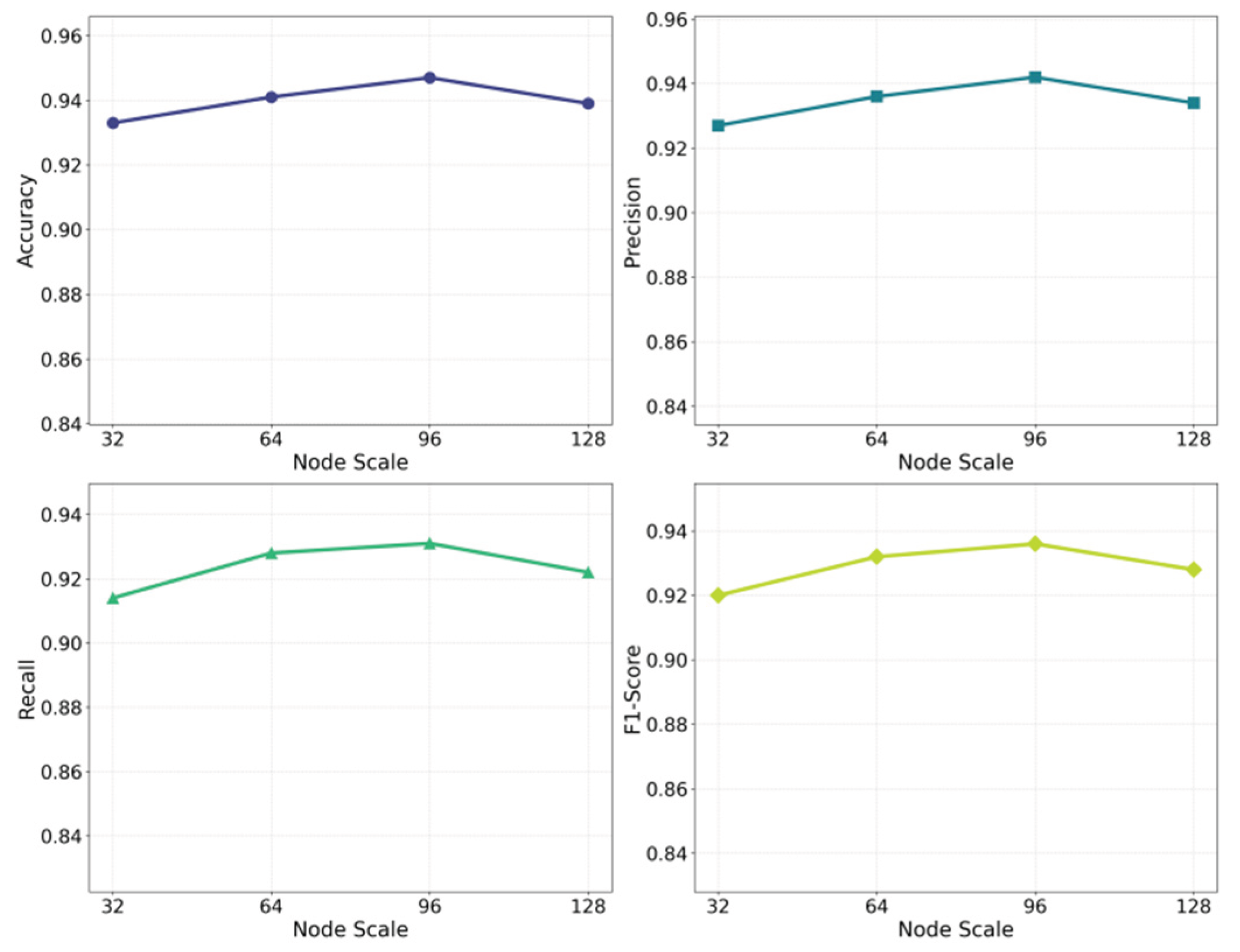

This paper also presents the impact of node size expansion on the experimental results, as shown in

Figure 3.

The experimental results show that the expansion of node scale has a clear impact on model performance across all metrics. This reflects the combined effect of cross-node dependencies and structural complexity in distributed systems. When the system scale increases from 32 nodes to 64 and 96 nodes, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-Score all rise. This indicates that a moderate increase in node scale helps the model capture more complete system interaction information. Dependency paths become clearer within this range. The model can understand anomaly propagation from a broader structural perspective. This leads to improved overall detection performance.

When the number of nodes further increases to 128, all metrics begin to decline. This trend shows that an overly large system scale introduces more complex and sparse dependency patterns. Local noise appears in more positions. Structural drift becomes more frequent. These factors force the model to process many irrelevant or weakly related topological relations when integrating information. The fusion of spatiotemporal features is therefore disturbed. The ability to aggregate anomaly-related features decreases. As a result, the model becomes less sensitive to bottleneck anomalies.

Overall, the results reveal a double-edged effect of system scale in distributed anomaly detection. A moderate scale provides sufficient context and structural dependencies, which help capture anomaly propagation paths. However, an excessively large scale introduces complexity and noise, making it difficult for the model to extract stable spatiotemporal patterns. In highly dynamic multi-node environments, the model must balance structural expressiveness and noise robustness to ensure effective identification of bottleneck anomalies.

IV. Conclusion

This study addresses the challenge of anomaly identification in distributed systems operating under highly dynamic workloads, complex topologies, and intensive multi-node interactions. A spatiotemporal framework with cross-node dependency modeling is proposed. The framework integrates multi-scale temporal dynamics with structural dependencies across nodes. It builds a unified representation that reflects the global operating state of the system. This design overcomes the limitation of single-node or single-sequence models that fail to capture anomaly propagation paths. Experimental results show that the framework can effectively identify bottleneck anomalies in distributed environments. It also achieves consistent advantages across multiple metrics and provides a new modeling paradigm for the intelligent operation of complex systems.

