1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

The Yellow and Bohai Seas, as a significant semi-enclosed continental shelf region in northern China, fulfil multiple functions including supplying fishery resources, providing ecological barrier protection, and supporting coastal economies. The stability of their ecosystems directly impacts regional sustainable development and ecological security. Chlorophyll a (Chl-a), as a core indicator of phytoplankton biomass, serves not only as a key parameter for assessing water eutrophication levels but also influences marine food web structures and biogeochemical cycling processes by regulating primary productivity [

1,

2]. The Yellow and Bohai Sea region lies within the East Asian monsoon zone, characterised by a complex natural environment: prevailing southeasterly and southerly winds dominate in summer, while northwesterly winds prevail in winter. The surface current field exhibits wind-driven characteristics, with surface currents primarily influenced by wind forces. The region primarily develops coastal water masses, a central cold water mass, and a high-salinity warm water mass in the southern Yellow Sea [

3]. The semi-enclosed topography and unique hydrodynamic conditions render this region particularly sensitive to climate change and anthropogenic disturbances. In recent decades, driven by dual pressures—climate stressors such as sea surface warming and abnormal wind speeds, alongside human activities including nutrient inputs from land-based sources, fishing, and coastal aquaculture—the issue of marine eutrophication has become increasingly pronounce [

4,

5]. Consequently, chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas exhibit complex spatiotemporal dynamics.

Research into chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas commenced in the 1960[

6]. Research methodologies have progressively evolved from traditional in-situ observations [

6,

7]to remote sensing monitoring [

8], with monitoring products becoming increasingly diverse and their accuracy steadily improving [

9]. In trend studies, scholars have produced numerous findings based on diverse satellite data sources and analytical methodologie [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]: Kiyomoto et al. utilised CZCS (Coastal Zone Colour Scanner) and OCTS (Ocean Colour and Temperature Scanner) data to reveal springtime algal blooms in the East China Se [

14]; Qian Li et al. employed MODIS Level 3 inversion data to identify a gradual increase in chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentrations in the Bohai Sea between 2002 and 2009[

15]. Meng Qinghui et al. employed the OC3 algorithm to invert observed data, proposing a V-shaped variation pattern for Chl-a concentrations in the Bohai Sea [

16]. Zhai et al. utilised MODIS-Aqua data to indicate a declining trend in Chl-a concentrations within the Bohai Sea and northern Yellow Sea from 2012 to 2018, hypothesising a correlation with climate change [

17]. In spatial and driving mechanism research, Ma Aohui, Tang, and Tian Hongzhen et al. employed multi-source remote sensing data alongside regional analysis and modal decomposition techniques to elucidate the spatiotemporal variations in chlorophyll-a concentrations across different bathymetric zones of the Yellow and Bohai Sea [

18]. They further examined the influence of environmental factors on these concentration [

19,

20]. Mamum et al. [

21] and Abbas et al. [

22] found that monsoons dominate algal growth in the basin. Even minor variations in water temperature and wind can exert considerable environmental impacts on the ecosystem [

23].

However, satellite remote sensing data are prone to significant gaps due to cloud interference. Although studies have employed multivariate interpolation methods such as DINEOF for data reconstruction [

24,

25,

26,

27], existing research exhibits notable limitations: firstly, reliance on traditional methods like linear regression can only reveal overall long-term trends in chlorophyll-a [

28], struggling to characterise differentiated variations across different concentration levels; Secondly, insufficient attention is paid to the coupled effects of environmental factors and the heterogeneity of driving mechanisms along the "nearshore-offshore" gradient. Furthermore, some studies employ relatively short time series, making it difficult to reflect long-term dynamic patterns.

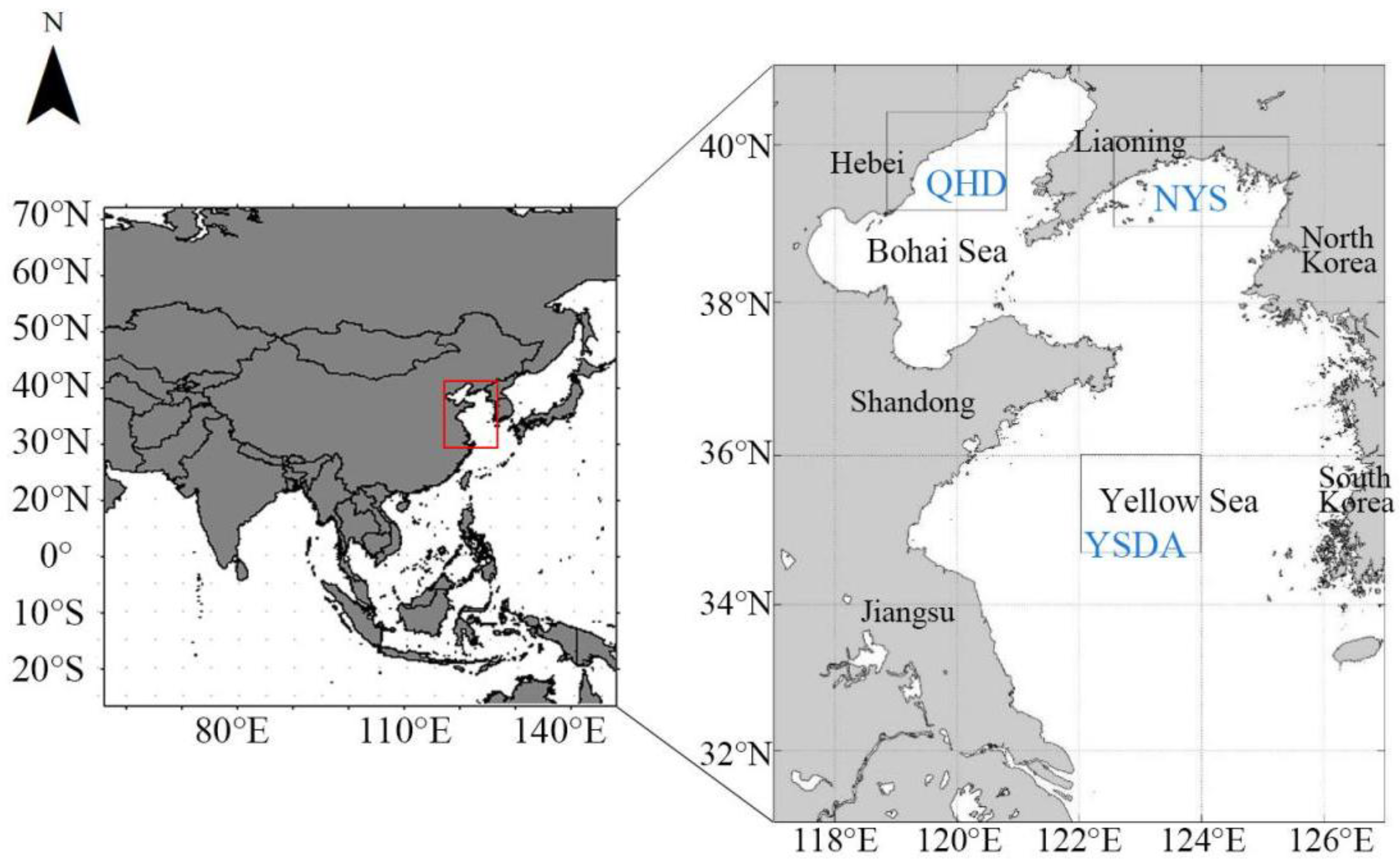

To address the aforementioned research gap, this study utilised chlorophyll-a concentrations from the Yellow and Bohai Seas (117–127°E, 31–41°N) as its subject matter. By employing deep learning algorithms, it constructs a multi-source remote sensing reconstruction dataset for chlorophyll concentration. For the first time, it introduces quantile regression methods to systematically analyse long-term trends in Chl-a at the 75th, 50th, and 25th quantile levels, along with their seasonal and spatial heterogeneity. Concurrently, utilising univariate linear regression models, this study quantitatively assessed the independent contributions and interactive effects of sea surface temperature (SST), mixed layer depth (MLD), wind speed, and sea level anomaly (SLA). To elucidate regional variations in driving mechanisms, this study selected three representative study areas: a portion of the northern Yellow Sea (characterising nearshore aquaculture zones), waters adjacent to Qinhuangdao (a nutrient input zone), and the deepwater southern Yellow Sea (an offshore zone) (

Figure 1): By contrasting nearshore regions, the study discerns variations in human activity impacts; through comparisons between nearshore and deep-water zones, it reveals differences in the regulation of nearshore processes versus open-ocean dynamics. These findings provide scientific support for eutrophication management and ecosystem restoration in the Yellow and Bohai Seas, while also offering methodological references for multi-scale dynamic studies of nearshore ecosystems under climate change.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Construction of the Chl-a Reconstruction Dataset

