1. Introduction

Ionizing radiation plays a pivotal role in modern medicine, fundamentally reshaping both diagnostics and therapeutics [

1,

2]. Its utility spans advanced imaging techniques—including roentgenography, computed tomography (CT), and positron emission tomography (PET)—and targeted treatments for malignant and benign pathologies via radiation oncology, radiosurgery, and radionuclide therapy [

3,

4,

5]. Parallel advancements in radioprotection have been essential to these clinical applications. Contemporary research remains focused on optimizing the therapeutic index, striving to enhance clinical outcomes while strictly ensuring safety protocols [

6].

The increasing collective radiation dose, exacerbated by technogenic pollutants and pharmaceutical interactions, contributes to synergistic biological toxicity. The specific outcomes of these combined exposures remain obscured by the mechanistic complexity of the factors involved. Consequently, radiobiological research has evolved significantly since the 1950s, with contemporary methodologies now integrating advanced concepts to characterize these multifactorial interactions [

3].

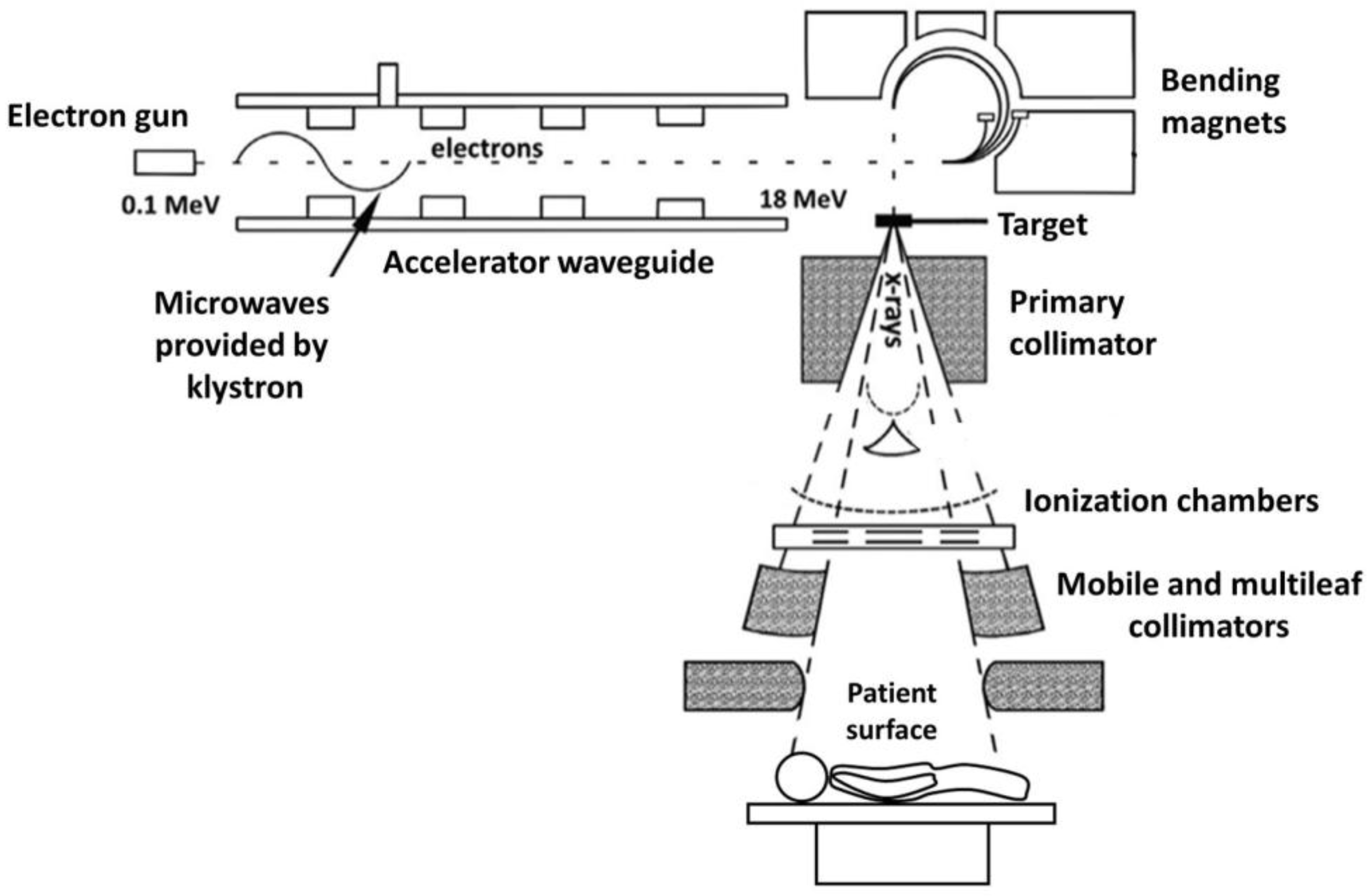

Parallel advancements in radiotherapy technology have transitioned from standard high-energy photon sources—such as X-ray tubes and -emitting radioisotopes—to sophisticated particle acceleration systems. The integration of radiofrequency acceleration, microwave generators (magnetrons, klystrons), and waveguides has enabled the development of linear accelerators (LINACs) and microtrons. These devices facilitate the precise delivery of photons and electrons in the MeV energy range.

