1. Introduction

Given the importance of biological nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis for fundamental research and long-term applications in agriculture, nitrogenase-related protein catalysts are the keys for nitrogen reduction and porphyrin reduction, including chlorophyll biosynthesis and methanogenesis. So far, Mo-nitrogenase is considered the major catalyst responsible for global biological nitrogen fixation (BNF). Following the determination of the first crystal structures of Fe protein (NifH) and MoFe protein (NifDK) of Mo-nitrogenase from the soil free-living γ-proteobacterium Azotobacter vinelandii in 1992 [Georgiadis, M. M. et al. (1992); Kim, J. & Rees, D. C. (1992a, 1992b)], the crystal structure of the MoFe-nitrogenase complex was subsequently solved in 1997 [Schindelin et al.]. Thus, the fundamental mechanism of the two-component nitrogenase has been clearly demonstrated. Ten years later, a nitrogenase-like enzyme, dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR), involved in bacteriochlorophyll and chlorophyll biosynthesis, was discovered in certain anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, cyanobacteria, and land plants (except angiosperms) [Burke et al. (1993); Kaul et al. (2000); Goodstein et al. (2012)], and its components and complex structures were illustrated using crystallographic approaches in 2008 and 2010, respectively [Sarma et al. (2008); Muraki et al. (2010)]. Meanwhile, a more ancient nitrogenase-like protein complex consisting of CfbC Fe protein (equivalent to NifH, ChlL, BchL) and CfbD (equivalent to NifD, ChlN, BchN), which is involved in Coenzyme F430 biosynthesis, appeared to be the common ancestor for both Mo-nitrogenase and DPOR [Zheng et al. (2016)]. Remarkably, from an evolutionary perspective, light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) evolved with the emergence of oxygenic cyanobacteria on Earth approximately 3 billion years ago [Yang and Cheng et al. (2004)]. As a functional complement/replacement for DPOR, the emergence and evolution of LPOR from cyanobacteria, algae, moss, ferns, gymnosperms, to angiosperms (flowering plants) has been fascinating, especially from the structural point of view. The crystal structure of LPOR was eventually solved by our group in 2019 [Zhang et al.], highlighting several aspects of light-driven catalysts: 1) nature’s ability to evolve novel catalysts; 2) the potential for discovering or designing a light-utilizing nitrogenase (LUN); 3) LPOR in higher plants possesses versatile functions, either through its isoform(s) or interaction with other proteins [Liu et al. (2022)]; 4) through AI-based structural comparisons, we discovered that the single polypeptide LPOR may have evolved from multi-subunit nitrogenase-like proteins [Sun XZ et al. (2025)].

1.1. Nitrogenase complex is a two-component three-subunit hetero-octameric structure

Nitrogenase is the only enzyme system in the biological world capable of catalyzing the reduction of molecular nitrogen to ammonia under ambient temperature and pressure, playing a critical role in the global nitrogen cycle. Despite significant progress in understanding the biochemical, spectroscopic, and genetic characteristics of nitrogenase since the mid-20th century, its detailed molecular mechanism had remained speculative until high-resolution structural information became available. Early studies (1950s–1980s) primarily relied on techniques such as electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and Mössbauer spectroscopy to infer structural features of nitrogenase components. Although these efforts provided an important foundation for understanding nitrogenase, the resulting structural models were often crude and limited in accuracy.

A true breakthrough in nitrogenase structural biology came from the pioneering work of Georgiadis et al. (1992) and Kim and Rees (1992a, 1992b), who successfully resolved the first crystal structures of nitrogenase proteins, laying a solid structural foundation for understanding their assembly mechanisms and catalytic principles. This milestone marked the transition of nitrogenase research from biochemical characterization to a new era of structural and functional analysis.

The conventional molybdenum nitrogenase system consists of two metalloprotein components: the iron protein (Fe protein, also known as Component II) and the molybdenum-iron (MoFe) protein (also known as Component I). The Fe protein is a homodimer containing a [4Fe-4S] cluster, serving as a key electron donor in the catalytic process. This [4Fe-4S] cluster is coordinated to the protein backbone via Cys97 and Cys132 residues (based on the Azotobacter vinelandii Fe protein sequence) in each subunit. Compared to typical ferredoxins, the [4Fe-4S] cluster in the Fe protein is more exposed. Consequently, it is highly sensitive to iron chelators, changes in oxidation state, and nucleotide binding, reflecting the complex interdependence of these functional elements.

The MoFe protein is a more complex α₂β₂ heterotetramer, containing two critical metal cofactors: the P-cluster (an [8Fe-7S] cluster) and the FeMo-cofactor (a [7Fe-9S-Mo-C-homocitrate] cluster). The P-cluster, located at the interface of each αβ subunit pair, primarily serves as an electron transfer relay, while the FeMo-cofactor is the true catalytic active center, responsible for nitrogen binding and reduction. The FeMo-cofactor has a unique structure, consisting of two cluster units—a [4Fe-3S] cluster and a [1Mo-3Fe-3S] cluster—bridged by three non-protein ligands. Within this complex metal cluster, the molybdenum atom is coordinated to the protein backbone via a histidine residue (Hisα442) and to a homocitrate molecule, while the iron atom Fe1 is coordinated to the protein through a cysteine residue (Cysα275).

The catalytic mechanism of nitrogenase for nitrogen reduction involves a complex electron transfer chain coupled with ATP hydrolysis. The catalytic cycle consists of three fundamental steps: first, the Fe protein is reduced by accepting electrons from an external electron carrier (such as ferredoxin or flavodoxin). Second, in the presence of MgATP, the reduced Fe protein forms a complex with the MoFe protein and transfers electrons to it, while hydrolyzing two ATP molecules to provide energy for this thermodynamically unfavorable electron transfer. Finally, electrons and protons are sequentially transferred to the FeMo-cofactor, where the bound nitrogen molecule is progressively reduced to ammonia. Notably, each electron transfer is accompanied by a binding-dissociation cycle between the Fe protein and MoFe protein, with the dissociation step identified as the rate-limiting step of the overall reaction.

The overall stoichiometry of the nitrogen fixation reaction is: N₂ + 8H⁺ + 8e⁻ + 16MgATP → 2NH₃ + H₂ + 16MgADP + 16Pi (Hoffman et al., 2020). This reaction’s high ATP demand (16 ATP molecules per nitrogen molecule reduced) makes nitrogen fixation extremely energy-intensive, consuming up to 40% of total cellular ATP in actively nitrogen-fixing microorganisms. In addition to the primary molybdenum nitrogenase, some microorganisms can express alternative nitrogenases under molybdenum-deficient conditions, using vanadium or iron instead of molybdenum as the catalytic center. However, these alternative enzymes are less efficient and produce more hydrogen gas as a byproduct.

The crystal structure of the MoFe protein was determined using advanced techniques such as multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) and non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging. Researchers determined heavy atom positions by analyzing isomorphous difference Patterson maps and established NCS relationships between different crystal forms using rotation and translation functions. Despite only approximately 36% sequence homology between MoFe proteins from different species (e.g., Azotobacter vinelandii and Clostridium pasteurianum), iterative electron density averaging across crystal forms yielded a high-quality structural model containing approximately 95% of the atoms.

During the structural analysis, the electron density features of the metal cofactors were the most prominent, fully consistent with natural anomalous scattering data. Since the initial phase determination did not rely on anomalous scattering, the resulting electron density maps were free from bias introduced by predefined cofactor models; this ensured the objectivity of the structural analysis. Researchers constructed the metal center model using the [4Fe-4S] cluster fragment as a basic unit and positioned the cofactors based on key amino acid residues identified from mutagenesis studies. At 2.7 Å resolution, although individual atoms could not be resolved, the identity of atoms at different positions could be reasonably inferred. This was achieved by combining existing spectroscopic and chemical analysis data.

A significant discovery regarding the FeMo-cofactor was the identification of a central carbon atom. This atom was initially obscured in early crystallographic studies due to Fourier ripple effects, but was later confirmed through higher-resolution X-ray crystallography. Subsequent extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and X-ray emission spectroscopy studies identified this atom as carbon. This discovery significantly refined the understanding of the FeMo-cofactor structure and provided critical clues to its catalytic mechanism.

In 1997, the crystal structure of the Fe protein-MoFe protein complex was resolved, validating early models based on crosslinking experiments and computational docking predictions. The structure revealed that the [4Fe-4S] cluster of the Fe protein and the P-cluster of the MoFe protein are aligned along a pseudo-twofold axis between the two proteins, with a distance of approximately 14 Å. Upon complex formation, the Fe protein undergoes significant conformational changes, bringing the two metal centers closer than expected. The P-cluster is positioned nearly equidistant between the Fe protein’s [4Fe-4S] cluster and the FeMo-cofactor, serving as an ideal relay for efficient electron transfer. Structural analysis also showed that the MoFe protein does not directly interact with nucleotides—indicating that its role in ATP hydrolysis is to stabilize the Fe protein-nucleotide intermediate, a function that the Fe protein cannot perform alone.

Recently, Kang et al. captured the MoFe protein under N₂-turnover conditions and visualized dinitrogen-derived ligands bound at sites normally occupied by belt sulfurs in FeMoco. Their 1.83 Å structures reveal reversible displacement of S2B/S3A/S5A and accompanying changes in Mo–homocitrate ligation, providing direct evidence that the cofactor is dynamically remodeled and that multiple belt-sulfur sites participate in N₂ reduction (Kang et al., 2020).

The discovery and structural elucidation of nitrogenase have not only deepened our understanding of biological nitrogen fixation mechanisms but also provided important structural and functional templates for studying related enzyme systems. In the field of chlorophyll biosynthesis, for instance, enzyme systems with significant homology to nitrogenase have been identified. This discovery expands our understanding of the evolutionary relationships and the diversity of catalytic mechanisms within the family of ATP-dependent electron transfer enzymes.

