Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

02 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Robustness to heterogeneity. They must detect diverse and hidden patterns that may lead to the same clinical outcome, recognising that compensatory mechanisms can produce similar disease manifestations via different pathways;

- Data efficiency. They must be capable of learning from small sample sizes, given the scarcity and cost of clinical data;

- Interpretability. They must go beyond simple classification and offer insightful, explainable reasoning, and even better the test procedure to verify the conclusion, especially for tasks such as early diagnosis and risk stratification.

2. Materials and Methods

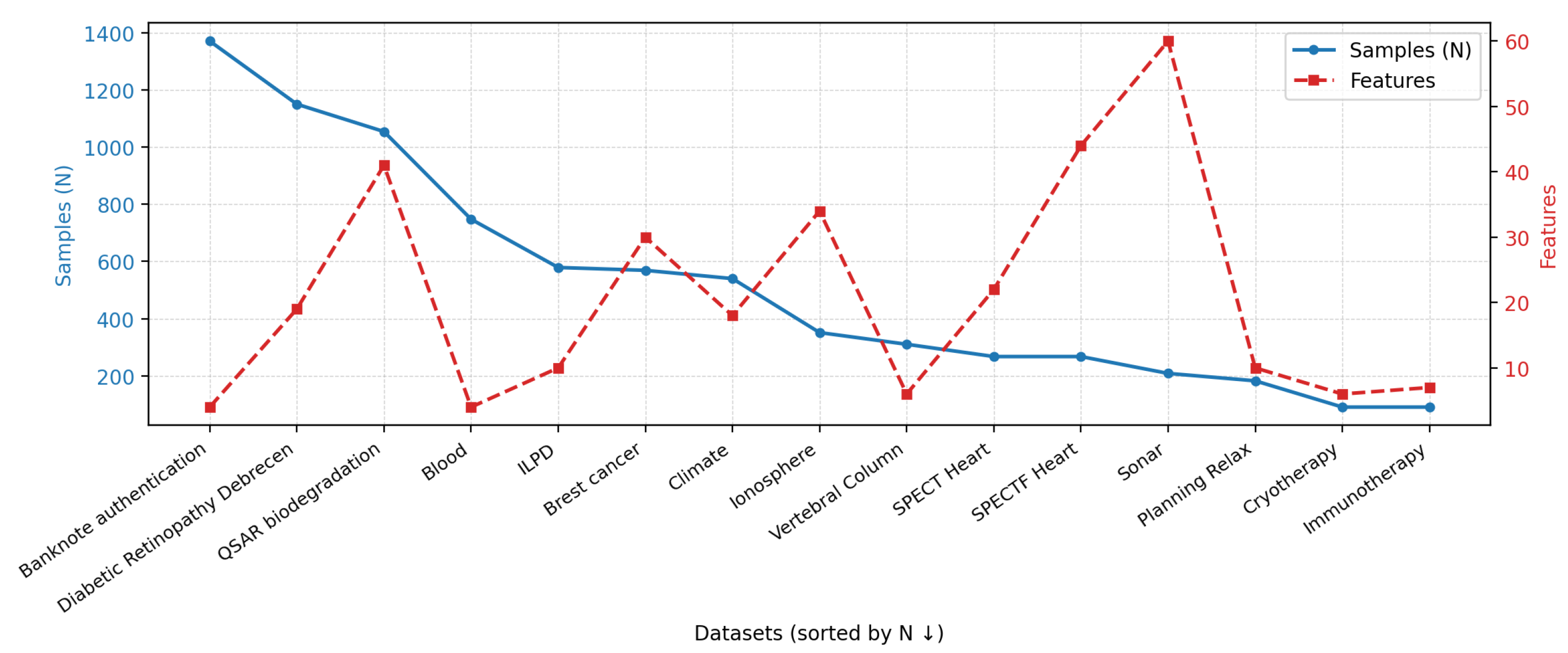

2.1. Datasets

- Binary class labels;

- No missing values;

- All features are numerical or binary;

- The number of samples exceeds the number of features.

