1. Introduction

Human activities shape every moment of our lives. We wave to friends, cook meals, exercise, work, and sleep. These actions seem simple to us, but teaching machines to recognize and understand them presents enormous challenges. Human Action Recognition (HAR) tackles this problem head-on, and researchers have made tremendous progress in recent years. Today, HAR systems can detect when elderly people fall, monitor patients during rehabilitation, control smart homes, and even help autonomous cars understand pedestrian behavior. Consider what happens when a nurse monitors twenty patients simultaneously. HAR systems can watch every patient through cameras or sensors, instantly alerting medical staff when someone falls or shows signs of distress. In factories, these systems track workers and identify unsafe behaviors before accidents occur. Sports coaches use HAR to analyze athlete performance and technique. Parents can monitor their children’s activities through smart home systems. The applications seem endless, and each one makes our lives safer, more convenient, or more efficient. Deep learning changed everything for HAR research. Before 2012, researchers manually designed features to represent human actions [

1]. They would extract hand-crafted [

2] descriptors, such as optical flow patterns, histograms of gradients, or spatiotemporal interest points [

3]. These methods worked reasonably well for simple scenarios, but they struggled with real-world complexity. People move differently, lighting changes, cameras shake, and backgrounds vary. Traditional approaches were unable to handle this variability effectively.

Then convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

4] arrived and revolutionized computer vision. Researchers quickly adapted these architectures for action recognition. Two-stream networks became popular, processing RGB frames and optical flow separately before combining results. 3D CNNs like C3D and I3D emerged to capture temporal information directly [

5]. Researchers developed Two-Stream Inflated 3D (I3D) networks that inflate 2D filters into 3D, enabling transfer learning from ImageNet pretrained models. Slow Fast networks process actions at different temporal resolutions, mimicking how human vision works. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

6] and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

7] networks offered another approach. These architectures naturally handle sequential data, making them suitable for skeleton-based action recognition. Researchers extract human pose information using tools like OpenPose or AlphaPose, then feed joint coordinates into LSTM networks. This approach works well because skeleton data contains less noise than raw video and requires less computational power. Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [

8] represent the latest breakthrough in skeleton-based HAR. Human skeletons form natural graph structures where joints are nodes and bones are edges. ST-GCN (Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network) [

9] was the first to exploit this insight, achieving state-of-the-art results on skeleton action recognition. Subsequent works like 2s-AGCN, MS-G3D, and CTR-GCN further improved performance by designing better graph topologies and attention mechanisms.

Transfer learning has become crucial for the practical deployment of HAR. Training deep networks from scratch requires massive datasets and computational resources. Most real-world applications lack sufficient labeled data. Researchers discovered they could initialize HAR models with weights pretrained on large datasets like ImageNet or Kinetics. This approach dramatically improves performance, especially for small datasets. Domain adaptation techniques enable models to generalize across diverse environments, camera angles, and populations [

10]. Sensor- based HAR follows different principles but achieves similar goals. Smartphones, smartwatches, and IoT devices generate continuous streams of accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer data. CNN and RNN architectures process these time-series signals effectively. Researchers developed specialized architectures like DeepConvLSTM [

11] and CNN-LSTM hybrids for sensor fusion [

12]. Multi-scale CNNs capture both fine-grained and coarse-grained temporal patterns in sensor data. Despite impressive technical progress, serious gaps remain between research and practice. Most HAR papers focus on benchmark accuracy rather than real-world deployment challenges. Laboratory conditions differ dramatically from field environments. Lighting changes throughout the day, people wear different clothes, cameras get dirty, and sensors drift over time. Privacy concerns limit the use of video-based monitoring in many applications. Computational constraints prevent the deployment of complex models on edge devices. These practical issues receive insufficient attention in current literature.

The explainability problem represents perhaps the most critical gap. Deep learning models operate as black boxes, providing predictions without explanations. Healthcare professionals need to understand why a system detected a fall. Security personnel want to know which visual cues triggered an alert. Factory managers require explanations for safety violations. This lack of transparency hinders the adoption of HAR in high-stakes applications where incorrect decisions can have severe consequences. This survey examines HAR from three interconnected angles that existing literature rarely combines. We analyze vision-based, skeleton-based, and sensor-based approaches not just as technical methods, but as practical solutions for real applications. Vision-based HAR dominates surveillance, sports analysis, and human-computer interaction. RGB cameras are ubiquitous and provide rich information, but they raise privacy concerns and require significant computational resources. Modern architectures like TSN, TSM, and X3D achieve impressive accuracy on large-scale datasets like Kinetics and Something-Something. Skeleton-based methods extract pose information and analyze joint movements. These approaches preserve privacy since they discard appearance information while retaining action-relevant features. OpenPose, MediaPipe, and other pose estimation tools make skeleton extraction accessible. Graph convolutional networks excel at processing skeletal data, with recent methods like MS-G3D and InfoGCN pushing accuracy boundaries [

13]. Transfer learning from large skeleton datasets like NTU RGB+D enables effective training on smaller datasets. Sensor-based HAR leverages ubiquitous mobile devices and wearables for continuous monitoring. Smartphones contain sophisticated sensor suites including accelerometers, gyroscopes, magnetometers, and GPS. Smartwatches add heart rate and sometimes blood oxygen monitoring. These devices enable natural, unobtrusive activity tracking. Deep learning architectures process multi-sensor time series effectively, with attention mechanisms helping models focus on relevant temporal patterns. Application domains drive technology selection and performance requirements. Healthcare applications prioritize reliability and interpretability over raw accuracy. A fall detection system that explains its decisions builds trust with medical staff. Smart home applications balance convenience with privacy concerns. Security applications require real-time processing and robust performance across diverse conditions.

Industrial applications need models that generalize across different workers, equipment, and environments. Vision-based methods can generate spatial attention maps and temporal summaries. Skeleton-based approaches can highlight critical joints and movement patterns. Sensor-based systems can identify important sensor modalities and temporal windows. We discuss how different XAI techniques suit different application requirements and user needs. Our goal extends beyond summarizing existing work.

We want to help researchers and practitioners understand how to select appropriate HAR approaches for specific applications, how to address deployment challenges, and how to integrate explainability from the design phase rather than as an afterthought. The HAR field needs systems that work reliably in real environments, respect user privacy, operate within computational constraints, and provide understandable explanations for their decisions. This survey provides a roadmap toward that vision.

2. Data Modalities

The effectiveness of HAR systems depends critically on the type and quality of input data these systems process. Real-world deployments must operate within environmental constraints - hospital corridors offer RGB surveillance cameras for fall detection, while industrial settings require depth sensors that function reliably under variable lighting conditions. Personal activity monitoring typically exploits smartphone-embedded inertial sensors, whereas clinical gait analysis benefits from high-precision skeletal tracking systems. Selecting appropriate data modalities requires balancing competing requirements. RGB video provides comprehensive visual information, including facial expressions, object interactions, and environmental context, but creates significant privacy concerns that limit deployment in sensitive settings. Depth sensors address privacy issues by discarding appearance details while preserving spatial structure, though their performance degrades substantially in outdoor environments. Wearable inertial sensors enable continuous, unobtrusive monitoring across diverse environments but lack the contextual richness that visual modalities provide. Emerging approaches using WiFi and radar signals can monitor activities through obstacles but offer limited granularity for detailed movement analysis. Application requirements have historically driven the development of domain-specific sensing approaches. The gaming industry’s adoption of motion sensing platforms catalyzed advances in skeleton-based recognition and large-scale datasets like Kinetics-400. Healthcare applications have motivated research into privacy-preserving depth and sensor-based methods that maintain patient confidentiality. The widespread deployment of smartphones enabled accelerometer-based recognition to reach consumer applications at scale. Industrial safety monitoring has necessitated robust multimodal systems that operate reliably despite environmental factors, including dust, vibration, and dynamic lighting conditions.

