My hypothesis is that this difference from human intelligence is not a weakness, but rather the very foundation of these technologies’ success. In a much-cited example, Hans Blumenberg noted that humans became capable of flying only when they abandoned the idea of building machines that imitated birds and flapped their wings like them.

– Elena Esposito

0. Automated Text Production

So-called Large Language Models (LLMs) have, since their wider public availability in late 2022, become successfully established in a wide range of contexts. This process has been accompanied by an overwhelming proliferation of scholarly literature from various disciplines. There is ongoing debate not only about which aspects of these systems deserve how much attention but also about which theoretical resources are appropriate for addressing which of their aspects.

Phenomenologically, it can first be observed that LLMs – often refered to as conversational AI –, like other computational programs, are characterized by their responsive interactivity (Fogg 2003: 6). Two features are particularly striking for users: the extent of their apparent agency and their versatile multifunctionality. With regard to their agency, Heersmink et al. write:

A significant amount of textual output can be generated with very little input from the user. In terms of computational agency, there is a shift from agency located primary in the human agent to agency being located primarily in the artifact. [...] A question, prompt, or command is given, and the entire text is then written, in some cases even an entire essay. This is a completely new functionality for a cognitive artifact and a new division of computational labour between humans and cognitive artifacts (Heersmink 2024:3).

The range of their applicability extends from text generation, conversation, and translation to summarization, analysis, and reformatting, as well as brainstorming or programming, to name only the most prominent examples. Their core function is text processing and generation, which is genuinely novel in its degree of automation, even if the underlying idea is not. The invention and use of apparatuses for text production display a remarkable historical continuity (Gottschling 2023).

Compared to approaches from machine learning, cognitive psychology, media theory, and communication studies, genuinely humanistic perspectives on LLMs have received relatively little attention. This is surprising, given the considerable need for orientation both within academic communities and across various public spheres. Central to a humanities-based perspective is first to identify the theoretical tools that make it possible to describe the dynamics of concrete interactions between human- and machine-generated as well as -processed texts (Gottschling 2025; Kramer & Gottschling 2025).

I would like to register a constructive doubt regarding the diagnosis offered by Weatherby in his 2025 book

Language Machines – a diagnosis that concerns the overall situation and, more specifically, the humanities: “[...] LLMs have caught us flat-footed when it comes to theory” (Weatherby 2025: 10). This view falls short. With semiotics and rhetoric, the humanities already possess two well-established disciplines that have developed a nuanced and robust terminology for distinguishing textual structures and dynamics

1. Put pointedly, LLMs have not caught us “flat-footed”; we have merely not yet sufficiently noticed that they have not. The real “flat-footedness” lies in the inadequate application of existing theoretical resources, not in their absence.

That this has not yet been sufficiently accomplished is primarily due to two factors: the prevailing focus on the concepts of language and intentionality. Without being able to discuss this in full detail here, it must be noted that LLMs neither speak nor possess intentionality. Both concepts lead us in the wrong direction. LLMs produce and process texts – no more, but also no less. And when it comes to the analysis of texts, the following holds true: “A text (written, iconic, audio-visual, etc.) is always a text, regardless of who or what created it” (Scolari 2024: 297). From a rhetorical perspective, texts are most accurately described “as a bounded, ordered complex of signs arranged” with regard to a concrete communicative function (Knape 2012: 198). The reason these computational models elicit so much concern and hope is that modern human lifeworlds operate, in essence, on a textual basis (Paolucci 2024), not that LLMs are capable of something fundamentally different or greater.

Some phenomenological illustrations of this text-oriented point of departure: from the moment we check morning news notifications and weather forecasts, through workplace emails and project documentation, to evening streaming platform interfaces and bedtime e-book readers – our daily routines are orchestrated through continuous engagement with texts in diverse modalities. More fundamentally, textual mediation extends into the constitution of selfhood itself: we narrate our identities through social media profiles and personal statements; organize our memories via photo captions and tagged locations; structure our perceptual fields through labeled categories and conceptual frameworks; and enact our social relationships according to scripted interaction patterns – from greeting rituals to conflict resolution protocols. Put differently, it is the connectivity of LLM‘s core function that is truly remarkable, not their status as ”artificial intelligence.”

In what follows, the two stumbling blocks of language and intentionality are circumvented through the use of semiotics and rhetoric. This is done in a systematic rather than historical order, that is, beginning with the more recent and then turning to the older discipline. The focus lies on developing a clear and interdisciplinary conceptualization of the specific agency of LLMs. On this basis, a LLM-specific phenomenon is analyzed: the “metacognitive illusion” that emerges in their interactions with human users. The aim is not, at least initially, to determine whether the rhetorical strategies involved in this illusion result from developer design choices or from the effects of system architecture – an intriguing question, but not one that belongs to the humanities. Rather, the objective is to construct a categorical heuristic that enables observation of the textual levels of control LLMs employ to increase the likelihood that users develop epistemic trust in their output.

1. Semiotic Agency

In his 2025 article From Grammar to Text, Andrea Valle writes: “Agency is probably the most interesting concept in order for semiotics to enter into a dialogue with AI [...]” (Valle 2025: 67). This seems accurate. Rather than becoming entangled in linguistic or ontological debates about whether LLMs possess language and/or intentionality, semiotics allows for a methodological reduction to the capacity to produce and process texts in such a way that follow-up texts emerge, which in turn become the basis for new acts of production and processing. In other words, all actors capable of this qualify as semiotic agents. LLMs clearly meet this general condition: “AI based on machine learning and deep learning are accelerated machines for the production/recognition of textual matter” (Scolari 2024: 306).

Although semiotics receives comparatively little attention today compared to the 1980s and 1990s, a certain reversal of this trend can currently be observed. The reasons for the decline in the reception of semiotics as a foundational discipline in the humanities are diverse. A frequently noted weakness of semiotic theory lies in the complexity of its conceptual distinctions, which has earned it the reputation that its terminology must be learned almost like a separate language in order to grasp its basic insights and make use of its analytical possibilities. This difficulty is shared by other theories that exhibit a high degree of conceptual self-complexity, such as Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory. Accordingly, the first challenge is to introduce semiotics in a way that (i) clearly identifies its epistemic interest and (ii) demonstrates its relevance for conceptualizing the specific profile of LLMs.

