1. Introduction

The Ketogenic Diet (KD) is a low-carbohydrate diet that includes a normal amount of protein to meet physiological needs, with fats and the ketones synthesized during their metabolism serving as the main source of energy. This leads to a series of metabolic, biochemical, and hormonal changes in the body that resemble those occurring during prolonged fasting. These changes affect a number of pathological processes and diseases, which is why the KD is increasingly used in clinical practice. Some researchers refer to it as a metabolism-based therapy [

1].

The KD was introduced into clinical practice for the treatment of epilepsy more than 100 years ago by Dr. Wilder at the Mayo Clinic [

2]. In recent decades, various forms of this diet have been adopted in an increasing number of medical fields. There is a growing number of publications reporting successful treatment not only of a wide range of neurological diseases, but also positive outcomes in patients with endocrine, oncological, psychiatric, and other conditions and disorders [

3,

4,

5,

6].

The pathophysiological mechanisms through which KD affects all these different diseases are not fully understood. It is known that KD influences brain metabolism and neurotransmitters [

7,

8,

9], improves cellular and mitochondrial biogenesis [

10], reduces oxidative stress, and induces anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and epigenetic effects [

11,

12]. More recent studies highlight the significance of its effect on the gut microbiome [

13].

Undoubtedly, the hormonal effects of KD are among the important mechanisms underlying its impact, especially in endocrine diseases and disorders such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes [

14,

15,

16]. Studies of KD in patients with obesity typically demonstrate a reduction in insulin levels [

17,

18,

19]. This is considered an important mechanism explaining the beneficial effects of the diet in diseases associated with insulin resistance. There are relatively fewer studies examining the effects of KD on thyroid hormones, cortisol, and others. Some studies in children with epilepsy who follow a strict long-term KD have found that hypothyroidism may develop in some cases and recommend monitoring thyroid hormones in such patients [

20,

21]. Reports of beneficial effects of KD in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are also intriguing—this is a hormonal disorder that affects adolescent girls and is associated with fertility issues, psycho-emotional problems, increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and reduced quality of life [

22,

23,

24].

One of the goals of our study on the effects of KD in children with obesity was to evaluate the diet’s influence on various hormonal levels in patients, as this could contribute to a more detailed understanding of the complex mechanisms through which this dietary approach affects a wide range of health disorders.

2. Results

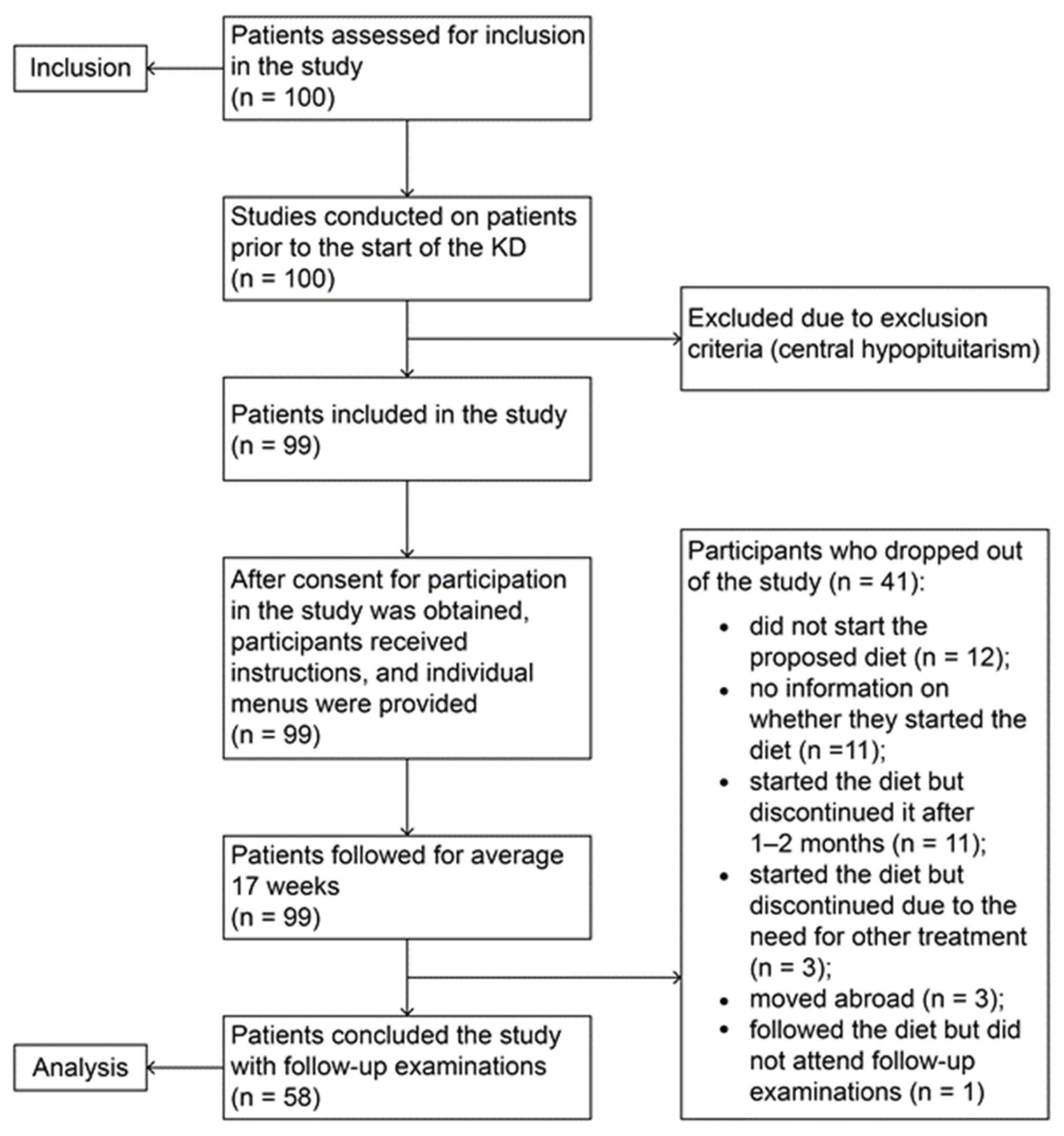

Fifty-eight obese children aged 8 to 18 years who followed a “Well-Formulated Ketogenic Diet” were monitored for a period of four months. Before starting and upon completing the diet, multiple anthropometric, biochemical, endocrine, and ultrasound parameters related to obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome were assessed.

2.1. Insulin and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

Baseline evaluation of the patients prior to initiation of the KD demonstrated elevated mean fasting insulin levels (mean value 20.12 μIU/ml). All patients exhibited postprandial hyperinsulinemia during the OGTT. Hyperinsulinemia was defined as a more than fivefold increase from baseline insulin levels or values exceeding 100 μIU/ml.

Follow-up assessments after completion of the dietary intervention revealed a statistically significant reduction in fasting insulin levels (p<0.0001) (

Table 1). In some of the children with good or moderate compliance to the diet, insulin levels reached normal values (<10 μIU/ml) or values close to the accepted pediatric reference range. Sex-specific analysis demonstrated a significantly greater decrease in baseline insulin levels in girls compared with boys (p=0.02) (Supplementary Data –

Table S1). Patients with good or moderate dietary compliance exhibited significantly lower fasting insulin levels following the intervention (Supplementary Data –

Table S3).

