1. Introduction

Recent advancements in large-scale neural network architectures have demonstrated that model design plays a critical role in improving both efficiency and performance. The success of the DeepSeek-V2 model [

1] has particularly drawn attention to the potential of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures, which enable dynamic routing of information through specialized expert networks. This architecture achieved competitive performance compared to models such as ChatGPT, largely due to its sparse activation mechanism and scalable design. Motivated by these findings, exploration of MoE models within the LEMUR neural network dataset [

2,

3], was aiming to investigate whether similar performance gains could be achieved in vision-based tasks. Inspired by recent advancements in the application of large language models (LLMs) across various domains [

4,

5,

6,

7], we aim to integrate these architectures into the LEMUR neural network dataset to provide a flexible and scalable foundation for subsequent LLM fine-tuning within the NNGPT project [

4,

8,

9,

10].

The LEMUR dataset provides a structured collection of neural network models designed for benchmarking and AutoML research. However, most existing models in LEMUR rely on conventional architectures, limiting the exploration of modular and scalable expert-based models. To address this gap, this study focused on integrating Mixture-of-Experts architectures into the LEMUR framework and evaluating their effectiveness on image classification tasks.

The primary goal of this work was to design and implement a series of MoE-based models that could outperform existing models in the LEMUR dataset by at least 2–10% in accuracy. To achieve this, we conducted three experimental stages: (1) developing base MoE models in multiple variants, (2) implementing MoE architectures using AlexNet as expert networks, and (3) designing a heterogeneous MoE configuration that combined AlexNet, AirNext, DenseNet, and BagNet as four diverse experts. These experiments aimed to assess the potential of expert-based modularity for improved performance and adaptability within the LEMUR ecosystem.

2. Related Work

MoE architectures have been increasingly explored in computer vision to improve image classification performance through conditional computation. In these systems, a gating mechanism dynamically selects a subset of expert models to process each input, rather than using a single monolithic model.

2.1. MoE in Convolutional Neural Networks

Early CNN-based MoE models demonstrated that routing inputs to specialized expert branches can yield better performance. Ahmed et al. introduced a tree-structured network of experts trained end-to-end to route inputs based on class clusters, achieving state-of-the-art results on CIFAR-100 [

11]. Similarly, Gross et al. proposed a hard MoE system that routes images to CNN experts trained on clustered data subsets [

12]. Other works like CondConv [

13] condition convolutional filters on input data using learned gating functions, effectively implementing MoE behavior at the layer level. Wang et al. expanded ResNet blocks with sparsely activated MoE layers, showing 3–4% improvements on CIFAR-100 without increasing compute cost [

14].

2.2. MoE in Vision Transformers

Vision Transformer-based MoEs (e.g., V-MoE) apply sparse expert selection to transformer MLP blocks. Riquelme et al. showed that V-MoE outperforms dense ViTs on ImageNet at similar compute cost [

15]. Later work [

16,

17] demonstrated that V-MoEs improve adversarial robustness and can scale effectively to detection and segmentation. Soft MoE formulations [

18] also simplify training by avoiding hard routing.

2.3. Heterogeneous MoE Models

Although most MoEs use homogeneous experts for simplicity, a few works explore heterogeneous setups. Abbas and Andreopoulos [

19] used experts of different complexity for adaptive inference under bandwidth constraints. Ahmed et al. adapted various CNNs (e.g., AlexNet, ResNet) into MoE settings [

11], supporting architectural diversity. These studies show the flexibility of MoE for combining different expert types.

Overall, MoEs have shown promising results on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet benchmarks, validating their utility in scalable and adaptive image classification systems.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview

This study investigates the application of MoE architectures for image classification on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Three experiments were conducted to explore increasingly complex expert configurations and gating mechanisms. All experiments were implemented in PyTorch within the LEMUR AutoML framework, using standard CIFAR-10 splits (50,000 training and 10,000 test images) and normalization-based preprocessing. Random cropping, horizontal flipping, and mixup augmentation were applied to enhance model generalization. Training utilized GPU acceleration, stochastic gradient descent (SGD) or AdamW optimizers depending on model configuration, and load-balancing regularization to encourage even expert utilization.

3.2. Experiment 1: Baseline MoE Architectures

Training of computer vision models is performed using the AI Linux docker image abrainone/ai-linux

1 on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090/4090 24G GPUs of the CVL Kubernetes cluster at the University of Würzburg and a dedicated workstation.

