Introduction

Mesothelioma is a deadly disease with a poor prognosis [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. It is mainly caused by asbestos exposure, and in some cases, exposure to the SV40 virus [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. In the United States, about 3000 mesothelioma patients die each year [

13,

14]. Malignant mesothelioma is an invasive cancer that predominantly arises from the mesothelial linings of the peritoneum, pleura, and pericardium. Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is the most common form of the disease, which accounts for about 70% of the cases [

4,

6,

15,

16,

17]. MPM is an aggressive disease that is associated with poor prognosis, late detection, metastasis, and resistance to therapy [

4,

6,

9,

18]. MPM is a disease of aging, as it primarily affects the elderly population [

14]. Although a limited success has been made with the combination of pemetrexed and cisplatin (a standard care of therapy), the prognosis for mesothelioma patients is still very low, and median survival is between 12-17 months [

19,

20]. Mesothelioma has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life in both physical and emotional domains, and also substantially affects patients’ families and caregivers. The molecular events during the development of MPM are not well understood. Since there are no reliable biomarkers for detecting MPM, managing the disease becomes very challenging. Therefore, understanding the molecular mechanism by which normal mesothelial cells transform into malignant cells is of paramount importance.

SATB2 (special AT-rich binding protein-2) binds DNA in nuclear matrix attachment regions [

21], and influences gene expression by modulating chromatin architecture and acting as a transcriptional co-factor [

22,

23]. The SATB2 gene is conserved in humans and mice. Structurally, five highly conserved domains are found in SATB2. They are: a ubiquitin-like domain (ULD), a CUT repeat-like (CUTL) domain, two CUT domains (CUT1 and CUT2), and a homeodomain (HOX) [

24]. Furthermore, SATB2 contains two distinct nuclear matrix-attachment regions (MARs) and multiple ubiquitin-associated modification sites [

25]. As a nuclear matrix protein, SATB2 binds to MARs, regulatory DNA sequences involved in the organization of higher-order chromatin structures [

26]. SATB2 utilizes its CUT domains to anchor to the sugar-phosphate backbone of double-stranded DNA physically. This binding action serves as a molecular anchor for chromatin loops, helping to establish the physical organization of the genome. The establishment of anchored loops facilitates the recruitment of coactivators or corepressors, thereby enabling dynamic regulation of gene expression and chromatin modifications [

23]. Furthermore, SATB2 functions as a scaffold protein, coordinating the assembly of other DNA-binding proteins at specific sub-nuclear sites to enhance transcriptional regulation [

27].

SATB2−/− mice are defective in bone development and osteoblast differentiation [

28]. These findings point to multifunctional roles of SATB2, mediating diverse biological processes, including skeletal formation, craniofacial patterning, osteoblast differentiation, nervous system development, and tumor progression [

27,

28,

29].

SATB2 is overexpressed in colorectal, pancreatic, breast, and prostate cancer, neuroendocrine tumors, and hepatocellular carcinoma, suggesting its use as a diagnostic marker for cancer [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. In breast cancer, SATB2 mRNA expression is significantly associated with increasing tumor grade and poorer survival [

38]. Higher SATB2 expression was correlated with immune cell infiltration [

31]. It inhibited T cell cytotoxicity while promoting cell migration in pancreatic cancer, suggesting its potential as a target to enhance pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. However, the tumor-promoting and metastatic roles of SATB2 in mesothelioma have never been examined.

Malignant transformation is a complex process in which a normal cell develops into a cancerous cell. This transformation can occur through several mechanisms, including genetic mutations, changes in cellular regulatory mechanisms, the generation of reactive oxygen species, and the accumulation of mutations that confer a malignant phenotype. This transformation can generate cancer stem cells (CSCs) that express stem cell markers and pluripotency-maintaining factors. Our recent work has demonstrated that overexpression of the SATB2 gene induced malignant transformation in human breast, prostate, colorectal, and pancreatic epithelial cells and hepatocytes, resulting in the generation of functional CSCs [

36,

37,

39,

40,

41]. These CSCs are responsible for cancer initiation, progression, drug resistance, and chemotherapy failure [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Although the oncogenic role of SATB2 in specific cancers has been demonstrated, its biological functions in the malignant transformation of mesothelial cells have not been examined.

The objectives of this paper were to determine whether the SATB2 gene can induce cellular transformation in mesothelial cells and whether inhibiting its expression in MPM CSCs reversed drug resistance. Our data demonstrated that overexpression of SATB2 in mesothelial cells induced malignant transformation and that inhibiting its expression with shRNA in MPM cells suppressed cell growth, EMT, spheroid formation, and CSC characteristics. Inhibition of SATB2 expression in MPM CSCs by shRNA reversed drug-resistance to cisplatin and pemetrexed. SATB2 can be considered a therapeutic target in MPM, and inhibiting SATB2 in combination with chemotherapy may be a viable option for MPM treatment.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Cell Culture Conditions

Antibodies against E-Cadherin, N-cadherin, SATB2, cMyc, Oct4, and XIAP were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Anti-β-Actin antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blot detection reagents were purchased from Amersham Life Sciences Inc. (Arlington Heights, IL). Human mesothelioma cell lines H2714, H2452, and H2595, and mesothelial cell line Met5A (CRL-9444) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA. The Met5A cell line was derived from human adult pleural mesothelial cells. Mesothelioma cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Met5A cells were grown in Medium 199 supplemented with FBS (10%), epidermal growth factor (10 ng/ml), hydrocortisone (400 nM), human recombinant insulin (870 nM), and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. Cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Lentiviral Particle Production and Transduction

Transfection of packaging cells and infection of mesothelioma cells were performed using standard protocols with minor modifications [

48]. In brief, 293T cells were transfected with 4 µg of plasmid using lipid transfection (Lipofectamine-2000/Plus reagent, Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Viral supernatants were collected and concentrated by adding PEG-it virus precipitation solution (SBI System Biosciences) to produce virus stocks with titers of 1x10

8 to 1x10

9 infectious units per ml. Viral supernatant was collected by ultracentrifugation over three days and concentrated 100-fold. Met5A and mesothelioma cells were infected with lentiviral particles containing the gene of interest.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated on coverslips for 24 hr and then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After fixation, samples were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min and thereafter blocked with 10% fetal calf serum in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma). For SATB2 staining, cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-SATB2 antibody (Abcam), followed by 1 hour at room temperature with the secondary antibody. Nuclear DNA was stained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fluorescent images were acquired using a fluorescent microscope with NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Motility Assay

We used the scratch motility assay to monitor the horizontal movement of cells, as described elsewhere [

48]. Cells were seeded in a 6-well cell culture plates. After a monolayer of cells was established, a scratch was made, resulting in an in vitro wound. Plates were washed twice with PBS and then replaced with cell culture medium. Movement of cells to the scratch area, as single cells from the confluent sides, was monitored. The width of the scratch gap is viewed under the microscope in four separate regions each day until the gap is filled in the untreated control wells.

Transwell Migration Assay

Migration assay was performed as described elsewhere [

49]. In brief, mesothelioma cells (1x10

5) were plated in the top chamber of a 24-well insert (pore size, 8 μm; Corning Costar) and allowed to migrate toward serum-containing medium in the lower chamber. After 24 hrs of incubation, cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal-violet (Sigma-Aldrich). The number of cells migrated through the membrane was counted under a light microscope (Nikon).

Transwell Invasion Assay

Invasion assay was performed as described elsewhere [

49]. In brief, cells (1x10

5) were plated in the top chamber onto the Matrigel-coated Membrane (24-well insert; pore size, 8 μM; Corning Costar). Cells were plated in medium without serum or growth factors, and medium supplemented with serum was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chamber. The cells were incubated for 48 hours, and a cotton swab removed cells that did not invade through the pores. Cells on the lower surface of the membrane were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal-violet, and counted in five independent fields/well under a light microscope (Nikon).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher), including the following protease and phosphatase inhibitors: Protease Inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), Halt™ Phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 (Sigma) and 3 (Sigma). Proteins were separated in SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Fisher). Membranes were blocked with 5% dry milk in TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 at 370C for 2 hours. Nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were probed with primary antibody diluted in Tris-buffered saline (1:1000 dilutions) overnight at 4° C with gentle shaking. Proteins were visualized with ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare) as previously described (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Briefly, cDNA was synthesized using cDNA kit from Applied Biosystems according the manufacturer’s protocol. For quantification of gene amplification, Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System with SYBR Green. Target sequences were amplified at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. HK-GAPD was used as an endogenous normalization control. All assays were performed in triplicate and were calculated based on ΔΔ

Ct method. The n-fold change in mRNAs expression was determined according to the method of 2

-ΔΔCT. PCR primers were designed using PrimerBank (

http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/ primerbank). The primer sequences were published in our earlier papers [

36,

37,

39,

40].

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed as we described elsewhere [

39]. In brief, Protein-DNA complexes were crosslinked with formaldehyde solution (50mM HEPES KOH, pH 7.5, 1mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, 11% Formaldehyde) for 10 min at room temperature. Mesothelioma cells were harvested, and cell suspensions were centrifuged. For nuclei purification, cell pellets were washed in PBS, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and consecutively incubated in ice-cold hypotonic wash buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 10% Glycerol, 20 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF) including protease inhibitors for 10 min at 4° C and lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% Triton X-100, 1mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF) with protease inhibitors. Nuclei were washed in ice-cold wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1mM DTT). Chromatin in nuclear extract was sheared by sonication, clarified by centrifugation, and the supernatant was used for immunoprecipitation. Chromatin was incubated overnight with an anti-SATB2 antibody or mouse IgG (Cell Signaling), then precipitated with 5 μl of protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher). Protein-DNA complexes were eluted, decrosslinked at 65° C overnight, and after RNase (0.2 mg/ml) and proteinase K (0.2 mg/ml) treatment, the DNA was purified, and the DNA enrichment was measured by PCR using promoter-specific primers.