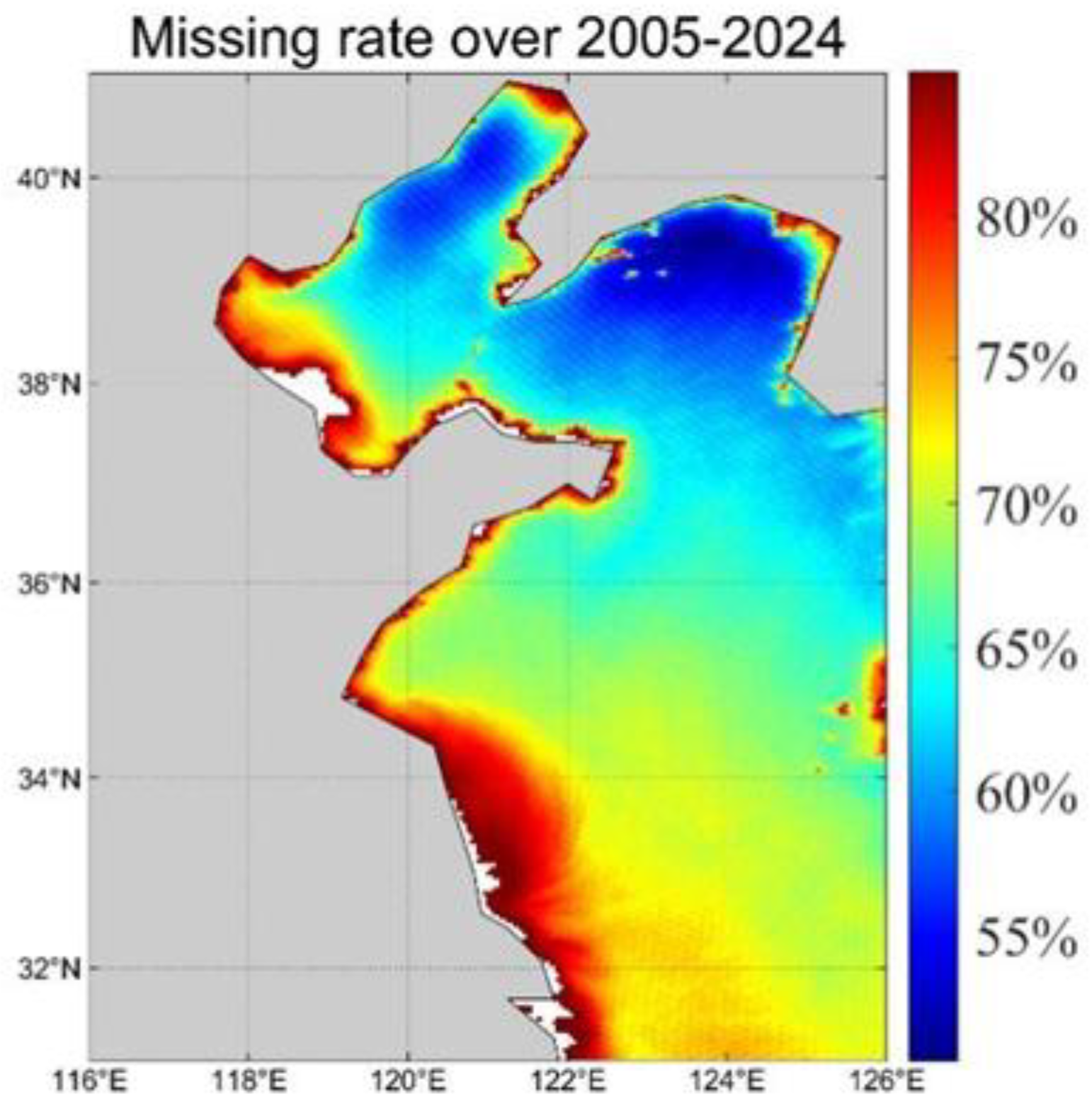

Chlorophyll-a data is derived from the multi-source remote sensing dataset integrated by the European Space Agency's GlobColour project (

https://hermes.acri.fr/index.php?class=archive). This dataset combines satellite remote sensing data from MODIS, MERIS, VIIRS, SeaWiFS and other sources. However, due to factors such as cloud cover, the raw data exhibits an average pixel missing rate as high as 84%, rendering it unsuitable for long-term continuous spatio-temporal dynamic analysis. Therefore, to fill these data gaps, this study employs interpolation reconstruction based on convolutional autoencoders.

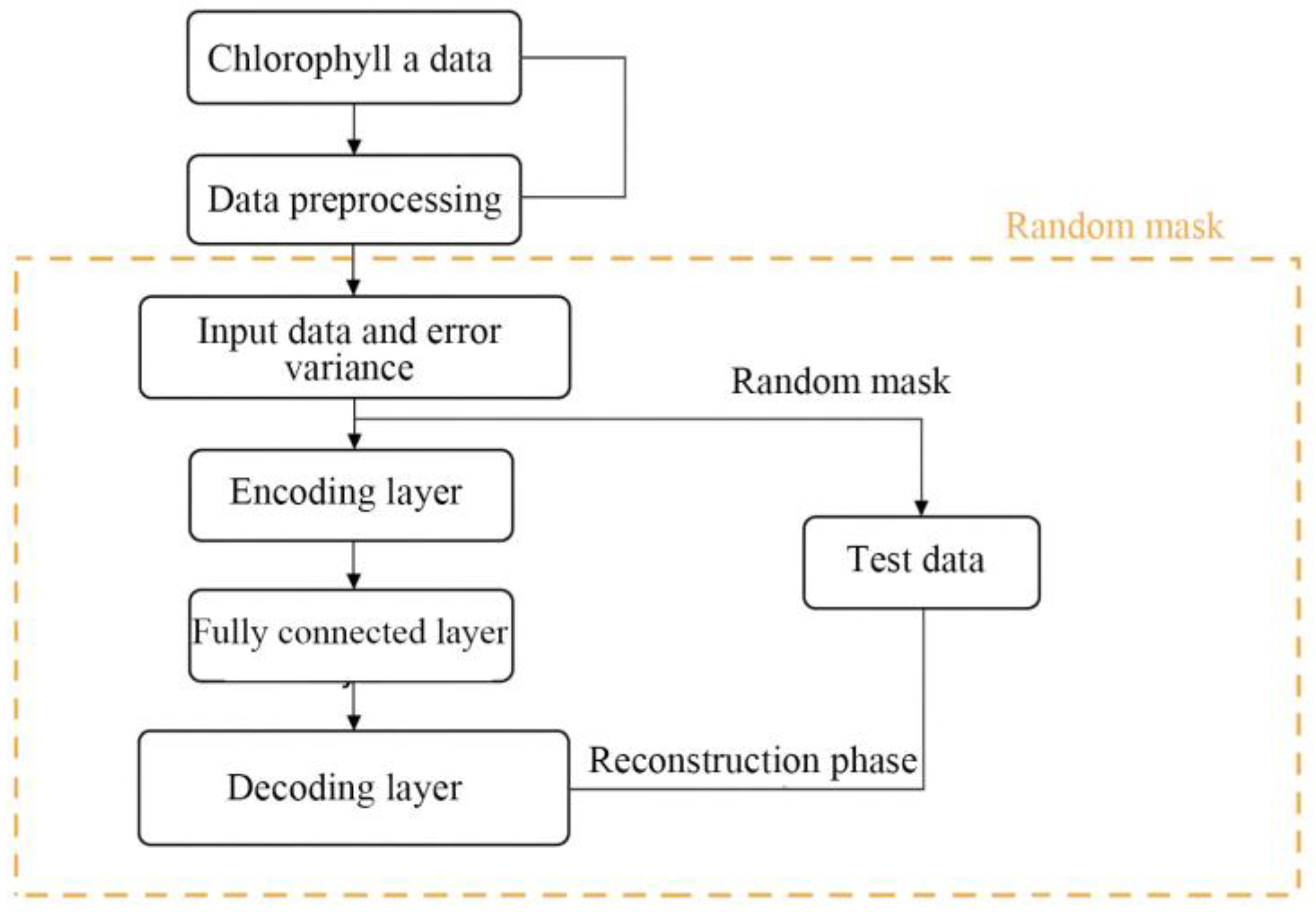

The DINCAE (Data-Interpolating Convolutional Auto-Encoder) algorithm is employed for data reconstruction. This algorithm, proposed by Barth et al. [

29], integrates the feature extraction capabilities of convolutional neural networks with the unsupervised learning advantages of autoencoders. When processing image-type data, it preserves more small-scale feature information [

29] and overcomes the limitations of traditional DINEOF methods in capturing spatio-temporal nonlinear relationships [

28,

29,

30]. It has been proven to be an effective tool for reconstructing remote sensing data such as chlorophyll-a.

The core workflow of DINCAE comprises three stages: preprocessing, training, and reconstruction (

Figure 2). The preprocessing stage follows the standard procedure outlined by Barth et al. [

29], which shall not be elaborated upon herein. The training stage employs a symmetric architecture comprising five encoding layers and five decoding layers: encoding layers alternate between convolutional and pooling layers, with the final convolutional layer followed by two fully connected layers to achieve a nonlinear combination of extracted features; The decoder comprises convolutional layers and nearest-neighbour interpolation layers, restoring spatial resolution through upsampling. Jump connections are established between the interpolation layers and the pooling layer outputs from the encoder to capture small-scale features lost during encoding.

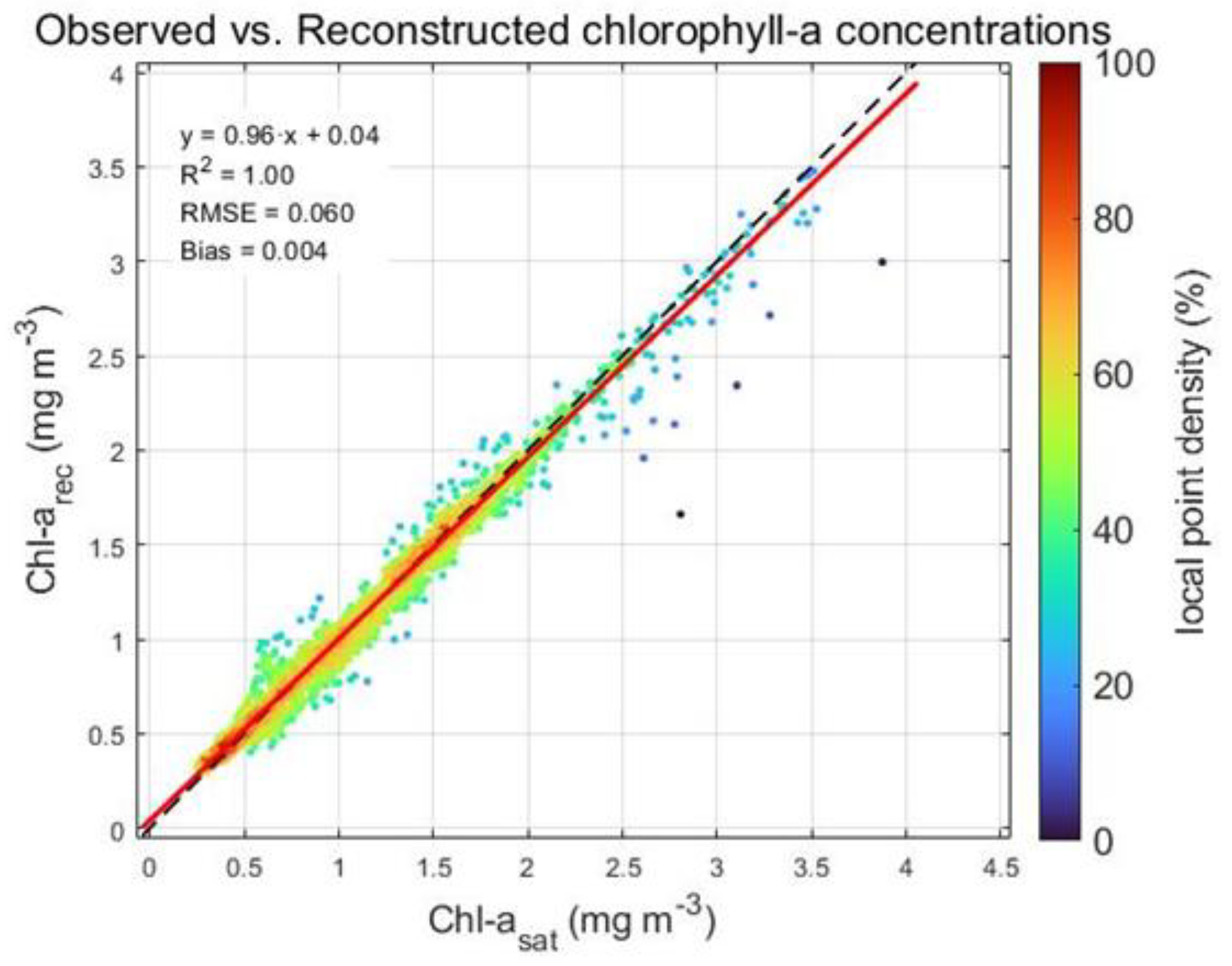

The reconstructed chlorophyll-a dataset underwent validation using mean squared error (MSE), mean bias (Bias), root mean squared error (RMSE), and linear correlation coefficient (R) (

Figure 4). Results indicate that the reconstructed data exhibits a linear correlation coefficient R = 0.92 with the original valid data, alongside an RMSE of 0.15 mg/m³ and a bias of 0.03 mg/m³. This accurately restores the spatial pattern of the original chlorophyll-a, particularly preserving critical small-scale features in high-value zones such as nearshore estuaries. The final product comprises a chlorophyll dataset for the Yellow and Bohai Seas, covering the temporal range from January 2005 to December 2024 and the spatial extent of 117°–127°E, 31°–41°N, with a uniform spatial resolution of 4 km × 4 km.

