1. Introduction

Modern optical and SAR constellations now image the Earth at metre- and sub-metre-scale spatial resolutions, tens to hundreds of spectral bands, and revisit periods of hours to days. Sentinel-2, for example, provides 10 m multispectral imagery with 13 spectral bands and a global revisit frequency of about five days, while commercial missions deliver sub-metre panchromatic and 3–5 m multispectral data. Taken together, this combination of high spatial resolution, high spectral dimensionality, and high temporal frequency yields archives in which individual scenes can reach gigapixel scale and time series can span thousands of acquisitions. Models must capture long-range dependencies across space, spectrum, and time without losing small structures or exceeding realistic memory and energy budgets.

Deep neural networks have replaced hand-crafted descriptors by learning hierarchical features directly from data [

1,

2]. In remote sensing, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) became the standard backbone for scene classification, semantic segmentation, and object extraction [

3,

4]. Multi-scale encoders, dilated convolutions, and spectral–spatial fusion networks mitigate small objects, class imbalance, and label noise [

5,

6]. Yet even sophisticated CNN designs approximate long-range interactions only indirectly through deep stacking or large kernels, so the effective receptive field grows slowly and dependencies across full 4k × 4k tiles or long image time series remain difficult to model under realistic GPU constraints.

Transformer-based architectures address this limitation by replacing purely local processing with global self-attention over token sequences [

7,

8]. When adapted to remote sensing, ViT- and Swin-style backbones improve performance on land-cover mapping, change detection, and multi-temporal analysis [

9]. However, the quadratic cost of self-attention in the sequence length

is difficult to reconcile with the combined demands of high spatial resolution, large scene extent, and dense temporal sampling. For a

image divided into

patches,

, so a single attention map contains

entries; storing this map alone in 32-bit floating point requires roughly 1.1 GB per layer. Practical models therefore rely on patch cropping, windowed attention, or aggressive downsampling [

10,

11]. These remedies improve tractability but fracture global context and can suppress precisely those small structures—river channels, roads, building outlines—that are most relevant in Earth observation.

Structured state-space models (SSMs) offer a different route to long-range modeling. S4 showed that certain continuous-time linear dynamical systems can be implemented as convolutional kernels that model very long sequences with linear-time complexity and good numerical stability [

12]. Mamba extends this line by introducing selective state-space models whose parameters depend on the current token [

13,

14,

15]. Instead of fixed transition and input matrices, Mamba modulates them as functions of the feature vector, implementing content-aware scans that amplify informative regions and suppress background, while retaining

time and memory complexity via parallel scan algorithms.

For Earth observation data, these properties matter at scale. Flattening a tile into a sequence yields on the order of , and even patch-wise tokenization produces sequences far longer than in typical natural-image benchmarks. Long spectral vectors and dense temporal stacks further increase . Mamba-style architectures provide a way to process such sequences with linear complexity while conditioning state updates on scene content, an appealing feature for anisotropic geophysical structures and heterogeneous urban layouts. At the same time, serializing two- and three-dimensional EO data into one-dimensional sequences introduces design questions without direct analogues in text: scan paths, multi-directional traversal, and hybridization with convolutions or attention all shape which spatial, spectral, and temporal neighborhoods are effectively modeled.

Bao et al. recently presented the first dedicated survey of Vision Mamba techniques in remote sensing, organising roughly 120 studies by backbone design, scan strategy, and application task [

16]. Complementary surveys of visual Mamba architectures in generic computer vision [

17,

18,

19,

20] and the broader Mamba-360 review of state-space models, which categorises foundational SSMs into gating, structural, and recurrent paradigms across modalities, further situate Mamba within the wider SSM landscape [

21]. Building on these efforts, this review adopts an EO-centric perspective and deliberately narrows its focus to questions that are specific to, or particularly critical in, Earth observation.

The remainder of this review is structured as follows.

Section 2 revisits continuous- and discrete-time SSM formulations, links them to selective recurrence in visual Mamba backbones, and examines how different scanning mechanisms serialize two- and three-dimensional EO data.

Section 3 turns to spectral analysis and multi-source fusion, asking in which regimes Mamba-based models empirically improve over strong CNN and Transformer baselines, and where they mostly replicate existing behaviour with added complexity.

Section 4 then examines high-resolution visual perception—semantic segmentation, object detection, and change detection—from the standpoint of scan design and hybrid backbones rather than as a catalogue of architectures.

Section 5 covers restoration and generative applications, including super-resolution, pan-sharpening, and spatiotemporal fusion, and highlights where long-range propagation is demonstrably useful and where classical models remain adequate.

Section 6 synthesizes cross-cutting issues such as stability, numerical robustness, physical consistency, efficiency, and the emerging landscape of Mamba-based foundation models, and identifies open questions that, in our view, must be addressed before Mamba can be treated as a default choice in EO pipelines.

Section 7 summarises when Mamba is warranted in Earth observation, which architectural choices have practical impact, and which research questions remain most pressing.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Architectural Evolution

2.1. From Linear State-Space Models to Visual Mamba

State-space models (SSMs) describe linear dynamical systems via a latent state coupled to the input–output relation and admit standard tools for stability, controllability, and frequency analysis. Recent SSM-based neural sequence models implement this formalism as parameterised recurrent updates in discrete time. These architectures are designed to propagate information with linear complexity in sequence length and can complement self-attention in regimes with long contexts or tight memory budgets. Here we focus on the linear time-invariant (LTI) formulation and its discretization, and relate selective state-space updates to the design of visual Mamba backbones.

2.1.1. LTI State-Space Systems, Discretization, and Selective Recurrence

A continuous-time LTI state-space model with input

, hidden state

, and output

is written as

where

governs autonomous dynamics,

injects the input, and

maps the state to the output. For stable

, the system defines an impulse response and hence a convolution kernel

that encodes long-range dependencies. Structured SSMs such as S4 parameterize

so that the corresponding kernel can be evaluated efficiently and remains numerically stable over very long sequences [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29].

To use an SSM inside a neural network, the continuous system is discretized with step size

(for instance under a zero-order hold on the input). The discrete-time dynamics between indices

and

read

with discrete operators

and

obtained from

,

, and

by matrix exponentials or equivalent transforms. Unrolling this recursion yields a one-dimensional convolution

whose kernel is determined by

, so SSM layers can be implemented either as recurrent updates or as convolutions in the time or frequency domain. In both views, the cost of processing a sequence of length

scales linearly with

, in contrast to the quadratic cost of full self-attention.

Classical SSM layers keep

fixed across the sequence and learn them as global parameters. Mamba instead introduces

selective SSMs in which the effective dynamics depend on the current token. Given an input feature

at position

, the model computes token-dependent parameters

and uses them to construct discrete operators

and

. The hidden state is updated as

where

denotes the recurrent state. This selective recurrence enables the system to amplify informative tokens and suppress background responses, while still enjoying

time and memory complexity via highly optimized parallel scan implementations. For long EO sequences and large image tiles, this content-dependent yet linear-time mechanism is the key distinction from attention-based models.

2.1.2. Topological Mismatch Between 1D Priors and 2D EO Data

The formulation above assumes a one-dimensional sequence with a natural ordering, as in time series, audio, or text. In those settings, neighbouring tokens in index space are also neighbours in the underlying domain, and long-range dependencies correspond to genuinely large temporal or spatial gaps. Satellite and aerial images, by contrast, lie on a two-dimensional grid, and any flattening into a one-dimensional sequence inevitably distorts neighbourhood relations. This extends naturally to higher-dimensional tensors when spectral and temporal axes are included.

A naive raster scan that visits pixels row by row or column by column preserves locality along the fast axis but breaks it along the slow axis: adjacent tokens in the sequence may correspond to distant pixels, while diagonally adjacent pixels can be separated by many steps. As the spatial extent

grows, the mismatch between sequence distance and Euclidean distance increases, slowing down information propagation and inducing anisotropic artefacts in dense prediction maps on large images [

30]. These effects are especially relevant in EO, where rivers, roads, coastlines, and urban blocks exhibit strong directional structure that should be propagated coherently.

Visual SSM architectures mitigate this mismatch by redesigning both the scan trajectory and the recurrent update. Some architectures abandon strict causality and run both forward and backward passes along the same path. Others introduce cross-shaped or diagonal scans so that each pixel can exchange information with neighbours along rows, columns, and diagonals within a small number of steps. A third line of work treats the image as a continuous 2D trajectory and designs serpentine or space-filling curves that shorten the average path between semantically related regions [

31,

32,

33]. Together, these strategies narrow the gap between one-dimensional recurrence and two-dimensional geometry and provide more isotropic context for dense prediction and restoration.

In EO applications, the scan is therefore more than a numerical detail; it is a modelling assumption. Paths that align with expected physical anisotropies—for example along flight direction, river networks, or road grids—favour information flow along those structures, whereas near-isotropic scans are preferable when no dominant direction is known a priori. Many Mamba-based EO models implicitly encode such preferences through their scanning choices, even when these are presented as purely architectural variants.