Statistical Analysis

The unpaired Student’s t-test assessed statistical significance between two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze more than two groups. A two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze cell proliferation across multiple time points. GraphPad Prism 7 and 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) was used to perform all statistical calculations. Data is presented as mean ± SD, and a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

We have demonstrated, for the first time, that overexpression of SATB2 alone can induce transformation in human mesothelial cells. These transformed cells acquired the phenotypes of CSCs, as they express pluripotency-maintaining factors Nanog, Oct4, Sox2, cMyc, and KlF4. These SATB2-transformed cells formed mesospheres in suspension, a characteristic of CSCs. Also, they acquired EMT characteristics, as evidenced by down-regulation of E-cadherin and up-regulation of N-cadherin, and by enhanced cell motility, migration, and invasion. Inhibition of SATB2 with shRNA sensitized CSCs to cisplatin and premetrexed. Overall, our study suggests that the SATB2 gene alone can induce oncogenic transformation of mesothelial cells, and inhibition of its expression could be beneficial for reversing drug resistance in MPM.

SATB2 as a therapeutic target for some cancers has recently been suggested. We have previously shown that overexpression of SATB2 in human normal pancreatic, breast, colorectal, and prostate epithelial cells, and hepatocytes, induces malignant transformation by generating CSCs [

36,

37,

39,

40,

53]. In the present study, we have demonstrated that overexpression of SATB2 induces Met5A cell transformation, and these transformed cells exhibit characteristics of CSCs, similar to those found in humans and mice. [

54]. We also demonstrate that SATB2 is not expressed in Met5A cells, but it is highly expressed in human mesothelioma cell lines. Furthermore, inhibition of SATB2 expression in mesothelioma cells suppresses cell proliferation, colony formation, cell motility, migration, and invasion. SATB2 interacts with other transcription factors to enhance or repress gene expression [

55]. In tumors, SATB2 can serve as a biomarker and a potential therapeutic target due to its role in regulating oncogenic and tumor-suppressor pathways [

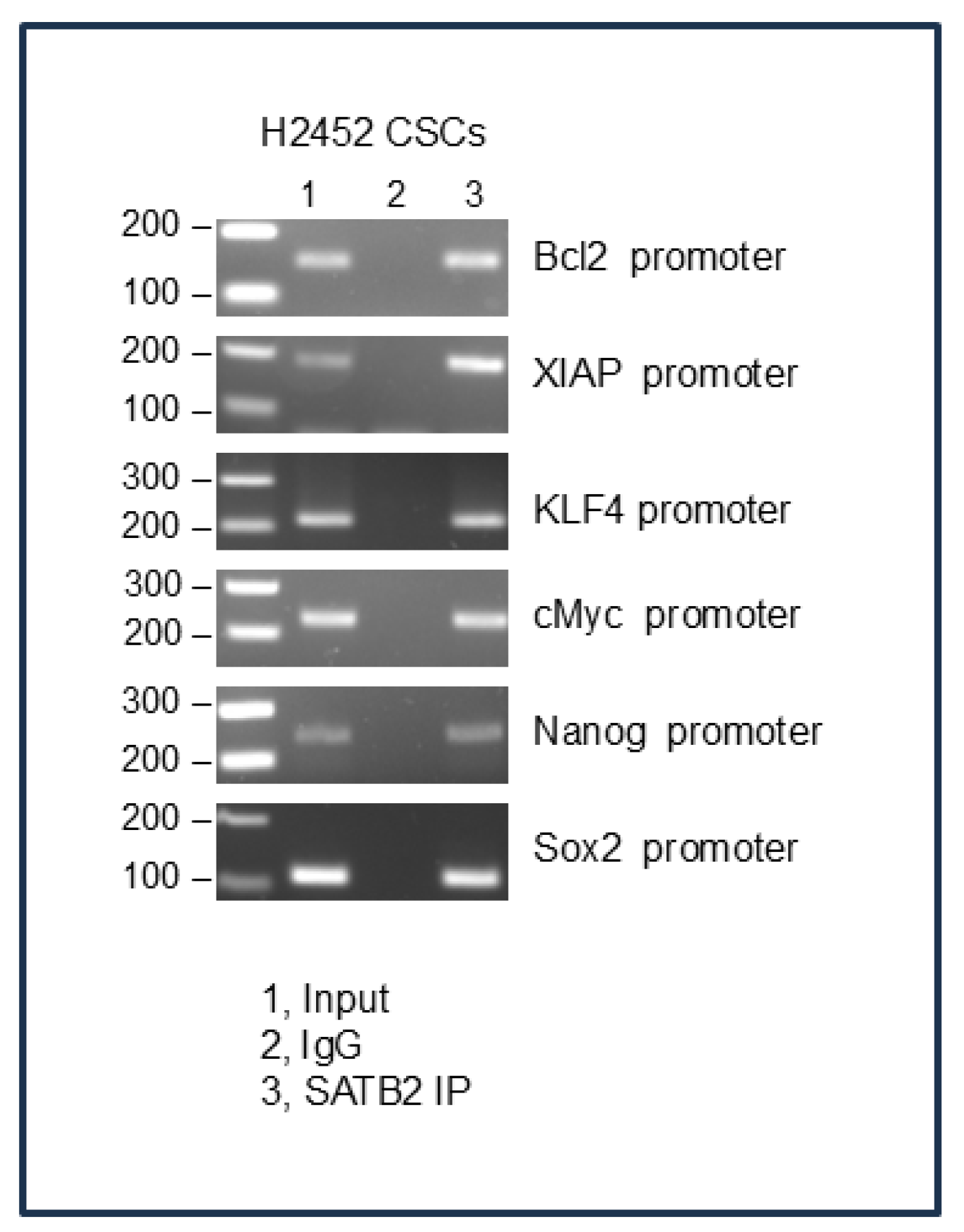

56]. Our ChIP assays demonstrate that SATB2 directly binds the promoters of Bcl2, Xiap, Bsp, Klf4, Myc, Hoxa2, and Nanog, which plays significant roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, EMT and stemness. Overall, our data suggests that SATB2 can promote EMT and metastasis.

Recent studies in solid organ cancers have shown that CSCs are a subset of malignant precursors responsible for initiation, progression, resistance to cytotoxic drugs, recurrence, and metastasis [

57]. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma tumors harbor stem cells with tumorigenic potential, with significant implications for understanding the cells of origin and tumor progression in MPM [

47]. The side population of malignant mesothelioma cells contains CSCs that express CD9, CD24, and CD26, which could serve as novel therapeutic targets [

44]. CD24 knockdown in MM CSCs led to loss of mesosphere-forming capacity and reduced tumorigenicity in immunodeficient mice [

58]. The OCT4/SOX2 reporter method was used to identify CSC-enriched MM cell subpopulations that were resistant to cisplatin [

59]. In another study, the cisplatin plus aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) inhibitor, diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB)-resistant MPM cells showed upregulated mRNA expression for ALDH1A2, ALDH1A3, and CD44, indicating the involvement of these markers in conferring chemoresistance [

60]. Similarly, we showed that MPM cells can be enriched for CSCs that expressed stem cell markers and pluripotency-maintaining factors. Furthermore, induction of drug sensitivity by SATB2 shRNA resulted in reduced mesosphere formation and cell viability. Our study provides evidence of putative CSCs conferring drug resistance to cisplatin and pemetrexed in MPM. Targeting these drug-resistant MPM CSCs by SATB2 shRNA may lead to more focused and effective chemotherapeutic regimens for MPM.

In conclusion, our data suggest that SATB2 can induce cellular transformation of normal mesothelial cells into cancer stem-like cells. SATB2 can regulate several cellular functions by modulating the expression of genes involved in malignant transformation, pluripotency, cell survival, proliferation, and EMT. Induction of drug sensitivity by SATB2 shRNA resulted in reduced mesosphere formation and cell viability, and CSCs confer cisplatin- and premetrexed-resistance. Overall, targeting CSCs may be a valuable strategy to inhibit malignant progression. SATB2 can be considered a therapeutic target in MPM, and inhibiting SATB2 in combination with chemotherapy may be a viable option for MPM treatment.

