1. Introduction

High G maneuvers (9–10 +Gz) in advanced aircraft can cause G-LOC due to reduced cerebral blood flow, leading to 20 seconds of unconsciousness and minutes-long recovery. This endangers flight safety, especially during precision maneuvers. U.S. Air Force data reports 559 G-LOC cases, with 30–50 annual crashes linked to it. Post-G-LOC symptoms include cognitive impairment, headaches, and vision issues, highlighting the need for better pilot training to mitigate risks.

Real-world flight training is crucial for enabling pilots to develop the ability to withstand high-G loads and reduce the risk of G-LOC. However, this training entails inherent safety risks, and the rapid variations in acceleration make it difficult to measure the forces experienced precisely. This challenge complicates the assessment of training program effectiveness. To address these limitations, high-performance human centrifuges (HPHC) have emerged as invaluable tools for simulating high-G conditions in a controlled environment. By providing realistic high-G exposures, HPHC allows pilots to gradually adapt to the physiological stresses of high-G environments, thereby improving their tolerance and reducing the incidence of G-LOC during actual flights.

HPHC training is typically overseen by aeromedical operators, who continuously monitor the pilots through video surveillance that records the pilots’ real-time images. Based on the responses of the trainees, the training intensity can be adjusted to optimize performance while minimizing the risk of G-LOC. Ideally, training should be halted as soon as symptoms of G-LOC are identified, such as lack of eye contact, increased facial stress, or mild muscle tension in the face. AO issued a medical stop order when early signs were detected, halting the centrifuge from continuing to exert acceleration. However, G-LOC often develops subtly and may occur before any obvious symptoms become apparent. The rapid progression and transient nature of these early signs make it exceptionally challenging for aeromedical operators (AO) to detect and interpret them in real time, even with extensive experience.

Owing to enhanced signal-to-noise ratio and information transfer rate, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and electroencephalogram (EEG) technology have been increasingly applied in neural state monitoring in recent years [

1]. Recent studies have employed machine learning to analyze biosensor data for objectively assessing an individual’s state in PTSD, moving beyond traditional self-reporting methods [

2]. Similar to this approach, G-LOC research leverages biosensor data to detect pre-syncopal autonomic nervous system instability, providing a parallel for using physiological markers rather than self-reports for objective diagnosis. In an effort to reduce reliance on subjective human judgment among aeromedical operators, researchers have explored the use of machine learning techniques to predict G-LOC. Current methods for G-LOC prediction often depend on sensor-based equipment, such as EEG [

3,

4], electromyography (EMG) [

5], and eye tracking devices [

6]. Notably, pupil diameter and EEG features, particularly the power measured at the parietal site, were identified as critical indicators for the early detection of G-LOC [

7]. Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of combining physiological indicators with physical manifestations to assess a pilot’s precursor state of consciousness. Despite these advancements, current methods often rely on sensor-based equipment, which can interfere with training and limit practicality [

8]. Despite the performance advantages of deep learning algorithms, their deployment on mobile and wearable devices faces challenges due to limited computational power, memory capacity, and battery life, which restrict the local execution of complex models. Moreover, the reliance on multiple sensors increases operational complexity and cost, limiting the scalability of these solutions [

9].

The inherent challenges in detecting early signs of G-LOC during high-G training highlight the need for more nuanced physiological monitoring systems. While AO traditionally rely on observable symptoms like facial tension or loss of eye contact, these indicators often appear too late to prevent an impending loss of consciousness. This is where Facial Action Coding System (FACS) AUs based micro-expression analysis can play a transformative role [

10]. By focusing on subtle, involuntary facial muscle movements that precede overt symptoms, AUs analysis provides a more granular and objective assessment of a pilot’s physiological state.

Microexpressions captured through AU coding, such as brow furrowing or eyelid tightening, can serve as early biomarkers of cerebral hypoxia long before conscious impairment becomes apparent. These micro-level facial actions are difficult for human observers to consistently detect in real time due to their fleeting nature, but computer vision algorithms trained in AU recognition can identify these patterns with high precision. When integrated with existing monitoring systems, AU analysis could enable earlier intervention by correlating specific facial action units with declining cognitive function.

The application of AU analysis in this context represents a shift from reactive to predictive monitoring. By detecting the earliest physiological precursors to G-LOC often before the pilot is even aware of them, this technology could provide critical extra seconds for preventive measures. As high-performance aviation continues to push physiological limits, such advanced biometric monitoring may become indispensable for maintaining pilot safety during extreme maneuvers. The integration of AU-based systems with traditional aeromedical oversight could significantly reduce G-LOC-related risks while optimizing high-G training protocols.

