In recent decades, cross-cultural mobility has intensified due to globalization, migratory flows, and international education programs. Individuals navigating across cultural boundaries face challenges such as linguistic adaptation, social integration, and cultural negotiation, which often generate elevated stress levels but may also foster resilience and personal growth.

Traditional approaches to cross-cultural stress have often been reductionist, focusing narrowly on stressors or coping strategies without fully integrating the transactional dynamics of stress as a person–environment interaction (Abad, 2025). Systematic reviews of cross-cultural stress measures reveal that most instruments emphasize stressors (e.g., language barriers, discrimination, homesickness) while neglecting appraisal and coping dimensions, and rarely incorporate positive aspects such as eustress (Abad, 2023; Abad, 2025). This gap underscores the need for instruments that capture the multidimensionality of stress, including emotional responses, resilience pathways, and well-being outcomes.

The Inventário de Estresse e Resiliência na Mobilidade Cross-cultural (IERM-T) was developed to address these limitations. Grounded in Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model of stress and coping, and informed by Diener et al.’s (1985) conceptualization of well-being, the IERM-T integrates stressors, coping strategies, emotional responses, and residential well-being into a unified framework. Furthermore, recent contributions from cross-cultural psychology highlight the importance of cultural dimensions (e.g., Hofstede’s individualism–collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance) in shaping stress appraisal and coping resources (Abad et al., 2025). By situating stress within cultural contexts, the IERM-T advances beyond traditional acculturative stress measures, offering a culturally sensitive and psychometrically robust tool.

Method

Participants

The pilot validation of the IERM-T was conducted with a sample of 42 participants, complemented by approximately 107 evaluations in stressor–emotion–coping assessments. These assessments were generated whenever one or more stressors were appraised by participants as “stressing” rather than “positive” or “indifferent.” In such cases, participants were asked to evaluate the associated emotional responses and coping strategies linked to the selected stressors. The sample represented diverse cross-cultural mobility experiences, including international students, expatriates, and migrants. Demographic data such as age, gender, country of origin, and duration of residence were collected to enable subgroup analyses.

Instruments

The IERM-T was designed as a multidimensional inventory comprising five components:

Demographic Data

Stressors (22 items)

Symptoms (36 items, Likert 5-point scale)

Residential Well-Being (4 items)

Stressor–Emotion–Coping Evaluations (16 emotions + 2 coping scales).

Justification for Analytical Approach

Unlike traditional psychometric validation studies that rely on proprietary software such as SPSS or Factor, the present study employed R as the primary analytical environment. This decision was motivated by:

Transparency and reproducibility: R is open-source, allowing full documentation and replication of analyses without licensing restrictions.

Flexibility: R provides advanced packages for psychometric evaluation (e.g., psych, lavaan, boot), enabling customized analyses beyond the limitations of point-and-click interfaces.

Integration with data collection: The IERM-T was implemented via Shiny, facilitating seamless transition from online data capture to statistical analysis within the same ecosystem.

Multilingual and technical demands: The project required handling complex datasets across Portuguese, Spanish, and English, including exportation challenges with UTF-8 encoding. R offered robust solutions to these issues, which proprietary tools could not address effectively.

Thus, the use of R was not only a methodological choice but a necessity given the technical and cultural scope of the project.

Analytic Procedures

Factorial analyses were conducted separately for each component of the IERM-T to respect the multidimensional nature of the constructs. For the symptom scale, Cronbach’s alpha was estimated with bootstrapping (5,000 resamples) to provide robust confidence intervals despite the small sample size. Exploratory Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to identify latent structures, supported by item-total correlations. For the emotion scale, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) revealed two coherent factors: one clustering positive emotions (e.g., love, happiness, trust) and another grouping negative emotions (e.g., anger, fear, envy). Coping strategies were analyzed through PCA, showing distinct profiles with weak negative correlation between strategies A and B. Stressor items were examined using KR-20 reliability estimates and descriptive frequency analyses. Finally, residential well-being items were tested for internal consistency and correlated with symptom scores to explore convergent validity.

This component-based approach allowed the identification of psychometric properties within each domain while acknowledging the theoretical independence of stress, coping, emotions, and well-being. By dividing analyses across factorial structures, the study ensured that each construct was validated according to its specific measurement logic, thereby strengthening the overall reliability and validity evidence for the IERM-T.

