1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Automation and artificial intelligence are increasingly central to modern agriculture, addressing the global demand for sustainable and efficient food production. A combination of population growth, labour shortages, and environmental pressures has accelerated the development of intelligent robotic systems capable of operating with precision and adaptability in complex natural environments [

1,

2]. Agricultural robotics has evolved from early mechanisation to advanced systems integrating computer vision, deep learning, and sensor fusion. These technologies aim to replicate or augment human perception and dexterity in diverse agricultural contexts [

3,

4,

5].

Among the various domains of agricultural automation, robotic harvesting presents one of the most technically demanding challenges. While significant progress has been achieved in crops such as apples, strawberries, and tomatoes [

6,

7,

8], the extension of these technologies to high-value niche crops like Lentinula edodes (shiitake) mushrooms, introduces unique difficulties. Mushrooms are typically cultivated indoors on stacked logs or substrates under controlled environmental conditions. The compact, cluttered growing environment and variable morphology of fruiting bodies impose strict constraints on perception, path planning, and manipulation [

9,

10]. Harvesting remains a manual, labour-intensive process requiring skilled workers to identify mature mushrooms and detach them carefully without damaging adjacent growths. Rising labour costs, workforce shortages, and the need for hygienic, consistent harvesting practices have driven increasing interest in automated systems [

11].

Recent advances in computer vision—particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and deep learning–based segmentation—have substantially improved object detection and localisation under variable conditions [

12,

13,

14]. Vision-based perception now underpins most autonomous harvesting systems, providing essential input for robotic actuation. However, their success depends on precise visual segmentation in cluttered, low-contrast environments typical of gourmet mushroom cultivation, where caps overlap and lighting conditions vary [

15]. Deep-learning models such as Mask R-CNN and YOLOv8-seg [

16,

17] have demonstrated strong potential for object detection and instance segmentation in related agricultural applications, suggesting similar viability for mushroom harvesting.

1.2. The Challenge of Mushroom Harvesting

Despite advances in agricultural robotics, mushroom harvesting remains underexplored. Early studies employed classical image-processing methods—such as colour thresholding and circular edge detection—to identify contrast between mushroom caps and substrates [

18,

19]. These approaches performed adequately in controlled conditions but failed under real-world variability, where illumination changes, surface reflections, and occlusion caused unstable segmentation. Subsequent systems incorporated RGB-D depth sensors to improve spatial perception [

18]. However, circular Hough transforms on colour images was employed for locating the mushrooms, so dense clustering, irregular geometries, and specular surfaces of mushrooms may limit the reliability of object differentiation.

A second major limitation concerns dataset quality and availability. Earlier models were trained on homogeneous and relatively small datasets captured under fixed lighting or camera configurations [

20]. These lacked diversity and generalisation capability, leading to poor performance in new conditions. Moreover, annotation inconsistency and the absence of standardised datasets have hindered benchmarking and thus have slowed progress toward deployable systems. Mechanical design has also restricted perception. Prototype harvesters often used fixed-angle cameras and rigid end-effectors, limiting their ability to perceive occluded regions and adjust dynamically during picking, although some use of a compliant gripper for mushroom harvesting has been reported [

19]. To achieve reliable performance, perception, planning, and manipulation must be developed as an integrated, adaptive system rather than as isolated modules.

1.3. Research Context

This study addresses these challenges by developing a unified deep-learning and computer-vision framework to support fully automated shiitake mushroom harvesting. The system introduces a multi-stage perception pipeline that leverages RGB-D imagery for three-dimensional understanding and applies advanced segmentation architectures—principally YOLOv8-seg and Mask R-CNN—for instance-level identification of mature mushrooms. As such, this is the first comparative evaluation of YOLOv8-seg and Mask R-CNN for mushroom harvesting using RGB-D imagery. The models were trained and validated on a curated dataset encompassing diverse lighting, viewpoint, and background conditions, thereby mitigating dataset bias identified in earlier research. In addition, post-processing algorithms were explored for extracting geometric features such as stem position and curvature, to guide robotic manipulation along collision-free trajectories. By coupling high-precision visual perception with robotic control, the proposed framework aims to enable consistent, efficient, and gentle harvesting without human intervention.

1.4. Objectives and Contributions

The objectives of this research are to:

- -

Construct a novel RGB-D dataset of shiitake mushrooms containing pixel-level annotations for deep-learning training.

- -

Compare YOLOv8-seg and Mask R-CNN in terms of accuracy, speed, and robustness under variable conditions.

- -

Evaluate the effect of depth data on model performance.

- -

Demonstrate proof-of-concept keypoint-based cut-point localisation for robotic harvesting.

The study’s principal contributions are:

- -

Creation of the first open-access RGB-D dataset dedicated to mushroom-harvesting research.

- -

A comparative quantitative and qualitative evaluation of two state-of-the-art segmentation frameworks, highlighting trade-offs between real-time efficiency and detection accuracy.

- -

Experimental demonstration of a multi-stage perception framework suitable for integration with a robotic harvesting system.

Collectively, these contributions advance the application of deep learning and computer vision in precision horticulture and establish a foundation for autonomous harvesting of dense crops such as oyster and enoki mushrooms. The work aligns with the broader goals of Industry 4.0, contributing to sustainable, intelligent food-production systems [

21,

22].