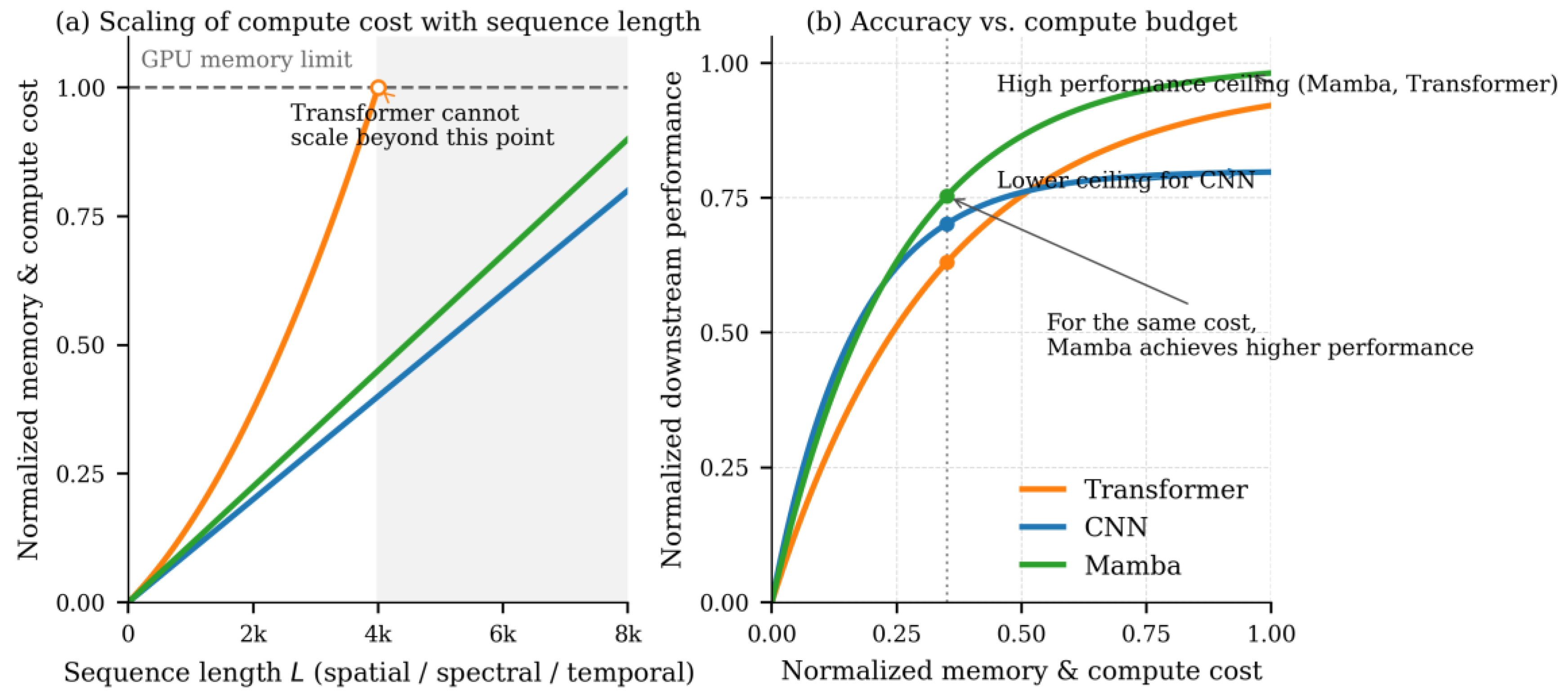

Figure 1.

Theoretical compute scaling and accuracy–cost trade-offs of CNN, Transformer, and Mamba long-range operators.

Figure 1.

Theoretical compute scaling and accuracy–cost trade-offs of CNN, Transformer, and Mamba long-range operators.

2.1.3. Visual Backbones and Hybridization

Once SSM layers had become competitive with attention in language modelling, they were rapidly imported into vision backbones. One class of designs replaces convolutional or Transformer blocks by visual SSM blocks at selected stages of the hierarchy, accumulating long-range context on high-resolution feature maps with linear-time complexity [

34]. In parallel, lightweight variants adapt the state dimension, projection layers, and gating mechanisms so that SSM layers remain stable and efficient when stacked deeply on large images [

35,

36,

37].

Pure SSM backbones are attractive from an efficiency standpoint but are not always optimal for EO tasks that demand both precise local texture modelling and long-range reasoning. Hybrid architectures therefore combine Mamba-style SSM blocks with convolutions or attention. A common pattern uses CNN layers in early stages to capture local edges, fine structures, and radiometric statistics, while SSM layers appear at mid and late stages to propagate information across large spatial extents or long temporal windows. Some models retain a small number of Transformer layers at the coarsest scales to explicitly model region-to-region and object-to-object relations on top of SSM features [

34,

35].

From a remote sensing perspective, this evolution turns visual SSMs into flexible building blocks rather than monolithic replacements. The same Mamba layer can augment a U-Net-like encoder–decoder, a Swin-style hierarchical Transformer, or a multi-branch fusion network, depending on spatial resolution, modality mix, and resource envelope [

35,

36,

37]. In the remainder of this review, the interplay between structured linear dynamics, selective recurrence, and hybridization with convolutions or attention is a recurring theme.

2.2. Scanning Mechanisms in Remote Sensing

In visual SSMs, the scan specifies the order in which pixels, spectral bands, or time steps are visited and thus which positions become neighbours along the one-dimensional sequence processed by the model. For EO imagery this ordering is not imposed by the sensor but chosen in modelling: it determines which locations can exchange information within a few recurrent updates and how closely the induced one-dimensional prior respects the underlying two- or three-dimensional geometry. In this review we consider scan schemes on images of size

and characterise them by two quantities: the effective path length, defined as the maximum number of recurrent updates required for information to propagate between two pixels, and the computational complexity as a function of the number of pixels

. Continuity-aware scanning has also been explored outside EO, for example in DiT-style Mamba diffusion models such as ZigMa, where zigzag paths enforce spatial continuity between neighbouring patches on the image grid [

38].

2.2.1. Directional and Multi-Directional Scans

The simplest image serialization is a row-wise or column-wise raster scan. Tokens that are adjacent along the fast axis remain close in the sequence, but neighbours along the slow axis can be separated by

or

steps, so information travels slowly across large tiles. Bidirectional variants alleviate this bias by running the recurrence forward and backward along the same path, allowing past and future tokens to influence each position. Bi-MambaHSI applies such bidirectional scans along spatial and spectral axes of hyperspectral cubes so that each pixel aggregates context beyond what standard convolutions provide [

39].

Omnidirectional schemes increase directional coverage. RS-Mamba designs an omnidirectional selective scan in which states are updated along horizontal, vertical, and diagonal paths, approximating isotropic receptive fields while keeping overall cost linear in the number of pixels [

40]. Cross-scan mechanisms such as those in VMamba restrict the number of directions but route information along a set of criss-cross paths; the diameter of the induced token graph then shrinks to

, which is advantageous for dense prediction on very large scenes [

32].

Spiral and centre-focused scans encode yet another prior. SpiralMamba starts from a central pixel and follows an outward spiral so that the prediction region and its immediate neighbourhood appear in a contiguous subsequence [

41]. Related schemes place the target pixel near the sequence centre and use tokens on both sides as spatial context. These designs are well suited to tasks where labels are attached to specific pixels or small patches, because the most relevant neighbourhood is processed as a compact segment while long-range dependencies are propagated along the remainder of the sequence.

In all cases, scan design implicitly states where relevant context is expected—along a dominant axis, across several orientations, or around a centre—and the SSM inherits this inductive bias through its recurrence.

2.2.2. Data-Adaptive and Geometry-Aware Scans

In heterogeneous scenes, hand-crafted raster or cross patterns can be misaligned with object boundaries or acquisition geometry. Several recent models therefore learn traversal paths or receptive regions from data so that the scan better follows local structure. QuadMamba uses a quadtree partitioning guided by learned locality scores; tokens are grouped into blocks with strong internal correlation, and an omnidirectional window-shift strategy moves information between blocks while preserving spatial coherence [

43]. FractalMamba++ serializes two-dimensional patches along Hilbert-like fractal curves, which preserve locality across scales and adapt to varying input resolutions without redesigning the scan [

43]. DAMamba couples the scan order with learned masks that concentrate updates on roads, building edges, and other salient structures, whereas MDA-RSM reweights multi-directional paths to reflect dominant building orientations and symmetries in urban layouts [

44,

45].

Task geometry also motivates specialized scans. For road and building extraction, traversals that approximate centre lines or follow estimated curvatures allow elongated man-made structures to be covered by short token paths. In change detection, cross-temporal scans traverse bi-temporal feature pairs at multiple scales, highlighting subtle structural differences between acquisitions while retaining linear complexity in the number of tokens. AtrousMamba adopts an atrous-window strategy with adjustable dilation rates: by increasing dilation, the receptive field grows without adding heavy attention blocks, which is beneficial when large-scale context and fine details must be captured simultaneously [

46]. These geometry-aware schemes reduce the discrepancy between Euclidean layout and one-dimensional ordering.

2.2.3. Transform-Domain and Irregular-Geometry Serialization

Scanning is not limited to regular grids. In several restoration models, SSM backbones are combined with Fourier or wavelet transforms: spatial tokens are serialized and processed by Mamba layers, while frequency-domain modules refine high-frequency details and impose priors on aliasing and noise [

47,

48]. FaRMamba makes this interaction explicit by restoring attenuated high-frequency components via multi-scale frequency blocks conditioned on Mamba features [

49]. For LiDAR and other irregular point sets, token sequences follow acquisition trajectories or learned neighbourhood graphs instead of raster order, aligning better with local geometry in geometric–semantic fusion networks [

50]. In satellite image time series, architectures such as SITSMamba process spatial features with CNN encoders and then apply Mamba along the temporal axis to model crop phenology and related dynamics under multi-task objectives [

51]. In these cases, “scan” refers as much to traversal in time, spectrum, or graph space as to traversal across pixel grids.