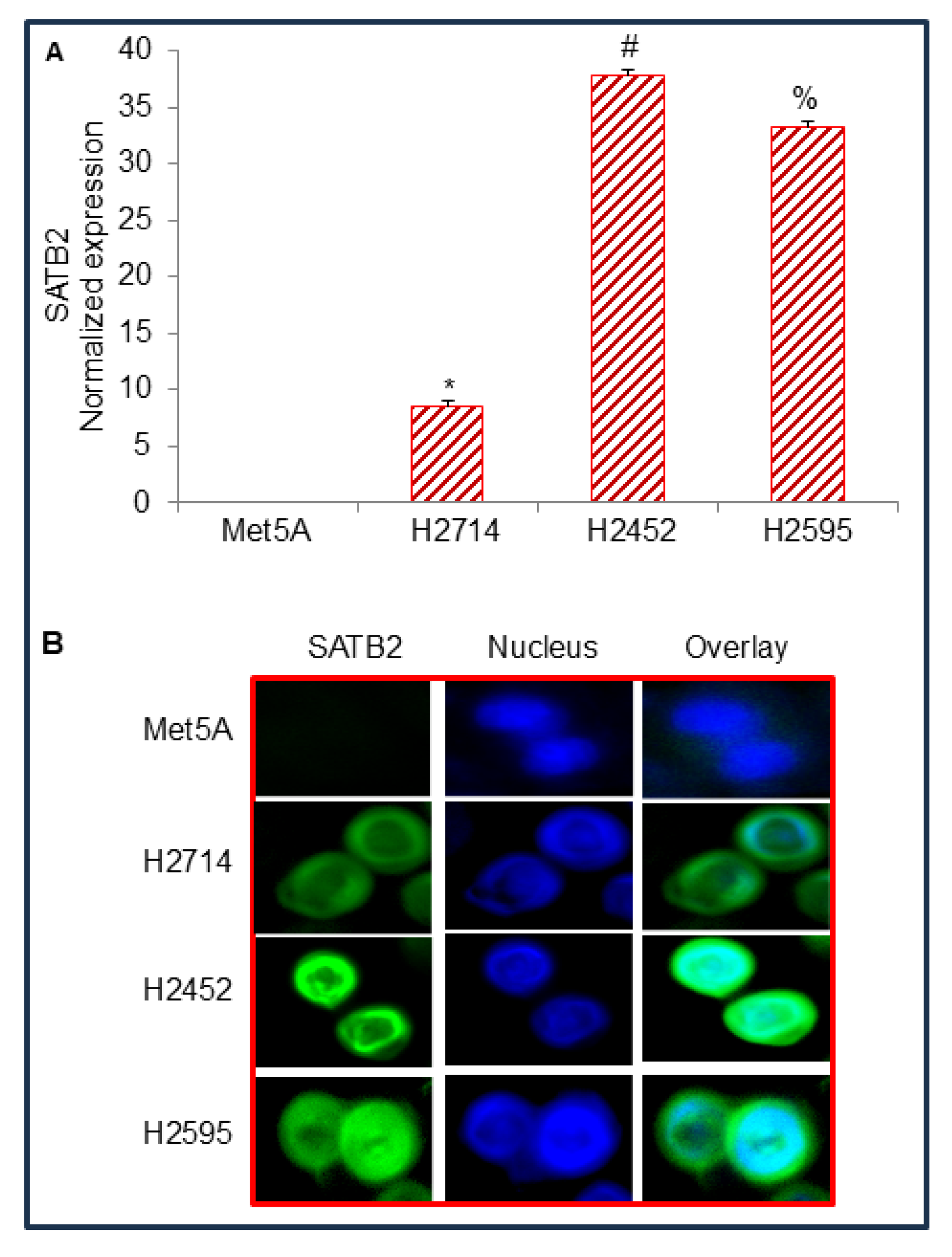

Figure 1.

The expression of SATB2 in Met5A, and mesothelioma cell lines. (A), Expression of SATB2 mRNA in human normal mesothelial Met5A cells and mesothelioma cell lines. RNA was isolated, and qRT-PCR was used to measure SATB2 expression. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from Met5A (P < 0.05). (B), SATB2 expression by immunocytochemistry. Mesothelial and mesothelioma Met5A, H2714, H2452, and H2595 cells were grown in coverslips, fixed, and stained with anti-SATB2 antibody (Abcam) for 24 hr at 4 0C. Cells were then stained with secondary antibody and DAPI. Coverslips were mounted onto the glass slides and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Green color = SATB2, Blue color = Nuclei.

Figure 1.

The expression of SATB2 in Met5A, and mesothelioma cell lines. (A), Expression of SATB2 mRNA in human normal mesothelial Met5A cells and mesothelioma cell lines. RNA was isolated, and qRT-PCR was used to measure SATB2 expression. GAPDH was used as an internal control. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from Met5A (P < 0.05). (B), SATB2 expression by immunocytochemistry. Mesothelial and mesothelioma Met5A, H2714, H2452, and H2595 cells were grown in coverslips, fixed, and stained with anti-SATB2 antibody (Abcam) for 24 hr at 4 0C. Cells were then stained with secondary antibody and DAPI. Coverslips were mounted onto the glass slides and visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Green color = SATB2, Blue color = Nuclei.

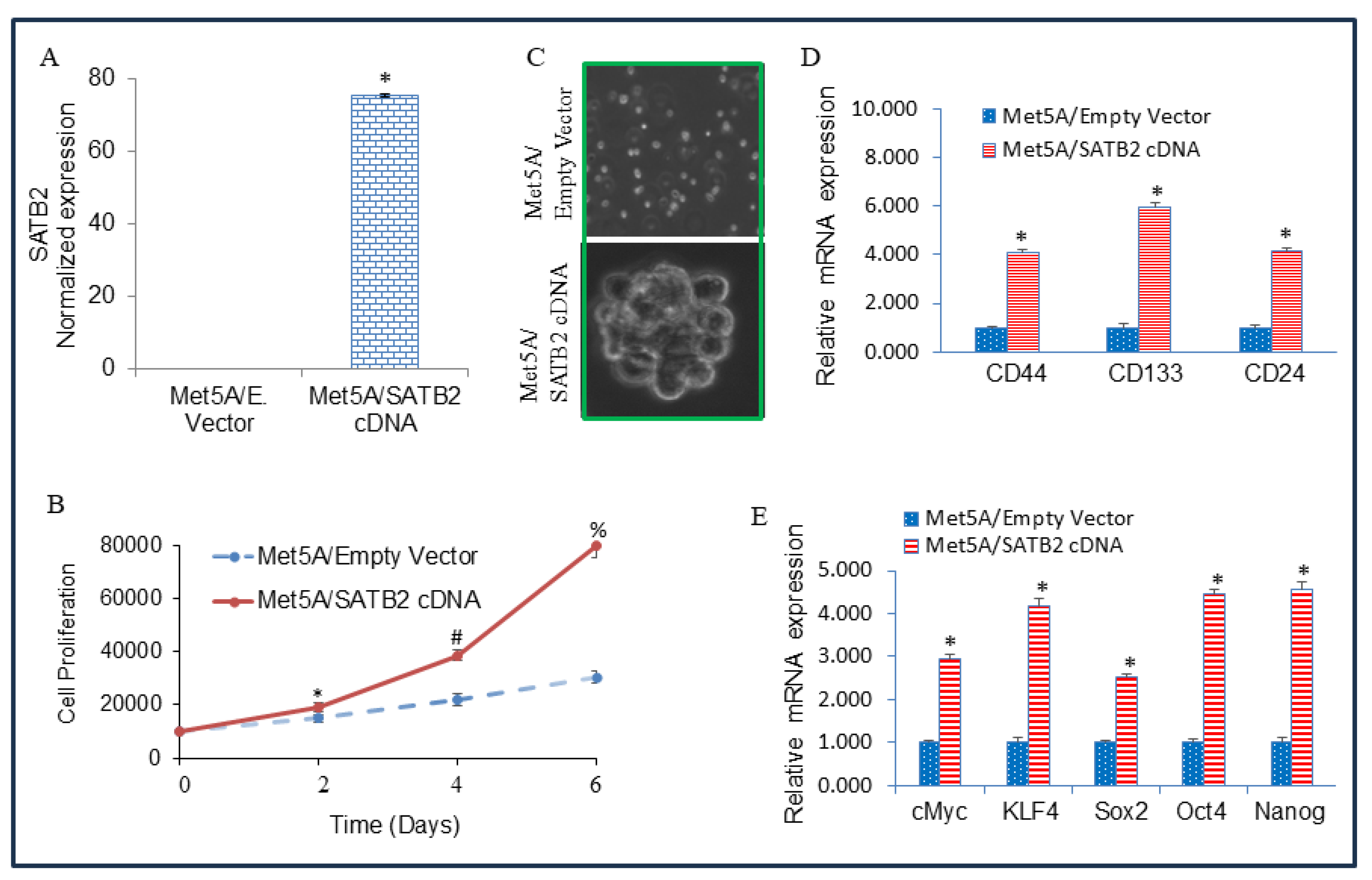

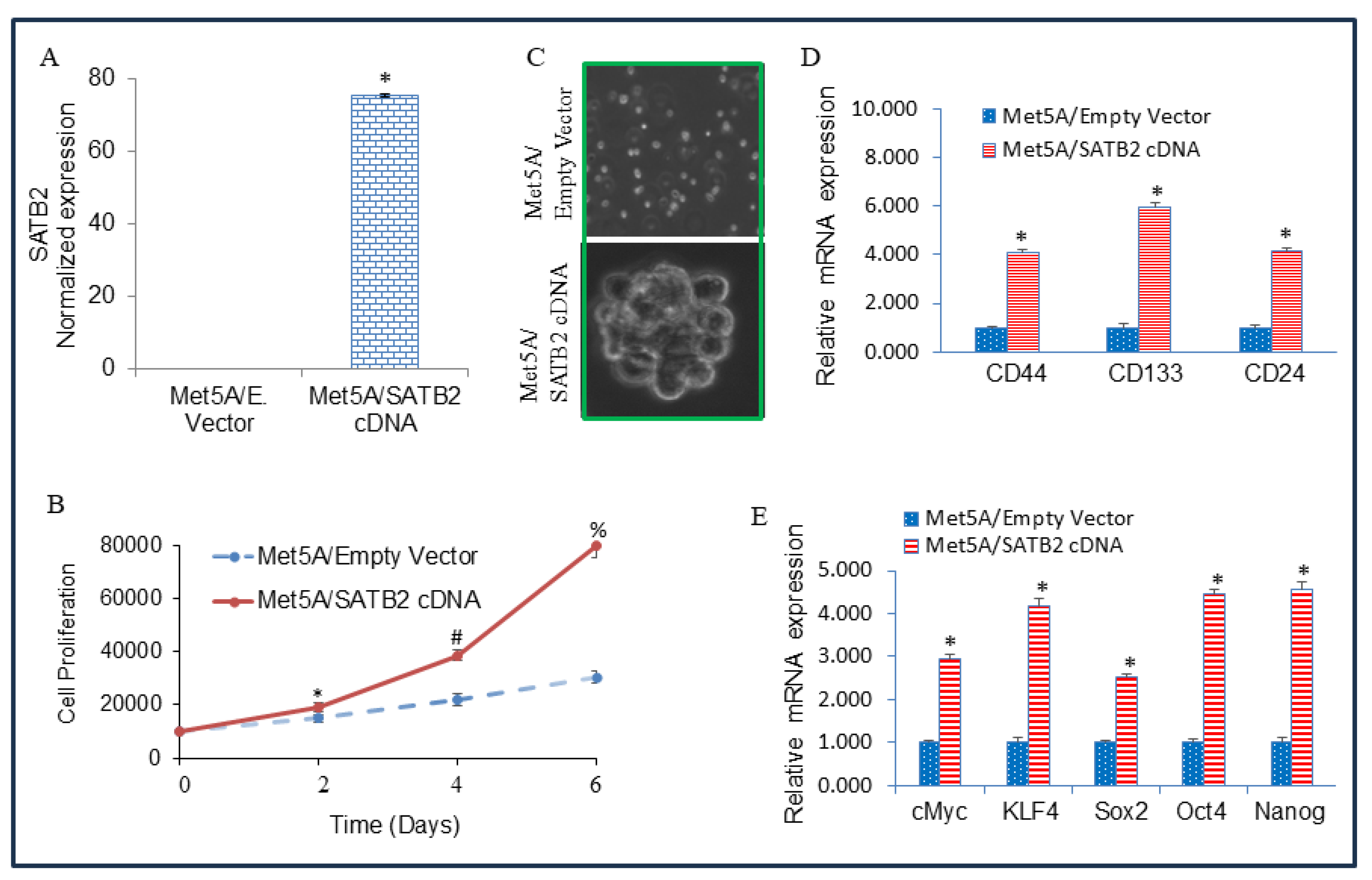

Figure 2.

