1. Introduction

Hypertension remains the leading preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) globally, representing a critical public health challenge that necessitates advanced therapeutic strategies [

1,

2,

3]. By 2024, approximately 1.4 billion people worldwide were living with hypertension, with only about 20% of cases adequately controlled [

4,

5]. The number of adults aged 30–79 years with hypertension has doubled from 1990 to 2019, now exceeding 1.28 billion individuals [

6,

7]. Uncontrolled hypertension contributes to approximately 8.5 million deaths annually from stroke, ischemic heart disease, and kidney failure [

8,

9,

10]. This substantial disease burden underscores the urgent need for developing improved antihypertensive agents with optimized therapeutic profiles.

Dihydropyridine (DHP) Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs) represent a cornerstone class of antihypertensive medications that function primarily as peripheral vasodilators [

11,

12,

13]. They exert their therapeutic effect by binding to the voltage-gated L-type calcium channels (CaV1.2) in vascular smooth muscle, thereby inhibiting calcium influx and preventing vasoconstriction [

14,

15]. These channels contain five different subunits (α1, α2, β, δ, γ), with the α1 subunit forming the primary ion conduction pore and drug binding site [

14,

15]. Despite sharing the fundamental 1,4-dihydropyridine scaffold, commercially available DHP drugs demonstrate significant clinical variability in their efficacy, elimination half-life, and drug interaction potential [

16,

17]. The precise structural determinants—how specific modifications to the DHP core influence receptor binding kinetics and overall pharmacological behavior—remain incompletely characterized at the molecular level [

17,

18].

Previous computational studies have primarily focused on affinity prediction [

19,

20], but the current work advances the field by integrating molecular docking data (binding affinity and pose) with comprehensive ADME predictions (metabolism and plasma protein binding) to elucidate the structural features responsible for observed clinical variations among DHP CCBs. This multifaceted in silico approach establishes a robust structure-activity relationship that simultaneously accounts for both target engagement and systemic drug disposition, thereby addressing a significant gap in the current computational pharmacology landscape.