Nowadays LINACs are the most commonly used and most universal generators of ionizing radiation used in external beam radiotherapy. The concept of waveguides and linear accelerators originated in the 1920s, but their medical application became prominent post-World War II, when the Varian brothers advanced microwave technology for particle acceleration using radio frequency [

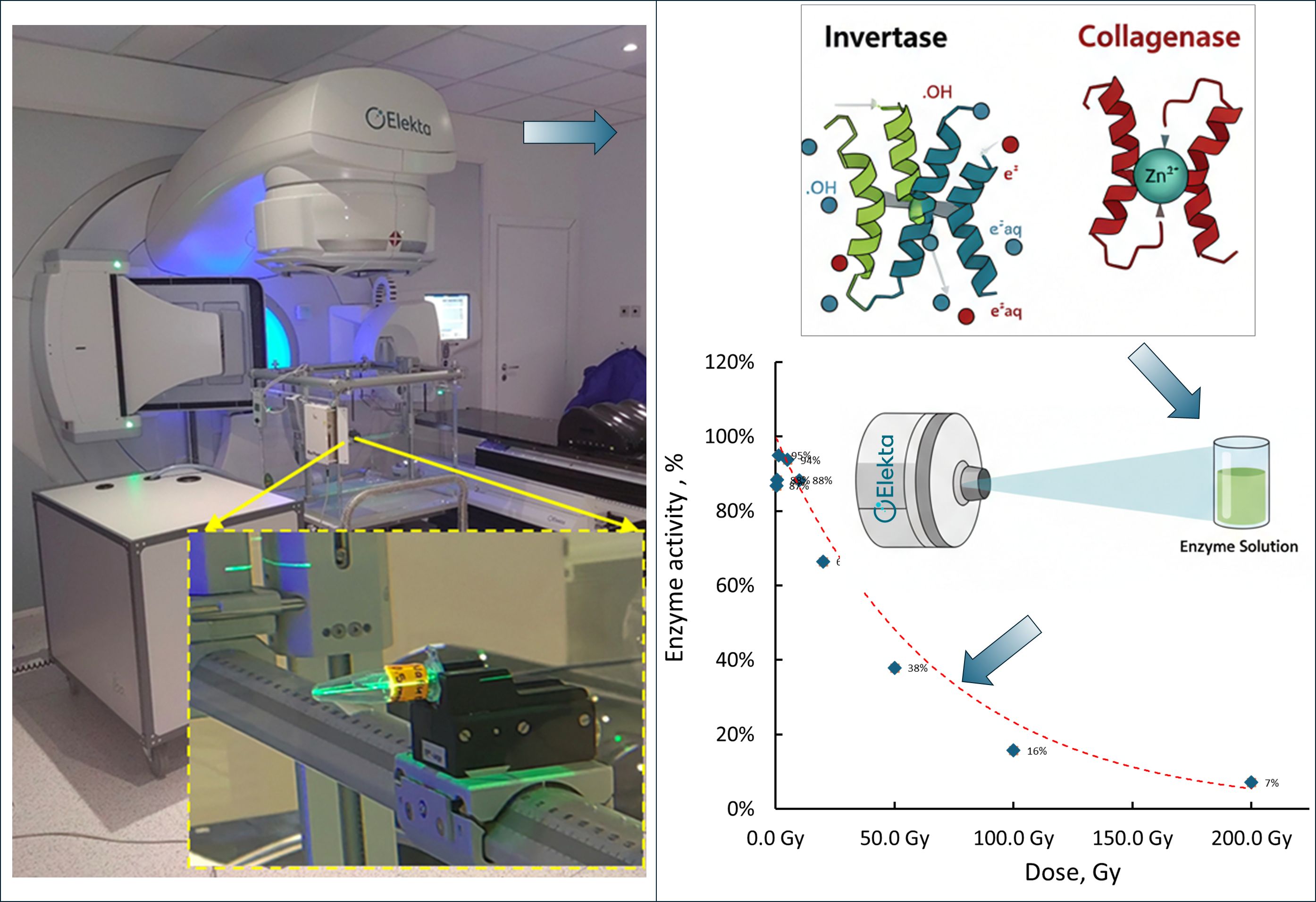

7]. In linear accelerators, electrons are generated by an electron gun, a cathode-anode system that emits electrons from a heated tungsten filament, similar to an X-ray tube. However, instead of being accelerated to an anode target in a single accelerating section by some accelerating (anode) voltage, the electrons are injected in a waveguide and accelerated by intense electromagnetic fields in microwave cavities. The microwave energy is delivered in short-(microseconds) pulses from a klystron or a magnetron. This approach enables acceleration of electrons to relativistic velocities and very high energies with suitable waveguide structures. Medical LINACs produce monoenergetic 4 - 25 MeV electron pencil beams, that can either be used for irradiation with electrons (further applying scattering method, e.g., scattering foils, and collimation for achieving the needed irradiation field dimensions) or, most commonly, for irradiation with high-energy X-rays (directing the electron pencil beam at a high-density (usually tungsten) target. The output photons have a spectrum of energies up to and including the accelerated electrons energy. To form the desired irradiation fields sets of collimators are used, including the now standard multileaf collimators allowing for the creation of very complex radiation fields. The radiation output is monitored with a set of transmission ionization chambers in the radiation beam’s way in the treatment head. LINACs are calibrated in Monitor Units (MUs) in such a way that 1 MU corresponds to certain dose in water at specific reference conditions. Modern LINACs, coupled with state-of-the art dose planning and dosimetric systems allow for precisely controlled and verifiable irradiation and provide significant advantages for accurately irradiating biological samples. (

Figure 1). For this study, we utilized a LINAC to expose enzyme solution samples to precisely defined and verified doses of ionizing radiation, ensuring controlled, reproducible conditions, allowing for reliable evaluation of the effects of ionizing radiation on enzyme activity.

Over the past 30 years, the radiation chemistry of proteins, particularly enzymes, has led to numerous applications which include improvements in experimental protocols as well as the development of theoretical and experimental approaches for studying the structure-function relationships in proteins [

8]. When exposed to ionizing radiation, the chemical changes in protein molecules arise from both direct and indirect effects. In solutions, indirect effects dominate, while direct effects are negligible [

9,

10]. Conversely, in lyophilized states or frozen aqueous solutions, proteins are ionized primarily through direct interactions [