Results

Internal Consistency and Reliability

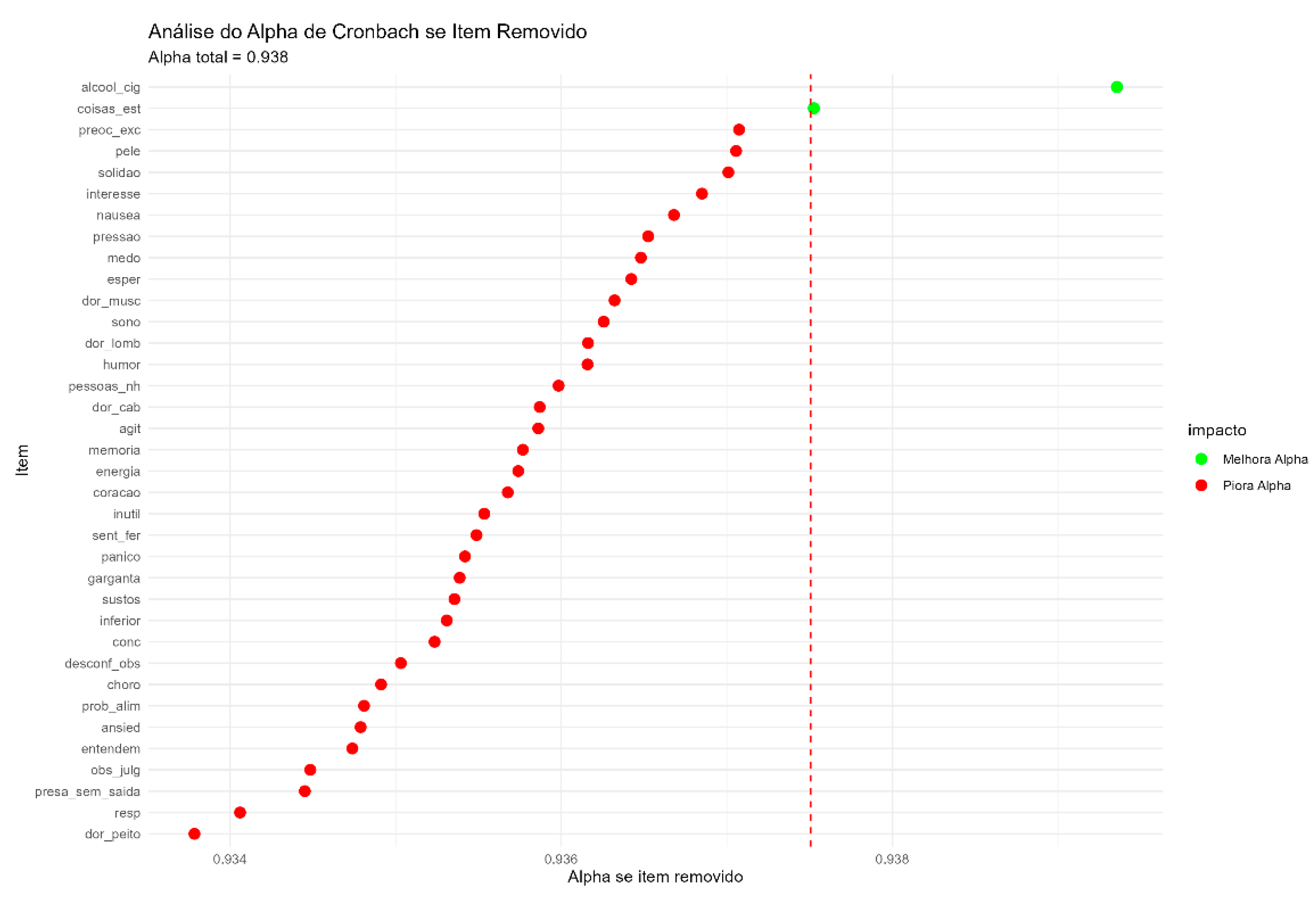

The symptom scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha = .938. Item-level analysis revealed that most items contributed positively to reliability, except “pele”, whose removal slightly improved alpha. This confirms the robustness of the symptom domain, with minimal redundancy among items.

Figure 1.

Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Removed (Image: Analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha with item-level contributions).

Figure 1.

Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Removed (Image: Analysis of Cronbach’s Alpha with item-level contributions).

Reliability and Validity

Internal consistency estimates across the IERM-T components demonstrated adequate to excellent reliability:

Stressors: α = .887

Symptoms: α = .938 (excellent)

Well-being: α = .748 (acceptable after polarity correction)

Emotions: α = .887

Coping: α = .42 (expected for a two-item scale)

These indices confirm that the IERM-T scales are psychometrically robust, with coping reliability expectedly lower due to its brevity.