Figure 3.

Average Missing Rate in the Study Area.

Figure 3.

Average Missing Rate in the Study Area.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot density diagram of raw data versus DINCAE reconstructed data. Colour scale denotes local density (%). The black dashed line represents the 1:1 line. The red solid line indicates the best-fit line.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot density diagram of raw data versus DINCAE reconstructed data. Colour scale denotes local density (%). The black dashed line represents the 1:1 line. The red solid line indicates the best-fit line.

2.1.2. Environment Variable Data

The environmental drivers selected for this study comprise Sea Surface Temperature (SST), Sea Level Anomaly (SLA), Sea Surface Wind (SSW), and Mixed Layer Depth (MLD). The data sources and fundamental parameters for each are as follows:

SST, SLA, SSW, and SH data were derived from satellite remote sensing products provided by the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS), covering the period from January 2005 to December 2024. The spatial resolution for SST is 0.05° × 0.05°, while SLA, SSW, and SH data feature a spatial resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°.

All environmental variable data were resampled to 4km × 4km using bilinear interpolation to align with the spatio-temporal resolution of the Chl-a dataset, ensuring the validity of subsequent correlation analyses.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. QR

To refine the characterisation of long-term trends in chlorophyll-a across different concentration levels, this study employs quantile regression (QR) for trend analysis. This method, proposed by Bassett and Koenker in 1978 [

31], constitutes an extension of classical least squares regression (LSM). Subsequently introduced into ecological research by Cade et al. [

32], it has been demonstrated to effectively capture the heterogeneous effects of environmental factors on Chl-a, revealing detailed interactions between the two [

33].

LSM focuses on fitting the mean trend of the dependent variable, constructing a linear model by minimising the sum of squared errors between predicted and observed values:

Here, denotes the regression coefficient, represents the intercept, and signifies the error term. The dependent variable represented by exhibits a linear relationship with time .

Unlike LSM, quantile regression simultaneously quantifies the trend of the dependent variable at different quantiles (τ) by minimising the weighted absolute deviation and estimating regression coefficients, thereby fully capturing the spatio-temporal dynamics of the data distribution. For a given quantile τ, its objective function can be expressed as:

Here, is the absolute value function, is the exponential function, and when is 1, and 0 otherwise.

Given the susceptibility of extreme quantiles to outlier interference, this study employs the 0.05–0.95 quantile range for analysis, focusing on the variation characteristics of the 75th, 50th, and 25th quantiles (corresponding to low, medium, and high concentration levels respectively). The 75th quantile is defined as the high-concentration threshold for chlorophyll-a, serving to distinguish response differences across varying concentration gradients.

This study employs the conventional meteorological seasonal classification for this sea area: March to May constitutes spring, June to August summer, September to November autumn, and December to February winter.

3. Results and Dicussion

3.1. Long-Term Apatio-Temporal Variation Characteristics of Chl-a Concentration

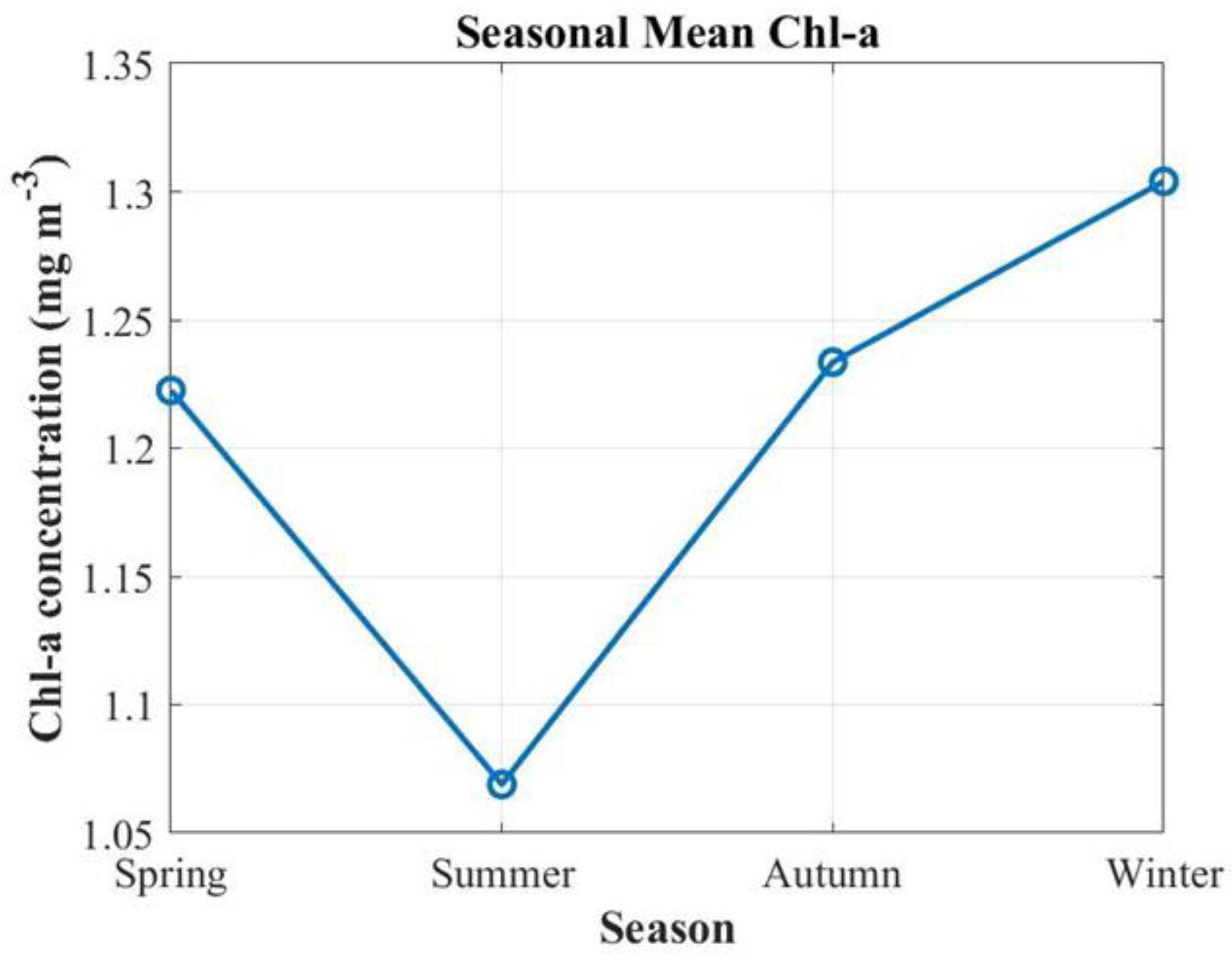

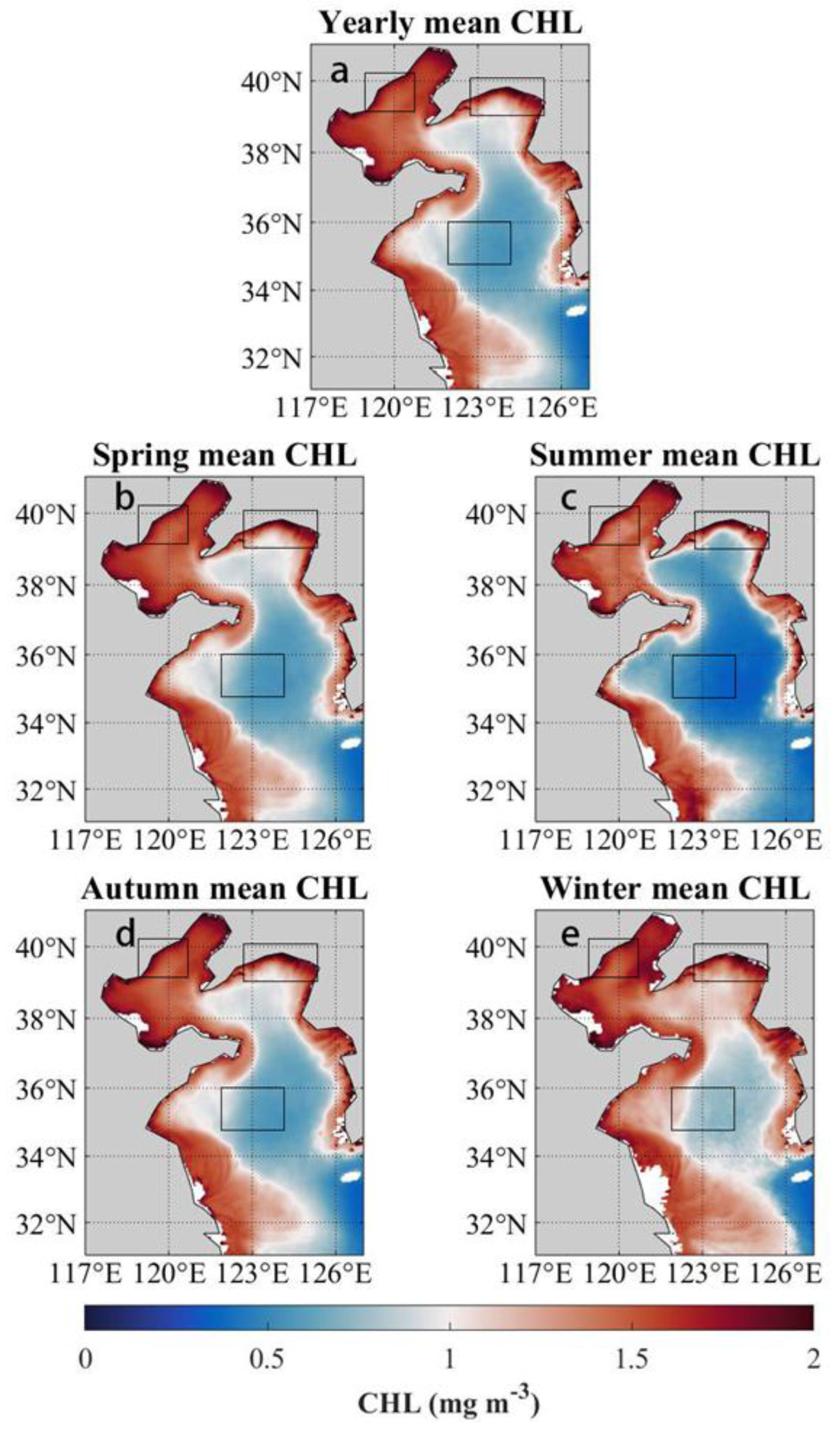

The annual average chlorophyll-a concentration in the Yellow and Bohai Seas is 1.23 mg/m³, exhibiting significant spatial and temporal heterogeneity. Seasonally, Chl-a concentrations gradually increase from autumn onwards, peaking in winter (1.31 mg/m³). Summer Chl-a levels (1.07 mg/m³) are markedly lower than those in spring (1.22 mg/m³) and autumn (1.23 mg/m³) (