The core contribution of this study is the explicit modeling of local temporal variations in node behavior together with structural coupling across nodes. This enables a deeper understanding of system-level anomalies. Through dynamic structure learning and temporal enhancement, the model can handle challenges such as frequent topology changes and unstable dependencies. It can also maintain strong robustness under noisy conditions. This joint modeling strategy extends anomaly detection beyond simple feature deviation. It provides structural insight into anomaly propagation paths and system behavior patterns. It also offers a higher-dimensional perspective for understanding causal relations inside complex systems. At the application level, the framework is highly relevant to high-concurrency systems such as cloud platforms, microservice architectures, container clusters, and distributed databases. As system scale increases and node deployment becomes more distributed, link interactions become more complex.

Future work can explore how to combine structural interpretability with anomaly discrimination more closely. This would allow the model to reveal potential root cause paths while identifying anomalies. As distributed systems expand toward edge environments and multi-cloud architectures operate in parallel, spatiotemporal patterns across regions and scenarios will become more diverse. In response to these trends, the model can be extended to support cross-domain structural transfer, real-time structural updates, and efficient inference in large-scale node environments. These advances would better serve next-generation intelligent operation systems and promote progress toward intelligence, adaptability, and high reliability.

References

- Chen, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, X. Learning Graph Structures With Transformer for Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 9179–9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Babar, M.A. LogGD: Detecting Anomalies from System Logs with Graph Neural Networks. 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security (QRS), China; pp. 299–310.

- Zheng, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H. Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for High-Precision Medical Image Analysis. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods 2024, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, A.; Dai, M.; Hu, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, S.; Du, J. Leveraging Semi-Supervised Learning to Enhance Data Mining for Image Classification under Limited Labeled Data. 2024 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Communication (EIECC), China; pp. 492–496.

- Sun, Q.; Zhang, T.; Gao, S.; Yang, L.; Shao, F. Optimizing Gesture Recognition for Seamless UI Interaction Using Convolutional Neural Networks. 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML), China; pp. 1838–1842.

- Jiang, M.; Xu, Z.; Lin, Z. Dynamic Risk Control and Asset Allocation Using Q-Learning in Financial Markets. Trans. Comput. Sci. Methods 2024, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Xu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Guo, X.; Jiang, M. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Risk Assessment and Control in Financial Derivatives: Exploring Deep Learning and Ensemble Models. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods 2024, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z. Multi-Source Data-Driven LSTM Framework for Enhanced Stock Price Prediction and Volatility Analysis. Journal of Computer Technology and Software 2024, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ma, K.; Wu, Y.; Sun, M. Advanced Risk Prediction and Stability Assessment of Banks Using Time Series Transformer Models. BDEIM 2024: 2024 5th International Conference on Big Data Economy and Information Management, China; pp. 657–661.

- Hu, J.; Bao, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Y. Accurate Medical Named Entity Recognition Through Specialized NLP Models. 2024 6th International Conference on Frontier Technologies of Information and Computer (ICFTIC), China; pp. 578–582.

- Qi, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Zheng, H.; Wang, C. Optimizing Multi-Task Learning for Enhanced Performance in Large Language Models. 2024 4th International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer Communication (EIECC), China; pp. 1179–1183.

- Liang, A. Personalized Multimodal Recommendations Framework Using Contrastive Learning. Transactions on Computational and Scientific Methods 2024, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Liao, X.; Gao, J.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y. Adaptive Optimization for Enhanced Efficiency in Large-Scale Language Model Training. 2024 6th International Conference on Frontier Technologies of Information and Computer (ICFTIC), China; pp. 1315–1319.

- Zhang, W.; He, P.; Qin, C.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y. A graph attention network-based model for anomaly detection in multivariate time series. J. Supercomput. 2023, 80, 8529–8549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, M. Temporal Logical Attention Network for Log-Based Anomaly Detection in Distributed Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 7949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Shi, J.; Lin, X.; Gao, Y.; Huang, Y. Optimized edge weighting in graph neural networks for server performance anomaly detection. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Wu, W. Anomaly detection in distributed systems based on Spatio-Temporal Causal Inference. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Self-Supervised Learning in Deep Networks: A Pathway to Robust Few-Shot Classification. 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML); LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1818–1823.

- Du, J.; Liu, G.; Gao, J.; Liao, X.; Hu, J.; Wu, L. Graph Neural Network-Based Entity Extraction and Relationship Reasoning in Complex Knowledge Graphs. 2024 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML), China; pp. 679–683.

- Yao, Y. Self-Supervised Credit Scoring with Masked Autoencoders: Addressing Data Gaps and Noise Robustly. Journal of Computer Technology and Software 2024, vol. 3(no. 8). [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Shen, A.; Hu, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, S.; Du, J. Enhancing Few-Shot Learning with Integrated Data and GAN Model Approaches. 2024 4th International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS), Australia; pp. 443–448.

- Nizam, H.; Zafar, S.; Lv, Z.; Wang, F.; Hu, X. Real-Time Deep Anomaly Detection Framework for Multivariate Time-Series Data in Industrial IoT. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22, 22836–22849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemnath, R. XGBoost-Based Botnet Detection Architecture for IoT Networks in Cloud Platforms. International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, A.; Thambawita, V.; Riegler, M.A.; Halvorsen, P. Supervised Anomaly Detection in Univariate Time-Series Using 1D Convolutional Siamese Networks. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 70980–71006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, S.; Casale, G.; Jennings, N. R. TranAD: Deep Transformer Networks for Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series Data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.07284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).