1.5. Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 describes the dataset, materials, and training methodology.

Section 3 presents quantitative and qualitative results.

Section 4 discusses the results and their implications for agricultural automation.

Section 5 outlines directions for future research.

Section 6 comprises the conclusion of the work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Initial Hypothesis

The experiments were designed to evaluate the performance of current state-of-the-art computer vision methods for automated shiitake mushroom harvesting and to explore approaches for improving detection accuracy. It was hypothesised that modern deep-learning-based vision systems would provide sufficient precision for robotic harvesting applications. Furthermore, incorporating depth information was expected to enhance accuracy by enabling better differentiation between mushrooms and the visually similar fruiting block.

2.2. Dataset

Deep learning models require extensive annotated datasets to learn discriminative features for accurate prediction. A diverse dataset mitigates bias and enhances model generalisation to varying conditions such as background complexity. No open-source 2D or 3D datasets of shiitake mushrooms on fruiting blocks were identified in existing literature or repositories. Consequently, new 2D and 3D datasets were curated to support this study’s objectives.

2.2.1. Choice of Sensor

Two 3D cameras—the Asus Xtion Pro and Microsoft Azure DK [

23], [

24]—were evaluated. The Xtion Pro, designed for general consumer use, employs infrared (IR) structured-light projection within a 0.8–3.5 m range via the OpenNI SDK [

25]. The Azure DK, developed for research and commercial applications, uses time-of-flight (ToF) IR depth sensing over 0.5–3.8 m and is supported by the Microsoft SDK [

26].

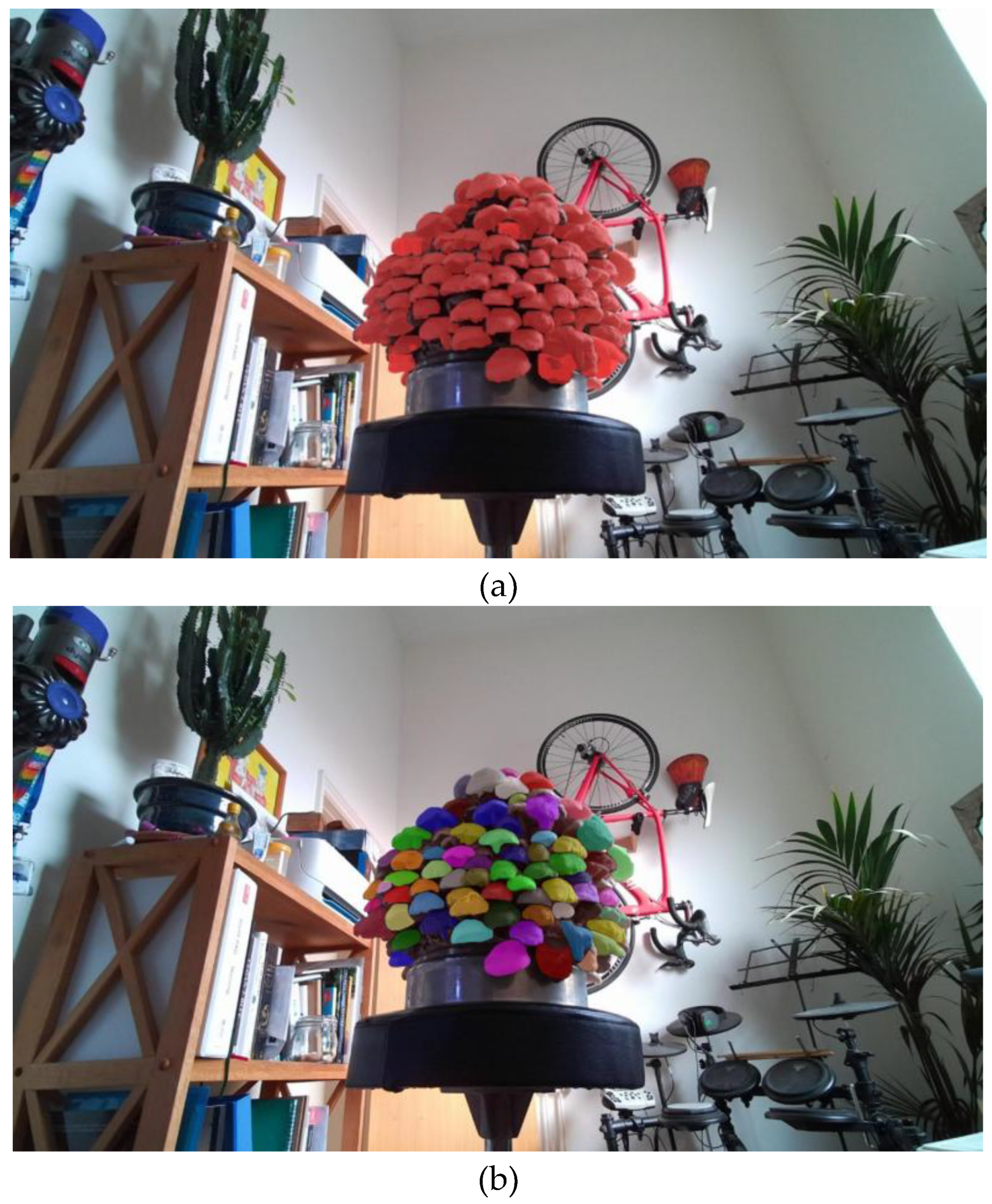

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show examples of the test.