11,

12]. In aqueous solutions, the changes in the structure of protein molecules are due to secondary effects and the fact that proteins react very effectively with primary water free radicals, which are products of radiolysis [

13]. The radiolysis of water is well studied, mainly using the pulse radiolysis method, where short electron pulses produce solvated (hydrated) electrons

,

cations, and excited water molecules (

), which are its primary products [

14]. The radiolysis products and free radicals, particularly solvated (hydrated) electrons

and hydroxyl radicals

, react with protein targets, leading to modifications or fragmentation of the polypeptide chain and its amino acid residues [

15,

16]. Hydrated electrons

are known to react with the carbonyl groups of peptide bonds, causing chain cleavage and the release of ammonia through reactions occurring at the free radical level [

16]. Ultimately, radiolytic reactions and their effects result in the formation of final products that alter the structures of protein molecules and, consequently, their functions.

The impact of radiation on enzymes, even when the dose is controlled, is not a selective method for the occurrence of chemically active radicals. However, it significantly contributes to the study of the catalytic and kinetic properties of enzymes, which are particularly important in modern pharmaceutical chemistry. The method of radiation inactivation of enzymes is a fundamental approach for investigating the effects of ionizing radiation on enzymes involved in key metabolic pathways, and ultimately for assessing the impact on the human body [

15,

17].

A key concept in enzymology (bio-catalysis) is the existence of a finite number of permissible conformational equilibrium states for any enzyme, which occur under strictly defined external conditions. Under low-dose irradiation, conformational changes in the enzyme molecule and its active site are thermodynamically reversible [

18]. These changes can be controlled by precisely defining the irradiation conditions. Such modifications may occur without loss of catalytic activity or with cyclic variations in activity. However, over time, these changes can ultimately lead to the gradual unfolding of the protein molecule, resulting in an eventual loss of the enzyme's catalytic function [

15,

18].

The foundation of the present work is the concept that conformational changes induced by ionizing radiation disrupt the balance of thermodynamically and kinetically stable enzyme structures. This imbalance elicits a chemical response from enzymes to adapt to their new environment while attempting to preserve their structure and enzymatic activity. The number of permissible conformations and the degree of protection are determined by the enzyme's specific function. At higher doses of radiation, however, these conformational changes become irreversible, leading to complete denaturation of the molecule, including its active site, and resulting in irreversible inactivation [

15].