1.2. Dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR)

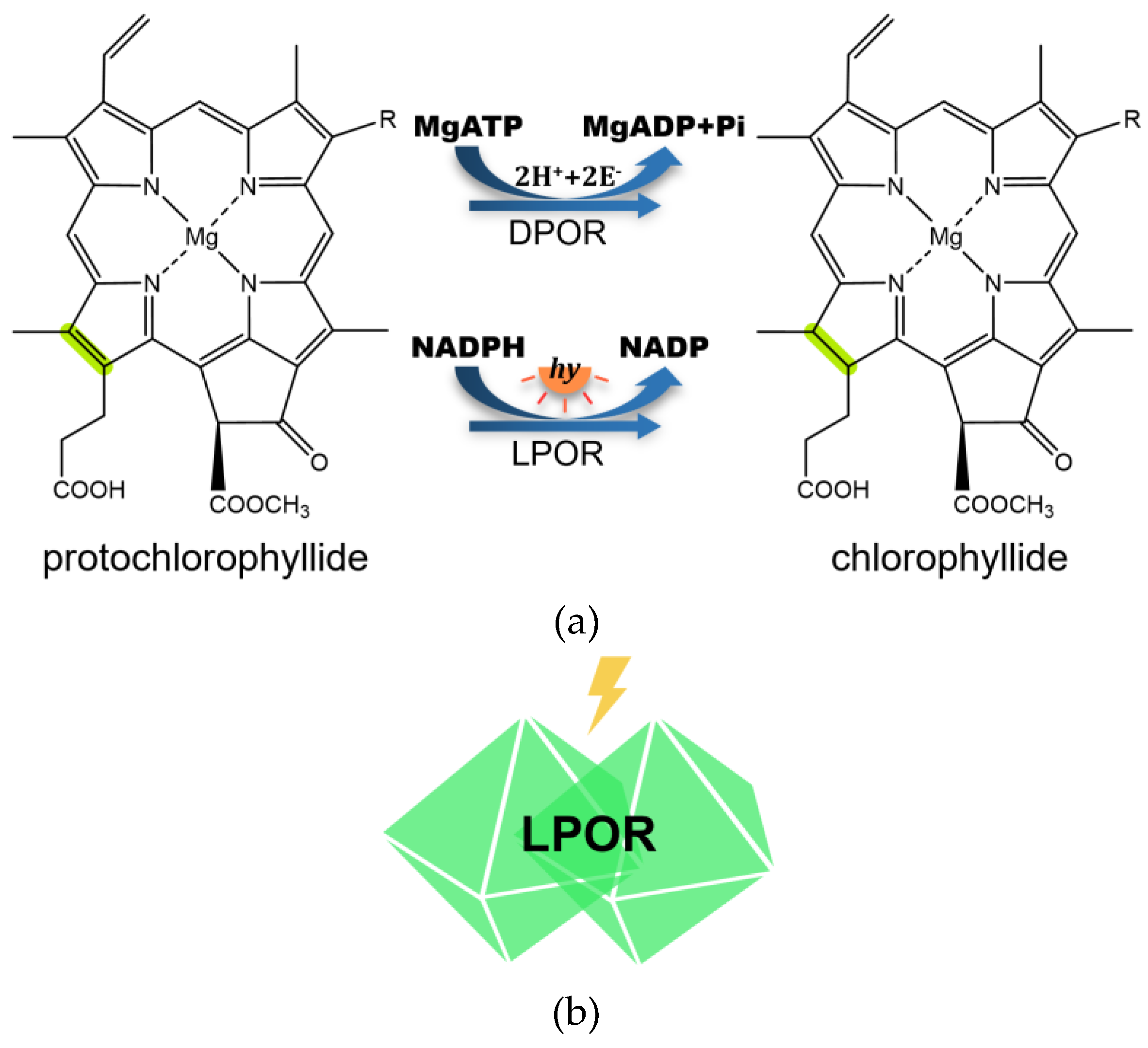

Chlorophyll (Chl) and bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) are essential pigments in photosynthesis, synthesized from glutamate through a 15-step enzymatic pathway. A key rate-limiting step in this biosynthetic process is the reduction of the D-ring double bond of protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) to chlorophyllide (Chlide), which occurs via light-dependent or light-independent mechanisms. The light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) is a short-chain dehydrogenase that relies on NADPH and light to catalyze a photoinduced electron transfer. In contrast, the light-independent dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR) is an iron-sulfur two-component enzyme system encoded by the bchL/chlL, bchB/chlB, and bchN/chlN genes.

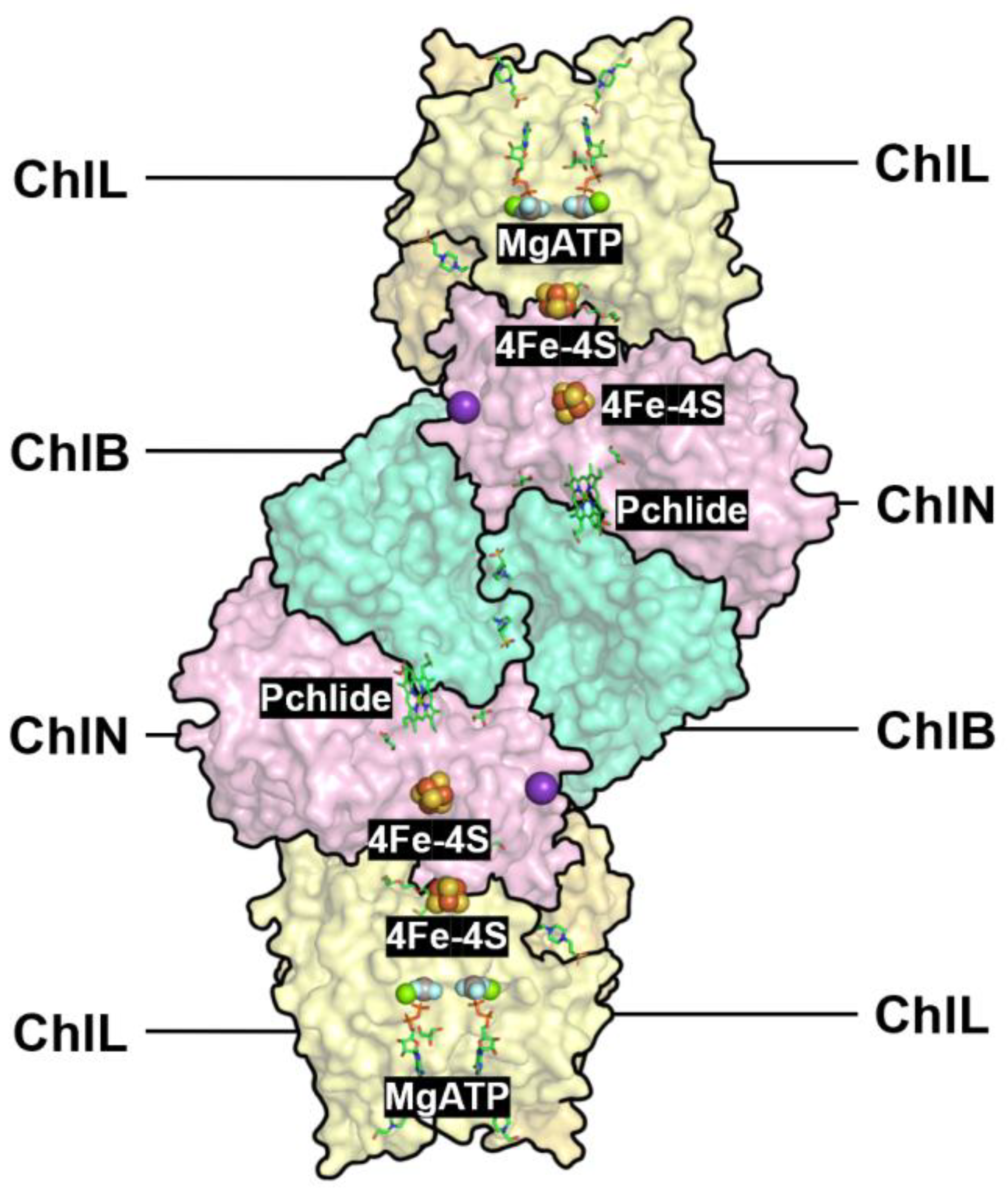

DPOR consists of the L-protein (BchL) and the NB-protein (a BchN/BchB heterotetramer). In its catalytic mechanism, BchL serves as the sole electron donor, transferring electrons to the BchN/BchB complex, which contains the Pchlide reduction site. Notably, DPOR component proteins exhibit striking similarities in primary sequence and overall structure with the Fe protein (NifH) and MoFe protein (NifD and NifK) of nitrogenase, establishing DPOR as a homologous enzyme system.

Structural biology studies have provided a critical foundation for understanding DPOR’s molecular mechanisms. Sarma et al. (2008) resolved the high-resolution crystal structure of BchL co-crystallized with MgADP at 1.6 Å, revealing the structural features of a key enzyme in chlorophyll biosynthesis at the atomic level for the first time. Although BchL and the nitrogenase Fe protein are highly similar in overall structure, both adopting a dimeric architecture with a [4Fe-4S] cluster, they differ significantly in the charge distribution at their protein interaction interfaces. BchL’s docking surface is predominantly positively charged, while the Fe protein’s is predominantly negatively charged. Functional experiments confirmed that BchL cannot substitute for the Fe protein in nitrogen fixation, indicating that homologous proteins achieve functional specificity through surface charge engineering.

More recently, Kashyap et al. (2024) utilized cryo-electron microscopy to further elucidate DPOR’s detailed catalytic mechanism. This study obtained high-resolution structures (2.7–3.8 Å) of DPOR in various functional states, revealing significant functional asymmetry in the NB-protein upon substrate binding. One half of the NB-protein exhibited an ordered arrangement of residues in the electron transfer pathway, while the other half showed misalignment, leading to asymmetric binding of the L-protein. Crucially, the study identified a novel dinuclear copper center at the NB-protein tetramer interface, which coordinates allosteric communication between the two halves—enabling temporal regulation of electron transfer.

