1. Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a progressive autosomal recessive neuromuscular condition that affects the alpha motor neurons in the anterior horns of the spinal cord [

1]. It is caused by mutations or deletions in the SMN1 gene, leading to a deficiency in the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein [

1,

2]. Disease severity inversely correlates with SMN2 copy number [

1,

2]. SMA remains one of the most important genetic causes of infant mortality [

2,

3]. However, recent developments in the treatment and early diagnosis of SMA have led to a major shift in the survival of patients affected by SMA [

1,

2,

3]. SMA types 3 and 4 survive into adulthood, while SMA types 1 and 2 die in infancy and/or childhood [

2]. The incidence of SMA is estimated at 1 in 6,000-11,000 live births, worldwide [

3]. A Global Burden of Disease study showed that the first year of life had the highest SMA-related mortality, consistent with type 1 SMA [

4].

Three FDA-approved disease-modifying therapies have been studied in SMA to increase SMN protein levels [

5]. Along with newborn screening and early diagnosis, these treatments transformed SMA into a treatable condition [

5,

6]. Previous epidemiological study on mortality from SMA in the pre-treatment era showed excess all-cause mortality in people with SMA [

7]. However, the literature lacks epidemiological data on demographic disparities in SMA-related mortality in the United States (US). It is timely to evaluate these disparities in the post-treatment era. This study examined nationwide demographic disparities in SMA-related mortality based on biological sex, race/ethnicity, regions, and age groups from 2018 to 2023.

2. Materials and Methods

This study followed the RECORD reporting guidelines. This was a retrospective population-based study that utilized data extracted from the CDC WONDER database. We extracted data on SMA-related deaths in the US from 2018 to 2023 using the multiple-causes-of-death files. The data is derived from death certificates filed in state vital statistics offices [

8]. The denominator used for the mortality data is the entire US population and the Census Bureau estimates [

9]. To identify SMA, we used the following International Classification of Disease (ICD), 10th Revision, Clinical Modification codes, G12.0, G12.1, G12,8, and G12.9 [

10]. We obtained data regarding overall mortality, crude number of SMA-related deaths, crude mortality rate (CMR), and age-adjusted mortality rate (AAMR) per 1,000,000 population. The data were stratified by biological sex, race/ethnicity, US Census regions, and ten-year age groups. The AAMR controls for the variation in age distribution to allow data comparison; it was standardized using the 2000 US population. Race/ethnicity groups included Non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, Asian, and Hispanic. Age groups were divided into ten-year groups, but the following groups were analyzed separately: < 1 year, 1-4 years. Regions were divided into West, South, Northeast, and Midwest.

Analysis was conducted using mortality data of AAMR and CMR related to SMA, stratified by biological sex, race/ethnicity, regions, and age groups. For each group, we estimated rate ratios (RR) by dividing the rate in the group of interest by the rate in a pre-specified reference group. The following groups were considered reference: Hispanic, female, and Northeast. The CDC WONDER database provides 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each AAMR or CMR extracted, in addition to a standard error. This enabled obtaining 95% CI for each RR calculated. Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05. Age at death distribution was represented using grouped counts and visualized with a histogram-style bar chart. Figures, including bar charts and line plots of age-specific CMR with 95% CI, were generated using Python (pandas and matplotlib).