Numerous enzymes are known to be profoundly affected by radiation-induced damage, yet only a few have been extensively studied under exposure to ionizing radiation [

19]. Among those investigated, proteases have received particular attention, primarily due to their critical role in protein processing [

15,

17]. Collagenases (EC 3.2.24.x) are proteolytic enzymes that break down proteins by hydrolyzing peptide bonds. These enzymes target a major component of the extracellular matrix, the collagen, and degrade it into smaller peptides [

20]. Invertase (β-fructofuranosidase, sucrase, EC 3.2.1.26) is an enzyme that belongs to the class of glycosylated enzymes that catalyze the hydrolysis of sucrose into glucose and fructose [

21]. Both collagenases and invertase have been previously studied in radiological investigations. The study by Drózdz et al. examined the effects of gamma-ray exposure on collagen fractions and enzyme activity in rats over 30 days, reporting a significant reduction in total collagen content and changes in collagenase and cathepsin activity [

22]. Separately, Nagrani and Bisby investigated the radiation inactivation of yeast invertase, finding that in dilute aqueous solutions, the rate of inactivation increased with radiation dose, linked to the reactive radical species formed during water radiolysis [

23]. In our recent study [

24], we utilized polarimetric methods to investigate the effects of Co-60 ionizing radiation on invertase activity. By determining kinetic parameters, we observed that the

values of irradiated enzymes were approximately four times higher than those of unirradiated ones. This significant increase suggests that radiation induces chemical modifications resembling competitive inhibitors, thereby reducing enzyme-substrate binding affinity and catalytic efficiency. Additionally, the ratio

further illustrated the diminished overall efficiency of the irradiated invertase.

This article has two distinctive aims. First, it proposes an experimental protocol using a medical linear accelerator (LINAC) suite to achieve homogeneous irradiation of enzyme solutions, enabling precise dose calculation, delivery, and verification. Linear accelerators offer significant advantages over radiation sources like Co-60 for precise dose control in irradiation applications. Unlike the fixed and decaying source of Co-60, LINACs generate X-ray beams through the controlled acceleration of electrons, allowing for dynamic adjustment of beam energy, dose rate, and field shape [