Regarding kinetic mechanisms, Bedendi et al. (2025) innovatively employed visible spectroscopy to monitor DPOR’s catalytic process in real time, successfully isolating and observing the enzyme-substrate complex formation and electron transfer steps in the absence of an electron donor. The study found that electron transfer is the rate-limiting step under saturating conditions, and enzyme-substrate complex formation exhibits biphasic kinetics and cooperative characteristics, highlighting the critical regulatory role of substrate availability in DPOR activity.

Notably, structural analysis of the DPOR complex revealed that the substrate Pchlide precisely occupies the position of the FeMo-cofactor in the nitrogenase complex, suggesting its role as a cofactor in DPOR. This finding further confirms the close evolutionary and functional relationship between DPOR and nitrogenase, providing important clues for understanding the catalytic mechanisms and the evolutionary divergence of the nitrogenase-like enzyme family.

1.3. Light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR)

In contrast to the light-independent DPOR, light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) employs a fundamentally different catalytic strategy. LPOR, a member of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) superfamily, is a monomeric enzyme that relies on NADPH and light to catalyze a photo-induced electron transfer process, converting protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) to chlorophyllide (Chlide). Compared to the oxygen-sensitive and structurally complex multi-subunit DPOR complex, LPOR is more stable and structurally simpler, providing relatively favorable conditions for structural analysis.

However, the journey to elucidate LPOR’s structural biology has been challenging. Despite its structural advantages over DPOR, it took nearly two decades from the first proposed LPOR structural model in 2001 to the resolution of the first crystal structure of cyanobacterial LPOR by Zhang et al. (2019). This pioneering work resolved the crystal structures of LPOR from Thermosynechococcus elongatus and Synechocystis sp., including the free form and complexes with nicotinamide cofactors. Structural analysis and molecular simulations of the Pchlide–NADPH–LPOR ternary complex revealed multiple critical interactions within the LPOR active site, which are essential for Pchlide binding, photosensitization, and photochemical transformation.

Following the successful resolution of the cyanobacterial LPOR structures, an increasing number of LPOR structures from higher plants have now been reported. Studies by Dong et al. (2020) and Nguyen et al. (2021) have further enriched the LPOR structural database. Notably, Nguyen et al. (2021) utilized cryo-electron microscopy to report the atomic structure of LPOR multimers, revealing for the first time the complete three-dimensional structure and higher-order assembly states of LPOR. The study found that, in the dark, LPOR aggregates into helical fibril structures arranged around a constricted lipid bilayer tube. Some LPOR and Pchlide molecules are inserted into the outer membrane monolayer, while the product Chlide is positioned on the membrane surface. This unique assembly not only enhances light energy transfer and catalytic efficiency but also directly contributes to membrane remodeling. It forms highly curved tubular structures with prolamellar body (PLB) spectral characteristics, which provide lipid material for thylakoid membrane assembly.

In higher plants, the LPOR system exhibits greater complexity. A comprehensive study by Vedalankar and Tripathy (2024) highlighted that LPOR has multiple isoforms (PORA, PORB, PORC), which exhibit differential expression patterns during chloroplast development. PORA is primarily expressed in etiolated seedlings and rapidly declines upon light exposure; PORB is constitutively expressed throughout the plant life cycle; and PORC is expressed in a light-intensity-dependent manner, with high expression under strong light conditions. This finely tuned temporal regulation enables LPOR to not only perform its catalytic function, but also play a critical photoprotective role by rapidly converting photosensitive Pchlide to Chlide, preventing oxidative stress and cellular damage caused by singlet oxygen production.

In terms of molecular mechanisms, recent computational and experimental studies have provided deep insights into LPOR’s catalytic mechanism. Pesara et al. (2024) systematically compared two possible Pchlide binding modes using molecular dynamics simulations, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics calculations, and site-directed mutagenesis experiments. The study found that the binding mode, based on the latest high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy data, exhibited significantly stronger binding affinity, with a complex interaction network involving residues Y177, H319, and C131. This network not only influences the excited-state energy of the pigment but also plays a key role in determining LPOR substrate specificity.

Taylor et al. (2024) further investigated the catalytic mechanism of the LPOR ternary complex using multiple experimental techniques. The study revealed that the strictly conserved tyrosine residue Tyr193 is primarily involved in Pchlide binding rather than proton transfer; the active site cysteine Cys226 is critical for both hydride and proton transfer reactions and is considered a key proton donor; and the conserved glutamine Gln248, through its interaction with the substrate’s central Mg atom, plays a significant role in maintaining Pchlide’s correct binding conformation and electronic properties. These studies indicate that LPOR achieves efficient light-driven reduction through localized hydride transfer from NADPH and long-range proton transfer along a structurally-determined pathway.

In summary, LPOR, as a key regulatory enzyme in the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway, exhibits far greater structural and functional complexity than initially recognized. From the basic catalytic function of the monomeric enzyme to the synergistic effects of multimeric assemblies, and from simple photochemical reactions to complex membrane remodeling, the LPOR system exemplifies the intricate design of biological systems at the molecular level. It also provides critical theoretical foundations for understanding the molecular basis of photosynthesis, as well as developing related biotechnological applications.

2. Evolutionary relationships among archael Coenzyme F430 reductase, DPOR, COR, nitrogenase and LPOR

- 1)

Common Origin: Evolutionary Basis of a Single Subdomain Precursor

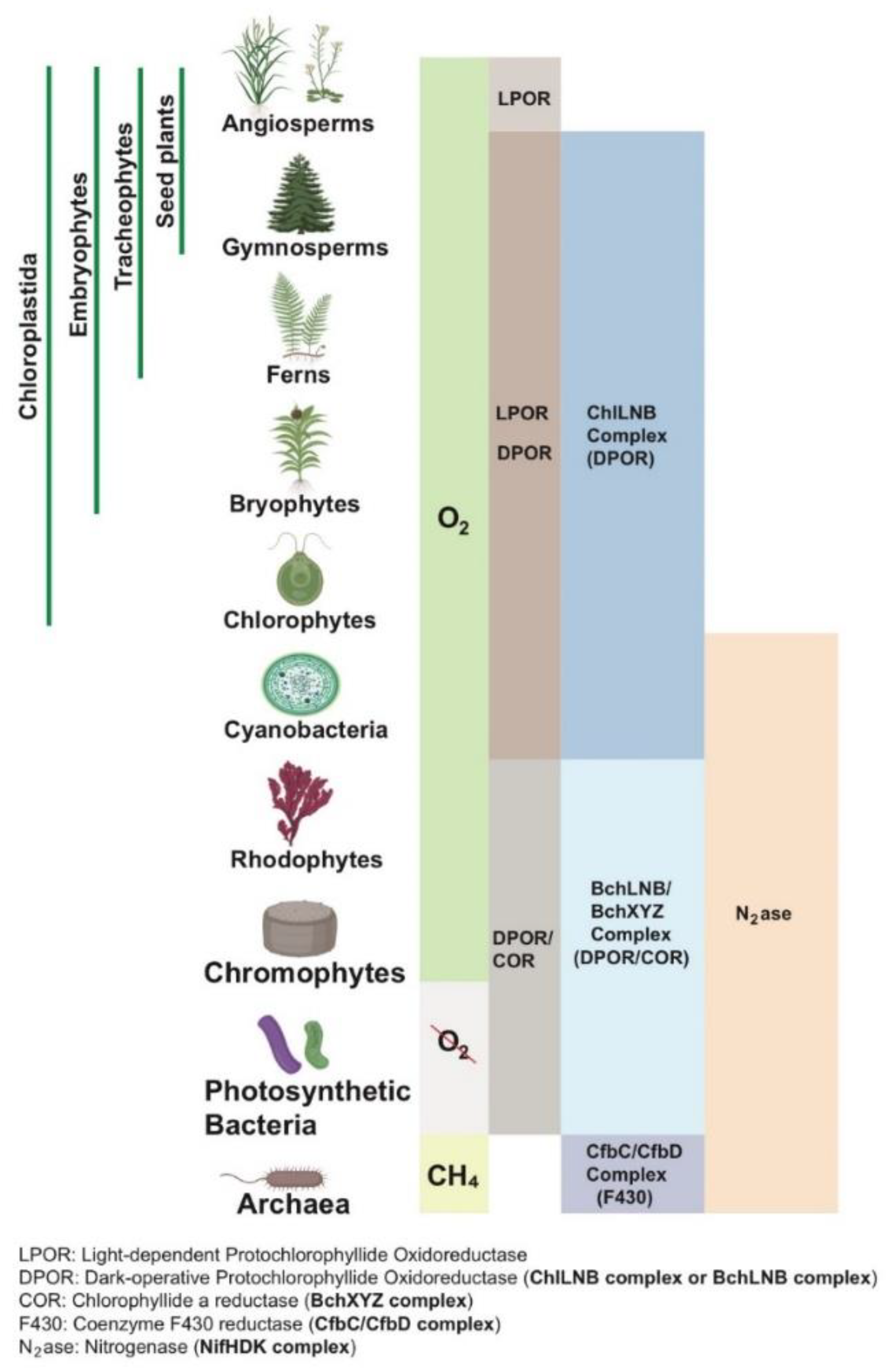

Light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR), dark-operative protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (DPOR), chlorophyll oxidoreductase (COR), nitrogenase, and coenzyme F430 reductase (F430 enzyme) exhibit significant structural and functional connections, suggesting they may have originated from a common single subdomain precursor. The F430 enzyme (CfbCD), found only in archaea, is the most ancient nitrogenase-like protein—considered the common ancestor of nitrogenase (NifHDK), DPOR (BchLNB/ChlLNB), and COR (BchXYZ). Structural analysis reveals high similarity between LPOR and the BchL subunit of DPOR (DALI Z-score 5.5), with slightly lower similarity to BchN and BchB (DALI Z-scores of 2.6 and 4.5, respectively), with all values exceeding the structural relatedness threshold (DALI Z-score 2). The Cbc subunit of the F430 enzyme (C-terminal and M domains) shows structural homology with subunits of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase (DALI Z-scores 3.5–7.1), suggesting that the subunits of all these enzymes likely evolved through gene duplication from a single subdomain precursor.

