Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Grothendieck Inequality and Quantum Mechanics

2.2. The CHSH Bell Scenario

2.3. The Quantum De Finetti Theorem

3. Experimental Methods

3.1. Visibility Sweep Protocol

3.2. Hardware Specifications

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

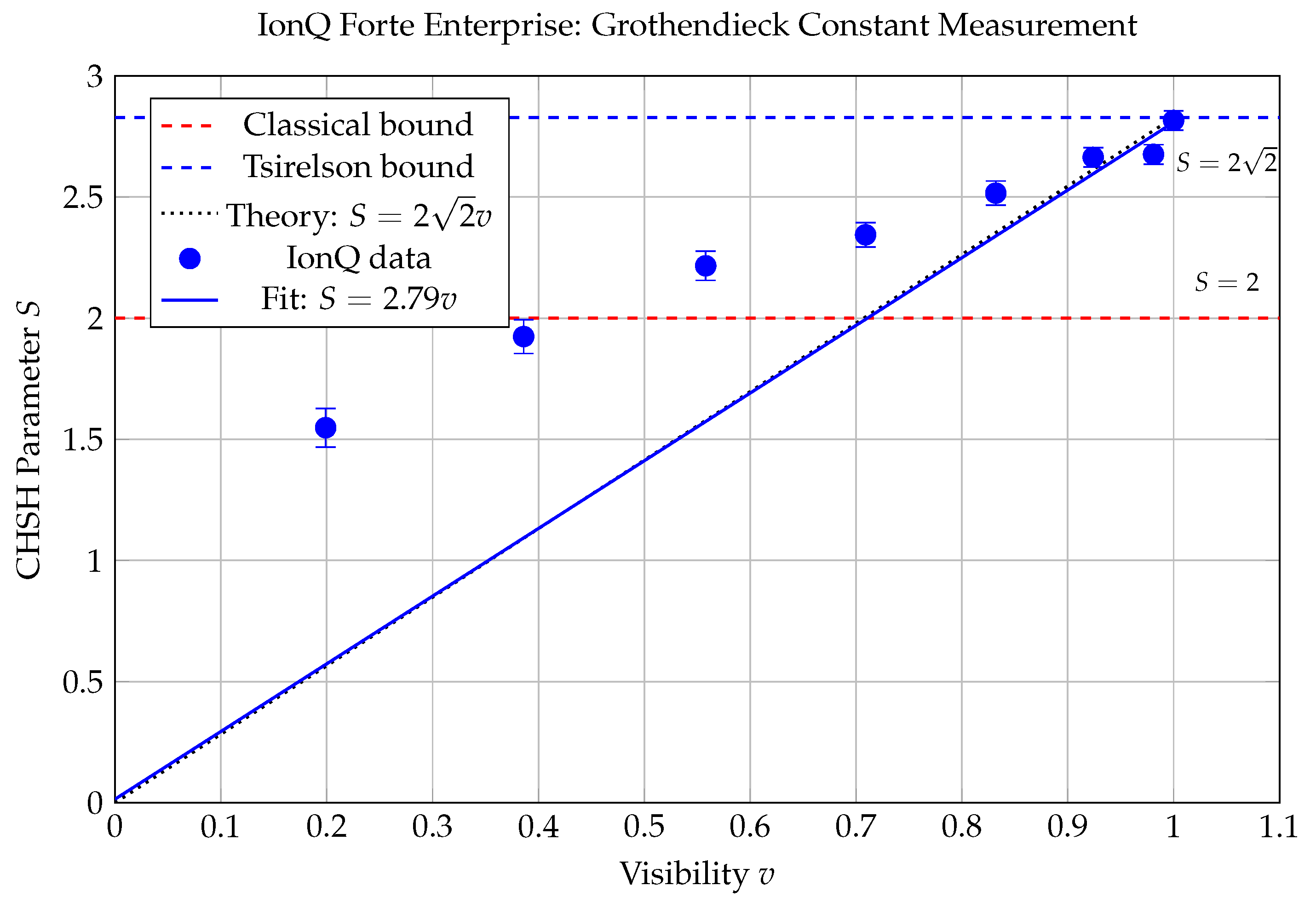

4.1. IonQ Forte Enterprise: Trapped-Ion Measurements

- Direct ratio (primary):