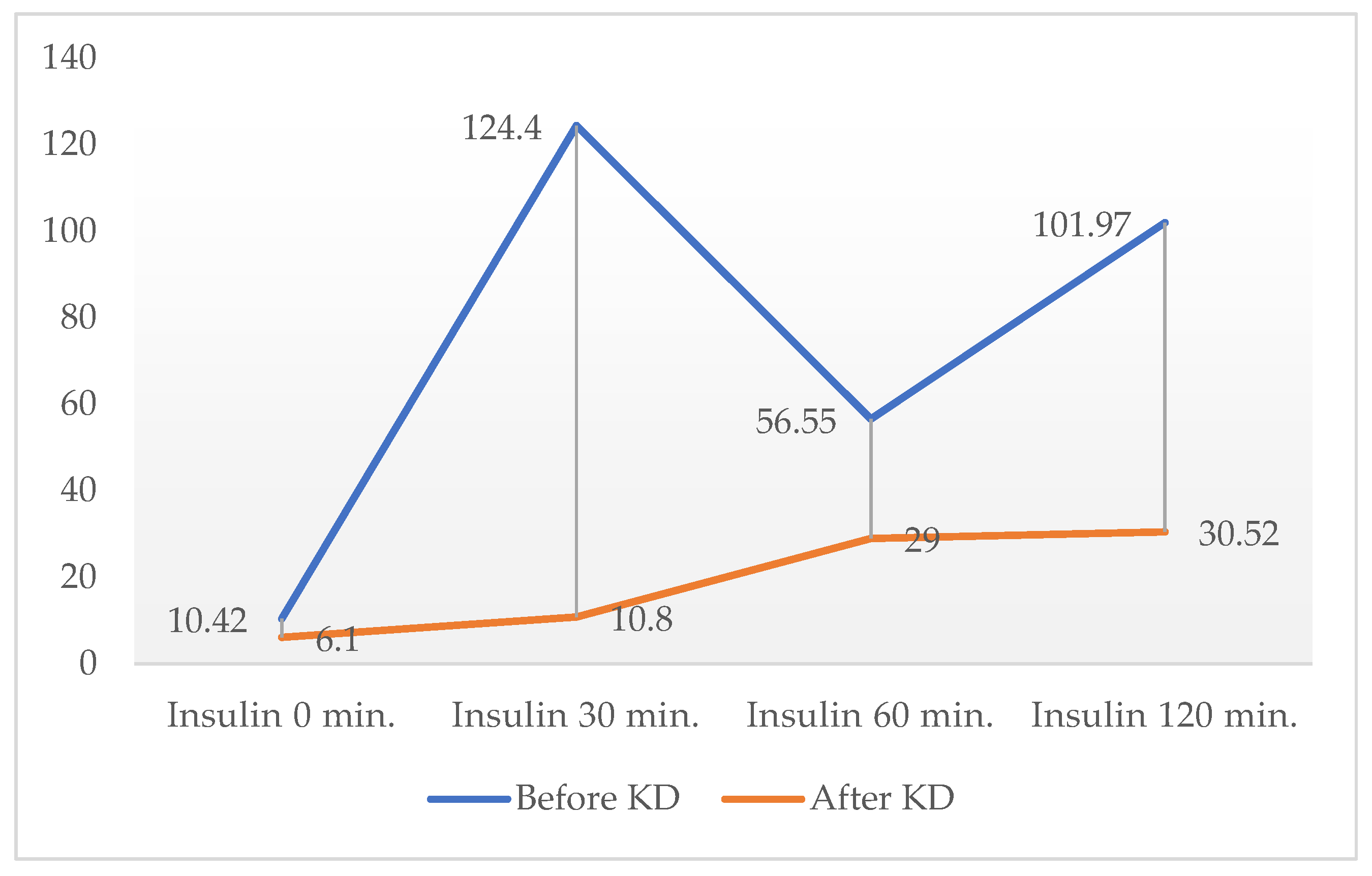

At the end of the dietary period, OGTT was performed only in one female patient with normal fasting insulinemia in order to assess changes in postprandial insulin secretion; her results are presented in

Figure 1.

2.2.. TSH and Thyroid Hormones

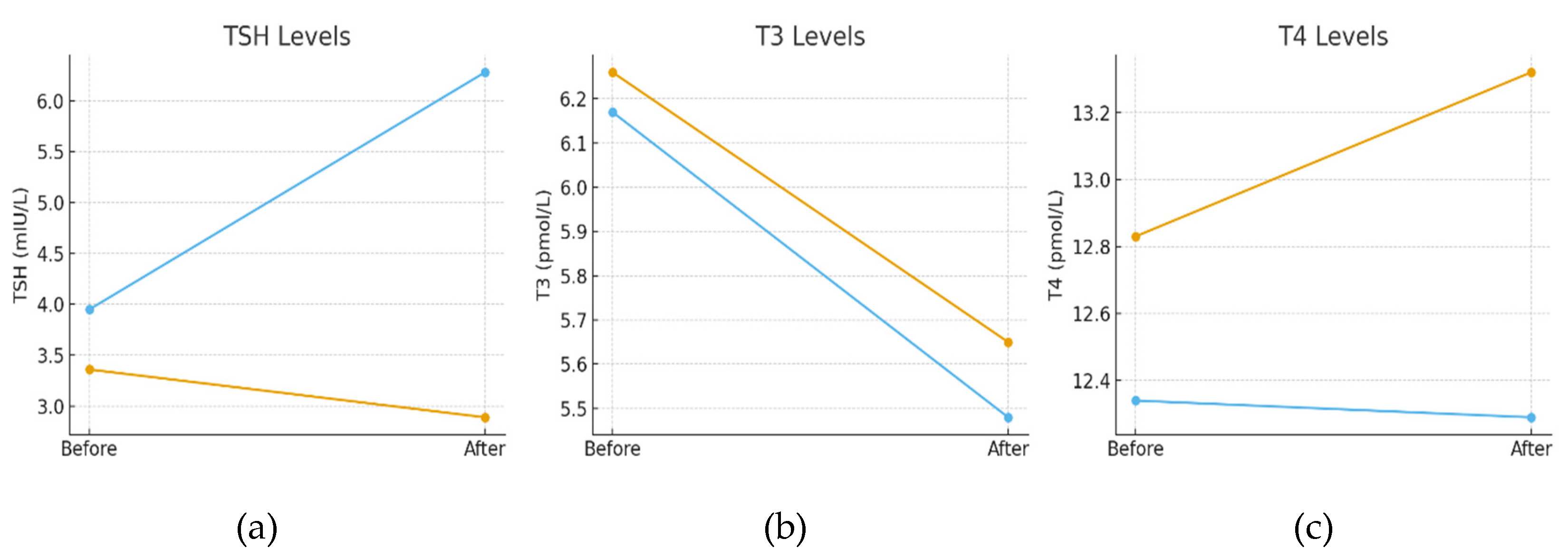

TSH, thyroid hormones T3 and T4, as well as antibodies specific to autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies), were measured in all patients before the start and after the completion of the diet.

Seven of the patients were diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. All of them were euthyroid at baseline (two were receiving L-thyroxine substitution therapy at a dose of 25 μg). Following the KD intervention, a significant reduction in mean serum fT3 levels was observed in the entire cohort (p<0.0001) (

Table 1), which was more pronounced among female patients, though independent of age (Supplementary Data –

Tables S4 and S5). Concurrently, a slight but significant increase in mean fT4 concentration was recorded (p=0.05) (

Table 1), without differences by sex, age groups or dietary compliance (Supplementary Data –

Tables S7, S8 and S9) No significant changes were found in TSH levels (p=0.13) (

Table 1), either in the whole group or when stratified by sex, age, or dietary compliance (Supplementary Data –

Tables S10, S11 and S12).

At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences in mean TSH, fT3, or fT4 levels between patients with and without autoimmune thyroiditis. By the end of the intervention, however, a significant difference in mean TSH was noted: patients without thyroiditis demonstrated a significant decrease in TSH, whereas those with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis exhibited significantly increased TSH values, with mean levels exceeding the reference range. No significant between-group differences were observed in fT3 or fT4 concentrations (

Figure 2 and Supplementary Data –

Tables S13 and S14).

2.3. Patients with PCOS

Eight girls aged 15–17 years met the diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome (according to the Rotterdam consensus) at baseline. All presented with prolonged secondary amenorrhea (> 6 months) and required progesterone treatment to induce withdrawal bleeding. None of these patients received hormonal therapy for menstrual regulation during the dietary intervention. All eight girls experienced spontaneous menstrual bleeding within 1–2 months after initiation of the diet, and in some, regular menstrual cycles were established by the end of follow-up. Their individual outcomes are presented in

Table 2.

Testosterone was measured in all female patients with clinical signs of pubertal development (n=17). A statistically significant reduction in mean testosterone levels was observed after completion of the KD intervention (

Table 1).

2.4. Cortisol

The mean morning cortisol level for the entire cohort also demonstrated a statistically significant decrease at the end of the intervention (p=0.04) (

Table 1). Analysis of variance revealed no significant differences when stratified by sex, age or dietary compliance (Supplementary Data –

Tables S15, S16 and S17).

2.5. Adiponectin

Application of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed a significant increase in mean adiponectin levels following the KD intervention (p=0.04) (

Table 1). No sex-related differences were observed in mean adiponectin concentrations before and after the intervention (p>0.05) (Supplementary Data –

Table S18). However, age-stratified analysis demonstrated significant differences: mean adiponectin levels were highest in the youngest group (8–10 years) and lowest in the oldest group (15–18 years), both at baseline and after completion of the diet (Supplementary Data –

Table S19).