Table 1.

Typical scanning mechanisms in visual state-space models.

Table 1.

Typical scanning mechanisms in visual state-space models.

| Scan Type |

Path Length |

Directions |

Complexity |

Example |

| Raster |

|

1 |

Low |

Vim [31] |

| Bidirectional |

|

2 |

Low |

Bi-MambaHSI [39] |

| Cross-scan |

|

4 |

Medium |

VMamba [32] |

| Spiral |

|

1 |

Low |

SpiralMamba [41] |

| Omnidirectional |

|

6–8 |

Higher |

RS-Mamba [40] |

| Adaptive |

Learned |

Dynamic |

Variable |

DAMamba [44] |

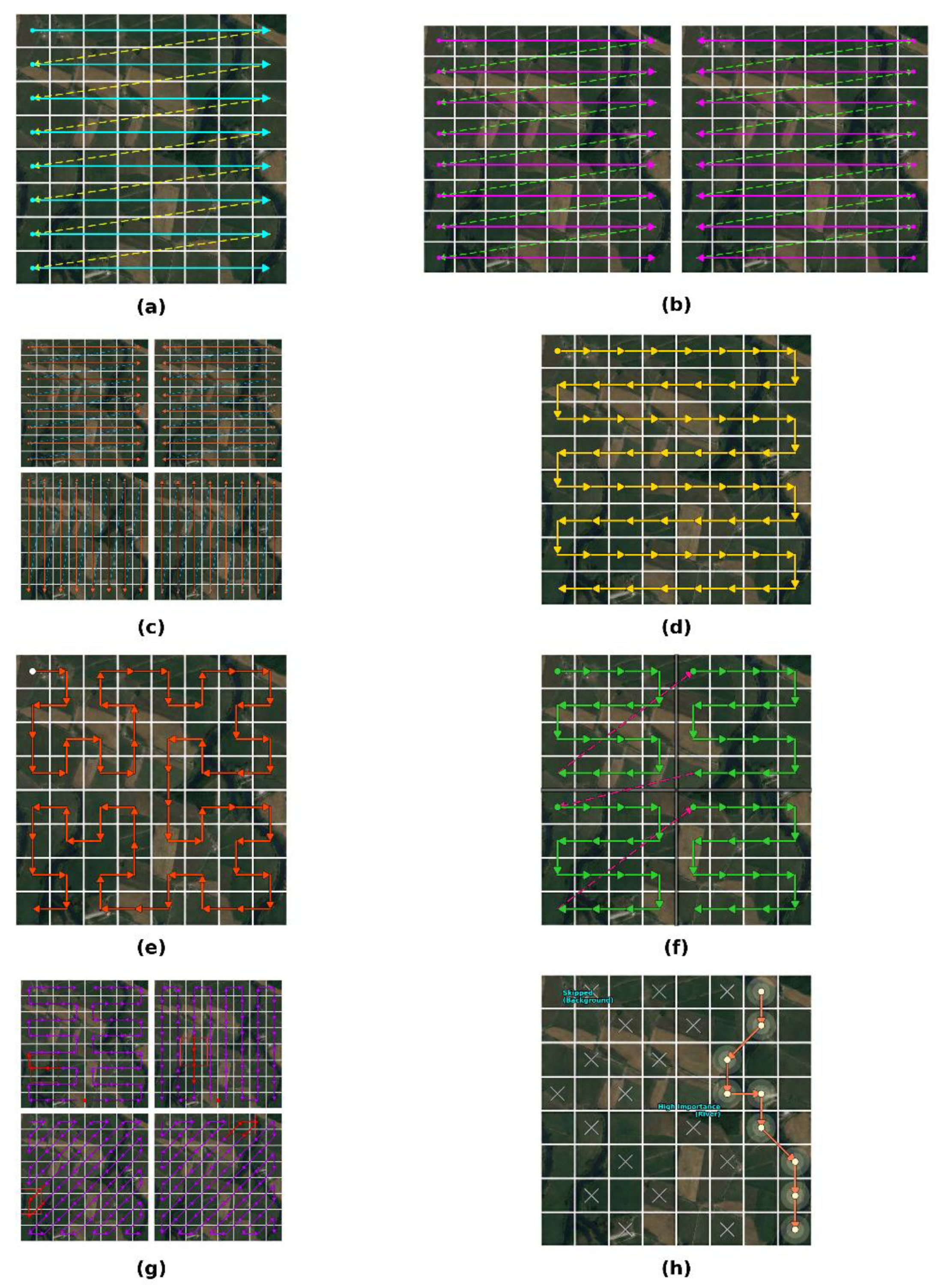

Figure 2.

(a) raster scan (baseline), (b) bidirectional scan, (c) four-way selective scan with four orthogonal directions, (d) zigzag scan forming 8 continuous serpentine directions obtained from horizontal and vertical zigzags and their flips, (e) Hilbert-curve/fractal scan that preserves strong spatial locality across the grid, (f) window-based continuous scan with locally connected U-shaped trajectories, (g) omnidirectional spectral scan (OS-Scan) combining row-wise, column-wise and ±diagonal trajectories, and (h) dynamic adaptive scan (DAS) whose path follows a data-driven importance map and largely skips low-importance regions.

Figure 2.

(a) raster scan (baseline), (b) bidirectional scan, (c) four-way selective scan with four orthogonal directions, (d) zigzag scan forming 8 continuous serpentine directions obtained from horizontal and vertical zigzags and their flips, (e) Hilbert-curve/fractal scan that preserves strong spatial locality across the grid, (f) window-based continuous scan with locally connected U-shaped trajectories, (g) omnidirectional spectral scan (OS-Scan) combining row-wise, column-wise and ±diagonal trajectories, and (h) dynamic adaptive scan (DAS) whose path follows a data-driven importance map and largely skips low-importance regions.

2.2.4. Empirical Guidelines and Design Trade-Offs

Comparative ablations show that scan patterns mainly differ in how they balance local continuity, directional coverage, and computational cost. In published studies, performance gaps are often modest and depend on the dataset, backbone, and scene structure. Zhu et al. evaluated one-directional, bidirectional, cross, and omnidirectional patterns across several backbones and datasets and observed that simple raster-like or bidirectional scans already provide strong baselines, while richer directional coverage yields consistent gains mainly for large scenes, pronounced anisotropy, or relatively shallow networks [

52]. For EO applications, three pragmatic considerations are particularly useful:

Scene geometry and directional structure. Long, thin, or strongly oriented structures (rivers, roads, building blocks) benefit from cross or omnidirectional scans that shorten paths along their main axes.

Spectral–spatial structure and coupling. Hyperspectral cubes and multi-source stacks call for scans that traverse spatial and spectral axes jointly or explicitly interleave them, rather than treating each band independently.

Sequence length and computational budget. Raster and bidirectional scans incur the smallest overhead and are suitable for very long sequences; omnidirectional and adaptive scans increase constant factors through additional branches or routing modules, even though asymptotic complexity in remains linear.

In Mamba-based EO models, the scan should therefore be treated as a task-dependent design choice tied to sensing geometry and resource constraints. Selecting an appropriate scan is often as influential as choosing the backbone itself, because it determines which neighbourhoods the SSM connects within a few recurrent steps and which structures the model can represent efficiently.

2.3. Architectural Hybrids and Design Patterns in EO

In current remote-sensing systems, Mamba is rarely used as a stand-alone backbone. Visual SSM blocks are instead inserted into CNN or Transformer pipelines, or attached as temporal and fusion modules around existing encoders. Architectures differ primarily in where Mamba is placed and how it interacts with local operators, not in the precise variant of the state-space layer. This subsection groups common design patterns and highlights their implications for dense prediction, multimodal fusion, and time-series analysis.

2.3.1. CNN–Mamba Hybrids for Dense Prediction

A first family of designs attaches Mamba blocks to convolutional encoders or decoders for dense prediction. Typical U-Net–style hybrids retain a CNN encoder to capture local textures and object boundaries and replace bottleneck or decoder stages by Mamba layers so that large-scale context is propagated with linear complexity [

41,

53,

54,

55,

56]. For very-high-resolution semantic segmentation and change detection, such CNN–Mamba U-Nets have been adapted to ultra-large tiles by combining shallow convolutional stems with deep Mamba decoders that aggregate global information while preserving fine details through skip connections [

41,

57].

A second pattern runs CNN and Mamba branches in parallel. The CNN stream emphasizes high-frequency details and radiometric statistics, whereas a Mamba stream handles long-range dependencies; their outputs are fused by attention or gating modules that weight features according to local signal characteristics [

53,

54,

55,

56]. This division of labour is particularly effective for road networks, river systems, and settlement structures, where sharp boundaries and global connectivity are simultaneously important.

Across these variants, a consistent principle emerges. Convolutional layers are typically placed close to the input, where an inductive bias for local stationarity and edge detection is beneficial, while Mamba blocks appear at deeper or lower-resolution stages, where tokens represent larger spatial regions and cross-region context becomes crucial [

41,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. In practice, the strongest CNN–Mamba hybrids are not those that replace all convolutions, but those that allocate Mamba capacity specifically to stages with large token counts and long-range interactions.