To address these limitations, we propose an innovative, image-based method for real-time G-LOC prediction during HPHC training. Unlike existing sensor-based approaches, we propose a novel Vision Transformer (ViT) framework for AU feature extraction. The core innovation lies in its visual-semantic collaborative modeling architecture, which effectively integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with vision Transformers. Specifically, the framework employs ResNet at the bottom layer to process image sequences, capturing spatiotemporal dynamics of facial microexpressions. Leveraging the long-range interaction capabilities of self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms in Transformers, we introduce a semantic-embedded label query network and an instance-conditioned code language model. The label query network adopts an encoder-decoder structure, where each AU label is represented as a learnable query.

Furthermore, we develop a graph convolutional hybrid network tailored for G-LOC prediction. This network innovatively combines graph convolution with physiological prior knowledge to construct an AU correlation graph. By incorporating a dynamic graph learning mechanism, the model adaptively adjusts inter-AU relationship strengths while preserving physiological plausibility.

To address these problems and build upon previous experiences, a new method for G-LOC detection based on facial action units is proposed. The contributions are as follows:

We introduce the pioneering non-invasive, sensor-free G-LOC prediction system leveraging AUs as physiological biomarkers. In contrast to traditional methods requiring physical attachments, our framework relies uniquely on RGB cameras to capture subtle microexpressions related to AU linked to cerebral hypoxia.

We propose a novel vision-semantics collaborative Transformer for AU feature extraction, combining spatiotemporal modeling with the attention mechanisms of Transformer’s. By encoding each AU label as a learnable query, which dynamically interacts with visual features via cross-attention, our approach achieves precise AU recognition even under high-stress conditions.