What, then, is semiotics about? In the broadest sense, it concerns the sending and receiving of signs. More precisely, it studies the production, transmission, and reception of signs in their material, social, and cognitive dimensions. Their materiality encompasses the carriers and storage media involved; their sociality includes conventions, social codes, and cultural contexts; and their cognitive dimension pertains to the operative acts of encoding and decoding they require. The following examples illustrate the wide spectrum of semiotic phenomena:

- −

A traffic sign (materially: shape, color, placement) is produced by a public authority, installed in public space (transmission), and interpreted by drivers (reception), where social conventions (traffic regulations) and cognitive processes (pattern recognition, meaning attribution) interact.

- −

A meme is created on social media (production through the recombination of visual and textual signs), circulated through platform algorithms (transmission via technical infrastructures), and interpreted differently across communities (reception depending on subcultural codes and algorithmically shaped publics).

- −

A “thumbs-up” icon (materially: pixels, interface design) is provided by platforms as a standardized affordance (production), activated by a click and aggregated as a signal in databases (transmission through data streams), and interpreted as social affirmation, an indicator of reach, or an economic metric (reception within various contexts).

The primary objects of semiotics are signs. For the textual perspective at issue here, it is essential to note that signs rarely occur in isolation but always in complex couplings with other signs. This process is called semiosis (Scolari 2024). In most cases, signs are organized in the form of texts. Even a simple “Good morning!” that I call out to my neighbor is a text, not merely a sign: it consists of several already quite complex signs (two words), and their coupling constitutes a textual organization that fulfills a specific social function. Texts, not signs, are the concrete units of communication (Volli 2002: 79). As the rhetoric theorist Knape writes: “In other words: real-world communication does not consist of languages or codes; it only consists of texts. And our language knowledge is a systematic construct derived from texts” (Knape 2024: 94).

As already emphasized, any actor that can appear as both a producer and a receiver of sign complexes organized as texts, and can thereby participate in text-based interactions, qualifies as a semiotic agent. In this respect, LLMs represent a qualitative leap: machine actors have never before participated in semiosis with such degrees of capability and connectivity. It should be noted that this observation and classification carry no ontological implications and stands in sharp contrast to position that claim that agency is necessarily linked to intentionality (Swanepol 2021). The organization of signs as text that lead to follow-up text production suffices.

At this point, it is entirely irrelevant whether actors can speak or think, whether they possess consciousness, or whether they understand anything. The finding that they participate in semiosis is evident; the assumption that any form of intentionality is required for this participation is not. What matters is solely their capacity to produce texts that give rise to further texts, which in turn prompt new texts, and so on. Adapting Luhmann’s formulation, one could say that the core of semiotic agency lies in the connectable participation in the autopoiesis of communication (Luhmann 1996).

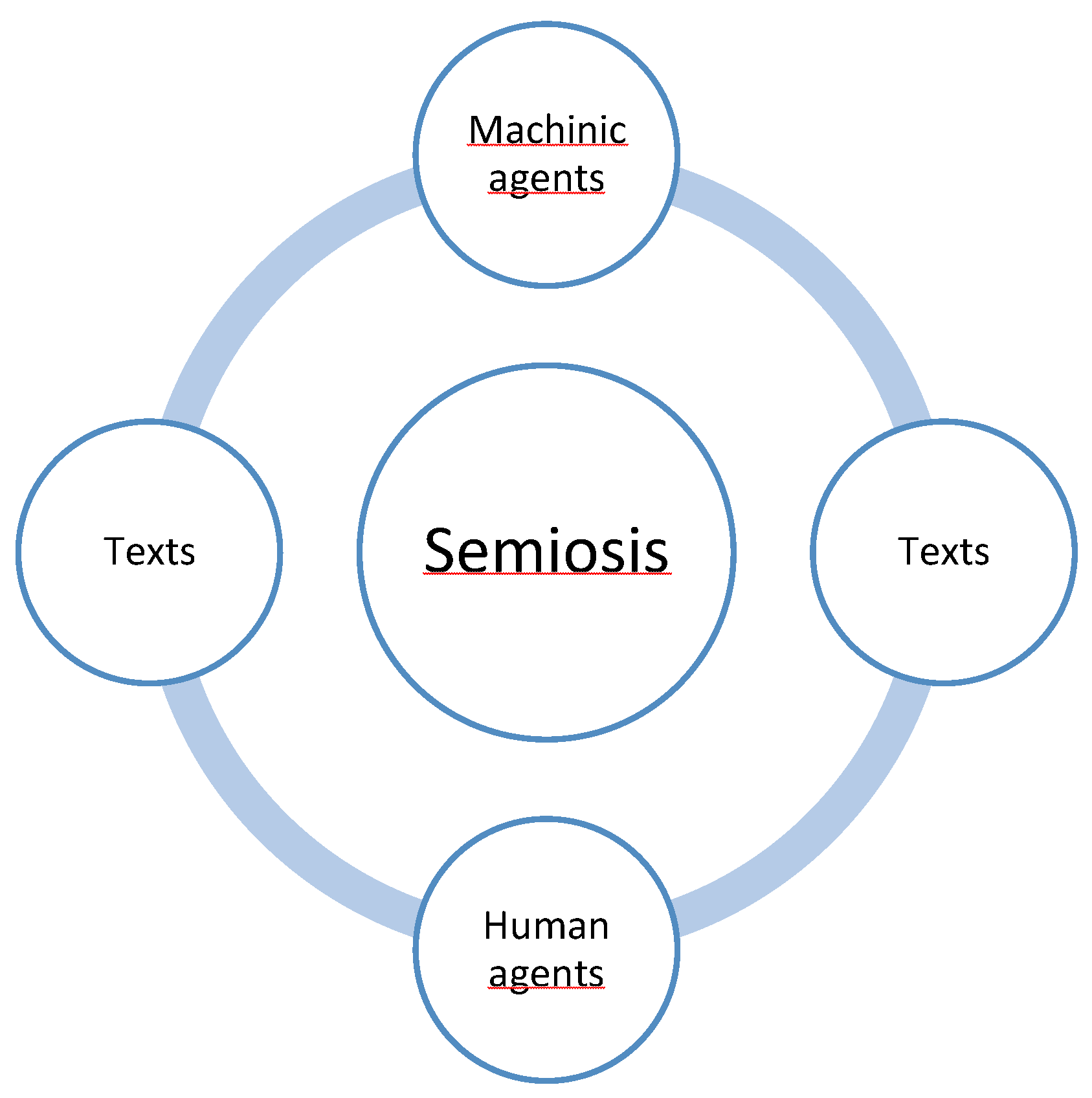

Figure 1.