2.2. Models

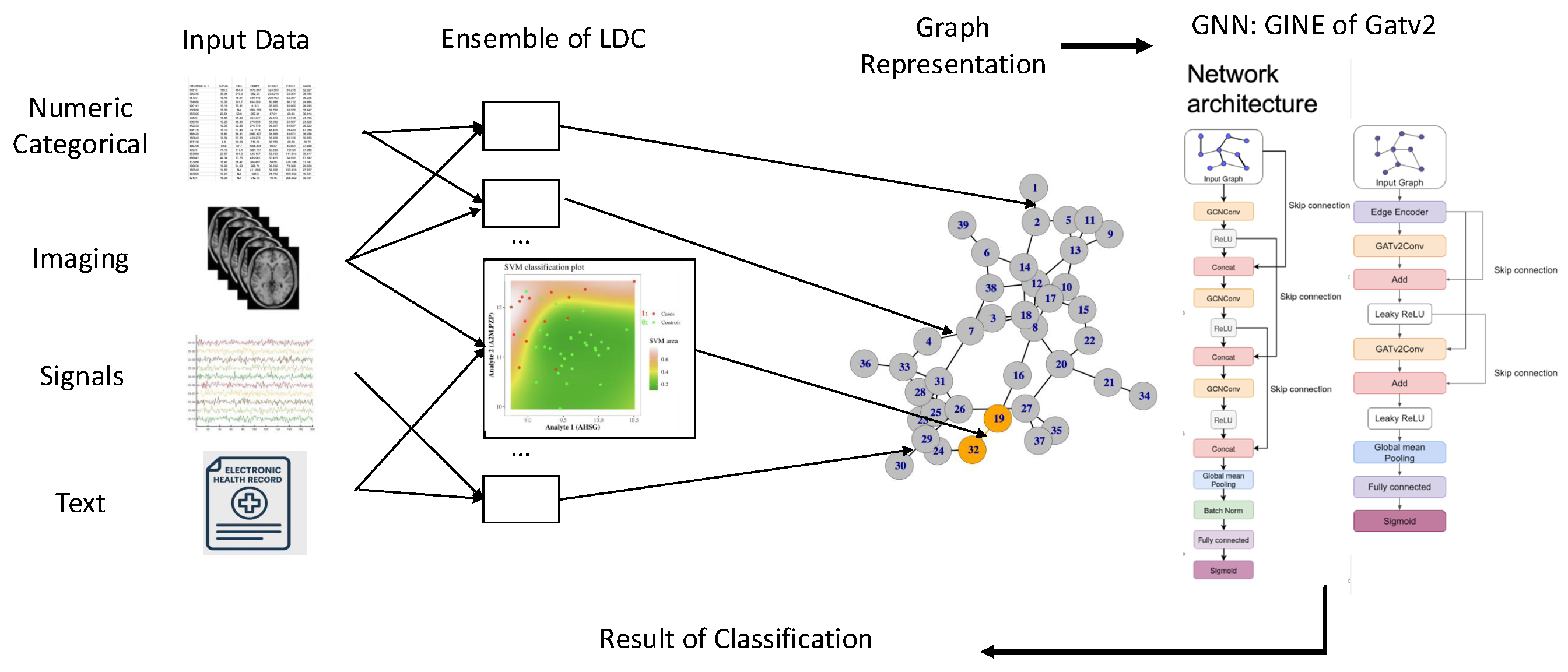

2.2.1. Pipeline Architecture

- (1)

- SGNN Graph Construction. We generate sample-specific graphs from selected tabular datasets using the SGNN methodology, which relies on ensembles of pairwise classifiers trained with class labels for each dataset and produces a unique graph structure for every data point [10].

- (2)

- GNN Training. We train two graph neural networks — GCN and GATv2 — on the resulting graphs to perform classification. For each model and each task, we use training parameters selected individually through hyperparameter optimization using the Optuna framework [22].

- (3)

- Training Strategies. We evaluate two training regimes: (i) training on the concatenation of all datasets as a form of task-agnostic pretraining or foundation model setting, and (ii) individual training on each dataset separately. Exploration of these settings allows us to examine generalization across datasets.

- (4)

- Comparison with Classical Models. We compare our graph-based approaches with a classical XGBoost classifier trained on the same datasets, to assess the relevance and added value of GNNs in this classification context.

2.2.2. Node Features

- is the original scalar feature of node i;

- is the normalized node degree, i.e., the normalised number of edges connected to this node: , where N is the number of nodes;

- is the normalized node strength: , where and is an edge weight between nodes i and j;

- is the closeness centrality of node i, calculated as the reciprocal of the sum of the length of the shortest paths between the node and all other nodes in the graph;

- is the betweenness centrality of node i computed with edge weights.