Approximately 71% of LPOR’s structure (92/128 amino acids) closely matches nitrogenase-like proteins, differing primarily at its C-terminus and an additional region (approximately 45 amino acids) absent in nitrogenase-like proteins. This region may represent a unique evolutionary adaptation for LPOR’s photocatalytic function. The hypothesis of a single subdomain precursor as the common origin is supported by principles of structural continuity, similarity scores, amino acid substitution rates, and the presence of the additional region. Species diagrams created using BioRender.com clearly illustrate the distribution and evolutionary sequence of these enzymes across microbial and plant kingdoms (

Figure 4).

- 2)

Evolutionary Pathway of LPOR: From COR via RDH to a Single-Subunit Enzyme

The evolution of LPOR from a multi-subunit nitrogenase-like protein, chlorophyll oxidoreductase (COR), to a single-subunit photoenzyme involved retinol dehydrogenase (RDH) as a critical intermediate. Structural comparisons using FoldSeek against the AlphaFold Swiss-Pro database revealed high similarity between RDH and LPOR, suggesting RDH mediated the evolutionary transition from COR to LPOR (bioRxiv preprint). LPOR likely originated from the BchY subunit of COR through two gene recombination events that integrated RDH structural modules. The N-terminus of BchY shares structural homology with the C-terminus of RDH, while the N-terminus of RDH is similar to the C-terminus of LPOR. This suggests that LPOR simplified the multi-subunit complex through gene fusion.

COR, found in anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria, resembles the Fe protein (NifH) and MoFe protein (NifDK) of nitrogenase. In contrast, LPOR’s single-subunit structure—NADPH-dependent and originating in cyanobacteria—has become ubiquitous across the plant kingdom, including chlorophytes, land plants, vascular plants, and seed plants. This reflects adaptation from anaerobic to aerobic environments.

RDH, which catalyzes retinal metabolism in organisms lacking COR and LPOR, laid the foundation for LPOR’s photocatalytic function. LPOR’s 'additional region' was likely acquired from RDH through gene recombination, facilitating adaptation to oxygen-rich environments and the development of a light-driven mechanism. In cyanobacteria, green algae, mosses, ferns, and gymnosperms, DPOR and LPOR coexist, whereas LPOR dominates in angiosperms, underscoring its critical role in aerobic photosynthesis (

Figure 4a–4c and Supplementary

Figure 2).

- 3)

Structural Conservation and Functional Divergence of Nitrogenase-Like Proteins

Nitrogenase-like proteins (nitrogenase, DPOR, COR, and F430 enzyme) exhibit high structural conservation but have diverged functionally to meet distinct metabolic demands. Nitrogenase catalyzes the reduction of nitrogen gas to ammonia, DPOR and COR are involved in chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis, and the F430 enzyme facilitates coenzyme F430 synthesis for archaeal methane metabolism. Using the iron-based nitrogenase from Rhodobacter capsulatus (PDB ID: 8OEF) as an example, literature shows that its AnfH, AnfD, and AnfK subunits are structurally similar to DPOR’s BchL, BchN, and BchB subunits (DALI Z-scores 2.6–5.5). The Pchlide-binding site in DPOR, spatially overlapping with the FeMo-cofactor site in nitrogenase, indicates that DPOR adapted its structure to accommodate Pchlide, while nitrogenase optimized the FeMo-cofactor for nitrogen reduction. COR (in anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria) and the F430 enzyme (in archaea) evolved specific catalytic capabilities for bacteriochlorophyll precursors and the F430 cofactor, respectively. DPOR is present in both anaerobic and aerobic photosynthetic bacteria, as well as plants (except angiosperms), making it the only nitrogenase-like protein spanning both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

In contrast, LPOR, a single-subunit enzyme, exhibits a highly evolved catalytic mechanism, with precise structures observed in cyanobacteria and plants (

Figure 4a–4c). The key to functional divergence lies in adaptive changes in substrate-binding sites. Meanwhile, structural conservation reflects the evolutionary trajectory of these enzymes from a single precursor. The Cbc subunit of the F430 enzyme is considered the ancestral template for nitrogenase-like proteins, providing the structural foundation for the diversification of DPOR, COR, and nitrogenase.

- 4)

Evolutionary Environmental Context: Transition from Anaerobic to Aerobic Metabolism

The evolution of nitrogenase-like proteins and LPOR is closely tied to changes in Earth’s atmospheric oxygen levels. In the early anaerobic Earth environment, nitrogenase, DPOR, COR, and the F430 enzyme served as key enzymes for anaerobic metabolism, catalyzing nitrogen fixation, pigment synthesis, and methane metabolism, respectively. The F430 enzyme is exclusive to archaea, while COR is limited to anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria. DPOR is found in both anaerobic and aerobic photosynthetic bacteria and plants (except angiosperms). Nitrogenase is restricted to prokaryotes, reflecting its ancient origin (

Figure 4). With the Great Oxidation Event (GOE), cyanobacteria increased atmospheric oxygen levels through LPOR-mediated oxygenic photosynthesis. LPOR’s oxygen tolerance allowed it to supplant the oxygen-sensitive DPOR, becoming the core enzyme for chlorophyll synthesis in cyanobacteria and plants. This includes chlorophytes, land plants, vascular plants, and seed plants (bioRxiv preprint).

LPOR and DPOR share functional similarity in cyanobacteria, as both catalyze Pchlide reduction to Chlide. However, structural analysis indicates a shared origin. The TFT motif in DPOR is present in some LPORs and is absent in cyanobacterial LPOR, suggesting convergent evolution. Through the inheritance of LPOR and DPOR, the cyanobacterial photosynthetic system evolved into chloroplasts, laying the foundation for eukaryotic photosynthesis.

The evolutionary branch of RDH shifted from energy metabolism in archaea and bacteria to retinal metabolism in animal visual systems. This indicates that LPOR and RDH together drove the evolutionary transition from microbes to macroscopic organisms.