25,

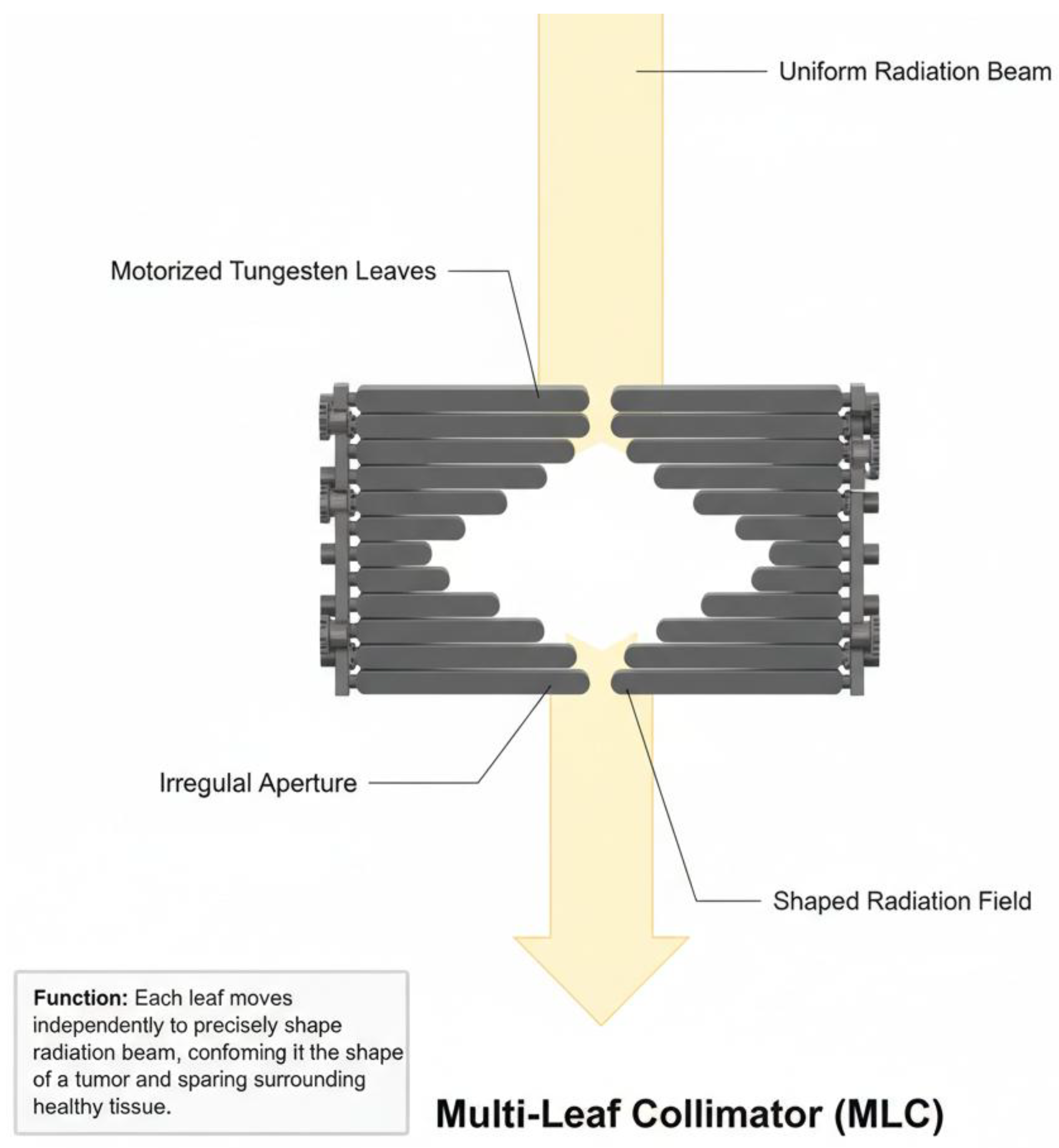

26]. This is achieved through a series of coordinated subsystems, including a magnetron to precisely control radiofrequency waves and electron injection, as well as quadrupole steering magnets and focusing coils that refine the electron beam to a minimal diameter. Beam shaping is further accomplished by a multi-leaf collimator (MLC), shown schematically in

Figure 3, which adaptively modulates the spatial distribution of the X-ray field through the independent motion of multiple tungsten leaves. Crucially, the LINAC incorporates dual independent ionization chambers for continuous, real-time dose monitoring, with an integrated computer system providing synchronized control of all parameters and immediate beam termination upon reaching the prescribed dose. This comprehensive control over beam generation, shaping, and real-time dosimetry ensures superior accuracy, reproducibility, and safety, making LINACs invaluable for applications requiring precise and verifiable radiation delivery, which is often lacking in simpler irradiation setups.

This approach facilitates kinetic studies of enzyme-catalyzed reactions post-irradiation, providing insights into structural and functional changes caused by ionizing radiation. The protocol also allows for the acquisition of kinetic data for reactions catalyzed by enzymes pre-irradiated with varying doses of ionizing radiation, shedding light on potential changes in the active site or molecular structure of the enzymes.

Second, the study investigates how ionizing radiation, delivered in different doses using LINAC, affects the catalytic activities and potentially the molecular structures of two enzymes: invertase and collagenase.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of a multi-leaf collimator (MLC), a beam-modulating device incorporated into linear accelerators. Arrays of independently actuated tungsten leaves move laterally to form an irregular aperture, dynamically shaping the radiation beam to match the target geometry. This adaptive field shaping enables precise control of beam distribution and contributes to the superior accuracy, safety, and reproducibility of LINAC-based irradiation in comparison with fixed sources such as Co-60.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of a multi-leaf collimator (MLC), a beam-modulating device incorporated into linear accelerators. Arrays of independently actuated tungsten leaves move laterally to form an irregular aperture, dynamically shaping the radiation beam to match the target geometry. This adaptive field shaping enables precise control of beam distribution and contributes to the superior accuracy, safety, and reproducibility of LINAC-based irradiation in comparison with fixed sources such as Co-60.

