Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Imaginaries Regarding Climate Change

1.2. Approaches to Climate Change

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participating Actors and Research Techniques

2.2. Data Analysis Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

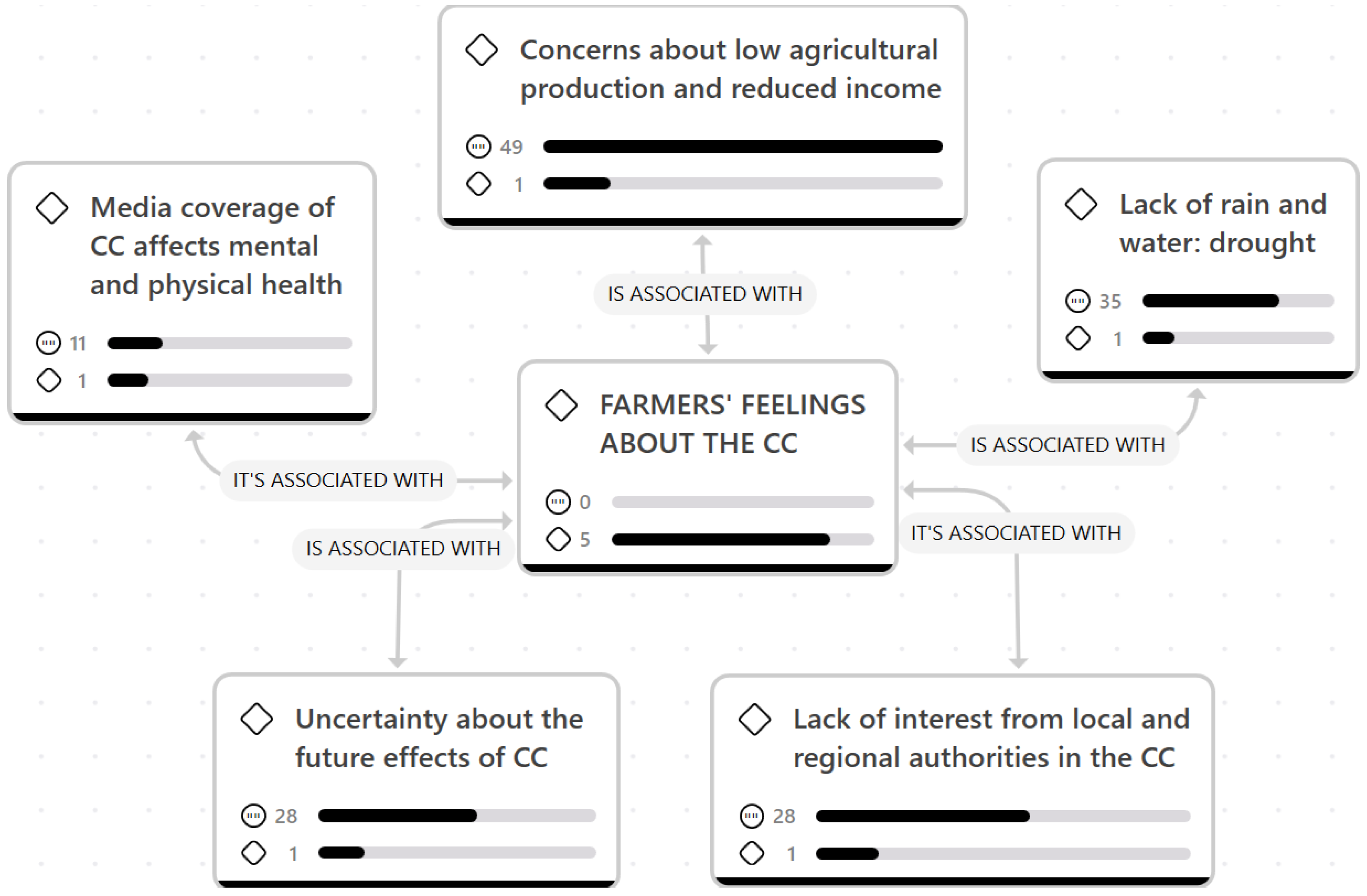

3.1. Feelings of Agricultural Producers Regarding Climate Change