2. Results

2.1. Preparation of Protein and Validation of Computational Model

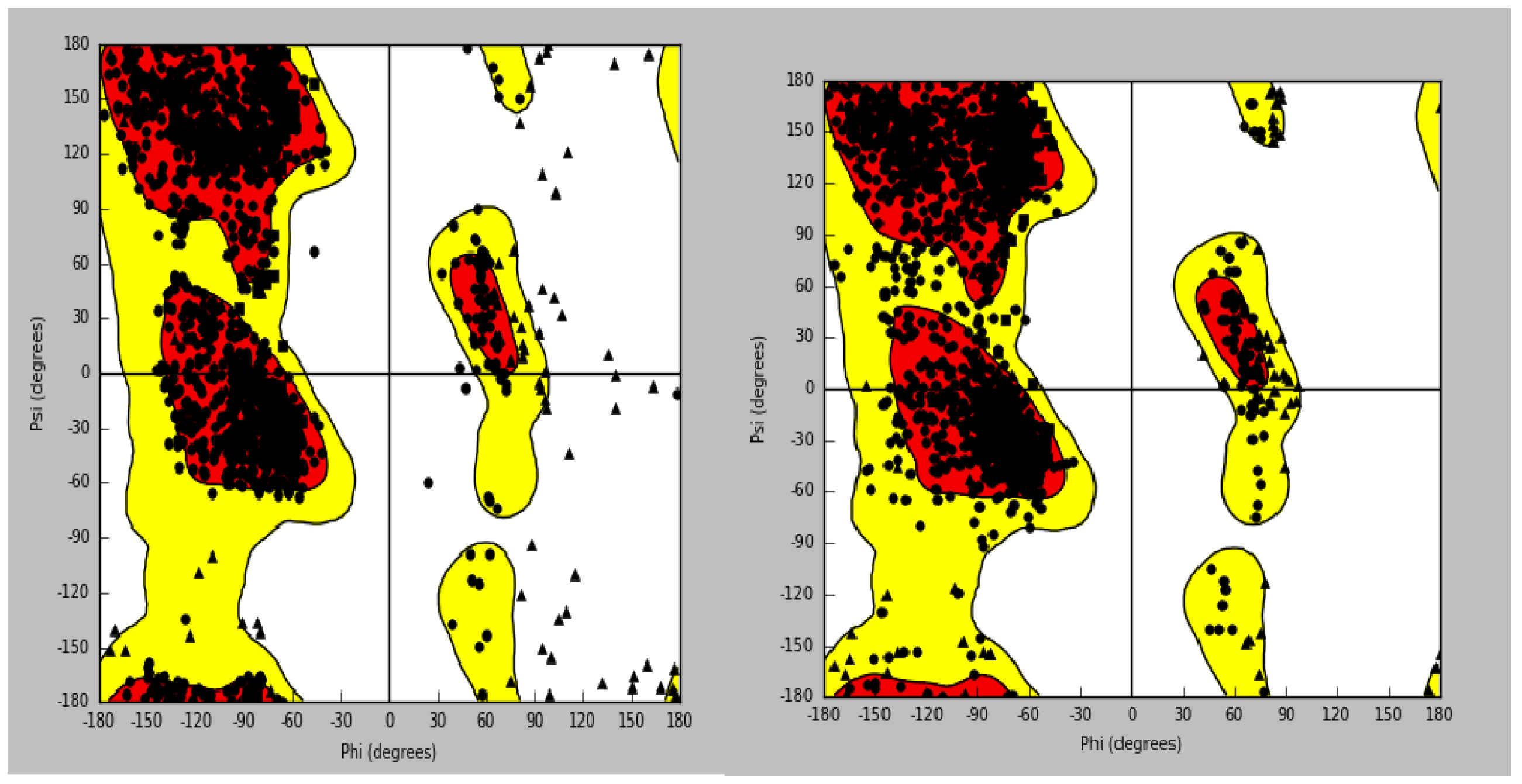

Human CaV1.2 channel structure (PDB ID: 8WE8) was cleaned for further computational analysis. Ramachandran plot quality check indicated a significant stereochemical improvement in the protein. Upon preparation, the vast majority of residues were located within the most favoured regions, with a very minor number of residues in the allowed regions, reflecting high-quality structural model for docking studies (

Figure 1A and 1B). To attest to the reliability of the docking protocol, the ligand amlodipine was re-docked into its site. The generated ligand interaction graph was compared to the one seen after the first protein preparation. This affirmed a full replication of notable interactions, i.e., the hydrogen bonds of amlodipine with the residues SER1132 and ALA1174. The reproducibility guarantees the stability of the prepared model and the ensuing docking protocol.