2.2.3. Graph Sparsification

- (1)

- Threshold-based sparsification: Retains a fraction p of the most significant edges based on the criterion , where is the edge weight. This approach allows control over graph sparsity while preserving connections with the greatest deviation from the neutral value 0.5.

- (2)

- Minimum connected sparsification: Employs binary search to determine the maximum threshold such that the graph remains connected. The method finds the minimal edge set that ensures graph connectivity, thereby optimizing the trade-off between sparsity and structural integrity.

- (3)

- No sparsification: Baseline configuration that preserves the original graph structure.

3. Results

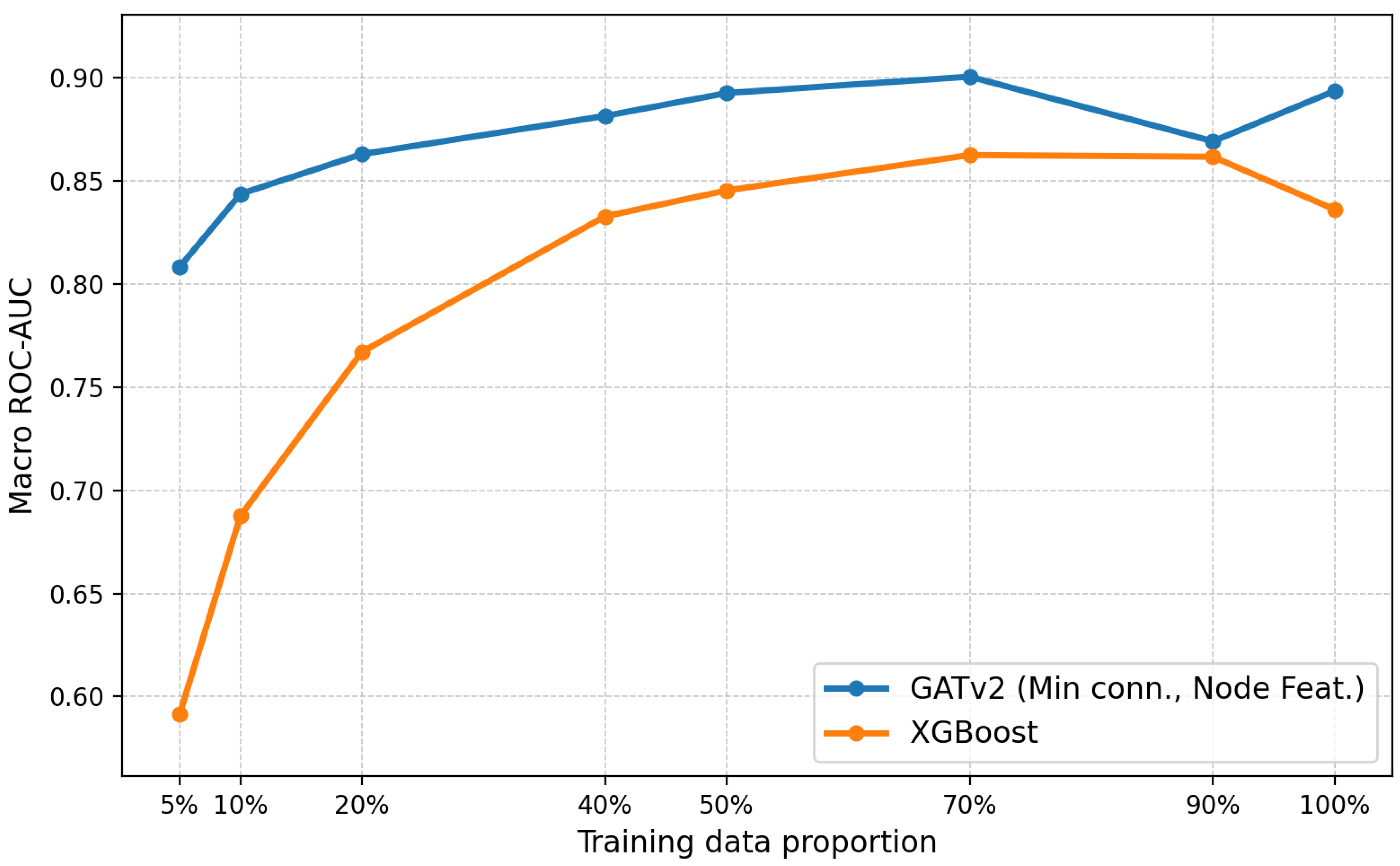

3.1. Foundation Model Task

3.2. Separate Datasets Task

3.3. Visualization of Sparsification Strategies

3.4. Testing the Universality of the Pipeline

3.5. Dealing with the Curse of Dimensionality

3.6. Robustness to Correlated Features

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. A: Language Models, 2025; arXiv:cs.CL/2402.06196].