- Slope-based: Linear fit yields slope

4.2. IBM Torino: Superconducting Measurements

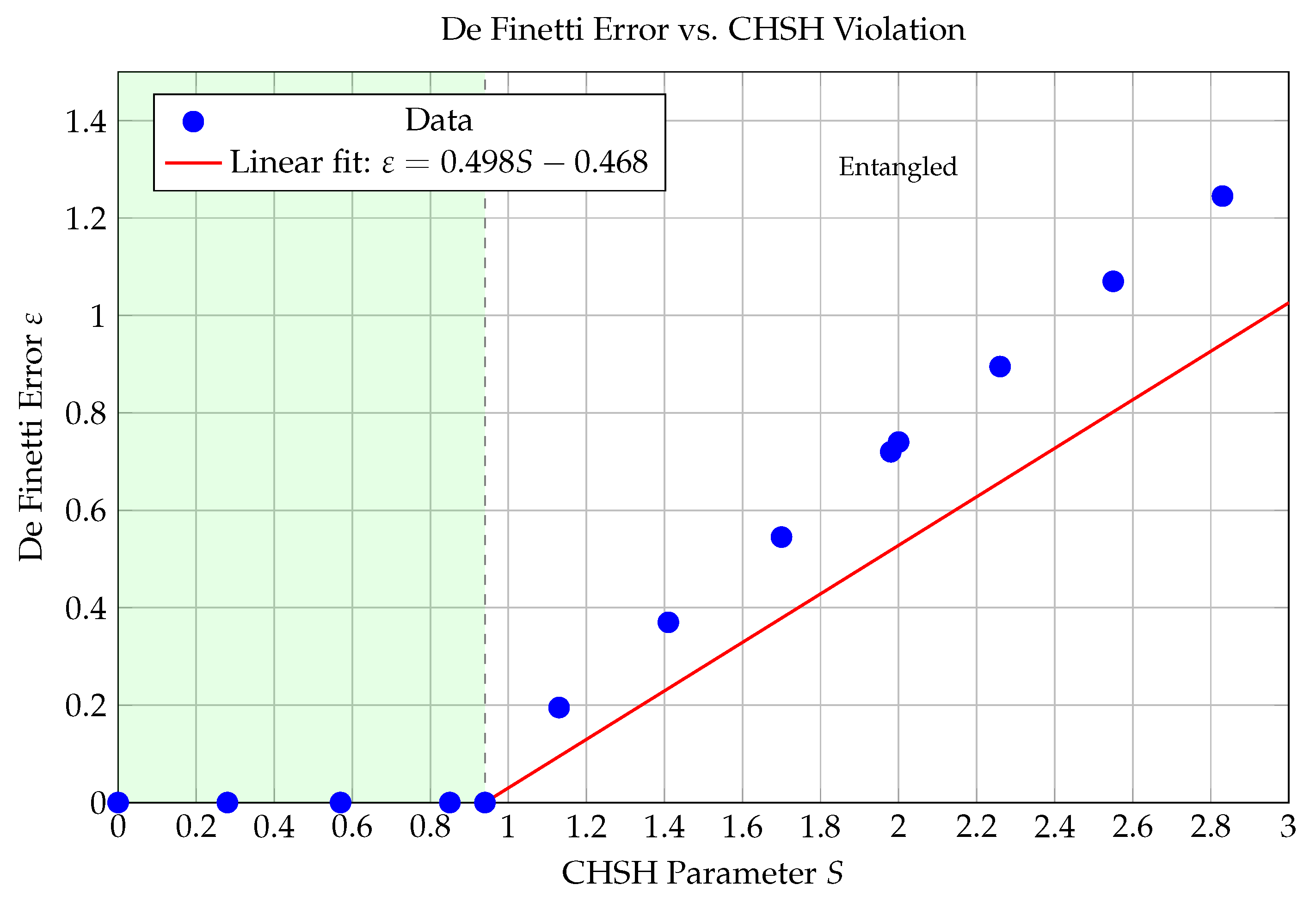

4.3. De Finetti Error Relationship

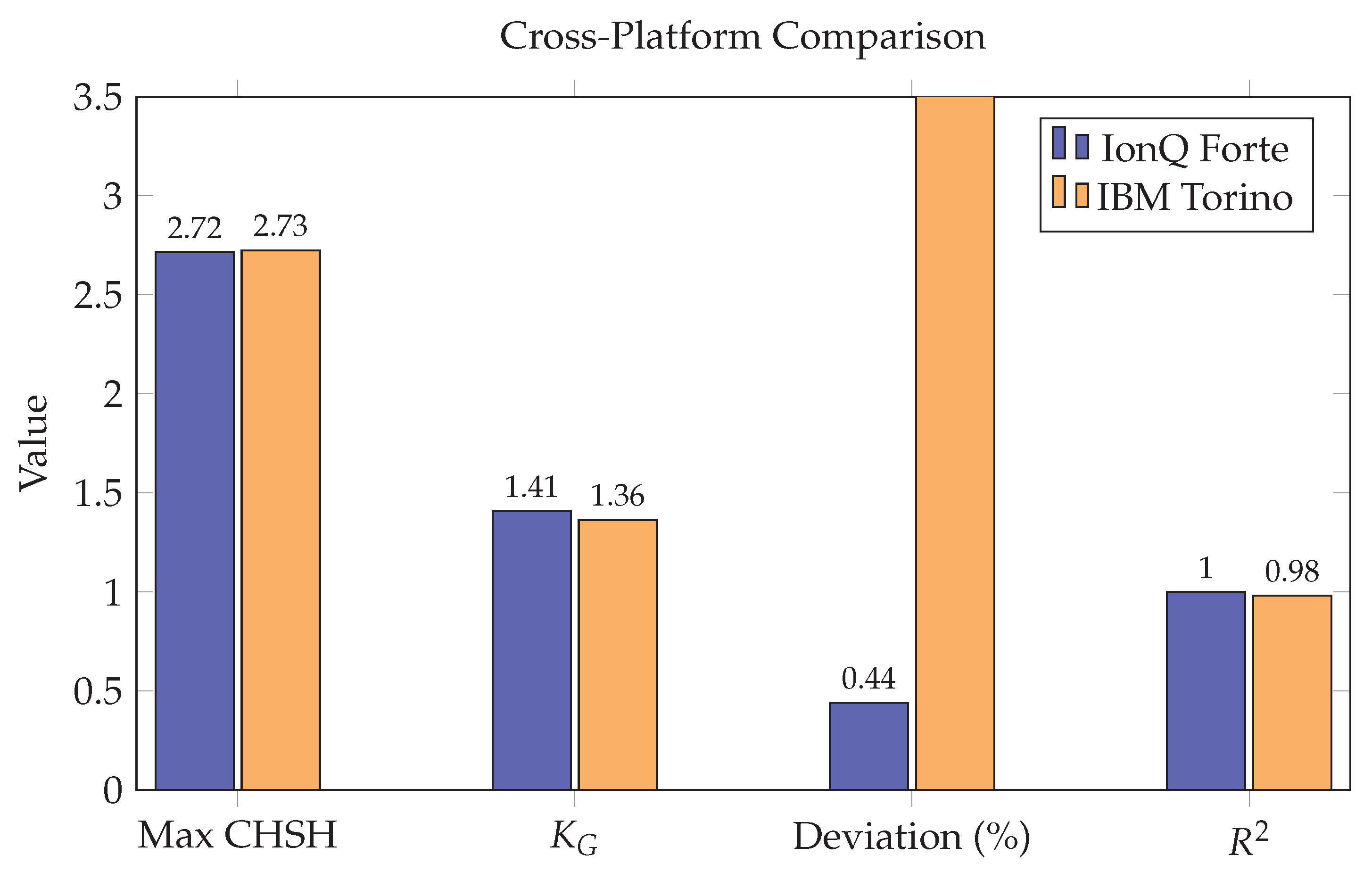

4.4. Cross-Platform Comparison

5. Discussion

5.1. Significance of Results

5.2. Technology Comparison

- Coherence: Trapped-ion s versus superconducting s represents four orders of magnitude difference, allowing trapped-ion systems to execute longer circuits without decoherence degradation.

- Gate fidelity: While nominal gate fidelities are comparable (>99%), the longer coherence times allow trapped-ion systems to maintain high fidelity over the full measurement sequence.

- Connectivity: All-to-all connectivity in trapped ions eliminates SWAP overhead present in fixed-topology superconducting systems.

- Measurement: Trapped-ion readout fidelity (>99.5%) exceeds superconducting (∼99%), reducing measurement-induced errors.

5.3. Implications for Quantum Information

- QKD Security: Device-independent QKD security proofs depend on the gap between achieved and maximum Bell violation. Our confirmation that hardware can approach within 0.44% of the theoretical maximum validates the practical applicability of these proofs.

- Quantum Advantage: The Grothendieck constant bounds the advantage of quantum over classical strategies in certain nonlocal games. Experimental confirmation supports theoretical claims about quantum computational advantage.

- Metrology: The Grothendieck constant joins other fundamental constants (speed of light, Planck constant, etc.) that have been measured with increasing precision. Further improvements may eventually rival the precision achieved for other constants.