Figure 5). Spatially, Chl-a concentrations in the Bohai Sea were generally higher than in the Yellow Sea, with high-value zones concentrated along the coast of Qinhuangdao (corresponding to the QHD characteristic zone) (1.69 mg/m³), southern Laizhou Bay, northern Liaodong Bay, and the northern Yellow Sea coast (corresponding to the characteristic zone NYS) (1.53 mg/m³). The average concentration in the Yellow Sea was only 1.09 mg/m³, remaining at a relatively low level overall.

3.1.1. Long-Term Trend

Quantitative analysis of long-term trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations was conducted using least squares method (LSM) and quantile regression (QR) (

Figure 6). Results indicate a significant decline in chlorophyll-a concentrations across the entire sea area, with the LSM-fitted annual decline rate at 0.0182 mg/(m³·a).

The quantile regression results further reveal distinct decline characteristics across different concentration levels: the annual decline rates corresponding to the 75th, 50th, and 25th quantiles were -4.82×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a), -4.50×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a), and -4.09×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a) respectively. The decline trend at the 75th percentile (high concentration level) closely approximates the LSM linear trend (-4.50×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a)). Declines were more pronounced in high-percentile sea areas (e.g., Bohai Strait, NYS, and QHD), with spatial heterogeneity in trends being particularly evident in high-latitude regions (e.g., Bohai Sea and NYS).

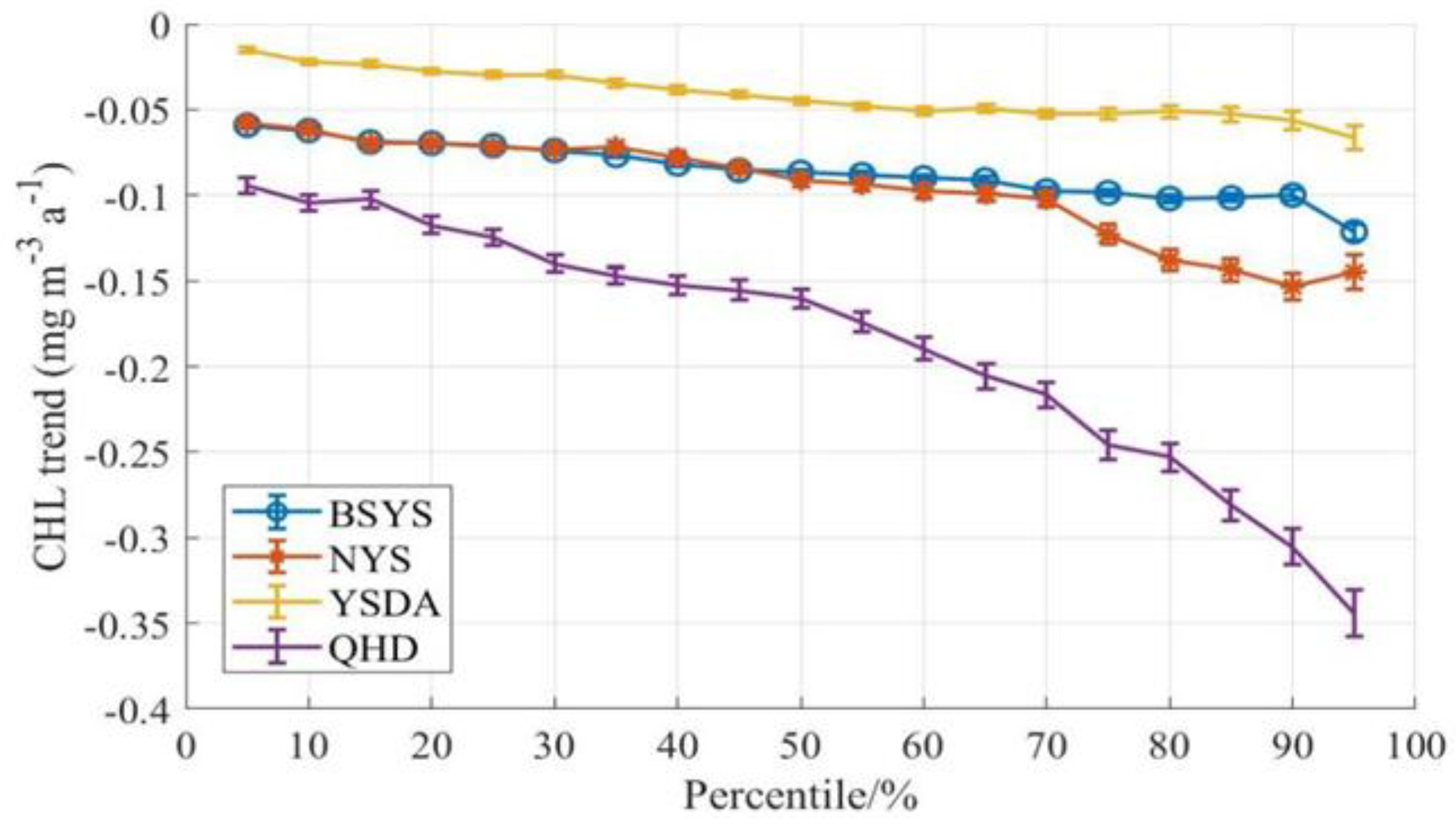

Comparative analysis of chlorophyll-a concentration changes across four major representative regions—the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), QHD, NYS, and YSDA—reveals markedly divergent decline trends between areas. The rate of chlorophyll-a decrease intensifies with increasing percentile rank [

35]. The annual decline rates in LSM were most pronounced in QHD and NYS, reaching -0.0268 mg/(m³・a) and -0.0315 mg/m³ respectively. This indicates a gradual shift in the characteristics of coastal waters influenced by human activities, which historically exhibited phytoplankton proliferation typical of eutrophicated bodies. Within the QHD region, a pronounced overall decline was observed, with a faster rate than other areas. This acceleration was particularly evident at high percentiles (>75%), where the annual decline exceeded 0.03 mg/(m³・a) when the percentile surpassed 80%. This phenomenon is closely linked to the regulatory measures implemented in Qinhuangdao, a significant coastal city and tourist destination. Strict land-based pollution control policies introduced in recent years have effectively reduced nutrient inputs into the sea, thereby curbing phytoplankton growth at its source [

34].

Figure 5.

Average chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas during spring, summer, autumn and winter.

Figure 5.

Average chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas during spring, summer, autumn and winter.

Figure 6.

Annual (a), spring (b), summer (c), autumn (d), and winter (e) mean chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas.

Figure 6.

Annual (a), spring (b), summer (c), autumn (d), and winter (e) mean chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Yellow and Bohai Seas.

Figure 7.

Annual trends in Chl-a concentration for the linear trend (a), 75th percentile (b), 50th percentile (c), and 25th percentile (d) using the classical least squares method (LSM).

Figure 7.

Annual trends in Chl-a concentration for the linear trend (a), 75th percentile (b), 50th percentile (c), and 25th percentile (d) using the classical least squares method (LSM).

Figure 8.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles throughout the year in the Bohai and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS). Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

Figure 8.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles throughout the year in the Bohai and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS). Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

3.1.2. Seasonal-Scale Variation Characteristics

To investigate the significant differences in Chl-a concentrations between winter (December to February) and summer (June to August), quantile regression analysis was conducted to further clarify variations within the seasonal scale:

The results indicate that the LSM fitting result for winter was -0.04 mg/(m³·a). The trends across all quantiles were generally consistent but varied in magnitude, with the decline rates corresponding to the 75th, 50th, and 25th quantiles being -0.0475 mg/(m³·a), -0.0303 mg/(m³·a), and -0.026 mg/(m³·a) respectively. The decline trend intensified with increasing percentile, indicating more pronounced reductions in Chl-a concentrations in winter within high-concentration zones. Notably, the high-percentile Chl-a decline trend was particularly pronounced in waters near the Gulf of Korea, suggesting this region is significantly impacted by dual influences of anthropogenic disturbances (aquaculture, industrial discharges, agricultural runoff, and other human activities) and climate change. Long-term terrestrial inputs of nutrients and pollutants may have altered the marine nutrient structure [

35].

Figure 9.

Winter Chl-a concentration trends: (a) Linear trend using the Least Squares Method (LSM), (b) 75th percentile trend, (c) 50th percentile trend, (d) 25th percentile trend.

Figure 9.

Winter Chl-a concentration trends: (a) Linear trend using the Least Squares Method (LSM), (b) 75th percentile trend, (c) 50th percentile trend, (d) 25th percentile trend.

Figure 10.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS) during winter. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

Figure 10.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS) during winter. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

The annual decline rate of summer LSM was 0.0638 mg/(m³·a), significantly higher than the annual average and winter values. The 75th, 50th, and 25th percentile trends were 0.0690 mg/(m³·a), 0.0456 mg/(m³·a), and 0.0375 mg/(m³·a), respectively (

Figure 11). The most pronounced decline was observed near the Yangtze River estuary. Key contributing factors include recent upstream Three Gorges Dam flood storage and dry-season discharge operations, which have resulted in lower water temperatures and reduced water transparency during the dry season, thereby inhibiting phytoplankton growth. Concurrently, flood-season flow regulation has diminished nutrient inputs. These dual effects collectively contribute to the interannual decline in Chl-a concentrations within this region [

36].

