Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Development of Brain: First 1000 Days

3. Development of Gut Microbiota: The First 1000 Days

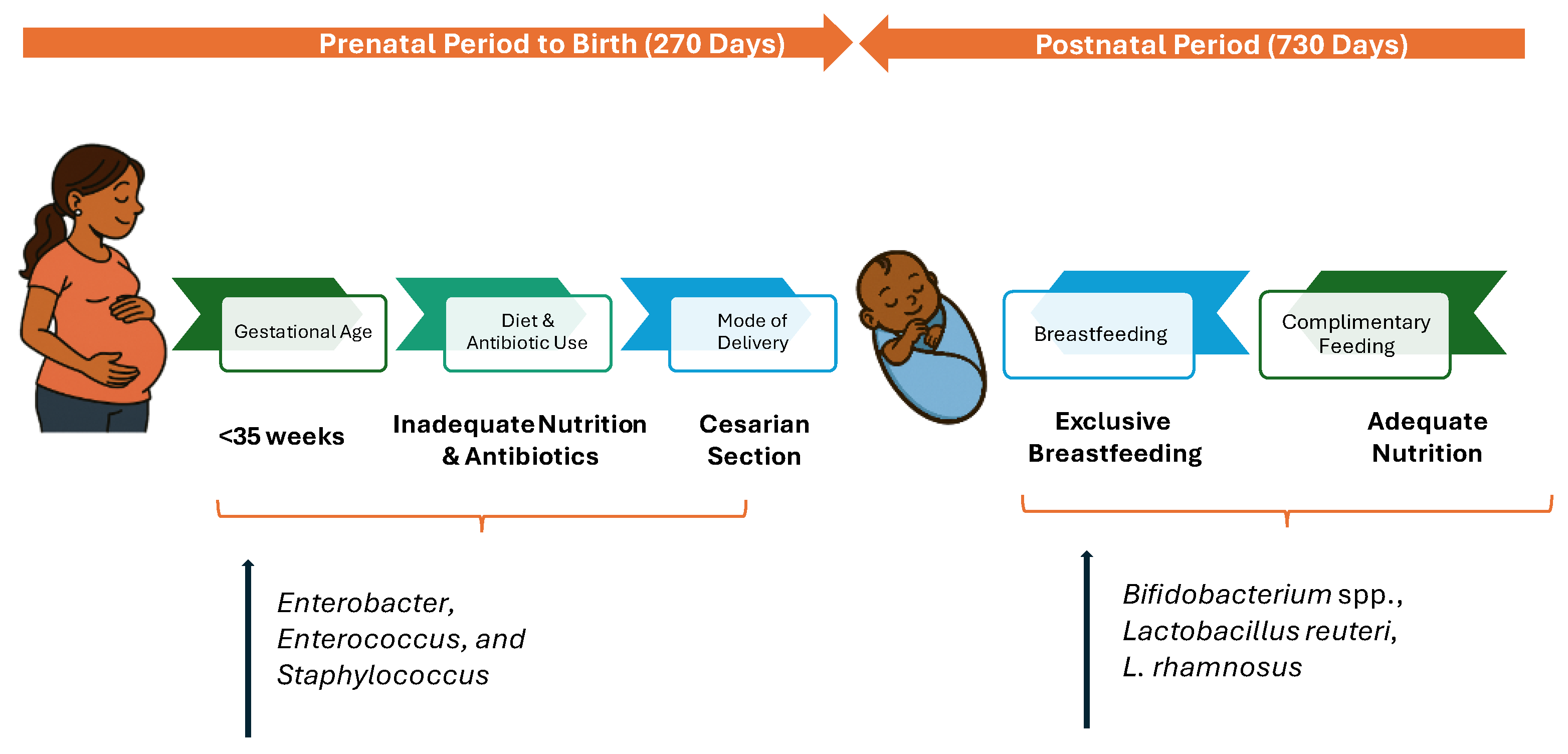

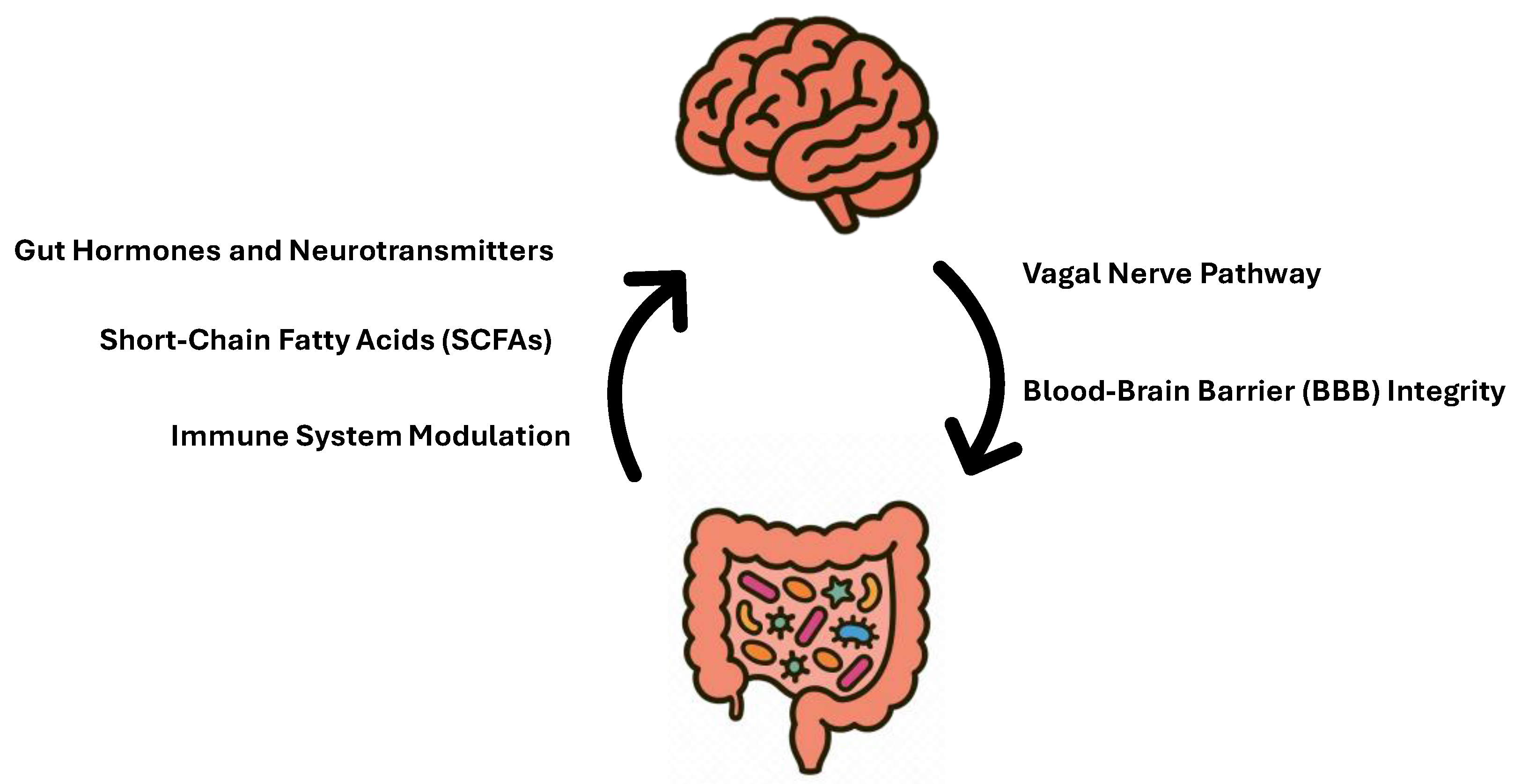

Factors Impacting Gut Microbiota in the First 1000 Days

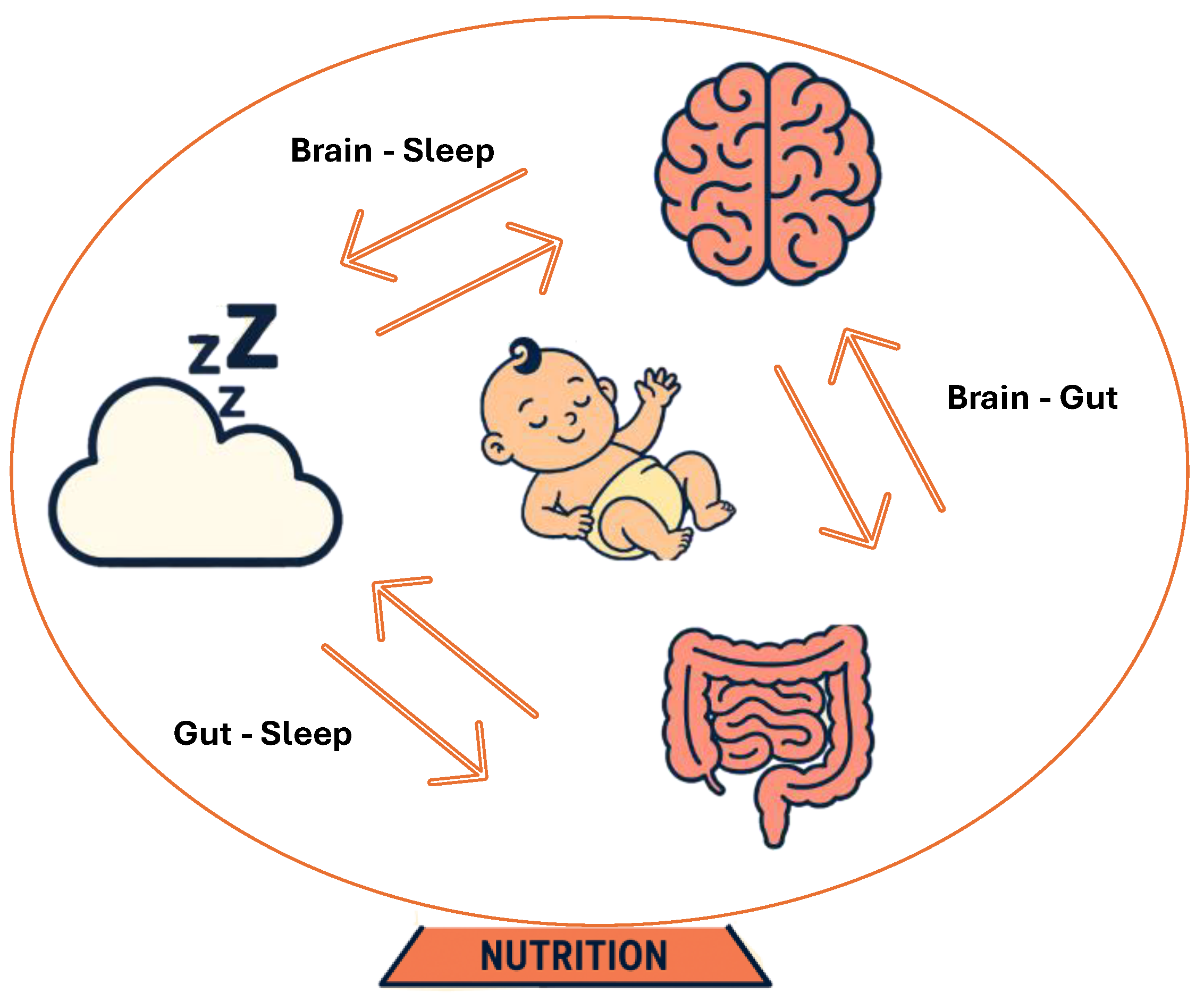

4. Development of Sleep: The First 1000 Days

5. Nutritional Needs: The First 1000 Days

5.1. Omega-3 Fatty Acids

5.2. Choline

5.3. Folate

5.4. Iodine

5.5. Vitamin B12

5.6. Iron

5.7. Vitamin D

5.8. Prebiotics and Probiotics

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-MTHF | 5-methyltetrahydrofolate |

| AS | active sleep |

| AdCbl | adenosylcobalamin |

| ASQ | Ages and Stages Questionnaire |

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorder |

| ALSPAC | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children |

| BSID-III | Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III |

| BB-12® | Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| C-section | caesarean section |

| CP | cerebral palsy |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CFU | colony-forming units |

| DQ | developmental quotients |

| DIAMOND | DHA Intake And Measurement Of Neural Development Study |

| DGA | Dietary Guidelines for Americans |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| EPA | eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EEG | electroencephalography |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| ERP | event-related potential |

| Ems | eye movements |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GID | gestational iodine deficiency |