2.3.2. Transformer–Mamba Architectures for Efficiency and Attention

A second family of hybrids couples Mamba with Transformer layers or attention modules. One motivation is to retain the relational modelling power of self-attention at coarse scales while reducing quadratic cost at high resolutions. Vision backbones that assign Mamba blocks to early, high-resolution stages and reserve a few attention layers for coarse feature maps follow this strategy: they keep explicit attention where fine-grained relational reasoning is most useful, while SSM layers handle long-range propagation over dense token grids [

34,

58].

In hyperspectral analysis, several architectures replace parts of the Transformer encoder by Mamba blocks to handle long spectral–spatial sequences more efficiently [

59,

60]. Some designs use Transformer layers within each scale to model rich interactions among tokens, while Mamba experts handle cross-scale propagation in a mixture-of-experts fashion, allocating capacity according to local spectral or spatial patterns [

58]. Others employ Mamba as a spectral or temporal branch in parallel to spatial Transformers, so that spectral signatures and spatial layouts are captured with different inductive biases and then fused at intermediate layers [

59,

60,

61].

For multimodal fusion between optical and SAR images, hybrid backbones often combine CNN or Transformer encoders with Mamba modules that operate on modality-agnostic representations [

61]. In these systems, attention is used sparingly to align features across modalities or regions, whereas Mamba layers act as efficient carriers of context across the full scene. Overall, Transformer–Mamba hybrids tend to favour architectures in which attention is concentrated at a few strategic locations, and Mamba provides the long-range backbone.

2.3.3. Multimodal and Temporal Pipelines

A third pattern embeds Mamba inside multimodal or temporal pipelines rather than in purely spatial backbones. For satellite image time series, a common choice is a CNN-based spatial encoder followed by a Mamba temporal encoder that processes sequences of spatial features under multi-task objectives such as crop classification and phenology monitoring [

51,

62]. This arrangement leverages CNNs for local land-cover geometry and uses linear-time recurrence to handle long acquisition histories.

In multimodal fusion, Mamba layers often appear as cross-modal or cross-scale fusion blocks. For example, some networks adopt separate CNN encoders for hyperspectral and LiDAR or for optical and SAR images, and then use Mamba to aggregate features across modalities and resolutions before prediction [

61,

63,

64]. Other designs place Mamba modules at intermediate stages of encoder–decoder networks to propagate information between spatial scales or acquisition times, improving robustness to missing bands and acquisition gaps [

62,

65,

66].

Across these hybrids, one design rule is consistent with the discussion in

Section 2.2: convolutions and local attention are best used where spatial resolution is high and local details are critical, while Mamba layers are most effective at stages where tokens summarize larger receptive fields or encode long temporal windows. Treating Mamba as a flexible building block—rather than a wholesale replacement for CNNs or Transformers—has so far produced the most competitive EO architectures.

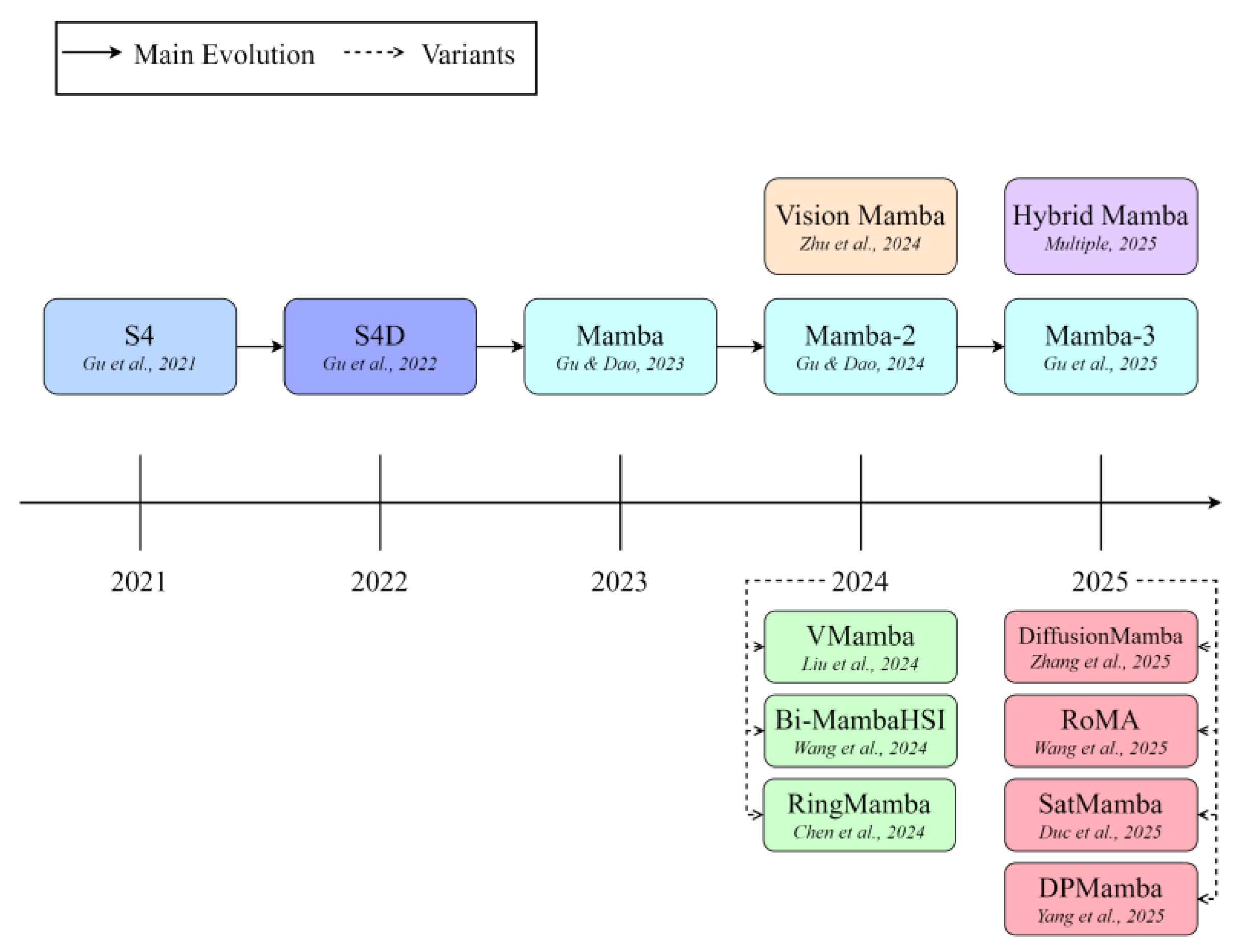

Figure 3.

Conceptual evolution of Mamba-style state-space models and their vision and Earth observation variants.

Figure 3.

Conceptual evolution of Mamba-style state-space models and their vision and Earth observation variants.

3. Spectral Analysis

Spectral analysis tasks exploit the rich information contained in hyperspectral and multispectral measurements, often in combination with auxiliary modalities such as LiDAR or SAR. Mamba-based state-space models have been introduced here not as drop-in replacements for CNNs or Transformers, but as linear-time backbones that can follow tailored scan paths, integrate prior knowledge, and remain deployable under real-world resource constraints. This section first discusses hyperspectral image (HSI) classification, then multi-source fusion, and finally unmixing, target detection, and anomaly detection.

3.1. Hyperspectral Image Classification

HSI classification assigns land-cover or material labels to pixels from data cubes with hundreds of contiguous bands, where subtle spectral variations and fine spatial structures jointly determine class boundaries. Early deep-learning approaches relied mainly on CNN backbones and shallow fusion of spectral and spatial cues, which limited their ability to model long-range spectral dependencies and cross-scene variability [

5,

67,

68]. Subsequent Transformer-based HSI classifiers improved global receptive fields but inherited quadratic attention costs and often required aggressive patching or windowing, which is difficult to reconcile with very long spectral–spatial sequences [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Visual SSMs such as Mamba offer a different compromise by treating spectra, spatial neighbourhoods, or mixed spectral–spatial tokens as 1-D sequences with linear-time recurrence, but their real advantage depends critically on how sequences are constructed and how Mamba is embedded into larger architectures [

74,

75,

76].

3.1.1. Serialization and Selective Scanning

The first design axis is the scan path used to serialize spectral–spatial cubes. Naïve raster scans over H×W×B grids generate very long sequences and mix foreground and background in a way that slows information propagation and weakens inductive bias. A series of Mamba-based HSI classifiers therefore designs the scan itself as an explicit modelling choice rather than an implementation detail.

Centre-focused trajectories reorganise small windows so that spectrally and spatially informative samples around the prediction pixel form a compact contiguous subsequence. Designs such as spiral or centre-path scanning place the central region near the beginning or middle of the sequence and update the state from both directions, which improves robustness to label noise and mixed pixels on benchmarks such as Indian Pines and Pavia University [

40,

77,

78]. Other works extend this idea to 3D spectral–spatial paths, where sequences interleave bands and spatial neighbours so that Mamba propagates information jointly across wavelength and space while retaining linear complexity [

69,

79,

80,

81,

82].