Factorial Structure of Well-Being

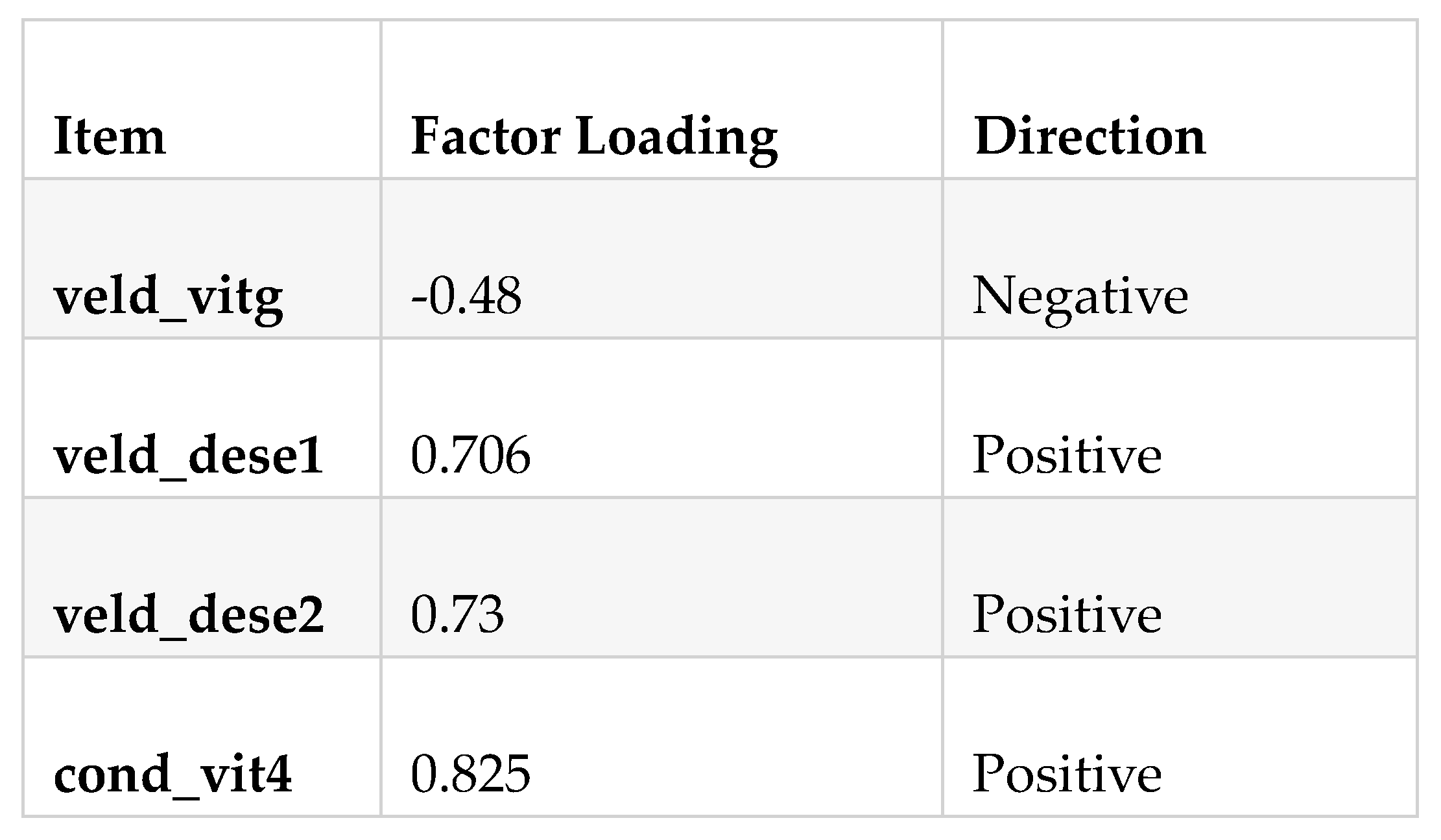

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the well-being items explained 48.5% of the variance. Factor loadings indicated strong positive contributions from cond_vit4 (.825), veld_dese2 (.730), and veld_dese1 (.706), while veld_vitg (-.48) loaded negatively.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Loadings – Well-Being IERM-T.

Figure 2.

Principal Component Loadings – Well-Being IERM-T.