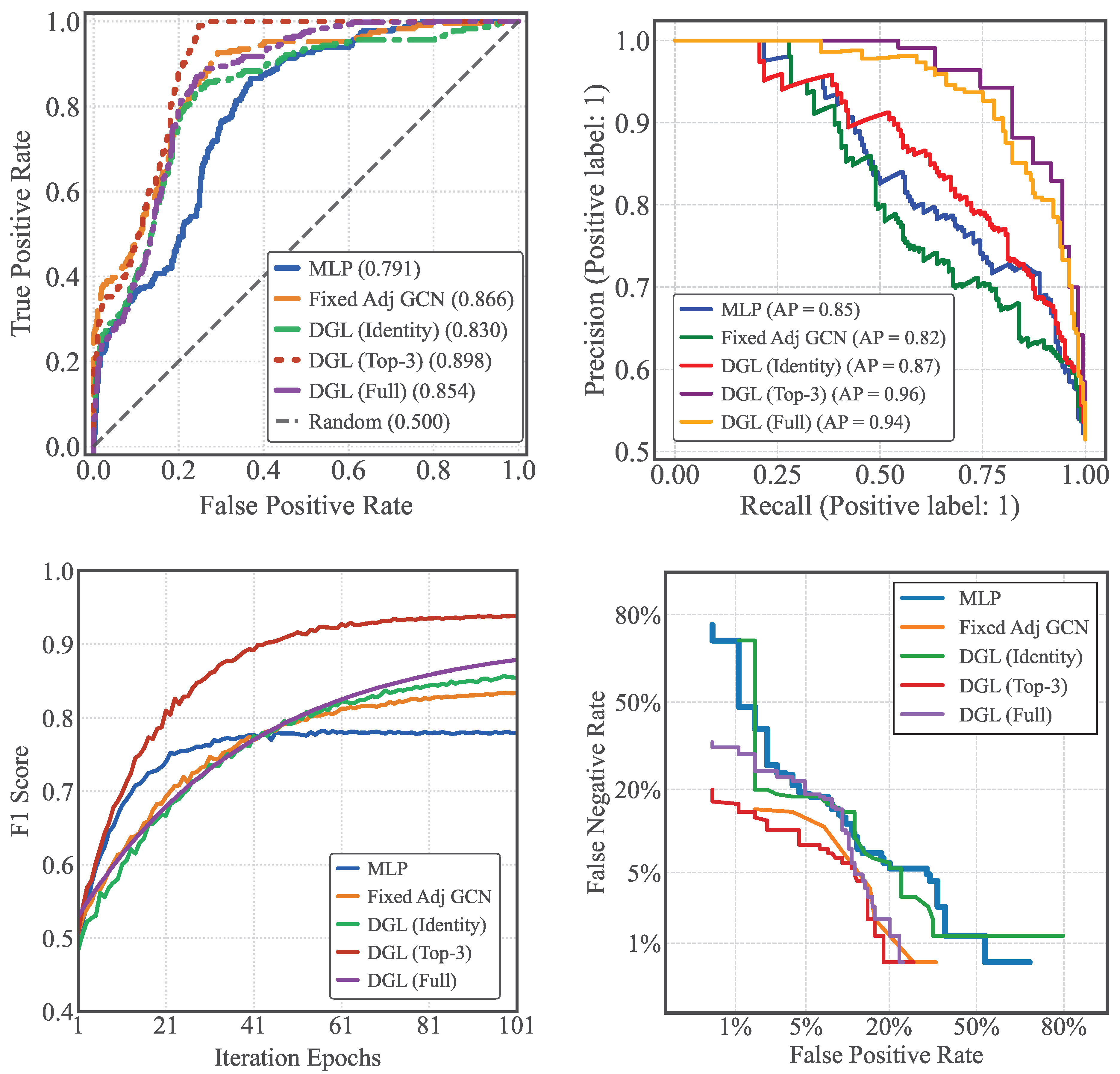

We propose a novel GC-ViT framework for G-LOC detection through AU analysis. The model incorporates motivated graph structures where nodes represent key AUs and edges capture their dynamic interactions during G-LOC. Evaluated on centrifuge training data, the framework achieves strong performance with an AUC-ROC of 0.898 and an AP of 0.96.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section II reviews related work on AU detection and the application of GCNs in AU recognition. Section III introduces the proposed GC-ViT architecture, designed for accurate recognition of G-LOC related facial movements. Section IV validates the effectiveness of the proposed system through ablation studies and generalization experiments. Finally, Section V summarizes the overall work and provides a comprehensive conclusion regarding the model’s performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Architecture Overview