3. Results

3.1. Overall Mortality and Sex-Based Disparities

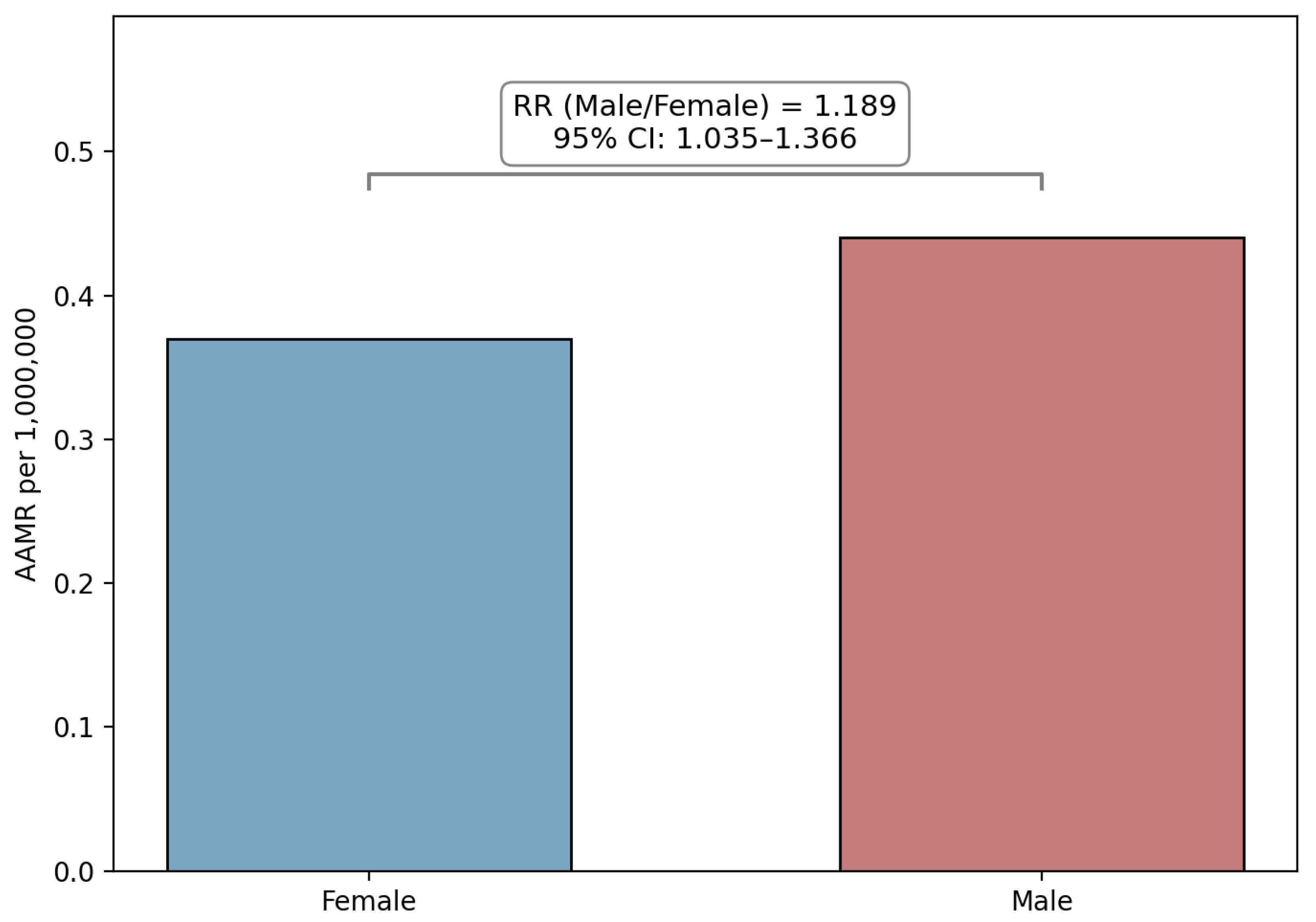

Over the study period, there was a total of 821 SMA-related deaths in the US. Out of these deaths, 376 (45.8%) involved female individuals. The AAMRs for males and females were 0.44 and 0.37, respectively. When comparing Male to Female AAMR, the RR was 1.189 (95% CI: 1.035 to 1.366, p = 0.014).

Figure 1 shows the results of the male versus female comparison.

Table 1 summarizes SMA-related deaths and AAMR data with stratifications.