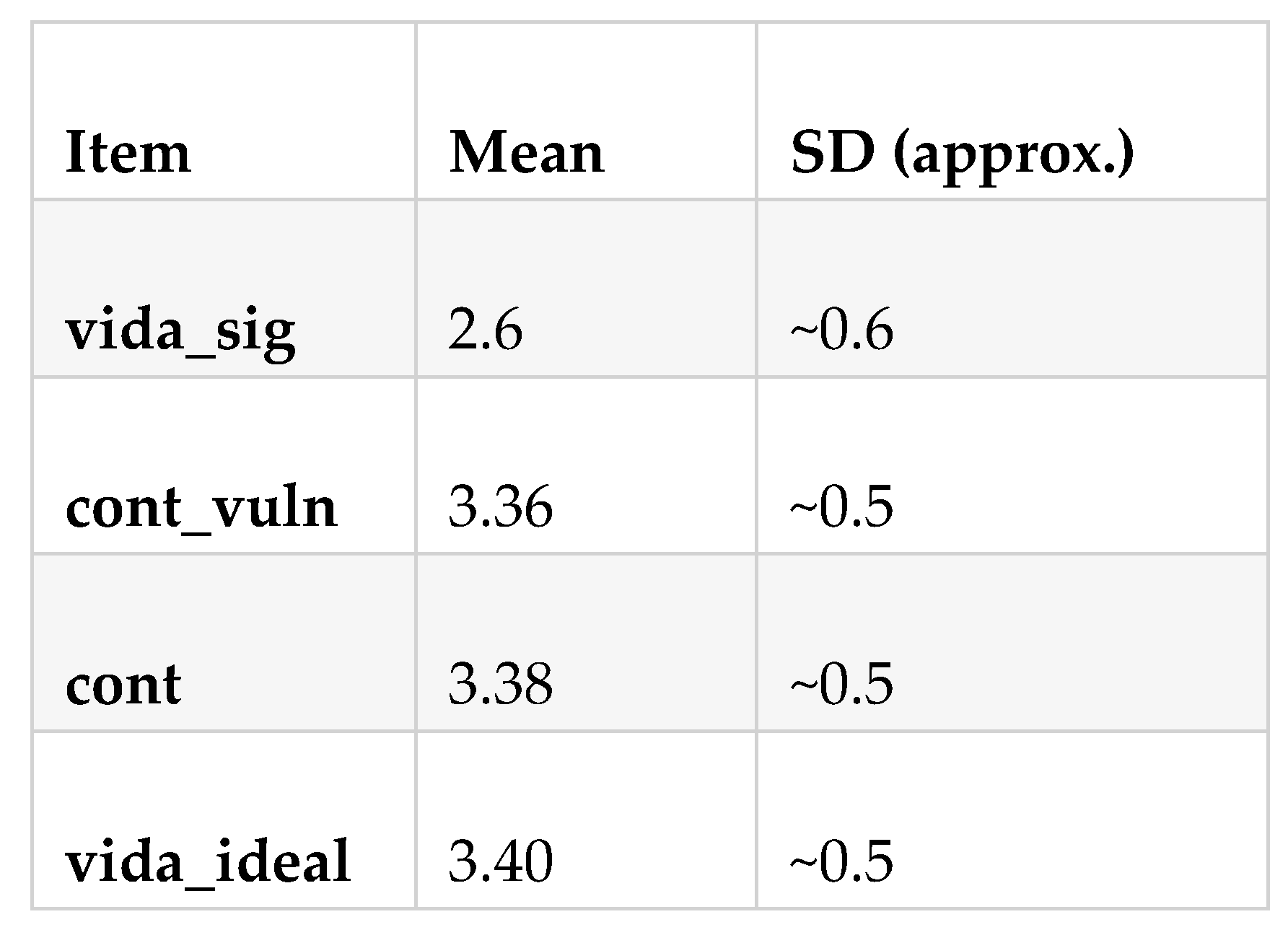

Descriptive Statistics of Well-Being Items

Mean scores for the four well-being items ranged between 2.6 and 3.4 on a 5-point scale.

Figure 3.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 3.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

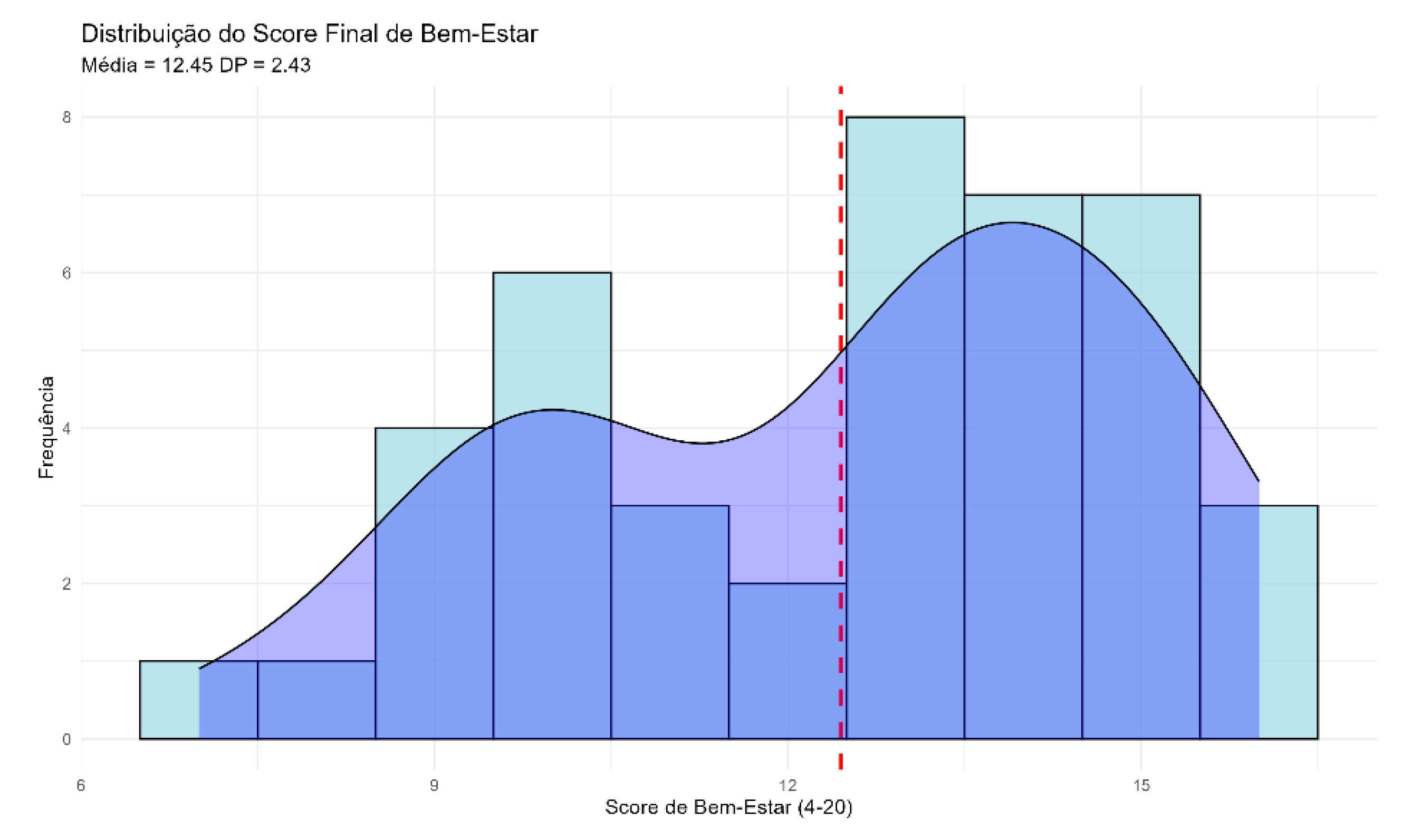

Distribution of Scores

The final well-being score distribution ranged from 4 to 20, with a mean of 12.45 (SD = 2.43).

