3.3. Semantic State Vector Obtaining as a Dimension Reduction Technique

The task of dimensionality reduction in the context of RUL forecasting involves converting data from working cycles by transforming the duration into a fixed-size semantic representation. The input data for the working cycles is presented as a matrix, where n represents the number of parameter of the monitored equipment and m represents the duration of each working cycle.

The dimension of the resulting vector, k, is arbitrarily determined based on the specific problem being addressed, the available dataset, and the application domain, and can be adjusted to minimize prediction errors.

In general, the individual elements of the semantic state vector, denoted by , of length k, do not have an inherent physical significance, although they can be utilized to analyze the dynamic behavior of a system’s condition.

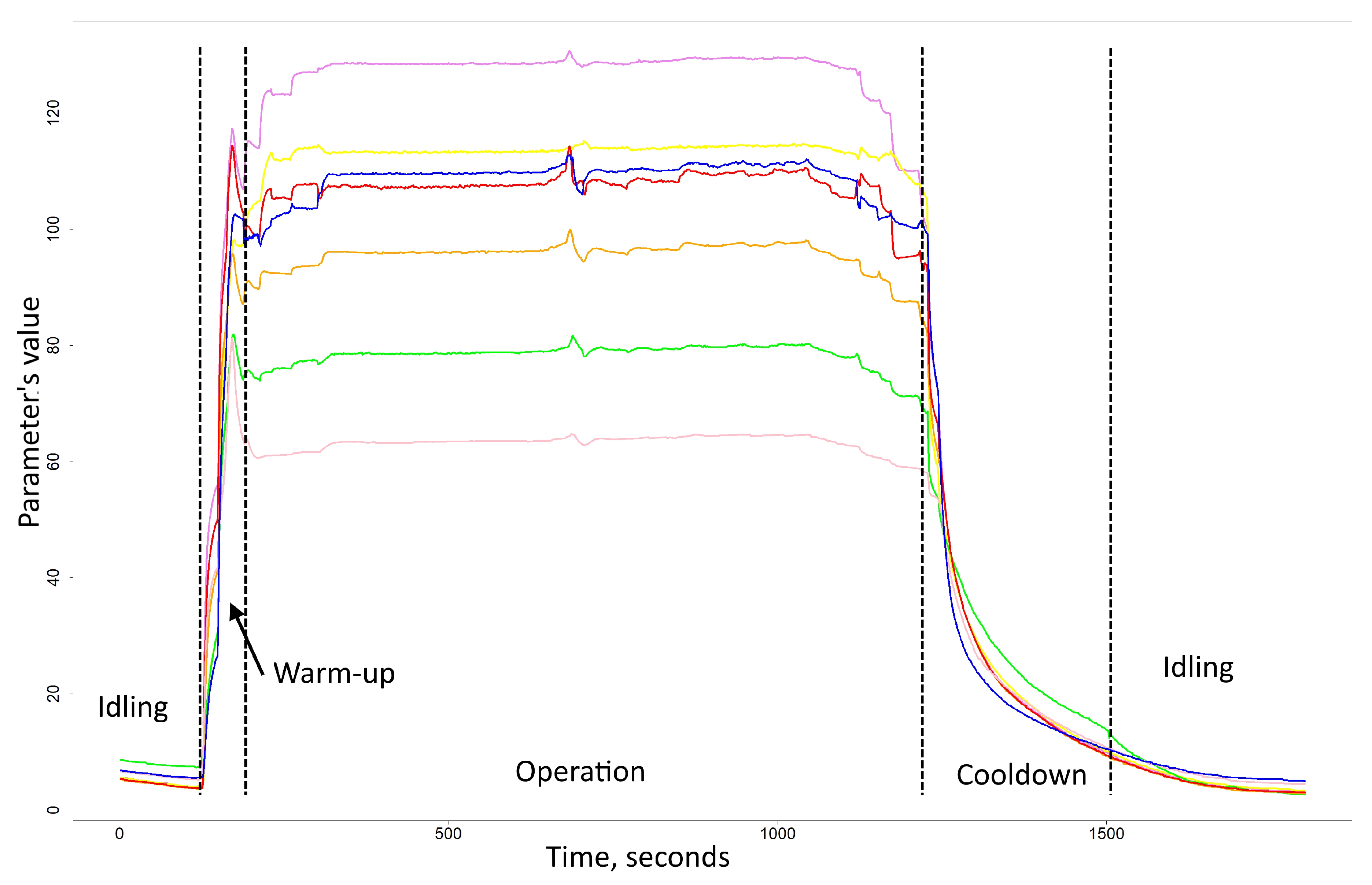

The nature of the data of a working cycle introduces additional challenges in its analysis. The typical working cycle of the equipment under consideration, a turbine engine as an integrated part of a cyber-physical system, comprises three stages: warm-up, operation under load, and cool-down (purge). Existing methods for dimensionality reduction employ heuristics, such as averaging, maximum, and minimum values, for the measured parameters [

36]

A limitation of this approach is that heating and cooling data cannot be utilized for analysis, despite containing important information regarding the technical condition. Additionally, the use of heuristic methods necessitates additional efforts from experts to select the optimal heuristics and parameters.

The use of more sophisticated deep machine learning models could address the limitations of current models and provide the following benefits:

Automation of the process for creating semantic state vectors, eliminating the need for heuristics and manual data manipulation.

Ability to utilize all data from the whole working cycle, rather than just data from under load conditions, enhancing accuracy.

Improved accuracy in the final RUL forecast by considering conditions during startup, warm-up, and purge periods.