| HMOs | human milk oligosaccharides |

| OHCbl | hydroxocobalamin |

| HPA | hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| IUGR | intrauterine growth restriction |

| IDA | Iron deficiency anemia |

| KUDOS | Kansas University DHA Outcomes Study |

| L. | Lactobacillus |

| LA | linoleic acid |

| MeCbl | methylcobalamin |

| MTHFR | methyltetrahydrofolate reductase |

| MGBA | microbiota-gut-brain axis |

| MoBa | Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study |

| MMN | multiple micronutrients |

| NAPLAN | National Assessment Program Literacy and Numeracy |

| NARA II | Neale Analysis of Reading Ability-II |

| NTDs | neural tube defects |

| NDDs | neurodevelopmental disorders |

| NREM | Non-Rapid Eye Movement |

| PEMT | phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| PDX/GOS | polydextrose and galactooligosaccharides |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| QS | quiet sleep |

| REM | Rapid Eye Movement |

| RBC | red blood cell |

| RLS | restless leg syndrome |

| SIgA | secretory immunoglobulin A |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| SGA | small-for-gestational-age |

| SPF | specific pathogen free |

| TSH | thyroid stimulating hormone |

| USPSTF | United States Preventive Services Task Force |

| UICs | urinary iodine concentrations |

| VEPs | visual evoked potentials |

| WPPSI- III | Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence- III |

| WISC-III | Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children-III |

| ALA | α-linolenic acid |

References

- Maldonado KA, A. K. Physiology, Brain. In StatPearls [Internet], 2025.