6. Conclusion

7. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

AI Assistance Disclosure

Data Availability and Reproducibility

References

- Grothendieck, A. Résumé de la théorie métrique des produits tensoriels topologiques. Bol. Soc. Mat. São Paulo 1953, 8, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Krivine, J.-L. Constantes de Grothendieck et fonctions de type positif sur les sphères. Adv. Math. 1979, 31, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, M.; Makarychev, K.; Makarychev, Y.; Naor, A. The Grothendieck constant is strictly smaller than Krivine’s bound. Forum Math. Pi 2013, 1, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirelson, B. S. Quantum generalizations of Bell’s inequality. Lett. Math. Phys. 1980, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirelson, B. S. Quantum analogues of the Bell inequalities. J. Soviet Math. 1987, 36, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, J. F.; Horne, M. A.; Shimony, A.; Holt, R. A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1969, 23, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1991, 67, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarani, V.; et al. The security of practical quantum key distribution. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 1301–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lo, H.-K.; Pan, J.-W. Secure quantum key distribution with realistic devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2020, 92, 025002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, N.; Cavalcanti, D.; Pironio, S.; Scarani, V.; Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2014, 86, 419–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironio, S.; et al. Random numbers certified by Bell’s theorem. Nature 2010, 464, 1021–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspect, A.; Dalibard, J.; Roger, G. Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 1804–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, B.; et al. Loophole-free Bell inequality violation using electron spins. Nature 2015, 526, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustina, M.; et al. Significant-loophole-free test of Bell’s theorem with entangled photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 250401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalm, L. K.; et al. Strong loophole-free test of local realism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 250402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Finetti, B. La prévision: ses lois logiques, ses sources subjectives. Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré 1937, 7, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. L.; Moody, G. R. Locally normal symmetric states and an analogue of de Finetti’s theorem. Z. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie 1976, 33, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, C. M.; Fuchs, C. A.; Schack, R. Unknown quantum states: The quantum de Finetti representation. J. Math. Phys. 2002, 43, 4537–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christandl, M.; König, R.; Mitchison, G.; Renner, R. One-and-a-half quantum de Finetti theorems. Commun. Math. Phys. 2007, 273, 473–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R. Symmetry of large physical systems implies independence of subsystems. Nat. Phys. 2007, 3, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, F. G. S. L.; Christandl, M. Detection of multiparticle entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 160502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, C. A.; Schack, R. Quantum-Bayesian coherence. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013, 85, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, R. F. Quantum states with Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen correlations admitting a hidden-variable model. Phys. Rev. A 1989, 40, 4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A. Separability criterion for density matrices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodecki, M.; Horodecki, P.; Horodecki, R. Separability of mixed states. Phys. Lett. A 1996, 223, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alon, N.; Naor, A. Approximating the cut-norm via Grothendieck’s inequality. SIAM J. Comput. 2006, 35, 787–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeds, J. A. A new lower bound on the real Grothendieck constant. Unpublished manuscript (1991).

- Pérez-García, D.; Wolf, M. M.; Palazuelos, C.; Villanueva, I.; Junge, M. Unbounded violation of tripartite Bell inequalities. Commun. Math. Phys. 2008, 279, 455–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, D.; et al. Robust Bell inequality violations on IBM quantum systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.20241. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; et al. Multi-platform Bell inequality tests on cloud quantum computers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2506.08940. [Google Scholar]

- Taşar, D. E. & Öcal Taşar, C. TARA: Test-by-Adaptive-Ranks for quantum anomaly detection with conformal prediction guarantees. In preparation (2025).

- Taşar, D. E. Adversarial limits of quantum certification: When Eve defeats detection. In preparation (2025).

| 1 | A separate standalone CHSH test on the same hardware yielded , consistent within run-to-run variability typical of NISQ devices. |

| Run | Visibility | CHSH S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.199 | 0.388 | 0.392 | 0.380 | −0.388 | 1.548 |

| 2 | 0.386 | 0.476 | 0.484 | 0.480 | −0.484 | 1.924 |

| 3 | 0.558 | 0.552 | 0.556 | 0.556 | −0.552 | 2.216 |

| 4 | 0.709 | 0.584 | 0.588 | 0.588 | −0.584 | 2.344 |

| 5 | 0.832 | 0.628 | 0.632 | 0.628 | −0.628 | 2.516 |

| 6 | 0.924 | 0.664 | 0.668 | 0.668 | −0.664 | 2.664 |

| 7 | 0.981 | 0.668 | 0.672 | 0.668 | −0.668 | 2.676 |

| 8 | 1.000 | 0.704 | 0.680 | 0.676 | −0.756 | 2.816 |

| Metric | IBM Torino | IonQ Forte | Ratio/Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum CHSH S | 2.725 | 2.816 | 0.968 |

| Tsirelson ratio | 96.4% | 99.6% | 0.968 |

| Extracted | 0.968 | ||

| Deviation from | 3.6% | 0.44% | |

| Regression | 0.9812 | 0.9987 | 0.982 |

| Bell state fidelity | ∼0.90 | 0.984 | 0.915 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).