3.4. A Method’S Description

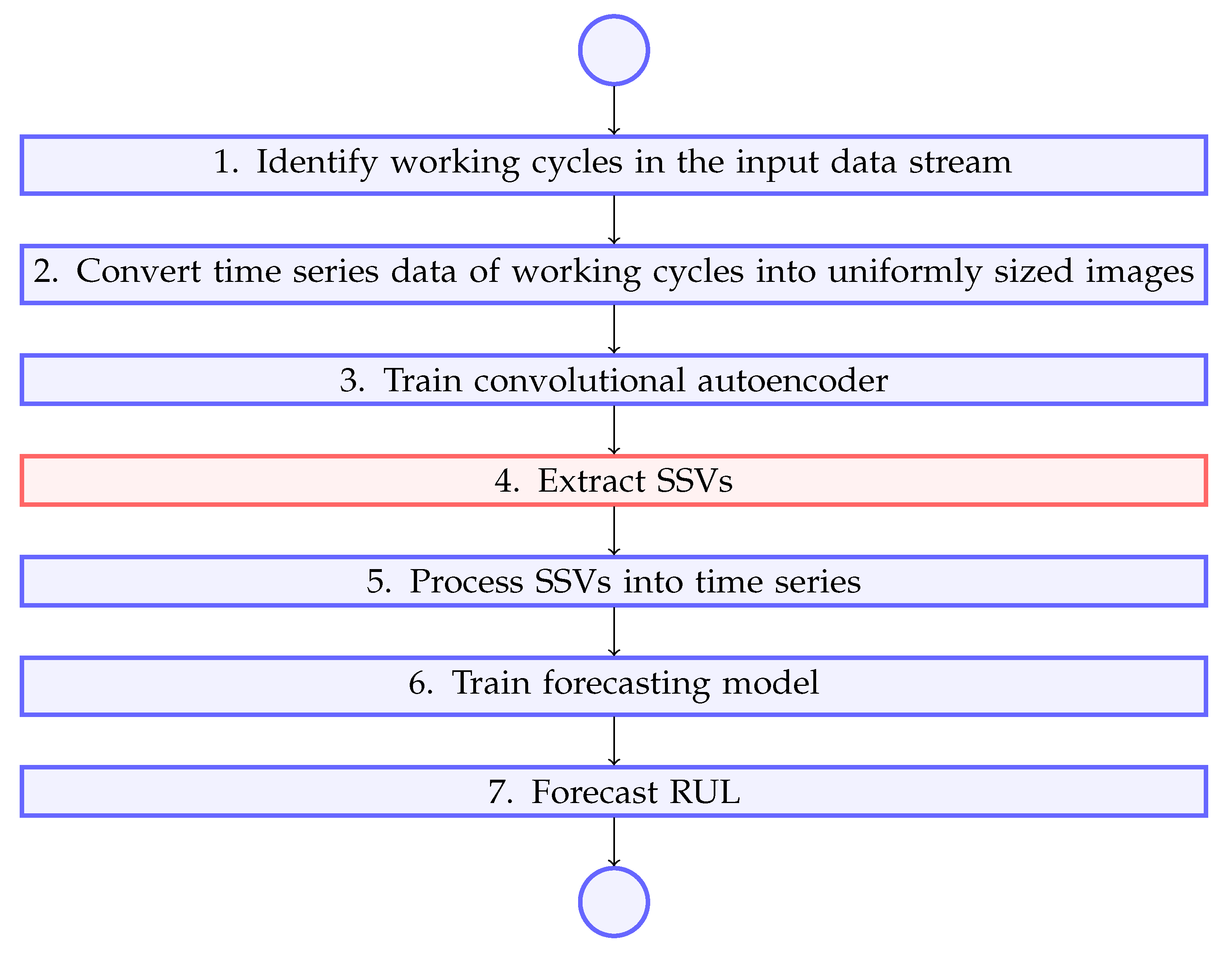

Figure 2 shows the general overview of the proposed method.

Input: a continuous stream of data from the sensors of equipment represented as a multivariate time series. The stream has multiple variables, each one of which corresponds to a measured parameter of equipment. The number of parameters is represented as .

Output: forecast of the remaining useful life of a piece of equipment built upon extracted from working cycles semantic state vectors.

Let’s look at each step of the method in detail and explain them.