The first set of experiments (MoE-0707 to MoEv8) evaluated homogeneous Mixture-of-Experts models with identical CNN-based experts and a learned gating network. Each expert was implemented as a three-layer fully connected subnetwork stacked upon a convolutional feature extractor with six convolutional blocks and intermediate batch normalization and dropout. The gating module employed a two-layer feedforward network with batch normalization and a top-2 routing strategy. Gaussian noise was introduced to gate logits during training to promote balanced expert activation.

Eight experts (

) were used per model, and only the two highest-weighted experts were activated for each input sample. A small auxiliary loss encouraged balanced expert selection:

where

measures deviation from uniform expert usage. The best-performing configuration,

MoEv7, achieved the highest test accuracy and stability among all variants.

3.3. Experiment 2: MoE with AlexNet Experts

The second experiment extended the base MoE architecture by replacing generic experts with AlexNet-based CNNs, resulting in models MoEv9-AlexNet through MoEv9-AlexNetv4. Each expert incorporated the standard AlexNet feature extractor with customized initialization schemes to promote class-specific specialization. The gating network (ImprovedGate) utilized convolutional and fully connected layers with a temperature-controlled softmax and learned noise scaling to stabilize routing decisions. The number of active experts per input was limited to top-2 routing.

To encourage diversity and specialization, auxiliary terms for load balance and inter-expert diversity were added:

Model MoEv9-AlexNetv3 demonstrated the best trade-off between accuracy, expert specialization, and computational efficiency.

3.4. Experiment 3: Heterogeneous Experts

The final configuration,

MoE-hetero4-Alex-Dense-Air-Bag, introduced architectural heterogeneity by combining four distinct CNN backbones—

AlexNet,

DenseNet,

AirNet, and

BagNet—as experts. A lightweight convolutional gating network learned to assign soft routing weights to each expert, with training noise facilitating exploration and avoiding early specialization collapse. Each expert was trained jointly through weighted aggregation of logits:

where

denotes the gating weight and

the expert’s output logits.

The training process incorporated mixup augmentation and label smoothing () to enhance robustness. The optimization used AdamW with differential learning rates for experts and the gate, and learning rate scheduling was performed via a warm-up followed by cosine annealing. The comprehensive diagnostics tracked expert utilization entropy, specialization, and per-class performance, revealing a strong complementarity among heterogeneous experts.

3.5. Training Configuration

All experiments were trained for 50 to 200 epochs with verging batch size. For homogeneous models, SGD with momentum 0.9 and weight decay was used. The heterogeneous MoE employed AdamW with warm-up and cosine annealing schedulers. A learning rate of 0.01 was used initially, decayed adaptively by the scheduler. Gradients were clipped to maintain stability. Performance metrics included top-1 classification accuracy, expert utilization entropy, and diversity metrics. Across experiments, the best-performing models (MoEv7, MoEv9-AlexNetv3, and MoE-hetero4) showed progressive improvements, demonstrating the effectiveness of adaptive routing and architectural diversity in MoE frameworks.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Task

All experiments were conducted on CIFAR-10, a 10-class image classification benchmark with 50,000 training and 10,000 test images. Images were normalized per channel using dataset statistics. Data augmentation included random horizontal flips, random crops with 4-pixel padding, and (for the heterogeneous MoE) mixup ().

4.2. Evaluation Protocol and Metrics

We report top-1 accuracy on the CIFAR-10 test set. Unless otherwise stated, results are computed after the final training epoch. To reduce variance, each configuration was trained with three random seeds and we report the mean accuracy (the best single-seed model is highlighted in the next section). In addition to accuracy, we tracked expert utilization entropy and simple diversity indicators to analyze routing behavior.

4.3. Baselines and Comparison Targets

Our primary comparison is to the existing LEMUR models (dense CNN backbones) used as internal baselines. The project objective, set at the outset, was to outperform the strongest LEMUR baseline by 2–10% absolute accuracy using Mixture-of-Experts designs. Accordingly, we evaluate three MoE families:

Experiment 1 (Homogeneous MoE):MoE-0707, MoEv2, MoEv3, MoEv4, MoEv5, MoEv6, MoEv7, MoEv8.

Experiment 2 (AlexNet Experts):MoEv9-AlexNet, MoEv9-AlexNetv2, MoEv9-AlexNetv3, MoEv9-AlexNetv4.

Experiment 3 (Heterogeneous Experts):MoE-hetero4-Alex-Dense-Air-Bag.