3.1.3. Comparative Analysis of Representative Sea Areas

Comparative analysis of chlorophyll-a concentration changes across four major representative regions—the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea as a whole (BSYS), QHD, NYS, and YSDA—reveals a consistent pattern across all areas: higher quantiles correlate with greater rates of decline. Moreover, the annual decline rates corresponding to each quantile did not exceed -0.05 mg/(m³・a) [

33], confirming the core characteristic of more pronounced declines in high-value Chl-a concentration zones within the Yellow and Bohai Seas. Concurrently, heterogeneous differences exist in the decline trends across regions: the annual LSM decline rates in the nearshore waters of QHD and NYS were most pronounced, reaching -0.0268 mg/(m³・a) and -0.0315 mg/m³ respectively. Within the QHD region, a pronounced overall decline was observed, with a faster rate than other areas. This acceleration was particularly evident at higher percentiles (>75%), where the annual decline exceeded 0.03 mg/(m³・a) when the percentile surpassed 80%. This phenomenon is closely linked to the control measures implemented in Qinhuangdao, a significant coastal city and tourist destination. The stringent land-based pollution control policies enforced in recent years have effectively reduced nutrient inputs into the sea, thereby curbing phytoplankton growth at its source.

Figure 11.

Trends in summer chlorophyll-a concentrations: (a) Linear trend using the least squares method (LSM), (b) 75th percentile trend, (c) 50th percentile trend, (d) 25th percentile trend.

Figure 11.

Trends in summer chlorophyll-a concentrations: (a) Linear trend using the least squares method (LSM), (b) 75th percentile trend, (c) 50th percentile trend, (d) 25th percentile trend.

Figure 12.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS) during summer. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

Figure 12.

Trends in chlorophyll-a concentrations corresponding to the 5th to 95th percentiles in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao waters (QHD), northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and deeper Yellow Sea waters (DS) during summer. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

3.2. Analysis of the Driving Mechanisms of Chl-a Concentration Variations by Relevant Environmental Factors

The Yellow and Bohai Seas, as semi-enclosed shelf seas, experience strong land-sea interactions and abundant nutrient supply due to the combined influence of the East Asian monsoon, multiple river inputs, and oceanic processes such as the Yellow Sea Warm Current and cold water masses [

6,

7]. Previous studies have confirmed that the interannual variability of chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentration is co-regulated by multiple environmental factors, and no single factor can fully explain its variation [

39]. Building upon the established long-term decline in Chl-a concentrations and its pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity, this chapter focuses on four key environmental factors: sea surface temperature (SST), mixed layer depth (MLD), wind speed, and sea level anomaly (SLA). Through Pearson correlation analysis and regional comparisons, we systematically elucidate the regulatory roles of these factors on Chl-a variations across the entire Yellow and Bohai Seas and their typical subregions (Northern Yellow Sea NYS, Qinhuangdao coastal QHD, Southern Yellow Sea deep water YSDA), elucidating the regional differentiation of driving mechanisms.

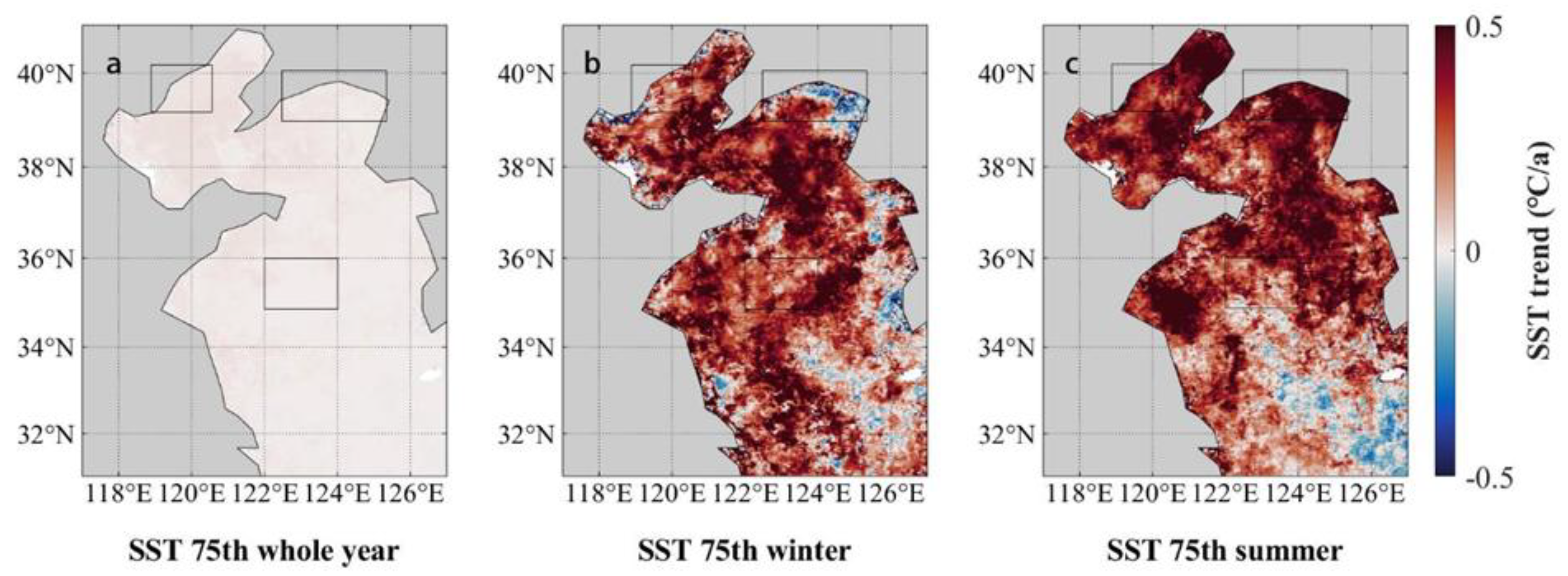

3.2.1. SST

Against the backdrop of global warming, the study area exhibited a pronounced overall upward trend in SST from 2005 to 2024, with marked seasonal variations: the average warming rate at the 75th percentile during summer (0.3314°C/a) exceeded that of winter (0.2709°C/a), correlating with the more pronounced summer decline in chlorophyll-a (

Figure 6).

Across the entire marine domain, SST exhibits a weak negative correlation with Chl-a (r = -0.2211), indicating that ocean warming generally exerts a certain inhibitory effect on phytoplankton growth. The core mechanism of this inhibitory effect is that elevated temperatures reduce the solubility of nutrients such as oxygen, silicate, and phosphate in the water column. Concurrently, excessively high temperatures may exceed the optimal growth range for phytoplankton, thereby suppressing photosynthesis and biomass accumulation [

40].

Regarding regional differentiation characteristics, SST exhibited extremely weak correlations with chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) variations in the Northern Yellow Sea (NYS) and the deep southern Yellow Sea (YSDA) (r = 0.0875, r = −0.0446), indicating limited direct regulation of Chl-a by SST in these regions. Concentration variations are primarily governed by other factors such as monsoon-driven water mixing and terrestrial nutrient inputs. SST may indirectly influence phytoplankton growth through coupled interactions with factors like mixed layer depth (MLD) and wind speed[

40]. In contrast, the negative correlation between SST and QHD (r = −0.1987) is more pronounced, reflecting greater phytoplankton sensitivity to temperature fluctuations in this area. Warming-induced reductions in nutrient supply and deteriorating growth conditions further exacerbate the decline in chlorophyll-a concentrations.

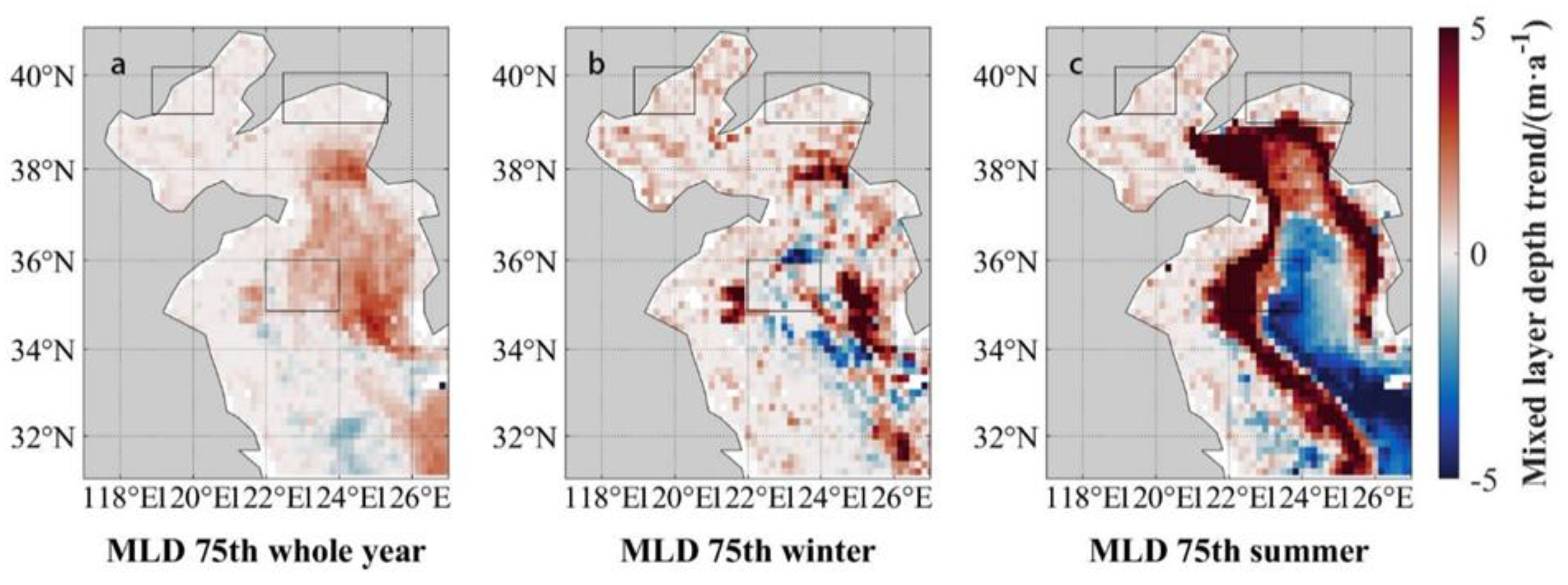

3.2.2. MLD

Across the entire marine area, MLD exhibits the strongest correlation with Chl-a (r = -0.5226), making it the key physical factor influencing the spatiotemporal variation of Chl-a. The core of this regulatory mechanism lies in the fact that mixed layer depth directly determines phytoplankton's light exposure conditions and nutrient availability: excessive mixed layer depth removes phytoplankton from the photic zone, reducing average light exposure levels; simultaneously, enhanced vertical mixing dilutes surface nutrient concentrations. These dual effects collectively inhibit phytoplankton growth [

41].