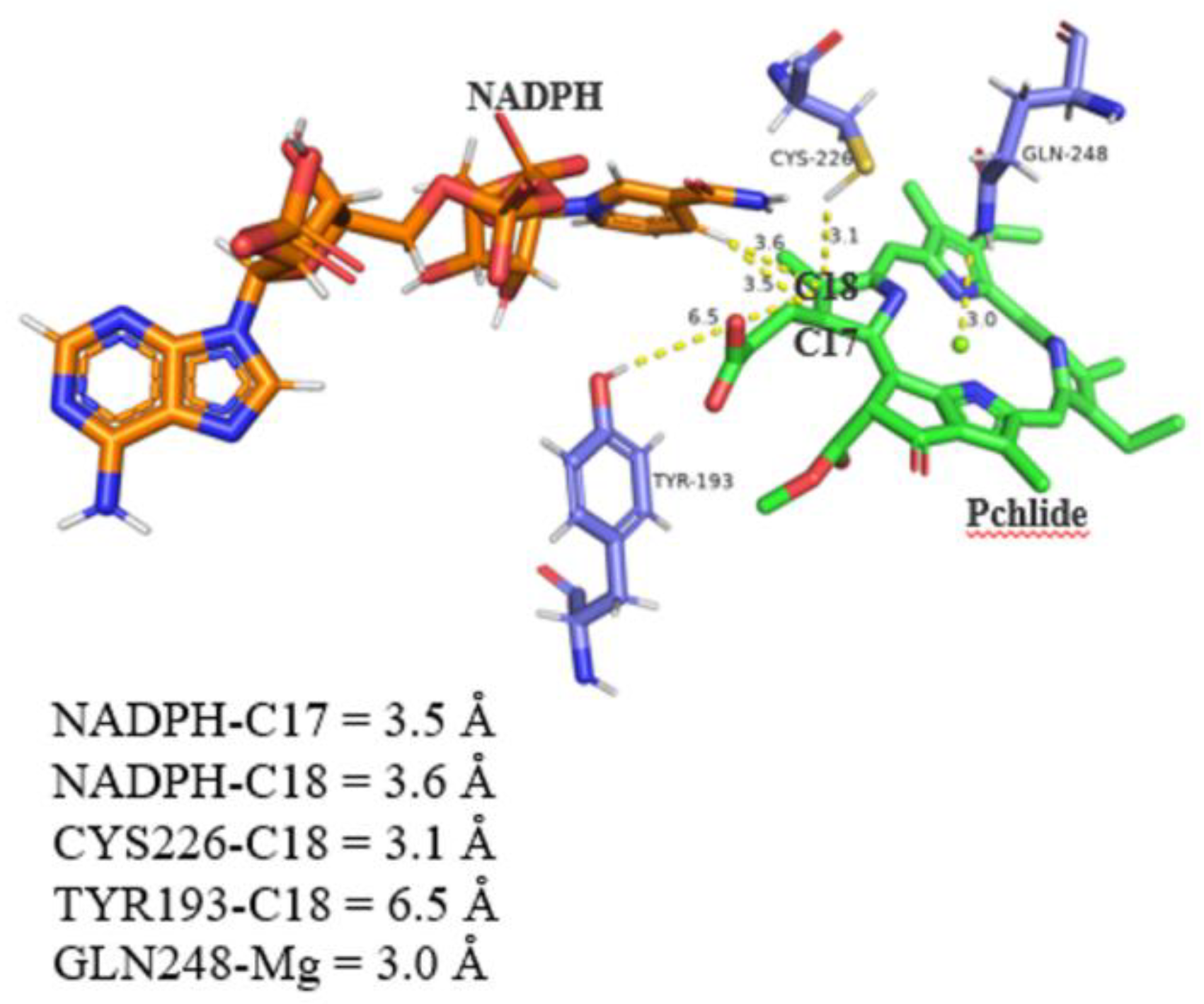

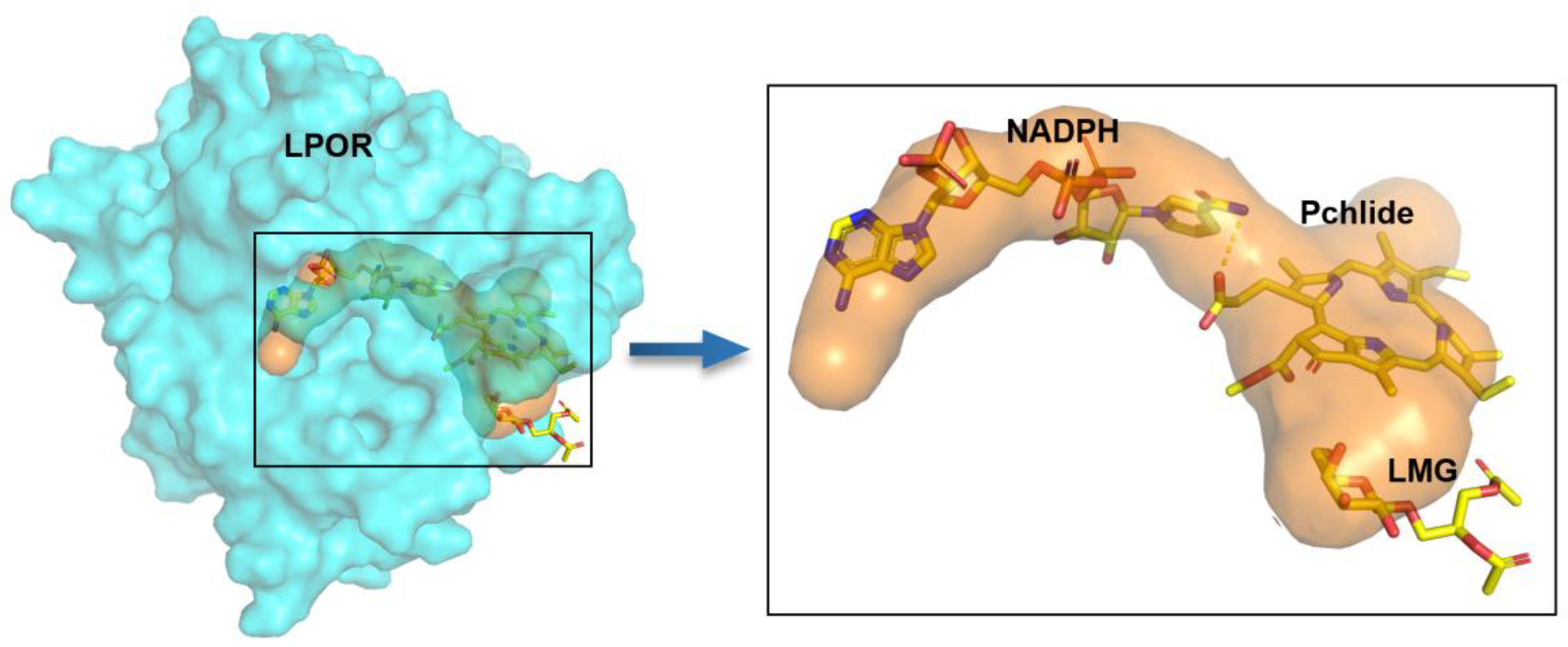

2.1. Binding Mode of Undefined LPOR with NADPH and Pchlide

To further understand the binding mode of uncharacterized LPOR with NADPH and Pchlide, we predicted the three-dimensional structure of the uncharacterized LPOR using AlphaFold. In a previous paper, we compared the modelled LPOR structures with the LPOR crystal structure (PDB: 7JK9) [Sun XZ et al. (2025)]. In this article, we further elaborate the binding mode of Pchlide-NADPH with the uncharacterized LPOR, using the predicted three-dimensional structure of the uncharacterized LPOR and molecular docking. As shown in

Figure 5, the distance between NADPH and C17 and C18 demonstrated a favorable transfer distance of <4 Å: 3.5 Å and 3.6 Å, respectively. In addition, we analyzed and visualized the NADPH and Pchlide ion channels of LPOR using the CAVER 3.0.3 plugin in PyMOL. The results further illustrated the potential pathways through which substrates may access the active site (

Figure 6).

The conserved, catalytically important CYS226 residue appears optimally positioned to participate in the reaction chemistry because it is 3.1 Å from the C18 position of the Pchlide substrate. Besides, GLN248 was found facing inwards to the active site, and the distance was close to the central Mg atom (3.0 Å) of Pchlide, potentially forming an adduct. However, the distance between Tyr193 and the C18 carbon is less favorable for proton transfer, at 6.5 Å. In all, the interaction mode is similar to light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) bound to NADPH-Pchlide (PDB:7JK9) [Taylor et al. (2022)]. To explain the interaction, we also analyzed the active site of other uncharacterized LPOR structures (angiosperm LPOR, monocot LPOR, fern LPOR, gymnosperm LPOR, bryophyte LPOR, and algae LPOR) with the Pchlide–NADPH model, including TYR, CYS, GLN, and their respective distances to the C17/C18 region and central Mg atom of Pchlide (S-

Figure 2A-2F).