2.2. Conserved Hydrogen Bonding with SER1132 is a Hallmark of DHP Binding

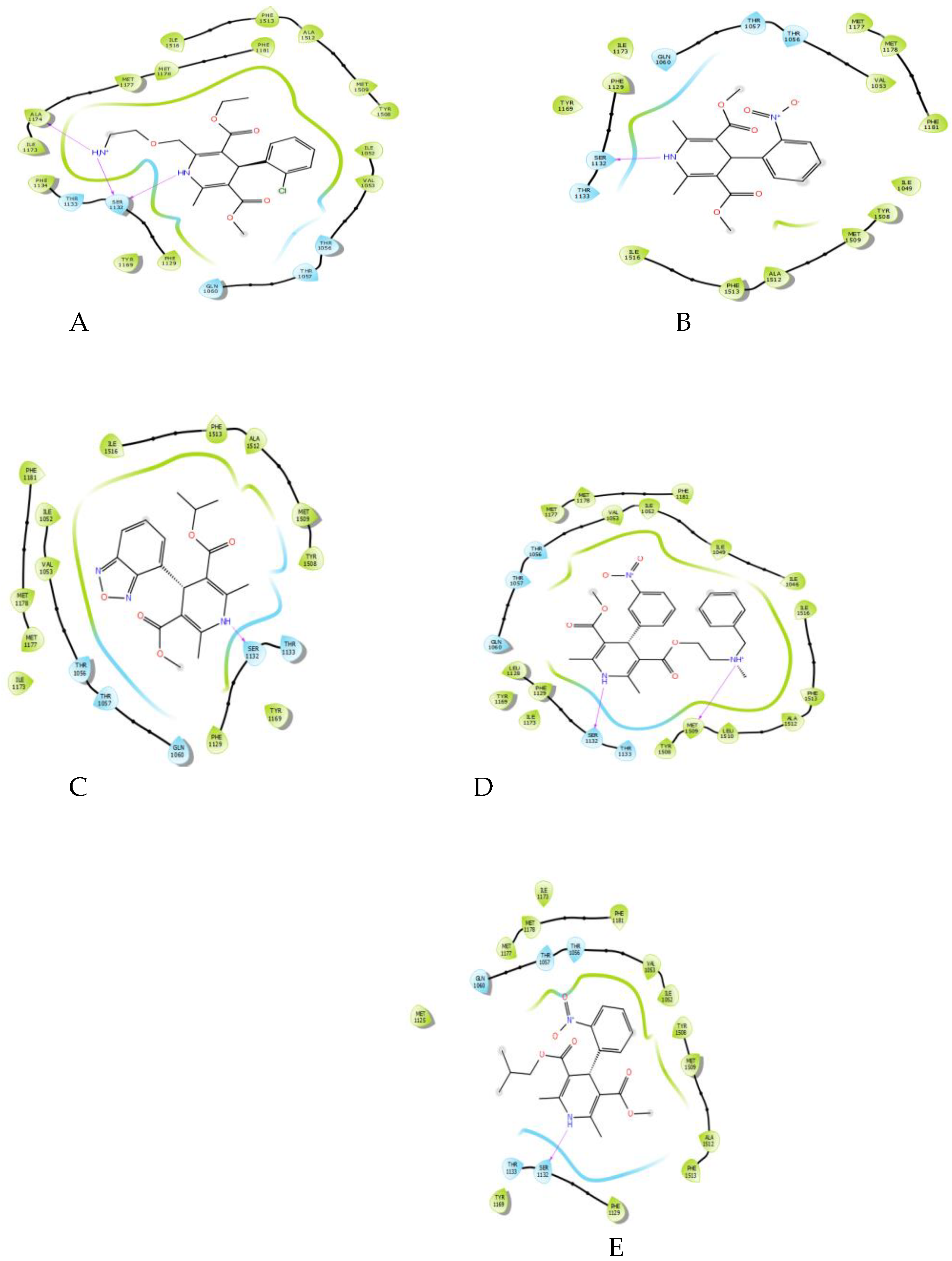

Molecular docking of the five DHP drugs—amlodipine, nifedipine, isradipine, nicardipine, and nisoldipine—yielded a universal and necessary interaction for all complexes: a hydrogen bond between the secondary amine on the 1, 4-dihydropyridine ring and the hydroxyl of residue SER1132 (

Figure 2). This interaction was observed in all ligand-protein complexes, highlighting its pivotal role in fixing the DHP scaffold into place within the binding pocket. While the number of additional hydrogen bonds varied (amlodipine fixed one to ALA1174, and nicardipine to MET1509), the SER1132 interaction was the only recurring polar interaction, highlighting its conserved importance.