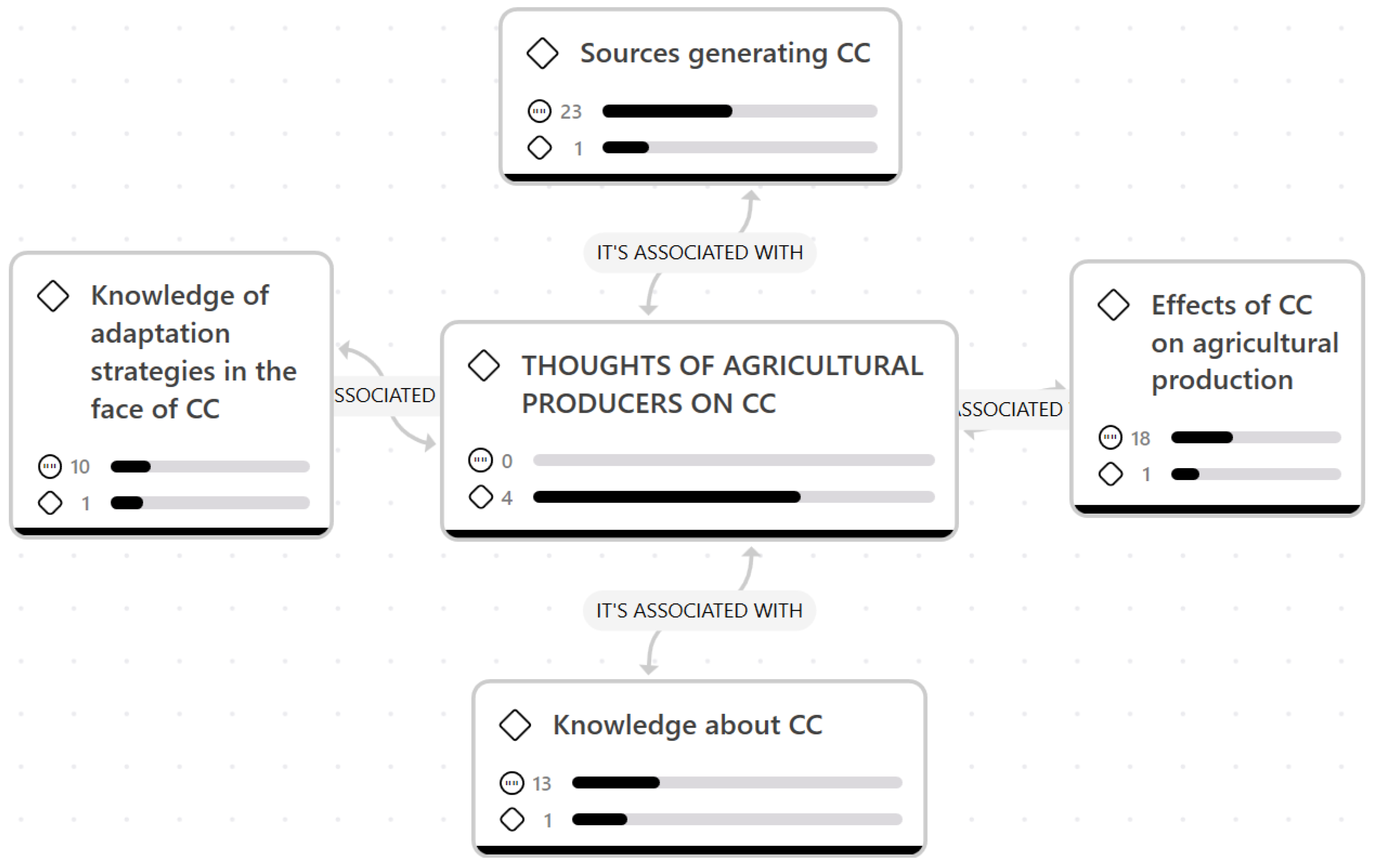

3.2. Agricultural Producers’ Thoughts on Climate Change

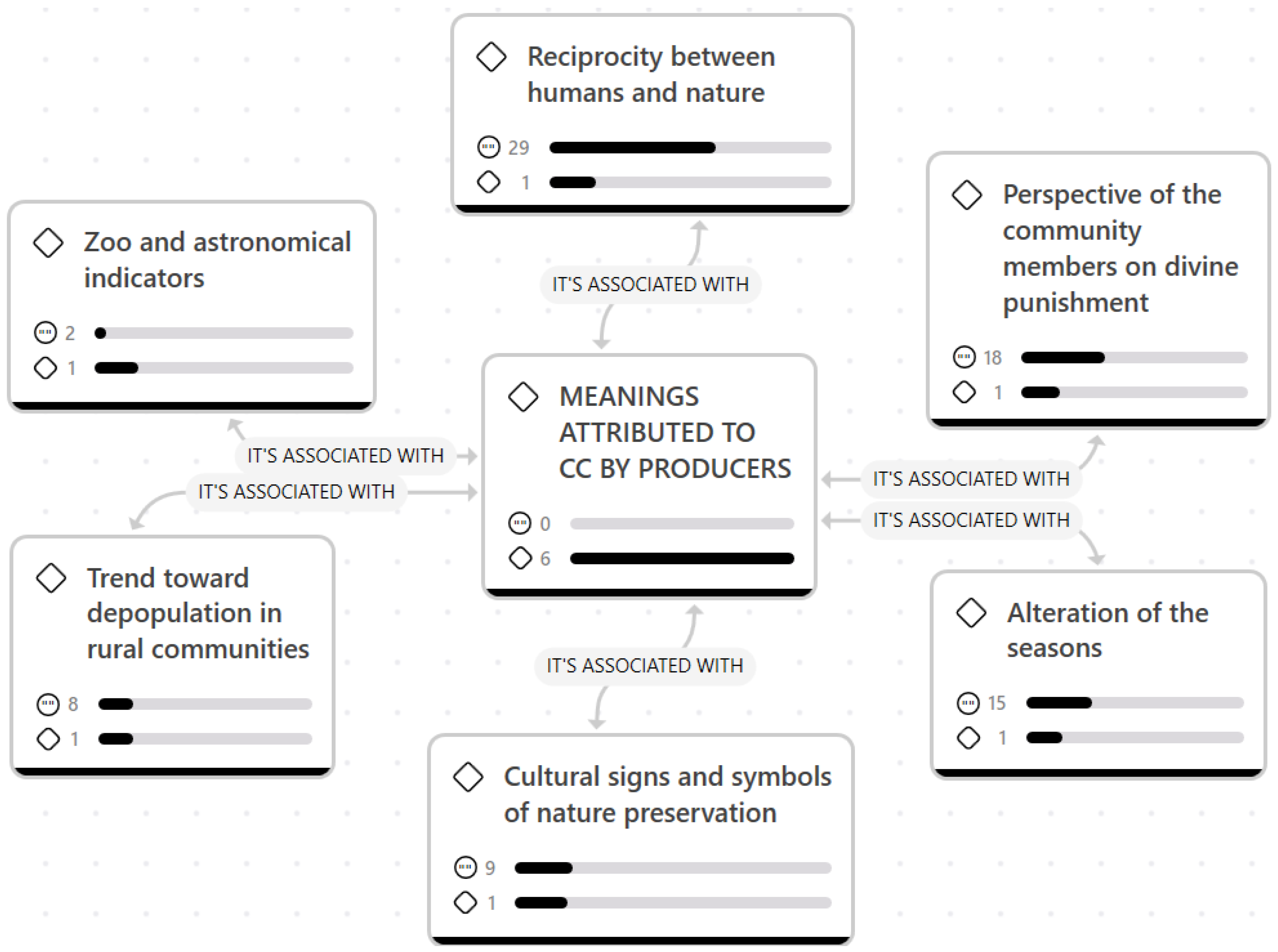

3.3. Social Meanings of Agricultural Producers Regarding Climate Change

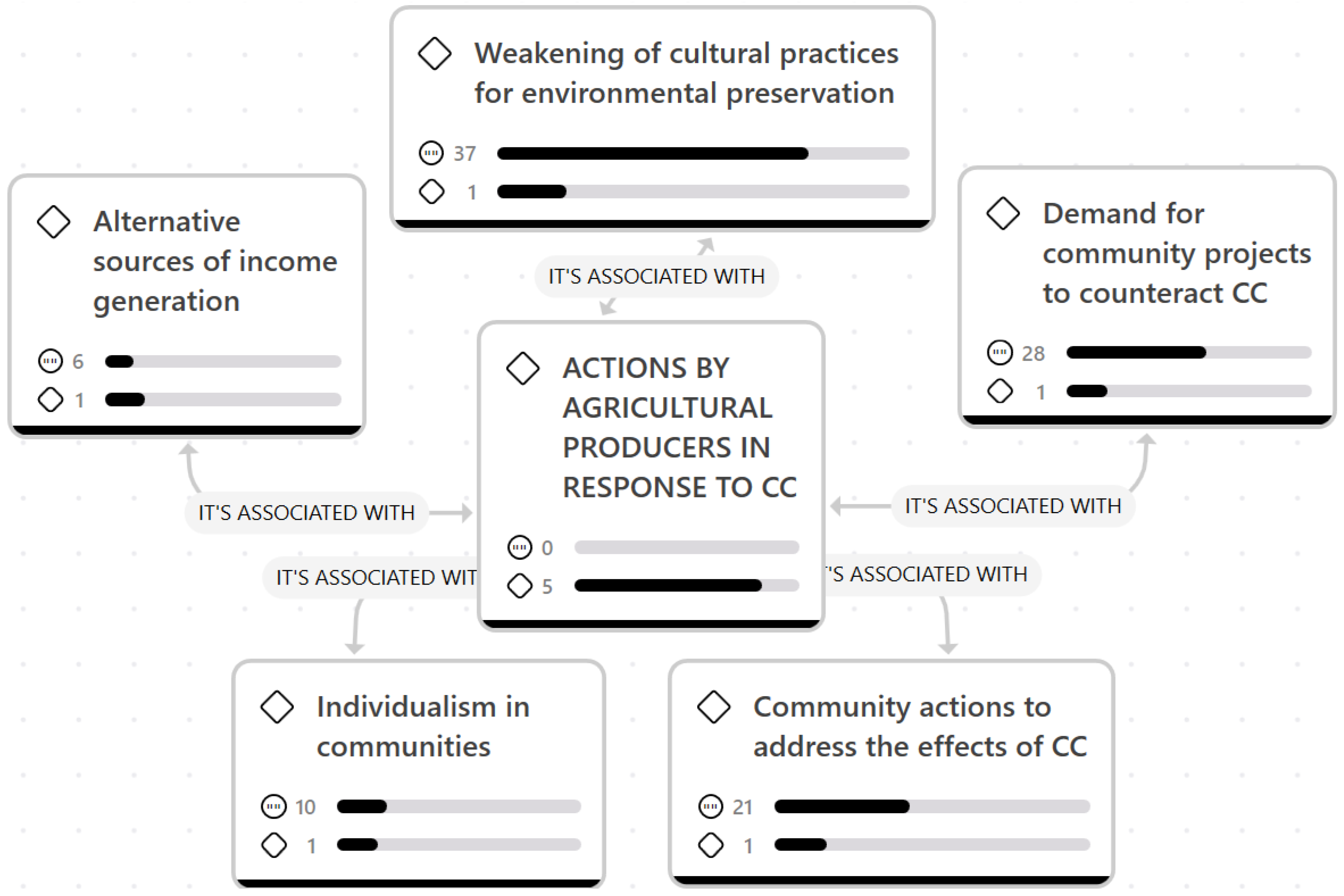

3.4. Adaptation Practices of Agricultural Producers to Climate Change

4. Final Reflections and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed consent statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belizario, G. Efectos del cambio climático en l agricultura de la cuenca Ramis, Puno, Perú Rev. Investig. Altoandinas 2015, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najarro, R.J. En tiempos de cambio climático: Relación agua–hombre en localidades altoandinas de Paras y Chuschi, Ayacucho. Alteritas. Rev. Estud. Sociocult. Andin. Amaz. 2020, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.; Reyes, O. Medidas de adaptación y mitigación frente al cambio climático en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidades, 2015. Available online: http://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/39781/S1501265_es.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 05 September 2025).