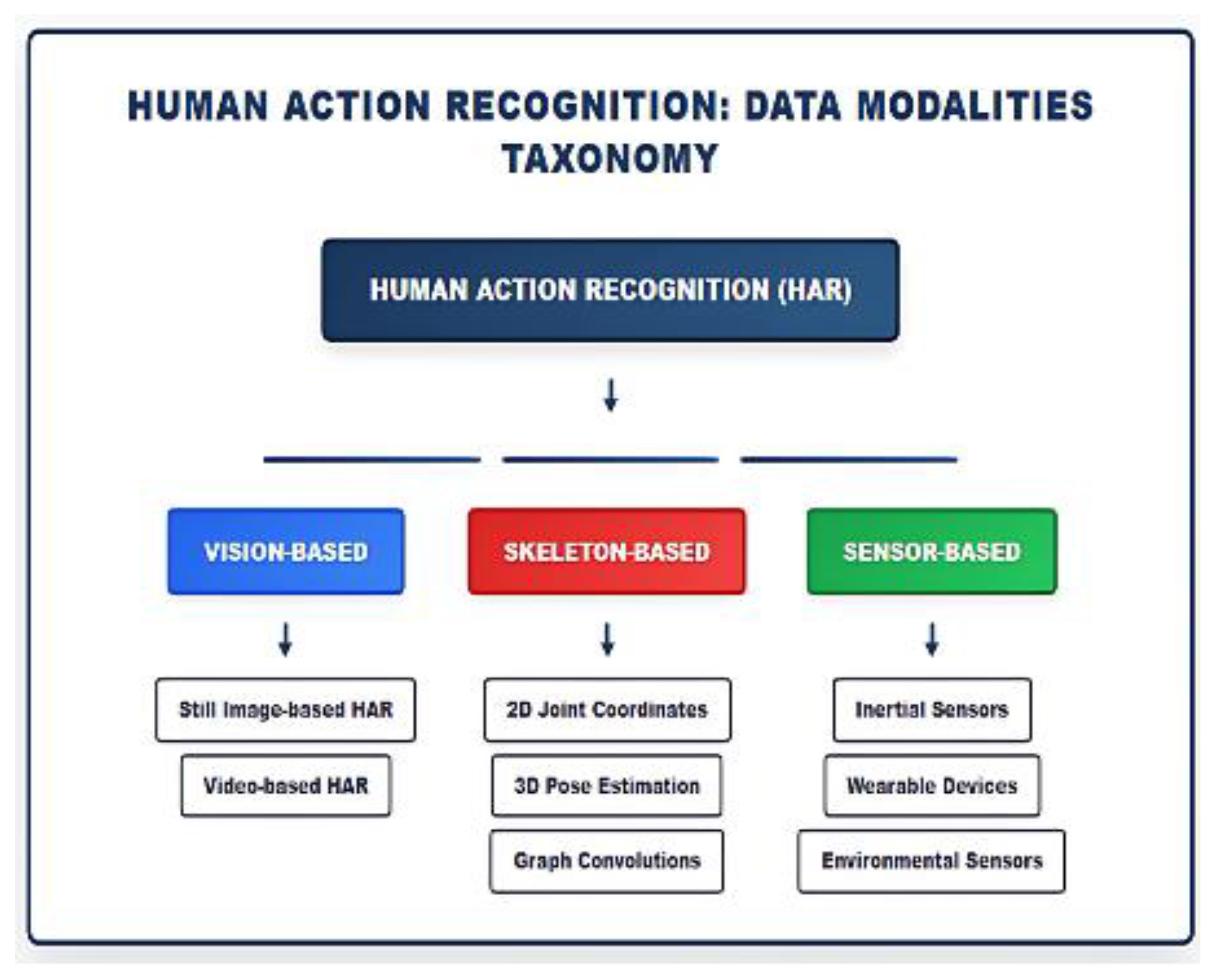

Figure 1.

Human Action Recognition Data Modalities Taxonomy showing three main categories: Vision-based (Still Image-based HAR, Video-based HAR), Skeleton-based (2D Joint Coordinates, 3D Pose Estimation, Graph Convolutions), and Sensor-based (Inertial Sensors, Wearable Devices, Environmental Sensors).

Figure 1.

Human Action Recognition Data Modalities Taxonomy showing three main categories: Vision-based (Still Image-based HAR, Video-based HAR), Skeleton-based (2D Joint Coordinates, 3D Pose Estimation, Graph Convolutions), and Sensor-based (Inertial Sensors, Wearable Devices, Environmental Sensors).

Contemporary HAR systems increasingly adopt multimodal architectures rather than relying on single data sources. A comprehensive smart home deployment might integrate passive infrared sensors for coarse activity detection, depth cameras for fall monitoring, and smartphone inertial data for detailed activity classification. The key consideration involves matching sensing capabilities to application requirements while accounting for deployment constraints.

This section examines how different data modalities serve the diverse landscape of HAR applications, beginning with vision-based approaches that continue to drive many of the field’s most significant advances.

2.1. Vision-Based HAR

Vision-based Human Action Recognition (HAR) is one of the most extensively studied paradigms in computer vision, leveraging image and video data to classify and interpret human activities. The core challenge lies in extracting discriminative spatial and temporal representations that are robust to variations in viewpoint, illumination, occlusion, and background clutter. Early approaches primarily relied on handcrafted descriptors such as Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [

14], Motion History Images (MHI) [

15], and spatiotemporal interest points, often combined with classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVM) [

16]. With the advent of deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) became the dominant feature extractors, enabling end-to-end learning from raw data. For video sequences, methods such as two-stream CNNs, 3D CNNs, and hybrid CNN–RNN architectures [

17] (e.g., LSTM, GRU) have been widely adopted to capture spatiotemporal dynamics. More recently, transformer-based models and graph-based approaches have emerged, incorporating attention mechanisms and structured representations for improved temporal reasoning and context modeling. Broadly, vision-based HAR research has evolved into two major directions: still image–based recognition, which focuses on learning discriminative pose and context features from a single frame, and video-based recognition, which exploits sequential modeling to capture motion and long-range temporal dependencies.

2.1.1. Still Image-Based HAR

Still image–based Human Action Recognition (HAR) is considerably more challenging than video-based recognition since temporal motion cues are absent, forcing models to rely exclusively on spatial appearance, pose configuration, and contextual information. This limitation makes recognition highly sensitive to background clutter, occlusion, and confusing inter-class similarities [

18,

19]. Earlier works adopted handcrafted descriptors such as poselets, HOG features, or part-based models, but these approaches lacked robustness in unconstrained environments [

19].

Deep learning has substantially advanced still-image HAR. Transfer learning has been a key technique to overcome limited labeled data. Chakraborty et al. fine-tuned CNNs pre-trained on ImageNet and evaluated them on Stanford 40 and PPMI datasets [

20]. Their approach achieved strong results across different action categories: 96.19% precision on the Stanford 40 body motion actions (11 classes), 78.02% accuracy on non-body motion actions (29 classes), and 77.2% mAP when considering all 40 Stanford classes together. On the PPMI dataset, they achieved 85.03% mAP for play instrument actions and 74.28% mAP for with instrument actions, with 74.00% mAP across all 24 PPMI classes. These transfer learning results significantly outperformed previous handcrafted feature approaches and demonstrated the effectiveness of fine-tuning deep CNNs for still-image action recognition [

20]. Similarly, Alam et al. employed EfficientNetB7 with over 12,600 images across 15 classes and achieved a peak training accuracy of 96.28% and validation accuracy above 93%, demonstrating that carefully tuned transfer learning combined with Grad-CAM++ visualizations provides both high accuracy and interpretability [

21].

Ensemble strategies have been particularly effective for improving performance in small and imbalanced datasets. Yu et al. [

22] introduced DELWO (Deep Ensemble Learning with Weight Optimization) and DELVS (Deep Ensemble Learning with Voting Strategy), showing that ensemble CNN models achieved strong results: up to 99.17% accuracy on Li’s dataset (DELVS2 and DELVS3 with tuning weight voting) and 73.69% on the Willow dataset (DELVS3 tuning), while effectively mitigating overfitting caused by small sample sizes [

22]. Banerjee et al. extended this direction by combining DenseNet-201 with spatial attention and fuzzy ensemble fusion through the Choquet integral. Their spatial attention module focuses on informative image regions using average and max pooling operations followed by 7 × 7 convolution, while the Choquet fuzzy integral dynamically combines outputs from attention-based and non-attention-based models based on confidence scores rather than fixed weights. Their model achieved 85.77% mAP on PPMI (24-class), 87.34% mAP on Stanford-40, and 80.19% mAP on BU-101, demonstrating that attention mechanisms combined with adaptive ensemble fusion effectively capture complementary structural information and improve generalization across datasets of varying scales and complexity [

23].

Beyond appearance-only methods, skeleton-aware frameworks have been applied to still-image HAR to enhance viewpoint robustness. Kim and Cho proposed a viewpoint-aware skeleton-based model that combines viewpoint categorization with 2D and 3D joint feature extraction for still image action recognition. Their three-step approach first categorizes camera viewpoint using a YOLO-based network, then extracts Euclidean Distance Matrix (EDM) features from 2D and 3D skeleton joints using state-of-the-art CNNs, and finally performs view-specific action classification using Random Forest classifiers. Enhanced with avatar-based synthetic data augmentation, their method achieved 89.67% accuracy on their custom 8-view dataset and 50.91% on Human3.6M, demonstrating improved robustness to viewpoint variations compared to view-agnostic approaches [

24].