Beyond regular grids, several networks build sequences over superpixels or graphs. Superpixel-based and graph-based Mamba variants unfold tokens along region boundaries or k-NN graphs, which shortens effective sequence length and sharpens boundary representations in heterogeneous landscapes [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89]. These structured scans consistently report moderate but reliable gains over raster or cross-scan baselines on standard HSI benchmarks while keeping the recurrent kernel simple [

90,

91,

92,

93,

94]. Together, these results support a clear conclusion: for HSI classification, scan design is not a minor engineering detail but a primary source of performance, and centre-focused, 3D, and region-adaptive paths should be chosen deliberately according to acquisition geometry and label structure [

95,

96,

97,

98,

99].

3.1.2. Hybrid CNN–Mamba and Transformer–Mamba Architectures

A second design axis is how Mamba is integrated with convolutional and attention modules. Most competitive HSI classifiers now adopt

hybrid backbones where convolutions extract local edges and textures, while Mamba layers capture long-range spectral–spatial dependencies. Representative CNN–Mamba architectures use simple convolutional encoders followed by Mamba blocks or interleaved CNN–Mamba stages to extend context without sacrificing translation equivariance or efficient downsampling [

71,

72,

74,

75,

100]. In parallel, Transformer–Mamba hybrids retain attention in selected spectral or channel dimensions and delegate long-range spatial or cross-band modelling to SSM layers, thereby reducing FLOPs and memory relative to pure Transformers while maintaining accuracy on Houston, Pavia, and other public benchmarks [

70,

76,

80,

81,

82,

101,

102,

103,

104].

These results suggest a pragmatic view: in HSI classification, Mamba is most effective as a complement to convolutions or attention rather than a wholesale replacement. In particular, hybrid designs are attractive when high-resolution maps, long spectral profiles, and limited labels co-exist, while small-patch settings with abundant annotations may still favour lighter CNNs.

3.1.3. Frequency- and Morphology-Enhanced Modelling

A third line of work enriches Mamba with frequency-domain and morphological operators that encode prior knowledge about spectral smoothness and object shape. Wavelet- and Fourier-based architectures decompose HSI cubes into multi-scale frequency components before or within Mamba blocks, allowing the network to treat low-frequency background and high-frequency structures differently and to better reconstruct textured classes such as urban materials or vegetation mosaics [

105,

106,

107]. Morphology-aware designs integrate dilation, erosion, and related operators into token generation, so that shape information is already embedded when sequences are fed into the SSM [

87,

108,

109]. These frequency- and morphology-enhanced models typically provide incremental but consistent improvements over plain CNN–Mamba baselines, especially on noisy scenes or when object boundaries are poorly aligned with pixel grids [

92,

93,

94,

107].

3.1.4. Efficient, Few-Shot, and Transferable Learning

In practice, hyperspectral missions are usually constrained by scarce labels, domain shift between sensors, and tight memory and energy budgets on operational platforms. Under these constraints, recent work has begun to explore self-supervised, few-shot, and lightweight Mamba variants. Self-supervised methods embed composite-scanning Mamba blocks inside masked-reconstruction or contrastive frameworks, using large unlabeled HSI archives to pretrain representations that transfer well to downstream classification on Houston, Pavia, and WHU-Hi datasets [

92,

93,

94,

110,

111]. Few-shot extensions introduce metric-learning heads, dynamic token augmentation, or mixture-of-experts routing and consistently report higher accuracy than supervised Mamba baselines under five-shot settings [

78,

95,

111].

On the efficiency side, several architectures apply depth and width reductions, re-parameterisation, or structured pruning to Mamba backbones, often guided by insights from MambaOut-style analyses originally developed for classification networks [

76,

89,

97,

99,

100]. SpectralMamba-style families further compress spectra by sharing parameters across bands or compressing spectral channels, reducing FLOPs and parameters by factors of three to ten while maintaining comparable accuracy on datasets such as Houston2013 [

98,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105]. These results indicate that Mamba can be made competitive for onboard or embedded HSI processing when architectures are explicitly tuned for parameter and energy efficiency.

3.1.5. Summary

Across these strands, Mamba-based HSI classifiers have evolved from generic visual SSM backbones into task-aware architectures whose performance hinges on scan design, hybridisation with convolutions and attention, and efficiency-oriented training. First, careful design of centre-focused, 3D spectral–spatial, and region-adaptive scans is the main mechanism by which Mamba outperforms raster baselines on real HSI benchmarks, and there is little benefit in using state-space models with naïve sequence orderings. Second, hybrid CNN– and Transformer–Mamba backbones typically provide a better accuracy–efficiency trade-off than either pure CNNs or pure Transformers, especially for large scenes with limited labels. Third, frequency- and morphology-enhanced modules and self-supervised, few-shot, or lightweight variants add robustness in noisy or resource-constrained regimes but also increase design complexity and thus should be reserved for settings where their benefits have been empirically demonstrated.

3.2. Multi-Source Fusion

Many remote-sensing applications combine hyperspectral, multispectral, LiDAR, DSM, and SAR data rather than relying on a single sensor. Differences in imaging physics, spatial resolution, and coverage make fusion non-trivial, especially at large scale where long-range dependencies and misregistration must be handled under strict computational budgets. Transformer-based fusion networks alleviate some of these difficulties but their quadratic-complexity attention struggles at very high resolution or for long sequences.

Visual state-space models provide an alternative backbone with linear-time sequence modelling and flexible scan strategies. In multi-source settings, Mamba is used not only to propagate long-range context but also to encode cross-modal couplings directly within the state update. Current work can be grouped into three paradigms: cross-state interaction in heterogeneous classification, hybrid backbones with geometric or semantic priors, and frequency-aware or lightweight fusion, extended towards generative and reconstruction tasks.

3.2.1. Heterogeneous Modality Classification (HSI + LiDAR/DSM)

Joint classification of HSI with LiDAR or DSM requires exploiting both spectral signatures and height or geometric cues. A first paradigm replaces late feature concatenation with cross-state interaction: hidden states from different modalities interact during scanning so that cross-modal correlations are encoded in the recurrence.

CSFMamba implements a Cross-State Fusion module that couples convolutional feature extraction with Mamba-based global context modelling for HSI–LiDAR fusion [

112]. On MUUFL and Houston2018, it achieves overall accuracies several percentage points higher than CoupledCNN late-fusion baselines, and ablations confirm that removing the cross-state module leads to substantial performance drops. S

2CrossMamba extends this idea with an inverted-bottleneck Cross-Mamba design that updates multimodal states dynamically, reaching overall accuracies around 96% on MUUFL and clearly outperforming Transformer-based fusion backbones on MUUFL and Augsburg [

113]. MSFMamba similarly combines multi-scale spatial and spectral Mamba blocks with dedicated fusion modules for HSI and LiDAR or SAR, while CMFNet, TBi-Mamba, Mb-CMIFSD, and M2FMNet refine these cross-modal interactions through redundancy-aware fusion, triple bidirectional scanning, prototype-constrained self-distillation, or elevation-enhanced Mamba blocks [

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120].

A second paradigm overlays geometric or semantic priors onto Mamba backbones. DAHGMN couples graph convolutional networks with Mamba through hybrid GCN–Mamba blocks and dual-feature attention, where the GCN captures local geometric relationships from LiDAR and Mamba supplies long-range context [

121]. Removing either branch degrades performance, indicating that local graph structure and global state-space dynamics are complementary. Other fusion networks integrate CLIP-guided semantics, tri-branch encoders, or edge-aware priors with Mamba to emphasise semantic structure and contours in complex urban scenes [

122,

123,

124].

A third line focuses on frequency-aware and lightweight designs. LW-FVMamba combines skip-scanning Mamba backbones with frequency-domain channel learners to align multimodal features in the spectral frequency domain [

125]. On Houston, it uses roughly 0.12 million parameters and around 40 million FLOPs—significantly lower than ExViT, NCGLF

2, or standard VMamba—while slightly improving overall accuracy. TFFNet integrates fuzzy logic with Fourier and wavelet transform fusion to handle both uncertainty and spectral–spatial details in misregistered HSI–LiDAR pairs [

126].

These three paradigms—cross-state interaction, GCN- or semantics-augmented hybrids, and frequency-aware lightweight designs—form a compact taxonomy for HSI–LiDAR/DSM classification.

3.2.2. Generative Fusion and Reconstruction

Beyond classification, Mamba backbones are also used for generative fusion and reconstruction, including HSI–MSI fusion, pan-sharpening, and spatiotemporal super-resolution. Here the goal is to reconstruct high-quality images from complementary observations while preserving spectral fidelity and fine spatial detail under ill-posed conditions and imperfect registration.

HSI–MSI fusion networks such as FusionMamba and SSCM extend the standard Mamba block into dual-input or cross-Mamba variants that jointly process HSI and MSI streams in the state update [

127,

128]. Long-range spatial–spectral dependencies are modelled by Mamba layers, while Laplacian or wavelet modules emphasise high-frequency texture. SSRFN decouples spectral correction from spatial enhancement: a CNN-based spectral module first compensates upsampling errors, and a Mamba branch then injects global context into the corrected features [

129]. S

2CMamba tackles pan-sharpening with dual-branch priors that jointly enforce spatial sharpness and spectral fidelity [

130]. MCIFNet instead uses a Mamba backbone to generate latent codes and an implicit decoder that maps coordinates and codes to pixel values, allowing reconstruction at arbitrary resolutions [

131].