Both devices provided adequate depth precision, though the Azure DK demonstrated superior performance, yielding higher-resolution colour images and more stable depth data with reduced noise and data loss. Accordingly, the Azure DK was selected for the remainder of this study.

2.2.2. Data Collection

Two shiitake fruiting blocks were obtained for image acquisition. The Azure DK’s four depth configurations—Narrow-FOV Unbinned, Narrow-FOV 2×2 Binned, Wide-FOV Unbinned, and Wide-FOV 2×2 Binned—were evaluated, with the Wide-FOV Unbinned setting providing optimal granularity.

Due to the mushrooms’ rapid growth rate and project time constraints, data diversity was maximised by capturing each block under two background conditions (simple and cluttered) and from three camera angles: level, slightly below, and slightly above. Since harvesting occurs from beneath the cap, most usable images were from level and lower perspectives.

Figure 3 shows these fruiting blocks from 2 of the perspectives and each background. Each block, containing approximately 200 mushrooms, was rotated during acquisition to increase variability.

Comparative 15 recording length = 60s, colour resolution = 1440p). The fruiting blocks were rotated slightly by hand and left to pause at each point for a second or two. The 60s video allowed for several full rotations of the block with each mushroom being viewed from slightly different angles. Python scripts were used to separate the .mkv recordings into 900 colour frames and 900 depth frames that will appear black and are of type uint16. Each of the video frame folders was reduced by only keeping every 20th image, ensuring that both the colour frames and depth frames were still matched correctly.

2.3. Model Choice and Annotation

The harvesting model must accurately detect shiitake mushrooms within images of fruiting blocks, providing precise localisation and potential yield estimation. Standard object detection algorithms such as Faster R-CNN [

27], SSD [

28], or YOLOv8 [

29] can identify object locations using bounding boxes. However, due to the close proximity and irregular shapes of mushrooms, instance segmentation was more appropriate. Algorithms such as Mask R-CNN [

16] and YOLOv8-seg [

17] extend detection models by adding polygonal segmentation masks, enabling more accurate separation of overlapping instances.

2.3.1. Data Annotation

Roboflow was selected for segmentation annotation due to its user-friendly interface and dataset management tools. Instance segmentation requires detailed polygonal masks outlining each object’s visible boundaries. Roboflow’s Smart Polygon tool assisted annotation but required manual correction because mushrooms often overlap or obscure one another, complicating automated edge detection. An example of the Roboflow user interface and the smart polygon feature is shown in

Figure 4.

Annotation rules ensured consistency:

Objects were outlined as accurately as possible.

Very small or unclear mushrooms were omitted.

Only visible portions were annotated.

In occluded cases, the portion including the cap was annotated.

Each image contained up to 75 annotated mushrooms;

Figure 5 shows a fully annotated image, where 73 individual shiitake mushrooms are annotated. In total, 92 images were annotated, producing 5,802 instances (~63 per frame). Datasets were divided into training, validation, and test sets. Data augmentation was applied via horizontal flipping to maintain realistic examples while increasing diversity. Increasing the training set size from 67 images to 118, gave a final training, validation and test split of 118:15:10.

2.3.2. Instance Segmentation Algorithms

Two state-of-the-art segmentation frameworks were evaluated:

Mask R-CNN (Detectron2 implementation), long regarded as an instance segmentation benchmark.

YOLOv8-seg, the recent YOLO variant supporting detection, segmentation, classification, and pose estimation.

2.3.3. YOLOv8

Released by Ultralytics in January 2023 [

17], YOLOv8 extends YOLOv5, offering models of varying complexity (YOLOv8n–x; 3.2–68.2 million parameters). It is a single-stage detector capable of segmentation and pose estimation, optimised for both performance and accessibility.

2.3.4. Detectron2

Detectron2, developed by Facebook AI Research (FAIR), reimplements Mask R-CNN [

16] in PyTorch and includes a modular architecture and pre-trained “model zoo”. The Mask R-CNN used here employed a ResNet-50 backbone pre-trained on Microsoft COCO [

30]. This configuration enables high-quality feature extraction and supports classification, segmentation, object detection, and keypoint detection.

2.3.5. Pre-training

Both YOLOv8 and Mask R-CNN were pre-trained on the Microsoft COCO dataset, which contains 328k annotated images spanning numerous object classes. Pre-training provides feature generalisation, reducing computational cost and improving convergence when fine-tuning on smaller, domain-specific datasets such as this one.

2.4. Model Training

Model training was conducted using Google Colaboratory (Colab)[

31], which provides GPU-accelerated (NVIDIA A100) environments for efficient deep learning experimentation. Colab’s integration with Jupyter Notebook [

32] allowed modular execution of Python code for setup, training, and evaluation. GPU and TPU resources were utilised to accelerate training due to the high computational demands of deep neural networks.