Taken together, these developments highlight the rapid evolution of still-image HAR. From handcrafted features to CNN transfer learning, from ensembles to skeleton-aware models, performance has improved substantially, with recent approaches surpassing 90% accuracy on challenging benchmarks. Despite the inherent absence of temporal cues, careful exploitation of transfer learning, ensemble fusion, viewpoint modeling, and interpretability techniques like Grad-CAM++ has made still-image HAR a strong and increasingly reliable modality.

2.1.2. Video-Based HAR

Video-based Human Action Recognition (HAR) has been the dominant modality because videos provide both spatial and temporal cues. Early handcrafted methods exploited spatiotemporal interest points and optical flow features but were limited in handling occlusion, clutter, and real-world variability [

18]. With the advent of deep learning, CNN and RNN architectures have become the standard.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) were first adapted to action recognition through two-stream networks, which process RGB frames and optical flow independently before late fusion. Simonyan and Zisserman’s two-stream CNN achieved 59.4% accuracy on HMDB-51, establishing the effectiveness of joint appearance-motion modeling. Later implementations using deeper architectures like VGG-16 improved performance to 90.62% on UCF-101 and 58.17% on HMDB-51 for spatiotemporal fusion. To directly model temporal information, 3D CNNs such as C3D extended 2D filters into the temporal domain, though the review notes that 3D CNNs generally showed improvements over 2D approaches without providing specific accuracy figures for C3D on these datasets. The paper emphasizes that very deep networks like VGG-16 and ResNets significantly advanced the state of the art, with the best reported results reaching over 90% on UCF-101, benefiting from ImageNet pretraining and deeper architectures [

25].

The paradigm shift in video action recognition from computationally expensive full finetuning to parameter-efficient adaptation represents a critical advancement in making state-of-the-art models accessible to the broader research community. While traditional approaches like TimeSformer and VideoSwin achieve impressive performance on benchmarks such as Kinetics-400, their training requirements, 121M and 197M tunable parameters, respectively, create significant barriers in terms of computational resources and memory footprint. The emergence of adapter-based methods fundamentally challenges this trade-off: AIM demonstrates that by strategically freezing pre-trained image transformers and introducing lightweight adapters for spatial, temporal, and joint adaptation, it is possible to achieve 87.5% top-1 accuracy on Kinetics-400 while tuning only 38M parameters, a reduction of over 80% compared to full finetuning approaches. This efficiency gain extends beyond parameter count, with AIM reducing memory consumption by 50% and training time by 42% compared to VideoSwin on equivalent hardware, while the method’s simplicity enables seamless adaptation across different pre-trained foundations from

IN-21K to CLIP models. The implications are particularly significant for temporal-heavy datasets like Something- Something-v2, where, despite the challenges of capturing complex temporal dynamics with frozen attention weights, AIM achieves 70.6% accuracy, demonstrating that the inductive biases learned during image pre-training can be effectively repurposed for spatiotemporal reasoning through minimal architectural modifications [

26].

Hybrid CNN–RNN architectures remain important for modeling long-term temporal dependencies. In particular, the proposed DS-GRU framework combines convolutional spatial encoders with gated recurrent units arranged in dense skip connections, enabling efficient sequential modeling. On challenging benchmarks, DS-GRU achieved 72.3% on HMDB51 and 95.5% on UCF-101, ranking near the top among LSTM-based methods, while on the YouTube Actions dataset it reached 97.17%, outperforming earlier CNN-only baselines. Beyond accuracy, its reduced parameter count and lower inference time make it attractive for real-time video surveillance applications. [

27]. Synthetic and domain-adaptive training have addressed generalization challenges. Varol et al. introduced SURRE- ACT, a synthetic dataset of 3D avatars, which improved cross-view generalization when models were evaluated on unseen camera viewpoints. On the NTU dataset, accuracy increased from 53.6% to 69.0%, while on UESTC it rose from 49.4% to 66.4%. These results confirm the effectiveness of synthetic augmentation in bridging domain gaps for robust action recognition. [

28].

Together, these results demonstrate a clear trajectory: from handcrafted and two-stream CNNs to 3D CNNs and hybrid CNN–RNNs, and now transformer-based multimodal models. Reported benchmarks consistently exceed 90% accuracy on UCF101 and 65–70% on HMDB51, while larger datasets such as Kinetics-400 remain more challenging, with state-of-the-art models achieving 80% top-1 accuracy. These advances reflect both methodological innovation and the availability of large-scale video datasets, though real-world deployment still faces constraints of efficiency, privacy, and robustness to uncontrolled conditions.

2.2. Skeleton-Based HAR

Skeleton-based Human Action Recognition has emerged as a powerful paradigm that leverages the structural representation of human poses to understand and classify actions. Unlike RGB-based methods that process dense pixel information, skeleton-based approaches utilize sparse joint coordinates representing key anatomical landmarks, offering several distinct advantages, including robustness to lighting variations, background clutter, and viewpoint changes while maintaining computational efficiency [

29].

2.2.1. Evolution from Traditional to Deep Learning Approaches

Early skeleton-based HAR relied heavily on handcrafted features extracted from joint trajectories and geometric relationships. Methods like those using Histogram of 3D Joints (HOJ3D) [

30] and actionlets captured local motion patterns around individual joints, while approaches based on Lie groups modeled the geometric properties of skeletal sequences [

31]. These traditional methods achieved reasonable performance on simple datasets but struggled with complex, real-world scenarios due to their limited representational capacity and inability to capture long-range temporal dependencies.

The introduction of deep learning has fundamentally transformed skeleton-based HAR. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, have become early adoption choices for modeling temporal sequences of skeletal data. Du et al. proposed hierarchical RNNs that divided the human skeleton into five body parts, with separate LSTMs processing each part before fusion, achieving 59.1% accuracy on the NTU RGB+D dataset [

32]. However, RNN-based methods faced limitations in capturing complex spatial relationships between joints and suffered from gradient vanishing problems in long sequences [

33].

2.2.2. Graph Convolutional Networks Revolution

The breakthrough came with Spatial Temporal Graph Convolutional Networks (ST-GCN), which naturally modeled skeleton data as graphs where joints represent nodes and bones represent edges [

9]. This paradigm shift enabled direct modeling of both spatial dependencies between connected joints and temporal evolution across frames. ST- GCN achieved 81.5% accuracy on NTU RGB+D, significantly outperforming previous RNN-based methods and establishing graph neural networks as the dominant approach for skeleton-based HAR.

Building on ST-GCN’s success, researchers developed increasingly sophisticated graph architectures. Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks (AGC-LSTM) learned graph topology automatically rather than relying on fixed physical connections [

34], while Shift-GCN introduced efficient shift operations that achieved 90.7% accuracy on NTU RGB+D with reduced computational complexity [

35]. Recent works like CTR-GCN further advanced the field by incorporating channel-wise topology refinement, achieving 92.4% accuracy on NTU RGB+D 60 and 88.9% on NTU RGB+D 120 [

36].

2.2.3. Attention Mechanisms and Optimization

Modern skeleton-based HAR systems extensively employ attention mechanisms to focus on discriminative joints and temporal segments. Spatial attention helps identify body parts most relevant to specific actions, for instance, emphasizing hand and arm movements for gesture recognition, while temporal attention captures critical frames within action sequences [

37]. Recent systematic reviews analyzing 92 papers from 2014-2024 revealed that hybrid attention mechanisms combining spatial and temporal attention achieve the highest performance improvements, with gains up to 12.60% on cross-view evaluation tasks [

38].

Channel-wise attention mechanisms have also proven effective, with joint-wise channel attention (JCA) focusing on informative feature channels for each joint independently [

39].

Self-attention mechanisms, inspired by Transformer architectures, enable modeling of global dependencies between all joint pairs, though they typically provide more modest improvements compared to hybrid approaches [

40].

2.2.4. Multi-Stream Fusion Strategies

Contemporary skeleton-based HAR systems employ so sophisticated fusion strategies to combine information from multiple data streams. Feature-level fusion approaches concatenate or sum features from different skeletal representations (e.g., joint coordinates, bone vectors, motion patterns) before classification, with concatenation-based methods achieving superior performance by providing comprehensive feature representations [

41]. Decision-level fusion combines predictions from multiple specialized classifiers, proving particularly effective for cross-subject generalization scenarios [

42].