- Stiles J, J. T. The basics of brain development. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010, 327–348.

- Aguayo VM, B. P. The first and next 1000 days: a continuum for child development in early life. Lancet 2024.

- Yassin LK, N. M., Alderei A, Almehairbi A, Mydeen AB, Akour A, Hamad MIK. Exploring the microbiota-gut-brain axis: impact on brain structure and function. Front Neuroanat. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk M, S. A., Witkowska AM. The Role of Gut Microbiome in Sleep Quality and Health: Dietary Strategies for Microbiota Support. Nutrients 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yao Y, C. X., Ye Y, Wang F, Chen F, Zheng C. The Role of Microbiota in Infant Health: From Early Life to Adulthood. Front Immunol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rathore K, S. N., Naik S et al. The Bidirectional Relationship Between the Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2025.

- Zimmermann P, K. S., Giannoukos S, Stocker M, Bokulich NA. NapBiome trial: Targeting gut microbiota to improve sleep rhythm and developmental and behavioural outcomes in early childhood in a birth cohort in Switzerland - a study protocol. BMJ Open. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Alrousan G, H. A., Pillai AA, Atrooz F, Salim S. Early Life Sleep Deprivation and Brain Development: Insights From Human and Animal Studies. Front Neurosci. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Frank S, G. K., Lee-Ang L, Young MC, Tamez M, Mattei J. Diet and Sleep Physiology: Public Health and Clinical Implications. Front Neurol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk M, M.-C. I., Witkowska AM. Sleep Quality: A Narrative Review on Nutrition, Stimulants, and Physical Activity as Important Factors. Nutrients 2022. [CrossRef]

- Singh R, M. S. Embryology, Neural Tube. StatPearls Publishing, 2023.

- Marshall NE, A. B., Barbour LA et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: lifelong consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022, 607–632. [CrossRef]

- Folic Acid Supplementation to Prevent Neural Tube Defects: US Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement; JAMA, 2023.

- Kwak DW, K. S., Lee SY, et al. Maternal Anemia during the First Trimester and Its Association with Psychological Health. Nutrients 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wiegersma AM, D. C., Lee BK, Karlsson H, Gardner RM. Association of Prenatal Maternal Anemia With Neurodevelopmental Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Wei, LL., Zhu, XH. et al. Prenatal stress modulates HPA axis homeostasis of offspring through dentate TERT independently of glucocorticoids receptor. Mol Psychiatry 2023, 1383–1395. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap A, J. B., Jagtap R, Lamture Y, Gomase K. Effects of Prenatal Stress on Behavior, Cognition, and Psychopathology: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Araki M, N. S., Ushimaru K, Masuzaki H, Oishi K, Shinohara K. Fetal response to induced maternal emotions. J Physiol Sci. 2010, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Victoria Ronan, R. Y., Erika C. Claud. Childhood Development and the Microbiome—The Intestinal Microbiota in Maintenance of Health and Development of Disease During Childhood Development. Gastroenterology 2021, 160 (2), 495–506.

- Snigdha S, H. K., Tsai P, Dinan TG, Bartos JD, Shahid M. Probiotics: Potential novel therapeutics for microbiota-gut-brain axis dysfunction across gender and lifespan. Pharmacol Ther. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Sharon G, S. T., Geschwind DH, Mazmanian SK. The Central Nervous System and the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2016, 915–932. [CrossRef]

- Katarzyna Socała, U. D., Aleksandra Szopa, Anna Serefko, Marcin Włodarczyk. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacological Research 2021, 172. [CrossRef]

- Dinan TG, C. J. Gut instincts: microbiota as a key regulator of brain development, ageing and neurodegeneration. J Physiol. 2017, 595 (2), 489–503.

- Fiona Fouhy, C. W., Cian J. Hill, Carol-Anne O’Shea, Brid Nagle, Eugene M. Dempsey, Paul W. O’Toole, R. Paul Ross, C. Anthony Ryan, Catherine Stanton. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nature Communications 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chernikova, D. A., Madan, J.C., Housman, M.L. et al. The premature infant gut microbiome during the first 6 weeks of life differs based on gestational maturity at birth. Pediatr Res 2018, 84, 71–79. [CrossRef]

- Fouhy F, W. C., Hill CJ, O’Shea CA, Nagle B, Dempsey EM, O’Toole PW, Ross RP, Ryan CA, Stanton C. Perinatal factors affect the gut microbiota up to four years after birth. Nat Commun. 2019, 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Korpela K., B. E. W., Moltu S. J., Strommen K., Nakstad B., Ronnestad A. E., et al. Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in preterm neonates. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8 (1), 2453. [CrossRef]

- Reyman, M., van Houten, M.A., van Baarle, D. et al. Impact of delivery mode-associated gut microbiota dynamics on health in the first year of life. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4997.

- Zhang C, L. L., Jin B, Xu X, Zuo X, Li Y, Li Z. The Effects of Delivery Mode on the Gut Microbiota and Health: State of Art. Front Microbiol. 2021, 23 (12). [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Bello M. G., C. E. K., Contreras M., Magris M., Hidalgo G., Fierer N., et al. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [CrossRef]

- Korpela K, S. A., Vepsäläinen O, Suomalainen M. Probiotic supplementation restores normal microbiota composition and function in antibiotic-treated and in caesarean-born infants. Microbiome 2018. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G., Werler, Kelley, et al. Medication Use during Pregnancy, with Particular Focus on Prescription Drugs: 1976-2008. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2011, 205 (1).

- Patangia DV, A. R. C., Dempsey E, Paul Ross R, Stanton C. Impact of antibiotics on the human microbiome and consequences for host health. Microbiologyopen. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Davis EC, C. V., Sela DA, Hillard MA, Lindberg S, Mantis NJ, Seppo AE, Järvinen KM. Gut microbiome and breast-feeding: Implications for early immune development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022, 150 (3), 523–534. [CrossRef]

- van den Elsen Lieke W. J., G. J., Burcelin Remy, Verhasselt Valerie. Shaping the Gut Microbiota by Breastfeeding: The Gateway to Allergy Prevention? Frontiers in Pediatrics 2019, 7, 2296–2360.

- Berger PK, O. M., Bode L, Belfort MB. Human Milk Oligosaccharides and Infant Neurodevelopment: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15 (3), 719. [CrossRef]

- Jingran Ma, Z. L., Wenjuan Zhang, Chunli Zhang, Yuheng Zhang, Hua Mei, Na Zhuo, Hongyun Wang, Lin Wang & Dan Wu. Comparison of gut microbiota in exclusively breast-fed and formula-fed babies: a study of 91 term infants. Scientific Reports 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Hill DR, B. R. Infants Fed Breastmilk or 2’-FL Supplemented Formula Have Similar Systemic Levels of Microbiota-Derived Secondary Bile Acids. Nutrients 2023, 15 (10), 2339.