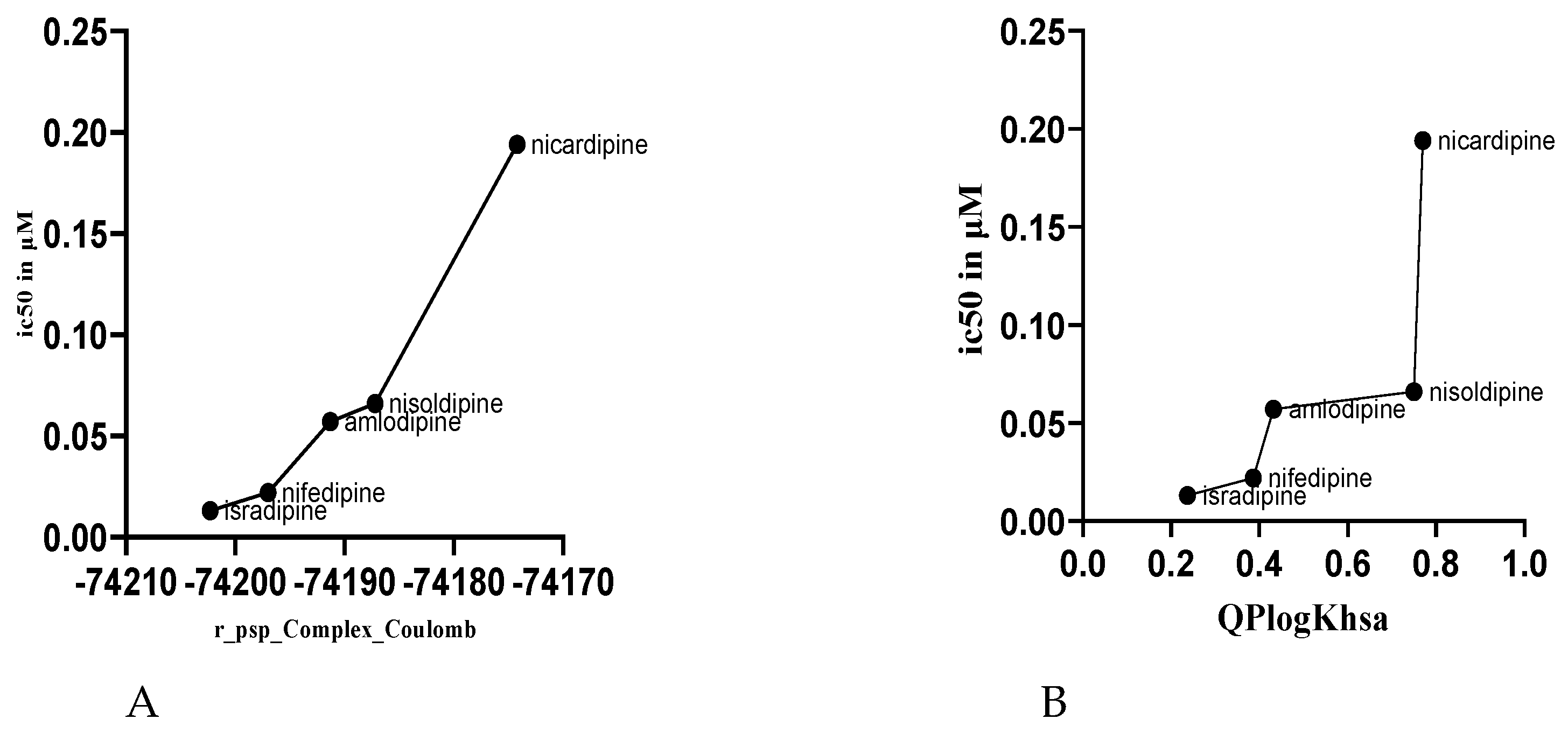

2.3. Critical Energetic and Physicochemical Parameters are Correlated with Experimental Potency

To elucidate the structural basis of the differential experimental IC₅₀ values of the DHP drugs, the computed binding energies and physicochemical descriptors were analyzed for correlations against biological activity. A striking inverse correlation was observed for calculated Coulombic (electrostatic) interaction energy (r_psp_Complex_Coulomb) and experimental IC₅₀ (

Table 1,

Figure 3A). The most active drug, isradipine (IC₅₀ = 0.013 µM), possessed the most favorable (most negative) Coulombic energy, while the least active, nicardipine (IC₅₀ = 0.194 µM), possessed the least favorable value.

Conversely, the highest correlation was with human serum albumin predicted binding affinity (QPlogKhsa) and IC₅₀ (

Table 1,

Figure 3B). The most active compound was isradipine, with the lowest QPlogKhsa of 0.237, whereas the least active compound was nicardipine, with the highest QPlogKhsa of 0.770.

Interestingly, the distance of the hydrogen bond to SER1132 was inversely proportional to IC₅₀ (

Table 1) in that the more active compounds possessed higher bond distances. The remaining calculated parameters, including the van der Waals energy term (r_psp_Ligand_vdW), the hydrogen bonding term (MMGBSA_dG_Bind_Hbond), and the total binding free energy (r_psp_MMGBSA_dG_Bind), were found not to exhibit a simple, linear correlation to the experimentally obtained IC₅₀ values.