Advanced fusion techniques incorporate learned weighting schemes rather than fixed combination rules. Adaptive fusion methods dynamically adjust the importance of different streams based on action characteristics, while meta-learning approaches optimize fusion strategies across different action categories, demonstrating that dynamic fusion significantly outperforms static combination approaches [

43].

2.2.5. 3D Pose Estimation Integration

A critical component of skeleton-based HAR is robust 3D pose estimation from various input modalities. While RGB-D sensors enable direct 3D joint localization through depth information projection, this approach suffers from significant limitations in hand pose estimation and scenarios with occlusion or incomplete depth data [

44]. Modern systems increasingly adopt monocular 3D pose estimation methods, including 2D-to-3D lifting approaches that infer 3D coordinates from 2D joint detections without requiring depth information [

45].

Methods like VideoPose3D and MeTRAbs demonstrate that temporal information from video sequences can resolve ambiguities inherent in single-frame 3D pose estimation [

46]. SMPLify-X and similar parametric model fitting approaches provide anatomically consistent pose estimates by fitting statistical body models to 2D joint detections, though at significant computational cost [

47]. Recent comparisons show that 2D-to-3D lifting methods achieve superior accuracy compared to traditional depth-based projection, with improvements of 4-8% on standard benchmarks [

48].

2.2.6. Emerging Architectures and Techniques

Transformer-based architectures represent the latest evolution in skeleton-based HAR. These models apply self-attention mechanisms across both spatial and temporal dimensions, enabling global context modeling that surpasses traditional graph convolutions [

49]. Recent Transformer variants specifically designed for skeleton data achieve state-of-the-art performance while maintaining computational efficiency through sparse attention patterns and hierarchical processing [

50].

Contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful technique for skeleton-based HAR, particularly valuable given the typical scarcity of labeled skeleton data. Methods like InfoGCN use contrastive objectives to learn discriminative representations by maximizing agreement between augmented versions of the same action while minimizing similarity to different actions [

13]. This approach has proven particularly effective for few-shot learning scenarios and domain adaptation tasks.

2.2.7. Real-World Applications and Deployment

Skeleton-based HAR demonstrates exceptional performance in practical applications where environmental robustness is crucial. In healthcare monitoring, these systems achieve over 95% accuracy in fall detection applications, significantly outperforming RGB-based methods in challenging lighting conditions and privacy-sensitive environments [

51]. Smart home systems leverage skeleton-based recognition for gesture control interfaces, while human-robot collaboration scenarios benefit from the method’s ability to recognize both full-body actions and fine-grained hand gestures [

52].

Industrial applications include worker safety monitoring and ergonomic assessment, where skeleton-based systems track worker postures and identify potentially hazardous behaviors [

53]. Sports analytics increasingly rely on skeleton-based approaches for technique analysis and performance optimization, leveraging the method’s ability to capture precise biomechanical patterns regardless of uniform colors or equipment variations [

54].

2.3. Sensor-Based HAR

Sensor-based Human Activity Recognition (HAR) has become a fundamental paradigm in ubiquitous computing due to the widespread availability of wearable devices, smartphones, and IoT platforms equipped with inertial and biosensors. Unlike vision-based HAR, which relies on pixel-level cues, sensor-based approaches capture multi-dimensional time-series signals such as acceleration, angular velocity, and orientation. These signals are inherently invariant to environmental disturbances, such as lighting, occlusion, and background clutter, while also preserving privacy. This makes it particularly suited for applications in healthcare monitoring, fall detection, fitness tracking, smart homes, and industrial safety [

55].

2.3.1. Evolution from Traditional to Deep Learning Approaches

Traditional HAR systems relied on handcrafted feature extraction, including statistical descriptors, Fourier coefficients, and wavelet transforms. These were processed using classifiers like k-NN, SVM, random forests, and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), achieving competitive accuracy on datasets such as WISDM and USC-HAD. However, their reliance on feature engineering and inability to generalize across heterogeneous users, limited practical scalability [

56].

Deep learning transformed HAR by automating feature extraction. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) efficiently capture local dependencies in sensor streams, while RNNs and LSTMs model sequential temporal patterns. Hierarchical models like HiHAR introduced a two-stage architecture combining CNNs with BiLSTMs, which achieved 97.98% on UCI HAPT and 96.16% on Mobi-Act, surpassing prior CNN–LSTM baselines [

57]. Other architectures, such as deep selective kernel CNNs, dynamically adjusted receptive field sizes, enabling adaptive feature learning for both short and long-duration activities across datasets like PAMAP2, UniMiB-SHAR, and Opportunity [

58].

2.3.2. Meta-Heuristics and Optimization Strategies

Meta-heuristic algorithms, including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), have been adopted for feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, and sensor fusion. These methods reduced redundancy while improving classification accuracy by up to 8% on UCI HAR [

59]. Additionally, normalization strategies have been scrutinized. Standard batch normalization often causes channel collapse, where most sensor channels contribute negligibly to recognition. To mitigate this, Channel-Equalization-HAR reactivated suppressed channels using whitening and decorrelation, achieving superior recognition on UCI-HAR, WISDM, PAMAP2, and USC-HAD with low additional cost, and demonstrated feasibility on Raspberry Pi deployment [

60].

2.3.3. Speed–Accuracy Tradeoff and Lightweight Networks

Deploying HAR on mobile and wearable platforms requires balancing recognition accuracy, inference latency, and power consumption. RepHAR introduced structural reparameterization by decoupling training-time multi-branch CNNs into single-path inference models. This achieved 0.83–2.18% higher accuracy on UCI-HAR, PAMAP2, UniMiB-SHAR, and Opportunity, while reducing parameters by up to 44% and running 72% faster on Raspberry Pi compared to baseline CNNs [

61]. Similarly, compact attention-based CNNs enhanced recognition robustness under noisy signals without incurring significant overhead [

62].

2.3.4. Complex and Concurrent HAR

Early HAR studies assumed single-label classification, but real-world activities often overlap (e.g., walking while texting). New frameworks incorporate concurrent HAR, leveraging spatiotemporal modeling and Transformers to recognize overlapping actions. Studies using the Opportunity and Real-world datasets demonstrated that concurrent HAR significantly outperforms traditional single-activity recognition by capturing hierarchical and simultaneous motion patterns [

63].

2.3.5. Data Scarcity and Cross-Modality Learning

Labeled HAR datasets are scarce due to costly annotation. Generative approaches and transfer learning mitigate this limitation. IMUGPT 2.0 reports macro-F1 improvements that depend on dataset and model; for example, with a DeepConvLSTM + self-attention backbone, adding virtual IMU data improves RealWorld (77.50→80.82) and PAMAP2 (64.36→73.77), but can underperform on USC-HAD and MyoGym (61.82→59.12, 50.63→47.58) when deep models overfit to generated signals [

64]. Self-supervised learning, GAN-based augmentation, and domain adaptation further enhance cross-user generalization and address inter-device variability [

65,

66].

2.3.6. Benchmark Datasets

HAR research has been benchmarked on numerous datasets:

UCI HAR: Smartphone IMU signals, 6 activities, 30 users [

67].

PAMAP2: Multisensory dataset with 18 annotated activities and heart rate data [

68].

USC-HAD: 12 activities captured with accelerometer and gyroscope [

69].

Opportunity++: 4.5M samples across wearable, object, and ambient sensors [

70].

UniMiB-SHAR: Smartphone accelerometer dataset including falls [

71].

Motion Sense: Smartphone IMU dataset with 12 motion attributes [

72].

These datasets remain crucial but highlight challenges in cross-dataset generalization due to inconsistent labeling, sensor placements, and sampling rates [

73].

2.3.7. Comprehensive Research Pipelines

Liu et al. proposed a nine-stage HAR pipeline (HAR- Pipeline), covering equipment selection, data acquisition, segmentation, feature extraction, model training, evaluation, and deployment. This systematic framework emphasizes iterative refinement and multidisciplinary integration of sensing hardware, signal processing, and machine learning [

74]. Comprehensive surveys highlight that future HAR research must also address emotion recognition, multi-user recognition, and edge AI deployment in real-world contexts [

75].

2.3.8. Real-World Applications and Deployment

Sensor-based HAR has reached practical maturity. In healthcare, wearable HAR achieves >95% sensitivity for fall detection, enabling early intervention for elderly patients [

76]. Fitness trackers like Fitbit and Apple Watch combine accelerometer and heart rate data for reliable workout classification. Smart homes integrate ambient and wearable sensors for activity monitoring under resource constraints [

63]. Industrial deployments monitor ergonomics and safety compliance through continuous sensor-based posture recognition [

77]. Nevertheless, open challenges remain in privacy preservation, cross-domain generalization, and energy-efficient real-time inference [

78].