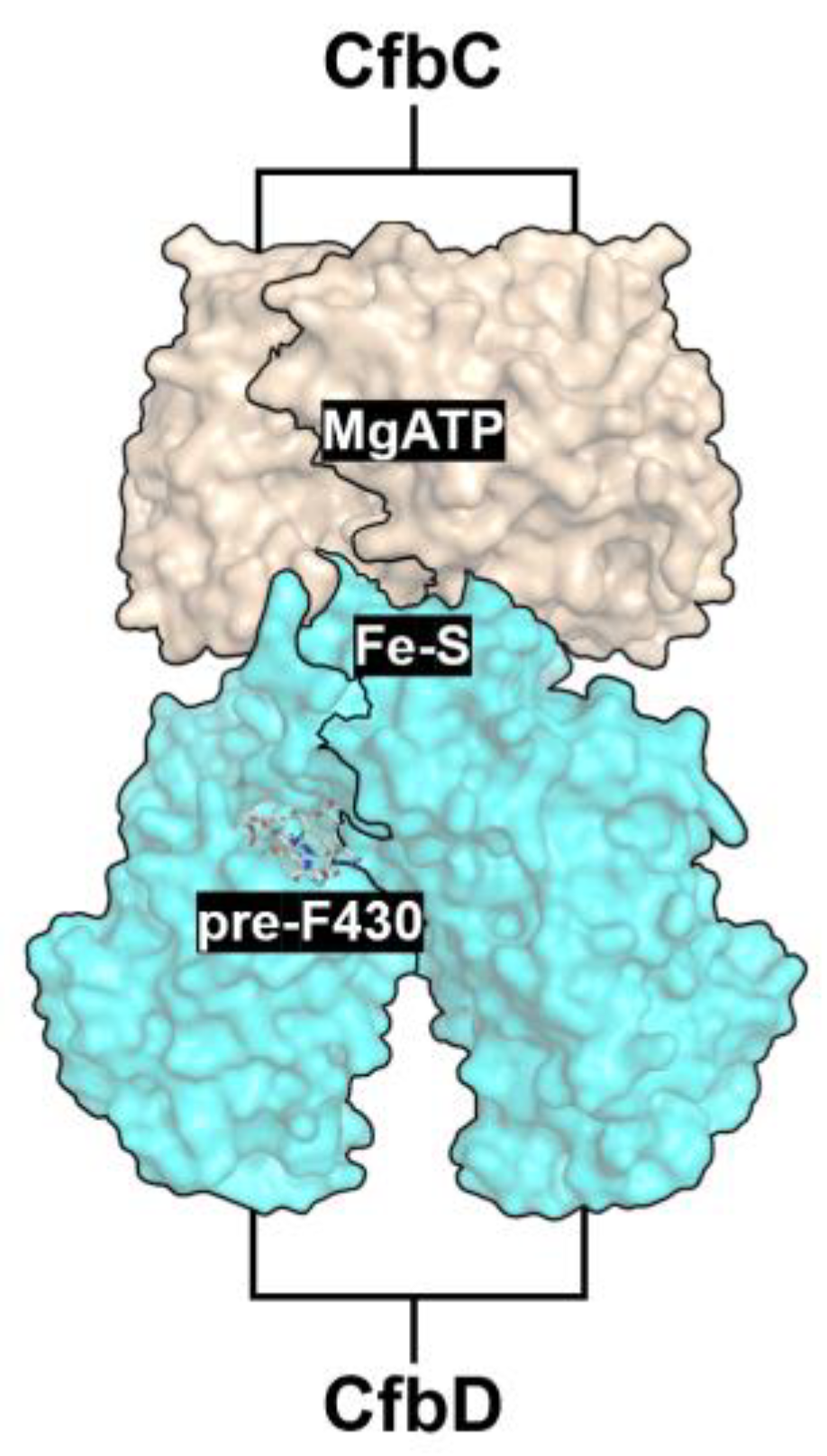

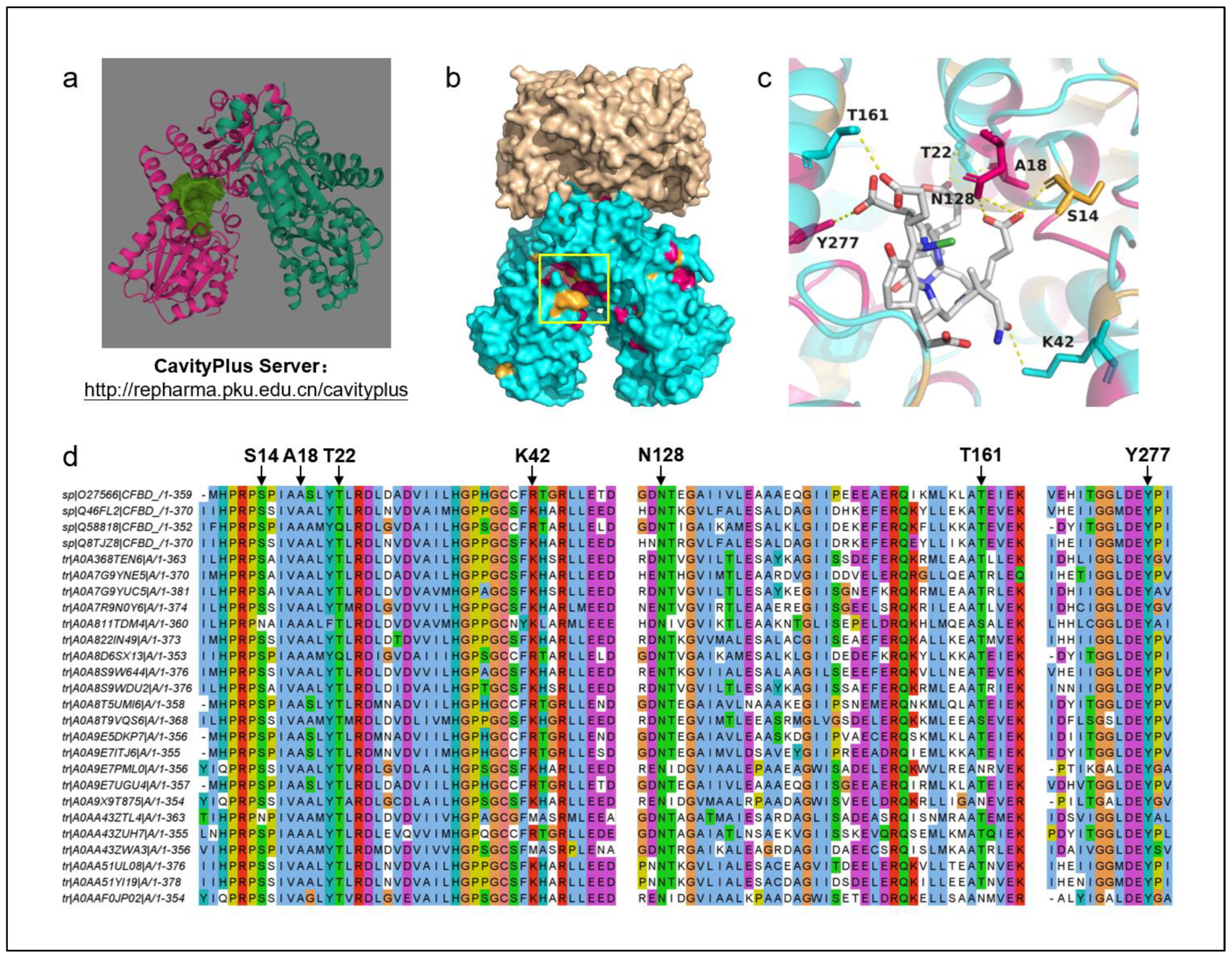

2.2. Final structural milestone for nitrogenase-like protein complex

Protein complex CfbC/D, Coenzyme F430 reductase (hereafter referred to as F430,

Figure 7), is an ancient nitrogenase-like catalyst consisting of the CfbC Fe protein (equivalent to NifH) and CfbD (equivalent to NifD, ChlN, BchN). It is involved in the biosynthesis of Coenzyme F430, a redox-active nickel tetrahydrocorphin-containing prosthetic group. This complex could represent a simplified and ancestral version of N2ase, DPOR, or COR.

Coenzyme F430 is a redox-active nickel tetrahydrocorphin-containing prosthetic group in the active site of methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR), which catalyzes the final step in methane biosynthesis by methanogenic archaea.

The CfbC (UniProt ID: Q46FL1) and CfbD (UniProt ID: Q46FL2) proteins from Methanosarcina barkeri were subjected to AlphaFold-based structure prediction. Using the AlphaFold online platform, two sequences each of CfbC and CfbD were uploaded to simulate the quaternary structure of the F430 reductase enzyme complex (

Figure 8b), with the CfbC subunits shown in dark orange and the CfbD subunits in cyan. Representative CfbD sequences from various species were collected for sequence alignment (

Figure 8d), and the strictly conserved residues were identified and recorded. The predicted structure of F430 reductase was then annotated in PyMOL, with strictly conserved residues highlighted in red and moderately conserved residues in orange (

Figure 7,

Figure 8b). A cluster of conserved residues was observed within the yellow-boxed pocket region.

Additionally, the predicted structure of F430 reductase and the F430 substrate molecule were uploaded to the CavityPlus server platform to predict the active pockets (

Figure 8a). The predicted active pocket is shown in dark green, with the results indicating a high correspondence between the predicted pocket region and the conserved regions identified from sequence alignment.

Molecular docking analysis of the predicted F430 reductase structure with the F430 substrate was performed using AutoDock Vina 1.1.2. The results revealed a binding energy of -8.1 kcal/mol, indicating a strong binding affinity. Interacting amino acid residues were annotated (

Figure 8c) and marked on the sequence alignment diagram. The results show that most of the interacting residues are conserved.

Based on our current results and global efforts working on Coenzyme F430 reductase, we expect that the X-ray crystal structure of either CfbC or CfbD, as well as the CfbC/D complex, will be achieved soon.

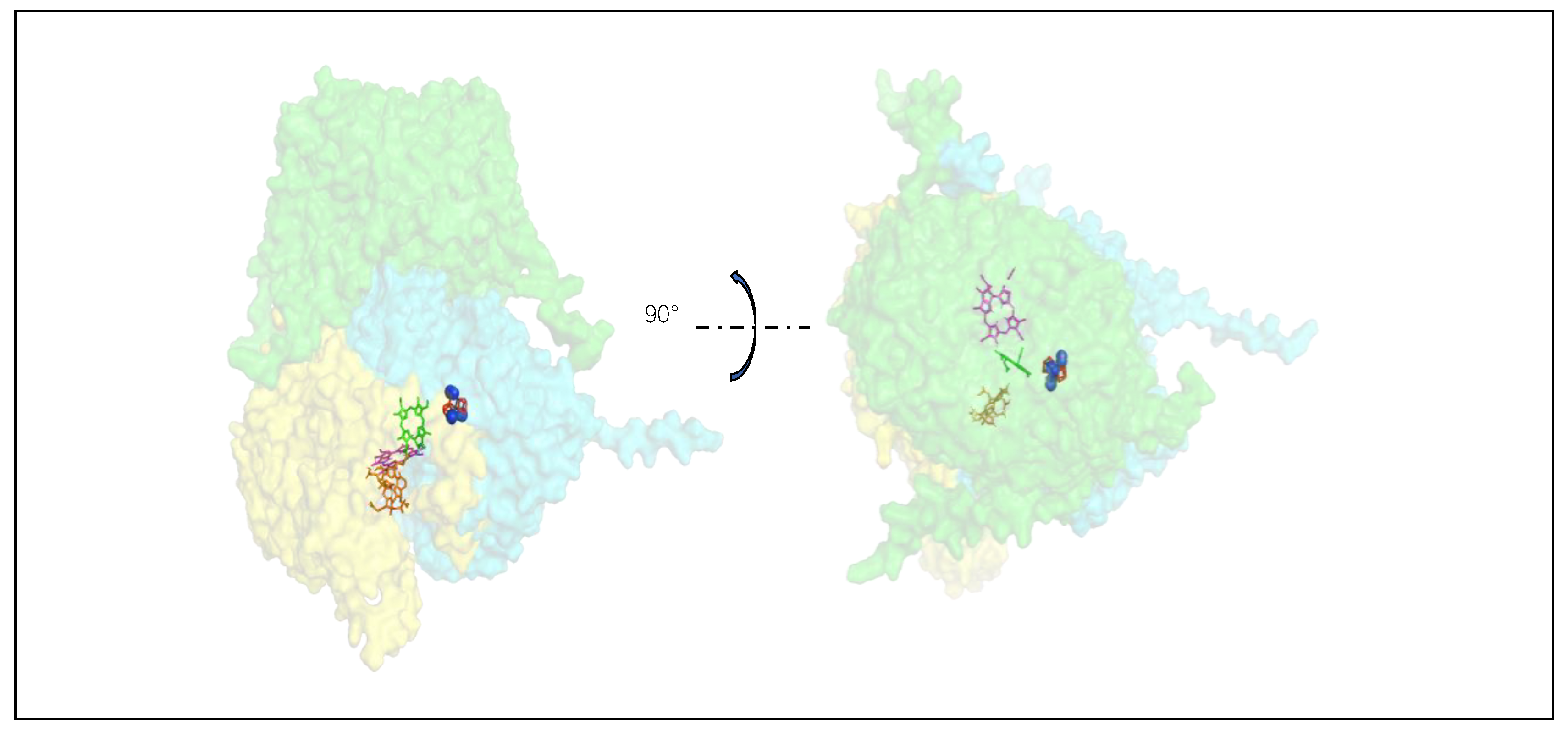

Based on real structures of N2ase, DPOR, and AlphaFold structures of COR and F430, we provide an overview of the substrate-channeling pathways (

Figure 9).

Green subunit: NifH, ChlL, BchX, CfbC; Cyan subunit: NifD, ChlN, BchY, CfbD; Yellow subunit: NifK, ChlB, BchZ, CfbD; Red ligand with blue balls: FeMo-cofactor with N2; Blue ligand: Pchlide; Magenta ligand: Chlide; Orange ligand: F430 cofactor.

