Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Which categories of mangrove ecosystem services are most frequently examined in the literature, and how have these emphases shifted over time?

- Who are the key stakeholders identified or engaged in these studies, and how are their roles conceptualized?

- Are cultural ecosystem services addressed in natural science journals, or are they predominantly confined to social science literature?

- To what extent do published studies consider trade-offs among different ecosystem services, and how are these trade-offs framed?

2. Context: Mangroves and Regions of Interest

2.1. Mangroves Regulate Coastal Erosion, Storm Surge, Water Quality, and Carbon Sequestration

2.2. Mangroves Provide Supporting, Provisioning, and Cultural Services

2.3. Stakeholder Engagement Is Vital to Mangrove Futures

3. Materials and Methods

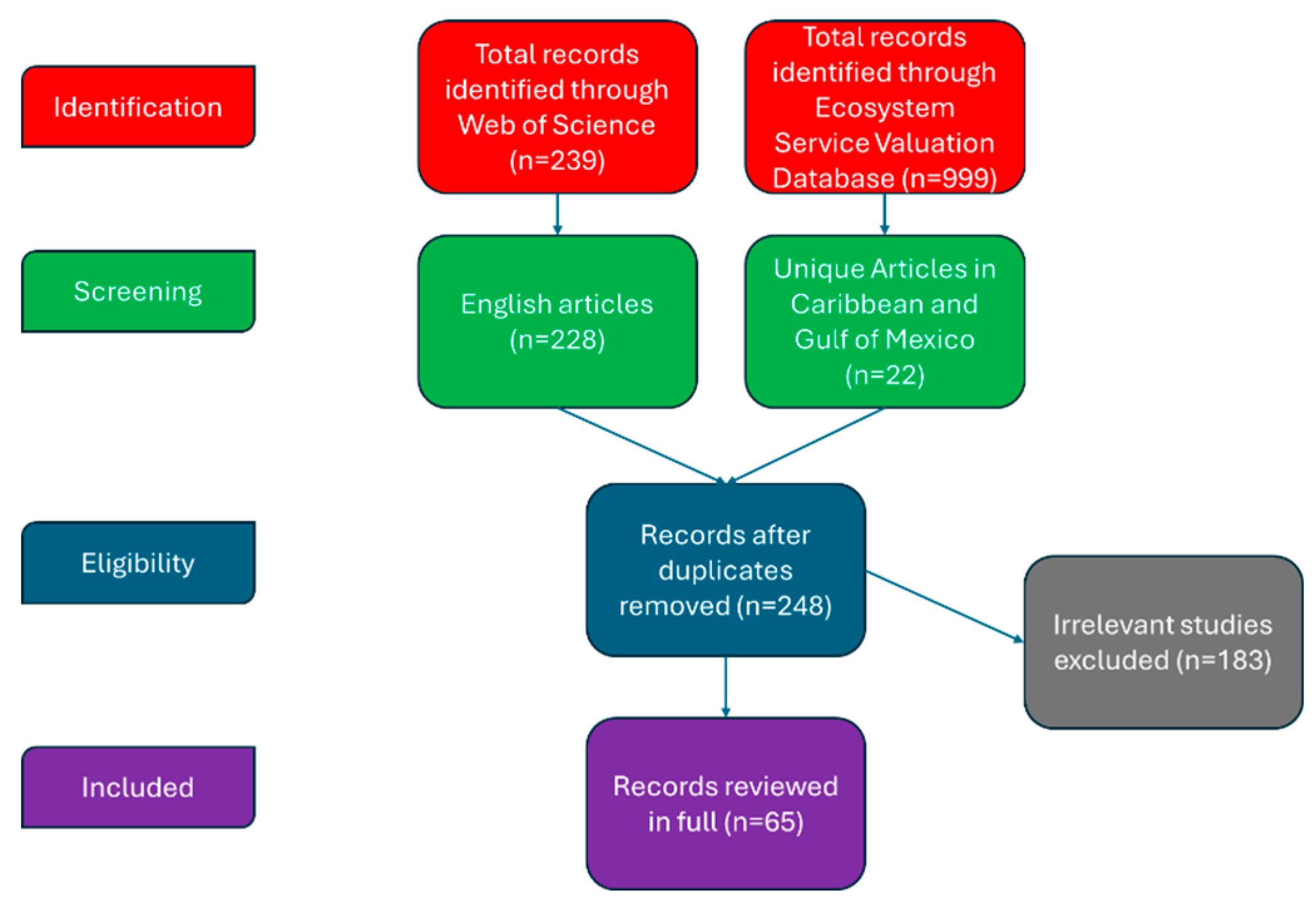

3.1. Study Framework and Data Sources

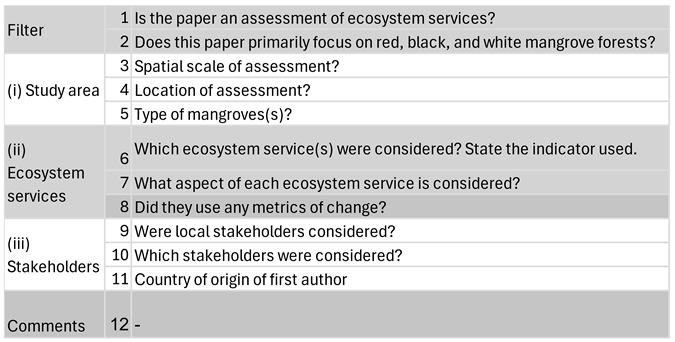

3.2. Data Filtering

- The geographic location of the research;

- The category or categories of ecosystem services analyzed;

- Whether multiple ecosystem services were examined in convergence or trade-off;

- The extent and nature of stakeholder engagement.