In distinct characteristic regions, the differential effects of MLD manifest as follows: MLD exhibits a significant negative correlation with chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) in the Northern Yellow Sea (NYS) (r = -0.4006). Considering the monsoon characteristics of this region, the weakening of winter wind speeds results in a shallower mixed layer. While this reduces vertical diffusion of phytoplankton, it also constrains the upwelling supply of nutrients from the bottom layer, ultimately manifesting as an inhibitory effect on Chl-a. In the Qinhuangdao coastal area (QHD), an extremely strong negative correlation (r = −0.9831) highlights MLD as the primary regulatory factor governing Chl-a variations in this region. Given the shallow water depth in this area, minor variations in mixed layer depth significantly alter surface water stability. Compounded by high nutrient backgrounds from land-based inputs, deepening MLD disrupts stratification and dilutes phytoplankton concentrations, becoming a key driver of declining Chl-a concentrations. In the southern deep waters of the Yellow Sea (YSDA), the correlation between MLD and Chl-a is weaker, indicating that this region is more significantly influenced by oceanic dynamic processes (such as cold water mass fluctuations). The regulatory role of mixed layer depth is mitigated by other factors, with Chl-a being indirectly affected primarily through interactions with water mass exchange.

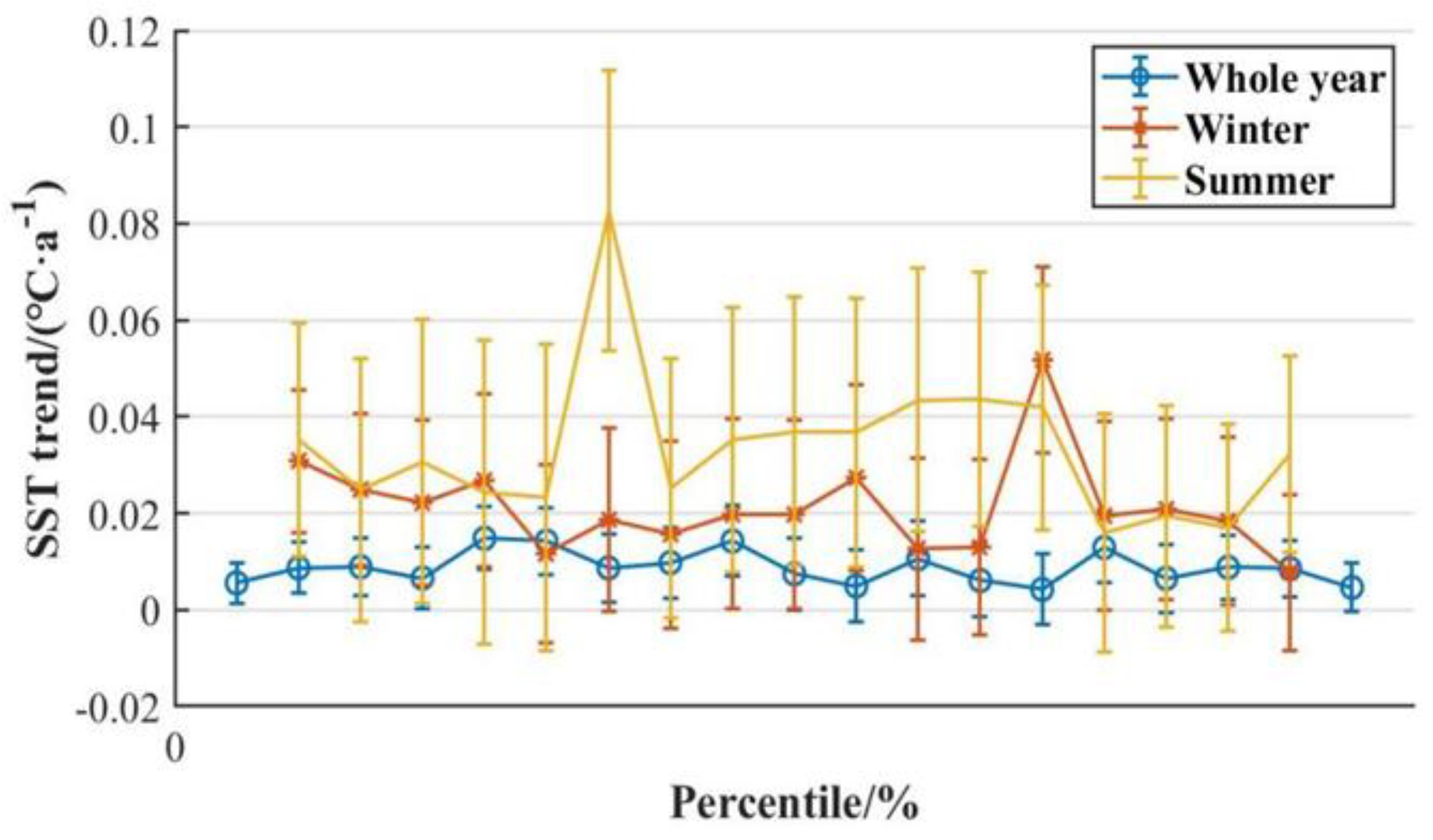

3.2.3. Wind

Wind speed serves as the primary dynamic factor regulating vertical mixing within the upper oceanic layer and sea surface temperature. The average wind speed in the Yellow and Bohai Seas from 2005 to 2024 was 4.4625 m/s, consistent with prior research findings: when wind speeds fall below 2 m/s, chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentrations typically remain elevated, whereas exceeding this threshold results in a marked decline in Chl-a levels [

42]. At the pan-oceanic scale, both wind speed and wind speed-derived Chl-a exhibit an inhibitory effect on Chl-a (r = −0.1667). This is primarily due to enhanced wind speed promoting vertical mixing and surface evaporation cooling. This dual action reduces Chl-a concentrations by lowering SST and displacing phytoplankton from the photic zone.

In the nearshore waters of the northern Yellow Sea (NYS), wind speed exhibits a negative correlation with chlorophyll-a (r = -0.319), with pronounced seasonal variation. Winter wind speed reduction leads to shallower mixed layers and insufficient nutrient upwelling, inhibiting phytoplankton growth. In summer, even a slight increase in wind speed may induce re-mixing processes, partially mitigating the decline in chlorophyll-a. Conversely, in the Qinhuangdao coastal area (QHD), the correlation between the two is exceptionally strong (r = -0.5166), with the inhibitory effect of wind speed being particularly pronounced. This region's shallow waters and significant terrestrial inputs mean stronger winds readily disrupt local water stability, diluting or vertically dispersing phytoplankton and markedly reducing Chl-a concentrations. This aligns with the strong negative correlation between MLD and Chl-a observed here. Compared to the aforementioned zones, wind-driven mixing in the deep southern Yellow Sea (YSDA) exerts limited direct regulation on Chl-a (r = −0.1231), more likely influencing phytoplankton growth conditions indirectly through coupled interactions with cold water mass activity and MLD variations.

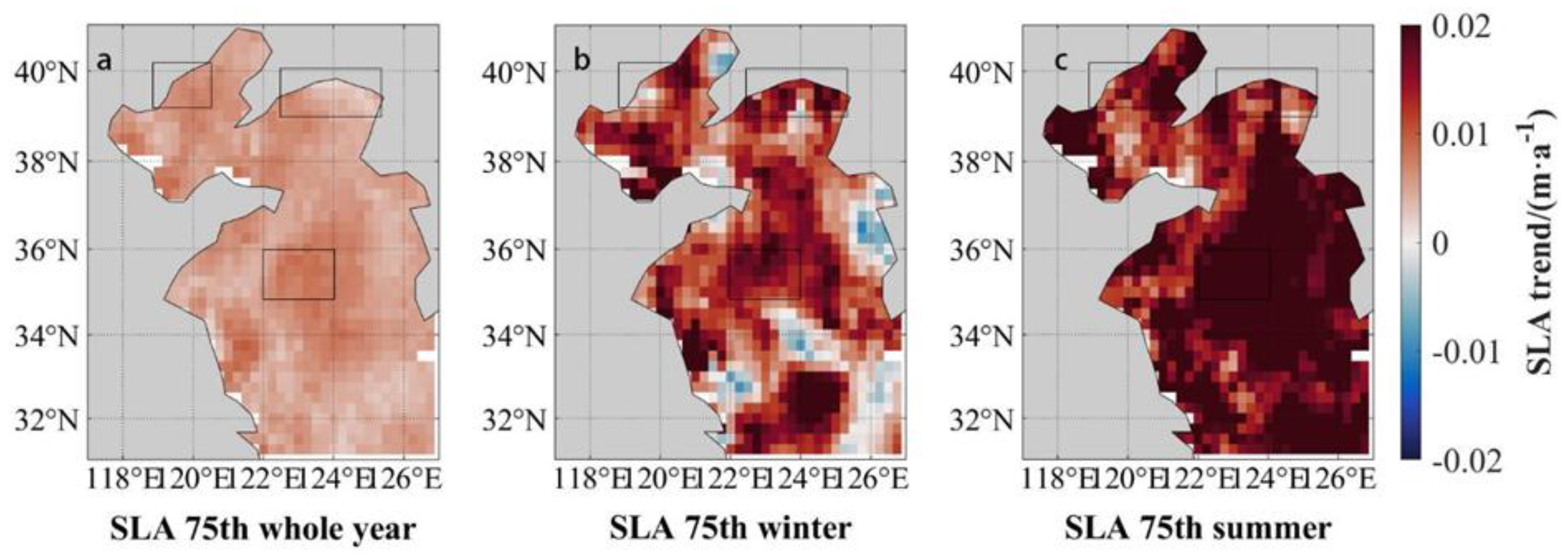

3.2.4. SLA

From 2005 to 2024, the study area exhibited an overall upward trend in Sea Level Anomaly (SLA). Spatially, the Yellow Sea showed a higher rate of increase (0.0048 m/a) than the Bohai Sea (0.0042 m/a), while the central sea area (0.006 m/a) increased faster than the coastal sea area (0.0024 m/a). Seasonally, the rise in sea surface height (SSH) was greater during summer than winter (

Figure 10). The spatiotemporal variations in SLA fundamentally reflect the combined effects of regional water mass movements, sea level changes, and oceanic dynamic processes.

Across the entire marine domain, SLA exhibits a positive correlation with chlorophyll-a (r=0.1877). The core mechanism involves sea-level change indirectly regulating phytoplankton growth by influencing local water transport, nutrient redistribution, and upwelling intensity. However, regional differentiation is markedly pronounced: SLA is the most strongly correlated factor in the Qinhuangdao coastal area (QHD) (r=0.8955), where sea-level rise enhances water exchange capacity and nutrient redistribution efficiency, thereby creating favourable conditions for phytoplankton growth. This aligns with the characteristic of Chl-a in this region being co-regulated by terrestrial inputs and local dynamic processes [

43]. The stimulatory effect of rising SLA on Chl-a in the southern deep waters of the Yellow Sea (YSDA) is relatively weak (r = 0.2553), with its influence primarily mediated indirectly through interactions with water mass exchange and MLD variations, reflecting the complexity of open-ocean dynamics. Sea-level rise exerts an extremely weak influence on the northern Yellow Sea nearshore region (NYS), indicating that weakened upwelling and insufficient nutrient supply exert a slight inhibitory effect on chlorophyll-a, with limited direct regulatory effects from SLA.