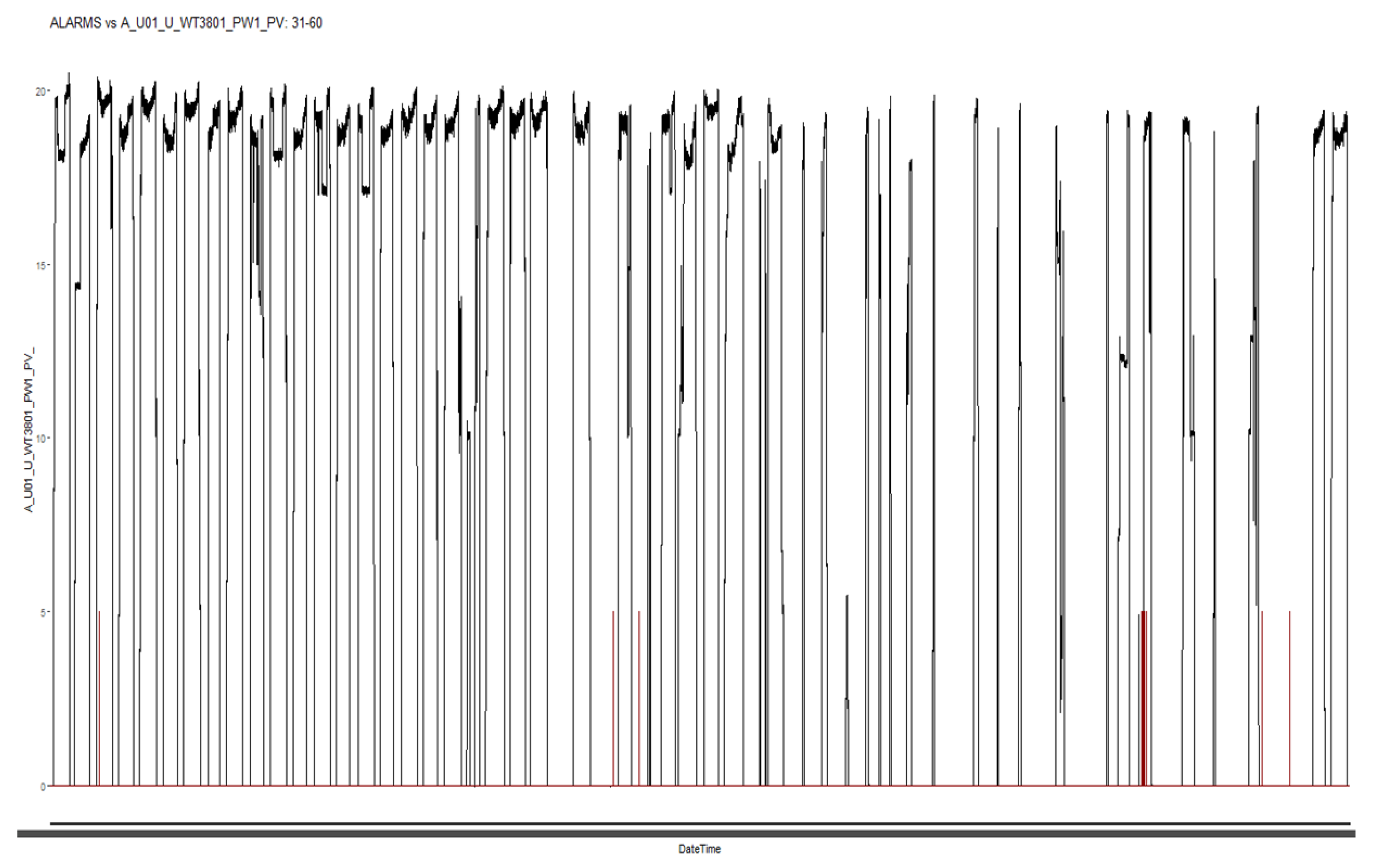

The first step is to extract working cycles from the input data stream. Extraction procedure depends on available data. Measurable inputs, outputs of equipment, control signals or parameters of equipment can be used to identify working cycles. These parameters have to have different values during periods of idling and operation. In general, to distinguish between idling (

I) - a state in which no useful output is produced and operation (

O) - when equipment produces a useful output, we need to define a discrete function

as following:

which can be applied to every single data point

of the input data stream to identify whether equipment was idling or in operation at the time

i.

When observed variables change gradually between two steady states of idling and operation, we can further split the working cycle into periods of rising value (

R), steady operation and decreasing value (

D). For example, if we measure the temperature of equipment or one of its systems, these periods can be called warm-ups and cooldowns. Depending on the nature of the equipment, these periods of unsteady operation can be assigned either as a part of idling or a working cycle. In the current paper we assume that these periods are a part of a working cycle. Then an extended function

can be defined as following:

Afterwards, prolonged periods of continuous operation separated by prolonged periods of continuous idle can be identified as working cycles. Then we can take each working cycle and create a separate time series from its data.

After performing this step we’re left with a set of time series, each one of which is representing a single working cycle from the start to the end.

The second step is to convert these time series into a set of uniformly sized images.

Firstly, all data is normalized to the range [0;1] using the following formula:

Normalization is handled per parameter, which means that for each parameter we determine it’s own and values, which helps to properly scale parameters that have different ranges of values without parameters affecting each other.

After that, data arrays are converted into images with a single channel (black and white), while retaining the dimensions of a source time series. Thus, one pixel in the resulting image corresponds to one value of the measured working cycle parameter. For better visualization, a filter can be applied that adds a color palette to a black and white image.

After the conversion, we get images of different dimensions, which corresponds to different working cycle lengths. At the same time, n remains the same for all images, since the number of measured parameters of the equipment is fixed, and only the duration of a working cycle m changes.