2.4.1. Hyperparameters

Most hyperparameters were retained at their default values within the Ultralytics and Detectron2 frameworks for fine-tuning to prioritise methodological clarity over extensive tuning. Selected adjustments were made for batch size and epochs to balance computational constraints with model convergence.

2.4.2. YOLOv8 Training

YOLOv8-seg was implemented from the Ultralytics repository using Colab. The model was initialised with COCO pre-trained weights, and the dataset was imported using a Roboflow API code. Model training on the base and horizontally flipped training dataset followed the defined hyperparameters, with validation conducted on the held-out validation subset and inference performed on the test set. Preliminary runs confirmed that the model could effectively learn from a dataset with numerous small instances despite limited image diversity. The batch size was set to 2 to accommodate hardware limits, and epochs were fixed at 50 based on training log observations. Model learning curves indicated satisfactory convergence, and further tuning was reserved for future work.

2.4.3. Detectron2 Mask R-CNN

The Detectron2 implementation required more detailed configuration. The repository was imported and the Mask R-CNN pre-trained model (ResNet-50 backbone) was loaded from the Detectron2 model zoo. The dataset, downloaded via Roboflow, was registered in COCO format, with visualisation used to verify annotations.

Training utilised the COCOEvaluator for validation and testing. Key hyperparameters were kept near default values, except for training iterations, defined as:

where N is the total number of samples, B is batch size, and E is the number of epochs.

Training employed a batch size of 2, a maximum of 3,000 iterations, and 118 augmented training images, equating to approximately 50 epochs.

2.5. Depth Model Training

To test the hypothesis that incorporating depth data enhances detection accuracy, depth information was integrated into the dataset. Direct modification of the network architecture to accept four-channel RGB-D input was found to exceed the project’s scope. Instead, a practical proxy solution was implemented; colour channel variance measurements identified that the least informative channel was blue, and this was substituted with the depth channel, producing RG-D images.

2.5.1. Depth Frame Matching and Integration

Since the dataset had been reduced from the original collection, an automated script was created to match corresponding depth and RGB frames based on filenames. Alignment verification was critical, as the Azure DK camera captures depth and colour data from separate sensors spaced 32 mm apart. Depth frames were stored as single-channel 16-bit unsigned integer images, which appear black to the human eye. To visualise and validate them, a Python script employing OpenCV [

33] normalised pixel values for display. This conversion confirmed integrity and allowed inspection for data distortion.

Figure 6 shows the colour frame next to the depth image converted from the single-channel depth frame, and in the latter the colour represents the depth. Subsequent blending of the RGB and depth frames demonstrated adequate alignment for model training, as shown in

Figure 7.

2.5.2. RG-D Training

After confirming alignment, the blue channel in each RGB image was replaced with the depth channel to generate the RG-D dataset. The new dataset, identical in structure to the original, retained the same annotations and was uploaded to Roboflow. Training followed the same procedure and hyperparameters as the RGB dataset using YOLOv8 and Detectron2. This enabled a direct performance comparison between RGB and RG-D models to evaluate the influence of depth data on segmentation accuracy.

2.6. Depth Reconstruction

Following evaluation of the RGB and RG-D models, additional experiments were conducted to explore further applications of depth data. It was hypothesised that combining segmentation masks with depth information and point-cloud reconstruction could provide geometric insights into mushroom morphology, potentially enabling estimation of parameters such as size, orientation, ripeness, and weight.

2.6.1. Mushroom Segmentation and Point-Cloud Reconstruction

Segmentation was performed using the trained Detectron2 Mask R-CNN model. The colour inference masks were applied to the corresponding depth images to isolate mushroom instances. Each masked depth image was saved for further analysis. Depth manipulation and reconstruction were implemented using the Open3D library [

34], which facilitates creation and rendering of point clouds from depth data. The resulting point clouds allowed qualitative assessment of object geometry and alignment accuracy.

3.7. Cut-Point Estimation

Once the mushrooms were detected and localised, the next step for autonomous harvesting was to determine a suitable cut-point along the stem for robotic removal. Multiple strategies exist for this; however, given the mushroom morphology, keypoint detection was identified as the most effective method.

3.7.1. Keypoint Annotation

Keypoints were annotated to represent optimal stem cut locations. Unlike typical human pose estimation tasks using multi-point skeletons, each mushroom required only a two-point “cutpoint” skeleton located on opposite sides of the stem base. Due to project time constraints, a smaller dataset was created specifically for this purpose. Because Roboflow does not support keypoint annotation, CVAT (Computer Vision Annotation Tool) [

35] was used. Early trials attempting to use segmented outputs for keypoint labelling proved inefficient, as stem visibility was often limited by occlusion and image resolution. Therefore, cut-points were annotated directly on full fruiting block images, using only images captured from below to maximise stem visibility. Annotation rules were intentionally relaxed to accommodate occlusion; any clearly visible stem was marked at its lowest observable point, assuming a bottom-up harvesting strategy. The final dataset contained 18 images with 344 annotated cut-points. After an 80/20 train-test split, 14 training images (272 instances) and 4 test images were retained. Both YOLOv8-Pose and Detectron2 keypoint detection frameworks were employed, leveraging pre-trained MS COCO keypoint weights [

31].