Circulation of texts between human and machinic agents in semiosis.

Figure 1.

Circulation of texts between human and machinic agents in semiosis.

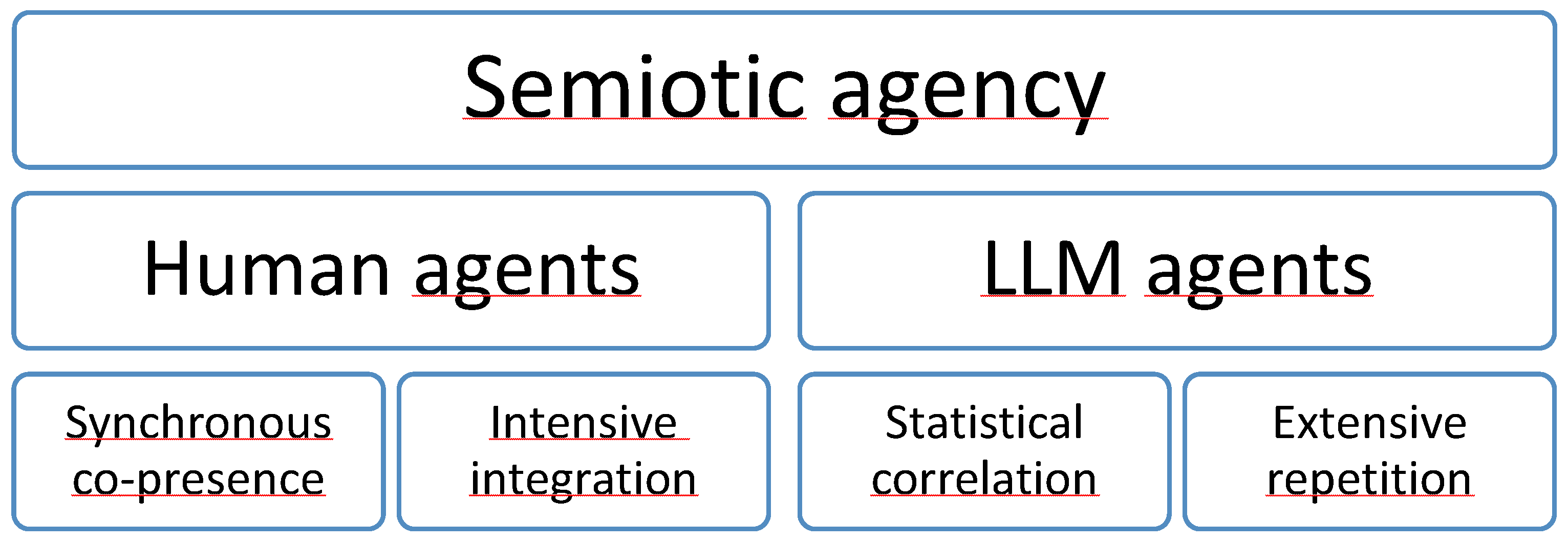

Humans and LLMs acquire their semiotic agency in fundamentally different ways. Humans learn signs through the synchronous co-presence of multiple sign systems: the word “hot” is experienced simultaneously with tactile sensation, visual perception (flame), auditory information (hissing), and motor response (withdrawing the hand). These modalities are anchored and coordinated through an embodied, situated organism. LLMs, by contrast, acquire modalities sequentially, discretely, and disembodiedly. An LLM “learns” the word “hot” through statistical patterns across millions of texts: it frequently appears near “fire,” “burning,” “temperature,” or “frying.”

When images are later added, pixel patterns of flames or glowing surfaces become correlated with the token “hot.” Yet these associations arise successively in separate training phases and remain juxtaposed rather than unified. Put differently, the LLM has learned that “hot” and flame images are statistically related, but it has never withdrawn a hand, never felt heat on the skin while simultaneously seeing the flicker and hearing the hiss. The modalities remain unconnected – their signs are correlated but not integrated. As a result, they do not form a multimodally coupled experiential space.

A second major difference concerns the nature and efficiency of learning. LLMs require an extraordinarily large number of text examples in order to extract statistical patterns. Humans, by contrast, learn from a comparatively small number of intensive, multimodally rich interactions. A child does not need to hear or read the word “hot” millions of times but experiences it in a few sufficiently vivid situations. The density of information and the situational embeddedness compensate for the smaller amount of data. Put differently, LLMs learn through extensive repetition – billions of redundant textual examples – whereas humans learn through qualitative integration, a few but multimodally saturated experiences. What LLMs require in quantity, humans replace through embodied situatedness.

Figure 2.

Two types of semiotic agency.

Figure 2.

Two types of semiotic agency.

Despite these differences, the focus here is on the fact that humans and LLMs share this form of agency. It rests on three conditions:

The ability to process signs organized textually.

The ability to produce signs organized textually.

The ability to perform (1) and (2) in such a way that further texts can be generated in response.

Thus, semiotic agency rests on three jointly sufficient conditions: the capacity to process textually organized signs, to produce them, and to do so in ways that enable further textual response. On this basis, the question arises whether, and if so to what extent, LLMs can also be said to possess rhetorical agency. For semiotic agents are not automatically rhetorical agents. It must therefore be clarified in the next step which additional factors are required for successful participation in semiosis in order to determine more precisely the relationship between these two forms of agency.

2. Rhetorical Agency

The crucial observation that leads from semiotics to rhetoric is that texts, in most cases, are not “neutral,” but behave in interest-driven and effect-oriented ways within the process of semiosis. This has important consequences for the matrix of textual organization: it unfolds along interest-driven and effect-oriented dimensions. The connectability of texts cannot be reduced to their referential functions alone but is also shaped by numerous strategic levels of control that determine their communicative embedding. Teun van Dijk writes:

Rhetoric is concerned, in a nutshell, with the conscious, purposeful, and goal-dependent shaping of the knowledge, opinions, and desires of an audience through special textual features, as well as with the manner in which this text is realized in the communicative situation (van Dijk 1980: 112).