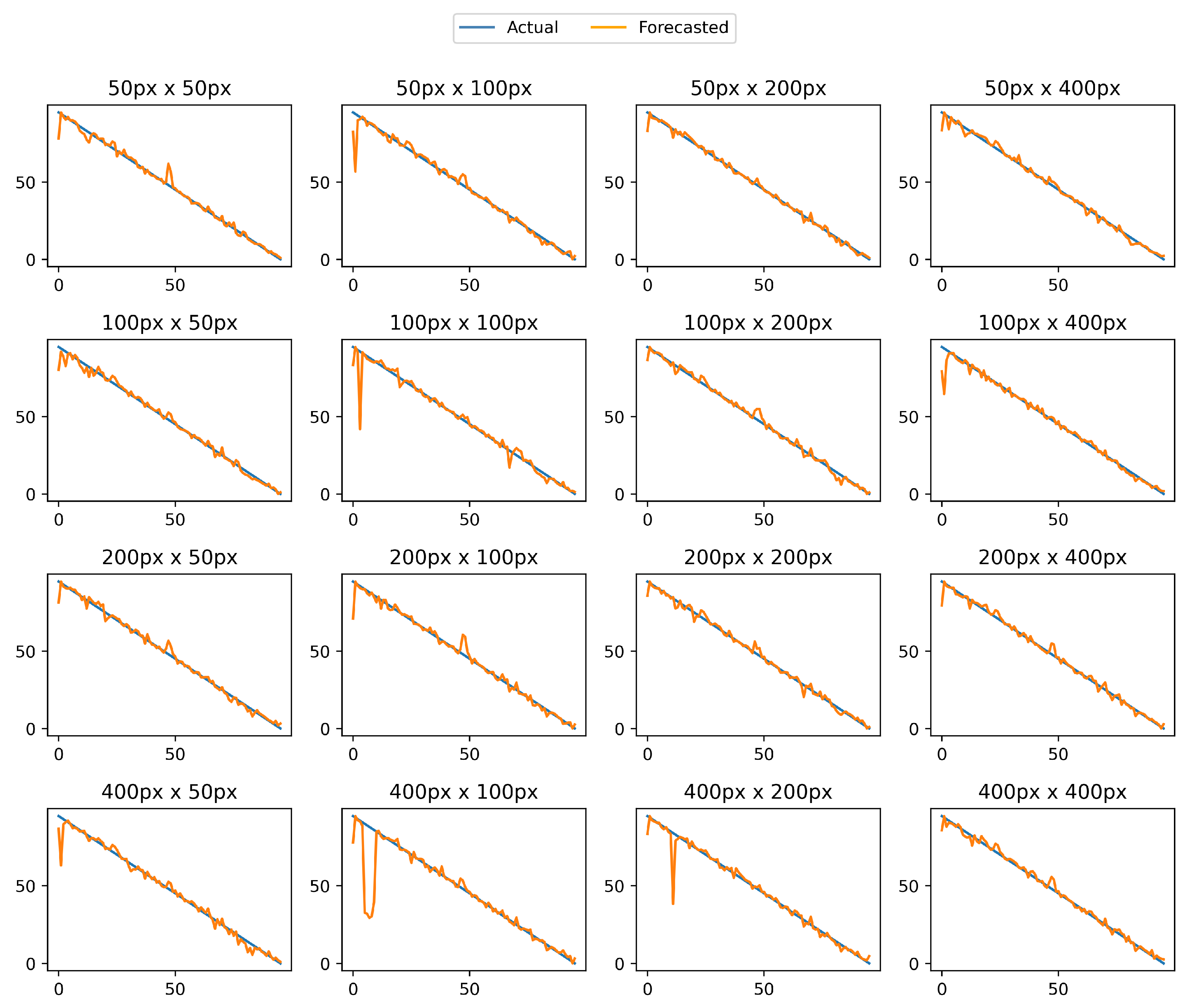

The second step is to convert the images to a single size. This is necessary for the next step – training of the autoencoder. The size is selected individually for each data sample. Images are converted to a single size.

On the next step the structure of a convolutional autoencoder is defined and then it is trained. The autoencoder consists, in the following order, of several sequentially alternating layers of convolution and pooling, a dropout layer, and several consecutive alternating layers of convolution and upsampling. The output from the autoencoder is taken from the last convolution layer before the dropout. Training is performed on the entire data sample.

Table 1 presents an architecture of convolutional autoencoder.

Having trained the autoencoder, we proceed to the step of forming semantic state vectors. To do this, we run all the data of the working cycles through the autoencoder and for each take the output of the intermediate layer specified earlier. Separately, it should be noted that this step uses the same data as when training the autoencoder, because: (i) the architecture of the autoencoder implies pre-known and matching input and output data, which makes it possible to use the same data sample for training and generating output data; (ii) the training time of the autoencoder is negligible compared to the frequency of incoming input data (equipment’s working cycles), so that when new data arrives, the autoencoder can be retrained and the semantic state vector is rebuilt for each of the working cycles without significant time delays; (iii) the data set used for the study is insufficient for a full-fledged process. cross-validation. For these reasons, overfitting the model on the training sample is not an obstacle. If more data is available, cross-validation can be applied to increase the robustness of the autoencoder.

The output of the intermediate convolution layer is a three-dimensional tensor. To get a vector, we have to reduce the number of dimensions by two. The first step is to drop the third dimension. To do this, the sum function is applied over the third dimension. Then sigmoid activation function is applied to the result sum. The second step is to flatten the resulting two-dimensional tensor into a vector.

The result of this step is a sample containing semantic state vectors for each of the working cycles of the equipment.

Fifth step includes formation of time series from semantic state vectors. Firstly, all SSVs are combined into a single time series. Then the smoothing using moving average is applied.