4.4. Implementation Details

All models were implemented in

PyTorch under the LEMUR codebase. Training used a single GPU. Unless specified in

Section 3, the following defaults were used: batch size 128, total epochs 50, gradient clipping (max-norm

or 3 as appropriate), and label smoothing

for the heterogeneous MoE. Homogeneous MoEs optimized with

SGD (momentum

, weight decay

), while the heterogeneous MoE used

AdamW with differential learning rates for gate vs. experts, warm-up, and cosine annealing. Routing employed

top-2 selection with a small training-time noise on gate logits and an auxiliary

load-balance loss; AlexNet-MoEs additionally used a lightweight

diversity term.

4.5. Model Selection

Within each experiment family, the checkpoint with the highest validation accuracy (or, when not available, the highest running test accuracy at end of training) was chosen as the representative model: MoEv7 (Exp. 1), MoEv9-AlexNetv3 (Exp. 2), and MoE-hetero4 (Exp. 3).

5. Results and Discussion

All results are reported on the CIFAR-10 test set. We summarize each experiment with a compact table (final / peak accuracy and the epoch of the peak) and a training curve figure.

5.1. Experiment 1: Homogeneous MoE Models

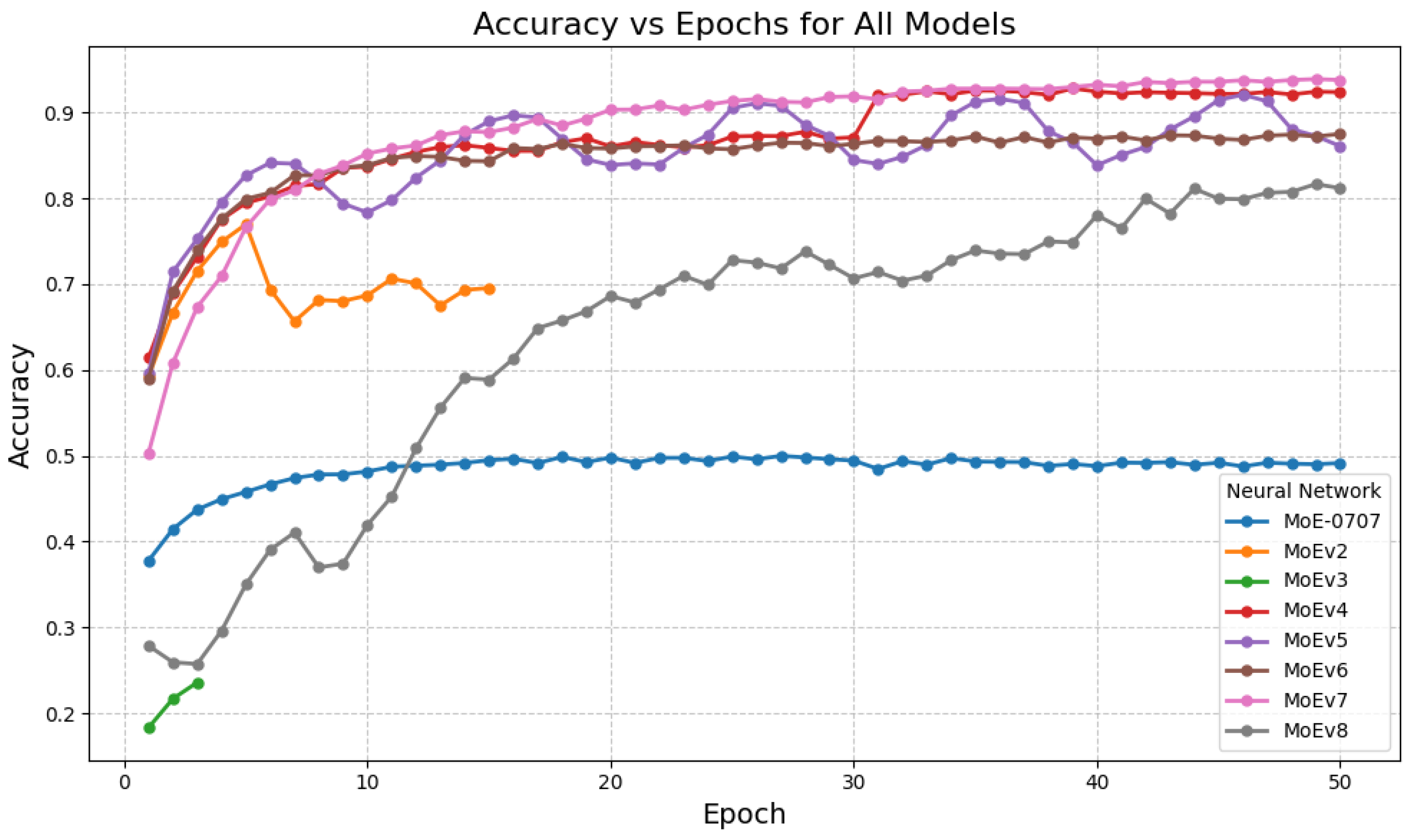

Observations

Among homogeneous MoEs,

MoEv7 achieved the highest final accuracy (

0.9379) and peaked at

0.9390 near epoch 49 (

Table 1). Earlier variants (e.g.,

MoE-0707,

MoEv2) underperformed, while

MoEv4/

MoEv6 converged competitively but below

MoEv7. Curves in

Figure 1 show stable late-epoch behavior for the strongest variants.

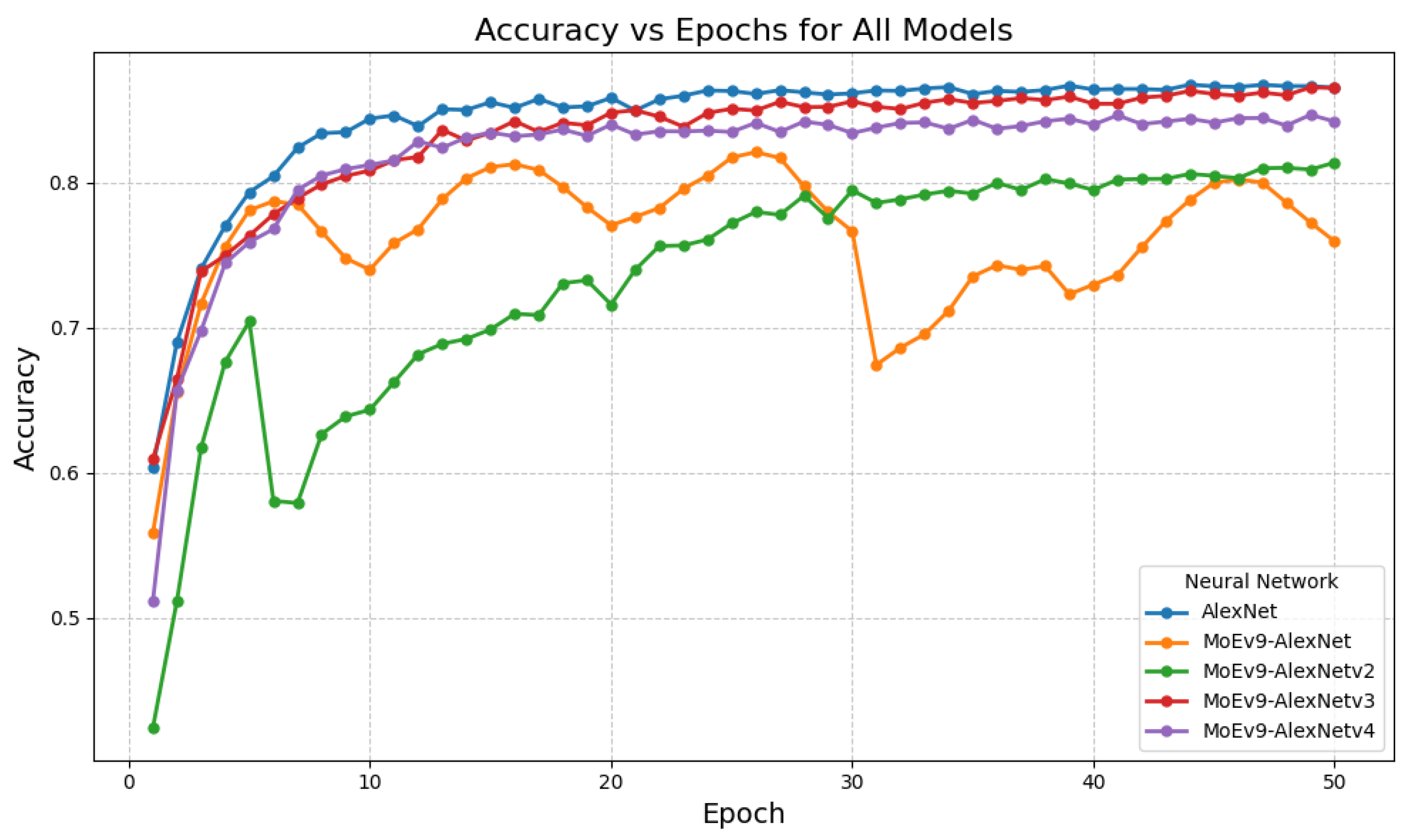

5.2. Experiment 2: MoE with AlexNet Experts

Observations

The strongest AlexNet-expert model,

MoEv9-AlexNetv3, reached a final accuracy of

0.8652 (peak

0.8656 at epoch 49), outperforming other AlexNet MoE variants (

Table 2).