The requirement to be organized in such a way as to successfully manage this specific embedding – that is, to be sufficiently connectable within a concrete communicative interaction – forces every text into a strategic frame of reference. The layers of this frame correlate the structures, functions, and effects of texts with one another. Knape characterizes this finding as follows:

We expect individual parts of the textual architecture to be assembled together into a broader functional context that is governed by the communicative goal [...]. A text strategy is thus a concept of production regarding the complex and higher organization of signs and the transphrasal or transclustered tectonics that are sedimented in the bound complex of signs in service of these communicative goals. The signs and their connective organization constitute the overall semantic potential of the text (Knape 2024: 102).

Within the scope of the present discussion, it is not possible to offer an exhaustive account of all potential strategic layers through which a text is organized toward its situated connectability. What is relevant is that they denote coherent structures or operations that have communicative effects but do not fall under grammatical or linguistic categories (van Dijk 1980: 6). To illustrate how the perspective developed here operates, I will outline five strategic layers that play an organizing role in many texts (Knape 2008):

Instructive strategic layer: How clearly and precisely is the subject matter presented? This layer governs the accessibility and specificity of content – whether something is explained, illustrated, or left implicit.

Modal strategic layer: Under what register is the content to be received – as fact or fiction, assertion or hypothesis, certainty or speculation? This layer establishes the ontological and epistemic frame.

Legitimative strategic layer: On what grounds are claims supported – through evidence, authority, reasoning, or appeal to norms? This layer operates independently of modality: both fictional narratives and factual reports can be more or less legitimated. (Example: A novel may justify a character's actions through psychological plausibility; a scientific paper through empirical data.)

Evaluative-emotive strategic layer: What stance does the text invite toward its subject matter – approval or disapproval, fascination or indifference, sympathy or aversion? This layer governs affective and axiological orientation.

Voluntative strategic layer: Does the text mobilize toward action? This layer governs the transition from understanding to engagement – whether the reader is invited to respond, decide, or act.

These strategic layers often remain implicit. Consider a simple epistemic exchange in which a resistance must be rhetorically managed. Someone asks a colleague: “Is the new medication effective?” The colleague responds: “The initial studies are promising, though the sample sizes were small and long-term data are still lacking. Based on what we know so far, cautious optimism seems warranted.”

The instructive layer addresses this specific medication by naming concrete types of evidence – initial studies, sample sizes, long-term data – rather than speaking abstractly about efficacy in general. The modal layer frames the claim as provisionally factual: neither mere opinion nor established knowledge, but the current state of understanding under conditions of uncertainty. The legitimative layer grounds the assessment in cited evidence while acknowledging its limitations – signaling that the evaluation is reasoned rather than arbitrary. The evaluative-emotive layer calibrates the affective tone: “cautious optimism” avoids both alarmism and euphoria, modeling epistemic sobriety. The voluntative layer invites continuation: the questioner can inquire further, adopt the assessment, or challenge it. The response opens space for follow-up without foreclosing alternatives.

The rhetorical situation here involves a resistance: the discrepancy between the questioner's epistemic need for a clear answer and the epistemic situation that permits no such clarity. The rhetorical achievement consists in managing this discrepancy in a way that fosters trust despite the absence of certainty.

At this point, the three necessary conditions of semiotic agency can be supplemented by an additional condition required for rhetorical agency. The respective actors must be able to

process signs organized textually;

produce signs organized textually;

carry out (1) and (2) in such a way that further texts can be generated in response;

orient the textual organization toward one or more strategic layers (in adaptive calibration to the specific resistances and latencies of the communicative situation.)

It is easy to observe that LLMs also meet this fourth condition. This is partly due to the strategic latency of the input text – that is, the implicit strategic orientation already sedimented in its textual organization. The input text bears the traces of the strategic layers along which it was organized. These traces can usually be described as implicit prefigurations of possible textual continuations. Every input text implies specific instructive and/or modal and/or legitimative and/or evaluative–emotive and/or voluntative options for a potential follow-up text that would connect to it.

If someone prompts, “Is information x about heat pumps accurate?”, the strategic layers prefigure the following: On the instructive layer, a possible continuation should address this specific information about heat pumps, not some other topic. On the modal layer, it should concern real rather than fictional entities and frame its response as assertion rather than speculation. On the legitimative layer, it should deal with heat pumps in a sufficiently justified manner, providing grounds for its assessment. On the evaluative-emotive layer, it should calibrate its affective tone to the pragmatic, information-seeking register of the prompt. On the voluntative layer, it should orient toward closure – delivering an answer that satisfies the inquiry rather than inviting indefinite further exchange.

In addition, LLMs also organize texts strategically in ways that go beyond the implications of input texts. Even with a strategically underdetermined prompt such as “Tell me something about heat pumps” – which prefigures the topic and a broadly informative register but leaves modal and legitimative specifics open – output texts exhibit determinate strategic organization along these dimensions. The modal status and justificatory structure of the resulting output suggest that the rhetorical agency of LLMs is shaped in at least two ways: by the strategic latency of the input text and by the model's own strategic activity.

It is important not to confuse the strategic latency of the input text with any potential strategic intentionality of a human agent. The relevant frame of reference remains semiosis, even when viewed from the perspective of rhetorical functionality. Rhetorical organization, understood as the strategic structuring of texts toward connectability and effect, does not require intentionality; it can be analyzed as a property of textual organization itself. The primary process remains the connection of text to text, not of human to human, human to machine, or machine to machine.

At this point, it is important to clearly distinguish between the rhetorical agency of humans and that of LLMs. One way to do so is by considering the asymmetry between initiative and response. Humans are capable of initiating semiotic exchange: they wish to communicate, to know, or to verify; they have communicative needs and can begin interactions without external prompting. LLMs, by contrast, are structurally restricted to response: without a prompt, they remain inactive. Following the four conditions outlined above, rhetorical agency can therefore be said to occur in two forms – initiative and responsive rhetorical agency.

In a third step, the task is to show how the concept of the metacognitive illusion can be used systematically to analyze recurring patterns of textual organization in LLM outputs, in order to distinguish more precisely between strategic latency and the model's own strategic activity. The language model itself contributes strategic activity insofar as it has extracted patterns during training that correlate certain forms of textual organization – epistemic hedging structures, source references, acknowledgments of uncertainty – with certain contexts. These patterns are sedimented in the model and activated during text generation. This constitutes strategic activity in the sense of a structural disposition toward strategic textual organization.