Figure 4.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 4.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

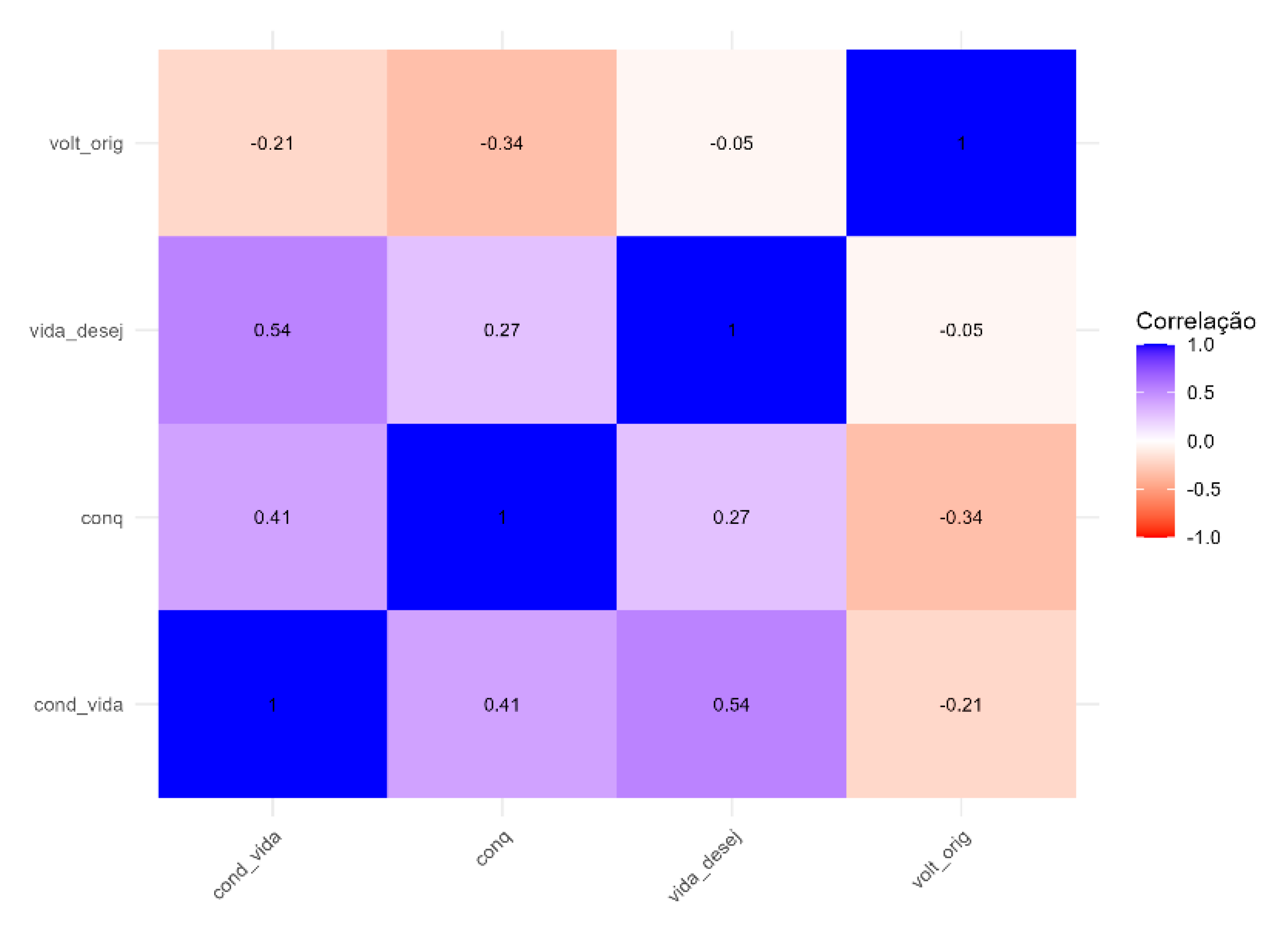

Correlation Analyses

Correlation matrices revealed meaningful associations among constructs.

Figure 5.

Correlation Matrix – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 5.

Correlation Matrix – Well-Being Scale.

Key findings:

cond_vida strongly correlated with conq (r = 1.00).

vida_desej moderately correlated with cond_vida (r = .54).

volt_orig negatively correlated with conq (r = -.34) and cond_vida (r = -.21).