3.3. Comparative Bibliometric Methodology

3.3.1. VOSviewer

3.3.2. Bibliometrix

3.4. Optimized-Hotspot Analysis

4. Results

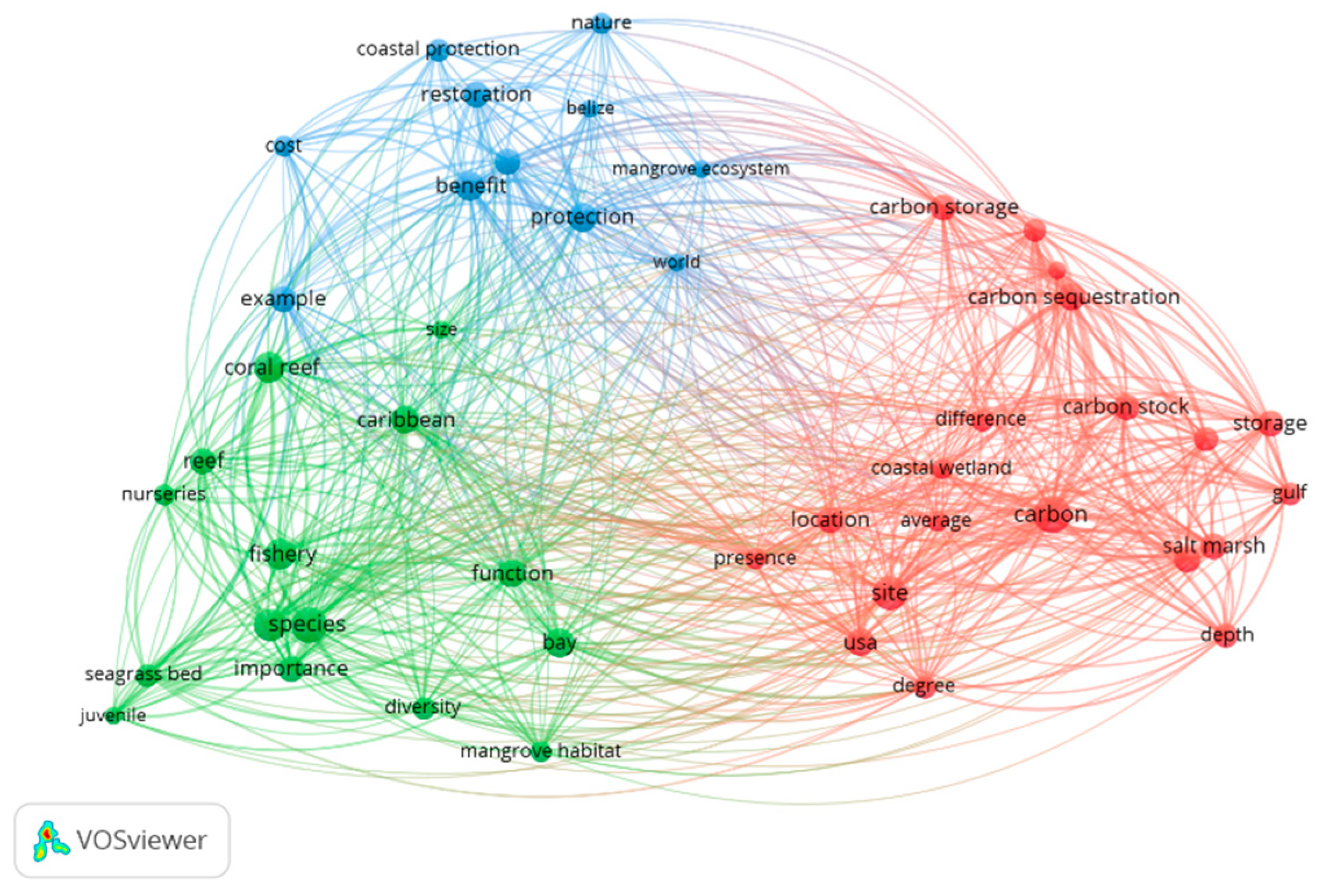

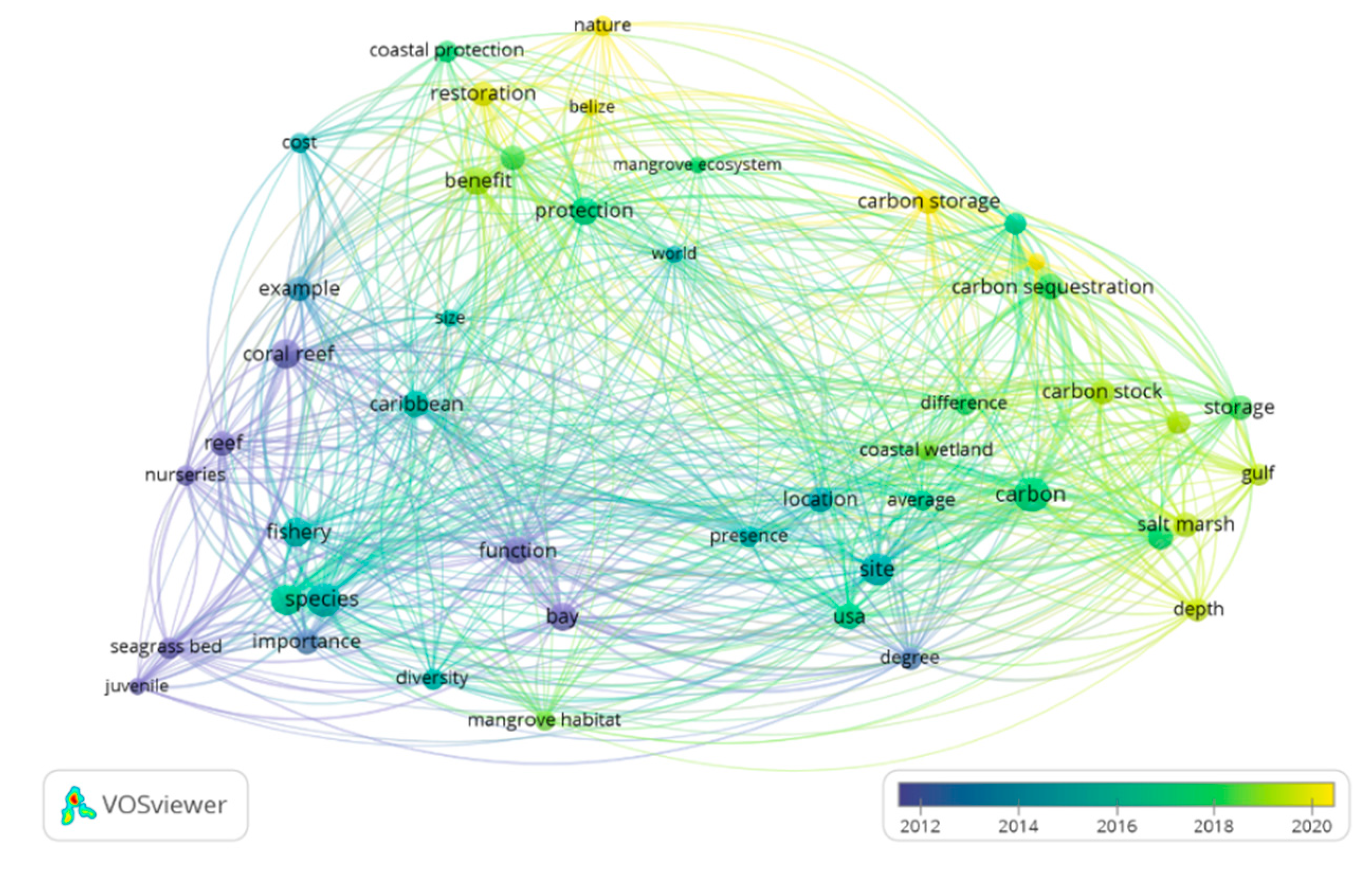

4.1. Cluster Analysis

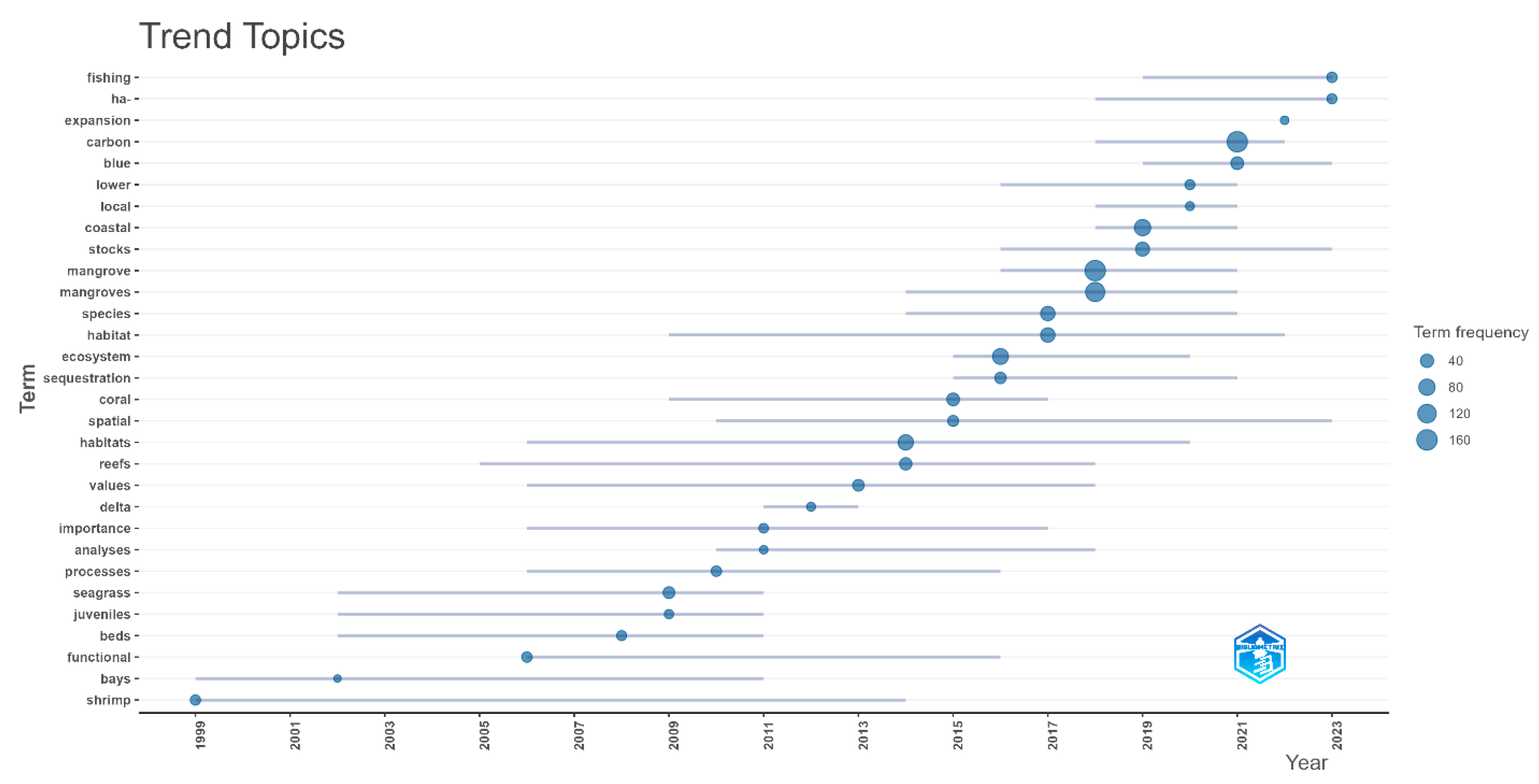

4.2. Analysis of Trend Topics

- Foundational Topics and Long-Term Focus: Core ecological and habitat-related terms such as “fishing,” “mangroves,” “habitat,” and “ecosystem” appear consistently across the entire time span, indicating a persistent foundational interest in these themes within marine and coastal research. These topics reflect long-standing concerns with biodiversity, habitat provisioning, and the ecological functions of mangrove systems.