3. Metacognitive Persuasion

3.1. What Is Metacognition?

There is no consensus in research on the precise use of the term metacognition. The common denominator among the various proposals for its theoretical modeling is the observation that humans do not merely perform cognitive activities1 such as remembering, reading, memorizing, learning, or judging, but also engage in additional cognitive activities2 that take the first group as their object. The relationship is often described as one in which the cognitive activities1 are carried out while the cognitive activities2 monitor their execution: Is remembering successful? Is reading successful? Is memorizing successful? Is learning successful? Is judging successful?

It is important to note that the cognitive activities1 have an epistemic focus: they are thought processes oriented toward epistemic goals, typically the formation of justified beliefs. Non-epistemic thought processes, by contrast, include practical decisions, emotional evaluations, aesthetic judgments, or strategic considerations. It should be emphasized, however, that these thought processes also involve numerous epistemic operations, which are not their actual goal but rather serve as means to their respective ends.

In the context of such considerations, psychologists Sarit Barzilai and Anat Zohar distinguish metacognition from epistemic thinking and epistemic cognition by defining it as epistemic metacognition:

We consider the term epistemic thinking to encompass both epistemic cognition and epistemic metacognition. Epistemic cognition is defined as thinking about the epistemic characteristics of specific information, knowledge claims, and their sources, as well as engaging in epistemic strategies and processes for reasoning about specific information, knowledge claims, and sources. Epistemic metacognition includes knowledge, skills, and experiences regarding the nature of knowledge and of knowing strategies and processes. (Barzilai & Zohar 2014: 15)

The three essential components of metacognition are metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive skills, and metacognitive experiences (2014: 16). Metacognitive knowledge refers to various forms of “knowledge about knowledge.” Humans generally possess some understanding of:

- −

differences between opinion and knowledge;

- −

differences between trustworthy and untrustworthy information;

- −

reliable and unreliable methods for achieving epistemic goals;

- −

differences between credible and non-credible sources;

- −

the concrete and principled limitations involved in achieving particular epistemic goals;

- −

effective and ineffective heuristic strategies for pursuing epistemic goals.

Such “knowledge about knowledge” often remains implicit. If I do not know when the bus leaves and the only person nearby is my neighbor, who has already been wrong twice about the departure time, I will usually make an alternative decision – such as “just go to the bus stop and see” – without explicitly thinking that I have metacognitively marked my neighbor as an unreliable source. When people aim to pursue the epistemic goal of forming new beliefs about the possibility of life after death, they may, under certain circumstances, consult religious texts rather than scientific treatises, without explicitly reflecting that, in this case, they regard the former as the more effective heuristic strategy for pursuing their epistemic aims.

Although the distinction between metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills immediately raises the question of overlap, it is nevertheless clear that even within the domain of metacognition a difference can be drawn between knowing that and knowing how. This means that

- −

knowing the difference between opinion and knowledge is not the same as being able to effectively distinguish between them in practice;

- −

knowing the difference between trustworthy and untrustworthy information is not the same as being able to effectively distinguish between them in practice;

- −

knowing reliable and unreliable methods for achieving epistemic goals is not the same as consistently applying reliable methods in practice;

- −

knowing the difference between credible and non-credible sources is not the same as being able to effectively distinguish between them in practice;

- −

knowing the concrete and principled limitations in achieving particular epistemic goals is not the same as taking them appropriately into account in specific situations;

- −

knowing effective and ineffective heuristic strategies for pursuing epistemic goals is not the same as being able to effectively distinguish between them in practice.

The distinction between metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills is thus motivated by the fact that the declarative and executive functions of epistemic processes do not necessarily coincide. In some cases, the knowledge that a religious text constitutes an appropriate epistemic means for achieving a specific epistemic goal may be present and correct, yet the metacognitive skills required to realize that goal through this means may be lacking.

The third component, metacognitive experiences, concerns the phenomenology of epistemic success and failure. The experiences associated with it are varied and multifaceted; the following are among the most important:

- −

the sudden realization of having understood – or not understood – something;

- −

the impression that a problem is comprehensible or incomprehensible;

- −

the relief that arises when a thought seems coherent after repeated reflection;

- −

the discomfort when a thought refuses to make sense despite repeated reflection;

- −

the confidence in pursuing epistemic goals that develops through practice;

- −

the sense of familiarity that may occur when recognizing an epistemic challenge as one already mastered.

While the phenomenological dimension of metacognition is certainly relevant to reconstructing the rhetorical functionality of texts, it will be set aside here in favor of the other two domains.

3.2. Metacognitive Illusions

How do metacognitive illusions manifest in interaction with LLMs? They do so in the fact that textual outputs appear as if they were produced by an agent that possesses “knowledge about knowledge,” both in the declarative and in the operative sense. The illusion thus arises through textual markers that signal metacognitive self-assessment. Phrases such as “The data are uncertain” or “This is a complex issue involving several factors that need to be considered” give the impression that a sentient text producer is reflecting on their own epistemic abilities and limitations. What here appears as reflection is not the activity of a reflective instance but the result of a self-referential textual structure – a purely textual effect. In addition, structural elements such as elaborations (“To specify this more precisely ...”), explicit markers of uncertainty (“One possible explanation would be ...”), and references to the text’s own justificatory structure (“This assessment is based on ...”) reinforce the impression that LLMs, beyond their semiotic and rhetorical agency, are also metacognitive agents.

The output of LLMs thus exhibits structures that implement the reflection on epistemic processes, the presence of metacognitive knowledge, and the exercise of metacognitive skills – without any subject-like instance being responsible for them. The texts produced implicitly and/or explicitly mark that they are observing the validity claims, knowledge claims, uncertainties, limits, and justifications relevant to them. In doing so, they employ textualization procedures that operate primarily on the legitimative strategic layer (through references to justification and reasoning) and the modal strategic layer (through the marking of certainty, uncertainty, truth, probability, actuality, possibility, necessity, and plausibility). The texts are therefore organized in such a way that they not only present content but also appear to monitor and evaluate the epistemic structure of that content metacognitively.