3.2. Race/Ethnicity-Based Disparities

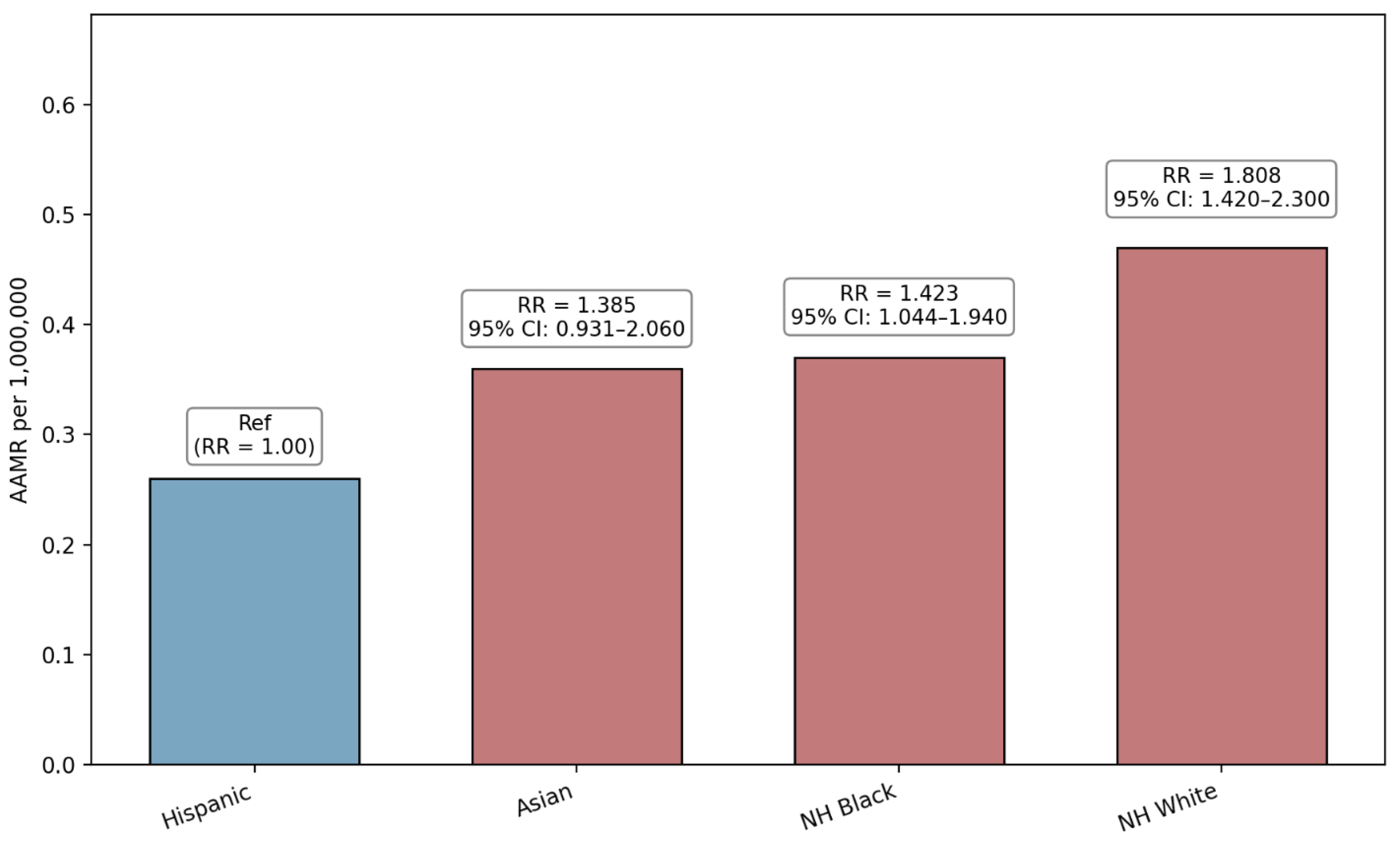

The majority of the SMA-related deaths involved NH White individuals (79.8%). Hispanic individuals were associated with the lowest AAMR and were used as a reference group for comparison. Compared to Hispanic individuals, the RR for NH White, NH Black and Asian individuals were 1.808 (95% CI: 1.420 to 2.300, p = 0.0000014), 1.423 (95% CI: 1.044 to 1.940, p = 0.026), and 1.385 (95% CI: 0.931 to 2.060, p = 0.108), respectively.

Figure 2 demonstrates the race/ethnicity comparison.