- Homann CM, R. C., Dizzell S, Bervoets L, Simioni J, Li J, Gunn E, Surette MG, de Souza RJ, Mommers M, Hutton EK, Morrison KM, Penders J, van Best N, Stearns JC. Infants’ First Solid Foods: Impact on Gut Microbiota Development in Two Intercontinental Cohorts. Nutrients 2021, 13 (8). [CrossRef]

- Shigemitsu Tanaka, T. K., Prapa Songjinda, Atsushi Tateyama, Mina Tsubouchi, Chikako Kiyohara, Taro Shirakawa, Kenji Sonomoto, Jiro Nakayama. Influence of antibiotic exposure in the early postnatal period on the development of intestinal microbiota. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 2009, 56 (1), 80–87. [CrossRef]

- R.D. Heijtz, S. W., F. Anuar, Y. Qian, B. Björkholm, A. Samuelsson, M.L. Hibberd, H. Forssberg, S. Pettersson. Normal gut microbiota modulates brain development and behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108 (7), 3047–3052. [CrossRef]

- Boehme M, G. K., Bastiaanssen TFS, van de Wouw M, Moloney GM, Gual-Grau A, Spichak S, Olavarría-Ramírez L, Fitzgerald P, Morillas E, Ritz NL, Jaggar M, Cowan CSM, Crispie F, Donoso F, Halitzki E, Neto MC, Sichetti M, Golubeva AV, Fitzgerald RS, Clae. Microbiota from young mice counteracts selective age-associated behavioral deficits. Nat Aging. 2021, 1 (8), 666–676. [CrossRef]

- Dash S, S. Y., Khan MR. Understanding the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Brain Development and Its Association With Neurodevelopmental Psychiatric Disorders. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson T, M. F., Taylor MJ, Jonsson U, Bölte S. Early environmental risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders - a systematic review of twin and sibling studies. Dev Psychopathol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Marilia Carabotti, A. S., Maria Antonietta Maselli, Carola Severi. The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol 2015, 203–209.

- Javier Ochoa-Repáraz, L. H. K. The Second Brain: Is the Gut Microbiota a Link Between Obesity and Central Nervous System Disorders? Curr Obes Rep. 2017, 5 (1), 51–64.

- Fabian Streit, E. P., Tabea Send, Lea Zillich, Josef Frank, Sarven Sabunciyan, Jerome Foo, Lea Sirignano, Bettina Lange, Svenja Bardtke, Glen Hatfield, Stephanie H Witt, Maria Gilles, Marcella Rietschel, Michael Deuschle, Robert Yolken. Microbiome profiles are associated with cognitive functioning in 45-month-old children. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2021, 98, 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Frerichs NM, d. M. T., Niemarkt HJ. Microbiome and its impact on fetal and neonatal brain development: current opinion in pediatrics. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2024, 27 (3), 297–303. [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Mörkl, M. I. B., Jolana Wagner-Skacel. Gut-brain-crosstalk- the vagus nerve and the microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression. A narrative review. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports 2023, 13.

- Cheng H, Y. W., Xu H, Zhu W, Gong A, Yang X, Li S, Xu H. Microbiota metabolites affect sleep as drivers of brain--gut communication (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kim GH, S. J. Gut microbiota affects brain development and behavior. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2023, 274–280.

- Bravo JA, F. P., Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Sejbuk M, S. A., Witkowska AM. The Role of Gut Microbiome in Sleep Quality and Health: Dietary Strategies for Microbiota Support. Nutrients 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gwak MG, C. S. Gut-Brain Connection: Microbiome, Gut Barrier, and Environmental Sensors. Immune Netw. 2021.

- Barandouzi, Z. A., Lee, J., del Carmen Rosas, M. et al. Associations of neurotransmitters and the gut microbiome with emotional distress in mixed type of irritable bowel syndrome. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1648. [CrossRef]

- LMT, D. Gut Bacteria and Neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022.

- Hsu Chou-Yi, K. L. G., Younis Nada Khairi, Mustafa Mohammed Ahmed, Ahmad Nabeel, Athab Zainab H., Polyanskaya Angelina V., Kasanave Elena Victorovna, Mirzaei Rasoul, Karampoor Sajad. Microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids in pediatric health and diseases: from gut development to neuroprotection. Frontiers in Microbiology 2024, 15.

- Kim, H. J., Leeds, P., and Chuang, D. M. The HDAC inhibitor, sodium butyrate, stimulates neurogenesis in the ischemic brain. J. Neurochem 2009, 110, 1226–1240. [CrossRef]

- Kadry, H., Noorani, B. & Cucullo, L. A blood–brain barrier overview on structure, function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17 (69). [CrossRef]

- Dotiwala AK, M. C., Samra NS. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Blood Brain Barrier. 2023.

- Braniste, V. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D., Liwinski, T. & Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res 2020, 492–506. [CrossRef]

- Yoo JY, G. M., Dutra SVO, Sarkar A, McSkimming DI. Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions. Microorganisms 2020. [CrossRef]

- Grandner MA, F. F. The translational neuroscience of sleep: A contextual framework. Science 2021, 568–573.

- Donovan T, D. K., Penman A, Young RJ, Reid VM. Fetal eye movements in response to a visual stimulus. Brain Behav. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wong SD, W. K. J., Spencer RL et al. Development of the circadian system in early life: maternal and environmental factors. J Physiol Anthropol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tham EK, S. N., Broekman BF. Infant sleep and its relation with cognition and growth: a narrative review. Nat Sci Sleep 2017, 135–149. [CrossRef]

- Schoch SF, C.-M. J., Krych L, Leng B, Kot W, Kohler M, Huber R, Rogler G, Biedermann L, Walser JC, Nielsen DS, Kurth S. From Alpha Diversity to Zzz: Interactions among sleep, the brain, and gut microbiota in the first year of life. Prog Neurobiol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, J., Carlson, S.E., Algarín, C. et al. Developmental effects on sleep–wake patterns in infants receiving a cow’s milk-based infant formula with an added prebiotic blend: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatr Res 2021, 1222–1231. [CrossRef]

- Helseth S, M. N., Småstuen M, Andenæs R, Valla L. Infant colic, young children’s temperament and sleep in a population based longitudinal cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen K, Z. G., Xie H et al. Efficacy of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, BB-12® on infant colic - a randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Benef Microbes 2021.

- Jiang, F. Sleep and Early Brain Development. Ann Nutr Metab 2019, 44–54. [CrossRef]

- Patel AK, R. V., Shumway KR, et al. Physiology, Sleep Stages. In StatPearls [Internet]. 2025.

- Khan MA, A.-J. H. The consequences of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2023, 91–99.

- How Lack of Sleep Impacts Cognitive Performance and Focus. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-deprivation/lack-of-sleep-and-cognitive-impairment#:~:text=Alzheimer’s%20Disease:%20Research%20shows%20that,were%20attributable%20to%20poor%20sleep. (accessed July 18).