- Emergence of Climate and Carbon-Centric Themes: Terms such as “carbon,” “sequestration,” and “blue” (as in “blue carbon”) show a marked rise in frequency in recent years, particularly from 2016 onward. This corresponds with the growing global recognition of nature-based solutions and the role of coastal ecosystems in carbon storage and climate mitigation. Their increased presence in the literature aligns with policy shifts (e.g., IPCC reports, NDC frameworks) that have prioritized ecosystem-based climate strategies.

- Expansion of Ecosystem Valuation and Sustainability Discourse: The appearance and growth of terms like “values,” “importance,” “functional,” and “stocks” reflect a conceptual shift toward ecosystem service valuation. These trends suggest that more recent research is not only concerned with ecological processes, but also with how those processes translate into measurable benefits—economically, socially, and climatologically. This mirrors the rising influence of valuation frameworks such as TEEB and CICES in environmental policy and finance.

- Sustained Focus on Interconnected Ecosystems: Terms such as “seagrass,” “coral,” and “species” exhibit continuous and growing presence, underscoring an enduring focus on ecosystem connectivity and the biodiversity-supporting roles of mangroves. These ecosystems are increasingly viewed as part of integrated coastal-marine systems, with linkages to adjacent habitats and mutual reinforcement of ecological functions (e.g., fish nurseries, shoreline stabilization).

4.3. Analysis of Country Collaboration

4.4. Factorial Analysis

4.5. Optimized-Hotspot Analysis

4.6. Analysis of Ecosystem Services

4.7. Analysis of Stakeholders

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESVD | Ecosystem Services Valuation Database |

| CICES | Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services |

| TEEB | Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity |

| MCA | Multiple Correspondence Analysis |

| OHS | Optimized Hotspot Analys |

References

- Kathiresan, K.; Bingham, B.L. Biology of Mangroves and Mangrove Ecosystems. In Advances in Marine Biology; Academic Press, 2001; Vol. 40, pp. 81–251.

- Rützler, K.; Feller, I.C. Mangrove Swamp Communities: An Approach in Belize. 1999.

- Branoff, B.L. Quantifying the Influence of Urban Land Use on Mangrove Biology and Ecology: A Meta-Analysis. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2017, 26, 1339–1356. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A.M.; Farnsworth, E.J. Anthropogenic Disturbance of Caribbean Mangrove Ecosystems: Past Impacts, Present Trends, and Future Predictions. Biotropica 1996, 28, 549. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.S.; Kenworthy, W.J.; Wood, L.L. Ontogenetic Patterns of Concentration Indicate Lagoon Nurseries Are Essential to Common Grunts Stocks in a Puerto Rican Bay. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2009, 81, 533–543. [CrossRef]

- Fry, B.; Mumford, P.L.; Robblee, M.B. Stable Isotope Studies of Pink Shrimp (Farfantepenaeus Duorarum Burkenroad) Migrations on the Southwestern Florida Shelf. Bulletin of Marine Science 1999, 65, 419–430.

- Nagelkerken, I.; Roberts, C.M.; Velde, G. van der; Dorenbosch, M.; Riel, M.C. van; Morinière, E.C. de la; Nienhuis, P.H. How Important Are Mangroves and Seagrass Beds for Coral-Reef Fish? The Nursery Hypothesis Tested on an Island Scale. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2002, 244, 299–305. [CrossRef]

- Bhomia, R.K.; Kauffman, J.B.; McFadden, T.N. Ecosystem Carbon Stocks of Mangrove Forests along the Pacific and Caribbean Coasts of Honduras. Wetlands Ecol Manage 2016, 24, 187–201. [CrossRef]

- Breithaupt, J.L.; Smoak, J.M.; Smith III, T.J.; Sanders, C.J. Temporal Variability of Carbon and Nutrient Burial, Sediment Accretion, and Mass Accumulation over the Past Century in a Carbonate Platform Mangrove Forest of the Florida Everglades. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2014, 119, 2032–2048. [CrossRef]

- Imbert, D. Hurricane Disturbance and Forest Dynamics in East Caribbean Mangroves. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02231. [CrossRef]

- Radabaugh, K.R.; Moyer, R.P.; Chappel, A.R.; Powell, C.E.; Bociu, I.; Clark, B.C.; Smoak, J.M. Coastal Blue Carbon Assessment of Mangroves, Salt Marshes, and Salt Barrens in Tampa Bay, Florida, USA. Estuaries and Coasts 2018, 41, 1496–1510. [CrossRef]

- Zagonari, F. Using Ecosystem Services in Decision-Making to Support Sustainable Development: Critiques, Model Development, a Case Study, and Perspectives. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 548–549, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Gunton, R.M.; Asperen, E.N. van; Basden, A.; Bookless, D.; Araya, Y.; Hanson, D.R.; Goddard, M.A.; Otieno, G.; Jones, G.O. Beyond Ecosystem Services: Valuing the Invaluable. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2017, 32, 249–257. [CrossRef]

- Schröter, M.; van der Zanden, E.H.; van Oudenhoven, A.P.E.; Remme, R.P.; Serna-Chavez, H.M.; de Groot, R.S.; Opdam, P. Ecosystem Services as a Contested Concept: A Synthesis of Critique and Counter-Arguments. Conservation Letters 2014, 7, 514–523. [CrossRef]

- Wegner, G.; Pascual, U. Cost-Benefit Analysis in the Context of Ecosystem Services for Human Well-Being: A Multidisciplinary Critique. Global Environmental Change 2011, 21, 492–504. [CrossRef]

- Craig, M.P.A.; Stevenson, H.; Meadowcroft, J. Debating Nature’s Value: Epistemic Strategy and Struggle in the Story of ‘Ecosystem Services.’ Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2019, 21, 811–825. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Economic Valuation and the Commodification of Ecosystem Services. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment 2011, 35, 613–628. [CrossRef]

- Badura, T.; Kettunen, M. Regulating Services and Related Goods. In Social and Economic Benefits of Protected Areas; Routledge, 2013 ISBN 978-0-203-09534-8.