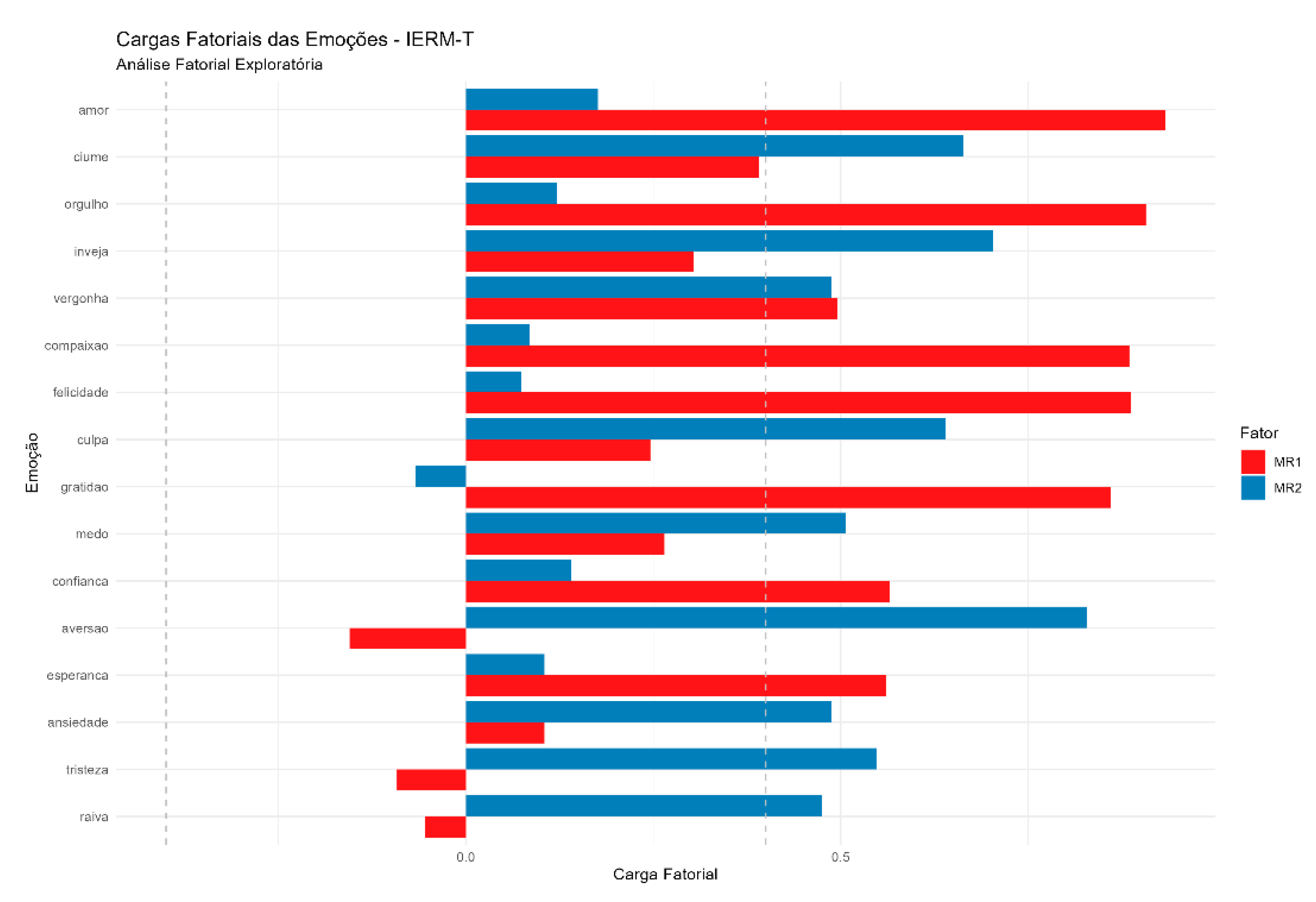

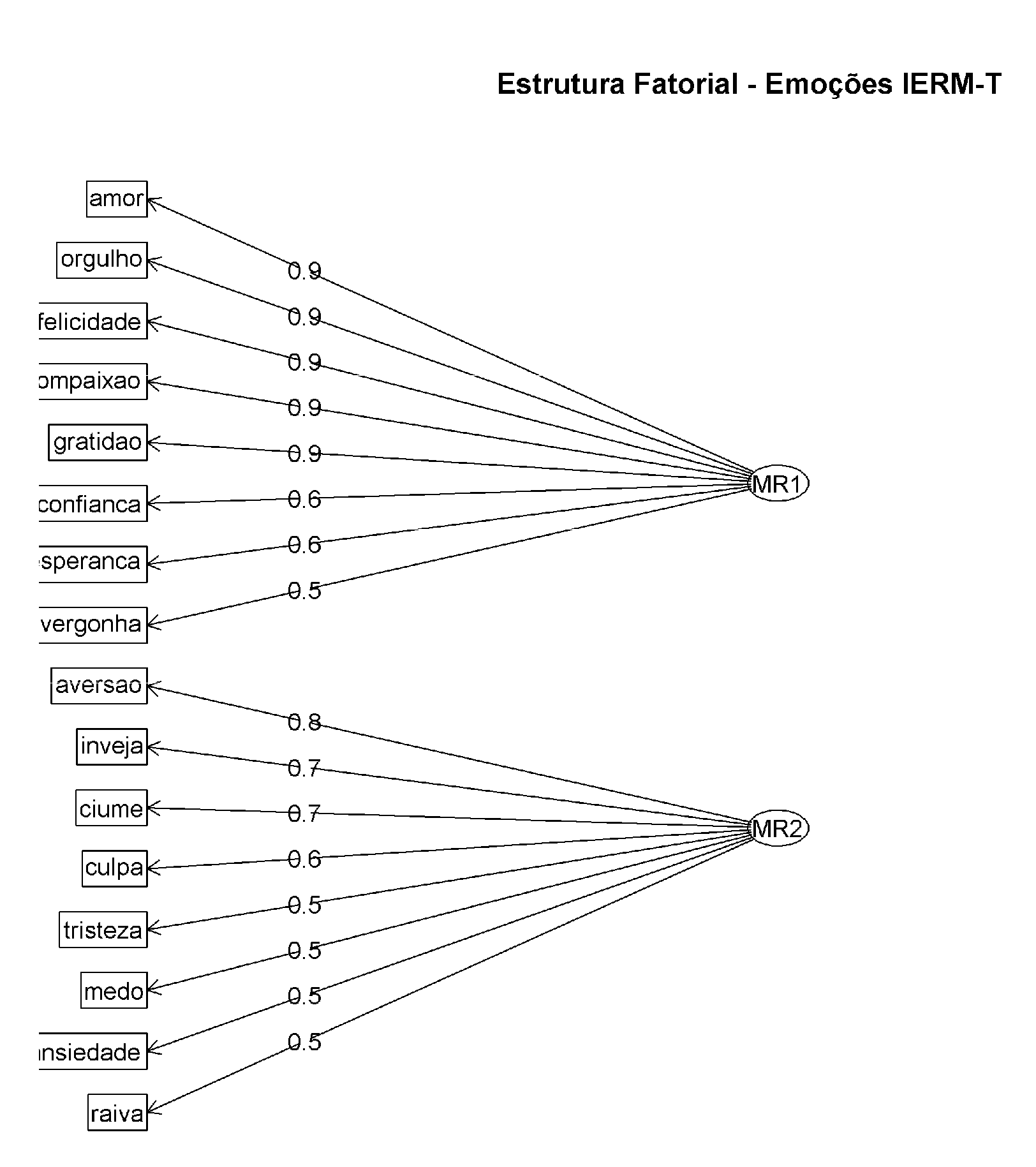

Factorial Structure of Emotions

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) revealed two coherent emotional factors.

Figure 6.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 6.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 7.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 7.