- Gina M. Mason, a. R. M. C. S. Sleep and Memory in Infancy and Childhood. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology 2022, 89–108. [CrossRef]

- Sun W, L. S., Jiang Y, Xu X, Spruyt K, Zhu Q, Tseng CH, Jiang F. A Community-Based Study of Sleep and Cognitive Development in Infants and Toddlers. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018, 977–984. [CrossRef]

- S. Seehagen, C. K., J.S. Herbert,& S. Schneider. Timely sleep facilitates declarative memory consolidation in infants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 1625–1629. [CrossRef]

- Dionne G, T. E., Forget-Dubois N, Petit D, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY, Boivin M. Associations between sleep-wake consolidation and language development in early childhood: a longitudinal twin study. Sleep 2011, 987–995. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Reif M, G. N. Infant sleep behaviors relate to their later cognitive and language abilities and morning cortisol stress hormone levels. Infant Behav Dev. 2022.

- Liang X, Z. X., Wang Y, van IJzendoorn MH, Wang Z. Sleep problems and infant motor and cognitive development across the first two years of life: The Beijing Longitudinal Study. Infant Behav Dev. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Likhar A, P. M. Cureus. Importance of Maternal Nutrition in the First 1,000 Days of Life and Its Effects on Child Development: A Narrative Review 2022.

- Cohen Kadosh K, M. L., Parikh P, Basso M, Jan Mohamed HJ, Prawitasari T, Samuel F, Ma G, Geurts JM. Nutritional Support of Neurodevelopment and Cognitive Function in Infants and Young Children-An Update and Novel Insights. Nutrients 2021.

- Chang CY, K. D., Chen JY. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2009, 231–241.

- Basak S, M. R., Duttaroy AK. Maternal Docosahexaenoic Acid Status during Pregnancy and Its Impact on Infant Neurodevelopment. Nutrients. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ghazal RM, N. M. Omega-3 fatty acids and fetal brain development: implications for maternal nutrition, mechanisms of cognitive function, and pediatric depression. Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2025.

- Krauss-Etschmann S, S. R., Campoy C et al. Nutrition and Health Lifestyle (NUHEAL) Study Group. Effects of fish-oil and folate supplementation of pregnant women on maternal and fetal plasma concentrations of docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid: a European randomized multicenter trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007, 1392–1400. [CrossRef]

- Hu R, X. J., Hua Y, Li Y, Li J. Could early life DHA supplementation benefit neurodevelopment? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Masha L Shulkin, L. P., David Bellinger, Sarah Kranz, Christopher Duggan, Wafaie Fawzi, Dariush Mozaffarian. Effects of omega-3 supplementation during pregnancy and youth on neurodevelopment and cognition in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In Experimental Biology 2016 Meeting, 2016.

- Berthold Koletzko, I. C., and J. Thomas Brenna. Consensus Statement- Dietary fat intakes for pregnant and lactating women. British Journal of Nutrition 2007.

- Colombo J, S. D., Gustafson K, Gajewski BJ, Thodosoff JM, Kerling E, Carlson SE. The Kansas University DHA Outcomes Study (KUDOS) clinical trial: long-term behavioral follow-up of the effects of prenatal DHA supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ostadrahimi A, S.-P. H., Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Heidarabady S, Farshbaf-Khalili A. The effect of perinatal fish oil supplementation on neurodevelopment and growth of infants: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr. 2018, 2387–2397. [CrossRef]

- Shindou H, K. H., Sasaki J, Nakanishi H, Sagara H, Nakagawa KM, Takahashi Y, Hishikawa D, Iizuka-Hishikawa Y, Tokumasu F, Noguchi H, Watanabe S, Sasaki T, Shimizu T. Docosahexaenoic acid preserves visual function by maintaining correct disc morphology in retinal photoreceptor cells. J Biol Chem. 2017, 12054–12064. [CrossRef]

- Malcolm CA, M. D., Montgomery C, Shepherd A, Weaver LT. Maternal docosahexaenoic acid supplementation during pregnancy and visual evoked potential development in term infants: a double blind, prospective, randomised trial. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003, 383–390. [CrossRef]

- Jensen CL, V. R., Prager TC, Zou YL, Fraley JK, Rozelle JC, Turcich MR, Llorente AM, Anderson RE, Heird WC. Effects of maternal docosahexaenoic acid intake on visual function and neurodevelopment in breastfed term infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005, 125–132.

- Hibbeln J. R., D. J. M., Steer C., Emmett P. M., Rogers I., Williams C., et al. Maternal seafood consumption in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood (ALSPAC study): an observational cohort study. Lancet 2007, 578–585. [CrossRef]

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025. 2020.

- Advice about Eating Fish. https://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/advice-about-eating-fish (accessed October).

- Cetin, I. e. a. Omega-3 fatty acid supply in pregnancy for risk reduction of preterm and early preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2024. [CrossRef]

- Martin CR, L. P., Blackburn GL. Review of Infant Feeding: Key Features of Breast Milk and Infant Formula. Nutrients 2016. [CrossRef]

- Birch EE, C. S., Hoffman DR et al. The DIAMOND (DHA Intake And Measurement Of Neural Development) Study: a double-masked, randomized controlled clinical trial of the maturation of infant visual acuity as a function of the dietary level of docosahexaenoic acid. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010, 848–859. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman DR, T. R., Castañeda YS, Wheaton DH, Bosworth RG, O’Connor AR, Morale SE, Wiedemann LE, Birch EE. Maturation of visual acuity is accelerated in breast-fed term infants fed baby food containing DHA-enriched egg yolk. J Nutr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Chen, C, Luo J. et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, and mercury in relation to sleep duration and sleep quality: Findings from the CARDIA study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 753–762. [CrossRef]

- Cheruku SR, M.-D. H., Farkas SL et al. Higher maternal plasma docosahexaenoic acid during pregnancy is associated with more mature neonatal sleep-state patterning. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002, 608–613.

- Judge MP, C. X., Harel O et al. Maternal consumption of a DHA-containing functional food benefits infant sleep patterning: an early neurodevelopmental measure. Early Hum Dev. 2012, 531–537. [CrossRef]

- Christian LM, B. L., Porter K et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (PUFA) Status in Pregnant Women: Associations with Sleep Quality, Inflammation, and Length of Gestation. PLoS One. 2016. [CrossRef]

- (UNICEF)., U. N. C. s. F. Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period. 2020. https://www.unicef.org/media/93981/file/Complementary-Feeding-Guidance-2020.pdf (accessed).

- Derbyshire E, O. R. Choline, Neurological Development and Brain Function: A Systematic Review Focusing on the First 1000 Days. Nutrients. 2020.

- Wallace, T. C., Blusztajn, Jan Krzysztof, Caudill, Marie A. et al. Choline: The Underconsumed and Underappreciated Essential Nutrient. Nutrition 2018, 240–253.

- Strupp BJ, P. B., Velazquez R, Ash JA, Kelley CM, Alldred MJ, Strawderman M, Caudill MA, Mufson EJ and Ginsberg SD. Maternal Choline Supplementation: A Potential Prenatal Treatment for Down Syndrome and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- SH., S. L. a. Z. Choline: Dietary Requirements and Role in Brain Development. Nutr Today. 2007, 181–186.