Figure 8 shows an example of the annotations on CVAT, enlarged for clarity.

2.7.2. YOLOv8-Pose

For YOLOv8-Pose, annotation files were converted from COCO JSON to the Ultralytics YOLO format. Each image was associated with a corresponding text file containing keypoint coordinates. A YAML configuration file defined dataset parameters and model settings as per Ultralytics documentation [

17]. Training followed the standard YOLOv8 pipeline, maintaining default hyperparameters. Visualisations confirmed correct loading of images and annotations.

2.7.3. Detectron2

Keypoint detection using Detectron2 followed a similar workflow to instance segmentation but required additional dataset registration. Detectron2 was configured in Colab, with the dataset stored in Google Drive and registered as separate training and testing sets. Visual verification confirmed correct annotation parsing in COCO format. Hyperparameters included 4,000 training iterations (≈571 epochs for 14 images), a batch size of 2, and a learning rate ramping from 0 to 0.00025 over the first 1,000 iterations. Evaluation was conducted using four test images after model convergence.

2.8. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively assess model performance, consistent evaluation metrics were employed across experiments. For comparability, both YOLOv8 and Detectron2 models were trained and tested on identical train–validation–test splits. Metrics were derived from standard object detection and segmentation evaluation protocols, adapted for single-class (shiitake mushroom) analysis. Model accuracy was first evaluated using

Intersection over Union (IoU), performance was further characterised by

Precision (P) and

Recall (R). Precision reflects detection accuracy, while Recall measures completeness. Because either metric alone may be misleading, the

F1-score was also computed to balance both:

The F1-score provides a robust single measure of model performance, especially for unbalanced datasets. Average Precision and Mean Average Precision were employed, with COCO metrics [

31] applied to assess model robustness at multiple IoU thresholds and object sizes.

3. Results

3.1. Colour Instance Segmentation

The first objective of this study was to evaluate the capability of deep learning–based instance segmentation methods for identifying shiitake mushrooms growing on fruiting blocks. Both models—Detectron2 Mask R-CNN and YOLOv8m-seg—were pre-trained on the Microsoft COCO [

18] dataset and trained under identical conditions (epochs and batch size). Each model successfully converged on the newly created shiitake dataset, achieving stable optimisation of network weights.

Table 1 presents quantitative results for selected evaluation metrics discussed in

Section 2.8. For AP@[IoU = 50] a prediction is correct if the prediction overlaps the ground truth by at least 50%. AP@[IoU = 50:95] reports the mean AP across IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95 (in steps of 0.05), requiring increasingly precise overlaps for a positive detection.

Quantitatively, YOLOv8 achieved superior accuracy and markedly faster inference than Mask R-CNN. Qualitatively, however, both models performed comparably.

Figure 9 illustrates representative inference results. Detectron2 generally produced accurate segmentations, occasionally missing smaller or partially occluded mushrooms, while YOLOv8 yielded cleaner boundaries and fewer missed detections.

Despite YOLOv8’s higher quantitative performance, Detectron2 Mask R-CNN was selected for subsequent stages due to its flexibility, extensive documentation, and suitability for downstream processing and experimentation. Nevertheless, YOLOv8 remains a strong candidate for future deployment owing to its superior speed and precision.

3.2. RG-D Instance Segmentation

To evaluate the hypothesis outlined in

Section 2.1, the RGB dataset was compared with the RG-D dataset—constructed by replacing the blue channel with depth data—to assess whether depth information improved segmentation performance. Both datasets contained identical images and annotations, and were trained under the same conditions using the Detectron2 Mask R-CNN model.

As shown in

Table 2, accuracy was comparable across both datasets, with RGB data achieving marginally higher scores in all metrics. These results suggest that the inclusion of depth information did not provide a measurable performance advantage under the tested conditions.

Figure 10 shows an example of the detection and segmentation on the RG-D image. Qualitatively, the RG-D images exhibited a yellow hue due to the absence of the blue channel; nonetheless, the model maintained stable detection and segmentation. Overall, while depth integration proved feasible, it did not yield a significant accuracy improvement for this dataset.

3.3. Cut-Point Estimation

Following segmentation, the final objective was to determine potential cut-points for automated harvesting using keypoint detection models. As with segmentation, YOLOv8-Pose was trained first due to its streamlined implementation, followed by Detectron2 for comparison.

Early YOLOv8-Pose experiments revealed difficulty in learning keypoint positions. After 150 epochs, the mean Average Precision (mAP) for both bounding boxes and keypoints remained near zero, indicating a lack of convergence. Gradual improvement occurred with extended training, but overall detection performance remained poor.

Table 3 shows the results from running the trained models on the validation set of 4 images.

The small dataset (18 images, 344 annotated cut-points) and subtle visual cues for stem bases, limited model learning. Nevertheless, both YOLOv8 and Detectron2 produced qualitatively reasonable predictions, correctly identifying several plausible cut-points at mushroom stem bases.

Detectron2 exhibited superior learning stability, with accuracy increasing consistently within the first 30 of 4,000 training iterations. Visual inspection of inference results confirmed more frequent and accurately positioned predictions compared with YOLOv8.