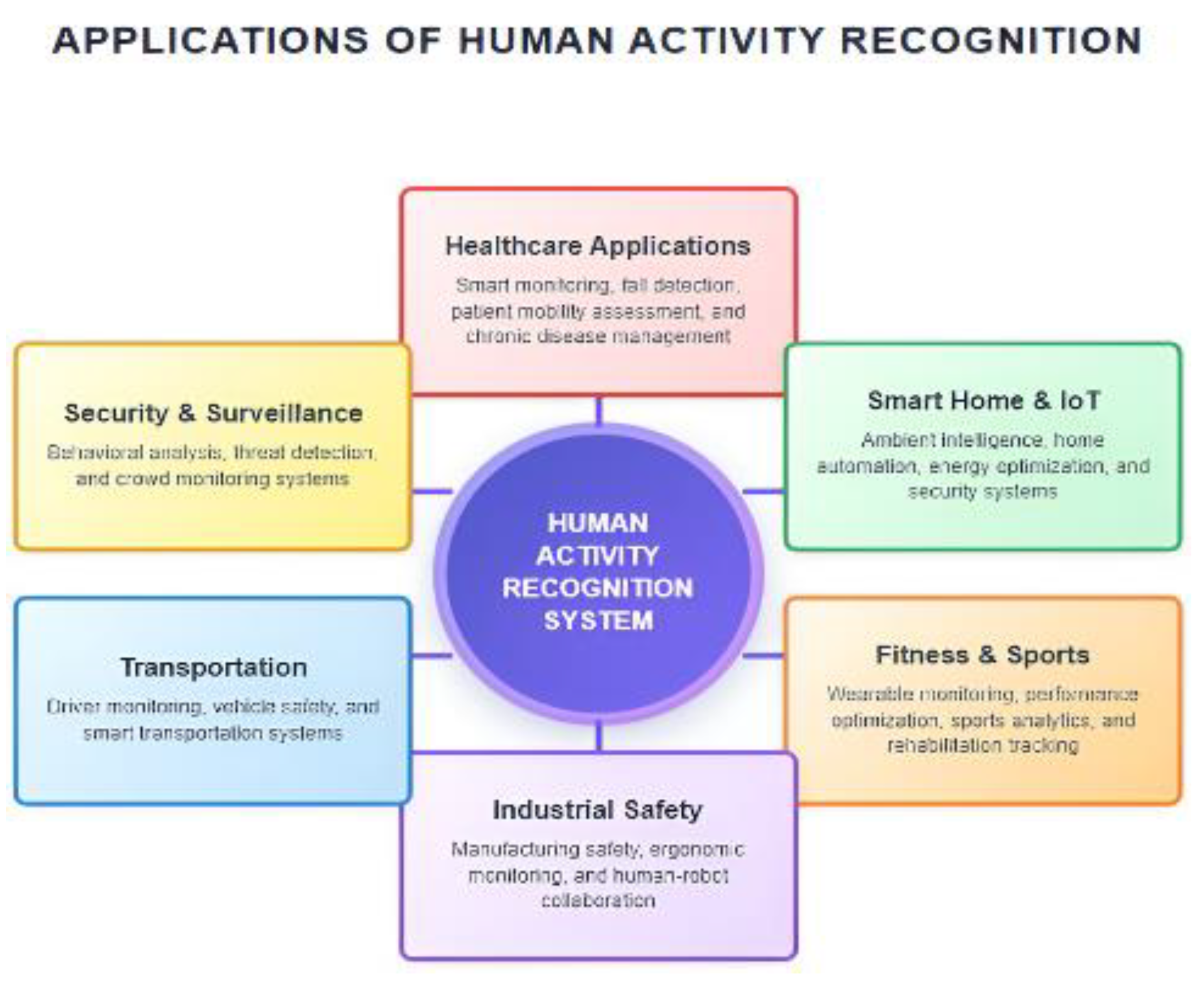

Figure 2.

Applications of Human Activity Recognition System showing various domains including Healthcare, Security & Surveillance, Smart Home & IoT, Transportation, Industrial Safety, and Fitness & Sports.

Figure 2.

Applications of Human Activity Recognition System showing various domains including Healthcare, Security & Surveillance, Smart Home & IoT, Transportation, Industrial Safety, and Fitness & Sports.

3. Application of HAR

3.1. Healthcare Application

3.1.1. Smart Healthcare Monitoring

Healthcare represents the most impactful domain for HAR applications, with recent developments showing remarkable progress in patient monitoring and care delivery. HAR has become one of the most important segments of technology advancement in applications of smart devices and healthcare systems, using data from wearable sensors that capture how human beings move and engage with their surroundings. Current healthcare applications include patient mobility assessment systems for intensive care unit patients using HAR technology to monitor recovery progress, medical emergency detection through hybrid deep CNN and bi-directional LSTM models with wearable sensors for enhanced emergency response systems, and chronic disease management through gait analysis systems for patients with conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy to track disease progression [

79]. Recent innovations in 2024-2025 have introduced AI algorithms analyzing massive amounts of data from wearable devices, enabling healthcare providers to identify patterns and predict health outcomes, while wearable devices with superior signal-to-noise ratios provide activity recognition less susceptible to environmental noise, including specialized eating activity monitoring [

80].

3.1.2. Fall Detection and Elderly Care

Advanced HAR systems in healthcare focus on fall detection for elderly populations, achieving greater than 95% accuracy in real-world deployments. These systems analyze movement patterns, gait stability, and daily activity rhythms to predict health deterioration 48-72 hours before clinical symptoms appear. Elderly care facilities utilize HAR for comprehensive monitoring of residents, detecting falls, tracking mobility changes, and identifying early signs of cognitive decline to enable timely interventions. Telemedicine applications leverage HAR to enable remote patient monitoring, where physicians can track patient recovery and medication adherence through continuous activity analysis, particularly valuable for post-surgical rehabilitation and chronic disease management [

81].

3.2. Smart Home and IoT Integration

3.2.1. Ambient Intelligence and Home Automation

Smart home and IoT integration has become a rapidly expanding application area for HAR, focusing on safety, monitoring, and energy optimization through multiple sensor modalities that create comprehensive activity understanding in residential environments [

82]. Current applications include elderly fall detection systems, energy optimization based on occupancy patterns and behavioral predictions, security systems with behavioral anomaly detection capabilities, and automated home environment control that adapts to resident activities. Modern smart home systems integrate ambient sensors, wearable devices, and smartphone data to create detailed profiles of household activities, enabling predictive automation that anticipates user needs and optimizes resource consumption. These systems can distinguish between multiple household members simultaneously, personalizing environmental controls and monitoring individual health metrics in shared living spaces.

3.2.2. Home Security and Safety

Home security applications use HAR to distinguish between authorized residents and potential intruders through behavioral pattern recognition, while also monitoring for emergency situations such as medical events or accidents. Smart homes monitor cooking activities to provide safety alerts, track hygiene routines, and detect health indicators through activity analysis. Future developments include invisible sensor networks embedded in furniture and flooring, creating seamless activity monitoring without requiring wearable devices through vibration analysis and micro-movement detection [

83].

3.3. Fitness and Sports Analytics

3.3.1. Wearable Fitness Monitoring

Fitness and sports analytics represent a significant application domain where HAR demonstrates practical impact through comprehensive activity monitoring and performance optimization. Modern fitness wearables like Fitbit and Apple Watch combine advanced health tracking with AI-powered insights, monitoring heart rate, sleep patterns, stress levels, and skin temperature, with AI algorithms providing personalized health recommendations based on comprehensive activity analysis [

84]. Current capabilities include real-time workout classification and form correction, performance optimization through detailed biomechanical analysis, injury prevention through movement pattern analysis and risk assessment, and personalized training recommendations based on individual performance data and goals.

3.3.2. Professional Sports and Rehabilitation

Professional sports teams utilize HAR for athlete performance monitoring, training load management, and injury prevention through continuous biomechanical analysis during practice and competition. Rehabilitation centers employ HAR systems to track patient progress during physical therapy, automatically adjusting exercise protocols based on movement quality and recovery indicators [

85]. These applications provide real-time technique correction during sports activities, offering feedback on form, efficiency, and injury risk through computer vision and wearable sensor fusion, enabling coaches to optimize training programs and prevent injuries.