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Positive emotions clustered in MR1 (loadings ~.90), negative emotions in MR2 (loadings .50–.80).

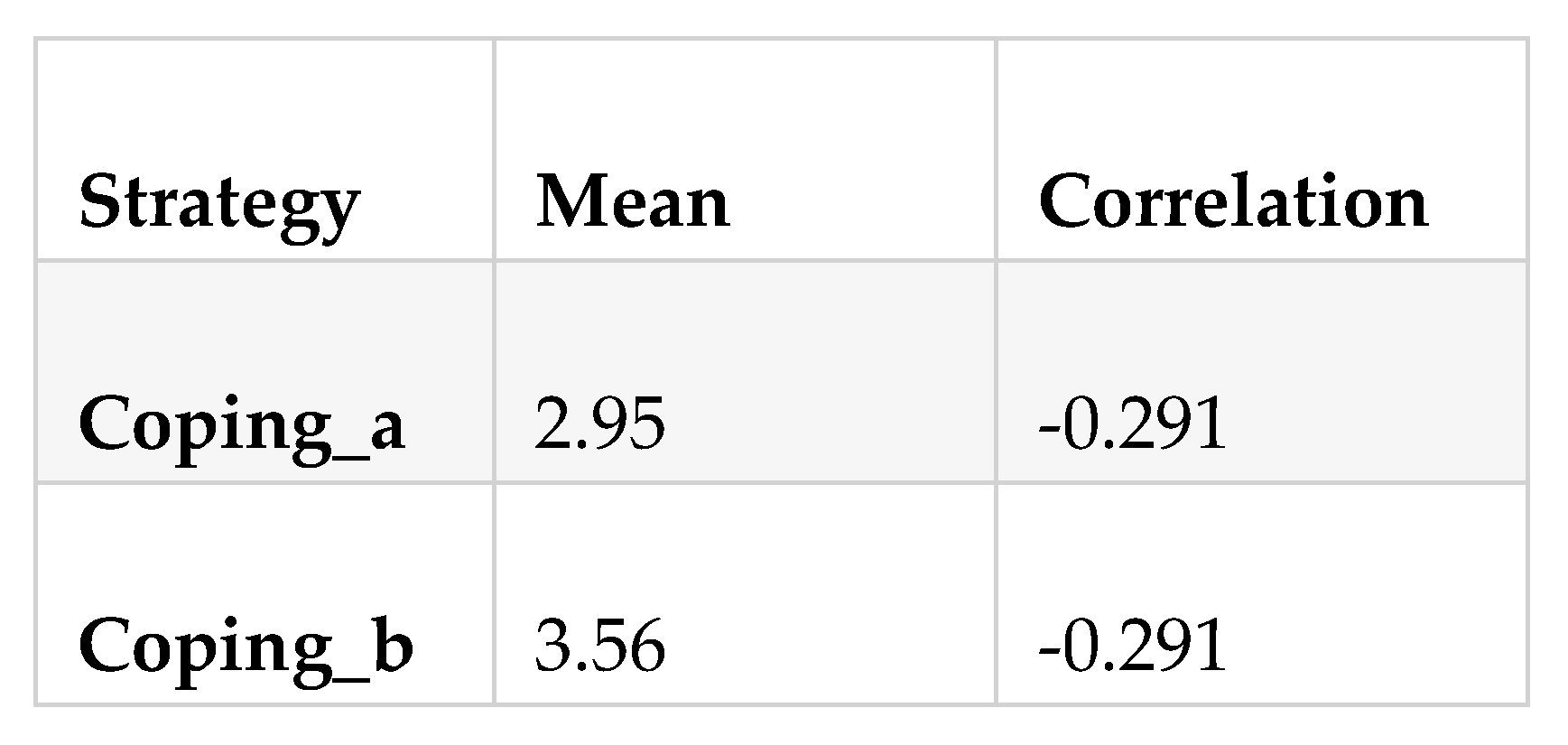

Coping Strategies

Two coping strategies were compared.

Figure 8.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Figure 8.

Descriptive Statistics – Well-Being Scale.

Symptom Frequencies

The most frequent symptoms were sleep disturbances and excessive worry.