Overexpression of SATB2 in Met5A cells induces cellular transformation and stemness. (A) Met5A cells were stably transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either empty vector or SATB2 cDNA. QRT-PCR measured SATB2 expression. Data represent mean (n= 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from each other, P < 0.05. (B), Cell proliferation. Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells were grown, and cell proliferation was measured over 6 days. *, # and % = significantly different from respective empty vector group, P < 0.05. (C) Spheroid formation. Spheroid formation by Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells in suspension was measured as we described elsewhere [

37,

39]. Mesospheres formed in 3 weeks were photographed. Cells transduced with an empty vector did not form any mesospheres. (D) RNA was isolated from Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. The expression of stem cell markers CD44, CD133, and CD24 was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. * = significantly different from Met5A/Empty Vector group (P < 0.05). Gene expression of Empty Vector was normalized to 1. (E) RNA was isolated from Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. The expression of pluripotency-maintaining factors (cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog) was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. * = significantly different from Met5A/Empty Vector group (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of SATB2 in Met5A cells induces cellular transformation and stemness. (A) Met5A cells were stably transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either empty vector or SATB2 cDNA. QRT-PCR measured SATB2 expression. Data represent mean (n= 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from each other, P < 0.05. (B), Cell proliferation. Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells were grown, and cell proliferation was measured over 6 days. *, # and % = significantly different from respective empty vector group, P < 0.05. (C) Spheroid formation. Spheroid formation by Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells in suspension was measured as we described elsewhere [

37,

39]. Mesospheres formed in 3 weeks were photographed. Cells transduced with an empty vector did not form any mesospheres. (D) RNA was isolated from Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. The expression of stem cell markers CD44, CD133, and CD24 was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. * = significantly different from Met5A/Empty Vector group (P < 0.05). Gene expression of Empty Vector was normalized to 1. (E) RNA was isolated from Met5A/Empty Vector and Met5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. The expression of pluripotency-maintaining factors (cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog) was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. * = significantly different from Met5A/Empty Vector group (P < 0.05).

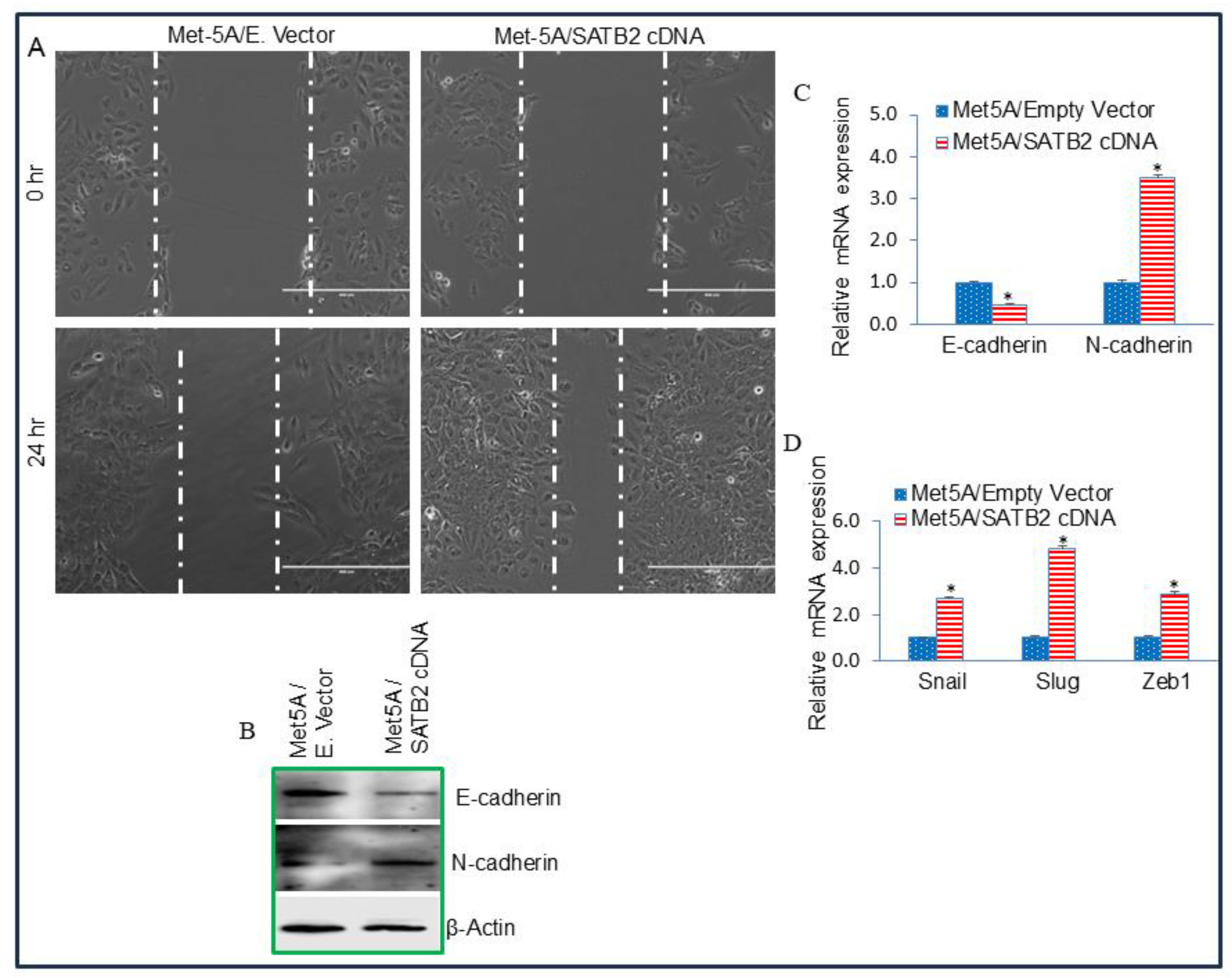

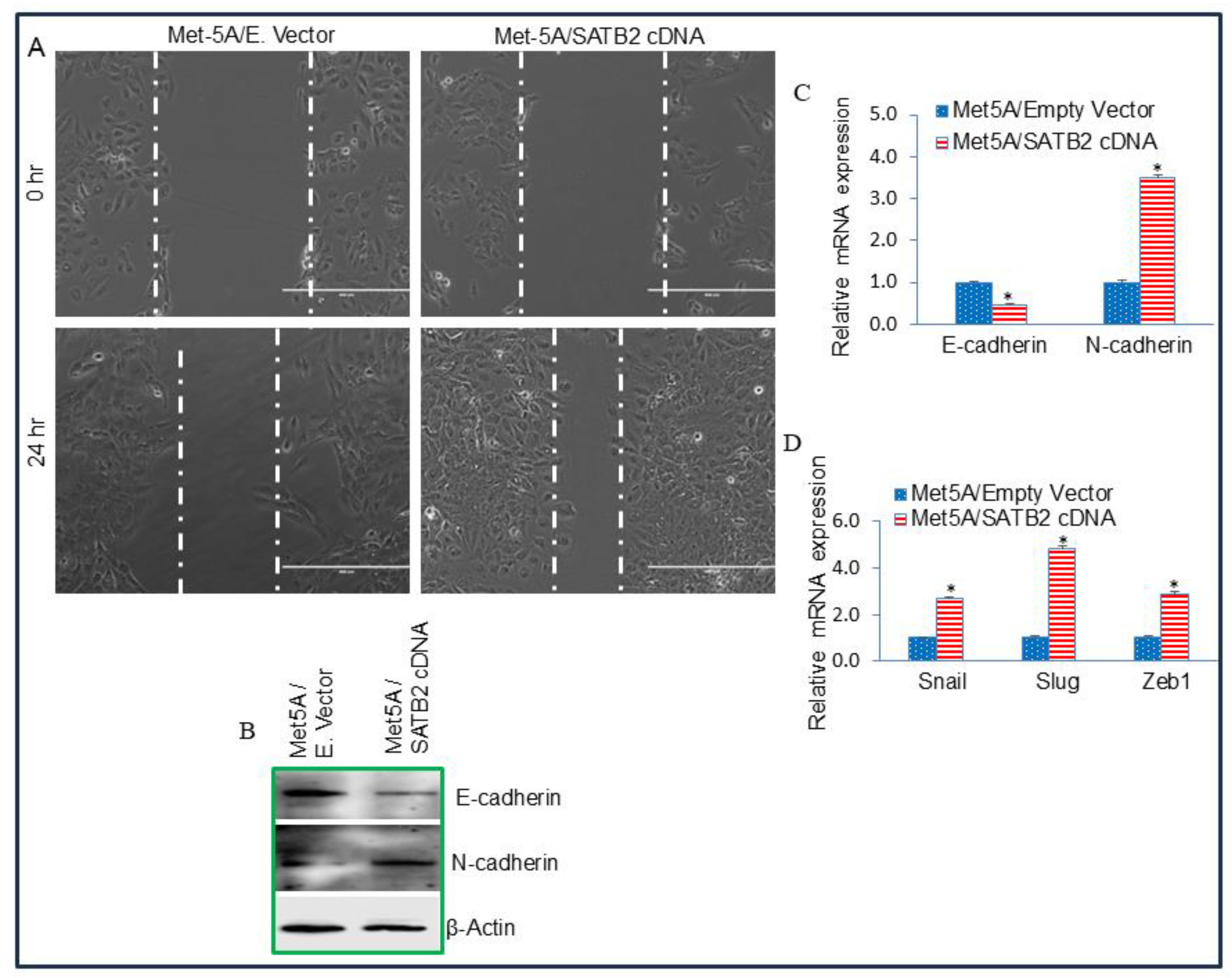

Figure 3.