3.4. Industrial and Workplace Safety

3.4.1. Manufacturing and Construction Safety

Industrial and workplace safety applications have demonstrated significant value in protecting workers and optimizing productivity through continuous sensor-based monitoring systems that enhance safety protocols and op- operational efficiency. Current industrial implementations focus on ergonomic posture monitoring in manufacturing environments, fatigue detection in high-risk operations to prevent accidents, safety compliance verification through automated monitoring systems, and productivity analysis through comprehensive activity classification and workflow optimization. Construction sites utilize HAR for worker safety monitoring, detecting unsafe behaviors, monitoring compliance with safety protocols, and predicting potential accident scenarios based on movement patterns and environmental factors.

3.4.2. Human-Robot Collaboration

Manufacturing facilities employ HAR for quality control, monitoring assembly line activities to ensure proper procedures are followed, and optimizing workflow efficiency through detailed activity analysis. Advanced HAR systems enable seamless interaction between humans and robots in manufacturing environments, with robots adapting their behavior based on human activity recognition and intention prediction. Workplace wellness systems monitor stress levels and work-life balance through activity pattern analysis, providing early warning systems for worker well-being issues and automatically suggesting interventions to improve workplace safety and productivity.

3.5. Transportation and Autonomous Systems

3.5.1. Driver Monitoring and Vehicle Safety

Transportation applications focus on driver monitoring, passenger safety, and intelligent vehicle interaction systems that enhance transportation safety and efficiency. Current transportation applications include driver drowsiness detection systems that monitor alertness levels, passenger activity monitoring in public transport for safety and service optimization, emergency response systems in vehicles that automatically detect accidents or medical emergencies, and accessibility support systems that assist passengers with disabilities. These systems analyze driver behavior patterns to predict fatigue, distraction, and impairment, automatically alerting drivers or triggering safety protocols to prevent accidents [

86].

3.6. Security and Surveillance

3.6.1. Behavioral Analysis and Threat Detection

Security and surveillance applications have advanced significantly with recent developments in HAR for behavioral analysis, including novel approaches combining YOLO and LSTM architectures for enhanced human action recognition in video sequences, critical for surveillance and human-computer interaction applications. Current security applications include abnormal behavior detection in public spaces through pattern analysis, sophisticated intrusion detection systems that distinguish between authorized and unauthorized activities, crowd behavior analysis for event management and public safety, and access control systems using gait recognition and movement signatures for identification [

87].

3.6.2. Airport and Public Safety

Airport security systems employ HAR for passenger behavior monitoring, detecting suspicious activities, and enhancing screening processes through behavioral analysis. Public safety applications utilize HAR for monitoring crowd dynamics, detecting potential security threats by analyzing behavioral patterns and individual activity anomalies, and coordinating emergency response systems. These systems provide security monitoring while protecting individual privacy through edge computing-based processing and encrypted behavioral signatures, enabling person identification through unique movement signatures without requiring traditional biometric data collection [

88].

3.7. Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in HAR and Sustainable Systems

HAR has rapidly evolved through the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning, enabling systems to analyze complex human behaviors and environmental interactions across healthcare, smart homes, industry, and security. These advancements parallel broader applications of AI in sustainability and engineering, where data-driven modeling enhances system efficiency and resilience. For instance, machine learning has been used to assess the effects of temperature and rainfall on concrete pavement performance [

89] and to optimize sustainable vertical farming systems for improved resource utilization [

90]. Similarly, neural networks have been applied to predict solid waste generation and biogas production, showcasing the predictive power of AI in environmental management [

91,

92,

93]. Other studies, including AI-based photovoltaic design and integrated solid waste management models, further highlight how intelligent computation contributes to both environmental sustainability and technological innovation [

94,

95]. Overall, HAR exemplifies the growing convergence of AI with real-world systems aimed at creating adaptive, efficient, and human-centered solutions.

4. Emerging Technologies and Techniques

The HAR landscape continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in computational methods and novel sensing approaches. This section examines cutting-edge techniques that are reshaping activity recognition.

4.1. Federated Learning for HAR

Privacy concerns increasingly drive the adoption of federated learning approaches in HAR applications. Federated learning enables collaborative model training while keeping raw data on individual devices. Recent federated HAR frameworks address unique challenges of activity recognition across heterogeneous devices and user populations. FedHAR introduces personalized federated learning that adapts global models to individual user characteristics while preserving privacy [

96]. Device heterogeneity poses significant challenges, with different smartphones and wearables exhibiting varying sensor characteristics. Advanced federated algorithms now incorporate device-aware aggregation strategies that weight contributions based on device reliability and data quality metrics.

4.2. Neural Architecture Search and Optimization

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) automates the design of optimal network architectures for specific HAR tasks and deployment constraints. Differentiable architecture search methods like DARTS have been adapted for HAR applications, enabling efficient exploration of CNN and RNN combinations for sensor-based recognition. Hardware NAS represents a particularly important development for edge HAR deployment, incorporating hardware-specific constraints during architecture search. Recent work demonstrates architectures optimized for smartphone deployment that achieves 40% faster inference while maintaining comparable accuracy to traditional designs [

97].

4.3. Neuromorphic Computing

Neuromorphic computing architectures offer promising advantages for edge HAR deployment. These event-driven processors consume power only when processing information, making them ideal for battery-constrained wearable devices. Spiking neural networks (SNNs) naturally process temporal sensor data through spike-timing-dependent plasticity mechanisms. Intel’s Loihi and other neuromorphic processors demonstrate real-time HAR capabilities with power consumption measured in milliwatts rather than watts [

98].

5. Future Directions

5.1. Multimodal Integration, Personalization, Edge Computing, and Explainable HAR

Future HAR systems will increasingly leverage complementary information from diverse sensing modalities. The integration of traditional inertial sensors with emerging modalities such as radar, LiDAR, and acoustic sensors creates opportunities for more comprehensive activity understanding. Radar-based HAR shows particular promise for privacy-preserving applications, capturing human motion through radio frequency reflections without recording visual appearance [

99]. Attention-based fusion mechanisms will dynamically weight different modalities based on their reliability in specific contexts, creating robust systems that gracefully degrade when individual sensors fail.

Future systems will incorporate sophisticated personalization mechanisms that adapt to individual users while maintaining generalization capabilities. Few-shot learning approaches will enable rapid personalization with minimal user-specific training data. The trend toward edge computing will intensify as privacy concerns drive processing closer to data sources. Model compression techniques specifically designed for HAR will achieve dramatic reductions in computational requirements while maintaining recognition accuracy through knowledge distillation and dynamic neural networks.

As HAR systems are deployed in critical applications such as healthcare monitoring, explainability becomes paramount. Future systems will provide clear, interpretable explanations for recognition decisions through visual explanation techniques and uncertainty quantification. Adversarial robustness will address the vulnerability of deep learning HAR systems to input perturbations, ensuring reliability in security-critical applications.

6. Conclusion

This comprehensive survey has examined the current state and future directions of Human Activity Recognition through deep learning advancement and practical deployment considerations. HAR has evolved from a niche research area dependent on handcrafted features to a mature field leveraging sophisticated deep learning architectures that achieve remarkable accuracy across diverse applications. Vision-based approaches continue to dominate in raw recognition accuracy, particularly for complex activities in controlled environments. Skeleton-based methods have emerged as a compelling middle ground, offering privacy preservation while maintaining strong performance through graph neural networks. Sensor-based HAR has proven valuable in real-world deployment scenarios requiring continuous, unobtrusive monitoring.

The application domains examined demonstrate HAR’s growing practical impact. Healthcare applications show particular promise, with fall detection systems achieving over 95% accuracy in real-world deployments. Smart home integration has moved beyond proof-of-concept to commercial deployment, while industrial applications demonstrate clear value in worker safety assessment.

Emerging technologies address many practical deployment barriers. Self-supervised learning tackles limited labeled data challenges, federated learning enables privacy-preserving training, and neuromorphic computing offers energy-efficient edge deployment. These advances collectively enable more sophisticated and deployable HAR systems.

Future trends will likely define the next generation of HAR systems through multimodal integration, personalization capabilities, and edge AI deployment driven by privacy and latency requirements. The field faces persistent challenges in cross-domain generalization, energy efficiency, and explainability that require continued research attention.

Despite these challenges, the trajectory appears highly promising. The convergence of improved algorithms, specialized hardware, and growing application demand creates favorable conditions for continued advancement. The societal impact extends beyond technical metrics to encompass improved healthcare outcomes, enhanced industrial safety, and greater independence for elderly populations. Future research should prioritize robust, generalizable, and explainable HAR systems that operate reliably across diverse real-world conditions while emphasizing interdisciplinary collaboration to ensure technical advances translate into practical human benefits.