4. Discussion

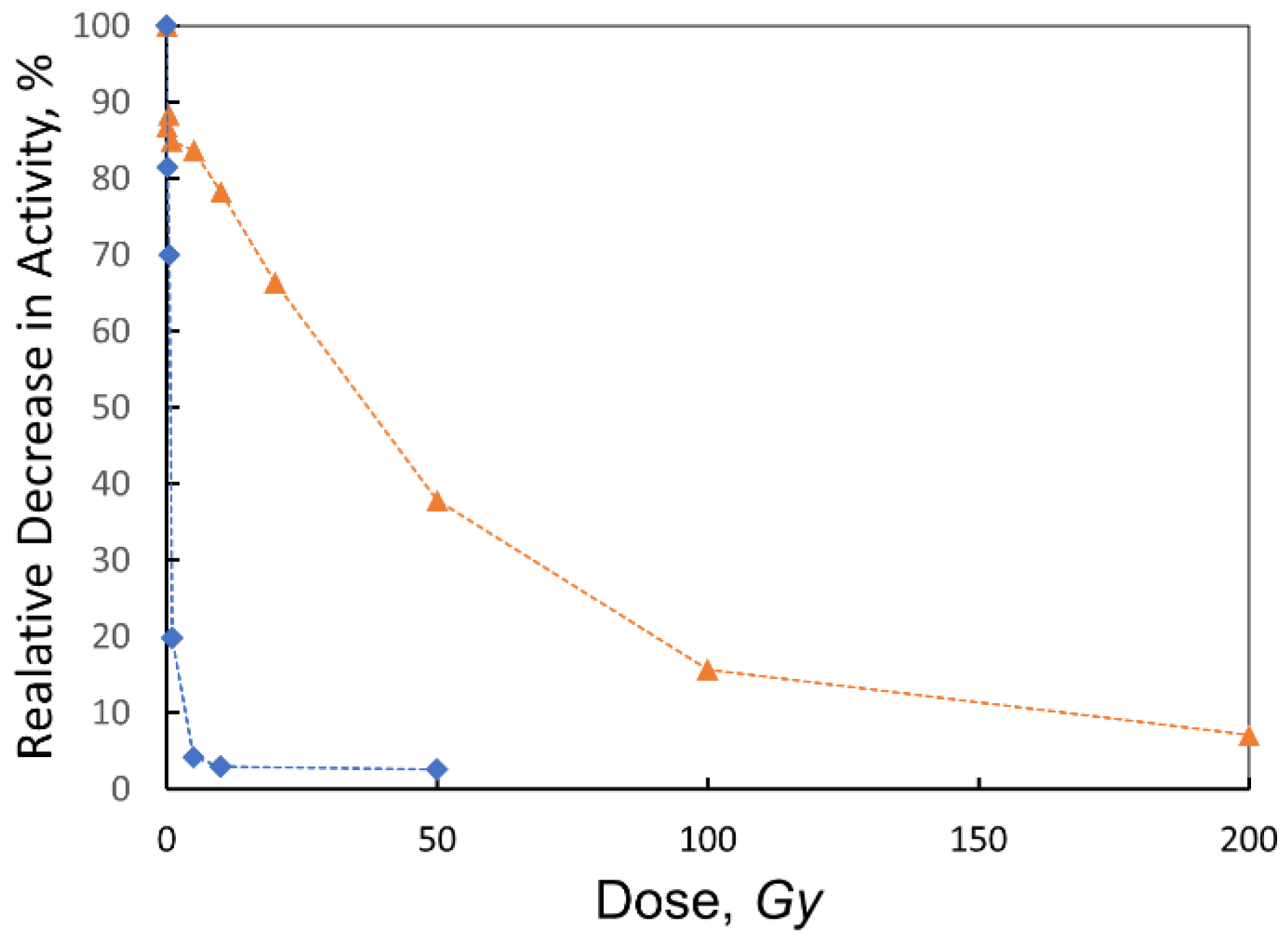

Over time, various kinetic models have been proposed to explain how enzyme activity changes with radiation dose [

10]. These models generally show that enzyme activity decreases as dilute enzyme solutions are irradiated, primarily because "deactivated" enzymes compete with active ones for water radiolysis products. Early models described a linear relationship between enzyme activity and dose, often overlooking experimental deviations. However, it was later recognized that if inactivated and active enzyme molecules interact with aqueous reagents (primarily free radicals) at comparable reaction rates, modified kinetic models predict an exponential relationship between radiation dose and enzyme deactivation [

10]. The radiolysis of sulfhydryl proteases (also known as cysteine proteases due to the presence of cysteine in their active sites) has been extensively studied [

10,

17,

33]. A key proposal is that if both active and inactivated enzymes react similarly with free radicals generated from radiolysis, the dose-response relationship follows an exponential model [