- Villalobos, P.; Ho, A.; Sevilla, J.; Besiroglu, T.; Heim, L.; Hobbhahn, M. data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning; Salakhutdinov, R.; Kolter, Z.; Heller, K.; Weller, A.; Oliver, N.; Scarlett, J.; Berkenkamp, F., Eds. PMLR, 21–27 Jul 2024, Vol. 235, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp.

- Jones, N. The AI revolution is running out of data. What can researchers do? Nature 2024, 636, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurk, S.; Koren, S.; Rhie, A.; Rautiainen, M.; Bzikadze, A.V.; Mikheenko, A.; Vollger, M.R.; Altemose, N.; Uralsky, L.; Gershman, A.; et al. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science 2022, 376, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A focus on single-cell omics. Nat Rev Genet 2023, 24, 485. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schübeler, D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature 2015, 517, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.; Glampson, B.; Peach, R.; Barahona, M.; Delaney, B.C.; Mayer, E.K. Transformer-based deep learning model for the diagnosis of suspected lung cancer in primary care based on electronic health record data. EBioMedicine 2024, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnenführer, J.; De Bin, R.; Benner, A.; Ambrogi, F.; Lusa, L.; Boulesteix, A.L.; Migliavacca, E.; Binder, H.; Michiels, S.; Sauerbrei, W.; et al. Statistical analysis of high-dimensional biomedical data: a gentle introduction to analytical goals, common approaches and challenges. BMC Medicine 2023, 21, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berisha, V.; Krantsevich, C.; Hahn, P.R.; Hahn, S.; Dasarathy, G.; Turaga, P.; Liss, J. Digital medicine and the curse of dimensionality. npj Digital Medicine 2021, 4, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivonosov, M.; Nazarenko, T.; Ushakov, V.; Vlasenko, D.; Zakharov, D.; Chen, S.; Blyus, O.; Zaikin, A. Analysis of Multidimensional Clinical and Physiological Data with Synolitical Graph Neural Networks. Technologies 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, H.J.; Bacalini, M.G.; Blyuss, O.; Chen, S.; Garagnani, P.; Gordleeva, S.Y.; Jalan, S.; Ivanchenko, M.; Kanakov, O.; Kustikova, V.; et al. The Human Body as a Super Network: Digital Methods to Analyze the Propagation of Aging. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, M.; Alcazar, J.M.; Carbajosa, J.V.; Paez, M.G.; Papo, D.; Sousa, P.; Menasalvas, E.; Boccaletti, S. Parenclitic networks: uncovering new functions in biological data. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, M.; Papo, D.; Sousa, P.; Menasalvas, E.; Nicchi, A.; Kubik, E.; Boccaletti, S. Combining complex networks and data mining: Why and how. Physics Reports 2016, 635, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwell, H.J.; Blyuss, O.; Menon, U.; Timms, J.F.; Zaikin, A. Parenclitic networks for predicting ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 22717–22726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krivonosov, M.; Nazarenko, T.; Bacalini, M.G.; Vedunova, M.; Franceschi, C.; Zaikin, A.; Ivanchenko, M. Age-related trajectories of DNA methylation network markers: A parenclitic network approach to a family-based cohort of patients with Down Syndrome. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals 2022, 165, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Tober-Lau, P.; Lemke, O.; Nazarenko, T.; Thibeault, C.; Whitwell, H.; Röhl, A.; Freiwald, A.; Szyrwiel, L.; Ludwig, D.; et al. A time-resolved proteomic and prognostic map of COVID-19. Cell Systems 2021, 12, 780–794.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demichev, V.; Tober-Lau, P.; Nazarenko, T.; Lemke, O.; Kaur Aulakh, S.; Whitwell, H.J.; Röhl, A.; Freiwald, A.; Mittermaier, M.; Szyrwiel, L.; et al. A proteomic survival predictor for COVID-19 patients in intensive care. PLOS Digit Health 2022, 1, e0000007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. 2017; arXiv:cs.LG/1609.02907].