References

- Sargano, B.; Angelov, P.; Habib, Z. A comprehensive review on handcrafted and learning-based action representation approaches for human activity recognition. Applied Sciences 2017, vol. 7(no. 1), 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Shao, L.; Xie, J.; Fang, Y. From hand-crafted to learned representations for human action recognition: A survey. Image and Vision Computing 2016, vol. 55, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qiao, Y.; Tang, X. Action recognition with trajectory-pooled deep-convolutional descriptors. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015; pp. 4305–4314. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, vol. 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang. A review on 3d convolutional neural network. 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Power, Electronics and Computer Applications (ICPECA), 2023; IEEE; pp. 1204–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. M. Recurrent neural networks (RNNS): A gentle introduction and overview. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.05911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves. Long short-term memory. In Supervised sequence labelling with recurrent neural networks; 2012; pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Souza, A.; Zhang, T.; Fifty, C.; Yu, T.; Weinberger, K. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. International Conference on machine learning. Pmlr, 2019; pp. 6861–6871. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.; Xiong, Y.; Lin, D. Spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018; vol. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M. T.; Acquaah, Y. T.; Roy, K. Image-based human action recognition with transfer learning using grad-cam for visualization. IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations, 2024; Springer; pp. 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. P.; Sharma, M. K.; Lay-Ekuakille, A.; Gangwar, D.; Gupta, S. Deep convlstm with self-attention for human activity decoding using wearable sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, vol. 21(no. 6), 8575–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; An, X.; Liu, Q. Multi-sensor data fusion and cnn-lstm model for human activity recognition system. Sensors 2023, vol. 23(no. 10), 4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; Chi, H.-G.; Huang, Q.; Ramani, K. In-fogcn++: Learning representation by predicting the future for online skeleton-based action recognition. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. 2005 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR’05) 2005, vol. 1. IEEE, 886–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, M. A. R. Motion history images for action recognition and understanding; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shuvo, M. M. H.; Ahmed, N.; Nouduri, K.; Palaniappan, K. “A hybrid approach for human activity recognition with support vector machine and 1D convolutional neural network,” in 2020 IEEE Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop (AIPR); IEEE, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Guendel, R. G.; Yarovoy, A.; Fioranelli, F. Continuous human activity recognition with distributed radar sensor networks and CNN–RNN architectures. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, vol. 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, R. A survey on vision-based human action recognition. Image and vision computing 2010, vol. 28(no. 6), 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Lai, A. A survey on still image-based human action recognition. Pattern Recognition 2014, vol. 47(no. 10), 3343–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Mondal, R.; Singh, P. K.; Sarkar, R.; Bhattacharjee, D. Transfer learning with fine tuning for human action recognition from still images. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, vol. 80(no. 13), 20 547–20 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M. T.; Dasgupta, S.; Roy, K. Optimizing human action recognition in still images using deep learning models and grad-cam++ for visualization. 2024 27th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), 2024; IEEE; pp. 2375–2380. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Pang, W.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Li, B. Deep ensemble learning for human action recognition in still images. Complexity 2020, vol. 2020(no. 1), 9428612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Roy; Kundu, R.; Singh, P. K.; Bhateja, V.; Sarkar, R. An ensemble approach for still image-based human action recognition. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, vol. 34(no. 21), 19 269–19 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-h.; Cho, D. Aware action recognition using skeleton-based features from still images. Electronics 2021, vol. 10(no. 9), 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. H.; Khoudour, L.; Crouzil, A.; Zegers, P.; Velastin, S. A. Video-based human action recognition using deep learning: a review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.03775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, A.; Chen, C.; Li, M. Aim: Adapting image models for efficient video action recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, K. Muhammad; Ding, W.; Palade, V.; Haq, I. U.; Baik, S. W. Efficient activity recognition using lightweight CNN and DS-GRU network for surveillance applications. Applied Soft Computing 2021, vol. 103, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, G.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C.; Zisserman, A. Synthetic humans for action recognition from unseen viewpoints. International Journal of Computer Vision 2021, vol. 129(no. 7), 2264–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terreran, M.; Barcellona, L.; Ghidoni, S. A general skeleton-based action and gesture recognition framework for human–robot collaboration. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2023, vol. 170, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Chen, C.-C.; Aggarwal, J. K. View invariant human action recognition using histograms of 3d joints. 2012 IEEE Computer Society conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2012; IEEE; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, J. Mining action- let ensemble for action recognition with depth cameras. 2012 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2012; IEEE; pp. 1290–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, L. Hierarchical recurrent neural network for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015; pp. 1110–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Shahroudy, A.; Xu, D.; Kot, A. C.; Wang, G. Skeleton-based action recognition using spatio-temporal LSTM network with trust gates. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2017, vol. 40(no. 12), 3007–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-based action recognition with directed graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 7912–7921. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Cheng, J.; Lu, H. Skeleton-based action recognition with shift graph convolutional network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Li, B.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W. Channel-wise topology refinement graph convolution for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 13 359–13 368. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.-F.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, C.; Wang, L. Stronger, faster and more explainable: A graph con- volutional baseline for skeleton-based action recogni- tion. proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on multimedia, 2020; pp. 1625–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.-L.; Ong, L.-Y.; Leow, M.-C. A systematic literature review of optimization methods in skeleton-based human action recognition. IEEE Access, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, G.; Yuan, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, W. Graph convolutional network with structure pooling and joint-wise channel attention for action recognition. Pattern Recognition 2020, vol. 103, 107321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xu, K.; Zhu, B.; Jiang, X.; Sun, T. Deformable graph convolutional transformer for skeleton-based action recognition. Applied Intelligence 2023, vol. 53(no. 12), 15 390–15 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, W. Disentangling and unifying graph convolutions for skeleton-based action recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2020; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Lin, D. Pyskl: Towards good practices for skeleton action recognition. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2022; pp. 7351–7354. [Google Scholar]

- Khowaja, S. A.; Lee, S.-L. Skeleton-based human action recognition with sequential convolutional-LSTM networks and fusion strategies. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2022, vol. 13(no. 8), 3729–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Simon, T.; Wei, S.-E.; Sheikh, Y. Real-time multi-person 2d pose estimation using part affinity fields. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017; pp. 7291–7299. [Google Scholar]

- Pavllo, D.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Grangier, D.; Auli, M. 3d human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 7753–7762. [Google Scholar]

- Sárándi, T. Linder; Arras, K. O.; Leibe, B. Me-trabs: metric-scale truncation-robust heatmaps for absolute 3d human pose estimation. IEEE Transactions on Biometrics, Behavior, and Identity Science 2020, vol. 3(no. 1), 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlakos, G.; Choutas, V.; Ghorbani, N.; Bolkart, T.; Osman, A. A.; Tzionas, D.; Black, M. J. Expres- sive body capture: 3d hands, face, and body from a single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019; pp. 10 975–10 985. [Google Scholar]

- Terreran, M.; Lazzaretto, M.; Ghidoni, S. Skeleton-based action and gesture recognition for human-robot collaboration. International Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems, 2022; Springer; pp. 29–45. [Google Scholar]

- Plizzari; Cannici, M.; Matteucci, M. Skeleton-based action recognition via spatial and temporal transformer networks. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2021, vol. 208, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhong, J.; Lian, D.; Cao, W. An adaptively multi-correlations aggregation network for skeleton-based motion recognition. Scientific Reports 2023, vol. 13(no. 1), 19138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, H.; Velastin, S. A.; Meza, I.; Fabregas, E.; Makris, D.; Farias, G. Fall detection and activity recognition using human skeleton features. IEEE Access 2021, vol. 9, 33 532–33 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi; Thomas, U. “Skeleton-based action recognition for human-robot interaction using self-attention mechanism,” in 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021); IEEE; Volume 2021, pp. 1–8.