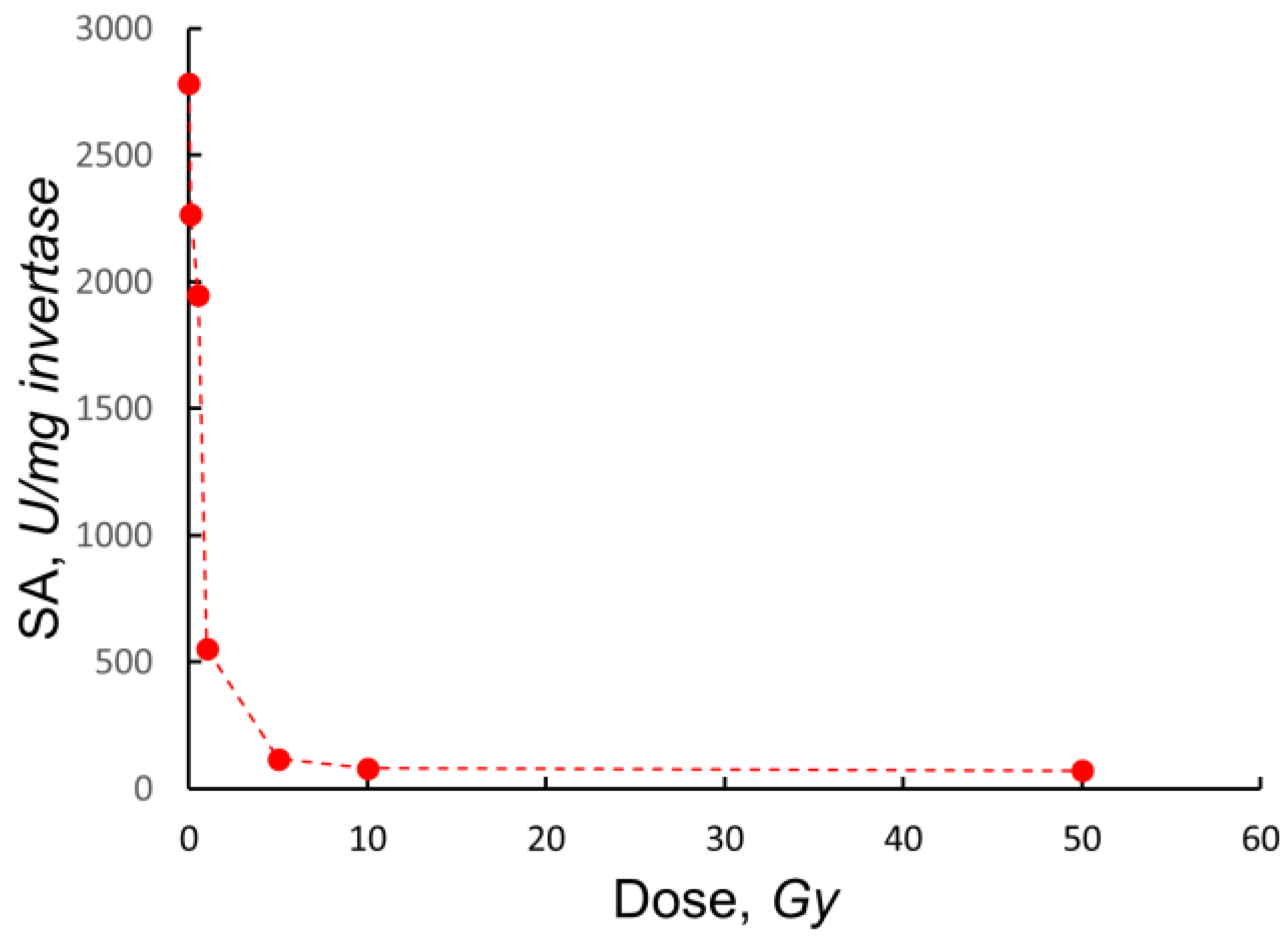

15]. This relationship is expressed as:

where

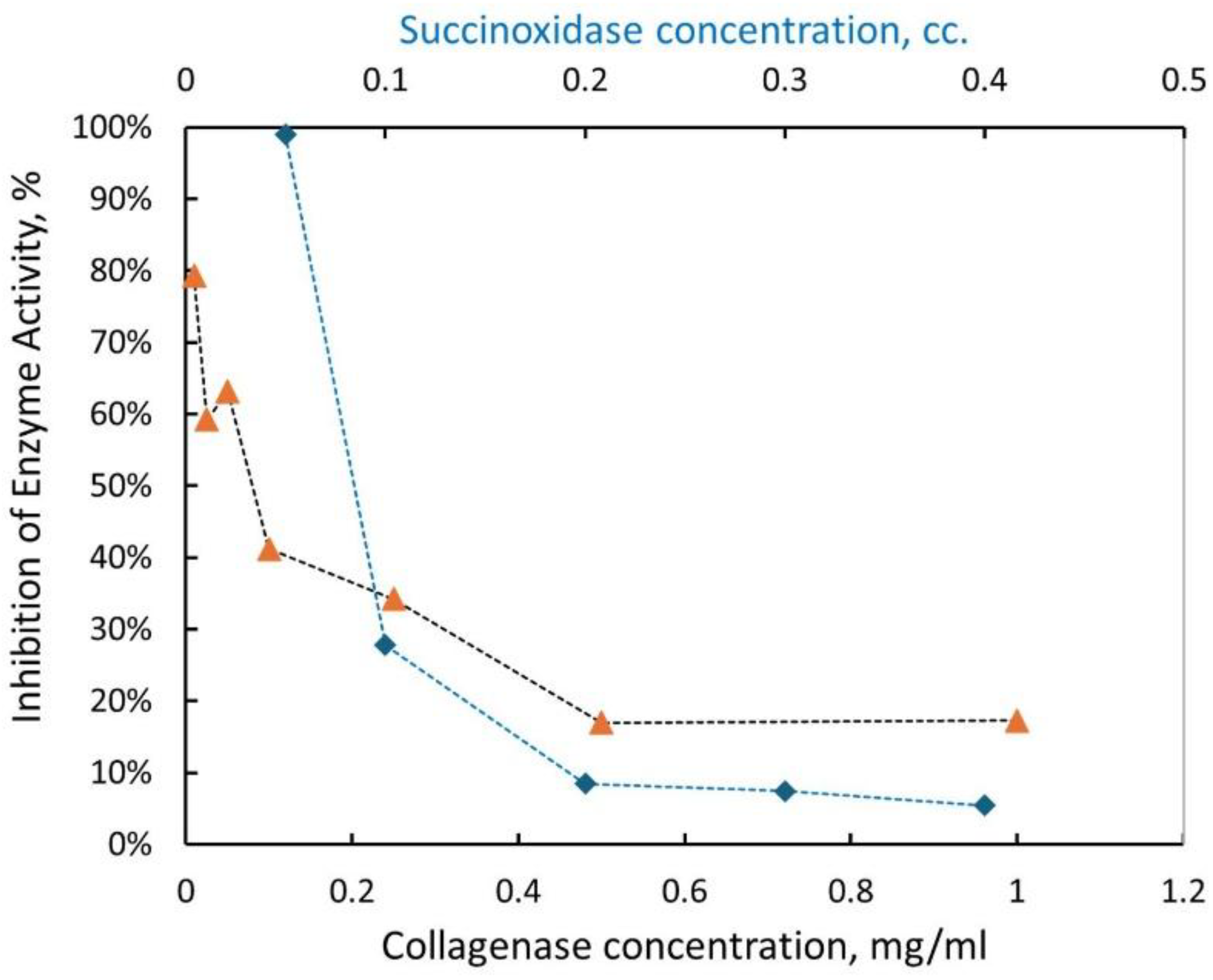

is the ratio of the amount of irradiated enzyme molecules to native (nonirradiated) enzyme molecules, which is proportional to the relative activity of irradiated enzymes compared to nonirradiated ones, K is the global kinetic constant, and D is the radiation dose. When fitting our collagenase and invertase data (

Figure 6) to this model, we obtained

and

, respectively.

The physical meaning of this empirically determined constant is not straightforward to define, but it allows calculation of the so-called

—the dose required to reduce enzyme activity to 50% of its native level. The model yields

for collagenase and

for invertase. These results indicate that invertase is more than 50 times more susceptible to radiation-induced inactivation than collagenase. This difference is striking, although the applicability of Dale’s model to collagenase should be interpreted with caution. For sulfhydryl proteases, Dale’s exponential dose–response model has been shown to describe enzyme inactivation reliably. However, collagenase is a Zn²⁺-dependent matrix metalloproteinase with a saddle-shaped tertiary structure and a zinc ion at its active site [

34]. Therefore, although we applied the same model, the kinetic meaning of the constant K for collagenase likely differs from that for sulfhydryl enzymes. For example, studies on carboxypeptidase A, another Zn-containing enzyme, have shown that inactivation primarily results from conformational changes rather than direct damage to the active site [

35]. Interestingly, while other Zn-containing enzymes such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) also follow an exponential inactivation trend, the reported K value for ACE is about an order of magnitude lower than the K value obtained for collagenase. This suggests that although Zn-containing hydrolases generally share some sensitivity to radiation-induced conformational changes, collagenase shows significantly higher sensitivity—potentially due to differences in structural stability or the dynamics of free radical interactions.

It is also noteworthy that, as reported by Orlova [

35], ACE retains about 50% of its activity even after exposure to doses as high as 800 Gy. This indicates that while metalloproteases such as collagenase share some features of their radiation response with serine and sulfhydryl proteases, significant differences remain between these enzyme classes. The mechanisms underlying these differences, particularly their varying radiation sensitivities, require further investigation. A deeper understanding could provide valuable insights into the structural and functional stability of different protease families under ionizing radiation.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully established and applied an experimental protocol leveraging a medical linear accelerator (LINAC) suite to investigate enzyme-catalyzed reactions under precisely controlled irradiation conditions. This methodology offers a significant advantage over traditional radioisotope sources by enabling real-time dose control and accurate dosimetry, crucial for understanding radiation-induced biological effects.

Applying this protocol, we evaluated the catalytic activities of two distinct enzymes: invertase and collagenase. For invertase, our findings revealed a pronounced nonlinear decrease in activity with increasing radiation dose. Native invertase activity experienced a sharp decline between 0.1 and 10 Gy, plummeting to a mere 2.2% of its initial activity at the maximum dose of 50 Gy. This inactivation followed Dale's exponential law, yielding a constant . This observed sensitivity suggests that radical species generated during radiolysis likely induce damage to critical amino acid residues, such as methionine and histidine, within the enzyme's active site or structural integrity.

In the case of collagenase, we thoroughly investigated its response to ionizing radiation across various enzyme concentrations and doses. Through both fixed-dose and variable-dose irradiation protocols, we demonstrated that collagenase activity exhibits an exponential decay with a rate constant of . This finding suggests that collagenase, a metalloprotease, shares certain fundamental radiation-response characteristics with other protease classes, notably serine and sulfhydryl proteases. However, the observed differences in radiation sensitivities among these enzyme classes underscore the necessity for further comprehensive investigation employing a wider array of experimental methods and advanced theoretical approaches to fully elucidate their distinct mechanisms of radiation-induced inactivation.

Our developed LINAC-based experimental framework provides a robust and reproducible platform for future studies exploring the radiation biology of enzymes, offering unparalleled control over irradiation parameters. This precise control is paramount for advancing our understanding of radiation-induced enzyme damage and for developing strategies to mitigate such effects in various applications, including radiotherapy and enzyme biotechnology.