- Alemu I, J.B.; Richards, D.R.; Gaw, L.Y.-F.; Masoudi, M.; Nathan, Y.; Friess, D.A. Identifying Spatial Patterns and Interactions among Multiple Ecosystem Services in an Urban Mangrove Landscape. Ecological Indicators 2021, 121, 107042. [CrossRef]

- Hayden, H.L.; Granek, E.F. Coastal Sediment Elevation Change Following Anthropogenic Mangrove Clearing. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2015, 165, 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Mazda, Y.; Magi, M.; Nanao, H.; Kogo, M.; Miyagi, T.; Kanazawa, N.; Kobashi, D. Coastal Erosion Due to Long-Term Human Impact on Mangrove Forests. Wetlands Ecology and Management 2002, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.L.; Vervaeke, W.C. Impacts of Human Disturbance on Soil Erosion Potential and Habitat Stability of Mangrove-Dominated Islands in the Pelican Cays and Twin Cays Ranges, Belize.

- Rangel-Buitrago, N.G.; Anfuso, G.; Williams, A.T. Coastal Erosion along the Caribbean Coast of Colombia: Magnitudes, Causes and Management. Ocean & Coastal Management 2015, 114, 129–144. [CrossRef]

- Villate Daza, D.A.; Sánchez Moreno, H.; Portz, L.; Portantiolo Manzolli, R.; Bolívar-Anillo, H.J.; Anfuso, G. Mangrove Forests Evolution and Threats in the Caribbean Sea of Colombia. Water 2020, 12, 1113. [CrossRef]

- Bryan-Brown, D.N.; Connolly, R.M.; Richards, D.R.; Adame, F.; Friess, D.A.; Brown, C.J. Global Trends in Mangrove Forest Fragmentation. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 7117. [CrossRef]

- Flowers, B.; Huang, K.-T.; Aldana, G.O. Analysis of the Habitat Fragmentation of Ecosystems in Belize Using Landscape Metrics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3024. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; van Oort, B.; Romstad, B. What We Have Lost and Cannot Become: Societal Outcomes of Coastal Erosion in Southern Belize. Ecology and Society 2015, 20. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Xu, H.; Shen, J.; Rhome, J.; Smith, T.J. The Role of Mangroves in Attenuating Storm Surges. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2012, 102–103, 11–23. [CrossRef]

- Blankespoor, B.; Dasgupta, S.; Lange, G.-M. Mangroves as a Protection from Storm Surges in a Changing Climate. Ambio 2017, 46, 478–491. [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.M.; Bryan, K.R.; Mullarney, J.C.; Horstman, E.M. Attenuation of Storm Surges by Coastal Mangroves. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46, 2680–2689. [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.A.; Wilson Grimes, K.; Reeve, A.S.; Platenberg, R. Mangroves Buffer Marine Protected Area from Impacts of Bovoni Landfill, St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands. Wetlands Ecol Manage 2017, 25, 563–582. [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Castillo-Olaya, V.A.; Granados-Briceño, A.F.; Blandón García, L.M.; Espinosa Díaz, L.F. Marine Litter and Microplastic Pollution on Mangrove Soils of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Colombian Caribbean. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2019, 145, 455–462. [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ordóñez, O.; Saldarriaga-Vélez, J.F.; Espinosa-Díaz, L.F. Marine Litter Pollution in Mangrove Forests from Providencia and Santa Catalina Islands, after Hurricane IOTA Path in the Colombian Caribbean. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 168, 112471. [CrossRef]

- Seeruttun, L.D.; Raghbor, P.; Appadoo, C. First Assessment of Anthropogenic Marine Debris in Mangrove Forests of Mauritius, a Small Oceanic Island. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 164, 112019. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.Y.; Not, C.; Cannicci, S. Mangroves as Unique but Understudied Traps for Anthropogenic Marine Debris: A Review of Present Information and the Way Forward. Environmental Pollution 2021, 271, 116291. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.W.; Doyle, T.W.; Twilley, R.R.; Smith III, T.J.; Whelan, K.R.T.; Sullivan, J.K. Woody Debris in the Mangrove Forests of South Florida1. Biotropica 2005, 37, 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Cubit, J.D.; Getter, C.D.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Garrity, S.D.; Caffey, H.M.; Thompson, R.C.; Weil, E.; Marshall, M.J. AN OIL SPILL AFFECTING CORAL REEFS AND MANGROVES ON THE CARIBBEAN COAST OF PANAMA. International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings 1987, 1987, 401–406. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Asmath, H.; Chee, C.L.; Darsan, J. Potential Oil Spill Risk from Shipping and the Implications for Management in the Caribbean Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2015, 93, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Rubí, J.R.; Luna-Acosta, A.; Etxebarría, N.; Soto, M.; Espinoza, F.; Ahrens, M.J.; Marigómez, I. Chemical Contamination Assessment in Mangrove-Lined Caribbean Coastal Systems Using the Oyster Crassostrea Rhizophorae as Biomonitor Species. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2018, 25, 13396–13415. [CrossRef]

- Taillardat, P.; Friess, D.A.; Lupascu, M. Mangrove Blue Carbon Strategies for Climate Change Mitigation Are Most Effective at the National Scale. Biology Letters 2018, 14, 20180251. [CrossRef]

- Alongi, D.M. Global Significance of Mangrove Blue Carbon in Climate Change Mitigation. Sci 2020, 2, 67. [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Anton, A.; Raven, J.A.; Beaumont, N.; Connolly, R.M.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Kuwae, T.; Lavery, P.S.; et al. The Future of Blue Carbon Science. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3998. [CrossRef]