- Brody, S.; Alon, U.; Yahav, E. How Attentive are Graph Attention Networks? 2022; arXiv:cs.LG/2105.14491]. [Google Scholar]

- Mirkes, E.M.; Allohibi, J.; Gorban, A. Fractional Norms and Quasinorms Do Not Help to Overcome the Curse of Dimensionality. Entropy 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. 2019; arXiv:cs.LG/1907.10902].

- Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. The curse (s) of dimensionality. Nat Methods 2018, 15, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarenko, T.; Whitwell, H.J.; Blyuss, O.; Zaikin, A. Parenclitic and Synolytic Networks Revisited. Frontiers in Genetics, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNN Model Parameters | |||

| Activation function | Leaky ReLU | Hidden layer size | 128 |

| Number of GNN layers | 2 | Dropout rate | 0.3 |

| Residual connections | True | Use edge encoder | True |

| Edge encoder hidden size | 32 | Number of edge encoder layers | 2 |

| Classifier MLP hidden size | 32 | Number of classifier MLP layers | 2 |

| GATv2 Specific Parameters | |||

| Number of attention heads | 3 | Concatenate head outputs | True |

| Training Configuration | |||

| Learning rate | Batch size | 512 | |

| Maximum epochs | 256 | Early stopping patience | 128 |

| Learning rate patience | 32 | Cross-validation folds | 3 |

| Weight decay | LR reduction factor | 0.5 | |

| Optuna Hyperparameter Optimization | |||

| Number of trials | 8 | Startup trials | 1 |

| Warmup steps | 4 | ||

| XGBoost Baseline Configuration | |||

| Maximum depth | 6 | Learning rate | 0.1 |

| Number of estimators | 100 | Subsample ratio | 0.8 |

| Column sampling ratio | 0.8 | ||

| Model | Sparsify | ROC-AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Feat. = False | Node Feat. = True | ||

| GCN | None | 85.65 | 92.34 |

| p=0.2 | 86.55 | 90.58 | |

| p=0.8 | 85.36 | 90.83 | |

| Min conn. | 85.63 | 91.04 | |

| GATv2 | None | 90.80 | 92.83 |

| p=0.2 | 91.01 | 91.22 | |

| p=0.8 | 90.47 | 92.39 | |

| Min conn. | 90.25 | 91.28 | |

| XGBoost | None | 90.80 | |

| Model | Sparsify | Macro ROC-AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Feat. = False | Node Feat. = True | ||

| GCN | None | 84.91 | 87.77 |

| p=0.2 | 80.49 | 83.11 | |

| p=0.8 | 79.06 | 81.84 | |

| Min conn. | 82.43 | 86.17 | |

| GATv2 | None | 86.37 | 88.35 |

| p=0.2 | 87.23 | 86.33 | |

| p=0.8 | 87.20 | 88.68 | |

| Min conn. | 85.80 | 88.96 | |

| XGBoost | None | 86.84 | |

| Fully connected graph | Top 20% most significant edges | Max threshold preserving connectivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label = True |  |

|

|

| Label = False |  |

|

|

| Configuration | ROC-AUC |

|---|---|

| Synolitic graph only | 70.34 |

| Sparsified at maximum threshold while remaining connected | 71.07 |

| With additional node features | 78.39 |

| Model | Sparsify | Macro ROC-AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Feat. = False | Node Feat. = True | ||

| GCN | None | 84.91 / 77.40 | 87.77 / 84.01 |

| p=0.2 | 80.49 / 78.53 | 83.11 / 83.02 | |

| p=0.8 | 79.06 / 80.70 | 81.84 / 86.73 | |

| Min conn. | 82.43 / 83.41 | 86.17 / 85.57 | |

| GATv2 | None | 86.37 / 87.36 | 88.35 / 87.93 |

| p=0.2 | 87.23 / 85.60 | 86.33 / 88.44 | |

| p=0.8 | 87.20 / 81.71 | 88.68 / 87.38 | |

| Min conn. | 85.80 / 82.74 | 88.96 / 88.82 | |

| XGBoost | None | 86.84 / 85.90 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).