Although quantitative metrics remained low, these results demonstrate the feasibility of using deep learning–based keypoint detection for identifying mushroom cut-points. With a larger annotated dataset and further optimisation, model performance is expected to improve substantially. The Google Drive link below provides the training scripts, README files, and datasets.

4. Discussion

4.1. Colour Instance Segmentation

YOLO has evolved rapidly through multiple iterations to become a leading object-detection framework, combining high accuracy with simple implementation. Its accessibility has expanded the reach of computer vision to a wide range of developers and researchers. Given its recent improvements and popularity, YOLOv8 was expected to outperform Detectron2 Mask R-CNN in instance segmentation. Quantitative results confirmed YOLOv8’s higher precision and faster inference, yet qualitative analysis revealed that Detectron2 achieved comparable segmentation quality for shiitake mushrooms. Owing to its mature documentation, modular design, and flexibility for downstream integration, Detectron2 was selected for subsequent stages. However, in time-critical or resource-limited applications, YOLOv8 may offer a practical advantage due to its speed.

Implications for agricultural automation:

These findings demonstrate that both architectures are viable for real-time perception in harvesting systems. YOLOv8’s low latency suits embedded applications or mobile robots with limited computational resources, whereas Detectron2’s flexibility and feature-rich outputs make it well-suited for integration into multi-stage pipelines combining perception, planning, and manipulation. The capability to segment dense mushroom clusters accurately represents a key enabling step toward autonomous picking.

4.2. RGB vs RG-D

The cluttered structure of shiitake fruiting blocks was initially expected to hinder colour-only segmentation, suggesting that depth input would be essential for improved accuracy. Contrary to this expectation, the RGB model performed remarkably well, achieving strong segmentation despite complex backgrounds. A direct comparison between RGB and RG-D datasets—created by substituting the blue channel with depth—showed minimal difference in accuracy. This suggests that colour cues alone captured sufficient spatial information. Blue-channel values in shiitake imagery, although low, may encode weak depth cues that networks exploit implicitly.

Implications for agricultural automation:

This outcome indicates that reliable object segmentation for harvesting can be achieved without dedicated depth sensing, simplifying system design and reducing computational load. Depth data, while valuable for manipulation planning, may not be essential for initial fruit detection. This insight can inform the design of low-cost perception systems deployable in commercial farms where hardware simplicity and robustness are critical.

4.3. Depth Reconstruction

Although not included in the quantitative results, depth-based 3D reconstruction experiments confirmed that segmentation outputs could be successfully converted into accurate spatial models. These reconstructions verified that colour instance segmentation alone provides sufficient geometric fidelity for downstream processing. Preliminary tests explored whether 3D point clouds could yield additional crop information, such as mushroom size, maturity, and pose. These appear feasible but were constrained by limited data and the high density of fruiting blocks, which frequently caused occlusion. In such cases, partial reconstructions lacked clarity without the wider scene context.

Implications for agricultural automation:

Accurate 3D reconstruction from 2D segmentation supports advanced robotic behaviours such as adaptive grasp planning and yield estimation. The demonstrated feasibility suggests that future agricultural robots could integrate perception and manipulation more tightly leveraging depth cues for collision-free trajectory generation and dynamic adjustment to occlusion. This integration represents a step toward intelligent, perception-driven harvesting systems. The depth cues also have the potential to help automate measurements for determining phenotypes.

4.4. Cut-Point Estimation

At the outset, it was uncertain whether keypoint detection could be adapted for identifying mushroom stem cut-points, as most prior work focuses on human pose estimation. Limited precedent required a trial-and-error approach. Initial attempts to annotate and train on individually segmented mushrooms proved impractical due to severe occlusion within dense fruiting blocks. A more effective strategy involved annotating all visible cut-points directly in full images, enabling detection in realistic harvesting contexts. Despite dataset limitations and occasional ambiguity caused by lighting or stem occlusion, both YOLOv8-Pose and Detectron2 generated plausible predictions. Detectron2 produced particularly accurate bounding boxes and keypoints near stem bases, confirming the feasibility of deep-learning-based cut-point estimation.

Implications for agricultural automation:

Reliable identification of stem cut-points is a crucial capability for robotic harvesting. Even with limited training data, the models demonstrated potential to provide spatial coordinates usable by robotic arms for precision cutting. This establishes a foundation for end-to-end autonomous harvesting, where perception directly informs actuation. Future development with larger datasets and refined pose-estimation networks could yield operational systems capable of selective, damage-free picking in dense environments.

5. Further Work

5.1. Dataset and Model Development

A larger and more varied dataset is essential for improving model generalisation. Future collection campaigns will include multiple fruiting blocks captured under different lighting conditions, camera angles, and growth stages. These data will enable the training of robust, domain-adaptive models capable of handling variability in commercial production environments.

Segmentation frameworks such as Detectron2 and YOLOv8-seg should be modified to accept true four-channel RGB-D input. This will allow a quantitative assessment of depth information and its computational cost. Hyperparameter optimisation—including learning-rate scheduling, batch size, and augmentation strategy—should be systematically explored to maximise model accuracy within the constraints of embedded hardware.