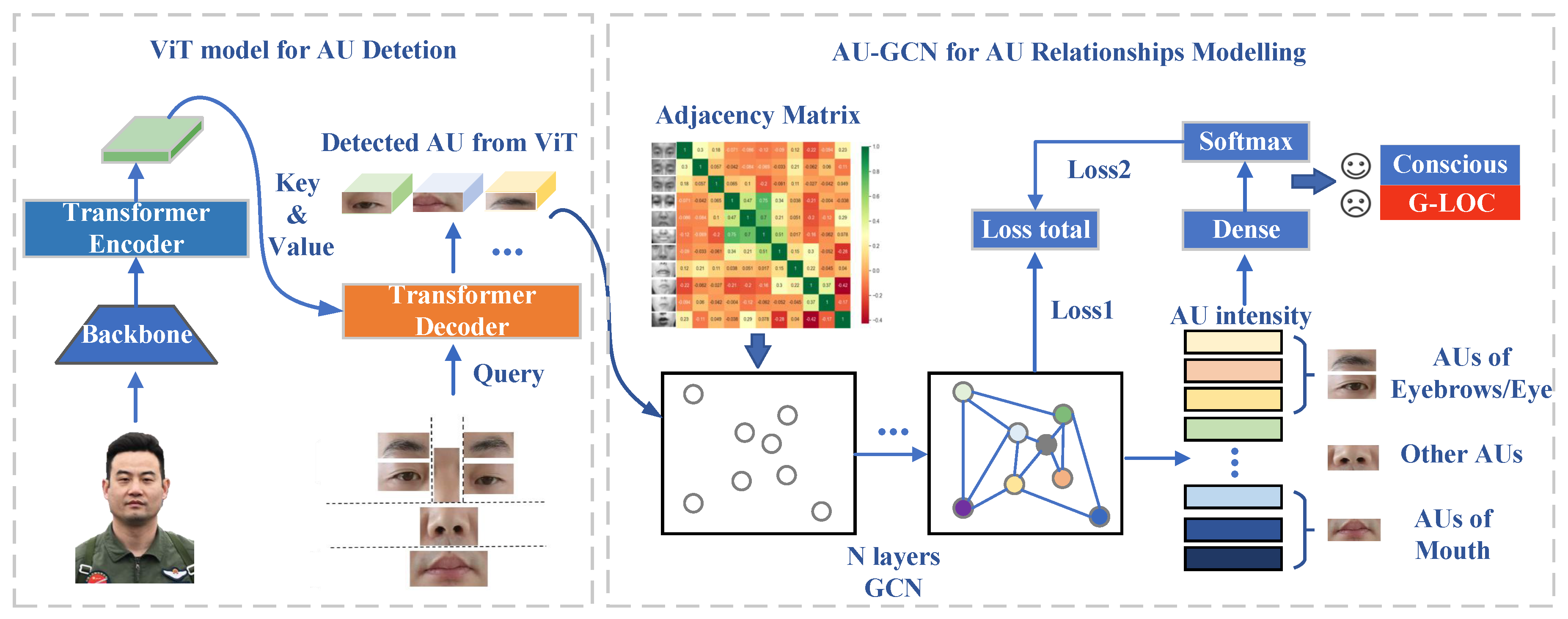

This study presents an enhanced Transformer-based architecture for AU detection, designed to capture subtle facial expressions in HPHC training scenarios. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the proposed GC-ViT architecture adopts an encoder-decoder framework with multi-stage feature extraction and semantic-guided attention mechanisms to achieve precise recognition of G-LOC-related facial movements.

To further exploit inter-dependencies among AUs, we incorporate GCN-based relationship modeling within the GC-ViT framework. The GCN module utilizes the initially detected AU probabilities as node features, while incorporating established AU correlations as prior knowledge for graph construction. Through stacked graph convolution operations performed on this relational graph, the model produces updated feature representations that reflect learned AU interdependencies. These enhanced features are subsequently utilized for the final classification task of determining pilot consciousness states.

As shown in the GC-ViT Architecture, the proposed system systematically integrates visual feature extraction, semantic-visual interaction, and structured AU relationship modeling to enhance the detection of G-LOC in HPHC training scenarios. The refined AU representations, enriched by graph-based dependency learning, serve as discriminative features for assessing the pilot’s G-LOC state. By capturing subtle facial movements and their interdependencies, our GC-ViT Architecture provides a robust framework for real-time consciousness monitoring under high-G conditions.

3.2. ViT for AU Detetion

The encoder module employs a ResNet-50 backbone network to extract hierarchical visual features from the input image . Through five convolutional blocks, the network generates a feature map with spatial dimensions and , where denotes the channel depth. To adapt these features for Transformer-based processing, a convolutional layer reduces the channel dimension to , yielding . The spatial features are then flattened into a sequence representation , where corresponds to the number of spatial positions.

For positional encoding, we implement learnable 2D position embeddings that preserve spatial structure while avoiding potential inductive biases associated with traditional sinusoidal encoding:

where

contains learnable positional parameters. This approach maintains critical spatial relationships between facial regions while allowing flexible adaptation to varying input resolutions.

The encoder’s primary function is to enhance visual features corresponding to key facial regions including eyelids, eyebrows, and perioral areas that exhibit characteristic muscle movement patterns during G-LOC episodes. Through hierarchical feature extraction and spatial encoding, the encoder captures both: Local muscle activation patterns. The encoded features thus contain rich, position-aware representations of facial dynamics essential for subsequent AU-specific decoding. The encoder architecture effectively transforms raw pixel data into a structured, high-level representation suitable for analyzing subtle neuromuscular changes characteristic of G-LOC progression. Subsequent cross-attention mechanisms in the decoder can then focus on clinically relevant spatial-temporal patterns within this optimized feature space.

The decoder module employs a set of C learnable AU query vectors denoted as

, where each query vector

encapsulates the semantic representation of a specific AU (e.g.,

encodes "AU01=inner brow raiser"). These query vectors interact with the encoded visual features

through a cross-attention mechanism, formally expressed as:

Here,

denotes the baseline ocular region embedding and

represents a learnable displacement vector. The model further employs multi-head attention (with 8 parallel attention heads) to capture heterogeneous feature subspace relationships, where each attention head computes:

This equation computes the h-th attention head’s output in a multi-head attention layer. Here, , , and are the query, key, and value matrices for head h, while d is the feature dimension and H is the number of attention heads. The scaled dot-product attention first measures similarity between queries and keys, then applies softmax to get attention weights, which are used to weight the values.