Registration is sometimes integrated into the fusion process itself. PRFCoAM alternates between a modal-unified local-aware registration module and an interactive attention–Mamba fusion module, mitigating error accumulation that typically occurs in two-stage pipelines [

132]. SINet couples Mamba with a multiscale invertible neural network based on Haar wavelets and regularises forward and inverse transforms to limit information loss during fusion [

133]. For spatiotemporal fusion, MambaSTFM and STFMamba apply visual state-space encoders to long sequences and use task-specific decoders with expert modules for spatial alignment or temporal prediction, so that dense time series can be reconstructed with linear-time encoders and modest decoder overhead [

62,

134].

3.2.3. Summary

Multi-source fusion showcases how Mamba can be specialized for remote sensing. Cross-state fusion replaces patch-wise concatenation with recurrent interaction across modalities; hybrid GCN–Mamba or semantics-guided designs inject geometric and task priors; and frequency-aware, skip-scanning variants demonstrate that high accuracy is compatible with strict parameter and FLOPs budgets. In generative and reconstruction tasks, dual-input Mamba blocks, registration–fusion coupling, and invertible or implicit decoders adapt state-space modelling to ill-posed inverse problems.

3.3. Hyperspectral Unmixing, Target and Anomaly Detection

Hyperspectral imagery provides dense spectral sampling, yet individual pixels typically contain mixtures of several materials embedded in structured backgrounds. Unmixing, target detection, and anomaly detection therefore need to exploit spectral correlations together with spatial context and background statistics. Classical linear-mixing and subspace models are appealing for their physical interpretability but become inaccurate in the presence of nonlinear interactions and complex clutter, while attention-based deep networks improve flexibility at the cost of substantial computation on full images. Recent work introduces Mamba-style state-space models that serialise spectra, spatial neighbourhoods, or pixel trajectories and use tailored scan schemes to balance global-context modelling with computational efficiency.

3.3.1. Hyperspectral Unmixing

Hyperspectral unmixing estimates endmember spectra and their abundances from mixed pixels, a problem that becomes increasingly ill-posed in the presence of noise, nonlinear mixing, and limited supervision. Classical geometrical and statistical approaches provide physically grounded solutions but face difficulties with nonlinear effects and large scenes [

135]. Mamba-based networks address these issues by combining local structure, long-range spectral–spatial context, and recurrent state updates.

MBUNet is a representative dual-stream design in which spatial and spectral features are extracted in parallel [

136]. Convolutional layers capture local spatial patterns, while a bidirectional Mamba module aggregates global information along spectral–spatial dimensions. On synthetic benchmarks such as Samson, Jasper Ridge, and Urban, MBUNet substantially reduces mean spectral angle distance and root mean square error compared with both a Transformer baseline (DeepTrans) and a pure Mamba model (UNMamba), indicating that joint use of convolutions and bidirectional Mamba scanning is crucial for accurate abundance estimation.

Progressive sequence models such as ProMU treat unmixing as a sequence prediction problem over pixels or regions [

137]. Stage-aware Mamba modules and progressive context selection refine abundances step by step. On Urban, ProMU reaches abundance RMSE comparable to image-level Mamba baselines while requiring roughly an order of magnitude fewer FLOPs than pixel-level Transformer models. Similar ideas appear in Mamba-SSFN and DGMNet, where Mamba branches are coupled with multi-scale convolutions or graph convolution to capture non-Euclidean spatial relationships and to improve scalability on large scenes [

138,

139,

140].

3.3.2. Hyperspectral Target Detection

In hyperspectral data, target detection aims to identify pixels belonging to specified materials or objects within complex, structured backgrounds. Effective detectors must remain sensitive to small targets while being robust to background variability and spectral perturbations.

HTMNet adopts a two-branch hybrid, with a Transformer stream for global multi-scale features and a LocalMamba stream with circular scanning that gathers local context around potential targets [

141]. A feature interaction fusion module combines the outputs so that both global background structure and fine-scale neighbourhood cues influence detection decisions. Across benchmarks such as San Diego I and II, Abu-airport-2, and low-contrast Salinas scenes, HTMNet achieves area-under-curve values effectively at saturation and slightly higher than both a pure Mamba detector (HTD-Mamba) and a Transformer-based baseline (TSTTD), showing that coupling local Mamba recurrences with Transformer-scale context is beneficial in cluttered backgrounds.

HTD-Mamba approaches target detection from a self-supervised perspective [

142]. A pyramid Mamba backbone and spatial-encoded spectral enhancement modules generate multiple spectral views for contrastive training, encouraging representations that are stable under spectral variations and effective at modelling background structure. Experiments indicate that such pretraining improves robustness in low-signal or few-label regimes, complementing hybrid architectures like HTMNet.

3.3.3. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection

In hyperspectral imagery, anomaly detection is concerned with pixels whose spectra deviate from an estimated background model, typically in the absence of an explicit target signature. Performance depends critically on how accurately the background is modelled and reconstructed.

DPMN introduces a deep-prior Mamba network that uses a bidirectional Mamba-based abundance generation module to obtain background representations, coupled with a learnable background dictionary that partitions the background into several subspaces [

143]. A regularization term combining total-variation and low-rank constraints enforces spatial smoothness and compactness, making it easier to separate anomalies from structured clutter. MMR-HAD adopts a reconstruction-based strategy with a multiscale Mamba reconstruction network, random masking to reduce the influence of anomalies on background estimation, dilated-attention enhancement, and dynamic feature fusion [

144]. On standard anomaly benchmarks, both methods report improved detection accuracy, particularly when anomalies are subtle or densely distributed, compared with RX-type and CNN-based approaches.

3.3.4. Summary

Across unmixing, target detection, and anomaly detection, Mamba is rarely used in isolation. Dual-stream unmixing networks rely on Mamba to propagate information along spectral and spatial dimensions while preserving explicit endmember modelling; progressive sequence models trade a small loss in accuracy for substantial reductions in computational cost. Hybrid target detectors combine Transformer-scale global context with local Mamba scans and benefit from self-supervised pretraining, while anomaly detectors use Mamba-based reconstructions as flexible background models combined with dictionaries, masking strategies, and regularizers.

4. General Visual Perception

High-resolution semantic segmentation, object and change detection, and scene classification underpin many operational Earth observation products. Models must process gigapixel scenes, capture long-range spatial dependencies, and scale across archives and sensors. Mamba backbones provide linear-complexity context modeling and are increasingly inserted into CNN or hybrid networks as drop-in replacements for attention or as dedicated long-range branches.

4.1. Semantic Segmentation

Semantic segmentation assigns a land-cover class to every pixel and is therefore a stringent test for models that must combine fine boundaries with kilometre-scale context. Classical CNN and encoder–decoder architectures, including U-Net–style and pyramid pooling variants, have built strong baselines for EO mapping but struggle to aggregate information over very large tiles without resorting to aggressive downsampling or tiling [

41,

54,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150]. Transformer-based segmentors extend the receptive field but are often memory-bound on high-resolution aerial and satellite images, which limits the spatial extent or batch size that can be processed in practice [

151,

152]. Mamba-based segmentation models attempt to retain CNN-like efficiency while adding linear-complexity propagation of long-range cues, and recent work has converged on a small number of design patterns rather than isolated architectures [

57,

153,

154].

4.1.1. Global–Local and Multiscale Architectures

Most Mamba segmentation networks adopt

global–local hybrids in which convolutions handle local texture and boundary details, while Mamba branches transport information across downsampled feature maps. Samba and MF-Mamba, for example, attach Mamba encoders to CNN feature pyramids so that the SSM state evolves over multi-scale semantic maps rather than raw pixels, leading to improved mIoU on Potsdam, Vaihingen, and LoveDA with modest parameter overhead relative to their CNN baselines [

57,

153,

155]. PPMamba wraps pyramid pooling modules with Mamba blocks and uses global–local state updates to refine predictions for large buildings and roads without oversmoothing small structures [

154,

156,

157]. FMLSNet and related designs extend this idea by coupling ResNet-style encoders with lightweight Mamba layers, focusing on long-range refinement of large objects while leaving edge sharpening to convolutional decoders [

158,

159,

160,

161].

Other works target

data efficiency and adaptation. LMVMamba and related models insert lightweight Mamba branches into multi-scale CNN encoders and share parameters across levels so that multi-scale features can be projected into a common linear dimension, which eases training on small labelled sets [

147,

148,

162,

163,

164]. Multi-scale feature aggregation combined with state-space propagation has been shown to reduce fragmentation in large objects and to stabilise predictions under distribution shifts between cities or acquisition conditions [

152,

165,

166,

167,

168].

Taken together, these results indicate that Mamba primarily serves as a global context carrier sitting on top of otherwise conventional segmentation stacks. Pure SSM encoders without convolutions remain rare and, on current benchmarks, offer limited evidence of clear benefits over carefully tuned CNNs and CNN–Transformer hybrids.

4.1.2. Spectral–Channel, Multimodal, and Generative Designs

A second line of research exploits Mamba beyond purely spatial modelling by acting along spectral channels, across modalities, or inside generative decoders. Spectral–channel networks such as CPSSNet treat channels as ordered sequences and insert Mamba along the channel dimension, which improves discrimination of classes whose signatures differ mainly in subtle spectral patterns rather than geometry [

158,

169,

170]. Multimodal designs push this idea further. MGF-GCN combines a graph encoder for DSM or LiDAR structure with a Mamba branch for optical imagery, using cross-modality fusion modules to align geometric and radiometric context for urban mapping [

171]. MoViM integrates Vision Mamba into paired SAR–optical streams, showing that state-space branches can propagate shared context while leaving modality-specific artefacts to CNN or Transformer sub-networks [

172].