After processing the time series, a training set is created using the sliding window technique. For input data

for time point

i the procedure is as follows. We take

w preceding data points from time series which we later group into a matrix. Then the matrix is flattened into a vector as shown in formula:

In the sixth step, the forecasting model is trained. K-fold cross-validation is used to eliminate potential inaccuracies. Since the amount of training data is relatively small, it is paramount to distribute RUL values across folds as evenly as possible. To achieve this, the approach where data points are staggered across folds is used. In this approach, belonging of a data point

i to a specific fold

k is denoted as

and is described by the following function:

where is the RUL value of the data point i, k is the number of folds.

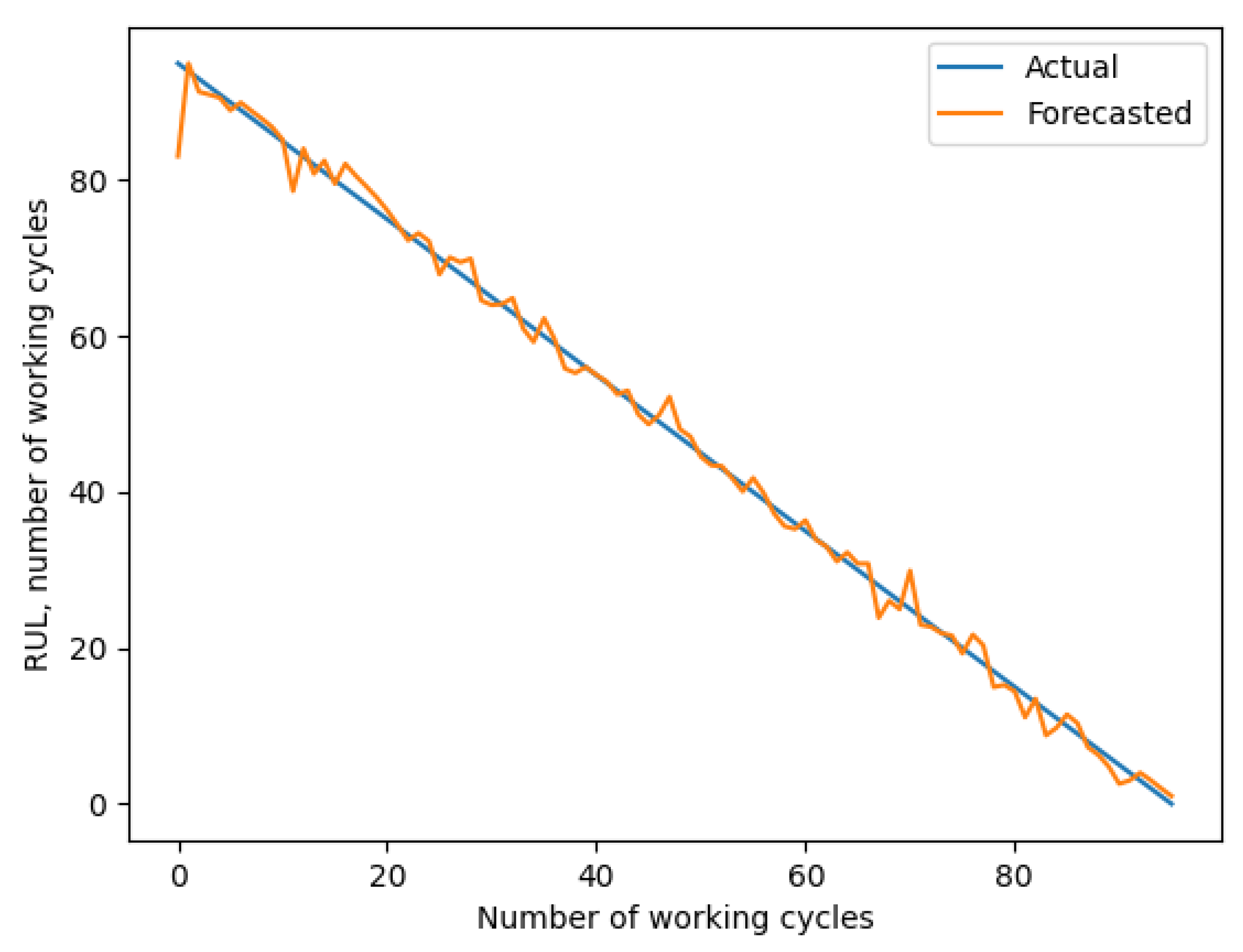

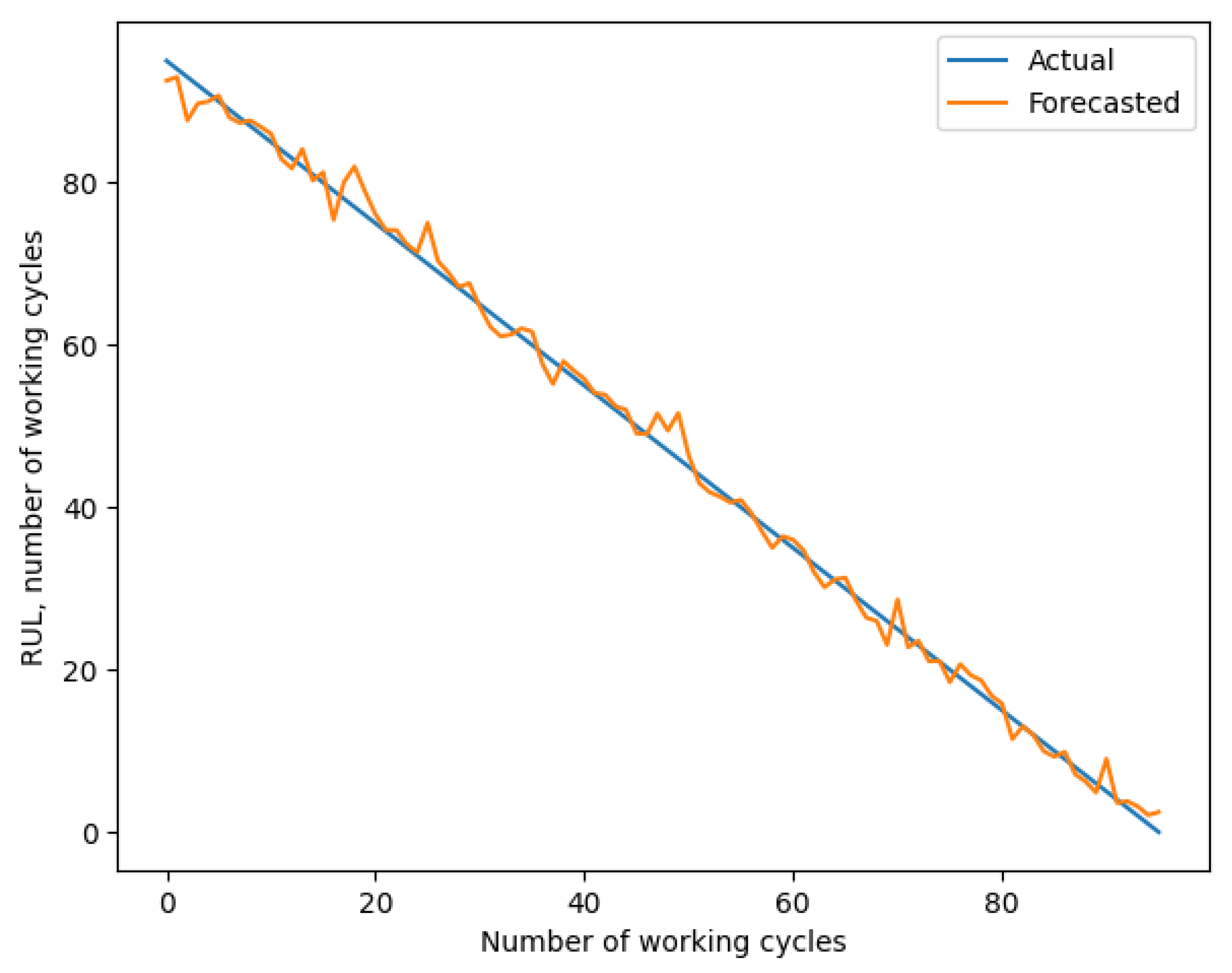

In the seventh step, a forecast of the remaining equipments life is created using existing forecasting models, in this case - XGBoost. The accuracy of the model is measured using several metrics and a chart of actual and forecast values is plotted.