Figure 2 shows that v3 converges more smoothly and maintains a higher plateau than v1/v2/v4.

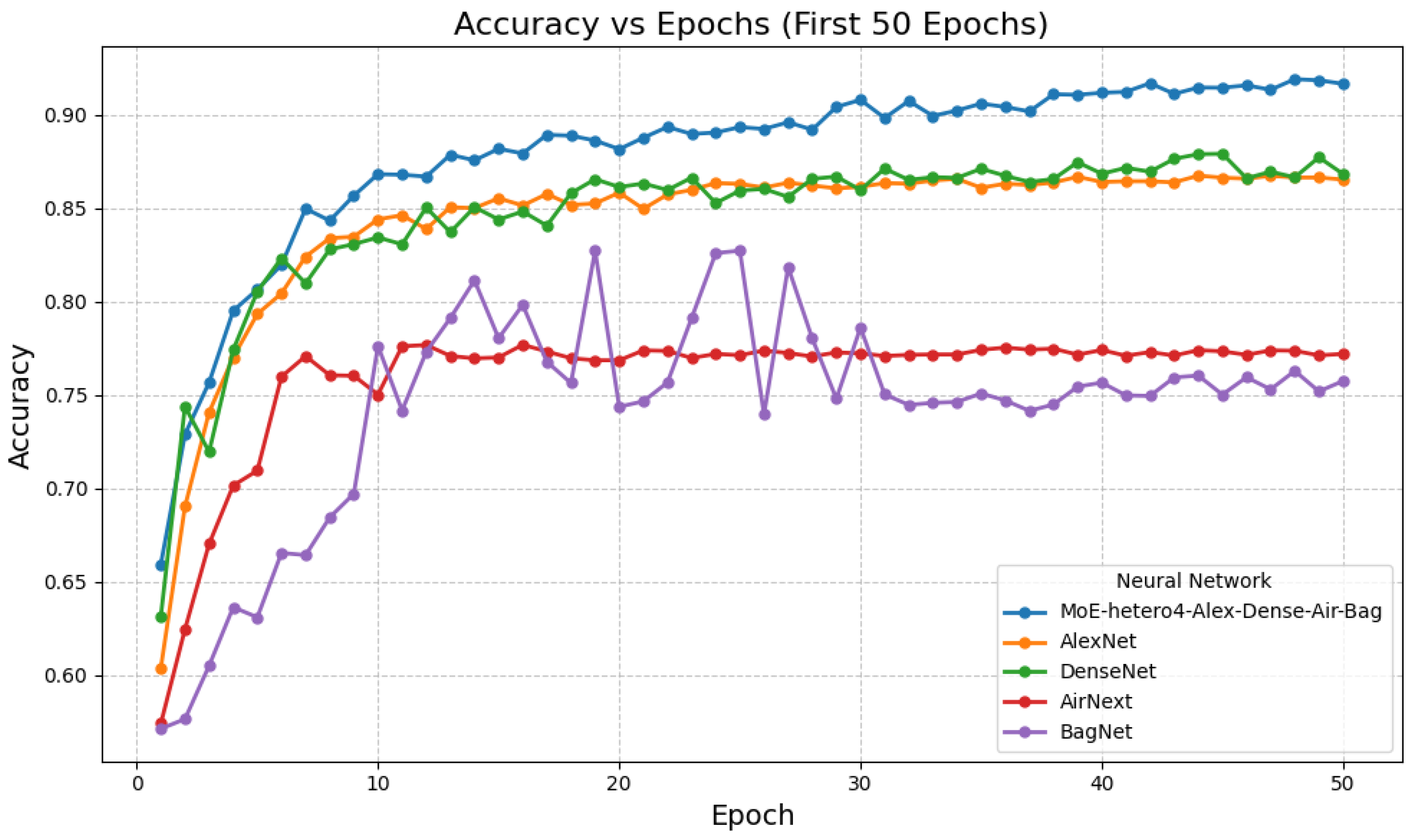

5.3. Experiment 3: Heterogeneous MoE with Diverse CNN Experts

Observations

The heterogeneous MoE attained a final accuracy of

0.9026 and peaked at

0.9313 around epoch 153 (

Table 3). Within the single-model baselines, DenseNet (final 0.8684) and AlexNet (final 0.8654) were strongest; the heterogeneous MoE exceeded both. Early-epoch trends in

Figure 3 indicate consistent gains over the standalone backbones.