Further analysis based on patients’ dietary compliance revealed statistically significant differences in post-intervention adiponectin levels. Specifically, participants demonstrating good or moderate adherence to the ketogenic diet exhibited markedly higher mean adiponectin concentrations at the end of the intervention compared with those with poor compliance, suggesting a dose–response relationship between dietary compliance and the improvement in insulin sensitivity markers (Supplementary Data –

Table S20).

3. Discussion

In this article, we present the results of the hormonal assessments of the patients from our study, which aimed to investigate the clinical, metabolic, and endocrine effects of a “Well-Formulated Ketogenic Diet” in children with obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome. The results regarding the diet’s effect on weight reduction and its impact on symptoms and markers of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome were presented in our previous article [

25]. At the end of the dietary intervention, we observed not only a statistically significant reduction in all anthropometric indicators related to obesity, but also improved insulin sensitivity and a reversal of metabolic syndrome.

Most studies examining the effect of the ketogenic diet in patients with obesity and metabolic disorders demonstrate its effectiveness in reducing body weight, insulin resistance-related markers, and features of metabolic syndrome. Comparatively fewer studies have investigated changes in the levels of other hormones (thyroid hormones, cortisol, adiponectin), which also play a role in the pathogenic processes of obesity. This provided us with the rationale to explore more thoroughly the hormonal changes that occurred as a result of the 4-month ketogenic diet in our patients.

3.1. Ketogenic Diet and Insulinemia

Insulin is an anabolic hormone with a central role in metabolic regulation. One of its primary actions is to promote the storage of energy rather than its utilization. The obesogenic effect of insulin has long been recognized, with documented cases of insulin therapy being applied to non-diabetic patients for the purpose of increasing body weight [

26]. Even a modest elevation in fasting insulinemia has been shown to markedly suppress lipolysis and stimulate lipogenesis, without significantly inhibiting gluconeogenesis—effects that ultimately favor adipogenesis [

26]. Epidemiological studies in children and adolescents link elevated basal insulin (and the concomitant insulin resistance) to greater weight gain later in life [

27]. Chronic hyperinsulinemia is not only a determinant in the pathogenesis of obesity but also plays a pivotal role in the development of metabolic syndrome, hepatic steatosis, primary hypertension, and PCOS. Moreover, the associated insulin resistance represents a major contributor to the elevated risk of coronary heart disease and chronic cardiovascular disorders [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

By definition, the KD is characterized by very low intake of digestible carbohydrates, while not requiring excessively high protein consumption. Given that glucose and certain amino acids are the nutrients most potently stimulating insulin secretion [

33,

34], the reduction in fasting insulinemia observed in our patients was expected. By drastically reducing carbohydrate intake, the KD minimizes postprandial glucose excursions, which directly reduces the stimulus for pancreatic insulin secretion. This carbohydrate restriction shifts hepatic metabolism away from de novo lipogenesis and toward increased fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis, resulting in decreased hepatic fat accumulation and improved hepatic insulin sensitivity [

35,

36,

37]. Specifically, the ketogenic diet reduces hepatic diacylglycerol content and protein kinase C-ε activity, both of which are implicated in the development of hepatic insulin resistance [

35]. A probable role is also played by ketone bodies, such as β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB), produced during ketosis, which have a direct insulin-sensitizing effect in peripheral tissues. In skeletal muscle, βHB alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress and upregulates the AKT/GSK3β pathway, increasing GLUT4 translocation and glucose uptake, thereby improving insulin sensitivity and reducing circulating insulin requirements [

38,

39]. The ketogenic diet also suppresses inflammatory signaling (e.g., TNFα, NF-κB, IL-6) and oxidative stress, both of which contribute to insulin resistance. It promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and efficiency, further enhancing insulin sensitivity [

35,

40,

41]. Finally, the ketogenic diet modulates adipose tissue hormones, such as increasing FGF21 and promoting browning of white adipose tissue, which supports improved metabolic stability and insulin sensitivity [

41]. It is likely that collectively, these mechanisms result in lower insulin levels by reducing the need for insulin secretion and improving tissue responsiveness to insulin.

In our study, fasting insulin levels were significantly reduced across all age groups, including in the youngest patients (8–10 years), whose baseline insulin levels prior to dietary intervention were within the physiological range. A more pronounced reduction in fasting insulin was observed among children demonstrating better dietary compliance. Notably, the greater compliance recorded among girls likely contributed to the larger decrease in fasting insulinemia within this subgroup.

Repeat OGTT was not incorporated into the follow-up protocol. This test requires several days of prior carbohydrate loading, which was unsuitable for some children who continued the diet for extended periods in order to normalize weight, metabolic, and hormonal imbalances. Consequently, we were unable to systematically evaluate postprandial hyperinsulinemia after the 4-month intervention.

In only one patient, a second OGTT was performed following KD, which revealed a dramatic reduction in postprandial insulin levels (comparative results shown in

Figure 1). This observation suggests that, in patients with normal or near-normal baseline insulin, post-challenge insulinemia may serve as a more sensitive indicator of the effects of KD on insulin secretion.

Similar findings regarding the impact of KD on insulin levels in obesity have been reported by other authors. Partsalaki et al. compared KD with a low-fat hypocaloric diet in obese children and, after 6 months, demonstrated a significant reduction in fasting insulinemia in both dietary groups [

19]. Paoli et al. reported a marked decrease in fasting insulin after 12 weeks of KD in young women with obesity and PCOS [

42]. Volek et al. observed reductions in fasting insulin and improved insulin resistance in obese women after only 4 weeks of KD, further proposing that lowered insulin levels may contribute to appetite regulation [

17]. The clinical relevance of reduced insulin levels in the context of weight loss and improvement of metabolic disturbances in low-carbohydrate diets has also been emphasized by Staverosky et al., who suggested that diminished insulin secretion itself is a key factor underlying the improvements in markers commonly associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome [

18].

In light of these findings, we consider the reduction in basal insulinemia observed in our study to be of paramount importance—not only for weight reduction in our patients, but also as a fundamental mechanism underpinning the observed improvements in insulin sensitivity, normalization of blood pressure in a large proportion of cases, reversal of metabolic syndrome, and the beneficial changes in girls with PCOS.

3.2. Ketogenic Diet and Thyroid Function

The ketogenic diet induces profound changes in energy metabolism, shifting from an anabolic insulin-dominant state to a catabolic glucagon-dominant state. This is accompanied by a transition in the primary energy source, with predominant utilization of fats and ketones. These processes are associated with metabolic adaptation and hormonal changes that resemble those observed during fasting [

21,

43]. It is well established that fasting affects the hypothalamic–pituitary–thyroid axis, suppressing anabolic activity and reducing the conversion of T4 to T3 [

44]. On the other hand, thyroid dysfunction is relatively common among obese patients [

45,

46,

47], raising the important question of how KD influences thyroid hormones. To our knowledge, no studies have examined the effects of KD on thyroid hormones in children with obesity. The few available studies in patients with epilepsy undergoing KD highlight the necessity of monitoring thyroid hormones during such dietary interventions [

20,

21,

48].

In our patients, changes in mean TSH and thyroid hormone levels included a significant decrease in T3 (P < 0.0001), a borderline significant increase in T4 (p = 0.05), and stable TSH levels. These findings are consistent with the observations of other authors investigating the impact of KD on thyroid function.

In a relatively short-term study (12 weeks) of adult patients with epilepsy without prior thyroid disease undergoing a modified Atkins diet, Molteberg et al. reported a significant decrease in T3 and increase in T4, together with a nonsignificant rise in TSH and rT3. The authors suggested that KD more likely affects peripheral conversion of T4 to T3 rather than central regulatory mechanisms, and recommended monitoring of thyroid hormones during KD treatment [

48]. A crossover study in 11 healthy volunteers investigated the effects of two isocaloric diets (KD and a low-fat diet) on thyroid hormones. Each diet was followed for 3 weeks. A significant decrease in T3 and increase in T4 were observed only after KD, leading the authors to hypothesize that KD induces metabolic changes warranting further investigation [

49]. In a 12-month study of children with epilepsy on a strict KD, Yılmaz et al. found no changes in TSH levels at the end of follow-up. At the same time, a significant increase in T4 was observed, including among patients with hypothyroidism receiving replacement therapy prior to KD initiation [

21].