- Shaw GM, C. S., Yang W, Selvin S, Schaffer DM. Periconceptional dietary intake of choline and betaine and neural tube defects in offspring. Am J Epidemiol. 2004, 102–109. [CrossRef]

- Shaw GM, C. S., Laurent C, Rasmussen SA. Maternal nutrient intakes and risk of orofacial clefts. Epidemiology 2006, 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Boeke CE, G. M., Hughes MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Villamor E, Oken E. Choline intake during pregnancy and child cognition at age 7 years. Am J Epidemiol 2013, 1338–1347. [CrossRef]

- Caudill MA, S. B., Muscalu L, Nevins JEH, Canfield RL. Maternal choline supplementation during the third trimester of pregnancy improves infant information processing speed: a randomized, double-blind, controlled feeding study. FASEB J. 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Charlotte L. Bahnfleth, B. J. S., Marie A. Caudill, Richard L. Canfield. Prenatal choline supplementation improves child sustained attention: A 7-year follow-up of a randomized controlled feeding trial. FASEB J. 2022. [CrossRef]

- da Costa KA, N. M., Craciunescu CN, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH. Choline deficiency increases lymphocyte apoptosis and DNA damage in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006, 88–94. [CrossRef]

- Agriculture, W. W. R. S. U. S. D. o. Eye on Nutrition: Choline. 2020. https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/resources/eye-nutrition-choline (accessed).

- Sauder KA, C. G., Bailey RL et al. Selecting a dietary supplement with appropriate dosing for 6 key nutrients in pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2023, 823–829. [CrossRef]

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025; USDA Publication #: USDA-FNS-2020-2025-DGA, 2020.

- Andrew MJ, P. J., Montague-Johnson C, Laler K, Qi C, Baker B, Sullivan PB. Nutritional intervention and neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with suspected cerebral palsy: the Dolphin infant double-blind randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neuro 2018. [CrossRef]

- F., S. T. The concept of folic acid supplementation and its role in prevention of neural tube defect among pregnant women: PRISMA. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024.

- Mahmood, L. The metabolic processes of folic acid and Vitamin B12 deficiency. Journal of Health Research and Reviews 2014, 5–9. [CrossRef]

- Naninck EFG, S. P., Brouwer-Brolsma EM. The Importance of Maternal Folate Status for Brain Development and Function of Offspring. Adv Nutr. 2019, 502–519. [CrossRef]

- Zhou D, L. Z., Sun Y, Yan J, Huang G, Li W. Early Life Stage Folic Acid Deficiency Delays the Neurobehavioral Development and Cognitive Function of Rat Offspring by Hindering De Novo Telomere Synthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Naninck EFG, S. P., Brouwer Brolsma EM. The Importance of Maternal Folate Status for Brain Development and Function of Offspring. Adv Nutr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Scaglione F, P. G. Folate, folic acid and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate are not the same thing. Xenobiotica 2014, 480–488.

- Nishigori, H., Nishigori, T., Obara, T. et al. Prenatal folic acid supplement/dietary folate and cognitive development in 4-year-old offspring from the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Sci Rep 2023. [CrossRef]

- McNulty, H., Rollins, M., Cassidy, T. et al. Effect of continued folic acid supplementation beyond the first trimester of pregnancy on cognitive performance in the child: a follow-up study from a randomized controlled trial (FASSTT Offspring Trial). BMC Med 2019. [CrossRef]

- Compañ-Gabucio LM, T.-C. L., Garcia-de la Hera M, Fernández-Somoano A, Tardón A, Julvez J, Sunyer J, Rebagliato M, Murcia M, Ibarluzea J, Santa-Marina L, Vioque J. Association between the Use of Folic Acid Supplements during Pregnancy and Children’s Cognitive Function at 7-9 Years of Age in the INMA Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19 (9), 12123. [CrossRef]

- Valera-Gran D, N.-M. E., Garcia de la Hera M et. al. Effect of maternal high dosages of folic acid supplements on neurocognitive development in children at 4-5 y of age: the prospective birth cohort Infancia y Medio Ambiente (INMA) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017, 878–887.

- Nutrition During Pregnancy- FAQs. 2025.

- McNulty, H., Dowey, LRC, Strain, JJ et al. Riboflavin lowers homocysteine in individuals homozygous for the MTHFR 677C→T polymorphism. Circulation 2006, 74–80. [CrossRef]

- Conversion of calcium- L -methylfolate and(6S)-5-methyltetrahydrofolic acid glucosamine salt intodietary folate equivalents. EFSA Journal 2022, 7452.

- Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. 2001.

- Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes; 2006.

- MB., Z. The effects of iodine deficiency in pregnancy and infancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012.

- Hynes, K. L., Otahal, P., Hay, I. and Burgess. Mild iodine deficiency during pregnancy is associated with reduced educational outcomes in the offspring: 9-year follow-up of the gestational iodine cohort. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013. [CrossRef]

- de Escobar GM, O. M., del Rey FE. Iodine deficiency and brain development in the first half of pregnancy. Public Health Nutr. 2007.

- SA., S. Iodine deficiency in pregnancy: the effect on neurodevelopment in the child. Nutrients 2011, 265–273.

- Bath SC, S. C., Golding J, Emmett P, Rayman MP. Effect of inadequate iodine status in UK pregnant women on cognitive outcomes in their children: results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Lancet 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mariacarla Moleti, V. P. L. P., Maria Cristina Campolo et. al. Iodine Prophylaxis Using Iodized Salt and Risk of Maternal Thyroid Failure in Conditions of Mild Iodine Deficiency. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2008.

- Markhus MW, D. L., Moe V et. al. Maternal Iodine Status is Associated with Offspring Language Skills in Infancy and Toddlerhood. Nutrients 2018.

- Nina H. van Mil, H. T., Jacoba J. Bongers-Schokking. Low Urinary Iodine Excretion during Early Pregnancy Is Associated with Alterations in Executive Functioning in Children. The Journal of Nutrition: Nutritional Epidemiology 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hisada A, T. R., Yamamoto M, Nakaoka H, Sakurai K, Mori C. The Japan Environment And Children’s Study Jecs Group. Maternal Iodine Intake and Neurodevelopment of Offspring: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Nutrients 2022. [CrossRef]

- Velasco I, C. M., Santiago P, Muela JA. Effect of iodine prophylaxis during pregnancy on neurocognitive development of children during the first two years of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Machamba AAL, A. F., Fracalossi KO, do C C Franceschini S. Effect of iodine supplementation in pregnancy on neurocognitive development on offspring in iodine deficiency areas: a systematic review. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Pretell, E. A., Torres, T., Zenteno, V., & Cornejo, M. Prophylaxis of endemic goiter with iodized oil in rural Peru. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1972.