3.3. Region-Based Disparities

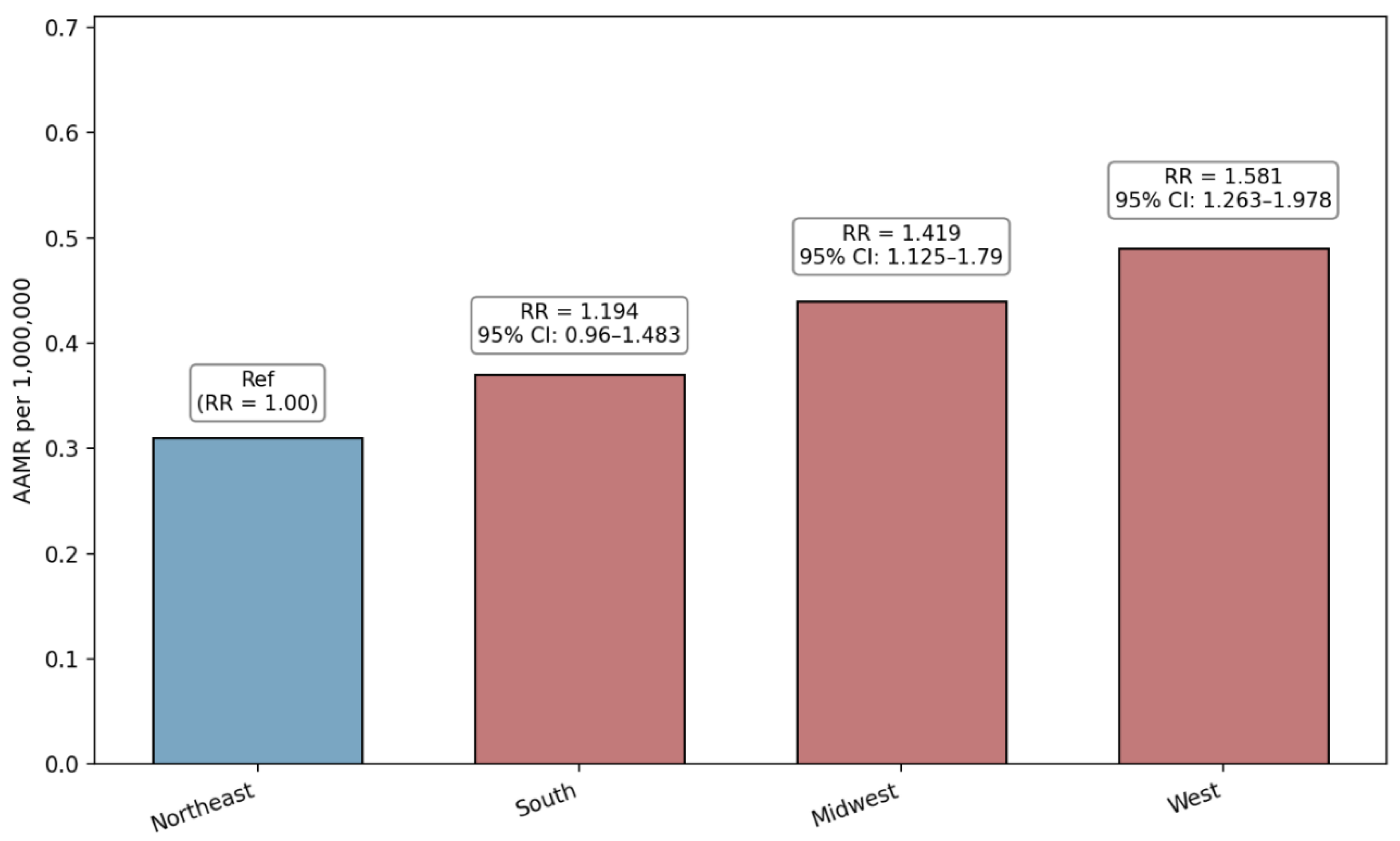

The South was associated with the highest number of crude SMA-related deaths (289, 35.2%). The lowest AAMR was noted in the Northeast (0.31 per 1,000,000 population). Therefore, using the Northeast as reference, the RR for the West (RR = 1.581, 95% CI: 1.263 to 1.978, p = 0.00000639) was the highest, followed by the Midwest (RR = 1.419, 95% CI: 1.125 to 1.790, p = 0.003094) and the South (RR = 1.194, 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.483, p = 0.11045).

Figure 3 shows the US Census region disparities in SMA-related mortality.