In our study, the observed changes in T3 and T4 are likely related to adaptive processes in overall metabolism during KD, substantial weight reduction, and alterations in peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. The hypothesis of altered deiodinase activity requires dedicated investigation, including assessment of rT3, to confirm these mechanisms.

Of note are the findings of Kose et al., who followed 120 children with refractory epilepsy on strict KD for 12 months. Subclinical hypothyroidism was detected in 20 children (16.7%), leading to initiation of replacement therapy. Most of these cases occurred in children with baseline TSH > 5 μIU/mL. The authors identified higher baseline TSH and female sex as independent risk factors for hypothyroidism during KD and recommended thyroid function monitoring [

20].

In our cohort, patients without preexisting thyroid disease remained euthyroid after 4 months of KD. However, in some patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a significant increase in TSH was detected at the end of the diet, necessitating adjustments in replacement therapy. Since autoimmune thyroiditis is a progressive disease with inevitable development of hypothyroidism, it cannot be conclusively determined that KD was responsible for the deterioration of thyroid function. A limitation of our study is the relatively small sample of patients with confirmed autoimmune thyroid disease in whom elevated TSH was recorded. Thus, coincidental activation of the autoimmune process cannot be excluded. This process is particularly susceptible to fluctuations in the pediatric and adolescent age groups. It is also conceivable that the adaptive metabolic changes induced by KD, requiring adjustments in thyroid hormone secretion and peripheral conversion, may contribute to an inadequate hormonal response in patients with preexisting thyroid disease.

Our findings, together with those of other authors, support the safety of KD in patients without preexisting thyroid disease, but they underscore the need for clinical and hormonal monitoring, especially in individuals with established conditions such as hypothyroidism and autoimmune Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

3.3. KD and PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder among women of reproductive age. In addition to obesity, a large proportion of patients present with symptoms of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, or type 2 diabetes mellitus [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Epidemiological studies indicate a marked increase in the prevalence of PCOS over the past three decades among adolescents and young women aged 10–24 years [

54], a trend that parallels the global obesity epidemic. Due to the limited effectiveness of pharmacological treatments, the identification of suitable and effective lifestyle and nutritional interventions is of particular importance for these patients.

In our study, the eight girls with PCOS demonstrated good to excellent compliance with KD, likely because they perceived it not only as a means of weight loss but also as a therapeutic option for managing their menstrual disturbances. All patients showed significant weight reduction and improved insulin sensitivity, and most exhibited markedly lower testosterone levels. After prolonged amenorrhea and minimal response to hormonal treatment, the appearance of spontaneous menstrual cycles within 1–2 months of initiating KD was a clear therapeutic success.

The etiology of PCOS is not fully understood, but chronic hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance are considered to play a central role in its pathogenesis. Elevated insulin levels stimulate androgen production in the ovarian theca cells and inhibit hepatic synthesis of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), resulting in increased transport of free androgens to target tissues [

55].

The mechanisms by which the KD may improve PCOS are multifactorial and involve several interrelated metabolic and endocrine pathways. Reduced carbohydrate intake, lower circulating insulin levels and improved insulin sensitivity are critical in PCOS, where hyperinsulinemia drives ovarian androgen production and disrupts folliculogenesis. Multiple studies in both humans and animal models demonstrate that KD reduces fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, and improves glycemic control in PCOS [

42,

56,

57,

58,

59]. By lowering insulin, the KD indirectly decreases ovarian androgen synthesis. Clinical and preclinical data show reductions in total and free testosterone, DHEAS, and the LH/FSH ratio, with concurrent increases in SHBG, further reducing bioavailable androgens [

56,

60]. The anti-inflammatory effects of KD are well known. The principal ketone body, βHB, exerts anti-inflammatory actions by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and attenuating NF-κB signaling. This reduces ovarian and systemic inflammation, which is implicated in the pathogenesis of PCOS [

61,

62]. KD also restores the balance between apoptosis and proliferation in ovarian tissue, reducing follicular atresia and improving ovulatory function, as shown in animal models [

62,

63]. KD modifies the gut microbiome composition and associated metabolites, which can influence androgen metabolism and systemic inflammation, further contributing to hormonal regulation in PCOS [

61,

64]. Weight loss and adipose tissue reduction induced by KD are likely to reduce peripheral aromatization of androgens to estrogens and restoration of normal gonadotropin secretion and ovarian function with improvement of the metabolic and reproductive outcomes [

42,

58].

Collectively, these mechanisms converge to improve metabolic, endocrine, and reproductive parameters in PCOS, with evidence supporting both direct effects of ketosis and indirect effects via weight loss and improved insulin sensitivity.

Following women with PCOS on KD with gradual carbohydrate reintroduction, Rossetti et al. found that the beneficial effects of the diet were independent of weight loss, being also present in normal-weight patients. They suggested that nutritional ketosis itself may contribute to the observed positive outcomes [

22].

In our study the restoration and regulation of menstrual cycles also occurred in most patients before substantial weight loss had been achieved, suggesting that the effect of KD cannot be attributed solely to weight reduction. It is more likely that strict carbohydrate restriction, leading to shift in the whole metabolism, reduced insulin levels, improved insulin sensitivity and anti-inflammatory properties of the KD play a key role in the beneficial effects of KD in women with PCOS.

3.4. KD and Cortisol

Cortisol is a hormone that plays an important role in obesity, insulin resistance, and metabolic disturbances. Chronically elevated cortisol levels are thought to influence appetite and eating behavior, increase systemic insulin resistance, and thus contribute to many of the abnormalities associated with metabolic syndrome — such as visceral obesity, impaired glucose tolerance, dyslipidemia, and others [

65,

66,

67]. According to some authors, chronic hyperinsulinemia leads to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in “functional hypercortisolism,” which in turn contributes to the development of visceral obesity and insulin resistance [

65].

Chronic calorie restriction or fasting diets usually result in increased cortisol levels. However, studies by Nakamura et al. suggest that very low-calorie diets do not significantly alter cortisol secretion [

68]. Polito et al. examined the effect of a calorie-restricted KD (700–900 kcal/day) in 30 obese men over an 8-week period. The authors reported a significant reduction in morning cortisol levels after the intervention and hypothesized that this may contribute to the beneficial effects of KD in obese patients [

69]. In a study involving a small group of obese men, Stimson et al. compared the effects of KD with those of a balanced diet over 4 weeks. Both interventions resulted in significant weight loss, but only KD altered cortisol metabolism through mechanisms independent of weight loss. [

70].

In our patients, we observed a reduction in morning serum cortisol levels, consistent with the findings reported by other authors noted above, although the diet followed was not strictly very low-calorie. Given the well-established relationship between changes in cortisol levels and alterations in body weight, body composition, and metabolic disturbances, it is likely that the observed cortisol reduction in our cohort is related to the mechanisms that led to improvements in anthropometric and metabolic parameters.

Possible mechanisms by which the ketogenic diet may lower cortisol levels are through modulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, reducing visceral adiposity, and exerting anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects.

First, the ketogenic diet leads to significant reductions in visceral adipose tissue, which is a source of increased local cortisol regeneration via 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1). Decreasing visceral fat reduces this local cortisol production, thereby lowering systemic cortisol levels. [

69,

70] Additionally, weight loss and improved metabolic parameters associated with the ketogenic diet can attenuate HPA axis activation, as observed by reductions in salivary cortisol after very low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) interventions in obese individuals [

69]. Кetone bodies such as βHB, produced during ketosis, have direct anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome and histone deacetylases, which may reduce chronic low-grade inflammation and oxidative stress—both of which are known to stimulate the HPA axis and cortisol secretion. [

71,

72] This anti-inflammatory action may contribute to a lower baseline cortisol output. The ketogenic diet can indirectly modulate cortisol metabolism through improved insulin sensitivity and glycemic control. Improved insulin sensitivity reduces the compensatory activation of the HPA axis that occurs in states of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. [

73,

74] The ketogenic diet may influence neuroendocrine signaling, including reductions in sympathetic nervous system activity, which is closely linked to HPA axis tone and cortisol secretion [

41]. Evidence indicates that KD reduces the expression of the hypothalamic genes for proopiomelanocortin (POMC), which, together with lower insulin levels, may contribute to decreased cortisol secretion [

75].