- Macreadie, P.I.; Costa, M.D.P.; Atwood, T.B.; Friess, D.A.; Kelleway, J.J.; Kennedy, H.; Lovelock, C.E.; Serrano, O.; Duarte, C.M. Blue Carbon as a Natural Climate Solution. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2021, 2, 826–839. [CrossRef]

- Morrissette, H.K.; Baez, S.K.; Beers, L.; Bood, N.; Martinez, N.D.; Novelo, K.; Andrews, G.; Balan, L.; Beers, C.S.; Betancourt, S.A.; et al. Belize Blue Carbon: Establishing a National Carbon Stock Estimate for Mangrove Ecosystems. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 870, 161829. [CrossRef]

- Sidik, F.; Lawrence, A.; Wagey, T.; Zamzani, F.; Lovelock, C.E. Blue Carbon: A New Paradigm of Mangrove Conservation and Management in Indonesia. Marine Policy 2023, 147, 105388. [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Silveira, J.A.; Pech-Cardenas, M.A.; Morales-Ojeda, S.M.; Cinco-Castro, S.; Camacho-Rico, A.; Sosa, J.P.C.; Mendoza-Martinez, J.E.; Pech-Poot, E.Y.; Montero, J.; Teutli-Hernandez, C. Blue Carbon of Mexico, Carbon Stocks and Fluxes: A Systematic Review. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8790. [CrossRef]

- Sedjo, R.; Sohngen, B. Carbon Sequestration in Forests and Soils. Annual Review of Resource Economics 2012, 4, 127–144. [CrossRef]

- Krauss, K.W.; Lovelock, C.E.; McKee, K.L.; López-Hoffman, L.; Ewe, S.M.L.; Sousa, W.P. Environmental Drivers in Mangrove Establishment and Early Development: A Review. Aquatic Botany 2008, 89, 105–127. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, J.C. Factors Influencing Mangrove Ecosystems. In Mangroves: Ecology, Biodiversity and Management; Rastogi, R.P., Phulwaria, M., Gupta, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 97–115 ISBN 978-981-16-2494-0.

- Reef, R.; Feller, I.C.; Lovelock, C.E. Nutrition of Mangroves. Tree Physiology 2010, 30, 1148–1160. [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J.; Edwards, A.J.; Ernesto Arias-González, J.; Lindeman, K.C.; Blackwell, P.G.; Gall, A.; Gorczynska, M.I.; Harborne, A.R.; Pescod, C.L.; Renken, H.; et al. Mangroves Enhance the Biomass of Coral Reef Fish Communities in the Caribbean. Nature 2004, 427, 533–536. [CrossRef]

- Miloslavich, P.; Díaz, J.M.; Klein, E.; Alvarado, J.J.; Díaz, C.; Gobin, J.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Cruz-Motta, J.J.; Weil, E.; Cortés, J.; et al. Marine Biodiversity in the Caribbean: Regional Estimates and Distribution Patterns. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e11916. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.P.; Ranjan, R.; Singh, J.S. Human–Mangrove Conflicts: The Way Out. Current Science 2002, 83, 1328–1336.

- Twilley, R.R.; Snedaker, S.C. 13 Biodiversity and Ecosystem.

- Lee, S.Y.; Primavera, J.H.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; McKee, K.; Bosire, J.O.; Cannicci, S.; Diele, K.; Fromard, F.; Koedam, N.; Marchand, C.; et al. Ecological Role and Services of Tropical Mangrove Ecosystems: A Reassessment. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2014, 23, 726–743. [CrossRef]

- Henry, L.-A. A Deep-Sea Coral “Gateway” in the Northwestern Caribbean. In Too previous to drill: the marine biodiversity of Belize; 2011; pp. 120–124.

- Gómez-Montes, C.; Bayly, N.J. Habitat Use, Abundance, and Persistence of Neotropical Migrant Birds in a Habitat Matrix in Northeast Belize. Journal of Field Ornithology 2010, 81, 237–251. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, L.T.; Canty, S.W.J.; Cissell, J.R.; Steinberg, M.K.; Cherry, J.A.; Feller, I.C. Bird Rookery Nutrient Over-Enrichment as a Potential Accelerant of Mangrove Cay Decline in Belize. Oecologia 2021, 197, 771–784. [CrossRef]

- Rooker, J.R.; Dennis, G.D. Diel, Lunar and Seasonal Changes in a Mangrove Fish Assemblage off Southwestern Puerto Rico. Bulletin of Marine Science 1991, 49, 684–698.

- Ley, J.A.; McIvor, C.C.; Montague, C.L. Fishes in Mangrove Prop-Root Habitats of Northeastern Florida Bay: Distinct Assemblages across an Estuarine Gradient. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 1999, 48, 701–723. [CrossRef]

- Igulu, M.M.; Nagelkerken, I.; Dorenbosch, M.; Grol, M.G.G.; Harborne, A.R.; Kimirei, I.A.; Mumby, P.J.; Olds, A.D.; Mgaya, Y.D. Mangrove Habitat Use by Juvenile Reef Fish: Meta-Analysis Reveals That Tidal Regime Matters More than Biogeographic Region. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e114715. [CrossRef]

- Nagelkerken, I.; Kleijnen, S.; Klop, T.; Brand, R.A.C.J. van den; Morinière, E.C. de la; Velde, G. van der Dependence of Caribbean Reef Fishes on Mangroves and Seagrass Beds as Nursery Habitats: A Comparison of Fish Faunas between Bays with and without Mangroves/Seagrass Beds. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2001, 214, 225–235. [CrossRef]