Overall, the long-term decline in Chl-a concentrations across the Yellow and Bohai Seas represents the synergistic effect of four primary factors: MLD, wind, SST, and SLA. Moreover, the driving mechanisms exhibit significant regional heterogeneity:

Across the entire marine domain, MLD emerges as the dominant regulatory factor (r = -0.5226), indicating that vertical mixing processes constitute the most critical physical mechanism governing phytoplankton biomass. Wind speed (r = -0.1667) and SST (r = -0.2211) both exhibit inhibitory effects, acting respectively by enhancing vertical diffusion and exacerbating thermal stress alongside nutrient limitation. Conversely, SLA exhibits a positive correlation with chlorophyll-a (r = 0.1877). Oceanic dynamic processes accompanying sea-level rise—such as water transport and nutrient redistribution—exert a marginal overall stimulatory effect on phytoplankton growth.

The Qinhuangdao coastal area (QHD), as a typical zone of strong anthropogenic-natural coupling, exhibits Chl-a variations dominated by local physical processes. This manifests as an extremely strong negative correlation with mean daily depth (MLD) (r = -0.9831) and a significant negative correlation with wind speed (r = -0.5166). The shallow water depth in this region means that minor alterations in the physical environment can decisively influence chlorophyll-a concentrations by modifying water stability and the phytoplankton dilution effect. Concurrently, the strong positive correlation with sea level altitude (r = 0.8955) further highlights the crucial role of sea level changes in regulating water exchange and nutrient supply within such complex nearshore ecosystems.

Correlations among factors in the offshore deep-sea area (YSDA) are generally weak, indicating that chlorophyll-a variations there are more strongly regulated by large-scale oceanic dynamic processes (such as cold water masses and water mass exchange) and the coupled effects of these factors.

The North Yellow Sea (NYS), as a transitional zone, exhibits driving mechanisms intermediate between coastal and deep-ocean regions. It is more significantly governed by monsoon-regulated wind speed (r = -0.319) and MLD (r = -0.4006) variations. The shallowing of the mixed layer and insufficient nutrient upwelling resulting from weakened winter monsoons constitute the primary pathways inhibiting phytoplankton growth in this region.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between chlorophyll-a and other environmental factors in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao Sea Area (QHD), Northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and the Yellow Sea Deep Area (YSDA) during summer.

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients between chlorophyll-a and other environmental factors in the Bohai Sea and Yellow Sea (BSYS), Qinhuangdao Sea Area (QHD), Northern Yellow Sea (NYH), and the Yellow Sea Deep Area (YSDA) during summer.

| |

SST |

Windspeed |

MLD |

SLA |

| BSYS |

-0.2211 |

-0.1667 |

0.5226 |

0.1877 |

| NYS |

-0.0875 |

-0.3190 |

-0.4006 |

-0.0651 |

| QHD |

-0.1987 |

-0.5166 |

-0.9831 |

0.8955 |

| YSDA |

-0.0446 |

-0.1231 |

-0.0264 |

0.2553 |

Figure 13.

75th percentile SST trends for the whole year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 13.

75th percentile SST trends for the whole year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 14.

Trends in the 5th–95th percentiles of annual, winter, and summer SST in the Bohai and Yellow Seas. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

Figure 14.

Trends in the 5th–95th percentiles of annual, winter, and summer SST in the Bohai and Yellow Seas. Vertical bars indicate the standard error of each regression.

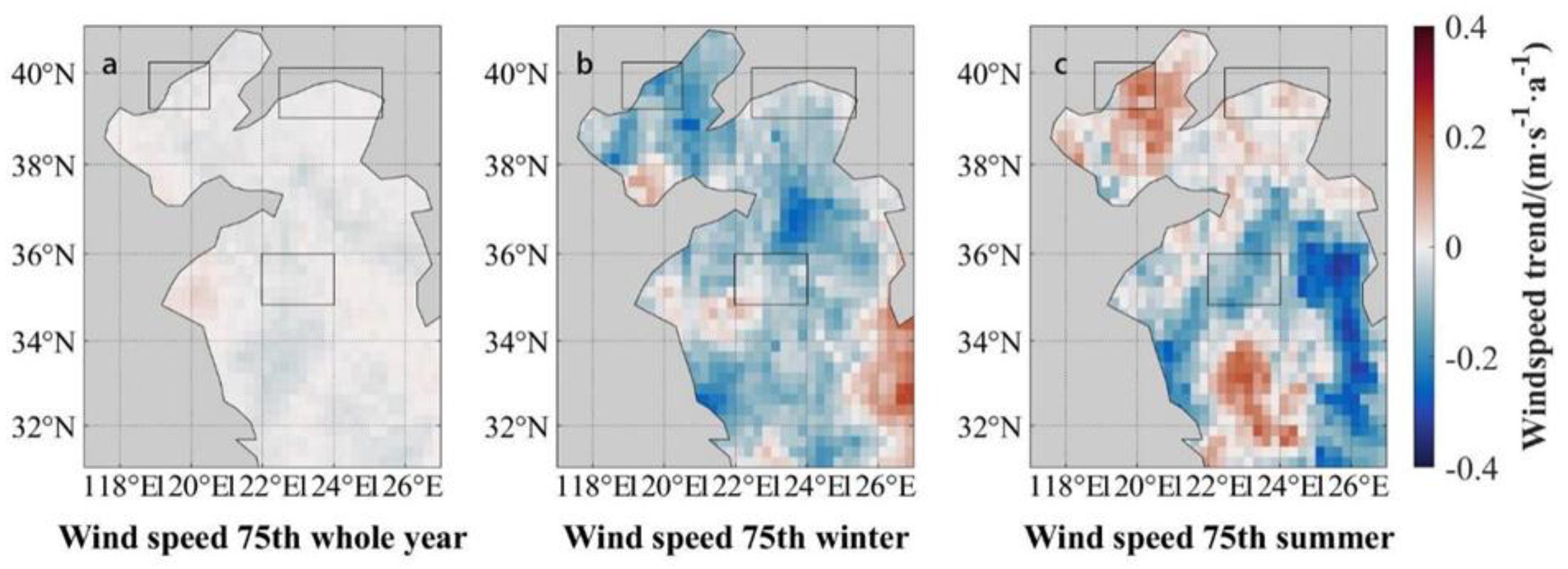

Figure 15.

75th percentile wind speed trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 15.

75th percentile wind speed trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 16.

75th percentile MLD trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 16.

75th percentile MLD trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 17.

75th percentile SLA trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

Figure 17.

75th percentile SLA trends throughout the year (a), winter (December to February) (b), and summer (June to August) (c).

4. Conclusions

This study reconstructed chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) concentration datasets for the Yellow and Bohai Seas from 2005 to 2024 using the DINCAE algorithm. By combining quantile regression with linear regression, it systematically examined the spatio-temporal distribution, long-term trends, and key environmental drivers of Chl-a variability in the region. The main conclusions are as follows:

Chl-a concentrations exhibit a long-term decline with clear concentration dependence and pronounced spatio-temporal heterogeneity. From 2005 to 2024, Chl-a levels showed a marked overall decrease, with an average annual rate of –0.0182 mg/(m³·a). Seasonally, the decline was strongest in summer (–0.0638 mg/(m³·a)) and more moderate in winter (–0.04 mg/(m³·a)). Quantile regression further revealed that high-concentration waters (75th percentile and above) experienced substantially greater reductions (–4.82×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a)) than low-concentration waters (25th percentile: –4.09×10⁻³ mg/(m³·a)), highlighting the concentration-dependent nature of the decline.Spatial patterns showed a clear gradient, with stronger declines nearshore and weaker declines offshore. High-concentration zones along the northern Yellow Sea coast and around the Gulf of Korea exhibited especially pronounced reductions at higher quantiles. Nearshore Qinhuangdao, where local hydrodynamic disturbances and land-derived inputs play a major role, recorded a decline rate (–0.0268 mg/(m³·a)) exceeding the regional average. In contrast, the deep-water southern Yellow Sea showed only slight decreases, largely governed by basin-scale oceanic processes rather than local forcings.

The influence of environmental factors on chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) exhibits clear regional differentiation, with mixed layer depth (MLD) emerging as the primary driver. At the basin scale, MLD shows the strongest correlation with Chl-a (r = –0.5226) and thus acts as the dominant physical factor regulating its variability. By altering vertical mixing, MLD affects both light availability and nutrient supply, ultimately contributing to the observed decline in Chl-a concentrations.Sea surface wind speed also shows a significant negative correlation with Chl-a (r = –0.1667). Strong winds enhance vertical mixing and reduce light penetration, thereby inhibiting phytoplankton growth. Sea surface temperature (SST) displays a long-term warming trend, with a faster increase in summer (0.3314 °C/a) than in winter (0.2709 °C/a). SST is weakly negatively correlated with Chl-a overall (r = –0.2211), with an even stronger negative relationship in nearshore regions such as Qinhuangdao (r = –0.1987). Rising temperatures can reduce nutrient solubility and push conditions beyond the optimal thermal range for phytoplankton growth, suppressing biological productivity.In contrast, sea level anomaly (SLA) shows a positive correlation with Chl-a (r = 0.1877), which is particularly pronounced in the Qinhuangdao coastal area (r = 0.8955). SLA affects Chl-a by modulating local water transport and nutrient redistribution. However, in the deep waters of the southern Yellow Sea, Chl-a dynamics are governed primarily by mesoscale processes—including eddies and water mass exchange—rather than by local physical forcing.

Regarding the mechanisms driving nearshore–offshore differences, the study reveals clear spatial contrasts. In nearshore areas such as Qinhuangdao, strong wind–wave disturbance and the deepening of the mixed layer enhance vertical mixing, leading to light limitation and sediment resuspension. These processes substantially suppress phytoplankton growth and accelerate the decline in chlorophyll-a. In contrast, phytoplankton dynamics in open waters are regulated mainly by mesoscale processes—such as fronts and eddies—while the direct effects of local physical forcing are comparatively weak.