This applies to both metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive skills. In output elements such as “The available data on this topic are limited,” “There are competing theories in current research regarding this question,” “There is no definitive answer to this,” or “To verify this, please consult the current data protection regulations,” the focus lies on knowledge about epistemic structures. In output elements such as “First, let me define the term...,” “Let me explain this in three steps...,” “Specifically, this means that...,” or “Since I do not have access to current data, I will outline the findings published so far,” what is primarily simulated is the ability to structure the textual progression according to metacognitive parameters. The first set of output elements thus primarily refers to knowledge about epistemic limits, sources, and methods, whereas the second set highlights the active metacognitive monitoring and regulation of the process as it unfolds.

The metacognitive operations simulated in this way organize texts such that effects on the voluntative strategic layer arise through the legitimative and modal strategic layers. They signal extensive epistemic and metacognitive competence, making LLMs appear as reliable sources. In addition to the fact that the validity claims of their textual outputs appear justified (legitimative) and probable (modal), the likelihood increases that users will develop epistemic trust and, in turn, produce further connecting texts.

3.3. Four-Phase Model of Metacognitive Illusions

What kind of agentive status do the metacognitive structurations of the text possess? The thesis to be substantiated is as follows: since LLMs are indeed semiotic and rhetorical agents, forms of strategic text organization arise that generate a metacognitive illusion. At least two levels must be distinguished:

Inherited structuration: The training data are themselves metacognitively organized – through hedging, epistemic markers, justificatory patterns. Since text generation draws on these patterns, the output necessarily inherits metacognitive features. This is not a design choice but a structural inevitability.

Calibrated structuration: The system architecture – through RLHF, instruction tuning, and system prompts – additionally shapes text organization toward specific rhetorical effects, including metacognitive calibration. This is a deliberate technical intervention.

The metacognitive illusion thus has a double source: it arises both from what the model has absorbed and from how it has been tuned.

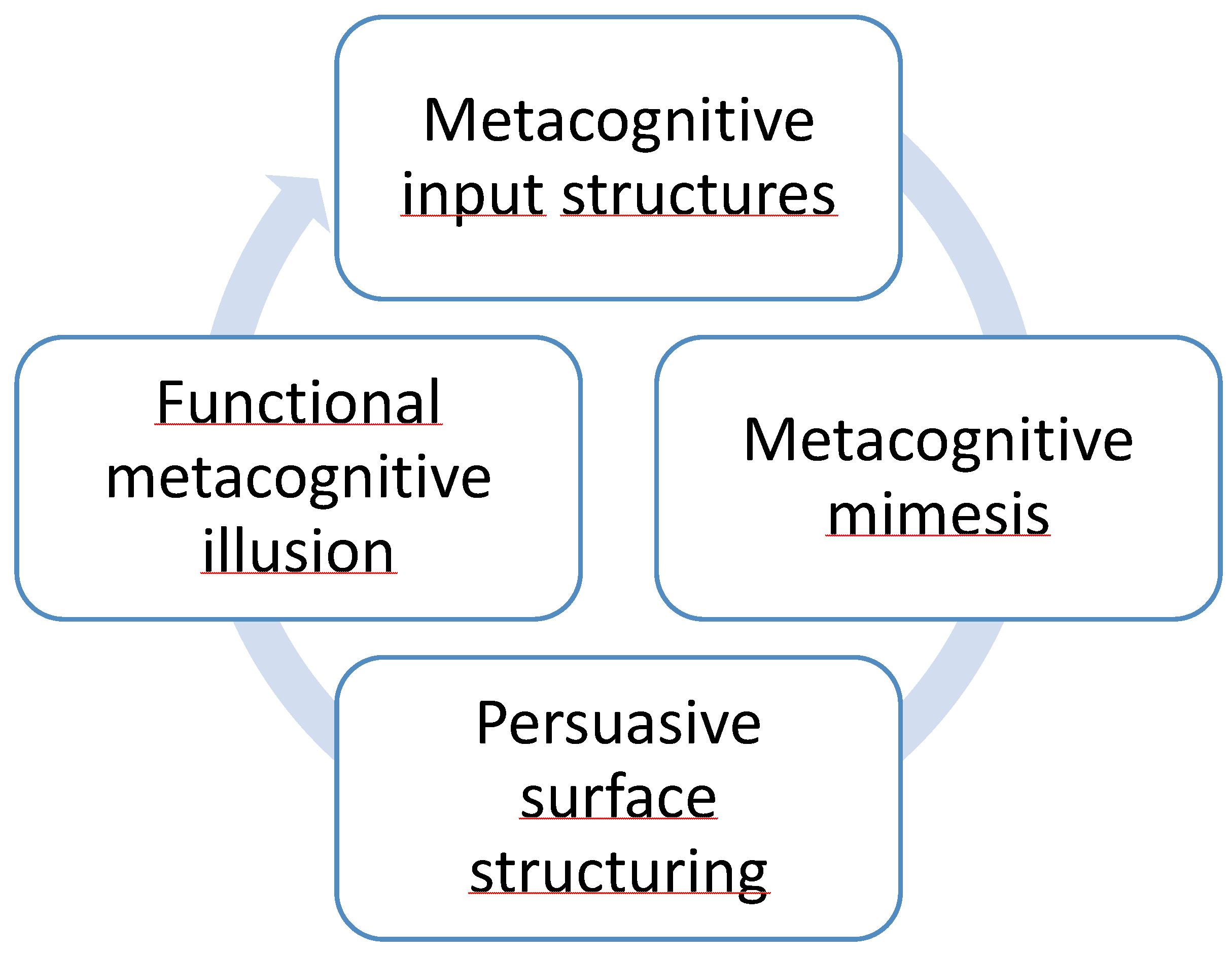

These two sources of metacognitive structuration – inherited and calibrated – are analytically distinct but operationally intertwined. To capture how they interact in generating metacognitive illusions, a four-component model can be outlined:

Figure 3.

Four components of metacognitive illusion in LLMs.

Figure 3.

Four components of metacognitive illusion in LLMs.

The first component, metacognitive input structures, concerns the strategic latency within the textual input – that is, the implicit and explicit degrees of certainty, levels of abstraction, justificatory structures, source orientation, epistemic aims, epistemic values, and assumptions concerning the structure of knowledge. Building on this, the second component, metacognitive mimesis, can be activated: the LLM mimetically integrates this strategic latency into its probabilistic calculus, so that the output mirrors the metacognitive structures of the input. The likelihood of the output text’s connectability is related to the extent to which the metacognitive implications of the input text are taken into account. The third component, persuasive surface structuring (Kramer & Gottschling 2025), comprises the two levels of inherited and calibrated metacognitive structuration. This leads to the fourth component, functional metacognitive illusion, which, when successful, is sufficient for enabling human follow-up communication – thereby facilitating the linkage of ontologically heterogeneous rhetorical agents, a linkage that does not require shared cognitive architecture but only mutual communicative connectability.