In summary, the ketogenic diet can low cortisol levels via reduction of visceral adiposity, anti-inflammatory effects of ketone bodies, improved insulin sensitivity, and modulation of neuroendocrine pathways, as supported by recent clinical and mechanistic studies. [

41,

69,

71,

72,

73]

3.5. KD and Adiponectin

Visceral adipose tissue is particularly active in releasing adipokines and hormones involved in a wide range of metabolic and inflammatory processes. Among them, adiponectin plays a central role, accounting for approximately 0.1% of serum proteins. Since its discovery in 1995, adiponectin has been the focus of numerous studies consistently demonstrating its role in the pathogenesis of obesity, diabetes, systemic inflammation, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, and other conditions [

76,

77].

The biological functions of adiponectin are diverse. One of its most important physiological effects is the regulation of insulin sensitivity in muscle cells by modulating lipid metabolism (via AMPK, p38MAPK, and PPARα pathways), improving glucose metabolism (through effects on the GLUT4 receptor), and enhancing fatty acid oxidation [

78]. Adiponectin inhibits the secretion of leptin and several pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby exerting anti-inflammatory effects. It also improves endothelial cell function by enhancing COX-2 and eNOS activity, leading to increased nitric oxide synthesis [

79]. Several studies have found associations between serum adiponectin levels and reproductive health, including disorders such as PCOS, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and endometriosis [

80]. Moreover, adiponectin is known to raise HDL-C levels and lower triglycerides by enhancing the catabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins [

81,

82,

83]. Thus, higher circulating adiponectin levels are considered protective against the development of atherosclerosis [

81]. Adiponectin also plays a significant role in appetite regulation and energy balance [

77,

84].

In a 2005 consensus statement, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) recommended measuring adiponectin and leptin levels as biomarkers of adipose tissue in order to improve the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome [

85].

In our study, a 4-month KD led to a modest but statistically significant increase in mean adiponectin levels (P=0.04), which we consider a marker of improved insulin sensitivity in our patients. This effect of KD was particularly pronounced when outcomes were analyzed by dietary compliance. In the group of children with good adherence to KD, greater reductions in body weight, BMI, and improvements in many clinical and laboratory parameters were accompanied by significantly higher adiponectin levels. No significant differences were observed by sex. The youngest patients showed higher adiponectin levels both before and after the intervention compared to older children, likely reflecting greater insulin sensitivity during pre-pubertal or early pubertal development.

Although few in number, studies have consistently found that KD leads to increased adiponectin levels - results similar to our observations [

19,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90].

The clinical significance of increased adiponectin levels in the context of improved insulin sensitivity and reversal of metabolic syndrome in our patients raises intriguing questions about the underlying mechanisms by which KD may stimulate adiponectin secretion.

It is well established that dietary macronutrient composition influences adiponectin levels [

91]. A 6-week study in healthy individuals found that a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet resulted in lower adiponectin levels compared to an iso-caloric higher-fat, lower-carbohydrate diet [

92]. Other studies demonstrate that the intake of simple sugars, such as glucose and fructose—whose overconsumption is linked to metabolic syndrome—is associated with lower serum adiponectin [

93,

94]. Diets with severe caloric restriction can also increase adiponectin levels [

95], but some authors suggest that this requires energy intake ≤50% of daily requirements [

96].

Interestingly, KD studies often report increased adiponectin despite not strictly restricting caloric intake, in line with the recommendations of our intervention. Furthermore, patients with epilepsy, who are frequently of normal or even low body weight, still show increased adiponectin levels while maintaining adequate caloric intake. Possible explanations include elevated βHB levels characteristic of KD, which activate the GPR109A receptor, thereby stimulating adiponectin synthesis [

97,

98]. Another mechanism may involve reduced activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by circulating βHB, resulting in lower chronic systemic inflammation, which is known to inhibit adiponectin secretion [

99]. Other authors highlight the role of free fatty acids, which, via PPARα activation, suppress cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, both inhibitors of adiponectin secretion in adipocytes [

100]. Improved mitochondrial function and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production during KD may also play a role [

97].

Regardless of the precise mechanisms, we believe that the KD-induced increase in adiponectin levels is likely an important contributor to the improved insulin sensitivity observed in our patients at the end of the dietary intervention.

Limitations and Issues of Concern

We acknowledge that a limitation of our study is the relatively short duration of the dietary intervention, which prevents us from confidently stating whether the hormonal changes we observed would be maintained over a longer period of time. Another limitation is the relatively small number of children with autoimmune thyroiditis, which means the change in TSH levels may be random rather than diet-induced. The number of girls with PCOS was also relatively small, yet the improvement in their clinical condition and the occurrence of spontaneous menstruation after a long period of secondary amenorrhea in all of them was an undeniable positive effect of the dietary intervention. The considerable differences in age and pubertal development among the patients complicate the interpretation of the hormonal changes, which is why all parameters were analyzed according to sex, age group, and dietary compliance (the results are shown in

Supplementary Materials).

4. Materials and Methods

The materials and methods used were described in detail in our first article on the effect of the diet on the children’s anthropometric measurements and indicators of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and impaired metabolic health [

25].

We present them briefly here as well.

4.1. Participants Selection and Study Design

One hundred children aged 7 to 18 years were selected to participate in the study. They were admitted for investigations at the Department of Pediatrics of University Hospital “St. George”, Plovdiv between 2021 - 2023. Inclusion criteria were - presence of obesity (according to WHO criteria - BMI ≥ 2SD from the mean for gender and age) and at least one criterion for impaired metabolic health: abdominal obesity, impaired fasting blood glucose, primary arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperinsulinemia, hyperuricemia, hepatic steatosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome. Exclusion criteria were proven adrenal gland dysfunction, pituitary pathology, congenital metabolic disease, treatment with medication causing insulin resistance, or contraindication for KD: familial (genetic) hypercholesterolemia, nephro- or cholelithiasis, history of pancreatitis.

Ninety-nine children were included in the study (1 patient was excluded due to exclusion criteria). After signing informed consent, patients underwent initial anthropometric, clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound examinations. All received detailed instructions on how to follow the diet. The patients were monitored over a period of 4 months, with families submitting weekly dietary reports electronically. Compliance with the diet was additionally monitored by measuring the level of βHB at home using provided Care Sens Dual biosensor systems. During the follow-up period, 41 patients dropped out of the study. A total of 58 children who successfully completed the study after 4 months underwent second clinical, laboratory, and ultrasound examinations to assess the effect of dietary intervention (

Figure 3)

The only recommended medications during the diet treatment were antihypertensive drugs for children with severe arterial hypertension at pediatric cardiologist’s discretion, and L-thyroxine for patients with hypothyroidism. None of the patients took insulin sensitizers during the intervention. Girls diagnosed with polycystic ovarian syndrome did not receive hormonal therapy.

4.2. Characteristics of the Group of 58 Patients Who Completed the Study

In the interpretation of the results, it was taken into consideration that the 58 patients who completed the study represented a heterogeneous cohort, including both sexes, various stages of pubertal development, and differing levels of adherence to the prescribed dietary regimen—factors that were assumed to potentially affect the study outcomes. Therefore, patients were stratified according to sex, age, and dietary compliance, and all evaluated parameters were subsequently reanalyzed within these subgroups.

The 58 patients who completed the study with follow-up assessments ranged in age from to 18 years (mean 13.79 ± 0.34) at the start of the diet, including 35 (60.34%) boys and 23 (39.66%) girls. They were distributed into three age groups: 8 (13.79%) children in the age range 8–10 years, 25 (43.10%) children 11–15 years old, and 25 (43.10%) 16–18 years old. According to the compliance with the diet, the patients were divided into 3 groups –patients with good compliance, who followed the diet strictly - 26 (44.83%), patients with moderate compliance, who followed the diet with some deviations -15 (25.86%), and patients with poor compliance, who did not follow the recommendations given to them- 17 (29.31%).

4.3. Ketogenic Diet

The proposed diet is a “Well-formulated ketogenic diet “, in accordance with the guidelines of S. Phinney and J. Volek [

101], with the following composition, structure, and recommendations:

Carbohydrate intake: up to 40 g per day, divided into 10–13 g per meal.

Protein intake: 1–1.5 g per kilogram of ideal body weight per day.

Fat intake: enough to induce satiety without excessive consumption.

Three to four meals per day: breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a small afternoon snack if hungry.

Calorie counting is not necessary. Patients should eat until satisfied while adhering to the guidelines given in the individual menu. Skipping a meal is permissible if not hungry, but prolonged and intentional starvation is not recommended.

Preference for natural foods: meat, fish, full-fat dairy products, eggs, low-carbohydrate vegetables, and a small number of low-carb fruits.