- Nawaz, A., Khattak, N.N., Khan, M.S. et al. Deficiency of vitamin B12 and its relation with neurological disorders: a critical review. JoBAZ 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pentieva K, C. A., Duffy B, et al. B-vitamins and one-carbon metabolism during pregnancy: health impacts and challenges. In Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 2024; pp 1–15.

- Korsmo HW, J. X. One carbon metabolism and early development: a diet-dependent destiny. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 579–593.

- Idris N, A. A. Vitamin B12 deficiency presenting as pancytopenia in pregnancy: a case report. Malays Fam Physician. 2012, 46–50.

- Cruz-Rodríguez J, D.-L. A., Canals-Sans J, Arija V. Maternal Vitamin B12 Status during Pregnancy and Early Infant Neurodevelopment: The ECLIPSES Study. Nutrients 2023. [CrossRef]

- Golding J, G. S., Clark R, Iles-Caven Y, Ellis G, Taylor CM, Hibbeln J. Maternal prenatal vitamin B12 intake is associated with speech development and mathematical abilities in childhood. Nutr Res. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S., Thomas, T., Bosch, R.J. et al. Effect of Maternal Vitamin B12 Supplementation on Cognitive Outcomes in South Indian Children: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Matern Child Health J 2019, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- D’souza N, B. R., Patni B. et al. Pre-conceptional Maternal Vitamin B12 Supplementation Improves Offspring Neurodevelopment at 2 Years of Age: PRIYA Trial. Front Pediatr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Paul C, B. D. Comparative Bioavailability and Utilization of Particular Forms of B12 Supplements With Potential to Mitigate B12-related Genetic Polymorphisms. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2017.

- Sourander A, S. S., Surcel HM, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, Upadhyaya S, McKeague IW, Cheslack-Postava K, Brown AS. Maternal Serum Vitamin B12 during Pregnancy and Offspring Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients 2023. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein JL, F. A., Venkatramanan S, Layden AJ, Williams JL, Crider KS, Qi YP. Vitamin B12 supplementation during pregnancy for maternal and child health outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2024. [CrossRef]

- Duggan C, S. K., Thomas T, et al. Vitamin B-12 supplementation during pregnancy and early lactation increases maternal, breast milk, and infant measures of vitamin B-12 status. J Nutr 2014. [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour N, H. R., Kelishadi R. Review on iron and its importance for human health. J Res Med Sci. 2014, 164–174.

- Georgieff MK, K. N., Cusick SE. The Benefits and Risks of Iron Supplementation in Pregnancy and Childhood. Annu Rev Nutr. 2019, 121–146. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy EK, M. D., Kiely ME. Iron deficiency during the first 1000 days of life: are we doing enough to protect the developing brain? Proc Nutr Soc. 2022, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Vázquez L, V. N., Hernández-Martínez C et. al. Importance of Maternal Iron Status on the Improvement of Cognitive Function in Children After Prenatal Iron Supplementation. Am J Prev Med 2023, 395–405.

- Alshwaiyat NM, A. A., Wan Hassan WMR, Al-Jamal HAN. Association between obesity and iron deficiency (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021.

- CJ., P. Iron Supplementation in Pregnancy and Risk of Gestational Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022.

- Idjradinata P, P. E. Reversal of developmental delays in iron-deficient anaemic infants treated with iron. Lancet 1993 341 (8836), 1–4.

- Diagnosis and Prevention of Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia in Infants and Young Children (0–3 Years of Age). Pediatrics 2010, 1040–1050.

- McCann S, M. L., Milosavljevic B, Mbye E et. al. Iron status in early infancy is associated with trajectories of cognitive development up to pre-school age in rural Gambia. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023.

- Berglund SK, W. B., Hägglöf B, Hernell O, Domellöf M. Effects of iron supplementation of LBW infants on cognition and behavior at 3 years. Pediatrics 2013. [CrossRef]

- McCann JC, A. B. An overview of evidence for a causal relation between iron deficiency during development and deficits in cognitive or behavioral function. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007.

- Awlachew S, D. A., Jibro U, Tura AK. Pregnant women’s sleep quality and its associated factors among antenatal care attendants in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2025, 15 (1), 15613. [CrossRef]

- Kaya SP, Ö. F., Dilbaz B. Factors affecting poor sleep quality in last trimester pregnant women: a cross-sectional research from Turkey. Rev Assoc Med Bras 2024, 70 (9), e20240180. [CrossRef]

- Al Hinai M, J. E., Song PX, Peterson KE, Baylin A. Iron Deficiency and Vitamin D Deficiency Are Associated with Sleep in Females of Reproductive Age: An Analysis of NHANES 2005-2018 Data. J Nutr. 2024, 154 (2), 648–657.

- Rodrigues Junior JI, M. V., de Oliveira Lima M, Menezes RCE, Oliveira PMB, Longo-Silva G. Association between iron deficiency anemia and sleep duration in the first year of life. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2023, 24 (42), e2022173.

- Kordas K, S. E., Olney DK, Katz J, Tielsch JM, Kariger PK, Khalfan SS, LeClerq SC, Khatry SK, Stoltzfus RJ. The effects of iron and/or zinc supplementation on maternal reports of sleep in infants from Nepal and Zanzibar. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009, 30 (2), 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Barroso RM, P. P., Algarin C, Kaciroti N, Lozoff B. Motor activity and intra-individual variability according to sleep-wake states in preschool-aged children with iron-deficiency anemia in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2013, 89 (12), 1025–1031. [CrossRef]

- Gáll Z, S. O. Role of Vitamin D in Cognitive Dysfunction: New Molecular Concepts and Discrepancies between Animal and Human Findings. Nutrients 2021.

- Pet MA, B.-B. E. The Impact of Maternal Vitamin D Status on Offspring Brain Development and Function: a Systematic Review. Adv Nutr. 2016.

- Mulligan ML, F. S., Riek AE, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Implications of vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Rodgers MD, M. M., McWhorter CA, Ebeling MD, Shary JR, Newton DA, Baatz JE, Gregoski MJ, Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D and Child Neurodevelopment-A Post Hoc Analysis. Nutrients 2023.

- De Marzio, M., Lasky-Su, J., Chu, S.H. et al. The metabolic role of vitamin D in children’s neurodevelopment: a network study. Sci Rep 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dragomir RE, T. D., Gheoca Mutu DE, Dogaru IA, Răducu L, Tomescu LC, Moleriu LC, Bordianu A, Petre I, Stănculescu R. Consequences of Maternal Vitamin D Deficiency on Newborn Health. Life (Basel) 2024, 14 (6), 714. [CrossRef]

- Sandboge S, R. K., Lahti-Pulkkinen M et. al. Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplementation in the First 2 Years of Life on Psychiatric Symptoms at Ages 6 to 8 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2023.

- Casey CF, S. D., Neal LR. Vitamin D Supplementation in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Am Fam Physician 2010.

- M, A. Vitamin D Supplementation and Sleep: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Intervention Studies. Nutrients 2022.

- Cheng TS, L. S., Cheung YB et al. Plasma Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated With Poor Sleep Quality and Night-Time Eating at Mid-Pregnancy in Singapore Nutrients 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fallah M, A. G., Asemi Z. Is Vitamin D Status Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Quality in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Adv Biomed Res. 2020.