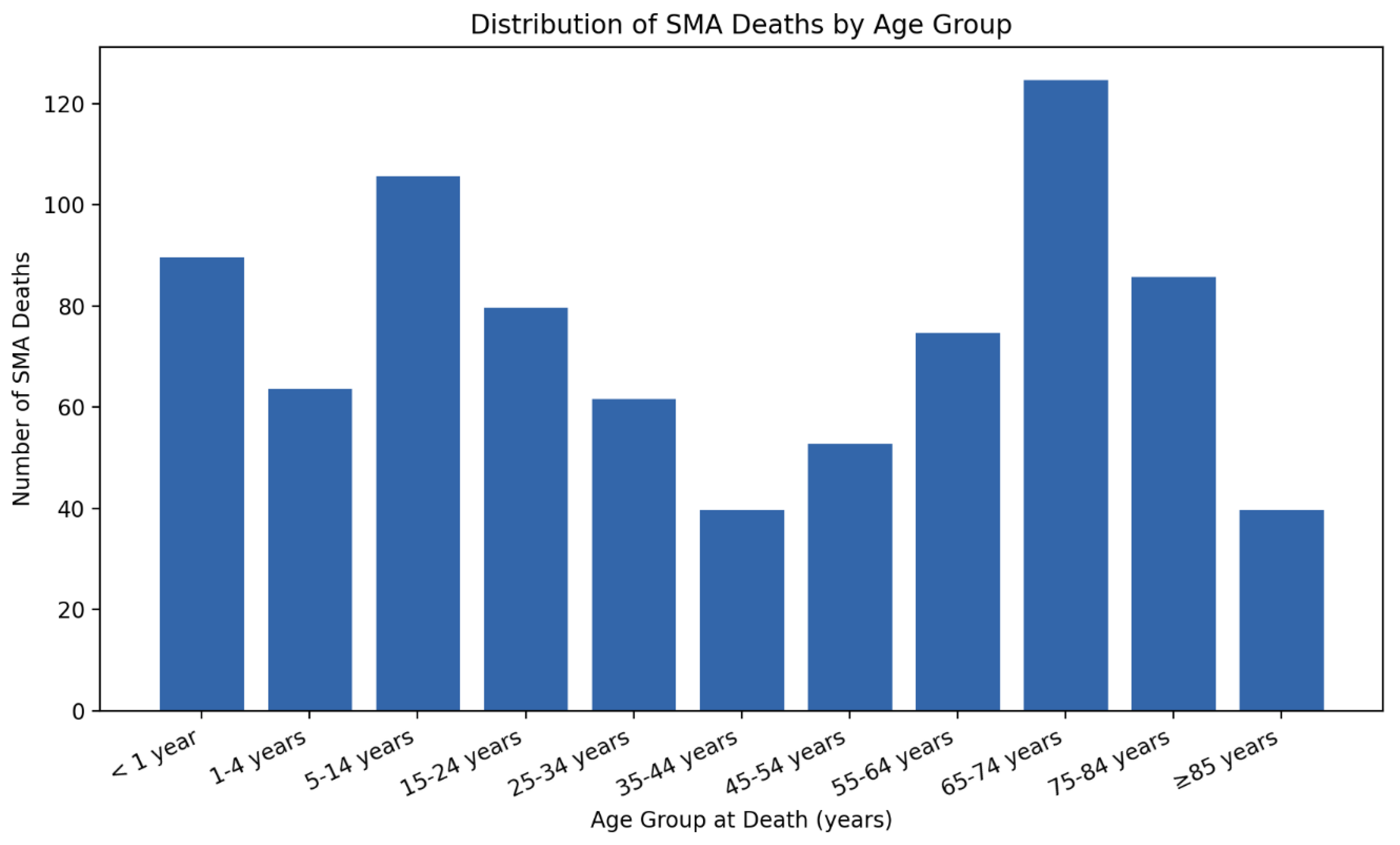

3.4. Age-Group Based Comparison

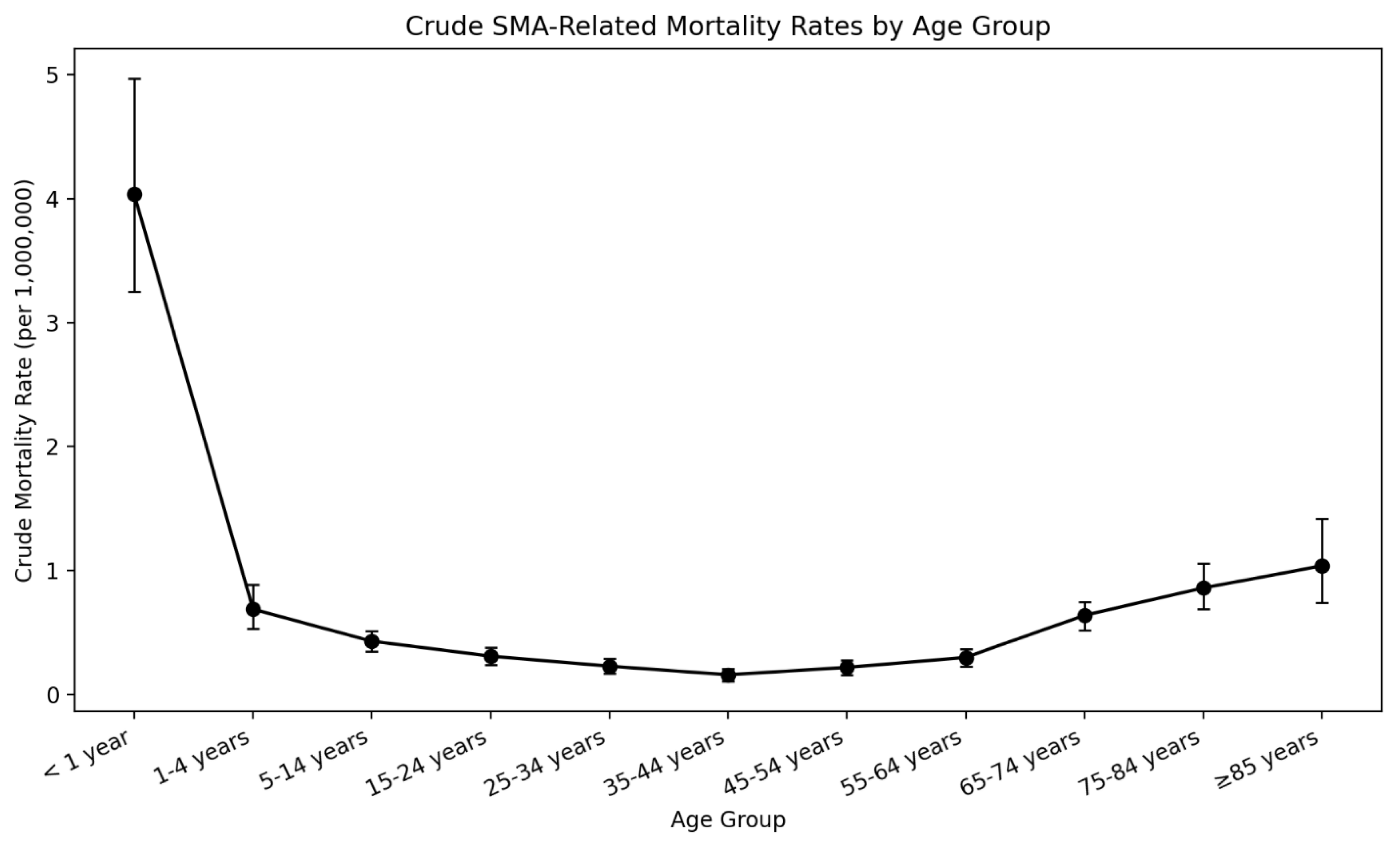

A large proportion of SMA-related deaths occurred in the following age groups: 5-14 years (12.9%) and 65-74 years (15.2%). There were 90 deaths in infants (<1 year of age) and this group was associated with the highest CMR among all age groups (4.04 per 1,000,000 population), as shown in

Figure 4. The distribution of age at death related to SMA showed an almost bimodal pattern as shown in

Figure 5.

Table 2 summarizes SMA-related deaths and CMR stratified by age groups.

4. Discussion

This study revealed several important findings regarding SMA-related mortality in the US. We uncovered significant demographic disparities in SMA-related mortality in the post-treatment era. Notably, SMA-related mortality was found to be higher in Male and NH White individuals, in the West, and in the infant age group. We also found a bimodal distribution in the age at death relating to SMA.