This study successfully addressed gaps in satellite remote-sensing data using the DINCAE algorithm and demonstrated the value of quantile regression for analysing chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) trends across different concentration levels. Together, these methods offer a robust framework for multidimensional analyses of coastal ecosystem dynamics.The identified “nearshore–offshore” gradient in Chl-a decline, along with the region-specific driving mechanisms, provides actionable insights for ecological management in the Yellow and Bohai Seas. Nearshore zones require continued strengthening of land-based pollution control and more effective regulation of aquaculture activities. In contrast, offshore regions demand close monitoring of changes in oceanic dynamic processes linked to climate variability.Furthermore, the more pronounced decline in high-concentration areas indicates that recent eutrophication control measures have been effective, offering scientific support for ongoing ecosystem restoration and sustainable development in the region.

Funding

Liaoning Province Science Data Center(2025JH27/10100005); Science and Technology Plan of Liaoning Province(2024JH2/102400061); Dalian Science and Technology Innovation Fund(2024JJ11PT0070); Dalian Science and Technology Program for Innovation Talents of Dalian(2022RJ06); Liaoning Province Education Department Scientific research platform construction project (LJ212410158039,LJ232410158056); Basic scientific research funds of Dalian Ocean University(2024JBPTZ001,2024JBQNZ002).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Data Support from National Marine Scientific Data Center (Dalian) (

http://odc.dlou.edu.cn/), National Science & Technology Infrastructure, Liaoning Marine and Polar Science Data Center, Dalian Marine Science Data Center for providing valuable data and information.We also thank the reviewers for carefully reviewing the manuscript and providing valuable comments to help improve this paper.

References

- Yue T, Bin Z, Xiaomin Y. Study on the chlorophyll a concentration retrieved from HY-1C satellite coastal zone imager data[J]. Haiyang Xuebao, 2022, 44(5): 25-34.

- Lévy, M., Franks, P. J. S., & Smith, K. S. (2018). The role of submesoscale currents in structuring marine ecosystems. Nature Communications, 9(1), 4758.

- Zhu X, Wu K, Wu L. Influence of the physical environment on the migration and distribution of Nibea albiflora in the Yellow Sea[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2017, 16(1): 87-92.

- Liu S M, Li L W, Zhang Z. Inventory of nutrients in the Bohai[J]. Continental Shelf Research, 2011, 31(16): 1790-1797.

- Wu Dexing, Wan Xiuquan, Bao Xianwen, et al. Comparison of summer temperature-salinity fields and circulation structures in the Bohai Sea in 1958 and 2000[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2004, 49(3): 287-292.

- Zhu M Y, Mao X H, Lu R H, et al. Chlorophyll a and primary productivity in the Yellow Sea[J]. Journal of Oceanography of Huanghai & Bohai Seas, 1993, 11(3): 38-51.

- Lin Mingsen,He Xianqiang,Jia Yongjun, et al. Advances in marine satellite remote sensing technology in China[J]. Haiyang Xuebao,2019, 41(10):99–112. [CrossRef]

- 41(10):99–112. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0253−4193.2019.10.006. [CrossRef]

- Gong G C, Shiah F K, Liu K K, et al. Spatial and temporal variation of chlorophyll a, primary productivity and chemical hydrography in the southern East China Sea[J]. Continental Shelf Research, 2000, 20(4-5): 411-436.

- Sun Lecheng, Wang Juan, Wang Lin. Quantitative Retrieval of Surface Chlorophyll-a Concentration in North China Sea Area by Remote Sensing Based on On-site Measured Data[J]. Ocean Development and Management, 2019, 36(4): 34-38. [CrossRef]

- Cui T W, Zhang J, Wang K, et al. Remote sensing of chlorophyll a concentration in turbid coastal waters based on a global optical water classification system[J]. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 2020, 163: 187-201.

- Guangpu Y, Tao J, Yongfang Z, et al. Study on variation in chlorophyll a concentration and its influencing factors of Jiaozhou Bay in autumn based on long term remote sensing images[J]. Haiyang Xuebao, 2019, 41(1): 183-190.

- Yuli C, Fang S. Influence of Suspended Particulate Matter on Chlorophyll\| a Retrieval Algorithms in Yangtze River Estuary and Adjacent Turbid Waters[J]. Remote Sensing Technology and Application, 2016, 31(1): 126-133.

- Chaoyu Y, Danling T, Haibin Y E. A study on retrieving chlorophyll concentration by using GF-4 data[J]. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 2017, 36(5): 33-39.

- Kiyomoto Y, Iseki K, Okamura K. Ocean color satellite imagery and shipboard measurements of chlorophyll a and suspended particulate matter distribution in the East China Sea[J]. Journal of Oceanography, 2001, 57(1): 37-45.

- Qian L, Liu W L, Zheng X S. Spatial-temporal variation of Chlorophyll-a concentration in Bohai Sea based on MODIS[J]. Marine Science Bulletin, 2011, 30(6): 683-687.

- Meng Q, Wang L, Chen Y, et al. Change of chlorophyll a concentration and its environmental response in the Bohai Sea from 2002 to 2021[J]. Environmental Monitoring in China, 2022, 38(6): 228-236.

- Zhai F, Wu W, Gu Y, et al. Interannual-decadal variation in satellite-derived surface chlorophyll-a concentration in the Bohai Sea over the past 16 years[J]. Journal of Marine Systems, 2021, 215: 103496.

- Aohui M, Xiangnan L, Ting L, et al. The satellite remotely-sensed analysis of the temporal and spatial variability of chlorophyll a concentration in the northern South China Sea[J]. Haiyang Xuebao, 2013, 35(4): 98-105.

- Tang S, Dong Q, Liu F. Climate-driven chlorophyll-a concentration interannual variability in the South China Sea[J]. Theoretical and applied climatology, 2011, 103(1): 229-237.

- Tian Hongzhen, Liu Qinping, Joaquim I. Goes, et al. Temporal and spatial changes in chlorophyll a concentrations in the Bohai Sea in the past two decades[J]. Haiyang Xuebao(in Chinese),2019,41(8) : 131 - 140.

- Mamun M, Lee S J, An K G. Temporal and spatial variation of nutrients, suspended solids, and chlorophyll in Yeongsan watershed[J]. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 2018, 11(2): 206-216.

- Abbas A A, Mansor S B, Pradhan B, et al. Spatial and seasonal variability of Chlorophyll-a and associated oceanographic events in Sabah water[C]//2012 Second International Workshop on Earth Observation and Remote Sensing Applications. IEEE, 2012: 215-219.

- Tang, Dan Ling, et al. "Seasonal phytoplankton blooms associated with monsoonal influences and coastal environments in the sea areas either side of the Indochina Peninsula." Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 111.G1 (2006).

- Miles T N, He R, Li M. Characterizing the South Atlantic Bight seasonal variability and cold-water event in 2003 using a daily cloud-free SST and chlorophyll analysis[J]. Geophysical research letters, 2009, 36(2).

- Zhang X, Zhou M. A general convolutional neural network to reconstruct remotely sensed chlorophyll-a concentration[J]. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2023, 11(4): 810.

- Caterina B, Hubert-Ferrari A. Using 14 Years of Satellite Data to Describe the Hydrodynamic Circulation of the Patras and Corinth Gulfs[J]. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 2025, 13(3): 623.

- Ji C, Zhang Y, Cheng Q, et al. Evaluating the impact of sea surface temperature (SST) on spatial distribution of Chl-aorophyll-a concentration in the East China Sea[J]. International journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation, 2018, 68: 252-261.

- Luo X, Song J, Guo J, et al. Reconstruction of Chl-aorophyll-a satellite data in Bohai and Yellow sea based on DINCAE method[J]. International Journal of Remote Sensing, 2022, 43(9): 3336-3358.

- Barth A, Alvera-Azcárate A, Troupin C, et al. Reconstruction of missing data in satellite images of the Southern North Sea using a convolutional neural network (DINCAE)[C]//2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS. IEEE, 2021: 7493-7496.

- Han Z, He Y, Liu G, et al. Application of dincae to reconstruct the gaps in Chl-aorophyll-a satellite observations in the south china sea and west philippine sea[J]. Remote Sensing, 2024, 12(3): 480.

- Koenker, R., Bassett Jr, G., 1978. Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46, 33–50.

- Cade B S, Terrell J W, Schroeder R L. Estimating effects of limiting factors with regression quantiles[J]. Ecology, 1999, 80(1): 311-323.

- Liu D,Wang Y.Trends of satellite derived chlorophyll-a (1997–2011) in the Bohai and Yellow Seas, China: Effects of bathymetry on seasonal and inter-annual patterns[J].Progress in Oceanography,2013,116154-166.

- Lin W, Qing-hui M, Yu-juan M A, et al. Retrieval of chlorophyll a concentration from Sentinel-2 MSI image in Qinhuangdao coastal area[J]. Chinese Journal of MARINE ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE, 2023, 42(2): 309-314.

- Guan W J, He X Q, Pan D L, et al. Estimation of ocean primary production by remote sensing in Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea and East China Sea[J]. Journal of Fisheries of China, 2005, 29(3): 367-372.

- YU Lanfang, WU Xiao, BI Naishuang, LIU Jingpeng, WANG Houjie. TEMPORAL VARIATIONS OF THE CHLOROPHYLL-a CONCENTRATION OFF THE CHANGJIANG (YANGTZE) RIVER MOUTH AND RESPONSE TO THE THREE GORGES DAM[J]. Marine Geology Frontiers, 2020, 36(7): 56-63.

- Wang, Y., Jiang, H., Jin, J., Zhang, X., Lu, X., & Wang, Y. (2015). Spatial-Temporal Variations of Chl-aorophyll-a in the Adjacent Sea Area of the Yangtze River Estuary Influenced by Yangtze River Discharge. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(5), 5420–5438.

- Sun H H, Liu X H, Sun X Y, et al. Temporal and spatial variations of phytoplankton community and environmental factors in Laizhou Bay[J]. Marine environmental science, 2017, 36(5): 662-669.

- Shanxin, G., Bo, S., K, Z. H., Jing, L., Jinsong, C., Jiujuan, W., Xiaoli, J., & Yan, Y. (2017). MODIS ocean color product downscaling via spatio-temporal fusion and regression: The case of Chl-aorophyll-a in coastal waters. International Journal of Applied Earth Observations and Geoinformation, 73, 340–361.

- Agawin N S R, Duarte C M, Agustí S. Nutrient and temperature control of the contribution of picoplankton to phytoplankton biomass and production[J]. Limnology and oceanography, 2000, 45(3): 591-600.

- Clement A, Seager R. Climate and the tropical oceans[J]. Journal of climate, 1999, 12(12): 3383-3401.

- 43. Wang H, Shi S J, Li W S, et al. Causes of frequent coastal high-flooding events, owing to extreme changes of research, 2025 (3): 440-448.

- Zhang, Hailong, et al. "Seasonal and interannual variability of satellite-derived chlorophyll-a (2000–2012) in the Bohai Sea, China." Remote Sensing 9.6 (2017): 582.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).