Keypoint annotations should be extended across the entire dataset so that a unified Detectron2 model can perform both segmentation and cut-point detection in a single inference pass. This multi-output design would simplify the perception pipeline and reduce inference latency.

5.2. Integration with Robotic Harvesting Systems

Future work will focus on embedding the trained vision models into a robotic harvesting platform capable of closed-loop operation. A feasible implementation could follow a multi-stage workflow:

Perception: A fixed or articulated RGB-D camera captures images of the fruiting block. The deep-learning model performs real-time instance segmentation to identify all visible mushrooms and estimate their maturity based on cap morphology.

Cut-Point Localisation: The keypoint-detection module identifies optimal stem cut-points for each detected mushroom, producing three-dimensional coordinates in the robot’s workspace.

Planning and Control: A motion-planning algorithm uses the spatial data to generate collision-free trajectories for the end-effector. Depth data can refine approach angles to avoid contact with adjacent fruiting bodies.

Actuation: A lightweight gripper with a blade, mounted on a robotic arm, performs precision cutting and transfers the mushroom to a collection container.

Feedback and Tracking: Post-cut images update a tracking module to record harvested mushrooms and estimate yield over time.

This integrated approach would transform the current perception framework into a fully operational harvesting subsystem. Using the same deep-learning models for both detection and cut-point localisation ensures perception continuity, while sensor fusion and tracking provide spatial awareness for continuous operation.

5.3. Broader Applications and Research Directions

Future work will also explore:

Cross-crop adaptation: Applying the developed perception pipeline to other clustered crops such as oyster mushrooms, beans, or berries to evaluate scalability and model transferability.

Real-time deployment: Porting the trained models to embedded GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson) and testing on-farm under variable illumination and humidity.

Yield estimation and phenotyping: Using reconstructed 3D models to monitor crop growth, maturity, and spatial distribution for precision-agriculture analytics.

Collaborative robotics: Integrating perception modules with cooperative robotic systems capable of operating simultaneously on shared fruiting blocks to increase throughput.

By progressing toward a fully integrated perception–manipulation platform, deep learning and computer vision will enable robots to identify, localise, and harvest mushrooms autonomously with the same delicacy and precision as human pickers. Such systems would reduce labour dependency, enhance productivity, and promote sustainable indoor cultivation practices aligned with the objectives of Industry 4.0 and smart agriculture.

6. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that advanced machine vision and deep learning can provide the perceptual foundation required for robotic harvesting of shiitake mushrooms. By developing and evaluating dedicated instance-segmentation and keypoint-detection models, the research established that modern architectures such as YOLOv8-seg and Detectron2 Mask R-CNN can accurately identify and delineate individual fruiting bodies in complex, cluttered environments. Despite the visual challenges posed by occlusion, texture similarity, and lighting variability, the models achieved robust segmentation performance, confirming the suitability of deep-learning-based vision for this task.

The results also indicate that colour imagery alone can capture sufficient spatial information for effective mushroom detection, potentially reducing the need for costly depth sensors in early perception stages. Nevertheless, the study demonstrated that depth data and 3D reconstruction can enhance geometric understanding, laying the groundwork for advanced spatial reasoning and manipulation. The proof-of-concept keypoint detection further confirmed that deep-learning models can approximate stem cut-point positions, a critical step toward fully autonomous harvesting.

Collectively, these findings represent a significant step toward intelligent, vision-driven automation in indoor agriculture. The integration of computer vision, deep learning, and robotic manipulation holds the promise of achieving precise, gentle, and scalable mushroom harvesting — tasks traditionally dependent on skilled manual labour.

Future developments will focus on dataset expansion, full RGB-D integration, and embedding the perception models into real robotic platforms capable of closed-loop operation. Once integrated with motion planning and adaptive control, such systems will allow robots to identify, localise, and harvest mushrooms autonomously with minimal supervision.

The broader implication extends beyond mushroom cultivation. The methodologies and architectures presented here can be adapted to other dense-crop scenarios such as berry, bean, or flower harvesting, contributing to the wider transformation of agricultural production. As machine vision and deep learning continue to evolve, their synergy with robotics will play a defining role in the next generation of sustainable, high-efficiency farming systems — realising the objectives of smart agriculture and the Industry 4.0 paradigm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F.H. and L.N.S.; methodology, T.E.R.; software, T.E.R.; validation, T.E.R. and M.F.H.; formal analysis, T.E.R.; investigation, T.E.R.; resources, M.F.H. and L.N.S.; data curation, T.E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.E.R.; writing—review and editing, M.F.H., M.L.S., and L.N.S.; supervision, M.F.H. and L.N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoU |

Intersection over UnionAP Average Precision |

| RGB-D |

Red, green, blue and depth (3D camera) |

| RGB |

Red, green and blue. |

| RG-D |

Reg, green and depth (with blue channel removed). |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- Licardo, J.T.; Domjan, M.; Orehovački, T. Intelligent Robotics—A Systematic Review of Emerging Technologies and Trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 542. [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Dastres, R.; Arezoo, B.; Karimi, F.; Jough, G. Intelligent robotic systems in Industry 4.0: A review. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Science and Technology 2024, pp.2024007 – 0.

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674.