- INDECI. Déficit hídrico en el departamento de Puno.; Lima, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Castoriadis, C. La imaginación radical desde el punto de vista filosófico y psicoanalítico; Rivista Zona Erógena: Buenos Aires., 1993; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Castoriadis, C. La institución imaginaria de la sociedad, 1° Ed. ed; Buenos Aires, Arg., 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Imaginarios sociales modernos. In Barcelona: PAIDÓS; 2006; Volume 25, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Baczko, B. Los imaginarios sociales. Memorias y esperanzas colectivas; Nueva Visión: Buenos Aires, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elizalde, R.; Elizalde, A. La apuesta por la vida. Imaginación sociológica e imaginarios sociales en territorios ambientales del sur, de Enrique Leff 2019, 54, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, E. Desencuentros entre el imaginario social occidental y el imaginario social indígena: elementos para una reflexión teórica sobre los imaginarios sociales nucleares en el marco del conflicto entre el estado-nación chileno y el pueblo mapuche. Rev. Cuhso 2021, 31, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, G.; Caro-Zúñiga, C.A.; Arboleda-Ariza, J.C.; Schroder-Navarro, E.C.; González-Soto, M.L. Social imaginaries of youth in the Chilean press on climate change. Cuadernos.info 2023, 54, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D.; De Cock, C.; Whiteman, G. Future imaginings: Organizing in response to climate change. Organization 2013, 20, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, D.E. El cambio climático su imaginario social para la participación ciudadana. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10469/8754 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- García-Muñoz, C.M.; Gómez-Gallego, R.Á. Aproximación epistemológica a los imaginarios sociales como categoría analítica en las ciencias sociales. Rev. Guillermo Ockham 2021, 19, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauna, A.F. Alcance y problemas de la propuesta de Cornelius Castoriadis sobre los imaginarios sociales y el cambio social. Utopía y Prax. Latinoam. 2020, 25, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Murcia-Murcia, N. Imaginarios sociales sobre problemática ambiental: nuevos senderos para una educación ambiental. Educ. y Humanismo 2023, 25, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo-Pavón, I. Imaginarios sociales, representaciones sociales y re-presentaciones discursivas. Cinta de Moebio 2022, 74, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Mamani, E.; Chaiña Chura, F. F.; Salas Avila, D. A.; Belizario, G. Imaginario social de actores locales sobre la contaminación ambiental minera en el altiplano peruano. Rev. Ciencias Soc. 2022, XXVIII, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A. Cambio climático y conflictividad socioambiental en América Latina y el Caribe. América Lat. Hoy 2018, 79, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo-Pavón, I.; Lagos-Oróstica, O. El ocultamiento del símbolo y la imaginación: repercusiones en el sistema educativo actual. Perseitas 2022, 10, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffo-Pavón, I. La construcción del mensaje político a partir de los imaginarios sociales y el Framing. Atenea 2022, 525, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.J.; et al. Impactos socioeconómicos del cambio climático en América Latina y el Caribe: 2020-2045. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2016, 13, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.E.; Torres-Gómez, M.; Tironi-Silva, A.; Marín, V.H. Estrategia de adaptación local al cambio climático para el acceso equitativo al agua en zonas rurales de Chile. América Lat. Hoy 2015, 69, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Climate change, rainfall, society and disasters in Latin America: Relationsand needs. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2011, 28, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgen-Eide, G.; Gubrium, E. Climate change in Norway: Destabilized social imaginaries of welfare, growth, and nature in a rich oil state. EPE Nat. Sp. 2025, 8, 1002–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, L. A colonial lack of imagination: Climate futures between catastrophism and cruel eco-optimism. J. Polit. Ecol. 2024, 31, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincapié, S. Global environmental governance, human rights and socio-state capabilities in Latin America. Rev. CIDOB d’Afers Int. 2022, 130, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Motta; León, A.N. Cambiando de perspectiva en la economía de la mitigación del cambio climático. Cuad. Econ. 2017, 36, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W. A Question of balance. Weighing the options on global warming policies; Yale University Press: New Haven & London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, N. The economics of climate change. Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc. 2008, 98, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.J.; Hernádez, D. Cambio climático y agricultura: una revisión de la literatura con énfasis en América Latina. Trimest. Econ. 2016, 4, 459–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartay, R.; Poveda, E.; Buzetta, M.F. El cambio climático y la producción agrícola familiar y empresarial en América Latina. Agroalimentaria 2022, 28, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estenssoro, F. Crisis ambiental y cambio climático en la política global: Un tema crecientemente complejo para américa latina. Universum 2010, 2, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, O.; et al. Water consumption by agriculture in Latin America and the Caribbean: impact of climate change and applications of nuclear and isotopic techniques. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2022, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.; Herrador, D.; Manuel, C.; Mccall, M.K. Estrategias de adaptación al cambio climático en dos comunidades rurales De México y el Salvador. Boletín la Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2013, 61, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.A.; Rondinone, G.; De Salvo, C.P. Agricultural support policies and GHG emissions from agriculture in Latin America: relationships and policy implications for climate change. Iberoam. J. Dev. Stud. 2023, 12, 102–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.G.; De la Garza, L.A.; Hosman, L. Uso de bibliotecas digitales solares para la enseñanza del cambio climático en comunidades rurales. Rev. Interam. Bibliotecol. 2022, 45, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Rangel, Á.M.; Ibáñez-Velandia, A.Y. Education on climate change in rural communities in the municipality of la Calera (Cundinamarca, Colombia). Rev. Luna Azul 2020, 51, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la investigación; McGraw-Hill / Interamericana Editores: S.A. de C.V., México D.F., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C.P. Metodología de la investigación. Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta; McGraw-Hill Interamericana Editores: México D.F., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, V.E. Revisión documental. 2018, 1432, 2017–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, L.; Torruco, U.; Martínez, M.; Varela, M. La Entrevista, Recurso Flexible y Dinámico. Investig. en Educ. médica 2013, 2, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valles, M. S. Técnicas cualitativas de Investigación social. Reflexión metodológica y práctica profesional; Editorial Síntesis S. A.: Madrid, España, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, L. Guías para Elaborar Fichas Bibliográficas En la Redacción de Ensayos. In Monografías y Tesis; Univ. Puerto Rico; 2008; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bracho, Y. Capítulo III Marco Metodológico. Gestión Calid. en las Empres. del Sect. Azucar. del Occident. Venez. 2007, 2006, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles, J. Técnicas e Instrumentos de Investigación Científica, 1st ed.; Enfoques Consulting EIRL: Arequipa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barquín, A.; Arratibel, N.; Quintas, M.; Alzola, N. Percepción de las familias sobre la diversidad socioeconómica y de origen en su centro escolar. Un estudio cualitativo. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2022, 40, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Mamani, E.; Porto, H.; Ayamamani, P.; Turpo, O. Mediatización y crisis sociopolítica en Perú. Imaginarios y prácticas de actores sociales. Cuadernos.info 2023, 56, 22–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín, D. Teoría fundamentada y Atlas.ti: recursos metodológicos para la investigación educativa. Rev. electrónica Investig. Educ. 2016, 18, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pertegal-Felices, M.L.; Espín-León, A.; Jimeno-Morenilla, A. Diseño de un instrumento para medir identidad cultural indígena: caso de estudio sobre la nacionalidad amazónica Waorani. Rev. Estud. Soc. 2020, 71, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Mamani, E.; Quispe, W.; Turpo, O. Recentralización, conflictos intergubernamentales y desigualdad territorial: perspectiva de gobiernos locales en Perú. Rev. Adm. Pública 2023, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, P. Análisis cualitativo de contenido: Una alternativa metodológica alcanzable. 2003, II, 7–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayago, S. El Análisis del Discurso Como Técnica de Investigación Cualitativa y Cuantitativa en las Ciencias Sociales. Cinta de moebio 2014, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leff, E. Imaginarios sociales y sustentabilidad. Cult. y Represent. Soc. 2010, 5, 42–121. [Google Scholar]

- Estenssoro, F. Crisis Ambiental Global: ¿Una Crisis Antropogénica o Capitalogénica? Rev. Divergencia 2021, 10, 106–127. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Alier, J. Los conflictos ecológicos-distributivos y los indicadores de Sustentabilidad. P. Rev. Latinoam. Conc. y Pod. Mund. 2006, 13, 1–15. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/polis/5359 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Leff, E. La Ecología Política en América Latina. Un campo en construcción. P. Rev. Latinoam. 2003, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).