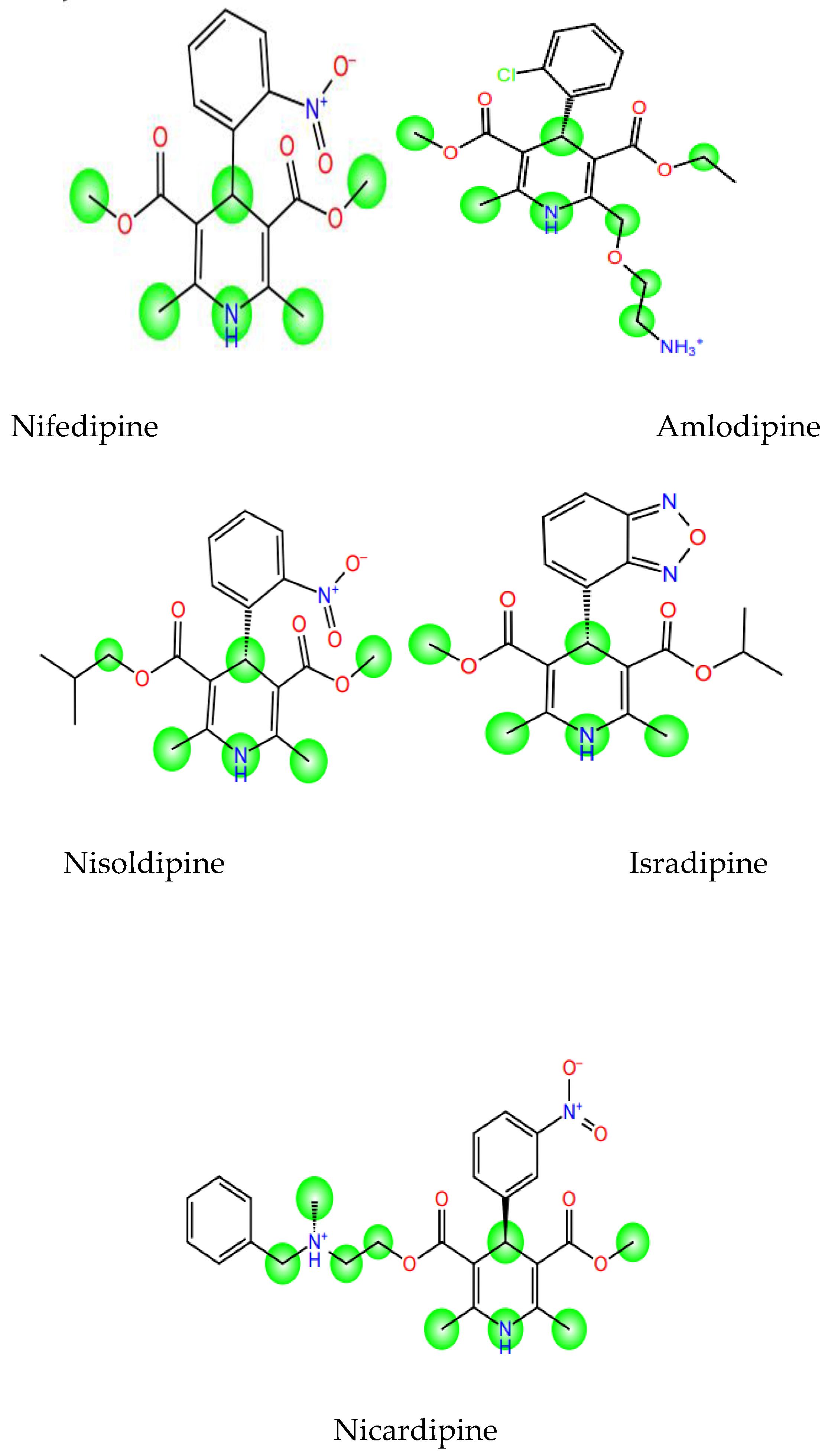

2.4. Metabolic Site Prediction Identifies Differential Metabolic Liabilities

The in-silico SOM prediction of the CYP3A4 isoform revealed varying patterns among the DHP drugs (

Figure 4). Isradipine, the most potent and active drug, possessed fewer and less accessible sites of metabolism in its structure. The least potent drug, nicardipine, possessed more potential sites of metabolism, particularly on its ester side chains, indicating that it was more susceptible to enzymatic degradation.

3. Discussion

This extensive in silico study provides a robust structural and pharmacokinetic rationale for the differential activities of dihydropyridine (DHP) calcium channel blockers. By integration of molecular docking results with calculated ADME properties, we have established key determinants governing both target engagement and systemic disposition, a significant gap in the computational knowledge of this classic drug class.

The Crucial Role of SER1132 for Target Engagement and Binding Pose

A single conserved and prominent observation across all docked DHP ligands was the participation in a hydrogen bond with the serine residue at position 1132 (SER1132) of the CaV1.2 channel. This interaction, wherein the secondary amine of the 1,4-dihydropyridine ring acts as a hydrogen bond donor, is in agreement with previous mutagenesis and structural studies implicating serine residues within the pore-lining transmembrane helices as being critical for DHP binding [

26,

36]. Our results indicate that while this hydrogen bond is a conserved anchor, its geometry governs activity. Contrary to dogma of a more potent (shorter) hydrogen bond equating to higher potency, we observed an inverse correlation between SER1132 H-bond length and experimental IC₅₀ (Figure 3.10, Table 3.1). The most potent compound, Isradipine (IC₅₀ = 0.013 µM), possessed the longest H-bond (2.094 Å), while the less potent Nicardipine (IC₅₀ = 0.194 µM) had the shortest one (1.931 Å).

This would suggest that the primary function of the SER1132 H-bond is not to contribute importantly energetically to binding but to orient and position the DHP core correctly in the binding pocket, a notion that is favored in the work of Tang et al. [

25]. A specific, slightly weaker H-bond might allow an ideal geometry that optimizes other favorable interactions. MMGBSA_dG_Bind_Hbond energies, which were not clearly related to IC₅₀ (

Figure 3.13), further corroborate the observation that total hydrogen bonding energy is not the primary determinant of differential potency, underlining the role of this bond as a "director" of binding rather than its chief "stabilizer."

Coulombic Interactions as a Primary Determinant of Binding Affinity

The most predictive correlation to biological activity was with the Coulombic (electrostatic) term of the interaction energy (r_psp_Complex_Coulomb). Our findings illustrate a direct relationship between more negative (favorable) Coulombic energies and lower IC₅₀ values, which correspond to higher potency (Figure 3.11, Table 3.2). Isradipine, which exhibited the most favorable Coulomb energy (-74202.3 kcal/mol), was the most potent, whereas Nicardipine, which exhibited the least favorable (-74174.2 kcal/mol), was the least potent.

This finding is mechanistically revealing. The DHP binding pocket of CaV1.2 is lined by hydrophobic and polar residues [

26,

37]. The favorable Coulombic energy for Isradipine suggests that its specific substitution pattern optimizes electrostatic complementarity to the pocket, possibly through interactions with polar residues like Gln725 or Met909, which are known to contact DHPs [

38]. This strong, favorable electrostatic interaction directly enhances binding affinity and is a key structural determinant of the high potency of Isradipine.

The Contribution of Pharmacokinetics to Observed Activity: Distribution and Metabolism

Our model goes beyond simple affinity prediction by integrating ADME properties, illustrating how pharmacokinetics can impact in vivo efficacy. The prediction of human serum albumin (HSA) binding (QPlogKhsa) was correlated directly with IC₅₀ (

Figure 3.15). Isradipine, with the lowest QPlogKhsa (0.237), is expected to have less plasma protein binding, hence a greater free fraction to diffuse to the vascular smooth muscle and act on the CaV1.2 channel. Nicardipine, in contrast, with a high QPlogKhsa (0.77), is expected to have extensive serum albumin binding that sequesters the drug and reduces its free, pharmacologically active concentration, thereby reducing its apparent potency in vivo [

39,

40].