Beyond discriminative models, DiffMamba couples CNN–Transformer encoders with diffusion decoders regularised by Mamba-style sequence propagation [

173]. In these architectures, Mamba primarily stabilises long-range dependencies inside the generative head and improves the realism of predicted segmentations under heavy clutter or class imbalance, rather than replacing spatial convolutions.

Overall, segmentation results to date support a restrained but positive assessment of Mamba in EO. Global–local hybrids clearly help when tiles are large, classes are highly imbalanced, and infrastructure patterns span long distances, while spectral–channel and multimodal variants extend these gains to multi-band and multi-sensor settings [

174,

175,

176]. At the same time, well-designed CNN or CNN–Transformer segmentors remain strong baselines, and the added complexity of Mamba branches is most defensible when long-range context or cross-modal coupling is demonstrably important.

4.2. Object Detection

Object detection in remote sensing covers oriented ships and vehicles, multi-scale buildings, and very small targets for traffic or aviation monitoring. CNN and Transformer detectors are strong baselines on public benchmarks, but they still trade off ultra-high-resolution inputs, small objects, and memory or latency constraints, so recent Mamba-based designs recast detection as sequence modelling, using SSM branches along scan paths aligned with object geometry to propagate long-range context at roughly linear cost.

4.2.1. Oriented and Multimodal Detection

Multimodal detectors for RGB–IR UAV imagery explicitly account for modality-dependent disparities and spatial offsets. Several networks adopt dual branches with mask-guided regularisation and offset-guided fusion so that cross-modal features remain stable under misregistration [

177,

178,

179]. Hybrid CNN–Mamba backbones, as in RemoteDet-Mamba, further encode cross-sensor context and background statistics, improving robustness in cluttered scenes [

180]. For hyperspectral data, edge-preserving dimensionality reduction combined with visual Mamba enhances spatial–spectral representations and improves small-object separability [

181].

A second line of work inserts Mamba blocks directly into detection pyramids. SSMNet augments the feature pyramid with state-space modules that aggregate information consistently across scales [

182]. For small objects in UAV imagery, MV-YOLO introduces hierarchical feature modulation, while YOLOv5_mamba couples bidirectional dense feedback with adaptive gate fusion to refine small-object representations in cluttered scenes [

183,

184]. Programmable gradients within SSMs have also been exploited in Soar to sharpen small-body detection under scarce or imbalanced data [

185].

For oriented detection, OriMamba builds a hybrid Mamba pyramid with a dynamic double head that decouples classification and regression, whereas MambaRetinaNet combines multi-scale convolutions with Mamba blocks to balance global context and local detail [

186,

187]. Multi-directional scanning strategies further improve infrared object detection by integrating features along several orientations to suppress structured clutter [

188]. In SAR ship detection, domain-adaptive state-space modules within a mean-teacher framework support unsupervised cross-domain transfer, complemented by large-strip convolutions and multi-granularity Mamba blocks that capture the elongated context of high-aspect-ratio targets [

189,

190]. Rotation-invariant backbones such as M-ReDet refine fine-grained features in dense ship clusters and other highly anisotropic scenes [

191]. Beyond bounding boxes, context-aware state-space models have been extended to multi-category counting by scanning local neighbourhoods during inference and to single-stream object tracking that maintains localisation in cluttered or forested environments [

192,

193].

4.2.2. Infrared Small-Target Detection

ISTD requires distinguishing faint, often sub-pixel targets from structured backgrounds. Several U-shaped architectures combine CNN encoders with Mamba blocks so that local detail is preserved while long-range context regularises background clutter. EAMNet introduces an adaptive filter module before Mamba encoding to enhance target visibility [

194]. HMCNet and SBMambaNet insert spatial-bidirectional Mamba blocks into hybrid CNN–Mamba encoders to improve suppression of structured background clutter [

195,

196]. SMILE applies a perspective transform to sparsify the background and uses spiral spectral scanning to learn coupled spatial–spectral features [

197], whereas MiM-ISTD introduces a “Mamba-in-Mamba” encoder with nested recurrences across spatial scales [

198]. Together, these designs treat Mamba mainly as an efficient background modeller that normalises structured clutter and highlights salient responses.

4.2.3. Salient Object Detection

In optical remote sensing images, salient object detection (SOD) aims to localise the most prominent geospatial targets in complex scenes so as to support subsequent analysis and decision-making [

199]. Topology-aware hierarchical Mamba networks impose structural constraints that suppress spurious saliency responses [

200]. TSFANet aligns multi-scale features in a Transformer–Mamba hybrid to maintain semantic consistency [

201], whereas LEMNet uses edge cues in a lightweight Mamba backbone to mitigate the lack of dense pixel annotations under weak supervision [

202].

4.3. Change Detection

Change detection estimates land-cover transitions between multi-temporal images while suppressing pseudo-changes caused by illumination, sensor differences, or registration errors. High-resolution urban and peri-urban scenes add further complexity through small building footprints, thin roads, and non-rigid deformations. A recent review indicates that change detection is moving towards foundation models and efficient long-sequence encoders [

203].

4.3.1. Spatiotemporal Interaction Backbones

Spatiotemporal interaction backbones place Mamba at the core of bi-temporal feature fusion. ChangeMamba uses shared Siamese encoders followed by a visual Mamba block that scans concatenated pre- and post-event features, allowing each location to integrate cross-time context at linear cost [

204]. CD-STMamba extends this idea with a Spatio-Temporal Interaction Module that encodes multi-dimensional correlations during both encoding and decoding [

205]. CD-Lamba introduces a Cross-Temporal Locally Adaptive State-Space Scan (CT-LASS) that is designed to enhance the locality perception of the scanning strategy while maintaining global spatio-temporal context in bi-temporal features [

206].

Methods such as 2DMCG, KAMamba, ST-Mamba, and SPRMamba explicitly target feature alignment and temporal reasoning on top of the core backbone. 2DMCG, for instance, couples a 2D Mamba encoder with change-flow guidance in the decoder to align bi-temporal features and mitigate spatial misregistration during fusion [

207]. KAMamba targets long MODIS time series by combining a knowledge-aware transition-matrix loss with sparse deformable Mamba modules to model land-cover dynamics [

208]. ST-Mamba introduces a Spatio–Temporal Synergistic Module that maps bi-temporal features into a shared latent space before Mamba propagation, thereby improving background consistency [

209]. SPRMamba balances salient and non-salient changes via a saliency-proportion reconciler and squeezed-window scanning [

210]. SMNet and LBCDMamba modify the scan pattern and pair Mamba blocks with modules such as RWKV or multi-branch patch attention, with the aim of improving long-range interaction modelling while keeping explicit pathways for local detail [

211,

212].

4.3.2. Hybrid Convolution–Mamba Architectures

Hybrid architectures retain convolutional blocks for local structure and insert Mamba modules as long-range aggregators. CDMamba interleaves convolutional and Mamba branches via Scaled Residual ConvMamba blocks so that local texture and edges are refined while change cues propagate over larger areas [

213]. CWmamba fuses a CNN-based base feature extractor with Mamba to jointly exploit local detail and global context, and Hybrid-MambaCD uses an iterative global–local feature fusion mechanism to merge CNN and Mamba features across scales [

214,

215]. ConMamba pushes this principle further by building a high-capacity hybrid encoder that deepens the interaction between convolutional and state-space features [

216].

Multiscale aggregation is handled explicitly in SPMNet, which adopts a Siamese pyramid Mamba network with hybrid fusion of high- and low-channel semantic features, and in LCCDMamba, whose multiscale information spatio-temporal fusion module aggregates difference information for land-cover change detection [

217,

218]. MF-VMamba combines a VMamba-based encoder with a multilevel attention decoder to interactively fuse global and local representations, whereas VMMCD targets efficiency with a lightweight design and a feature-guiding fusion module that removes redundancy while preserving accuracy [

219,

220]. Residual wavelet transforms have been integrated with Mamba to refine fine-grained structural changes and suppress noise [

221,

222]. Attention–Mamba combinations such as Mamba-MSCCA-Net and AM-CD further enhance hierarchical feature representation, and TTMGNet exploits a tree-topology Mamba to guide hierarchical incremental aggregation [

223,

224,

225]. For unsupervised scenarios, RVMamba couples visual Mamba with posterior-probability-space analysis to detect changes without labelled pairs [

226].

To manage multi-scale features more efficiently, a pyramid sequential processing strategy serialises multi-scale tokens into a long sequence and fuses them through Mamba updates [

227]. Generative approaches such as IMDCD combine Swin-Mamba encoders with diffusion models, using iterative denoising to refine change maps and reduce artefacts [

228]. Collectively, these results suggest that Mamba is most effective when it complements rather than replaces convolution, specialising in coherent long-range aggregation while CNN blocks handle precise localisation.