The literature is limited when it relates to sex-based differences in SMA prevalence and/or mortality. A Japanese study showed a larger number of male individuals in SMA type 3, while no difference was found in SMA type 1 or 2 [

11]. Older studies in 1995 showed that males were affected by mild SMA more than females [

12]. It is plausible that in the post-treatment era, male individuals with milder forms of SMA were less likely to be diagnosed early and receive disease-modifying treatment. This potential explains our findings of higher AAMR in males compared to females over the period 2018-2023. As a reinforcing example, an insurance claims study between 2008 and 2015 showed that adult patients with male infertility were diagnosed with mild SMA later in life [

13]. Future studies with granular-level patient data may establish sex-based differences in SMA clinical phenotypes and severity that explain our findings.

Prevalence and carrier frequency studies showed higher rates of SMA in European and Asian populations compared to African and Hispanic populations [

14,

15,

16]. Our findings are consistent with these previous findings, as NH White individuals were associated with the highest AAMR in the race/ethnicity-based comparison. However, even though previous data show that NH Black individuals are among the groups with lower prevalence and carrier frequency of SMA, we found that their associated SMA-AAMR was still higher than Hispanic individuals. This finding may point to possible care access-based disparities between the different race/ethnicity SMA groups in the US. Data on the relation between race/ethnicity and severity/phenotype of SMA are lacking, but most of the available evidence suggests that the main determinants of severity are SMN2 copy number and supportive care access [

17,

18,

19]. Our findings underscore the importance of further investigating race/ethnicity differences in SMA phenotype, severity, and access to care and disease-modifying treatments.

Pertaining to regional-based differences in SMA, very limited data exist. Prevalence data showed no regional differences among the US states [

13]. However, there is substantial variation in the availability of SMA disease-modifying treatments across states, driven by Medicaid coverage policies. These variations in requirements for treatment eligibility are based on SMN2 copy number, ventilator status, and prescriber expertise [

20]. This difference may impact patient access to treatment and, therefore, explain the significant region-based disparities in SMA-related mortality in our study. Even in states, such as New York, where statewide implementation of newborn screening facilitated early diagnosis and treatment, barriers related to insurance delays and infrastructure limitations persisted [

21]. Additionally, the rollout of these newborn screening programs was uneven across the US region, which led to disparities in early detection and treatment [

22,

23]. These aforementioned factors have probably played a role in the regional disparities we uncovered in our study. Our findings may assist healthcare administrators and policymakers in efforts related to equitable access to SMA-specialized care and treatment.

Limitations of this study involved the reliance on ICD codes for identifying SMA, with potential misclassification bias. In addition, stratifying the data by the type of SMA was not possible given the nature of the ICD codes and the low overall counts in the study. Analyzing disparities in other racial and ethnic groups (NH Asian or Pacific Islander, NH American Indian or Alaska Native individuals, etc.) was limited because of suppressed data in each subgroup. The CDC suppresses the counts of fewer than 10 in CDC WONDER data to protect confidentiality, and death rates are marked unreliable for a count less than 20 per the CDC WONDER data use agreement.

5. Conclusions

This study represents the first population-based analysis of demographic disparities in SMA-related mortality in the post-treatment era in the US. The findings uncovered here may assist efforts in the equitable delivery and implementation of SMA-specialized care and treatment and newborn screening programs. Policymakers and healthcare administrators may also find this data beneficial in improving regional disparities in SMA-related mortality. Future studies may focus on granular-level data and identifying difference in SMA phenotypes based on biological sex and race/ethnicity and on the underlying/contributing causes of death in SMA in the post-treatment era.

Authors Contributions: AA: Data curation, conceptualization, writing, analysis; RH: Writing and reviewing, conceptualization.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data compiled in this manuscript are publicly available upon request from the CDC WONDER database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mercuri, E.; Pera, M.C.; Scoto, M.; Finkel, R.; Muntoni, F. Spinal muscular atrophy — insights and challenges in the treatment era. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angilletta, I.; Ferrante, R.; Giansante, R.; Lombardi, L.; Babore, A.; Dell’elice, A.; Alessandrelli, E.; Notarangelo, S.; Ranaudo, M.; Palmarini, C.; et al. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: An Evolving Scenario through New Perspectives in Diagnosis and Advances in Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, C.; Jones, C.; Farwell, W.; Reyna, S.P.; Cook, S.F.; Flanders, W.D. Indirect estimation of the prevalence of spinal muscular atrophy Type I, II, and III in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, regional, and national burden of motor neuron diseases 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1083–1097. [CrossRef]