Overexpression of SATB2 in MET5A cells induces EMT characteristics (A) Cell Motility assay. MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells were grown in petri dishes. After cell attachment, scratch lines were created using fine pipette tips in both groups. Phase-contrast images of scratched dishes were captured at 0 h and 24 h. (B), Protein expression of Cadherins. Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) mRNA expression of Cadherins in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. RNA was isolated, and the expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from MET5A/Empty Vector (P < 0.05). Gene expression of the Empty Vector group was normalized to 1. (D) Expression of EMT-related transcription factors in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. RNA was isolated, and the expression of Snail, Slug, and Zeb1 was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from MET5A/Empty Vector (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Overexpression of SATB2 in MET5A cells induces EMT characteristics (A) Cell Motility assay. MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells were grown in petri dishes. After cell attachment, scratch lines were created using fine pipette tips in both groups. Phase-contrast images of scratched dishes were captured at 0 h and 24 h. (B), Protein expression of Cadherins. Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) mRNA expression of Cadherins in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. RNA was isolated, and the expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from MET5A/Empty Vector (P < 0.05). Gene expression of the Empty Vector group was normalized to 1. (D) Expression of EMT-related transcription factors in MET5A/Empty Vector and MET5A/SATB2 cDNA cells. RNA was isolated, and the expression of Snail, Slug, and Zeb1 was measured by qRT-PCR analysis. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from MET5A/Empty Vector (P < 0.05).

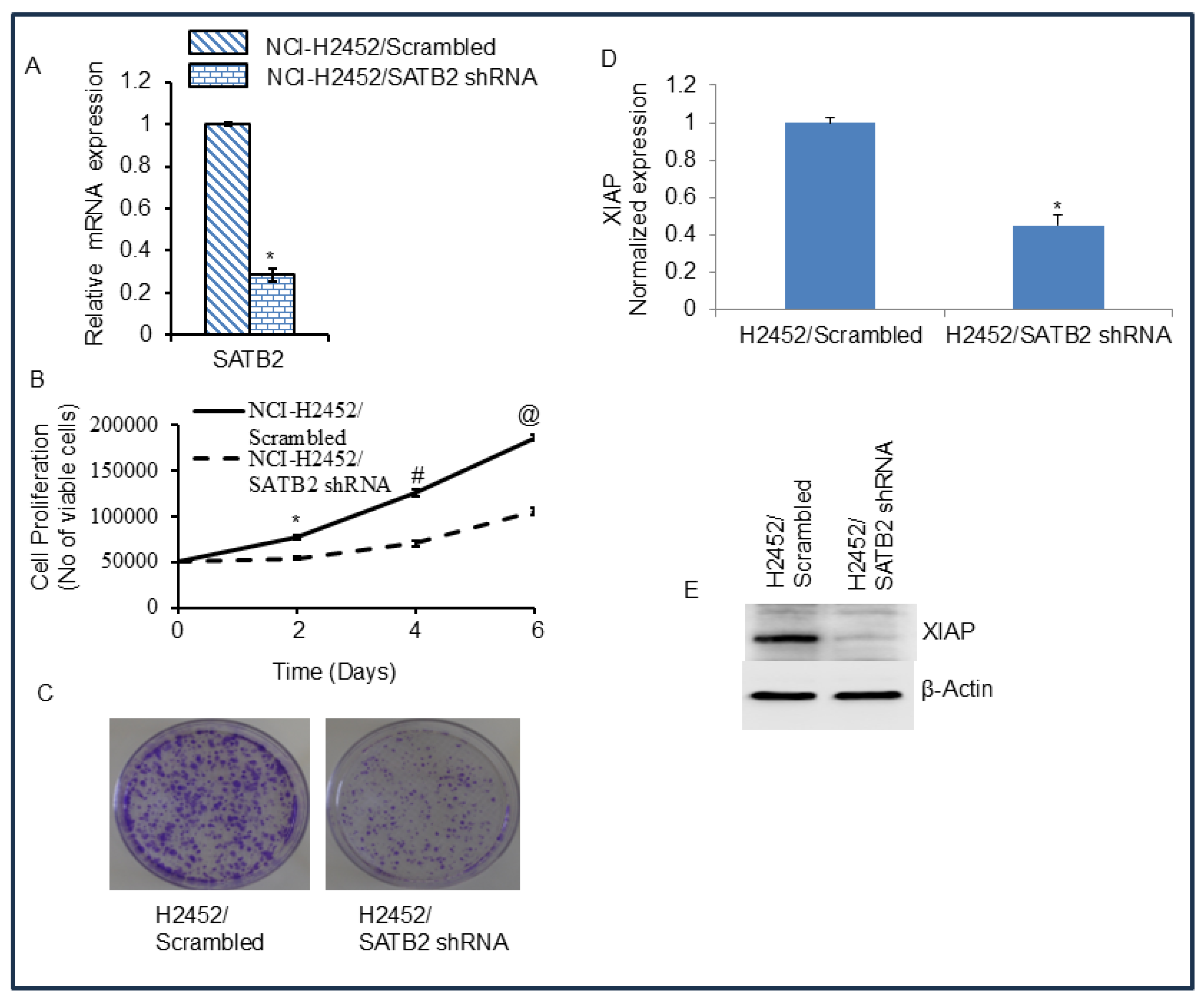

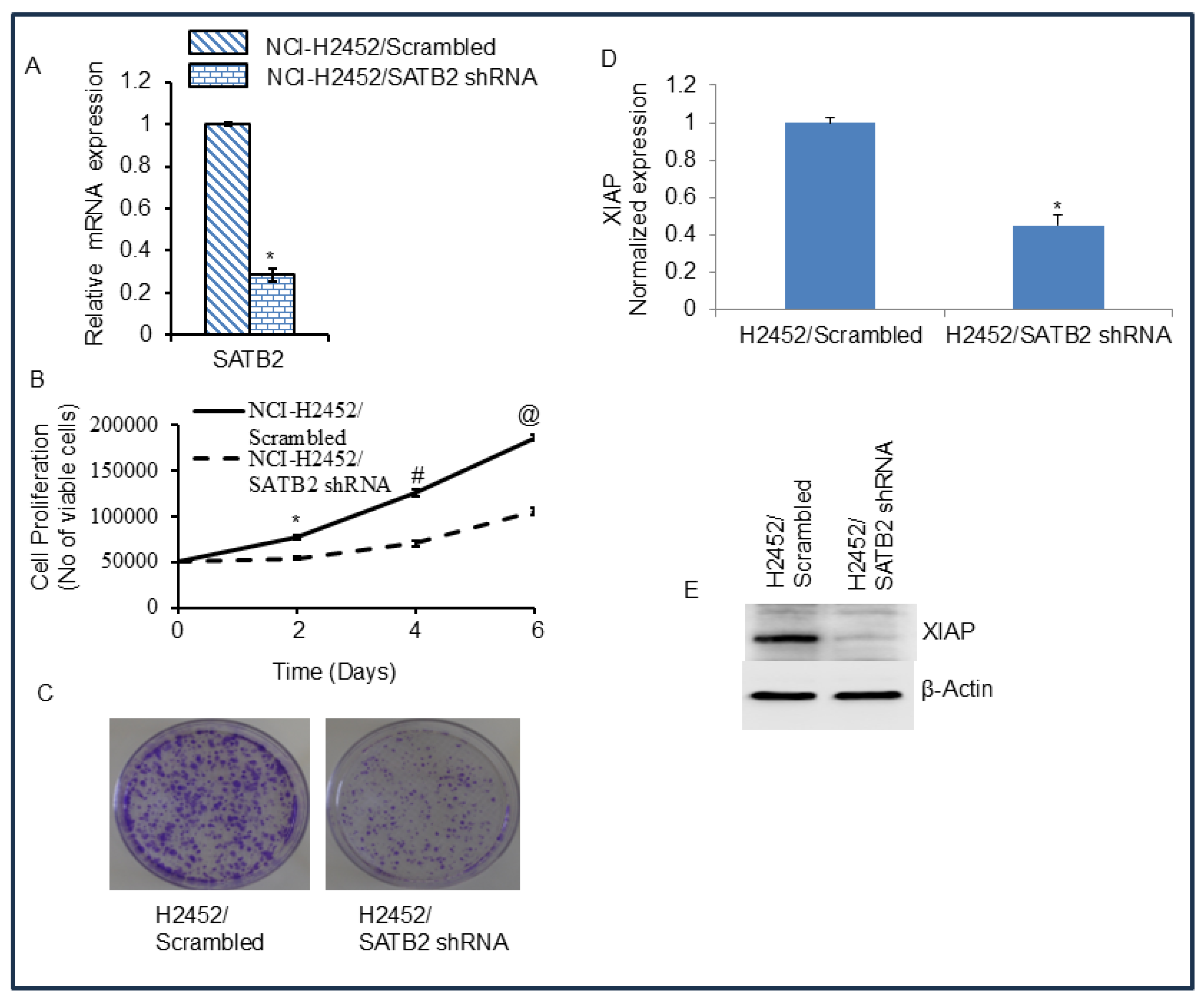

Figure 4.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits cell proliferation, colony formation, and XIAP expression in H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 cells. (A), SATB2 expression. H2452 cells were transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either scrambled or SATB2 shRNA (a mixture targeting four sites, Thermo Fisher). qRT-PCR was performed to measure SATB2 expression. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from H2452/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (B), Cell proliferation of H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA groups was measured over 6-day period. *, # and @ = significantly different from H2452/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (C), Colony formation Assay. H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA cells were seeded, and colonies formed at 21 days were photographed. (D), Expression of XIAP mRNA. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. XIAP expression was measured by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of XIAP protein. Crude protein was isolated from H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA cells, and the Western blot analysis was performed to measure XIAP expression. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 4.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits cell proliferation, colony formation, and XIAP expression in H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 cells. (A), SATB2 expression. H2452 cells were transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either scrambled or SATB2 shRNA (a mixture targeting four sites, Thermo Fisher). qRT-PCR was performed to measure SATB2 expression. Data represent mean (n = 4) ± SD. * = significantly different from H2452/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (B), Cell proliferation of H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA groups was measured over 6-day period. *, # and @ = significantly different from H2452/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (C), Colony formation Assay. H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA cells were seeded, and colonies formed at 21 days were photographed. (D), Expression of XIAP mRNA. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. XIAP expression was measured by qRT-PCR. GAPDH was used as an internal control. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of XIAP protein. Crude protein was isolated from H2452/Scrambled and H2452/SATB2 shRNA cells, and the Western blot analysis was performed to measure XIAP expression. β-actin was used as a loading control.