This section presents a Transformer-based framework for AUs feature extraction. The model employs learnable AU query vectors to enhance visual feature encoding through self-attention mechanisms in the encoder module. Subsequently, cross-attention operations are applied to extract AU-specific semantic representations from the encoded visual features. The incorporation of multi-head attention further enables the model to capture heterogeneous interactions across different feature subspaces, thereby strengthening its discriminative capacity for G-LOC-relevant micro-expression AUs.

3.3. GCN for AU Relationships Modelling

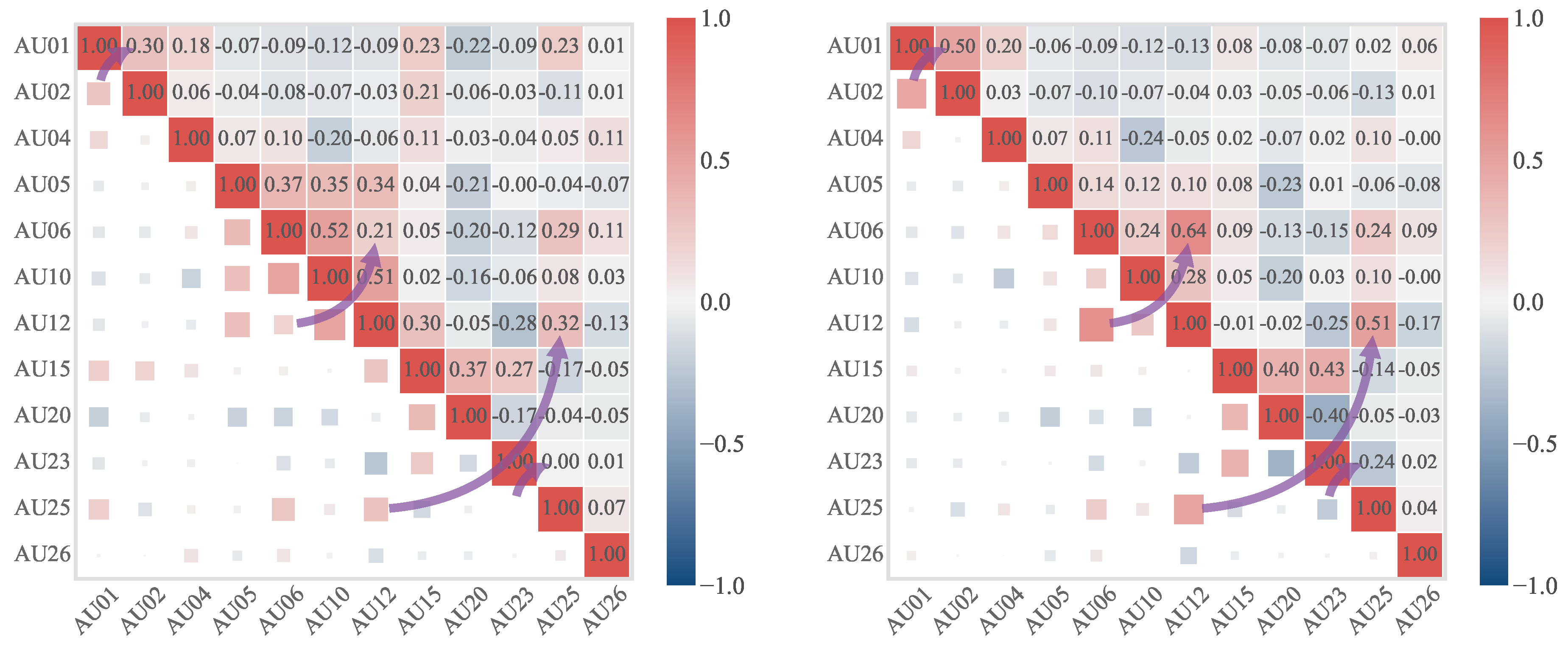

AUs are controlled by facial muscles and constrained by facial anatomy, resulting in inherent relationships between their intensities. During anti-G straining maneuvers under high-G conditions, pilots activate specific AUs. To assess training effectiveness, this study develops an intensity correlation model to capture the interactions between different AUs. Co-occurrence relationships arise when certain AUs are frequently activated together due to muscle interactions, such as cheek raising and lip corner pulling. Conversely, mutual exclusion relationships describe AUs that rarely co-occur, such as brow lowering and lip corner stretching in natural expressions. The structural dependencies among AUs influence not just their activation but also their intensity relationships. For instance, AU01 (inner brow raiser) and AU02 (outer brow raiser), both controlled by the muscle, typically activate together with correlated intensities. The Pearson correlation coefficient

is calculated as:

where

Y denotes facial action unit indices,

and

are the standard deviation and mean of sample

X, respectively. The Pearson correlation coefficient is derived from the covariance divided by the product of standard deviations.