- Li, Z.; Li, D. Action recognition of construction workers under occlusion. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, vol. 45, 103352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobdeh, S. B.; Yamaghani, M. R.; Sareshkeh, S. K. Basketball action recognition based on the combination of yolo and a deep fuzzy LSTM network: S.B. Khobdeh et al. The Journal of Supercomputing 2024, vol. 80(no. 3), 3528–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L. M.; Min, K.; Wang, H.; Piran, M. J.; Lee, C. H.; Moon, H. Sensor-based and vision-based human activity recognition: A comprehensive survey. Pattern Recognition 2020, vol. 108, 107561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha; Rajak, S.; Saha, J.; Chowdhury, C. A survey of machine learning and meta-heuristics approaches for sensor-based human activity recognition systems. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2024, vol. 15, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, N. T. H.; Han, D. S. Hihar: A hierarchical hybrid deep learning architecture for wearable sensor-based human activity recognition. IEEE Access 2021, vol. 9, 145 271–145 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.; Min, F.; He, J.; Song, A. Deep neural networks for sensor-based human activity recognition using selective kernel convolution. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, vol. 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheikh, M. A.; Selim, A.; Niyato, D.; Doyle, L.; Lin, S.; Tan, H.-P. Deep activity recognition models with triaxial accelerometers. AAAI workshop: artificial intelligence applied to assistive technologies and smart environments, 2016; vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Min, F.; Song, A. Channel-equalization-har: A light-weight convolutional neural network for wearable sensor-based human activity recognition. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing 2022, vol. 22(no. 9), 5064–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Q.; Tang, Y.; Hu, G. Rephar: Decoupling networks with accuracy-speed tradeoff for sensor-based human activity recognition. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, vol. 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Tian, L.; Tu, P.; Cao, T.; An, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, S. Wearable sensor-based human activity recognition using hybrid deep learning techniques. Security and Communication Networks 2020, vol. 2020(no. 1), 2132138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Tang, H.; Haque, S. T.; Yan, Y.; Ngu, A. H. A survey on multimodal wearable sensor-based human action recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Rajasekhar, H.; Zhang, L.; Bruda, E.; Kwon, H.; Plötz, T. Imugpt 2.0: Language-based cross modality transfer for sensor-based human activity recognition. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2024, vol. 8(no. 3), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerla, N. Y.; Halloran, S.; Plötz, T. Deep, convolutional, and recurrent models for human activity recognition using wearables. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1604.08880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plötz, T. “If only we had more data!: Sensor-based human activity recognition in challenging scenarios,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops and other Affiliated Events (PerCom Workshops); IEEE, 2023; pp. 565–570. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, S.; Panigrahi, C. R.; Pati, B.; Nanda, S.; Hsieh, M. Y. Comparative analysis of har datasets using classification algorithms. Computer Science and Information Systems 2022, vol. 19(no. 1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss; Stricker, D. Introducing a new benchmarked dataset for activity monitoring. 2012 16th International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 2012; IEEE; pp. 108–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Sawchuk, A. A. Usc-had: A daily activity dataset for ubiquitous activity recognition using wearable sensors. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM conference on ubiquitous computing, 2012; pp. 1036–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberto, M.; Fortes Rey, V.; Calatroni, A.; Lukowicz, P.; Roggen, D. Opportunity++: A multimodal dataset for video-and wearable, object and ambient sensors-based human activity recognition. Frontiers in Computer Science 2021, vol. 3, 792065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micucci; Mobilio, M.; Napoletano, P. Unimib shar: A dataset for human activity recognition using acceleration data from smartphones. Applied Sciences 2017, vol. 7(no. 10), 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, M.; Clegg, R. G.; Cavallaro, A.; Haddadi, H. Protecting sensory data against sensitive inferences. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Privacy by Design in Distributed Systems, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- De-La-Hoz-Franco; Ariza-Colpas, P.; Quero, J. M.; Espinilla, M. Sensor-based datasets for human activity recognition–a systematic review of literature. IEEE Access 2018, vol. 6, 59 192–59 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hartmann, Y.; Schultz, T. A practical wearable sensor-based human activity recognition research pipeline. In in Healthinf; 2022; pp. 847–856. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Chauhan, S.; Awasthi, L. K. Human activity recognition (HAR) using deep learning: Review, methodologies, progress and future research directions. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, vol. 31(no. 1), 179–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, L.; Vargas Toro, A.; Konietzny, S.; Rüping, S.; Schäpers, B.; Steinböck, M.; Krewer, C.; Müller, F.; Güttler, J.; Bock, T. Advanced sensing and human activity recognition in early intervention and rehabilitation of elderly people. Journal of Population Ageing 2020, vol. 13(no. 2), 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, S.; Rey, V. F.; Lukowicz, P. “Wearable sensor-based human activity recognition for worker safety in manufacturing line,” in Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing: Enabling Intelligent, Flexible and Cost-Effective Production Through AI; Springer Nature Switzerland Cham, 2023; pp. 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Antar, D.; Ahmed, M.; Ahad, M. A. R. Chal- lenges in sensor-based human activity recognition and a comparative analysis of benchmark datasets: A review. 2019 Joint 8th International Conference on Informatics, Electronics & Vision (ICIEV) and 2019 3rd International Conference on Imaging, Vision & Pattern Recognition (ICIVPR), 2019; IEEE; pp. 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli, N. A.; Natarajan, S.; Alharbi, A. H.; Kannan, S.; Khafaga, D. S.; Raju, S. K.; Eid, M. M.; El-Kenawy, E.-S. M. Enhanced human activity recognition in medical emergencies using a hybrid deep CNN and bi-directional LSTM model with wearable sensors. Scientific Reports 2024, vol. 14(no. 1), 30979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi; Khateeb, K.; Brahimi, T.; Sarirete, A. Human activity recognition using machine learning methods in a smart healthcare environment. In Innovation in health informatics; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Z. A.; Sohn, W. Abnormal human activity recognition system based on r-transform and kernel discriminant technique for elderly home care. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2012, vol. 57(no. 4), 1843–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Blasch, E.; Qu, Q. Future outdoor safety monitoring: Integrating human activity recognition with the internet of physical–virtual things. Applied Sciences 2025, vol. 15(no. 7), 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbò, L.; Carotenuto, R.; Della Corte, F. An overview of indoor localization system for human activity recognition (har) in healthcare. Sensors 2022, vol. 22(no. 21), 8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukan, N.; Mohine, S.; Mondal, A.; Manikan-dan, M. S.; Pachori, R. B. Convolutional neural network-based human activity recognition for edge fitness and context-aware health monitoring devices. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, vol. 22(no. 22), 21 816–21 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Convolutional neural network-based human movement recognition algorithm in sports analysis. Frontiers in psychology 2021, vol. 12, 663359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Lv, C.; Wang, H.; Cao, D.; Velenis, E.; Wang, F. Y. Driver activity recognition for intelligent vehicles: A deep learning approach. IEEE trans- actions on Vehicular Technology 2019, vol. 68(no. 6), 5379–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achar, S.; Faruqui, N.; Whaiduzzaman, M.; Awajan, A.; Alazab, M. Cyber-physical system security based on human activity recognition through IoT cloud computing. Electronics 2023, vol. 12(no. 8), 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaraqe, M.; Elzein, A.; Basaran, E.; Yang, Y.; Varghese, E. B.; Costandi, W.; Rizk, J.; Alam, N. Pub- licvision: A secure smart surveillance system for crowd behavior recognition. IEEE Access 2024, vol. 12, 26 474–26 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argha, D. B. P.; Ahmed, M. A. A Machine Learning Approach to Understand the Impact of Temperature and Rainfall Change on Concrete Pavement Performance Based on LTPP Data. SVU-International Journal of Engineering Sciences and Applications 2024, vol. 5(no. 1), 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, H.; Argha, D. B. P.; Ahmed, M. A. Artificial Intelligence in Sustainable Vertical Farming. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Md. A.; Hossain, M.; Islam, M. Prediction of Solid Waste Generation Rate and Determination of Future Waste Characteristics at South-western Region of Bangladesh Using Artificial Neural Network; KUET: Khulna, Bangladesh; WasteSafe 2017, KUET: Khulna, Bangladesh, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.; Ahmed, Md. A.; Shah, Md. H. Biogas generation from kitchen and vegetable waste in replacement of traditional method and its future forecasting by using ARIMA model. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2021, vol. 3(no. 2), 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Md. A.; Roy, P.; Bari, A.; Azad, M. Conversion of Cow Dung to Biogas as Renewable Energy Through Mesophilic Anaerobic Digestion by Using Silica Gel as Catalyst, 5th ed.; ICMERE 2019, Chittagong University of Engineering & Technology (CUET): Chittagong, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Argha, D. B. P.; Ahmed, M. A. Design of Photovoltaic System for Green Manufacturing by using Statistical Design of Experiments. 2023, Preprints, 2023101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. A.; Chakrabarti, S. D. Scenario of Existing Solid Waste Management Practices and Integrated Solid Waste Management Model for Developing Country with Reference to Jhenaidah Municipality, Bangladesh. presented at the 4th International Conference on Civil Engineering for Sustainable Development (ICCESD 2018), Khulna, Bangladesh; KUET, Feb. 2018; Department of Civil Engg. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Xu, X.; Xing, H.; Song, F.; Wang, X.; Zhao, B. A federated learning system with enhanced feature extraction for human activity recognition. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, vol. 229, 107338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Lv, T.; Jin, L.; He, M. Har-nas: Human activity recognition based on automatic neural architecture search using evolutionary algorithms. Sensors 2021, vol. 21(no. 20), 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]