- Kibria, A.S.M.G.; Costanza, R.; Groves, C.; Behie, A.M. The Interactions between Livelihood Capitals and Access of Local Communities to the Forest Provisioning Services of the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest, Bangladesh. Ecosystem Services 2018, 32, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, Md.S.; de Ruyter van Steveninck, E.; Stuip, M.; Shah, M.A.R. Economic Valuation of Provisioning and Cultural Services of a Protected Mangrove Ecosystem: A Case Study on Sundarbans Reserve Forest, Bangladesh. Ecosystem Services 2013, 5, 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Osland, M.J.; Hughes, A.R.; Armitage, A.R.; Scyphers, S.B.; Cebrian, J.; Swinea, S.H.; Shepard, C.C.; Allen, M.S.; Feher, L.C.; Nelson, J.A.; et al. The Impacts of Mangrove Range Expansion on Wetland Ecosystem Services in the Southeastern United States: Current Understanding, Knowledge Gaps, and Emerging Research Needs. Global Change Biology 2022, 28, 3163–3187. [CrossRef]

- Failler, P.; Pètre, É.; Binet, T.; Maréchal, J.-P. Valuation of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services as a Tool for Conservation: The Case of Martinique in the Caribbean. Ecosystem Services 2015, 11, 67–75. [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla-Henao, M.; Ban, N.; Rueda, M.; Juanes, F. The Mangrove-Fishery Relationship: A Local Ecological Knowledge Perspective. Marine Policy 2019, 108, 103656. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval Londoño, L.A.; Leal-Flórez, J.; Blanco-Libreros, J.F. Linking Mangroves and Fish Catch: A Correlational Study in the Southern Caribbean Sea (Colombia). Bulletin of Marine Science 2020, 96, 415–430. [CrossRef]

- Arkema, K.K.; Delevaux, J.M.S.; Silver, J.M.; Winder, S.G.; Schile-Beers, L.M.; Bood, N.; Crooks, S.; Douthwaite, K.; Durham, C.; Hawthorne, P.L.; et al. Evidence-Based Target Setting Informs Blue Carbon Strategies for Nationally Determined Contributions. Nat Ecol Evol 2023, 7, 1045–1059. [CrossRef]

- Bacon, P.R.; Alleng, G.P. The Management of Insular Caribbean Mangroves in Relation to Site Location and Community Type. In Proceedings of the The Ecology of Mangrove and Related Ecosystems; Jaccarini, V., Martens, E., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1992; pp. 235–241.

- Rogers, C.S. A Unique Coral Community in the Mangroves of Hurricane Hole, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Diversity 2017, 9, 29. [CrossRef]

- Furman, K.L.; Harlan, S.L.; Barbieri, L.; Scyphers, S.B. Social Equity in Shore-Based Fisheries: Identifying and Understanding Barriers to Access. Marine Policy 2023, 148, 105355. [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.; Parrett, C.L. Global Patterns in Mangrove Recreation and Tourism. Marine Policy 2019, 110, 103540. [CrossRef]

- Avau, J.; Cunha-Lignon, M.; De Myttenaere, B.; Godart, M.-F.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. The Commercial Images Promoting Caribbean Mangroves to Tourists: Case Studies in Jamaica, Guadeloupe and Martinique. Journal of Coastal Research 2011, 1277–1281.

- Brenner, L.; Engelbauer, M.; Job, H. Mitigating Tourism-Driven Impacts on Mangroves in Cancún and the Riviera Maya, Mexico: An Evaluation of Conservation Policy Strategies and Environmental Planning Instruments. J Coast Conserv 2018, 22, 755–767. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-del-Río, D.; Brenner, L. Mangroves in Transition. Management of Community Spaces Affected by Conservation and Tourism in Mexico. Ocean & Coastal Management 2023, 232, 106439. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, A.A.; Harris-Wai, J.N. Stakeholder Engagement in Policy Development: Challenges and Opportunities for Human Genomics. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 949–957. [CrossRef]

- Carriger, J.F.; Jordan, S.J.; Kurtz, J.C.; Benson, W.H. Identifying Evaluation Considerations for the Recovery and Restoration from the 2010 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill: An Initial Appraisal of Stakeholder Concerns and Values. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 2015, 11, 502–513. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Ramachandran, A.; Usha, N.; Aram, I.A.; Selvam, V. Rising Sea and Threatened Mangroves: A Case Study on Stakeholders, Engagement in Climate Change Communication and Non-Formal Education. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 2012, 19, 330–338. [CrossRef]

- Lester, J.-A.; Weeden, C. Stakeholders, the Natural Environment and the Future of Caribbean Cruise Tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research 2004, 6, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Saint Ville, A.S.; Hickey, G.M.; Phillip, L.E. How Do Stakeholder Interactions Influence National Food Security Policy in the Caribbean? The Case of Saint Lucia. Food Policy 2017, 68, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Yoskowitz, D.W.; Werner, S.R.; Carollo, C.; Santos, C.; Washburn, T.; Isaksen, G.H. Gulf of Mexico Offshore Ecosystem Services: Relative Valuation by Stakeholders. Marine Policy 2016, 66, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.; Moulaert, I.; Asselman, J.; van der Biest, K.; van de Pol, L.; Drouillon, M.; Hernandez Lucas, S.; Taelman, S.E.; Everaert, G. Prioritizing Ecosystem Services for Marine Management through Stakeholder Engagement. Ocean & Coastal Management 2022, 225, 106228. [CrossRef]

- Solomonsz, J.; Melbourne-Thomas, J.; Constable, A.; Trebilco, R.; van Putten, I.; Goldsworthy, L. Stakeholder Engagement in Decision Making and Pathways of Influence for Southern Ocean Ecosystem Services. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Vande Velde, K.; Hugé, J.; Friess, D.A.; Koedam, N.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. Stakeholder Discourses on Urban Mangrove Conservation and Management. Ocean & Coastal Management 2019, 178, 104810. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Managing Ethically with Global Stakeholders: A Present and Future Challenge. AMP 2004, 18, 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Devinney, T.M.; Mcgahan, A.M.; Zollo, M. A Research Agenda for Global Stakeholder Strategy. Global Strategy Journal 2013, 3, 325–337. [CrossRef]