- Nishio, H.; Niba, E.T.E.; Saito, T.; Okamoto, K.; Takeshima, Y.; Awano, H. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Past, Present, and Future of Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; He, Z.-Y. An Overview of the Therapeutic Strategies for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viscidi, E.; Juneja, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Li, L.; Farwell, W.; Bhan, I.; Makepeace, C.; Laird, K.; Kupelian, V.; et al. Comparative All-Cause Mortality Among a Large Population of Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Versus Matched Controls. Neurol. Ther. 11, 449–457. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochanek, K.D.; Murphy, S.L.; Xu, J.; Arias, E. Deaths: Final Data for 2020. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023, 72, 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Cisewski, J.A.; Xu, J.; Anderson, R.N. Provisional Mortality Data — United States, 2022. Mmwr-Morbidity Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ar Rochmah, M; Shima, A; Harahap, NIF; et al. Gender Effects on the Clinical Phenotype in Japanese Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Kobe J Med Sci. Published. 2017, 63, E41–E44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zerres, K.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S. Natural History in Proximal Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Clinical analysis of 445 patients and suggestions for a modification of existing classifications. Arch. Neurol. 1995, 52, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipnick, S.L.; Agniel, D.M.; Aggarwal, R.; Makhortova, N.R.; Finlayson, S.G.; Brocato, A.; Palmer, N.; Darras, B.T.; Kohane, I.; Rubin, L.L. Systemic nature of spinal muscular atrophy revealed by studying insurance claims. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0213680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, B.C.; Donohoe, C.; Akmaev, V.R.; A Sugarman, E.; Labrousse, P.; Boguslavskiy, L.; Flynn, K.; Rohlfs, E.M.; Walker, A.; Allitto, B. Differences in SMN1 allele frequencies among ethnic groups within North America. J. Med Genet. 2009, 46, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Sugarman, E.; Nagan, N.; Zhu, H.; Akmaev, V.R.; Zhou, Z.; Rohlfs, E.M.; Flynn, K.; Hendrickson, B.C.; Scholl, T.; Sirko-Osadsa, D.A.; et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, W.K.; Hamilton, D.; Kuhle, S. SMA carrier testing: a meta-analysis of differences in test performance by ethnic group. Prenat. Diagn 2014, 34, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahungu, A.C.; Monnakgotla, N.; Nel, M.; Heckmann, J.M. A review of the genetic spectrum of hereditary spastic paraplegias, inherited neuropathies and spinal muscular atrophies in Africans. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaart, I.E.C.; Robertson, A.; Wilson, I.J.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; Cameron, S.; Jones, C.C.; Cook, S.F.; Lochmüller, H. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q–linked spinal muscular atrophy – a literature review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.J.; Puffenberger, E.G.; E Bowser, L.; Brigatti, K.W.; Young, M.; Korulczyk, D.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Loeven, K.K.; A Strauss, K. Spinal muscular atrophy within Amish and Mennonite populations: Ancestral haplotypes and natural history. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0202104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballreich, J.; Ezebilo, I.; Khalifa, B.A.; Choe, J.; Anderson, G. Coverage of genetic therapies for spinal muscular atrophy across fee-for-service Medicaid programs. J. Manag. Care Spéc. Pharm. 2022, 28, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Deng, S.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Kay, D.M.; Irumudomon, O.; Laureta, E.; Delfiner, L.; Treidler, S.O.; Anziska, Y.; Sakonju, A.; et al. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in New York State. Neurology 2022, 99, e1527–e1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Griggs, R.; Byrne, B.; Connolly, A.M.; Finkel, R.; Grajkowska, L.; Haidet-Phillips, A.; Hagerty, L.; Ostrander, R.; Orlando, L.; et al. Maximizing the Benefit of Life-Saving Treatments for Pompe Disease, Spinal Muscular Atrophy, and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Through Newborn Screening: Essential Steps. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Astudillo, C.; Byrne, B.J.; Salloum, R.G. Addressing the implementation gap in advanced therapeutics for spinal muscular atrophy in the era of newborn screening programs. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1064194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).