- Miyazaki A, T. M., Shuo T et al. Determination of optimal 25-hydroxyvitamin D cutoff values for the evaluation of restless legs syndrome among pregnant women. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023, 73–83.

- You S, M. Y., Yan B, Pei W, Wu Q, Ding C, Huang C. The promotion mechanism of prebiotics for probiotics: A review. Front Nutr 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lin C, L. Y., Zhang H et al. Intestinal ‘Infant-Type’ Bifidobacteria Mediate Immune System Development in the First 1000 Days of Life. Nutrients 2022.

- Van Rossum T, H. A., Knoll RL, et al. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Probiotics and Gut Dysbiosis in Preterm Infants: The PRIMAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2024, 985–995.

- Korpela, K., Salonen, A., Vepsäläinen, O. et al. Probiotic supplementation restores normal microbiota composition and function in antibiotic-treated and in caesarean-born infants. Microbiome 2018. [CrossRef]

- Nocerino R, D. F. F., Cecere G et al. The therapeutic efficacy of Bifidobact. The therapeutic efficacy of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BB-12® in infant colic: A randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial 2020, 110–120.

- Moreno-Villares JM, A.-P. D., Soria-López M et al. Comparative efficacy of probiotic mixture Bifidobacterium longum KABP042 plus Pediococcus pentosaceus KABP041 vs. Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM17938 in the management of infant colic: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2024, 5371–5538. [CrossRef]

- Jiang L, Z. L., Xia J, Cheng L et al. Probiotics supplementation during pregnancy or infancy on multiple food allergies and gut microbiota: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Panchal, H., Athalye-Jape, G., Rao, S. et al. Growth and neuro-developmental outcomes of probiotic supplemented preterm infants -a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2023, 85–871. [CrossRef]

- Gonia S, H. T., Miller N et. al. Maternal oral probiotic use is associated with decreased breastmilk inflammatory markers, infant fecal microbiome variation, and altered recognition memory responses in infants-a pilot observational study. Front Nutr 2024.

| Nutrients | Recommendations*/day | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy & Lactation | Year 1 | Year 2 | |||

| 270 days | 365 days | 365 days | |||

| Pregnant Women | Breastfeeding Women | Breastfeeding Infants | Complementary Feeding | ||

| Omega-3 Fatty acids | 0-6 months | 6- 12 months | |||

| DHA+EPA (mg) | 250-375^ | 250-375^ | |||

| DHA alone (mg) | 200 -300 | 200 - 300 | Not Established | ||

| Choline (mg) | 450 b, c - 550 a | 550 a, b | Not Established | 150 a, b | 200 a, b |

| Folate (mcg DFE) | 600 a, b, c | 500 b - 600a | Not Established | 80 a,b | 150a, b |

| Iodine (mcg) | 220 b, c- 290 a | 290a, b | Not Established | 130a | 90 a |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 2.6 b, c- 2.8 a | 2.8 a, b | Not Established | 0.5 a, b | 0.9 a, b |

| Iron (mg) | 27 a, b, c | 9 b-27 a | Not Established | 11 a, b | 7 a, b |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15 a,b, c | 15 a,b | 10 a,b | 10 a, b | 15 a, b |

| Key Nutrients | Role | Evidence Strength | Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes | |||

| Omega-3 Fatty acids | DHA, the dominant omega-3 fatty acid in the developing brain, is vital for neuronal membrane structure and synaptic maturation. As the body cannot produce omega-3s, sufficient intake of DHA/EPA is essential for healthy brain development. | Strong evidence from RCTs and systematic reviews; heterogeneity exists for a dose dependent outcome | Absence of standardized, mandatory guidelines for omega-3 supplementation beyond 6 months of age. |

| Choline | Choline influences stem cell proliferation and apoptosis, thereby altering brain and spinal cord structure and function and influencing risk for NTDs and memory function. | Moderate evidence from observational studies; limited RCTs in humans. | Absence of reliable biomarkers to detect choline deficiency and limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) specifically investigating the effects of choline supplementation alone on infant neurodevelopment. |

| Folate | Folate supports cell creation, DNA/RNA synthesis, and neurotransmitter formation, which are essential for the proper development of the nervous system and prevention of NTDs. | Strong evidence for folic acid in NTD prevention; limited evidence on other folate forms. | Absence of clinical studies directly linking different forms of folic acid such as 5-MTHF to NTD prevention |

| Iodine | Iodine is a necessary component of thyroid hormones, which are vital for the growth and maturation of the brain and central nervous system. | Strong evidence from population-level interventions; deficiency clearly linked to deficits. | Limited data on optimal supplementation levels in iodine-sufficient populations. |

| Vitamin B12 | Vitamin B12 supports DNA synthesis, myelination (the formation of protective nerve sheaths), and synaptogenesis (the creation of brain connections) | Moderate evidence: deficiency linked to adverse outcomes, but supplementation trials inconsistent. | Lack of long-term, well-designed studies to determine the efficacy and safety of vitamin B12 supplementation during pregnancy for both maternal health and fetal developmental outcomes - particularly on the various forms of B12. |

| Iron | Iron supports myelination, the synthesis of monoamine neurotransmitters, and provides energy for the rapidly growing brain. | Strong evidence that deficiency impairs cognition; supplementation helps but effect size varies. | Limited evidence on timing/dosing of supplementation in non-deficient populations. |

| Vitamin D | Research indicates that Vitamin D may contribute to preserving cognitive function through induction of neuroprotection, modulation of oxidative stress, regulation of calcium homeostasis, and inhibition of inflammatory processes | Emerging evidence for cognition; observational links strong. | Lack of long-term, dose dependent clinical trials focusing on neurodevelopmental outcomes. |

| Probiotics | Probiotics may support infant cognition through the gut-brain axis, particularly for preterm infants | Strong emerging evidence | Long-term trials in healthy infants |

| Sleep | |||

| Omega-3 Fatty acids | Omega-3 fatty acids have important roles in sleep regulation, with evidence suggesting that EPA and DHA influence serotonin activity and that DHA contributes to melatonin synthesis. | Emerging evidence especially in the first 1000 days | Long-term, well-designed trials for better sleep outcomes in mother-infants |

| Vitamin D | Vitamin D plays a multifaceted role in sleep, from influencing melatonin production to activating vitamin D receptors (VDRs) in brain regions that regulate the sleep–wake cycle. | Plausible mechanisms and some supportive studies. | High-quality, consistent RCT evidence showing clear, generalisable sleep improvements |

| Iron | Iron deficiency affects sleep by disrupting the brain’s ability to synthesize essential neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, which regulate mood and sleep-wake cycles. | Strong emerging evidence | High-quality, consistent RCT evidence showing clear, generalisable sleep improvements |

| Probiotics | Probiotics may improve sleep quality by regulating the gut-brain axis through the production of neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. | Strong emerging evidence | Long-term, well-designed trials for better sleep outcomes in mother-infants |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).