Further, analysis of the cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) sites of metabolism provided a metabolic stability rationale for the activities observed (

Figure 3.16). Isradipine was found to have fewer and less accessible predicted sites of metabolism compared to Nicardipine, which possessed multiple vulnerable sites. As CYP3A4 is the principal enzyme for the oxidative metabolism of DHP drugs [

35,

41], decreased metabolic lability translates to a longer half-life and systemic exposure for Isradipine. This heightened metabolic stability, in combination with its perfect distribution profile, is the foundation of its improved in vivo activity although its binding affinity may be comparable to other DHPs in a purified system.

Integration of Binding and Pharmacokinetic Profiles

The integration of binding and pharmacokinetics is nicely demonstrated by the comparison of the compounds. Isradipine emerges as the superior candidate since it possesses a synergistic profile: strong, favorable Coulombic interactions with the target, low plasma protein binding for ample free fraction, and high metabolic stability for extended duration of action. In contrast, Nicardipine is handicapped by less potent electrostatic interactions, high HSA binding, and high metabolic ability. This integrated view explains why drugs of similar in vitro binding affinities can exhibit very different clinical efficacies and dosing regimens [

42,

43].

Limitations and Future Directions

Among the limitations of this study are the staticness of the molecular docking and the MM-GBSA. While these methods provide important information, they do not provide the dynamic behavior of channel and ligand, e.g., state-dependent binding (preference for inactivated channels) characteristic for DHPs [

36,

43]. In future work, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations will be employed to examine the stability of the poses observed and the conformational changes upon ligand binding as a function of time. Furthermore, experimental confirmation of predicted ADME properties and binding affinities would be required to confirm these computational findings.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Computational Hardware and Software

All computational studies were performed using the Schrödinger Small-Molecule Drug Discovery Suite 2023-1 [

21]. Calculations were run on a local machine (HP EliteBook, Core i7 processor, 8.00 GB RAM). Protein structures were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [

22], and ligand structures were obtained from the Binding Database (BDB) [

23].

4.2. Protein Selection and Preparation

Fifteen co-crystallized structures of the L-type calcium channel (CaV1.2) were initially screened. The human CaV1.2 structure complexed with amlodipine (PDB ID: 8WE8), determined at a resolution of 2.9 Å and released in December 2023, was selected for this study due to its recent determination, human origin, and the presence of a clinically relevant DHP ligand [

24].

The protein structure was prepared using the Protein Preparation Wizard within Maestro [

25,

26]. The pre-processing step involved assigning bond orders, adding hydrogens, and creating zero-order bonds to metals. Missing side chains and loops were filled using the Prime module [

28]. Water molecules beyond 5 Å from heteroatoms were deleted [

21,

27]. The system was minimized using the OPLS3e force field [

29], converging heavy atoms to a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.30 Å, with PROPKA pH set to 7.0 to optimize the hydrogen-bonding network.

4.3. Ligand Preparation

The chemical structures of five DHP CCBs—Amlodipine, Nifedipine, Isradipine, Nicardipine, and Nisoldipine—were downloaded from the BDB in SDF format. Ligand preparation was conducted using the LigPrep module [

21]. Ionization states were generated at a physiological pH of 7.0 ± 2.0 using Epik, and possible stereoisomers were retained. Energy minimization was performed using the OPLS3e force field.

4.4. Molecular Docking

Receptor grid generation was performed using the Glide module [

30]. The centroid for the grid box (10 Å × 10 Å × 10 Å) was defined by the spatial coordinates of the co-crystallized amlodipine ligand extracted from the prepared 8WE8 structure. Molecular docking of the prepared DHP ligands was carried out using Glide in Extra Precision (XP) mode to accurately sample flexible ligand positions and score binding poses [

30,

31]. A flexible docking protocol was used, and up to 15 poses per ligand were generated for post-docking analysis.

4.5. Binding Free Energy Calculations

The binding free energies (ΔG_bind) for the protein-ligand complexes were estimated using the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) method as implemented in the Prime module [

32,

33]. The VSGB solvation model and the OPLS3e force field were employed. The calculations provided detailed energy components, including Coulomb energy, van der Waals energy, and hydrogen-bonding energy.

4.6. ADME Property and Site of Metabolism Prediction

Key pharmacokinetic properties, specifically the prediction of binding to human serum albumin (QPlogKhsa), were calculated using the QikProp tool [

34]. Furthermore, the potential sites of metabolism (SOM) for each DHP ligand were identified using the P450 Site of Metabolism module within Schrödinger, focusing on the CYP3A4 isoform, which is the primary metabolic enzyme for this drug class [

15,

35].