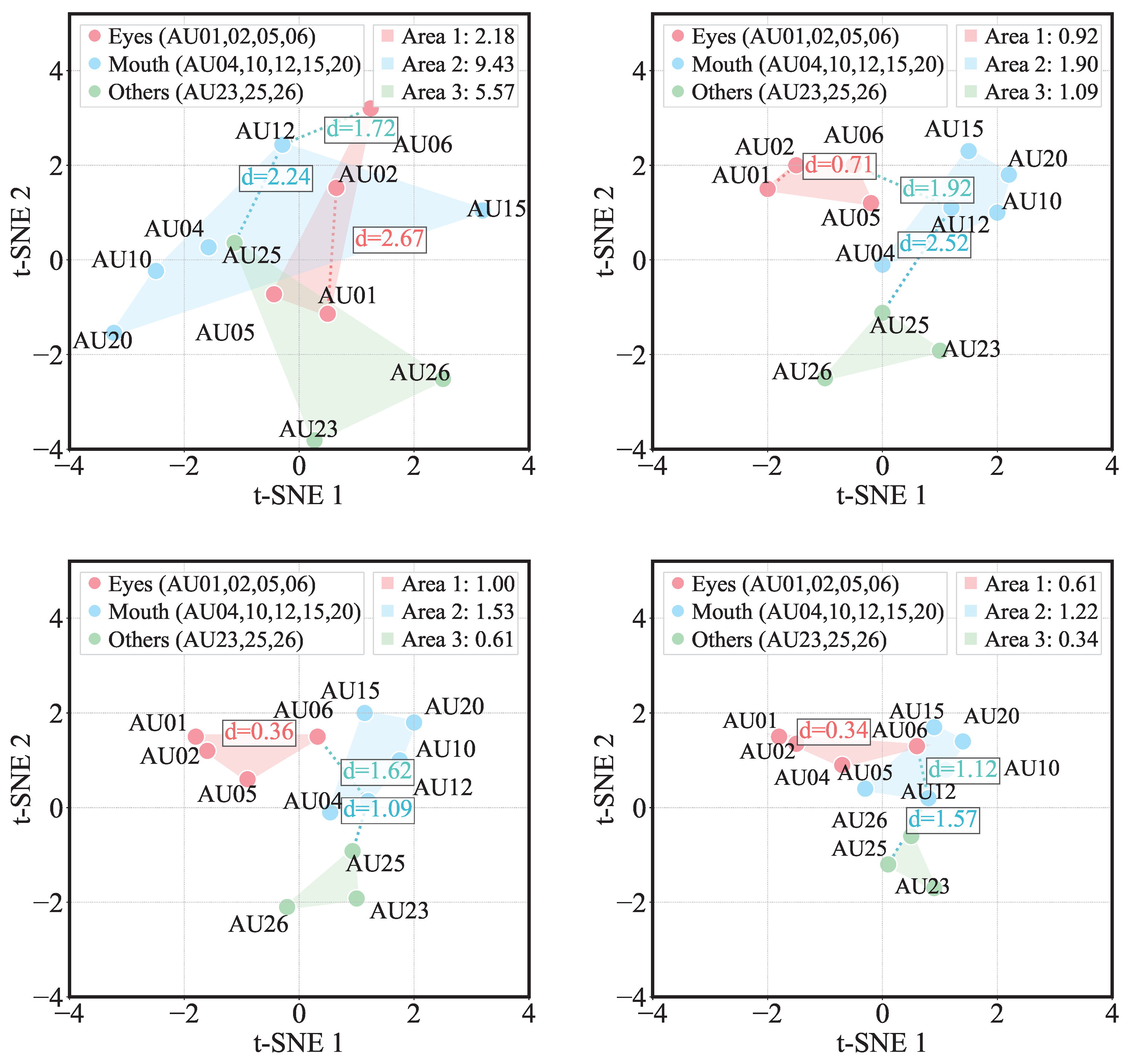

The coefficient ranges from -1 to 1. Values approaching 1 indicate strong co-activation relationships, while values near -1 suggest mutual exclusion. A coefficient of 0 implies no linear relationship between AU intensities. Based on centrifuge training video data of pilots performing anti-G straining maneuvers, we computed a heatmap of Pearson correlation coefficients to visualize these inter-AU relationships. This quantitative analysis enables objective evaluation of G-force respiratory training effectiveness through facial muscle activation patterns.