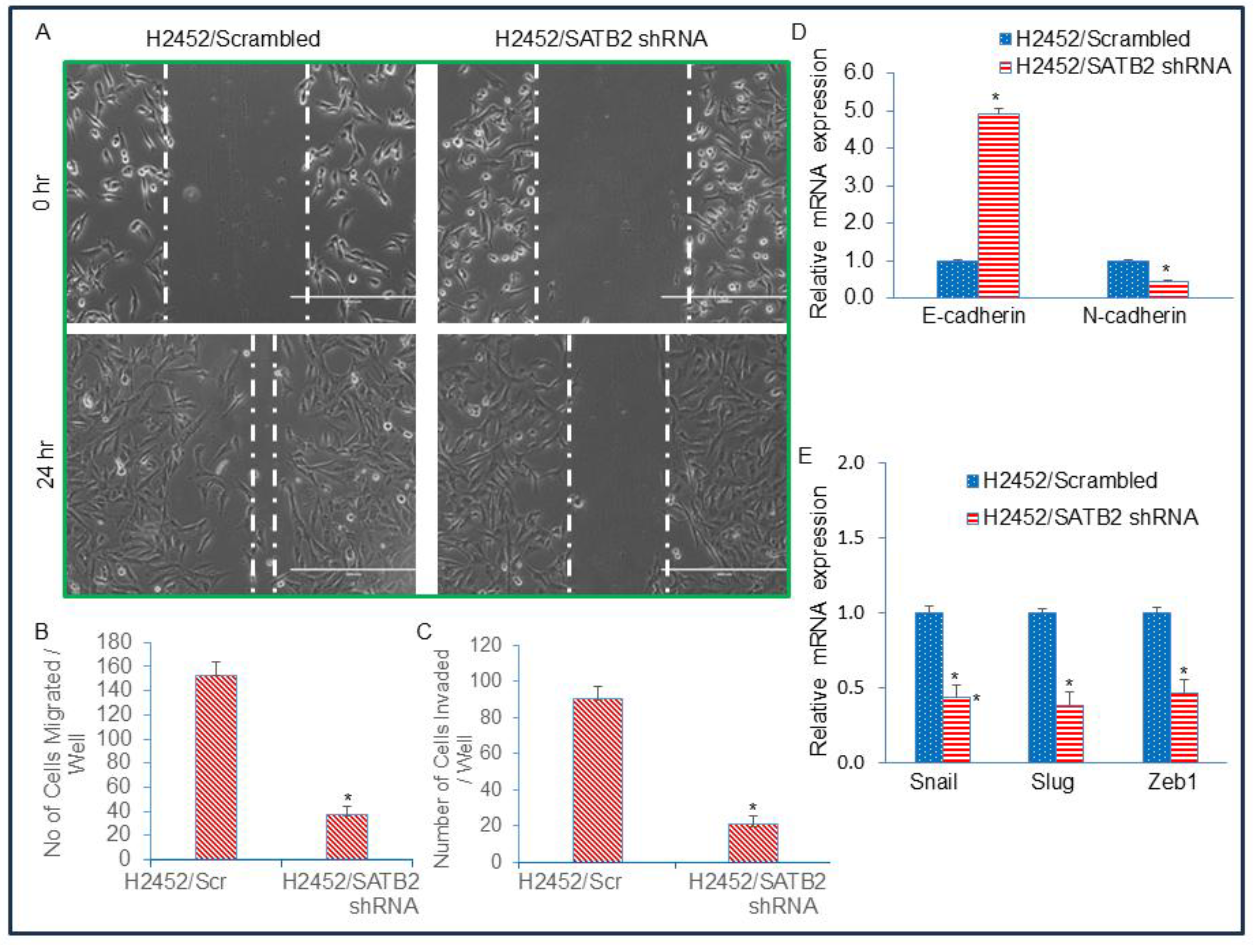

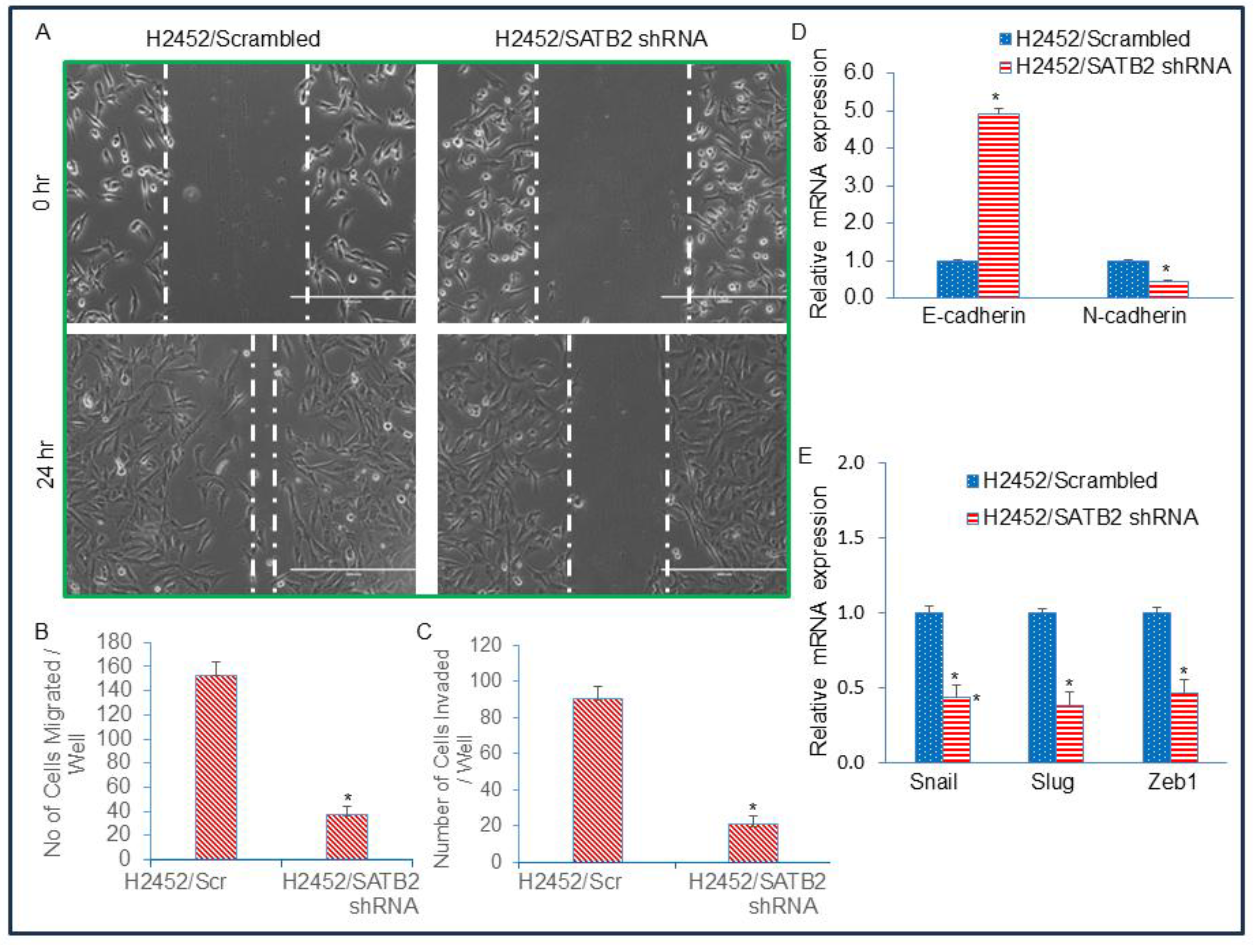

Figure 5.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits cell motility, migration, and invasion and regulates EMT-related genes and transcription factors in H2452 cells. (A), Cell Motility Assay. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in petri dishes. The next day, the dishes were scratched with the fine pipette tips. Cells were washed with PBS, and the cultured medium was changed. Phase-contrast images of scratched dishes were captured at 0 h and 24 h. (B), Transwell Migration Assay. Transwell migration assay was performed in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean (n=4) ± SD. * = significantly different at P < 0.05. (C), Transwell Invasion Assay. Transwell invasion assay was performed in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells as described in Materials and Methods. * = significantly different at P < 0.05. (D), Expression of Cadherins. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. The expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin was measured by qRT-PCR. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of EMT-related transcription factors. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. The expression of Snail, Slug, and Zeb1 was measured by qRT-PCR. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits cell motility, migration, and invasion and regulates EMT-related genes and transcription factors in H2452 cells. (A), Cell Motility Assay. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in petri dishes. The next day, the dishes were scratched with the fine pipette tips. Cells were washed with PBS, and the cultured medium was changed. Phase-contrast images of scratched dishes were captured at 0 h and 24 h. (B), Transwell Migration Assay. Transwell migration assay was performed in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells as described in Materials and Methods. Data represent mean (n=4) ± SD. * = significantly different at P < 0.05. (C), Transwell Invasion Assay. Transwell invasion assay was performed in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells as described in Materials and Methods. * = significantly different at P < 0.05. (D), Expression of Cadherins. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. The expression of E-cadherin and N-cadherin was measured by qRT-PCR. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of EMT-related transcription factors. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. The expression of Snail, Slug, and Zeb1 was measured by qRT-PCR. * = significantly different between groups (P < 0.05).