5. Conclusions

The present in silico investigation provides compelling computational evidence supporting the potential efficacy of the designed lead compounds as DHP CCBs. We have successfully addressed the structural diversity within DHP derivatives by establishing mechanistic correlations between computational binding geometry (including interactions with key residues) and predicted ADME properties (particularly CYP3A4 metabolism and HSA binding). These findings provide a robust foundation for future experimental validation and highlight promising candidates with optimized binding and pharmacokinetic profiles.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tinashe Sibamba and Glee C Muriravanhu; Methodology, Tinashe Sibamba and Roy T. Bisenti; Software, Tinashe Sibamba; Validation, Amos Misi, Glee C Muriravanhu and Dr Albert Wakandigara; Formal Analysis, Tinashe Sibamba and Roy T. Bisenti; Investigation, Tinashe Sibamba, Roy T. Bisenti, Dr. Albert Wakandigara and Glee C. Muriravanhu; Resources, Amos Misi; Data Curation, Tinashe Sibamba; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Tinashe Sibamba; Writing—Review & Editing, Amos Misi, Dr Paul Mushonga, Dr Albert Wakandigara, and Roy T. Bisenti; Visualization, Tinashe Sibamba, Glee C. Muriravanhu and Roy T. Bisenti; Supervision, Glee C. Muriravanhu and Amos Misi; Project Administration, Dr. Paul Mushonga.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study, including the prepared protein structure (PDB: 8WE8) and ligand files, are available within the article. The raw data supporting the docking scores and ADME predictions are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the University of Zimbabwe for providing the computational resources and software licenses necessary for this research. The authors have thoroughly reviewed, fact-checked, and edited the output and take full responsibility for the final content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CCBs |

Calcium Channel Blockers |

| DHPs |

Dihydropyridines (or Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockers) |