The inputs

,

, …,

are fed into the graph convolutional network of the facial action unit learning module. Through learning in the two-layer graph convolutional network, the outputs

,

, …,

are obtained. The formula for the graph convolutional network is as shown in:

Here, represents the output of the graph convolutional network, i.e., , , …, . represents the input of the graph convolutional network, i.e., , , …, . denotes the adjacency matrix, which is a dependency matrix derived from statistical analysis of facial action unit dependencies in the dataset. and are the parameters of the graph convolutional network, and Relu represents the activation function.

The 12×1 AU feature vector learned through graph convolutional networks is fed into a fully connected layer for feature transformation. This dense layer linearly maps the 12 dimensional AU feature space to a 2-dimensional space, corresponding to the binary classification task of determining whether a pilot experiences G-LOC. The output of the fully connected layer represents unnormalized class scores. These logits are then processed by a softmax layer for probability normalization. The softmax function applies exponential transformation and normalization to the logits, ensuring that the sum of the two output class probabilities strictly equals 1, thereby generating precise probabilistic estimates of G-LOC occurrence.

The GCN of the AU learning module further incorporates a dynamic graph modeling mechanism to adapt to the time-varying characteristics of AU interaction patterns during high-G training. Its core lies in designing dynamic update logic based on the phased features of the G-LOC training process—unlike update methods driven by video frame sampling frequency, this study treats 20 consecutively extracted AU-specific semantic representations (each containing 12-dimensional AU intensity features, anatomical weight features, and timestamp information) as a dynamic update unit. That is, the adjacency matrix weights are dynamically adjusted once per input batch of AU semantic sequences (corresponding to a continuous action phase in G-LOC training, such as the anti-G force maintenance phase or overload increment adaptation phase). This design not only aligns with the non-instantaneous characteristics of facial muscle responses under high-G overload (the evolution of muscle synergy patterns requires a certain time window to manifest) but also avoids noise accumulation caused by frame-by-frame updates, ensuring the model focuses on physiologically meaningful trends in AU association evolution.

The construction of the dynamic adjacency matrix integrates a hierarchical strategy of anatomical prior initialization, data-driven weight update, and adaptive sparsification filtering: First, constrained by facial muscle anatomical associations (e.g., frontalis muscle synergy for

-

, zygomaticus muscle linkage for

-

), an initial adjacency matrix

is constructed by combining the Pearson correlation coefficients of AU intensities in the training set. The element

is defined as the weighted fusion of the anatomical association weight

and statistical correlation coefficient

between

and

:

where

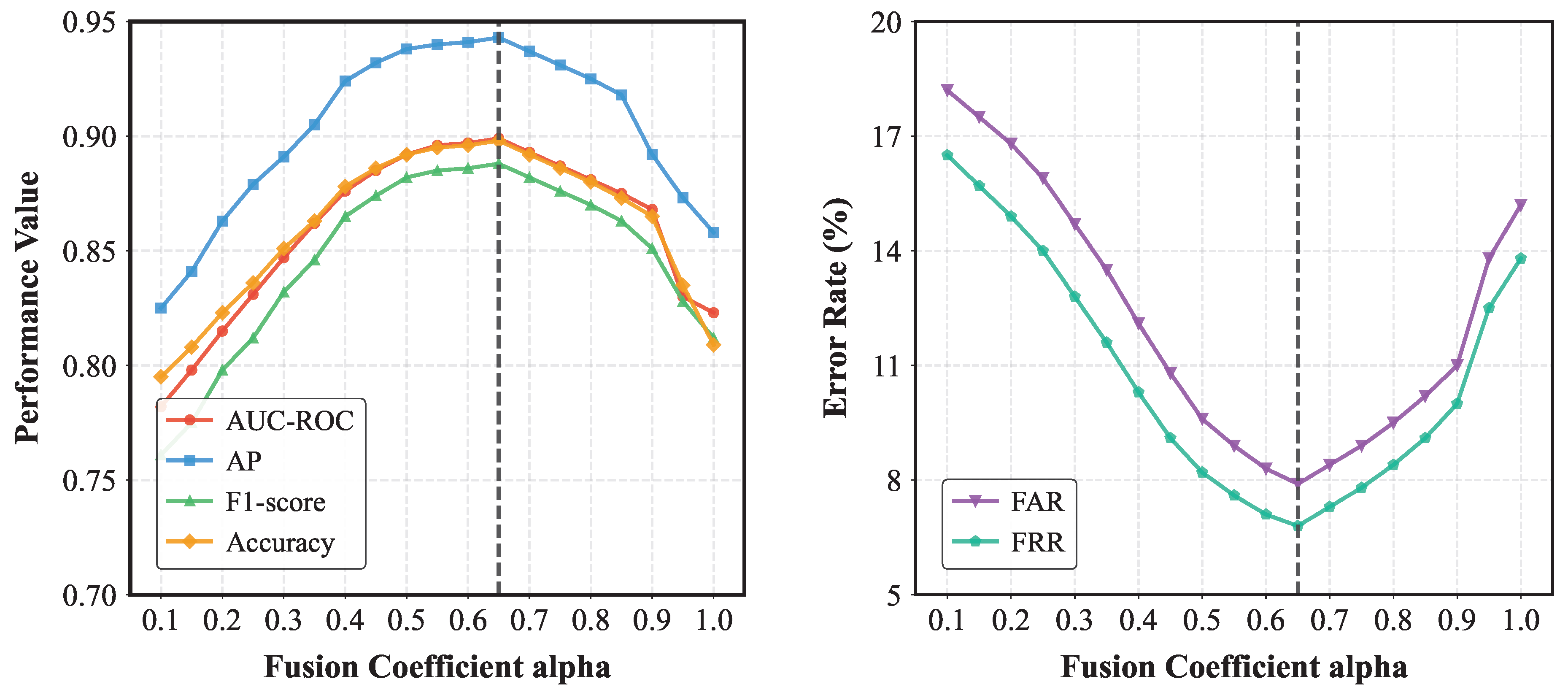

denotes the fusion coefficient (set to

via 5-fold cross-validation to balance anatomical priors and data statistical features). Subsequently, for each input batch of AU semantic representation sequences

, the dynamic association strength

between AUs within the current batch is calculated, which fuses cosine similarity in the feature space and mutual information in the time series to capture spatiotemporal correlations:

where

represents the cosine similarity of AU feature vectors, and

denotes the mutual information of the intensity sequences of

and

(

indicates the probability distribution). The adjacency matrix weights are then updated as follows:

where

is the Sigmoid function (utilized to normalize the association strength to the interval

). Finally, top-

K sparsification filtering is implemented not by predefining a fixed range for

K, but by adaptively determining

K based on the feature discriminability criterion of each AU node in the current batch

, where lower entropy indicates more focused node associations). Experimental validation across multiple groups demonstrates that when retaining the top-

K connections for each AU node by association strength, the node discriminability entropy reaches a minimum at

; thus,

is ultimately determined. The filtered adjacency matrix

satisfies:

where

denotes the set of the top three AU nodes with the strongest association to

. The calculation of dynamic graph convolution remains based on the original framework, but the adjacency matrix is replaced with the real-time updated sparsified matrix

:

This design enables the model to dynamically capture synergistic and antagonistic relationships between AUs throughout the G-LOC training process, avoiding the over-smoothing problem caused by fully connected graph structures while anchoring key physiological associations through the combination of anatomical priors and data-driven learning. This provides more discriminative feature representations for the subsequent G-LOC binary classification task.

3.4. Loss Function for The Model

The complete loss function consists of two components: AU detection loss and graph-based G-LOC state prediction loss. The first component measures the discrepancy between predicted AU intensities and ground truth labels using visual Transformer features:

where

represents the continuous ground-truth intensity of facial action units,

denotes the visual Transformer’s output features for the

i-th sample, and

is the sigmoid activation function.

The second component

represents the graph classification loss for G-LOC state prediction, computed using the predicted AU vectors as input features:

where

indicates the true G-LOC state (0 for non-G-LOC, 1 for G-LOC), and

is the predicted probability of G-LOC state derived from graph neural network processing of AU features.

The total loss combines both components with balancing coefficients:

where

controls the relative importance between AU detection and G-LOC state prediction tasks. This multi-task learning framework enables joint optimization of facial action unit recognition and G-LOC state classification through feature sharing between the visual Transformer and graph neural network.