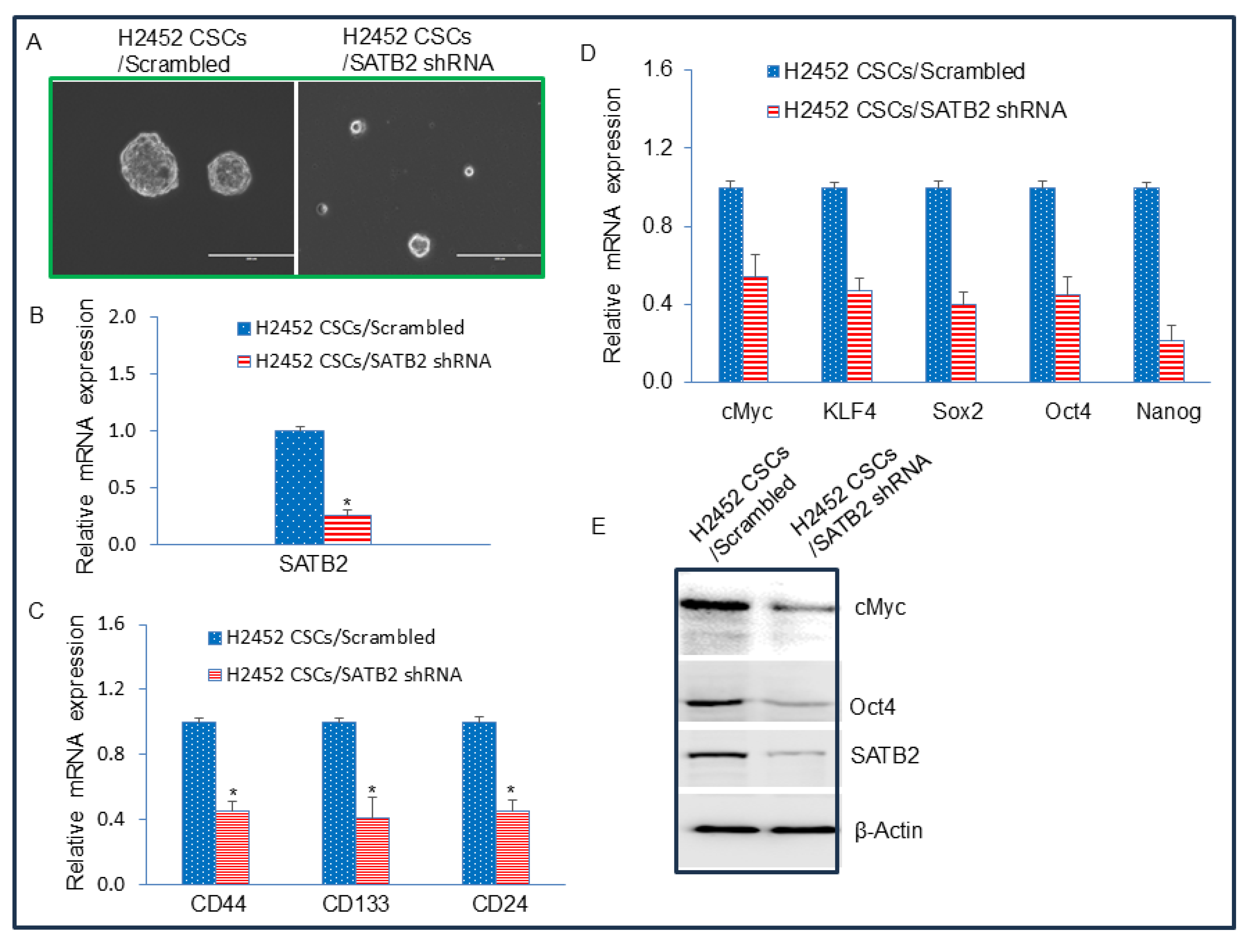

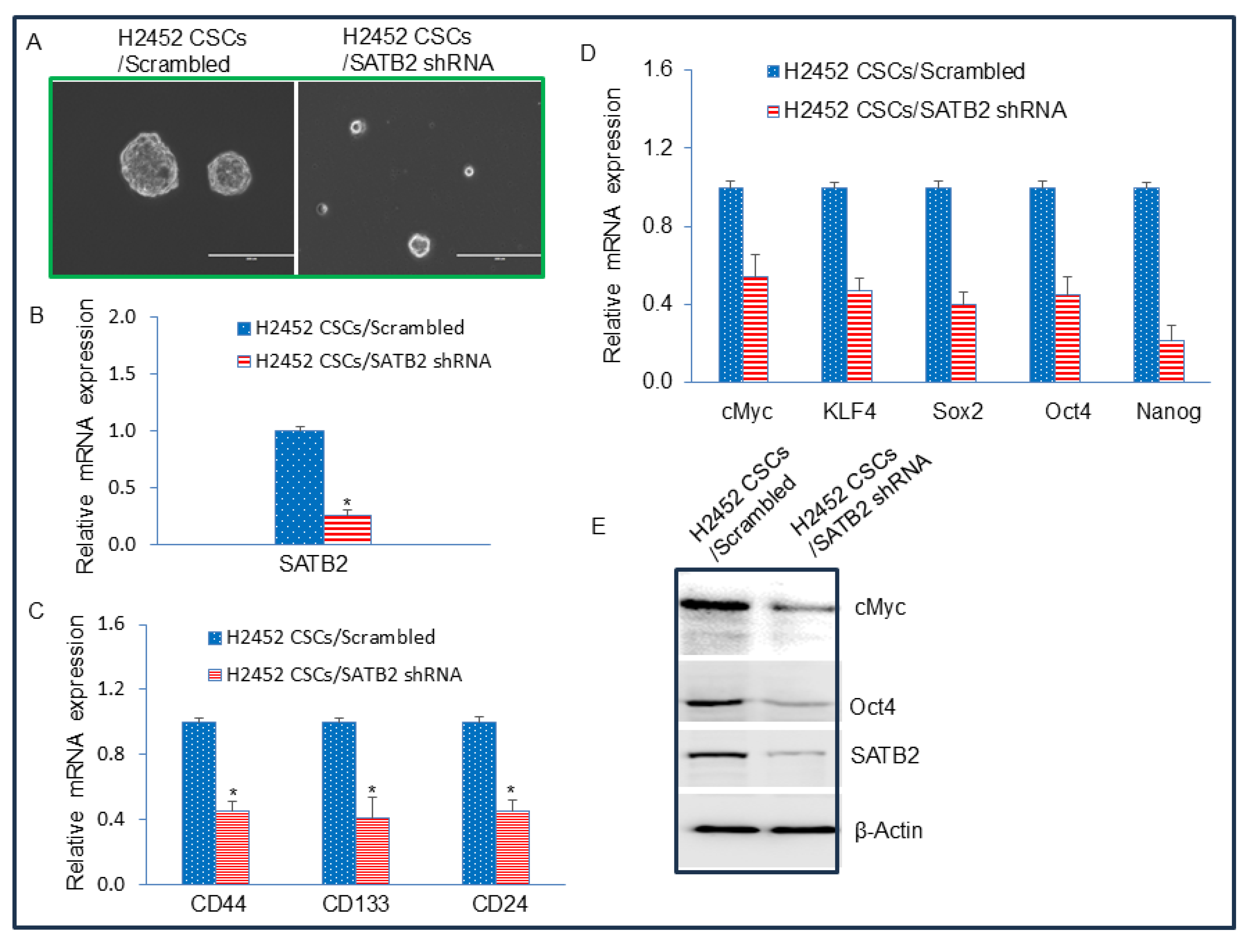

Figure 6.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits spheroid formation, and the expression of stem cell markers and pluripotency factors in CSCs generated from H2452 cells. (A), SATB2 shRNA inhibits spheroid formation in CSCs (side populations) isolated from H2452 cells. H2452 cells were transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either Scrambled (H2452 CSCs/Scrambled) or SATB2 shRNA (H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA). Cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium for 3 weeks. This process enabled us to select and grow the side population of N2452 cells, which exhibited stem-like cell properties. At the end of the incubation period, mesospheres were photographed. (B), Expression of SATB2. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure SATB2 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (C), Expression of CSC markers CD44, CD133 and CD24. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to measure the expression of CSC markers CD44, CD133, and CD24. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (D), Expression of pluripotency maintaining factors cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to measure the expression of cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (E), Protein expression of cMyc, Oct4, and SATB2. Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of SATB2, cMyc, and Oct4 in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 6.

SATB2 shRNA inhibits spheroid formation, and the expression of stem cell markers and pluripotency factors in CSCs generated from H2452 cells. (A), SATB2 shRNA inhibits spheroid formation in CSCs (side populations) isolated from H2452 cells. H2452 cells were transduced with lentiviral particles expressing either Scrambled (H2452 CSCs/Scrambled) or SATB2 shRNA (H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA). Cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium for 3 weeks. This process enabled us to select and grow the side population of N2452 cells, which exhibited stem-like cell properties. At the end of the incubation period, mesospheres were photographed. (B), Expression of SATB2. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure SATB2 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (C), Expression of CSC markers CD44, CD133 and CD24. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to measure the expression of CSC markers CD44, CD133, and CD24. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (D), Expression of pluripotency maintaining factors cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to measure the expression of cMyc, KLF4, Sox2, Oct4, and Nanog. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (E), Protein expression of cMyc, Oct4, and SATB2. Western blot analysis was performed to measure the expression of SATB2, cMyc, and Oct4 in H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. β-actin was used as a loading control.