| MM-GBSA |

Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area |

| ADME |

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

References

- Narkhede, M.; Pardeshi, A.; Bhagat, R.; Dharme, G. Review on Emerging Therapeutic Strategies for Managing Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2024, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goorani, S.; Zangene, S.; Imig, J.D. Hypertension: A Continuing Public Healthcare Issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, A.; Zhu, A.; Gadela, N.V.; Prabhakaran, D.; Jafar, T.H. Social Determinants of Health and Disparities in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases. Hypertension 2024, 81, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytenew, T.M.; Kassaw, A.; Simegn, A.; Mihretie, G.N.; Asnakew, S.; Kassie, Y.T.; Demis, S.; Kefale, D.; Zeleke, S.; Asferie, W.N. Uncontrolled hypertension among hypertensive patients in Sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0301547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, M.S.; Ahmad, Q. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Approach for Hypertension to Improve Cardiac Health. Hemodynamics Hum Body [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/88039 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Lu, W.L.; Yuan, J.H.; Liu, Z.Y.; Su, Z.H.; Shen, Y.C.; Li, S.J.; Zhang, H. Worldwide trends in mortality for hypertensive heart disease from 1990 to 2019 with projection to 2034: data from the Global Burden of Disease 2019 study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024, 31, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Lin, H. Global Burden of Hypertensive Heart Disease and Modifiable Risk Factors: A 30-Year Systematic Analysis of Prevalence, Mortality, and Disability-Adjusted Life Years (1990–2021). Curr Sci. 2025, 5, 4596–620. [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH. Global report on hypertension: the race against a silent killer [Internet]. World Health Organization, 2023. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=KaIOEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Uncontrolled+hypertension+contributes+to+approximately+8.5+million+deaths+annually+from+stroke,+ischemic+heart+disease,+and+kidney+failure&ots=AlfsfzMePF&sig=XC1qae64zXPA01HhqRrkB__RziE (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Miller, E. Prevention of Uncontrolled Hypertension [Internet]. PhD Thesis, University of Phoenix, 2025. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/82863b0a94d7e23fa0f49e0f83613556/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Alrashed, S.F.M.; Alruwaili, R.R.M.; Alrwaili, N.A.K.; Alruwaili, R.J.F.; Alhazmi, G.A.A.; Alruwaili, S.A.D. Hypertension and Heart Health. Gland Surg. 2024, 9, 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Shuvo, P.S. A review on calcium channel blockers as an effective treatment strategy for hypertension [Internet]. PhD Thesis, Brac University, 2023. Available online: https://dspace.bracu.ac.bd/xmlui/handle/10361/23953 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Lee, E.M. Calcium channel blockers for hypertension: old, but still useful. Cardiovasc. Prev. Pharmacother. 2023, 5, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Hayden, S.L.; Meyer, H.R.; Sandoz, J.L.; Arata, W.H.; Dufrene, K.; Ballaera, C.; Torres, Y.L.; Griffin, P.; Kaye, A.M.; et al. The Evolving Role of Calcium Channel Blockers in Hypertension Management: Pharmacological and Clinical Considerations. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 6315–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosmang, S.; Schulla, V.; Welling, A.; Feil, R.; Feil, S.; Wegener, J.W.; Hofmann, F.; Klugbauer, N. Dominant role of smooth muscle L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 for blood pressure regulation. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 6027–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striessnig, J.; Ortner, N.; Pinggera, A. Pharmacology of L-type Calcium Channels: Novel Drugs for Old Targets? Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2015, 8, 110–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi Sri, C.; Beeraka, N.M.; Ramachandrappa, H.V.P.; Bidye, D.P.; Prashantha Kumar, B.R.; Nikolenko, V.N.; et al. Updates on Intrinsic Medicinal Chemistry of 1,4-dihydropyridines, Perspectives on Synthesis and Pharmacokinetics of Novel 1,4-dihydropyrimidines as Calcium Channel Blockers: Clinical Pharmacology. Curr Top Med Chem. 2025, 25, 1351–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioan, P.; Carosati, E.; Micucci, M.; Cruciani, G.; Broccatelli, F.; Zhorov, B.S.; Chiarini, A.; Budriesi, R. 1,4-Dihydropyridine Scaffold in Medicinal Chemistry, The Story so Far And Perspectives (Part 1): Action in Ion Channels and GPCRs. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4901–4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triggle, D.J.; Rampe, D. 1,4-Dihydropyridine activators and antagonists: structural and functional distinctions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1989, 10, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Basak, H.K.; Paswan, U.; Pramanik, A.K.; Chatterjee, A. Designing of next-generation dihydropyridine-based calcium channel blockers: An in silico study. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinnejad, T.; Omrani-Pachin, M.; Heravi, M.M. Joint Computational and Experimental Investigations on the Synthesis and Properties of Hantzsch-type Compounds: An Overview. Curr. Org. Chem. 2019, 23, 1421–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.; Kumar, A. Structural-based Study to Identify the Repurposed Candidates against Bacterial Infections. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 3693–3718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, H.M.; Westbrook, J.; Feng, Z.; Gilliland, G.; Bhat, T.N.; Weissig, H.; et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lin, Y.; Wen, X.; Jorissen, R.N.; Gilson, M.K. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D198–D201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, G.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q.; Gao, S.; Yan, Z.; Lei, J.; Yan, N. Molecular Basis for Ligand Modulation of a Mammalian Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channel. Cell 2019, 177, 1495–1506.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; El-Din, T.M.G.; Swanson, T.M.; Pryde, D.C.; Scheuer, T.; Zheng, L.; Catterall, W.A. Structural basis for inhibition of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel by Ca2+ antagonist drugs. Nature 2016, 537, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastry, G.M.; Adzhigirey, M.; Day, T.; Annabhimoju, R.; Sherman, W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, M.P.; Pincus, D.L.; Rapp, C.S.; Day, T.J.F.; Honig, B.; Shaw, D.E.; Friesner, R.A. A hierarchical approach to all-atom protein loop prediction. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2004, 55, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harder, E.; Damm, W.; Maple, J.; Wu, C.; Reboul, M.; Xiang, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Lupyan, D.; Dahlgren, M.K.; Knight, J.L.; et al. OPLS3: A Force Field Providing Broad Coverage of Drug-like Small Molecules and Proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 1. Method and Assessment of Docking Accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A.; Murphy, R.B.; Friesner, R.A.; Beard, H.S.; Frye, L.L.; Pollard, W.T.; Banks, J.L. Glide: A New Approach for Rapid, Accurate Docking and Scoring. 2. Enrichment Factors in Database Screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1750–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, P.D.; Lamb, M.L.; Saeh, J.C. Accurate Prediction of the Relative Potencies of Members of a Series of Kinase Inhibitors Using Molecular Docking and MM-GBSA Scoring. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 4805–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Duffy, E.M. Prediction of drug solubility from structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002, 54, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Afzelius, L.; Grimm, S.W.; Andersson, T.B.; Zauhar, R.J.; Zamora, I. Comparison of methods for the prediction of the metabolic sites for cyp3a4-mediated metabolic Reactions. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006, 34, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockerman, G.H.; Peterson, B.Z.; Johnson, B.D.; Catterall, W.A. Molecular determinants of drug binding and action on l-type calcium channels. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1997, 37, 361–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.; Yan, C.; Lu, S.; Dong, M.; Yan, N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Ca v 1.1 complex. Science 2015, 350, aad2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorum, H. Reversible ligand binding to human serum albumin. Theoretical and clinical aspects. Dan Med Bull. 1999, 46, 379–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ascenzi, P.; Fasano, M. Allostery in a monomeric protein: The case of human serum albumin. Biophys. Chem. 2010, 148, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guengerich, F.P. Cytochrome P450 and Chemical Toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edraki, N.; Mehdipour, A.R.; Khoshneviszadeh, M.; Miri, R. Dihydropyridines: evaluation of their current and future pharmacological applications. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 1058–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, F.E.; C, S.; Feng, T.; Barakat, K. Effects of selective calcium channel blockers on ions’ permeation through the human Cav1.2 ion channel: A computational study. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2021, 102, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findeisen, F.; Minor, D.L., Jr. Progress in the structural understanding of voltage-gated calcium channel (CaV) function and modulation. Channels 2010, 4, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).