5.4. General Discussion

Across the three experiments, the best homogeneous model (MoEv7) achieved the highest overall final accuracy (0.9379). The heterogeneous MoE reached a comparable peak (0.9313) with stable long-horizon training, while the AlexNet-expert variant (MoEv9-AlexNetv3) delivered solid improvements over other AlexNet MoEs. These results support two practical conclusions: (i) careful gating and regularization in homogeneous MoEs can yield the strongest absolute accuracy; and (ii) architectural diversity in heterogeneous MoEs offers competitive performance while maintaining stable convergence.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated several Mixture-of-Experts configurations for image classification on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The experiments covered (i) homogeneous MoEs with shared CNN backbones, (ii) AlexNet-based MoEs, and (iii) a heterogeneous MoE combining distinct architectures (AlexNet, DenseNet, AirNet, BagNet). Among all configurations, the homogeneous MoEv7 achieved the best final accuracy (93.79%), followed closely by the heterogeneous MoE (93.13% peak). The results demonstrate that MoE architectures can effectively enhance model capacity and specialization without significant instability. In particular, heterogeneous MoEs show promising scalability for integrating multiple backbone families while maintaining strong classification performance.

References

- DeepSeek-AI. DeepSeek-V2: A Strong, Economical, and Efficient Mixture-of-Experts Language Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.06066. [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi, A.T.; Kochnev, R.; Khalid, W.; Qin, F.; Uzun, T.A.; Dhameliya, Y.S.; Kathiriya, Y.K.; Bentyn, Z.A.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. LEMUR Neural Network Dataset: Towards Seamless AutoML. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.10552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEMUR 2: Unlocking Neural Network Diversity for AI. arXiv 2025.

- Kochnev, R.; Goodarzi, A.T.; Bentyn, Z.A.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. Optuna vs Code Llama: Are LLMs a New Paradigm for Hyperparameter Tuning? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), 2025; pp. 5664–5674. [Google Scholar]

- Gado, M.; Taliee, T.; Memon, M.D.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. VIST-GPT: Ushering in the Era of Visual Storytelling with LLMs? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.19267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupani, B.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. Exploring the Collaboration Between Vision Models and LLMs for Enhanced Image Classification. Dimensions 2025, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, W.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. A Retrieval-Augmented Generation Approach to Extracting Algorithmic Logic from Neural Networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2512.04329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochnev, R.; Khalid, W.; Uzun, T.A.; Zhang, X.; Dhameliya, Y.S.; Qin, F.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. NNGPT: Rethinking AutoML with Large Language Models. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, Y.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. Preparation of Fractal-Inspired Computational Architectures for Advanced Large Language Model Analysis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.07329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesani, K.; Ignatov, D.; Timofte, R. LLM as a Neural Architect: Controlled Generation of Image Captioning Models Under Strict API Contracts. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Torresani, L. Network of experts for large-scale image categorization. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2016; Springer; pp. 516–532. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S.; Wilber, M.; Belongie, S. Hard mixture of experts for large scale weakly supervised vision. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Bender, G.; Le, Q.V.; Ngiam, J. CondConv: Conditionally parameterized convolutions for efficient inference. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2019; Vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Wang, T.; Xie, P.; Yu, P.S. Deep Mixture of Experts via Shallow Embedding. In Proceedings of the Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (UAI), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme, C.; Puigcerver, J.; Kolesnikov, A.; Houlsby, N. Scaling Vision with Sparse Mixture of Experts. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2021; Vol. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Puigcerver, J.; Riquelme, C.; Houlsby, N. Are Mixture-of-Experts Networks Robust to Adversarial Examples? arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.11908. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.Y.; Kirillov, A.; Girshick, R.; Feichtenhofer, C. Sparse Mixture of Experts are Vital for Vision Tasks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.09383. [Google Scholar]

- Puigcerver, J.; Riquelme, C.; Houlsby, N. Soft MoE: Differentiable Sparse Mixture of Experts. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.09603. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, T.; Andreopoulos, Y. Biased Mixture of Experts for Efficient Inference of Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2020, 29, 7402–7417. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).