- Pullin, A.S.; Knight, T.M. Doing More Good than Harm – Building an Evidence-Base for Conservation and Environmental Management. Biological Conservation 2009, 142, 931–934. [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.M.; Sandbrook, C. Conservation, Evidence and Policy. Oryx 2013, 47, 329–335. [CrossRef]

- An Evidence Assessment Tool for Ecosystem Services and Conservation Studies - Mupepele - 2016 - Ecological Applications - Wiley Online Library Available online: https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1890/15-0595?casa_token=w41B9aRnBwAAAAAA%3AZSW2IJXfvCi8z0Ky1RZ41HvtNc8pGKwjepRQgQjsnL9jD2ZPQTm0Xg1jmFBcUmhNxgM4Jlx7-CeY3Q (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Brander, L.M.; de Groot, R.; Guisado Goni, V.; van ’t Hoff, V.; Schagner, P.; Solomonides, S.; McVittie, A.; Eppink, F.; Sposato, M.; Do, L.; et al. Ecosystem Services Valuation Database (ESVD). Foundation for Sustainable Development and Brander Environmental Economics. 2024.

- Brouwer, R.; Brander, L.; Kuik, O.; Papyrakis, E.; Bateman, I. A Synthesis of Approaches to Assess and Value Ecosystem Services in the EU in the Context of TEEB.

- Czúcz, B.; Arany, I.; Potschin-Young, M.; Bereczki, K.; Kertész, M.; Kiss, M.; Aszalós, R.; Haines-Young, R. Where Concepts Meet the Real World: A Systematic Review of Ecosystem Service Indicators and Their Classification Using CICES. Ecosystem Services 2018, 29, 145–157. [CrossRef]

- Ring, I.; Hansjürgens, B.; Elmqvist, T.; Wittmer, H.; Sukhdev, P. Challenges in Framing the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: The TEEB Initiative. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2010, 2, 15–26. [CrossRef]

- Maes, J.; Teller, A.; Erhard, M.; Liquete, C.; Braat, L.; Berry, P.; Egoh, B.N.; Puydarrieux, P.; Fiorina, C.; Santos-Martín, F.; et al. Mapping and Assessment of Ecosystems and Their Services – An Analytical Framework for Ecosystem Assessments under Action 5 of the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020. Discussion Paper Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC81328 (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual.

- Arkema, K.K.; Verutes, G.M.; Wood, S.A.; Clarke-Samuels, C.; Rosado, S.; Canto, M.; Rosenthal, A.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Guannel, G.; Toft, J.; et al. Embedding Ecosystem Services in Coastal Planning Leads to Better Outcomes for People and Nature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 7390–7395. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, A.R.; Weaver, C.A.; Whitt, A.A.; Pennings, S.C. Effects of Mangrove Encroachment on Tidal Wetland Plant, Nekton, and Bird Communities in the Western Gulf of Mexico. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2021, 248, 106767. [CrossRef]

- Canty, S.W.J.; Preziosi, R.F.; Rowntree, J.K. Dichotomy of Mangrove Management: A Review of Research and Policy in the Mesoamerican Reef Region. Ocean & Coastal Management 2018, 157, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Cruz Portorreal, Y.; Reyes Dominguez, O.J.; Milanes, C.B.; Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Cuker, B.; Pérez Montero, O. Environmental Policy and Regulatory Framework for Managing Mangroves as a Carbon Sink in Cuba. Water 2022, 14, 3903. [CrossRef]

- Duijndam, S.; van Beukering, P.; Fralikhina, H.; Molenaar, A.; Koetse, M. Valuing a Caribbean Coastal Lagoon Using the Choice Experiment Method: The Case of the Simpson Bay Lagoon, Saint Martin. Journal for Nature Conservation 2020, 56, 125845. [CrossRef]

- Fedler, T. THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF TURNEFFE ATOLL.

- Micheletti, T.; Jost, F.; Berger, U. Partitioning Stakeholders for the Economic Valuation of Ecosystem Services: Examples of a Mangrove System. Nat Resour Res 2016, 25, 331–345. [CrossRef]

- Schuhmann, P.W.; Bangwayo-Skeete, P.; Skeete, R.; Seaman, A.N.; Barnes, D.C. Visitors’ Willingness to Pay for Ecosystem Conservation in Grenada. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2024, 32, 1644–1668. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.A.; Thomas, S.; Dargusch, P.; Phinn, S. Assessing the Potential of REDD+ in a Production Mangrove Forest in Malaysia Using Stakeholder Analysis and Ecosystem Services Mapping. Marine Policy 2016, 74, 6–17. [CrossRef]

- Powell, N.; Osbeck, M. Approaches for Understanding and Embedding Stakeholder Realities in Mangrove Rehabilitation Processes in Southeast Asia: Lessons Learnt from Mahakam Delta, East Kalimantan. Sustainable Development 2010, 18, 260–270. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.S.; Friess, D.A. Stakeholder Preferences for Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) versus Other Environmental Management Approaches for Mangrove Forests. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 233, 636–648. [CrossRef]

- Poulter, B.; Adams-Metayer, F.M.; Amaral, C.; Barenblitt, A.; Campbell, A.; Charles, S.P.; Roman-Cuesta, R.M.; D’Ascanio, R.; Delaria, E.R.; Doughty, C.; et al. Multi-Scale Observations of Mangrove Blue Carbon Ecosystem Fluxes: The NASA Carbon Monitoring System BlueFlux Field Campaign. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 075009. [CrossRef]

- Soanes, L.M.; Pike, S.; Armstrong, S.; Creque, K.; Norris-Gumbs, R.; Zaluski, S.; Medcalf, K. Reducing the Vulnerability of Coastal Communities in the Caribbean through Sustainable Mangrove Management. Ocean & Coastal Management 2021, 210, 105702. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).