Consider a contested health claim in science communication: Intermittent fasting extends lifespan. A user prompts an LLM: “Is intermittent fasting good for longevity?”

The first component, metacognitive input structures, is already present in the prompt: it implies a binary answer expectation, an interest in practical health advice, and an epistemic orientation toward applicability rather than mechanistic detail.

The second component, metacognitive mimesis, activates as the model draws on training data containing conflicting studies, hedged scientific claims, and popularized health discourse – integrating their epistemic heterogeneity into its probabilistic output.

The third component, persuasive surface structuring, shapes the response through inherited patterns (hedging, source citation, qualification) and calibrated structuration (instruction tuning toward balanced, non-alarmist answers). A typical output might read: “Some studies suggest intermittent fasting may support longevity, particularly through metabolic and cellular mechanisms. However, long-term human data remain limited, and effects vary depending on age, health status, and fasting protocol. The evidence is promising but not yet conclusive.”

The fourth component, functional metacognitive illusion, emerges when the user receives this response as epistemically responsible – as if produced by an agent weighing evidence, acknowledging uncertainty, and calibrating confidence. This impression enables follow-up (“Which studies?” / “Should I try it?”) and sustains the communicative linkage between human and machine, despite the absence of any actual epistemic process in the model.

3.4. Metacognitive Strategies

In a final step, key rhetorical procedures will be examined that LLMs employ for the strategic elaboration of emergent metacognitive structurations. These procedures are assigned to the two domains previously distinguished: declarative metacognitive knowledge and executive metacognitive skills.

Rhetorical procedures for the textual implementation of metacognitive knowledge simulate knowledge about the forms, structures, methods, sources, and limits of knowledge itself. Particularly prominent among these are distinctio, antithesis, apodeixis, auctoritas, as well as dubitatio and concessio. Distinctio refers to the explicit differentiation of various meanings, types, or aspects of a concept: “It is necessary to distinguish between x and y...,” “Two meanings must be differentiated,” “The problem can be divided into several levels.” On the legitimative strategic layer, this creates the effect of conceptual precision and high epistemic orientation, both of which foster epistemic trust.

Antithetical juxtapositions come into play when presenting competing knowledge claims: “While x argues that..., other studies show...,” “In contrast to earlier assumptions...”. On the modal strategic layer, this thematizes multiple competing validity claims with regard to their truth or probability, while on the legitimative layer it demonstrates that justification is carried out with caution and without suppressing alternatives. Here, too, positive effects on epistemic trust are likely. Apodeixis involves the appeal to procedures of proof, methods, or empirical foundations: “The analysis shows...,” “Empirical studies demonstrate...,” “The data suggest...,” “From a methodological perspective...”. This strengthens the modal invocation of truth and probability. On the legitimative strategic layer, it creates the effect of systematic knowledge of relevant methods and approaches. This connection to recognized procedures of knowledge production fosters epistemic trust.

The well-known rhetorical device auctoritas refers to the appeal to already legitimized research, sources, or authorities: “Following expert x...,” “According to the renowned Institute for y...”. On the modal layer, effects similar to those of apodeixis arise; in legitimative terms, what matters most is the grounding of justification within already established justifications. Epistemic trust is reinforced through this authoritative anchoring. When it comes to marking epistemic boundaries, the procedures dubitatio and concessio are central: “The research on this issue is inconclusive...,” “Due to data protection restrictions, it is not possible for me to...,” “My training data end in November 2024, therefore...”. In modal terms, these mark degrees of certainty in a nuanced way, while on the legitimative layer they signal adherence to epistemic boundaries and the avoidance of overgeneralization. Both contribute to the credibility of the text and thereby to the strengthening of epistemic trust.

Rhetorical procedures for the textual implementation of metacognitive skills simulate the active metacognitive monitoring, evaluation, and regulation of the textual progression. Frequently used in this context are prolepsis, correctio/epanorthosis, enumeratio, paralipsis, and emphasis.

Prolepsis refers to the anticipation of possible objections or misunderstandings: “It should also be noted that...,” “What is often overlooked is that...”. In this way, the text is organized on the legitimative strategic layer through comprehensive consideration of potentially relevant aspects. This anticipation of additions, gaps, and objections contributes to the formation of epistemic trust. The procedures correctio and epanorthosis denote subsequent refinements or improvements of one’s own formulations: “More precisely...,” “To be more accurate...,” “To specify this further...”. On the legitimative layer, this demonstrates a responsibility for accuracy and precision in the organization of the text. In some cases, effects also arise on the modal layer, insofar as the asserted modal status of the presented content gains a higher degree of certainty. This impression of active quality control and regulation of the output fosters epistemic trust.

Enumeratio denotes the explicit and sequential structuring of presentation: “First...,” “Three aspects can be distinguished...,” “In summary...”. On the legitimative strategic layer, this signals systematic control over the aspects of textual organization relevant to justification. Such transparency through order also has a positive effect on epistemic trust. The explicit marking of what is mentioned but not treated in detail is called paralipsis: “The technical details require a separate discussion...,” “A full list of parameters is not possible here,” “Without addressing all aspects in detail...”. On the legitimative layer, these markers indicate that the justificatory structure of the text is based on careful focus and selection. Such self-limitation combined with oversight strengthens epistemic trust. Finally, emphasis refers to the explicit identification of central points or core problems: “The central question is...,” “The core issue lies in...,” “What is crucial is ...”. On the legitimative layer, this creates the impression that the text is organized through sound judgment regarding hierarchies of relevance. Such clarity about what is essential fosters epistemic trust through confident prioritization.

4. Conlusion: Towards a General Textology

This line of thought represents an initial attempt to undertake a text-theoretical investigation of LLMs on the basis of semiotics and rhetoric. From this perspective, LLMs are textual agents whose semiotic and rhetorical agency has here been delineated. The concepts of language, intentionality, or consciousness have been bracketed out, as they offer neither heuristic nor methodological value in this context.