Avoidance of processed, packaged foods, soft drinks, sweetened juices, and liquids.

Fluid intake without sugar: 30–40 mL per kilogram per day

4.4. Clinical Investigations

The focus of the clinical examination was on the following:

Skin and its appendages (acanthosis nigricans, striae, acne, and the presence of in- creased hair in androgen-dependent areas in pubertal girls).

Distribution of increased adipose tissue in different parts of the body.

Cardiovascular system: measurement of heart rate and rhythm by auscultation; measurement of blood pressure with an age-appropriate sphygmomanometer under standard conditions.

4.5. Laboratory Investigations

Oral glucose tolerance test with measurement of blood glucose and insulin at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min.

Complete blood count, glycated hemoglobin, analyzed on an automated hematological analyzer Advita 2120, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics INC., Erlangen, Germany.

Biochemical parameters: Lipid profile (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides), transaminases (ALT, AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), urea, creatinine, uric acid, analyzed using original turbidimetric and immunoturbidimetric programs on a biochemical analyzer AU 480, Olympus; Beckman Coulter, Inc., Co Clare, Ireland.

Hormones: Insulin, thyroid hormones (TSH, T3, T4), cortisol, testosterone, LH, FSH, analyzed using chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) on an automated immunochemical analyzer Access 2, Beckman Coulter, Inc., Ireland.

Adiponectin level was measured using the BioVendor Human Adiponectin ELISA test.

In 17 girls with advanced pubertal development, prior to starting the diet, the LH/FSH ratio and testosterone levels were measured (on days 3–5 of the menstrual cycle), and a detailed history was taken regarding family predisposition and menstrual cycle characteristics in order to identify those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) in accordance with the assumption of normality, categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages. To compare the differences in repeated measurements after the KD was applied, we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed data and the paired t-test for normally distributed data. To assess the normality of the data distribution, we used the Shapiro–Wilk test. For categorical variables, we performed Mann–Whitney U tests to examine differences in diet compliance.

In the context of statistical analysis, values assigned to p-values р ≤ 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. The effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for significant findings to evaluate the magnitude of the observed differences.

The robustness of the findings was subjected to further assessment through the execution of sensitivity analyses, which involved the exclusion of outliers. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.23 (Armonk, NY, USA).

5. Conclusions

A relatively short-term (4-month) “well-formulated ketogenic diet” in children with obesity induces hormonal adaptations that promote weight reduction and improve insulin sensitivity, as evidenced by decreased basal insulinemia, lower cortisol levels, and elevated adiponectin concentrations. Notably, the diet demonstrated particularly favorable effects in girls with polycystic ovary syndrome, resulting in the restoration of natural menstrual cycles. These findings suggest that the KD may represent an important component of a comprehensive therapeutic strategy in such cases.

Participants without pre-existing thyroid disorders remained euthyroid at the end of the intervention. The observed alterations in thyroid hormone levels—specifically, a reduction in triiodothyronine (T3) and a slight increase in thyroxine (T4)—are likely attributable to adaptive metabolic responses associated with the predominant utilization of fats as the main energy substrate during ketosis.

Given the high prevalence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis among individuals with obesity and metabolic syndrome, it is essential to assess thyroid function and autoimmune thyroid markers prior to the initiation of a KD. Moreover, close monitoring of thyroid function and autoimmune activity during dietary intervention is recommended to enable timely adjustment or initiation of hormone replacement therapy when clinically indicated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org. Table S1: Fasting insulin before and after the KD by gender. Table S2: Fasting insulin before and after the KD by age. Table S3: Fasting insulin after the KD according to compliance with the diet. Table S4: Т3 before and after the KD by gender. Table S5: Т3 before and after the KD by age. Table S6: Т3 after the KD according to the compliance with the diet. Table S7: T4 before and after the KD by gender. Table S8: T4 before and after the KD by age. Table S9: Т4 after the diet according to the compliance with the diet. Table S10: TSH before and after the KD by age. Table S11: TSH before and after the KD by age. Table S12: TSH after the diet according to the compliance with the diet. Table S13. TSH and thyroid hormones in patients with and without Hashimoto’s thyroiditis before the KD. Table S14. TSH and thyroid hormones in patients with and without Hashimoto’s thyroiditis after the KD. Table S15: Cortisol before and after the KD by gender. Table S16: Cortisol before and after the KD by age. Table S17: Cortisol after the diet according to the compliance with the diet. Table S18: Adiponectin before and after the KD by gender. Table S19: Adiponectin before and after the KD by age. Table S20: Adiponectin after the KD according to the compliance with the diet.

Author Contributions

I.N.P. and I.S.I. conceived and designed research and acquired funding; T.D.D. analyzed data and interpreted results; N.N.K. selected most of the patients for inclusion in the study and interpreted results; I.N.P. prepared tables and figures and drafted the manuscript; I.S.I. approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria, University project №07/2021, ref.№ P-2395/ 2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria (protocol code 2/9 March 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and their parents.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all the patients and their families participating in the study, to the doctors who referred their patients for inclusion in the study, and to the doctors and nurses at the Pediatric Clinic of University Hospital “St. George”—Plovdiv, Bulgaria, for their help in conducting all the investigations. This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diet in children with obesity” which was presented at the 5th Congress of the Pediatric Association of the Balkan, Istanbul 2–4 November 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| KD |

Ketogenic diet |

| PCOS |

Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| OGTT |

Oral glucose tolerance test |

| (βHB) |

β-hydroxybutyrate |

| HPA axis |

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| SHBG |

Sex hormone-binding globulin |

References

- Kossoff, E.H.; Turner, Z.R.; Cervenka, M.C.; Barron, B.J. Ketogenic diet therapies for epilepsy and other conditions, 7th ed.; Publisher: Springer Publishing Company, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wheless JW. History of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia. 2008;49 Suppl 8:3-5. [CrossRef]

- Dyńka, D.; Kowalcze, K.; Paziewska, A. The Role of Ketogenic Diet in the Treatment of Neurological Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.; Khandelwal, D.; Kalra, S.; Gupta, P.; Dutta, D.; Aggarwal, S. Ketogenic diet in endocrine disorders: Current perspectives. J Postgrad Med. 2017; 63(4):242-251. [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, T.N.; Shivane, A.G.; Kalamian, M.; Maroon, J.C.; Mukherjee, P.; Zuccoli, G. Ketogenic Metabolic Therapy, Without Chemo or Radiation, for the Long-Term Management of IDH1-Mutant Glioblastoma: An 80-Month Follow-Up Case Report. Front Nutr. 2021; 8:682243. [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Wakeham, D.; Ketter, T.; et al. Ketogenic Diet Intervention on Metabolic and Psychiatric Health in Bipolar and Schizophrenia: A Pilot Trial. Psychiatry Res. 2024; 335:115866. [CrossRef]

- Field, R.; Field, T.; Pourkazemi, F.; Rooney, K. Ketogenic diets and the nervous system: a scoping review of neurological outcomes from nutritional ketosis in animal studies. Nutr Res Rev. 2022; 35(2):268-281. [CrossRef]

- Operto, F.F.; Matricardi, S.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Verrotti, A.; Coppola, G. The Ketogenic Diet for the Treatment of Mood Disorders in Comorbidity With Epilepsy in Children and Adolescents. Front Pharmacol. 2020; 11:578396. [CrossRef]

- Yudkoff, M.; Daikhin, Y.; Nissim, I.; Lazarow, A.; Nissim, I. Ketogenic diet, brain glutamate metabolism and seizure control. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004; 70(3):277-285. [CrossRef]

- Gano, L.B.; Patel, M.; Rho, J.M. Ketogenic diets, mitochondria, and neurological diseases. J Lipid Res. 2014; 55(11):2211-2228. [CrossRef]

- Masino, S.A.; Rho, J.M. Mechanisms of Ketogenic Diet Action. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, eds. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. 4th ed. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012.