According to our analysis, L contributes β1, α5, α11; N/B contributes α3; N contributes α9; and B contributes β7, β8. The majority of the remaining structures are similar among the three. Except for α6 and α7, which are unique to LPOR, corresponding structures can be found for the other regions.

In the article referenced [Buhr et al. (2008)], α6 and α7 belong to the extra loop of LPOR, which is an additional loop compared with the barley LPOR and Escherichia coli AHI genes. However, that article was from 2008, and at that time, relying on homologous modeling, it was impossible to identify spiral structures on the loop.

The three loops between β4-α5-α6-α7 and the two loops between β6-α9-α10 surround the substrate, which may be related to pocket formation. The extra loop formed between α6 and α7 is closest to the substrate.

2.3. FeMoco docking with three-subunit N2ase

The nitrogenase enzyme, responsible for biological nitrogen fixation, relies on the intricate coordination and stabilization of its iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco), a unique [MoFe₇S₉C] cluster. This cluster is embedded within the MoFe protein and serves as the active site for N₂ reduction [Spatzal, T., et al. (2011)]. Structural and spectroscopic studies have provided significant insights into its binding interactions and electron transfer pathways.

(1) Direct Coordination by Cysteine and Histidine: Crystallographic and spectroscopic analyses have revealed that FeMoco is coordinated within the α-subunit of the MoFe protein via interactions with amino acid residues, including homocitrate and histidine ligands [Einsle, O., et al. (2002); Lancaster, K. M., et al. (2011)]. The Mo atom is coordinated by a histidine residue, while Fe-S interactions stabilize the cluster within the protein scaffold [Rees, D. C., et al. (2005)]. Mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that specific residues such as α-His442 and α-Cys275 play a critical role in FeMoco binding and activity [Kaiser, J. T., et al. (2011)].

Cysteine (Cys275) directly coordinates the molybdenum atom in FeMoco, as demonstrated by Einsle et al. (2002) through high-resolution structural analysis. Similarly, Lancaster et al. (2011) identified histidine (His442) as crucial for stabilizing FeMoco, with its coordination role further supported by spectroscopic evidence. These residues ensure the proper positioning and electronic configuration of FeMoco.

(2) Stabilization via Hydrogen Bonding: Serine and threonine (Thr252) contribute to the stabilization of FeMoco through hydrogen bonding, as highlighted by Spatzal et al. (2016). Asparagine (Asn335) also plays a significant role by forming hydrogen bonds that stabilize the cofactor environment, as discussed by Howard and Rees (1994).

(3) Hydrophobic Environment: Hydrophobic residues such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine create a protective environment around FeMoco, shielding it from solvent interactions. Rees and Howard (2000) emphasized the importance of these residues in preserving the cofactor's reactivity and stability.

(4) Electron Transfer Modulation: Glutamate (Glu240) is critical for electron transfer within nitrogenase, as described by Danyal et al. (2011). This residue modulates electron density, facilitating efficient electron transfer from the Fe protein to FeMoco, a key step in nitrogen fixation.

(5) Indirect Support by Lysine and Arginine: Lysine and arginine residues indirectly support FeMoco by stabilizing the surrounding hydrogen bond network, as noted by Seefeldt et al. (2009). These residues contribute to the overall stability and functionality of the cofactor.

(6) FeMoco Assembly: FeMoco assembly occurs through a multi-step biosynthetic pathway involving chaperone proteins that mediate cluster maturation and insertion into the MoFe protein [Rubio, L. M., & Ludden, P. W. (2005)]. Studies using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) have provided insights into the electronic structure of FeMoco and its redox properties [Bjornsson, R., et al. (2017)]. Additionally, computational modeling has identified potential conformational changes that regulate FeMoco insertion and catalytic efficiency [Dance, I. (2013)].

(7) Engineering Nitrogenase Variants: Understanding FeMoco binding and stability opens avenues for engineering nitrogenase variants with improved efficiency and alternative metal cofactors. This intricate network underscores the evolutionary sophistication of nitrogenase. Recent advancements in artificial nitrogenase design, including single-subunit light-driven nitrogenase, highlight the potential for synthetic biology approaches to enhance biological nitrogen fixation [Hu, Y., et al. (2019); Raugei, S., et al. (2018)].

2.4. Pchlide docking with single-subunit LPOR

Although various tetrapyrrole cofactors (e.g., bilin, coenzyme B12) can act as photoreceptive pigments in light sensing, only chlorophyll (and certain related derivatives) have been found to participate in biological photocatalysis [Taylor et al., 2022].

Chlorophyll is the primary pigment responsible for capturing light energy in photosynthetic organisms, with the reduction of the C17=C18 double bond in protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) being a critical step in forming chlorophyllide (Chlide). This reaction is catalyzed by light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR), which utilizes light energy to drive the reduction process.

Additionally, RDH catalyzes the conversion of retinol to retinal, which in bacteriorhodopsin undergoes photoisomerization (

Figure 10a) to induce conformational changes in the protein, driving proton translocation across the membrane (

Figure 10b) and generating a proton gradient to support energy conversion [Lanyi and Luecke, 2001].

Understanding the photochemical mechanisms of LPOR and the role of retinal in proton pumping is essential for optimizing photosynthetic efficiency and advancing sustainable agricultural practices.

The reaction mechanism of LPOR involves a series of light-dependent steps, including the excitation of Pchlide, hydrogen transfer, and proton transfer.

(1) Light Absorption and Excitation: LPOR absorbs light, exciting Pchlide from its ground state (S0) to an excited state (S1 or S2). This excitation is crucial for initiating the reduction process. The excited Pchlide undergoes internal conversion (IC) and internal conversion fluorescence (ICF) to dissipate excess energy and stabilize in the S1 state [Heyes et al., 2009].

(2) Hydrogen Transfer (HYT): The excited Pchlide accepts a hydride (H⁻) from NADPH, transferring it to the C17 position of Pchlide. This step is rapid, with a rate constant of approximately 2.0 × 10⁶ s⁻¹. This hydrogen transfer results in the formation of a Pchlide-H⁻ intermediate, with NADP+ as a byproduct.

(3) Proton Transfer (PT): A proton (H⁺) is transferred from a tyrosine residue (usually Tyr189 or Tyr193) to the C18 position of Pchlide. This step is slower, with a rate constant of approximately 2.9 × 10⁴ s⁻¹. The proton transfer completes the reduction of Pchlide to Chlide, which is the precursor to chlorophyll [Taylor et al., 2024].

(4) Product Formation and Enzyme Regeneration: The reduced Pchlide (Chlide) is released from the enzyme, and the enzyme returns to its initial state, ready for another catalytic cycle. This process is essential for the continuous functioning of LPOR [Silva & Cheng, 2022].

Recent structural studies, including X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), have provided detailed views of the LPOR active site and the binding of Pchlide and NADPH. These studies have revealed the importance of specific amino acid residues in the catalytic process. Tyr189 and Tyr193 are crucial for proton transfer, although recent studies suggest that they may not directly donate the proton but rather stabilize the Pchlide intermediate [Taylor et al., 2024]. Cys226 has been proposed as a potential proton donor, with recent studies indicating its involvement in both hydrogen and proton transfer steps [Heyes et al., 2009]. Gln248 interacts with the central Mg atom of Pchlide, tuning its electronic properties and facilitating efficient photochemistry [Silva & Cheng, 2022; Pesara, et al. (2024)].

Computational methods, such as molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, have been instrumental in understanding the dynamics and energetics of the LPOR reaction mechanism. These studies have provided insights into the binding modes of Pchlide and the roles of key residues in the catalytic process [Menon et al., 2010; Pesara, et al. (2024)].

The detailed understanding of the LPOR reaction mechanism has significant implications for chlorophyll biosynthesis and photosynthesis. Efficient reduction of Pchlide to Chlide is essential for the formation of chlorophyll, which in turn affects the efficiency of light capture and energy conversion in photosynthetic organisms. Enhancing the activity of LPOR could lead to improved photosynthetic efficiency and increased crop yields, particularly under suboptimal light conditions [Heyes et al., 2009].

To further elucidate the roles of these residues in the LPOR reaction mechanism and address controversies regarding their contributions, we performed a multiple sequence alignment of LPOR orthologs from various species. Highly conserved residues identified in the alignment were mapped onto the LPOR structure (PDB ID: 7JK9) for visualization. In this representation, strictly conserved residues were highlighted in bright red, while non-conserved or variable residues were depicted in cyan by default. Given that the substrate-binding pocket is located within the protein interior, a layered scanning approach was employed to analyze the spatial distribution of these residues (

Figure 11).

The first layer scan focused on the NADPH-binding region, revealing a cluster of conserved residues likely stabilizing cofactor binding and facilitating hydride transfer. The second layer scan targeted the Pchlide-binding pocket, highlighting conserved motifs around the porphyrin ring that may modulate substrate excitation and protonation. The third layer scan provided an overview of the entire structure, demonstrating the overall conservation pattern and its correlation with functional domains. Additionally, residues surrounding Pchlide were highlighted in PyMOL (

Figure 12a, orange region), all of which directly contact the substrate Pchlide. The corresponding positions of these residues in the sequence alignment have been indicated (

Figure 12b). This analysis underscores the evolutionary conservation of key active-site residues, supporting their critical role in catalysis.

Future research on LPOR should focus on: (1) Structural Dynamics – Investigating the dynamic changes in the LPOR active site upon light excitation and during the catalytic cycle; (2) Enzyme Engineering – Developing LPOR variants with enhanced activity and stability through rational design and directed evolution; (3) In Vivo Studies – Conducting in vivo studies to understand the physiological context of LPOR activity and its impact on plant growth and development.