- Boussetta, R.; Smail, R.; Hadjaj-Castro, A.; Foucher, S. Object detection in agriculture using deep learning: A review and case study. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 8102.

- Wang, D.; Cao, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Wu, X. A Review of Deep Learning in Multiscale Agricultural Sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 559. [CrossRef]

- Sa, I.; Ge, Z.; Dayoub, F.; Upcroft, B.; Perez, T.; McCool, C. DeepFruits: A fruit detection system using deep neural networks. Sensors 2016, 16, 1222.

- Singh, R., Nisha, R.; Naik, R.; Upendar, K.; Nickhil, C.; Chandra Deka, S. Sensor fusion techniques in deep learning for multimodal fruit and vegetable quality assessment: A comprehensive review. Food Measure 2024, 18, 8088–8109. [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; He, C.; Li, Z.; Deng, C.; Sun, T. Efficient tomato harvesting robot based on image processing and deep learning. Precision Agric 2023 24, 254–287. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yi, W.; Hu, D.; Computer vision and machine learning applied in the mushroom industry: A critical review, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, Volume 198, 107015, ISSN 0168-1699. [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Jones, A.; Mayol-Cuevas, W. Automatic mushroom detection and localisation using computer vision and deep learning. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2020, 51, 89–97.

- Koirala, B.; Zakeri, A.; Kang, J.; Kafle, A.; Balan, V.; Merchant, F.A.; Benhaddou, D.; Zhu, W. Robotic Button Mushroom Harvesting Systems: A Review of Design, Mechanism, and Future Directions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9229. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Deep Learning in Object Recognition, Detection, and Segmentation", Foundations and Trends. Signal Processing 2016, Vol. 8: No. 4, pp 217-382. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, L.; Haji Salam, M.S.B.; Sheikh, U.U.; Ayub, S. Exploring Deep Learning-Based Architecture, Strategies, Applications and Current Trends in Generic Object Detection: A Comprehensive Review, IEEE Access 2020, vol. 8, pp. 170461-170495, . [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.; Wu, X. Object Detection With Deep Learning: A Review, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning System 2019, vol. 30, no. 11, pp. 3212-3232. [CrossRef]

- Sujatanagarjuna, A.; Kia, S.; Briechle, D.F.; Leiding, B. MushR: A Smart, Automated, and Scalable Indoor Harvesting System for Gourmet Mushrooms. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1533. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; and Girshick, R.; Mask r-cnn, in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017, pp. 2961–2969.

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; and Qiu, J.; YOLO by Ultralytics, version 8.0.0, Jan. 2023. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics.

- Baisa, N.L.; Al-Diri, B. Mushrooms detection, localization and 3d pose estimation using rgb-d sensor for robotic-picking applications, arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.02837 2022, 2022.

- Rong, J.; Wang, P,; Yang, Q.; Huang, F. A field-tested harvesting robot for oyster mushroom in greenhouse, Agronomy [online], vol. 11, no. 6 2021, 2021, ISSN: 2073-4395. [CrossRef]

- Devika, G. & Karegowda, A. 2021). Identification of Edible and Non-Edible Mushroom Through Convolution Neural Network. 2021, 10.2991/ahis.k.210913.039.

- Djekić, I., Velebit, B., Pavlić, B. et al. Food Quality 4.0: Sustainable Food Manufacturing for the Twenty-First Century. Food Eng Rev, 2023, 15, 577–608. [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A. Food sustainability 4.0: harnessing fourth industrial revolution technologies for sustainable food systems. Discov Food, 2025, 5, 171 . [CrossRef]

- 3. T. Limited. “Xtion pro live.” Accessed: 18/08/2023. (), available from: http:// xtionprolive.com/asus-3d-depth-camera/asus-xtion-pro-live.

- Microsoft. “Azure kinect dk.” Accessed: 18/08/2023. (), available from: https://azure. microsoft.com/en-gb/products/kinect-dk.

- OpenNI. “Openni 2 sdk binaries docs.” Accessed: 18/08/2023. (), available from: https: //structure.io/openni.

- Microsoft, Azure kinect dk documentation. https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/ azure/kinect-dk/, Accessed: 18/08/2023, 2022.

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks, Advances in neural information processing systems, 2015, vol. 28.

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D. et al., Ssd: Single shot multibox detector, in proceedings of Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11– 14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14, Springer, 2016, pp. 21–37.

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; and Qiu, J. YOLO by Ultralytics, version 8.0.0, Jan. 2023. available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics.

- Lin, T.-Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) 2014, 740–755.

- Bisong, E. (2019). Google Colaboratory. In: Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform. Apress, Berkeley, CA. [CrossRef]

- Randles, B.M.; Pasquetto, I.V.; Golshan, M.S.; Borgman, C.L. Using the Jupyter Notebook as a Tool for Open Science: An Empirical Study, 2017 ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017, pp. 1-2. [CrossRef]

- The opencv reference manual, 2.4.9.0, Itseez, Apr. 2014.

- Zhou, Q.Y.; Park, J.; Koltun, V. Open3D: A modern library for 3D data processing, arXiv:1801.09847 2018, 2018.

- CVAT.ai Corporation, Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT), version 2.2.0, Sep. 2022. available from: https://github.com/opencv/cvat.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).