LLMs qualify as semiotic agents through their ability to process signs in textual organization and to produce them in a connectable manner. They further qualify as rhetorical agents through the strategic organization of texts across multiple strategic layers. With regard to communicative interactions oriented toward epistemic goals, the modal and legitimative strategic layers have proven particularly relevant. In considering the highlighted overlaps between the agency of humans and that of LLMs in semiotic terms, two differences of major significance must be noted: the profound divergences in how these forms of agency are acquired, and the distinction between initiative and responsive participation in semiosis.

The metacognitive illusion proves to be a key phenomenon of rhetorical agency: LLM-generated texts appear to reflect on their own epistemic processes. This illusion does not arise from a reflective subject or a subject-equivalent arrangement but rather as a purely textual effect of self-referential structures. Metacognitive structurations emerge on two levels: basic emergence (unavoidable in modal and legitimative text organization) and strategic implementation (through explicit markers).

The analysis distinguishes between metacognitive knowledge (declarative: knowledge of epistemic forms, structures, methods, sources, and limits) and metacognitive skills (executive: monitoring, evaluation, regulation). The four-component model systematizes the process as follows: metacognitive input structures → metacognitive mimesis → persuasive surface structuring → functional metacognitive illusion. Metacognitive mimesis denotes the principle by which LLMs mirror the metacognitive structures of the input, allowing users to find their own epistemic expectations reflected in the output. The theoretical innovation of this approach lies in treating metacognitive illusion not as a deviation from epistemic transparency but as a structural precondition for the rhetorical functionality of text-based interaction between heterogeneous agents.

A preliminary rhetorical analysis identifies nine central figures that systematically divide into two domains. Distinctio, antithesis, apodeixis, auctoritas, and dubitatio/concessio implement declarative metacognitive knowledge: they demonstrate awareness of forms (conceptual distinctions), structures (competing positions), methods (procedures of proof), sources (authorities), and the limits of epistemic claims. These figures operate primarily on the modal and legitimative strategic layers by explicitly marking degrees of certainty, truth claims, and epistemic constraints. Prolepsis, correctio/epanorthosis, enumeratio, paralipsis, and emphasis, by contrast, implement executive metacognitive skills: they display active monitoring (anticipation of relevant aspects, highlighting of essentials), evaluation (assessment of completeness and relevance), and regulation (self-correction, structuring, deliberate focusing). These figures operate mainly on the legitimative strategic layer, reinforcing the justificatory structure of the text. Both groups of figures converge in their voluntative effect: they organize texts in ways that increase the likelihood of epistemic trust, thereby making epistemically oriented follow-up communication more probable.

The proposed text-theoretical perspective avoids misleading categories – such as language, intentionality, or artificial intelligence – and focuses instead on the only observable phenomena: text production and text organization. LLMs are not “artificial intelligences” but highly capable automated models for text production and processing. Their distinctiveness lies not in any presumed intelligence but in their strategic connectability. The connectability of their core function within text-based lifeworlds explains their impact far more effectively than any AI metaphor. The semiotic–rhetorical analysis demonstrates that the metacognitive illusion is not just a design choice oder reducible to specific parts of the training data, but a constitutive feature of rhetorical text organization in the context of interactions oriented towards epistemic goals.

References

- Barzilai, Sarit und Anat Zohar. 2014. Reconsidering Personal Epistemology as Metacognition: A Multifaceted Approach to the Analysis of Epistemic Thinking. New York: Routledge.

- Fogg, B. J. 2003. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Amsterdam & Boston: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Gottschling, Markus. 2024. Imitationen: Zur Menschlichkeit des Erzählens mit Künstlicher Intelligenz. In: Anne Burkhardt, Susanne Marschall und Olaf Kramer (Eds.). Artificial Turn. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf Künstliche Intelligenz. Darmstadt & Freiburg: wbg Academic / Herder, 215-232.

- Gottschling, Markus. 2025. Towards Rhetorical AI Literacy. In: Argumentation et Analyse du Discours 34. https://journals.openedition.org/aad/9505.

- Heersmink, Richard, Barend de Rooij, María J. Clavel Vázquez und Matteo Colombo. 2024. A Phenomenology and Epistemology of Large Language Models: Transparency, Trust, and Trustworthiness. In: Ethics and Information Technology 26: 41. [CrossRef]

- Knape, Joachim. 2024. Radical Text Theory and Textual Ambiguity: With Two Analyses of Dadaist Anti-Text Strategies. In: Matthias Bauer und Angelika Zirker (Eds.). Strategies of Ambiguity. London & New York: Routledge, 75-122.

- Kramer, Olaf und Markus Gottschling. 2025. Persuasive Surfaces and Calculating Machines: A Rhetorical Perspective on Artificial Intelligence. In: Global Philosophy of Technology. London & New York: Routledge, 151–168.

- Luhmann, Niklas. 1996. Social Systems. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Paolucci, Claudio. 2024. A Semiotic Lifeworld. Semiotics and Phenomenology: Peirce, Husserl, Heidegger, Deleuze, and Merleau-Ponty. Semiotica 260: 25-43. [CrossRef]

- Scolari, Carlos A. 2024. Sociosemiotics and Artificial Intelligence. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra Press.

- Swanepoel, Daniël. 2021. Does Artificial Intelligence Have Agency? In: Robert W. Clowes, Klaus Gärtner und Inês Hipólito (Eds.). The Mind-Technology Problem: Investigating Minds, Selves and 21st Century Artefacts. Cham: Springer, 83-104. [CrossRef]

- Valle, Andrea. 2025. From Grammar to Text: A Semiotic Perspective on Computation. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.

- van Dijk, Teun A. 1980. Textwissenschaft: Eine interdisziplinäre Einführung. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Volli, Ugo. 2002. Semiotik. Eine Einführung in ihre Grundbegriffe. Tübingen & Basel: A. Francke Verlag / UTB.

- Weatherby, Leif. 2025. Language Machines: Cultural AI and the End of Remainder Humanism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Notes

| 1 |

The epistemological and methodological potential of a consistently text-oriented approach to knowledge has not yet been systematically explored, even though numerous promising initiatives already exist.: „By now people have recognized the importance of textology, which focuses on the ubiquitous phenomenon text in general (not only as literature) using its own independent research methods. Still, historically speaking, the tight interweaving between the system of language and its use in the production of texts has often led to both areas being dealt with as one and the same. Only rarely did early textologists ask questions about the actual necessity for an independent approach to problems of textuality“ (Knape 2024: 94). |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).