2.5. FeMoco docking with engineered LPOR

Based on structural insights from nitrogenase-like proteins (DPOR and COR) and SDR-like proteins (RDH and LPOR), we designed a hypothetical, new light-driven electron transfer protein by incorporating FeMoco into the LPOR scaffold. Previous studies identified the substrate binding mode in the Pchlide-NADPH-LPOR complex and explored the reaction mechanism using quantum-chemical methods. These studies revealed how the LPOR active site promotes photo-driven reduction through initial electron transfer from Tyr189 to the substrate, then hydride transfer from NADPH and internal electron transfer from Cys222 to the deprotonated Tyr189 radical. Given the structural and functional similarities between nitrogenase-like proteins and LPOR, we hypothesized that FeMoco could be accommodated within the LPOR scaffold, enabling light-driven electron transfer to FeMoco, potentially eliminating the need for ATP-driven electron transfer observed in natural nitrogenases.

The key electron-transfer event in LPOR is facilitated by active-site amino acids rather than just the interplay of NADPH and Pchlide molecular orbitals. Considering the structural relationship between nitrogenase and DPOR, and the alignment of substrate binding sites, we hypothesized that the LPOR scaffold could accommodate FeMoco and catalyze light-driven electron transfer from Tyr189 to FeMoco.

FeMoco is covalently linked to nitrogenase through a His-Molybdenum bond and a Cys-Fe bond. In LPOR, the substrate binding cavity is partially occluded by a highly mobile loop containing a His residue, which we repurposed for FeMoco binding. Since no Cys exists at an appropriate position to bind the opposite end of FeMoco, we mutated Thr141 to Cys. By removing amino acids adjacent to the candidate His in the mobile loop, we obtained a modified LPOR model, designated FeMoco-loaded engineered LPOR (FL-LPOR), with His and Cys residues positioned to bind FeMoco [

Figure 13].

To better mimic the Arg-rich environment of natural nitrogenase, two Lys residues were replaced with Arg in FL-LPOR. The modeled structure of FL-LPOR is similar to LPOR, allowing for molecular docking with FeMoco at comparable positions. Molecular dynamics simulations (>500 ns each) tested the stability of FL-LPOR, showing that the protein remains stable with high mobility in the mobile loop and C-terminal portions. The distance between FeMoco and Cys222 remains short, suggesting a reliable electron transfer pathway. However, the distance between NADPH and FeMoco is more variable, indicating that the interaction with NADPH might need further optimization for consistent hydride donation to FeMoco.

Potential of mean force (PMF) graphs show that FeMoco entry into the LPOR cavity is thermodynamically favorable, with a negative energy change indicating spontaneous binding. This suggests that engineered LPOR can readily accommodate FeMoco, crucial for enabling subsequent catalytic reactions.

The minimum complement of

nif genes required for FeMoco biosynthesis and assembly varies [

Figure 14] [Cheng (1998)] [Cheng (2005)]. The NifEN protein complex is usually considered essential for FeMoco synthesis. However, Payá-Tormo et al. (2024) showed that a thermophilic Roseiflexus bacterium could assemble FeMoco without the scaffold NifEN. The study demonstrated that NifH, NifB, and apo-NifDK proteins produced in

E. coli were sufficient for FeMoco maturation and insertion into the NifDK protein. This finding challenges the conventional view and suggests that alternative pathways for FeMoco biosynthesis may exist [Xie et al., 2014; Shang et al., 2024; He et al., 2022; Payá-Tormo et al., 2024].

2.6. Predictions and Propelling Engineering

- 1)

N2ase-born FeMoco may shift from multi-subunit N2ase to single-subunit engineered LPOR in nitrogen fixation cyanobacteria, such as Anabaena;

- 2)

FeMoco-fitted LPOR-like LUN may have evolved in some cyanobacteria with superior nitrogen fixation ability, which requires further investigation;

- 3)

FeMoco-like LPOR-like LUN may have evolved in some C4 plants with superior growth rates, which requires further investigation.

On the other hand, positioning evolutionary events, organisms, and molecules in geological time, in an Earth Clock manner, may be helpful for understanding the visible past or somehow predictable future. However, while noting for certain that our planet Earth could have "full life" for another 100 years (

Figure 15), it may encounter unexpected events, such as natural disasters or existential threats from outer space.

As far as we can see, the visible images of the nitrogenase-related catalytic protein complex structures are nearly complete. A precise version, where scientists may be able to embark on achieving comparative results [Cheng (2008)] and more effectively [Taylor et al., 2022], is forthcoming.

2.7. AI-aid designing for non-natural LPOR

In the first strategy plan for reinventing a possible ancestral non-natural Light-Dependent Protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase (LPOR), we adopted a homology-guided design approach to construct the substrate-binding pocket—a critical domain for LPOR’s core function of catalyzing protochlorophyllide reduction. This design was rooted in comparative analysis of multi-subunit sequences from four evolutionarily related enzymes: Dark-Operative Protochlorophyllide Oxidoreductase (DPOR), Chlorophyllide Oxidoreductase (COR), Nitrogenase (N₂ase), and F₄₃₀-dependent Methyl-Coenzyme M Reductase. These enzymes share conserved structural folds and redox-active cofactor-binding regions, making their sequences a reliable template to infer the ancestral LPOR’s substrate-interacting residues. By aligning conserved motifs across these homologs and mapping residue positions critical for substrate coordination (e.g., hydrophobic pockets and polar interaction sites), we generated a preliminary substrate-binding pocket model that balances ancestral sequence features with LPOR’s specific substrate preferences.

Complementing this, we incorporated two key elements to establish a functional electron transfer chain—essential for LPOR’s redox catalysis. First, we integrated the NADPH-binding motif, a universally conserved domain in reductases that enables binding of the NADPH cofactor (the primary electron donor for LPOR). Second, we included the YKDSK motif, a sequence identified in homologous redox enzymes (e.g., DPOR and N₂ase) that mediates electron transfer between the cofactor and the active site via conserved lysine and aspartate residues. Together, these motifs formed a predicted electron transfer pathway, linking NADPH oxidation to substrate reduction in the ancestral non-natural LPOR.

To validate and illustrate this design process,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 provide visualizations of the reconstructed substrate-binding pocket—showing residue alignments with homologs, predicted substrate (protochlorophyllide) docking, and key interaction sites (e.g., hydrogen bonds between pocket residues and substrate functional groups). Meanwhile,

Supplementary Table 1 (S-table 1) compiles quantitative data supporting the design: including sequence conservation scores of pocket residues across DPOR/COR/N₂ase/F₄₃₀ homologs, predicted binding affinities of the reconstructed pocket for protochlorophyllide (calculated via molecular docking simulations), and alignment statistics for the NADPH-binding and YKDSK motifs. Collectively, these figures and the table serve as concrete examples of how we translated evolutionary sequence data into a testable model of an ancestral non-natural LPOR, bridging structural homology with functional enzyme design.

2.8. de novo Light-driven catalysts: LUN、LCOR、L430

This paper introduces the entire history of thirty years of effort in the structural elucidation of the ancient anaerobic enzyme nitrogenase, the nitrogenase-like DPOR protein complex, and their ancestral F430 reductase. The comparison of these nitrogenase-like catalysts has been demonstrated in terms of structural complexes, mechanistic illustration, and substrates and products (

Figure 6). Evolutionary relationships with nitrogenase-like catalysts and the structural implications of light-utilizing nitrogenase (LUN) are shown in

Figure 16.In turn, focusing on the evolutionary invention of the remarkable enzyme LPOR and its position in the geological age on the 'Earth clock' (

Figure S3), we look forward to the discovery or invention of a greater masterpiece, the LUN. Additionally, several other higher-version catalysts (LCOR, L430) could potentially be designed from the lower-version ones (COR, F430) (

Figure 16,

Table 1).Key catalysts for nitrogen reduction and porphyrin reduction have been summarized in

Table 1.

Based on the successful evolutionary story of LPOR from DPOR, and the preliminary evidence we provide, one could postulate that the so-far theoretical higher versions of catalysts may be able to be designed from the lower version ones (

Figure 15). At present, it still seems very ambitious and bold, but no less scientific, proposing that there may be a completely undiscovered novel nitrogenase or a designable LUN that could appear somewhere on the Earth Clock [Cheng (2013)]. However, the central aim of this paper is to ask whether the evolutionary and structural legacy of the nitrogenase-like protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (POR) could guide the future of biological nitrogen fixation with a light-utilizing nitrogenase (LUN). This could revolutionize biological nitrogen fixation engineering.

In this aspect, there may be two opposite opinions. One may be scientifically seeking more support: a) comparative implications; b) chemical engineering; c) synthetic biology; d) In the near future, molecular design work may be carried out using gigantic quantum assimilation technologies or AI-aided and structural mimicking approaches (in fact, we have already developed a set of highly evolved de novo nitrogenase-related catalysts [LUN, LCOR, L430] as ancestral versions) (S-table 1).

On the other hand, particularly for LUN, a philosophical objection may be: a) chemically impossible; b) why hasn’t it dominated the plant kingdom so far; c) wait for another billion years according to the Earth Clock [Cheng (2013)].

This paper uses AlphaFold to predict the structure of the representative LPORs from the LPOR phylogenetic tree and analyzes the factors affecting the efficiency of protein activity based on the structure. At the same time, based on comparative analysis, we propose relevant design schemes for LUN and look forward to its continuous improvements. Preliminary results on AI-designed non-natural LCOR can be seen [Sun XZ et al. (2025)].

In the near future, AI technology may have great potential to cope with gigantic structural optimization for specific substrate targets, such as Chlide a or a FeMoco-like cage for N₂, etc. After all, there may still be a long way down this road and technical difficulties in designing such de novo enzymes biochemically and biologically, but as the pioneer Professor Ray Dixon once said, we cannot afford not to try it for the cause of agricultural food production, ultimately sustaining burgeoning world populations.

Minimum nif genes

required for FeMoco biosynthesis and assembly.

Minimum nif genes

required for FeMoco biosynthesis and assembly.

Minimum nif genes

required for FeMoco biosynthesis and assembly.

Minimum nif genes

required for FeMoco biosynthesis and assembly.