- Pinto, A.; Bonucci, A.; Maggi, E.; Corsi, M.; Businaro, R. Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ketogenic Diet: New Perspectives for Neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, D.; Kasperek, K.; Rękawek, P.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. The Therapeutic Role of Ketogenic Diet in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Jeon, S.-M.; Shin, S. Impact of a Ketogenic Diet on Metabolic Parameters in Patients with Obesity or Overweight and with or without Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, S. et al. Effect of the ketogenic diet on glycemic control, insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism in patients with T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Diabetes. 2020; 10(1):38. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wang, M.; Liang, J.; He, G.; Chen, N. Ketogenic Diet Benefits to Weight Loss, Glycemic Control, and Lipid Profiles in Overweight Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trails. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10429. [CrossRef]

- Volek, J.S.; Sharman, M.J.; Gómez, A.L. et al. Comparison of a very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diet on fasting lipids, LDL subclasses, insulin resistance, and postprandial lipemic responses in overweight women. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004; 23(2):177-184. [CrossRef]

- Staverosky, T. Ketogenic Weight Loss: The Lowering of Insulin Levels Is the Sleeping Giant in Patient Care. J Med Pract Manage. 2016; 32(1):63-66.

- Partsalaki, I.; Karvela, A.; Spiliotis, B.E. Metabolic impact of a ketogenic diet compared to a hypocaloric diet in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 25(7-8):697-704. [CrossRef]

- Kose, E.; Guzel, O.; Demir, K.; Arslan, N. Changes of thyroid hormonal status in patients receiving ketogenic diet due to intractable epilepsy. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017; 30(4):411-416. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ü.; Nalbantoğlu, Ö.; Güzin, Y. et al. The effect of ketogenic diet on thyroid functions in children with drug-resistant epilepsy. Neurol Sci. 2021; 42(12):5261-5269. [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, R.; Strinati, V.; Caputi, A.; Risi, R.; Spizzichini, M.L.; Mondo, A.; Spiniello, L.; Lubrano, C.; Giancotti, A.; Tuccinardi, D.; et al. A Ketogenic Diet Followed by Gradual Carbohydrate Reintroduction Restores Menstrual Cycles in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome with Oligomenorrhea Independent of Body Weight Loss: Results from a Single-Center, One-Arm, Pilot Study. Metabolites 2024, 14, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cincione, R.I.; Losavio, F.; Ciolli, F.; Valenzano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Messina, G.; Polito, R. Effects of Mixed of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight and Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghini, C.; Bianco, C.; Galanti, F.; Tamburelli, V.; Dal Lago, A.; Licata, E.; Gallo, M.; Fabiani, C.; Corno, R.; Miriello, D.; et al. The Impact of Nutritional Therapy in the Management of Overweight/Obese PCOS Patient Candidates for IVF. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, I.N.; Kaleva, N.N.; Dimcheva, T.D.; Markova, P.P.; Ivanov, I.S. Low-Carbohydrate (Ketogenic) Diet in Children with Obesity: Part 1—Diet Impact on Anthropometric Indicators and Indicators of Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance. Diseases 2025, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Röhling, M.; Martin, S. Insulin: too much of a good thing is bad. BMC Med. 2020; 18(1):224. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, J.P.; Jiang, Y.Y. et al. Fasting Plasma Insulin at 5 Years of Age Predicted Subsequent Weight Increase in Early Childhood over a 5-Year Period-The Da Qing Children Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015; 10(6):e0127389. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.D.; Corkey, B.E.; Istfan, N.W.; Apovian, C.M. Hyperinsulinemia: An Early Indicator of Metabolic Dysfunction. J Endocr Soc. 2019; 3(9):1727-1747. [CrossRef]

- Bönner, G. Hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994; 24 Suppl 2:S39-S49.

- Marshall, J.C.; Dunaif, A. Should all women with PCOS be treated for insulin resistance?. Fertil Steril. 2012; 97(1):18-22. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Nie, X.; He, B. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome across various tissues: an updated review of pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J Ovarian Res. 2023; 16(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, J.; González-Lucán, M.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Castro-Quintela, E. Insulin resistance is a cardiovascular risk factor in humans. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019; 13(2):1449-1455. [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Cruzat, V.; Arfuso, F.; Keane, K. Nutrient regulation of insulin secretion and action. J Endocrinol. 2014; 221(3):R105-R120. [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P.; Bender, K.; Kiely, A.; Brennan, L. Amino acid metabolism, insulin secretion and diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007; 35(Pt 5):1180-1186. [CrossRef]

- Jani, S.; Da Eira, D.; Stefanovic, M.; Ceddia, R.B. The ketogenic diet prevents steatosis and insulin resistance by reducing lipogenesis, diacylglycerol accumulation and protein kinase C activity in male rat liver. J Physiol. 2022; 600(18):4137-4151. [CrossRef]

- Gower, B.A.; Yurchishin, M.L.; Goss, A.M.; Knight, J.; Garvey, W.T. Beneficial Effects of Carbohydrate Restriction in Type 2 Diabetes Can Be Traced to Changes in Hepatic Metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Luukkonen, P.K.; Dufour, S.; Lyu, K. et al. Effect of a ketogenic diet on hepatic steatosis and hepatic mitochondrial metabolism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117(13):7347-7354. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Jiang, L.; You, Y. et al. Ketogenic diet ameliorates high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mouse skeletal muscle by alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2024; 702:149559. [CrossRef]

- Luong, T.V.; Pedersen, M.G.B.; Abild, C.B. et al. A 3-Week Ketogenic Diet Increases Skeletal Muscle Insulin Sensitivity in Individuals With Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Crossover Trial. Diabetes. 2024; 73(10):1631-1640. [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Tinsley, G.M.; Mattson, M.P.; De Vivo, I.; Dhawan, R.; Moro, T. Common and divergent molecular mechanisms of fasting and ketogenic diets. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024; 35(2):125-141. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Y.; Seo, D.S.; Jang, Y. Metabolic Effects of Ketogenic Diets: Exploring Whole-Body Metabolism in Connection with Adipose Tissue and Other Metabolic Organs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, A.; Mancin ,L.; Giacona, M.C; Bianco, A.; Caprio, M. Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Transl Med. 2020; 18(1):104. Published 2020 Feb 27. [CrossRef]

- Boelen, A.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Fliers, E. Fasting-induced changes in the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis. Thyroid. 2008 ;18(2):123-129. doi:10.1089/thy.2007.0253.

- Sui X, Jiang S, Zhang H, Wu F, Wang H, Yang C, Guo Y, Wang L, Li Y, Dai Z. The influence of extended fasting on thyroid hormone: local and differentiated regulatory mechanisms. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024 Aug 26;15:1443051. [CrossRef]

- Witkowska-Sędek, E.; Kucharska, A.; Rumińska, M.; Pyrżak, B. Thyroid dysfunction in obese and overweight children. Endokrynol Pol. 2017; 68(1):54-60. [CrossRef]

- Ghergherehchi, R.; Hazhir, N. Thyroid hormonal status among children with obesity. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015; 6(2):51-55. [CrossRef]

- Song, R.H.; Wang, B.; Yao, Q.M.; Li, Q.; Jia, X.; Zhang, J.A. The Impact of Obesity on Thyroid Autoimmunity and Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Immunol. 2019; 10:2349. [CrossRef]

- Molteberg, E.; Thorsby, P.M.; Kverneland, M. et al. Effects of modified Atkins diet on thyroid function in adult patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020; 111:107285. [CrossRef]

- Iacovides, S.; Maloney, S.K.; Bhana, S.; Angamia, Z.; Meiring RM. Could the ketogenic diet induce a shift in thyroid function and support a metabolic advantage in healthy participants? A pilot randomized-controlled-crossover trial. PLoS One. 2022; 17(6):e0269440. [CrossRef]

- Lie Fong, S.; Douma, A.; Verhaeghe, J. Implementing the international evidence-based guideline of assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): how to achieve weight loss in overweight and obese women with PCOS?. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021; 50(6):101894. [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.O.; Dumesic, D.A.; Chazenbalk, G.; Azziz, R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011; 7(4):219-231. [CrossRef]

- Stepto, N.K.; Cassar, S.; Joham, A.E. et al. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome have intrinsic insulin resistance on euglycaemic-hyperinsulaemic clamp. Hum Reprod. 2013; 28(3):777-784. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. 4th.; Dave, A.; Jaiswal, A. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Cureus. 2023; 15(10):e46859. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Li, C. et al. Evolving global trends in PCOS burden: a three-decade analysis (1990-2021) with projections to 2036 among adolescents and young adults. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025; 16:1569694. [CrossRef]

- Baylie, T.; Ayelgn, T.; Tiruneh, M.; Tesfa, K.H. Effect of Ketogenic Diet on Obesity and Other Metabolic Disorders: Narrative Review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2024; 17:1391-1401. [CrossRef]