Figure 9.

Top 10 Most Frequent Symptoms – IERM-T.

Figure 9.

Top 10 Most Frequent Symptoms – IERM-T.

Integrated Analyses

Beyond the component-level findings, integrated analyses revealed a strong negative correlation between symptom scores and resilience (r = –0.846). This relationship supports the theoretical expectation that higher symptom burden is associated with lower adaptive capacity, providing additional evidence of construct validity for the IERM-T.

Discussion

The preliminary validation of the IERM-T provides evidence that cross-cultural stress is best understood as a multidimensional construct encompassing stressors, coping, emotions, and well-being. The bifactorial structure of emotions—distinguishing resilience-oriented positive affect (e.g., love, trust, hope) from vulnerability-oriented negative affect (e.g., anger, fear, envy)—is consistent with Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) transactional model, which emphasizes appraisal processes in determining adaptive versus maladaptive outcomes.

These findings resonate with broader critiques of existing stress measures. Abad’s (2025) systematic review highlighted that most instruments rely excessively on Cronbach’s alpha, neglect measurement invariance, and fail to model stress transactions. By contrast, the IERM-T employs bootstrapping procedures, exploratory factor analysis, and component-based validation, ensuring methodological rigor even with small samples. Moreover, the integration of coping strategies revealed a weak negative correlation between coping profiles, suggesting that individuals may adopt distinct, sometimes competing, approaches to stress management—a finding aligned with the transactional model’s emphasis on coping flexibility.

Cultural dimensions further contextualize these results. As Abad et al. (2025) argue, Hofstede’s framework demonstrates how values such as collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, and power distance shape stress appraisal and coping resources. For instance, collectivist cultures may buffer stress through social support, while individualist contexts amplify pressure for autonomy. The IERM-T’s ability to capture these culturally mediated dynamics positions it as a valuable tool for both research and policy.

Clinically, these integrated results highlight the utility of the IERM-T for applied contexts. The strong inverse relationship between symptoms and resilience underscores its potential for use in health and policy settings, where identifying risk factors and protective resources is essential. The instrument can therefore serve not only as a research tool but also as a practical measure to guide interventions aimed at reducing stress and strengthening resilience among cross-cultural populations.

Finally, the IERM-T contributes to cross-cultural psychology by bridging psychometric evidence with cultural theory. It responds to the gaps identified in systematic reviews (Abad, 2023; Abad, 2025) by incorporating appraisal, coping, and resilience dimensions often neglected in prior measures. Although the sample size of 42 participants provided sufficient data for exploratory analyses, it remains modest for complex psychometric modeling. Future research should also explore policy applications, as highlighted by Abad et al. (2025), integrating psychological assessment with interventions that promote inclusion, reduce discrimination, and strengthen resilience in multicultural societies.

Conclusion

The present study introduced and validated the Inventário de Estresse e Resiliência na Mobilidade Cross-cultural (IERM-T), a multidimensional instrument designed to assess stress, coping, emotions, and well-being among individuals experiencing cross-cultural mobility. Grounded in Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional model of stress and coping, the IERM-T demonstrated strong internal consistency, coherent factorial structures, and meaningful correlations across domains. The findings highlight the inventory’s capacity to capture both vulnerability and resilience processes, offering a culturally sensitive tool for understanding psychological adaptation in diverse mobility contexts.

The contributions of the IERM-T are threefold. First, it provides a theoretically grounded and empirically supported measure that integrates stressors, coping strategies, emotional responses, and well-being into a single framework. Second, it advances methodological innovation by employing R and Shiny for both data collection and psychometric validation, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and adaptability across languages and cultural settings. Third, it offers practical relevance for cross-cultural psychology, enabling researchers and practitioners to identify risk factors and resilience pathways in populations such as international students, expatriates, migrants, and refugees.

Future research should expand the validation of the IERM-T with larger and more diverse samples, employing confirmatory factor analyses and cross-cultural invariance testing to strengthen its psychometric foundation. Longitudinal studies are recommended to examine the dynamic interplay between stress and resilience over time, particularly in contexts of prolonged mobility or forced migration. Additionally, applied research could explore the utility of the IERM-T in clinical and policy settings, informing interventions that promote resilience and mitigate stress in cross-cultural populations. By continuing to refine and expand the instrument, the IERM-T has the potential to become a cornerstone in the assessment of psychological adaptation in an increasingly globalized world.

References

- Abad, A. Cross-cultural mobility representations of academically talented Brazilians: Triggers and challenges; Trends in Psychology, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A. Cross-cultural mobility stress measures: A systematic review. Preprints 2023, 2023050425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A.; Campos, L. A. M.; Teixeira, A. L. M.; Alves, D. B.; Espósito, G.; Bomfim, J.; Silva, J. C. T.; Oliveira, T. M. A. Estresse, resiliência e políticas públicas na mobilidade cross-cultural: Como as dimensões de Hofstede orientam estratégias para a gestão de diferenças culturais. Revista Aracê 2025, 7(3), 13805–13815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, A. Neglecting stress transactions: A systematic review of psychometric and cultural gaps in cross-cultural stress scales. Preprints 2025, 2025091481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. Stress perspectives on acculturation. In The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology; Sam, D. L., Berry, J. W., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2006; pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R. A.; Larsen, R. J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 1985, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G. J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S.; Folkman, S. Stress, appraisal, and coping; Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).