Figure 7.

Binding of SATB2 to promoters of Bcl-2, XIAP, KLF4, cMyc, Nanog, and Sox2. Nuclear extracts were prepared from H2452 CSCs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as we described in Materials and Methods. ChIP assays revealed SATB2 binding to the promoters of Bcl-2, XIAP, KLF4, cMyc, Nanog, and Sox2 in H2452 CSCs.

Figure 7.

Binding of SATB2 to promoters of Bcl-2, XIAP, KLF4, cMyc, Nanog, and Sox2. Nuclear extracts were prepared from H2452 CSCs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed as we described in Materials and Methods. ChIP assays revealed SATB2 binding to the promoters of Bcl-2, XIAP, KLF4, cMyc, Nanog, and Sox2 in H2452 CSCs.

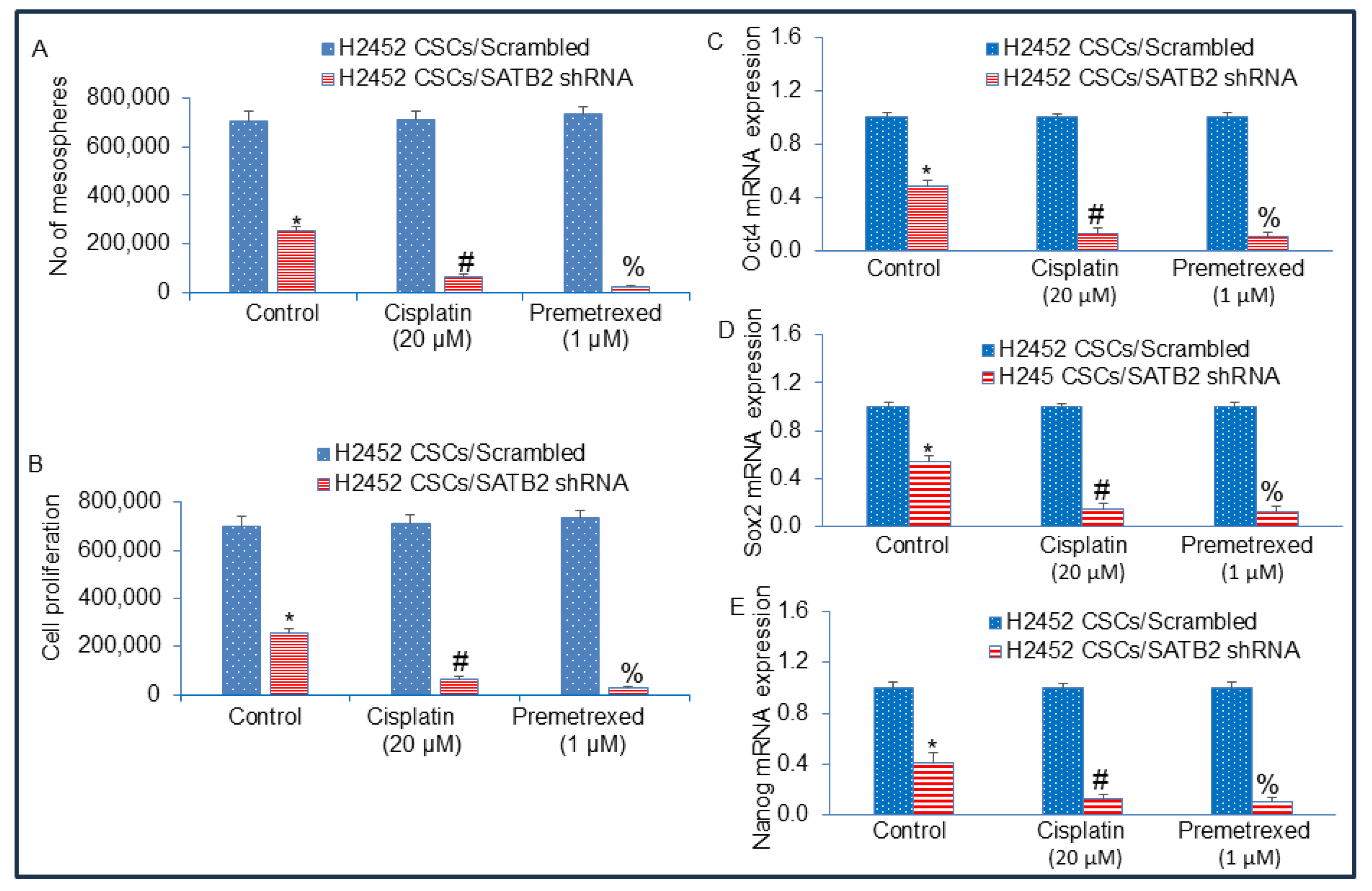

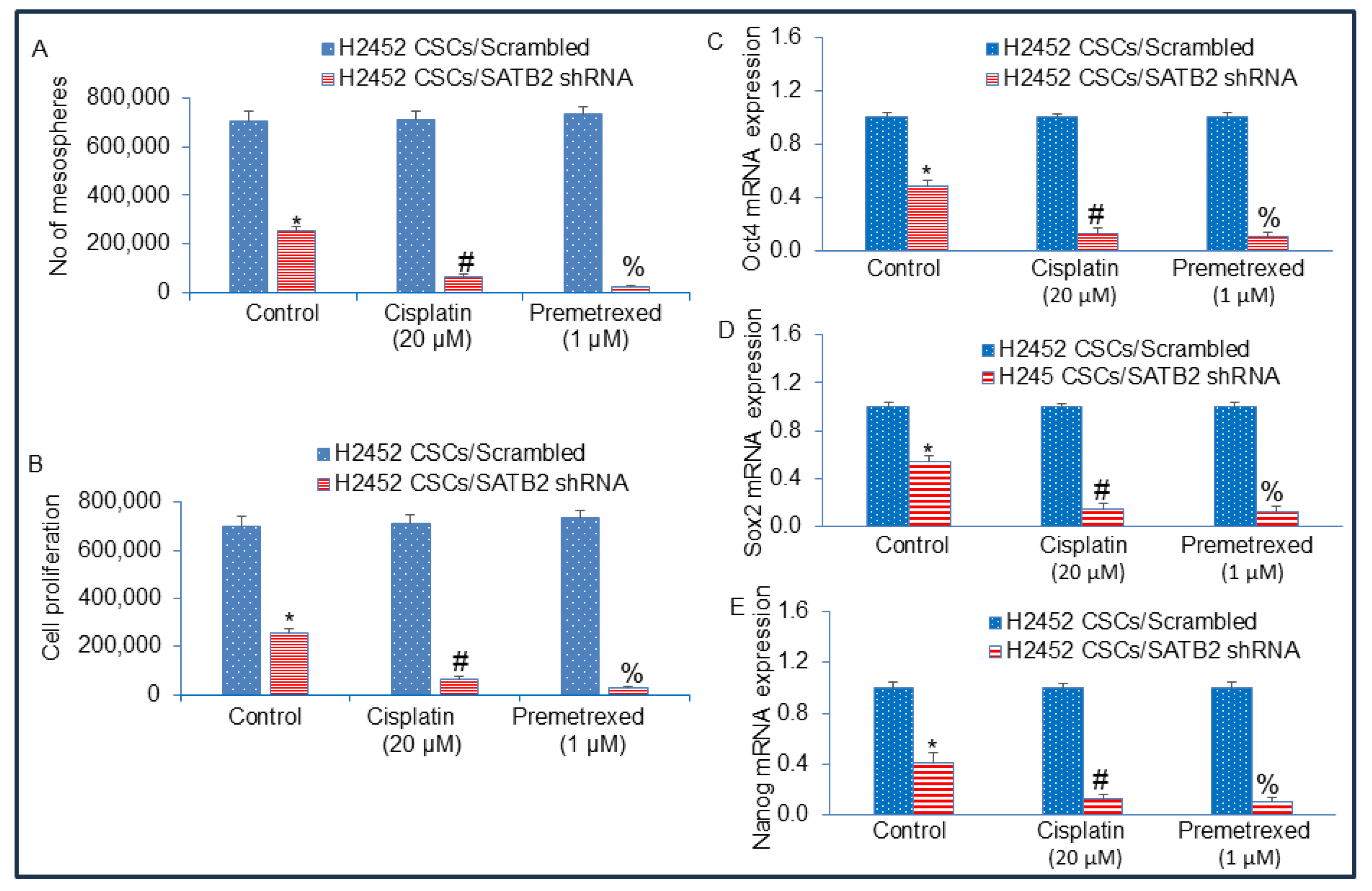

Figure 8.

Inhibition of SATB2 expression in H2452 CSCs reverses drug-resistance to cisplatin and pemetrexed. (A), H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. At the end of the incubation period, the numbers of mesospheres were counted. (B), H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. At the end of the incubation period, mesospheres were collected and dissociated with AccutaseTM (Stemcell Technologies). Viable cells were stained with typan blue (Invitrogen) and counted using a Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen). (C), Expression of Oct4. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Oct4 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (D), Expression of Sox2. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Sox2 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of Nanog. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Nanog expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Inhibition of SATB2 expression in H2452 CSCs reverses drug-resistance to cisplatin and pemetrexed. (A), H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. At the end of the incubation period, the numbers of mesospheres were counted. (B), H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. At the end of the incubation period, mesospheres were collected and dissociated with AccutaseTM (Stemcell Technologies). Viable cells were stained with typan blue (Invitrogen) and counted using a Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen). (C), Expression of Oct4. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Oct4 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (D), Expression of Sox2. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Sox2 expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05). (E), Expression of Nanog. H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells were grown in an ultra-low attachment plate containing well-defined stem cell medium, and treated with or without Cisplatin (20 µM) or Premetrexed (1 μM) for 3 weeks. RNA was isolated from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled and H2452 CSCs/SATB2 shRNA cells. qRT-PCR was performed to measure Nanog expression. * = significantly different from H2452 CSCs/Scrambled group (P < 0.05).