4.3.3. Alignment-Aware Designs

Geometric misalignment between bi-temporal images is a major source of false alarms. DC-Mamba adopts an “align-then-enhance” strategy: bi-temporal deformable alignment first corrects spatial offsets at the feature level, after which Mamba layers refine change cues [

229]. MSA (Mamba Semantic Alignment) instead operates at the semantic level, using a semantic-offset correction block to adjust deeper responses [

230]. Building on vision foundation models, SAM-Mamba and SAM2-CD adapt SAM2 encoders to change detection by combining activation-selection gates or Mamba decoders that suppress task-irrelevant variations while sharpening change boundaries [

231,

232]. These studies underline that state-space dynamics perform best when applied to feature fields that already respect the imaging geometry [

229,

230,

233].

4.3.4. Hyperspectral and Challenging Scenarios

Mamba’s linear complexity is particularly attractive for data-intensive modalities such as hyperspectral imaging and for adverse conditions such as low-light scenes. GDAMamba captures global contextual differences at the image level and enhances temporal spectral discrepancies for hyperspectral change detection [

234]. WDP-Mamba introduces a wavelet-augmented dual-branch design with adaptive positional embeddings to better preserve spatial–spectral topology [

235]. SFMS couples a tri-plane gated Mamba with SAM-guided priors to stabilise learning for rare classes in hyperspectral change detection [

236]. For low-light optical imagery, Mamba-LCD introduces illumination-aware state transitions that amplify weak signals in dark urban regions [

237].

4.3.5. Summary

Current Mamba-based change detectors span pure spatiotemporal backbones, hybrid CNN–Mamba networks, and designs that explicitly model cross-time alignment. Across these models, Mamba modules propagate long-range bi-temporal context at roughly linear complexity, while convolutional components refine high-frequency details, precise boundaries, and low-level registration [

204,

206,

214,

215,

227]. Dedicated alignment blocks—either deformable or foundation-model-based—supply the geometric consistency that state-space dynamics alone do not guarantee [

229,

230,

233].

Table 2.

Representative Mamba-based change detection methods and performance on WHU-CD dataset (Optical).

Table 2.

Representative Mamba-based change detection methods and performance on WHU-CD dataset (Optical).

| Method |

Core Idea |

F1 (%) |

| SPMNet [217] |

Siamese pyramid Mamba with hybrid fusion |

91.80 |

| VMMCD [220] |

Lightweight design & feature-guiding fusion |

92.52 |

| SAM2-CD [232] |

SAM2 adapter + activation selection gate |

92.56 |

| GSSR-Net [222] |

Geo-spatial structural refinement & wavelet |

93.07 |

| Mamba-LCD [237] |

Illumination-aware state transitions |

93.60 |

| SMNet [211] |

Semantic-guided Mamba with RWKV integration |

93.95 |

| ChangeMamba [204] |

Spatiotemporal interaction on concatenated features |

94.19 |

| SAM-Mamba [231] |

SAM2 encoder + Mamba decoder (two-stage) |

94.83 |

| 2DMCG [207] |

Change-flow guidance |

95.07 |

|

CD-STMamba [205] |

Spatio-temporal interaction module (STIM) |

95.45 |

4.4. Scene Classification

Scene classification assigns semantic labels such as residential, industrial, or farmland to image patches and therefore requires models that capture global layout, multi-scale structure, and label co-occurrence. In this setting, Mamba backbones are mainly used as linear-complexity substitutes for attention, often combined with convolutional modules.

For single-label classification, recent work focuses on how 1D state updates can approximate non-causal 2D structure. RSMamba uses a dynamic multi-path scanning mechanism that mixes forward, reverse, and random traversals and attains F1-scores around 95% on UCM and RESISC45 with fewer parameters than ViT-Base or Swin-Tiny [

238]. HC-Mamba couples a local content extraction module with cross-activation between convolutional features and Mamba states, while G-VMamba adds a contour enhancement branch to preserve luminance gradients [

239,

240]. To handle scale variation and limited labels, MPFASS-Net introduces progressive feature aggregation with orthogonal clustering self-supervision, ECP-Mamba applies multiscale contrastive learning to PolSAR data, and HSS-KAMNet hybridises spectral–spatial Kolmogorov–Arnold networks with dual Mamba branches for fine-grained land-cover identification [

241,

242,

243].

For multi-label scene classification, the main challenge is modeling dependencies between co-occurring categories. MLMamba combines a pyramid Mamba encoder with a feature-guided semantic modeling module that refines class-wise embeddings and their relations, achieving competitive mean average precision on UCM-ML and AID-ML with substantially reduced FLOPs and parameter counts compared with Transformer-based baselines [

244]. Overall, current Mamba-based scene classifiers fall into two patterns: multi-path or cross-activation scans for single-label scenes, and pyramid Mamba encoders coupled with semantic-relation modeling for multi-label settings.

5. Restoration, Generation, and Domain-Specific Applications

Visual state-space models are currently most mature in image restoration, where long-range dependencies and flexible scanning address the limits of local filters and quadratic-cost attention. Remote-sensing studies then extend these backbones to multimodal generation, compression, security, and scientific EO applications. This chapter therefore focuses on design patterns and where Mamba genuinely shifts the accuracy–efficiency–robustness trade space, rather than enumerating every variant.

5.1. Image Restoration and Geometric Reconstruction

Image restoration is a standard but critical stage in EO processing chains. Super-resolution, dehazing, denoising, and geometric reconstruction directly influence radiometric consistency, change-detection reliability, and the robustness of downstream products [

245,

246]. These problems combine local operators dictated by sensor physics and geometry with long-range correlations introduced by illumination, atmosphere, and acquisition layout. In this setting, Mamba-based models are appropriate only when long-sequence propagation plays a central role in the degradation process; otherwise, the additional architectural complexity is unlikely to provide clear benefits over well-engineered CNN- or Transformer-based restorers [

247,

248].

5.1.1. Super-Resolution

Remote-sensing super-resolution (SR) must sharpen man-made structures and edges at large scale without introducing spectral artefacts or aliasing [

47,

249]. Existing Mamba-based SR methods follow two broad strategies.

The first emphasises lightweight and hybrid architectures. Rep-Mamba, for instance, couples cross-scale state propagation with re-parameterised convolutions so that SSM layers carry context across large receptive fields while convolutions refine local details [

250]. Other works keep a conventional CNN backbone and plug Mamba blocks only into deeper layers or skip connections, which reduces the marginal cost of adopting Mamba and simplifies deployment on existing SR pipelines [

251,

252,

253]. These designs generally deliver modest but consistent PSNR/SSIM gains over pure CNN baselines on optical and infrared SR benchmarks, while reducing FLOPs compared with attention-heavy Transformers.

The second line develops frequency- and physics-aware SR models. Some architectures operate in wavelet or Fourier domains, where Mamba propagates information along multi-scale frequency coefficients rather than pixels, improving reconstruction of repetitive textures and fine structures [

48,

254,

255]. Others embed priors on degradation operators and spectral response. Spectral super-resolution models employ Mamba to couple high-resolution multispectral bands with low-resolution hyperspectral measurements, decomposing the mapping into a physically constrained range space and a learned null space that absorbs residual correlations [

256]. Here, the benefit of Mamba is clearest when spectral and spatial correlations interact over long ranges; on simple bicubic upsampling baselines with limited aliasing, CNNs often remain strong competitors.

Overall, SR studies suggest that Mamba is most valuable when SR is part of a broader multi-degradation or cross-sensor pipeline and when token sequences reflect physically meaningful propagation paths, not just flattened patches [

47,

48,

249,

250,

251,

252,

253,

254,

255,

256,

257,

258,

259,

260,

261,

262,

263].

5.1.2. Atmospheric and Weather Restoration

Remote sensing imagery is frequently degraded by haze, clouds, rain streaks, and complex atmospheric scattering, so atmospheric and weather restoration methods seek to recover clear-sky surface reflectance from such observations [

264,

265]. In these settings, long-range dependencies arise naturally: scattering patterns and cloud fields evolve smoothly over space and time, and restoration must respect radiometric consistency across large regions.

Mamba-based dehazing and deraining networks typically adopt hybrid encoders: convolutional stages extract local gradients and edges, while Mamba branches propagate information along scanlines or multi-scale windows to model extended haze layers and cloud structures [

266,

267,

268]. Some designs move to transform or polarimetric domains, where Mamba captures correlations among frequency components or scattering channels that are difficult to handle with local filters alone [

269,

270]. Compared with pure CNN baselines, these hybrids often improve structural similarity and colour fidelity under heavy haze, but the gains shrink on mild degradations where simple residual networks already perform well.

Weather-centric models apply similar ideas to rain, snow, and mixed artefacts, sometimes using recurrent or temporal SSM branches when short time series are available [

271,

272]. Additional illumination-aware and direction-adaptive dehazing and deraining variants follow the same pattern, combining scan-aware Mamba modules with conventional encoders to regularise large-scale shadow and cloud structures [

257,

258,

260,

261,

262,

263]. Here, Mamba’s linear-time recurrence allows the same kernel to process sequences of varying length without changing architecture, which is appealing for operational systems that must handle irregular revisit intervals.

5.1.3. Denoising and Generalised Restoration

Hyperspectral denoising is a stringent test for restoration models: Gaussian and shot noise, striping, dead lines, and mixed artefacts all appear across hundreds of correlated bands [

248,

249,

273]. In this context, Mamba provides a flexible way to couple spectral and spatial dependencies without quadratic attention.