- Fleigle, D.; Brumitt, J.; McCarthy, E.; Adelman, T.; Asbell, C. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and the Effects of a Ketogenic Diet: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannarella, R.; Rubulotta, M.; Leonardi, A. et al. Effects of ketogenic diets on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2025; 23(1):74. Published 2025 May 20. [CrossRef]

- Cincione, I.R.; Graziadio, C.; Marino, F. et al. Short-time effects of ketogenic diet or modestly hypocaloric Mediterranean diet on overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2023; 46(4):769-777. [CrossRef]

- Mavropoulos, J.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Hepburn, J.; Westman, E.C. The effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2005; 2:35. [CrossRef]

- Magagnini, M.C.; Condorelli, R.A.; Cimino, L.; Cannarella, R.; Aversa, A.; Calogero, A.E.; La Vignera, S. Does the Ketogenic Diet Improve the Quality of Ovarian Function in Obese Women? Nutrients 2022, 14, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Pang, N.; He, X. Breaking the metabolic-inflammatory vicious cycle in polycystic ovary syndrome: a comparative review of ketogenic and high-fat diets. Lipids Health Dis. 2025; 24(1):310. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yao, Q.; Li, X. et al. Effects of a ketogenic diet on reproductive and metabolic phenotypes in mice with polycystic ovary syndrome†. Biol Reprod. 2023; 108(4):597-610. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.F.; Sharkawi, S.S.; AbdelHameed, S.S. et al. Ketogenic diet restores hormonal, apoptotic/proliferative balance and enhances the effect of metformin on a letrozole-induced polycystic ovary model in rats. Life Sci. 2023; 313:121285. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, X. et al. Effect of the ketogenic diet on gut microbiome composition and metabolomics in polycystic ovarian syndrome rats induced by letrozole and a high-fat diet. Nutrition. 2023; 114:112127. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.A.M.J.L. New Insights into the Role of Insulin and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis in the Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuizen, A.G.; Rutters, F. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis in the regulation of energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2008; 94(2):169-177. [CrossRef]

- Vega-Beyhart, A.; Iruarrizaga, M.; Pané, A. et al. Endogenous cortisol excess confers a unique lipid signature and metabolic network. J Mol Med (Berl). 2021; 99(8):1085-1099. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Walker, B.R.; Ikuta, T. Systematic review and meta-analysis reveals acutely elevated plasma cortisol following fasting but not less severe calorie restriction. Stress. 2016; 19(2):151-157. [CrossRef]

- Polito, R.; Messina, G.; Valenzano, A.; Scarinci, A.; Villano, I.; Monda, M.; Cibelli, G.; Porro, C.; Pisanelli, D.; Monda, V.; et al. The Role of Very Low Calorie Ketogenic Diet in Sympathetic Activation through Cortisol Secretion in Male Obese Population. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stimson, R.H.; Johnstone, A.M.; Homer, N.Z. et al. Dietary macronutrient content alters cortisol metabolism independently of body weight changes in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007; 92(11):4480-4484. [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Caprio, M.; Watanabe, M. et al. Could very low-calorie ketogenic diets turn off low grade inflammation in obesity? Emerging evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2023; 63(26):8320-8336. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Tognini, P. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Bioactive Properties of a Ketogenic Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnotta, V.; Amodei, R.; Di Gaudio, F.; Giordano, C. Nutritional Intervention in Cushing’s Disease: The Ketogenic Diet’s Effects on Metabolic Comorbidities and Adrenal Steroids. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnotta, V.; Emanuele, F.; Amodei, R.; Giordano, C. Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet: A Potential Application in the Treatment of Hypercortisolism Comorbidities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thio, L.L. Hypothalamic hormones and metabolism. Epilepsy Res. 2012; 100(3):245-251. [CrossRef]

- Wang ZV, Scherer PE. Adiponectin, the past two decades. J Mol Cell Biol. 2016; 8(2):93-100. [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.; Choubey, M.; Tirumalasetty, M.B.; Arbee, S.; Mohib, M.M.; Wahiduzzaman, M.; Mamun, M.A.; Uddin, M.B.; Mohiuddin, M.S. Adiponectin: A Promising Target for the Treatment of Diabetes and Its Complications. Life 2023, 13, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parida, S.; Siddharth, S.; Sharma, D. Adiponectin, Obesity, and Cancer: Clash of the Bigwigs in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbe, A.; Bongrani, A.; Mellouk, N.; Estienne, A.; Kurowska, P.; Grandhaye, J.; Elfassy, Y.; Levy, R.; Rak, A.; Froment, P.; et al. Mechanisms of Adiponectin Action in Fertility: An Overview from Gametogenesis to Gestation in Humans and Animal Models in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Yoshida, H. Beneficial Effects of Adiponectin on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerotic Progression: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christou, G.A.; Kiortsis, D.N. Adiponectin and lipoprotein metabolism. Obes Rev. 2013; 14(12):939-949. [CrossRef]

- Orlando, A.; Nava, E.; Giussani, M.; Genovesi, S. Adiponectin and Cardiovascular Risk. From Pathophysiology to Clinic: Focus on Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Shao, J. Adiponectin and energy homeostasis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014; 15(2):149-156. [CrossRef]

- Zimmet, P.; Alberti, K.G.; Kaufman, F. et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents - an IDF consensus report. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007; 8(5):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Cipryan, L.; Dostal, T.; Plews, D.J.; Hofmann, P.; Laursen, P.B. Adiponectin/leptin ratio increases after a 12-week very low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet, and exercise training in healthy individuals: A non-randomized, parallel design study. Nutr Res. 2021; 87:22-30. [CrossRef]

- Chyra, M.; Roczniak, W.; Świętochowska, E.; Dudzińska, M.; Oświęcimska, J. The Effect of the Ketogenic Diet on Adiponectin, Omentin and Vaspin in Children with Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, M.; Hall, K.D.; Guo, J. et al. Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis and Inflammation in Humans Following an Isocaloric Ketogenic Diet. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019; 27(6):971-981. [CrossRef]

- Mohorko, N.; Černelič-Bizjak, M.; Poklar-Vatovec, T. et al. Weight loss, improved physical performance, cognitive function, eating behavior, and metabolic profile in a 12-week ketogenic diet in obese adults. Nutr Res. 2019; 62:64-77. [CrossRef]

- Shemirani, F.; Golzarand, M.; Salari-Moghaddam, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Effect of low-carbohydrate diet on adiponectin level in adults: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022; 62(14):3969-3978. [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D.; Li, Z. The Controversial Role of Adiponectin in Appetite Regulation of Animals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Kestin, M.; Schwarz, Y. et al. A low-fat high-carbohydrate diet reduces plasma total adiponectin concentrations compared to a moderate-fat diet with no impact on biomarkers of systemic inflammation in a randomized controlled feeding study. Eur J Nutr. 2016; 55(1):237-246. [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, R.; Cianflone, K.; McGahan, J.P. et al. Effects of sugar-sweetened beverages on plasma acylation stimulating protein, leptin and adiponectin: relationships with metabolic outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013; 21(12):2471-2480. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, G.C.; Feitoza, F.M.; Moreira, S.B. et al. Hypoadiponectinaemia in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease obese women is associated with infrequent intake of dietary sucrose and fatty foods. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014; 27 Suppl 2:301-312. [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, S.; Aiello, G.; Mansilla Di Martino, E.; Campaci, D.; Muthanna, F.M.S.; Lombardo, M. The Role of Adipose Tissue and Nutrition in the Regulation of Adiponectin. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varkaneh Kord, H.; M Tinsley, G.; O Santos, H. et al. The influence of fasting and energy-restricted diets on leptin and adiponectin levels in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2021; 40(4):1811-1821. [CrossRef]

- Widiatmaja, D.M.; Lutvyani, A.; Sari, D.R. et al. The effect of long-term ketogenic diet on serum adiponectin and insulin-like growth factor-1 levels in mice. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2021; 33(5):611-618. Published 2021 Oct 21. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.Q.; Li, J. Ketogenic diets and protective mechanisms in epilepsy, metabolic disorders, cancer, neuronal loss, and muscle and nerve degeneration. J Food Biochem. 2020; 44(3):e13140. [CrossRef]

- Neudorf, H.; Little, J.P. Impact of fasting & ketogenic interventions on the NLRP3 inflammasome: A narrative review. Biomed J. 2024; 47(1):100677. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Judd, R.L. Adiponectin Regulation and Function. Compr Physiol. 2018; 8(3):1031-1063. [CrossRef]

- Volek, J.S.; Phinney, S.D. The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Living, 1st ed.; Beyond Obesity LLC: Miami, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).